Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Frodo Franchise pre-orders and other updates and tidbits

Kristin here–

The Frodo Franchise

The Frodo Franchise, my book on the Lord of the Rings film phenomenon, is now available for pre-order from Amazon or directly from the University of California Press. It should be in bookstores in August. The cover illustration above is by the wonderful caricaturist Victor Juhasz. Check out another example of his work here; I especially like the image of Jack Nicholson.

(In New Zealand, The Frodo Franchise will be published by Penguin New Zealand, also in August. I’ll add a link to their website when pre-orders become available.)

I’ll be writing more about the book and the Lord of the Rings film between now and August, including, I hope, reporting from Wellington during David’s and my visit to New Zealand in May.

The Hobbit: Faint signs of movement

The April issue of Wired (I can’t find this on their website as of now) has a brief interview with Bob Shaye (p. 88), whose second feature film as a director, The Last Mimzy, was released on March 23. Naturally the subject of the Hobbit film gets mentioned.

On October 2, in the infancy of this blog, I discussed Peter Jackson’s other projects and whether they allowed him enough leeway to take on directing The Hobbit. I suggested that he had built considerable flexibility into his apparently crowded schedule. At that point it looked as though he might well get the offer.

Then, on January 13 I reported on Shaye’s recent declaration that because Jackson was suing New Line concerning money possibly owed him from Fellowship of the Ring and its related products, the director would not be making The Hobbit for New Line (and MGM, which is co-producing the film).

Since the flutter of anger expressed over that decision, there has been virtually no news on the subject. Now, asked by Wired about his January statement, Shaye replied, “You know, we’re being sued right now, so I can’t comment on ongoing litigation. But I said some things publicly, and I’m sorry that I’ve lost a colleague and a friend.”

Wired then asked, “Is The Hobbit still a viable project?” Shaye responded, “I can only say we’re going to do the best we can with it. I respect the fans a lot.”

Given that a large majority of the fans consider Jackson’s direction key to the film being the best New Line could do, perhaps we’re getting a hint that Shaye is relenting.

Matt Zoller Seitz and friends in Newsweek!

Matt’s site The House Next Door sends us business every now and then, and it was a treat to see it mentioned in “Blog Watch” in the April 9 issue of Newsweek (also online): “‘The Sopranos’ returns to HBO on April 8, and mob fans can’t wait to get deep inside the remaining episodes. For insightful commentary, check out mattzollerseitz.blogspot.com.”

A variety of commentators contributed to the “Sopranos Week” daily postings: April 2, April 3, April 4, April 5, April 6, April 7, and April 8.

Congratulations, Matt and company!

David’s film-viewing activities do not go unnoticed

Lester Hunt, who teaches philosophy here at the University of Wisconsin, has been blogging about students who don’t take notes in class. He considers, not unreasonably, that they should take notes. Not everyone agrees with him, however.

Lester defends his position staunchly in a new post, “Why you should take notes,” citing David’s note-taking and shot-counting during movies as evidence to bolster his case. As the one who often sits beside David during his very active viewings, I can testify that Lester’s description is quite accurate.

Ebertfest coming up

Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog provides information about the upcoming Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival (next year to be officially renamed what many of us call it anyway, “Ebertfest”), April 25-28. As Jim mentions, David and I are among the guests, and you can read the opening of my program notes for this year’s silent-film-with-live-musical-accompaniment presentation, Raoul Walsh’s Sadie Thompson. Along with others, we’ll be pitching in to try and fill in for Roger as he continues to recover from his health problem of last summer.

Fortunately Roger will be able to attend. As he writes in his recent description of his progress, “I think of the festival as the first step on my return to action.” The first of many such steps, I hope. We all look forward to 2008, when he will move once more to center stage as the heart and soul of Ebertfest.

Aardman’s new home

Finally, I have groused about how DreamWorks failed to exploit the potential of British animation company Aardman’s product. (See here and here.) Distributing films like Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-rabbit and Flushed Away, Dreamworks showed little inclination to try and turn Aardman into a brand comparable to Pixar.

Now, after the January split between DreamWorks and Aardman, Variety announces that the latter has signed a three-year, first-look arrangement with Sony Pictures Entertainment. The deal sounds promising, with Aardman expanding its Bristol facilities and stepping up the rate of production. The plan is to release a film every 18 months.

[Added April 11:

The print version of the Variety article (April 9-15 issue) is distinctly longer than the online one linked above. Author Adam Dawtrey’s description of DreamWorks tends to confirm my belief that the company handled its Aardman deal badly: “If you knew nothing about British toon studio Aardman except what DreamWorks saw fit to tell Wall Street every quarter, you might wonder why Sony was so eager to pick up where Jeffrey Katzenburg left off … Yet the multi-Oscar-winning claymation specialist had no shortage of suitors before settling on a new three-year deal last week with Sony Pictures Entertainment.”

