Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Love isn’t all you need

Pat and Mike.

DB still in HK:

Last week the Hong Kong International Film Festival hosted Gerry Peary’s For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism. It’s a lively and thoughtful survey, interspersing interviews with contemporary critics with a chronological account that runs from Frank E. Woods to Harry Knowles. It goes into particular depth on the controversies around Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, but it even spares some kind words for Bosley Crowther.

Some valuable points are made concisely. Peary indicates that the alternative weeklies of the 1970s and 1980s were seedbeds for critics who moved into more mainstream venues like Entertainment Weekly. I also liked the emphasis on fanzines, which too often get forgotten as precedents for internet writing. In all, For the Love of Movies offers a concise, entertaining account of mass-market movie criticism, and I think a lot of universities would want to use it in film and journalism courses.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

Like many of our generation, Gerry became a mixture of critic and academic. He taught at several colleges, wrote for The Boston Phoenix, and published books, notably Women and the Cinema: A Critical Anthology (1977) and The Modern American Novel and the Movies (1977). Most recently he’s edited collections of interviews with Tarantino and John Ford. He has moved smoothly into online publishing with a packed and wide-ranging website.

Gerry’s documentary comes along at a parlous time, of course. Most of the footage was taken before the wave of downsizings that lopped reviewers off newspaper staffs, but already tremors were registered in some interviewees’ remarks. Apart from this topical interest, the film set me thinking: Is love of movies enough to make someone a good critic? It’s a necessary condition, surely, but is it sufficient?

Gerry’s film includes the inevitable question: What movie imbued each critic with a passion for cinema? I have to say that I have never found this an interesting question, or at least any more interesting when asked of a professional critic than of an ordinary cinephile. Watching Gerry’s documentary made me think that everybody has such formative experiences, and nearly everybody loves movies. But what sets a critic apart?

Elsewhere, I’ve argued that a piece of critical writing ideally should offer ideas, information, and opinion—served up in decent, preferably absorbing prose. This is a counsel of perfection, but I think the formula ideas + information + opinion + good or great writing isn’t a bad one.

You really can’t write about the arts without having some opinion at the center of your work. Too often, though, a critic’s opinions come down simply to evaluations. Evaluation is important, but it has several facets, as I’ve tried to suggest here. And other sorts of opinions can also drive an argument. You can have an opinion about the film’s place in history, or its contribution to a trend, or its most original moments. Opinions like these allow you to build an argument, drawing on evidence or examples in or around the movie in question. Several of our blog entries on this site are opinion-driven, but not necessarily evaluations of the movies.

Most people think that film criticism is largely a matter of stating evaluations of a film, based either in criteria or personal taste, and putting those evaluations into user-friendly prose. If that’s all a critic does, why not find bloggers who can do the same, and maybe better and surely cheaper than print-based critics? We all judge the movies we see, and the world teems with arresting writers, so with the Internet why do we need professional critics? We all love movies, and many of us want to show our love by writing about them.

In other words, the problem may be that film criticism, in both print and the net, is currently short on information and ideas. Not many writers bother to put films into historical context, to analyze particular sequences, to supply production information that would be relevant to appreciating the movies. Above all, not many have genuine ideas—not statements of judgments, but notions about how movies work, how they achieve artistic value, how they speak to larger concerns. The One Big Idea that most critics have is that movies reflect their times. This, I’ve suggested at painful length, is no idea at all.

Once upon a time, critics were driven by ideas. The earliest critics, like Frank Woods and Rudolf Arnheim, were struggling to define the particular strengths of this new art form. Later writers like André Bazin and the Cahiers crew tried to answer tough idea-based questions. What is distinctive about sound cinema? How can films creatively adapt novels and plays? What are the dominant “rules” of filmmaking ? (And how might they be broken?) What constitutes a cinematic modernism worthy of that in other arts? You could argue that without Bazin and his younger protégés, we literally couldn’t see the artistry in the elegant staging of a film like George Cukor’s Pat and Mike. Manny Farber, celebrated for his bebop writing style, also floated wider ideas about how the Hollywood industry’s demand for a flow of product could yield unpredictable, febrile results.

One of the reasons that Sarris and Kael mattered, as Gerry’s documentary points out, was that they represented alternative ideas of cinema. Sarris wanted to show, in the vein of Cahiers, that film was an expressive medium comparable in richness and scope to the other arts. One way to do that (not the only way) was to show that artists had mastered said medium. Kael, perhaps anticipating trends in Cultural Studies, argued that cinema’s importance lay in being opposed to high art and part of a raucous, occasionally vulgar popular culture. This dispute isn’t only a matter of taste or jockeying for power: It is genuinely about something bigger than the individual movie.

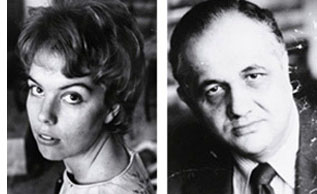

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

You can argue that these are old examples. What new ideas are forthcoming from mainstream film criticism? In the Q & A Gerry, like the rest of us, couldn’t come up with many. On reflection, I wonder if the rise of academic film studies forced ideas to migrate to the specialized journals and the Routledge monograph. These ideas also had a different ambit—sometimes not particularly focused on cinema, or on aesthetics, or on creative problem-solving.

Of course ideas don’t move on their own. A more concrete way to put this is that bright, conceptually oriented young people who in an earlier era would have become journalistic critics became professors instead. The division of labor, it seems, was to aim Film Studies at an increasingly esoteric elite, and let film reviewers address the masses. It’s an unhappy state of affairs that we still confront: recondite interpretations in the university, snap evaluations in the newspapers. You can also argue that print reviewers, by becoming less idea-driven, paved the way for DIY criticism on the net.

What about information, the other ingredient I mentioned? If we think of film criticism as a part of arts journalism, we have to admit that most of it can’t compare to the educational depth offered by the best criticism of music, dance, or the visual arts. You can learn more from Richard Taruskin on a Rimsky performance or Robert Hughes on a Goya show than you can learn about cinema from almost any critic I can think of. These writers bring a lifetime of study to their work, and they can invoke relevant comparisons, sharp examples, and quick analytical probes that illuminate the work at hand. Even academically trained film reviewers don’t take the occasion to teach.

Most of the print criticism I’ve seen today is remarkably uninformative about the range and depth of the art form, its traditions and capacities. Perhaps editors think that film isn’t worthy of in-depth writing, or perhaps their readers would resist. As if to recall the battles that Woods, Arnheim and others were fighting, cinema is still not taken seriously as an art form by the general public or even, I regret to say, by most academics.

Yet other aspects of information could be relevant. Close analysis offers us information about how the parts work together, how details cohere and motifs get transformed. For an example of how analysis can be brought into a newspaper’s columns, see Manohla Dargis on one scene in Zodiac.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

In any event, I’m coming to the view that the greatest criticism combines all the elements I’ve mentioned. As so often in life, love isn’t always enough.

Gerry’s documentary doesn’t distinguish between critics and reviewers, but we probably should. Reviewers typically give us opinions and a smattering of information (plot situations, or production background culled from presskits), wrapped up in a writing style that aims for quick consumption. Today anybody with a web connection can be a reviewer.

