Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Hunting Deplorables, gathering themes

The Hunt (2020).

DB here:

I recently participated in a Film Comment podcast with Nic Rapold and Imogen Sarah Smith. It was fun. Yes, The Hunt was involved.

And last month I posted a “blog lecture” for my seminar on Poetics of Cinema. Because it included references to classroom material, I thought it was too insular for general consumption, so I posted it privately. Encouragingly, some of our regular readers wrote to ask about accessing it, so today I’m putting up a more broadly-aimed version. Again, yes, The Hunt is involved.

We like to watch (and listen)

First and fast, some foundations. As Paul Krugman might say, wonkish ones.

Most basically, I’m interested in two questions: How do films work? How do they work on us? The first question, I think, can productively start with filmmaking craft and the norms that filmmakers work with in their historical situation. Within and against those norms, filmmakers create work that blends tradition and innovation. I’m interested in conventions–the conventional side of “unconventional” works, and the unconventional side of more apparently rule-abiding ones. I sometimes say I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

But asking how films work on us has driven me to posit a conception of spectators’ activities. After all, in any art it’s legitimate to try to explain how the design features of a work are shaped to elicit effects, ranging from perceptual and emotional ones to broader effects of comprehension and what I call appropriation. I assume that in every sphere “the beholder’s share” in watching movies is considerable, and active.

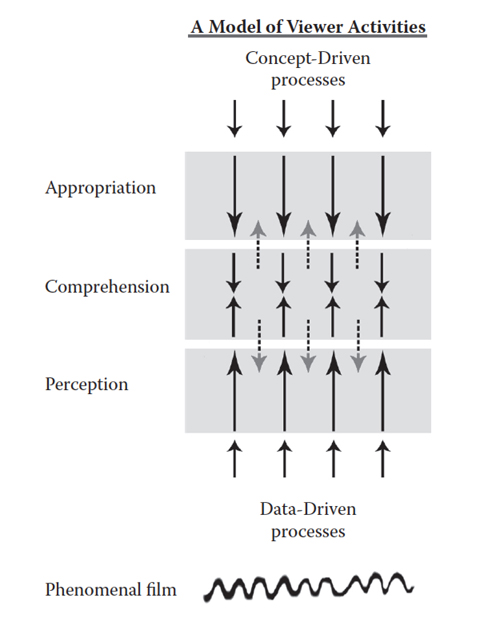

Using a common psychological distinction, I’ve argued we can roughly understand this process with a diagram, above.

The activity proceeds both “from the bottom up” via the fast, mandatory, specialized activities of visual and auditory perception. The process works as well as from the “top down” via more deliberative mental acts. Comprehension, typically of story patterns, operates in the middle. So you “just see” a man in tights walking across the shot. Thanks to story comprehension skills you “just see” Batman striding to face off against a crook. Thanks to your wider conceptual schemes, you can appropriate that as patriarchy in action, or the pain of vigilante justice, or a template for an action figure you might buy, or whatever. Where’s emotion? At all stages, I think.

And all these processes seem to me inference-based to some degree. In grasping artworks, even perception has an inferential dimension, going beyond the information given. Patches and contours on the screen are grasped as people, places, and things; sound waves are grasped as speech and music. The process is inferential because these perceptual conclusions are defeasible, as most illusions are. Things might be otherwise than they seem; we bet (fast, unreflectingly) that things are as they seem until other information pulls us up short. Similarly, story comprehension relies on skills of inference we’ve developed since childhood, built partly upon our social intelligence. And appropriation is obviously inferential, building hypotheses about the meanings and uses we can ascribe to film.

Perception and comprehension are strongly shaped by the film’s form and style. But as we go up from perception, the filmmaker’s power decreases and the viewer’s power increases. Viewers wield most power in appropriation, those top-down, concept-driven inferences that pull the film, or at least the viewer’s construct of the film, into wider projects.

Let’s think of appropriation as most basically using the film for myriad personal or social ends. That activity involves, for want of a better term, themes–ideas, categories, dualities, pop-culture memes, right up to wider beliefs about the world. Cultural processes, affecting the lower levels to some degree, are at work here most explicitly.

At this moment, when many people are sheltering at home, they are appropriating films for many purposes–to distract them, to entertain the kids, to learn more about health policy or the effects of pandemics. Fans, I assume, are seizing the pretext to binge on a saga they love, or check out a series they’ve put off. Online critics, pressed to turn in copy, are mustering their new listicles, recommendations of films to watch while we’re in lockdown.

This situation is just a special case of appropriation, of finding aspects of the film that can be recruited for purposes that may or may not accord with the filmmakers’ original intentions. No producer planned for Outbreak (1995) or Contagion (2011) to serve as audiovisual aids during a plague.

As my Batman example indicates, interpretation is a rich instance of appropriation, displaying how resourceful people can be in their inferential elaborations.

I wrote the book Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema (1989) as an attempt to spell out my ideas. I concentrated on two critical institutions, journalistic criticism and academic interpretation. But I think my claims could be applied to “amateur” critics and fandoms too. (This blog entry on Room 237 gestures in these directions.) Another article on this site, “Film Interpretation Revisited,” is a summary of the book, as well as a reply to critics.

So much for “the beholder’s share.” Can we go back to the “maker”? In a later section I’ll float some ideas about the place of thematics in relation to form and style. I’ll also consider how artists can anticipate and manipulate the appropriation process–a sort of meta-strategy to grab control higher up the chain.

Yes, spoilers for The Hunt are involved.

Interpretation, whys and wherefores

Interpretation seems to me to involve two tasks. First, there’s problem-solving: How should I interpret this film (or show, or whatever?) Second, there’s argument, or rhetoric: How should I make the case that this interpretation is worthwhile? Making Meaning has a lot to say about critical rhetoric, but I’ll concentrate on the problems interpreters set themselves.

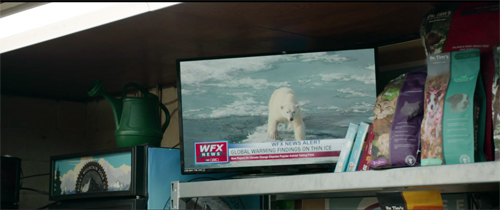

I assume that interpretation ascribes meanings to films. What sorts? I start with referential meanings (a big category including building the story world as well as tapping into real-world information, like specific times and places). In The Hunt, recurring TV images of polar bears struggling on melting ice floes nudge us to remember the climate crisis.

There’s an extra referential layer in the chyron, which expresses Fox-News style skepticism about climate change. That line helps confirm the right-wing ideology that supposedly permeates the quickee mart.

The other sorts of meaning I identify are more abstract. They include explicit meaning, usually given in language. In The Hunt, Athena expresses her disdain for the Deplorables whom she has gathered her friends to kill. She articulates a part of the film’s explicit meaning: The elite treat their social inferiors as prey.

There’s also implicit meaning, suggested through many cues, not just verbal ones. Crystal, the fierce fighter who confronts Athena at the end, is too laconic to speechify, and she never asserts that the underclass can be resilient and pitiless. But we are to grasp that meaning through her behavior–as the prey fighting the predator. Story comprehension feeds our interpretive move. By the end of the film we may take the polar-bear footage as implying that the Politically Correct hunters care more for these beasts than their vulnerable fellow humans.

Referential meaning, explicit meaning, and implicit meaning are typically under the control of the filmmakers. Clearly Craig Zobel, Damon Lindelof, Nick Cuse, and their colleagues want us to make the inferences I just made, along with many others. But it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that some implicit meanings escape the filmmakers. I’ll try to show later that filmmakers sometimes try to back up and frame their films to cover those unintended implications.

We can argue about some of these meanings. In The Hunt, Crystal recalls a childhood story of a race between a rabbit and a turtle. The rabbit lost through laziness, but he took revenge on the turtle by killing him and his family. The tale becomes part of a motif: Early in the film we see a video of a turtle humping a boot, while at the end we see a bunny hop into a gory kitchen.

After telling the story, Crystal declares she’s not sure whether she’s the rabbit or the turtle in the hunt. I think we’re supposed to think about whether the underclass (if it’s the turtle) can ever win more than a temporary victory. This sort of equivocation about implicit meaning is common in artworks. Indeed, the clash of implications encourages us to interpret them. The tactic might seem designed only for “difficult” films, but it’s surprisingly frequent in mainstream movies, as I’ll suggest later.

