Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Threefer

DB here:

First, there’s this:

http://isthmus.com/screens/movies/film-scholars-david-bordwell-and-kristin-thompson/

Thanks to Laura Jones and the Isthmus staff for this profile. Among the stills they didn’t use is one of Kristin and me with Robert Altman. I interviewed him for a screening of The Player at the Walker Art Center in 1992. Why waste the scan? I thought, so I put it below.

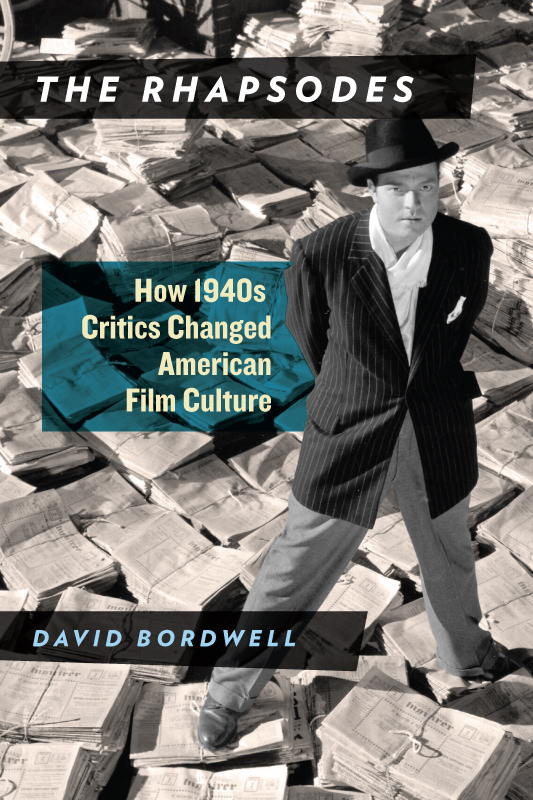

Second, there’s the pleasant fact that my book The Rhapsodes will be available on 4 April, Kristin’s birthday. It’s an essayistic study of four American film critics who, I think, prepared the way for the film-reviewing explosion of the 1960s.

I like to say that good film criticism offers not only opinions but information and ideas. Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, and Parker Tyler met that standard. The book tries to show that they had intriguing notions about American cinema and its aesthetic. They were superb writers as well. Although each man’s style was unique, they all wrote with a gleaming exuberance. The result, as the title suggests, is a controlled wildness, a quality captured I think in the book’s epigraph by Robert Lewis Stevenson:

In anything fit to be called by the name of reading, the process itself should be absorbing and voluptuous; we should gloat over a book, be rapt clean out of ourselves, and rise from the perusal, our mind filled with the busiest, kaleidoscopic dance of images, incapable of sleep or of continuous thought.

I’m very grateful to the University of Chicago Press, particularly my editor Rodney Powell, manuscript editor Kelly Finefrock-Creed, and Senior Promotions Manager Melinda Kennedy. Deep thanks as well to my initial readers Jim Naremore and Chuck Maland, and to the people who kindly endorsed the book: David Koepp, Manohla Dargis, and Philip Lopate.

More background on the book is here. I hope to offer some ideas about film criticism today in an upcoming entry.

Third, later this week Kristin and I are moving to Manhattan for three months. (Whoopee!) She’ll be working on her Amarna statuary project with her collaborator, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’ll be doing research, mostly on Hollywood in the 1940s, while watching movies, seeing friends, and blogging. I’ll give some talks as well. One, presented at Sacred Heart University and at Tufts, is drawn from the 1940s book. I’ll discuss The Rhapsodes at the 92nd Street YMCA and the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria (details on the last yet to be finalized). Maybe I’ll see you at one of these get-togethers?

Photo: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

In the mood for WKW

In the Mood for Love (2000).

DB here:

For quite a while, many of us have been looking forward to a book called Wong Kar-wai on Wong Kar-wai, a collection of interviews conducted by Tony Rayns. Alas, that is evidently never to be, for reasons that Tony hints at in his new BFI monograph on In the Mood for Love. Bits of those interviews make their way into the book anyhow, along with information and ideas reflecting Tony’s unique access to Hong Kong’s illustrious filmmaker. All lovers of WKW will want this energetic, accessible study.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

The thankless task of providing a detailed synopsis is carried off briskly, sustained by many explanations of culturally specific references. We learn of the daibaitong, the open-air restaurant where both Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan stop for a night’s noodles. We’re led to notice the inside joke about wuxia novels’ outlandish plots, as well as the changing of seasons as reflected in costumes. The synopsis is also sprinkled with critical-analytical points about parallels between the characters, relationships merely hinted at, and cross-references among the kindred films.

