Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Say hello to GOODBYE TO LANGUAGE

DB here:

Godard is making trouble again. Adieu au langage–known now as Goodbye to Language– is doing better in the US than any of his films have done in the last thirty-some years. It has a per-screen average of $13,500, which is about twice that attained by Ouija in its opening last weekend.

But that average represents only two screens, and it’s going to be hard to expand because Goodbye to Language is in 3D. Many art houses would love to play it, but they lacked the money to upgrade to 3D during the big digital conversion of recent years. Even high-powered venues in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago don’t have 3D installed. Here in Madison we’re showing it as a benefit for our Cinematheque. But the film’s prospects may be brightening.

Re-seeing it (twice) at the Vancouver International Film Festival back in September, I was struck by a few more ideas about it. Kristin and I avoid listicles, but after writing an expansive entry on the film, all I’ve got at this point is some scattered observations. Two ragtag comments are semi-spoilers, and I’ll warn you beforehand.

The Power of post As far as I can tell, Godard hasn’t used the converging-lens method to create 3D during shooting. Instead of “toeing-in” his cameras, he set them so that the lenses are strictly parallel. He and his DP Fabrice Aragno apparently relied on software to generate the startling 3D we see onscreen.

This reminds me that postproduction has long been a central aspect of Godard’s creative process. Of course he creates marvelous shots while filming, but ever since Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960), when he yanked out frames from the middle of his shots, he has always made post-shooting work more than simply trimming and polishing. His interruptive aesthetic is made possible by editing that wedges in intertitles (sometimes the same one several times). He breaks off beautiful shots and drops in bursts of music that snap off just before they cadence.

In both sound and image, the post-production process for Godard is a kind of transformation, an openly admitted re-writing of what came from the camera. He slaps graffiti on his own film. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I argued that our sense of a Godard film being “told” or narrated by the director proceeds partly from his ability to create the impression of a sort of Cineaste-Emperor, a sovereign master who is governing what we see and hear at any given moment. The collage principle suggests someone behind the scenes pasting these fragments together. Not only his commentary (once whispered, now croaked) but every shot-change and bit of music and noise, every intertitle and look to the camera all bear witness to Godard as God. Before he cut a strip of film; now he twiddles a knob or guides a slider. In all cases, we still feel his playful, exasperating hand.

Godard’s famous collage aesthetic relies on aggressive changes to image and sound in postproduction that all but deface the surfaces of his movie. No surprise, then, that Godard 3D lays out those surfaces boldly, with distant planes sharply edged and volumes that stretch out before us.

Yet with his superimposed titles, sometimes hovering among the audience, he can flatten volume and stack up planes like playing cards. It’s partly a joke that the 2D title below is closer to us than the 3D one behind it, but even that sticks out further than the unidentifiable light array that is farthest away.

The Rule and the exception. Just as Hollywood cinema erected rules for plotting, shooting, and editing, it has cultivated rules for “proper” 3D filming. An informative piece by Bryant Frazer points out some ways that Godard breaks those rules. Still, just calling him a maverick makes him sound merely willful. Part of his aim is to explore what happens if you ignore the rules.

This is Godard’s experimental side: He considers what “good craftsmanship” traditionally excludes, just as the Cubists decided that perspective, and smooth finish, and other features of academic painting blocked off some expressive possibilities. To get a positive sense of what he’s doing, we need to understand what the conventional rules are intended to achieve. Consider just two purposes.

1. 3D, the rules assume, ought to serve the same function as framing, lighting, sound, and other techniques do: to guide us to salient story points. A shot should be easy to read. When 3D isn’t just serving to awe us with special effects, it has the workaday purpose of advancing our understanding of the story. So, for instance, 3D should use selective focus to make sure that only one figure stands out, while everything else blurs gracefully.

But 3D allows Godard to present the space of a shot as discomfitingly as he presents his scenes (elliptical, they are) and his narrative (zigzag and laconic, it is). As in traditional deep-focus cinematography, we’re invited to notice more than the main subject of a shot, but here those piled-up planes have an extra presence, and our eye is invited to explore them.

2. According to the rules, 3D ought to be relatively realistic. Traditional cinema presents itself as a window onto the story world, and 3D practitioners have spoken of the frame as the “stereo window.” People and objects should recede gently away from that surface, into the depth behind the screen. But Adieu au langage gives us a beautiful slatted chair, neither fully in our lap nor fully integrated into the fictional space. It juts out and dominates the composition, partly blocking the main action–a husband bent on violence hustling out of his car.

That chair, or one of its mates, reappears, usually with greater heft than the human characters shoved nearly out of sight behind it.

In sum, visual realism of the Hollywood sort is only one mode of moviemaking. Godard lets us know from the very start that he’s after something else. The film’s first title announces: “Those lacking imagination take refuge in reality.” Goodbye to Language is an adventure of the imagination.

Innovation, intractable. Godard has been around so long that some of his innovations—jump-cuts, interruptive intertitles—have become common in mainstream movies. But there remains an intractable core that is just too difficult to assimilate, and he has always been a few jumps ahead of people who want to de-fang his experiments.

Supposedly Picasso told Gertrude Stein: “You do something new and then someone comes along and makes it pretty.”

