Archive for the 'Film criticism' Category

Good, old-fashioned love (i.e., close analysis) of film

Kristin here:

On April 10, I received a message from Tracy Cox-Stanton, the editor of a new online journal, The Cine-Files. This journal is run out of the Cinema Studies department of the Savannah College of Art and Design. The message was an invitation to contribute to the fourth issue of the journal, of which, I must admit, I had been unaware until that time.

The invitation included two options. One was: “Offer a brief (1000-2000 word) reading of a film “moment” that considers how some particular detail of a film’s mise-en-scène (a prop, an actor’s gesture, an aspect of costume, a camera movement, etc.) illuminates the film as a whole, helping us understand the relationship between a film’s details and the overall “work” of cinema. We encourage the use of film stills.”

Having lived for decades in an academic publishing world which tended to discourage the use of film stills, I found this a cordial invitation indeed. Still, my initial thought was, if I had an idea for a study of a film “moment,” I should put it on our blog. We bloggers tend to become selfish about ideas for compact, easy-to-write analyses.

The other option, however, seemed more feasible: to respond to three questions as an online interview. It seemed a simple way of encouraging a promising new journal, and I accepted.

The Cine-Files is an appealing project. In place of the recent focus on cinephilia , which has often encouraged self-absorbed pieces in which film-lovers ponder the nature of their own love of film, “Cine-Files” implies good, hard study, with research resulting in files full of data that can result in informative, meaningful history and analysis.

It reminds me of The Velvet Light Trap in its heyday, though its format is quite different. In 1973, when David and I first arrived at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, graduate students in the young cinema-studies program and coordinators of film societies (showing 16mm prints by the dozen each night) published this extraordinary magazine. It was a combination of auteur worship, studies of studios, and genre analysis. The Velvet Light Trap was a film journal in an era when such things were rare and graduate students could be tastemakers.

The Cine-Files is similarly focused on films in their historical context. It is semi-annual and alternates open-topic and themed issues. Its first themed issue was on the French New Wave. Remarkably for a new journal, it attracted comments from experts such as Dudley Andrew, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and Richard Neupert. The newest issue, to which I contributed, is on Mise-en-scène. The topic for interviews, however, was a bit broader: “close readings.” The new issue, #4, has recently been posted, and my interview is here. There is also a call for papers for the fifth issue, an open-topic one, here.

Tracy has kindly agreed to our re-posting my responses to the three questions about close readings here. We have slightly modified the original post to suit this venue. We thank Tracy for a set of questions that provoked what we hope are interesting responses.

What is at stake in close reading?

To begin with, I don’t use the phrase “close reading.” I prefer “close analysis.” The notion of close reading is presumably a holdover from the 1970s and 1980s, when semiotics was a popular approach in film studies. Cinematic technique was thought to be closely comparable to a language, with coded units and grammar. Although there are some comparisons to be made between the techniques of cinema and a language, I don’t think the similarities can be taken very far.

“Reading” to me implies that interpretation is one’s main goal in looking closely at a film. I usually use interpretation as part of analysis, but it is seldom my main goal. Analysis, loosely speaking, to me means noting patterns in the relationship of the individual devices in a film (devices being techniques of style and form) to each other and figuring out why those patterns are there. What purposes do they serve?

What is at stake in close analysis depends on what sort of analysis one is doing. I’m assuming here that the subject is scholarly or semi-scholarly analysis intended for publication. My own purposes for analysis fall into at least these categories:

1. The simplest reason to analyze a film would be to find out more about it because it’s appealing or intriguing.

I’ve written essays on Jacques Tati’s Les Vacances de M. Hulot and Play Time, in both cases because I admired them and wanted to be able to understand and appreciate them better. I go on the simple assumption that we can only be entertained and moved by films to the degree that we notice things in them. Complex films can’t be thoroughly comprehended on a single viewing or even several viewings. Sometimes you may need to watch them more closely, not in a screening but on a machine, like a flatbed editor or a DVD player, that lets you pause and slow down the image.

2. One might analyze a film in order to answer a question, often to do with the nature of cinema in general.

My essay on “Duplicitous Narration and Stage Fright,” as the title suggests, arose more from my interest in a particular, unusual device, the “lying flashback,” than from a particular admiration for the film.

3. You might want to make a case that a film is significant and suggest why others should pay attention to it.

One example would be the rediscovery over the past few years of Alberto Capellani’s French and Hollywood silent films. On this blog site, I posted two entries, “Capellani ritrovato” and “Capellani trionfante,” analyzing some scenes to support the claim that Capellani was one of the most important stylists and innovators of the era from 1905 to 1914.

A very different case came with The Lord of the Rings trilogy by Peter Jackson. I had written a book, The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007), primarily on the marketing and merchandising surrounding the film and on its many influences. I would not claim Jackson’s film to be a masterpiece, but there was such a great backlash against it, mostly by literary scholars of Tolkien, that I thought it might be worth counterbalancing their opinions. I wanted to make a modest defense of the film as containing some excellent passages and effective decisions concerning the adaptation process. So I wrote two essays based on that argument. (See the codicil to this entry for references.)

4. Close analysis can be vital for writing about film history.

For example, David and I have studied films closely to determine the stylistic and narrative norms of specific times and places. We’re also interested in finding films that were innovative in relation to those norms. Rather than examining a single film closely, such an approach involves analyzing many films to find commonalities and divergences. For example, David has studied the norms and innovations of modern Hong Kong cinema (Planet Hong Kong, Harvard University Press, 2000; second edition available online at Observations on Film Art).

Another such project was my Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique (Harvard University Press, 1999). There had been many claims in academic and journalistic writings that the norms of Hollywood storytelling had declined after the end of the studio era and that we were now in a post-classical era. Such claims didn’t tally with what I was seeing in the best Hollywood films, the ones held up as models within the industry. I did case studies of ten such films, dating from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, going through each scene by scene. I showed how classical techniques like protagonists’ goals, dangling causes, dialogue hooks, redundant motivation, and other traditional norms were still pervasive in modern Hollywood. I chose the ten films because I liked them, but others would have made my point equally well.

Please tell us about something that couldn’t be understood without a frame-by-frame attention to detail.

I don’t think most close analysis goes to the minute detail of examining a film frame by frame. Sometimes it’s necessary, especially with French and Soviet films of the 1920s or with some experimental work. There can be lots of ways of looking closely at the parts of a film and relating them to other parts.

Take a simple example, in my essay on Late Spring, I reproduced eleven shots across the length of the film that include a sewing machine off to one side of the frame–or, in one case, the space where the machine had been. No two of these shots are the same, though they often are only small variations on each other, with the machine closer or further from the camera, sometimes on the left, sometimes the right, and so on. I even missed a couple, the second and third shots immediately below, so there are actually thirteen variants. (DVDs do have their advantages. It’s not so easy going back and forth across a film looking for such repetitions in a 35mm print.)

The series culminates late in the film, after the daughter has married and left her widowed father living alone. We see a similar framing along a corridor, and the space formerly occupied by the sewing machine is empty. (See below.)

The daughter doesn’t use this sewing machine in the course of the action, and no one mentions it. Many viewers probably vaguely notice that there is a sewing machine in the house. A few may notice its eventual absence late in the film. But even someone who watches the film over and over and at some point notices that there is a meaningful pattern of the sewing-machine shots would not be able to describe it. I suspected that the sewing-machine shots were small variations on each other, but were there some repetitions? How many were there? I was only able to get a good understanding of how the motif worked by photographing all the shots (or so I thought at the time) and comparing them side by side—and having the luxury to reproduce all eleven frame enlargements in my book.

What point is there in analyzing such a motif in detail? If we admire Claude Monet for taking infinite trouble to capture tiny changes of light on haystacks or lily-ponds, why not devote the same respect to one of the cinema’s greatest directors? To go back to my point at the beginning, we can only appreciate a film to the extent that we notice things about it. I take it that the critic’s job is to notice such things and point them out for the enrichment of others who don’t have the time or inclination to do close analysis.

