Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

A legendary film returns from the realm of the lost

Kristin here-

Nearly two years ago, when Flicker Alley released its wonderful collection of French films made by the Russian-emigré production company Albatros in the 1920s, I wrote, “Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful.” That release arrived yesterday.

For decades, La Maison du mystère remained one of the fabled lost films of the silent era. It was an enormous popular success upon its release in 1923, and critics praised it as well. Even Louis Delluc, who highmindedly promoted cinema as a realistic, restrained art, grudgingly said of it, “La Maison du mystère is a serial. They are a necessity. So be it. This one is intelligent, sober, frank, genuinely human.”

Watching the film today, “sober” seems an odd term. Despite its many arty moments, the film presents a conventionally melodramatic story, with Mosjoukine playing a struggling factory owner betrayed by a villainous “friend” who is secretly in love with his wife. He is falsely accused of murder, presumed dead after an escape from hard labor, and operates under various disguises. Blackmail, flashy escapes, a suicide pact, and flagrant coincidences all play roles. Yet in contrast to the fantastical ones of Louis Feuillade from the 1910s, the ones we are most familiar with today, Le Maison du mystère paid more attention to characterization and moved at a less breakneck pace. (Feuillade had moved into this sort of dialogue-centered melodrama himself in the 1920s, as in Les Deux Gamines, 1921, but these films are rarely watched today.)

With Alexandre Volkoff directing the script he and Mosjoukine adapted from a popular novel, filming began in the summer of 1921. At the beginning of 1922, Mosjoukine contracted typhoid fever and was out of commission for six months. Shooting was completed in the summer of 1922, and the film was released in ten weekly episodes starting in March of 1923. Ultimately, like so many silent films, it disappeared.

Severely abridged feature-length versions existed in some places. An 18-reel print discovered in the Iranian archive was destroyed in a fire before it could be sent to France for restoration. Luckily, the original negative turned up at the Cinémathèque française, having been donated in the collection of Alexandre Kamenka, the producer who took over Joseph Ermolieff’s company in 1922 and turned it into Films Albatros. After restoration, the film was shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in 2002–well before we began our annual visits to that festival in Bologna. It was presented again at the Museum of Modern Art in 2003.

The Flicker Alley release runs 383 minutes and seems to be essentially complete, although the intertitles apparently are replacements. Unlike so many restorations derived from worn release prints, this one is visually gorgeous. It’s mostly in black and white, though it has appropriate tinting for fire and night scenes. Neil Brand provides an excellent piano score.

The old and the new

Like so many of the major French films of the 1920s, especially the Impressionist ones, La Maison du mystére combines a sentimental, old-fashioned story with unconventional stylistic devices: unusual pictorial motifs, beautiful cinematography and design, and imaginative staging. It is probably this visual interest that led to the film’s original acceptance by reviewers and to its enthusiastic reception by modern historians and silent-film buffs.

One visual motif that begins early on is silhouettes. The opening involves Mosjoukine’s character, Julien, still a bumptious, naive young man, courting Régine, the daughter of a wealthy couple who live near his chateau (the “maison” of the title). Despite his shyness, they manage to become engaged and walk joyfully through the woods together.

The entire wedding scene is then compressed into a series of shots done against bright white backgrounds render the actors and settings in near-black silhouettes (above). The result looks like a live-action version of a Lotte Reiniger cut-out animated film.

As I discussed in my entry on the Albatros DVDs, the settings in the studio’s films tended to be impressive as well. Here much of the interest is created by actual locales. David speculated that the whole film was conceived around the ruined fortress or castle where several scenes take place. That’s not likely, but the filmmakers used the ruins well. Rudeberg, a woodcutter whose penchant for amateur photography leads him to photograph the murder of which Julien is falsely accused and convicted, hides the prints in this castle. Rather than turning them over to the authorities, he is using them to blackmail the real murderer, the factory manager Corradin. Corradin twice follows him to the castle, leading to dramatic compositions of the two men in different parts of the frame. In the image at the top, Corradin slinks along the row of arched doorways at the bottom, while Rudeberg is visible moving through a higher archway at left center.

Alexander Lochakoff, the main designer for Ermolieff and then Albatros, was somewhat restricted by the story. He needed to provide realistic interiors for an antique-filled chateau rather than the modern apartments in which some of the other Albatros films take place. Still, he managed some characteristic designs, such as the prison corridor at the bottom of this entry, a location seen only in one brief shot.

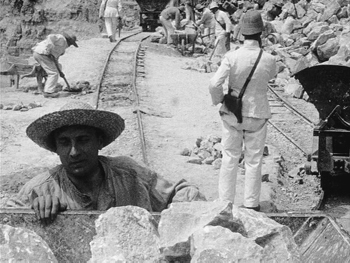

There are some brilliant moments of staging in depth. After Julien is sentenced to twenty years of hard labor, his new situation is introduced via a tracking shot with the camera atop a cartload of stone which he is pushing. Gradually the laborers breaking stone and the guards overseeing them are revealed (below left). In another shot in the ruins where Corradin is tailing Rudeberg, he is glimpsed in the background (below right).

In a scene late in the film, Julien plans to flee with Régine and their daughter Christiane. He is dressed as their chauffeur, but Corradin shows up and spots the car. Julien hides and watches him from behind a tree in the foreground.

We then see the two women approaching, framed through the back window of the car and watched by Corradin, in the foreground. He ducks down and pretends to fiddle with the car’s engine to prevent their realizing who he is as they draw near.

I could go on illustrating such stylistic flourishes, but I leave it to you to find them for yourself. There’s a very early example of a montage sequence to compress the passing of World War I into a series of titles, from 1914 to 1919, superimposed over stock footage of combat, and a marvelously choreographed high-angle scene in a forest as a troop of policemen pop out of nowhere to surround and arrest Julien.

All serials need stunts

Much of the film consists of conversations and confrontations among the characters, a trait which no doubt led critics to contrast the more action-oriented serials of recent years. Still, there are two sequences where derring-do takes over. After the police arrest Julien, he makes an escape via a rope down the tower and wall of his chateau, a feat accomplished in a single take tilting down to follow his progress.

Later, in an episode entitled “The Human Bridge,” Julien and four of his fellow prisoners escape from their guards while working on a railroad track. This lengthy sequence involves first the commandeering of a passing train and then a chase over an area of rocky crags. At once point the escapees find the rickety remains of a tall bridge above a river gorge and fling ropes across. The four other prisoners then lie end to end, clinging to the ropes, forming a bridge to allow Julien, who has been wounded during their flight, to cross over. One extreme long shot of the scene shows two of the men’s hats falling off, demonstrating as they drift down to the bottom that there is no trick photography involved. It is certainly as impressive as any of the stunts in Feuillade’s films.

Touches of Impressionism

La Maison du mystère certainly cannot be characterized as an Impressionist film. Yet the movement was beginning to expand in 1921, and there are some moments of subjectivity that draw upon its newly minted conventions. As his trial is drawing to an end, Julien closes his eyes, and the shot goes out of focus. We see a series of quickshots of his surroundings and his family as he seemingly recalls the events of the trial as a montage scene. Finally the same framing of Julien shows him coming into focus.

