Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Games cinephiles play

From DB:

The Europeans have long been fascinated by the subject of cinephilia. The French supplied not only the word but the most outstanding instances, from the founding of Cahiers du cinéma to the passions of the Nouvelle Vague. (1) In the last decade particularly, French critics have often returned to the subject–worrying, for instance, that home video might have changed or even decimated cinephilia–and this has led critics from other countries to join in.

I was reminded of how strongly the idea persists when, at Il Cinema Ritrovato this year, I was invited to sit in on one of several lunches at which critics and historians talked about the subject. The discussion consisted mostly of recollections of the guests’ first encounters with cinema, of the films that affected them most powerfully, of the film-related activities they engaged in during their salad days. Some of us hadn’t done this exercise in autobiography before, but others had had practice. Jonathan Rosenbaum and Eric de Kuyper had both written a fair amount about the sources of their affinity for film. (Sometimes I feel I remember Jonathan’s life better than my own.)

What is cinephilia? Literally, the love of film. But everybody likes, even loves film, no? The term “cinephilia” connotes an overwhelming passion for film, even an obsession about it. And not just particular films. I meet civilians all the time who are devoted to their favorites—The Godfather, The Princess Bride, The Matrix. But they’re not cinephiles. So is it just a matter of quantity? Is it just that the cinephile enjoys a great many movies? Partly, but there’s still more to it.

The cinephile displays symptoms of cinemania, as chronicled in the film of the same name. If you haven’t seen it, Cinemania tracks five people who organize their lives around watching movies. As I watched it, some of my reactions ran to “Wow, that is really hard-core,” but every now and then I thought: “Well, that‘s not so weird. I do that.” So I see the similarities.

Most obviously, both the cinephile and the cinemaniac show symptoms of compulsiveness. Each one makes lists, checks off titles seen, plans a day of moviegoing with care. When visiting a new city, s/he first scans the cultural scene for what’s playing. Both types of film lover are strict—no pan-and-scan, no colorization, no dodgy projection. Either type might have a weblog or a diary or just patient friends. If s/he has friends.

But I do see differences. For one thing, most cinemaniacs like only certain sorts of movies—usually American, often silent, sometimes foreign, seldom documentaries. Do cinemaniacs line up for Brakhage or Frederick Wiseman? My sense is not.

Cinephiles by contrast tend to be ecumenical. Indeed, many take pride in the intergalactic breadth of their tastes. Look at any smart critic’s ten-best lists. You’ll usually see an eclectic mix of arthouse, pop, and experimental, including one or two titles you have never heard of. Obscurity is important; a cinephile is a connoisseur.

The real crux, I think, is this. The cinephile loves the idea of film.

That means loving not only its accomplishments but its potential, its promise and prospects. It’s as if individual films, delectable and overpowering as they can be, are but glimpses of something far grander. That distant horizon, impossible to describe fully, is Cinema, and it is this art form, or medium, that is the ultimate object of devotion. In the darkening auditorium there ignites the hope of another view of that mysterious realm. The pious will call Cinema a holy place, the secular will see it as the treasure-house of an artform still capable of great things. The promised land of cinema, as experimentalists of the 1920s called it: that, mystical as it sounds, is my sense of what the cinephile yearns for.

This separates the cinephile from the lover of novels or classical music. They love their art, I suspect, because of its great accomplishments. Who with literary or musical taste would embrace the subpar novel or the apprentice toccata? But cinephiles will watch damn near anything looking for a moment’s worth of magic. Perhaps this puts cinephiles closer to theatre buffs. They too wait hopefully for the sublime instant that flickers out of amateur performances of Our Town and Man and Superman.

That’s also why I think that the cinephile finds the desert-island question so hard to answer. What movies would I want to live with for the rest of my life? All of them, especially the ones I haven’t yet seen.

Another difference: Fussiness and solitude. The cinemaniac has a favorite seat, even if it’s way off to the side. To secure it, the cinemaniac shows up early and tries to be first in line. Your average cinephile isn’t so picky about where to sit, and so may slip in at the last minute. While waiting for the show to start, the cinemaniac seldom acknowledges others; a book is the faithful companion. But the cinephile is, if not extroverted, at least gregarious and wants to talk with other cinephiles.

What sort of talk? I’m glad you asked.

Cooperative games: Playing well with others

Jules and Jim leave a screening.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: Yeah, great!

Jules: Well, see ya.

Jim: Yup, later.

This is the minimal, polite cooperative game. When the energy level is cranked up, you get something like this.

Jules: Great movie! I love M*x *ph*ls.

Jim: God, yes. Those camera movements knock me out.

Jules: But then there’s R*n**r too!

Jim: God, I love R*n**r. And M*z*g*ch*–there’s a man for camera movements.

Jules: My man! M*z*g*ch* is just terrific.

This can go on indefinitely. To get a sense of how special cinephiliac enthusiasms are, imagine littérateurs talking about Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, and iambic pentameter in these terms.

A cooperative game can go a little further.

Jules: What a fantastic movie!

Jim: Yes, fabulous. M*nn*ll* movies get better and better, the more you see them.

Jules: I completely agree—except for The S*ndp*p*r.

Jim: Yeah, that’s kind of weak, but it’s got some good points.

Jules: Really? I haven’t seen it in twenty years.

Jim: I have a pretty good copy off Turner. Let me dub it and send it to you.

Jules: That’s really nice of you.

Even if Jim never sends the disc, he has played the game charitably and Jules has accepted graciously.

Jim: What a terrific movie.

Jules: I wasn’t so impressed. Want to grab a coffee and talk about it?

Jim: Good idea!

This is probably the optimal way to play Cinephilia cooperatively.

But many cinephiles want to play rougher. The extreme option is flat-out disagreement, usually expressed in terms that bluntly doubt the competitor’s sanity, intelligence, or good will. I won’t dwell on this abrasive strategy here. There are stealthier ways to go.

Competitive games: Upsmanship

Jules and Jim leave a screening.

Jules: I loved it. What did you think?

Jim: Well. . . Have you seen earlier films by H*ng S*ng-s**?

This is an opening gambit. If Jules says no, then Jim can say something like: It’s really one of his weaker movies or His films get worse and worse. Now Jules would be playing defense, on unfriendly terrain. If he hasn’t seen the other films, the comparison-strategy will be his undoing. So:

Jules: Yeah, I’ve seen all of them. I thought that this was a strong one.

Now Jim can fight to at least a draw. Maybe Jules was bluffing and hasn’t seen all the films; or maybe Jim remembers them better.

Jules has used what we can call the breadth strategy: I’ve seen more than you. This need not bear only on other films; it can work along other dimensions.

Jim: I was so impressed by St*g* Fr*ght, but I never heard anybody refer to it among H*tch’s best.

Jules: Well, in the critical literature it’s often considered a masterpiece. Have you read . . .?

Or:

Jules: Yes, it’s a great movie, but what a terrible print! The reel ends were chopped off, and there were splices all the way through. I remember seeing a pristine print at the Director’s Guild Theatre. [The haymaker:] Jane Wyman was there to talk about it.

With a silent film you can extend the strategy to multiple versions: I remember a MoMA screening that ran an extra half-hour or The DVD from Austria fills in the missing scenes with stills. Oh, you didn’t know there were missing scenes…? Jim doesn’t have many options here.

If Jules sticks to the breadth strategy, this can go on quite a while. Once I got cornered after a friendly critic asked me about 1930s Ozu. Yes, I’d seen them all. Naruse? Yes. Shimizu? Quite a lot. I held my own, but then he changed up his pitching rhythm: “And how about 1930s English comedies? No? Oh, you must see them—they’re wonderful.”

Akin to the breadth approach is the longevity strategy, aka I was here first. We old guys like to use this. It can get pretty brutal.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: First time you saw it?

