Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

Bringing to book

Artists and Models.

Blushing from Bryce Renninger’s generous article about us and the new edition of Film Art can’t keep us from offering another of our occasional entries devoted to new books we like. Get ready for lots of peekaboo links.

The rise of the Soviet Montage film movement of the 1920s and western countries’ knowledge of those films came about largely because of Germany. After pre-revolutionary film companies fled the Soviet Union, taking much of the country’s film equipment with

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

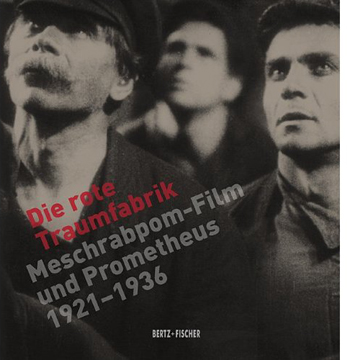

There was a direct link between Soviet and German socialist film production and distribution that is too little-known today. In 1921, Willi Münzenberg forms the Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (the IAH, known in Russia as Meschrabpom), based in Berlin. In 1924, the organization founded a film studio in Moscow, Rus. A year later, a sister company, Prometheus, was formed in Berlin. Both produced films, and they cooperated in distributing each other’s output.

Meschrabpom-Russ produced many of the familair Soviet classics: early on, Polikuschka and Aelita, and later the films of Pudovkin (including Mother and The End of St. Petersburg) and Boris Barnet (including Miss Mend and House on Trubnoya). Prometheus produced films highly influenced by the Soviet exports, both in terms of style and subject matter. These included Leo Mittler and Albrech V. Blum’s Jenseits der Strasse, Phil Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück, and, mostly famously, Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Ottwald’s Kuhle Wampe oder wem gehört die Welt.

Prometheus, not surprisingly, disappeared in 1933. Meschrabpom-Russ continued until 1936.

A retrospective at the Internationale Filmfestspiele in Berlin in 2012 has occasioned a comprehensive, beautifully designed catalogue, Die rote Traumfabrik: Meschrabpom-Film und Promethueus 1921-1936. With numerous expert essays and beautifully reproduced illustrations, both in color and black and white, of posters, production photos, film frames, and documents, this is the definitive publication on the subject. Even those who don’t read German will be able to use the extensive filmography and the biographical entries on the directors and other people involved in the making of the films. The illustrations make this the perfect combination of academic study and coffee-table art book. (KT)

Closer to home, our friends have been very busy. From Leger Grindon, a deeply knowledgeable specialist in American film, comes Knockout: The Boxer and Boxing in American Cinema. The prizefight movie isn’t usually discussed as a distinct genre, but after reading this comprehensive and subtle study, you’ll likely be convinced that it’s been remarkably important. While discussing movies as famous as Raging Bull and as little-known as Iron Man (no, not that one; this one comes from 1931), Leger also introduces you to the finer points of genre criticism. The way he traces basic plot structures, key iconography, and historical patterns of change is a model of how thinking in genre terms can illuminate individual films.

Then there’s Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin. Ethan de Seife goes beyond the usual recounting of peculiar, often lewd gag moments to treat Tashlin as not only a gifted director but a representative figure in 1940s-1950s American cinema. Ethan traces how Tashlin became a program-picture director who never acquired the status of auteur, at least in the eyes of the studio system. The book situates Tashlin in the context of the Hollywood industry, both the cartoon shops (Tashlin did animation work for both Disney and Warners, among others) and the live-action production units. There’s as well a fascinating chapter on Tashlin’s influence on directors as different as Joe Dante and Jean-Luc Godard, who coined the adjective “Tashlinesque.” A blend of critical analysis, cultural commentary, and industry history, Tashlinesque is surely the definitive book on this cheerfully dirty-minded moviemaker. Ethan maintains a lively blog here.

Not strictly about cinema, but a book that’s indispensible for film researchers, is James Cortada’s History Hunting: A Guide for Fellow Adventurers. A founding member of the Irvington Way Institute, Jim is at once an IT guru, a historian of computer technology, and a scholar of Spanish history, particularly of the Civil War. History Hunting, the fruit of forty years of spelunking in archives, museums, and the world at large, is an enjoyable handbook on doing historical research. It ranges from help with genealogy (case study: the colorful Cortadas, from Spain to the US) to suggestions about how to frame a doctoral thesis. Jim reminds us that the historian must turn into an archivist: the materials you collect are documents for future historians to use. You are, to use the new buzzword, a curator. Jim provides a welter of practical suggestions along with his own tales of the hunt. Jim devotes part of a chapter to Kristin and me, which just goes to show his impeccable taste in neighbors.

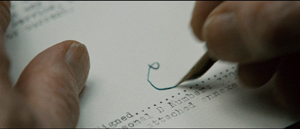

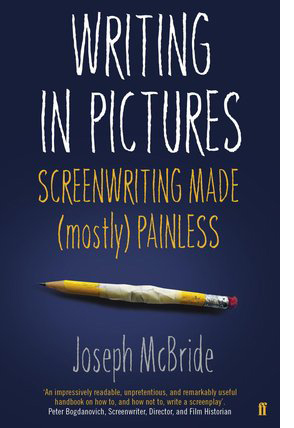

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

One of the most original aspects of Writing in Pictures is Joe’s emphasis on adaptation. This is sensible because (a) a great many films are adapted from other sources (today, even comic books); (b) a professional screenwriter is often called upon to reshape an earlier script draft by another writer; and (c) adapting a preexisting source swiftly gets the novice screenwriter thinking about the relative strengths of verbal and visual storytelling. Joe takes us through the script-building process step by step, each time reworking London’s story “To Build a Fire.” Somewhat like the European “conservatory” approach to film education, McBride’s emphasis on organic interaction with classic traditions is something new, even radical, in the world of American screenplay education.

Then there’s Film and Risk, edited by the boundlessly prolific and enthusiastic Mette Hjort. Probably the most conceptually bold cinema book of the year, it assembles several scholars and filmmakers to assess how films and filmmakers deal with risk. The subject is of course broad. There’s risk in performance; risk in breaking stylistic boundaries; risk within film institutions (such as producing); risk in social and political contexts such as facing censorship; environmental risks, as in the costs that filmmaking exacts from the natural world; and even the risks of viewing movies—exposing yourself to horrifying or depressing stories and images. Film scholars like Hjort, Paisley Livingston, and Jinhee Choi mingle with film producers and industry observers to reflect on how cinema takes chances.

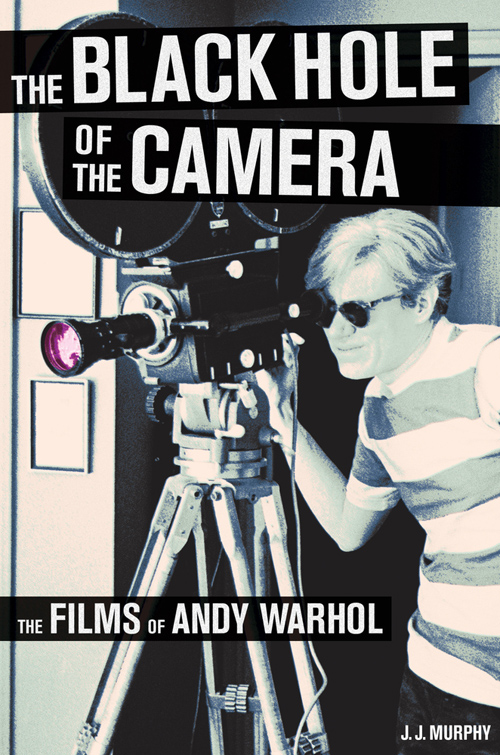

Our colleague J. J. Murphy has been researching and teaching the films of Andy Warhol for years, and today–literally, today–his monograph The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol comes out from the University of California Press. This is the most comprehensive, in-depth study of Warhol’s filmmaking that has ever been published, and of course a must-have for anyone interested in experimental film or the American art scene.

The ideas are fresh, especially the explorations of Warhol’s debt to psychodrama. At the same time, The Black Hole of the Camera clears away many misconceptions about Warhol (no, Sleep and Empire are not single-shot films) while also offering detailed information about and analysis of little-known stunners like Outer and Inner Space. There are several pages of color frames, which remind you that Warhol was as good at color as Tashlin was. JJ maintains a remarkable blog on independent cinema and is a leading figure in the Screenwriting Research Network.