A fresh eye. French thinkers have long pondered the possibility that language separates us from the world. It drops a kind of scrim that keeps us from seeing things in their innocent purity. Given the film’s title, I suggested in an NPR interview that Godard’s use of 3D, along with the insistence on the dog Roxy, is aiming to make us perceive the world stripped of our conceptual constructs (language, plot, normal viewpoints, and so on). Personally, the idea that language alienates us from some primordial connection to things seems to me implausible, but I think it’s a central theme of the film. This very talky movie exploits a paradox: we must use language to say goodbye to it.

Learning curve. Critics put off by Godard, I think, have too limited a notion of what criticism is. They seem to think that their notion of cinema, fixed for all time, is a standard to which every movie has to measure up. They are notably resistant to a simple idea: We can learn something from films. Not only can we learn things about life but we also learn things about cinema. We learn things that we never realized that film can do.

But then, how many critics actually want to learn something about cinema, which can only happen the way we learn anything: by wrestling with something that strikes us as difficult?

Two soft spoilers ahead!

On re-viewing, I was struck by other ways in which the two long parallel stories echo one another: a big bowl of flowers, later one of fruit; the repetition of “There is no why!”; and an odd colorless or nearly colorless image of each principal woman.

As with so much else in the film, Godard posits his own slippery version of a parallel-universe plot, and this overall formal option is underscored by these stylistic choices. In the first prologue, the woman on the left above is also given to us in a color shot, as if the disparity color/black-and-white points ahead to the nearly black-and-white color shot to come.

The (apparent) deaths of the principal men are rendered very obliquely, but apparently out of story order. This juggling with chronology, a staple of modern cinema, is fairly rare in Godard, at least as I recall.

Clearly, 3D is becoming something we cinephiles need to face up to. I balked at the beginning, but I’ve come around. Important filmmakers like Godard, Herzog, and Wenders are working with it. Just as important, we’ve never until now been able to study 3D movies closely. I remember watching Bwana Devil and others on a flatbed in the Library of Congress in the early 1980s, but if I stopped on any frame, I couldn’t tell what the 3D effect was like. Of course any 2D print of a classic 3D title represents only one camera’s view.

The victory of digital projection yielded a benefit I hadn’t foreseen when I wrote Pandora’s Digital Box. After Dial M for Murder came out in BD in 2012, I realized I needed to upgrade. We bought a bargain TV and BD player just when 3D TV had been declared dead. Now our 3D collection has expanded to include Hong Kong titles as well as favorites like Wreck-It Ralph, Gravity, and A Very Harold and Kumar 3D Christmas. Costs of 3D discs are sometimes low, and while you need a bigger monitor than we have to approach the force of a big-screen viewing, we can at least study a director’s use of the format frame by frame.

So for viewers who can’t get to Goodbye to Language in theatres but who have a 3D TV may take heart: Kino Lorber will be releasing a 3D Blu-ray disc.

Vadim Rizov has a brief but intriguing interview with Aragno in Filmmaker Magazine. “”Hollywood says you shouldn’t have more than six centimeters between cameras, so I began at twelve to see what happened.” Obviously a simpatico collaborator.

I discuss aspects of Hitchcock’s use of 3D in Dial M for Murder here.

P.S. 4 November 2014: The distribution of Goodbye to Language has become a cause célebre. Justin Chang surveys the situation in Variety.

P.P.S. 13 November 2014: Geoffrey O’Brien’s enthusiastic appreciation of the film not only illuminates it but conveys the excitement of seeing it.

P.P.P.S. 14 November 2014: Two more thoughts, after seeing the film again last night at our Cinematheque screening. First, the “unidentifiable light array” I mention above is actually on the cover of the French edition of A. E. Van Vogt’s The World of Null-A shown later in the film. Second, this time I noticed that the war imagery in the film’s first part subsides in the second, to be replaced, it seems, by Roxy’s wanderings–a more lyrical, peaceful counterweight to the horrors invoked earlier. The pivot would seem to be the first helicopter crash at the end of the first part. There among the flaming ruins we can see the burned head of a dead dog. Roxy’s proxy? Anyhow, the original survives, exuberantly, in the film’s second long part.

Goodbye to Language.

Zip, zero, Zeitgeist

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014).

DB here:

The silly season always seems to catch me off guard. This time I got the word in a New York Times feature, “The Moviegoers.”

Here two writers, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, conduct an email conversation about recent films. You may have thought that the Times already has a large stable of movie reviewers, headlined by Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott. But mainstream movies are very accessible (as opposed to, say, serial music or Baroque architecture), so nearly everybody has something to say. And because nobody knows what counts as expertise in movie reviewing, why not bring on two of the commentariat? Once you become a public intellectual, what you say about anything is interesting.

Granted, both participants in the dialogue, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, have been movie reviewers. Mr. Bruni wrote for the Detroit Free Press, and Mr. Douthat currently covers film for the National Review. Through some process yet unexplained, these movie reviewers became second-string social and political pundits for the Times. That would seem a step up, so why put them back in the reviewing game?

The rationale is supplied in the series introduction, which talks of the plan to discuss “movies, pop culture, television, and other real-world distractions.” The Times style guardian might want to pause on the last phrase: Are these phenomena distractions in the real world (as in “real-world opportunities”)? Or are they distractions from the real world? I think the writer means the latter, which translates into this: Politics is the important stuff, mass art is a lightweight diversion. And we all need diversion, especially a newspaper aiming to attract readers under fifty.

