Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Glancing backward, mostly at critics

DB bere:

As Freud’s mom says in Huston’s film, “Memory plays queer tricks, Siggy.” Herewith, some journeys into the past, launched on a lazy June afternoon.

Ten-best lists are nothing new. The New York Times ran them in the 1930s. Here’s one for 1940 (NYT 29 Dec 1940, p. X5).

The Grapes of Wrath, The Baker’s Wife, Rebecca, Our Town, The Mortal Storm, Pride and Prejudice, The Great McGinty, The Long Voyage Home, The Great Dictator, and Fantasia.

The author’s runner-up titles include Of Mice and Men and The Philadelphia Story. Pretty tasteful by today’s standards, no? Who came up with a list including Hitchcock, Borzage, Sturges, Pagnol, Chaplin, Disney, Milestone, Cukor, and Ford twice?

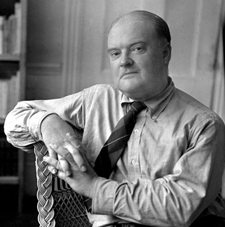

None other than Bosley Crowther, long-serving Times reviewer who became the emblem of middlebrow taste in endless polemics (including some I’ve mounted). Who knew he was a closet auteurist?

Winchester ’73 (1950).

Now try this one.

The movies live on children from the ages of ten to nineteen, who go steadily and frequently and almost automatically to the pictures; from the age of twenty to twenty-five people still go, but less often; after thirty, the audience begins to vanish from the movie houses. Checks made by different researchers at different times and places turn up minor variations in percentages; but it works out that between the ages of thirty and fifty, more than half of the men and women in the Unites States, steady patrons of the movies in their earlier years, do not bother to see more than one picture a month; after fifty, more than half see virtually no pictures at all.

This is the ultimate, essential, overriding fact about the movies. . . .

Yes, another oldie, this time from Gilbert Seldes’ book The Great Audience (1950). What we’ve been told for years was characteristic of our Now—the infantilization of the audience—has been in force for at least sixty years.

By the way, here are some US features released in 1950: Father of the Bride, Gun Crazy, House by the River, In a Lonely Place, Julius Caesar, Mystery Street, Night and the City, Panic in the Streets, Rio Grande, Shakedown, Stage Fright, Stars in My Crown, Summer Stock, Sunset Blvd., The Asphalt Jungle, The Baron of Arizona, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, The Gunfighter, The Third Man, Twelve O’Clock High, Union Station, Wagon Master, Where the Sidewalk Ends, Whirlpool, Winchester ’73, and probably some other good movies I haven’t seen.

Perhaps not a luminous year, but I’d settle. Especially compared with 2010. Did kids just have better taste then?

Beyond reviewing

Most people conceive a film critic as a film reviewer. The review is a well-established genre, and we all have its conventions in our bones. At a minimum, you synopsize the plot, comment on the acting, mention the pacing or the cinematography, throw in some wisecracks, and recommend or condemn the film. Good reviewers do these things well, but the genre remains a limited one.

Crowther was a reviewer; Seldes was something more. But how to define that extra something? Two long-lived heavyweights can help us.

In the 1935 essay “The Literary Worker’s Polonius: A Brief Guide for Authors and Editors,” Edmund Wilson spells out what he takes to be the duties and genres of literary labor. At the time, the “New Criticism” in the universities had barely gotten started, so most literary criticism Wilson encountered was journalistic and belletristic—that is, reviewing.

Accordingly, Wilson distinguishes different types of reviewers. There the people who simply need work. There are literary columnists who pump out observations on the latest books. There are people who want to write about something else; that’s when you use the book under review as a pretext to ride your hobby horse. There are the reviewer experts, as when a philosopher is called in to review a book of philosophy. Then there’s the rarest, the “reviewer critics.” Here is why such creatures are rare.

Such a reviewer should be more or less familiar, or ready to familiarize himself, with the past work of every important writer he deals with and be able to write about an author’s new book in the light of his general development and intention. He should also be able to see the author in relation to the national literature as a whole and the national literature in relation to other literatures. But this means a great deal of work, and it presupposes a certain amount of training.

In sum, the best critic has to be very, very knowledgeable. But is knowledge enough?