Not a book, but a publication of great value: Three major researchers have collaborated on a cogent, nontechnical review of experimental investigations into film perception. All of the authors have had face time on this site. Dan Levin has executed breakthrough experiments on “change blindness”–how we miss discontinuities and anomalies in everyday life. (On another dimension, Dan’s film Filthy Theatre is coming up at our Wisconsin Film Festival.) James Cutting, a venerable figure in visual perception research, has ranged across many key areas in his consideration of cinema. He also wrote a wonderful book, available free here, on Impressionist painting. And Tim Smith, virtuoso eye-tracker, is author of one of our all-time most popular blog entries, “Watching you watch There Will Be Blood.”

With three top talents, you’d expect the collaborative paper to be a triumph of synthesis, and so it is. It supplies the best case I know for why we cinephiles should welcome psychologists who test the ways we watch movies. It should be required reading in every film theory course in the land. Access to the published paper requires a purchase or a library subscription, but you can read the preprint version here. Check in at Tim’s blog Continuity Boy for plenty of videos exploring his research (DB).

Finally, we’re sometimes asked why we don’t allow comments on our blog. The simple answer is that we’re not nearly as good at responding to comments as John Cleese is.

The cover of Joe McBride’s book pictured above is from the Faber & Faber edition, which makes a better still than the US edition from Vintage. Same good stuff inside, though.

TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

DB here:

As the final credits rolled, a man behind me blurted out, “I don’t get it.” He’s not alone. Kristin and some acquaintances have told me that they found parts of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy hard to follow. Several critics, while praising the film (and doubtless getting more of it than that guy), have warned viewers to pay close attention. Roger Ebert said:

I enjoyed the film’s look and feel, the perfectly modulated performances, and the whole tawdry world of spy and counterspy, which must be among the world’s most dispiriting occupations. But I became increasingly aware that I didn’t always follow all the allusions and connections.

Some of the film’s admirers advise us not to worry much about the intricate storyline. Michael Phillips remarks:

This is one of the finest achievements of the year, and while it’s easy to lose your way in the labyrinth, I don’t think “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” is most interesting for its narrative pretzels. Rather, it’s about what this sort of life does to the average human soul.

Even if I weren’t a le Carré fan, I’d be fascinated by a film that can succeed both critically and financially and still leave its audience puzzled about its plot.

Critics of popular filmmaking claim that our movies cater to simple minds, but we actually find a lot of successful films, from Groundhog Day and Pulp Fiction to Inception, that are complex in intriguing ways. I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It that since the 1960s one current of filmmaking has explored narrative strategies that were minor, even unheard-of, options in earlier times.

I’m not ready to join Steven Johnson in suggesting that audiences have become smarter. In certain respects older films are more demanding than contemporary ones. I’d rather say that new conventions are in force, aimed at certain sectors of the audience who are willing to put forth the effort. Ambitious filmmakers may find new ways to fulfill these conventions, balancing novelty with intelligibility. This is the path, I think, that the makers of Tinker Tailor took, and it didn’t prevent the film from earning $17 million at the US box office.

The film’s ’70s patina isn’t off-putting. The filmmakers offer deliberately grainy imagery, enveloped in hazes of rain and cigarette smoke. The palette, except for Ricki Tarr’s idyll with Irina, is grey, brown, and beige. Scenes are shot with long lenses, rack-focus, and drifting tracking shots. Zooms and push-ins are interrupted by cutaways. The result is an Altmanesque look, but more disciplined. It’s not the visual style, then, but those the narrative pretzels—another reminder of late ‘60s and early ‘70s storytelling—that attract my notice today.

So I persist: What makes the movie hard to grasp? If we can get a sense of this, we might get to know Tinker Tailor more intimately, while also producing some ideas about how mainstream films work generally. To attempt an answer, I have to go into detail. I won’t be supplying a plot synopsis, but the Wikipedia entry is reasonably comprehensive. I’ll be looking less at the story and more at the storytelling. Still, don’t read further if you haven’t seen the film. In the tradecraft jargon of blogging: There are spoilers ahead.

Breaking up the blocks

One factor contributing to the film’s difficulties, as many reviewers have pointed out, is that it’s adapted from a big and complex book. But it isn’t just the size of the original novel that poses problems. It’s the way the plot is constructed and the story is narrated.

The plot of the novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (published 1974; the commas aren’t in the adaptations) consists mostly of blocks of flashbacks. The action starts long after Control has died and his old staff, including George Smiley, has retired. The novel’s first scenes show Jim Prideaux’s arrival at the boy’s school, seen from the perspective of Bill Roach, his shy confidant. We don’t yet know how Jim connects to Smiley, who after a dinner with a gossipy acquaintance, is summoned to investigate the prospect of a mole in the Circus’s top echelon.

Smiley’s investigation involves questioning witnesses like Connie Sachs, but more often it involves “burrowing,” working patiently through the files that Control had studied. Le Carré presents what Smiley gleans from the files as flashbacks, and interwoven with those are Smiley’s reflections on the key personnel and their power struggles. Institutional memory and Smiley’s rueful recollections tie together the ambush of Jim Prideaux and the vein of top-secret information code-named Witchcraft.

Respecting the novel’s construction would demand a cascade of long tales framed by Smiley’s step-by-step pursuit. Arthur Hopcraft’s screenplay for the seven-installment 1979 BBC series took the simpler option of starting with a scene that is presented very late in the novel, during Jim’s revelatory confession to Smiley. The TV series opens with Control summoning Jim and sending him off to Czechoslovakia. Jim is shot and Control is cast out. Clarifying the string of events this way, and giving us a decent action scene early on, has its cost: Smiley doesn’t enter the series for twenty-three minutes.

Since Hopcraft and director John Irwin had hours at their disposal, the scenes could stretch and breathe, and they retain the somewhat chunky, modular quality of the novel. But a two-hour film couldn’t handle the book’s plot so spaciously. What did the team of Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan do? Straughan explains:

The adaptation process differs from book to book, but in the case of “Tinker Tailor,” it involved a kind of mosaic work. The structure of the novel was broken into pieces. Some long sequences would remain intact – Peter Guillam stealing the files from the Circus, for example – but in other cases we would take a line or event from one place in the narrative and move it elsewhere, shifting the fragments around endlessly until it felt right. The goal was to create a new version of the narrative which would bear a close family resemblance to the source material, but have its own cinematic personality. The really difficult part was not fitting the plot into two hours but doing it without losing the tone; to give the film the same autumnal, melancholy pace, and to give the script air and silence.

The most obvious instance of this fragmentation is the repetition of the ambush of Bill Prideaux in the Budapest café. In keeping with current norms of storytelling, this scene is replayed at crucial points, each time giving us a bit more information relevant to the scenes of testimony around it.

Repetition is a luxury that can’t be overindulged in adapting a hefty novel. To spare time for the pace, the air, and the silences the filmmakers want to include, they had to be more concise in their presentation of plot. They had to chop le Carré’s big narrative blocks into bits.

When we view a mosaic we can step back to see how the composition blends all the fragments. But we have to experience a movie bit by bit. A film, we might say, is a moving mosaic, and we are usually standing very close to it. Just as important, a mosaic, made out of gaps, leaves it to us to grasp how the parts fit together—to make our mind jump the gaps.

Unconventionally conventional

How does Tinker Tailor fit the pieces together? In general, the film adheres to common conventions of modern storytelling but then subtracts one or two layers of redundancy. The little gaps created make the film seem roundabout today, when rather linear and explicit narration is the norm.

Start with a simple case. Like many modern spy films, Tinker Tailor initiates a shift to another locale by a long-shot framing, often from on high. Here’s an example from The Bourne Ultimatum.

It’s triply redundant: We see a city landscape including the Arc de Triomphe; we’re told it’s Paris; and we’re told it’s Paris, France (not Paris, Maine). Compare the parallel shot from Tinker Tailor.