Dawtrey points out that Chicken Run grossed $225 million worldwide, the Wallace & Gromit feature took $192 million, “and even the maligned ‘Flushed Away’ managed $176 million. The fact that Aardman’s pics … do the majority of their business outside the U.S. clearly bothers Sony much less than it did DreamWorks.”

The first two films cost less than $50 million apiece to make, while Flushed Away cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $140 million. Dawtrey adds, “The fact that Aardman execs don’t even know the precise cost of ‘Flushed Away’ betrays just how much control they ceded to DreamWorks by moving production to Los Angeles. It was a doomed attempt to find a transatlantic compromise that would salvage the relationship, but the result left both sides frustrated.”]

DreamWorks Animation decided to “concentrate on just two major releases a year.” That means just blockbusters, with no need for the more eccentric Englishness of Aardman.

Sony, on the other hand, wants to expand its animation and family-oriented product. The CEO and chairman of SPE, Michael Lynton is quoted as saying, “Aardman Features is enormously popular around the world. We believe that their strength is their unique storytelling humor, sensibility and style and we plan to bring their distinctive animated voice to theaters for a long time to come.”

Of course, intentions are always good at the beginning. Whether Sony can let Aardman be Aardman and help the company’s films achieve the success they deserve remains to be seen. I certainly hope so.

Plus it’s good to hear that one of the four features Aardman has in development is another Wallace and Grommit project. Break out the Wensleydale!

Homage to Mme. Edelhaus

Why are Americans polarized between francophobia and francophilia? Some people mock the French for liking Jerry Lewis, when most French people probably don’t even know who he is. Others think that France is the repository of world culture and represents the finest in writing about the arts, even though the Parisian intelligentsia can be pretentious and hermetic.

But we must face facts. When it comes to cinephilia, the French have no equals. They grant film a respect that it wins nowhere else. Spend a year, or even a month, in Paris, and you will feel like a Renaissance prince. This is a city where one lonely screen can run tattered prints of One from the Heart and Hellzapoppin!, once a week, indefinitely.

My first trip was too brief, only a week in 1970, but my second one—four weeks of dissertation research in 1973—left me exhausted. Reading Pariscope on the way in from the airport, I learned about a Tex Avery festival. I checked into my hotel and Métro’d to the theatre, where I and a bunch of moms and kids gazed in rapture upon King-Size Canary. Another time, also coming in from the airport, Kristin and I passed a marquee for King Hu’s Raining in the Mountain. Next stop, Raining in the Mountain. My memories of The Naked Spur, Ministry of Fear, Liebelei, Tati’s Traffic, and Vertov’s Stride Soviet! are inextricable from the Parisian venues in which I saw them.

Sound like a lament for days gone by? Nope. You can find the same variety on offer today. Of course the two monthlies, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, have to take a lot of credit for this. Add Traffic, Cinéma, and several other ambitious journals, and you get a film culture unrivalled in the world.

Critics from Louis Delluc onward have led thousands of readers toward appreciating the seventh art. Historians like Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, Laurent Mannoni, Francis Lacassin, and others have enlightened us for decades. Academic film analysis would not be what it is without Raymond Bellour, Noel Burch, Marie-Claire Ropars, Jacques Aumont, and a host of other scholars. Above all stands André Bazin, the greatest theorist-critic we have had.

And the books! Arts-and-sciences publishing receives government subsidies; the French understand that books contribute to the public good. There are plenty of worse ways to spend tax dollars (e.g., trumped-up military invasions). The French, like the Italians, have created an ardent translation culture too. If you can’t read something in Russian or German, there’s a good chance it’s available in French.

I was reminded of the glories of Gallic film publishing when the mailman tottered to my door this week with twenty-two pounds worth of recent items I’d ordered. I haven’t even read them yet; otherwise, they’d be filed with Book Reports. Instead I want to spend today’s blog celebrating them as fruits of an ambition that has no counterpart in English-language publishing. All are grand and gorgeous and informative to boot.