How do digital technologies allow us to engage in “direct” criticism that bypasses traditional written criticism?

One obvious answer is that digital technologies allow anything that could be published in printed form to be offered online. Whether written for consumption via the internet or already published and then scanned to be posted, online criticism offers some obvious advantages. There is no lag in publication time and no need to hunt for a press. Of course there are disadvantages too: no real guarantee of long-term survival, often no academic reward for publishing through a non-refereed process. David and I have posted many entries involving close analysis on this blog. (I discuss the history and approach of Observations on Film Art in an essay for the first issue of the online journal, Frames Cinema Journal: “Not in Print: Two Film Scholars on the Internet.”)

Perhaps more interesting is the question of what critical tools digital technologies offer for analysis itself. In past decades, David and I had to rig up elaborate camera-and-bellows systems to photograph frames from prints of films—as well as to travel far and depend on the hospitality of archivists to gain access to those prints. Nowadays DVDs and Blu-rays bring hitherto rare films to the critic, and readily available players and apps allow for easy capture of frames for illustration purposes. If the essay or book based on close analysis using such tools is to go online, it also becomes practical to reproduce a great many more frames as illustrations than would be possible in a print publication. David’s e-book edition of Planet Hong Kong permitted him to publish most of the illustrations in color, an option that would have been prohibitive in a university press volume.

The possibility of using short clips as illustrations in an article or book is very promising, especially once electronic textbooks get past the trial stages. I made a modest contribution to the use of clips as examples for introductory students with “Elliptical Editing in Vagabond”; this was done with the cooperation of the Criterion Collection and posted by them on YouTube in 2012. Other extracts appear as proprietary supplements for Film Art: An Introduction. Since then, David has offered three online lectures analyzing editing, the history of film style, and the aesthetics of CinemaScope; see our Videos listing on the left.

Video essays analyzing films are still a new format but show great potential. Their usefulness will depend on how the issue of copyright plays out. At this point, I’m hopeful that showing clips as part of an analytical study will become established as fair use, as clearly it should be. Being able to use moving images complete with sound as well as still frames from films will be an extraordinarily useful tool.

I hope that critics using digital tools will take the trouble to create analyses as complex as one can achieve through description in printed prose. This would mean editing together stills and short segments from across a film, recording voiceover comments, adding graphics where useful, and so on. Close analysis of this type will always be a labor-intensive process.

The analyses mentioned in this article have been published in collections. “Boredom on the Beach: Triviality and Humor in Les vacances de M. Hulot,” “Duplicitous Narration and Stage Fright,” “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception,” and “Late Spring and Ozu’s Unreasonable Style” appear in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988). “Stepping out of Blockbuster Mode: The Lighting of the Beacons in The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003),” was published in Tom Brown and James Walters, eds., Film Moments (British Film Institute, 2010), and “Gollum Talks to Himself: Problems and Solutions in Peter Jackson’s Film Adaptation of The Lord of the Rings” appeared in Janice M. Bogstad and Philip E. Kaveny, eds. Picturing Tolkien: Essays on Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings Film Trilogy (McFarland, 2011).

Late Spring (1949).

All play and no work? ROOM 237

Room 237 (2012).

DB here:

Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 gathers the thoughts of five people concerning the deeper, or wider, or just awesomer meanings evoked by Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Those thoughts will strike many viewers as fairly far out there. Me, not so much.

Over the top

Room 237 adroitly blends several documentary genres. It recalls Cinemania and Ringers in its investigation of fan cultures. But instead of focusing on the personalities and lifestyles of the fans, Ascher concentrates on their readings of the movie. We never see the commentators. In this respect, it evokes the newly emerged genre of video essays as practiced by Kevin B. Lee and Matt Zoller Seitz. Yet it doesn’t offer itself as an earnest contribution to the critical conversation because Ascher freely intercuts stills and shots from other films, often to ironic effect.

In all, his film has the quizzical, gonzo flavor of an Errol Morris movie, minus the talking heads. But Morris is as interested in people as he is in their ideas. Ascher is interested in the ideas, and the way they swarm over and burrow into a film we thought we knew.

So he performs the sort of surgery more appropriate to the Zapruder footage. In the boldest test of cinematic Fair Use I’ve ever seen, a great many clips from the Warner Bros. release are run, slowed, halted, backed up, blown up, and overwritten as support for the interviewees’ claims. Ascher never tries to counter their arguments; at times he supplements them with extra evidence.

The results seem, to many, at best far-fetched and at worst (or best, from an entertainment standpoint), wacko. One of Ascher’s interviewees believes that The Shining is a denunciation of the genocidal destruction of Native Americans. Another takes the film as an exploration of the Theseus myth. Another believes that the film makes references to the Holocaust. Another finds a welter of subliminal imagery pointing to “a dark sexual fantasy.” Another sees the film as Kubrick’s apologia for staging the faked footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing.

Are these interpretations silly? Having spent forty-some years teaching film in a university, I found much of them pretty familiar. Some of the specifics were startling, but I’ve encountered interpretations in student papers, scholarly journals, and conference panels that had a lot of similarities.

If you think that this just proves that all film interpretation is ridiculous, you can stop reading now.

Because most film enthusiasts think that at least some movies need interpreting. We assume that like artists in other media, some writers and directors are using their medium to transmit or suggest meanings. And if a movie doesn’t express its makers’ ideas, perhaps it can still bear the traces of ideas out there in the culture. This “reflectionist” idea, tremendously popular among both journalists and academics, allows us to interpret even escapist fare.

Our interpretive itch has been around for a long time. Centuries of commentary have accrued around the Bible, the Torah, the Koran, and other texts deemed sacred. Secular texts, from Homeric epics to last month’s bestseller, have been scoured for hidden meanings too. The search hasn’t just been confined to literature, of course. An entire school of art history, called iconology, has devoted itself to deciphering objects, compositions, and other features of paintings. Even musical pieces without verbal texts have been “read.”

If at least some movies need interpreting, The Shining would seem to be a prime candidate. The film creates many questions about the reality of what we see and hear, and it seems to point toward regions larger than its central tale of terror. The director was one of the most ambitious filmmakers of the twentieth century, a film artist who could use a genre-based project like the famously puzzling 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to convey ideas about the place of human history in the cosmos. Why couldn’t he do the same thing with a Stephen King horror novel?

What’s wrong, then, with the five critics’ readings? Why do many viewers find them strained and forced, even loopy? One of the many virtues of Room 237 is that it forces us to ask: What do we do when we interpret movies? What makes one film interpretation plausible and another not? Who gets to say? What historical factors lead ordinary viewers to launch this sort of scrutiny?

All in the family

We all grant that movies have conventions. In an action picture, the bad guys have extraordinarily bad aim, except when it comes to winging the hero or plugging his best friend. Similarly, film criticism relies on a batch of conventions about what things to look for and how they should be talked about. No quickie film review, for instance, is complete without discussing acting.

Interpretation, a central activity of film criticism, has its conventions as well, and the Room 237 interviewees make some moves that are common to interpretation in academe and elsewhere. For one thing, they assume that The Shining is more than a standard-issue horror movie. Most cinephile and academic critics would agree that we have to go beyond this movie’s literal level.

Some of the Room 237ers’ conclusions echo critically respectable interpretations already out there. One idea held by other critics is that the film is to some degree a parody or critique of horror conventions. Another is the conviction that the film says something about the repression of the Native American population. The Overlook Hotel is built on tribal burial grounds, a history that hints an earlier, oppressed America returning to avenge a great wrong.

Other Room 237 interpretations don’t show up in the mainstream critical literature, but they aren’t unknown in wider traditions of interpretation. Take numerology. Some interpreters of Biblical scripture find multiples of seven to be of divine significance, and so does the Holocaust advocate in Ascher’s film. According to him, the novel Lolita, which Kubrick adapted, makes 42 a symbol of fate. In The Shining, it becomes a symbol of “danger and malevolence and disaster.” Why? Multiply 2 x 3 x7 and you get 42. Danny wears a jersey with the number 42, there are at one point 42 vehicles in the hotel parking lot, and 1942 is the year in which Hitler launched the Final Solution.