Not exactly a difficult leap—who doesn’t know that the Eiffel Tower is in Paris (France)?—but it’s a little less explicit. Earlier instances are more laconic. When we’re taken to Budapest and Istanbul, probably not as immediately recognizable to many in the audience as Paris, we get a cityscape with only one mention in the dialogue to tag the setting, and no captions. Least explicit of all are the shots picking out the Circus in London.

Another film would have typed out, “MI6 HQ,” but we’re left to infer that behind this façade the Secret Intelligence Service does its work. So the convention of the exterior establishing shot is respected but made a little less redundant.

Consider as well the introduction of the Circus’s decision makers. Another film might have started with Smiley and followed him from his office into the briefing room. Instead, he’s introduced as one of several men, then as an out-of-focus figure alongside Control. And even Control could have been more clearly identified. He signs his resignation with what could become an emblem of the film’s stingy approach to storytelling.

Just as truculent is the process by which Lacon is led to summon Smiley. First Lacon gets a warning call from the field agent Ricki Tarr. So far, so conventional. But Tomas Alfredson has staged things so that Tarr is seen at a distance, turned from us, and blocked by a phone booth. Who is this guy? We must get all our information solely from his voice, not his facial expression.

Soon after Peter Guillam has entered the Circus, he gets a call. Most directors would have cut away to the caller, or at least let us hear what Peter is hearing. But we’re denied that information. On the soundtrack, we hear only a muffled, “It’s Oliver…ringing…” It’s Lacon, but you know that only if you know his first name is Oliver, and we’re teased by hearing almost nothing of what he’s saying. We know even less than Guillam, and this suppressive narration is characteristic of Alfredson’s handling of genre conventions.

Next we see Smiley at home, watching television. There’s a knock at the door. Cut to a car driving, Peter at the wheel and Smiley in the back seat. Smiley is silent, and Peter offers his regrets: “I was sorry to hear about Control, Mr. Smiley.” Earlier we’ve been given one shot of the dead Control in the hospital. So much for his backstory.

Finally, as the car pulls up at Lacon’s house, the fragments combine into an intelligible sequence when Peter says, “He said Tarr called him from a phone box.” Retrospectively, we can buckle the sequence up as a familiar genre action: The hero is called back to the battle by his chief.

Another convention, one that goes far back, is the dialogue hook. This is a bit of speech that ends one scene and links directly to the next one. Tarr calls Lacon and names Guillam as his supervisor. Cut to Guillam crossing the street and entering the Circus. Later, Smiley suggests that he and Guillam investigate Control’s flat. Cut to them entering it.

Dialogue hooks, as I’ve traced out here, are enormously helpful in guiding us through the plot. But sometimes Tinker Tailor works more obliquely. In one scene Peter reads of the staff who were sacked following Control’s fall. One is Jerry Westerby, whom we’ll meet a long while later, and the other is Connie Sachs. Cut to a train station, with Smiley buying a ticket to Oxford. It’s a hidden hook: most films would include in the earlier scene a line such as, “Connie Sachs, who’s now in Oxford.” Again, a conventional device is roughened a bit, made slightly more difficult. And sometimes the hook is visual and disruptive, as when a shot of Jim, bleeding in the Budapest arcade, is followed by a shot of the boy Bill Roach looking out a window at Jim’s arrival, as if he’s also looking down at his future teacher.

The BBC series was broadcast in weekly episodes, so recapping and backtracking in each installment helped viewers remember. At intervals we see Smiley bringing Peter up to date and briefing Lacon on current discoveries. The film flagrantly refuses to provide this conventional help. As Ebert notes:

More ordinary spy movies provide helpful scenes in which characters brief each other as a device to keep the audience oriented. I have every confidence that in this film, every piece of information is there and flawlessly meshes, but I can’t say so for sure. . . .

What replaces the standard briefing scenes? Some rather elliptical passages. There are the nodes in which Smiley reflects on the evidence. We get a shot of him staring, followed by a cascade of imagery as his mind plays with possible suspects.

Linked to the briefing scene is another convention, the board or wall on which all the suspects are diagrammatically arranged. In our visit to Control’s apartment we might have seen pictures of Bill Haydon, Roy Bland, Toby Esterhase, and Percy Alleline laid out in a rectangle, with the sinister silhouette of Karla up top, and dotted lines connecting them. Yet Control, the bedraggled chainsmoker, could hardly be so tidy. Instead, the film gives us something more in character and more oblique: a litter of chessmen, each with a picture taped awkwardly on. Eventually Karla is revealed as another piece (the powerful white Queen). On his own, Smiley joins in Control’s conceit and tapes a picture of the new suspect Polyakov to a bishop.

Le Carré’s novel tied the suspects together with a verbal emblem, based on the child’s nursery rhyme. It linked the boy’s school to the Circus. But the film doesn’t introduce the tinker-tailor motif until very late. Instead the chess pieces visualize the multiple-choice problem, but in a ragged, haphazard way that suggests that perhaps Control really was, as Jim Prideaux suspects, going mad. More broadly, the imagery (with the briefing room as a gridded checkerboard) reminds us that spying, known for decades as The Great Game, is now a global chess match. It pits Karla against Smiley—whom Control has identified as the black Queen.

George the Obscure

Again and again, the script and Alfredson’s direction invoke a convention only to make it more difficult to grasp. The central examples involve Ann, the faithless wife. She isn’t just treated elliptically; she’s suppressed. Instead of showing her flirting with Bill at the Christmas party, we see only the back of her head and Bill looking past Smiley’s shoulder.

In a later flashback to the party, Smiley looks out the window and sees Ann in the garden. Another film would have shown us who’s clutching her in the foliage, but this film leaves it to us.

Of course many viewers will know Ann’s partner is Bill, but another film would have confirmed this more explicitly. Instead another standard scene is handled in a glancing way. More generally, Ann’s phantom presence not only makes her seem remote, like a princess in a tower, but sets her off against the blonde Irina, the maiden to be rescued in Ricki Tarr’s story. Thanks to the camera and a compact mirror, Irina’s face gets the caresses another film would devote to Ann.

Irina, beautiful and sincere, holds the film’s major secret, the one that initiates Smiley’s investigation. She harks back to the blonde mother who is in the line of fire in the Budapest arcade, and that shooting prefigures Irina’s fate.

The crowning achievement in the film’s laconic way with conventions is the climax in the safe house. Smiley has arranged for Ricki to send a message that will force Karla’s mole to make an emergency appointment with his connection Polyakov. There Smiley, Guillam, and Mandel will record the meeting and capture the double agent. In the BBC series, this climax runs over eight minutes, built out of crosscutting and suspenseful waiting. Smiley and Guillam burst in together and a quick pan shot reveals Bill as the culprit.

The film uses suspense and crosscutting as well, but the sequence consumes only six minutes. More important, by switching our attachment away from Smiley at the crucial moment, it conceals his entry to Bill and Polyakov. Instead we follow Guillam separately into the house, up the stairs, and to the parlor. There he confronts the aftermath of what might have been a heroic confrontation. Climax is treated as anticlimax.

Jim Emerson, in a nicely honed piece, suggests that we think of such passages as not so much elliptical as economical. I want to have it both ways. The scenes are economical because they fulfill familiar narrative and genre-based functions: We know how to fill them in. Yet they’re also elliptical because they hold back information, sometimes a little and sometimes a lot. A mosaic can show us familiar people and things, but it also asks us to make extra effort to see the pattern emerge. The tesserae fit, but the bumps and grooves between them are palpable.

It may be that art films have always tended to be self-consciously wrought genre films. L’Avventura: A mystery-melodrama. Blow-Up: A detective story. Drive: the thinking person’s action film. If so, then Tinker Tailor is the smart Bourne movie. Creative novelty needs a familiar base to play off. Movies come from other movies, and originality can take a tradition, even a popular one, as a point of departure for innovation.

Best watcher in the unit

Once plot gaps have alerted us, we should expect things to proceed through hints. Granted, there are hints that can’t be picked up unless you know the novel. For instance, the film doesn’t stress the fact, emphasized in the novel, that Bill is an amateur painter and the canvas he brings Ann on the fateful night is one of his own works. It’s the picture that Smiley is studying at the end of the credits sequence, as if the film’s two primary antagonists are already squaring off.