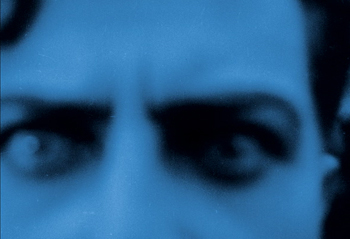

This is a fairly straightforward Impressionist device, but a more daring suggestion of a subjective state occurs much later. Julien’s daughter Christiane and Rudeberg’s son Pascal have fallen in love, and they vow that if they cannot marry each other, they will both commit suicide. When the villainous Corradin forces Christiane to agree to marry him, Pascal sets out to drown himself. His distraught state of mind is conveyed in a single shot as he walks toward the mill pond and hesitates. As he moves into the shot, he is framed in a standard medium close-up. As he hesitates, however, he moves unusually close to the camera and then backs partway out of the frame, as if afraid to continue. Finally he turns and stares into the camera, moving forward out of focus until his dark-shadowed eyes fill the frame. The implication is that he determines to go on with his plan.

(Fans of Evgeni Bauer will recognize Vladimir Strizhevski, the son in the director’s final film, The Revolutionary.)

Star turn

Apart from the imaginative staging, cinematography, and design, La Maison du mystère is full of fine performances. It provides a vehicle for a virtuoso performance by Mosjoukine. He is part Douglas Fairbanks, part Lon Chaney as he leaps energetically about in the early parts of the film and then dons various disguises during his long period as a fugitive. He briefly poses as a clown in a small circus and later returns to work incognito in his own factory as a wounded war veteran with a limp and eye-patch.

Mosjoukine’s fellow actors refuse to be overshadowed by the star, with Hélène Darly as Régine managing somehow to age from a young lady to a mature mother without any apparent change of makeup. Nicolas Koline, best known as Tritan Fleuri in Napoléon vu par Abel Gance, brings something of his usual comic persona to Rudeberg, while also conveying the character’s guilt over choosing to use his photographs for blackmail purposes rather than to reveal Julien’s innocence. Charles Vanel, who had been acting in films since 1910 and would become a major star in the sound era, conveys Corradin’s villainy perhaps too well, making one wonder why any of the other characters ever trusted him.

Flicker Alley, along with the Cinémathèque française, David Shepard, and Lobster Films, have filled in a major gap in film history, and we are indeed doubly grateful.

The quotation from Louis Delluc and information on the production of the film come from the essay, “The Art Film as Serial” by Lenny Borger with David Robinson, included as a booklet in the DVD set.

Impressionist films have been included in some of our “best films” of ninety years ago series. See 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.

EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS and the myth of authenticity

Kristin here:

Back in the early 1990s I got interested in ancient Egypt and particularly the Amarna period. I started reading, attending conferences, giving papers at conferences, and eventually publishing scholarly articles. In 2000 I was invited to join the expedition at Amarna, registering statuary fragments. That work quickly grew into matching pieces, reconstructing a considerable portion of an important statue, researching in museums around the world, and now working on a large book on Amarna royal statuary. (You can read a bit about my work in this page of our website–badly in need of updating.)

So I watched Exodus: Gods and Kings with a somewhat different attitude than that of most other viewers. Now I don’t expect all films set in ancient cultures to be 100% authentic in their design and their depiction of events. Considerations of spectacle and general visual appeal take precedence at times. But Exodus goes a bit over the top. Even a one-time tourist to Egypt who was paying the slightest attention to the guide would spot some laugh-out-loud moments here.

The departure from historical reality here led me to think, as I often do, about the ways in which the makers of fiction films set in ancient Egypt and other early cultures tend to try and lend an air of authenticity by hiring an expert consultant who is listed in the final credits.

Something similar happens in educational documentaries of the type shown on The Learning Channel or The History Channel. There several experts may appear in talking-head segments, and additional scholars will be credited at the end as consultants.

My experience, however, is that in at least some cases, consultants’ advice is ignored, even in the documentaries. Filmmakers tend to do what they think will be most appealing to the viewer, and then credit the consultants anyway, as if they had actually guided the filmmakers throughout. I know this partly because several of my teammates and other Egyptologists have complained that it is not uncommon for their suggestions to be dismissed. I have been filmed a couple of times, though I ended up on the cutting room floor in both cases. My chunks of broken sculpture, which tell me a great deal and in some cases are very unusual and important historically, just aren’t visually interesting enough for the public–or so the assumption is. On one of these occasions I pointed out to the filmmakers that one object was more relevant to the point being made than the one they wanted to use. I was told that the one they wanted to and did use would look more attractive. I’m sure a lot of consultants more expert than I hear the same thing.

Too much history

One has to sympathize with filmmakers tackling a tale set in ancient Egypt. Its history just goes on and on.

The date for the unification of Egypt under a single ruler and the invention of the hieroglyphic writing system that made its centralized administration possible keeps getting pushed back as more discoveries are made. Now it’s at about 3100 BC. Pharaonic Egypt ended in 30 BC with the death of Cleopatra VII Philopator (yes, that Cleopatra) when she committed suicide, reportedly using a poisonous snake. To give a vivid indication of how long pharaonic Egypt lasted, Cleopatra lived distinctly closer in time to us (just over 2000 years) than she did to the building of the Great Pyramids of Giza (about 2600 years earlier). And those pyramids were built about 500 years after that unification I mentioned.

The challenge for filmmakers is that many of the things we think of as most emblematic of ancient Egypt happened far apart in time. The Great Pyramids of Giza were built around 2600. The introduction of horses and chariots was–well, nobody knows exactly, but perhaps some time in the 1640 to 1550 BC range. Yet filmmakers cannot resist the temptation to have people dashing about in chariots as they supervise the building of the Great Pyramids. Howard Hawks’s Land of the Pharaoh does it. Exodus: Gods and Kings does it. It looks good, but in modern terms it would be sort of like William the Conqueror checking his email to see how preparations for his invasion of Britain were going.

Apart from the problem of Egyptian history, Exodus mixes two different genres of story. The Exodus story is a myth based solely on texts, with no archaeological evidence to confirm it. Ancient Egyptian history really happened. That history can be portrayed authentically, while the Exodus story can be portrayed faithfully. There’s a difference. Moreover, even people who believe that the Exodus really happened can’t agree at what point in that history it occurred. Probably the most popular choice for the Pharaoh of the Exodus is Ramses II, and the filmmakers have settled on that. He’s not called “Ramses the Second” in the film, and indeed ancient Egyptians didn’t think of their kings as numbered. Still, the fact that his father is Sety indicates that the Ramses in the movie is the second of the eleven Ramses that sat on the throne of Egypt over the years.

Absolute chronology is impossible to determine for ancient Egypt, but best estimate is that Ramses II reigned from 1290 to 1224 BC. (He lived to be 97.) That’s Nineteenth Dynasty, New Kingdom. The period I study is roughly 1353 to 1335, the reign of Akhenaten, who is Eighteenth Dynasty, New Kingdom, so not all that far apart by Egyptian standards. The late Eighteenth Dynasty and early Nineteenth were the pinnacle of Egyptian power and wealth: perfect for a sword-and-sandal spectacle.

Yet in making Exodus, the filmmakers have not solved the problems I’ve just mentioned. Time and space are oddly warped, and design concerns have trumped authenticity to a considerable degree.