Jules: Um, yeah.

Jim: It gets better on multiple viewings. I liked it when I saw it in 1971. In fact, I liked it so much I wrote about it for Sight & Sound. Let me send you a copy of the essay.

Jules: Um…thanks…

There’s also the depth strategy. Here the player goes very specific, invoking details that suggest sensitivity and massive memory power.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: You said it. I especially liked the scene when the camera tracks sideways, picking up the back of the guy who’ll turn out to be so important at the end.

Jules: Yeah. . . Actually, I didn’t notice that.

Jim: You didn’t? Gosh, that’s the key to the whole movie. It sets up the last scene beautifully. Of course there’s also that killer opening line.

Jules (who doesn’t even remember the opening scene): Yeah, that was really effective.

Jules lost, and Jim knows it.

Another strategy relies on eloquence. Both Jules and Jim are evenly matched on range and depth and longevity, but Jules has the edge in using language.

Jules: What’d you think?

Jim: I liked the opening shot.

Jules: Me too. Most long-take crane shots look pretentious, but this one had a sinuous grace that’s hard to achieve on location.

This strategy can be amped up into philosophical disquisition that usually sounds better in French but can occur in English too.

Jim: I just don’t see why people take W**dy *ll*n seriously. Cr*m*s *nd M*sd*m**n*rs is heavy-handed in its metaphors of blindness and sight.

Jules: What’s remarkable about W**dy is the way his metaphors hover between the banal and the extraordinary. They’re at once familiar and unfamiliar, both distant and near. They lie, we might say, in a zone of zigzag indeterminacy.

Okay, this plays better on the page than in conversation, but I have encountered it occasionally face to face. It’s a hard serve to return. Resorting to I just don’t know what that means usually makes you look dumb, whereas Do you buy effluvia like that in ten-gallon drums? would be considered hostile.

Then there’s the insider strategy.

Jules: Solid movie, but a little choppy.

Jim: Yeah, the director sent me a rough cut on DVD a few months ago. Looks like she dropped a lot. And the producer’s son attempted suicide, which probably screwed up the whole project.

Advantage: Jim.

What we talk about when we talk about talk

I’ve taken face-to-face dialogue as my default, but you can find these strategies at play in those monologues we call film criticism. The maneuvers are usually a bit subtler, though. For instance, the longevity strategy often surfaces guilelessly, as a homey touch of autobiography. Some critics like to start their pieces with a chatty narrative recounting how they learned about this film—that is, way before you, loser.

And of course these strategies are all over forums and chat threads. In those settings the players can be anonymous and can loose a barrage that they might hesitate to launch in person.

One last question: Are these games for boys only? Is cinephilia itself defined as a guy’s thing? In my experience, no, not wholly; but mostly. Have women opted out? Do they play it differently? I might have to recast my dialogues in order to include Catherine.

In any case: Substantively speaking, this is a minuet. Jules’ claims might be right or wrong. Ditto Jim’s. Any of the competitive strategies can produce information and ideas. We just have to remember that lots of life is about playing games.

And remember that you can always change the subject to sports or rock and roll. No one-upsmanship in those domains!

(1) Antoine de Baecque’s entertaining La cinéphilie: Invention d’un regard, histoire d’une culture 1944-1968 (Paris: Fayard, 2003) has become the standard history of this tendency.

B is for Bologna

A big crowd assembles for one of the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore.

Not laziness or old age (we hope) but sheer busyness has reduced our Bologna blogging to a single entry this year. Last year we managed three entries, but this time there was just so much to see, from nine AM to midnight, that we couldn’t drag ourselves away to the laptop. That it was blazing hot and surprisingly humid may have given us less biobloggability as well. Still, DB has many pictures, so maybe a followup blog with unusual images of critics and historians disporting in the sun….

Some backstory: Hosted by the Cineteca of Bologna, Il Cinema Ritrovato is an annual festival of rediscovered and restored films. Every July hundreds of movies are screened in several venues. For our 2007 report, with more background and some orienting pictures, go here and then here and here. Watch a lyrical trailer for the event here.

As before, both KT and DB contribute to this year’s entry. But first, the breaking story.

Freder and Maria, together again for the first time

While we were there, the news of a long version of Metropolis broke. The estimable David Hudson offers a quick guide and an abundance of links at GreenCine. A rumor went around Bologna that fragments of the new Buenos Aires print would be screened, but instead there was a twenty-minute briefing anchored by Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek. Along with him, Anke Wilkening (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Stiftung), Anna Bohn (Universitat der Kunste, Berlin), and Luciano Berriatua (Filmoteca Espanola) provided some key points of information.

*Provenance: The “director’s cut” was released in Argentina during the 1920s, with Spanish intertitles and inserts made at Ufa. A collector acquired a print. (Once more we have a collector to thank for saving film history.) When the Argentine film archive (Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken) received the copy in the 1960s, a 16mm dupe negative was made, and the nitrate original was discarded, a common practice at the time.

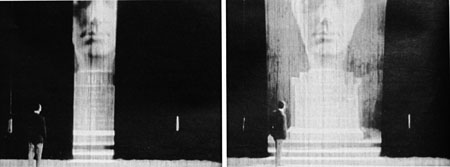

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Completeness: Contrary to some reports, virtually all the missing scenes are present on the Argentine print, the single exception being a small portion at a reel end. Among the new sequences are scenes filling in the roles of three characters (Georgy, Slim, and Josaphat), a car journey through the city, and moments of Freder’s delirium.

How can the researchers be confident that the print is so complete? It’s a fascinating story.

Metropolis has been reconstructed many times since the 1960s. In 2001, the Murnau foundation presented a digital restoration of the film supervised by Martin Koerber in collaboration with Enno Patalas. In this version, which is available on DVD (Transit Film, Kino International) about 30 minutes of the original material are missing. In 2003-2005 Enno Patalas and Anna Bohn together with a team at the University of the Arts in Berlin created a “Study Edition” version in which the missing footage was represented by bits of gray leader. For the first time the full length of the film was reconstructed with help from the the original music score.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

Bohm and Patalas’s comparative method proved itself valid: The Buenos Aires footage fitted the gaps in their study edition perfectly!

A viewing copy will not be forthcoming immediately, given the restoration task, but sooner or later we will have a good approximation of the fullest version of one of the half-dozen most famous silent movies. Getting news like this while among archive professionals is one of the unique pleasures of Cinema Ritrovato. (Special thanks to Dr. Bohn for clarification on several points and to enterprising film historian Casper Tybjerg, who helped me get a copy of the Die Zeit issue.)

Two Davids and a Kevin: Robinson, Brownlow, and Shepard at a critics’ lunch.

Powell meets Bluebeard and Bartók

KT: One of the high points of the week for me was Michael Powell’s 1964 film of Béla Bartók’s short opera Bluebeard’s Castle. It was made for German television and shown in Bologna as Herzog Blaubarts Burg. Unfortunately it was programmed opposite the screening of fragments from Kuleshov’s Gay Canary, but Powell’s post-Peeping Tom films are so difficult to see that I made the difficult choice and gave up hope of seeing the entire Kuleshov retrospective.

Despite being relatively recent in comparison with most of the films shown during the week, Herzog Blaubarts Burg is one of the most obscure. I felt it was an extremely rare privilege to see it, one which I will probably never have again, at least in so splendid a print.

The film belongs to the late period of Powell’s career, after the controversial Peeping Tom had made it impossible for him to work within the mainstream film industry. It was produced by Norman Foster—though not the Norman Foster who directed Journey into Fear and several of the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto films. This Norman Foster was an opera singer whose stage career was cut short by a dispute with Herbert von Karajan. His widow, Sybille Nabel-Foster, explained this and described how Foster produced and starred in two television adaptations, Herzog Blaubarts Burg and Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1966). Foster had originally approached Ingmar Bergman to direct the former, but when that proved impossible, Powell stepped in—and probably a good thing, too. It was definitely his kind of project.