But, sticking just to the hints we can pick up without the novel, the film is fairly rich. It invites multiple viewings, as many movies do nowadays, in order to catch the undercurrents or the things that flash by too quickly on the first pass. (If we want to find more, we can buy the DVD.) I can’t pretend to exhaust the possibilities, but here are some that strike me.

Go back to those chessmen. As we’ve seen, the two antagonists, Karla and Smiley, are made parallel as the rival Queens. Three suspects are assigned to innocuous pieces: Percy as the white Rook, Toby as the black Knight, and Roy as the black King (although that assignment might be a narrative feint, hinting that Roy’s the traitor). But Bill is the white Bishop, and in retrospect we can see the fact that Smiley makes the Moscow agent Polyakov a black Bishop is a pointer to Bill’s guilt—and maybe a suggestion that, as Bill will say, George knew all along.

Or take the homosexual element. One question that comes up in conversation after the movie is whether Bill and Jim were lovers. It’s treated as a possibility in the original novel and becomes stronger as the film proceeds, especially after Bill—in a moment of privileged information for the audience—pockets a picture of the two friends embracing and laughing. By the end, in the final flashback of the Christmas party, Bill rouses the loner Jim and flashes him a smile; but the brandy glass he floats away with seems intended for Ann. Bill’s bisexuality is explicit in the epilogue when, in the compound, he asks Smiley to pay off both a girl and a boy. More than a hint, as well, is the tear that dribbles down Jim’s cheek as he executes his friend. (Bill’s wound, rhyming with Jim’s perforated back in Budapest, again recalls the slain mother in the arcade.)

Similarly ambivalent is the presentation of the dapper Peter Guillam. He’s introduced turning his head to watch a cute young lady pass. Later he’s revealed to be gay: for security reasons, he has to break up with his partner. In retrospect, we can see the shot when Bill and Peter eye the new clerk Belinda as presenting two double agents, each one passing as a lady-killer.

More minor touches hint at the sexual undercurrent. Bill on the phone: “And I said you may fuck me but you still have to call me sir in the morning.” It takes a quick eye to spot another manifestation of the motif. Polyakov, posing as a cultural attaché, writes articles for a bilingual magazine. After Connie has told her tale, there’s an insert—an excerpt from Connie’s memorabilia, or perhaps only a memory of Smiley’s—of an article signed by Polyakov, which says of the Russian Ballet corps:

To see them only in a narrative ballet would be to know them incompletely. The programme shows a perfect cross section of their accomplishments.

They can dazzle us with a technique that seems to defy the laws of gravity but that is not merely acrobatic because it is truly gay in expression.

Like the dancers, Bill and Jim are both athletes and acrobats, powerful and graceful. I can’t prove this implication was intended by filmmakers, but by chance or design, it’s a fragment that fits.

Or take the Christmas party. There the tune, “The Second-Best Secret Agent in the World” ramifies outward to several second-besters: that night Jim is Bill’s second-best lover, Smiley is Ann’s second-best lover, and Smiley is the agent outwitted, at that point, by Bill. Another hint: At the height of the evening, the USSR anthem is sung ironically by the Circus staff, while Bill, an undercover Soviet, is off in the garden. Not to mention that as Control signs his retirement papers, he asserts: “A man should know when to leave the party.”

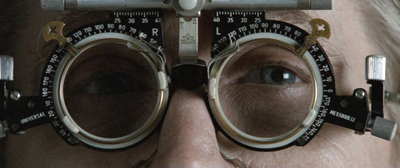

Above all are the eyeglasses. Promoted in the film’s publicity (when Oldman found them, he found the character), they become associated with seeing things as they are. The old hornrims seem to be something of a shield; Smiley pushes them back into place after he sees Bill with Ann. But once Smiley has gotten his new, more powerful pair after leaving the Circus, he uses them as an instrument of scrutiny. They enlarge his vision eerily; often they’re lit and in focus when his eyes aren’t. And they hide his eyes from others.

Although he bears Bill’s name, the podgy boy Roach is a closer parallel to Smiley. For him and for George, spectacles are a sign of wary vigilance. Jim praises Roach: “Best watcher in the unit, I’ll bet. As long’s he’s got his specs on, aye?” The motif may come from a passage in the novel that is recast for the film. Bill tells Smiley that Karla had worried that Smiley would catch him.

Karla said you were good—the one we had to worry about. But you do have a blind spot. And if I was known to be Ann’s lover, you wouldn’t be able to see me straight. And he was right—up to a point.

But those were the old glasses, and Smiley was a more vulnerable man then.

Saint George?

The novel is based, as most people know, on the revelation back in 1963 that a cadre at the center of the British Secret Intelligence Service was in the pay of Moscow. Kim Philby was the central figure, surrounded by Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, and “the fourth man” identified later as art historian Anthony Blunt. In a scathing introduction to a 1981 book on the conspiracy, le Carré diagnoses the scandal as symptomatic of an endemic weakness in Britain’s ruling class. (Yes, he uses that phrase, which no American politician dares to utter.)

Was he not born and trained into the Establishment? Effortlessly he copied its attitudes, caught its diffident stammer, its hesitant arrogance; effortlessly he took his place in its nameless hegemony. . . . The SIS quite clearly identified class with loyalty.

He might be describing Bill Haydon:

Philby, an aggressive, upper-class enemy, was of our blood and hunted with our pack; to the very end he expected and received the indulgence owing to his moderation, good breeding, and boyish, flirtatious charm.

Worse, the agency that was pledged to protect Britain had insulated itself from reality, somehow seeing in an American-promoted anti-Communism a small rebirth of the Raj.

Whatever went on the big world outside, England’s flower would be cherished. “The Empire may be crumbling; but within our secret elite, the clean-limbed tradition of English power would survive.”

Le Carré’s lacerating remarks remind us that he might be our only major popular novelist who has held uncompromisingly critical positions on international affairs, including the Iraq war and the growth of American militarism and corporate power.

But the polemicist isn’t identical with the novelist. Tinker, Tailor provides a far more ambivalent picture of betrayal. Le Carré the polemicist has created in Haydon a perfect embodiment of what he despised about British Intelligence and the class system that feeds it. The parallel world of the boys’ school evokes the origins of the corrosive ethic that led to Bill’s treachery.

Yet the novelist spares his traitor the worst. For one thing, Peter Guillam, who idolized Haydon, can’t summon up condemnation.

Despite his banked-up anger at the moment of breaking into the room, it required an act of will on his own part—and quite a violent one, at that—to regard Bill Haydon with much other than affection. Perhaps, as Bill would say, he had finally grown up.

Smiley, who has every reason to hate Bill, is at a loss. He mulls over how he should judge the man who has done such monstrous things. As a friend worthy of respect who stood by his convictions? As a committed thirties intellectual? As a romantic elitist clouded by ideology? As an esthete who elevated his distaste for Philistinism to a political principle? As a superficial man in the grip of a compulsion to betray?

Smiley shrugged it all aside, distrustful as ever of the standard shapes of human motive. He settled instead for a picture of one of those wooden Russian dolls that open up, revealing one person inside the other, and another inside him. Of all men living, only Karla had seen the last little doll inside Bill Haydon.

In the book, Smiley’s uncertainty about Bill leads him to hope for a reconciliation with Ann. For him, unlike Bill and Karla, love isn’t an illusion or cover story. In the TV series, for all his triumph over the Alleline cadre and Karla’s mole, he returns to Ann and her chiding: “Poor George, life’s such a puzzle to you, isn’t it?” But the film gives us a different Smiley, and it interprets his reward quite differently.

We can approach the problem through performance. The TV series makes Smiley a stern schoolmaster, keeping his own counsel but voluble, thanks to the fluting of that Guinness voice. His facial expressions work a narrow range, but are very nuanced within that compass. Here is Guinness shifting, minutely, from polite approval to a steely comprehension while his oblivious informant chatters on.

By contrast, as every critic has noted, Oldman’s Smiley is virtually blank for most of the film. His frog-mouth, half-open or clamped shut, remains impassive. Guinness lets us into Smiley’s mind as he interrogates his targets, but Oldman’s most marked reactions are brow-wrinkling concentration and puzzlement. The high point, George’s discovery of Ann’s disloyalty, elicits only a gasp and a gape (and a pushing up of the glasses). As usual, even that reaction is muffled a bit, this time by the profile angle.