A fourth sort of meaning, I think, is what people have come to call symptomatic meaning. Here the film says more than it intends. It reveals, like a psychoanalytical symptom, an “unconscious” problem with the explicit and implicit dimensions put forth. (This is the “hermeneutics of suspicion,” which Susan Sontag discusses in “Against Interpretation” in relation to Marx and Freud.)

Critics may say that cheerful Eisenhower-era comedies betray anxieties about gender and identity. Some consider superhero franchises as unwittingly betraying a commitment to fascistic authority. From this perspective, Indiana Jones is less an adventurer than an imperialist. Symptomatic meanings leak out and can’t be contained. If implicit meaning is the filmmaker being more or less subtle, symptomatic meaning works behind the filmmaker’s back.

The Hunt is of course ripe for symptomatic interpretation, as I’ll mention below. However much its sympathies may seem to lie with the prey, it seems unable to avoid double-edged gags at their expense.

For all of these types of meaning, the process I posit is the same. The viewer maps, from the top down, concepts onto cues and patterns found in the film. Given the results of perception and comprehension, the viewer selects certain items to bear the meanings we bring to the task.

For example, I said that Athena articulates the predatory view of the oligarchy. Why did I pay attention to her and her words rather than, say, the layout of comestibles on the kitchen island? Because I have a rough but well-practiced mental schema for personhood. That’s more salient in building up a narrative than spotting bits and pieces of scenery. (These details can become salient, as the cheese-slicer will eventually, but the filmmaker has to make them so, as hand props or in close-ups or whatever.)

Making movies mean (but not like Zahler does)

The information in a film is most simply a flow of images and sounds. Perceptually I go beyond that information to recognize a person. Given that my person schema is furnished with properties like beliefs, desires, consciousness, and so on, I can build up a sense that Athena is stating her views on late capitalism.

Similarly, my repertoire of person schemas enables me to build up a sense of Crystal’s character, based on her appearance, speech, and actions. She too has beliefs (she’s being hunted), desires (she wants to survive), plans (she will fight), and attitudes (she scorns the sissified elites). She has character traits. In certain relevant respects, she’s like us and the people we know.

Filmmakers are practical psychologists. They know, from having consumed films as well as made them, how to highlight information and make it vivid and salient, so that we’ll lock in our concepts easily. For lots of reasons, we’re interested in other people, so that gives film artists an immediate purchase on using characters and their actions to convey abstract or general meanings.

For symptomatic interpretation, the same process holds. Character recognition and construction will be important for finding the flaws and failings of the film’s primary meanings. Of course, the symptomatic critic may “read against the grain” and look for less salient items that betray the film’s unconscious meanings. The fact that the climactic confrontation takes place in a kitchen could suggest that the filmmakers, for all their flaunting of strong women, are assuming a patriarchal ideology: Woman’s place, even as a killer, is in the home.

And the very end of the film, with Crystal strutting out as a fashionista, suggests that she has bought into the shallow values of the elite.

She’s not leading a revolution but killing her way to upward mobility.

I emphasize character as a site of interpretive elaboration because it’s so central to all critical schools, from fandom and journalism to the upper reaches of Academe. It’s not the only set of cues that get mobilized, though. Small details dropped in can serve too. A jar of Pickled Pigs Lips in a fake quickee mart reveals the sneering disdain of the hunters who’ve set up the display, but some viewers may find that it nudges us to mock trailer-trash taste.

The glimpse we get of the jars before the camera pans away seems to be the sort of cue aimed at “committed viewers,” willing to freeze the frame in playback to look for touches like this.

In Making Meaning, I talk about structural patterns as well, like journeys and character relationships, which prompt us to assign interpretations. There are stylistic cues too–not just the soundtrack with its dialogue and not just written language, but also camera movements, cutting, lighting, and so on. All these can be recruited to bear meanings. Critics often interpret a low angle as conferring power on a figure. Style, at bottom aimed at guiding attention and creating emphasis through the line of least resistance, can sometimes come forward and fill less concrete and fundamental functions–that of suggesting implicit or symptomatic meanings.

To wax wonkish again, Making Meaning suggests that the abstract meanings critics map onto cues are organized as semantic fields,which are in turn processed by assumptions and hypotheses. All that machinery is put into motion through schemas (prototypes and mental models) and heuristics (short-cut reasoning routines provided by social milieu or personal proclivity). The result is a “model film,” the film as interpreted by the critic.

You need lose no sleep over these matters. I simply argue that interpretation is a rational, fairly systematic process of informal reasoning operating within institutions that reward certain activities. Academics reward novel “readings,” while arts journalism does less elaborate versions as well. Even the “male gaze,” though stripped of its Lacanian baggage, has found its way into mainstream criticism (and the film industry).

Themes are memes, sometimes

“Themes come cheap,” I said one night in the seminar, rather flippantly. “They’re practically free.”

What I was suggesting was that themes are often obvious in a way style and overall form aren’t. They rise out at us unbidden. Before people watched The Hunt, they had been alerted to look for certain meanings. Mass media, critics, and the filmmakers had primed us to catch the big ideas the film was laying out.

That’s because films take meanings not only as effects but also materials. Films are made out of images and sounds, but they’re organized through form and style . . . and themes. If we look at it from the filmmaker’s standpoint, themes (like subject matter) can be treated as stuff to be worked on through technique. Like subject matter, they can float “obviously” on the surface, protruding a bit but still tugged by the flow of form and style.

In the Poetics Aristotle posited the category of “thought” as a component of tragedy. This term appears to mean something rather special. “Thought” isn’t what characters in drama think, or even what the playwright thinks. Rather, it’s what the characters say: their efforts to crystallize ideas and feelings in statements. The functions of thought in this sense “are demonstration, refutation, the arousal of emotions such as pity, fear, anger, and such like, and arguing for the importance or unimportance of things.”

The plot, Aristotle says, must create its effects through events and their patterning, “but these must appear without explicit statement, whereas in the spoken language it is the speaker and his words which produce the effect.” Thought in Ari’s sense spells out what action leaves tacit.

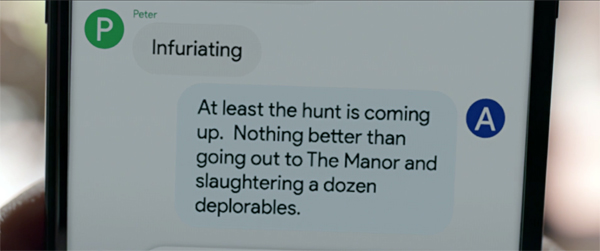

The Hunt does both. Ideas, images, and stereotypes circulating in US society have been taken by the filmmakers as already-fairly-processed material to be reworked into images and sounds and story. The explicit and implicit meanings critics build out from the film are the result of form and style shaping all this stuff into a perceptible, comprehensible experience. At moments, though, the oligarchs and the Deplorables state their sociopolitical views pretty frankly, as in the text message above. As Ari puts it, “they argue for the importance and unimportance of things.” Thought-as-theme is a prime cue for interpretation.

Themes can become not only material but also pattern. Certain genres of narrative are heavily “thematized” in that their organization is based on explicit or implicit meanings. Allegory is a classic instance. The Pilgrim’s Progress has a thematic armature, crystallized in the journey of Pilgrim to the Heavenly City. Ditto Animal Farm, which is usually taken as an allegory of the Russian Revolution. (Interestingly, The Hunt cites Animal Farm.) I expect that right now some grad students are writing papers about The Hunt as an allegory of working-class resistance.

Other heavily thematic genres are parables, fables, and the like. Crystal’s childhood story of the rabbit and the turtle becomes a parable of social injustice.

There are lots of ways that themes provide formal architecture. Some early films, like One Is Business, the Other Crime (1912), depend on thematic contrast. Here the fate of a poor man forced into thievery is juxtaposed with the law’s ignoral of a rich man’s transgressions. (Class resentment didn’t start with The Hunt.) Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) tries for a four-way thematic comparison/contrast of prejudice through the ages.

We also have “social cross-section” films, where stages of the narrative enact encounters with various institutions. As critics have noted, in The Bicycle Thieves(1948), Ricci’s search for his stolen bike brings him into contact with the labor union, the government, the church, and the bourgeoisie–none of whom are of help. A similar cross-sectional dynamic suggests social critique in Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu (1952) and Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960).