The two performers are perfect for their roles. Foster plays Bluebeard brilliantly, having both a powerful bass voice and the necessary combination of handsomeness and a sense of threat. His co-star, the excellent soprano Ana Raquel Satre, recalls the pale beauties of some of Powell’s earlier films (Kathleen Byron as the increasingly mad Sister Ruth in Black Narcissus, Pamela Brown in I Know Where I’m Going!, and particularly Ludmilla Tcherina in The Tales of Hoffman), but she also bears a resemblance—perhaps deliberately enhanced through costuming and make-up—to Barbara Steele and other horror-film heroines of the 1960s.

The film was shot cheaply in a Salzburg studio, using garish, modernist settings against black backgrounds. These create a labyrinthine, floating space that avoids seeming stage-bound. (Hein Heckroth, the production designer, had previously worked on several Powell films, including The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffman.) I was reminded of Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982), which looks somewhat less original in the light of Powell’s film.

As Nabel-Foster explained, after its initial screening on German television, Herzog Blaubarts Burg has been shown seldom because of rights complications with the Bartók estate. Non-commercial screenings have occurred on public television in the U.S. and Australia, but basically the film is off-limits until the copyright expires in 2015, seventy years after the composer’s death. Nabel-Foster has been providently preparing for a DVD release, gathering the original materials.

The print shown was a privately held Technicolor original from the era, in nearly mint condition. (The British Film Institute has a print as well.) The sparse subtitles written by Powell himself were added for this screening.

I’m not convinced that the film is quite the masterpiece that some claim, but it is a major item in Powell’s oeuvre nonetheless, and I felt privileged to have seen it in ideal conditions.

[July 12: Kent Jones, a great admirer of Powell and Bluebeard’s Castle, tells me that he programmed it at the Walter Reade in New York for a centenary retrospective of the director’s work in 2005. Foster’s widow introduced that screening as well.]

Janet Bergstrom and Cecilia Cenciarelli summarize their research on von Sternberg’s lost film The Sea Gull.

1908 and all that

KT: There were several programs of silent shorts, which I could only sample, as they tended to play opposite the Kuleshov films. As usual, the Bologna program included selections of short films from 100 years ago, so we were treated to numerous films from 1908. I was particularly pleased to see The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers, directed by Lewin Fitzhamon, who had made Rescued by Rover two years earlier. That film had been so fabulously successful that it had actually been shot three times as the negatives wore out from the striking of huge numbers of release prints.

The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers at first appears to be a sort of sequel (as it is described in the program), since it stars the same dog (Blair) who had played Rover, and again there is a kidnapped baby. It’s not really a sequel, though, since Cecil Hepworth, who had played the father in the earlier film, here appears as the kidnapper, and the dog is not named Rover. The new film is more fantastical than the original, since the dog races after the car in which the child is abducted and rather than fetching its master, effects the rescue itself by driving the car back home when the villain leaves his victim unattended!

Other 1908 films I particularly enjoyed: In Pathé’s Le crocodile cambrioleur, a thief hides inside a huge fake crocodile and crawls away, creating fear wherever he goes. The Acrobatic Fly by British director Percy Smith, provides a very close-up view of an apparently real fly juggling various small objects. (How was it done? It’s a mystery to me.)

Another retrospective series was “Irresistible forces: Comic Actresses and Suffragettes (1910-1915).” The suffragette films were rather depressing, despite the fact that many were meant at the time to be comic and amusing. Mostly the joke was how masculine these determined women were, a self-verifying proposition when the filmmakers often chose to have the suffragettes played by men. My favorite program was one involving early French female comics. I’ve long been fond of Gaumont’s Rosalie series since seeing a few at an early-cinema conference in Perpignon, France back in 1984. Rosalie, a chubby, cheerful little dynamo played by Sarah Duhamel, was highly entertaining in three films in the “France—Rosalie, Cunégonde et les autres…” program.

As Mariann Lewinsky, who devises these annual series, pointed out, Duhamel is the only early female French comic whose name we know. Léotine, represented here in Rosalie and Léotine vont au théâtre, is played by an anonymous actress. I had not encountered Cunégonde, also anonymous, before, but she proved to be quite amusing as well. I particularly liked Cunégonde femme du monde, where she plays a maid who dresses up as a society lady when her employers go off on a trip; the carefully constructed story and twist ending are impressive for such an apparently minor one-reeler.

It was a treat to see a succession of gorgeous prints of von Sternberg’s films. I particularly enjoyed seeing Thunderbolt (1929) again after many years. Back in 1983 I taught a survey film history course in which I used the director’s first talkie as my example of the transition to sound. Not a good example, I must admit, since Thunderbolt is completely atypical, with its highly imaginative use of offscreen sound. The second half, set primarily in a prison block, involves shouts from unseen cells and a small band that breaks into songs, often completely out of tone with the action, at unexpected moments. Eisenstein and the other Soviet directors would have thoroughly approved of its sound counterpoint. I have to admit that I prefer von Sternberg’s George Bancroft films (Underworld, Docks of New York, and Thunderbolt) to the Dietrich ones. Not only are the plots simpler and more elegant, but they contain a genuine element of emotion that is not, as in the Dietrich series, frequently undercut by irony.

I didn’t make it to many of the CinemaScope films playing on the very big screen in the Cinema Arlecchino theater, but I did enjoy two westerns. Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958) and John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1954) both looked terrific and were highly popular with everyone we talked to. The latter was particularly a revelation, since in contrast to the Mann, it hasn’t had much of a reputation among cinephiles.

A Rodchenko angle for Yuri Tsivian.

Teacher and experimenter

DB: As Kristin mentioned, we missed a lot of the “Hundred Years Ago” series—a pity, since 1908 is a miraculous year—in order to keep up with one of our favorite directors, Lev Kuleshov.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common to say that Eisenstein and Vertov were the most experimental Soviet directors, while the others were more conventional. Then we realized that in films like Arsenal (1928), Dovzhenko had his own wild ways. Then we discovered the Feks team, Kozintsev and Trauberg, and the bold montage of The New Babylon (1929). A closer look at Pudovkin, particularly his early sound films like A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933), revealed that he too was no timid soul when it came to daring cutting and image/ sound juxtapositions. But surely their mentor Kuleshov, admirer of Hollywood continuity and proponent of the simplest sorts of constructive editing, played things safe?

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

My admiration for Kuleshov, confessed in an earlier blog entry, already led me to spot some weirdnesses in Mr. K’s official classics. The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) boasts some very un-formulaic cutting in certain passages (including an upside-down shot when cowboy Jeddy ropes the sleigh driver), and By the Law (1926) makes chilling use of discontinuities when the scarecrow Hohlova holds the Irishman at gunpoint. But thanks to the retrospective we can confidently say that Kuleshov was no less venturesome, at least in certain projects, than his pupils.

Soviet specialists already suspected that The Great Consoler (1933) was K’s sound masterpiece, and another viewing confirmed it. It incorporates three registers. William S. Porter, in prison but serving in the pharmacy, witnesses brutality and oppression and is driven to drink. Under the name O. Henry he writes cheerfully sentimental tales as much to console himself as to charm readers. His stories are in turn consumed by shopgirls like Dulcie, a romantic who may not realize how unhappy she is. Kuleshov adds a level of sheer fantasy, represented by a pastiche silent film dramatizing O. Henry’s “A Retrieved Reformation,” in which a safecracker trying to go straight reveals his identity by saving a girl trapped in a bank vault. The embedded story features characters from the other two levels, convict Jimmy Valentine and Dulcie’s lover, a vaguely sadistic businessman in a ten-gallon hat.

