Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Dragons, tigers, one bear

Sawako Decides.

DB here:

As has become our habit, we’re at the Vancouver International Film Festival, gulping down movies. The perennial Dragons and Tigers collection of recent Asian film is especially ripe this year, at over forty-three features and many shorts, and of course there are several other choices, across ten venues, competing for your eyeballs. Herewith, my first dispatch from this sunny, hospitable city. Kristin will follow up soon.

A girl, a boy, and many guns

She’s completely ordinary, “below-middle,” as she proclaims. Her contribution to a conversation is always a couple of steps behind. She spends her nights watching TV and guzzling beer. She has lost five jobs and been dumped by five boyfriends. Her main relaxation seems to be colonic irrigation. But when she’s fired and her father lies dying, she returns to her hometown to take over his clam-processing factory. She brings in tow her latest paramour, a twitchy ex-toy-designer who enjoys knitting.

Such is Sawako, who has the face of an anime princess and the mind of . . . well, that’s part of the problem. Psychologically, she’s the opposite of those fast-comeback youngsters spraying American indies with quirk. She mopes in her father’s factory, absently minds her boyfriend’s daughter, shrugs off the malice of her former teen friend, and ignores gossip about why she left town in the first place. Nothing can shake her obdurate passivity. She won’t fight. With beer as her only solace, Sawako seems not the stuff of drama at all.

But drama, tradition tells us, pivots on decisions (usually bad ones). Sawako Decides surrounds a woman resigned to misfortune with a range of eccentrics who do take action, sometimes recklessly. There are the older women who work in the processing plant, the faithless boyfriend with his powder-blue sweaters, the vindictive ex-friend, the alcoholic father who rips off his IV for a fight, even a college girl doing research on toxic clams. When Sawako finally chooses to do something, she’s acting, she says, for all the “below-middle” people—that is, nearly all of us. Associated throughout with body wastes, she turns the tide: Even the feces she spreads on the family garden yield a giant watermelon. The film ends with a trim long take in which Sawako finally blows her top and finds an agreeably aggressive use for her father’s bones. Ishii Yuya’s film shows how the blankest of characters can, if treated with wary respect, yield engaging cinema.

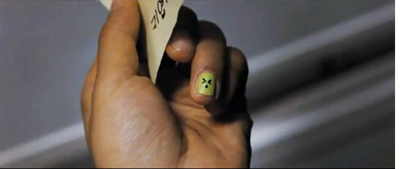

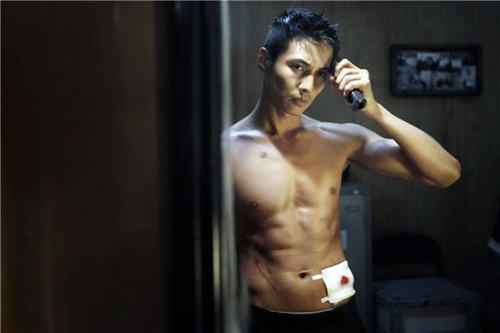

Won Bin is probably best known to Western audiences as the scatty, tormented son in Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, but he’s become a major Korean heartthrob. I know this because of the collective gasps and shrieks that greeted moments of The Man from Nowhere, a grisly action picture by Lee Jeong-Beom. Won plays a retired government agent running a pawnshop in a seedy neighborhood. He reenters the underworld to rescue a neighbor woman’s daughter, snatched by a drug gang for a little child labor and organ-stripping. He is a Bourne-style killing machine, and he is given plenty of chance for some rousing brawls and gunplay (though most of his fighting skills can be credited to editing and blur-o-vision camerawork). Mountainous, bug-eyed, and ominously silent bad guys round out the cast. Director Lee is also shrewd enough to feed the fanbase. There are some touching moments between the girl and the hitman; she even gives him a decorative fingernail while he sleeps. The film’s pin-up image shows Won, stripped to the waist at the mirror, clipping his hair, a bloodied groin-level bandage artfully completing the ensemble. (If you can’t wait, see the end of this entry.) A limited North American release comes later this month.