Granted, in such modes, the film’s thematic skeleton can seem obvious. Other films leave meaning more free-floating, and even allegories can be less clear-cut than they may seem. (Think of Kafka.) I just want to signal, for the sake of comprehensive coverage, that filmmakers, like other artists, draw upon abstract ideas and meanings as materials to be reworked by their art.

To be good critics, we ought to be aware of both the materials and the transformations that come from them. I suggest this in a piece I’ve flagged before, “Zip. Zero. Zeitgeist.”

The filmmakers fight the power (of viewers)

The filmmaker’s power wanes as we move toward appropriation. But not completely. Filmmakers can use themes to manage a film’s reception.

For example, the Russian Formalist literary theorists floated the idea of the “biographical legend.” This is a public version of the artist’s life that can guide interpretations of the work. Boris Eichenbaum suggested that the Americans had one biographical legend for O. Henry, but the Russians built up a different one.

Critics and commentators build up the biographical legend in order to support interpretations, but the artist can contribute to the process. When Christopher Nolan tells us that as a youth he loved Star Wars, noir movies, and experimental fiction, he’s inviting us to put his own “intellectual blockbusters” in a certain perspective. He’s flagging certain cues, inviting certain mental sets, coaxing us toward certain inferences.

It’s not news. Contemporary critics took Douglas Sirk’s 1950s melodramas as glossy reflections of the superficial values of Eisenhower America. But when he was interviewed by Jon Halliday, he presented himself as offering a Brechtian critique of those values. Later critics eagerly started scanning the films for narrative and stylistic cues that suggested implicit meanings that subverted the suburban bourgeoisie. Chabrol, typically jaundiced, put it this way:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics with their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, not knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want.

If critics can use the artist to interpret the film, why can’t the artist use the critics to steer us toward preferred interpretations?

It isn’t just the filmmaker doing this. Auteur personas created by the filmmaker, the industry, and critical discourse can be seen as pushing us toward certain thematic interpretations.

Now to finish with a point I suggested above. It’s often in a filmmaker’s interest to avoid consistent and clear presentation of themes. I’ve come to think that many ambitious Hollywood films are systematically ambivalent about what they are “saying.” Rather than make a weighted, compact statement of “thought” in Ari’s sense, they scuttle and shuttle between alternate thematic possibilities. Or rather, they shuffle several disparate “thought” statements to counterbalance one another.

This has many benefits. It can stoke controversies. Is The Dark Knight in favor of vigilantism, or does it celebrate anarchy, or does it hold out hope of noble self-sacrifice? Nolan says:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Another benefit: If someone objects to one piece of thematic material, you can always say, “But look, we offset that with this…” It’s a way of widening the film’s appeal to many lines of thinking, while marketing the film as complex.

The creators of The Hunt claim to have aimed the film at smugly woke people like themselves in an effort to humanize the Other.

So we heightened the reality as much as we could. Some of the people who are being hunted are literally the guy with the tiki torch or a guy posing next to a dead animal; they’re two-dimensional stereotypical representations of what liberals see conservatives as. And then we had to do the same thing with the liberals. But there had to be one character in the movie, the hero who defied the conventions of stereotyping, who when you look at her you basically say, “Oh, she has an accent like this. She wears clothes like this. This is who she is.” And let’s be wrong about her. Let’s let the movie be about the cautionary tale of, here’s what happens when you get it wrong.

I think that the idea the audience wants Athena to be wrong about Crystal is maybe our own interior desire to say, “Maybe I’m wrong about my uncle who I’m screaming at at Thanksgiving. Maybe there’s a little bit more to him than meets the eye. Maybe I’m trying to put him in this specific lane because we have to choose a side, but maybe there’s many sides and there’s a little bit more nuance in the conversation.”

The caricaturing of the woke characters allows woke viewers to recognize the satire (and since woke viewers are likely to be educated, they know that satire exaggerates). Presentation of the Deplorables is exaggerated too, confirming that “There’s many sides.”

But there’s a kink for a symptomatic reading: Crystal may not be an actual Deplorable. We never learn her politics. She has been kidnapped in error, mistaken for a fierce Trumpist with the same name. So again the film manages to have it many ways. “Getting it wrong” here doesn’t mean disparaging a right-winger but rather not knowing whether somebody is right-wing or not. The real conversation is postponed because of a mistake. (No mistakes, no stories.)

I don’t mean to sound cynical about this. Art is opportunistic. We just ought to be aware that filmmakers can make the meta-move, using whatever means they can to close off interpretations that they might not prefer. Ultimately, since appropriation is top-down, they can’t control everything we might ascribe to the film. (See Room 237 again.) But there is a bit of a struggle there. Filmmakers will always try to join and constrain the hunt for meaning in their movies.

There’s a lot more to be said about interpretation, but I hope that readers will find something worth considering here. I may redo other Private seminar entries as public ones when time permits.

Thanks to Nic Rapold of Film Comment and Imogen Sarah Smith for a pleasant discussion. My citation of Aristotle on “thought” is from Stephen Halliwell, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill, 1987), 53. The reinterpretation of Sirk’s melodramas was undertaken in Jon Halliday’s interview book Sirk on Sirk (Secker and Warburg, 1971). The Chabrol quote is from Making Meaning (Harvard University Press, 1989), 210.

Phoenix (2014), one of the Christian Petzold films discussed in the Film Comment “At Home” podcast.

When media become manageable: Streaming, film research, and the Celestial Multiplex

Never coming to the Celestial Multiplex: Liberty Belles (Del Henderson, 1916).

DB here:

A directors’ roundtable in The Hollywood Reporter says a lot in a little.

Fernando Meirelles: This June, The Two Popes was in 35 festivals. Then we were going to have two or three weeks of theaters. And then the [Netflix] platform. I mean, it couldn’t be better.

Martin Scorsese: We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

Meirelles casually omits DVDs, at one point the most rapidly adopted format of consumer media. Yeah, what ever happened to discs? And in what follows, I’ll take issue with Scorsese’s claim that streaming has triggered a revolution. It’s more a case of evolution that issued in a sweeping change, like Engels’ transformation of quantity into quality, or Hemingway’s claim that he went broke slowly, then quickly.

More important, I’ll try to assess the impact streaming has had on what Kristin and I and other researchers and teachers try to do–study film as an art form in its historical dimensions.

Managing your time, and your movies

If we’re looking for a revolutionary turning point, I’d suggest the moment that movies no longer became appointment viewing. When they played theaters you had limited access. The film was there for only a while (even The Sound of Music eventually left) and you had to watch it at specified times. On broadcast TV and cable, the same conditions applied. But with the arrival of consumer home videotape in the 1970s, the viewer was given greater control.

Akio Morita of Sony called it “time-shifting.” The phrase, shrewdly positioned as a defense of off-air copying, captures a fundamental appeal of physical media. You could watch a film at home, and whenever you wanted to. Yes, VHS and even Beta yielded shabby images and even worse sound, but (a) theatres were often not much better, and (b) a video rental was cheaper than a movie ticket. Most important was a general rule of media technology: For the mass market, convenience trumps quality.

Videotape swept the world in the 1980s and gave films an aftermarket. Many an indie filmmaker could get financing for a project on anticipated tape sales. The laserdisc gained some attention in the 1990s, becoming a sort of transitional format. It improved quality (better analog picture, digital sound) but had drawbacks too. A movie wouldn’t fit on a single disc side, and a laserdisc was pricier than tape. LD remained a niche format, chiefly for educators and home-theatre enthusiasts.

The laserdisc was superseded by the DVD, introduced in 1996. Journalists claimed that it enjoyed the fastest consumer takeup in electronics history. Discs were more convenient than tapes, and proof of concept had been provided by the success of CDs for music. To compete, cable companies introduced “video on demand,” a time-shifting compromise between scheduled cable delivery and rental of tape or disc. People still use cable VOD, and for some purposes it’s a cheaper alternative to committing to subscription services.

Reviewing The Irishman, a critic suggested that most people will skip seeing it in theatres and watch it on Netflix, where it’s “more manageable.” With tape and disc, either analog or digital, consumers became accustomed to a huge degree of manageability. They could pause, skip ahead or skip back, race fast-forward or –back, play slowly, and above all play the movie over and over. DVDs made all these options quicker and more convenient than tape had. The market boomed. Video stores made discs available for rental, as tapes had been, and retail stores offered them for sale, at increasingly low prices.