The Great Consoler reminds us of the popularity of O. Henry in the Soviet Union, both among readers and the Russian Formalist literary theorists, who were fascinated by his flagrant, playful artifice. (Boris Eikhenbaum’s essay on the writer is one of the most brilliant pieces of literary analysis I know.) Even though Kuleshov must denounce Porter for reconciling the masses to their misery under capitalism, the zest of the embedded film and the unique architecture of the overall project pay tribute to another entertainer who did not forgo experimentation. And Kuleshov’s image of a writer in prison probably had Aesopian significance for artists in the era of Socialist Realism.

K’s other major sound experiment, less widely seen, is Gorizont (1932). The title is at once a man’s name and the Russian word for “horizon”—a metaphor literalized in the final shot of a train leaving a tunnel. As Yuri pointed out, it is one of the few Soviet films centered on a Jew, and so the formulaic growth-to-consciousness plotline takes on a new resonance in the light of Slavic anti-semitism. Lev Gorizont is an amiable, somewhat thick young man who dreams of emigrating to the US to make his fortune. But in New York he finds only poverty and disillusionment, eventually returning home to help make a better society. Famous for its use of sound, Gorizont contains a passage of imaginative “counterpoint.” Both Lev and his friend Smith have been jilted by the social-climber Rosie. As they talk, we hear warm piano music, but not until the end of the scene does Smith speculate that probably Rosie is somewhere listening to Chopin. The music has retrospectively functioned somewhat like crosscutting, suggesting that Rosie now lives among the wealthy.

Kuleshov, like Eisenstein, gained his fame for his ideas on editing and sound montage, but both men were deeply interested in performance. Kuleshov’s idea that the film actor should become an angular mannequin carries on the impulse of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and he anticipated CGI software in suggesting that human action could be plotted on a three-dimensional grid. Still, Kuleshov usually gives his figures a fluid dynamism that doesn’t seem mechanical. The three narrative registers of The Great Consoler are delineated largely through acting: naturalistic and slowly paced in the prison scenes, rigid and posed in the shopgirl romance, and broad and eccentric in the embedded silent movie.

Kuleshov’s performance theories popped out of other films in the series. What survives of The Gay Canary (1929) centers on a cabaret actress courted by lustful reactionaries during the civil war, and her scenes of fury, as she flings around flowers, vases, and pieces of furniture, come off as acrobatic rather than realistic. Naturally, the circus milieu of 2 Buldy 2 (1929) encourages stunts. A father and son, both clowns, are to perform together for the first time, but the civil war separates them, and the elder Buldy, tempted for a moment to acquiesce to the White forces, casts his lot with the revolution. At the climax Buldy Jr. escapes the Whites thanks to flashy trampoline and trapeze acrobatics; the gaping enemy soldiers forget to shoot. Even Kuleshov’s more naturalistic films show flashes of kinetic, stylized acting. A partisan listens to a boy while draping himself over a door. A Bolshevik official answers the phone by reaching across his chest, twisting his body so the unused arm can hike itself up, right-angled, to the chair.

The interaction of the body with props occurs with a special flair in Young Partisans. A Bolshevik partisan tells some children how a boy saved his life in a German-occupied town (This flashback was directed by Igor Savchenko and functions as a short film on its own.) Having learned their lesson, the kids gather in their schoolroom and under the teacher’s eye draw a map of the partisans’ camp. But when Nazi soldiers burst in, the teacher flips the blackboard over; now all we see is algebra.

A scene of Hitchcockian suspense ensues: Will the Germans turn over the blackboard and discover the map? The tension is enlivened by a grotesque moment, when one alcoholic soldier finds a jar holding a pickled frog and decides to drink the formaldehyde. “Draw a map—show me where the partisans are!” the officer demands. He flips the blackboard, and in a split-second we see a boy crouching behind it; the blackboard swings into place toward us, the map now erased. The boy ducks into his seat, brushing off chalk dust.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

One of the biggest surprises was news of Dokhunda (1936), an ethnographically based fiction set in Tazhikistan. Although the film is lost, Nikolai has reconstructed its plan, revealing that Kuleshov adopted a strange preproduction method. He prepared “living storyboards,” photos of the cast enacting the scenes. He then drew and scratched on them, creating busy, nervous backgrounds or changing the figures’ features and hair styles—Kuleshov as pre-Warhol scribbler, or a graffiti artist tagging his own images.

Nikolai has also finished a DVD edition of Prite that exemplifies what he calls hyperkino, a way of annotating and comparing a film’s images, texts, and supplementary materials for instant access. Another project involves the Yevgenii Bauer classic, The King of Paris (1917), which Kuleshov completed. We haven’t had the intertitles for this, however, but now Nikolai has discovered them, and they will go on the DVD version that is being completed. For more information on these projects and Dokhunda, go to hyperkino.net.

So Kuleshov stands revealed as more supple and ambitious than most of us once thought. Once more Bologna plays to its strengths—filling in gaps but also forcing us to rethink what we thought we knew.

The key issue: What the hell am I going to be seeing now? From left, Olaf Muller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, and KT.

So much else to report, so little time. Besides The King of Paris, there was a string of fine 1910s films. Raoul Walsh’s Pillars of Society (1916), while not a patch on his Regeneration of the previous year, offered a solid adaptation of Ibsen. The Dawn of a Tomorrow (1915), James Kirkwood’s Mary Pickford vehicle, seemed to me flat and talky, but others liked it. For me the outstanding item was Paul Garbagni’s In the Spring of Life (1912). Beautifully directed in the tableau style, with precise depth choreography and a stirring scene of a theatre consumed by fire, it starred three men who would become great directors very soon: Sjöström, Stiller, and Georg af Klercker.

Not to mention the von Sternbergs (I liked An American Tragedy much more on this outing), the Scope revivals (Man of the West, Ride Lonesome in a handsome digital restoration from Grover Crisp), my first viewing of Duvivier’s La Bandera (1935), the Monta Bell items (most notably the incessantly energetic Upstage from 1926), and on and on.

What can Gianluca Farinelli, Peter von Bagh, and Guy Borlée, along with their devoted staff members, do for an encore? Bravo! Now take a rest.

Standing Room Only for the rarely seen Children of Divorce (Sternberg/ Lloyd, 1927).

Times go by turns

Kristin here—

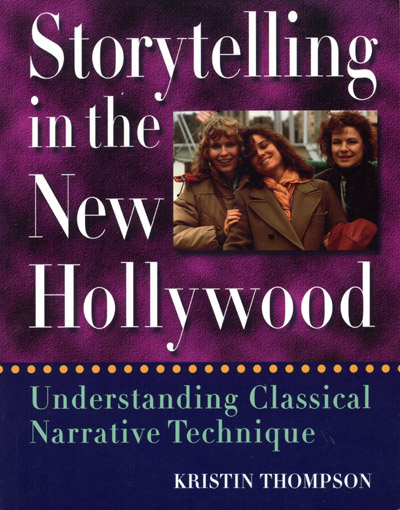

Last week during the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference here in Madison, I got to talking with Prof. Birger Langkjær of the University of Copenhagen. He asked me some questions about the concept of “turning points” in film narrative as I had used it in my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Specifically he wondered if turning points invariably involve changes of which the protagonist or protagonists are aware. The protagonist’s goals are usually what shape the plot, so can one have a turning point without him or her knowing about it?

I couldn’t really give a definitive answer on the spot, partly because it’s a complex subject and partly because I finished the book a decade ago (for publication in 1999). It seemed worth going back and trying to categorize the turning points in films I analyzed. Describing those turning points more specifically could be useful in itself, and it might help determine to what extent a protagonist’s knowledge of what causes those turning points typically forms a crucial component of them.