The talk around the Jet Tone office during the production of In the Mood for Love was of Chow Mo-wan setting out to seduce Mrs. Chan as a prelude to abandoning her: an act of wilful emotional cruelty intended as a revenge for being cuckolded himself. This inference is nowhere evident in the film as released, so Wong perhaps recycled the idea into Chow’s smiling rejection of a romance with “taxi-dancer” Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi) in 2046–although that rejection is itself a gentler replay of the playboy’s treatment of Carina Lau’s needy hooker Lulu, also known as Mimi, in Days of Being Wild.

There’s also quite a lot about the soundtrack, with close attention to the recurring melodies in the score and to the shifts between Cantonese and Shanghai in the dialogue.

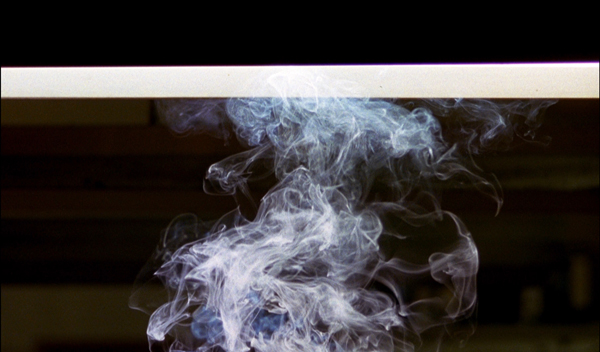

After the synopsis comes an analysis/interpretation. When the central couple reenacts their spouses’ affair, Tony suggests they’re testing the limits of their own inhibitions. He stresses the distinctiveness of Wong’s style, from its cinematic punctuation (the synopsis has emphasized the patterns of fades and straight cuts) to its handling of time–especially the strategically opaque narration, its “ostentatiously selective presentation of the action.” Of course the guilty spouses are never fully shown, but Tony also traces how time is skipped around via flashforwards and ellipses, sometimes barely noticeable ones. He points out how one cut relies on false continuity. Smoking alone in room 2046, Chow hears a knock on the door. Cut to a long shot of Mrs. Chan at the door–but she’s leaving.

We’ll never know what transpired during her visit. This exemplifies Wong’s “discontinuity in continuity”; flowing music, gentle tracking shots, and slight slow motion create a smooth surface that can conceal crucial information.

Tony has more to tell than the BFI format can squeeze in. I’d like more on the way quite disjunctive techniques fit into the film’s stylistic sheen. Wong deploys off-center framings, judicious use of depth in apparently real apartments, and variations in lighting among Hong Kong, Singapore, and Kuala Lampur. Tony’s hunch about continuity covering discontinuity might be extended to these aspects, and of course insider information on these matters would be welcome. I also wonder: Could there have been a hotel at the period boasting twenty stories? My Hong Kong friends say not. Tony argues that Wong’s films aren’t deeply political, but he was willing to violate plausibility to invoke the fateful year when HK becomes integrated into China.

Calm and ingratiating, the monograph is disarmingly personal as well. (How many books on a director start by noticing that the author has been dropped from a Christmas-card list?) It’s agreeably contrarian too. Tony teases academics, claiming at one point that the clock shots are “self-parodies” and “sucker bait” for critics who believe that Wong is the great cineaste of time. The book ends with a miscellany of observations about actors in bit parts, filmic offshoots of the project, and a little gossip. In all, reading In the Mood for Love gets you in the mood for In the Mood for Love.

Tony Rayns tells more in interviews on the Blu-ray disc of In the Mood for Love available from Criterion. That version of the film’s color seems far superior to other DVD versions I’ve seen, some of which have a dim, brownish cast. This is a hard film to replicate, though, as I found in taking 35mm frames: the tonal range is extraordinary, and your choice is often between exaggerating and lowering contrast.

Tony makes reference to the famous epilogue of Days of Being Wild that shows Tony Leung Chiu-wai, an apparently brand-new character cryptically introduced in this scene. The shot implies that there’ll be a sequel, and Wong has occasionally suggested the possibility. But there is a version of the film that includes a prologue showing the same character dressing to go out. Along with that scene is a sensuous passage in an underground gambling parlor. The sequence looks forward to imagery in In the Mood, including a sinuous shot of a woman ascending a staircase. If Wong chopped off the prologue to create the version of Days we have, he perversely left the dangling epilogue to tantalize us. For more about this “lost” version see my entry “Years of Being Obscure.”