But there were problems. In the 2000s there was a glut of DVDs, and consumers began to realize that a few weeks after release many titles would end up in the bargain racks. A brisk secondary market developed thanks to the US “first sale” doctrine, most virtuosically exploited by Redbox. Worse, there was piracy. Pirating analog tapes degraded quality across generations, but with digital discs you could rip perfect clones. Any teenager could hack past region coding and anticopying software.

The Blu-ray disc was an improvement on the first-generation DVDs, and it came along as more people were buying widescreen and high-definition home monitors. Properly mastered, Blu-ray discs looked good, and they had bigger storage capacity. Some consumers got excited, but the improved format couldn’t arrest the headlong decline of disc sales. In addition, the industry’s rationale for Blu-ray was its resistance to rippng, but hackers breached the codes with ludicrous speed.

From this angle, streaming is parallel to digital theatre projection : a new phase in the war against piracy. Likewise, as in theatrical screenings, you’re paying for an experience, not an item. You’re not buying an object you can copy or resell. If a movie is available only on streaming, you’re renting something, not owning it legally. One aspect of manageability—personally possessing a movie—is traded away for convenience and, ultimately, for limited access, as I’ll try to show.

Not so gently down the stream

With streaming, the age of appointment viewing seems more or less over. And the infinite vista of the Internet has encouraged tech-heads to imagine something like the Celestial Jukebox, a vast virtual multiplex in which all movies will be available. If iTunes and Spotify did something like this for music, why not cinema?

Let’s consider the pluses and minuses of streaming for ordinary consumers and for filmmakers.

Obviously, there’s convenience. After the monstrous tape cassettes, DVDs looked adorably slim. Now, gathering in slippery stacks, they have their own sinister aura. With streaming, there’s no need to run out to the video store or to buy new shelving to support a bulging library of discs.

There’s also price, compared to either theater tickets or cable fees. From $6.99 per month (Disney+) to $12.99 (Netflix), streaming services promise to provide TV and movies quite cheaply. And there’s the range of choice, which even on second-tier streamers exceeds the capacity of most towns’ video stores back in the day. Finally, there are many obscure films lurking in the corners of most streamers, so the joy of discovery is still there to a degree.

On the minus side, there’s one that gets the most press—the further erosion of “the theatrical experience.” Critics emphasize the pleasures that come from being in an audience, but this always seems to me overrated. More valuable to me are the scale of image and sound you get in a theatre. I like my movies to loom.

Above all, there’s a virtue in the lack of manageability. In the theatre you can’t pause the movie or run back or skip ahead. You can close your eyes, look away, or leave, but at bottom you’re there to turn your sensorium over to the filmmaker, to go through an experience you don’t control. This unshakeable grip on your attention yields some of cinema’s most powerful effects.

The condition of privatized viewing isn’t unique to streaming, of course. Nor is another drawback, that of the cyclical expiration and refreshing of “content” on streaming platforms. Admittedly, we’re warned. Newspapers and websites run alerts notifying us when a title is leaving a service—perhaps for a little while, perhaps longer, perhaps forever. And this situation is a bit like DVDs’ going out of print. But at least some disc copies exist to be sold second-hand or cloned as files. In working on my book on the 1940s, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I could track down arcane titles on out-of-print discs, and at fair prices. When something not on disc leaves streaming, how do you access it?

I think there will be some pushback when subscribers learn about the costs that more and more services are tacking on. Yes, with Amazon Prime for $119 per year you get access to many films, along with other services. But for a great many films Amazon demands an extra rental fee and very short-term access. Within Amazon, there are channels (Britbox, HBO Now, Starz, Cinemax et al.), all of which demand further subscription payments. As people start to realize that streamers will have exclusive licenses for titles, they’ll feel pressure to subscribe to many services. Here, as elsewhere, the total streaming price tag starts to look like cable fees. Even the New York Times has noticed.

Another problem won’t bother most consumers, but it does matter. A streamed title will occasionally be in an incorrect aspect ratio. Most commonly, a Scope (2.39 or so) image will be cropped to 1.85. I noted this some years back, relying on a website showing faulty Netflix transfers, but that site seems to have been taken over by … Netflix itself.

Netflix will say, with all “content providers,” that they get the best material they can from their licensors. I don’t watch streaming enough to know how common wrong aspect ratios are, but if you know of examples, I’d like to hear.

Finally, even streaming companies can collapse. Unless Apple buys a studio (Lionsgate? MGM? Columbia?), it must rely on original content, and it could well flop. On the day I’m writing this, one hedge fund manager predicts we have reached peak Netflix. Given greater competition, slower growth, and accelerating cancellations, he maintains that Netflix is on the wane. If it scales back or fails (it currently carries $12.43 billion in debt), what will happen to its licensed material and its original content?

What about creators? Filmmakers, especially screenwriters, have enjoyed boom times. It may be a bubble, with over 500 scripted series available on broadcast, cable, and streaming. Still, it has given everyone a lot of opportunities. Documentary filmmaking in particular has enjoyed a shot in the arm.

And features are still doing quite well, at least on Netflix. Of the streamer’s top 10 releases in 2019, seven were features. But those proportions may change. Aside from big theatrical movies licensed from the studios, the impact of proprietary “event” programming (War Machine, Bird Box) has been fairly ephemeral. (Obviously Roma and The Irishman are exceptions.) The strength of streaming, it seems to me, is the same thing that sustained broadcast TV: serial narratives. Hence the popularity of Friends and The Office, as well as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black.

Like network TV, a streamer needs a reliable, constant flow of content—not only many shows, but many episodes. The model of the series, if only in six or eight parts, secures the loyalty of the viewer for the long term. Even if all episodes are dumped at once, the promise of continuation after an interval of a year or several months keeps the viewer willing to hang on till the next season.

The pressure on the creators is predictable. Since form follows format, writers and producers will be pushed to come up with series ideas. A friend of mine pitched a feature-length movie to a streaming service. The suits loved the idea but wanted it as a series and were already scanning the script outline for a plot point that could launch a second season. Some of the streaming series I’ve seen, notably Errol Morris’s Wormwood, seemed to me stretched.

If a filmmaker lands a feature film on a streaming platform, other problems could follow. We’re well aware that independent filmmakers gain few royalties from streaming; their big check tends to be the initial acquisition. At the same time, they can’t be sure that people are watching their entire movie. My barber couldn’t stick with The Irishman, even with pee breaks.

Streamers seem to have accepted grazing as basic to the viewing experience. For purposes of measuring total viewership, Netflix counts a “viewing” of a film or program as a minimum of two minutes. In the light of the two-minute rule, we might expect filmmakers to crowd their opening scenes with plenty to grab us. That goes back to TV and TV-influenced films, of course, which tried to have a strong teaser even before the credits. Now, it turns out, streaming pop songs are being crafted with shorter intros and earlier choruses “to get to the good stuff sooner.” Maybe filmmakers will be trying the same thing. Maybe they already are.

Streaming and film research

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018).

Finally, what are some consequences of streaming for researchers, educators, and your all-around obsessive cinephile?

I think it’s fair to say that home video, in the form of tape, laserdisc, and digital disc, democratized film study. From the late 1960s on, I traveled to archives and film distributors to watch films for my research. It was troublesome, time-consuming, and costly. As a grad student I took a bus from Iowa City to Chicago to watch 16mm prints of Dreyer and Sontag films. I drove to Eastman House to see films in projection. I stayed in Paris a couple of months to work at the Cinémathèque Française on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse.

As a prof here at Madison I spent hundreds of hours watching prints in our Center for Film and Theater Research. Over the decades I trekked to Denmark for Dreyer and 1910s films, to Japan for silent films, to Paris and Munich and the BFI and MoMA and UCLA and Eastman House and the Library of Congress, and above all Brussels for many, many projects. Collectors, from Manhattan, Tokyo, and Milwaukee helped as well. Kristin and I owe archivists everything.

The terrible quality of films on tape didn’t help me study visual style, but laserdiscs were a big improvement. (Hong Kong films tended not to be in Scope on tape but were on LD.) And one LD format, CAV, was frame-accurate; you could study a shot frame by frame, something not possible with many DVDs. There’s always a trade-off with any technology.