Characteristics of turning points

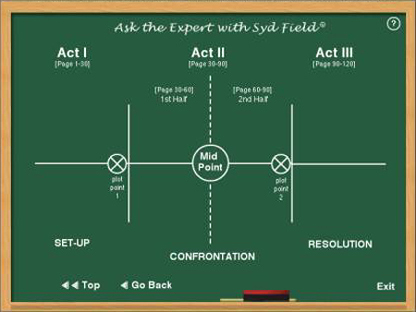

Most screenplay manuals treat turning points as the major events or changes that mark the end of an “act” of a movie. Syd Field, perhaps the most influential of all how-to manual authors, declared that all films, not just classical ones, have three acts. In a two-hour film, the first act will be about 30 minutes long, the second 60 minutes, and the third 30 minutes. The illustration at the top shows a graphic depiction of his model, which includes a midpoint, though Field doesn’t consider that midpoint to be a turning point.

I argued against this model in Storytelling, suggesting that upon analysis, most Hollywood films in fact have four large-scale parts of roughly equal length. The “three-act structure” has become so ingrained in thinking about film narratives that my claim is somewhat controversial. What has been overlooked is that I’m not claiming that all films have four acts. Rather, my claim is that in classical films large-scale parts tend to fall within the same average length range, roughly 25 to 35 minutes. If a film is two and a half hours rather than two hours, it will tend to have five parts, if three hours long, then six, and so on. And it’s not that I think films must have this structure. From observation, I think they usually do. Apparently filmmakers figured out early on, back in the mid-1910s when features were becoming standard, that the action should optimally run for at most about half an hour without some really major change occurring.

Field originally called these changes “plot points,” and he defined them as “an incident, or event, that hooks into the story and spins it around into another direction.” Perhaps because of that shift in direction, these moments have come more commonly to be called “turning points.” But what are they? Field’s definition is pretty vague.

In Storytelling I wrote, “I am assuming that the turning points almost invariably relate to the characters’ goals. A turning point may occur when a protagonist’s goal jells and he or she articulates it .… Or a turning point may come when one goal is achieved and another replaces it.” I also assumed that a major new premise often leads to a goal change (p. 29). “Almost invariably” because I don’t assume that there are hard and fast rules. As with large-scale parts, my claims about other classical narrative guidelines aren’t prescriptive in the way that screenplay manuals usually are.

To reiterate a few other things I said about turning points. They are not always the same as the moments of highest drama. Using Jaws as my example, I suggest that the moments of decision (not to hire Quint to kill the shark and later to hire him after all), rather than the big action scenes of the shark attacks, shape the causal chain (p. 33).

Not all turning points come exactly at the end of a large-scale part of the film (an “act” in most screenplay manuals). A turning point might come shortly before the end of a part, or the turning point may come at the beginning of the new part (pp. 29-30). The final turning point that leads into the climax comes when “all the premises regarding the goals and the lines of action have been introduced” (p. 29).

Most screenplay manuals consider goals to be static. To me, “Shifting or evolving goals are in fact the norm, at least in well-executed classical films” (p. 52). This doesn’t mean that the goal changes at every turning point. Instead, the end of a large-scale part may lead to a continuation of the goal(s) but with a distinct change of tactics (p. 28).

One big advantage of talking about different types of turning points is that it allows the analyst to see how the different large-scale parts function. A well-done classical film doesn’t just have exposition and a climax with a bunch of stuff in the middle. (Field calls that long second act the “Confrontation” in the diagram above.) I believe that once the setup is over, there is a stretch of “complicating action,” which often acts as a sort of second setup, creating a whole new situation that follows from the first turning point. The third part is the “development,” which often consists of a series of delays and obstacles that essentially function to keep the complications from continuing to pile up until the whole plot becomes too convoluted. The development also serves to keep the climax from starting too soon. The third turning point is the last major premise or piece of information that needs to be set in place before the action can start moving toward its resolution in the climax.

David uses this approach to large-scale parts in his online essay, “Anatomy of the Action Picture,” which discusses Mission: Impossible III.

TYPES OF TURNING POINTS

Returning to some of the examples I used in Storytelling, let’s see what sorts of changes their turning points involve. In most of these cases, the protagonist is aware of what is happening, but there are some exceptions or nuances.

1. An accomplishment, later to be reversed

Top Hat: end of setup, Jerry and Dale fall in love, but she soon conceives the mistaken idea that he is married to her best friend. (p. 28)

Tootsie: end of setup, Michael gets a job, but the results will throw his life increasingly into chaos. (p. 60)

Parenthood: end of complicating action, the parents seem to be making progress in solving their problems. (p. 268)

2. Apparent failure, reiteration of goal

The Miracle Worker: end of development, parents remove Helen from cabin, Anne states goal again. (p. 28)

The Silence of the Lambs: turning point comes at beginning of development, Chilton makes Lecter a counter-offer, removing him from the FBI’s charge. The FBI’s tactic has failed, but soon Clarice visits Lecter to pursue her questioning. (p. 123)

Here’s a case where we don’t see Clarice learning about Chilton’s treacherous undermining of the FBI’s efforts. A few scenes later she simply shows up to visit Lecter, and we realize that she has not given up her goal of getting information from him. Clearly a turning point can occur without the main character’s knowledge, but he or she will usually learn about it shortly thereafter.

Groundhog Day: end of development. Failure to save old man. No reiteration of goal, which is implicitly that Phil will continue to improve himself. (p. 147)

2a. Failure, new goal

Amadeus: end of complicating action, Salieri declares that he is now God’s enemy and will ruin Mozart. (p. 195)

Amadeus is an example of what I call a “parallel protagonist” film. Here Salieri is aware of his own decision, but Mozart never learns that his colleague hates him so. Parallel protagonists have separate goals, but they need not be aware of each other’s goals. The same would be true in a film with multiple protagonists, to the extent that they have separate goals.

2b. Failure, lack of goal

Groundhog Day: end of complicating action, suicidal despair. (p. 144)

Amadeus: end of setup, Salieri humiliated by Mozart, conceives strong resentment but no specific goal. (p. 191)

Parenthood: end of development, the parents are all resigned to their failures. (pp. 275-76)

3. Major new premise, reiteration of strategy

Witness: end of complicating action, Carter tells Book to stay hidden. (p. 29)

The Wrong Man: end of complicating action, Manny is freed on bail; he has the chance to try and prove his innocence. (p. 39)

Terminator 2: end of development, Sarah, Terminator, and John steal chip from Cyberdine, continue in their attempt to destroy it. (p. 42)

Amadeus: end of second development, Constanza leaves Mozart, allowing Salieri the access that will permit him to fulfill his goal of killing his rival. (p. 205)

4. Protagonist/Important character makes a decision, then changes or modifies goal

Little Shop of Horrors (1986): end of complicating action, Seymour agrees to kill someone to feed blood to Audrey II. (p. 29)

The Godfather: end of development, Michael says family will go legit, asks Kay to marry him. (p. 30)

Casablanca: end of complicating action, Rick rejects Ilsa’s account of her relationship with Victor. (p. 32)

The Producers: end of setup, Leo decides to join Max in committing fraud. (p. 38)

Tootsie: end of complicating action, Michael decides to start improvising Dorothy’s lines, setting up “her” success. (p. 64)

Back to the Future: end of development. Martie decides to leave a message for Doc warning him about the Libyan attack; the result is to save Doc from being killed. (p. 94)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of setup, Roberta apparently decides to pursue Susan, change her boring life. (p. 166)

Such decisions obviously form the basis for turning points fairly frequently, and by definition the protagonist is aware of what is happening.