I analyze Wong’s career, along with In the Mood for Love, in Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and I talk about The Grandmaster (which Tony considers a weak entry) here. I offer thoughts as well on Ashes of Time Redux. This project was the casus belli for Tony’s departure from Planet WKW. “The sometimes hair-raising tales of my experiences with Jet Tone will have to wait for another time.” What if we can’t wait?

In the Mood for Love.

Richard Corliss: Fulltime Critic

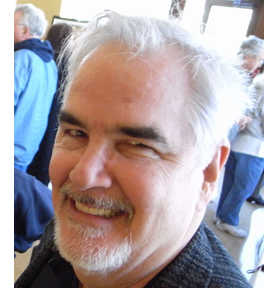

Mary and Richard Corliss, Ebertfest 2008.

DB here:

Parker Tyler called James Agee America’s biggest movie fan, implying that he was a lesser critic for loving movies. But Agee, who was often cast into despair by the films he met week by week, was actually in love with Cinema. From each release he sought glimpses of what he imagined movies could be, and so seldom were.

Tyler’s phrase might better apply to Richard Corliss, but in a deeply complimentary sense. Like his friend and occasional jousting partner Roger Ebert, Richard didn’t judge a film by whether it measured up to some ideal yardstick of the medium. He welcomed the movies—at Time, some 2500, between 1980 and now—as they came. He let his wide tastes, good sense, vast memory and knowledge, and breakneck gift for language decide what they counted for.

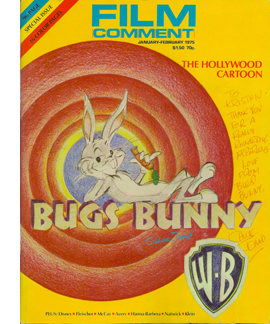

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

When he went over to Time in 1980, that square magazine suddenly looked younger. With Richard joining art critic Robert Hughes, it became a source of lively and penetrating arts journalism. Both turned Timespeak into something fresh. Hughes pulled it toward the eloquent bluntness of the Anglo essay tradition, while Richard transformed the forced puns and slant metaphors into something sprightly. Sarris may have been his mentor, but the rat-tat-tat pileup of clauses (semicolons optional), the self-correcting afterthoughts (as if a nuance had just occurred to the writer), and a concentration on actors all seem to me indebted to Kael. On Edward Scissorhands:

Depp, who wears the hyperalert, slightly wounded expression of someone who has just been slapped out of a deep sleep, brings a wondrous dignity and discipline to Edward. Wiest does a delightful turn on the plucky, loving mothers from old sitcoms. The whole movie, in fact, time-travels between today and the ’50s, when every suburban house could be a quiet riot of coordinated pastels. But the film exists out of time — out of the present cramped time, certainly — in the any-year of a child’s imagination. That child could be the little girl to whom the grandmotherly Ryder tells Edward’s story nearly a lifetime after it took place. Or it could be Burton, a wise child and a wily inventor, who has created one of the brightest, bittersweetest fables of this or any-year.

Richard gloried in the emotional and visceral energy of popular cinema. He defended both porn and zany comedy. On the Big Loud Action Movie he could channel Teenboy patois:

Toward the start of Fast Five — fifth and best in the series that began with The Fast and the Furious in 2001 — Brian (Paul Walker) is in a freight train and Dom (Vin Diesel) is steering a 1966 Corvette Grand Sport alongside it. At the last possible moment before the train goes through a bridge over a river, Brian jumps from the train and lands on the Corvette, which Dom then drives off a, like, million-foot cliff. As the car plummets down the ravine, our guys jump out and land safely in the water.

That “a, like, million-foot cliff” is alone worth the price of the issue. For such reasons, I think that Richard might be the most imitated critic of recent decades. Every reviewer at your town’s weekly hip throwaway wants to write like this.

They mostly can’t. In an essay on Fulltime Killer, Richard compared Johnnie To’s cinematic output to A. J. Liebling’s boast: “I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better.” It pretty much applied to Richard himself. He wrote about film, books, TV, travel, sports. Of the Bulk Producers we always ask, “When does s/he sleep?” With Richard we have to ask: “When did he pause?”

The Richard I followed most closely was on display in long formats. His book Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema (1974) made a stir that’s hard to appreciate now. Good student of Sarris that he was, Richard was an auteurist. He once tried to persuade me that Russ Meyer was at least as good as Minnelli. Yet his book called us to arms in a different cause.