Excess, two varieties

I’ve written briefly about Sono Sion’s perverse coming-of-age tale Love Exposure, and this year’s Vancouver fest brings us his latest, Cold Fish. Who would have thought that business rivalry between two tropical-fish vendors would lead to the carnage we see here? Meek Shamoto has a sexy wife and a disobedient teenage daughter. An aggressively friendly rival, Murata, owns a much bigger shop and offers to take the wayward Mitsuko under his wing. Soon Murata reveals that he plunges as voraciously into murder as he does into fish connoisseurship, and Shamato is caught up in the untidy business of human butchery.

A charnel-house of copulation and dismemberment, the film takes place in a vacuum; a police investigation comes virtually as an afterthought. Cold Fish is more linear and genre-bound than Love Exposure, but when the quiet march of Mahler’s first symphony signals the onset of dread you recall the wilder side of the earlier movie. Also carrying over is the blasphemous use of Christian iconography, associated here with slaughter and child abuse. The film is in the tradition of The Family Game and other dismantlings of Japanese domesticity. Once again, you can find as much lust and murder as you like just by looking into the nuclear family. In this case, the choice offered to the father is straightforward: be a wimp or be a brute. Sono aims to outrage, but once you know that you’re in for a bloodbath, you settle comfortably in for an engrossing exercise in splatter, Japanese-style.

At the other extreme is The Drunkard, Freddy Wong’s adaptation of Liu Yichang’s well-regarded novel about a dissolute writer. Lau wants to be the Hemingway of Hong Kong, but his addiction to alcohol and his inability to love drive him into writing film scripts, pulp fiction, and eventually pornography. The fear of selling out your artistic ideals may not strike a chord in the age of Damien Hirst, but in the 1960s, the novel’s epoch, it held sway over literary culture. Lau’s struggle is presented as an oscillation between his collaboration on a literary magazine and his grubby business dealings with movie producers and publishers. In between, and constantly, he smokes and drinks. The women along his downward path include a seventeen-year-old temptress who has read Lolita, a sincere working woman who offers him lodging and sex, and an aged landlady who thinks he’s her son. His drunken refusal to sympathize with their needs brings sorrow to nearly all and death to a couple of them.

The Drunkard is shot in an unusual style. There are almost no long shots; the framing above is about as far back as the camera gets. Nearly everything happens in medium-shot and close-up. Wong was partly making a virtue of necessity, since streets and shops of the Hong Kong of the 1960s could not be reconstructed on the film’s budget. The positive result is an unrelenting concentration on Lau and repetitive bits of his behavior–gesturing with a cigarette, pouring whisky, or fading into a blackout. From scene to scene, we’re confined to his awareness, broken by fragmentary memories of wartime Japanese invasion. Only after his binges do we learn how viciously he acted when under the influence.

This tightly circumscribed world is enhanced by shots focusing on only a curtain edge or a streaked whisky glass, while people and surroundings drown in a blur. Shot on the Red camera, The Drunkard shows that high-definition digital is perfectly capable of giving foregrounds or backgrounds a hallucinatory softness. That softness, you could argue, is a correlative for the drunkard’s vision, locked on details and oblivious to the flux of human passions around him. In its effort to render the glowing warmth of alcohol, Wong and his cinematographer Henry Chung have given digital cinema a decisively subjective turn.

Two men and a sofa

Ho Wi Ding’s Pinoy Sunday is a heartfelt, low-pressure comedy-drama that makes some telling points about cultural dislocation. Dado and Manuel are Filipino “guest workers” in Taiwan. Friends since high school, they work in a bike factory and live in the factory dormitory. In their dreams they imagine installing a lavish raspberry-bright sofa on the dorm roof where they could lounge, drink beer, and look at the stars. One day, visiting Pinoy on break, they see that very sofa abandoned on the street.

Emigrant Filipino workers fill the lower-rank jobs in many Asian countries, and I’ve seldom seen fiction films show the texture of their lives. Through Dado’s phone conversations with his family, the pain of loss comes through. He buys his daughter a Barbie for her birthday, even while he carries on an affair with an émigré woman (who herself has a husband and family back home). Manuel is on the make, but with winning naivete has a knack for picking the wrong women to idealize (hookers, policewomen). In a way, the sofa becomes the tangible emblem of not just material comfort but the men’s aspiration for a more stable life.

With something of the wistful satire of 1960s Eastern European films like Intimate Lighting or The Fireman’s Ball, Pinoy Sunday turns an anecdote into a mini-saga. (It was inspired by Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe.) At the canonical turning point (circa 28:00), Manuel persuades Dado to carry the sofa back to their dorm before the gates close. The ensuing misadventures recall Laurel and Hardy, but with stronger sentiment.

