Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

METROPOLIS unbound

Fritz Lang has created a lot of pretty pictures and has discovered the astonishing talent of Brigitte Helm. I cannot blame him for not being able to cut the quantity of ideas in individual scenes mercilessly enough (the water catastrophe, the duel), but instead repeatedly trying out new lighting and angles. This time the film’s qualities lie precisely in these efforts: and if the viewer knows how to make the best of something, he will derive pleasure from these images.

Rudolf Arnheim, review of Metropolis, 1927.

Along with La Roue and The Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis (1927) is one of the great sacred monsters of the cinema. Many versions circulate, and restorations never seem to stop. A beautifully restored, though incomplete, version was premiered in Berlin in 2001. This is the basis of the most authoritative DVD releases. By now, however, everybody has heard about the 2008 discovery of a significantly longer version in Argentina, a 16mm preservation copy drawn from a scratch-infested 35 nitrate original.

Since 2008 a team at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung has been at work adding material from the Argentine version to the earlier one. Kristin and I have written earlier entries (here and here) tracing the progress of the restoration, and the team have produced a detailed website explaining their work. The result made its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, and an exhaustive exhibition about the film has been running at the Deutsche Kinematek in Berlin.

Now I’ve seen it, at a screening during the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Frank Strobel, a member of the restoration team, conducted the Hong Kong Sinfonietta, and another collaborator, Martin Koerber, curator at the Deutsche Kinematek, was present to discuss the restoration process. A handsome booklet, cosponsored by the Goethe-Institut of Hong Kong, provided a lot of background. The film was projected digitally, but at very high resolution and looking quite crisp. I had a front-row center seat. I had a swell time.

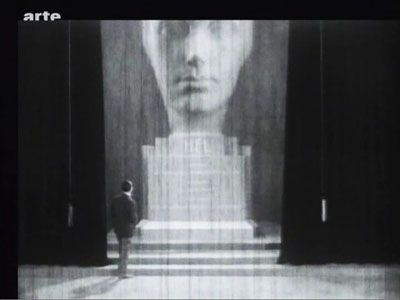

Metropolis has never been my favorite Lang of the period, but this version makes the strongest possible case for the film. It’s hard to dislike its shameless, preposterous ambitions, its stew of biblical and modern ingredients, its bold architectural vistas, and its trancelike characterizations. Also, people running crazily about in gargantuan spaces can usually hold your interest.

I just met a girl named Maria

All [the American editors] were trying to do was to bring out the real thought that was manifestly back of the production and which the Germans had simply “muffed.” I am willing to wager that “Metropolis” as it is seen at the Rialto now is nearer Fritz Lang’s idea than the version he himself released in Germany. . . . There was originally a very beautiful statue of a woman’s head, and on the base was her name–and that name was “Hel.” Now the German word for “hell” is “hoelle” so they were quite innocent of the fact that this name would create a guffaw in an English speaking audience. So it was necessary to cut this beautiful bit out of the picture . . . .

Randolph Bartlett, The New York Times, 13 March 1927

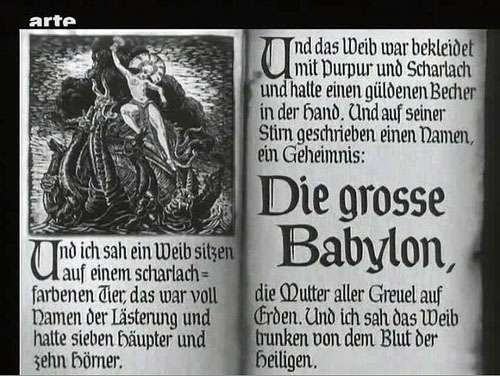

The new version gives the film a better narrative balance. Somewhat surprisingly, the plot hinges on one of the oldest and simplest narrative devices: mistaken identities. The overlord Fredersen engages the crazed scientist Rotwang to create a mechanical Maria who will lead the workers astray. Rotwang takes the occasion to avenge himself on Fredersen by having his robot urge the workers to destroy the machines. Two Marias, then–actually more, if you count the robot Maria’s incarnation as the Whore of Babylon in the Yoshiwara Club.