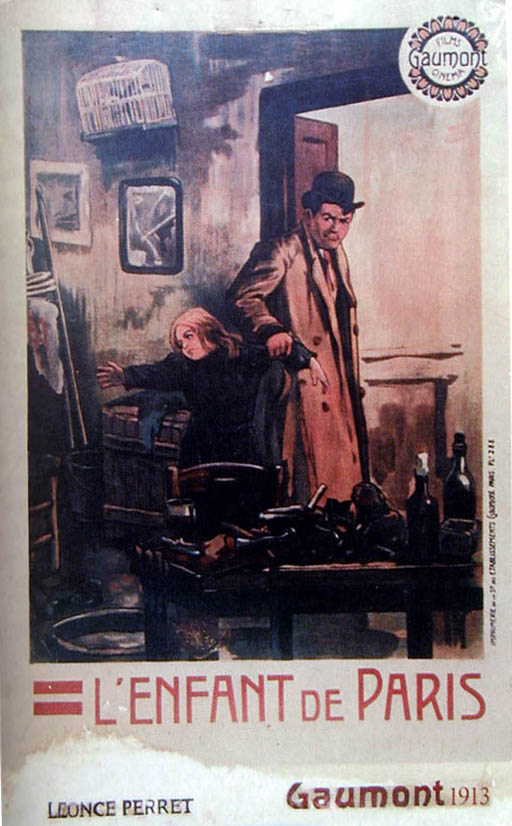

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

A biographical study of a Gaumont director still too little known. Perret was second only to Feuillade at Gaumont, and he performed as a fine comedian as well. His shorts are charming, and his longer works, like L’enfant de Paris (1913), remain remarkable for their complex staging and cutting. After a thriving career in France, Perret came to make films in America, including Twin Pawns (1919), a lively Wilkie Collins adaptation. He returned to France and was directing up to his death in 1935.

Although the text seems a bit cut-and-paste, Taillé has included many lovely posters and letters, along with a detailed filmography, full endnotes, and a vast bibliography. It compares only to that deluxe career survey of the silent films of Raoul Walsh, published by Knopf. . . .Oh, wait, there’s no such book. . . .Think there ever will be?

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

A luscious catalogue of an exposition tracing visual sources of Disney’s animation. Illustrated with sketches, concept paintings, and character designs from the Disney archives, this volume shows how much the cartoon studio owed to painting traditions from the Middle Ages onward. It includes articles on the training schools that shaped the studio’s look, on European sources of Disney’s style and iconography, on architecture, on relations with Dalí, and on appropriations by Pop Artists. There’s also a filmography and a valuable biographical dictionary of studio animators.

Some of the affinities seem far-fetched, but after Neil Gabler’s unadventurous biography, a little stretching is welcome. This exhibition (headed to Montreal next month) answers my hopes for serious treatment of the pictorial ambitions of the world’s most powerful cartoon factory. The catalogue is about to appear in English–from a German publisher.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

The authors of a lengthy study of Citizen Kane now take us through the production process of each of Welles’ works. They have stuffed their book with script excerpts, storyboards, charts, timelines, and uncommon production stills.

The text, on my cursory sampling, will seem largely familiar to Welles aficionados; the frames from the actual films betray their DVD origins; and I would like to have seen more depth on certain stylistic matters. (The authors’ account of the pre-Kane Hollywood style, for instance, is oversimplified.) Yet the sheer luxury of the presentation overwhelms my reservations. A colossal filmmaker, in several senses, deserves a colossal book like this.

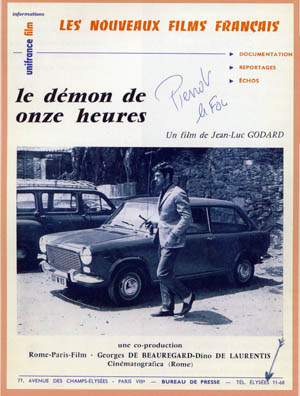

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

In the same series as the Welles volume, even more imposing. If you want to know the shooting schedule for Alphaville or check the retake report for La Chinoise (these are eminently reasonable desires), here is the place to look. Detailed background on the production of every 1960s Godard movie, with many discussions of the creative choices at each stage. Once more, stunningly mounted, with lots of color to show off posters and production stills.

Anybody who thinks that Godard just made it up as he went along will be surprised to find a great degree of detailed planning. (After all, the guy is Swiss.) Yet the scripts leave plenty of room to wiggle. “The first shot of this sequence,” begins one scene of the Contempt screenplay, “is also the last shot of the previous sequence.” Soon we learn that “This sequence will last around 20-30 minutes. It’s difficult to recount what happens exactly and chronologically.”

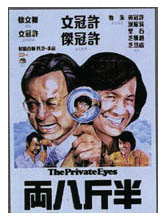

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

The avoirdupois champ of my batch. The French were early admirers of modern Hong Kong cinema, but their reference works lagged behind those of Italy, Germany, and the US. (Most notable of the last is John Charles’ Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997.) More recently the French have weighed in, literally. 2005 gave us Christophe Genet’s Encyclopédie du cinéma d’arts martiaux, a substantial (2 lbs.) list of films and personalities, with plots, credits, and French release dates.