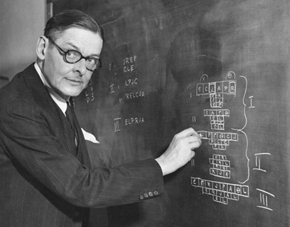

T. S. Eliot, it’s often said, believed that the only qualification of a critic is to be very intelligent. (One example of this claim is here.) What Eliot actually wrote is more interesting. His 1920 essay “The Perfect Critic” is considering Aristotle as a theorist of literature. Of The Poetics he notes:

In his short and broken treatise he provides an eternal example—not of laws, or even of method, for there is no method except to be very intelligent, but of intelligence itself swiftly operating the analysis of sensation to the point of principle and definition.

The final clause is a good description of what I take “poetics” to be as applied to film. We analyze effect (“sensation”) so to discover not laws but principles (governing a genre, a trend, a style, whatever) that we in turn articulate (“definition”). In this analysis, we don’t use a method—that is, I take it, a prior commitment to a system of thought that blocks our seeing the object in its own terms.

Contrary to the common modern view that our personal feelings and ideas color everything we think about, Eliot seems to advocate a more objective way of thinking. Aristotle the theorist is praised because “in every sphere he looked solely and steadfastly at the object.” His search for the principles underlying tragedy, comedy, and epic is contrasted with the dogmas of Horace, the “lazy critic” who offers us precepts, tips from the top about laws to be obeyed. (Sound familiar from screenplay manuals?)

Aristotle, Eliot thinks, was endowed with “universal intelligence”: “He could apply his intelligence to anything.” Such a gift overrides the sort of specialized inquiry that yields “methods.” I read “The Perfect Critic” as recommending that critics try to combine their sensitivity to nuance with Aristotelian intelligence:

Aristotle had what is called the scientific mind—a mind which, as it is rarely found among scientists except in fragments, might better be called the intelligent mind. For there is no other intelligence than this, and in so far as artists and men of letters are intelligent (we may doubt whether the level of intelligence among men of letters is as high as among men of science) their intelligence is of this kind.

This is what it is to be “intelligent” in Eliot’s sense: to be wide-ranging, rigorous, and committed to understanding the artwork both as unique object and embodiment of principle. He finally spells it out in his praise for the Symbolist Remy de Gourmont:

Of all modern critics, perhaps Remy de Gourmont had most of the general intelligence of Aristotle. An amateur, though an excessively able amateur, in physiology, he combines to a remarkable degree sensitiveness, erudition, sense of fact and sense of history, and generalizing power.

So Wilsonian erudition and historical knowledge aren’t enough. You need sensitivity, “a sense of fact,” and “generalizing power”—the ability to see larger implications and principles at work in what you’re writing about. In short, the best critics don’t shy away from probing ideas.

The general go

Where do the ruminations of Wilson and Eliot leave us with writers who go beyond reviewing? Let’s go back to Seldes.

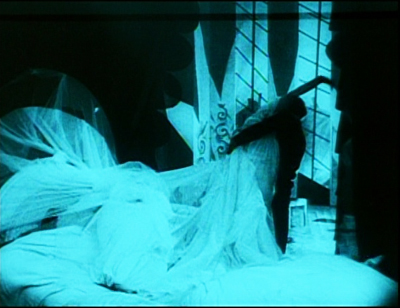

He became one of our best American critics, in fact one of our first media critics, thanks to his “generalizing power.” The 7 Lively Arts (1924) was a trailblazing defense of Tin Pan Alley, comic strips, vaudeville, jazz, and films. Reacting against “genteel” taste, Seldes believed that the bursts of exaltation to be found in the “minor” arts were as profound as anything to be found elsewhere. “Our experience of perfection is so limited that even when it occurs in a secondary field we hail its coming.” Such perfection is to be found, he says, in an instant in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, when Cesare seizes Jane and the bed curtains snag her gown. He starts with what Eliot called “sensation,” the piercing arousal.

A moment comes when everything is exactly right, and you have an occurrence—it may be something exquisite or something unnamably gross; there is in it an ecstasy which sets it apart from everything else.

But Seldes goes beyond noting moments that give him a buzz. He tries to explain how and why the vulgar arts can arouse us. It’s hard for us now to realize that what we take for granted as vital popular culture was scorned by the much of the intelligentsia. In 1924 Seldes set out on a crusade to convince his readers that the Keystone Kops, Flo Ziegfeld, Irving Berlin, ragtime, and Fanny Brice offered more of genuine artistry than the Bogus Arts (we’d say middlebrow) that were then ruling high culture. In 1924, this was a thunderbolt:

The daily comic strip of George Herriman (Krazy Kat) is easily the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.