Exemplary critics try for more: analysis and interpretation, ideas and information, lucidity and nuance. Such critics are as rare now as they have ever been. Far from being threatened by the Internet, however, they have more opportunities to nourish film culture than ever before.

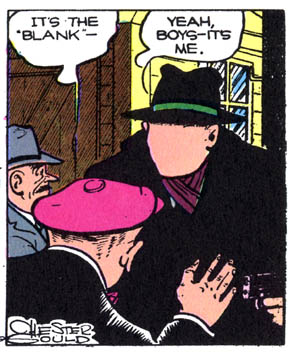

The Big Combo.

PS 4 April (HK time): Thanks to Justin Mory for correcting a name error in the original post!

Gradation of emphasis, starring Glenn Ford

DB here:

Charles Barr’s 1963 essay “CinemaScope: Before and After” has become a classic of English-language film criticism. (1) It proffers a lot of intriguing ideas about widescreen film, but one idea that Barr floated has more general relevance. I’ve found it a useful critical tool, and maybe you will too.

Grading on a curve

Barr called the idea gradation of emphasis. Here’s what he says:

The advantage of Scope [the 2.35:1 ratio] over even the wide screen of Hatari! [shot in 1.85:1] is that it enables complex scenes to be covered even more naturally: detail can be integrated, and therefore perceived, in a still more realistic way. If I had to sum up its implications I would say that it gives a greater range for gradation of emphasis. . . The 1:1.33 screen is too much of an abstraction, compared with the way we normally see things, to admit easily the detail which can only be really effective if it is perceived qua casual detail.

The locus classicus exemplifying this idea comes in River of No Return (1954). When Kay is lifted off the raft, she loses her grip on her wickerwork bag and it’s carried off by the current. (See the frame surmounting this entry.) Kay and her boyfriend Harry are rescued by the farmer Matt. As all three talk in the foreground, the camera catches the bundle drifting off to the right.

Even when the men turn to walk to the cabin, Preminger gives us a chance to see the bundle still drifting downstream, centered in the frame.

The point of this shot, Barr and V. F. Perkins argued, is thematic. As Kay moves from the mining camp to the wilderness, she will lose more and more of her dance-hall trappings and be ready to accept a new life with Matt and Mark. The last shot of the film shows her final traces of her old life cast away.

Cutting in to Kay’s floating bag would have been heavy-handed; if you stress a secondary element too much, it becomes primary. Barr reminds us that any film shot can include the most important information, as well as information of lesser significance. A film can achieve subtle effects by incorporating details in ways that make them subordinate as details and yet noticeable to the viewer. Or at least the alert viewer.

In Poetics of Cinema, I wrote an essay on staging options in early CinemaScope, and Barr’s idea helped me illuminate some of the strategies I discuss. (For earlier comments on Barr on Scope and River of No Return, see my article elsewhere on this site.) Today I want to consider how the notion of gradation of emphasis has a more general usefulness.

Barr contrasts the open, fluid possibilities of CinemaScope with two other stylistic approaches, both found in the squarer 1.33 format. The first approach is the editing-driven one he finds in silent film. This tends to make each shot into a single “word,” and meaning arises only when shots are assembled. Barr associates this approach with Griffith and Eisenstein. The second approach, only alluded to, is that of depth staging and deep-focus shooting, typically associated with sound cinema of the late 1930s and into the 1950s.

Both of these approaches, montage and single-take depth, lack the subtle simplicity of Scope’s gradation of emphasis.

There are innumerable applications of this [technique] (the whole question of significant imagery is affected by it): one quite common one is the scene where two people talk, and a third watches, or just appears in the background unobtrusively—he might be a person who is relevant to the others in some way, or who is affected by what they say, and it is useful for us to be “reminded” of his presence. The simple cutaway shot coarsens the effect by being too obvious a directorial aside (Look who’s watching) and on the smaller [1.33] screen it’s difficult to play off foreground and background within the frame: the detail tends to look too obviously planted. The frame is so closed-in that any detail which is placed there must be deliberate—at some level we both feel this and know it intellectually.

To see Barr’s point, consider a shot like this one from Framed (1947).

The shot, rather typical of 1940s depth staging, displays an almost fussy precision about fitting foreground and background together. That bartender, for instance, stands squeezed into just the right spot. (2) Barr claims that we sense a certain contrivance when primary and secondary centers of interest are jammed into the 1.33 frame like this.

We don’t sense the same contrivance in the widescreen format, he suggests. Barr assumes, I think, that the sheer breadth of any Scope frame will include areas of little consequence, whereas that’s comparatively rare in a 1.33 composition. This is an intriguing hunch, but uninformative patches of the frame may not be intrinsic to the Scope technology. Perhaps the fairly neutral and inexpressive uses of Scope that dominate the early 1950s, the sense of empty and insignificant acreage stretching out on all sides, make us expect that little of importance will be found there. Accordingly, directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail in this stretch of real estate.

Anyhow, Barr indicates that if static deep-space staging made the frame too constrained, 1930s and 1940s directors who combined depth with camera movement created more spacious and fluid framings. He suggests that Mizoguchi, Renoir, and others anticipated the possibilities of Scope.

Greater flexibility was achieved long before Scope by certain directors using depth of focus and the moving camera (one of whose main advantages, as Dai Vaughan pointed out in Definition 1, is that it allows points to be made literally “in passing”). Scope as always does not create a new method, it encourages, and refines, an old one (pp. 18-19).

Barr believes that Scope positively encouraged gradation of emphasis, and that widescreen directors of the 1950s and 1960s have made the most fruitful use of the strategy. But he allows directors of all periods utilized gradation of emphasis, even in the standard 1.33 format. This is, I believe, a powerful idea.

Before Scope: Making the grade

Barr’s discussion of silent cinema, relying on notions of editing associated with Griffith and Soviet directors like Eisenstein, is done with a broad brush, but it’s typical of the period in which he was writing. We didn’t know much about silent filmmaking until archivists started to exhume important work in the 1970s. It’s no exaggeration to say that we haven’t really begun to understand the first twenty-five years of cinema until fairly recently.

In a way, the staging-driven tradition of the 1910s, which I’ve often mentioned on this site (here and here and here), exemplifies some things that Barr would approve of. Directors of that period made extraordinary use of the frame and compositional patterning. They staged action laterally, in depth, or both. They let shots ripen slowly or burst with new information. This approach to using the full frame (with only occasionally cut-in elements) has come to be called the tableau style, emphasizing its similarity to composition of a painting—although we shouldn’t forget that these films are moving paintings, and the compositions are constantly changing. The result is that emphasis tends to be modulated and distributed among several points of interest.

Central to this strategy, I think, was camera distance. American directors tended to set the camera moderately close, cutting figures off at the knees or hips, and by taking up more frame space, the foreground actors tended to limit the area available for depth arrangement or for significant detail.

This shot from Thanhouser’s The Cry of the Children (1912) is a rough 1910s equivalent of the crammed shot from Framed above. (See also the tightly composed shots from DeMille’s Kindling (1915) here.)