The most difficult and vital part of a director’s job is to build and sustain the mood indicated in a screenwriter’s script—a function that has been virtually ignored while citics concerned with “visual style” trot off in search of the themes a director is more liable to have filched from his writers. …

When it comes to the mood men, the metteurs-en-scène, auteur critics start tap-dancing away from the subject. George Cukor is a genuine auteur; Michael Curtiz is a happy hack; Mitchell Leisen is actually despised by some critics for “ruining” films like Midnight and Arise My Love. Yet what Leisen and the writers of Hands Across the Table did to make that film the most amiable of thirties screwball comedies is a prime example of sympathetic collaboration. As with so many delightful comedies, it is the writers who create the characters and establish a mood in the first half of the picture, and the director who develops both in the second half. The story line of Hands Across the table isn’t flimsy; it’s downright diaphanous. . . .

Openly imitating Sarris’ catalogue The American Cinema, Richard’s book created an artistic genealogy of screenwriters, picking out the Author-Auteurs, the Stylists, and so on and then ranking them.. But where Sarris is synoptic, Corliss is dissective. Working at full stretch, he gives pages of close attention to particular films. His analyses of The Power and the Glory, The Lady Eve, and The Marrying Kind (“wavering between third-person omniscient and first-person myopic”) carry great intellectual heft, while Sarrisian potshots fly by. Reputations get deflated (Jules Furthman) or elevated (Sidney Buchman).

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

Finally, something I return to often: Richard’s 1990 essay attacking (no politer word will do) TV movie reviewers. “All Thumbs: Or, Is There a Future for Film Criticism?” castigates the tribe’s superficiality, their canned brevity, their reliance on clips, and above all their encouraging people to believe in quick judgments. Stars, numbers, grades, and thumbs are too easy. Richard bites Time’s corporate hand, complaining about snack-sized opinions in People and Entertainment Weekly. Against this trend he speaks for longer-form writing, pointing out that Sarris, Kael, and others had their impact because they could surpass the word limits mandated for most reviewers. It takes time to develop ideas that are subtle. Obvious, maybe, but tell that to the young blogger who insisted to me that a review ought to take no more than 100 words.

Roger Ebert was a target of Richard’s piece, and he replied in a courteous counterblast. Yet the men were fast friends. Richard did friendship superbly, with an effusive generosity. Just out of college, I submitted a couple of articles to the new Film Comment, and to my astonishment Richard accepted them. As I turned more academic, I stopped offering pieces to the magazine, but Richard–who could easily have become a film professor himself–didn’t hold it against me. When I came to New York a few years later for a job interview that proved disastrous, Richard and Mary were the only friendly faces I encountered, and lunch at their apartment, larded with gossip, was the high point of that visit.

In later years I encountered Mary, mostly during our visits to MoMA, more than Richard. But every now and then I’d get another burst of gratuitous kindness. He reviewed my Planet Hong Kong in a funny online piece about how Hong Kong film takes the stuffiness out of anybody.

Even a relatively staid critic such as structuralist guru David Bordwell seems to be typing in his shorts, with a beer on his desk.

The last time I saw Richard was with Mary at Ebertfest in 2008. We had a diner breakfast, and Richard did a dead-on imitation of John McCain. I still see that smile—part devilish wise-guy, part nerdy enthusiasm, all glowing good humor. He was wearing goofy trainers bearing the logos of the Majors. They looked damn fine. We had a good day.

In an interview with David Thomson Richard recalls his life and the early Film Comment era. See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s sensitive appreciation, especially on Corliss’s mastery of the “long reported piece”–another point of contact with Agee.

Problems, problems: Wyler’s workaround

The Little Foxes (1941).

DB here:

For me, shooting is a struggle where you only get to be happy for five minutes before you start thinking about the next problem to solve.

Ruben Ostlund, on Force Majeure

One of the most famous shots in American cinema occurs at a climactic moment in The Little Foxes (1941). Regina Giddens has just learned that her sickly husband Horace has let her brothers get away with a business deal that double-crosses her. They will reap all the rewards of bringing a factory to town, while she, who engineered the deal and expected Horace to fall in line, will get nothing. Horace is already not far from death, and their quarrel in the parlor precipitates a heart attack. He spills his bottle of medicine and needs some from his upstairs supply.

