Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Lau Kar-leung: The dragon still dances

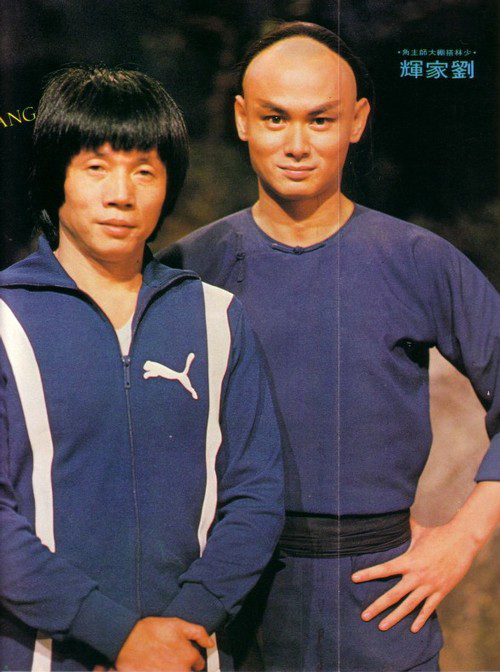

Lau Kar Leung (aka Liu Chia-liang, 1936-2013); Gordon Liu Chia-hui (aka Lau Kar-fei, 1955-).

DB here:

Back in 2020, I was asked to prepare a video lecture on the Hong Kong filmmaker Lau Kar-leung. Under the auspices of the Fresh Wave festival of young Hong Kong cinema, a retrospective and panel discussions were sponsored by Johnnie To Kei-fung and Shu Kei. The event took place in summer 2021. Tony Rayns also participated, offering a deeply informative talk that’s available here, but mine was not included. At a time when I hope people will continue to remember all that Hong Kong popular culture has given us, I’ve recast it as a blog entry.

For some years I’ve been arguing that the martial arts cinema of East Asia constitutes as distinctive a contribution to film artistry as did more widely recognized “schools and movements” of European cinema like Soviet Montage and Italian Neorealism. The action films from Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have revealed new resources of cinematic technique, and the filmmakers have influenced other national cinemas. The power of this tradition is particularly evident in Hong Kong cinema’s wuxia pian (films of martial chivalry), kung-fu films, and urban action thrillers from the 1960s into the 2000s.

Chinese martial arts are well-suited to the movie screen. The performance discipline, seen both in the martial arts and in theatrical traditions borrowing from them, yields a patterned movement that lends itself to choreography. The staccato quality of motion yields a pronounced pause/burst/pause rhythm that can be displayed and enhanced by film technique, as we’ll see.

These aspects of martial arts were captured by filmmakers working for the Shaw Brothers studios between 1965 and 1986. They cultivated a local style that yielded films that looked unlike any others. Thanks to the immense resources of the Shaw Movietown studio, complete with big sets and collections of costumes, the new filmmaking style was given a unique force. With The Temple of the Red Lotus (1965) and Come Drink with Me (1966), what Shaws called its “action era” began, and thanks to international distribution Shaws’ swordplay films gained audiences around the world.

Shaws’ Big 3

Shaw Movietown main office, 1997. Photo by DB.

The new trend benefited from Chinese opera traditions and the martial arts novels of Jin Yong, pen name of Louis Cha Leung-yung. They also owed a debt to Japanese swordplay films, many of which Shaws distributed and urged their directors to study. There was as well the influence of Italian Westerns. Just as important was Shaws’ investment in color and widescreen processes. Updating technology not only allowed the films to compete on the world market; it offered rich opportunities for artistic expression. (See the essay “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic adventures in Hong Kong.”)

Shaws directors quickly established conventions of the new swordplay film. Conflicts, of course, were expressed through combat, at least three major ones per film. One source of friction was the rivalry between martial arts schools run by masters; there might also be competition among traditions, regions (northern/southern), or nations (China vs. Japan). Typically there would be a hierarchy of villains, with our protagonists fighting them in turn. Plots would be more episodic than is typical in Western films. A looser structure favored including extensive set pieces of training or combat that were the appeal of the genre. And the plot would culminate in a long climactic fight, often to the death. These conventions, consolidated in the wuxia pian, carried over into the kung-fu films of the 1970s.

Two directors played central roles in shaping these conventions, and each had a distinctive approach to them. The vastly prolific Chang Cheh (Zhang Che) dominated the Shaws lot. He favored violent plots turning on revenge and intense male camaraderie, in which the martial arts served as a drama of loyalty or betrayal, friendship or deadly enmity. At the same period King Hu Chin-Chuan created one of the breakthrough “action era” works, Come Drink with Me, which immediately established a very different authorial vision. Hu was interested in historical and political intrigue, women warriors no less than male ones, and the martial arts as a spectacle of cinematic grace. Most of his major works, including A Touch of Zen (1971) were produced after he emigrated to Taiwan, although some were distributed by Shaw Brothers.

Neither Chang Cheh nor King Hu was trained in the martial arts, so they relied on choreographers to supply their action scenes. By contrast, Lau Kar-leung was a martial arts director who came to Shaws in the 1960s and choreographed many films for Chang and others. He took over directing duties in 1976 with The Spiritual Boxer and directed over twenty-five films for Shaws until 1985, when the company ceased producing theatrical features. He went on to direct several one-off projects until 2002.