The European directors, by contrast, tended to let the scene play out in more distant shots, creating spacious framings of a sort that would be reinstituted in early CinemaScope. Consider this shot from Holger-Madsen’s Towards the Light (Mod Lyset, 1919) and another from Island in the Sun (1957).

Both, it seems to me, have the type of open composition and the foreground/ background interplay that Barr praises in his article.

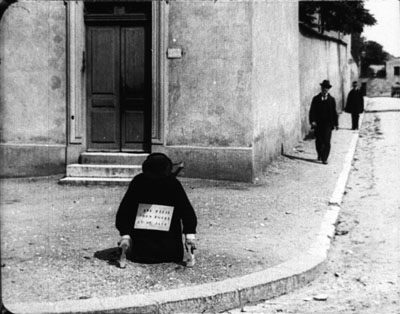

We can go back further. The Lumière brothers’ cameramen made fiction films as well as documentaries, and we occasionally find moments that suggest early efforts at gradation of emphasis. In Le Faux cul-de-jatte (1897), an apparent amputee is begging in the foreground while in the distance a man is walking down the street.

A cop crosses the street from off right and follows the pedestrian.

As the foreground fills up, the man we’ve seen in the distance gives the beggar some money.

As he goes out left, the cop is still approaching, and a vagrant dog appears.

The cop comes to the beggar, partially blocking the dog, who takes care of other business. (Not everything in this movie is staged.)

The cop checks the beggar’s papers and finds them to be suspect. The fake amputee jumps up and races off in the distance, with the cop pursuing.

As with many staged Lumière shorts, several figures converge in the foreground in order to create a culminating piece of action. Here the distant man and the cop, both secondary centers of interest, serve as a kind of timer, assuring us that something will happen when they meet at the beggar.

These are just some quick examples. We should continue to study the ways in which, with minimal use of editing, early filmmakers found ingenious ways to create gradation of emphasis. (2)

Some uses of grading

Barr, like most critics writing for the British journal Movie, was sensitive to the ways in which technique has implications for character psychology and broader thematic meanings. Kay’s bundle is one point along a series of changes in her character and her situation. But gradation of emphasis can serve more straightforward narrative purposes as well.

Consider our old friends, surprise and suspense. In the original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Dan Evans is confronting the ruthless outlaw Ben Wade.

We get a string of reverse shots.

Then in one shot of Wade, without warning, a shadowy figure emerges out of focus in the left background.

Now we realize that Evans has been diverting Wade from the fact that the sheriff’s posse is surrounding him. Now we wait for Wade to discover it; how will he react?

While we’re on Glenn Ford, another nice example occurs in Framed. Mike Lambert has been romancing a woman named Paula, but we know that she and her lover Steve are plotting to fake Steve’s death and substitute Mike’s body.

She brings Mike to Steve’s elegant country house, having presented Steve as someone she knows only slightly. When Mike goes into the bathroom to wash up, we notice something important behind him.

With Mike at the sink, we have plenty of time to recognize Paula’s robe. Director Richard Wallace prolongs the suspense by giving us a new shot of Mike in the mirror, with the robe no longer visible.

But when Mike turns to leave, a pan following him brings him face to face with what we saw, accentuated by a track forward.

We get Mike’s reaction shot, followed by a cut to Steve and Paula downstairs, suspecting nothing. “So far, so good,” says Steve, looking upward at the bathroom.

The rest of the scene will play out with Mike aware that they’re deceiving him. As often happens with suspense, we know more than any one character: We know the couple’s scheme and Mike doesn’t, but they don’t (yet) know that Mike is now on his guard.

This isn’t as subtle a case as River of No Return, but I suspect that it’s more typical of the way Hollywood filmmakers use gradation of emphasis. Paula’s bathrobe is a good example of what I called in The Classical Hollywood Cinema the strategy of priming: planting a subsidiary element in the frame that will take on a major role, even if initially its presence isn’t registered strongly. My example in CHC was a coat rack in the Dean Martin/ Jerry Lewis comedy The Caddy (1953). In effect, the distant pedestrian in the Lumière film is an early example of priming.

Howard Hawks adopts the Lumière technique in order to sustain a flow of dialogue in Twentieth Century (1934). Here the foreground conversation is accompanied by a procession of people emerging in the distance and stepping up to take part.

The shot concludes, as does the shot of Faux cul-de-jattes, with a retreat from the camera.

The priming of secondary elements here, the summoning of the train attendant and the conductor, obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum that the director ought to construct each shot so as to prepare for what will come next.

As Barr indicates, the idea of gradation shades insensibly off into general matters of cinematic expression. In The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), the bank robber has hitched a ride with an unassuming civilian, and they stop for gas. When the attendant shows a picture of his little girl, the robber gratuitously insults her. (“With those ears she’ll probably fly before she can walk.”)

Later, the station attendant hears a radio broadcast describing the fugitive. First he has his head cocked as he listens attentively, but then his gaze drifts to the picture of his little girl.

The attendant is the center of dramatic interest, but when he looks at the picture, so do we (primed by the view of it earlier). Instantly we understand that the attendant’s resolve to call the police springs partly from an urge to get even with the man who insulted his daughter. A minor instance, surely, but it illustrates Barr’s point that the notion of gradation of emphasis leads us to consider “the whole question of significant imagery.”

The more the merrier

Barr seems to favor a plain style; he prefers Preminger’s quiet framings to the rococo imagery of Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954). Presumably the famous shot above from Wyler’s Best Years of Our Lives (1946) would be too obviously composed for Barr’s taste.

But there is merit in considering how a secondary center of interest can vie for supremacy. André Bazin declared Wyler’s shot a bold stroke exactly because its self-conscious precision created a tension between what was primary and what was subordinate. (3) The action in the foreground is of dramatic interest because Homer has learned to play the piano, and this represents a phase of his coming to terms with his wartime disability. Yet the most consequential action is taking place in the distant phone booth, where Fred breaks up with Al’s daughter Peggy. The gradation of emphasis is inverted, and we wait in suspense to find out what happens. Bazin taught us to recognize that what appears to be primary may actually be creatively distracting us from the scene’s principal action. (4)

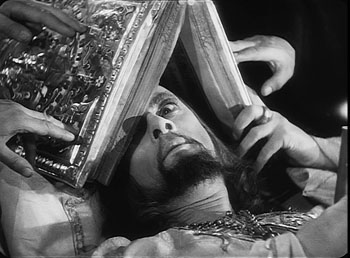

A director can also turn a primary center of interest into something secondary, but powerful. In one sequence of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible I (1944), the apparently dying tsar is being prayed over by churchmen. Ever suspicious, he peers out from under the book, using only one eye.

As the scene develops, Prince Kurbsky meets Ivan’s wife and tries to seduce her. In the background an icon’s eye glares out, as if Ivan is watching them.

The single eye, which is a motif we find in other Eisenstein films, becomes a significant one throughout both parts of Ivan. More generally, this device manifests Eisenstein’s conception of polyphonic montage, which explored how the filmmaker can control all the various aspects of his images and make them weave throughout the film—promoting one at one moment, demoting it at another. (5)

Barr’s essay assumes that Eisenstein’s montage stripped each image down to a single meaning. In fact, though, Eisenstein wanted to multiply the sensuous and intellectual implications of each shot by weaving objects, gestures, body parts, musical motifs, and the like into an ongoing stylistic fabric. Each shot’s gradation of emphasis can suggest thematic parallels, deepen the drama, or heighten emotional expression, just as a complex score enhances an operatic scene.