So we have two Op-Ed columnists taking a break from serious matters in order to shoot the breeze about summer releases. In “Two Thumbs Up…Yer Arse.” Charlie Pierce, our fouler-mouthed Mencken, has exposed some curious assumptions about poverty displayed in the Moviegoers’ first round of chitchat. What interests me here is another aspect of the column, which showcases one standard move that many reviewers make.

The problem for serious people like Mr. Douthat and Mr. Bruni is this. If movies are “real-world distractions,” why spend any time talking about them? More specifically, why should political pundits talk about them? The obvious answer: Somehow these products of popular culture open a window into what’s really going on. Mr. Douthat:

In this sense I do think moviemakers are tapping into the American psyche, but I also think they’re replicating a flaw of the American political debate. I’m not sure we’ll get very far by painting the rich as morally hopeless people who must be subverted, vanquished, overtaken.

And when Mr. Bruni asks, “Tell me about the trend that made you happy, and (speaking of political allegories) whether you like ‘Apes’ as much as everyone else,” Mr. Douthat replies:

There was something poignant about watching “Apes” against the backdrop of the mess in the Middle East and of the war in Israel and Gaza, because it’s a disturbingly good allegory of reciprocal mistrust, asking the right questions about how peace ever reigns when combatants can’t bring themselves to forgive error, to take the first step, to turn from the past and focus on the future, to start afresh. It’s a disturbingly good allegory about corrupt leaders, too: how they whip up fervor in the service of their own ambition; how we rise and fall based on the clarity and wisdom with which we choose them.

You may want to reply that if this is what the Times wants, you will undertake to supply them with 3000 words of it every day at reasonable rates. But put aside the banalities about politics. I’m interested in the suggestion that movies can bear traces of the national psyche, or reflect national debates we’re having right now, or provide inadvertent “allegories” of contemporary history.

These ideas enjoy an astonishing popularity. They are staples of movie journalism. The trouble is that they don’t hold up.

Reflections on reflectionism

That mass entertainment somehow reflects its society is, I believe, the One Big Idea that every intellectual has about popular culture. The notion shapes the Sunday Times think piece about how the movies of the last few months capture the current Zeitgeist (or one a while back). It informs the belief that we can define periods in American popular art by presidential eras–Leave It to Beaver as cozy Eisenhower suburban fantasy, Forrest Gump as an expression of Clinton-era post-Cold-War isolationism. Reflectionism may be the last refuge of journalists writing to deadline, but it’s also found in the industry’s talk about itself. “Oscar Best Pic Contenders Reflect America’s Anxieties,” Variety announced last winter.

The threat of circularity. Behind this Big Idea is an assumption that cinema, being a “popular art,” tends to embody some state of mind common to the millions of people living in a society. The very idea of a massive mind-meld like this seems implausible. America’s anxieties and our national psyche? The anxieties of the 1% are not yours and mine, and I doubt that even you and I share a psyche.

The argument easily becomes circular. All popular films reflect society’s attitudes. How do we know what the attitudes are? Just look at the films! We need independent and pretty broadly based evidence to show that the attitudes exist, are very widespread, and have been incorporated in films. And it won’t do to simply point to the same attitudes surfacing in TV, pop songs, mass-market fiction as well, because that just postpones the problem of correlating the attitudes with groups of living and breathing people.

Critics seem to assume that if a film is successful at the box office, it must reflect the audience’s inner life. Yet the sheer fact of a movie’s popularity doesn’t prove that these attitudes are out there. Just because Spider-Man (2002) was a huge success doesn’t mean that it offers us access to America’s national mood or hidden anxieties. People spend time with a piece of mass art for many reasons: to kill an idle hour, to meet with friends, to find out what all the fuss is about. After the encounter, consumers often dislike the art work to some degree, or they remain indifferent to it. Since people must buy the movie ticket before they experience the movie, there can’t be a simple correlation between mass sales and mass mood. You and lots of others may be suckered into going to a film you dislike, but just by going you’ve already been counted as among those who support it. Doubtless many people enjoyed Spider-Man. But it’s very difficult to say how many.

And did all of the patrons who enjoyed it do so for the same reasons? That remains to be shown, and it’s hard. We know that a movie may appeal to several audiences at once, packaging a range of appeals. In fact, it’s a strategy of the film industry to produce movies that contain fuzzy messages, contrary attitudes, and something for nearly everybody. Must we find reflections of cultural needs in every aspect of a movie that might appeal to somebody?

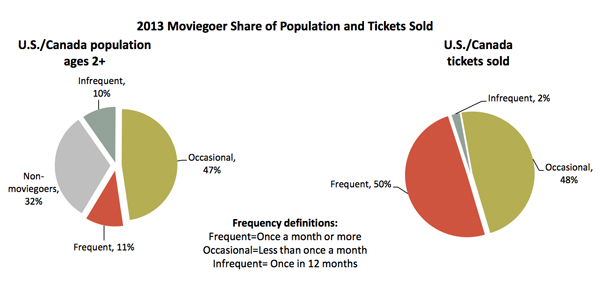

Movies are narrowcasting. The film audience is a skewed sampling of the population. According to industry statistics, about one-third of Americans over the age of two never go to the movies, and another ten percent go once a year.