Thanks to the Argentine footage, we now know that another major character doubling involves Freder. At the start of the version we all know, Freder is visited by Maria and a flock of children. Upon seeing her radiant charity, he becomes suddenly convinced that he must join the oppressed workers, his “brothers and sisters.” Helping them has become his destiny. He gains an ally in Josaphat, an employee whom his father has brusquely fired. Descending to the cavernous machine halls, Freder switches identities with Georgy, a worker who returns aboveground to live Freder’s life. Freder wants him to go to Josaphat’s apartment, where they will meet. But the Thin Man, a long, leering hireling of Freder’s father, is charged with trailing Freder.

Stretches of the Thin Man subplot are missing from the previous version, but now we can see that Georgy/ Freder is a sort of early counterweight to the Maria/ Maria parallels. As in the latter case, the switch leads to misunderstanding, with the Thin Man following Georgy to the club and eventually to Josaphat. The Georgy substitution also allows Harbou and Lang to introduce the Yoshiwara Club early, but teasingly, in a rapidly dissolving montage. Only later will we get a good look at the delicious degeneracy inside.

As Martin Koerber indicated in several remarks, the older, most common version of Metropolis turns it into a science-fiction film, since it puts the robot Maria at the center of the plot. Just as important, though, is Freder’s plan for overturning class oppression, something fleshed out in the Georgy/ Josaphat material. Other new footage puts the relationship between Fredersen and Rotwang in a new light. We now see that Rotwang was in love with Fredersen’s wife Hel, and he has constructed not only a huge bust of her but also a “mechanical man,” outfitted with a distinctly female anatomy, as a sort of Hel substitute.

Fredersen diverts Rotwang’s plan to the purpose of mimicking Maria. So we get another doubling: Freder’s mother Hel becomes the firmware for the robot Maria through the machinations of two father figures. (Freder will kill one and redeem the other.) In all, the new footage yields a play of eerie Freudian substitutions.

The 2010 restoration also establishes the film as consisting of three large-scale movements. The first section, “Prelude” (Auftakt), runs a bit more than an hour. It shows Freder joining the workers and his father planning to have the Thin Man follow him. This part also introduces Rotwang, establishes Fredersen’s order to make a robot Maria, and ends with Rotwang’s capture of Maria. A second part, called “Intermezzo” and lasting about thirty minutes, is devoted to intertwining the Freder/ Josaphat plot with the creation of the robot Maria. The section more or less climaxes with a demo of the new Maria, dancing sexily at the Yoshiwara.

In “Furioso,” everything builds to a climax across a remarkable fifty minutes. The cloned Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines, fulfilling Rotwang’s plan to avenge himself on Fredersen, while the real Maria escapes from Rotwang’s compound during a fight between Rotwang and Fredersen. (We’re still lacking some of this footage.) At the same time, Freder and Josaphat converge on the underground city. The workers’ smashing of the machines triggers a flood from which the children must be saved. At the finale, during a hand-to-hand struggle with Freder, Rotwang falls to his death. There follows the famous epilogue in which Freder, “the Mediator,” must bring together hands (the foreman Grot) and head (the capitalist Fredersen).

Fluidity and freedom

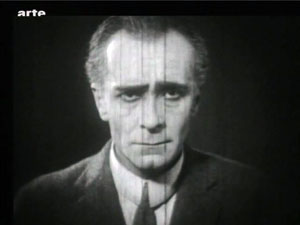

This delirious fable is rendered with unrelenting zest. Lang has now perfected his breathless version of silent-film narration. He relies on simple, immediately graspable compositions, rapid crosscutting among different plotlines, and a dynamic approach to analytical editing.

In the late 1920s, many American films became more heavily dependent on intertitles; it’s as if directors were anticipating talkies. But of Metropolis’s over 1800 shots, I counted only 26 expository titles and 156 dialogue titles—in a film running nearly 2 ½ hours. Lang plunges us into each scene with no fuss, and once we’re there, a smooth continuity carries us from shot to shot. Confronting the seven deadly sins in the cathedral, Freder turns away, twisting Georgy’s cap in his hands as he exits the frame.

Cut to the main area of the cathedral, and Freder is still twisting the cap as he enters the frame. (Like other shots from the Argentine version, this is slightly reduced because of the 16mm source.)

He lifts the cap, and we get his point of view on Georgy’s name and number.

Cut to the Yoshiwara nightclub closing, as Georgy steps groggily into the street.

Here the new footage lets us see that Lang is exploiting the sort of verbal and imagistic hooks he had developed in earlier films: from Georgy’s cap to Georgy himself, with no need of an intertitle to take us to the new scene.