Newer and niftier, the Gouneau/ Amara volume covers much more than martial arts, and so it strikes my tabletop like a Shaolin monk’s fist. There are lovely posters in color and plenty of photos of actors that help you identify recurring bit players. Yet this is more than a pretty coffee-table book. It offers genre analysis, history, critical commentary, biographical entries, surveys of music, comments on television production, and much more. It has abbreviated lists of terms and top box-office titles, as well as a surprisingly detailed chronology.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Mme. Edelhaus was my high school French teacher. A stout lady always in a black dress, she looked like the dowager at the piano during the danse macabre of Rules of the Game. She was mysterious. She occasionally let slip what it was like to live under Nazi occupation, telling us how German soldiers seeded parks and playgrounds with explosives before they left Paris. When I asked her what avant-garde meant, she replied that it was the artistic force that led into unknown regions and invited others to follow–pause–“in the unlikely event that they will choose to do so.”

For three years Mme. Edelhaus suffered my execrable pronunciation. When I tried to make light of my bungling, she would ask, “Dah-veed, why must you always play the fool?”

I suppose I’m still at it. But thanks largely to her I’m able to read these books as well as look at them. She opened a path that’s still providing me vistas onto the splendors of cinema.

Classical cinema lives! New evidence for old norms

Hero.

Kristin here—

Note: This entry was written for Jim Emerson’s Contrarian Blog-a-Thon (III).

When David and I got into film studies in the late 1960s and early 1970s, an era of Hollywood’s history was drawing to a close. Many of the great directors who had defined the classical studio era from the period of World War I to the early age of television were at or approaching retirement. Andrew Sarris’s pivotal book, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 (1968) came out just in time to elevate their reputations by dubbing them with the fashionable French term auteur.

John Ford and Howard Hawks made their last films in this period (7 Women, 1966, and Rio Lobo, 1970). Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and Vincente Minnelli kept driecting into the 1970s, though few would say their late films stacked up to their earlier ones. (Preminger did manage to struggle back after a string of turkeys to make a very creditable final film, The Human Factor, in 1980.) Sam Fuller kept working through the 1980s, but he had to go to France to do it. Billy Wilder’s last film came out in 1981, though most of us wish he had stopped with The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes in 1970.

The decline of these greats coincided with the rise of the New Hollywood generation, whose directors, originally dubbed “the movie brats,” have become the grand old men of the current cinema. It also coincided with the early rumblings of the blockbuster (Jaws, 1975) and franchise (Star Wars, 1977) age that we know today. Definitely a shift took place in the 1970s, but to what?

Many film historians have claimed that the films that have come out of Hollywood since roughly the end of the 1980s are radically different from those of the classical “Golden Age.” Factors like television, videogames, spectacular special effects, moviegoers with short attention spans, the internet, the acquisition of the old studios by multi-national corporations, and the resulting rise of franchises have all putatively given rise to a “post-classical” cinema. This phenomenon is sometimes also referred to as the “post-Hollywood” or “post-modern” era.

I’m suspicious of the “post” terms, vague as they are. Usually stylistic labels describe what something is, not what it follows. Do we speak of “post-silent” or “post black-and-white” cinema?

Post-classical films supposedly jettison the old norms of style and storytelling. Frenetic editing, constant camera movement, product placement, juggled time-schemes—these and other tropes of recent cinema have replaced the continuity system, the carefully structured screenplay, and the character-based storytelling of the classical era. Computer-generated imagery has enabled filmmakers to create action scenes, spectacular settings, and fantastical creatures that hold our attention so thoroughly that the plot ceases to matter.

Or not. David and I have spent much of our professional careers studying the norms of classical filmmaking. We’ve swum against the stream by claiming that, despite many changes in style and technique, the fundamental norms of classical storytelling have remained intact. The classical cinema is with us still, precisely because it enables filmmakers to present us with absorbing plots and characters. It also is a flexible filmmaking approach that can absorb new technologies and new influences from other media and bend them to its own uses.

It’s less seductive to proclaim a long-term stability in Hollywood than to trumpet revolutionary, transformational, epochal changes. Still, some things just work so well that people want to keep them going as is. American films have dominated world screens since 1915. Why tinker with an approach that works so well?

It’s amazing to think of it now, but back in the late 1970s, virtually no one had studied the traditional norms of Hollywood filmmaking. We all knew what the distinctive traits of the great auteurs were, but distinctive as opposed to what? Academics kept saying that someone should figure out just what the cinema of the classical studio era consisted of. What principles guided filmmakers? What assumptions did they share? Not realizing how much material was available on Hollywood cinema, we and our colleague Janet Staiger set out to document the norms of style, technology, and mode of production that composed the “classical Hollywood cinema.”

The result was a much larger tome than we had expected, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (1985). After finishing it, David and I dusted off our hands, figuring that we had dealt with that topic. We went back to studying non-classical directors like Ozu, Eisenstein, Tati, Godard, Bresson, and Hou, confident that we had the knowledge to show exactly how and why their work differed from standard filmmaking.