Another 40% go “occasionally”–less than once a month. It turns out that the heavy moviegoers, those going once a month or more, are currently just 11% of the population. Take Dawn of Planet of the Apes. Assuming an average ticket price of $8 and no repeat viewings, at most about 25.5 million Americans and Canadians have seen the movie. That’s about 7% of the countries’ total population. We would need to tell a pretty full story about how the mental life of 350 or so million people gets into movies seen by a thin, self-selected slice of the population.

Moviegoers are atypical of the population in other respects. Since the beginning, Hollywood cinema has catered to the middle class. Moviegoers have been younger, better educated, and better-off economically than non-moviegoers.

The real mass medium of our time is network television (as radio was before). On one night, a single episode of The Big Bang Theory can attract 19 million viewers. A film that had that viewership across an opening weekend would take in over $150 million. That is $50 million more than the latest Transformers movie garnered at its debut. If Messrs. Douthat and Bruni want to take the national temperature, they should watch TV–ideally, the ads on the Super Bowl (shown to 112 million viewers).

Actually, you can argue that television really is a more reliable barometer of mass tastes, not just because of its prevalence but because TV viewing depends on recidivism. People may not know they’ll like a movie before they attend, but they tune in to shows that have proven to satisfy them. Still and all, mass taste is not the national psyche.

The long road from the White House. A primary prop for reflectionists is politics. Talk about an American film of the 1950s and sooner or later someone will invoke the reign of blandness that was (purportedly) the Eisenhower administration. But why do we assume that the population’s mind set switches its course whenever a new President is elected? Many voters stubbornly adhere to the same values election after election; others vote in order to throw out a rascal and aren’t at all satisfied with the newcomer.

There couldn’t be a direct tie between elections and moviegoers’ attitudes. About thirty percent of today’s audience consists of people too young to vote. The most reliable voter turnout is among the over-forty-five set, which until recently constituted only about twenty percent of moviegoers. Of course, maybe movies reflect the attitudes of non-voters, or people who are indifferent to politics. But then why identify periods of political history with periods of movie history?

Reflectionists have always been reluctant to offer a concrete causal account of how widely-held attitudes or anxieties within an audience could find their way into art works. What precise story could we tell to explain how changing the occupant of the White House can affect popular culture? How exactly does a party platform or a candidate’s charisma or the new administration’s policies seep into Hollywood movies for the multitudes?

Movies’ crystal ball. If there ever were a dominant mood at large in the land, it would be very difficult for that mood to find its way into a current movie. There’s often a lag of several years before a script gets to the screen. Many of the films released in 1997, though read as responding to current crises, were bought as projects in 1993 and 1994. Dawn of Planet of the Apes was begun in 2011, written through 2011-2012, and began shooting in April of 2013–all before the current standoff between Israel and Hamas.

Maybe the moviemakers are somehow in touch with political forces before they crystallize? One critic has proposed that films can have this prophetic power. Puzzled that no Obama-era movies had emerged by 2012, J. Hoberman suggests that the most “Obama-ite” ones came out before Obama was elected:

The longing for Obama (or an Obama) can be found in two prescient 2008 movies—WALL-E (the world saved by an endearing little dingbot, community organizer for an extinct community) and Milk (portrait of another creative community organizer—not to mention a precedent-shattering politician who, it’s very often reiterated, presented himself as a Messenger of Hope).

This is nearly a miracle. Somehow these filmmakers sensed that Americans (well, 53% of the people voting) were yearning to be led by a community organizer. But how specifically could the filmmakers have arrived at that prescience? In fact, they would have had to be long-range prophets. Milk began as a 1992 project, and the final version of the script was prepared in 2007. The Pixar adepts started talking about WALL-E in 1994 and began drafting scripts in 2002. Why don’t we ask filmmakers to predict our next president right now?

Pick and choose. Of all the films of the summer, Bruni and Douthat settle on a few. Of all the hundreds of 2008 films, two presage Obama. This selectivity is typical of the reflectionist approach, which typically ignores the range of incompatible material on offer.

If 1940s film noir reflects some angst in the American psyche, how to explain the audience’s embrace of sunny MGM musicals and lightweight comedies in the same years? The year 1956 saw the release of The Ten Commandments, Around the World in 80 Days, Giant, The King and I, Guys and Dolls, Picnic, War and Peace, Moby Dick, The Searchers, and The Lieutenant Wore Skirts. Pick one, find some thematic concerns there that resonate with social life of the time, and you have a case for any state you wish to ascribe to the collective psyche. But take any other movie, or indeed the industry’s entire output, and you have a problem. One alternative is for us to find that the films share common themes, but these are likely to be of an insipid generality. Or we could float the rather uncompelling claim that several hundred films reflect hundreds of different, and contradictory, facets of the audience’s inner life.

Consider the source. Of course filmmakers sometimes deliberately include political comment. But then the film is “reflecting” the purposes of its particular makers, not the mass public. The filmmaker may claim to be tapping the Zeitgeist, but it’s really the Zeitgeist as she or he understands it. It’s not the public expressing itself spontaneously and unselfconsiously through the movie.