If the best critics offer not only opinions but information and ideas to back them up, The 7 Lively Arts had both in abundance. Seldes begins the book with the suggestion that the consolidation of the film industry, and particularly the establishment of Triangle, Kay-Bee, and Keystone, was the turning-point in the history of American film. But instead of the usual litany of praise for Griffith’s and Ince’s discovery of “cinematic” storytelling, Seldes condemns them as too quickly seduced by extravagant spectacle. The journeyman Mack Sennett stuck to making “the most despised, and by all odds the most interesting, films produced in America. . . . He is the Keystone the builders rejected.” Far more than the work of Griffith and Ince, Sennett’s comedies exploit what cinema is best suited for: chases, crashes, explosions, “locomotives running wild, yet never destroying the cars they so miraculously send spinning before them. . . . And all of this is done with the camera, through action presented to the eye.”

Seldes wrote about radio, dancing, and other pastimes, but films were his special love. An Hour with the Movies and the Talkies (1929) and The Movies Come from America (1937) combine historical knowledge with subtle appreciation of the forces operating on studio picturemaking. These books thrum with ideas. For instance, Seldes defends the director as the key creative artist in cinema. One reason is that only the director can control pacing.

The director is responsible for the general go of a picture, for making it run off neatly, for controlling the speed of its various parts, for seeing that a romantic episode does not race along while a melodramatic conversation lags. He is, or ought to be, responsible for the interruptions of the main action of the picture so that a comic interlude is not placed too near to the climax of a tragic one, but only near enough to give more intensity to the emotion.

What about the camera? Hollywood movies, he says, have developed a rapid-turnover tradition that favors conciseness and novelty in the flow of images.

When Van Dyke in 1934 [in The Thin Man] wished to show a familiar event in the life of any man who walks a dog—an event which, although familiar, might not be passed by the censors—he merely showed the leash tightening and the hand of the man being jerked back; then the man stood still and a little later the same operation was repeated. . . . The part not only takes the place of the whole, but is more effective because the imagination of the spectator supplies what is missing.

Seldes might have added that once we’ve supplied that missing piece, we laugh at Asta’s ability to puncture Nick Charles’ serious disquisition on murder.

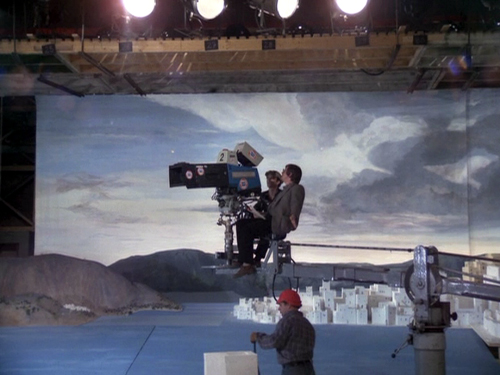

Seldes became a tamer thinker later in life. By the 1950s he was part of the media establishment, producing television shows on culture. He grew disappointed with the film industry, leading to his critiques in The Great Audience. Still, his critical skills persisted. His next major book, The Public Arts (1956), pins his hopes on television but also offers a balanced account of Hollywood’s widescreen revolution. Confronted with CinemaScope and its kindred systems, he worried, again, about pacing.

Wherever the movie touches time, it as mysterious and primordial as the beating of the heart. Absorbed in new techniques, directors may neglect essentials as they did a generation ago when they immobilized the camera to favor the microphone; but, as they recovered mobility then, so I am confident that they will recover the art of using and manipulating time in the substructure of their pictures.

Although he’s seldom discussed in film circles now, Seldes stands out as a worthy critic not because of one-off reviews but in virtue of his pointed, sometimes daring ideas, his knowledge, and the zest they arouse in the reader. These are the payoffs, I think, when a critic leaves reviewing, even the 10-best lists and other fun parts, behind.

My quotations from Seldes come from The Great Audience (New York: Viking Press, 1950), 12; The 7 Lively Arts (Mineoloa, NY: Dover, 2001), 204, 309, and 5; Movies for the Millions (London: Batsford, 1937), 75; The Public Arts (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 55-56. For more on Seldes and his milieu, see Michael Kammen’s excellent intellectual biography, The Lively Arts: Gilbert Seldes and the Transformation of Cultural Criticism in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

My quotation from “The Literary Worker’s Polonius,” comes from Edmund Wilson, Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s and 1930s (New York: Library of America, 2007), 490.

Although the terminology is different, Eliot seems to be advancing something similar to Kristin’s arguments about film analysis in the first chapter of Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

The Thin Man (1934). Seldes forgot that it was Nora, not Nick, who senses Asta’s response to the call of nature.