Similarly, everything conspires to make George obscure. Framing, setting, and lighting put him far from us, wrap him in shadows, let reflections on his spectacles block his eyes.

Guinness’s Smiley isn’t hard to read, once you tune to his high, narrow frequency, but Oldman’s Smiley is a sphinx. And it seems to me that this poker face works toward a new conception of Smiley’s role. The elliptical narration conspires with Oldman’s performance to create a conclusion that is far more harsh than what we find in the book or the series.

Early on, the film shows us George shamed. Control, forced to resign, announces that Smiley will leave with him. It evidently comes as a surprise to Smiley, who—in a moment that many critics have rightly praised—turns his head slightly and after a beat and a blink accepts with a tiny nod. For the rest of the film, George’s head-turns will be his principal signal of surprise, uncertainty, or sudden realization. (It’s even contagious: his adversaries execute the same gesture, and even Guillam catches the habit.) Smiley and Control stalk out of the Circus as exiles and part on the sidewalk without a word and Smiley comes home to an empty house.

Summoned back into service, he launches his investigation. In a key scene in the novel, the series, and the film, he confides to Peter his meeting with Karla long ago, when he tried to persuade the Russian to switch sides. The meeting disclosed a faultline in Karla’s character (“He’s a fanatic, and the fanatic is always concealing a secret doubt”), but it revealed Smiley’s weak spot too. Asking Karla to think of his wife, Smiley betrayed his worries about Ann. Karla retained the cigarette lighter that Ann had given Smiley, a token of Smiley’s fear of losing her. Years later, cuckolded by Bill at Karla’s behest, Smiley adds sexual shame to professional disgrace.

There’s a certain mystery about how the movie Smiley cracks the case. In the book and the series, there’s a lot more evidence about the mole than we get in the film. In the turning-point sequence, subjective montages lead to a burst of images and recurrent lines from Ricki: “Everything the Circus thinks is gold is shit.” Smiley is convinced there really is a mole, chiefly because of Jim Prideaux’s testimony, but we have to reason on trust: the reappearance of Karla and the murder of Irina before Jim’s eyes connect the mission to Budapest with the Witchcraft files.

The TV Smiley reveals his reasoning in a very lengthy interrogation of Toby Esterhase. Over fifteen minutes, Smiley builds a plausible case and forces Toby, to avoid suspicion that he’s the mole, to reveal the location of the safe house. Lacon is briefed offscreen, and George is given permission to set the trap.

But the film Smiley acts very differently. He confronts Lacon and the Minister and bluntly announces that there’s a mole, that Karla controls him, and that SIS has been feeding the Americans trivia and lies. He offers no evidence. The officials are shaken solely by Smiley’s uncharacteristic vehemence. His mocking conviction smashes their resistance and they give him permission to go after Toby.

With Toby, Smiley again uses brute force. No reasoning, no evidence, just the bald threat of throwing Toby onto the plane and shipping him back over the Curtain. Cringing and whining, Toby gives up the safe house’s address, and George can proceed to set the trap. And this comes after the moment when Smiley, knowing full well that Irina is dead, promises Ricki to do “his utmost” to retrieve her. Guinness’s Smiley makes the same promise, but in his gentleness we sense a man pained by his bad faith. Oldman’s Smiley is as guarded as ever.

I submit that the Smiley of the film, once he has overpowered his superiors, can’t spare a moment to brood over Haydon’s personality. He proceeds largely from a vindictive, controlled aggression. Lacon fired him, Alleline despised him, Toby insulted him, and Bill betrayed his marriage. Behind that severe blankness, I think, burns a desire to avenge Control, and to get a bit of his own back. When that mask slips, in talking with Lacon and the Minister, he’s nearly gloating.

The film, in sum, seems to me to offer a legitimate reinterpretation of the Smiley character. His fierce anger is rather close to le Carré’s attitude toward Kim Philby: The man may have been an enigma, but he was still despicable. The difference is that while le Carré can castigate the man in print, George can pay his traitor back. In this dirty game, he can finally checkmate Karla.

Was it worth it? The novel leaves you wondering. In its final pages, Smiley moves toward uncertain reconciliation with Ann. Jim’s future is more hopeful: after killing Haydon, he returns to the school and rebuilds his relation with young Bill, the other “new boy.” The only hope, it seems, lies in human relationships, not in a frigid bureaucracy.

But in the film, Jim harshly breaks off with the boy, and Smiley triumphs. To the music of “Beyond the Sea,” the losers—Ricki, Connie, Bill—are glimpsed. But Smiley, having kept his own counsel throughout, is a winner. There’s little sense here of le Carré’s distaste for the institution that nourished Bill and his breed. Smiley reenters the Circus, in a smart new suit and topcoat, striding to the top floor and taking Control’s seat, to offscreen applause. (I grant you there’s a bit of irony in that sound effect.) And how else to explain the vignette before that when, after the death of Bill Haydon, Smiley comes home to find Ann there? The sailor of the song has returned to the woman who has been waiting for him. Beggarman has gotten what Ricki saw in Irina: Treasure.

In preparing this entry, I was much helped by James Schamus and Khaliah Neal of Focus Films. Thanks also to Jeff Smith and Kristin for conversations about the movie.

For more on the film’s artistic approach, see Jean Oppenheimer, “A Mole in the Ministry,” American Cinematographer 92, 12 (December 2011), 28-34 (apparently not available online). After explaining that DP Hoyte van Hoytema and Alfredson sought “a grainy, somewhat colorless look,” the article reports van Hoytema saying that the zoom shots were modeled on 1970s ones: “When I look at films from the ‘70s, I like the fact that the zooms are so functional and solid. They have a beginning and an end.”

Le Carré’s introduction may be found in Bruce Page, David Leitch, and Phillip Knightley’s The Philby Conspiracy (Ballantine, 1981). Valuable studies of le Carré’s work include Peter Lewis, John le Carré (Ungar, 1985) and Michael Denning, Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987). In an earlier entry I offer an appreciation of the second book in the Karla trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: John le Carré in right foreground.

PS 1 March: In a followup entry, I explore other aspects of Tinker Tailor.

Dante’s cheerful purgatorio

Twilight Zone: The Movie.

DB here:

When will we baby boomers relax our chokehold on popular culture? Never, if the enthusiastic response to Joe Dante’s visit to Madison last weekend is any indication. A showing of Gremlins (1984) packed the house. A screening of his Twilight Zone: The Movie episode brought fans forward with DVD slipcases to sign. College kids reminisced about watching The ‘burbs with their dads and Explorers with their buddies (all on video, of course).

Although steeped in classical Hollywood, intimately acquainted with the most obscure output of the studios, Dante hasn’t abandoned the present. He shoots TV shows, webisodes, and the 3D feature The Hole (still awaiting a US release). He hosts a website, Trailers from Hell, in which directors comment on other directors’ works using a trailer as a point of departure.

His films, from Piranha (1978) and The Howling (1981) to the present, by way of Amazon Women on the Moon (1987) and Matinee (1993), combine the gonzo spirit of the 1960s with a good-natured reverence for the past. Particularly movies. Particularly crazed, tasteless movies. Like Spielberg and Peter Jackson, he’s a fanboy. “Most filmmakers are kids at heart,” he says. “And all actors are.”

Unlike Spielberg and Jackson, though, Dante keeps politics close to the surface. His films sustain the baby-boomer hope that you can squeeze cultural critique into a genre project. Everybody knows that the Gremlins movies are subversive trips into the shadows of bourgeois normalcy. Has a shiny kitchen blender ever been used more efficiently?

The Gremlins pictures and The ‘burbs are valentines compared to Homecoming, Dante’s installment in the series Masters of Horror. This asks a simple question: Suppose that all the soldiers killed in combat were able to come back and vote? Is that a powerful lobbying group or what? When resurrected vets of Iraq start stalking to the polls, an Ann Coulter lookalike tries to stop them. Run on cable in 2005, this left-wing zombie movie slashes to ribbons pious platitudes about war’s costs. It’s required viewing for all 2012 presidential candidates.