Movies use a lot of collaborators, and they may have varying agendas. The most powerful players are inevitably going to shape the initial project in specific, often personal ways. The preoccupations of the screenwriter, the producer, the director, and the stars necessarily transform the given idea. And these workers, living hermetic lives in Beverly Hills and jetting off to Majorca, are far from typical. How can the fears and yearnings of the masses be adequately “reflected” once these elites have finished with the product? Maybe some violence in American films gets there not because the crowd secretly wants it but because Hollywood creators compete in pushing the envelope. Once more we need a story about how widespread opinions get incarnated in the work of an unrepresentative group.

In sum, reflectionist criticism throws out loose and intuitive connections between film and society without offering concrete explanations that can be argued explicitly. It relies on spurious and far-fetched correlations between films and social or political events. It neglects damaging counterexamples. It assumes that popular culture is the audience talking to itself, without interference or distortion from the makers and the social institutions they inhabit. And the causal forces invoked–a spirit of the time, a national mood, collective anxieties–may exist only as abstractions that the commentator, pressed to fill column inches, invokes in the manner of calling spirits from the deep.

Primate see, primate do

This isn’t to say that society has no impact on films. Of course it does. But we understand that process best by taking film as film.

Film critics serve us best when they explore how a film uses the medium to yield its effects. Critics can enlighten us about how filmmakers work with their givens (subjects, themes, genres, artistic traditions, star personas) and generate an experience shot through with meanings, feelings, and ideas. We should recognize that a large part of any movie is the result of will and skill, not the passive reflection of vague social turmoil. There will be some unintended effects too, of course, but we can try to understand those as coming from specific conditions of production practices, traditions, and creative options.

One first step, for example, would be to consider Dawn of the Planet of the Apes as following the plot pattern of the revisionist Western.(Spoilers follow.) The humans, like settlers in the west, need resources held by the apes, who live in self-sufficient harmony with nature. They wish others no harm. A well-meaning emissary from the humans, Malcolm, leads a team into ape territory to tap an energy source. Thanks to Malcolm’s promises of peaceful coexistence, humans and apes become friendly. But other members of Malcolm’s team don’t trust the apes and provoke violence. There is also the brooding ape Koba, who wants revenge for his mistreatment in experiments. The peace treaty is broken by both sides.

Koba, Caesar’s friend and rival, escalates the war with the humans when he discovers the cache of weapons. While Caesar tries to keep Koba from fomenting rebellion, Malcolm must try to restrain the humans’ leader, Dreyfuss. This is a familiar duality: the unruly tribal brave hot for vengeance who must be disciplined by the wise chief, and the sensible lieutenant who tries to restrain his rapacious superior.

The science-fiction premise has been shaped to fit the familiar pattern of liberal Westerns, in which blame can be placed on weak, cowardly, vengeful, or power-hungry individuals who block well-meaning leaders from finding peace. The classic equivocation of Hollywood film (there’s always an element that says, “Yes, but then there’s…”) is well summed up by the ambivalent to-camera glare of Caesar that begins and ends the movie: Angry? Sorrowful? Defiant? Implacable? Your mileage may vary.

The political themes are sculpted in another way, through family parallels. Caesar has a wife, Cornelia, and a son, Blue Eyes. Malcolm has a wife, Ellie, and a son, Alexander. The prospect of peaceful coexistence between human and ape is encapsulated in the two families’ growing fondness for each other. The parallels are sharpened by contrasts. Alexander comes to accept the apes, while his more rebellious adolescent counterpart Blue Eyes temporarily aligns himself with the false father Koba—only to prove himself loyal to Caesar at the climax.

By contrast, Dreyfus and Koba are lone males, without women or offspring. Granted, we are allowed some sympathy for both: Koba has been mistreated by humans, and Dreyfus has lost his family in the collapse of civilization. Still, Caesar is morally superior to both because he has lived in each world harmoniously. Before the final battle, the wounded Caesar gets to recall his first human family, typified by his father figure, on video.

Onto the settlers vs. Indians plot, then, is grafted what film scholars have called a “family adventure” pattern, one that became prominent in the 1980s and 1990s with E. T.: The Extraterrestrial, Jurassic Park and other films seeking “four-quadrant” success. The result is more made-in-Hollywood archetype than grassroots allegory.

My sketch is Film Studies 101 and needs plenty of nuancing. To go further we should consider how this movie, or any movie, puts flesh on its plot bones. How does the film handle point-of-view and exposition? How does it generate sympathy or antipathy? How does it create character conflicts both external and internal? Does it accord with the sharply contoured plot architecture characteristic of US studio filmmaking (and maybe popular literature too)? If I were trying to do a finer-grained analysis of Dawn, I’d try to understand how the Western and family-adventure templates intertwine with these factors and gain force as the film unfolds.

The point would be not to suggest that these plot patterns reflect the attitudes or anxieties of the audience, let alone a national psyche. Rather, the patterns are chosen by the filmmakers because they have proven emotionally appealing to at least some viewers (and apparently in cultures outside the US). And they can be fashioned to accord with contemporary norms of moviemaking. Instead of passive reflection, we have active creation.

It isn’t all controlled by the filmmakers. Like all actions, filmmaking can have unintended consequences. If some members of the audience respond in the way the filmmakers wanted, so far, so good. If the results are grasped in ways that the makers didn’t expect or prefer, that comes with the territory too. Mass-market filmmakers take inherited forms and tweak them in new ways. The audience, in its turn, appropriates what it’s given, sometimes in predictable ways, sometimes in unpredictable ones. No national psyche is needed for this process to keep rolling.