Even after even after DVDs arrived I kept up my travels. I could use discs for bulk background viewing, but often I still had to rely on prints. Sometimes I wanted to count frames (handy in looking at Soviet montage and Hong Kong action). Moreover, looking at film prints revealed that the color palettes on DVDs could be quite different, and soundtracks were often cleaned up for the home market. And of course thousands of films, especially from outside Hollywood or in the first decades of cinema, were never going to be available on consumer video. My most recent extended archive stay, in Washington in 2017 thanks to a Kluge Professorship, showed me the glories of the 1910s in prints that are mostly accessible only to researchers.

What do scholars of an analytical bent need? Entire films that can be paused. Frame stills, made photographically or through software. Clips as evidence for our claims. Stills and clips are our equivalents to quotation for literary scholars and illustrations for art historians.

Apart from convenience and cost savings, the disc revolution yielded something I couldn’t get otherwise. In an archive, it’s impossible to study film-based 3D cinema. But thanks to Blu-ray, I can stop on a 3D frame. (. . . And, for instance, spot the way Hitchcock makes the clock quietly pop out in Dial M for Murder, below). This is a unique benefit—but a waning one, as 3D discs are increasingly hard to find and 3D monitors scarcely exist any more. As I said, trade-offs.

From this standpoint, Netflix and its counterparts offer a step down from DVD and Blu-ray. In terms of choice, many films aren’t currently available on streaming, and many more never will be. You can pull a DVD off a shelf whether you’re online or not, but for streaming you need a good connection. The controls of a streaming view aren’t as precise as those on a DVD player; slow forward and back to study cuts and gestures aren’t feasible, it seems.

When cable cropped films, as it frequently did, you had recourse to DVDs, perhaps even from foreign sources. But as exclusive licensing increases, only one service will have a title. Frame grabs are possible with some software, but clips are more difficult.

Worst of all, many worthwhile films will apparently never find their way to disc. I first noticed this in 2017 when I wanted to buy a copy of I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, a Netflix release of a Sundance title. As far as I can tell, it’s not available on DVD. The same fate has befallen one of my favorite films of 2018, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only a few years ago it would be unthinkable for a Coen Brothers film not to find DVD release. Even Roma has had to wait for a Criterion deal to make it to disc. Clearly Netflix, and perhaps other streamers, believe that putting films on disc damages the business plan. So Meirelles doesn’t include DVDs in the lifespan of The Two Popes.

Without DVDs, some cinephiliac consumers are lamenting, rightly, the loss of bonus materials. The Criterion Channel has been exceptionally generous in shifting over its supplements to the streaming platform, but other companies haven’t been. Scholars and teachers rely on the best bonus items, including filmmaker commentaries, to give students behind-the scenes information on the creative process. There are, I understand, rights issues around supplements, and bandwidth is at a premium, but there’s no point in pretending that the loss of disc versions hasn’t been important.

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas put forth the question debated in the directors’ roundtable I mentioned: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

Still, the big changeover hasn’t happened quite yet. Every year has its failed blockbusters, and films big and middling and little (Blumhouse, for instance) still continue. Arthouse theatres, which rely on midrange items, indie production, and foreign fare, are putting up a vigorous fight, emphasizing live events and community engagement.

Meanwhile, streaming makes film festivals and film archives more important. Festivals may host the few plays that a movie gets (as in the 35 fests which ran The Two Popes), and filmmakers, as Kent Jones remarks, are eager for their films to play on the big screen in those venues. Archives will need not only to preserve films but also make classics and current movies available in theatrical circumstances. Smart film clubs like the Chicago Film Society and our Cinematheque keep film-based screenings alive.

Before home video, few film scholars undertook the scrutiny of form and style. Those who did had to use editing machines like these. (One scholar called my study of Dreyer, not admiringly, the first Steenbeck book.) Ironically, just as an avalanche of films became available for academic study, and as tools for studying them closely became available for everyone, most researchers turned away from cinema’s aesthetic history and a film’s specific design in order to interpret their cultural contexts. There were exceptions, like Yuri Tsivian’s efforts to systematically study patterns of shot length, but they were rare.

Whatever the value of cultural critique, one result was to leave aesthetic film analysis largely to cinephiles and fans. Thankfully, the emergence of the visual essay, in the hands of tech-savvy filmmakers like kogonada and Tony Zhao and Taylor Ramos, eventually attracted academic attention. Film analysis has returned in the vehicle of the video essay, which is a stimulating, teaching-friendly format. Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have participated in this trend through our work with Criterion and occasional video lectures linked to this site.

All this was made possible through the digital revolution, or evolution, and we should be grateful. Still, streaming filters out a lot of what we want to study. It’s clear that, for all their shortcomings, physical media were our best compromise for keeping alive the heritage of critical and historical analysis of cinema. We’ve largely lost physical motion pictures as a contemporary medium. (How many young scholars, or filmmakers for that matter, have handled a 35mm print?) Now, to lose DVDs and Blu-rays is to lose precious opportunities to understand how films work and work on us.

Thanks to all the archivists, collectors, and fellow researchers who made our research so fruitful and enjoyable in the pre-digital age.

A good overview of the streaming business at this point is “The future of entertainment,” in The Economist.

Kristin discusses the fantasy of the Celestial Multiplex with archivists Schawn Belston and Mike Pogorzelski. For examples of how to watch a film on film slowly, go here. Samples of editing-table discoveries are here and especially in the Library of Congress series that starts here. In another entry, I discuss the use of 3D in Dial M for Murder.

P.S. 24 January 2020: Then there’s this, from Facebook.

Dial M for Murder (1954).

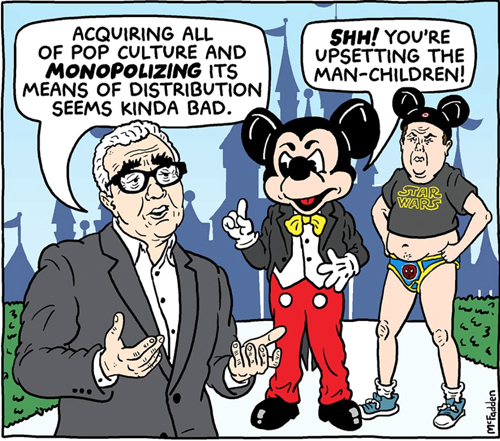

Captain Cinephilia: Scorsese strikes back

Brian McFadden, No One Is Safe: Martin Scorsese Roasts Your Fandom.”

DB here:

It started with a brief, almost offhand remark.

“I don’t see them,” [Scorsese] says of the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe]. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When I learned about this interview (Empire, November issue), I took it as simply a roundabout statement of personal taste. Scorsese doesn’t find Marvel movies, and perhaps other comic-book sagas of superheroes, to his taste. He gave them a fair shot, but he now no longer sees them. He considers them visceral stimulation, like carnivals or theme parks. They’re not cinema, if you consider cinema as emotional expression of psychological conflicts.

In the massive responses to Scorsese, people pointed out that viewers often respond emotionally to superhero films. They root for certain characters, they’re amused or thrilled by certain situations, and many claim to be deeply moved by the heroes and villains (Loki, even Thanos). In fact, it’s exactly the “emotional, psychological experiences” embedded in the Marvel and DC plots that some fans say distinguish them from crude comic-book movies that went before. Much the same could be said of the Bond films, which became more humanized with Quantum of Solace, though intermittently before.

As for the claim that the superhero films “aren’t cinema,” I wasn’t really upset. Over the decades we’ve heard that 1910s films “aren’t cinema” (too theatrical), or that adaptations of novels or plays “aren’t cinema” (too literary or stagebound), or that narrative films “aren’t cinema” (usually proposed by avant-gardists). When the claim relies on a notion of some cinematic essence (editing, or pure visual form) that’s missing from this or that movie, you might be able to have a productive conversation. But if “This isn’t cinema” comes down to “I don’t like films like this,” we’re back to personal taste.

On other occasions Scorsese went on to say a lot more. The ultimate result was a 7 November article in the New York Times. I think we should take this as his most thoroughgoing effort to explain his thinking. We can supplement that with some remarks he made in interviews and Q & A sessions.

Herewith my attempts to figure out Scorsese’s argument. Trying to sort this out might teach us some important things about film now.

Scorsese in defense of Cinema

Scorsese’s Times article, “I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain,” begins by disclaiming any hatred for Marvel movies as such. “The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament.”

But everyone’s taste gets shaped by their moviegoing experience, and in his youth Scorsese was attracted to films from America and Europe. These yielded “revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation.” The films were, he felt, about characters who were complex, sometimes contradictory in their minds and behavior.