The Cross

The Puffy Chair (2005).

Mark: [The actors] need to improvise. They need to find the moments, and we don’t let them lean on the script too much. We want them to try to reinvent some of the dialogue and make it fresh.

Jay: We don’t do any blocking. Our whole goal is just to set up a room and basically foster an interaction that we feel is interesting and real.

Mark: And spontaneous.

Jay: And spontaneous.

Jay and Mark Duplass, talking of their new film Cyrus.

DB here:

We don’t do any blocking. Dude, we noticed. In The Puffy Chair, the Duplass brothers typically settle the actors into one spot and pan or cut between them.

Seldom do the characters move around the setting. When they do, it’s usually by means of a walk-and-talk traveling shot that transitions to the next static layout of actors.

We are talking about filmmakers who refuse the challenge of staging.

At the other extreme of budget and commercial clout, consider another film by two brothers. In The Matrix Reloaded, Neo meets the Oracle in the virtual courtyard and sits on a bench with her.

The whole scene, which runs nearly seven minutes, contains 94 remarkably static shots. After Neo settles on the bench beside her, we get simple reverse shots—lots of them, mostly one per line of dialogue. The setups are maniacally repeated. There are thirty-one iterations of the first framing below and eighteen of the second.

The only variation is a slightly tighter framing on each character, creating another brace of single setups during Neo’s acknowledgement of his dream of Trinity’s death. Each of these gets nine iterations.

Sustained two-shots would have let the actors do more with their upper bodies, but in this string of singles, faces and dialogue have to present Neo’s reactions to his new mission to save Zion. Granted, there are seven shots showing both Neo and the Oracle in the same frame, but these are very brief and seem to be there simply to provide beats and add some variety to the load of exposition the scene must carry.

Breaking the scene up so much has interesting rhythmic implications. Paradoxically, our movies are cut very fast but they feel rather slow (and run very long). When we need a cut to see a character’s reaction, a scene plays out more slowly than if the characters were held in the same frame for a significant period. Then we might see Neo’s reactions while the Oracle is speaking, rather than having to wait for them afterward.

But my main point is that the actors are planted in one spot. Like the Duplasses, the Wachowski brothers have felt no need to imagine the characters’ interaction through blocking. Indeed, when shooting a conversation, most of today’s filmmakers seem happiest if the actors stay riveted in place—standing, seated, riding in a car, typing at a computer terminal. Improvised cinema or storyboard cinema: Both camps are refusing the challenge of staging.

In some books and some web entries (most recently, here and here and here and here), I’ve tried to trace the rich tradition of ensemble staging. From almost the start of cinema, filmmakers have explored creative ways of moving actors around the set, aiming at both engaging storytelling and pictorial impact. Since the 1960s, on the whole, this tradition has been waning. Now, I fear, it has nearly disappeared.

I’m not going to reiterate those earlier arguments. Instead I want to talk about one simple staging tactic that directors almost never employ today. I offer it at no cost to young directors. Try it! You might get a taste for a range of cinematic expression that is nowadays neglected.

Cross and double cross

Assume you have two characters in a set. At a crucial moment, you invent some business that lets them exchange places, so that the one on the left winds up on the right, and vice-versa. At a minimum, this gives you visual variety; it keeps the viewer’s attention engaged by refreshing the composition. It can of course also heighten dramatic impact.

Naturally, we expect to find the Cross in the first golden age of cinematic staging, the 1910s. Here’s a case that combines the cross with depth staging, from the Doug Fairbanks picture The Matrimaniac (1916).

Marna and the Court officer have switched places in the frame. Note especially that her movement to the right, clearing our view of the officer at the door, is motivated by her hesitation at following him. Actually such moments probably don’t need much motivation; the flow of the action is so quick that no viewer will ask why she moved to the right, since our attention is on what her action reveals.

One way to motivate the Cross is to have A turn sharply away from B but keep talking. This is a bit of actor’s business that seems far more common in the classical era of moviemaking. Here is an excerpt from a single-shot scene in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). Brennan tries to console Mrs. Mrs. Mims, who has realized that her husband betrayed her. He enters the shack and then walks past her, as if considering exactly how to calm her.

This has been the prelude to a more intense confrontation. She comes closer to the camera, and Brennan joins her, forcing her to look at him as he says they must concentrate on staying alive.