Similarly, anagrams aren’t unknown in some interpretive traditions. Scholars have claimed to find in Shakespeare’s plays encoded references to the real author (Marlowe or Francis Bacon or the Earl of Oxford). Ferdinand de Saussure, one of the founders of modern linguistics, whiled away his later years with detecting anagrams in Latin poetry. Joining up with this method, the interviewee who sees The Shining as an apology for faking the Apollo landing rearranges the letters on the room key to spell out MOON ROOM. And the moon, says the critic, is 237,000 miles from our earth.

I grant you that such cabalistic maneuvers aren’t common in film criticism. But plenty of others on display in Room 237 use the same reasoning routines that we find in consensus critical writing.

What do I mean by reasoning routines? When we interpret a movie, we’re making inferences based on discrete cues we detect in the film. What cues we pick out and what inferences we draw vary a lot, but the process of inference making tends to follow certain conventions.

Consider the claim that Kubrick is warning that we shouldn’t expect a conventional horror film. A more mainstream critic would point to the flamboyant performance of Jack Nicholson, at once grotesque, comic, and ominous. This would seem to be a strong ensemble of cues asking us not to take the film straight, and perhaps implying that it’s a send-up, in a grim register, of its genre. But none of our 237ers mention this cue as a basis for their interpretation.

Instead, they scan the setting for disparities. The hotel’s architectural features sometimes differ from one shot to another. A chair is present in one reverse shot of Jack, but in the next reverse shot, it’s gone. The hotel geography can’t be plotted consistently. Moreover, one of Wendy’s visions during her desperate flight through the corridors at the climax invokes the clichés of ordinary shockers: dust, cobwebs, and skeletons—all the paraphernalia that the film has studiously avoided up to this point. These anomalies encourage the interpreter to see the film as parodying typical horror movies. The 237 critics are picking out cues less obvious, they would say, than Nicholson’s over-the-top acting.

Making meaning, or making up meanings?

Ascher’s interviewees don’t always go for minute cues. They focus as well on many items that conventionally invite symbolic interpretation. Mirrors signal any sort of reversal, such as Danny’s backward steps through the maze or the film’s symmetrical beginning and ending. Something open—a door, a character’s eyes—suggests knowledge and acceptance; something closed, like elevator doors, suggests repression. If a character enters a space, that space can be taken as a projection of the character’s mental state, as when Danny nears his parents’ bedroom and gets into “his parents’ headspace,” as one 237 critic puts it. Another commentator suggests that Jack’s job interview at the beginning of the film might be entirely his hallucination, a question raised by academic critics as well. Such speculations on the border between the subjective and objective are commonplace in discussions of horror, fantasy, and that in-between register known as the fantastic.

Puns are another time-tested inferential move. You can find a cue in the mise-en-scene and then “read” it with a verbal analogy. Snow White’s Dopey on Danny’s door suggests that the boy doesn’t yet realize what’s going on; but when the dwarf disappears, Danny is no longer “dopey”. A crushed Volkswagen stands for Kubrick’s telling King that his artistic “vehicle” has obliterated the novelist’s original “vehicle.” Abstract patterns in carpeting become Rorschach tests: Are those shapes mazes? Phalluses? Wombs? NASA launching pads? Mainstream critics might not fasten on these particular cues, but many wouldn’t resist the urge to find puns. After all, even Freud interpreted a dream in which his patient got kissed in a car as exhibiting “auto-eroticism.”

The Room 237 critics, following tradition, let the cues and inferences lead them to what I call both referential and implicit meanings. Referential meanings involve concrete people, places, things, or events. Spielberg’s Lincoln refers to a specific historical context and people and events in it. Implicit meaning is more abstract and is something we might expect to be intended by the filmmaker. So, for instance, Lincoln could be interpreted as about the necessary mixture of principle and expediency in politics; to achieve virtuous policies, you may need to cut moral corners.

The 237ers make use of different degrees of referential meaning. The Shining makes clear references to the Native American motif, not only in the hotel’s décor but the manager’s line of dialogue indicating that the building rests on burial grounds. That line is a rather explicit cue, and one that many non-237 critics have taken up. In a similar vein are the mythological references; both Juli Kearns in the film and several academic critics have discussed the the maze/ labyrinth imagery as citing the legend of the Minotaur.

There are more roundabout cues to inferences about the Holocaust. Kubrick might have included a photo of Nazis or Prussian generals in the Overlook’s Gold Room salon, but he didn’t. So the critic defending the Holocaust reading has to look for what we might call “hidden references”—the numerology we’ve already seen, along with the German-made typewriter on Jack’s desk, which is an Adler (“eagle,” symbol of Nazism). There’s also a dissolve that, according to another critic, gives Jack a Hitler mustache.

The Room 237 critics gesture toward implicit meanings too. The Playgirl magazine that Jack is reading when he waits in the lobby suggests that troubled sexuality is at the center of this maze—a suggestion made more explicit in the fateful Room 237, where a beautiful woman, upon embracing Jack, turns into a haggard zombie. The references to both the North American and German genocides suggest the film induces us to reflect on the cruelty of those events. More broadly, one critic believes that the film has far-reaching thematic import: The Shining is about “pastness” itself, about coming to terms with history.

To be convincing, though, an interpretation can’t merely take a one-off cue to make references or evoke themes. What really matters are patterns.

Patterns of associations

Interpreters typically gather cues into patterns and then use them to bear thematic meanings. One instance of this maneuver comes early on in Room 237, when Bill Blakemore, proponent of the Native American genocide hypothesis, is attracted to a lone Calumet baking-powder tin, turned toward us on a shelf. Not only does the label show a tribal chief, but the plainness of presentation emphasizes the original meaning of calumet, the tobacco pipe used in Amerindian peace brokering. But that might be a one-off occurrence. Later, however, other Calumet tins are massed on another shelf–but turned from us. It’s not enough that the can has now been repeated. The change, Blakemore proposes, indicates that the original, straight-on image has turned into something hidden and dishonest—the destruction of the tribal population. The spatial opposition frontal/oblique has been made to bear a thematic difference between honesty and betrayal.

A similar duality, with a punning tint, is raised when Kearns traces how she came up with the Minotaur hypothesis. She points out that a skier poster (to her eyes, resembling a Minotaur’s silhouette) stands opposite a rodeo poster (“Bull-man versus cow-boy”). The poster led her to realize that the Minotaur sits at the center of a cluster of images that recur in the film. He presides over the labyrinth that is the hotel, which, Kearns argues, has an impossible geography, while the intertwined logo of the Gold Room recalls Theseus’s thread. In his alternate identity Asterios, the Minotaur suggests stars, which in turn suggest movie stars (who, we’re told, have stayed at the Overlook). The ski poster reads “Monarch,” which in a sense the Minotaur is, and we learn that royalty have visited the hotel too.

Or take the Holocaust reading. Apart from the fateful 42 motif, the Adler typewriter does other work. Its name (“eagle”) evokes the emblem of the Reich, but an eagle is also a prominent American icon. So the critic adds that Kubrick always uses an eagle to symbolize state power. How then to link it to Germany? The typewriter, as a machine, evokes the bureaucratic efficiency of Hitler’s mass deportations and executions. To back this up, the critic recalls Schindler’s List, in which typewriters figure extensively.

Such expanding clusters are common in interpretive activity because artworks often ask us to tease out associations. Early in The Shining, the Torrance family talks about the Donner party. We’re invited to see the reference as conjuring up slaughter, isolation in a snowbound environment, and the collapse of civilized restraints—just what the film will give us. Critics of all stripes track the dynamic of the artwork by creating associative patterns out of repeated elements. When Wendy and Danny watch the film Summer of ’42 on TV, it’s not the 42 that attracts the distinguished academic critic James Naremore. He links the embedded film about the sexual attraction between an older woman and a younger man to the moment when Danny runs out of the maze and kisses Wendy on the lips. These moments are part of a constellation of images and events marking the film as “flagrantly Oedipal,” in that it presents the son’s struggle against the hostile father. Naremore is able to build on this cluster to suggest that the film is unusual in rehearsing different, non-Freudian aspects of the Oedipus myth.