Then claims about post-classical filmmaking started to appear. In our book, we had limited our survey to pre-1960 cinema because the breakdown of the studio structure and the competition from television led to a different situation in Hollywood. We did not, however, say that classical filmmaking died then. Quite the contrary; we said that it had endured through those changes in the industry.

Those favoring the post-classical explanation obviously disagreed with that. Bypassing our claims for the endurance of classical filmmaking, they borrowed our cut-off date of 1960, as if we had intended that year to signal the end of all aspects of the classical cinema—style, storytelling, mode of production, technology, the whole thing.

During the 1990s it became apparent that claims about post-classical cinema were becoming one very common way of dealing with modern Hollywood films. We decided to move well beyond 1960 and show that classical norms still prevail in American mainstream cinema. I wrote Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999), which analyzes ten successful films of the 1980s and 1990s to show that they use narrative principles that are virtually the same as those that were standard in the 1930s and 1940s. Goal-oriented characters, dangling causes, appointments, double plot-lines, carefully timed turning points, redundancy—all these classical devices are still very much with us. The claim was not that every single film coming out of Hollywood adhered to classical norms, only that the vast majority did.

David went on to make a similar argument in The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006), though he deals with visual style as well as narrative. There he examines some of the new norms of storytelling, showing how they are variants of the older classical system. He discusses, for example, “intensified continuity,” where tighter framings on actors, faster cutting, and prowling camera movements have modified but not replaced the standard continuity approach to presenting a conversation scene.

One of the most persistent claims by proponents of a post-classical era is the spectacle made possible by CGI. With the thrilling fight sequences of The Matrix, the vast battles of The Lord of the Rings, the extensive recreation of historical places of Gladiator, and the fantastical creatures and places of The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the individual scene supposedly becomes more spellbinding than the story in which it is embedded.

David and I have tried to refute this claim to some extent. I talk about Terminator 2 in the first chapter of Storytelling, showing that it has a tightly constructed, character-based narrative. David has a chapter section called “A Certain Amount of Plot: Tentpoles, Locomotives, Blockbusters, Megapictures, and the Action Movie,” where he examines films like Judge Dredd and The Rock. He demonstrates that they, too, have plots that adhere to traditional Hollywood norms. He puts forth a more detailed analysis in this online essay.

We’ve never really dealt much, however, with the issue of how CGI may or may not have elevated spectacle over narrative interest. Luckily now a new book does that and does it very well. Shilo T. McClean, in her Digital Storytelling: The Narrative Power of Visual Effects in Film (MIT Press, 2007), agrees with much of what we have claimed about the survival of classical filmmaking (though The Way Hollywood Tells It came out too late for her to have seen it). She builds upon our case by examining systematically and imaginatively the question of whether digital special effects support narrative interest. McClean convincingly demonstrates that DVFx (digital visual effects), as she terms them, are used in an enormous variety of ways, and most of these help to tell classically constructed stories.

We’ve never really dealt much, however, with the issue of how CGI may or may not have elevated spectacle over narrative interest. Luckily now a new book does that and does it very well. Shilo T. McClean, in her Digital Storytelling: The Narrative Power of Visual Effects in Film (MIT Press, 2007), agrees with much of what we have claimed about the survival of classical filmmaking (though The Way Hollywood Tells It came out too late for her to have seen it). She builds upon our case by examining systematically and imaginatively the question of whether digital special effects support narrative interest. McClean convincingly demonstrates that DVFx (digital visual effects), as she terms them, are used in an enormous variety of ways, and most of these help to tell classically constructed stories.

McClean’s basic points are two. First, DVFx are not used just in the more obvious ways, for big action scenes or elaborate fantasy and science fiction settings. They are applied for a wide range of purposes, from dustbusting (removing dust and other minor flaws from frames) to spectacular scenes. Far from being inevitably spectacular, DVFx are often invisible. (1)

Second, McClean claims that whether modest or spectacular, DVFx usually serve the narrative in some way—and she points out that practitioners in the industry invariably make that same claim.

Digital Storytelling started out as McClean’s dissertation at the University of Technology Sydney. It betrays its origins in a survey of the literature that takes up the first two chapters. There the author is somewhat too conciliatory, for my taste anyway, to a number of theorists’ claims about the breakdown of narrative in the digital-effects age. She tries to find something useful in each writer’s position, even though some of those positions are irreconcilable with the general standpoint she adopts.

Chapter 3 sketches the history of computer graphics and how they came to be used in films. McClean points out that DVFx are perfectly suited to the three criteria for the adoption of new technology that David and Janet formulated in their sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: greater efficiency, product differentiation, and support for achieving standards of quality. Like sound and color, DVFx have marked a major technological shift for the film industry, but like them, DVFx have been readily integrated into the existing division of labor. A modern digital studio, as she says, functions in much the same way as a physical one does. Indeed, in watching the credits of a modern film, we see lighting, matte paintings, and so on listed as the specialties for the digital craftspeople.

