Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Film criticism: Always declining, never quite falling

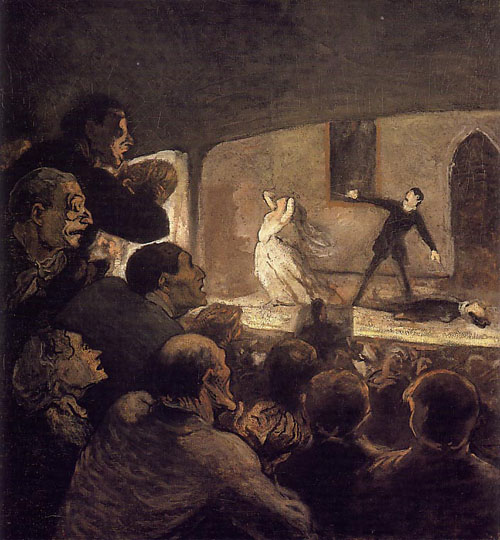

Daumier, Le mélodrame (1860-64)

DB here:

Before the Internets, did people fret as much about movie criticism as they do now? The dialogue has become as predictable as a minuet at Versailles.

Film criticism is dead.

No, it’s not! It’s alive and well on the Web.

Hah! Call that criticism? Nobody can be a movie critic unless they (a) write for print publication; (b) have been doing it for x years; (c) are a member of a critics’ professional society; and/ or (d) get paid for it.

Well, the track record of the official movie critics isn’t that great. Most of their writings are forgotten the minute they’re published.

Infinitely more awful is what you read on the Net. At least print critics kept up standards; there were gatekeepers (also called editors) and a literate public.

The result being….? When has a print critic of recent years equaled the greats of the past—Agee, Farber, Sarris, Kael?

Same thing goes for the Net. Blogs and websites don’t show me anything like that level of achievement. What I see is amateur hour.

Yeah? Well, bloggers and netwriters have passion!

But not a passion for using Spellcheck.

So if print criticism is so valuable, how come all those professional critics are getting fired?

Film criticism is dead.

Repeat as often as you like.

I thought I had watched this rondelay often enough from the wallflower section, but I got dragged onto the dance floor by Tom Doherty. In his piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education, Tom offered another eulogy for serious film criticism. Dead again, as Jim Emerson notes; killed by those wretched netizens.

To watch their backs and retain their 401(k)’s, most print critics have been forced into sleeping with the enemy. As a form of ancillary outreach, blogs, podcasts, and chat-room discussions have become a required part of the job description for print reviewers. Or maybe the print part of the gig is now the ancillary outreach.

Feeling the same heat, academic critics have also plunged into the brash new world. The film-studies panjandrum David Bordwell—think Knowles with chops in postmodern theory—runs one of the most closely watched blogs at David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema (http://davidbordwell.net/blog). The impact of the academic bloggers on Hollywood’s box-office gross is negligible (sorry, David), but the online work of the digital hordes is already making a substantial contribution to film scholarship—in the spirited parry and thrust of the dialogues, in the instant retrieval of past research, and in the factoid jackpots provided by the film databases.

I’m sure Tom means to be complimentary, but just to get mundane: No heat forced Kristin and me to the Web. I set up a bare-bones site in 2000, including a vitae and a statement about what studying film meant to me, because people were sometimes writing me asking for such information. Then, inspired by Philip Steadman’s stylish site extending the arguments in his book Vermeer’s Camera, I used mine to supplement my books, putting in corrections, second thoughts, and pictures. Then I began to write longish essays that build on things in the books.

When I retired in 2006, Kristin and I decided to recast the site as a supplement to our best-known book, Film Art: An Introduction. Our publisher McGraw-Hill funded an upgrade. But our efforts quickly went beyond spinning off the textbook. We treated Observations as our own magazine, with no pesky editors to tell us that a piece was too long or had too many stills. It offered a way to get our ideas out to a new audience, or maybe a bigger one. Just as important, after years spent writing books, I enjoy the recreation of writing shorter pieces. When you’re 62, sprints look better than marathons. Actually, because I’m a compulsive overwriter, some of my blog-sprints are like marathons.

Unhappily, none of this enhanced our 401(k)s.

Some other quibbles: Tom intended “panjandrum” as praise, but as many friends have pointed out, I’m probably the last person you’d associate with PoMo. I’m stuck in pre-post-modernism. Still, Tom is right on one point. My efforts to erode the box-office takings of Babel, The Departed, and The Dark Knight failed utterly. On the other hand, I may have considerably boosted Cloverfield’s first-dollar gross.

Nothing if not critical

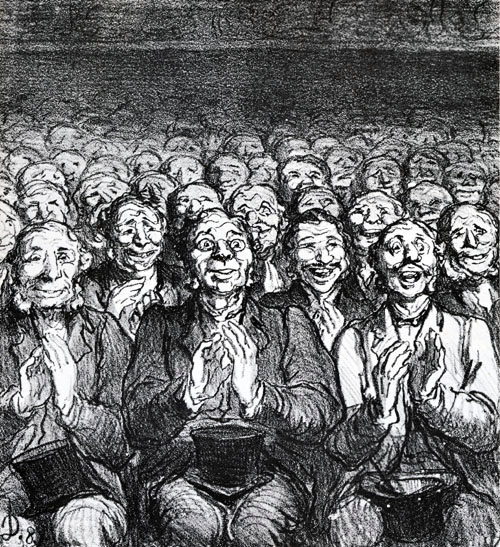

Daumier, Les critiques (1862)

Tom’s piece, its place of publication, the comments on it, and his reply to those comments invite me to revive some points I made around this season in 2008 and 2009. (Is it a rite of spring?)

Film criticism takes many forms. Tom identifies criticism with being paid to review movies that have just come out. This is a form of arts journalism, and like all journalism it is being squeezed by the decline in advertising revenue. So yes, print-based paid reviewing is waning.

But criticism includes more activities than rapid-response reviewing. It includes what we might call haute journalism, as practiced in literary quarterlies, film magazines like Cineaste and Cinema Scope, and even occasionally in the New York Review of Books (which just got around to noticing Sokurov’s 2005 The Sun). There’s also reseach-based criticism, published in specialized venues like Cinema Journal and in semi-specialized journals like Film Quarterly (which seems to be moving toward haute journalism). And of course academics have written whole volumes of film criticism—through-composed books, not collections of published reviews.

Each of these modes of criticism has its own conventions. I try to characterize them here. I think Tom should have made some of these distinctions, because it doesn’t help film culture to encourage readers of the Chronicle to limit their conception of criticism to what they get in The New Yorker or Salon.

Insofar as we think of criticism as evaluation, we need to distinguish between taste (preferences, educated or not) and criteria for excellence. I may like a film a lot, but that doesn’t make it good. For arguments, go here again. Criteria are intersubjective standards that we can discuss; taste is what you feel in your bones. A critical piece that merits serious thinking tends to appeal to criteria that readers can recognize, and dispute if they choose.

Enough with the love, already. My only real quarrel with Gerry Peary’s film For the Love of Movies is that it seems to place “love of cinema” at the center of the critical activity. But everybody loves film. The real question is: What does this love lead to? Gossip? Infighting and insults? A desire to take chances and watch films you might hate? A desire to stretch and nuance one’s viewing? An urge to learn something subtle about cinema more generally?