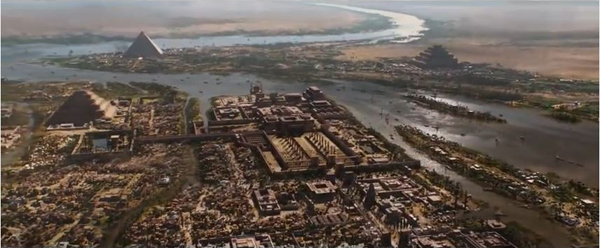

Egypt compressed

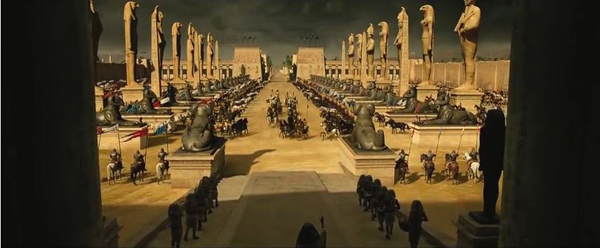

Perhaps the strangest aspect of Exodus: Gods and Kings is how it mashes together not only things from different periods but also localities that are actually many miles apart. The early part of the action is set in Memphis, which was genuinely the administrative capital of Egypt during much of its history. See the image at the top, which gives the best view of the city’s layout. The earliest pyramid ever built, the Step Pyramid of Djoser (constructed somewhere around 2630 BC and probably the one over on the left in the image), is part of the necropolis of Memphis, but it’s up on the high desert, well away from the city, which is down in the cultivated area. And what is that other step pyramid doing on the other side of the river? There was only the one step pyramid, and all the pyramids built as tombs for the pharaoh were on the same side of the river, the west. The pointed pyramid in the distance has been transported from Giza to Memphis. Admittedly, that’s only a distance of about fifteen miles.

But the pyramid is also shown under construction. Ramses II would not have built a pyramid for his own tomb, since long before that point pharaohs had started using rock-cut tombs in what is now known as the Valley of the Kings. That’s where he was interred.

In the film, the palace of Sety and later of Ramses is modeled on the temple of Amun at Karnak, way down in Luxor (about 350 miles away). The massive columns of the hypostyle hall, one of the most familiar tourist sights in the country, were indeed built by Sety and Ramses, but it’s a temple, not a palace. Temples were built largely or entirely of stone in this period, while palaces were mainly built of mudbrick and painted mud plaster. We don’t know nearly as much about palaces as we do about temples, because they tend not to survive very well. Pharaohs tended to travel around, staying in palaces built for specific purposes, rather than to erect one giant one to call home.

The road running out from the palace down which Moses, Ramses, and other leaders of the army depart is lined with criosphinxes, sphinxes with the heads in the form of a ram, the sacred animal of Amun (see bottom). These are copied from the criosphinxes that line the sacred ways leading up to Karnak from the west and south. These criosphinxes didn’t have colossal statues of gods standing in between them, though the filmmakers may have added them to give a hint at the multiple gods of the ancient Egyptians. Given the film’s title, one might expect a little more exposition on the gods of Egypt, to create a contrast with Moses’ monotheistic religion. Instead we get almost nothing relating to gods except entrail-reading, which was not practiced in ancient Egypt.

The choice of Memphis as the main city setting is a dubious one. Sety I founded a new city east of the Delta, and Ramses II built it up into the new main royal residence and capital of the country, Piramesse. I mention this not to be nitpicky. In fact, at the beginning of his reign, as he is in the film, Ramses quite possibly was still primarily residing in Memphis. The point really is that the Bible specifies that the Exodus began with the Israelites leaving “Rameses” (spelled thus in the King James translation, “Exodus” Chapter 12, 37). It’s not absolutely certain that this Rameses is identical with Piramesse, but no other candidate has been discovered, and it seems likely. Piramesse lies well north of the Red Sea and due west from the land bridge from Egypt to the Sinai peninsula. Heading straight for Canaan, the Israelites shouldn’t have had to deal with the Red Sea or any parting thereof to get where they wanted to go. Still, it makes a vivid story.

Piramesse is also quite far from any pyramids or other spectacular, familiar Egyptian structures, and out in the flat lands north of the beginning of the Delta. Plus a lot more people have heard of ancient Memphis than Piramesse, so one can understand the filmmakers’ choice of cities.

Familiar and not so familiar mistakes

Another thing that film designers of stories set in ancient Egypt invariably do is to put many of the male characters and even extras in the striped headcloth called the nemes. That’s the one that forms a sort of triangle on either side of the face. Guards, overseers, officials, all wear the nemes. In this hanging scene, for example, the chap at the far left in the frame below has one, as has the man in the middle ground, just to the right of the scaffolding. So do the men lined up at the back of the scaffold. But the nemes was a royal headdress. Only the king could wear it. The royal uraeus, the rearing protective cobra worn above the forehead, was also confined to the king, and during some periods his wife. We see Moses wearing one when going into battle, which would not have been allowed.

And speaking of this scene, hanging was not a method of execution used in ancient Egypt. In fact, execution as such was fairly rare, but someone who rebelled against the state or the gods might be burned alive or impaled. On the whole,  severe punishments involved loss of property or hard labor, like being sent to the pharaoh’s quarries or mines–likely to be a death sentence in itself.

severe punishments involved loss of property or hard labor, like being sent to the pharaoh’s quarries or mines–likely to be a death sentence in itself.

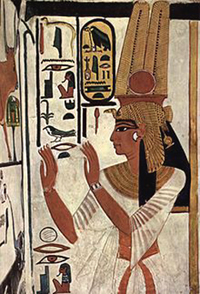

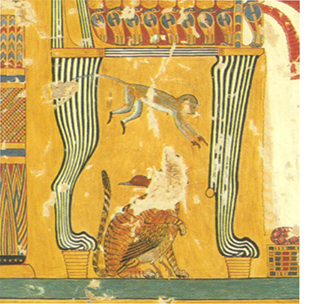

In two or three shots of the palace, we see peacocks wandering around. There were no peacocks in Egypt at this point. I suppose the designers thought that these showy birds would add to the spectacle and the sense of vaguely decadent luxury. There were, however, other options. For example, ancient Egyptian royals and nobility loved monkeys and kept them as pets. They are frequently depicted in reliefs and paintings, mainly in tombs, sitting under their owners’ chairs, though favorite dogs or cats often occupy that spot instead. A particularly lively monkey appears in the image to the left, from the tomb of a prominent Eighteenth Dynasty official, Anen, on the west bank at Luxor. The monkey is leaping under the chair of Queen Tiye, and beneath it is what appears to be a cat embracing a duck in a friendly fashion (left). That seems pretty visually interesting to me.

In the film, Ramses’ army includes cavalry, but ancient Egyptians didn’t ride horses into battle. The troops were either in chariots or on foot. The horses originally introduce d into Egypt were too small to be ridden by someone fully astride their backs. Consequently saddles were unknown in Ramses’ era. The rider had to sit well back on the rump, as Egyptians still do today when they ride donkeys. In the Memphite tomb of Horemheb (last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty or first of the Nineteenth, depending on whom you ask), there’s a rare depiction of a man riding a horse in exactly this fashion (right). He’s probably a groom, taking a horse from one of the chariots visible at the upper right to tend to it elsewhere.

d into Egypt were too small to be ridden by someone fully astride their backs. Consequently saddles were unknown in Ramses’ era. The rider had to sit well back on the rump, as Egyptians still do today when they ride donkeys. In the Memphite tomb of Horemheb (last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty or first of the Nineteenth, depending on whom you ask), there’s a rare depiction of a man riding a horse in exactly this fashion (right). He’s probably a groom, taking a horse from one of the chariots visible at the upper right to tend to it elsewhere.

Exodus: Gods and Kings also dusts off that Hollywood cliché of showing legions of Israelite slaves laboring under the lash to built the Great Pyramids. The main sources of this notion are Herodotus (writing about 2200 years after the event) and the book of Exodus in the Bible (perhaps written close to 3000 years after their construction).