Instead of reflection, better to think of refraction, the bending and reconfiguring of social themes under the pressure of filmmaking traditions. We understand mass-market films better when we see them as, sometimes opportunistically, grabbing material from the wider culture (whether that material reflects mass sentiment or not) and transforming it through narrative and stylistic conventions. That transformation, or rather transmutation, is central to the artistry of popular entertainment.

Movies are worth studying for themselves, not just as channels for Op-Ed memes. Critics who are sensitive to the art, craft, history, and business of cinema will be able to enlighten us about all aspects of a film, including its political ones.

Jeff Smith’s new book, Film Criticism, The Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds examines how critics of the 1950s found allegories of resistance to HUAC in movies made at the time. It’s a good reminder that this sort of reflectionist criticism goes back pretty far.

In tune with Jeff’s argument, in an earlier entry I argued that reflectionist readings of popular cinema intensified during the 1940s. But our best critics pushed back. Parker Tyler proposed that movies don’t so much reflect social myths as they invent their own, and he suggested that the process follows the zany logic of dreams. Otis Ferguson, James Agee, and Manny Farber mostly avoided Zeitgeist explanations and talked about films’ implications in relationship to art, craft, and other media and artforms. I survey their work in a series of recent entries: on Ferguson, on Agee, on Farber (here and here), on Tyler, and on their originality, their cultural context, and their legacy.

The pie chart come from the MPAA report on 2013 moviegoing, p. 11.

For a wide-ranging and skeptical examination of one aspect of this topic, there’s Alan Hunt’s article, “Anxiety and social explanation: Some anxieties about anxiety,” Journal of Social History 32, 3 (Spring 1999), 509-528.

Peter Krämer developed the concept of the family adventure film in contemporary Hollywood. See his “Would You Take Your Child to See This Film? The Cultural and Social Work of the Family Adventure Movie,” in Steve Neale, ed. Contemporary Hollywood Cinema (Routlege, 1998), 294-311.

If there’s an allegory in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, perhaps it’s a Bolshevik one. Josef Stalin was known as Koba, which would make Caesar a Lenin figure and Rocket a stand-in for Trotsky. (I doubt that the conservative Mr. Douthat would welcome this reading.) If the reference is intentional, it provides a good example of how a Hollywood film simply seizes cultural flotsam willy-nilly, perhaps to give intellectuals something to ponder. As Christopher Nolan explains of his Batman trilogy: “We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks.”

Parts of today’s sermonette are pulled from an essay published in Poetics of Cinema in 2008. That essay also charts areas of control that filmmakers and audiences enjoy. Another entry on this site dealt with these questions in relation to The Dark Knight and, again, the good, grey Times.

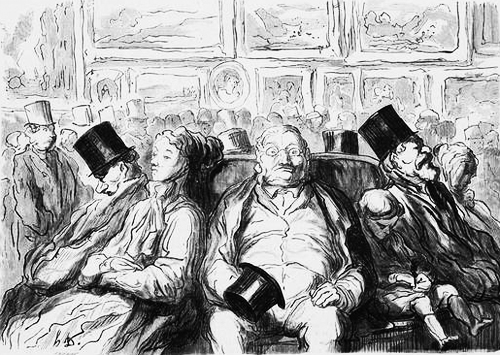

Daumier: Types Parisiens (1840-1843): “Ah, I can see my street, there’s my house, there’s my garden and my wife, I can see Laurent – Oh, I have seen too much.”

Gas food lodging: The best job in the world has its downside

Honoré Daumier, Exposition des Beaux-Arts, 1869.

DB here:

Over the last couple of years, I’ve been worried about those critics who must suffer the indignities of film festivals. I became aware of the hazards when I saw this exchange on Indiewire about James Gray’s The Immigrant:

Critic: Do you see this as your most emotional work?

James Gray: I don’t know, I mean I hope so. I know this sounds phony but I don’t start out on a project going, “I’m going to make an emotional work,” you know what I mean? You try to tell the story directly and honestly and with passion…

(A server interrupts to make sure we’re OK and leaves.)

Gray: I love France, I love the French, I’m ready to go home. Three days it took me to get my underwear back from the laundry. Also the worst concierge service in all of human history. I had tickets for all these guests of mine, and they said “Oh, we’ll slip it under your door,” and like seven hours later they lose the…anyway, I’m sorry.

Critic: No, no. Getting a glass of water at this hotel takes half an hour.

Gray: Yeah, it’s like scaling K2.

Mr. Gray, they say, is an amusing guy, so perhaps his complaints were wry jokes. I hope not. These slights and discomforts deserve to be recorded. They might seem minor to someone not professionally employed to fly to Cannes, but they’re typical of the hazards critics submit to for our sake. Curious, I looked into the recent adventures of some high-profile writers.

In all, critics bear their indignities with remarkable aplomb. They are unfailingly generous with praise when things are going well. Take the communiqués of Meredith Brody. Her encounters with famous people (luckily for us, she knows everyone) mingle with tales of fashion and delectable dining. As one who misses old Hollywood, I’m pleased that the festival scene has its Hedda Hopper. Here’s a bulletin from Telluride:

With the kind permission of Steve Ujlaki, dean of the Loyola Marymount University School of Film and Television, I was able to join his table for dinner at Rustico at 6, down a lovely plate of veal with mushrooms, and still make Serge Bromberg’s 7:15 “Retour du Flamme.” . . . It took me a while to find Alice Waters’ rented house, tucked away at the top of a steep street, but inside I find great wine, charcuterie, cheese, bread, chocolate, and refugees from the festival’s starriest party, to which I hadn’t been invited. . . .