Their journey reminds them they are outsiders. A TV reporter thinks they’re Malaysian. Trying to explain an accident to a cop puts them at a disadvantage. Their inability to speak Mandarin gives us a crash course in how gestures, English phrases, and situational logic are pieced together to communicate across cultures. At the height of the men’s frustration, there is a poignant musical interlude that evokes magic realism, but that moment is immediately undercut by sober reality. Yet our concern for these two resilient strivers is rewarded with a sort of happy ending.

Finally, the bear of this entry’s title is Alex Law’s Echoes of the Rainbow, the Hong Kong film that won the Crystal Bear at this year’s Berlin festival. I haven’t seen it yet but I hope eventually to pass you some words about it.

The Man from Nowhere.

The buddy system

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

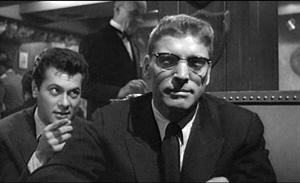

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

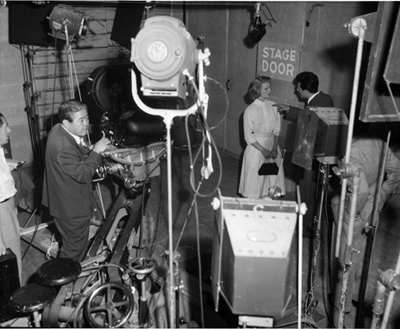

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

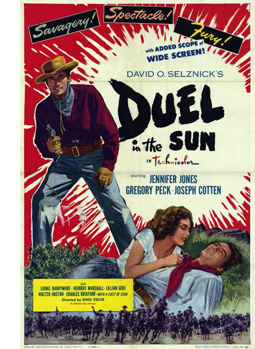

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

What makes Hollywood run?

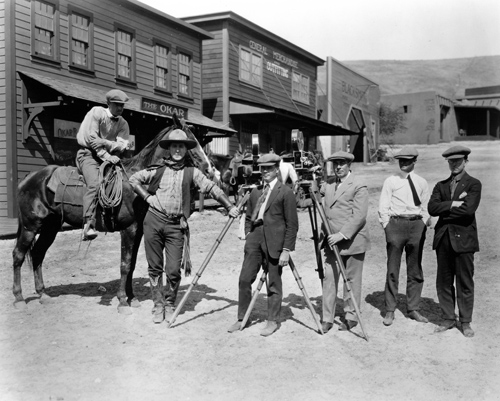

William S. Hart and crew at Inceville, 1910s.

DB here:

For decades most people had a sketchy idea of The Hollywood Studio Film. Boy meets girl, glamorous close-ups, spectacular dance numbers or battle scenes, happy endings, fade-out on the clinch. But even if such clichés were accurate, they didn’t cut very deep or capture a lot of other things about the movies. Could we go farther and, suspending judgments pro or con the Dream Factory, characterize U. S. studio filmmaking as an artistic tradition worth studying in depth? Could we explain how it came to be a distinctive tradition, and how that tradition was maintained?

In 1985 Routledge and Kegan Paul of London published The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote it. Since it’s rare for an academic film book to remain in print for twenty-five years, we thought we’d take the occasion of its anniversary to think about it again. Those thoughts can be found in the adjacent web essay, where we three discuss what we tried to do in the book, spiced with comments about areas of disagreement and more recent thoughts. This blog entry is just a teaser.

A touch of classical

John Arnold, a Bell & Howell camera, and Renée Adorée in 1927.

The prospect of analyzing Hollywood as offering a distinctive approach to cinematic storytelling emerged slowly. The earliest generations of film historians tended to talk about the emergence of film techniques in a rather general way. For example, historians were likely to trace the development of editing as a general expressive resource, appearing in all sorts of movies. While they recognized that, say, the Soviet filmmakers made unusual uses of this technique, writers still tended to think of editing as either a fundamental film technique or a very specific one—e.g., Eisenstein’s personal approach to editing.