Regina refuses to go fetch it, and instead Horace must stagger up and out. While she sits, fiercely waiting, on the sofa, he tries to pull himself upstairs, but he collapses on the steps. Once he has fallen, and perhaps died, she stirs to action and rouses the household.

Lillian Hellman’s original play had been a Broadway success, and this was one of the most notable scenes. How did Wyler stage it? Very oddly, as the frame up top suggests. We can’t really see Horace’s struggle on the stair. Not only does the camera put Regina in the foreground, but Horace is out of focus in the rear, at least until she rises whirling and runs to the background, the damage done.

Why did Wyler stage it this way? It depends, as Bill Clinton might say, on what your definition of why is.

Deeper, closer

1941 was the breakout year of deep-focus filmmaking in Hollywood. Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, Kings Row, Ball of Fire, I Wake Up Screaming, How Green Was My Valley, and several other films set the pace for a new stylistic option. In this style, the action is staged in depth rather than perpendicular to the camera, as most scenes in Hollywood cinema were. And the camera lens creates depth of field, in which even fairly close foreground planes are just as sharp as the action in the rear. Such images weren’t unknown before; we can find them in silent cinema. But from 1941 on, depth staging accompanied by depth of focus would be increasingly common in Hollywood dramas, from thrillers and melodramas to film-noir exercises. Not all shots would be designed for maximal depth; continuity editing and closer views would still be used. But we do find such imagery becoming more common, particularly at moments of tension.

Cinematographer Gregg Toland is usually cited as a main source of this trend, and his work on Kane and Ball of Fire, as well as Ford’s Grapes of Wrath (1940) and The Long Voyage Home (1940), became models of the new look. Toland also worked with Wyler on several films, including The Little Foxes. But even without Toland, Wyler had in some films cultivated a deep-focus look (as had Ford). Coming when it did, The Little Foxes proved a powerful demonstration of the deep-focus style.

Three aspects stand out. First, there’s a certain economy of presentation. As Wyler and others pointed out, depth imagery permits directors to minimize editing. Instead of cutting from action to reaction, we see both at the same time.

Wyler suggested in publicity of the period that this gave the viewer more freedom of where to look, and André Bazin seized upon this rationale as part of his aesthetic of realism. Just as in the real world, in some films we must choose what to pay attention to.

But The Little Foxes went beyond the moderate deep focus of Stagecoach and other films to create very aggressive images. This is the film’s second novelty. Several shots place the foreground very close to the camera. As a result, we get looming faces or objects in the front plane, and we still see well-focused dramatic elements behind.

A third source of power is less noted. In The Little Foxes, Wyler found ways to make deep shots comment upon the plot. For instance, the action offers Regina’s daughter Alexandra, usually called Zan, a choice of being more like her mother (tough and vicious) or her father (tolerant and gentle). At other points Zan is paralleled to her ineffectual, alcoholic aunt Birdie. At one point, Birdie has predicted that Zan may wind up like her.

In a theatre production, there would be many staging strategies that would create these parallels, but Wyler uses a particularly striking one. One evening, while Regina and her brothers plot their scheme, Birdie has been relegated to a chair far from the discussion.

The composition diagrams Birdie’s situation in the scene and her place in the family. Then Wyler cuts in to her.

This might be seen as a bit of heavy-handed emphasis, but actually he’s doing two things. He’s making manifest her reaction, a numb resignation to being excluded. He’s also setting up, thanks to another depth composition, the chair in the hallway by the staircase. At the climax, it’s Zan, as beaten down as Birdie, who slumps in that chair.

Thanks to depth staging and deep-focus cinematography, the second image emphasizes Birdie’s solitude and prophesies Zan’s.

Which only makes my first question more pressing. Some shots of the quarrel leading up to Horace’s collapse on the stair exhibit flagrant deep focus.

We know from other shots in the film, like the Birdie/Zan comparison, that Wyler could have simply shown us Regina on the sofa in the foreground, in long shot or medium shot, while keeping Horace in focus in the background. In fact, Wyler tells us that Toland said, “I can have him sharp, or both of them sharp.” Why opt for shallow focus that makes Horace’s staircase seizure blurry and hard to see?

Fun with functions

Asking why? about something in an artwork actually veils two different questions.

The first is: How did it get there? The answer is a causal story about how the element came to be included.

The second sense of why is: What’s it doing there? That’s not a question of causes but of functions. How does the element contribute to the other parts and the artwork as a whole?