Opinions need balancing with information and ideas. The best critics wear their knowledge lightly, but it’s there. To be able to compare films delicately, to trace their historical antecedents, to explain the creative craft of cinema to non-specialists: the critical essay is an ideal vehicle for such information. The critic is, in this respect, a teacher.

Which means that the critic traffics in ideas too. A critic of lasting value offers a vision of cinema, of the arts more generally, of society or politics or something beyond the individual movie. For Sarris, the key idea was directorial authorship. For Parker Tyler, it was the idea that popular culture spasmodically threw up surrealistic material. For Farber it was the prospect that the studio system nurtured films, or moments, that hinted at speed, harshness, and darkness. Sontag clung to the hope that cinema could carry on the program of post-World-War-II modernism. For Ebert, what seems central is the belief that cinema can yield humane wisdom that forms a guide for living. Beyond our shores there were Arnheim, Bazin, Eisenstein (yes, he wrote film criticism), the Cahiers and Positif crews, and many more. Their powerful and provocative ideas yielded new ways to think about any movie.

Last year I moderated an Ebertfest panel consisting of a dozen or so critics. A student from the audience said he wanted to be a critic too. Instead of advising him to get into a more financially rewarding form of endeavor, like selling consumer electronics off the back of a truck, the panelists encouraged him. This form of altruism, in which you help people to become your competitor, is alarmingly common in the arts.

A moderator doesn’t get to talk much, so I couldn’t respond. What I wanted to say was: Forget about becoming a film critic. Become an intellectual, a person to whom ideas matter. Read in history, science, politics, and the arts generally. Develop your own ideas, and see what sparks they strike in relation to films.

Writing style is overrated. Many people think that good reviewing amounts to personal opinions whipped up in frothy prose. Perhaps the snazzy styles of Farber and Kael have led people to weight style too much. Granted, the Web has revealed that a lot of people are excellent writers, and without the Web they would probably never have found an audience. Although lively writing is always welcome, it gets heft and endurance through its arguments, and that comes back to ideas and information as much as opinion.

Hollywood, still declining

As often happens, a current controversy sends me backward, and to books. Ezra Goodman’s Fifty-Year Decline and Fall of Hollywood was published in the momentous year 1960, as was Beth Day’s This Was Hollywood. Both wrote finis to the glory days of American studio cinema. But if Day was nostalgic, Goodman was sour, and racy.

He worked as reporter, publicist, and reviewer, most notably for Time. By 1960, he must have felt he never needed an LA job again, so he castigates every specimen of Hollywoodite, from press agents to stars. Buddy Adler, who for a while ran production at Twentieth Century-Fox was no more than “a dutiful office boy.” Humphrey Bogart had “as a result of four marriages, innumerable bouts with the bottle, and a paucity of food and sleep developed what was described as a look of intelligent depravity. . . .”

Goodman includes a long chapter on film reviewers, which launches with a decidedly contemporary ring:

It has been said that there are sometimes more clichés in movie reviews than in the movies they are discussing. Sample review phrases: “sure-fire,” “stunning,” “taut with suspense,” “lavish and exciting,” “sumptuous,” “captures the imagination,” “moving,” “significant drama,” “sheer screen artistry,” “uncommonly good performance,” “dramatic urgency,” “enormous compulsion,” “spectacular finish,” and once in a while, “ineptly directed,” “singularly dull.”

Fifty years later, Goodman would have to add jaw-dropping, adrenalin-charged, mind-bending, hellish/ hellacious, resonance/ resonate, lush, dark, incredible, intensely personal, pitch-perfect, and our two all-purpose adjectives of praise, amazing and terrific. You’d think that we were staggering around astounded all the time.

Yet reading Fifty-Year Decline and Fall confirms my hunch that we have made progress. I would say that the best film writing in all registers–daily/ weekly reviewing, haute journalism, “think pieces,” personal essays, research studies, whether on the web or off– is much better today than it was in Goodman’s era. Then the New York Times had Bosley Crowther; now it has Dargis and Scott. Richard Schickel has hurt his reputation with some insulting remarks he made recently, but read his book on Fairbanks, His Picture in the Papers, or his scathing The Disney Version, and you’ll find a keen eye and a nonconformist intelligence. Riding above the oceanic fizz of infotainment, there are many sharp writers both journalistic and academic. Start clicking our link-list for examples.

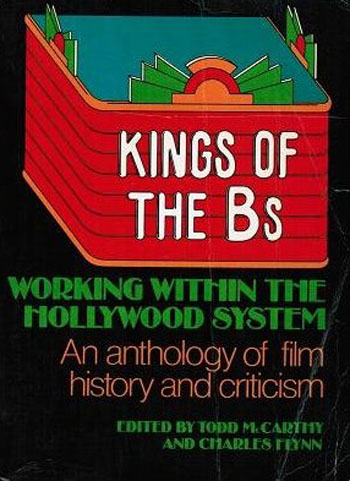

Which makes it all the more lamentable that two of our finest writers have lost their platform. Todd McCarthy’s work for Variety long exemplified the virtues I’ve itemized. He writes a brisk prose that isn’t showoffish. His reviews, often in a few deft words, situate the film historically; he’s one of those guys who has simply seen and read everything. He has as well a guiding idea of cinema—roughly, I think, the premise that straightforward classical storytelling is an inexhaustible resource—but he doesn’t deploy it as a bludgeon. McCarthy’s respect for studio history and the tradition of expressive narrative can be found in his and Charles Flynn’s indispensible collection Kings of the Bs (where you can see what a Republic budget sheet looked like) and in his biography of Howard Hawks. There are also his documentaries on filmmaking (e.g., Visions of Light) and film culture (Man of Cinema: Pierre Rissient), which allow him the leisure to probe subjects in depth.

Or consider Derek Elley. He is one of the most knowledgeable writers on Asian cinema, and his reviews skillfully tie a new film to a trend or earlier work by the same director. Few critics have his ability to supply a translation of a Chinese film’s original title, or to explain a crucial local custom. By dismissing McCarthy and Elley as contract writers, Variety has dealt a blow to informative, thoughtful film writing, whether you call it criticism or not.

Daumier, One says that the Parisians. . . (1864)

Propinquities

Jinhee Choi, Centre Pompidou, January 2010.

Propinquity: Nearness, closeness, proximity: a. in space: Neighborhood 1460. b. in blood or relationship: Near or close kinship, late ME. c. in nature, belief, etc.: Similarity, affinity 1586. In time: Near approach, nearness 1646. —Oxford Universal Dictionary

DB here:

In any art, tools and tasks matter. From the first edition of Film Art (1979) to the present, our introduction to film aesthetics starts with an overview of film production. How is production organized within the commercial industry, or within a more artisanal mode? What freedom and constraints are afforded within the institutions of filmmaking? How does current technology support or limit what the filmmaker can do? And how do filmmakers explain what they’re doing—not just as personal proclivities but as rhetorical “framings” that lead us to think of their work in a particular way?

Some would call this approach “formalism,” but that label doesn’t capture it. Traditionally formalism refers to studying an artwork intrinsically, as a self-sufficient object. In this sense, our perspective is anti-formalist: We look outside the movie to the proximate conditions that shape its form, style, subjects, and themes.