In Demy’s Lola (1961) the Cross is motivated by the urge to offer another emphatic view of the protagonist. Roland has been talking to the two mother-figures who run the café he frequents. He’s dragging himself off to work as Jeanne fetches her radio from the bar and goes into the back room. We get two Crosses.

The shot’s climax comes when Roland pauses in the foreground and says: “One day I’ll go away too.” Again, a key character is turned from the other but continues to speak.

No need to cut in to a close-up because Roland’s face is perfectly visible. Just as important, while his face shows a certain reverie, his nervousness is conveyed by the way he waggles the novel in his hand. The actor is given a chance to act, not just with line reading and facial expression but with his slumped posture and his arms—one casual, the other in anxious motion. Taken together, the body and the face present Roland’s confusion.

Crossfire

Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949) yields many offhand instances of the Cross, indicating how taken for granted the technique was in studio films. When the slippery Fiske invites Joan in, she comes to the left foreground and he moves to the right side of the frame to shut the door.

Approaching her by stepping into medium shot, he tries to warm her up, but she slaps him. Cut in to underscore her reaction. “What did you expect—kisses?”

In a return to the earlier setup, she turns away and executes another Cross, settling on the sofa.

Simple and concise; some would say banal. But compared to The Puffy Chair and The Matrix Reloaded, it looks brisk. The characters move easily through the frame without camera arabesques, and the medium shot is saved for the slap. The single of Joan adds another spike to the drama. Close-ups no longer rule but are used for momentary emphasis.

So the Cross can be sustained by cutting and camera movement. In The Lady Is Willing, Liza has found a baby and called a pediatrician. Director Mitchell Leisen gives us an over-the-shoulder shot of her and at the close of it she walks around Dr. McBain’s arm, with her feathery hat brushing his face.

If the shot were sustained with a pan, we’d have a Cross, but instead there’s a cut to Liza continuing the movement. McBain turns to watch her.

He starts to follow her diagonally. When she pauses to face him, the Cross is completed.

They leave the room. After a cutaway shot showing Liza’s secretary, the camera pans to follow McBain into depth washing his hands. When he comes through the door past Liza, we get another Cross.

With positions switched, the camera travels with her as she catches up with him in a medium shot. He is opening his medical bag.

This pause enables Leisen to underscore a key line of dialogue. “I detest children of all ages. I detest infants particularly.”

One more Cross and the shot is done. The camera pans again to follow McBain bending over the child, and Liza slips into the shot behind him, remonstrating with him. “A man who dislikes children simply can’t be a baby specialist.”

As so often, the Cross is used to present one character turning from another, or one trying to catch up with another who for dramatic reasons plows ahead. And the Cross favors a moderate depth, not the eye-smiting foregrounds of Welles but something less aggressive. In these ways, the simple device can participate in a broader pattern of fluid craftsmanship. The action can unfold in a clean rhythm, consistent with what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis.” Story points arise smoothly out of the flow of behavior. Actors get a chance to use their whole bodies, to create character through posture or stance, or even the angle of the elbows. Imagine if Dietrich, in the left shot just above, had sauntered to McBain with her hand on her hip as she does in so many other movies; the scene would take on a different tint.

When thinking about staging, we usually invoke Renoir or Ophuls or Jancsó, directors who integrate complex choreography with complicated tracking shots. (They also use the Cross a lot.) My examples try to show that even simple camerawork can enhance the performers’ grace. Nor do they have to execute the calisthenics on display in the office scenes of His Girl Friday. The modest moves we see in The Big Steal and The Lady Is Willing are within the grasp of eager filmmakers and game actors.

Cross purposes

I don’t have a good explanation for why such simple staging tactics have gone out of fashion. It’s too easy to cite laziness or lack of imagination, though they may play a role. I wonder as well if complicated staging is much taught in film schools. More specifically, improvisational methods may actually inhibit creative blocking. An actor who’s winging it may be reluctant to shift around the set, for fear that this creates new problems for framing or lighting or the other performances. Better, the actor may think, to concentrate on line readings, expressions, and other things that she can control while staying rooted to the spot. And maybe our directors don’t want to work their actors too hard, especially when the actors are beginners or nonprofessionals, as we find in indie filmmaking. Yet some masters of supple, intricate staging, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, employ untrained performers.

Contemporary directors may have a more principled objection to the older staging style: It’s too artificial. In real life, people mostly chat with each other when they’re sitting down, or walking, or riding in a car. Static staging, some might say, captures the passive nature of everyday interactions.