Tati as well likes to create an interplay between primary and subsidiary centers of interest. Or rather, he sometimes abolishes our sense of what is primary and what isn’t. The crowded compositions of Play Time (1967) often bury their gags in a welter of inessential details. During the lengthy scene in the Royal Garden restaurant, a minor running gag involves the dyspeptic manager. He has just mixed some headache medicine with mineral water, but the action is easily lost within the tumultuous image. Even the soundtrack cues us only slightly, with a bit of fizz among the music and crowd noise.

As the manager lowers the glass, Hulot thinks it’s pink champagne being offered to him.

Rolling the stuff in his mouth, Hulot realizes his mistake as he earns a stare from the manager.

There is so much competing sound and activity in the shot that some viewers simply don’t notice this bit at all. In Play Time, gradation of emphasis is often flattened out, leaving us to rummage around the composition for the gag.

Some final notes

Barr was not particularly interested in the mechanics of how we come to notice something in the shot, be it primary or secondary in value. In On the History of Film Style, I suggested that many aspects of technique work to call attention to any element in the field. The filmmaker can put a something in motion, turn it to face us, light it more brightly, make it a vivid color, center it in the frame, have it advance to the foreground, have other characters look at it, and so on. These tactics can work together in a complex choreography. In Figures Traced in Light, I argued that they depend on the fact that we scan the frame actively; the techniques guide our visual exploration. (6)

You can see this guidance at work in most of the examples I’ve mentioned. In River of No Return, we are coaxed into noticing Kay’s bundle because we’re cued by movement (the bundle falls and drifts off), performance (she shouts, “My Things!” and stretches out her arm), music (we hear a chord as the bundle splashes), and framing (Preminger’s camera pans slightly as the trunk drifts away). The critic can refine our sense of the effects that a film arouses, but it’s one task of a poetics of cinema, as I conceive it, to examine the principles and processes that filmmakers activate in achieving those effects.

Finally, we might ask: To what extent do we find gradation of emphasis in current filmmaking? Today’s American cinema relies heavily on editing, using a style I’ve called intensified continuity. Each shot tends to mean just one thing, and once we get it we’re rushed on to the next. The unforced openness of the wide frame that Barr celebrated has been largely banned, in favor of tight singles—even in the 2.40 anamorphic format. It seems that most filmmakers are no longer concerned with gradation of emphasis within their shots.

To find this strategy surviving at its richest, I think we have to look overseas. If you want names: Angelopoulos, Tarr, Kore-eda, Jia, Hou. (7)

(1) It was published in Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4 (Summer, 1963), 4-24. Unfortunately, it’s not available free online, nor is a complete version available in anthologies, so far as I know. If you have access to online journal databases, you can find it. Otherwise, off to the library w’ye!

(2) In the Poetics of Cinema piece (pp. 303-307), I argue that some early uses of Scope tried to approximate such tightly organized composition, despite technological barriers to focusing several planes of action.

(3) See André Bazin, “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo, trans. Cardullo and Alain Piette (New York: Routledge, 1997), 14-16.

(4) Actually the phone booth is primed for our notice by earlier shots in Butch’s tavern. See On the History of Film Style, 225-228.

(5) For more on Eisenstein’s idea of polyphonic montage, see my Cinema of Eisenstein (New York: Routledge, 2005) and Kristin’s Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

(6) For some empirical evidence of this guided scanning, see the work of Tim Smith at his website and in this entry on this site.

(7) I discuss some of these alternatives in On the History of Film Style and the last chapter of Figures Traced in Light.

Eternity and a Day.

PS 15 Nov. Two more items. First, if the ideas floated here intrigue you, you might want to take a look at an earlier entry on this site, called “Sleeves.”

Second, I had planned to include one more example, but forgot it. In Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Andy Hanson’s life is unraveling. We follow him back to his apartment, and as he enters on the extreme left, his wife Gina is visible sitting on the extreme right, her back to us.

Gina forms a secondary center of attention, but the key to the upcoming action is revealed in a third point of interest: the black suitcase pressed against the right frame edge. The shot tells us, more obliquely than one showing her leaving the bedroom with the case, that she is planning to leave him. Lumet’s image, reminiscent of the framing of the trunk in River of No Return, shows that gradation of emphasis isn’t completely dead in American cinema. The orange scrap of yarn, knotted to the handle for baggage identification, is a nice touch of realism as well as a welcome color accent that further draws the suitcase to our notice.

Categorical coherence: A closer look at character subjectivity

Subjective

[NOTE: There are some spoilers here, though I’ve tried to avoid giving away the ends of the films I mention. Teachers who show clips in class would probably want to do the same. Some of the films mentioned here would be good choices to show in their entirety to classes when they study Chapter 3 of Film Art.]

Kristin here—

We have had occasion to mention the Filmies list-serve of the Department of Communication Arts’ Film Studies area here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Current and past students and faculty, sometimes known as the “Badger squad,” share news, links, and requests for information. Once in a while a topic is raised for discussion. These exchanges are usually fascinating, and when we have felt that they might be of interest to a general audience, we have used them as the basis for blog entries. (See here and here.)

Another occasion arose recently, one which relates to the teaching of Film Art: An Introduction. Matthew Bernstein, of Emory University, queried the group about suggestions for teaching a section of the third chapters, “Narrative as a Formal System.” He found that the section, “Depth of Story Information,” gives some students trouble. They can’t grasp the distinction we make between perceptual and mental subjectivity.

Our definitions of the terms go like this. Perceptual subjectivity is when we get “access to what characters see and hear.” Examples are point-of-view shots and soft noises suggesting that the source is distant from the character’s ear. In contrast, “We might hear an internal voice reporting the character’s thoughts, or we might see the character’s inner images, representing memory, fantasy, dreams, or hallucinations. This can be termed mental subjectivity.”

We then go on to give a few examples. The Big Sleep has little perceptual subjectivity, while The Birth of a Nation contains numerous POV shots. We see the heroine’s memories in Hiroshima mon amour and the hero’s fantasies in 8 ½. Filmmakers can use such devices in complex ways, as when in Sansho the Bailiff, the mother’s memory ends not by returning to her in the present, but to her son, apparently thinking of the same things at the same time.

Yeah, but what about …?

Filmmakers don’t always use these categories in straightforward ways. They may oscillate between perceptual and mental representations and events. Films may present narrative events that make the distinction between characters’ perceptions and their mental events ambiguous. That’s why in introducing the concepts, we stress that “Just as there is a spectrum between restricted and unrestricted narration, there is a continuum between objectivity and subjectivity.

Easy to say, but not necessarily so easy to grasp for a student who’s trying to understand these categories. They need to start with simple examples to familiarize themselves with the basic distinction before going on to what the likes of Resnais, Fellini, and Mizoguchi can throw at them. But some students immediately proffering exceptions. As Charlie Keil, of the University of Toronto, put it in his post on the subject, “I hardly need add that students, even the least analytically astute, border on the brilliant when it comes to suggesting examples that provide challenges to categorical coherence.”