Take the second question first. You can imagine many functional reasons for Wyler’s choice. Exactly because the rest of the film keeps image planes sharp, this moment gains a unique emphasis. Horace’s collapse is marked as a major turning point in the plot. In an ordinary film, we wouldn’t notice an out-of-focus background. Here, by reverting to the more traditional choice, Wyler makes shallow focus stylistically prominent. For once in a film, a dramatic high point isn’t given to us with maximum visibility.

Another function is character revelation. In the film as a whole, we haven’t been consistently restricted to any one character. Here, Wyler could have concentrated on either Horace or Regina, or he could have given them equal treatment. An obvious choice would have been intercutting shots of Horace crawling up the steps with shots of Regina, impassively turned from him. Probably most directors would have done it that way.

Alternatively, we might have been attached to Horace, letting us see Regina in the distance. That would have diminished her reaction and played up Horace’s suffering.

Wyler’s choice puts the emphasis not on the action—thanks to the distant framing, Horace’s collapse can almost be taken for granted—but Regina’s reactions, or rather non-reactions, moment by moment. We’re made to see her turning slightly to listen to his struggles, while her staring eyes suggest that she’s visualizing the action with a horrified fascination. It’s as if her denying him the medicine was an experiment in seeing how far she could go. Now she knows. Her straining face is virtually willing her husband to die.

Keeping both this monstrous woman and her victim in focus would have divided our attention, then, and Wyler wants it squarely on Regina. He seems to have said as much in interviews.

We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.

I wanted audiences to feel they were seeing something they were not supposed to see. Seeing the husband in the background made you squint, but what you were seeing was her face.

The second remark suggests another functional result of Wyler’s choice. By making the collapse almost indiscernible, we become very aware of what we can’t see. Thanks to selective focus, Bazin remarked, “The viewer feels an extra anxiety and almost wants to push the immobile Bette Davis aside to get a better look.” The dramatic tension of the scene finds its counterpart in our frustration to see what any other film would show us.

Finally, we should note that the staircase is an essential element in the film’s drama. Horace’s collapse is only one major incident taking place around and on it. Significantly, when Zan finally breaks free of Regina and the rest of the family, the matriarch learns of it standing on the stairs. Having all but murdered her husband there, now she sees her daughter abandon her.

Shoot my good side

The Bishop’s Wife (1948).

There are other functions we, as good critics, might seek out. For all of them, there is probably a loose causal story we’re relying on: Wyler and his colleagues made some choices that bore fruit. Some of those choices may have aimed at fulfilling the functions we notice. Other functions we notice may come along as bonuses—unintended but still benefiting the scene. Unintended consequences, good or bad, come up in art as elsewhere.

There remains the other implication of why-did-they-do-it questions: the one that seeks out quite specific causes that govern the scene. How do we tackle that?

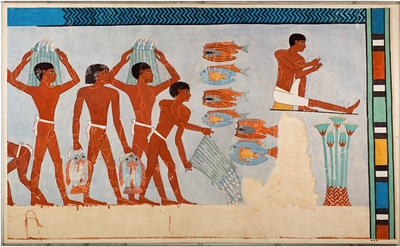

In my book On the History of Film Style, from which some of these Little Foxes observations are drawn, I argued that we can make stretches of stylistic history intelligible by thinking in terms of problems and solutions. Art historians have done this for a long while. Assuming that you want to suggest that something in the picture is farther away than something else, how do you do it? One way is through overlap, as in Egyptian art. Here the fishermen overlap the background, their legs overlap each other’s, and the strings of fish that one is carrying overlap some legs.

Later image-makers suggest variable distances through size variations, placement in the format (a little bit of that here, with the river above/behind the men), tonal contrast, atmospheric perspective, linear perspective, and other techniques. These can be considered solutions, available to artists of different times and places, to the problem of suggesting three dimensions on a flat surface.

A problem/solution way of thinking can clarify some developments in the history of filmmaking too. If you have to represent two actions taking place simultaneously, how can you do it? Crosscutting, as Griffith and others showed in the 1910s, solves that problem. It offers spillover benefits too, such as controlling pace. Similarly, there’s the problem of representing spoken dialogue. Silent films solved this in various ways—through a commenter in the theatre (the benshi in Japan), through actors voicing the roles behind the screen, and most commonly through intertitles. Later, synchronized sound solved the problem in a more thoroughgoing way.