More literary-minded film scholars have sometimes been impatient with this perspective. Yet in the history of painting and music, it has yielded real advances in our knowledge. It continues to do so in film studies too, as I learned when we came back from Yurrrp to find some books awaiting us. (Kristin has already remarked on the stacks of DVDs that had accumulated.) Among these were books that illustrate the continuing value of situating film artistry in its most immediate context: the creative circumstances, the norms and preferred practices operating within traditions, the rationales that artists offer for their choices. Even better, the books were written by friends, so we have both intellectual and personal propinquity. I have always wanted to use the word propinquity in a piece of writing.

Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho).

Jinhee Choi’s The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Gobal Provocateurs is a wide-ranging survey of what some have called the “next Hong Kong”–a popular cinema of brash impact and technical polish, on display in JSA, Beat, Dirty Carnival, My Sassy Girl, and the like. But unlike Hong Kong, South Korea has a strong arthouse presence too, typified by Hong Sang-soo’s exercises in parallel narratives and thirtysomething social awkwardness. Between these poles stands what local critics called the “well-made” commercial film, as exemplified by Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder.

Choi, a professor at the University of Kent, mixes analysis of cultural and industrial trends with consideration of crucial genres (notably the “high school film”) and major auteurs. She is the first scholar I know to explain changes in the Korean film industry as emerging from a dynamic among critics, filmmakers, private funding, and government sponsorship. A must, I would say, for anyone interested in current Asian film.

T-Men (Anthony Mann, cinematographer John Alton).

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

Keating scrutinizes the films with unprecedented care, tracing not only cameramen’s distinctive styles but showing that originality was always in tension with the conventional lighting demands of various genres and situtations. Many big names are here—John Seitz, Gregg Toland, John Alton—but the book also examines innovations coming from solid craftsmen like Arthur Lundin, who lit Girl Shy and other Harold Lloyd films. You won’t look at a studio movie the same way after you’ve digested Keating’s richly illustrated analyses.

Both Jinhee and Patrick were students here, and I directed the dissertations that eventually became these books. So of course I’m biased. But I think that any outside observer would agree that these monographs show the value of studying how film artistry and the film industry intertwine.

Blue (Krzysztof Kieslowski).

No less sensitive to the interplay of art and business is Patrick McGilligan’s Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s. The collection is as illuminating as earlier installments have been. How could it not be, with career ruminations from Nora Ephron, John Hughes, David Koepp, Barry Levinson, John Sayles, et al.?

I’ve long found Pat’s Backstory volumes a treasury of information about Hollywood’s craft practices. Every conversation yields ideas about structure, style, and working methods. In this volume, for instance, Richard Lagravanese points out that scenes have become very short; with slower pacing in the studio days, scenes had time to breathe. And after claiming over and over that cinematic narration comes down to patterning story information, I was happy to read Tom Stoppard:

The whole art of movies and in plays is in the control of the flow of information to the audience. . . . how much information, when, how fast it comes. Certain things maybe have to be there three times.

In the studio days this last condition was called the Rule of Three: Say it once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once more for Slow Joe in the Back Row. Some things don’t change.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

The examples run from the silent era (including Lady Windermere’s Fan, a favorite of this site) to Shadowlands, and while music is at the center of concern, speech and effects aren’t neglected. There’s a powerful analysis of the noises during one sequence of The Birds, and the authors pick a vivid example from Kieslowski’s Blue (above), in which Julie is shown listening to a man running through her apartment building; we never see the action that triggers her apprehension.

The authors provide a compact history of sound film technology, including many seldom-discussed topics. For instance, 1950s stereophonic film demanded bigger orchestras and more swelling scores, while separation among channels permitted scoring to be heavier, without muffling dialogue. Throughout, Neumayer and his coauthors balance concerns of form and style with business initiatives, such as the growth of the market for soundtrack albums and CDs (a topic first explored by another Wisconsite, Jeff Smith, in his dissertation book). Once more we can arrive at fine-grained explanations of why films look and sound as they do by examining the craft practices and industrial trends that bring movies into being.

Watching back episodes of the American version of The Office recently, I’ve been struck by the premise it takes over from the UK original. This comedy of humors in Cubicle World is supposedly recorded in its entirety by an unseen film crew. I enjoy the clever way in which the show bends documentary techniques to the benefit of traditional fictional storytelling. The slightly rough handheld framings suggest authenticity, and the to-camera interviews permit maximal exposition by giving backstory or developing character or filling in missing action. The premise that an A and a B camera are capturing the doings at the Dunder Mifflin paper company permits classic shot/ reverse-shot cutting and matches on action.

The camera is uncannily prescient, always catching every gag and reaction shot; even private moments, like employees having sex, are glimpsed by these agile filmmakers. Above all, the camera coverage is more comprehensive than we can usually find in fly-on-the-wall filming. For instance, Dwight is preparing Michael for childbirth by mimicking a pregnant woman and Andy, behind him, tries to compete. Here are four successive shots, each one pretty funny.

Somehow the cameramen manage to supply a smooth cut-in to Andy, and that’s followed by a reaction shot, from a fresh angle, showing Jim watching. The range of viewpoints, implausible in a real filming situations, is often smoothed over by sound that overlaps the cuts, as in both documentary and fictional moviemaking. (See our essay on High School here to see how a genuine documentary uses these techniques.)

Of course I’m not faulting the makers of The Office for not rigidly imitating documentary conditions. Any such blend of fictional and nonfictional techniques will involve judgments about how far to go, as I indicate in an earlier post on Cloverfield. It’s just to acknowledge that TV visuals have their own conventions, and these can be creatively shaped for particular effects. We ought to expect that those conventions would encourage close analysis as easily as film traditions do. Jeremy Butler’s new book Television Style offers the best case I know for the claim that there is a distinct, and valuable, aesthetic of television.

Following his own study Television: Critical Methods and Applications (third edition, 2007) and paying homage to John Caldwell’s pioneering Televisuality, Butler gets down to the details of how various TV genres use sound and image. Butler’s conception of genres is admirably broad, considering dramas, sitcoms, soap operas, and commercials, each with its own range of audiovisual conventions and production practices. His discussion of types of television lighting complements Keating’s analysis; put these together and you have some real advances in our understanding of key differences and overlaps between film and video.

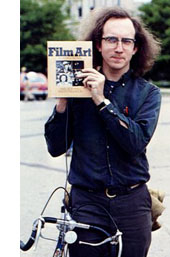

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

None of this is to say that artistic norms or industrial processes are cut off from the wider culture. Rather, as becomes very clear in all of these books, cultural developments are often filtered through just those norms and institutions.

For example, everybody knows that in classical studio cinema, women were usually lit differently from men. But Keating notices that often women’s lighting varies across a movie, depending on story situations. He goes on to make a subtler point: there was a greater range in lighting men’s faces. Men could be lit in more varied ways according to the changing mood of the action, while lighting on women was a compromise between two craft norms: let the lighting suit the story’s mood, and endow women with a glamorous look. The fluctuations in the imagery stem from adjusting cultural stereotypes to the demands of Hollywood’s stylistic conventions.

Careful studies like these, alert to fine-grained qualities in the films and the conditions that create them, can advance our understanding of how movies work. Pursuing these matters takes us beyond both the movie in isolation and generalizations about the broader culture; we’re led to examine the filmmaker’s tasks and tools.

Resurrection of the Little Match Girl (Jang Sun-woo, 2002).

Robin Wood

DB here:

Robin Wood has just died. Kristin and I knew him a little; we recall a convivial dinner with Robin and Richard Lippe in New York during the 1970s. We knew him chiefly on the page, as a writer whom we valued enormously. I take this moment to acknowledge his death, to suggest his importance, and to praise his memory.