I told Alexander Payne I was sad that they hadn’t scheduled an additional screening of the 1965 Italia film “I Knew Her Well” that he’d introduced night before last. . . . And maybe he was pulling my leg, but he said something about it being scheduled at some cinematheque in his home state of Nebraska, where he lives part-time. . . . Tom Luddy arrived in a dazzling Russian constructivist cashmere sweater, which his wife, stylist Monique Montgomery, had found at the Alameda Flea Market. He was thrilled that Dave Eggers and Vendela Vida had so enjoyed their first visit to Telluride that they’d become lifers.

And from Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato:

Walking back from “La Grande Illusion” last night, I run into Haden Guest (of the Harvard Film Archive) and Rani Singh of the Getty Institute, on the way back to their hotel. Days ago I told Haden I wanted to introduce him to Steve Ujlaki, Dean of the Loyola Marymount University School of Film and Television; it turns out they met accidentally on their own, in a fascinating-sounding wine bar, although they didn’t get around to actual introductions. I realized it must be Haden Steve and Jackie were talking about when they said that he was elegantly dressed, “in a pork pie hat and linen jacket.” I confirm this by showing him pictures of them from the amazing dinner we’ve just shared.

I frustrate both Haden and Rani by describing the meal and not being able to tell them the name of the restaurant. That’s something that annoyed the hell out of me when I was regularly writing about restaurants and people would tell me they’d just been to a place I would love and then be unable to tell me its name or address. I can show them a picture of the façade of the place, but it’s hard to read the sign. . . . A last lunch at Bertino: prosciutto e melone, straw and hay with sausage sauce, tagliatelle with ragu. Only a glance at sparkling wine (dare not) and a heavily-laden dessert cart (better not).

The churlish will object that the films screened get little discussion in these flavorsome pieces, but that misses the point. The function of most festival reviewers is to function as a DEW system, or a first filter. They must signal those buzzworthy films that if we’re lucky, we’ll see a few months or years hence. Their task is to predict the winners. (Indeed, their coverage helps create the winners.) Given that the films will be over-discussed in the months to come, why not share with us the more ephemeral joys of the festival atmosphere–the parties, the food and drink, the networking, the celebrity bons mots?

When it comes to evoking la dolce vita of the festival circuit, no one surpasses Mark Adams of Screen Daily/ Screen International. Consider his 2012 description of the annual Arabian Nights party at the Emirates Palace Hotel at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival.

The party aims to replicate – as only a five-star hotel can do – the desert experience, and is set up with food-stands a-plenty as well as singing, dancing, a Western-style DJ (very popular), shisha pipes – for those who partake – and even chill-out seats out on the sand with the possibility of a close encounter with a camel.

In fact this party has developed into a must-go-to event for festival regulars, with an elegant and laid-back vibe that is a perfect counterbalance to the excitement of the opening night bash and the champagne excesses of the Möet & Chandon event.

Champagne excesses? Tell us more, especially the classy parts.

The nice thing about the Moët & Chandon bash is that it is delivered with a certain class. The champagne was chilled and tasty, the asparagus risotto delicious and the delicate desserts delightful. Plus there were fire-eaters, a dancer sprayed silver and a woman dancing in an oversized birdcage….

But while the Moët party was certainly a classy affair – and with a strict invite list it keeps things modest but classy – it all rather pales when you head back into the Emirates Palace hotel and its cavernous golden corridors, gleaming hallways, splendid domed foyer and sheer sense of confident opulence….

Gold and marble are the key aspects to the hotel. Much has been written about the gold ingot vending machine in the foyer, but love it or loathe it there is no denying the sheer visual impact of the building, which was designed by architect John Elliott, and which opened in 2005.

Forget the 1.3km of white sandy beach, the private marina and the two helipads…the Emirates Palace hotel is all about scale. It is 1km from wing to wing (100 hectares total area); there are 102 elevators (I’ve only used two) and 1002 chandeliers, and some 5kg of pure edible gold is used per year for decoration on desserts.

At a period when people are losing their jobs, not getting jobs, losing their savings, finding themselves unable to save, and generally suffering from a depressed economy and a failing social-services system, it’s entirely appropriate that Adams spare a thought for those less fortunate than his hosts.

Sadly that self same edible gold on some very nice strawberriess at a Swedish reception was the nearest I’ve come to getting my hands on the real thing. . .

He’s quite aware that not every venue can splash out this way. The Transylvania Film Festival gamely makes do.

Even the faded and empty Continental Hotel on the edge of the square was being used for a costume exhibition that seemed to fit perfectly into the crumbling main entrance hall of the hotel, with its musty smell and peeling, once-grand ceiling.

And Adams reminds us:

Maybe it’s a sign of the times, but even movies are reflecting the stark fact that expensive hotels are beyond the reach of many, and camping or caravanning are other options. Camping was very much the thing in Cannes opener Moonrise Kingdom. . . .