In these early chapters, McClean points out that in many ways DVFx simply replaces the traditional special effects of the pre-digital age. Most of Citizen Kane’s many effects are not supposed to be noticeable, and indeed for years historians were unaware of just how many it contained. In cases where DVFx create a flashy effect, as in the virtual camera movements through walls in Panic Room, the function is to inform the viewer of the locations of various characters and create suspense. Probably the most vital lesson one could take away from this book is that techniques can serve multiple purposes in a film. Spectacularity, as McClean calls it, and storytelling can co-exist in the same digital images.

The author also explains that, unlike what many writers say about DVFx, they are not simply a post-production technique used to ramp up the visual appeal of a film. Computer imagery is used from the pre-production stages onward, and the mise-en-scene and camera movements must be planned around them.

After this setup, the author systematically explores the factors that might influence the storytelling—or merely spectacular—use of DVFx. As we did in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, McClean samples a large number of films, 500 including shorts. Any film using DVFx, however unobtrusively, qualified.

On this basis, the author has distinguished eight types of DVFx usage. Documentary is one, as in films where computer reconstructions of ancient buildings are shown. Such usage comes into films when information is presented as part of the mise-en-scene, as with the educational film that is screened in Jurassic Park. The second type of DVFx usage, Invisible, is fairly self-explanatory. We are not supposed to notice when buildings are extended, clouds are added to skies, or smudges on actors’ faces disappear.

Seamless DVFx are those we know must be faked, even though the results look photorealistic. The recreation of ancient cities, as with Rome in Gladiator or giant storms, as in Master and Commander, are of this type. Exaggerated effects involves actions or things posited to be real but created in a stylized fashion. McClean cites the comic effects in Steven Chow comedies, and puts wire-erasure for stunts into this category. I assume The Hudsucker Proxy would be another instance.

Fantastical DVXs obviously involve impossible beings like dragons, cave trolls, and a wide variety of X-Men. McClean also finds them in non-fantasy, non-sci fic films like Forrest Gump, Big Fish, and Hero. Surrealist uses of effects can include mental representations, as in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and American Beauty, or a bizarre but objective world, as in Amélie.

Finally, there are New Traditionalist uses of DVFx, exemplified by Pixar’s films, and HypeRealist ones, like Final Fantasy.

Armed with this typology, McClean studies various approaches to film studies, testing what each one reveals about the use of DVFx. Since classical Hollywood cinema is based on character traits and goals, she begins by showing convincingly how DVFx can “establish, realize, and enhance” character. For example, films often use effects to put the protagonist in greater danger than would be safe to do in reality. The staged fights in Gladiator, the author argues, create a greater emotional engagement with the main character and make plausible the heroism that allows him to defeat his enemy in the end.

Next McClean tests how DVFx can change the impact of a film by analyzing a pre-digital film and its remake in the computer age. (As a method, this is similar to what David does in The Way Hollywood Tells It when he examines framing, editing, and other techniques in the two versions of The Thomas Crown Affair.) The case study chosen is the 1963 Robert Wise version of The Haunting and the Jan De Bont remake (1999). McClean presents considerable evidence that the inferiority of the later film has nothing to do with its expensive DVFx supernatural effects. Instead, she locates the problem partly in the removal of all the creepy ambiguity of the earlier version. De Bont also changes the heroine from a guilt-ridden, virtually suicidal woman (too wimpy in this politically-correct age?) to a strong, determined savior. The result is a conventional super-woman versus evil monster film where the digital effects stand out simply because the original story was stripped of its most intriguing elements.

McClean moves on to genre, an important subject given the apparent concentration of DVFx (the ones we notice, that is) in fantasy and sci-fi films. She rightly points out, “For all the many assertions that special effects are an emerging narrative form, no one has proposed the narrative structure that this new form demonstrates.” The author makes up for that lack herself, concocting an outline of a film based around a string of effects-laden action scenes. Her outline fits the descriptions of films as given by proponents of post-classicism. The result, however, doesn’t resemble any film I’ve ever seen.

In the genre chapter McClean uses an obvious research resource, but one that the post-classicists largely ignore. She has gone through the entire run of the special-effects journal Cinefex, on the assumption that the films it covers are those assumed to be most significant in terms of their DVFx. McClean lists the 291 films by genre, showing that sci-fi films and horror do not have a monopoly on DVFx. For example, thirty-three period and dramatic movies feature in her list.

To gauge the impact of the rise of franchises in modern Hollywood, McClean surveys the four Alien films, which begin in the pre-digital and move into the digital era. As with remakes, the author demonstrates through analysis that the decline in the series after its two first films had to do with a thematic shift and a change in the character of Ripley.