Today it’s hard to imagine the impact that Wood had on film criticism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I first encountered his writing while I was in high school. I desperately wanted to know more about movies, but the nearest towns had no libraries. So I wrote to every film magazine I had heard of and said I was considering subscribing. Could they please send me a sample copy? The issues that came through included, most memorably, the Sarris “American Directors” issue of Film Culture and the Howard Hawks issue of Movie. Both changed me forever.

The Hawks issue contained Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo, a sort of draft for what would become one of his most important statements.

Hawks, like Shakespeare, is an artist earning his living in a popular, commercialized medium, producing work for the most diverse audiences in a wide variety of genres. Those who complain that he “compromises” by including “comic relief” and songs in Rio Bravo call to mind the eighteenth century critics who saw Shakespeare’s clowns as mere vulgar irrelevancies stuck in to please the “ignorant” masses. Had they been contemporaries of the first Elizabeth, they would doubtless have preferred Sir Philip Sydney (analogous evaluations are made quarterly in Sight and Sound). Hawks, like Shakespeare, uses his clowns and his songs for fundamentally serious purposes, integrating them in the thematic structure. His acceptance of the underlying conventions gives Rio Bravo, like Shakespeare’s plays, the timeless, universal quality of myth or fable.

Nearly every Wood virtue is already here. He takes it for granted that conventions are crucial to understanding and judging cinema. He refuses an evaluative split between high culture and popular culture. He insists that worthy films have serious thematic implications—in Rio Bravo, a link between self-respect and peer respect. He shows the film’s complexity through shrewd comparison (in the book on Hawks, High Noon will provide the telling contrast). And he gives the whole thing a polemical edge with the sideswipe at Sight and Sound, a target for many years to come.

But it was the books, in an apparently unending flow, that established Wood as a leading voice, and not only for me. I can’t convey the excitement that was ignited by Hitchcock’s Films (1965), Howard Hawks (1968), and Ingmar Bergman (1969), quickly followed by the monographs on Penn (1970) and Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1971). Nearly all books of film criticism were then simply collections of reviews. Wood’s stood as through-written, pondered over, carefully carpentered monographs, comparable to the best literary analysis. These studies showed, in incisive detail, what most auteur criticism simply proclaimed: great directors expressed their personal vision of life in and through cinema. Wood showed, scene by scene and sometimes shot by shot, that movies harbored layers of feeling and implication in their finest grain of detail. Without fanfare he introduced “close reading” to film criticism. Although never academic in the narrow sense, he took cinema as seriously as did critics of art or music or literature.

In fact, the word “serious,” a tonal center of the Rio Bravo essay, might be the keyword of his career. Partly that seriousness is intellectual. From the start Wood’s prose had a rectitude that was argumentative in the best sense. The Hitchcock book begins by imagining the best case one can make against the director; he then demolishes it piece by piece. The author does not try to woo us. He respects his reader enough to spell out his claims and to invite a skeptical reply. At last, we thought: An honest man.

The idea of seriousness took on a deeper import, one shaped by the indelible influence of F. R. Leavis. For Wood as for Leavis, great art inevitably grappled with the ultimate demands of living. Close analysis was nothing unless it revealed the author’s felt engagement with human values. This state of affairs imposed equally stringent obligations on the critic. Nothing could be farther from the snappy badinage and instant turnaround of Netwriting than Wood’s obstinate gravity. Flippancy and showing off had no place in serious criticism. Being a critic, analyzing and interpreting and judging, was a heavy responsibility, and every word had to be weighed. The very status of film as art, indeed the status of art itself, was at stake.

In a passage I cannot find on short notice, Wood once observed that a critic could not write “seriously” about Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai after one viewing. Accordingly, not until he could study the film on DVD did he produce a characteristically penetrating essay. It’s a piece that anyone would be proud to sign, but Wood concludes:

I’m afraid the above analysis, in spelling things out, may have suggested that the film is more schematic than it actually is. Its “scheme” is in fact so subtly worked that it has taken me at least six complete viewings (together with more replays of individual scenes and moments than I can count) to disentangle it from all the detail of the realization. The above account is offered humbly, as a beginning.

This passion for nuance did not lead to a sort of scientific objectivity. The responsibility of criticism made writing inescapably personal. The critic responds to the work as a living being, as a “whole man alive”—a Leavis phrase that Wood was wont to quote. Personal Views, the title of Wood’s first collection of essays, signalled both the artistic visions expressed in the films he studied and the sincerity with which he advocated for or inveighed against a film, a trend, or a system of ideas.

I don’t know any critic whose intellectual and political horizons expanded as much as Wood’s did in the 1970s. Since criticism was for him a form of living, he took his readers along as he discovered structuralist theory (which he had once attacked), accepted some tenets of psychoanalytic theory, and launched ferocious attacks on patriarchy and capitalism. The same moral fervor that informed his 1960s writing became focused upon the political oppression of women, gays, the poor, and free thought. Now, he suggested, the apparent stability of “ordinary” life relied upon psychological and social repression. If one theme runs through his work—that of the precariousness of decent human relations in the face of disorder—it finds its late expression in his belief that conservative politics, in the name of maintaining order, is implacably bent upon destroying our kinship with others. In a sense, CineAction, the journal that he co-founded, was his latter-day Movie, a forum for his new commitment to criticism that promoted progressive social change.

The art he cared most about, I believe, laid bare the struggle between order and disorder. In his first book, he argues that Hitchcock shows comfortable “ordinary” people faced with a world coming to pieces. Across his career Wood ceaselessly questioned what exactly this normal order consists of. Coming out as a gay man, he devoted his finely meshed attention to reading films politically. Now those social forces that he once defined simply as threats to stability, such as the war in Bergman’s Shame, revealed themselves as products of warped political systems. The horror film presents disorder as a monstrous threat to bourgeois norms, yet it can become a powerful force in questioning those conceptions. For nearly four decades Wood recorded his efforts to grasp the concrete social implications behind the films he loved and those, increasingly from Hollywood, he found evasive and duplicitous. In all, complacent acceptance of the status quo was the enemy of the seriousness he prized. When he died he was at work on a study of Michael Haneke.

The seriousness of great artists, he came to believe, was inescapably political. Yet while this made him reevaluate Hawks and Hitchcock, it did not lead him to absolute repudiations. Always a believer in the validity of intuitive response, Wood would trust his sensibility more than the dictates of academic “frameworks” and theoretical systems. A 2004 set of notes on Ozu concludes:

These late Ozu films are detailed and highly intelligent critical studies in cultural change which ultimately defy the application of such terms as “progressive,” “regressive,” “conservative,” etc. . . . “Change” is not necessarily for the better (though our current culture is constantly telling us that of course it is) . . .—an obvious ploy of corporate capitalism, which depends upon the mystification for selling its products. If we gain new freedoms, we should also beware of casually casting off the past without asking ourselves what in it—what standards of seriousness, what beliefs, what aspects of our lives—might be worth preserving. I find all these thoughts in Ozu, incomparably expressed.

Through all the constant reappraisals of films, all the unsparing reconsiderations of his own judgments, one hears the same forthright, urgent voice. Leavis suggested that the good critic always asked, in effect, “This is so, isn’t it?” Wood’s writing consists of firm assertions accompanied by challenges to respond as an equal. The invitation is set out in an impassioned conversational cadence, complete with italics and appositional phrases. In search of clarity, Wood is prepared to argue and dissect forever; who else would produce not one but two books rethinking his defense of Hitchcock? Yet this brisk voice can also move us by its simplicity, as in the sentences concluding that little book on the Apu trilogy.