You might object that, unlike Naremore and other professionals, the critics in Room 237 build up associations from their personal experiences rather than what’s objectively on the screen. Blakemore says that he noticed the Calumet label because he grew up in Chicago near the Calumet River and as a child he gathered Indian pottery. Yet the conventions of mainstream movie reviewing allow critics to look inward too. Jonathan Rosenbaum opens his piece on James Benning’s El Valley Centro:

About halfway through I found myself, to my surprise, thinking about Joseph Cornell’s boxes, those surrealist constructions teeming with fantasy and magic—dreamlike enclosures that make it seem appropriate that Cornell lived most of his life on a street in Queens called Utopia Parkway.

The only difference between Rosenbaum’s associational links and Blakemore’s would seem to be the cultural level of the references. Why should the amateur not be allowed to import less arcane personal associations into an interpretation?

Finally, you might object that the Room 237 critics are too focused on trying to infer Kubrick’s intentions. Kubrick had wanted to make a film on the Holocaust at some point; he read Raul Hilberg’s Destruction of the European Jews and corresponded with the author. Kubrick also read Bruno Bettelheim’s Uses of Enchantment, a Freudian explanation of fairy tales; hence the Hansel and Gretel and Big Bad Wolf references in the film. One Room 237 critic says that Kubrick was bored after making Barry Lyndon and wanted to make a movie that reinvented cinema. Yet, again, journalistic critics commonly make assumptions about what the filmmaker is up to. Even academics, trained to believe in “the intentional fallacy” and to “never trust the teller, trust the tale,” can indulge in hypotheses about directorial purpose. In explaining the eccentricities of the lead performance, Naremore notes that in interviews, Nicholson reported that Kubrick told him that “real” performances aren’t always interesting.

Tie me up! Tie me down!

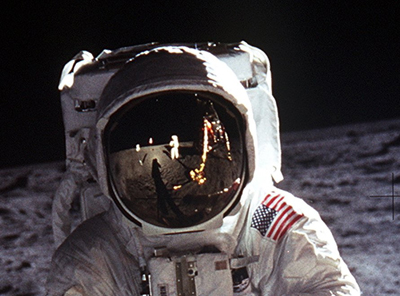

Apollo 11 moon landing, July 1969.

For mainstream film criticism, however, the patterns and the significance-laden associations they trigger have to be constrained somehow. Not everything is relevant to the implicit meanings of the film. This condition, I think, shows the real gap between the 237ers and the pros. One interviewee’s enthusiasm marks this difference: Kubrick, he says, is “thinking about the implications of everything that exists.” No mainstream critic would dare make this move.

What are the constraints on interpretation within the community of publishing critics, either journalistic or academic? Here are some common ones.

Salience: The patterns and associations are more plausible if they’re readily detectable– if not at first, then on subsequent viewings. The case gets stronger if the motif is reiterated along many channels—image, dialogue, music, sound effects, written language. The Native-American genocide association is moderately salient, present in both items of décor and in Ullman’s line about the burial grounds. Accordingly, many viewers have picked up on it. On the other hand, even repeated viewings don’t help us (me, at least) to identify the magazine as Playgirl.

Coherence: The patterns and associations are more plausible if they’re related functionally to the narrative—not just to single moments but to its overall development. Most critics writing about The Shining assume that it’s centrally about the disintegration of the family. They have gone on to relate this to the way that the delusions of patriarchy subject women and children to its control. (That common academic trope of “the crisis of masculinity” hovers nearby.) This thematic thrust can be traced scene by scene, and the motifs of fairy tales, American history, and the Minotaur can blend with specific plot twists and character presentation. Some of the Room 237 critics’ readings mesh with the arc of the narrative, but many, such as certain overlays during dissolves, seem unmotivated by narrative factors.

Congruence with other relevant artworks: The patterns and associations gain plausibility if they can seem congruent with other works by the same artist or in the same genre. For example, the uncertainty about whether Jack is imagining the Gold Room or whether it’s a genuine supernatural entity is characteristic of horror/ fantasy films. Here the 237ers are more in line with their mainstream colleagues. The unresolved ending, leaving us with a puzzle about whether Jack himself is a reincarnation of someone from the past, isn’t out of keeping with the ending of 2001. The room 237 itself, one of Ascher’s critics suggests, is a bit like the old man’s bedroom and the space pod in the earlier film.

Appeal to authorial intention: The critic’s case gains plausibility if people having significant input into the work claim the patterns and associations were deliberately put there. While rewatching The Shining, Nicole Kidman remarked of Kubrick:

“He always said that you had to make sure the audience understood key pieces of information to follow the story, and that to do that you had to repeat it several times, but without being too obvious about it,” Ms. Kidman said. “Here, in this scene, look at how there is this rack of knives hanging in the background over the boy’s head. It’s very ominous, all of these knives poised over his head. And it’s important because it not only shows that the boy is in danger, but one of those very knives is used later in the story when Wendy takes it to protect herself from her husband.”

Most mainstream critics would, I think, find that Kidman’s inference rings true. It picks up a fairly salient cue, it invokes a pattern involving the knives, and it squares with the unfolding of the narrative. She reports that Kubrick understood the need for patterns to have salience, and it seems quite likely that he was the sort of artist to use pictorial prefigurations like this. Note, though, that this shot exemplifies function-driven dramaturgy—foreshadowing—not thematic interpretation.

By contrast, consider the Room 237 critic who takes The Shining to be Kubrick’s apology to his wife for staging the fake Apollo 11 moon landing. As Ascher presents the case, it involves a long chain of causation. It starts from the claim that, whether or not NASA actually sent a crew to the moon, the landing that the public saw was staged. The project needed front-screen projection. Kubrick was the master of those special effects. He agreed to help film the fake landing. Later he felt guilt for it. So by making a film about a husband/wife conflict, Kubrick confesses to his mistake. This backstory would gain a lot of plausibility if a NASA staffer or one of Kubrick’s crew came forward to support any part of it, in the way Kidman offers testimony about Kubrick’s working methods. It would be even better if the Apollo tale could be tied to the specifics of the unfolding narrative. And it would be best if the interpretation of this film didn’t depend on a (questionable) interpretation of another film–the Apollo 11 footage.

The Apollo 11 argument illustrates the risk of appeals to intention: they tend to substitute causal explanations for functional ones. That is, they tend to look for how something got into the film rather than what it’s doing in the film. But that’s a risk that professional critics run as well when they appeal to intention. The problem is just more apparent when the causal story that’s put forward seems tenuous.

I’ve argued that the cue-inference method and the use of association to create patterns aiming at referential and implicit meanings are involved in all interpretations, staid or unorthodox. But the constraints I’ve just sketched aren’t so fundamental to interpretation as such. They typify the established critical institution, which includes journalism high and low, belles-lettres (e.g., The New York Review of Books), specialized cinephilia (eg., Cinema Scope), and academic writing.

Not everybody belongs to that institution. There are other arenas of film criticism, and there’s no mandate that discussion in those realms adhere to the constraints urged by professional criticism. Some readers prefer to muse on barely perceptible patterns, incoherence, unlimited association, and relatively unrestrained speculations about Kubrick’s mental processes. Fans like to think and talk about their love, and anything that gives them the occasion is welcome, no matter what any establishment thinks. To a considerable extent, Ascher’s film documents the habits of folk interpretation.

Some precedents

But why now? Why do amateur critics today launch these ambitious expeditions? The short answer, as so often, would be: Because they can. As Juli Kearns points out, it was thanks to VHS, then DVD, that she was able to scrutinize The Shining. Home video has allowed us, including all the obsessed among us, to halt and replay a movie ad infinitum—a process that Ascher’s own film freely indulges in. I think, though, that there are other historical factors that impel fans to dig ever deeper into the movies they love.