In fact the Great Pyramids were built by paid laborers. Many of these were part of a permanent workforce who lived in a village near the plateau. Others might have been part-timers, such as farmers whose fields were under the inundation for four months out of every year.

The claim in the film is that the Israelites have been enslaved in Egypt for four hundred years. Four hundred years before Ramses II’s reign, Egypt was falling apart, with the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasty pharaohs fighting for control. The country was declining into the Second Intermediate Period, with part of the land controlled by the Hyksos, a foreign group of rulers. There were probably few if any slaves being brought into Egypt at the time, let alone a huge group like the one posited.

Slavery in ancient Egypt is still not fully understood, but clearly it was a more complex and flexible system than the sort of slavery that we think of today. There weren’t all that many slaves in the Old Kingdom when the pyramids were built. The big influx came with the expansion of the empire in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties, when Egypt conquered southward into Nubia and northeastward into the Levant. At that point prisoners of war became the main source of slaves. They would either serve the pharaoh and his institutions or be awarded to the military officers who had served well in combat. Slavery didn’t become the basis of the national economy, ironically, until the Greeks took over.

Slavery took a variety of forms. It could be a punishment for wrongdoers, but it could also be a way of going bankrupt, working off debts by serving the creditor. There is evidence that slaves had legal rights, such as owning property. There are recorded cases, perhaps exceptional, of slaves gaining training in professional skills, including writing. Some could rise to management positions, even supervising freemen in their masters’ estates. In some instances, slaves married or were adopted into the families they served. Slavery covered a wide range of circumstances, but it didn’t extend to the sort of mass oppression portrayed in Exodus: Gods and Kings.

I could go on, but a few more brief examples should suffice. The Great Sphinx, which is located in front of the central pyramid at Giza, is placed out in the desert instead. Colossal statues of Ramses were not built of individual small blocks of stone. Even his collapsed colossus at his mortuary temple, which weighed about 1000 tons when intact, was made of a single giant piece of granite. Huge sphinxes would not be built in the middle of residential areas, let alone slave dwellings, as are the ones we glimpse in the film.

And finally, the golden helmet that Ramses wears into battle is based on a queen’s protective vulture crown. His wife, Nefertari, would have been the one to wear such a crown. The real Nefertari is shown wearing several embellished ones, including this one with large plumes and a sun disk, in her spectacular painted tomb. The vulture’s head acts as a uraeus in this case, though it has rather bizarrely been replaced by a snake on the version given to Ramses.

Don’t get me started on the camels.

Research with a little twist

To be fair, the publicity surrounding Exodus didn’t make a lot of big claims to authenticity. There was some attempt, however, to promote its faithfulness to historical fact. The Hollywood Reporter ran one brief paragraph in a piece on possible Oscar nominees for best production design.

Arthur Max, production designer

Before creating ancient Egypt’s Royal Palace of Memphis, Max took a research trip up the Nile to visit the Luxor Temple and the Temple of Amun [i.e., Karnak]. He also made stops at the British Museum, the Petrie Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Egyptian Museum of Turin. The $150 million production spent 16 weeks building large sets at Pinewood Studios, and CG was used to extend their monumental scale. “Each column is 10 feet in diameter and about 70 feet high,” says Max. “All the furniture is hand-built–there’s not a lot of ancient Egyptian furniture around. All the murals are hand-painted in traditional pigments. They even re-created period sculptures like a 42-foot high head of Ramses the Great.

Some of the other design people, however, freely admitted to a concern with flashiness over authenticity. Variety ran a story on the costumes:

Those who have seen Janty Yates’ work with Ridley Scott in period epics like “Gladiator” and “Kingdom of Heaven” know they can expect a feast for the eyes that’s grounded in research, but also offers what she called “a little twist.” Translation? A bit of extra sheen in a metal breastplate, or, in the case of Scott’s biblical saga, “Exodus: Gods and Kings,” dressing Ramses entirely in gold, or making T-shaped garments for the plebes that look “quite hot,” per Yates.

Another Variety story of the same type is very misleadingly entitled “Making It All Look Real” (in the print edition; the online title is “Artisans on Making ‘Exodus: Gods and Kings’ Look Authentic”). In fact, the piece is about how authenticity was sacrificed to design considerations.

Filmmakers strive for period authenticity–up to a point.

Take Ridley Scott’s “Exodus: Gods and Kings.” Set decorator Celia Bobak said she took certain liberties. For example, tables in ancient Egypt were low to the ground–a look that she felt contemporary audiences might find laughable.

Similarly, cinematographer Dariusz Wolski requested the use of silk fabrics to enhance the film’s warm, golden-color palette, even though linen and wool were more period-specific.

Bobak added that materials used for creating the furniture “were anything but authentic,” but were made to look so by a team of painters who paid attention to surface decoration and detail.

Working with production designer Arthur Max, a frequent Scott collaborator, Bobak researched the period by visiting the Cairo Museum and Egyptian archives in Europe. Once the duo established the look of each set, prop makers, graphic designers and carpenters brought everything to life.

Why modern audiences would laugh at low tables is unclear. I suspect that decision had more to do with staging the scene where Ramses threatens to cut off the hand of Moses’ “sister,” which he is holding down on a table top. That certainly would have looked silly with the characters bending over a low table.

Yes, there was an expert consultant

With this sort of personal research and devil-may-care attitude, combined with the highly selective use of actual historical fact, you might assume that the Exodus project didn’t hire an expert consultant. In fact, they did. They didn’t flaunt their consultant in the credits, though, as such films tend to do. I scanned the credits for the name Alan Lloyd, but I didn’t spot it. It must be there somewhere, since it’s listed on the imdb Full Cast and Crew for the film. There it’s way down at the bottom, under Other Crew:

Dr. Lloyd is listed as “technical advisor (Doctor),” which might convey the impression that he was on the medical team. I don’t know why the filmmakers buried him in this fashion, since Dr. Alan Lloyd is an actual, reputable Egyptologist. He’s currently the president of the Egypt Exploration Society, which has been a major British institution fostering Egyptological work since 1882. He retired from the University of Swansea in 2006, with a substantial record of publication and other scholarly activities. His specialties include Herodotus, the Graeco-Roman period in Egypt, and ancient warfare.

Dr. Lloyd also is a big film fan and admires Ridley Scott, as an interview with him on the writing studio site reveals. There he expresses enthusiasm for the film and the experience of working on it. In particular he speaks of the care taken concerning texts:

One particularly clear indication of this was that they continually came back to me to provide them with copy for Egyptian texts, and this was sometimes hieroglyphs, and this I provided them with, and indeed they used it.

They also, at times, wanted material in hieratic, which was the script that was normally used for letters and documents, and I produced that material for them.

Particularly interestingly, and I don’t know how many people in the world would pick up on this, or even whether it was used, but they wanted text of the Ten Commandments, but not in English.

They wanted it in Hebrew and I gave them the Hebrew text written in the old Hebrew alphabet, not the one that everyone is familiar with. It is the proto-Hebrew alphabet, which is very different.

All the texts in the film flitted by so fast that even an expert couldn’t judge them, but I assume they were accurate. We get one glimpse of Moses writing the Commandments on a tablet, but the view is from opposite him and we see the writing upside down. (By the way, in the Bible, didn’t the Lord himself write these?)

Oddly, toward the end of the production, the filmmakers showed Dr. Lloyd only selected sequences from the film. The same interview continues: “Professor Lloyd has seen footage from the film and says that some of the sequences he watched, including the Battle of Kadesh and the plagues visited on ancient Egypt by an angry God, are ‘brilliantly’ realized.”