Don’t crowd me, Joe

Dante began his career as a collagist. That’s not too fancy a name for a man who, with his friend Jon Davison, collected the ephemera of the great age of 16mm. TV shows, ads, and movie trailers swept out of local stations went into their archives. In time these and other glories of late-night TV found a new life, like a monster stitched together out of morgue remains. The strategy was simple. Dante and Davison rented five or six 16mm sub-B features and projected stretches of them, in rough order but jumbled together. The movies were interspersed with reels of clips.

The Movie Orgy played college campuses in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Orgy lasted about seven hours, and its auteurs urged viewers to drift in and out. “Go get a pizza whenever you want. You won’t miss a thing.” Eventually Schlitz hired them to take it around the country and sold beer at the screenings.

When Dante began working for Roger Corman’s company—cutting trailers, thereby tapping his skills as a collage-maker—The Orgy was suspended. But some years ago the footage that he could find was transferred to digital and played at the New Beverly. It found a new success. Dennis Cozzallo has a lively tribute from 2008 here. Needless to say, we had to have The Orgy for Dante’s visit to Madison.

Affection for the detritus of the media takes many forms. After watching too many campus simpletons (both students and profs) laugh mockingly at Fritz Lang and John Woo movies, I’m opposed to condescension. I suspect Camp in its disdainful form. I don’t like people demonstrating their sense of superiority to the trash their parents and grandparents enjoyed. Knowingness leaves you with nothing.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

Moreover, in sequence after sequence, there’s a quality of astonishment that doesn’t make us feel superior. Take one exemplary moment of dépaysment. If you and I tried to be naive or trashy, we couldn’t come up with this.

Andy Devine hosted a kiddie TV show, Andy’s Gang, which featured Froggy the Gremlin (Plunk your magic twanger, Froggie!), the cat Midnight, and Squeeky the mouse (played by a hamster). About an hour into The Orgy, Andy induces Midnight to play a miniature pipe organ while Squeeky accompanies him. Cut to a deep-focus shot of what seems to be a slightly drugged cat locked in place and rhythmically pawing the offscreen keyboard. In the background Squeeky, apparently clamped within a mechanical mouse body, bangs a tiny bass drum. Andy sings along tunelessly. The song is “Jesus Loves Me.”

You don’t laugh, you gape. It’s like one of our local attractions, The House on the Rock: What’s disturbing is not that it’s done poorly, but that somebody thought of doing it at all.

The form of The Orgy—and it does have a form, of sorts—is to open with openings and end with endings. Several of the movies get started in the first half hour (Dante and Davison love opening credits) and we’re given enough of the plots to become curious. Most prominent are Attack of the 50-Foot Woman and Speed Crazy, the latter receiving a loving dissection highlighting, and repeating to the point of obsession the heel protagonist’s tagline, “Don’t crowd me, Joe.” Eventually the guy and his flashy sports car wind up crowded, all right–crowded into a ravine.

More TV episodes and movies get added as the hours roll by, and by the end we’re facing Armageddon. Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Chicago, New York, DC—every major city is under attack by some alien or giant monster. Sky King has to dump dynamite for some reason, Superman has to save Lois from a pistolero. A sort of amphetamine Intolerance, The Movie Orgy cuts together all these climaxes, which include The End titles that are far, far from signaling the end.

The clip from Andy’s Gang reminds us that the piece is somewhat misnamed. It’s a Movies And TV Orgy. More specifically, it’s a Movies On TV orgy. The structure of the whole shebang imitates a long stretch of television ca. 1955-1960. Over lunch Dante recalled watching Million Dollar Movie as a kid in New Jersey, seeing a feature shoehorned into a ninety-minute slot and chopped up by commercials. The Orgy replicates the jagged tempo of switching among three or four channels, glimpsing variant commercials for Colgate toothpaste or Raleigh cigarettes, catching a bit of this movie and then a bit of that one. With all its kid shows from my youth (The Lone Ranger, Lassie, Mighty Mouse, etc.) in endless eruption and interruption, it’s a baby-boomer time capsule. Puncturing this evocation of childhood are the clips scavenged from teenpix and Dick Clark’s dance show, Vietnam, Nixon’s Checkers speech, and film-society icons like the Marx Brothers, Fields, and Abbott and Costello. The late sixties counterculture breathes more fully in some clever fake ad spots. In one, a crucifix starts to wobble as the carved Jesus struggles to free his hands.

Dante claims that he and Davison were inspired to find out about the popular culture that shaped their parents’ generation. But nearly everything we see filled the airwaves during our younger days as well. The Movie Orgy in its current form seems to me a zestful celebration of the world our generation saw when we flopped on our bellies, propped our chins in our hands, and stared at the tumultuous world inside a black-and-white (not color) TV (not video) set (not monitor).

We cartoon characters can have a wonderful life

Dante the collagist leaves his fingerprints all over another film he screened here. When Spielberg launched his Amblin company, he hunted for directors who could make family entertainment in a genre format. Dante, who had already started Gremlins, was invited onto the omnibus Twilight Zone project. After the fatal accident on the Landis set, the studio backed off and it become “a movie they wanted to make but didn’t want anything to do with.” This gave Dante wide latitude and made him think, mistakenly, that studio suits always leave directors alone.

For this episode, Dante wanted to do an original story but Warners insisted that it had to be based on an episode of the TV series. He went back to the original Jerome Bixby story, which Dante and Richard Matheson reworked to add cartoons as a running gloss to the comic horror. The pseudo-family of demonic little Anthony inhabits a house that is half cartoonland, half-PoMo-Caligari. Saturated colors, occasionally striped with noir shadows, provide another Dante caricature of family domesticity, but now cartoons comment on the action. When Helen steels herself to eat, the dog on the screen behind her is doing the same.

The crisscrossed shadows of the corridors are replayed in the sawtooth walls pursuing Bimbo.

The collage principle gets developed further in Dante’s use of the soundtrack. The Movie Orgy uses no new sound work; the clips are just spliced together. But for the Twilight Zone episode, let loose in Warners’ classic archive, Dante could weave in Carl Stalling music (reorchestrated for stereo by Jerry Goldsmith) and a rich mélange of daffy sound effects.

The TV is incessantly on. The cartoons running in the background supply whizzes, boinks, and thuds that jarringly punctuate the conversation between puzzled teacher Helen Foley and the family that Anthony holds in his magical grip. “This is Helen,” says Anthony, introducing her to Uncle Walt and his sister, as we hear a smash from the TV set. The cartoon tracks comment on the action too. As the family settle down in front of the tube, the elders dote on Helen and we hear a Stalling rendition of “Ain’t She Sweet?” Dinner is served to the tune of “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic.” And when Helen discovers her burger has been slathered with peanut butter, the visceral image is underscored by warbling winds that rise when she lifts the bun. Eisenstein, for reasons given here, would have loved the moment. The whole sequence plays out as live-action animation, with naturalistic dialogue and effects given a creepy overlay by the cartoon track. Is Helen Foley’s last name part of the gag?

Dante, impresario of the comic grotesque, finds his inspiration in popular culture, the more wacko and inept the better. The comedy may come from childhood silliness, the grotesque from childhood fears. They say we baby boomers will always be just big kids, and Dante accepts this with a grin and a darkly cheerful eye.

Many thanks to the resourceful Jim Healy for arranging his friend Joe Dante’s trip to Madison. Thanks as well to the Cinematheque, the Marquee, and the Chazen Museum of Art for hosting the screenings.

John Carradine in The Movie Orgy.

Forking tracks: SOURCE CODE

Source Code.

DB here:

Who cares if the Source Code software is junk science? The muzzy premise forms the basis of an agreeable little thriller from the tail end of this year’s Dead Zone. Even if you don’t share my admiration for this movie, maybe I can persuade you that it points up an intriguing wrinkle in the recent history of American studio storytelling.

I surveyed this history in some books, but Source Code provides a nice occasion to update my argument. My main point remains: More than we often admit, today’s trends rely on yesterday’s traditions. Quite stable strategies of plotting, visual narration, and the like are still in play in our movies. When a movie does innovate in its storytelling, it needs to do so craftily. The more daring your narrative strategies, the more carefully, even redundantly, you need to map them out. The game demands clarity through varied repetition.

More generally, there’s a value in thinking of movies as combinations and transformations of inherited conventions. We’re used to considering conventions as matters of theme and genre, but I’m equally interested in conventions of technique and of narrative form. These are areas we’re still only starting to understand, although many entries on our site try to make progress in understanding changing norms of style and storytelling. (Check our Narrative Strategies category for further leads.)