An alternative approach was to understand the history of film as an art as a stream of cinematic traditions, or modes of representation, within which filmmakers worked. From this angle, there was a Hollywood or “standard” or “mainstream” conception of editing, and this didn’t exhaust all the creative possibilities of the technique. But it went beyond the inclinations of any particular director. People had long recognized that there were group styles, like German Expressionism and Italian Neorealism, but it took longer to start to think of mainstream moviemaking as, in a sense, a very broad and fairly diverse group style.

In the late 1940s André Bazin and his contemporaries started to point out that different sorts of films had standardized their forms and styles quite considerably. Bazin attributed the success of Hollywood cinema to what he called “the genius of the system.” In my view, his phrase referred not to the studio system as a business enterprise but rather to an artistic tradition based on solid genres and a standardized approach to cinematic narration. This artistic system, he suggested, had influenced other cinemas, creating a sort of international film language.

The idea that there was a dominant filmmaking style, tied to American studio moviemaking, was developed in more depth during the 1960s and 1970s. Christian Metz’s Grande Syntagmatique of narrative film pointed toward alternative technical choices available in the “ordinary film.” Raymond Bellour’s analysis of The Birds, The Big Sleep, and other films pointed to a fundamental dynamic of repetition and difference governing American studio cinema. Somewhat in the manner of Roland Barthes’ S/z, Thierry Kuntzel’s essays explored M and The Most Dangerous Game looking for underlying representational processes that were characteristic of studio films. From a somewhat different angle, in the book Praxis du cinema and later essays Noël Burch traced out a dominant set of techniques that formed what he would eventually call the “Institutional Mode of Representation.” The Cahiers du cinéma critics famously posited different categories of filmic construction, each one tied to the representation of ideology. In English, Raymond Durgnat was an early advocate of studying what he called the “ancienne vague,” the conventional filmmaking that young directors were rebelling against.

The trend was given a new thrust by the British journal Screen, which disseminated the idea of a “classical narrative cinema,” a mode of representation characterized by distinctive dynamics of story, style, and ideology. Perhaps the most emblematic article of this sort was Stephen Heath’s in-depth analysis of Touch of Evil. Over the same years a new generation of film historians was studying early cinema with unprecedented care, and they too were finding a variety of modes of representation at work in filmmaking of the pre-1920 era.

The effect was to relativize our understanding of Hollywood. Mainstream U. S. commercial filmmaking wasn’t the cinema, merely one branch of film history, one way of making movies. Breaking a scene into a coherent set of shots, to take the earlier example, wasn’t Editing as such. It was one creative choice, although it had become the dominant one. And what made Hollywood’s brand of coherence the only option? Eisenstein, Resnais, Godard, and other filmmakers explored unorthodox alternatives.

Nearly all of the influential research programs of the period emphasized the film as a “text.” This wasn’t surprising, since several of the writers were working with concepts derived from literary semiotics and structuralism. At the same period, other scholars were developing ideas about Hollywood as a business enterprise. Douglas Gomery, Tino Balio, and a few others were showing that the studio system was just that—a system of industrial practices with its own strategies of organization and conduct. But most of those business studies did not touch on the way the movies looked and sounded, or the way they told their stories.

Could the two strains of research be integrated? Could one go more deeply into the films and extract some pervasive principles of construction? And could one go beyond the films and show how those principles of style and story connected to the film industry?

The prospect of integrating these various aspects—and, naturally, of finding out new things—intrigued us.

Secrets of the system

Main Street to Broadway (1953, MGM release). Cinematographer James Wong Howe on left.

The overall layout of CHC tried to answer these questions while weaving together a historical overview. Part One, written by me, provided a model or ideal type of a classical film, in its narrative and stylistic construction. Part Two, by Janet, outlined the development of the Hollywood mode of production until 1930. In Park Three, Kristin traced the origins and crystallization of the style, from 1909 to 1928. Part Four included chapters by all three authors on the role of technology in standardizing and altering classical procedures during the silent and early sound era. In Part Five Janet resumed her account of the mode of production, tracing changes from 1930 to 1960. The technology thread was brought up to date in Part Six, where I discussed deep-focus cinematography, Technicolor, and the emergence of widescreen cinema. Part seven, which Janet and I wrote together, pointed out implications of the study and suggested how Hollywood compared with alternative modes of film practice.