These are very general answers to the how-did-it-get-there question. Occasionally we get more concrete information about problems and solution. For example, some Hollywood stars believed that one side of their faces was more appealing than the other. The stars with the most power could insist on being filmed on their good side, which led directors to make particular staging choices. (Claudette Colbert insisted her left side was her good side, so she’s usually positioned on screen right, with her face turned toward screen left.) David Butler knew that Edward G. Robinson likewise favored his left side, so Butler needed to stage Robinson’s one appearance in It’s a Great Feeling (1949) with him entering a scene from right to left and playing in that position.

One vain star is problem enough, but what happens when you have two who prefer being shot from the same side? According to Henry Koster, the demands of Cary Grant and Loretta Young led to the staging of the scene shown at the top of this section. (For my reservations, see the codicil to this entry.)

The Little Foxes production provides evidence of another very specific problem. In staging the staircase collapse, Wyler faced an unusual difficulty. The actor playing Horace, Herbert Marshall, had a prosthetic leg.

Marshall lost his right leg, from the hip down, in World War I. Through practice he managed to stroll quite smoothly nonetheless, and he became a significant star and featured player in theatre and films. He doesn’t need to walk much in The Little Foxes because his character is rolled around in a wheelchair. But the parlor-and-staircase scene was very demanding. As Wyler explains:

Now there was another problem involved with that, and that was the fact that Herbert Marshall has a wooden leg and couldn’t make the stairs, you see. This is a trade secret. I had him stagger in the background, get behind her and just for a moment when he gets to the stairs he had to go to a landing over there, and just for a moment went out of the picture. And a double came in and went up the stairs, staggered way behind out of focus.

Here you can see Marshall leave the foreground.

An axial cut in to Regina shows him stumbling behind her and going out of shot in the distance. This much Marshall could manage.

At that point the double stumbles into the frame and starts to crawl up the staircase.

Regina leaps up and runs to the rear, and the camera racks focus to the stair, but by now the double’s face is out of frame.

So the director solved the problem of the actor’s disability by a combination of deep staging, the use of a double, and shallow focus. This “trade secret” yielded a range of effects that, I think most viewers would agree, were vivid and exciting.

But there’s always more than one way to do anything. Given the constraint of Marshall’s artificial leg, or a player’s insistence on being shot from one side, or the leading lady’s overnight pimple, a director can work around it in several ways. One of the few critics to notice the implications of Wyler’s choice was Raymond Durgnat, a critic very sensitive to style.

Given a “pimple” or a “wooden leg,” different stylists will find different solutions. One changes the camera-angle; another introduces a last-minute panning shot; another will retain the original set-up, but throw heavy shadows to conceal the offending detail; another will interpose a pot of flowers or a table-cloth to conceal the trouble spot from the camera. The director has ample opportunity to maintain his style in the face of “accident.” And it’s no exaggeration to say that such stylists as Dreyer and Bresson would imperturbably maintain their characteristic style even if the entire cast suddenly turned up with pimples and wooden legs.

I’d add only that the director’s choices are further constrained. Beyond the immediate problem, the broader pressure of norms will kick in. The norms of classical studio lighting, cutting, and performance limit the ways Toland and Wyler can cover up Marshall’s infirmity. The norms of quality A-picture American filmmaking of the period militate against, say, editing the scene so that a dummy is substituted for Marshall on the stair. (We might get that in a serial, though.)

There are also the intrinsic norms set up in The Little Foxes as a formal whole. These favor handling the scene in depth in some way. Wyler reports the decision: “We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.” Wyler’s earlier choices in the film created a kind of path-dependence for this critical moment. Deep-space staging could stay in tune with the rest of the film; but because of his actor’s infirmity, he could give up deep-focus cinematography. This solution created a vivid variant on the film’s intrinsic norm.

You can also argue that by deciding to call our attention to a distant plane in soft focus, Wyler fell back on something he had tried before. In the extraordinary late silent The Shakedown (1929), he showed a pie being stolen in a diner. First, there’s a close-up, then a shot of the main couple looking to the background. In the center, out of focus underneath the coffee urn, the pie is slipping away.

The action isn’t very discernible in my image, which is from a 35mm print; but the scene is shot quite soft anyway. I think audiences notice the gesture, slight as it is, because it’s centered and nothing else is moving in the frame. More visible is the background action in a shot Wyler and Toland used in Dead End (1937). Two gangsters are sitting in a bar debating kidnapping a child. In the out-of-focus background,we can discern a woman wheeling a baby carriage along the sidewalk. She isn’t the target, just a sort of reminder of children’s vulnerability. As in The Little Foxes, a centered background action attracts our attention and makes us strain to identify it.