Looking over the one and a half pages of the textbook that we devoted to depth of narration, you might find it fairly straightforward. Once you start looking for ways to teach the concepts without bogging down in too many nuances and subcategories, though, the passage does seem challenging. What follows is a suggestion about how someone might go about explaining and utilizing examples. It also points up some ways we might revise this passage of the book for its next edition.

What it’s not

One obstacle that Matthew has found is that students are used to thinking of “subjective” as meaning something like “biased,” as in “here’s my subjective opinion on that.” It might be useful to point out that this is only one meaning of the word. The dictionary definition that comes closest to the way we use it in Film Art is this: “relating to properties or specific conditions of the mind as distinguished from general or universal experience.” For film, we specify that “subjective” means either sharing the characters’ eyes and ears (properties) or getting right inside his or her mind (conditions).

Another misconception comes when students assume that the facial expressions, vocal tones, and gestures used by actors are subjective because they convey the characters’ feelings. Again, best to scotch that notion up front. Those techniques are projected outward from the character, and we observe them. Cinematic subjectivity goes inward.

One step at a time

Another distinction to stress early on is the basic one we make between film technique and function. There are a myriad of film techniques that could be used in either objective or subjective ways. To take a simple example, a low camera angle might indicate the POV of a character lying down and looking up at something; that’s perceptual subjectivity. A low angle of a skyscraper in an establishing shot might simply be the objective narration’s way of showing where a new scene will occur.

In contrast, indicating perceptual and mental subjectivity are two specific kinds of functions. Filmmakers can call upon whatever cinematic techniques they choose, and historically the more imaginative ones have shown immense creativity in trying to convey what characters see and think.

Some films depend heavily upon subjectivity, but objective narration is more common. There are many films that give us little access to characters’ perceptual and mental activities. Apart from The Big Sleep, there are films like Anatomy of a Murder, or virtually anything by Preminger. Most films use subjectivity sparingly. So let’s assume the students can tell that objective narration is the default.

With that out of the way, we can go back to basics. Both perceptual and mental subjectivity depend on being “with” the character in a strong way, as opposed to observing him or her as we would see another person in real life.

Perceptual subjectivity is fairly simple. The camera is in the character’s place, showing what he or she sees. The microphone acts as the character’s ears. Other characters present in the scene could step into the same vantage point and observe the same things.

So the test could run like this: As a viewer, when we see something in a film, is it really present within the scene? Could someone else in the same position see and hear the same things? Or is it a purely mental event, something no one else could see and hear, even if they stood beside the character or stepped into the place where that character had been standing?

If I were teaching the concept of narrational subjectivity as Film Art defines it, I would stress the notion of a continuum. After starting with very clear examples of both perceptual and mental subjectivity, I would progress to more ambiguous, mixed, or tricky instances.

Contributing to this discussion on the Filmies list, Chris Sieving, of the University of Georgia, says he shows a  clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

There are other films that contain a lot of POV shots but intersperse them with objective ones. Rear Window is an obvious case. When Jefferies is alone, we see the courtyard events from his POV, a fact which is stressed by his use of binoculars and his long camera lenses to spy on his neighbors. This is clearly perceptual rather than mental. We never doubt that what we see through the hero’s eyes is real; we don’t believe that he’s making things up to entertain himself or because his mind is unbalanced. For one thing, there are two other characters who visit at intervals and see the same things that he does. We and they might question whether Jefferies’ interpretation of what he sees is correct, but we assume that the story’s real events have been conveyed to us through his eyes and ears. Only if we saw something like his fantasy of how he imagines his neighbor might have killed his wife would we move into the mental realm.

These two films foreground their use of POV. Usually, though POV shots are slipped into the flow of the action smoothly. Scenes of characters looking at small objects or reading letters often cut to a POV shot to help us get a look at an important plot element. At intervals during Back to the Future, Marty looks at a picture of himself and his siblings, gradually fading away to indicate that the three of them might never be born if he doesn’t succeed in bringing their parents together. It’s a simple way of reminding us what’s at stake and that Marty’s time to solve the problem is running out.

The Silence of the Lambs uses many POV shots and provides an excellent case of narration switching frequently and seamlessly between objective and subjective. Most of the POV views are seen through Clarice’s eyes, but sometimes through those of other characters. The first view of Lecter is a handheld tracking shot clearly established as what she sees as she walks along the corridor in front of the row of cells.

The scenes of Clarice conversing with Lecter develop from conventional over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot to POV shot/ reverse shot as both characters stare directly into the lens. (In Film Art, we use this device as an example of how style can shape the narrative progression of a scene [p. 307, 8th edition]). Other characters have POV shots as well, most noticeably, when Buffalo Bill twice dons night-vision goggles and we briefly see the world as he does.

Occasionally we see the POV of even minor characters, as when Lecter’s attack on his guard is rendered with a quick POV shot of Lecter lunging open-mouthed at the camera and then an objective shot of him grabbing the guard.

In their minds

Let’s jump to the other end of the continuum. Here we find a clear-cut use of mental subjectivity for fantasies, hallucinations, and the like. Obviously no one else present, unless he or she is posited as having special telepathic abilities, can see and hear what takes place only in a character’s mind.

Such fantasies are a running gag on The Simpsons, where Homer’s misinterpretations, distractions, and visions of grandeur are shown either in a thought balloon or superimposed on his skull. In the example above, he abruptly starts “watching” a little cartoon after assuring Lisa that she has his complete attention. No one could mistakenly assume that these exist anywhere but in Homer’s imagination.

In Buster Keaton’s Our Hospitality, the hero receives a letter telling him he has inherited a Southern home. After an image of him thinking there is a dissolve to a view of a large, pillared house. Later, when he arrives at his small, ramshackle house, he stands staring in a similar situation, and here there is a fade-out to his dream house, which abruptly blows up. The humor in the second scene would be impossible to grasp if we didn’t easily understand that the shot of the house exists only in his mind.

Whole films can be built around fantasies. A large central section of Preston Sturges’ black comedy Unfaithfully Yours consists of a husband envisioning three different ways he might kill his supposedly cheating wife, all set to the musical pieces he is conducting at a concert. Fellini’s 8 ½ is only the most obvious example of how the art cinema often brings in fantasies. Other examples include Jaco van Dormael’s Toto le héros or Bergman’s Persona.

Once students have grasped the basic distinction between perceptual and mental subjectivity, it might be useful to emphasize the continuum by moving directly to its center, where the two types coexist.

The middle of the continuum: Ambiguity and simultaneity

Right in the middle of the continuum between the pure cases we find ambiguous cases. Filmmakers can create deliberate, complex, and important effects by keeping it unclear whether what we see is a character’s perception of reality or his/her imaginings.

1961 was a big year for ambiguous subjectivity, with two of the purest cases appearing. One was a genre picture, the other a controversial art film.