Lau took the uniqueness of martial arts traditions more seriously than other directors, building entire films around one school or another, or among the contrast of rival traditions. He often opens the film with an abstract prologue showing off characteristic moves and tactics of the style that the film will treat. Unlike Chang, he is less concerned with male loyalty and violent revenge and is more inclined toward redemption and forgiveness. He shares Hu’s refined conception of film technique, but he is less overtly innovative. He refined stylistic conventions that were already in place at Shaws and many of which were basic to world cinema storytelling.

For example, Lau accepted the elevated production values demanded by the Shaw product. His films are filled with elaborate sets, both interiors and exteriors, and rich color values. He also recognized the power of editing, something that King Hu had brought to the fore. In the rest of this entry, I’ll concentrate on four of Lau’s distinctive innovations in the Shaws style.

Filling the wide frame

All widescreen filmmakers faced the problem of filling the spacious frame. (See CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses” for discussion of American solutions.) The big Shaws sets enabled filmmakers to pack the frame with figures and settings. We therefore find plenty of dense long-shot compositions.

We also find flashy closer views. Chang Cheh was particularly fond of low-angle medium shots, which he considered “warmer” than straight-on or high angles (The Assassin, 1967; choreographed by Lau).

Hong Kong directors relied on “segment shooting” for action scenes. Instead of overall coverage, with repetitions for different camera angles (the US norm), they plotted the fighting moves for specific camera angles and shot them separately. By calibrating the performers’ actions to the camera setup, they created a unique blend of martial arts techniques with film techniques. Rather than simply record martial-arts movements, filmmakers “cinematized” them.

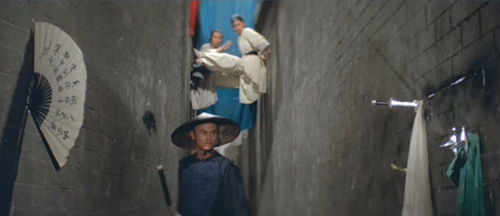

Lau seems to have taken particular pleasure in filling his frames in ingenious, fluid ways. He enjoyed the challenge of staging combat scenes in confined spaces, so that he couldn’t rely on expansive vistas. Partly, this tactic enabled him to show how different moves were required in close quarters. One of his favorite sequences was in Martial Club (1981). He explained:

Gordon Liu is fighting Johnny Wong in an alley that narrows from 7-foot to 2-foot wide. The physical limits of the alley actually make the best showcase for the different boxing schools. How do you fight in a seven-foot-wide alley? You use big arm and leg movements. Going down to five-foot wide, you keep your elbows close to your body because you don’t want to expose yourself. Further down to three-or-four foot wide, you use Iron String Fist. Finally when you get down to two-foot wide, you engage the “sheep trapping pose.” The results were sensational.

At the same time, the narrowing alley offered rich opportunities to fill the frame with body parts and abstract slices of walls.

Something similar occurs in Legendary Weapons of China (1982), where two assassins must hide in an alley above a third. This time Lau uses some props to fill out the wall areas.

Lau delights in the possibilities of close fighting in any space. Sometimes the confinement isn’t a matter of setting; it’s dependent on letting the film frame itself constrain the action. Take a portion of a sequence from Dirty Ho (1979). The Prince (in disguise) calls on Mr. Fan, who tries to attack him, all the while pretending to play the host by offering wine.

Establishing shots lay out the zones of action to come, the chairs the men will occupy. Even a momentarily unbalanced framing is compensated for by movement in the empty area.

The first phase of the scene takes place in much closer framings, often tight two-shots. It’s here we see Lau’s virtuosity in finding constantly fresh ways to fill the frame, with compositions always picked for maximum clarity: that is, in showing Fan’s aggression and the Prince’s resourceful blocking, sometimes with comic symmetry.

The pause/burst/pause rhythm gets played out in low angles, with slight camera movements to adjust to the gestures.

The two major props, the fan and cups, get a real workout as they participate in the constant ballet of arms, faces, and fingers. All areas of the screen get activated: top, bottom, corners and sides.

Later in the scene, in a passage I haven’t included in the clip, the servant gets to take part, so now even more body parts are spread across the frame–and a cup even comes out at the viewer.

The scene ends with a comic commentary on the props: master and servant collapse at the table as a cup overturns.

This “close-up action scene” is as fully designed for the widescreen as any expansive long-shot sequence might be, but there’s a particular enjoyment to be had in seeing how a director can do so much with simple components.

Editing: Analytical cutting

Contrary to what many think, Chinese action pictures rely heavily on editing. At Shaws, King Hu pioneered extremely rapid cutting, reducing shots to half a second or less. Lau became a rapid cutter as well; his films from the 1970s and 1980s typically average three to five seconds per shot, with some films containing over 1000 shots.

It’s commonly said that Hong Kong martial arts films favored full shots and long takes, the better to respect the overall dynamic of the combat. Full shots, yes; but not necessarily long takes. While Western directors tended to believe that long shots had to be held quite a bit longer than closer ones, Hong Kong directors realized that long shots could be cut fast if they were carefully composed for quick uptake. Lau’s mastery of composition stands him in good stead when he starts putting shots together: every combat, even the fast-cut ones, are crystal-clear in their execution.

Directors across the world had settled on two major editing resources: analytical cutting and constructive cutting. The first type shows the overall spatial layout of a scene and then analyzes it into partial views. Our Dirty Ho sequence is an example. Constructive cutting deletes the establishing shot and relies on other cues to help the viewer build up the scene mentally. Hong Kong filmmakers made extensive use of both types, and as you’d expect Lau is a master of each.