If you haven’t seen Source Code, you shouldn’t read on. I reveal damn near everything.

He couldn’t come home

Colter Stevens awakes on a Chicago commuter train in the body of another man, Sean Ventress, who’s accompanying the attractive Christina Warren. Very soon the train explodes, and Colter reawakens in a pod in a military facility. He learns that after being shot down in Afghanistan he has been at the Nellis facility for two months, awaiting an experiment in “time realignment.”

Because a person’s brain activity does not cease immediately at death, memory modules can be accessed across an eight-minute period before full shutdown. Colter’s brain anatomy happens to be attuned to that of Ventress, so the experimenters can in effect insert his mind into Ventress’s body in the few minutes before the train explosion. The investigators know that the bomber is planning to set off a much bigger explosion in downtown Chicago, and Colter-as-Ventress could gather enough information to prevent it.

Under the tutelage of officer Goodwin and her superior, chief researcher Rutledge, Colter will be sent back in to the train, neurally speaking, to try to identify the bomber for them. He cannot prevent the train blowup, Rutledge insists. He can only hope to identify the bomber before the dirty bomb goes off downtown. But Colter can, in the shrinking time remaining, be sent back again and again, though it’s physically and emotionally punishing for him.

As a result, the film alternates between two zones of action. At the Nellis facility, time moves forward as Colter gradually comes to understand his circumstances and his mission. This action is under the pressure of a deadline: find the culprit before the dirty bomb is triggered. The other zone of action is the train, where the deadline is tighter (eight minutes before Ventress’s death) and the action is replayed as Colter tries different tactics to fulfill his charge.

Many incidents fill out this dynamic. In the pod, the early scenes are dominated by Colter’s efforts to understand the experiment he’s involved in and to grasp what has happened to him since his chopper crash. He is being kept alive artificially so that his brain activity can sync with Ventress’s. Eventually he breaks through Goodwin’s façade of coldness, converting her to sympathy for his plight. When she finally stares compassionately down at his broken body in its glowing casket, she resembles a mother or nurse looking down at a baby. On the train, the early scenes throw up some decoy suspects, most prominently an agitated man of vaguely Middle Eastern appearance. He is proven not to be the bomber, who’s eventually revealed as a dough-faced nerd. (Between the stereotyped Islamic terrorist and the stereotype domestic one, the plot opts for the latter.)

Colter not only blocks the Chicago bombing; with Goodwin’s help he is sent back one last time to stop the train bombing as well. In the course of that effort, he manages to reset the past, creating a parallel world in which the briefcase bomb never ignited and the bomber was captured before he left the train. Colter, dead at the Nellis facility, becomes Ventress wholly, able to spend a day with Christina and to send a text message to Goodwin promising that the Source Code has even bigger possibilities than Rutledge imagines. It can change the course of events. And she can reassure Colter’s original self, when he finally is sent on a mission: “Everything’s gonna be okay.”

It’s the new me

This plot is articulated in quite traditional ways. At less than 90 minutes, the film yields three large-scale parts or “acts.” The Setup introduces us to the premises, establishing the train bombing and the Nellis facility supervision; I’d argue that this ends at about 28 minutes. At this point Colter, has to rule out his chief suspect, the commuting businessman with motion sickness, when the train explosion takes place. The second stretch of the plot consists of more failed efforts, but culminates at about 56 minutes, when Colter correctly identifies the bomber, Derek Frost. Again, he can’t forestall the train bombing, but returning to his capsule he passes the key information to his masters, and they can arrest Derek before the dirty bomb hits Chicago. At this point his official mission is over. But the movie isn’t. Colter persuades Goodwin to let him go back one more time to stop the train bomb and save the passengers—effectively countermanding Rutledge’s injunction that the past can’t be altered. A three-minute epilogue starting around 82:00 wraps things up.

Filling out this structure is the characteristic double plot of classical Hollywood: heterosexual romance plus another, usually connected, line of action. The suspense plotline is organized as a series of goals, initially articulated by Goodwin. She tells Colter to find the bomb, which he does in the first replay. But as he can’t prevent the explosion, he needs to know more about who’s behind it. His next passes proceed in steps. He has to identify the guilty passenger; then he must try to steal the conductor’s pistol; then he searches for bomb-related paraphernalia.

About halfway through the film, however, Colter conceives purposes of his own. Inside the capsule, he probes Goodwin about what has happened to him. On the train, he starts to investigate the insignia of the agency controlling him, to trace his own fate in Afghanistan, to try to contact his father, and to phone the Nellis facility. He’ll eventually succeed in all these attempts, balancing the failures of the first chunk of the plot. Ultimately he’ll decide to try to save the train. Crucially, this last goal is formulated after he believes that having been more or less killed in Afghanistan, he is about to be terminated by the Source Code project. So he can now operate in a mode of pure self-sacrifice. As often happens in a classical film, a character finds the resources to throw off others’ demands and make decisions on his own.

In the romance plotline, by assuming the identity of Sean Fentress, Colter becomes attached to Christina. Now saving the train takes on a more personal weight; he will be saving her. The emotional dimension here is deepened by Colter’s backstory, his unresolved relation to his father. Eventually he is able to get closure by posing as Fentress and phoning tell the grieving old man that Colter indeed loved him. In screenwriters’ parlance, Colter is “exorcising his demons.”

Colter’s growing confidence in dealing with his past and the bomb threat changes his behavior toward Christina. No longer the skittish neurotic of his early incarnations, he becomes brisk and confident. Eventually he can relax, paying the standup comic across the aisle to entertain the other passengers. As often happens, character change is measured by a repetition. The first time Colter says, “It’s the new me,” he refers ironically to his discovery that he’s in another man’s body. But now, as the comic launches into his shtick, Christina points out that her companion has changed. He answers by saying, “It’s the new me,” which signals a deeper acceptance of his sacrificial role. He doesn’t expect to survive after he returns to the capsule, but he has saved the people on the train and he can for a moment celebrate a final moment of vitality.

This is not a simulation

These cascading goals and character arcs emerge gradually, thanks to cunning narration. At first we’re restricted largely to what Colter knows, but gradually our awareness widens. We come to learn about Goodwin’s role in the Source Code project and about Rutledge’s ruthless efforts to use Colter as a test case. By the climax, the film cuts freely between the two arenas, the train and the Nellis compound, creating classical suspense as Goodwin postpones erasing Colter’s memory while he races to prevent the train blowup. This is the Griffith heritage of the last-minute rescue.

For the viewer, the film starts with mystery—Colter is on the train and he doesn’t know who he is—and moves toward a mixture of curiosity about his past and suspense about how he will solve his problem. By the start of the climax, we have understood all the forces converging on Colter’s last mission, and sheer suspense takes over. There is, though, one final surprise, which seems to have worried other critics more than it does me. More on this shortly.

Even before the explicit widening of narrational knowledge, we’ve been given a dose of something enigmatic. The shifts from the train explosion to the Nellis pod are provided with whooshing transitions of blurred and fragmentary imagery that, as the film goes on, clarify a bit. At the film’s center, these images will be replaced by distorted flashbacks to his helicopter crash in Afghanistan, a passage that leads him to ask Goodwin: “Am I dead?”

One of the images glimpsed in the vortex montages is that of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate sculpture, which Christina and Colter-as-Sean will visit in the epilogue.

Thematically, the image can be taken as an emblem of the lives Colter has saved, with a hazy overlay that reminds us of his floating consciousness for most of the movie. But the more basic question is about the status of these blurry visions. Are they Colter’s premonitions of a future to come? That assumption seems confirmed at the end when Colter, staring at the sculpture, asks Christina if she believes in Fate. At the same time, the images can be treated as coming from outside his ken, as if the film were providing teasing hints about how the action will resolve.

In these montages we see an interplay between destiny and chance common in Hollywood storytelling. (Christina answers Colter’s question by saying she’s “more of a dumb luck kind of girl.”) Very often, even if chance seems to govern the plot, a film’s overarching narration seems to “know” how things will turn out. Thus the film can have it both ways, acknowledging that life sometimes depends on chance but also recognizing that satisfying stories feel inevitable.