The first is the British horror film, The Innocents, directed by Jack Clayton and based on Henry James’s novella, The Turn of the Screw. In several scenes, a new governess at a country estate sees frightening figures whom she takes to be ghosts haunting the two children entrusted to her. We see these figures as she does, but we never see them except when she does. The children behave very oddly in ways that might be consistent with her belief, yet they deny seeing any ghosts. Finally the governess tries to force the little girl to admit that she also sees the silent female figure standing in the reeds across the water. Does the child’s horrified expression reflect her realization that the governess knows about her secret relationship with the ghosts? Or is she simply baffled and frightened by the governess’s increasingly frantic demands that she confess to seeing something that in fact she can’t see?

From the first appearance of the eery figures, the question arises as to whether the governess is imagining the ghosts or they are real, controlling the children, who try to keep them secret. There are apparent clues for either answer. By the end, we arguably are no closer to knowing whether the ghosts are real or figments of the heroine’s imagination.

Since Last Year at Marienbad appeared, critics have spilled gallons of ink trying to fathom its symbolism and sort out the “real” story that it tells. Clearly there are contradictions in events, settings, and voiceover narration. The second of the three accompanying images depicts the heroine as the hero’s voiceover describes their first meeting. They talked about the statue that stands beside her, seen against the formal garden of walks lined with pyramid-shaped shrubs. Yet another version of the first meeting starts, this time with the characters and the same statue against a background of a large pool. Later scenes in these locales display the same inconsistencies.

Are such contradictions the result of one character’s fantasies or of the conflicting memories that two characters have of the same event? Or are the contradictions not the products of subjectivity at all but just the playfulness of an objective, impersonal narration, manipulating characters like game pieces to challenge the viewer? (Our analysis of Last Year at Marienbad is available here on David’s website. It and all the Sample Analyses that have been eliminated from Film Art to make room for new essays are available here as pdf’s; the index to them is here, about halfway down the page.)

It’s not a good example of subjectivity to show students, but just as an aside, the screwball comedy Harvey is an interesting case, a sort of reversal of the Innocents situation. The narration withholds a character’s perceptual and mental events. Elwood P. Dowd describes what he sees and hears: a six-foot talking rabbit invisible to us and to all the other characters. The story concerns whether Dowd’s relatives will institutionalize him for insanity, and we assume along with them Harvey is a mere delusion. Thus the narration seems to be objective—or, the ending asks, has it been very uncommunicative, withholding something that the hero really does see and hear? True, throughout the film the framing leaves room for Harvey, as if he were there. One could argue, though, that these framings simply emphasize that the giant rabbit isn’t visible to us or the other characters and hence isn’t likely to really exist.

A film can easily present both perceptual and mental subjectivity at the same time. A POV shot may be accompanied a character’s voice describing his or her thoughts and feelings. Matthew shows his class part of the opening section of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, where a stroke victim’s extremely limited sight and hearing are rendered in juxtaposition with his voice telling of his reactions to his new situation. It is one of the most extensive and successful uses of such a combination in recent cinema, and it might be very effective in differentiating the two for introductory students.

A scene can also move rapidly back and forth between a character’s perceptions and his or her thoughts. Charlie writes that he shows his students the scenes of Marion Crane driving in Psycho. While the car is moving, almost every alternating shot is a POV framing of the rearview mirror or through the windshield. At that same time, we hear the voices of her lover, her boss, her fellow secretary, and the rich man whose money she has stolen while she imagines how they would react to her crime.

Showing scenes like these, where both types of subjectivity are used and clearly distinguishable might be more useful for students than showing several scenes that contain only one or the other.

Flashbacks, Voiceovers, and Altered States

In his original query to the Filmies, Matthew also said that students have problems with flashbacks: “Particularly, they resist the idea that a flashback is an example of subjective depth in general, even if the flashback unfolds objectively.” I can think of two ways to explain this.

First, classical films tend not to have flashbacks that just start on their own. To be sure, some do: a track-in to an important object and a dissolve can signal the start of a passage from the past, without a character being there. But more often a character is used to motivate the move into the past. A thoughtful look may do it, or a character may describe the past to someone else. In either case, the flashback is coming “from” the character and is assumed to show approximately what he or she is remembering. Occasionally the flashback may be a lie rather than objective truth, as we know from Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, The Usual Suspects, and a few other films.

In Poetics of Cinema’s third essay, David argues that most flashbacks in films are motivated as a character’s memory, but what is shown often strays from what he or she knew or could have known. He suggests that the prime purposes of most flashbacks is to rearrange the order of story events, and the character recalling or recounting simply provides an alibi for the time shift.

So we might think of character-motivated flashbacks as subjective frameworks that also contain objectively conveyed narrative information.

Second, the fact that flashbacks slip in objective information into characters’ memories is a convention. It’s a widely used method for presenting us with two things at once: first, a character’s memories and second, some story information that the viewer needs to have—even if the character couldn’t know about it. As we watch movies, we frequently accept conventions for the sake of being entertained. Beings that travel to Earth from distant galaxies speak English, high school kids can put together shows that wind up triumphing on Broadway, and people who drive up to buildings in crowded cities always find perfect parking spots. In a similar way, implausible mixtures of subjectivity and objectivity in flashbacks is just something we have to accept.

There are two other techniques that didn’t get mentioned during the discussion but that might confuse students.

What about shots showing the vision of a character who is drunk, dizzy, drugged, or otherwise unable to see straight? The most common convention is to include a POV shot that’s out of focus, perhaps accompanied by a bobbing handheld camera. Other characters in the scene, assuming they are not similarly impaired, would not see the surroundings in the same way.

Still, I think the same perceptual/mental distinction holds for such moments. The fuzziness and the lack of coordination are physical effects that are not being imagined by the character. They remain in the perceptual realm. Mental effects of impairment would be dreams or hallucinations. Some examples: the “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence in Dumbo and the DTs vision of the protagonist of Wilder’s The Lost Weekend. As the title suggests, Altered States takes such mental activities as its subject matter and has many scenes that represent them.

A harder case is voiceover. Are all cases of voiceover subjective? Clearly not. If we have a situation where a character tells a story to a group and his or her voice continues over a flashback, the narration remains objective. We assume that the group can still hear the storyteller. Cases where the voice exists only in the mind, as when a character speaks to himself or herself, but not aloud, are mental subjectivity.

That said, there are many unclear cases. Just what is the status of the narration in Jerry Maguire? Jerry seems to speak directly to us, pointing out things that happen during the action, yet clearly there is no suggestion that he made the film we are watching. The problem is compounded in Sunset Boulevard, where the protagonist not only implicitly addresses us but is also dead. In many cases when a character’s voice is heard over a scene, it might occur to audience members to wonder where the character is or was when speaking these words. And does a character’s voice describing his or her feelings constitute objective or subjective narration? Probably we would want to say that only when the voice is posited as strictly an internal voice, audible only to the character, would we want to dub it subjective.

The problem with voiceovers arises, I think, because it’s such a slippery technique to begin with, and therefore often hard to categorize. Is a character speaking narration over events that happened in the past diegetic sound or nondiegetic? If there’s never an establishment of where and when that character does the narrating, he or she exists in a sort of limbo in between the two states: diegetic because he or she is a character, nondiegetic because he or she is in some ineffable way removed from the story world.