To be sure, the long montage sequence of the plagues is probably the best thing in the film. Moreover, given Dr. Lloyd’s expertise in ancient warfare, it seems likely that he was consulted particularly on the battle scene. It’s certainly more authentic than most of the film’s other scenes. Six-spoked chariot wheels, yes. Plumes on the royal horses’ heads, yes. Bows and arrows, yes. The chariots themselves look fairly close to surviving ones from the New Kingdom. My guess is that Dr. Lloyd pointed out that cavalry was not used in that period but was told that showing warriors riding horses (with saddles) was more visually interesting than mere foot soldiers.

Perhaps Dr. Lloyd was not shown the entire film because of all the inaccuracies in the other scenes. Or perhaps I am being too suspicious.

Hollywood remains in an ambiguous position in regard to historical authenticity, especially in spectacular tales set in ancient times. It plays well in the publicity, but when the designers come up with their visions, it’s awfully easy to dismiss it.

A final comment

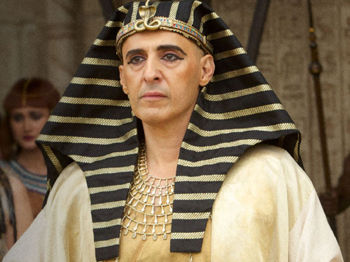

There has been much criticism of the filmmakers for using white males for the lead roles. True, it’s hard to think of Christian Bale and especially Joel Edgerton as an ancient Canaanite or Egyptian. But to give the film some credit, the moment I saw John Turturro as Sety I, my unexpected reaction was, Wow, he looks like a Ramesside pharaoh. Specifically, like Sety I.

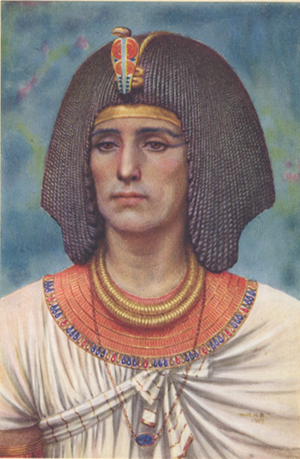

How can we know? For a start, Sety’s mummy happens to be one of the best-preserved that has come down to us. Even so, it’s hard to tell from a mummy what the man looked like, though he obviously had a beaky nose, a long chin, and prominent, high cheekbones. In the early 20th Century, artist Winifred Brunton studied Egyptology alongside her husband. They worked in Egypt, and during that time she painted a set of portraits of the pharaohs and their families, based on paintings, sculptures, and mummies. They’re actually fairly plausible as conceptual paintings. Although they’re not scientific evidence, they’re still held in some regard by Egyptologists–though obviously the depiction of the skin color of the ancients does look too European. Her portrait of Sety I is at the right below. She shows the pharaoh as a younger man, but to me the resemblance is there.

The only source I could turn to for frames from the film was the set of online trailers. I can’t be entirely sure that all of my illustrations are in the final film, since occasionally shots from the trailer get dropped.

The photo of Ramses’ helmet was one of many of his golden costume taken by blogger Jason in Hollywood during the current “23rd Annual Art of Motion Picture Costume Design” exhibition, which takes place in the pre-Oscar period.

For those interested in birds in ancient Egypt, a catalogue of a recent exhibition at the Oriental Institute in Chicago is available as a pdf online for free. No peacocks, but storks, pelicans, hoopoes, geese, and many more, as beautifully rendered in tomb paintings and other ancient artworks.

Anyone visiting Bologna, whether for Il Cinema Ritrovato or any other purpose, can wander over to the Museo Civico Archeologico, just off the Piazza Maggiore, and see the original of the relief of the horse-riding groom and other magnificent scenes from the tomb of Horemheb.

For a good, brief Associated Press summary of evidence against the Great Pyramids being built with slave labor, see here. For a longer but accessible account of the work of Mark Lehner, who has long excavated at Giza and discovered the village of the pyramid workmen, see here.

Winifred Brunton’s portrait of Sety I appears in her Kings and Queens of Ancient Egypt (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1926).

Genre ≠ Generic

The Shape of Night (Nakamuro Noboru, 1964).

DB here:

I didn’t plan it that way, but it turns out that a great many films I saw at this year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival would have to be categorized as genre pictures. Not, admittedly, Shu Kei’s episode of Beautiful 2014, which interweaves flashbacks and erotic reveries in a purely poetic fashion. And not Tsai Ming-liang’s “sequel” to Walker (2012, made for HKIFF), called, whimsically, Journey to the West. Here again, Lee Kang-sheng, robed as a Buddhist monk, steps slowly through landscapes, some so vast or opaque that you must play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game to find him. (You have plenty of time: there are only 14 shots in 53 minutes.)

But there were plenty of other films that counted as genre exercises. Yet they mixed their familiar features with local flavors and fresh treatment, reminding me that conventions can always be quickened by imaginative film artists.

Keeping the peace, in pieces

Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014).

Take, for instance, The Shape of Night, a 1966 street-crime movie from Shochiku, directed by Nakamura Noburo. Nakamura was the subject of a small retrospective at Tokyo’s FilmEx last year, and this item certainly makes one want to see more of his work. A more or less innocent girl falls in love with a yakuza, who forces her to become a prostitute. In abrupt, sometimes very brief flashbacks, she tells her life to a client who wants to rescue her. The film makes characteristically Japanese use of bold widescreen compositions, disjointed close-ups, and mixed voice-overs from her and the men in her life. In retrospect, everything we’ve seen has been seen in other movies, but Nakamura’s handling kept me continually gripped and often surprised.

Or take That Demon Within, a Hong Kong cop film that premiered at the festival’s close. Dante Lam has made several solid urban action pictures, especially Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), Beast Stalker (2008), Fire of Conscience (2010), and The Stool Pigeon (2010). They’re characterized by wild visuals and exceptionally brutal violence, and That Demon Within fits smoothly into his style. The new wrinkle is that a boy traumatized by the sight of police violence himself becomes a cop. He’s then haunted by the image of the cop from his past, while he’s also caught up in a search for a take-no-prisoners robber.

His hallucinations and disorientation are rendered through nearly every damn trick in the book, from upside-down shots and blurry color and focus to voices bouncing around the multichannel mix.

There are dreams, too (seems like almost every new film I saw had a dream sequence), and scenes under hypnosis, and men bursting into flame, and action sequences that are visceral in their shock value. I thought the movie careened out of control pretty early, and its nihilism wasn’t redeemed by an epilogue that assured us that this possessed policeman was, at moments, friendly and helpful. In this case, the storytelling innovations generated some confusion about exactly how the hero’s breakdown infused what was happening around him.

More consistent, largely because it didn’t try for the subjectivity of Lam’s film, was the Chinese cop movie Black Coal, Thin Ice. My friend Mike Walsh of Australia pointed out that the mainland cinema’s bleak realism seems to be starting to blend with traditional genre material. Director Diao Yinan explained, “My aim was not only to investigate a mystery and find out the truth about the people involved, but also to create a true representation of our new reality.” The opening crosscuts the grubby detail of bloody parcels churning through coal conveyors with a couple entwined in a final copulation before breaking off their relationship.

The mystery revolves around body parts that are showing up in coal shipments around one region. After a startling shootout in a hairdressing salon, the case remains unsolved for several years. The surviving detective, a shabby drunk, returns to track down the culprit, but in the meantime he runs into a frosty femme fatale. “He killed,” she says, “every man who loved me.” Needless to say, the detective falls for her too, especially after ice-skating with her. Diao’s film reminds us that you can create a neo-noir in two ways: By taking a mystery and dirtying it up, or taking concrete reality and probing the mysteries lurking in it.