Still, even if you stay in fine digs, there are those hazards. Without hesitation Adams throws a spotlight on the dangers of being a festival-going critic–plagued by officious doormen, long queues, and chattering cinephiles. Even the weather sometimes fails to cooperate.

After stints at the Venice and Toronto film festivals let me tell you, my capacity — let alone enthusiasm — for queuing is pretty much depleted. Yes, getting there nice and early does guarantee you a seat but standing in line is an intrinsically wearying pursuit as you stave off boredom by waving to friends, checking e-mails and becoming more and more annoyed as sly folk cajole or charm their way into the line ahead of you. . . .

At Venice this year, most of the early press screenings (which sometimes mixed in members of the public) were held at the cavernous Darsena cinema. With 1,300 seats available there’s always a good chance you’ll get in, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t a variety of ruses tried by some to force their way into the queue at an earlier point. Some try the old ‘friend holding a place’ routine; others adopt the ‘phone glued to ear and not really aware there was a queue’ policy, while some are just plain rude.

Mind you, it was so hot in Venice that the outdoor queue was rather wearisome, though at least the security folk didn’t snaffle water and liquids of any kind as they did in Cannes this year. Oddly there were three queues set up for the Darsena depending on your badge — from priority daily press through to periodicals — and all were let in at exactly the same time. . . .

Toronto favours long, winding queues that weave back and forth, like being in a bank or an airport baggage drop-off. In the case of screenings at the Bell Lightbox this also involves going up escalators, marshalled by grinning volunteers and festival folk with annoying headsets. But while frustrating they are quite well organised — until you are left outside a film that is late starting due to a digital problem, and have to put up with film folk around you pontificating on every film they have seen.

Fortunately, you can get away from the grind occasionally. Unlike Brody, who sandwiches her gustatory adventures between screenings, Adams favors a vacation. Even during R & R, however, he’s on the job, passing along his musings on cinema.

Time for a well-earned holiday with friends and family down in the bakingly hot Tarn region of southern France. Blessedly it is an area not favoured by hordes of British tourists but — rather sadly — it lacks a plethora of multiplexes to catch up on the latest film fare.

There was not even a local film festival to overlap with my trip, unlike a holiday in Umbria a few years ago, where a tiny and picturesque hilltop town was staging a Mike Leigh retrospective. And no, much as I love Mike, I didn’t hang around to catch his appearance.

While floundering in the pool, tanning in the 37 degree heat, sampling the delightful variety of Gallic wines and sweating on a baking-hot tennis court were all fine distractions, let’s face it, you can’t beat a good movie.

I wrote the foregoing a year ago, but I decided not to post it. I thought that the trend I’d spotted had faded. Film critics seemed to have given up their scintillating travelogues for the humdrum task of discussing movies. But a recent report from Anne Thompson made me decide to revive the old piece. A couple of days ago, Thompson took off for Karlovy Vary.

I flew from LA to Paris en route to the 49th Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (KVIFF) on a 500-seat double-decker Air France A380 that is the largest passenger aircraft in the world. Lufthansa and Emirates Airlines also fly them. It’s the smoothest, quietest flight ride I’ve ever had, you barely noticed the plane taking off.

I walked, “Snowpiercer” style, through the economy steerage, up the curved staircase at the tail and back through business and first class, which features ten full sleepers. The three-year-old jumbo jet had video footage of three live cameras mounted on the nose, belly and tail.

Cool.

So far, so good. But where are the eats?

Later that night I ran into Gibson and his long-time publicist Alan Nierob in the VIP basement lounge of the Grand Hotel Pupp, as the opening night party raged through many rooms above, with lavish spreads with everything from roast beef, aspic and deviled eggs to tongue-melting fresh sword steaks grilled on demand. He [Mel] showed me his latest movie-star tattoo.

On cue, Meredith Brody posts a culinary comment.

ps: two things: I know it would be kinda a busman’s holiday, but did you see any movies on the plane? AND tongue-melting sushi?!

As if in reply, Thompson’s second day report features more tastiness and adds a picture and a comparison of film to–what else?–food.

I interviewed achievement-award-winner Mel Gibson on video (we’ll post soon) before the official festival dinner at the Grand restaurant. I nibbled at a paté of duck liver and fois gras with cherries and beetroot as I chatted with the city Mayor (who runs a film club) and the Czech Minister of Culture, who is a rare Roman Catholic in a country of post-Communist atheists….

I interviewed achievement-award-winner Mel Gibson on video (we’ll post soon) before the official festival dinner at the Grand restaurant. I nibbled at a paté of duck liver and fois gras with cherries and beetroot as I chatted with the city Mayor (who runs a film club) and the Czech Minister of Culture, who is a rare Roman Catholic in a country of post-Communist atheists….

I’ll report anon on what I do see–of the 200-some films on display are a tempting smorgasbord of the best of the international festivals.

I think I speak for other readers: Festival critics, we know you face moments of despair. But make the sacrifice. Soldier on. Tip us to strong sweepstakes entries. (Thompson on Calvary: “This will make many critics’ ten-best lists.”) And don’t spare us lifestyle details.

Full disclosure: Kristin and I have praised Lillooet Fox‘s waffles at VIFF.

The Rhapsodes: Afterlives

Ali–Fear Eats the Soul (Fassbinder, 1974). 35mm frame.

The original entry at this URL, published 2 April 2014, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

I explain the development of the book in this entry.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

Thank you for your interest!