Clearly, CHC was several books in one. Janet could easily have written a free-standing account of the mode of production. Kristin could have done a book on silent film technique and technology. I could have focused on style and form, using sound-era technologies as test cases. The point of interspersing all these studies (and creating a slightly cumbersome string of authorial tags within sections) was to trace interdependences. For instance, Kristin examined the emerging stylistic standardization in the 1910s. Janet showed how that standardization was facilitated by a systematic division of labor and hierarchy of control, centered around the continuity script. At the same time, the organization of work was designed to permit novelties in the finished product, a process of differentiation that is important in any entertainment business.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

In the late 1920s, for instance, sound recording made the camera heavier than the tripods of the silent era could bear. Supply firms engineered “camera carriages” that could wheel the beast from setup to setup. But this development occurred soon after filmmakers had noticed the expressive advantages of the “unleashed camera” in German films and some American ones. So the camera carriage became a dolly, redesigned to permit moving the camera while filming. It’s not that there weren’t moving-camera shots before, of course, but with the camera permanently on a mobile base, tracking and reframing shots could play a bigger role in a scene’s visual texture. Similarly, studio demands for ways of representing actors’ faces in close-ups forced Technicolor engineers back to their drawing boards again and again. Once the problem of rendering faces pleasant in color was solved, filmmakers could then redesign their sets and adjust their make-up to suit the vibrant three-strip process. And the interaction of work, tools, and style triggered larger cycles of activity. The need to pool information about stylistic demands and technological possibilities helped foster the growth of professional associations and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

This give-and-take among the studios, the supply sector, and the stylistic norms had never been discussed before, and we couldn’t have done justice to it in separately published books. Nor could isolated studies have easily traced how industrial discourses—the articles in trade journals, the communication among the major players—helped weld the mode of production to artistic choices about filmic storytelling.

The Classical Hollywood Cinema was generously reviewed, in terms that made us feel our hard work had been worth it. Books we’ve written since haven’t been so widely acclaimed. (Nothing like peaking young.) We’re grateful to the reviewers who praised the book, and to the teachers and students who have strengthened their biceps by picking it up to read. Of course there are others who don’t consider the project worthwhile; the TLS reviewer called it “sludge.” Probably nothing we say in the accompanying essay will persuade those readers to take a second look. Without responding to all the criticisms the book received (that would take a book in itself), our accompanying essay tries to position this 1985 project within our current lines of thinking.

We studied how Hollywood routinized its work, but that doesn’t mean that we think division of labor is always alienating. It may produce a much better outcome than do the efforts of a solitary individual. For us, that’s what happened during this rewarding exercise in collaboration.

Our thinking was shaped by many sources; here are some of them.

For André Bazin on “the genius of the system,” see “La Politique des auteurs,” in The New Wave, ed. Peter Graham (New York: Doubleday, 1968), pp. 143, 154, and “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), pp. 23-40. Christian Metz explains the Grande Syntagmatique of the image track in “Problems of Denotation in the Fiction Film,” Film Language, trans. Michael Taylor (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 108-146. Raymond Bellour’s essays of the period are available in The Analysis of Film. Thierry Kuntzel’s essay on The Most Dangerous Game was translated into English as “The Film-Work 2,” Camera Obscura no. 5 (1980), 7-68. An important gathering of essays in this line of inquiry is Dominique Noguez, ed., Cinéma: Théorie, lectures (Paris: Klincksieck, 1973).

Noël Burch’s early ideas are set out in Theory of Film Practice, trans. Helen R. Lane (New York: Prager, 1973). Even more important to our project was Noël Burch and Jorge Dana, “Propositions,” Afterimage no. 5 (Spring 1974), 40-66, and Burch’s To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film (London: Scolar Press, 1979), available online here.

Raymond Durgnat’s series, “Images of the Mind,” deserves to be republished, preferably online. The most relevant installments for this entry are “Throwaway Movies,” Films and Filming 14, 10 (July 1968), 5-10; “Part Two,” Films and Filming 14, 11 (August 1968), 13-17; and “The Impossible Takes a Little Longer,” Films and Filming 14, 12 September 1968), 13-16. Stephen Heath’s analysis of Touch of Evil may be found in “Film and System: Terms of Analysis,” Screen 16, 1 (Spring 1975), 91-113 and 16, 2 (Summer 1975), 91-113.

Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (London: Starword, 1983) works in comparable areas to CHC, though without our interest in industry-based sources of stability and change. The newest edition is here.