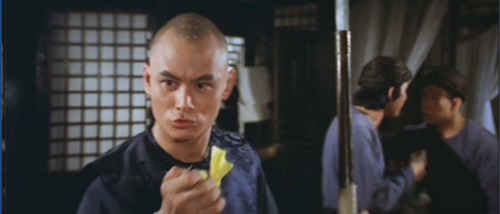

Most Hong Kong directors used analytical editing to favor the actors, to pick out their reactions to the ongoing action. Lau does this as well, as is seen in Dirty Ho. As you’d expect, Lau also uses cuts-in close views to emphasize combat tactics. In Challenge of the Masters (1976), after a villain (played by Lau) has felled his opponent, analytical cuts build to a revelation of a metal attachment to his shoe.

Executioners from Shaolin (1977) illustrates how Lau uses analytical editing during a large-scale fight scene. It’s far less constrained than the tabletop action of Dirty Ho, but he does find ways to narrow the action to particular zones. This is done through cuts to closer views–sometimes very close ones. And the editing is swift, with the average shot lasting only four seconds.

The scene’s opening establishes the hero Hung Hsi-kuan arriving at Pai Mei’s temple. There are two establishing shots, one a pan-and-zoom that presents the temple as Hung arrives, while the other (below) is a zoom back keeping the temple and Hung in the same frame. Both compositions stress the steep stairs leading up the hillside.

Once Hung starts up the stairs, more establishing shots reveal him surrounded. Lau indulges in a feast of different angles, stressing Hung’s vulnerability.

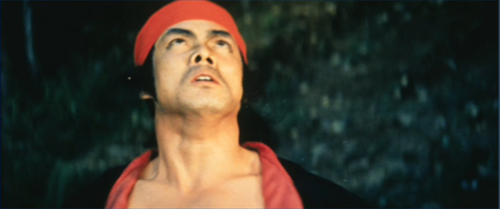

The scene’s second phase follows Hung’s progress up the steps. His encounters with many defenders are captured in a variety of angles, all of them orienting us to the changing situation. (At the top, he’ll encounter Lau himself, wielding a jointed staff.)

Camera setups on the steps themselves keep us aware of the forces arrayed around him. And the steps function a bit like the alleys in other films to limit the range of action.

The camera really penetrates the action, picking out details in the sort of tightly packed framings we saw in Dirty Ho.

Lau remarks: “You can get wonderful scenes of two pairs of hands folding and sliding in and out of each other’s grip.” This sort of tangible physical action is central to Lau’s scene analysis.

Analytical editing can include matches on action, cuts that let movement carry over across shots. Lau gives a virtuoso example in a match-on-action between extreme long-shots of a man in blue sent sprawling. The second shot ends with a zoom back.

It’s possible that Lau used two cameras for coverage of this, but that was a rare option in Hong Kong. It’s just as likely he managed the cut by repeating the fall, a movement stressed by a zoom back.

Again, you get a sense of a filmmaker challenging himself by setting up problems he will need to solve through mastery of his craft.

Editing: Constructive cutting

Trampolines and mattresses in shed on Shaw Movietown lot. Photo by DB.

The wuxia tradition features exponents of the “weightless leap,” the ability to spring very high into space. Before the advent of wirework and CGI, these soaring warriors were treated through editing that shows the leap in a series of shots. For instance, constructive cutting in Chang Cheh’s Golden Swallow (1968, choreographed by Lau) shows Silver Roc launching himself, soaring, and descending on his victim.

The jump was probably facilitated by a trampoline. On the screen, though, we see portions of the action that we assemble in our heads.

With his usual ingenuity, Lau sought out situations where he could test his skill with constructive editing–not just weightless leaps but combats among fighters at some distance from each other. My example is a brilliant sequence from Legendary Weapons of China (1982). (It takes place in semidarkness, so you may wish to adjust the brightness of your monitor.) Two rival assassins clash in a loft as they try to kill a third in the bedroom below. There ensues a three-way fight, pursued mostly through careful constructive editing.

There are a few establishing shots situating Ti Hau and Fan Shao Ching (disguised as a man) in the loft, but once they change their locations, most of the combat is given through constructive editing. That technique relies on cues of setting and character behavior (body position, facial expression, eyelines), and these are all mobilized early in the scene.

Details of props help us understand the action as well: the two threads bearing hooks and especially the gag with gas.

Once the assassin Ti Tan arrives on the floor below, pure constructive editing takes over. There’s no framing that includes him and his two attackers.

So Lau proceeds to cut together an ongoing fight upstairs (complete with fake meows) with Ti Tan’s suspicions downstairs.

The scene culminates in Fan and Ti Hau fleeing as Ti Tan, still suspicious, doubts that all the noise above him was created by a cat–and even the cat is presented through constructive editing.

In a sequence of 126 shots, the average is about two seconds, but each one is legible at a glance and carries the scene forward with utter smoothness. Lau’s precision in shot design serves him well when we have to assemble the action in our minds.

The smash zoom

Hong Kong action films of the 1960s are notorious for their use–some would say, over-use–of zoom shots. Yet at the time directors throughout the world were exploring the artistic possibilities of zooms. Most notable was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó, who coordinated the zoom with complex movements of actors and the camera. So we ought to consider the possibility that the zoom in Hong Kong was more than a technical gimmick to spice up action scenes.

For example, a smash zoom can accentuates the pause/burst/pause pattern of the fight. During one combat in Chang Cheh’s The Blood Brothers (choreographed by Lau), the zoom emphasizes sudden bursts of action by whipping back from a fighter.