There were even two Westerns. Another mainland movie, No Man’s Land, was unexpectedly savage coming from the director of the super-slick satires Crazy Stone (2006) and Crazy Racer (2009). Now Ning Hao has given us a bleakly farcical, Road-Warrior account of life on the Chinese prairie.

A wealthy lawyer brought out to the wasteland to negotiate a criminal case becomes embroiled in primal passions involving men with very large guns, very large trucks, impassive faces, and almost no sense of humor. It’s a black comedy of escalating payback (involving spitting and pissing), and it exudes sheer masculine nastiness. Completed four years ago, it found release only after extensive reshoots demanded by censors. Yet even in its milder state it remains true to the spirit of Sergio Leone’s jaunty grimness, bleached in umber sand and light.

Itching to see a Kurdish feminist political Western? You’ll find Hiner Saleem’s My Sweet Pepperland welcome. A tough policeman (= sheriff) is dispatched to a remote village in Kurdistan to keep order (= clean up the town). A young teacher (= schoolmarm) leaves her oppressive family to teach there as well. A warlord (= town boss) and his minions (= paid killers) have terrorized the locals, while marauding female guerillas (= outlaws) bring their fight into town.

These time-honored conventions shape a story of stubborn courage taking on complacent viciousness. In key scenes, our sheriff faces down big, hairy, scary killers.

USA frontier conventions, it turns out, work pretty well in a Muslim society too. The Hollywood Western’s continued embodiment of American values transfers easily to the former Iraq. “Our weapons are our honor,” the chief thug says, in a line that resonates through our history right up to now. Yet things we take for granted bring modern change to the wasteland. The sheriff assigns himself to the village in order to escape an arranged marriage, as the woman he finds there has done. She is vilified by both the locals and her male relatives, who would prefer death (hers) to dishonor (theirs). In the process, both he and she become heroic in a righteous, old-fashioned way.

A killer proposes a compromise while sneakily drawing his pistol. The cop shoots him and remarks: “I don’t do compromise.” Neither does My Sweet Pepperland.

Gangs of New York, and elsewhere

The Dreadnaught (1966).

From March to May, the Hong Kong Film Archive has been running a series, “Ways of the Underworld: Hong Kong Gangster Film as Genre.” It’s packed with classics (The Teahouse, To Be No. 1, City on Fire, Infernal Affairs) as well as several rarities (Absolute Monarch, Bald-Headed Betty, Lonely 15). I managed to catch three titles, all previously unknown to me.

The Dreadnaught (1966) has a familiar premise. Two orphan boys indulge in petty theft after the war. One, Chow, is caught but gets adopted by a policeman. He turns out a solid young citizen. Lee, the boy who escapes, grows up to be a triad. When the two re-meet, Lee is attracted to Chow’s stepsister. Some years later, Chow is now a cop and vows to smash Lee’s gang. After a struggle with his conscience, Lee agrees to help.

The film’s main attraction is the shamelessly flashy performance of Patrick Tse Yin. Tse would make his fame in the following year in Lung Kong’s Story of a Discharged Prisoner, famous as a primary source for A Better Tomorrow. With his sidelong smile, his endlessly waving cigarette, and the dark glasses he wears at all times, Tse in The Dreadnaught looks forward to Chow Yun-fat’s charismatic role as Mark in Woo’s masterpiece.

Another icon of the period is Alan Tang Kwong-wing. He played in over 100 films, mostly romances and triad dramas made in Taiwan. Westerners probably know him best as the producer of Wong Kar-wai’s first two features, As Tears Go By and Days of Being Wild. Wong had worked as a screenwriter for Tang. Onscreen, Tang had a suave, polished presence marked by his perfect coiffure; he was known as the Alain Delon of Hong Kong. His company, Wing-Scope, specialized in mob films during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

New York Chinatown (1982) shows Tang as a young hood whose ambitions to dominate the neighborhood are blocked by a rival gang. Eventually the police decide to let the two gangs decimate each other. This leads to an enjoyable, all-out showdown involving surprisingly heavy armaments. Shot quickly on location (passersby sometimes glance into the lens), the movie gives a rawer sense of street life than you get from most Hollywood films. There’s also a scene in which Tang, apparently attending Columbia part time, corrects a history professor lecturing on Western imperialism in China. Although the film circulates on cheap DVD in 1.33 format, it’s a widescreen production, and it was a pleasure to watch a fine 35mm print at the Archive.

The biggest revelation of the series for me was Tradition (1955), a Mandarin release. This is considered one of the earliest pure gangster films in local cinema. It’s a fascinating plot about a boy raised by a triad kingpin in the 1930s. When the godfather dies, the young Xiang is given power over the gang and the master’s household. Trying to be faithful to the old man’s principles, Xiang finds himself unable to control his master’s widow and daughter, who are led astray by the widow’s worldly, greedy sister. At the same time, Xiang must ally with other triads to smuggle aid to the forces fighting the invading Japanese. He is torn between devotion to tradition and the need to adapt to modern materialism and the impending world war.

Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

Even more tightly buckled up are director Tang Huang’s obsessive hooks between scenes. A final line of dialogue is answered or echoed by the first line of the next scene; a closing door or character gesture links sequences in the manner of Lang’s M. Most daringly, when sister San starts to light a cigarette in one scene, we cut to her puffing on it in a tight close-up—a gesture that takes place in a new scene hours later. This and other admittedly gimmicky links look forward to Resnais’s elliptical matches on action in Muriel.

Fortunately for us, the Archive has published Always in the Dark: A Study of Hong Kong Gangster Films. Edited and partly written by Po Fung, it is an excellent collection of essays and interviews. It is in Chinese, but it includes a CD-ROM version in English. It’s available from the Archive’s Publications office.

Behind the scenes at Milkyway

Johnnie To and a recalcitrant crane during the shooting of Romancing in Thin Air.

Sometimes a genre film becomes a prestige picture. This happened, in spades, with The Grandmaster. If awards matter, Wong Kar-wai’s film has become the official best Asian film of 2013. I missed the Asian Film Awards in Macau (was watching early Farhadi films), but the event was a virtual sweep: seven top awards for The Grandmaster, including Best Picture and Best Director. After I got back home, the Hong Kong Film Awards gave the picture a staggering twelve prizes, everything from Best Picture to Best Sound.

Unhappily, nothing in either contest went to the other outstanding Hong Kong film I saw last year, Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Drug War. It lacked the obvious ambitions and surface sheen of Wong’s film. Many probably took it as merely a solid, efficient genre picture. I believe it’s an innovative and subtle piece of storytelling, as I tried to show here.

Mr. To presses on, as prolific as usual. He has finished shooting a sequel to Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, a rom-com that found success in the Mainland, and he’s currently filming a more unusual project in Canton. More on that shortly.

During the festival only one recent To/Milkway film was screened, The Blind Detective (I wrote about that here). But Ferris Lin, a young director from the Academy for Performing Arts, presented a very informative documentary feature on To and his Milkyway company. Boundless takes us behind the scenes on several productions, particularly Life without Principle, Romancing in Thin Air, and Drug War. It also incorporates interviews with To, his collaborators, and critics like Shu Kei.

Sitting at the monitor with his cigar, To may seem distant, but actually he is wholly engaged. We see him help push a crane out of the mud and shout commands to his staff. To confesses that he may scold too much, but the dedicated cooperation he gets confirms his demands. The team gives its all, as we learn when they explain the tension ruling the three days of rehearsal for the sequence-shot at the start of Breaking News. For The Mission, made at the time of Milkyway’s biggest slump, the actors supplied their own cars and costumes.