5. Major Revelation, new goal or move into climax

Witness: end of setup, Book is told the killer is a cop, changes tactics, flees. (p. 28)

Witness: end of development, Book learns partner has been killed, realizes he must act. (p. 29)

The Bodyguard: end of development, revelation of Nikki as villain, attack on house, death of Nikki. (p. 31)

Terminator 2: end of setup, John discovers the Terminator must obey him, sets goals of protection without killing and of rescuing Sarah from the asylum. (p. 41)

Terminator 2: end of complicating action, Sarah realizes that the war can be prevented, conceives goal of killing Dyson. (p. 42)

Tootsie: end of development, Michael’s agent tells him he must get out of playing Dorothy without being charged with fraud. (p. 69)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of setup, Clarice finds the body in the warehouse and realizes that Lecter is willing to help her. (p. 115)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of development, Clarice and Ardelia realize “He knew her,” the clue that will lead to the solution. (p. 126)

Alien: end of development, revelation that the “company” and Ash are prepared to sacrifice the crew; will lead to decision by survivors to abandon the ship and save themselves. (p. 299)

Such revelations usually involve the protagonist knowing what is happening, but I believe there are exceptional cases where the viewer learns something that the protagonist does not. This kind of revelation often involves either villains turning out to be allies or apparent allies turning out to be villains.

Take the case of Demolition Man. At 54 minutes into the film, about nine minutes before the end of the complicating action, the audience learns that the apparently benevolent Dr. Cocteau (Nigel Hawthorne), who has developed the new pacifist society of Los Angeles, is a ruthless villain. This moment isn’t the turning point that ends the complicating action; I take that to be the escape of the “Scraps,” the rebels who oppose Cocteau, from their underground prison. Most of those nine minutes consist of the hero, John (Sylvester Stallone) meeting Cocteau and going out to dinner with him. John shows signs of strongly disliking the new society, and he refuses to kill the rebels when they escape. Still, there is no sign that he considers Cocteau a villain. Rather, John thinks of himself as a misfit and expresses a desire to leave the new Los Angeles. The turning point that ends the complication depends on his assumption that Cocteau on his side, even if John considers the leader’s bland society to be unattractive.

The development portion is full of typical delays: the scene of John visiting Lenina Huxley’s (Sandra Bullock) apartment, where she invites him to have virtual sex, and the following scene of John exploring the odd, modernistic apartment assigned to him. At 74 minutes in, or about six minutes before the end of the development, John begins to learn of Cocteau’s true nature. He confronts Cocteau in the latter’s office and nearly shoots him. The scene where John tells the members of the police department who remain loyal to him that they will invade the underground prison to capture Cocteau’s violent agent, Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes) marks the end of the development, with a new, specific goal determining the action of the climax.

Here is a case where for a significant portion of the narrative the protagonist remains ignorant of something that the audience has been shown. Even here, however, John displays a dislike of Cocteau and what he has done to Los Angeles society. Classical films seem disinclined to show their heroes as thoroughly deluded. John’s underlying decency and common sense make him ready to distrust a leader whom everyone else, including Lenina, admire.

6. Enough information accumulates to cause the formulation of goals

Back to the Future: end of complicating action, goals of synchronizing with lightning storm, getting Marty’s father and mother together at dance. (p. 90)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of complicating action. Information about gangsters and growing attraction to Dez lead to convergence of Roberta’s goals. (p. 170)

Parenthood: end of setup, in this case with multiple goals formed for four separate plotlines.

7. A disaster, accidental or deliberate, changes the characters’ situations/goals

The Wrong Man: end of setup, Manny is mistakenly arrested. (p. 39)

Jurassic Park: end of complicating action, Nedry shuts down the electricity grid of the park, letting the dinosaurs loose. (p. 32)

Jaws: end of complicating action; the attack involving his son makes Brody force the mayor to accept his original, thwarted tactic of hiring Quint. (p. 34)

Alien: end of setup, facehugger attaches itself to Kane. The goal conceived shortly thereafter is to investigate it and save him. (p. 292)

Alien: end of complicating action, alien bursts from Kane’s stomach; goal becomes to save the crew and ship. (p. 295)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of development, Roberta’s arrest leads to a low point, and she opts to turn to Dez for help. (p. 172)

Amadeus: end of first development, death of Leopold, which Salieri later exploits in his plot against Mozart. (p. 201)

The Hunt for Red October: end of complicating action, Ramius realizes he has a saboteur aboard and needs Ryan’s help; Ryan starts planning actively to help him. (p. 233)

8. Protagonist’s tactics are blocked or he/she is forced to use the wrong tactics

Jaws: end of setup, Brody’s desire to hire Quint rejected. (p. 23)

Back to the Future: end of setup, Doc sets time machine’s date; after new large-scale section begins, attack by Libyans accidentally sends Marty back to 1955. (p. 85)

Groundhog Day: end of setup, Phil trapped in repeating time, goal of becoming a network weather forecaster destroyed. He soon opts for irresponsible self-indulgence. (p. 139)

9. Characters working at cross-purposes resolve their differences

Jaws: end of development, the three main characters bond, allowing them to cooperate to kill the shark. (p. 35)

The Hunt for Red October: end of development, Ramius and Ryan make contact, with Captain Mancuso’s help, they start working together. (p. 237)

10. A supernatural premise determines a character’s behavior

Liar, Liar: end of setup, Max wishes that his father would have a day where he is unable to tell a lie. Also end of complicating action, where Max fails to cancel the wish. (p. 38)

11. The protagonist/major character succeeds in one goal, allowing him/her to pursue another

Liar, Liar: end of development, Fletcher wins his court case, freeing him to try and regain his wife and son. (p. 39)

The Hunt for Red October: end of setup, Ramius learns that the silent feature of his new submarine works; he apparently intends some sort of attack on the US but is in fact plotting an elaborate ruse to defect. (p. 225)

These examples suggest that protagonists usually do know about the major events that form turning points, or they learn about them shortly after they occur. The main exception would seem to be when there are two major parallel characters, one of whom is to some extent villainous, as in the case of Amadeus, where one of the characters is duped. This reminds me of The Producers, where Max and Leo leave the theater early, convinced that they have succeeded in their goal of creating a box-office disaster. Lingering in the theater, the narration allows us to see the transition from audience disgust to fascination. Only after the audience comes into the bar where the two partners are celebrating do they realize what has happened (“I never in a million years thought I’d ever love a show called Springtime for Hitler!”) To understand the irony and/or humor in such situations, the film spectator must at least briefly know more than the main characters do.

The examples also confirm that character goals seldom endure unchanged across the length of a film. Revelations, decisions, disasters, supernatural events, and presumably others kinds of causes frequently cause major shifts in characters’ goals or at least in the tactics they employ in pursuing them. Even in what seems like a fairly straightforward thriller like Alien, the crew’s assumptions that they must loyally protect their spaceship are completely reversed at the end of the development, and the narrative turns into an attack on corporate greed and ruthlessness. Whatever one thinks of classical Hollywood films, they are usually more complex than the three-act model allows for.

Note: My title comes from Robert Southwell’s poem of the same name.

[July 11: Jim Emerson has made some insightful comments on this entry on his Scanners blog.]

In critical condition

DB here:

A Web-prowling cinephile couldn’t escape all the talk about the decline of film criticism. First, several daily and weekly reviewers left their print publications, as Anne Thompson points out. Then one of our brightest critics, Matt Zoller Seitz, suspended writing in order to return to film production. This and the departure of another web critic, Raymond Young of Flickhead, has prompted Tim Lucas to ponder, at length and in depth, why one would maintain a film blog. Go to Moviezzz for a summing up.

I’ve been teaching film history and aesthetics since the early 1970s, but before that I wrote criticism for my college newspaper, the Albany Student Press, and then for Film Comment. When I set out for graduate school, film criticism was virtually the only sort of film writing I thought existed. Auteurism was my faith, and Andrew Sarris its true apostle (for reasons explained in an essay in Poetics of Cinema). In grad school, I learned that there were other ways of thinking about cinema. Since then, I’ve tried to steer a course among film criticism, film history, and film theory—sometimes doing one, sometimes mixing them. But criticism has remained central to my interest in cinema.