Most obviously, there’s the rise of the puzzle film, the movie that litters its landscape with hints of half-buried meanings. The vogue for this began, I suppose, in the late 1990s with films like Memento, Magnolia, and Primer. Even then, though, there were different constructive options. Primer called out for re-watching because much of its plot was obscure on a single pass; you had to examine it closely to figure out its basic architecture. By contrast, Memento’s principle of reverse chronology was evident on first viewing. I suspect that most viewers, like me, studied the film to pick up the finer points of its form and to try to disambiguate the Sammy Jankis plotline. Still different was Magnolia, with a perfectly comprehensible plot that planted a Biblical citation in its mise-en-scene. In this case, the extra stuff suggested a thematic level that might not be apparent otherwise.

Some critics have objected that the Room 237 critics turn Kubrick’s film into a mere puzzle movie, the implication being that puzzle movies are inferior forms of cinema. Yet I don’t see a good reason to scorn them. Assuming that films often solicit our cognitive capacities, I don’t see why artists shouldn’t ask us to exercise them. Cinema takes many shapes, and one critic’s puzzle (“Rosebud,” “Keyser Söze”) is another critic’s mystery. Some artworks throb with passion; some are more intellectual and austere. There is Mahler, and there is Webern. Even artworks with a lyrical or emotional dimension ask for decipherment and meditation too. Dante explained to his patron Can Grande della Scala that he had laid layers of non-literal meanings into The Divine Comedy. The poem, he explains, is “polysemous.” Its meanings are to be grasped and pondered upon in the manner of Scripture.

Long before puzzle movies came into fashion, literary modernism had assigned readers this sort of homework. The idea of loading every rift with ore was taken quite seriously by T. S. Eliot, who supplied footnotes to The Waste Land. Could you really hope to understand it without reading Jesse Weston’s From Ritual to Romance? James Joyce built so many layers into Ulysses that he had to take a critic aside and explain them to him, so the critic could then publish a guidebook to the novel. Finnegans Wake is supersaturated with references, puns, and esoteric meanings. If ever an artwork needed decoding, this is it. One of the earliest scholarly studies is called A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake.

In cinema, Peter Greenaway’s Tulse Luper series seems to be his bid for Joycean stature. More successful has been Godard, who in his mid-1960s films created an aesthetics of dispersal, a display of citational pyrotechnics that reaches its apogee in the Histoire(s) du cinéma. Surely this suite of films has engaged many critics in a process akin to puzzle-solving. More to our point today, we might see Kubrick’s films, especially 2001, as bringing aspects of high modernism into mainstream cinematic genres. We can hardly be surprised that after courting many interpretations of 2001 (whose subtitle cites a classic literary text), this director might be posing us similar tasks in a horror film.

Something else besides the rise of the puzzle film and high-modernist polysemy is probably responsible for the rise of this sort of fan dissection. Throughout history storytellers have experimented with creating what we might call richly realized worlds. Naturalist literature describes fine details of the writers’ society at the time, while Gulliver’s Travels and Looking Backward take us into alternative realms. The rise of fantasy and science-fiction literature has led readers to demand to know the history, lore, and furnishings of the imaginary places they visit. The Lord of the Rings saga, part of what Tolkien called his legendarium, is the obvious prototype, but the tendency to fill every niche of imaginary worlds is there in the Star Wars and Marvel universes too.

Once fans have become accustomed to raking every frame for clues about the plumbing system of the Millennium Falcon, they are going to expect an equal density in ambitious works in other genres. But not all films, or even all genres. I suspect that we won’t get the equivalent of Room 237 for My Fair Lady or Dinner at Eight. Combined with the intrinsic fascination of The Shining, Kubrick’s well-publicized concern for detail in the futuristic 2001 and A Clockwork Orange leads us to expect that a film centered on the enclosed world of the Overlook would yield bounty when scrutinized.

Finally, I should note that the seeming capriciousness of the Room 237 readers has a counterpart in one strain of academic interpretation. Borrowing from both Surrealism and a post-Structuralist concern for a “free play of the signifier,” Tom Conley and Robert B. Ray have practiced a criticism that yields results strikingly similar to the work of Ascher’s interviewees. Ray cultivates free association, as when he puns on characters’ names, and Conley has been known to find, as one Room 237 critic does, significant images in cloud formations.

The only major difference is that these academics typically discount an appeal to the filmmakers’ intentions: that move would inhibit the critic’s free-ranging imagination. Once in a while, the Room 237 critics follow suit on this front. They withdraw from attempts to anchor their readings in Kubrick’s life, thought, and personality. One who appealed to intentions early in the film has abandoned them by the end, and another frankly admits: “One can always argue that Kubrick had only some or even none of these [interpretations] in mind, but we all know from postmodern film criticism that author intent is only part of the story of any work of art.”

One of Ascher’s most engrossing final sequences shows John Fell Ryan’s effort to run The Shining forward and backward at the same time, superimposing them to create startling new images like the one that surmounts today’s entry. Folding the film over onto itself is in the spirit of Conley and Ray’s work, I think. The gesture hearkens back to that “irrational enlargement” of films that the Surrealists sought when they dropped in on the middle of one movie, stayed a little while, and then hurried out to slip into another. (They would have loved multiplexes.) Again, the apparently far-fetched meaning-making strategies of our amateur critics turn out to have some kin in the academic establishment and in the history of artistic culture.

I’ve made Room 237 more solemn than it is. It’s a pleasurable and provocative piece of work. It too would be worth interpreting, but I haven’t tried that here. I’ve used it as a kind of AV demonstration. It handily illustrates how interpreting a movie involves certain informal reasoning routines shared by “amateur” and “professional” critics. The differences between the two camps depend largely on what cues the critic fastens on in the film, what associational patterns the critic builds up, and how strongly the critic subscribes to the professional constraints on inferences.

Whether the cues, the patterns, and the inferences based on them seem plausible depends on what particular critical institutions have deemed worthwhile. Claims that won’t fly in mainstream or specialized cinephile publications can flourish in fandom. The purposes and commitments of these institutions may sometimes overlap, but we shouldn’t expect them to.

My account of these critics’ interpretations is drawn wholly from Ascher’s film. All of the interviewees have published more detailed arguments for their views. Bill Blakemore’s thesis about the film’s portrayal of Amerindian genocide is here. Go here for Juli Kearns’ writings on various aspects of Kubrick’s film. Jay Weidner’s thoughts are here. Geoffrey Cocks’ thesis is laid out in his book The Wolf at the Door: Stanley Kubrick, History, and the Holocaust (2004). Jay Fell Ryan discusses and updates his observations in this tumblr site. See also Ryan’s reflections after seeing Room 237.

There seems little doubt that musical texts featuring a verbal text or carrying a program that the composer has sanctioned (like Tyl Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks) can be interpreted in the manner of a novel or painting. Even non-programmatic works without texts have been subjected to interpretation. A still controversial example is Ian MacDonald’s 1990 The New Shostakovich, which launches detailed interpretations of hidden meanings in the composer’s work. For critiques, see Richard Taruskin’s articles in Shostakovich in Context, ed. Rosamund Bartlett, and Shostakovich Studies, ed. David Fanning.

The standard book on secret codes in the Bard is William F. Friedman and Elizabeth S. Friedman, The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. On Saussure’s search for Latin epigrams, see Jean Starobinski, Words upon Words, trans. Olivia Emmet and “The Two Saussures,” Semiotexte 1, 2 (Fall 1974).

James Naremore’s wide-ranging interpretation of The Shining is in On Kubrick. Dennis Bingham provides a detailed history of journalistic and academic interpretations of Kubrick’s film in “The Displaced Auteur: A Reception History of The Shining,” in Perspectives on Stanley Kubrick, ed. Mario Falsetto, 284-306.