To remains a complete professional who has perfected his craft, albeit in the Hong Kong tradition of “just do it.” He doesn’t rely on storyboards or even shot-lists, only outlines of the action, and he adjusts to the demands of the locations. The Mission had no script, but the entire story and shot layout were in his head. For Exiled, he didn’t even have that much and simply began thinking when he stepped onto the set each day. It’s hard to believe that precise shot design and sly dramatic undercurrents can emerge from such an apparently unplanned approach. In its recording of To’s unique creative process, Boundless provides a vivid portrait of one of the world’s finest contemporary directors.

To continues to challenge himself. He is currently trying something else again, shooting a musical wholly in the studio. Its source, the 2009 play Design for Living, was written by and for the timeless Sylvia Chang Ai-chia. It won success in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. In the film Sylvia is joined by Chow Yun-fat, thus reuniting the stars of To’s 1989 breakout film All About Ah-Long. The project also indulges the director’s long-felt admiration for Jacques Demy. There is no 2014 film I’m looking forward to more keenly.

Special thanks to Shu Kei and Ferris Lin of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. Thanks as well to Li Cheuk-to, Roger Garcia, and Crystal Yau, as well as all the staff and interns of HKIFF, and to Winnie Fu of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Journey to the West (Tsai Ming-liang, 2014).

The other Kurosawa: SHOKUZAI

Shokuzai (2012).

DB here:

This year’s trip to Brussels and the Royal Film Archive of Belgium was more low-key than usual. The Cinematek’s mini-festivals were suspended this year, with Cinédecouvertes to resume next summer and the L’age d’or competition to get its own slot in the fall. The usually reliable Écran Total series at the Galeries Cinema was gone, replaced by mostly recent releases. The Cinematek’s main venue was featuring America in the 1980s (not to be despised, but these items were familiar to me) and Antonioni, because of the current exhibition devoted to him in the Musée des Beaux-Arts. And even my archive viewing was slimmed down to only a few days, as I watched some 1940s American features too obscure even to circulate on bootleg DVDs.

I wasn’t exactly bereft of choices, and I could occupy my time preparing for my Antwerp lectures on Ozu, but I was angling for something special. Luckily, our old friend Gabrielle Claes, recently retired as Director of the Cinematek, called my attention to a one-off showing of Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Shokuzai (“Penitence,” 2012) at Cinéma Vendôme, a local arthouse. The bonus: Kurosawa in person! So of course Gabrielle and I went.

Before and after the movie, I began thinking about his career and his place in recent Japanese film history.

Making waves in the 90s

Sonatine (1993).

During the 1990s a new generation of Japanese directors came to international attention. Thanks to home video formats, as well as to a rising taste for international crime and horror films, western audiences became aware of filmmakers from many countries who unabashedly worked in low-end popular genres. The success of Hong Kong films in 1980s festivals had made programmers open to Asian pulp fictions. Soon commercial companies saw a fan market for video versions of movies that were unlikely to get theatrical distribution outside Japan. These films changed forever the image of Japanese cinema as a refined and dignified tradition.

Admittedly, Western views of Japanese film were probably too sanitized. Ozu never shrank from bawdy humor, Mizoguchi could display acute suffering, and Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sanjuro were exceptionally bloody by 1960s American standards. Still, things had gotten quite wild in later years. Films that weren’t widely exported, such as those exploiting juvenile-delinquency, yakuza intrigues, and swordplay, as well as the softcore erotica known as “pink” films, would have shown western audiences something quite surprising. In the 1980s, charmers like Tampopo, The Funeral, and other export releases could hardly have prepared audiences abroad for the cinema of shock that was becoming common at home. Perhaps only Ishii Sôgo’s Crazy Family (1984), widely circulated in Europe and America, hinted at what was ahead.

The oldest provocateur was Kitano Takeshi (born, like me, in 1947), who came to directing after a solid career as a comedian. His Sonatine (1993) established him as master of the impassively violent, disturbingly amusing gangster movie. I don’t think anyone can forget Sonatine’s elevator-car shootout, which is unleashed after an awkward, semicomic passage of passengers behaving as we all do in an elevator, adopting neutral expressions and avoiding each other’s eyes. The most celebrated director of this group, Kitano influenced action filmmakers around the world and probably helped spark a revival of interest in classic yakuza pictures.

Other directors were younger and got their start in more marginal filmmaking. Tsukamoto Shinya had worked in Super-8 since childhood and made his breakthrough film, Tetsuo (1989) in 16mm, which became a cult hit on worldwide video. Soon Tetsuo II (1992), Tokyo Fist (1995), Bullet Ballet (1998), and other films showcased a frenetic, assaultive style that was the cinematic equivalent of thrash-rock. Miike Takeshi made several V-films before he hit international screens with Audition (1999), and soon his earlier theatrical releases Shinjuku Triad Society (1995) and Fudoh: The New Generation (1996) became staples of cult screenings and video collecting. Miike pushed things over the edge. Even Kitano did not dare to show a schoolgirl assassin firing deadly darts from her vagina.

I don’t mean to suggest that these directors were sensationalistic all the time. Miike made children’s films, a discreet heart-warmer (The Bird People in China, 1997), a mystical drama (Big Bang Love Juvenile A, 2005), and classical swordplay sagas (Thirteen Assassins, 2010). Kitano developed his interest in prolonged adolescence through sentimental drama (A Scene at the Sea, 1991), Chaplinesque road movie (Kikujiro, 1999), symbolic pageant (Dolls, 2002), and self-referential absurdity (Takeshi’s, 2005, and others). Still, these two directors have often returned to the downmarket genres that launched their reputations.

Nor do I want to suggest that all the filmmakers emerging to wider awareness at this time were roughnecks. Kore-eda Hirokazu began his career in documentary films, followed by the solemn, elemental Maborosi (1995). Kawase Naomi, one of Japan’s few women directors, won acclaim with the sensitive rural drama Suzaku (1997), and Suo Masayuki became a top-grossing export with his satiric comedies Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (1992) and Shall We Dance? (1996). Yet Kore-eda, widely respected for his nuanced family films, made a movie centering on a sex dolly (Air Doll, 2009), and Kawase had worked for years on autobiographical documentaries dealing bluntly with family tensions, old age, and women’s oppression. Suo’s debut was a pink film called Abnormal Family: My Older Brother’s Bride (1984) in which an affectionate parody of Ozu’s style was used to present copulation, teenage sex work, and a golden shower.

In sum, in Japan the distance between serious art and more sensual, not to say shocking, cinema isn’t that great. To take a more recent example, who would have expected that the director of the quiet, deeply moving Departures (2008; Academy Award, Best Foreign-Language Film) would have learned his craft in a series centering on men who grope women on commuter trains? (Sample title: Molester’s Train: Seiko’s Ass, 1985.)

Mysteries, mundane and supernatural

Shokuzai.

Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s career fits the trend I’ve sketched. Born in 1955, he started with pink films and V-cinema, but the theatrical release Cure (1997) won festival berths and international distribution. It presents the now-familiar mixture of mystery story and supernatural tale, in which a detective with personal problems investigates serial killings and begins to suspect that the murders are performed under some mesmeric influence. In Charisma (1999) the supernatural elements dominate, as a police officer tries to understand the powers of a tree that can magically regenerate itself. Pulse (2001) locates the otherworldly forces in the Internet, where ghosts take over people’s lives and eventually lead humans to flee Tokyo.