Tino Balio’s courses and his collection The American Film Industry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) had a substantial influence on us. He has been a wonderful friend and guide for us all since the 1970s. Our friendship with Douglas Gomery dates from our early days in Madison. Many conversations, along with his teaching in our program, shaped our thinking. A good summing up his of decades of work on the business and economics of Hollywood is The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

Some of the stylistic traditions discussed in this entry are discussed in my On the History of Film Style. Several blog entries on this site fill in more details; click on the category “Hollywood: Artistic traditions.”

PS 26 September 2010: Douglas Gomery reminds me that the idea of sampling Hollywood films in an unbiased fashion–one feature of our method in CHC–was suggested to us by Marilyn Moon, economist extraordinaire. I’m happy to thank Marilyn, along with Joanne Cantor and Douglas himself, who helped us devise a sampling procedure.

Actors and set for Blondie Johnson (Warners, 1933).

John Ford, silent man

John Ford on the set of Air Mail (1932).

DB here:

This is the busiest installment of Cinema Ritrovato I can recall. We scarcely have time to sleep, let alone blog. The coordinators Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée have outdone themselves in offering something for everybody, from early films to postwar French and Italian rarities up through a tribute to Stanley Donen and special screenings of The Leopard and Metropolis. Our attention has been riveted by the 1910 programs and an extensive collection of films directed by Alberto Capellani, a little-known master of silent film.

One headliner is the early Ford series: all his surviving silents, plus a selection of rarely-seen talkies. The first one screened, The Black Watch (1929), concentrates on intrigue in the Khyber Pass during World War I. Captain King is assigned to India while the rest of his Scots regiment is sent to Europe. In India, King masterminds the defeat of the forces of Yasmani, a woman who has been taken as sort of a goddess by her followers. The central section, involving Yasmani’s passion for King and his betrayal of her, seems to me sketchy and rushed; Ford’s real interest, not surprisingly, is in the rites of comradeship among the Black Watch. Twenty-two of the film’s 91 minutes are taken up with the opening dinner celebrating the regiment, conducted while King gets his assignment. Since his mission is secret, he abandons his comrades and suffers their opprobrium. A bookended sequence at the close shows him returning to the Watch as, in the trenches of war, they hold another dinner, complete with ruffles and flourishes.

Some of the central portion was directed by Lumsden Hare, but it too has some striking moments, perhaps most memorably the display of Yasmani’s powers when she conjures up an eerie vision of the European battlefield in a glowing crystal ball. The war sequences have the dank Expressionist look that Murnau brought to Fox and that Ford exploited in Four Sons (1928). There are as well touching train-station farewells between brothers and between father and daughter, all of which seem very Fordian. Overall, Ford finds ways to avoid the multiple-camera shooting common to early talkies, often using offscreen dialogue during reaction shots.

Also fairly free of multicamera work was The Brat (1931). Like many talkies derived from a creaky Broadway play, it entices us with a “cinematic” curtain-opener. Cops (including the young Ward Bond) hustle perps into night court, all captured in a flurry of high and low angles, bursts of deep space, and swift tracking shots. Afterwards things slow down, enlivened by some social satire (the pretentious novelist writes with a quill pen), a few sight gags (an artist’s muscled model who discovers he’s been rendered in a faux-Cubist image) and an all-in grappling fight between a society dame and a girl from the other side of the tracks. According to Ford, the fight got its impact from the fact that the actresses couldn’t stand each other.

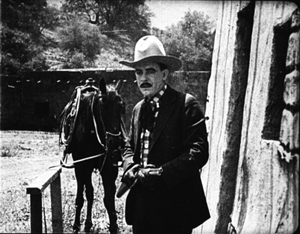

The first silent Fords were introduced by Joe McBride. “When the real West ended,” Joe remarked, “the cinematic West began.” Born soon after the closing of the frontier, Ford was fascinated by cowboys and Native Americans. Early filmmakers were to a surprising extent celebrating the stoic Indians uprooted and forced to give up their way of life, and this resonated with Ford. The elegiac quality we find in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and other late films, Joe suggested, was already there in the genre. Ford’s own first Westerns, thanks partly to the presence of Harry Carey, carry an air of resignation to history. Even the fragmentary sequences surviving from The Secret Man (1917), in which Harry must sacrifice his freedom to save a little girl, have a severe melancholy.