Suddenly the boy relaxes, and rushes forward into his father’s arms. The film ends with him seated on Apu’s shoulders as Apu walks away towards the future. In accepting the child, he has accepted life, has accepted the death of Aparna. Whether or not he is going back to become a great novelist is immaterial: he is going back to live.

Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo is in Movie no. 5 (undated, 1963?), 25-27. His “Flowers of Shanghai” appears in CineAction no. 56 (September 2001), 11-19. “Notes toward a Reading of Tokyo Twilight (Tokyo boshoku)” is in CineAction no. 63 (April 2004), 57-58.

For a wide-ranging and growing set of links to eulogies for Robin Wood, visit David Hudson at The Auteurs Daily and Catherine Grant at Film Studies for Free. A recent interview framed by enlightening commentary is Armen Svadjian’s 2006 tribute, “A Life in Film Criticism: Robin Wood at 75.” Wood’s 2008 list of the films he most valued is on the Criterion site here. D. K. Holm maintains an invaluable, continually updated bibliography of Wood’s writings here.

François Truffaut, Day for Night (1973).

Kurosawa’s early spring

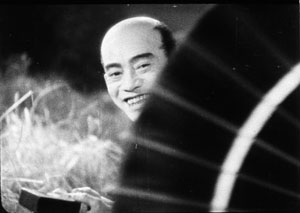

The Most Beautiful (1944).

For Donald Richie

DB here:

Cinephile communities aren’t free of peer pressure. Sometimes you must choose or be thought a waffler. In postwar France, the debate within the Cahiers du cinéma camp often came down to big dualities. Ford or Wyler? German Lang or American Lang? British Hitchcock or American Hitchcock? In the America of the 1960s and 1970s, we had our own forced choices, most notably Chaplin or Keaton?

This maneuver assumed that a simple pair of alternatives could profile your entire range of tastes. If you liked Chaplin, you probably favored sentiment, extroverted performance, and direction that was straightforward (“theatrical,” even crude). If you liked Keaton, you favored athleticism, the subordination of figure to landscape, cool detachment, and geometrically elegant compositions. One director risked bathos, the other coldness. The question wasn’t framed neutrally. My generation prided itself on having “discovered” the enigmatic Keaton, in the process demoting that self-congratulatory Tramp. Keaton never begged for our love.

Of course it was unfair. The forced duality ignored other important figures—Harold Lloyd most notably—and it asked for an unnatural rectitude of taste. Surely, a sensible soul would say, one can admire both, or all. But we weren’t sensible souls. Drawing up lists, defining in-groups and out-groups, expressing disdain for those who could not see: it was all a game cinephiles played, and it put personal taste squarely at the center of film conversation.

In the 1950s another big duality slipped into Paris-influenced film talk. Virtually nobody knew about Ozu, Shimizu, Gosho, Naruse, Shimazu, Yamanaka, et al., so two filmmakers had to stand in for the whole of Japanese cinema. Mizoguchi or Kurosawa?

A problematic auteur

For Cahiers the choice was clear. Mizoguchi was master of subtly shaping drama through the body’s relation to space, thanks to quiet depth compositions and modulations of the long take. In Japan, land of exquisite nuance, the dream of infinitely expressive mise-en-scene seemed to have come true.

There seemed to be nothing nuanced about Kurosawa, whose brash technique, overripe performances, and propulsive stories seemed disconcertingly “Western.” Sold, like Satyajit Ray, as a humanist from an exotic culture, he played into critics’ eternal admiration for significance. This director wanted to make profound statements about the bomb (I Live in Fear), the relativity of truth (Rashomon), the impersonality of modern society (Ikiru), and the complacency of power (High and Low, The Bad Sleep Well). Even his swordplay movies seemed moralizing, with the last line of Seven Samurai (“The victory belongs to these peasants. Not to us.”) summoning up a cheer for the little people. Kurosawa could thus be assigned to Sarris’s category of Strained Seriousness. “He’s the Japanese Huston,” said a friend at the time.

But there was no overlooking his cinematic gusto. He made “movie movies.” He flaunted deep-focus compositions, cunningly choppy editing, sinuous tracking shots (through forests, no less), dappled lighting, and abrupt addresses to the viewer, by a voice-over narrator or even a character in the story. He exploited long lenses and multiple-camera shooting at a period when such techniques were very rare, and he may have been the first director to use slow-motion for action scenes. Bergman, Fellini, and other international festival filmmakers of the 1950s didn’t display such delight in telling a story visually. If you liked this side of his work, you overlooked the weak philosophy. On the other hand, if you found the style too aggressive, it could seem mere calculation on the part of a man with something Important to say.

The case for the defense was made harder by the fact that he was a controversial figure at home as well. Japanese critics I met over the years expressed puzzlement about Western admiration for the director’s style. I was once on a panel in which an esteemed critic blamed Kurosawa for influencing Western directors like Leone and Peckinpah. His violence and showy slow-motion had helped turn modern cinema into a blunt spectacle. No wonder Lucas, Spielberg, Coppola, and Walter Hill have loved this macho filmmaker.

Today passions seem to have cooled, but I should confess that my own tastes remain rooted in my salad days (1960s-1970s). I could live happily on a desert island with only the films of Ozu and Mizoguchi. I’d argue forever that Japanese cinema of the 1920s through the 1960s is rivaled for sheer excellence only by the parallel output of the US and France. (For more on this matter, see my blog entry on Shimizu.) On Kurosawa, however, my feelings are mixed. I still find most of his official classics overbearing, and the last films seem to me flabby exercises. But there are remarkable moments in every movie. Overall, I’ve responded best to his swordplay adventures; Seven Samurai was the first film that showed me the power of the Asian action aesthetic. I think as well that his earliest work up through No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), along with the later High and Low and Red Beard, are extraordinary films. And, like Hitchcock and Welles, he is wonderfully teachable.

We don’t live on desert islands, and gradually we’re gaining easy access to the range of Japanese filmmaking of its great era. We can start to see beyond the fortified battlements set up by generations of critics. With so many points of entry into Japanese cinema, mighty opposites lose their starkness; polarities dissolve into the long tail. Nevertheless, personal tastes take you only so far, and objectively Kurosawa still looms large. Whatever your preferences, it’s important to study his place in film history and film art.

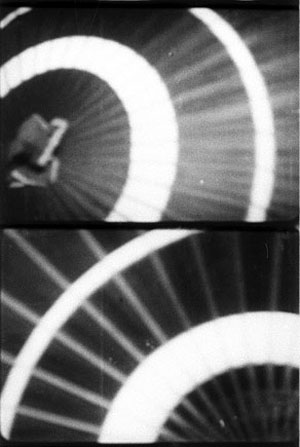

Gauging that place involves thinking outside some traditional conceptions of how films work. Like most ambitious Japanese directors, Kurosawa provides bursts of cinematic swagger. This six-shot passage from Rashomon revels in its own strangeness.