But dramatic narrative typically doesn’t consist of ordinary life. A film offers heightened, focused, pointed encounters, shot through with meaning and feeling. The actors and the filmmaker have a chance to sharpen the viewer’s perception of the situation and pass along the moment-by-moment play of thought, emotion, and action. There are both loud and quiet ways of doing this. Antonioni’s famously “dedramatized” scenes are staged as dynamically as the more florid moments of Visconti or Fellini. Emotionally subdued action can be shaped just as precisely as passionate outbursts, and it can carry its own impact.

I should make it clear that I’m not asking anybody to embrace a single style. Sometimes stand-and-deliver and intensified continuity editing work very well. Directors will always seek specific solutions to the problems of a scene. But I don’t see much variety in the solutions many people now pursue. I don’t see evidence that most young filmmakers around the world are aware that traditions furnish lots of alternatives.

In earlier periods, some directors were as editing-oriented as today’s mainstream ones, while other directors adopted more staging-driven approaches. But either sort had a broader palette than what we see today. Any accomplished director could stage a conversation in a variety of ways. Just to take Demy, some scenes in Lola are handled in full shots like the one highlighting Roland in the café. Other scenes are broken up into tight singles, and still others are treated in two-shots.

All the classical films I’ve mentioned are pluralistic in their technical choices. Today, though, we see more uniformity, or rather conformity.

Cinephile conversation on the internet is currently rippling around a controversy about “slow cinema.” Whatever that rough category covers, it surely includes those festival films that put the camera in one spot per scene and simply observe. I’d argue that many of these minimalist movies are also AWOL when it comes to staging. After watching a long-take, flatly shot film with me, a Hong Kong filmmaker friend remarked, “This sort of thing is just too easy.” One difference between a solid “slow film” and an empty one, I suspect, lies in the extent to which the filmmakers explore the resources of staging. How do we know? We have to analyze the films. (More on this matter here.) Absent that analysis, critics’ appeals to realism or meditative restfulness or “time flowing through the shot” risk becoming alibis for inert moviemaking.

Many young directors want to be innovative. They want to shake things up. This is a good impulse. The way things are going, the ambitious way forward is obvious: Go backward. Avoid stand-and-deliver. Avoid walk-and-talk. Get your actors on their feet and move them around the setting. Invent bits of business that let them crisscross the frame, laterally and in depth. Dynamize all areas of the shot. In the process you may discover new dimensions of creativity.

The Cross is only one tactic, but I think it’s useful as a way to sensitize ourselves to staging. The best way to understand staging is to watch, really watch, a lot of classic cinema from Hollywood and elsewhere. When you’re ready for the hard stuff, Mizoguchi is waiting.

I expect disagreements with my criticisms of contemporary film technique, so I hope skeptics will consider my more extensive arguments in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I haven’t found references to what I call the Cross in manuals of direction. The closest technique, and the one that called my attention to the possibilities of the technique, is what Mike Crisp in his valuable book The Practical Director (first ed., 1993) calls the “rise and cross.” This refers to actors getting up from sit-down conversations in one spot and moving to another sit-down area, while switching position in the frame. I’ve expanded the idea to cover a broader variety of situations.

As far as I can tell, my term doesn’t have much in common with the stage direction “Cross,” which you’ll find in play scripts. Janie Jones provides definitions here. While staging in film is in many respects different from that in theatre, I think that moviemakers can find intriguing practical ideas in Terry John Converse, Directing for the Stage.

Alicia Van Couvering’s interview with the Duplass brothers, “Don’t you want me?”, is published in Filmmaker 18, 3 (Spring 2010; not yet available online); my quotation is from p. 43. In his essay Slow Cinema Backlash, Vadim Rizov argues that lesser attempts at “slow cinema” have led to a somewhat predictable style.

Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979).

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.

The winnowing process for art-house fare happens on an international level as well. A prestige festival like Cannes dictates that a film they show cannot have had a festival screening or theatrical release outside its country of origin. Programmers for other festivals come to Cannes and cherry-pick the films they like for their own festivals. Toronto has come to serve a similar purpose, especially for North American festivals. Some films fall by the wayside, but the good ones attract a lot of programmers. These films show up at just about every festival. By the way, that kind of saturation booking of the year’s art-cinema favorites at many festivals means that the distributors are more and more often supplying digital copies of films to the second-tier events. Going to festivals is no longer a guarantee that you’ll be seeing a 35mm print projected in optimal conditions. At the 2009 Vancouver festival, I watched Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains twice, because it was a good 35mm print and I suspected that I’d never have another chance to see it that way.