What, though, does the concept mean? I think that some of the current discussions about the souring state of movie criticism would benefit from some thoughts about what criticism is and does.

Watch your language

Consider criticism as a language-based activity. What do critics do with their words and sentences? Long ago, the philosopher Monroe Beardsley laid out four activities that constitute criticism in any art form, and his distinctions still seem accurate to me. (1) We use them in Chapter 2 of Film Art.

*Critics describe artworks. Film critics summarize plots, describe scenes, characterize performances or music or visual style. These descriptions are seldom simply neutral summaries. They’re usually perspective-driven, aiding a larger point that the critic wants to make. A description can be coldly objective or warmly partisan.

*Critics analyze artworks. For Beardsley, this means showing how parts go together to make up wholes. If you simply listed all the shots of a scene in order, that would be a description. But if you go on to show the functions that each shot performs, in relation to the others or some broader effect, you’re doing analysis. Analysis need not concentrate only on visual style. You can analyze plot construction. You can analyze an actor’s performance; how does she express an arc of emotion across a scene? You can analyze the film’s score; how do motifs recur when certain characters appear? Because films have so many different kinds of “parts,” you can analyze patterns at many levels.

*Critics interpret artworks. This activity involves making claims about the abstract or general meanings of a film. The word “interpret” is used in lots of ways, but in the sense meant here, figuring out the chronological order of scenes in Pulp Fiction wouldn’t count. If, though, you claim that Pulp Fiction is about redemption, both failed (Vincent) and successful (Jules’ decision to quit the hitman trade), you’re launching an interpretation. If I say that Cloverfield is a symbolic replay of 9/11, that counts as an interpretation too.

*Critics evaluate artworks. This seems pretty straightforward. If you declare that There Will Be Blood is a good film, you’re evaluating it. For many critics, evaluation is the core critical activity; after all, the word critic in its Greek origins means judge. Like all the other activities, however, evaluation turns out to be more complicated than it looks.

Why break the process of criticism into these activities? I think they help us clarify what we’re doing at any moment. They also offer a rough way to understand the critical formats that we usually encounter.

In paper media, on TV, or on the internet, we can distinguish three main platforms for critical discussion. A review is a brief characterization of the film, aimed at a broad audience who hasn’t seen the film. Reviews come out at fixed intervals—daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly. They track current releases, and so have a sort of news value. For this reason, they’re a type of journalism.

An academic article or book of criticism offers in-depth research into one or more films, and it presupposes that the reader has seen the film (or doesn’t mind spoilers). It isn’t tied to any fixed rhythm of publication.

A critical essay falls in between these types. It’s longer than a review, but it’s usually more opinionated and personal than an academic article. It’s often a “think piece,” drawing back from the daily rhythm of reviewing to suggest more general conclusions about a career or trend. Some examples are Pauline Kael’s “On the Future of Movies” and Philip Lopate’s “The Last Taboo: The Dumbing Down of American Movies.” (2) Critical essays can be found in highbrow magazines like The New Yorker and Artforum, in literary quarterlies, and in film journals like Film Comment, CinemaScope, and Cahiers du Cinéma.

Any critic can write on all three platforms. Roger Ebert is known chiefly for his reviews, but his Great Movies books consist of essays. (3) J. Hoberman usually writes reviews, but he has also published essays and academic books. And the lines between these formats aren’t absolutely rigid, as I’ll try to show later.

Reviewing reviewers

How do these forums relate to the different critical activities? It seems clear that academic criticism, the sort published in research articles or books, emphasizes description, analysis, and interpretation. Evaluation isn’t absent, but it takes a back seat. Usually the academic critic is concerned to answer a question about the films. How, for instance, is the theme of gender identity represented in Rebecca, and what ambiguities and contradictions arise from that process? In order to pursue this question, the critic needn’t declare Rebecca a great film or a failure.

Of course, the academic piece could also make a value judgment, either at the outset (I think Rebecca is excellent and want to scrutinize it) or at the end (I’m forced to conclude that Rebecca is a narrow, oppressive film). But I don’t have to pass judgment. I have written about a lot of ordinary films in my life. They became interesting because of the questions I brought to them, not because they had a lot going for them intrinsically.

The academic article has a lot of space to examine its question—several thousand words, usually—and of course a book offers still more real estate. By contrast, a review is pinched by its format. It must be brief, often a couple of hundred words. Unlike the academic critique, the review’s purpose is usually to act as a recommendation or warning. Most readers seek out reviews to get a sense of whether a movie is worth seeing or even whether they would like it.

Because evaluation is central to their task, reviewers tend to focus their descriptions on certain aspects of the film. A reviewer is expected to describe the plot situation, but without giving away too much—major twists in the action, and of course the ending. The writer also typically describes the performances, perhaps also the look and feel of the film, and chiefly its tone or tenor. Descriptions of shots, cutting patterns, music, and the like are usually neglected. And what is described will often be colored by the critic’s evaluation. You can, for instance, retell the plot in a way that makes your opinion of the film’s value pretty clear.

Reviews seldom indulge in analysis, which typically consumes a lot of space and might give away too much. Nor do reviewers usually float interpretations, but when they do, the most common tactic is reflectionism. A current film is read in relation to the mood of the moment, a current political controversy, or a broader Zeitgeist. A cynic might say that this is a handy way to make a film seem important and relevant, while offering a ready-made way to fill a column. Reviewers don’t have a monopoly on reflectionism, though. It’s present in the essayistic think-piece and in academic criticism too. (4)

The centrality of evaluation, then, dictates certain conventions of film reviewing. Those conventions obviously work well enough. But we can learn things about cinema through wide-ranging descriptions and detailed analyses and interpretations, as well. We just ought to recognize that we’re unlikely to get them in the review format.

The good, the bad, and the tasty

Let’s look at evaluation a little more closely. If I say that I think that Les Demoiselles de Rochefort is a good film, I might just be saying that I like it. But not necessarily. I can like films I don’t think are particularly good. I enjoy mid-level Hong Kong movies because I can see their ties to local history and film history, because I take delight in certain actors, because I try to spot familiar locations. But I wouldn’t argue that because I like them, they’re good. We all have guilty pleasures—a label that was coined exactly to designate films which give us enjoyment, even if by any wide criteria they aren’t especially good.

They needn’t be disastrously bad, of course. I do like Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, inordinately. It’s my favorite Demy film and a film I will watch any time, anywhere. It always lifts my spirits. I would take it to a desert island. But I’m also aware that it has its problems. It is very simple and schematic and predictable, and it probably tries too hard to be both naive and knowing. Artistically, it’s not as perfect as Play Time or as daring as Citizen Kane or as….well, you go on. It’s just that somehow, this movie speaks to me.

The point is that evaluation encompasses both judgment and taste. Taste is what gives you a buzz. There’s no accounting for it, we’re told, and a person’s tastes can be wholly unsystematic and logically inconsistent. Among my favorite movies are The Hunt for Red October, How Green Was My Valley, Choose Me, Back to the Future, Song of the South, Passing Fancy, Advise and Consent, Zorns Lemma, and Sanshiro Sugata. I’ll also watch June Allyson, Sandra Bullock, Henry Fonda, and Chishu Ryu in almost anything. I’m hard-pressed to find a logical principle here.

Taste is distinctive, part of what makes you you, but you also share some tastes with others. We teachers often say we’re trying to educate students’ tastes. True, but we should admit that we’re trying to broaden their tastes, not necessarily replace them with better ones. Elsewhere on this site I argue that tastes formed in adolescence are, fortunately, almost impossible to erase. But we shouldn’t keep our tastes locked down. The more different kinds of things we can like, the better life becomes.