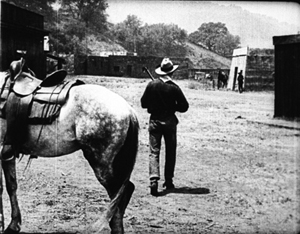

Hell Bent (1920) has long been famed for its flashy, unrepeatable shot: A carriage pulled by horses tumbles into a ravine; the camera tilts down to follow the crash; and then the horses, freed at the top, come hurtling back into the frame to pass the wreckage. Otherwise the film is consistently agreeable, suffused with Fordian camaraderie among drunks and respect between hero and villain. This last element is starkly dramatized when Harry and his adversary, having wounded each other in a gun duel, must crawl through the desert together.

On my first viewing, I didn’t see in Hell Bent the inventiveness and grace notes I admire so much in Ford’s first feature, Straight Shooting (1917). As we’ve mentioned before, this film shows a mastery of the classical Hollywood style that emerged in the late 1910s. It bears comparison with William S. Hart films of the period, high points of filmmaking craft. Late in the plot Ford give us a shootout with ever-tighter framings that could have come out of Leone.

Whether Ford invented this particular piece of cinematic rhetoric we can’t say; too many silent films are lost. But coming from a 23-year-old filmmaker in his first feature, this remains a remarkably assured use of the continuity editing system for 1917.

Ford’s debt to Griffith has often been noted, and in this movie it turns up in unexpected ways. At one point Joan tenderly puts away the plate her dead brother had used, as if to preserve it. Later, Ford recalls the gesture when the cabin is under siege and bullets blow apart other plates on the sideboard. But Ford has already quietly suggested an association between brother Ted and Cheyenne Harry; as Joan kisses the plate before putting it away, Ford cuts to Harry outside, and then back to Joan slipping the plate into a drawer. Using the then-current technique of a “ruminative cut”, the editing suggests that Joan may also be thinking of Harry, and he of her. The idea of Harry replacing Ted is made explicit at the end when Sims plaintively asks Harry, “You be my son.”

The Griffith influence is particularly acute in Straight Shooting’s climax, when the farmers are under siege in the Sims cabin. Horsemen gallop around the cabin as hired gunmen pepper it with bullets. Meanwhile, Cheyenne Harry has persuaded Black-Eyed Pete’s gang of outlaws to rescue the settlers, and Ford gives us a rousing passage of rapid crosscutting. It’s a canonical last-minute rescue, straight out of the climax of The Birth of a Nation (191t5).

Or more particularly, I think, out of The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1914). Griffith commonly staged interior scenes with doors at the left and right of the frame, letting actors play laterally. The strategy can be considered somewhat theatrical, in that we never see the “fourth wall” that would in reality enclose the characters.

But this leads to problems when you want to show your characters surrounded. In Elderbush Gulch, the settlers are besieged by encircling Indians. At one point, Griffith cuts from the exterior of the cabin to the interior, and to convey the sense of enclosure he has one of the settlers firing “through” the fourth wall, as if over the heads of the audience!

This is an awkward compromise, but at least give Griffith credit for grasping that his dollhouse playing area doesn’t fully render a realistic space. In Straight Shooting Ford provides a more three-dimensional rendering of interiors. Even though most scene in the Sims cabin lacks Griffith’s side walls, the set yields layers of depth, and the famous door in the back of the set opens on to the porch and the farm outside.

During the gunmen’s siege, we get a strong sense of enclosing space by virtue of the cuts of men firing from different angles. In addition, the cabin interior displays a little more angular depth.

But even Ford can’t escape compromises. We never see the space “behind us” in the Sims’ cabin, and as the farmers take up positions at windows, Ford shows us old Sims readying to fire by turning toward the camera and, like Griffith’s settler, aiming through the fourth wall.

The two shots of Sims in this posture go by fast, and they’re less noticeable because the siege hasn’t quite begun. Still, the anomaly indicates that in this setting Hollywood technique still doesn’t give the sense of a wraparound space that we get in the exterior scenes, like the shootout. A few years after Straight Shooting, American directors would master the ability to build up a four-walled interior through careful cutting. Those techniques would then be exploited for dramatic effect, as in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

More to come, but now I must rush off to a morning of early film! If you’re hungry for more in the meantime, visit our category Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato for highlights of earlier years.