Shane Carruth explains that the puzzle aspect of Primer involves only making chronological sense of the plot, which avoids redundancy to an unusual degree.

It’s just that the way the narrative is constructed, I can see how when the story asks you to pull the threads together that’s probably going to happen where threads are pulled together wrong. I definitely didn’t set up this narrative to be open to interpretation. I mean, except for a few things. For the most part, the information is in there to have a very concrete answer as to what is happening in the narrative.

Some critics have worried that Ascher’s film gives viewers an impoverished view of what film criticism is. See for instance Girish Shambu’s comments here. For my part, I doubt that viewers come away believing that the views of these interviewees are typical of criticism as practiced in the mainstream. Nor do I see why Ascher’s movie needs the bigger dose of Theory that Girish prescribes. For my take on Theory (as opposed to theories and theorizing), see the book I edited with Noël Carroll, Post-Theory:Reconstructing Film Studies.

There’s another issue. Like Girish, Jonathan Rosenbaum reprimands the 237 critics for turning The Shining into a puzzle movie.

One way of removing the threat and challenge of art is reducing it to a form of problem-solving that believes in single, Eureka-style solutions. If works of art are perceived as safes to be cracked or as locks that open only to skeleton keys, their expressive powers are virtually limited to banal pronouncements of overt or covert meanings.

I’ve already proposed that a problem-solving approach need not reduce the artwork to a bloodless abstraction. (By the way, I don’t see puzzle-solving and problem-solving as quite the same; I’d say that a puzzle is a particular kind of problem.) But perhaps we should read Jonathan’s first sentence as objecting only to problem-solving approaches that posit “single, Eureka-style solutions.” That would rescue Eliot and Joyce, perhaps, although realizing that Ulysses is a remapping of The Odyssey is something close to a Big Solution to the novel.

In any case, it’s not clear that the 237ers are absolute in their arguments, at least not all the time. The last section of the film chronicles them backing away from their own machinery, confessing that there are dimensions to the film that they haven’t yet grasped, acknowledging that it remains elusive, mysterious, confusing, and, as Dante or a modern theorist might say, polysemous. Moreover, it seems clear that these critics all acknowledge the “expressive powers” of The Shining. They all testify to having been deeply shaken by it; that’s what fuels their urge to probe it. They just claim, like many critics, that the film’s significance extends beyond the visceral and emotional arousal it creates.

On richly realized worlds: J. R. R. Tolkien chose the Latin term legendarium to characterize the entire body of his writings set on the fictional planet Arda, (primarily on the continent of Middle-earth) and the universe in which it exists. The legendarium includes works published during his lifetime, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, as well as posthumous publications edited by his son Christopher, The Silmarillion, “The Quest of Erebor,” and The Children of Hurin. Not strictly speaking part of the legendarium but closely related to it are the numerous drafts published as Unfinished Tales and the twelve-volume “The History of Middle-earth” series, as well as previously unpublished drawings and maps collected by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull in J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator and The Art of The Hobbit. (Kristin wrote this paragraph, as you can probably tell.)

For samples of the post-Structuralist interpretative modes I mention, see Robert B. Ray, The Avant-Garde Finds Andy Hardy, and Tom Conley, Film Hieroglyphs.

In another entry I suggest that interpretation is only one critical activity we might pursue. On contemporary Hollywood cinema’s penchant for puzzle films and richly realized worlds, see my book The Way Hollywood Tells It. In Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema I try to show that just as we can analyze the conventions of a genre or mode of filmmaking, we can analyze the conventions of film talk. It’s one thing that I think a poetics of cinema brings to the table: an effort to disclose what principles shape a critical argument. As for my own tastes, I value consistency, coherence, constrained ascriptions of intention, and historical plausibility in interpretations. But in my own research, I favor analyzing films’ functional dynamics over hunting down hidden meanings.

P.S. 7 April: Thanks to David Kilmer for a corrected quotation!

The Simpsons: Tree House of Horror V: The Shinning (1994).

Donald Richie

Donald Richie and students. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

DB here:

He died last week, aged 88.

What was his life about? The public dimensions involved, of course, his status as unofficial spokesman, principal gaijin, the gatekeeper and guide to anyone interested in Japan. He hosted grad students as genially as he played tour guide to Truman Capote and Susan Sontag and Jim Jarmusch. I don’t know of any other situation in which an American (from Lima, Ohio, no less) became the spokesperson for a foreign culture. From the 1950s into the 2010s, in a stream of writings and lectures, he interpreted how the Japanese lived, worked, thought, and created. Although he wrote about everything from landscape to tattoos, he became best known as the supreme expert on Japanese cinema. His particular love was the postwar “Golden Age” of the late 1940s through the early 1960s.

Tokyo/Hibiya crossing; Dai-Ichi Building, 1947.

Japan was still terra incognita to Westerners when he came there in 1947. When the outer world demanded to understand this very strange place that had fought so tenaciously against America, there arose a generation of interpreters. Of that cadre, though, he stands out as the man you can’t quite place.

The oldest of the group was Edwin Reischauer, who worked largely in international policy. A somewhat younger man, Donald Keene, became the dean of Japanese literary studies. Keene has provided translations and magisterial overviews of the Japanese novel, drama, and poetry. An almost exact contemporary of Keene’s is Edward Seidensticker, who has been a renowned translator and cultural historian.

Only a little younger was our author, who came to Japan in the Navy and soon became a prolific writer. Yet his work didn’t fit the mold of the other American experts on Japan. He was neither a traditional scholar (he read little Japanese, though he spoke it fluently) nor a pure journalist (he refused to be tied to topicality). He remained resolutely in-between. What academic would have the brass to sum up “The Japanese Way of Seeing” in a seven-page essay? Yet what journalist would write subtle critical monographs on Ozu and Kurosawa?

In my copy of Partial Views: Essays on Contemporary Japan, he wrote: “For David, from Donald, particularly pp. 157-205.” On those pages you find his “Notes for a Study on Shohei Imamura.” It’s a fertile survey of recurring themes and techniques in Imamura’s films. In the hands of a professor it could certainly become a tightly argued book. Was his inscription telling me that, when he wanted to, he could execute criticism with an academic accent? If so, it was unnecessary. I didn’t need convincing. I think he could have done whatever he wanted.

What he wanted, I think, was to join the tradition of European belles lettres. He earned his living by writing, and doubtless his championship typing skills steered him toward the quick turnover of daily deadlines. More deeply, I think, he found the shorter piece suited his flair for precise evocation. Even in his books, his approach is essayistic, faceted. His tone—thoughtful but not severe, conversational, projecting wide knowledge and good sense and humane modesty—won the reader by its quiet conviction that the subject was important. This essay wouldn’t be the last word; indeed, he would likely return to the subject years later, testing out new ideas. Much of his output consists of occasion-based pieces, and any of these might be recast, cut, or expanded. A craftsman knows how to recycle scraps and spruce up old projects.

This commitment to fluent reflection on daily changes, along with a quality of seeing everything around him afresh, put him in the tradition of the Continental “man of letters.” He was an aesthete, a moralist, and a bit of a dandy. His natty clothes were like his literary style, crisp and elegant but not flamboyant.

His preferred mode was description. He was convinced that whereas Westerners struggle to probe the depths, “The Japanese realize that the only reality is surface reality.” During a visit to Madison, he was delighted to find a translation of the Goncourt brothers’ journals. I couldn’t help thinking that he took them as a model of the urbane curiosity and pellucid prose he cultivated.

Above all he was interested in people. He was an excellent observer but also a well-tempered listener. He chatted with barbers, students, masseuses, neighbor ladies, potters, delivery boys, executives, and celebrities. He listened to their complaints, their dreams, and their reports on the texture of their lives. Sometimes they quarreled with him or disappointed him. But each one gave him a glimpse of the wavering mirage that was Japan, or at least his Japan.

Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952).

His writing skills worked on a big canvas in The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (1959). He wrote the text while his collaborator Joseph Anderson, who read Japanese, provided the research. The book came at just the right moment, when Americans were starting to appreciate the power of this nation’s cinema. To this day, despite many specialized studies of directors, periods, and genres, it remains the standard overview of one of the great national film traditions.