Kurosawa’s films became perhaps too quickly identified with what was known as J-horror. His taut, slowly unfolding plots and calm but menacing style did have something in common with the Ring series (1998-2000) that was becoming popular at the time. At the same time, Kurosawa draws on a some story elements common across Asian crime and horror films: revenge, often by a parent or elder figure in the name of a lost child; the suggestion that childhood, especially that of girls, has a corrupt and sinister side; and a sense that modern technology such as computers and cellphones harbor demonic threats. But I think that his films were more thematically ambitious, even pretentious, especially in the case of Charisma, with its ambiguous ecological symbolism. And like his peers, he wasn’t interested only in suspense and shock. His mainstream family drama Tokyo Sonata (2008) attracted western viewers with no knowledge of his spookier side.

The policier aspect is evident from the start of Shokuzai. Originally a five-part TV drama broadcast in weekly installments, it starts with the rape and murder of a schoolgirl, Emili. Her four playmates have seen her attacker ask her to leave the playground with him, so when she’s found dead, the police and Emili’s mother Asako press the girls to identify him. Through fear or trauma, none of the girls can remember what he looked like. Asako summons all four to her home and demands penitence from them in the future—in ways each one must find for herself.

After this prologue, Shokuzai downplays supernatural elements in favor of character studies of the four surviving girls, with a “chapter” devoted to each. The young women live separate lives and their paths don’t intersect; only the implacable Asako reappears in each thread. By the final installment, Asako has more or less given up tracking the killer, but when one young woman accidentally recognizes him, on TV, Asako pursues him and discovers the roots of the crime in her own past.

This is pretty much modern thriller territory, with a whiff of Barbara Vine/Ruth Rendell in the film’s effort to trace how a single event resonates terribly through innocent lives. As with such thrillers, the strength of Shokuzai seems to me to lie largely in characterization and atmospherics. Each young woman is given a distinctive personality, and each one’s professional and personal life fifteen years after the crime is presented with a teasing, hypnotic deliberation. Sae is a meek, sexually immature nurse who is lured into marriage with a rich former schoolmate; his seemingly harmless obsession turns domineering. Maki becomes a schoolteacher herself, and her relentless, demanding methods soon antagonize the local parents—until she unexpectedly proves herself heroic. Akiko has become a hikikomori, a recluse, and is only briefly drawn out of her drowsy existence by the daughter of her brother’s girlfriend. The good-natured little girl in effect reintroduces Akiko to childhood. In the penultimate chapter, the sexual bargainer Yuka seeks to seduce her brother-in-law and to take revenge upon her sister for being their mother’s favorite.

Each young woman is associated with an object or gesture seen in the prologue: a French doll, a bloody blouse, a policeman’s kindly squeeze on the shoulder. At one level, these bits of the past take on psychological impact. The trauma around Emili’s death suggests sources of the grown-up women’s neurotic behavior. Maki, the girl who after the killing rushes frantically through the school looking for someone in authority, becomes an all-controlling schoolteacher. Akiko’s bloody school blouse will find its fulfillment in a brutal crime involving a girl’s toy.

Yet these associations carry extra resonances. It’s partly because of the quietly ominous way Kurosawa films commonplace objects like a ruby ring or a jump rope. Maybe there is a whiff of the supernatural after all, given the unexpected connections revealed between the men in the women’s later lives and the little girls’ fetishes and rituals. Fate plays such cruel tricks that it might as well be malevolent magic.

The demand for expiation and the mother’s implacable intervention in an investigation will remind many viewers of Bong Joon-ho’s Mother (2009, South Korea) and Nakashima Tetsuya’s Confessions (2010). Asako’s characterization gets fleshed out in the fifth episode, which presents two crucial flashbacks leading up to the crime. One even replays a moment leading up to the murder, supplying a previously withheld reverse-shot in the manner of Mildred Pierce’s replay. (Some things don’t change.)

Presumably the recurring flashbacks to the prologue were also motivated by the rhythm of the weekly TV broadcasts. Viewers couldn’t be expected to recall everything from earlier installments.

You can object, as critics have, that the revelations in Shokuzai’s finale are creaky and far-fetched. Raúl Ruiz, in Mysteries of Lisbon, embraces the arbitrariness of old-fashioned plotting, with its felicitous accidents, secret messages, and hidden identities. He scatters these devices freely throughout his story, making them basic ingredients of his film’s world. Instead, Kurosawa introduces most such devices at the last minute, which makes them more surprising but also more apparently makeshift. Still, you can argue that once you eliminate purely supernatural causes for the creepy things we see and hear, audiences will embrace convoluted plots (as again, in Confessions) to rationalize their thrills. As so often in popular narrative, no coincidence, no story.

Quiet elegance

Kurosawa uses long takes, fairly distant framings, and solemn tracking shots to heighten an atmosphere of dread. The questioning of the children is played out in an extreme long shot, refusing exaggeration but conveying very well the flat, obdurate refusals confronting the cop.

In the Q & A after the screening, Kurosawa explained that he didn’t alter his filming style much for the television series, although he found himself writing more dialogue than he would have included in a theatrical feature. His visual technique displays a dry, precise elegance–the Japanese might say it possesses shibui— and it has, as far as I know, no equivalent in current American cinema. The compositions are painstakingly exact, though they’re not as rigidly geometrical as Kitano’s planimetric images and they don’t self-consciously evoke Ozu in the way Suo’s do.

Everything lies in plain sight. The bright, saturated tones of the childhood prologue contrasts sharply with the wan color schemes throughout the present-day sequences.

Kurosawa’s staging has a clarity and point that’s rare today. He often lets significant action unfold without interruption. For example, in Yuka’s flower shop, he gives us a shot lasting nearly a minute. Yuka’s sister has come to voice her suspicion that her husband has had sex with Yuka. Kurosawa moves the two women around the frame discreetly, sometimes hiding their facial reactions, and using the Cross to shift their positions both laterally and in depth. A single step forward can mark rising tension as the sister demands an explanation, and a retreat from the foreground can create a mini-suspense about Yuka’s reaction.

After hiding Yuka’s reaction in the distance, Kurosawa creates a mini-climax by having her turn abruptly to the camera before bending over and sobbing.

Kurosawa saves the cut, as David Koepp might say, in order to ratchet the drama up. In a closer view we can watch the sister, ashamed of her suspicions, consoling Yuka and succumbing to her lies.

Contrary to what proponents of intensified continuity will tell you, you can build an engrossing scene without fast cutting, tight close-ups, and arcing camera movements. Like American directors of the studio era, Kurosawa always knows the best place to put the camera, and he keeps things simple and direct.

Kurosawa’s patient, compact staging has its counterparts in the work of Claire Denis, Manuel de Oliveira, and many other European filmmakers. It’s just that it’s a bit unexpected in the 1990s Japanese iconoclasts. For all their self-conscious extremism, they have wound up reinvigorating certain classic techniques of cinematic expression. This is just one of many reasons to catch Shokuzai on a screen, big or little, near you.

You can see some trailers and extracts from Shokuzai here, but you have to sit through a wretched Peugeot ad every time.

Shokuzai is coming to the Vendôme on 24 July.

On the earthy side of Japanese culture, which I think feeds into the 1990s trends I’ve mentioned, see Ian Baruma’s Behind the Mask.

P.S. 23 July 2013: Adam Torel of the ambitious Third Window Films writes to tell me that the company is releasing Eyes of the Spider and Serpent’s Path on DVD in September. Third Window distributes other recent Japanese films, including items by Miike and Tsukamoto.