Alternatively, the zoom can play up the pause by calling attention to moments of stasis. Here a cut emphasizes the pause as the fighters’s weapons are locked before the fight resumes with a zoom back.

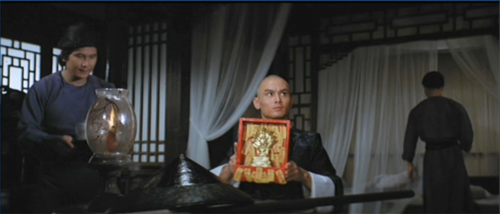

In such ways the zoom can break the fight into discrete stages. A far more elaborate instance takes place in Lau’s Return to the 36th Chamber (1980). Chu Jen-chi has painstakingly learned kung-fu at the temple through an apprenticeship of lashing bamboo poles together to make scaffolding. Accordingly, his technique is based on this very particular set of skills. I concentrate on the early stretches and the clip gives you some extra niceties. The whole thing is exhilarating to behold, thanks partly to energetic zooms.

Early on, the zoom introduces us to the lashing technique by showing the robe’s ripped fabric as a kind of handcuff.

Again we see Lau’s interest in watching how hands work, but here it becomes a specific combat tactic. The ensuing action will revolve around hands and wrists, and Lau’s zooms set up a question: What is Chu’s overall strategy?

The answer comes in a series of variations. First, Chu lashes his adversary to a bamboo pole like captured wild game.

Variation 2: Ensemble work. Chu takes on a batch of men, trussing them up horizontally.

He turns out to have in mind an engineering project, a sort of hitching post of miscreants. It’s capped by a shot of one of the Manchu bullies seeing his disciples’ wiggling fingers.

Variation 3: More ensemble work, now vertical, with the men’s wrists stacked like a bouquet.

Again, a master shot reveals the result and another close-up shows their wiggling fingers.

The kung-fu is of course extraordinary, but it takes an unusual cinematic imagination to heighten such elaborate patterns of movement in ways that are perfectly clear. Chu’s display of serious efficiency has a humorous side, capped by the gags that show the villains utterly flummoxed. We should ask if today’s action sequences in American films have this sort of unforced rigor and exuberance.

In the mid-1980s Shaw Brothers eased out of theatrical filmmaking, devoting Movietown to television production. Lau went on to one-off projects, some of which (e.g., Tiger on Beat, 1988) are well worth your attention. (Go here for the astonishing climax.) He had a late-career resurgence as choreographer for Tsui Hark’s Seven Swords (2005). But his prime achievements, I think, will remain his vastly entertaining and filmically rich Shaws classics. His dedication to the specifics of martial arts lore, his unique sense of comedy, and not least his precise direction brought unique qualities to the remarkable tradition of Asian action cinema.

Chang’s remark about “warm” low angles is in Chang Cheh, A Memoir (Hong Kong Film Archive, 2004), 82; he discusses shooting The Assassin on p. 86. Lau’s comments on Martial Club come from “We Always Had Kung-Fu: Interview with Lau Kar-leung,” in Li Cheuk-to, A Tribute to Action Choreographers (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006), 62; the remarks on hands are on p. 59.

I discuss Lau further in both Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and in this blog entry.

Lau as the drunken master in Heroes of the East (1978).

Sergei Loznitsa and the Ukraine invasion

Donbass (2018).

DB here:

Of the many gifted post-Soviet-era filmmakers, one has emerged prominently in response to Russia’s invasion of the country. Sergei Loznitsa was born in Belarus, grew up in Ukraine, and now lives in Germany. Long a harsh critic of Putin’s regime and the Soviet communism that preceded it, he recently resigned from the European Film Academy, citing its lukewarm response to the atrocities in Ukraine. Here is the full text of his letter, as published in Screen International (28 February).

What a shameful text has been generated by the European Film Academy! “The invasion in Ukraine is heavily worrying us”.

When, in the spring of 2014, Oleg Sentsov was arrested, you wrote to the Russian authorities asking them to “consider this matter carefully and fairly”.

Is it really possible that after 8 years of war you still remain blind and continue to mutter some gibberish about the fact that a “daily increase of tension has an impact on filmmakers’ lives and health, morale, and creative work”.

You state in your address that there are 61 Ukrainian members among your ranks. Well, as of today, there are only 60 of them. I don’t need you “being alert and staying in touch with me”, thank you very much!

You’d better ‘stay in touch’ with your own conscience.

For four days in a row now the Russian army has been devastating Ukrainian cities and villages, killing Ukrainian citizens. Is it really possible that you – humanists, human rights and dignity advocates, champions of freedom and democracy, are afraid to call a war a war, to condemn barbarity and voice your protest?

Today, on February 28, 2022, there can be no more doubt about one thing: the European Film Academy was set up in 1989 in order to bury its head in the sand and to shy away from the catastrophe which is taking place in Europe.

Sergei Loznitsa, filmmaker

The day after Loznitsa’s resignation the EFA issued a stronger statement of condemnation.

Loznitsa has directed several documentaries and four fiction features. The documentaries are notable for their comprehensive, patient rendition of original footage of historical incidents. No Ken Burns guidance of the viewer here, no pan-and-zooms or talking heads. There’s a remarkable refusal of voice-over narration to fill in the context of what we see. Even titles are sparse. Often the necessary background is given in an envoi. Homework for the viewer: We need to read up on exactly what we’re seeing.