As usual, you will have eight minutes

Since the early 1990s, many films have resorted to what we might call“multiple-draft” plotting, the replaying of key scenes with important variations. Groundhog Day (1993) is our prototype, and it influenced Source Code screenwriter Ben Ripley. An earlier instance is the alternative futures revisited by Marty McFly in Back to the Future II (1989). Yet these films revived an older, although minor, trend going back quite far in Hollywood. The device was sometimes used to present alternative futures, as in The Love of Sunya (1927), but more commonly it presented different characters’ versions of what happened in the past. We find it in the courtroom drama Thru Different Eyes (1929), which dramatizes conflicting trial testimony, and in Crossfire (1947), which somewhat anticipates Rashomon‘s use of the strategy. Contradictory replays are used for more comic effect in The I Don’t Care Girl (1953) and Les Girls (1955).

What led to the resurgence of multiple-draft storytelling in our day? Partly, I think, the changing genre ecology of Hollywood. During the 1970s and 1980s, certain genres like the musical and the Western faded out, and horror and science-fiction/ technofantasy became more important. These genres, still going strong today, encourage playing around with subjective states (dreams, hallucinations), devising misleading narration, and creating branching and looping timelines (through time-travel, telepathy, multiverses, and the like). The filmic experiments probably owe something as well to the rise of popular writers in the vein of Stephen King and Michael Crichton, along with the revival of the work of Philip K. Dick.

Pop science also furnished new narrative possibilities. Researchers discovered the Butterfly Effect: change one little condition at the start of a process, and you get a different result. There was the Forking-Path, or Choose Your Own Adventure, option, whereby you can imagine taking a different path in your life. And there was the Multiple-Universe Hypothesis, whereby we can hop from one parallel world to another.

Even without the pseudoscientific justification, the reset-replay option showed up in films that were influenced by earlier storytelling. Film noir sometimes resorted to replaying scenes in ways that filled in information missing on the first pass (e.g., Mildred Pierce, 1945). Tarantino made no bones about being influenced by the overlapping flashbacks in The Killing (1955), themselves derived from Lionel White’s original novel Clean Break. So in the wake of Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Jackie Brown (1997), we got many thrillers and crime films that retold the same events from different characters’ viewpoints (Out of Sight, 1998), right up to an almost endless series of replays (Vantage Point, 2008).

All of these multiple-draft tactics made their way into global cinema too; Run Lola Run (1998) is a prominent example, but so too is the dazzling anime The Girl Who Leaped through Time (2006). In America, the market’s constant demand for something novel (but not too novel) pushed filmmakers toward all the variants we see in films as different as Thirteen Conversations about One Thing (2001) and Confidence (2003).

For mainstream filmmakers the key is redundancy. The reset-replay device has to be explained through dialogue, diagrams, intertitles, and sheer repetition so that we understand it going forward. (Contrast, say, Primer, which left most viewers behind.) Once we’ve grasped the similarities in the core situation, we can measure the differences in each iteration.

Source Code director Duncan Jones had already shown an interest in replays in Moon (2009), with its Möbius-band treatment of the crashed lunar vehicle, followed by Sam’s awakening in the infirmary. The mystery of the first encounter, in which Sam seems to find another version of himself in the vehicle, gets slowly cleared up through dialogue, the discovery of a secret repository, and not least important, a bandaged hand wound that allows us to keep the two Sams more or less distinct. Similarly, in Source Code, the returns to the train can be more elliptical as we master the situation: the introductory shots (duck pond, Colter waking up) can be skipped or compressed. Our training is guided by Colter’s, as he starts to predict the trivial incidents (coffee spill, cellphone call from Christina’s ex) and handle them matter-of-factly. These repetitions anchor us and allow us to register the different actions he undertakes in each module.

Those modules are ruled by another convention, what screenwriting manuals call the ticking clock. Usually reserved for the climax of films in all genres, even romantic comedies, the ticking clock plays a bigger role in Source Code. It governs both the macro-level (the deadline to stop the dirty bomb) and every return to the train. Strikingly, those replays are very strictly contained. Colter is assigned eight minutes for each mission, and by my count each of the developed train episodes before the climax consumes anywhere between four and eight minutes of screen duration, never more. His recurring deadline becomes a structural cell of the movie.

We have a chance to start over in the rubble

Déjà vu.

Multiple-draft storytelling promises to abandon the classic “linearity” of Hollywood storytelling, but the promise is largely a tease. The convention gestures toward unruly complication, but it tends to reinstall linearity, sorting everything out and making the final stretch of the film seem a logical consequence of what went before. Despite all the cycles and skip-backs of Groundhog Day, Phil changes incrementally into a kinder person and gets the woman he has come to deserve. In the money-drop sequence of Jackie Brown, the minute variations of point-of-view mesh into a single comprehensive account of how the scam went down. Part of the fascination of the technique for us may be similar to what a child feels after spinning around and stopping: the dizziness is fun, but so too is the bumpy readjustment to a stable world.

Source Code wants a happy ending. Does it prepare us sufficiently? We have the vortex transitions that look forward to the Cloud Gate epilogue, but are these enough? Don’t we need something at the level of plot action?

In his last visit to the train, Colter manages to disarm the briefcase bomb and capture Derek Frost. So now the train didn’t explode; the Nellis facility was never put on alert to forestall the dirty bomb; Rutledge and Goodwin never tried using Colter as their Source Code guinea pig. Rutledge earlier denied that this revision of the past would be possible, but the plot nonetheless moves us into a parallel world characteristic of forking-path plots like Run Lola Run and The Butterfly Effect (2004). And this reality has become sovereign, since Colter can now successfully send Goodwin a text message advising her about the unexpected success of the Source Code stratagem. This also means that as more or less a brain in a vat, the wounded Colter survives to serve in other missions.

Given the right sort of motivation, then, the forking-path option can be activated as a resolution device for multiple-draft plots. The film’s makers invoke a multiverse explanation explicitly in one piece of publicity for the film (trailer 2 here). More important, we’re prepared to accept such a switch on pretty slender evidence. Counterfactual thinking in terms of forking paths is a part of our folk psychology. If only we’d left the parking lot ten minutes earlier, we wouldn’t have hit this traffic. If I hadn’t taken this job, I wouldn’t have met my husband….and so on. Despite what experts like Rutledge say, when we see Colter disarm the lethal briefcase, we’re prepared to buy the possibility that everything afterward has changed.

Still, we need some elements in the movie itself to justify the jump. During his final questioning of Goodwin, Colter asks if she could imagine a world in which she didn’t get divorced, being “a woman who took a different fork in the road.” Colter insists that the course of events is changeable: Christina “doesn’t have to be dead.” At various points he says he thinks he can save the train, but like Rutledge, Goodwin reasserts that there’s only one reality, and its events have already happened.

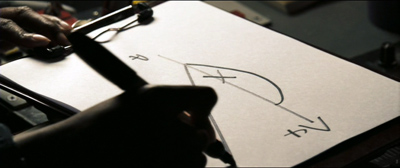

Interestingly, the debate itself might be a minor convention of the multiple-draft plot. In Tony Scott’s Déjà vu, (2006) a close analogue to Source Code, two scientists disagree about whether the past is malleable. Professor Denny says that you cannot change what’s already happened. “God’s mind is made up about this.” But his colleague Shanti adheres to the “branching universe theory,” which she helpfully draws on paper for our benefit (echoing Doc’s famous diagram in Back to the Future II). A significant event, Shanti maintains, can shift the course of events and create a new path. It can even, she claims, wipe out the branch that was initially taken as baseline reality.

Images of linearity deflected, of hiccups and branches off a main line, show up in Source Code too. The train bomb is fired off just as another train passes on a parallel track. But in the final replay, after Colter has set things right and paid the comedian to do his turn, we see “all this life”—the passengers frozen in amusement. The shot is a kind of marker that, as Shanti puts it, something big has changed. Abruptly we get a shot we haven’t seen before: a high angle of our train switching to another track. Then we cut back to Colter and Christina about to kiss, as the rival train passes safely. Our train’s new trajectory confirms that an alternate reality has been put in place. It also echoes an earlier line, when Christina, talking about her plans for the future, asks Colter: “Am I on the right track?”

This will end