Faced with a similar problem in The Little Foxes, Wyler had the chance to dramatize a soft-focus background to a much greater extent than in these films.

One more causal factor might have shaped Wyler’s decision. Lillian Hellman’s original play takes place wholly in the Giddens’ parlor and the hallway behind. The play text indicates that the staircase is in the rear of the set, with a landing offstage. The furniture sits downstage, closer to the audience. The foreground/background interaction in Wyler’s staging is already there, in a rougher form, in the play’s set arrangement.

And how does the play handle the moment of Horace’s collapse? When Horace’s medicine bottle breaks, Regina doesn’t move. Calling for Addie the maid, Horace leaves and staggers to the rear playing area.

He makes a sudden, furious spring from the chair to the stairs, taking the first few steps as if he were a desperate runner. Then he slips, gasps, grasps the rail, makes a great effort to reach the landing. When he reaches the landing, he is on his knees. His knees give way, he falls on the landing, out of view. Regina has not turned during his climb up the stairs. Now she waits a second. Then she goes below the landing, speaks up.

REGINA: Horace, Horace.

The foreground/background dynamic, as well as the frozen indifference in Regina’s performance, are written into the scene’s stage directions. Hellman’s instructions yield a further hint: Horace “falls on the landing, out of view.” Within the norms of the deep-focus aesthetic, Wyler and Toland found a cinematic equivalent for this barely-offstage action–one appropriate for their film’s particular style. They make Horace present, but he’s “out of view.”

Somebody may say: “See? You don’t need all this fancy analysis. At bottom, Wyler was forced to shoot the scene this way because of Marshall’s bum leg.” This retort assumes that causal factors always trump functional ones. Instead, I think that by considering causal factors, insofar as we can know them, alongside functional ones, we can better understand filmic creativity in history.

Durgnat’s point shows us how. Even when contingent circumstances “force” a filmmaker to change course, there are always several ways to do that. Picking any option brings in a cascade of other constraints and opportunities. Once Wyler has decided to double Marshall and sustain the take on Davis, soft focus is more or less necessary so we don’t spot the stand-in. But the soft-focus provides a nifty opportunity to create the sorts of functions and effects we’ve already noticed.

Like everybody else, filmmakers choose within constraints—some apparent, some less visible, many just taken for granted. Those constraints limit what can be done, but they also enable other things to happen, perhaps things that the filmmaker couldn’t have planned in advance. Once other filmmakers realize the results, they can plan in advance. A moviemaker today can try out Wyler’s solution, free of the pressures that drove him to it. A significant part of filmmaking’s traditions may consist of workarounds.

The Ostlund epigraph, apparently not available online, is taken from Hollywood Reporter’s December awards issue, p. 13. My Egyptian picture comes from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s called Fish Preparation and Net Making, from the Tomb of Amenhotep (1479-1458 BCE), as rendered by Nina de Garis Davies. I draw the stage directions in The Little Foxes from Lillian Hellman, The Collected Plays (Little, Brown, 1971), 195.

My quotations about It’s a Great Feeling and The Bishop’s Wife come, respectively from two books by Irene Kahn Atkins, David Butler (Scarecrow, 1993), 227; and Henry Koster (Scarecrow, 1987), 87. Koster’s memory fails him in his account of the Bishop’s Wife window scene. It seems likely that Loretta Young favored her left side, which is her dominant orientation throughout the film. But there’s no evidence in the film that Cary Grant favored that side of his face too. The scene at the window is too brief to count as an instance of much of anything.

When I wrote On the History of Film Style in the mid-1990s, I had the nagging memory that Marshall’s artificial leg played a role in Wyler’s staging, but I put it down as legend. (It’s a pity I didn’t pursue it, because the information would have fitted snugly into my sixth chapter.) Only when I discovered a 1972 interview with Wyler, with the “trade secret” mentioned above, did I realize there was something to the story. That interview was once online, but seems to have vanished. It’s available at Columbia University. Durgnat’s discussion is in Films and Feelings (MIT Press, 1967), 41. My other quotations from Wyler come from Axel Madsen, William Wyler (Crowell, 1973), 209.

Otis Ferguson reported on the filming of a different scene in The Little Foxes; I discuss that here. More generally, on the Bazin-Wyler connection, see this entry. Other Wyler-related entries can be canvassed here. For more on Hollywood’s development of deep staging and deep focus, see not only On the History of Film Style but also Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. As for Bette Davis’s eyelids, much in evidence here, there’s this entry.