Loznitsa has directed several documentaries and four fiction features. The documentaries are notable for their comprehensive, patient rendition of original footage of historical incidents. No Ken Burns guidance of the viewer here, no pan-and-zooms or talking heads. There’s a remarkable refusal of voice-over narration to fill in the context of what we see. Even titles are sparse. Often the necessary background is given in an envoi. Homework for the viewer: We need to read up on exactly what we’re seeing.

The Trial (2018), for instance, is an unblinking record of an early Stalinist show trial, in which scientists are charged with anti-Soviet sabotage. They read their confessions, but under questioning they seem confused about what they’re admitting to. The whole procedure is conducted with mechanical impersonality, and you watch for any sign that the accused men will crack. Only at the end do titles tell us that their supposed secret organization was wholly a creation of the regime. Likewise, The Event (2015) records citizen mobilization in St. Petersburg during the failed communist putsch against Gorbachev in 1991. It assumes the viewer will understand that the snatches of Swan Lake heard from time to time allude to the fact that Tchaikovsky’s score was broadcast continuously in place of news reports.

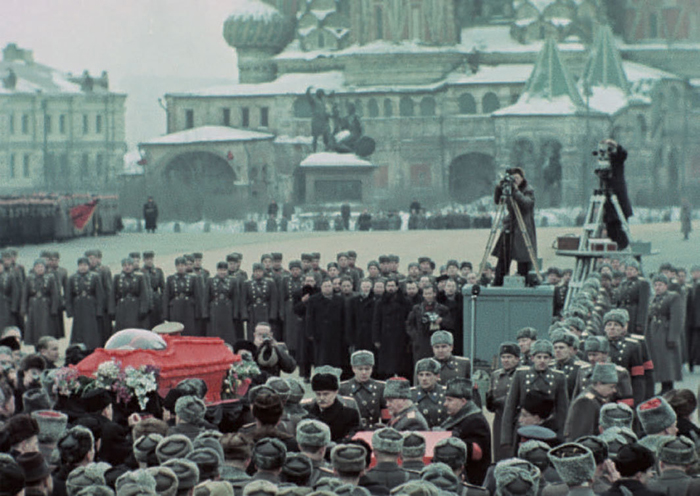

Perhaps most stunning of the documentaries I’ve seen is State Funeral (2019), an assemblage of footage of ceremonies following Stalin’s death. I’ve seen some of this material in other films, but to show the entire panorama of mourning across the Republics, mostly in dazzling color, brings home with crushing near-monotony how a regime can mobilize mass emotion. These people seem genuinely despairing at the loss of the Great Helmsman. The pageantry is at once splendid and appalling.

The three fiction films I’ve seen are bleak. My Joy (2010) follows a Russian truck driver through a landscape of poverty, corruption, and teen prostitution, and invokes World War II through a strange time-warp. In the Fog (2012) rewrites the scenario of the heroic Soviet WWII picture through the experiences of a man caught between both German occupation forces and Belarussian partisans.

Unlike these, Donbass (2018) lacks a single protagonist. It’s a string of scenes based on actual incidents from the 2010s. It shows the ongoing struggle between Putin-backed separatists and Ukrainian forces in Donesk, with ordinary people struggling to carry on. The tone is wider than in the other films, with pathetic scenes alternating with grotesque comedy. An early episode shows a woman stomping into a civic meeting and dumping a pail of shit on a bureaucrat’s head. A bit like Roy Andersson, Loznitsa connects his vignettes by having a character from one linking to the next, or letting an item of setting, such as a black Mercedes, reappear at different points. The whole film is enclosed by a tragic replay of an opening showing the staging of a fake massacre, to be filmed by an obliging official media outlet.

These films are fairly available. All the fiction features are on DVD or Blu-ray. Five of the documentaries (including A Night at the Opera, 2020, which shows a mordant sense of humor) are streaming thanks to Mubi. In the Fog is streaming from Fandor/ Amazon Prime. Some online sites are offering the films, subtitled, for free. The Guardian has made Maidan (2014) available on YouTube for the duration of the war on Ukraine, to support donations to the Ukrainian Army. This film traces the popular overthrow of President Yanukovich in the winter of 2013-2014.

Loznitsa’s films have been accorded many festival awards, in Cannes, Venice, and elsewhere. Sometimes castigated as “Russophobic,” they’re strong, bracing work and they deserve our attention, especially now.

Loznitsa’s website is here. His views of Soviet history are revealed in a spirited interview with Senses of Cinema. At Criterion’s The Current, David Hudson gives an up-to-date report. In The New Yorker Masha Gessen offers a thoughtful review of The Trial. J. Hoberman has an excellent, informative essay on State Funeral in Artforum.

Thanks to Michael Campi for the link to Maidan.

P.S. 7 March 2022: I just discovered this illuminating, detailed review of Donbass by John Bennett at The Movie Waffler.

State Funeral (2019).

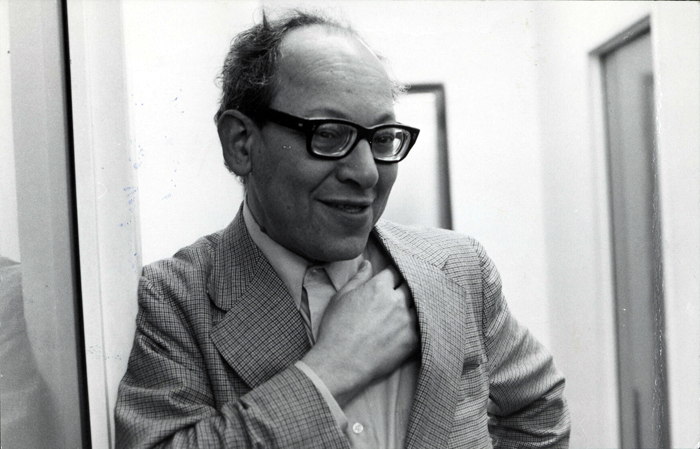

Jacques Ledoux, man of the cinema

Jacques Ledoux.