Here traditional over-the-shoulder shots submit to a brazen geometry. Out of an ABC film-school technique Kurosawa creates a cascade of visual rhymes and staccato swiveled glances. Yes, an ingenious critic could thematize this bravura passage. (“The symmetries put the central characters, each of whom asserts a different version of what happened, on the same visual and moral plane.”) Instead I’m inclined to think that the shots constitute a little thrust of “pure cinema,” a brusque cadenza that keeps our eyes, if not our hearts or minds, locked to the screen. From this angle, Kurosawa claims some attention as an inventor of, or at least tinkerer with, the disjunctive possibilities of film form.

His centenary arrives in 2010, and the occasion is celebrated by Criterion with a set of twenty-five DVDs. Most of these titles have already been available singly, and the discs lack all the bonus features we have come to admire from the company. Yet the crimson and jet-black box, the discreet rainbow array of slip cases, and the subtly varied design of the menus add up to a good object, like the latest iPod—something you want even if it means re-buying things you already have. There’s also a handsome picture book with notes by Stephen Prince on each film.

To viewers who need the assurance of cultural importance, this behemoth announces: You must know Kurosawa to be filmically literate. And that’s more or less true. Just as important, the inclusion of four rarities from his early years gives the collection a claim on every film enthusiast’s attention. One hopes that those titles will eventually appear separately, perhaps in an Eclipse edition. [See 15 May 2010 update at the end.] For now these copies of the wartime features are far better than the imports I’ve seen.

The Big Box makes it tempting to mount a career retrospective on this site, but that’s far beyond my capacity. Future blog entries may talk more of this complicated filmmaker, but for now I’ll confine my remarks to these early works. They offer plenty for us to enjoy.

Audacious propaganda

Although Kurosawa was only seven years younger than Ozu, he belongs to a distinctly different generation. Ozu directed his first film in 1927, at the ripe age of twenty-four. He grew up with the silent cinema and made masterful films in the early 1930s, during the long twilight of Japanese silent filmmaking. Kurosawa became an assistant director in the late 1930s. Although he evidently directed large stretches of Yamamoto Kajiro’s Horse (1941), he didn’t sign a feature as director until he was thirty-three. His closest contemporary, and a director whom some Japanese critics consider his superior, is Kinoshita Keisuke. Kinoshita was born in 1912 and his first feature, The Blossoming Port, was released in the same year as Kurosawa’s debut.

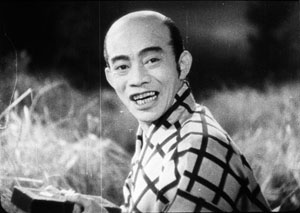

Kurosawa and Kinoshita began their careers making wartime propaganda. Their task was to display Japanese self-sacrifice and spiritual purity in stories of both the past and the present. In the Sanshiro Sugata films (1943, 1945), Kurosawa presents judo as an integral part of Japanese tradition and a path to enlightenment. Much of the external conflict is devoted to uniting martial arts (ju-jitsu, karate) under the rubric of the less aggressive but more powerful judo, and to showing how it can defeat American-style boxing. But the internal dimension is also important. Judo is a means of tempering character and accepting one’s proper place. Humble, unflagging devotion to one’s vocation becomes heroic.

The same quality can be found in The Most Beautiful (1944), a story of teenage girls working in a factory manufacturing lenses for binoculars and gunsights. Vignettes from the girls’ lives dramatize the need for cooperation and sacrifice, even as wartime demands for output threaten the girls’ health.

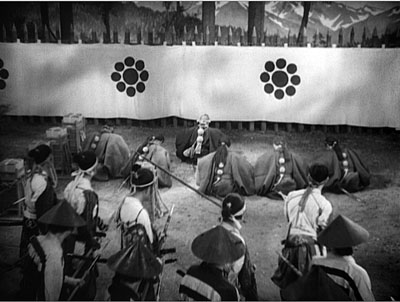

A more detached conception of the Japanese spirit underlies The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945). This adaptation of a plot from Noh and Kabuki theatre shows officers escorting a general through enemy territory. Disguised as monks, the bodyguards are forced to bluff their way through a checkpoint. The situation is one of hieratic suspense, made more tonally complex by Kurosawa’s addition of the movie comedian Enoken. Enoken plays a dimwitted porter reacting to the charade played out by his betters. By dramatizing one of the most famous episodes in Japanese literature, Kurosawa was reasserting the tradition of devotion to duty and honor. The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail was released the same month that the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima.

During earlier decades, Japanese cinema had created a complex tradition. In part, it conducted a sustained dialogue with Western cinema. Tokyo had access to a wide range of Hollywood movies, and directors studied American technique closely. Just as Ozu would not be Ozu without his early fondness for Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd, Mizoguchi learned a good deal from von Sternberg. Between 1938 and 1942, alongside German imports Tokyo theatres screened Fury, Only Angels Have Wings, The Sea Hawk, The Awful Truth, Angels with Dirty Faces, Boys Town, Young Tom Edison, Only Angels Have Wings, and many French titles. In 1942, with Hollywood films now banned, one could still see René Clair’s Le Million and À Nous la liberté—films that had been circulating in Japan since the early 1930s and could have served as models of flashy sound technique. It’s misleading to talk of Ozu as “purely Japanese” and Kurosawa as “Western”: All Japanese directors of the 1920s and 1930s were deeply acquainted with Western cinema, and American cinema in particular furnished a foundation for most local filmmaking.

Yet there are crucial differences. Japanese cinema welcomed extremes of stylistic experimentation that would have been rare in Western cinema. The 1920s swordplay films (chambara) pioneered rapid editing, handheld camerawork, and abstract pictorial design. (I supply some examples here.) Directors working in the contemporary-life mode (the gendai-geki) experimented similarly, often achieving remarkable visual effects and bold stylization. Mizoguchi and Ozu have become our emblems of this creative rigor and richness, but they are the peaks of what was a collective approach to filmic expression. Not every film was an experiment—indeed, most behave like Hollywood or European productions—but many ordinary movies, signed by unheralded directors, exhibit flashes of unpredictable imagination. This was the tradition of permanent innovation that directors of the Kurosawa-Kinoshita generation inherited.

As the war dragged on, however, Japanese studio productions lost much of their audacity. Production fell from over 400 films in 1939 to fewer than 100 in 1943. Censorship may have made filmmakers cautious about style as well as subject and theme. Most of the fifty-plus films I’ve been able to see from the period 1940-1945 are quite conservative aesthetically. Several of these seem to me quite good, but they rely on fairly standard Hollywood technique sprinkled with touches that had become markers of Japanese cinema (sustaining scenes in rather distant shots, using cuts rather than dissolves to shift scenes, and so on). Swordplay films become more severe and monumental. Even Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura (1941-42) and Ozu’s There Was a Father (1942), superb as they are, are more elevated in tone than the directors’ earlier works.

Against this backdrop, Kurosawa’s films stand out; they are the most extroverted works I know in this period. Their innovations remain vivid; Sanshiro Sugata, for one, with its hierarchy of competitors, its rivalry among schools, and its visceral technique, may have invented the modern martial arts film. But we should also realize that these early films build upon the traditions already firmly established in Japanese cinema.

Playing with the passing moment

Consider transitions. Kurosawa is famous for his elaborate links between sequences, from the hard-edged wipes to swift imagistic associations. But we should recall that transitional passages offer moments of flashy style in American and European cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, and indeed right up to this day. (For examples, go here and here.) In the same year as Sanshiro, Kinoshita gave us this moment in Blossoming Port. A con artist is trying to bilk money from a town. He bows, leaving an empty frame.

Without a discernible cut, heads pop into the empty frame, rocking to and fro.