Moreover, these films showed that cinema was an art form, one existing in both commercial and more experimental spheres. Hollywood studio output (Ford Westerns, Hitchcock thrillers), European imports (Bergman, Godard), and avant-garde work (Scorpio Rising)—all these showed that cinema had powers equal to those of music, dance, and literature. These films were technically accomplished, sometimes virtuoso, but at their hearts were intense, complex emotional appeals that assured that they would be watched for decades later.

Today the Marvel pictures, often skillfully made, lack “revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger.” They are repetitive, adhering to a basic formula, “defined as variations on a finite number of themes.” By contrast, the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Wes Anderson, and other directors offer new and unpredictable experiences, and they expand the possibilities of the art form. “The unifying vision of an individual artist” is essential to cinema.

It’s exactly the exploratory filmmakers who are being stifled by the Marvel releases, and indeed all the franchises. These more personal films aren’t just constrained by lower budgets; they can’t get much exposure on theatre screens either. “Around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen.” Most filmmakers design their films for that scale and that communal experience, but the blockbuster films are pushing smaller pictures into streaming outlets.

The franchise mentality is a corporate one. The products are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” As often happens, the business constrains the art. But you might say, what about the old studio system? Wasn’t that as mercenary as today’s franchise juggernaut? No, because the studios set up a creative tension between the business end and the artistic end that yielded outstanding works, even masterpieces. Today’s franchise producers are indifferent to art and hold a view of film history that is both “dismissive and proprietary.”

As a result we have two domains: worldwide audiovisual entertainment vs. cinema. They overlap less and less, and it seems likely that the financial power of one will dominate and belittle the other.

I think that some of these arguments are plausible, while others deserve more probing.

Film art: Who’s the artist?

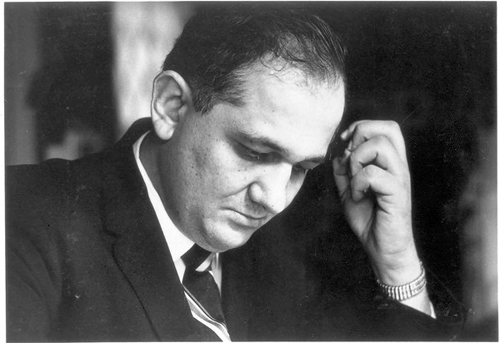

Andrew Sarris.

During the 1950s and 1960s, this general argument was promulgated by the so-called auteur critics around Cahiers du cinéma and was developed and promoted by Andrew Sarris in the US and Movie magazine in the UK. Scorsese was deeply influenced by these ideas. He was one of many cinephile directors-in-training who assumed that the best films bore the “unifying vision of the individual artist,” who was the auteur (author) of the film.

What was considered the “auteur theory” is too complicated to explore fully here. Minimally, it’s the idea that, all other things being equal, in many movies (often the best ones) the director can be considered the source of the film’s distinctive artistic qualities. The director may achieve this by exercising near-total control (e.g., Chaplin), or working with close collaborators (Powell and Pressburger, Donen and Kelly) or serving as a “filter” for the offerings of various contributors (probably most filmmakers).

This is the minimal case. The maximal one rests on the idea that once we make the director the central power, we then discover a “unifying vision.” At this level the distinctive features of form, style, and theme coalesce into a personal conception of human life. For Ford, that might include the value of traditions and the costs they demand of those subscribing to them. Hitchcock’s recurring concern, Robin Wood famously argued, is the realization that complacency, a trust in social order, is vulnerable to disruption.

The difference between the two versions I’m sketching isn’t hard and fast. Still, it often holds good. A friend, for instance, grants that Tony Scott is a distinctive filmmaker. “He just has nothing to say.” The idea that an auteur has something consistent and personal to “say,” deliberately or unconsciously, from film to film, is a hallmark of auteur criticism at its most ambitious. And the greatest auteurs, perhaps, show development in what they say across their careers. John Ford’s attitude toward the frontier can be said to change from The Iron Horse (1924) to Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

The minimalist auteur concept isn’t new. From the 1920s on, historians and critics often attributed creative authority to Griffith, Chaplin, De Mille, Hitchcock, and European and Soviet directors. And in most film industries, executives recognized that the director had the most responsibility for the film’s look and feel.

One revolutionary edge of auteur criticism was to discover auteurs nobody had noticed before–largely unknown filmmakers working alongside humbler folk. And the critics went further, suggesting that some of these filmmakers could be considered auteurs to the max.

Typically auteur critics didn’t examine the concrete context of production to determine who did what in particular cases. They inferred directorial expression by watching lots of films and tracing recurring strategies of style and theme. Sometimes they backed their conclusions up by interviews with–who else?–the director.

Minimal versions of the auteur idea are central to film culture now. Festivals promote directors, as do studio marketers. Movie lists in reference books and search sites give directors the pride of place. Variety and Hollywood Reporter reviews usually don’t name producers, cinematographers, and other contributors, but the director is always mentioned (and blamed or praised for the film). Academics and cinephile critics ascribe more maximalist “personal visions” to directors around the world, from David Lynch and Spike Lee to Wes Anderson to Wong Kar-wai and Jane Campion.

Auteur +genre = ?

Black Panther: Danai Gurira (Okoye), Ryan Coogler on the set.

Despite the prominence of some directors, they’re usually not what draws audiences. In most countries, the mass-market cinema is dominated by genres that are populated by well-known stars.

Sarris and others assumed that auteurs built upon the foundations provided by genre conventions and star images. Ford gave the Western a new force not only through his images and use of music but also by redefining the star personas of John Wayne and Henry Fonda. Hitchcock and Lang worked with and against the conventions of the thriller, while Ophuls gave the melodrama a melancholic elegance. Or so goes auteur gospel.

The 1970s New Hollywood auteurs embraced genre filmmaking as well. Bogdanovich, Coppola, Altman, Woody Allen, and others tested themselves in a variety of genres. Even Scorsese tried a “woman’s picture” (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), a musical (New York, New York), and a biopic (Raging Bull). They are only roughly parallel to today’s indie filmmaker who, after a breakthrough project at Sundance or SxSW, signs on to make a franchise picture.

As a generous and enthusiastic cinephile, Scorsese has long subscribed to a version of auteurism. Perhaps one source of his misgivings about Marvel and its counterparts is that he can’t detect auteurs in these movies. Does that mean they aren’t there? Is today’s studio cinema largely a genre cinema, minus the classic bonus of high-end auteur expression?

One of his comments has attracted little notice. Scorsese remarks of the theme-park picture:

The technique is very well done but there is only one Spielberg, there is only one Lucas, James Cameron. It’s a different thing now.

This implies that even the franchise genres could sustain some degree of what Sarris called “directorial personality.” Admirers of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarock, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, or Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman might agree. This has been one line of defense in the pushback to Scorsese’s comments.

Or maybe we should attribute whiffs of personal expression today to the producers (Bruckheimer, Kathleen Kennedy, Kevin Feige). Even in Hollywood’s heyday, we sense Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun as Selznick productions. Then there’s Walt Disney, surely a producer as auteur. I suspect that Scorsese finds these old films more inspiring than today’s behemoths.

Closing the drawbridge on Fort Multiplex

Avengers: Endgame (2019).

A genre can rise and fall in popularity. As the Western and the musical declined in the 1970s, horror and science-fiction gained traction as both programmers and A-list blockbusters. Add in the rise of fantasy, crystallized in the prestige accorded the Lord of the Rings installments. Oddly, as comic book sales declined, comic-book movies came to be a central contemporary genre. The superhero film proved a powerful blend of all these trends.

Today, the stifling presence of the fantasy/SF/comic-book franchises seems obvious. Look at two snapshots.