DB here:

Jacques Ledoux, one of the world’s premiere film archivists, died in 1988, but his example and influence live on. An insatiable cinéphile, a friend to filmmakers around the world, and a tireless collector of films for the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, Ledoux did not have the celebrity status of Henri Langlois. Quietly and modestly, he went about the task of building one of the great film libraries and launching traditions that outlived him. He was at the center of Belgian film culture, which was as cosmopolitan as any you would find in bigger European or American cities.

Central examples of his enterprise: EXPRMNTL, the Knokke-le-Zout experimental film festival; the annual Cinédécouvertes summer festival showcasing films of exceptional ambition that had not yet found a local distributor; and the L’Age d’or prize for films challenging “cinematic conformism.” Martin Scorsese’s The Big Shave (1967) had its premiere at Knokke, where it won the Prix L’Âge d’or. The first winner, in 1955, was Agnès Varda for La Pointe Courte; later winners read like a roster of great directors. The impulse continues to this day. In addition, Ledoux established a distribution branch that allowed student groups and film clubs to borrow prints for their screenings.

There were always obscure legends about his past. “Jacques Ledoux”–“Jacques the Gentle”–was a name he took late in life. Eventually we learned that as a boy he survived the Holocaust by jumping off a train shipping him to Auschwitz. By the end of the 1940s he was participating in the Archive’s activities and he eventually became the director.

Ledoux set about creating a vast showcase of world cinema. Five screenings, two of them silent films, ran every day of the year. Admission prices were low, to permit students to come. At the same time, Ledoux oversaw collections of film technology that formed the basis of educational exhibits. The Archive became the center of the city’s film activities.

Ledoux was a passionate collector, amassing films from far outside Belgium. He was curious about all types of cinema, mass-market and esoteric. When the Nouvelle Vague directors wanted to see a film banned in France, they took the train to Brussels and Ledoux’s domain. The same urge for comprehensiveness informed his efforts to document film history, with filmographies and background information in books published by the Archive. He became a moving spirit of FIAF, the International Association of Film Archives; here you can read about his many accomplishments in that area, as well as his eventual friction with the organization.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

The Archive, now calling itself the Cinematek, has just finished a centenary exhibition devoted to Ledoux. Christophe Piette, organizer of the event, has memorialized it in a lovely multilingual book that gathers reminiscences by Ledoux’s colleagues. There are memoirs by Noël Desmet, Clementine Deblieck, Jean-Paul Dorchain, Hilde Delabie, and Gabrielle Claes, Ledoux’s successor as director. Bernard Eisenschitz, Eric De Kuyper, and P. Adams Sitney offer illuminating appreciations of Ledoux’s contributions. (Sitney’s very full account of Knokke doings is a crucial document in the history of the American avant-garde.) Ledoux’s own voice is represented by a program note for a 1968 science-fiction series. There are many wonderful illustrations–photos, posters, correspondence (Cocteau, Lenica, Akerman). Kristin and I have provided recollections of a man we immensely admired. When you read one of our blog entries on older films, classic or little-known, chances are good that we first saw the film at the Cinematek.

The book is published in a limited edition but is available for purchase at https://cinematek.myshopify.com/en/collections/boeken/products/jacques-ledoux. Every university library with a substantial collection of film literature should acquire a copy!

Anke Brouwers has written a vivid overview of Ledoux’s career for the exposition. Many nifty documents are illustrated.

There are too many citations of Ledoux and the Archive on our site for me to list them. Two extensive ones are “Ledoux’s Legacy” and “Watching movies very, very slowly.” For others, you could try the Search function (using “Brussels”) to find accounts of our many visits.

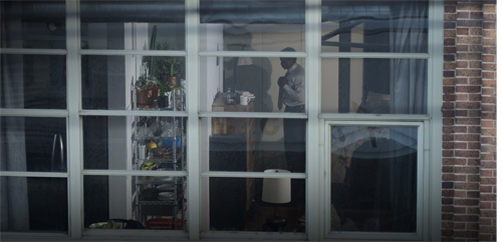

KIMI: She’s here

Kimi (2022).

DB here:

Just when I worried that the solitary-woman-in-peril cycle had ended, along comes Steven Soderbergh’s Kimi on HBO Plus. Following on the fine No Sudden Move from last year, his latest effort shows how an imaginative script (from Friend of the Blog David Koepp), elegant direction, an unpredictable score, and an engagingly eccentric central performance (from Zoë Kravitz) can revivify some classic conventions.

Some critics think that when parodies show up, the genre is on the downturn. The streaming release of The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window (2022) might suggest that the cycle based on The Girl on the Train (2016) and The Woman in the Window (2021) had run its course. But actually, parodies can show up at any point in the life cycle of a genre. The Great K & A Train Robbery (1925) didn’t kill off the western, and Spaceballs (1987) didn’t wipe out space opera. So it’s good to know that the presence of Woman in the House Across the Street etc. doesn’t make a straightforward but sophisticated entry like Kimi any the less sparkling.