Another cut reveals that the people we see are in a boat tossing on the waves, and the conman’s partner is enjoying an outing with the locals. Kurosawa’s scene-changes—sites of what Stephen Prince has called “formal excess”—can be seen as prolonged, imaginative reworkings of this tricky-transition convention.

Japanese filmmakers were more willing to play with the expressive and “decorative” side of filmmaking than most of their Western peers. Directors created not only flashy transitions but moments of stylistic playfulness within scenes. Sometimes this just adds to the overall tone of comedy, as in this pretty passage in Heiroku’s Dream Story, another 1943 release. The hero, played by Enoken, is squatting and talking to a charming girl (Takamine Hideko). She twirls her parasol between them, and we get a straight-on cut that creates a moment of abstraction as the parasol glides across the frame in contrary directions. (The vertical pair of frames shows the cut.)

This decorative symmetry would be rare in Hollywood outside a Busby Berkeley number, but it enlivens the characters’ exchange in a way similar to the more dramatic Rashomon sequence. To borrow a phrase that Kepler applied to nature’s way with snowflakes, a filmmaker may seek to ornament a scene by “playing with the passing moment.”

Likewise, in The Blossoming Port, as an older woman recalls a romance of her youth, the natural sound fades out and the back-projection behind the carriage shifts from the seaside to urban imagery of the period she’s remembering.

The frank artifice of this shot shows that Japanese filmmakers were eager to let us enjoy the forms with which they were working.

A similar explicitness about style can be seen in one of Kurosawa’s signature devices, the axial cut. This technique shifts the framings toward or away from the subject along the lens axis. If the shots are short enough, we sense a bump at the abrupt change of shot scale.

Kurosawa often uses this cutting to stress a momentary gesture or to prolong a moment of stasis. But it can structure a simple dialogue scene as well. In Sanshiro Sugata, the hero’s first conversation with Sayo takes place as they descend a stair toward a gateway. Kurosawa uses axial cuts to keep up with them as they move away from us down the steps. Illustrated with stills, this technique looks like a forward camera movement, but in fact these images come from separate shots.

The crux of the scene is Sayo’s revelation that the man Sanshiro must fight is her father, and instead of big close-ups to underscore his reaction, Kurosawa simply lets his hero halt while Sayo continues down the steps. The steady pattern of cut-ins to the characters’ backs makes Sayo’s sudden turn to the camera more vivid, and Sanshiro’s reaction is underplayed by not giving us direct access to his face.

An earlier entry traces theaxial cut back to silent film, when its jolting possibilities were exploited in Soviet montage cinema. Japanese directors also used the device often. Yamanaka Sadao, one of the most-praised directors of the 1930s, used axial cuts prominently in an early dialogue scene of Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937). The cuts are accentuated by low-height compositions that maintain the steep perspective of the street.

The technique gains more punch in Japanese swordplay films. Here is a percussive instance from Faithful Servant Naosuke (1939), four short shots yanking us inward in a way that Kurosawa would make his own.

Tom Paulus reminds me that Capra films sometimes make use of this technique, as in this string of concentration cuts from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Interestingly, Mr. Smith ran on several Tokyo screens in October 1941; it may have been the last Hollywood feature to receive theatrical distribution before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

To say that Kurosawa adapts traditional devices doesn’t take away from his accomplishment. No artist starts from zero, and in commercial cinema, filmmakers commonly revise schemas already in circulation. So Kurosawa puts his own spin on the axial cut, not only by using it frequently, but also by varying it in the course of a film. Sanshiro Sugata 2 makes the axial shot-change a sort of internal norm, but then varies it: inward or outward, cuts or dissolves, how great a variation of scale? When Sanshiro leaves Sayo, the three phases of his departure are marked by simple repetition: each time he halts and looks back, she responds by bowing.

Like the Rashomon sequence, this shows Kurosawa’s fondness for permuting simple patterns. But there’s an expressive payoff too. The framings that make Sayo dwindle to a speck give the axial cuts the forlorn, lingering quality we usually associate with dissolves. In addition, for viewers who know Sanshiro 1, the scene calls to mind the staircase passage we’ve already seen. Their first extended encounter is paralleled by their last one.

Axial cuts are easier to handle when the subject is unmoving, or moving straight toward or away from the camera. What about other vectors of motion? In The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, as the general’s bodyguards file out of the compound, they pass a line of soldiers in the foreground. Kurosawa combines concentration cuts with lateral cutting, so our men stalk leftward through the frame once, then again, then again, each time both closer to us and further along the row of soldiers.

Kurosawa revises other traditional techniques. You can find moments of extended stasis in swordplay films of earlier decades, and the technique surely owes something to the prolonged mie poses in Kabuki. But Kurosawa’s early films turn long pauses into living freeze-frames. Instead of using an optical effect, he simply asks his actors not to move! One combat in Sanshiro shows the audience caught in absolute stillness, staring at the result of Sanshiro’s throw. In Sanshiro 2, our hero and the boxer stand like statues in the prizefight ring until the American collapses. And in The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, the groups gathered at the checkpoint are absolutely unmoving for nearly fifty seconds as Benkei leads them in prayer.

This shot’s tactful, reverential composition echoes a fairly standard image for showing loyal retainers; here’s an example from a 1910s version of Chushingura.

In sum, I think that for his “manly movies” Kurosawa sifted through the Japanese film tradition and pulled out the most vigorous techniques he could find, all the while recognizing that rapid pacing needs the foil of extreme immobility. He compiled a digest of many arresting visual schemas available to him, and then pushed them in fresh directions. He realized as well that he could apply this sharp-edged style to genres dealing with modern life.

A most stubborn young woman

Although we think of Kurosawa as a “masculine” director, two of his finest films center on women. The Most Beautiful and No Regrets for Our Youth can be thought of as propaganda, but this label shouldn’t put us off. Propaganda works partly because it taps deep-seated emotions, and I’d argue that the formulaic nature of a “social command” can allow filmmakers a chance at emotional and formal richness. Because the message can be taken for granted or read off the surface, an ambitious director can go to town—nuancing the presentation, complicating its implications, taking the clichéd message as an occasion for pushing formal experiment. (Which is one aspect of what the Soviet montage filmmakers did.)

The Most Beautiful, probably the best movie ever made about child labor, starts off as a doctrinaire effort. Before even the Toho logo fades in, a title declares: “Attack and Destroy the Enemy.” The first fifteen minutes are filled with pledges to help the war effort, work to meet an emergency quota, obey orders, display filial devotion, build noble character, and think constantly of how making flawless lenses saves soldiers’ lives. The rest of the movie focuses on the pain of doing all this. This story of patriotic affirmation is steeped in tears.

The film’s structure looks forward to the ensemble-based, threaded plotlines employed in Red Beard and Dodes’kaden. We follow various stories, if only briefly, as the teenage girls push themselves beyond the limits proposed by their overseers. The factory directors and the dormitory mother are barely characterized, so that the focus falls on the girls who have left their homes to serve their country. One looks out the window when a train passes; another walks sobbing across a garden made of heaps of earth from each girl’s native village. When one girl falls from a roof, she promises to keep working on crutches. Another hides the fact that she has a fever. In this movie, workers cry out “Mother!” in their sleep.