For voiceovers, then, I think it’s best simply to categorize the ones that obviously are straightforwardly objective or subjective. In tricky cases, we just have to admit that not all uses of film technique are easy to pin labels on. But the point of having categories like these isn’t to pin labels. In part knowing them allows us simply to notice things in films that might otherwise remain a part of an undifferentiated flow of images. They enable us to see underlying principles that make films into dynamic systems rather than collections of techniques. They give us ways to organize our thoughts about films and convey them to others. And, though students may doubt this, watching for such things becomes automatic and effortless once we have understood such categories and watched a lot of films. As a child, I don’t think I knew about the concept of editing or ever really noticed cuts. Now I’m aware of every cut in every film I see, and I notice continuity errors and graphic matches and other related techniques, all automatically, without that awareness impinging in the least on my following the story and being entertained. Learning the categories is only the beginning.

Playing with subjectivity

Once students have seen some clear cases of each type of cinematic subjectivity and understand the difference, the teacher could move on to emphasize that filmmakers can play with both in original ways. It’s not really possible in an introductory textbook to discuss all the possibilities—and probably not possible to come up with a typology that would cover every example of subjectivity that could exist across that continuum we mentioned. Imaginative filmmakers will always find new variants on how to use techniques for this purpose. But here are a few intriguing cases.

In his class, Chris shows the scene in Hannah and Her Sisters where the Woody Allen character, a hypochondriac, visits a doctor for some hearing tests. Initially the doctor comes into the room and gives a dire diagnosis of inoperable cancer. After Mickey has reacted to that, a cut takes us back to an identical shot of the doctor entering, but this time he gives Mickey a clean bill of health. The first part of the scene is retroactively revealed to have been a mental event, Mickey’s pessimistic fantasy.

The same sort of thing happens in a more extended way with the familiar “it was only a dream” revelations that make the audience realize that a major part of the plot has been subjective. In a more sophisticated way, as Chris points out, other sorts of mental subjectivity, usually lies or extended fantasies, can be revealed retrospectively, as in The Usual Suspects, Mulholland Drive, and Fight Club.

A flashback from one character’s viewpoint may reveal something new about an earlier scene. In Ford’s The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, the shootout is initially shown through objective narration. Only later in the plot does another character reveals that, unbeknownst to us or the other people present, he had also been present at the shootout. The flashback to his account reveals that the shootout happened very differently from the way we had assumed when first seeing it.

I’ll close with an example from The Silence of the Lambs. This shows how subtle and effective a play with perceptual and mental narration can be. In the scene at the funeral home where a recently discovered body of a murder victim is to be examined, Clarice is left waiting in the midst of a group of state troopers who stare at her. To get out of the situation, she turns and looks into the chapel, where a funeral is taking place. We see her face and then her POV as she surveys the room. A cut shows Clarice suddenly within the chapel, moving forward toward the camera and staring straight into the lens. We will only realize retrospectively that this image begins a fantasy that leads quickly into a memory. Clarice has not actually left her previous position just outside the door.

The next shot is a track forward through the center aisle toward the casket. Since Clarice had been walking in that direction before the cut, we recognize this as a POV and assume that Clarice is continuing to walk. Yet the man in the casket, as we soon will learn, is Clarice’s father. The shot represents a different funeral, one in the past which she has been triggered to remember by her glance into the chapel. The fantasy has become a flashback. A second, similar view of Clarice’s face returns us to her fantasizing adult self, the one remembering this scene but not the one still standing outside the door. A closer view of the father’s casket shows it from a lower vantage-point, as if that of a child.

The reason for the change becomes apparent from a radical change at the next cut, so that the camera is on the far side of the casket, filming from a low angle. The sudden shift moves us away from the adult Clarice in order to show her as a child approaching her father and leaning down to kiss him. A noise pulls Clarice out of her memory, and a cut back to the hallway shows her turning away from the chapel. (As often happens, sound, and particularly music, helps guide us through the scene, marking the beginning and ending of the fantasy/flashback.)

The most experienced film specialist could not track all the rapidly shifting levels of subjectivity in this scene on first viewing. Still, later analysis using some categories of subjective narration can help us appreciate how Demme has woven them into a scene that helps explain Clarice’s motives in becoming an FBI agent and her determination in pursuing her first case.

Categories matter

To some students, the categories I’ve just discussed may seem like trivial distinctions. They’re not. The use of subjective narration is one of the key ways the filmmaker has to engage our thoughts and emotions with the characters. In Psycho, we become involved in Marion Crane’s life in a remarkably short time, partly because of her situation but also partly because Hitchcock keeps us so close to her once she prepares to steal the money. The camera not only frames her closely, but to a considerable degree we see and imagine what she does: her fearful forebodings of how her rash act will turn out. Much the same thing happens with Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs, though there our emotional involvement lasts throughout the film, and we are given glimpses of Clarice’s memories.

Perhaps choosing a scene or two from such films and going through them with the students, trying to imagine what it would be like without the POV shots and the imaginings and the memories, would convince them of the value of learning these categories. After all, the exceptions they find are only exceptional because they play in a zone defined by solid concepts.

[Note added October 24: I should have referred back as well to David’s entry “Three Nights of a Dreamer,” largely on POV.]

Objective

Superheroes for sale

DB here:

After a day at the movies, maybe I am living in a parallel universe. I go to see two films praised by people whose tastes I respect. I find myself bored and depressed. I’m also asking questions.

Over the twenty years since Batman (1989), and especially in the last decade or so, some tentpole pictures, and many movies at lower budget levels, have featured superheroes from the Golden and Silver age of comic books. By my count, since 2002, there have been between three and seven comic-book superhero movies released every year. (I’m not counting other movies derived from comic books or characters, like Richie Rich or Ghost World.)

Until quite recently, superheroes haven’t been the biggest money-spinners. Only eleven of the top 100 films on Box Office Mojo’s current worldwide-grosser list are derived from comics, and none ranks in the top ten titles. But things are changing. For nearly every year since 2000, at least one title has made it into the list of top twenty worldwide grossers. For most years two titles have cracked this list, and in 2007 there were three. This year three films have already arrived in the global top twenty: The Dark Knight, Iron Man, and The Incredible Hulk (four, if you count Wanted as a superhero movie).

This 2008 successes have vindicated Marvel’s long-term strategy to invest directly in movies and have spurred Warners to slate more comic-book titles. David S. Cohen analyses this new market here. So we are clearly in the midst of a Trend. My trip to the multiplex got me asking: What has enabled superhero comic-book movies to blast into a central spot in today’s blockbuster economy?

Enter the comic-book guys

It’s clearly not due to a boom in comic-book reading. Superhero books have not commanded a wide audience for a long time. Statistics on comic-book readership are closely guarded, but the expert commentator John Jackson Miller reports that back in 1959, at least 26 million comic books were sold every month. In the highest month of 2006, comic shops ordered, by Miller’s estimate, about 8 million books (and this total includes not only periodical comics but graphic novels, independent comics, and non-superhero titles). There have been upticks and downturns over the decades, but the overall pattern is a steep slump.