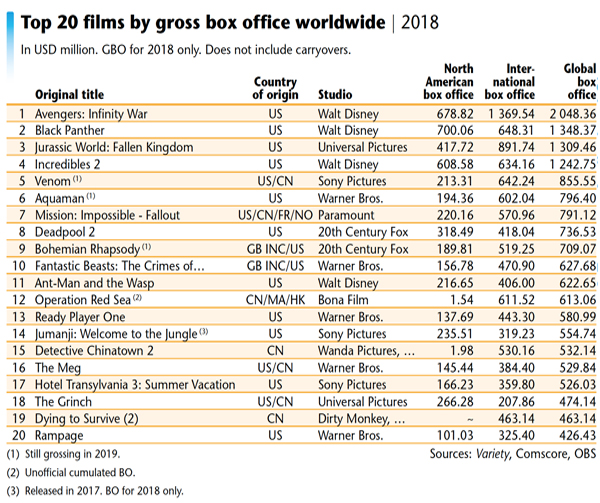

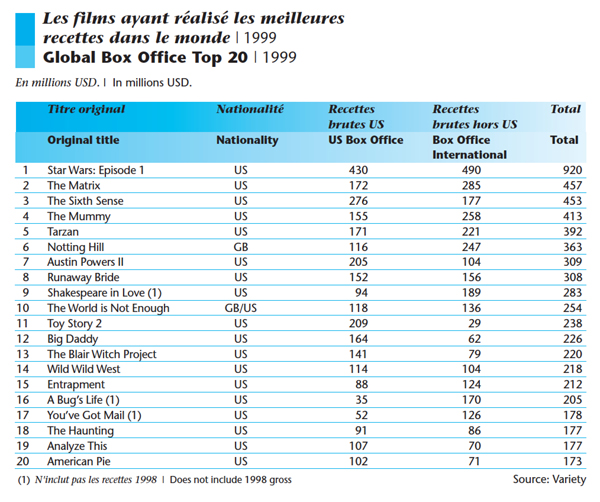

In 1999, the world’s top-grossing film was Star Wars: Episode 1. Among the twenty top hits were fantasy/SF blockbusters The Matrix and The Mummy, as well as a Bond entry. But there were also lower-budget horror films (The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project). Most surprisingly, the top twenty include many comedies, mostly star-driven.

Now consider the 2018 situation.

Five of the global top ten were superhero films. The big winner was Avengers: Infinity War, which earned over two billion dollars globally–nearly twice as much as second-place Black Panther. Among the top ten are Venom, Aquaman, and Deadpool 2. Add The Incredibles as a sixth superhero film if you want. At 11 is Ant-Man and the Wasp. Most of the remaining titles are also franchise entries. There’s also the fantasy/SF blend Ready Player One, the monster movie Rampage, and the action thriller The Meg. Only China is offering live-action comedy (Detective Chinatown 2) and drama (Dying to Survive).

Of course nobody knows better than Scorsese that the big-budget fantasy/SF film has long been with us. His New York, New York (1977) came out the same year as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, while 1980 saw the release of both Raging Bull and The Empire Strikes Back. But in those years straight-up genre films had a fighting chance. Smokey and the Bandit, The Goodbye Girl, 9 to 5, Airplane!, and others won big box-office.

Scorsese films have landed in the top twenty occasionally (e.g., The Color of Money and The Wolf of Wall Street). On the whole, though, I’m not suggesting that Scorsese now sees himself as competing with the biggest grossers. He’s surely right that today’s superhero films dominate the landscape. But do they squeeze out other films to the degree he suggests?

In some venues, probably yes. Small towns with one or two multiplexes may not have space for the minor-key movie. But bigger towns and midsize cities can be quite hospitable to them. In one week, alongside the big releases, multiplexes in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (pop. about 250,000) played Motherless Brooklyn, Jojo Rabbit, Parasite, The Lighthouse, The Current War, Brittany Runs a Marathon, and documentaries on Molly Ivins and Miles Davis. At least some of these qualify as original vehicles. At its widest release, The Lighthouse played on nearly 1000 US screens, and Jojo Rabbit arrived at over 800.

These are merely data points, not systematic samplings. And you might argue that we’re in the middle of Oscar qualifying season, so more offbeat films are numerous now. Okay, go back to July, the most competitive month for domestic releases. Nationally, the big pictures didn’t prevent the release of Yesterday, Midsommar, Late Night, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Booksmart, The Dead Don’t Die, The Biggest Little Farm, The Farewell, The Art of Self-Defense, Amazing Grace, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

Again, not all of these count as auteur vehicles, and several failed domestically, but they still squeezed into multiplexes. The Tarantino film obviously commanded a wide release, but many of the titles I mentioned played on between 1000 and 2000 screens. Booksmart opened on over 2500, Midsommar on 2700.

The industry doesn’t depend on the smaller or more personal titles, but then it seldom has. The biggest box-office successes in the heyday of the studio system were almost never auteur classics. Variety reported that the top domestic hits of 1943 were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Song of Bernadette, This Is the Army, Stage Door Canteen, Random Harvest, Hitler’s Children, Casablanca, Madame Curie, Star Spangled Rhythm, and Coney Island. True, Frank Borzage struck gold with Stage Door Canteen, but it’s not typical of his work. Lubitsch (Heaven Can Wait) and Hitchcock ( Shadow of a Doubt) were far down the list, bested by the likes of Sam Wood, Clarence Brown, and Henry King.

Or take 1952, ruled by The Greatest Show on Earth (De Mille), Quo Vadis, Ivanhoe, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Sailor Beware, The African Queen (Huston), Jumping Jacks, High Noon (Zinneman), and Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly). True, The Quiet Man hit number 12, and Mann’s Bend in the River number 13. But of the top hundred the only other auteur pictures seem to be Pat and Mike (no. 39), Monkey Business (no, 47), Carrie (no. 54), The Lusty Men (no. 76), and Five Fingers (no. 85).

It seems plausible, then, that in Hollywood “audiovisual entertainment” has overwhelmingly dominated the market for decades. Auteurs seldom win the biggest grosses. But again Scorsese’s career history may have influenced his judgment.

There was a moment, the Holy 1970s, when genre cinema with a personal-vision inflection was occasionally lucrative. The Godfather, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Alien, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, and other notably original productions did earn money and awards. Yet in retrospect that seems an interregnum. The top rentals of the following decade, the 1980s, were dominated by Spielberg and Zemeckis. Then there were the usual array of star-driven comedies and action pictures. Genres came back strong, and auteurs had to work within them, or around the edges.

Such is pretty much the case right now. At the top end, perhaps the superhero films are roughly equivalent to the biblical sagas, historical pageants, and theatrical adaptations that roadshowed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Now as then, a number of auteur films are still getting theatrical releases. The blockbusters keep the lights on and the popcorn moving so that theatres can afford to wedge straight-up genre pictures and offbeat indies into their week. It seems that you can’t run Avengers: Endgame on all 22 screens.

Art vs. craft?

Anthony and Joe Russo directing Avengers: Endgame.

But maybe we shouldn’t think of the big pictures as “audiovisual entertainment.” What’s opposed to that? “Cinema,” Scorsese said. I’d propose that this formulation means “artistic cinema.” Which is to say that we’re in the realm of the classic distinction between art and entertainment.

This has given an opening to the people riled up by Scorsese’s remarks. Admirers of Marvel, DC, and comparable pictures can say that they find them as emotional, revelatory, inspiring, etc. as anything he finds in Bergman or Sam Fuller. They feel it in their bones. And who’s to gainsay that? Scorsese doesn’t have their bones, and neither do you or I.

On more objective grounds, I suggest that Scorsese has floated another distinction. Forget calling some things “cinema” and some things not. I think that he’s distinguishing craft from art.

Let’s say provisionally that craft is the skillful manipulation of the medium to produce the desired effects. Art, on this understanding, can be considered something more. It’s usually grounded in craft, but not always. It’s also formally and emotionally complex, original in its relation to what came before, and offering new experiences on repeated exposure (rather than replays of the original response). Many, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, would add that art induces reflection on ourselves and the world, making us wiser and deepening our humanity.

From this angle, Scorsese’s recognition of the “talent and artistry” of franchise films can be seen as a nod to craft competence. “The technique,” he says, “is very well done.” Our blockbusters are comparable to many of those anonymous hits of the studio era, turned out by skillful but impersonal artisans.

In response, the MCU advocates would need to show that the films go beyond craft. For example, some advocates find in these films the kind of character complexity Scorsese attributes to Hitchcock. He finds that Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest suffers “painful emotions” and an “absolute lostness.” Marvel fans will say something like this about moments in the stories of Tony Stark, Captain Marvel, Captain America, and the Winter Soldier.

Scorsese might reply that these are not complex characters. Yet for many years people said the same about the work of Hitchcock and other Hollywood auteurs. When people started to study them, we saw things differently. Only closer analysis of the comic-book films can give us better grounds to argue about whether their characters exhibit the “contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures” Scorsese champions.

Realism and its rivals

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014); Raging Bull (1980).

A few scattered speculations and I’m done.