Sanshiro Sugata pulses with the exuberance of a young man’s body itching for constant movement. Kurosawa’s second film applies his muscular techniques to a static situation: Girls bent over machines. True, there are interludes of a marching and volleyball, the latter calling forth a standardized stretch of montage, but the director’s central task is to dynamize conversations. He finds a remarkable array of options. We get good old axial cutting, but there are also jump cuts (as if the action were too urgent to wait for dissolves), resourcefully simple staging (see this entry), abrupt close-ups, quick flashbacks, and judicious long takes jammed with actors.

Off on the right stand two tall girls frowning and looking down; their quarrel will burst out in a later scene.

The virtuosity here is quieter than in Sanshiro, largely because of the insistent threat of shame. A Hollywood film of the period might play up the triumphant achievement of the quota, but here this goal fades away. Instead, the plot is driven by a nearly desperate fear of failure. The men in charge offer bluff reassurance, but in a reprise of high-school nerves, the girls fret constantly about doing less than their mates. Their anxiety is translated into gesture-based performance—not through Western hysteria but through gestures of lowering the eyes, bowing the head, turning one’s back. The Most Beautiful has some of the greatest back-to-the-camera scenes in film history, and Kurosawa doesn’t hesitate to insert some of these moments in wide shots, creating a delicate emotional counterpoint. At one moment the girls are distracted by a passing airplane but their leader is sunk in thought; at another moment the girls challenge the leader while her accuser can’t face her.

The girls’ stories are woven around Watanabe, the section leader. Somewhat older than the others and nowhere near as spontaneous or joyous, she’s the emblem of unremitting self-sacrifice. If Sanshiro matures in the course of his films, learning the humbling responsibilities of becoming a supreme fighter, she comes to her more mundane task already grown up. Noël Burch has pointed out that Kurosawa’s protagonists are notably stubborn, and Watanabe offers a prime instance.

At the climax she has to search through thousands of lenses for a flawed one that she accidentally let through. Kurosawa forces us to watch her, exhausted from hours of work, hunched over her microscope and keeping awake by singing a patriotic song. One shot holds on her groggy efforts for over ninety seconds, so we register both the enormity of her task and her obstinate refusal to quit. This shot will be paralleled by the film’s final one, which lasts almost exactly as long, when she returns to her workbench. Now her concentration is broken, again and again, by quiet weeping. Kurosawa claims that when he made the film he knew Japan would lose the war.

The ending of The Most Beautiful calls to mind a moment in another Kinoshita film, again one released in the same year as Kurosawa’s. Army (1944) ends on a similarly ambivalent note, with a frantic mother pushing through a crowd cheering recruits marching off to war. Through cries of “Banzai!” she stumbles along to get a last glimpse of him, but soon her trembling figure is lost in the excitement. It isn’t exactly an exalted note on which to close a patriotic film.

A mother is central to Watanabe’s sacrifice in The Most Beautiful as well, and her plight reminds me of historian John Dower’s telling me that Japanese soldiers may have charged into battle shouting the name of the emperor, but many died murmuring, “Mother.”

Like other filmmakers, Kurosawa had to execute an about-face when the Americans came to occupy Japan. Along with Mizoguchi, Kinoshita, and most others, he began to make films that condemned the “feudal” forces that had led Japan to war and affirmed the need for liberalizing the society, not least with respect to women’s roles. Kurosawa’s contribution was No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), a survey of the 1930s and 1940s through the experience of a daughter of the middle class. At first she’s oblivious to the authoritarian threat and then, awakened to her social mission, she plunges into what we would now call the politics of everyday life. With the same verve that Kurosawa dramatized sacrifice for the motherland, he quickens a liberal fable of emerging political consciousness. Again, he finds ways of making propaganda deeply moving, while leaving his unique stamp on the project.

I hope to write about No Regrets and other Kurosawa titles in the future. But one implication should already be clear. Kurosawa remains on our agenda through his commitment to a mode of storytelling that pursues vigor without lapsing into the diffuse busyness of today’s spectacles. He stretches our senses through staccato action, yet he drills into other moments so implacably that we are forced to see deeper. He lifts certain Japanese and imported traditions to a new pitch, in the process often creating something indelible and enduring.

The point of departure for all things Kurosawa is Donald Richie’s Films of Akira Kurosawa, first published in 1965 and updated since. It was a trailblazing auteur study, written from deep knowledge of the films and many encounters with the director. Another indispensible source is Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography (Knopf, 1982). Although it stops after the success of Rashomon, the book offers fascinating information about Kurosawa’s early life and first films. (“The Most Beautiful is not a major picture, but it is the one dearest to me.”) Information on the later films is collected in Bert Cardullo, Akira Kurosawa: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2008). A biographical overview, with details on each film’s production, is provided in Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf (Faber, 2001).

For background on Japan’s wartime cinema, the central work is Peter B. High’s The Imperial Screen (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003). See also John Dower’s magnificent surveys of the war and the postwar period, War without Mercy (Pantheon, 1987) and Embracing Defeat (Norton, 2000).

Noël Burch argues that Kurosawa is best understood as working within a tradition of indigenous Japanese art; his pioneering To the Distant Observer (University of California Press, 1979) is available online here. Linking formal preoccupations to changing subjects and themes, Stephen Prince’s The Warrior’s Camera (Princeton University Press, 1999) argues that Kurosawa was forging heroic figures appropriate to developments in Japanese society. In Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema (Duke University Press, 2000), Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto puts the films in political contexts, while also considering how Kurosawa has been understood within the Western academy.

Critics have long recognized that Kurosawa’s formal inventiveness came with an impulse toward large statement. Brad Darrach reconciled the two tendencies in an overheated specimen of Timespeak:

Not since Sergei Eisenstein has a moviemaker set loose such a bedlam of elemental energies. He works with three cameras at once, makes telling use of telescopic lenses that drill deep into a scene, suck up all the action in sight and then spew it violently into the viewer’s face. But Kurosawa is far more than a master of movement. He is an ironist who knows how to pity. He is a moralist with a sense of humor. He is a realist who curses the darkness—and then lights a blowtorch.

This comes from “A Religion of Film,” a remarkable primer on the art cinema in its American spring. It was published in Time of 20 September 1963 and is available here. The same antinomy of stylist vs. moralist persists, with less complimentary results, in Tony Rayns’ obituary in Sight and Sound (October 1998), p. 3 and in Dave Kehr’s recent review of the Criterion boxed set.

I wrote about Kurosawa’s work in our textbook Film History: An Introduction (third edition, McGraw-Hill, 2009), pp. 234-235 and 388-390. My larger arguments about classic Japanese film can be found in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (online here) and in two articles in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), “A Cinema of Flourishes: Decorative Style in 1920s and 1930s Japanese Film” and “Visual Style in Japanese Cinema, 1925-1945,” which analyzes some of the films I’ve considered here. I talk a little more about editing in Seven Samurai in this entry. In another I discuss how Kurosawa’s “humanism” fits into one 1950s ideological framework.

Yamanaka’s Humanity and Paper Balloons is available on DVD in the Eureka! series. For a cinematic homage to early Kurosawa, see Johnnie To’s Throw Down.

Thanks to Komatsu Hiroshi for supplying the date of Faithful Servant Naosuke. And as a PS, thanks to Luo Jin for pointing out a “slip of the finger”: the original post had Kurosawa older than Ozu!

PPS: 9 December: The Criterion site has just posted a reminiscence of Kurosawa by Donald Richie.

PPPS: 15 May 2010: Criterion has just announced that the four films discussed in this entry will be released as a separate collection on the Eclipse label.