McClean does not overlook the auteur theory, tracing the work of Steven Spielberg during that same transition from pre-digital to digital cinema. Unlike the other effects-oriented giants of Hollywood, George Lucas and James Cameron, Spielberg has worked in many genres. As soon as DVFx became available, he used them in nearly all the ways listed in McClean’s typology, from the Invisible creation of the swooping airplanes in Empire of the Sun to the Exaggerated in the Flesh Fair setting in A.I. to the Fantastical Martians in War of the Worlds. Always in the service of the narrative.

Along the way McClean offers a number of astute observations. One of these is a novel argument against the “DVFx equals non-narrative spectacle” position. She points out that “In many instances technically weak DVFx will be forgiven if they are narratively congruent; it is the strength of the narrative that will carry them, rather than the other way round.” This claim is plausible when we consider how in the pre-digital age we tried to overlook the obvious back-projections and matte-work in Hitchcock films like The Birds and Marnie.

She also suggests some plausible reasons why bad films might be heavy with DVFx. In some cases the effects create a publicity hook that makes up for the lack of other production values. In others, an inexperienced director, carried away with the “cool” possibilities of DVFx, uses them to excess.

And finally someone has come out strongly against the use of the term “cinema of attractions” to describe modern films. Historian Tom Gunning originally coined this phrase in describing very early cinema, where magic acts with stop-motion disappearances and elaborately hand-colored dances were as common as narrative films. For that period, the label worked and was useful. Applying it to later eras just because films have spectacular sequences has rendered the term much less meaningful.

One thing that I particularly like about McClean’s book is that she shows respect for the films she discusses. She actually seems to enjoy both watching and writing about them. McClean asks questions of aesthetic import, and she treats films as artworks—some good, some bad, but all to be taken seriously as evidence for her case.

Her final chapter provides an excellent conclusion: “While DVFx have completely reequipped the storyteller’s toolbox, they have not rewritten the storyteller’s rulebook entirely.” Yes, classical cinema lives, and Digital Storytelling provides vital new evidence to bolster that claim.

(1) In Film Art, we have touched on this range in the section “From Monsters to the Mundane: Computer-Generated Imagery in The Lord of the Rings” (pp.249-251 in the 7th edition, pp. 179-181 in the 8th). McLean treats the topic in far more depth.

Weather Bird flies again

Road to Morocco.

From DB:

On one shelf, close to my desk, I keep books of essays that have satisfied me across the years. Lined up across about four feet, these remind me of the virtues of critical prose. Shaw, appropriately I suppose, sits on the far left, followed by Dwight Macdonald, Jacques Barzun, Gore Vidal, Robert Hughes, Christopher Hitchens, Frederick Crews, Kenneth Tynan, Susan Sontag, and a few others. Picking up any of these and rereading an essay pushes me to try to write more pungently and think more clearly.

I know nothing about jazz, but decades ago I enjoyed reading Gary Giddins’ Weather Bird column in the Village Voice. Then I picked up his 1992 essay collection, Faces in the Crowd and immediately he won a place on my shelf. His buoyant essays are compulsive reading. His piece on Jack Benny, “This Guy Wouldn’t Give You the Parsley Off His Fish,” kicks off the volume, and I think it’s a masterpiece. After reading it, you want to watch a string of Benny TV shows. It’s followed by another triumph, Giddins’ dynamic case arguing that Irving Berlin more or less invented American entertainment. This brace of pieces is just the start. As you’d expect, Giddins spends time on musical greats, from Billie Holliday to Larry Adler, but he shows a fine range, discussing Spike Lee, Robert Altman, Myrna Loy (in an essay titled “Perfect”), and writers from Faulkner to Elmore Leonard.

In an era when journalistic criticism is identified with either puffery or deflation, Giddins is the master of unabashed, admiring appreciation. His judgments are balanced, but he almost never resorts to the swordthrust beloved by his mentor Macdonald, who wrote some of the funniest and most insulting passages in all of American film criticism. You sense that if Giddins dislikes something, he’d rather not write about it. The French call it “the criticism of enthusiasm.”

When he likes something, he can merge dissective intelligence, subtle distinctions, and unfussy prose as very few writers about the popular arts can. Not for him the turbocharged syntax and hyphenated adjectives of fanboys. One word or phrase does the job. Watch how he brings Jack Benny before us, linking him to a tradition of comic types that is even echoed in the turns of the sentences:

The character he created and developed with inspired tenacity all those years–certainly one of the longest runs ever by an actor in the same role–was that of a mean, vainglorious skinflint; a pompous ass at best, a tiresome bore at near best. To find his equal, you have to leave the realm of monologists and delve into the novel for a recipe that combines Micawber and Scrooge, with perhaps a dash of Lady Catherine De Bourgh and a soupçon of Chichikhov; or better still, a serial character like Sherlock Holmes, who proved so resilient that not even Conan Doyle could knock him off.