It depends on what I’ve called the Eyewitness Plot, and I’ve tried in Revisiting Hollywood to show how that emerged from the flurry of creative activity we find in 1940s studio cinema. Here the protagonist sees what may be a crime and asks the authorities to intervene. There’s enough uncertainty about the incident itself, and about the reliability of the witness, to make the police doubt that there’s been a crime. So the protagonist has to investigate–while becoming a target of violence in turn. Rear Window (1954) is the standard example, but it has many predecessors in fiction, film, and radio, notably The Window (1949). A variant relies not on sight but sound: the protagonist hears something of criminal consequence. That alternative is played out in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) and, later, The Conversation (1974) and Blow-Out (1981).

Koepp and Soderbergh, both connoisseurs of classic Hollywood, understand the power of locking us into the perceptions of the witness while at the same time keeping us aware of the larger context of the action. Rear Window is exceptionally strict in limiting us to what Jeff sees and hears, but even then there is a telltale moment when we’re given information that would seem to contradict his belief that his neighbor has murdered his wife. More common is a balanced narrration that ties us to what the protagonist knows but occasionally strays away to supply backstory and ancillary information–usually, just enough to foster suspense.

That’s enough setup. Major spoilers follow! If you haven’t seen Kimi yet, visit and return.

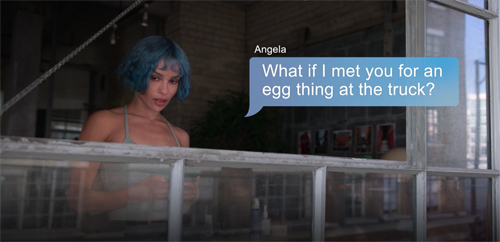

She looks and listens

Angela Childs lives in lockdown. Not just the pandemic but a traumatic sexual assault has made her afraid to leave her Seattle loft, and more basically resistant to emotional contact. She works from home for Amygdala, a company promoting an Alexa/Siri gadget called Kimi. Unlike the competitors, which rely on machine learning, Amygdala has an army of monitors that track actual user dialogues with Kimi in order to correct its errors. Angela is a monitor, and on one recording she hears, muffled by music and noise, what seems to be a murder. After cleaning up a dense recording and inducing a more experienced hacker to find the user’s entire log of Kimi conversations, Angela discovers a crucial one that seems to lead up to the crime.

Here the official reluctance to believe the witness takes the form of an Amygdala executive’s demand to listen to the recording. When Angela insists that the FBI be present for the playback, the corporation takes steps to silence her. The second large section of the film consists of a prolonged chase and, back in her loft, a final confrontation with the men who committed the crime.

The film’s opening establishes, as a sort of intrinsic norm, the alternation between the wider view of the crime’s circumstances and Angela’s limited perspective. The first scene sets up Bradley Hasling awaiting Amygdala’s IPO, but worried because he’s paying off someone for suppressing information about an unnamed woman.

With our curiosity aroused, the plot can afford to introduce us to Angela and her routines in a more leisurely way. Without the Hasling scene, this stretch would be mostly character portrayal, but it gains keener interest as we must wonder how Angela’s fate will intersect with his. Glimpses of Angela fussily making her bed, brushing her teeth, and exercising on her bike also serve to illustrate how she activates Kimi for music and for computer access.

Just as important are the passages of optical POV that show her at her window scanning her street. She looks across at a family in the building opposite, and then looks up and to her left, where she sees the bearded man we’ll learn is called Kevin. He looks back at her.

She swivels her gaze to another window opposite and sees a closed curtain.

Later on the balcony she looks at the window and this time sees Terry, her casual lover, getting ready for work.

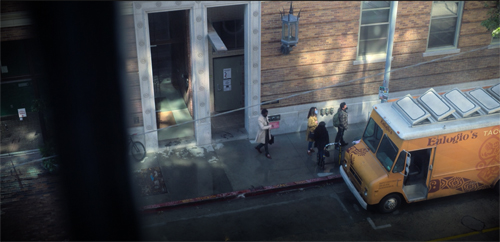

She texts him, and after an external, objective pan shot links the two buildings, she asks Terry if he wants to join her for a breakfast at the food truck down below.

However, she’s afraid to leave the apartment, and her fractured activity is rendered in discordant POV angles. After a shot of her in the shower, we see Terry at the truck, from her usual station point. There’s no lead-in shot of her looking; is she watching from offscreen after the shower, or has the narration worked behind her back, while reminding us of her usual position?

Finally, when she collapses on the floor, unable to leave, we get the same high angle on Terry at the truck, texting her and looking up.

Cut back to her still on the floor. The narration is now operating independent of her vision, but with traces of her viewpoint lingering.

The passage is capped by a shot of her at the window looking down, followed by an optical POV of the food truck, sans Terry.

Another shot of her seals the sequence, but when she pulls away from the window, we get an extra, new angle on her: from outside and above. It’s a fair approximation of what Kevin’s viewpoint on her might be. Yet there’s no shot showing him watching.

The “unclaimed” POV shots that close this scene acknowledge that however much we’re tied to the protagonist’s perceptions, the narration won’t limit us to them–that there is wiggle room to supply extra information, and to imply that our heroine is watched by others. This fluctuating access will become important in the crosscutting that provides the film’s climax.

She flees and fights

The fusion of external viewpoints and subjective ones continues in different ways later. When Angela plays the recordings of the attack, Soderbergh gives us her mental imagery–first as blurred cutaways, then as superimpositions. She’s imagining the assault. Later we’ll learn she has been a rape victim herself.

We’ll later discover that the faces of the murderers are those of the thugs who will pursue her. Yet she hasn’t seen them yet, so she can’t plausibly be visualizing them in the scene.