Just as important, for me at least, was The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968). The first edition, a magnificent buff volume with razor-sharp illustrations and double-column text, is a triumph of book design, as solid and imposing as the films it canvasses. Along with Robin Wood’s works on Hitchcock and Hawks, it showed that cinema could be studied with intellectual seriousness. To the auteurist’s search for the guiding themes of a director’s vision, the Kurosawa book brought a sharp eye for technique and a direct access to the artist himself. (Our author’s first visit to a movie set was to Drunken Angel.) And it proved that a great film could sustain shot-by-shot scrutiny.

Turn to any chapter and you will see a probing intelligence. For Ikiru, we get a detailed layout of image/ sound relations in the nighttown sequence, bracketed by Watanabe’s funeral. The analysis carries us to this conclusion:

He has become much more than simply dead. Just as, dying, he learns to live; so, dead, he becomes more alive for others than he ever was before.

The Kurosawa book remains an exceptional achievement in sympathetic imagination. The critic is so finely in tune with the creator’s sensibility that each chapter illuminates and amplifies the dynamics of the film. There are other ways of understanding Kurosawa, but this book will remain the compass that orients us to this essential director’s career.

Floating Weeds (Ozu, 1959).

There were other books, of course. Among the best is the rare 1961 Japanese Movies, published by the Japan Travel Bureau. It is a compact survey of the major directors working in the postwar era. You sense that its intense aesthetic appreciation of particular films arises from portions cut from The Japanese Film. Here the critic is working at full stretch, and his thoughts on Naruse, Mizoguchi, and others are still worth reading. In its fifteen pages on Ozu, then unknown in the West, lie the seeds of his book on the director.

We have him to thank for our awareness of Ozu. He persuaded the reluctant Shochiku company to release the films in Europe and the US. His ten years of effort were crowned by the release of several Ozu films in New York in 1971-1972. At that point, largely as a result of accidental access, Tokyo Story emerged as the director’s official masterpiece. Soon afterward there appeared Ozu: His Life and Films (1974), another monograph informed by personal acquaintance with the director.

The Kurosawa book dealt in depth with each film, but this took a more horizontal and modular approach, tracing a skein of similarities across Ozu’s work. As one would expect, the emphasis falls on the postwar films, which were more easily available and which the author saw as they were released. (“Revisionist” takes on Ozu, and Japanese cinema as a whole, would soon return to the 1920s and 1930s and find there an earlier Golden Age.) The chapter layout tends to assume that Ozu films are more uniform than they are, but for its attention to themes and script construction in particular Ozu is indispensable. The author’s love for the films shines through every page.

It’s sometimes said that he brought Japanese cinema to the west, but apart from his championing of Ozu, this is inexact. Rashomon opened in New York in 1951, and Gate of Hell won an Academy Award in 1955. Daiei and Toho studios exported several films to Europe and America, while distributor Thomas Brandon sought to bring less-known Kurosawas to the US. The Japanese Film arrived at a propitious moment in 1959, when it could capitalize on the wider circulation of titles. Not until the 1970s was America to see a resurgence of interest in Japanese cinema, thanks to the Ozu releases, the Ozu book,the circulating programs sponsored by the Japan Film Library Council, and the efforts of Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films.

Still, our author did something quite important. By talking about Japanese cinema in terms amenable to Western tastes, he integrated it into our film culture. Kurosawa as a robust humanist; Ozu as the serene contemplator of life’s transience: these became familiar figures thanks to his eloquent critical rhetoric. At the same time he retained a sense of their uniqueness, insisting in particular on the irreducible Japaneseness of Ozu’s aesthetic.

Although his major books remained essential for film lovers and film courses, it’s fair to say that he got a second wind in recent decades. He won a wide and keen following with his commentaries and liner essays for Criterion DVD releases of Japanese classics. The outpouring of grief after his death comes in large part from viewers who knew him best as a warm, calm voice talking through scenes of Tokyo Story or When a Woman Ascends the Stair or, surprisingly, Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar. He adjusted well to the new world of video. He treated it as a new conduit for his commitment to civilized discussion.

Five Filosophical Fables (Richie, 1967).

So much for the public man, writer and speaker and animator of film culture. Another side of him was an intense erotic interest. On your first meeting, he made sure you knew what he found appealing. In the Journals, cruising and pickups blend with a swarm of local details of landscape and custom, although consummations are elided.

I had noticed that his suteteko, being thick cotton, are still damp from the swim, and so I suggest he take them off and hang them on a branch to dry. He does so.

*

Later, in the afternoon, I take a train around the coast. . . .

The juxtapositions between moments of artistic ecstasy and sexual passions give the journals a collage-like snap.

[Hiteki] got into all this ten years or so ago. Has no particular feeling for it but it is now all he knows. . . . Does everything but only, I feel because he does not know what else to do. It apparently means little. Small excitement. . . It represents, I guess, something better than nothing.

6 October 1990. Haydn quartets—the delicious Opus 50. They are made up only of themselves.

The diaries we have are very polished products, the results of much rewriting, and stretches are calculated to render the guilt-free sexiness that the wanderer finds all around him. Consider the finesse of this passage about a visit to Aoshima island:

Later we shop in the empty tourist arcades and buy some beautiful and indecent objects—cups you turn over to discover a coupled couple, an articulated vagina disguised as a shell, and a sake cup with a mushroom-shaped penis attached. One is to suck the sake from the mushroom head.

Some readers expect the Journals to be among the author’s most lasting work. They’re valuable as chronicles of the daily life he observed with sympathetic but dispassionate acuity, but they also record the mind and feelings of a man of Wildean sensitivity wandering among dazzling surfaces that kept his senses, and his libido, ever on the alert.

The surfaces might be rough. The journals record his enjoyment of living near Ueno Park, where the homeless and the prostitutes gather at night. He strolls through them, meeting the occasional cop and seeking, as he puts it, someone who can typify Japan in all its contradictions.

Beautiful and indecent: You can find this mixture in some of the experimental films he made too. The most inoffensive of these, Wargames (1962), was circulated among American film societies during the 1960s, but others are more audacious. In the allegorical satire Five Filosophical Fables (1967) a young man abandons a snooty party, strips to the buff, and strolls smiling through Tokyo streets, past the sea, and into the countryside. Cybele (1968), a documentary of an avant-garde theatre performance, presents an orgiastic rite of sex, degradation, and bloody sacrifice.

Roppongi Hills, Christmas 2010.

He was assailed by bouts of illness across two decades, but he seems never to have lost his buoyancy and spiky wit. He was especially mordant on the New Japan. He notes that the thrusting high-rise apartments of the 1980s bubble offer more for Godzilla to whack. “Originally [he] had to content himself with a mere Diet building.” Manga and the Sony Walkman were very much alike, he maintained. Each offered not visual or aural stimulation but a convenient way to shut oneself off from the ugliness of a money-grubbing society: solitary withdrawal amounted to a critique of contemporary life. With mock pathos he told of a salaryman so preoccupied with talking on his cellphone that a passing subway train snagged him and carried him off, the handset dropped squawking to the platform.

The humor could be self-deprecating. One of our conversations:

DB: I liked The Inland Sea.

DR: I traveled for three months and wrote it in three weeks.

DB: And I read it in three hours.

DR: You took too long.

When asked if he loved Japan, he replied, “That’s complicated . . . I love Tokyo.” Yet by the end of his life, his city had become alien to him. His Japan Journals begin by sketching the vibrant colors of a blasted landscape returning to life.

Winter 1947. Tokyo lies deep under a bank of clouds which move slowly out to sea as the sun climbs higher. Between the moving clouds are sections of the city: the raw gray of whole burned blocks spotted with the yellow of new-cut wood and the shining tile of recent roofs, the reds and browns of sections unburned, the dusty green of barely damaged parks, and the shallow blue of ornamental lakes. In the middle is the palace, moated and rectangular, gray outlined with green, the city stretching to the horizons all around it.