I don’t know that we’ve fully recognized that these SF and fantasy franchises descend from earlier forms. Silent crime serials and installment films featuring Dr. Gar el-Hama and Judex had the same reliance on secret identities and world-threatening master villains. Chinese wuxia films gave their knight-errants the power to soar into the air (the “weightless leap”) and emit blasts of energy (“palm power”). The bullet ballets of Hong Kong films have obviously influenced Hollywood action pictures, but we haven’t acknowledged how our comic-book movies incorporate fantasy martial arts techniques. Hollywood owes Asian action cinema more than we usually admit.

But the silent policiers and the fantasy wuxia are flagrantly unrealistic. And Scorsese, more than many of his colleagues, is committed to realism. He couldn’t, I think, make Big Trouble in Little China or Kill Bill. I’d suggest he’s intrinsically out of sympathy with quasi-supernatural action. (Hugo is a historical film, and it’s about a sacred era of Cinema past.) Superhero dramaturgy, I hazard, rubs him the wrong way, and not just because it lacks psychological depth.

I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog that Scorsese makes forays into expressionist and impressionist technique, but they usually issue from a base of harsh realism. His commitment to realism may make it hard for him to engage with the more outrageous narrative conventions of the superhero film.

Here another classic dichotomy suggests itself. If you have to choose between basing your story on plot or character, Scorsese will choose character. In fantasy films, though, character motive and reaction are based on elaborate plot machinations. These films depend a lot on elaborate fake identities, as well as recognitions of hidden kinship. She’s my sister! He’s my father! Such devices serve to provide intricate genealogies and networks of relationships for fan homework.

Likewise, theatrical melodrama and adventure fiction from the nineteenth century supply superhero sagas with orphans of mysterious parentage, duels, hairbreadth escapes, family secrets, coded documents, precious but mysterious objects, and other franchise conventions. These are woven into complex schemes and counter-schemes of the sort found in the silent crime serials. But all these features run counter to the psychological conflicts that animate Scorsese’s plots.

Recognitions of kinship rely in turn on a plot strategy that’s worth discussing a little more; I suspect it yields much of the emotional resonance that fans enjoy. These films rely on courtship and romantic rivalries throughout, of course, as well as friendships forged and broken. These are standard for most American genres. But I’ve been surprised at how often family relations are developed in complicated ways.

It’s not just Star Wars. The Marvel Universe relies heavily on kinship to sustain its plots, as well as its pathos. Tony Stark and Pepper Potts have a daughter, as does Scott Lang. Hawkeye has a family, as does T’Challa, whose cousin N’Jadaka becomes a prime adversary. Nebula and Gamora are pressured to be dutiful daughters to Thanos. Thor and Loki share a mother, Frigga. You can argue that Tony Stark becomes a father-figure for Peter Parker. Other characters are more isolated, but for some of them, notably Natasha and Bucky, the Avengers team constitutes a surrogate family.

Marvel’s focus on the family asks us to exercise the skills we must bring to classic mythology, nineteenth-century novels, and TV soap operas. We need to keep track of who’s related to whom, and what in their past encounters can arouse obligations and conflicts. I don’t think that plots resting on such dense kinship relations are of great appeal to Scorsese; his families, when they’re present at all, are pretty small-scale (Raging Bull, Cape Fear, Shutter Island, The Age of Innocence).

Most of all, when Scorsese speaks of these films shying away from risk, I suspect he’d include their avoidance of narrative risk. In fantasy and SF, nobody need really die. Hero, villain, love interest, and sidekick can return in a parallel world, or they can be resuscitated through a new gadget. The worst outcome need not be the worst, as when Avengers: Endgame uses nanotech and time travel to rewrite the past. Plot mechanics again. Despite all the assurances that Tony Stark is really, really gone, we could find a way to bring him back if Downey wanted to sign on again. (Black Widow is being resurrected for a prequel adventure.) But there’s no bringing back Sport from Taxi Driver or Rodrigues from Silence—except in a prequel, another convention that Scorsese would likely disdain.

I’m just spitballing here, but for Scorsese and other stylized realists like Michael Mann, the comic-book convention of eternal return might seem merely juvenile wish fulfillment. Something really has to be at stake, and ultimates must be faced’ Danger and death are real. This is grown-up drama.

I’m not intrinsically opposed to the conventions ruling comic-book movies myself. In general, I think that plot is as underrated as character is overrated. (I’d rather give up the distinction altogether, but that’s another story.) Superhero films are mostly not to my taste, but I think they’re worth studying as intriguing contributions to trends in modern cinema. My point is just that the personal aesthetic of Scorsese, as both cinephile and cineaste, doesn’t fit very well with the elaborate, ever-changing rules of the magical MCU. He finds enough magic in a sinuous tracking shot, or a carefully synced doo-wop song, or an unexpected angle, or a wiseguy shouting match. That is Cinema.

There are other questions we might ask about Scorsese’s remarks. For instance, when he celebrates the thrill of communal moviegoing as a central feature of Cinema, he seems to ignore the fact that the franchise pictures are our prime multiplex attractions. Many viewers slot the more “personal films” into a future Netflix queue, but they commit themselves to seeing the big films on the big screen. That choice can yield contemporary viewers some of the electricity that Scorsese found at a screening of Rear Window. And when they’re not checking their text messages or chatting loudly with their pals, they might even give themselves up to laughs, screams, and applause, just as in the old days.

Since I wrote this, though, something much more draconian than superhero pictures may threaten non-franchise pictures. On Monday, Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim said that the Department of Justice is moving to end the consent decrees that have governed Hollywood studio conduct since 1948. (See here and here.)

The implications of this are staggering. We may see the return of block and blind booking, the prospect that a studio could own a theatre chain (and give favored place to its own pictures), and the decline of independent producers and art houses that favor smaller films. Nonsensically, Delrahim quoted an earlier Scorsese remark about his craft: “Cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Delrahim went on: “Antitrust enforcers, however, were not cast to decide in perpetuity what’s in and what’s out with respect to innovation in an industry.” Thus the ideology of predatory “disrupters” goes on, and even auteurs are unwillingly recruited to the enterprise.

Thanks to Jim Danky for calling my attention to the McFadden comic, and to Jeff Smith for discussions of Scorsese’s arguments. Thanks as well to Colin Burnett for discussion of the Bond saga.

My lists of top-twenty films come from the European Audiovisual Observatory’s publications Focus 1999 and Focus 2019.

I’ve left aside other writers’ analyses of Scorsese’s views. I benefited from reading Ben Child and Helen O’Hara in The Guardian, Christopher Orr’s older review in The Atlantic, and Zachary Zahos at Playback. Also pretty forceful is Kevin Feige’s defense of the MCU, which I discovered only after writing this entry. He argues for Marvel films’ value on several grounds, including their display of positive social values. And just before I posted this, the Russo brothers weighed in.

Here are other Scorsese comments made before the New York Times piece appeared. After his BAFTA David Lean lecture on 12 October, he reiterated his view.

Theatres have become amusement parks. That is all fine and good but don’t invade everything else in that sense. That is fine and good for those who enjoy that type of film and, by the way, knowing what goes into them now, I admire what they do. It’s not my kind of thing, it simply is not. It’s creating another kind of audience that thinks cinema is that. If you have a child and the child wants to see the picture, what are you going to do? It’s up to you. The audience that sees them now, the fans that see those pictures now, they were raised on pictures like that.

The technique is very well done, but there is only one Spielberg, only one Lucas, James Cameron, it’s a different thing now. It’s an invasion, so to speak, in the theatre. . . .

We are in a moment not only of evolution but of revolution, in pretty much the whole world, everything we know, the old political systems, it’s almost as if the 21st century is beginning now and technology has gone with it and that means cinema goes with it.

Yes, see a movie in a theatre, it’s the best with an audience, but the actual concept of cinema has become something that is not definable. Something can play as a hologram, something can play as virtual reality, maybe there is going to be an extraordinary epic in virtual reality at some point. We have to start expanding what we think of as narrative, music, literature, art and particularly the visual image.

Granted, this whole passage is a bit baffling. It’s not completely clarified in a press conference the next day at the BFI London Film Festival. The relevant section starts at 16:26.

It’s also interesting that Benedict Cumberbatch (aka Dr. Strange) defends the need for auteurs.

Some comments on Sarris’s career and the vagaries of auteur theory are here. I discuss Black Panther and its debt to classical Hollywood storytelling here.

Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas (2007).