Benny as Micawber plus Scrooge: perfect. At near best: perfect. And if you worry that “a soupçon of Chichikhov” teeters on pretentiousness, the “knock him off” at the end makes the sentence snap shut, reassuring you that Giddins writes in that American demotic which is our birthright.

The Benny essay is reprinted, justly, in Giddins’ 2006 collection Natural Selection: On Comedy, Film, Music, and Books. This book is twice as long as Faces in the Crowd, and it’s a feast. We get fine pieces on Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and the Marx Brothers, and sensitive celebrations of Antonioni, Lang, Doris Day (he loves her), and Harold Lloyd, along with in-depth studies of many classic films. “Cowardly Custard,” a sketch of Bob Hope, rises to the level of the Benny apologia. If you don’t rush immediately to see a Hope film after reading it, you’re not the man or woman I think you are. I turned to The Ghost Breakers and was rewarded with the moment when Hope peers around a pillar at Paulette Goddard and asks with a hesitant leer, “Am I protruding?”

The Benny essay is reprinted, justly, in Giddins’ 2006 collection Natural Selection: On Comedy, Film, Music, and Books. This book is twice as long as Faces in the Crowd, and it’s a feast. We get fine pieces on Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and the Marx Brothers, and sensitive celebrations of Antonioni, Lang, Doris Day (he loves her), and Harold Lloyd, along with in-depth studies of many classic films. “Cowardly Custard,” a sketch of Bob Hope, rises to the level of the Benny apologia. If you don’t rush immediately to see a Hope film after reading it, you’re not the man or woman I think you are. I turned to The Ghost Breakers and was rewarded with the moment when Hope peers around a pillar at Paulette Goddard and asks with a hesitant leer, “Am I protruding?”

Lucky for us that The Perfect Vision, The New York Sun, and other venues have opened their doors to Giddins’ film writing. (For a sample, along with lots of other material, visit his site.) Although he occasionally scolds, it’s the criticism of enthusiasm that reigns. When he started to write about jazz clubs, “I could focus on what I admired–on what I wanted you to admire or at least know it existed.”

In his music criticism and biography (the wonderful Bing Crosby life Pocketful of Dreams), Giddins interweaves technical details, anecdotes, and thoughtful commentary. In writing about films he does much the same, blending observations about form and craft with insinuating evocations of how a movie plays on the screen. Not many film critics today would notice how the first shot of Lloyd’s masterful Girl Shy unobtrusively sets up its climax. He writes of The Letter:

From the opening nighttime pan of a rubber plantation, interrupted by a gunshot and fluttering cockatoo, and finished with an inexorable closing in on Better Davis, who has followed her victim on to the verandah and pumped five more bullets into him, you know you are in the hands of ardent filmmakers and can only hope that they sustain the inspiration for another 90 minutes. They do.

Or this:

Eyes without a Face begins with a lengthy traveling shot, as Alida Valli races through the night with a crumpled corpse in the backseat, enclosed by an endless line of skeletal trees and accompanied by Maurice Jarre’s funhouse score–imagine Philip Glass programming a carousel.

Giddins has an unapologetic respect for African American performers in studio movies. Of Ivie Anderson’s “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” in A Day at the Races, he notes:

This scene was cut from TV for years and decried as racist by sensitive white liberals. They are free to skip it; the rest of us can head straight for DVD chapter 22 to see Anderson in clover. Racism manifested itself less in Catfish Row stereotypes than in the failure to cast her in other movies.

On Sammy Davis Jr. Giddins mixes sober praise with sorrow:

Davis had once been renowned as a performer of spectacular gifts who could do everything. Sadly, “everything” usually proves to be the most evanescent of talents. His early appearances were virtuoso displays of dancing, singing, and mimicry that defied indifference; he would stop at nothing until he brought the audience into his fold. . . . Davis’ besetting sin was not extravagance, philandering, imbibing, or reckless optimism concerning a president. It was trying to live life as if color did not matter. He was a naïf savant.

For Giddins fans who are cinephiles too, there’s a quiet satisfaction in learning from the autobiographical sketch that launches Natural Selection that he started as a film critic for The Hollywood Reporter. Of course he continues to write about music and literature, and his essay on Classics Illustrated comic books will tingle every baby boomer’s spine. Still, by circling back to movies, Giddins shows himself one of the great contemporary American film critics. In his hands criticism finds its justification as subtle, eloquent admiration.

P. S.

The Good German finally made its way to Madison, and so I’ve posted a quick postscript to my earlier blog on the film’s attempt to recapture 1940s film technique. Nice try, but….