The final entry in the journals is dated nearly sixty years later and records a 2004 trip to his old neighborhood. Tansumachi of 1947 had become the fashionable Roppongi Hills district, “the new Japan—gargantuan, expensive, and wasteful.” A Louise Bourgeois statue looms over the pavement like a tarantula. He recalls the street once named Dragon’s Way and the friend’s house that used to stand at that corner. He knows that his nostalgia must seem tiresome and he acknowledges that rapid change is itself a Japanese tradition, a sort of high-tech version of the Floating World. Yet he cannot resist denouncing the Disneyland that the old place has become. He finds no arresting color or light in this world.

In just a number of years every place will look like it, and this kind of economic expediency will be the rule, as will those cute nods in the direction of retro and trad, that comedy team of contemporary design. Here, under the spider, I look into the future which is already here.

He was well aware of living in-between. Today we might say that he was perpetually “other,” too aesthetically sensitive for a mercantile society, too protective of tradition in a period of lightning change, too gay for straitlaced America, too eccentric and independent-minded for assimilation into his adopted nation. Painful as these tensions must have been, he proudly accepted being fundamentally out of place. At the end of one essay he claims his motto to be that of Hugo of Saint Victor:

The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land.

Extracts from Richie’s writings come from The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968 and later editions), A Lateral View (1992), and The Japan Journals, ed. Leza Lowitz (2005). Richie’s films are available on DVD as A Donald Richie Film Anthology from Image Forum Video. See also The Donald Richie Reader (2001), ed. Arturo Silva, for a varied collection of pieces, including articles on how he came to write about film, and his lively tour Tokyo: A View of the City (1999), with photos by Joel Sackett. The photo of Tokyo/ Hibiya crossing comes from the Journals, the shot of Roppongi Hills from Tokyofashion.com.

For a provocative review of The Japan Journals, see Richard Lloyd Parry’s “Smilingly Excluded.” Kim Hendrickson, who produced Richie’s DVD commentaries, provides a tribute on the Criterion site. A list of his commentaries and liner notes is on this page.

For more on how Japanese films came into the United States, see Chapter 6 of Tino Balio, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973.

Thanks to Tony Rayns for conversations and assistance.

Elsewhere on this site are other Richie-related entries, particularly here and here.

P.S. 25 February: Karen Severns has set up a Donald Richie tribute page here.

Donald Richie at the grave of Ozu. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

How to watch an art movie, reel 1

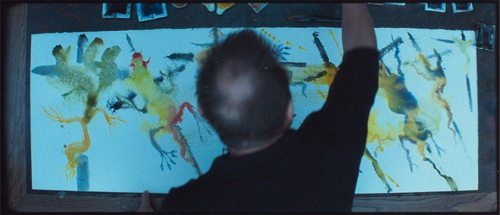

Sueño y silencio (2012). Shot 1.

DB here:

We all know that Hollywood films and their counterparts elsewhere obey certain conventions of style and story. (I say conventions to put it neutrally. Some will call them formulas, some will call them clichés.) Against that tradition some critics and film lovers posit what’s been called “festival cinema” or “art cinema,” a tradition that favors individual expression and more unusual storytelling. But can we say that this tradition also has its conventions?

I think so. Let me take an example that you’ve probably not (yet) seen. Jaime Rosales’ Sueño y silencio premiered in the Directors Fortnight at Cannes this year, went into distribution in Spain recently, and will probably be making the festival rounds. I think it’s a good film, but my appraisal is beside my point today. I want to use the film as a sort of “tutor-text,” a handy way of talking about how such movies engage us in ways different from more mainstream films.

Paranorms

Central to my claim is that such films cultivate intrinsic norms, storytelling methods that are set up, almost like rules of a game, for the specific film. In a way, every film does this. I once wrote that “every film trains its spectator”–an idea that Jim Emerson put more pungently as “Any good movie–heck, even the occasional bad one–teaches you how to watch it.” Up to a point, we figure out the film’s characteristic stylistic and narrative strategies as it unrolls.

Of course most films’ intrinsic norms match what we can call extrinsic norms–those codified by the tradition. Hollywood films frequently simply follow the conventions of genre, structure, style, and theme that have flourished for a long time. What the art film does, I think, is what ambitious Hollywood films try to do: It tries to freshen up its intrinsic norms. But it does this according to broader principles of the art-film tradition. In other words, an individual device might seem strange, even unique to this or that movie, but the function it fulfills is familiar to us from our knowledge of the tradition’s conventions. We figure out the device because we assume it has a familiar function.

Take an example. How does the film indicate that certain images are flashbacks? Classical Hollywood films provided clear markers: Dissolves as transitions, wobbly music, voice-over remarks indicating that a character was recalling the past. But 1960s art films found other devices–slow-motion, shifts to black-and-white or a different palette, cuts to images that would have been out of place in a continuous scene. Viewers who understood the concept of flashback could infer that in this film, flashbacks were signaled through an unusual intrinsic norm. Fairly soon, of course, these devices were widely copied and became extrinsic norms, to the point that Hollywood films picked them up.

I’ve tried to make this entry a primer in art-cinema comprehension strategies. Many of this site’s readers have had a lot of practice in watching films like Sueño y silencio, so in a way what I say won’t come as a surprise. Yet many skilled viewers know the conventions only tacitly. Critics are well-versed in the tradition, but they typically talk only about the film at hand and don’t examine how it connects with more general principles of storytelling. Noting these guidelines, then, helps us understand criticism as well as movies; we can gauge critics’ reactions more exactly when we realize they’re responding to particular conventions.

Since Sueño y silencio has had such limited exposure, I’ll dwell only on the film’s first twenty minutes, its first reel. If you don’t want any spoilage at all, stop reading right now. But actually, my commentary tells you less about the film’s plot twists than the early reviews. I’m just trying to illuminate how such films work and, of course, entice you to see the film if it becomes available to you.

Fifteen shots

When we go to a movie we usually know a good deal about it. For now, though, let’s pretend you haven’t been privy to any information about what you’re going to see in Sueño y silencio. You just take it as it comes. But of course you’re exercising your eyes, ears, and mind all the while.

First you see a water-color painting being finished, in fast motion, by an unidentified painter (see the still at top). The image is pretty hard to determine. What seems to take shape is an image of a vaguely simian creature on the left, some animals in the middle, and a humanoid slung on what looks like a spit. What can this image have to do with what follows? Is the painter our protagonist, and will we learn about his creative endeavors? No. The shot functions as a kind of narrational mystery: We ask not only what it signifies, but why we’re being shown it.

This is as good a way as any of formulating an initial guideline for the hardcore art movie: How the story is presented is as important as what is presented. For instance, is this image offering a cluster of motifs that will be important in the film? When the film is over, we might be able to find out something about the painting or the painter, and we might find some connections to the plot.

So a second guideline: Often we’ll have to go outside the film to understand its story. This contrasts with most mainstream movies, which don’t make reference to recondite things like Spanish abstract painters. As it turns out, the painting refers to Abraham’s pious willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac to God, but it treats the tale in a disturbingly primal way.

Now the story proper seems to be starting. We watch a woman putting on eye make-up, seen through a slit in a door. There’s no dialogue, and the camera waits patiently; the shot lasts nearly a minute. This is the first signal that the film will be observing everyday routine, in more or less real time, from a stationary standpoint. The intrinsic norm that shapes nearly all the film–one fixed shot per scene–is being put into place. This stylistic choice isn’t unique to this film, but it is characteristic of art cinema. When there aren’t dramatic goings-on, as with Paranormal Activity‘s locked-down surveillance camera, the static shot usually asks us to adjust our expectations to a slowly unfolding exposition.

Why start with this woman (whom we’ll learn is called Yolanda)? I think it’s because, as the film goes on, she will be the focus of most of our attention, particularly once the drama starts. In a way, the film is following a very common extrinsic norm: Identify your protagonist early.