To each film its proper venue

There’s no way that every deserving film will reach everyone who might admire it. Condemning the crowds who frequent the blockbusters won’t help open new screens to offbeat fare. If someone loves Avatar, as long as they keep their cell phones off, refrain from talking, and don’t rustle their candy-wrappers too loudly, as far I’m concerned they can go on believing that this is the best the cinema has to offer. Simply showing these audiences a film like A Serious Man, say, or Precious isn’t going to change their minds about what sort of cinema they prefer. To break through decades of viewing habits, such people would need to learn new ones, which takes time and effort. People’s tastes can be educated, but the odds are usually against it actually happening.

Finally, in defending art cinema against mainstream multiplex fare, commentators often cite Avatar or Transformers or the latest example of Hollywood’s venality and audience’s herd-like movie-going patterns. Yet every year major studio films come out that get four stars or thumbs up or green tomatoes. Last year, we had Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Up, Inglourious Basterds, Coraline, and a few others that were well worth the price of a ticket. All of them did fairly well at the box-office while playing in multiplexes. Some readers might substitute other titles for the ones I’ve mentioned, but to deny that Hollywood is bringing us anything worth watching seems blinkered. As I said in 1999 at the end of Storytelling in the New Hollywood, where I criticized some aspects of recent filmmaking practices, “In recent years, more than ever, we need good cinema wherever we find it, and Hollywood continues to be one of its main sources.”

Ultimately my point is that in this stage in cinema history, international filmmaking has settled into a defined group of levels or modes. Hollywood gives us multiplex blockbusters and more modest genre items like horror films and comedies. They bring us the animated features that are among the gems of any year’s releases. Then there are the independent films and the foreign-language ones which together form festival/art-house fare. There are also the experimental films, which play in festivals and museums. The institutions that show all these sorts of films have similarly gelled into specialized kinds of venues suited to each type. A broad range of films is still being made. There are some few really good films in each category made each year. The question is not how many worthy films are getting made but how much trouble it takes to see them.

None of the current types of institutions is likely to change on its own. What will make a difference is the growing possibilities of distribution via the internet. Filmmakers who get turned down by film festivals can produce, promote, and sell their movies via DVD or downloads. True, recouping expenses that way is so far a dubious proposition; it’s probably easier to get into Sundance than to do that. As I mentioned, digital projection may make some festivals less attractive to die-hard film-on-film cinephiles. On the other hand, in some towns opera-lovers who can’t get to the big city now can see a digital broadcast of a major production each week at their local multiplex. Not as exciting as a trip to the city to see it live, but a lot cheaper and hence within the reach of a lot more people’s means. All sorts of other digital developments will change movie viewing in ways we can’t yet imagine.

_______________

Jim Emerson has been covering the Film socialisme battle of the reviews on Scanners, with quotes and links to the ones I mentioned and more. He also demonstrates that people have been baffled by Godard since Breathless, with reviews that “are, incredibly, the same ones he’s been getting his entire career — based in part on assumptions that Godard means to communicate something but is either too damned perverse or inept to do so. Instead, the guy keeps making making these crazy, confounded, chopped-up, mixed-up, indecipherable movies! Possibly just to torture us.” He offers as evidence quotes from New York Times reviews over the decades.

Eric Kohn gauges the controversy and offers a tentative defense of the film on indieWIRE.

For our reports on various festivals, see the categories on the right. We discuss Godard’s compositions, late and early, here and his cutting here.

From books to blogs to books

Kristin here:

This is a follow-up to David’s latest entry on the supposed death of film criticism.

![]() As academics rather than reviewers, we’ve tried to take advantage of the benefits offered by the Internet. In our pre-blogging days, David used his website to post articles. They came out faster than they would if submitted to a print journal, and they would reach a larger audience, at least in the short run. When we added a blog to the site, it became, as David wrote, “our own magazine.”

As academics rather than reviewers, we’ve tried to take advantage of the benefits offered by the Internet. In our pre-blogging days, David used his website to post articles. They came out faster than they would if submitted to a print journal, and they would reach a larger audience, at least in the short run. When we added a blog to the site, it became, as David wrote, “our own magazine.”

For a while putting a lot of entries no place but on the blog seemed fine. Our stat-counter tells us that a lot of the older entries get read. Either a teacher assigns them or someone finds an old link or discovers the blog for the first time through a new entry and then clicks around on a lot of the older pages. So it’s not as though the pieces disappear a few weeks or so after they’re written. The blog has become a large resource by now.