This is an innovation, I think. In the Forties and since, if these visualized images were to accompany the playback, the faces of the killers would have been indiscernible. Soderbergh is willing to violate plausibility in order to gain economy (introducing us to the thugs) and to continue his initial strategy of rendering subjective experience while also adding information for us.

A milder version of the tactic will be used in the climax, after Angela is captured and lying semi-unconscious in the van. We see her awake and apparently listening to the thugs’ dialogue, while superimpositions suggest the passage of the van through the neighborhood.

Incidentally, these are good examples of the persistence of “Impressionist” cinema techniques from the silent era. Soderbergh had made use of them in Unsane (2018), another film about a woman in peril.

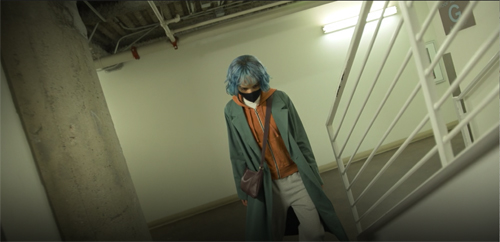

Apart from the prologue showing Hasling’s phone call, the film’s first stretch is confined to Angela’s loft. It’s a classic “bottle” situation, a premise that Koepp is fond of. (Cf. his script for Panic Room, 2002.) It’s Angela’s sympathy for the victim of the crime that propels her out of her bubble into the wider world. Here Zoë Kravitz’s performance takes on a new dimension.

In her loft she’s clipped and brusque, dominating everyone she talks to. Her vulnerability, though, is suggested by her obsessive hand sanitizing. Emphasized by her waving her hands to dry them, it becomes practically a nervous tic.

Once outside, she scoots along, arms jammed to her side, head buried in her hoodie, and body as stiff as Max Schreck’s. She tries to be as locked-in outdoors as she is indoors.

Soderberg compensates for her rigidity with camera technique that’s liberated from the confines of her loft. As Manohla Dargis points out in her review, now the film becomes a procession of canted angles and hurtling camera moves, swooping around her and trying to keep up.

Once back in the loft, however, the framing gets poised again and we’re subjected to a precise exercise in suspense. Close-ups and abrupt changes of angle provide exactly what we need to see at each instant.

And things planted quietly in the opening, particularly Angela’s knowledge of building construction, become crucial to her survival. Kimi proves to be a lifesaving sidekick, proving Hitchcock’s dictum concerning Jeff’s use of flashbulbs to save himself in Rear Window: you should use everything you’ve put into your scene.

One nice felicity: You might expect that Terry would turn out to be the “helper male” of so many women-in-peril plots (e.g., the Joseph Cotten character in Gaslight, 1944). Prototypically, this character rescues the protagonist and provides romantic interest for the future. Koepp’s screenplay shrewdly sets Terry up for this role when Angela looks outside during the gang’s siege and sees Terry’s apartment empty.

Later Terry is shown in a street-level, objective shot, walking to Angela’s building. This violation of the intrinsic POV norm suggests an impending rescue. But that prospect is canceled when he stops as if remembering something and turns back.

He does arrive, but too late to help. Terry’s expression as Angela calls 911 is a perfect capstone for the scene. The same wit flashes out of the epilogue, which suggests she’s broken out of her shell, but she still prudently uses sanitizer.

The domestic suspense thriller focused on a female protagonist remains a popular genre of novels. I devoted a chapter to it in my forthcoming book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. There haven’t been many film adaptations of them since The Woman in the Window, but maybe the neo-Gothic The Girl Before (2021) will unleash more. In the meantime, I’m glad that Koepp and Soderbergh have found ways to give the conventions brisk new life.

David Koepp remarks: “You’re right about the lingering effect of 40s cinema, as you and I have discussed many times. I’d say Sorry, Wrong Number was the direct antecedent here. . . I mean, the party line in Sorry, Wrong Number is basically the Alexa of its time, no?” Interesting in this connection is that the lengthy survey of Angela’s loft in the epilogue shows Kimi no longer there.

Another grace note: KT wondered if the precariously balanced kombucha bottle is psychologically revealing. It turns out to be the consummation of a moment from an earlier Koepp film.

The bottle on the edge of the counter — that was me making good on a setup I did in Secret Window, fifteen years ago. Seriously. There’s a shot in there where Johnny’s character, in a state of high anxiety and agitation, sets a glass down on his kitchen counter hastily, and doesn’t notice it’s only half on the counter. We did seventeen or twenty takes to get exactly the right gravity-defying balance on the edge. It was a pretty literal visual metaphor — you know, he’s on edge.

Thing was, in post-production I realized I had put in a perfect setup, but never paid it off. Why not have the glass fall and smash twenty minutes later, when we’re least expecting it?? Wished I had, never did.

So I used it again in Kimi, but with the (to my mind) required payoff, and at a moment of high tension. So, Angela, in her argument with Terry, is highly agitated, and smacks the bottle down on the counter carelessly, not realizing how close it is to the edge. (The KT hypothesis proves correct!) Angela forgets about it. So do we. Ten minutes later, when we’re all keyed up about something else, SMASH!

Thanks to David for corresponding.

The Hitchcock remark is this: “Here we have a photographer who uses his camera equipment to pry into the back yard, and when he defends himself he also uses his professional equipment, the flashbulbs. I make it a rule to exploit elements that are connected with a character or location. I would feel that I’d been remiss if I hadn’t made maximum use of those elements” (Truffaut/Hitchcock, rev. ed. 1983, 219).

Kimi (2022).