Try to buy an old-fashioned comic book, with staples and floppy covers, and you’ll have to look hard. You can get albums and graphic novels at the chain stores like Borders, but not the monthly periodicals. For those you have to go to a comics shop, and Hank Luttrell, one of my local purveyors of comics, estimates there aren’t more than 1000 of them in the U. S.

Moreover, there’s still a stigma attached to reading superhero comics. Even kitsch novels have long had a slightly higher cultural standing than comic books. Admitting you had read The Devil Wears Prada would be less embarrassing than admitting you read Daredevil.

For such reasons and others, the audience for superhero comics is far smaller than the audience for superhero movies. The movies seem to float pretty free of their origins; you can imagine a young Spider-Man fan who loved the series but never knew the books. What’s going on?

Men in tights, and iron pants

The films that disappointed me on that moviegoing day were Iron Man and The Dark Knight. The first seemed to me an ordinary comic-book movie endowed with verve by Robert Downey Jr.’s performance. While he’s thought of as a versatile actor, Downey also has a star persona—the guy who’s wound a few turns too tight, putting up a good front with rapid-fire patter (see Home for the Holidays, Wonder Boys, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Zodiac). Downey’s cynical chatterbox makes Iron Man watchable. When he’s not onscreen we get excelsior.

Christopher Nolan showed himself a clever director in Memento and a promising one in The Prestige. So how did he manage to make The Dark Knight such a portentously hollow movie? Apart from enjoying seeing Hong Kong in Imax, I was struck by the repetition of gimmicky situations–disguises, hostage-taking, ticking bombs, characters dangling over a skyscraper abyss, who’s dead really once and for all? The fights and chases were as unintelligible as most such sequences are nowadays, and the usual roaming-camera formulas were applied without much variety. Shoot lots of singles, track slowly in on everybody who’s speaking, spin a circle around characters now and then, and transition to a new scene with a quick airborne shot of a cityscape. Like Jim Emerson, I thought that everything hurtled along at the same aggressive pace. If I want an arch-criminal caper aiming for shock, emotional distress, and political comment, I’ll take Benny Chan’s New Police Story.

Then there are the mouths. This is a movie about mouths. I couldn’t stop staring at them. Given Batman’s cowl and his husky whisper, you practically have to lip-read his lines. Harvey Dent’s vagrant facial parts are especially engaging around the jaws, and of course the Joker’s double rictus dominates his face. Gradually I found Maggie Gyllenhaal’s spoonbill lips starting to look peculiar.

The expository scenes were played with a somber knowingness I found stifling. Quoting lame dialogue is one of the handiest weapons in a critic’s arsenal and I usually don’t resort to it; many very good movies are weak on this front. Still, I can’t resist feeling that some weighty lines were doing duty for extended dramatic development, trying to convince me that enormous issues were churning underneath all the heists, fights, and chases. Know your limits, Master Wayne. Or: Some men just want to watch the world burn. Or: In their last moments people show you who they really are. Or: The night is darkest before the dawn.

I want to ask: Why so serious?

Odds are you think better of Iron Man and The Dark Knight than I do. That debate will go on for years. My purpose here is to explore a historical question: Why comic-book superhero movies now?

Z as in Zeitgeist

More superhero movies after 2002, you say? Obviously 9/11 so traumatized us that we feel a yearning for superheroes to protect us. Our old friend the zeitgeist furnishes an explanation. Every popular movie can be read as taking the pulse of the public mood or the national unconscious.

I’ve argued against zeitgeist readings in Poetics of Cinema, so I’ll just mention some problems with them:

*A zeitgeist is hard to pin down. There’s no reason to think that the millions of people who go to the movies share the same values, attitudes, moods, or opinions. In fact, all the measures we have of these things show that people differ greatly along all these dimensions. I suspect that the main reason we think there’s a zeitgeist is that we can find it in popular culture. But we would need to find it independently, in our everyday lives, to show that popular culture reflects it.

*So many different movies are popular at any moment that we’d have to posit a pretty fragmented national psyche. Right now, it seems, we affirm heroic achievement (Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Kung Fu Panda, Prince Caspian) except when we don’t (Get Smart, The Dark Knight). So maybe the zeitgeist is somehow split? That leads to vacuity, since that answer can accommodate an indefinitely large number of movies. (We’d have to add fractions of our psyche that are solicited by Sex and the City and Horton Hears a Who!)

*The movie audience isn’t a good cross-section of the general public. The demographic profile tilts very young and moderately affluent. Movies are largely a middle-class teenage and twentysomething form. When a producer says her movie is trying to catch the zeitgeist, she’s not tracking retired guys in Arizona wearing white belts; she’s thinking mostly of the tastes of kids in baseball caps and draggy jeans.

* Just because a movie is popular doesn’t mean that people have found the same meanings in it that critics do. Interpretation is a matter of constructing meaning out of what a movie puts before us, not finding the buried treasure, and there’s no guarantee that the critic’s construal conforms to any audience member’s.

*Critics tend to think that if a movie is popular, it reflects the populace. But a ticket is not a vote for the movie’s values. I may like or dislike it, and I may do either for reasons that have nothing to do with its projection of my hidden anxieties.

*Many Hollywood films are popular abroad, in nations presumably possessing a different zeitgeist or national unconscious. How can that work? Or do audiences on different continents share the same zeitgeist?

Wait, somebody will reply, The Dark Knight is a special case! Nolan and his collaborators have strewn the film with references to post-9/11 policies about torture and surveillance. What, though, is the film saying about those policies? The blogosphere is already ablaze with discussions of whether the film supports or criticizes Bush’s White House. And the Editorial Board of the good, gray Times has noticed:

It does not take a lot of imagination to see the new Batman movie that is setting box office records, The Dark Knight, as something of a commentary on the war on terror.

You said it! Takes no imagination at all. But what is the commentary? The Board decides that the water is murky, that some elements of the movie line up on one side, some on the other. The result: “Societies get the heroes they deserve,” which is virtually a line from the movie.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). That’s the bait the Times writers took.

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Back to basics

If the zeitgeist doesn’t explain the flourishing of the superhero movie in the last few years, what does? I offer some suggestions. They’re based on my hunch that the genre has brought together several trends in contemporary Hollywood film. These trends, which can commingle, were around before 2000, but they seem to be developing in a way that has created a niche for the superhero film.

The changing hierarchy of genres. Not all genres are created equal, and they rise or fall in status. As the Western and the musical fell in the 1970s, the urban crime film, horror, and science-fiction rose. For a long time, it would be unthinkable for an A-list director to do a horror or science-fiction movie, but that changed after Polanski, Kubrick, Ridley Scott, et al. gave those genres a fresh luster just by their participation. More recently, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It, the fantasy film arrived as a respectable genre, as measured by box-office receipts, critical respect, and awards. It seems that the sword-and-sorcery movie reached its full rehabilitation when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King scored its eleven Academy Awards.

The comic-book movie has had a longer slog from the B- and sub-B-regions. Superman, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy were all fodder for serials and low-budget fare. Prince Valiant (1954) was the only comics-derived movie of any standing in the 1950s, as I recall, and you can argue that it fitted into a cycle of widescreen costume pictures. (Though it looks like a pretty camp undertaking today.) Much later came revivals of the two most popular superheroes, Superman (1978) and Batman (1989).