The difference between taste and judgment emerges in this way: You can recognize that some films are good even if you don’t like them. You can declare Birth of a Nation or Citizen Kane or Persona an excellent film without finding it to your liking.

Why? Most people recognize some general criteria of excellence, such as originality, or thematic significance, or subtlety, or technical skill, or formal complexity, or intensity of emotional effect. There are also moral and social criteria, as when we find films full of stereotypes objectionable. All of these criteria and others can help us pick out films worthy of admiration. These aren’t fully “objective” standards, but they are intersubjective—lots of people with widely varying tastes accept them.

So critics not only have tastes; they judge. The term judgment aims to capture the comparatively impersonal quality of this sort of evaluation. A judge’s verdict is supposed to answer to principles going beyond his or her own preferences. Judges at a gymnastic contest provide scores on the basis of their expertise and in recognition of technical criteria, and we expect them to back their judgment with detailed reasons.

One more twist and I’m done with distinctions. At a higher level, your tastes may make you weigh certain criteria more heavily than others. If you most enjoy movies that wrestle with philosophical problems, you may favor the thematic-significance criterion. So you’ll love Bergman and think he’s a great director. In other words, you can have tastes in films that you also consider excellent. Presumably this is what we teachers are trying to cultivate as well: to teach people, as Plato urged, to love the good.

Of course we can disagree about relevant criteria, particularly about what criteria to apply to a particular movie. I’d argue that profundity of theme isn’t a very plausible criterion for judging Cloverfield; but formal originality, technical skill, and intensity of emotional appeal are plausible criteria to apply. Many of the best Hong Kong films don’t apply rank high on subtlety of theme or character psychology, but they do well on technical originality and intensity of visceral and emotional response. You may disagree, but now we’re arguing not about tastes but about what criteria are appropriate to a given film. To get anywhere, our conversation will appeal to both intersubjective standards and discernible things going on in the movie–not to whether you got a buzz from it and I didn’t.

There’s a reason they call that DVD series Criterion

Now back to film reviewing. Judgment certainly comes into play in a film review, because the critic may invoke criteria in evaluating a movie. Such criteria are widely accepted as picking out “good-making” features. For instance:

The plot makes no sense. Criterion: Narrative coherence helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

The acting is over the top. Criterion: Moderate performance helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

The action scenes are cut so fast that you can’t tell what’s going on. Criterion: Intelligibility of presentation helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

Most reviewers, though, can’t resist exposing their tastes as well as their judgments. This is a convention of reviewing, at least in the most high-profile venues. Readers return to reviewers with strongly expressed tastes. Some readers want to have their own tastes reinforced. If you think Hollywood pumps out shoddy product, Joe Queenan will articulate that view with a gonzo relish that gives you pleasure. Other readers want to have their tastes educated, so they seek out a strong personality with clear-cut tastes to guide them. Still other readers want to have their tastes tested, so they read critics whose tastes vary widely from theirs. I’m told that many people read Armond White for this reason. Tastes come in all flavors.

Celebrity critics—the reviewers who attract attention and controversy—are usually vigorous writers who have pushed their tastes to the forefront. Top critics like Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael are famous partly because they flaunted their tastes and championed films that they liked. (Of course they also thought that the films were good, according to widely held criteria.) It isn’t only a matter of praise, either. Every so often critics launch all-out attacks on films, directors, or other critics, and some are permanently cranky. Movie reviewer Jay Sherman (above) ranks films by analogy to diseases. Hatchet jobs assure a critic notoriety, but they also prove Valéry’s maxim that “Taste is made of a thousand distastes.”

At a certain point, celebrity critics may even give up justifying their evaluations altogether, simply asserting their preferences. They trust that their track record, their brand name, and their forceful rhetoric will continue to engage their readers. It seems to me that after decades of stressing the individuality of their tastes, many of the most influential reviewers are emitting two main messages: You see it or you don’t and Differ if you dare. I’d like to see more argument and less strutting. But then, that’s my taste.

Stuck in the middle, with us

There’s much more to say about the distinctions I’ve floated. They are rough and need refining. But they’ll do for my purpose today, which is to indicate that everything I’ve said can apply to Web writing.

For instance, it seems likely that one cause of critical burnout is that reviews dominate the Net. They’re typically highly evaluative, mixing taste and judgment. Many people will find a bombardment of such items eventually too much to take. I could imagine somebody abandoning Net criticism simply because of the cacophony of shrieking one-liners. We’re all interested in somebody else’s opinions, but we can’t be interested in everybody else’s opinions.

In addition, the distinguishing feature among these thousands of reviews won’t necessarily be wit or profundity or expertise, but style. I think that, years ago, the urge toward self-conscious critical style arose from the drudgery of daily reviewing. Faced with a dreadful new movie, you could make your task interesting only by finding a fresh way to slam it. In addition, magazines that wanted to appear smart encouraged writers to elevate attitude above ideas. In the overabundance of critical talk on the Net, saying “It’s great” or “It stinks” in a clever way will draw more attention than plainer speaking, but even that novelty will wear off eventually.

Fortunately, there are other formats available to cybercriticism. At first glance, the Web seems to favor the snack size, the 150-word sally that’s all about taste and attitude. In fact, the Net is just as hospitable to the long piece. There are in principle no space limitations, so one can launch arguments at length. (It’s too long to read scrolling down? Print it out. Maybe you have to do that with this essay.) Thanks to the indefinitely large acreage available, one of the heartening developments of Web criticism is the growth of the mid-range format I’ve mentioned: the critical essay.

Historically, that form has always been closer to the review than to the academic piece. It relies more on evaluation. That’s centrally true of the Kael and Lopate essays I mentioned above, both of which warn about disastrous changes in Hollywood moviemaking. But the tone can be positive too, most often seen in the appreciative essay, which celebrates the accomplishment of a film or filmmaker. Dwight Macdonald’s admiring piece on 8 ½ and Susan Sontag’s 1968 essay on Godard, despite their differences, seem to me milestones in this genre. (5)

The critical essay is, I think, the real showcase for a critic’s abilities. We say that good critics have to be good writers, usually meaning that their style must be engaging, but it doesn’t have to explode at the end of every paragraph. More generally, in a long essay, you are forced to use language differently than in a snippet. You need to build and delay expectations, find new ways to repeat and modify your case, and seek out synonyms.

Just as important, the long piece separates the sheep from the goats because it shows a critic’s ability to sustain a case. The short form lets you pirouette, but the extended essay—unless it’s simply a rant—obliges you to show all your stuff. In the long form, your ideas need to have heft. Stepping outside film for a moment, consider Gary Giddins on Jack Benny, or Geoffrey O’Brien on Burt Bacharach, or Robert Hughes on Goya, and in each you will see a sprightly, probing, deeply informed mind develop an argument in surprising ways. (6) Strikingly, all these writers venture into subtleties of analysis and interpretation, putting them close to the academic model. So who needs footnotes?

Above all, the critical essay can develop new depth on the Web. Given more space, the Web can ask critics to lay out their assumptions and evidence more fully. After years of “writing short,” of firing off invectives, put-downs, and passing paeans to great filmmakers unknown to most readers, critics now have an opportunity—not to rant at greater length but to go deeper. If you think a movie is interesting or important, please show us. Don’t simply assert your opinion with lots of hand-waving, but back it up with some analysis or interpretation. The Web allows analysis and interpretation, which take a lot of effort, to come into their own.

Need an example? Jim Emerson, time and again. There are plenty of other instances hosted by journals like Rouge and the extraordinary Senses of Cinema, and many solo efforts, such as a recent one from Benjamin Wright.