But what about the really long run? I tend to want to see my prose in print. It’s unlikely that the blog will completely crash, but what if it did happen? And what becomes of all the material on the blog in the distant (I hope) future when we’re not around to keep an eye on it?

Ironically, the internet has proved to be a good way of extending the life of our print books. David’s Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema went out of print, and now it’s online, improved with better pictures, many in color. My Exporting Entertainment was in print for such a short time that few knew I had written it; now it has found a home on the website. Now Planet Hong Kong is out of print as well. David plans to update it and post the new version on the website as well.

Ironically, just as we were contemplating the migration of our books from print to pixels, Rodney Powell, of the University of Chicago Press, inquired as to whether we would be interested in turning a selection of our blog entries into a book. It wouldn’t be necessary to take down the original entries, he assured us. We couldn’t have done that anyway, since our textbook Film Art has just added a feature that alerts teachers and students to relevant essays via URLs in the margins. But we agreed to such a collection, and we’ve just sent in the manuscript for copy-editing. The result, called Minding Movies, should be out next spring.

There hasn’t exactly been a stampede to collect blog entries as books, but some presses, including Chicago, are trying out this new genre. Profile Books has just published classicist Mary Beard’s It’s a Don’s Life, based on her blog of the same name. (I highly recommend her book, The Fires of Vesuvius.) Economists Gary S. Becker and Richard A. Posner’s Uncommon Sense (also the University of Chicago Press) culls items from The Becker-Posner Blog.

Apart from blog-based books, the University of Chicago Press has some more traditional books of film criticism in press. One is a collection of Dave Kehr’s reviews from his days with the Chicago Reader (1974-1986). In September it will also publish a book gathering writings by Jonathan Rosenbaum (some of which have also been posted on his website) called Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition. Chicago has announced a third volume of Roger Ebert’s Great Movies for October of this year. Although some of these pieces have been posted on the authors’ websites after their initial print publication, Minding Movies is unusual in that its entire contents, like those of the Becker-Posner book, were written designedly for the Internet.

Will people want books of blog material that’s available for free online? From our standpoint it seems odd. True, some people just don’t like reading anything longer than a few paragraphs on a computer screen. But choosing the entries to put into the book made us realize how big the blog has become over three and a half years. It’s not easy to just browse through.

This entry marks post number 320 on Observations on Film Art. We were able to include 31 of that total in the book, which will be around 96,000 words. The inescapable conclusion is that we have posted ten volumes’ worth of stuff on the blog. Whew!

Not that we would want to put everything on Observations on Film Art into print. There are a lot of relatively topical items like festival coverage and reports on lectures and conferences and DVD supplements. My piece on the “I Drink Your Milkshake” phenomenon brought us our single busiest day ever (over 20,000 page loads), but it dealt with a fad and certainly doesn’t deserve to go between the covers of a book. Still, quite a few of the entries do reflect research and analysis of the sort that we would ordinarily put into our articles.

Even before it ever occurred to us that we could put together a blog collection, colleagues had said, “Your stuff deserves to be published as a book.” Maybe that’s a sign of the lingering sense that print publication is still more serious than blogging. Another implication seems to be that, while pieces written to be posted online may be excellent and worthy of publication in any format, they also need to be rescued from the vastness that is the Internet. Yes, Google can help people find David’s entry on staging in There Will Be Blood in a flash. But if the reader doesn’t have any particular film or other specific topic in mind and just wants to see our best pieces, it’s not that easy.

Incidentally, “Hands (and faces) across the Table,” the There Will Be Blood piece, won’t be in the book. It contains too many pictures, which becomes more of a concern in print. There will be a few of the heavily illustrated entries in the book, but we had to balance those with others that don’t depend on images.

Whether books based on film and other media-related blogs will become a lasting genre has yet to be seen. Perhaps after a period of adjustment to the Internet as a venue for film criticism, we will return to the practice of the 1960s and 1970s, when Andrew Sarris, Pauline Kael, and other critics routinely saw their material collected as books. We might end up concluding that the Internet has not harmed books in the way that it has some newspapers and magazines.

If blog-based books do catch on, they will provide further counter-evidence to the notion that film criticism is dying out. If they don’t, the failure won’t prove that film criticism is dead, only that now it probably flourishes best online.

[March 22: Coincidentally, TV historian and critic Jason Mittell posted a related entry on his blog today. It’s entitled “Why a Book?” and ponders the pros and cons of publishing a scholarly book or putting the same material online. The piece doesn’t deal with the idea of a book collecting blog entries, but it touches on factors like long-range availability.]