Lang’s freedom of camera position is typical of late silent cinema, but he deploys his angles with characteristic precision. As usual in Europe, Hollywood-style continuity isn’t completely adhered to—there are some crossings of the 180-degree line—but Lang is careful to keep us oriented to the action through eyelines. This allows great flexibility in camera placement.

Fredersen is dictating to his secretaries while Josaphat is monitoring prices. A vast establishing shot shows all of them.

Fredersen’s pacing around his office allows Lang to introduce a new area around the window and the desk.

Now pacing in the center of the office, Fredersen pauses in his dictation and Freder bursts in behind him.

But Fredersen, who’s already holding up one hand as he speaks, simply twists his wrist, and this silences his son.

The shot approximates Freder’s point of view, but Lang gets a bonus from it. The sharp change of angle makes the imperious hand (and not, say, Fredersen’s expression) the compositional focus of the shot. In fact, this sort of hovering hand will become part of the characterization of Fredersen, and Lang will stress it through, once more, energetic changes of angle.

And still later, the framing will spotlight Freder’s pointing finger by pushing it to one zone on the far right of the shot.

Lang’s concise handling of such small actions forms a delicate counterbalance to the mass movements elsewhere in the film. Perhaps for him, both gestures and crowd scenes are merely two ways of creating a geometry that can activate every area of the screen.

The carefully controlled freedom of spatial construction is facilitated by one of Lang’s favorite tactics: shooting from directly on the axis of character interaction. (No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent this.) Lang in effect sets the camera between the two characters so that they stare out at us, as if mesmerized. The technique is most memorable in the scene in which Freder is confronted by Maria and the children.

Again, though, the Argentine material brings more instances to our attention.

Putting the camera on the axis allows Lang leeway in changing his angles. From a shot on the center line, you can cut to pretty much any other area of space.

Lang’s crisp visual narration comes to a climax in the well-named Furioso section. As the action ramps up, the characters rush from spot to spot, hurling themselves into the frame and then abruptly halting to hold the composition.

The extreme case is the robot Maria, whose head and limbs jerk puppetlike from one position to another.

In all, Lang’s precise, almost diagrammatic visual style rushes us through the film’s wild plot and dazzling architecture. An emblem of precision in the service of slightly demented material might be that memorable close-up of the robot Maria: One eye staring out normally, the other half-closed, and the mouth half-twisted in a leer, as if the circuitry in the skull was failing.

A little encyclopedia

Martin Kroeber, Togichi Akira, Winnie Fu, Sam Ho, and Wong Ain-ling discuss preservation and restoration at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

In a Q & A after the screening, Martin Koerber and Frank Strobel shared information about the version. They and their colleague Anke Wilkening could publish a whole book about the restoration, but here are some highlights, drawn as well from Martin’s comments at a lengthy seminar at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

*Sources for information about the premiere version include a copy of the script (helpfully marked with reel ends and calculations about running time), censorship cards recording the credits and intertitles reel by reel, Gottfried Huppertz’s musical score, and thousands of production stills.

*Using these materials, earlier researchers were able to create a sort of mosaic of the version that premiered in Berlin in January 1927. The resulting study film embedded long swathes of blank footage as place-holders. The fact that the Argentine shots fitted in neatly proved the validity of that edition. This study film may be ordered on DVD at nominal cost by educational and research institutions.

*What’s still missing? Some shots in the Argentine version may have been censored; we’re missing a bit in which Georgy, at liberty in a cab, sees a woman baring her body. Also lacking is nearly all the fight between Rotwang and Fredersen, which enables Maria’s escape. In addition, the Argentine print lacks a scene showing a monk preaching in the cathedral, which yields some apocalyptic images.

*If the film plays fast for contemporary tastes, don’t blame the restorers. This version runs at 24 frames per second. Actually, for the 1927 premiere the film was run even faster. The score includes passages accompanying missing footage as well as over a thousand synch-points for specific onscreen action. On the basis of this evidence, it seems that the film was designed to run at about 28 frames per second. This reminds us that silent-film running speeds were far from standardized, and they sometimes exceeded the 24 fps that would be established for sound film. (For more on this matter, go here and scroll down a bit.) In addition, Frank mentioned that in theatres with orchestras, the conductor could regulate the speed of the film with a dial set into the podium.

*Why insert the cropped 16mm footage in such obvious fashion? Couldn’t the framelines be adjusted to match the surrounding 35mm material? Yes, but this slight blowup of the footage would falsify the shot scale of the original footage and not match comparable shots in the 35mm footage. Moreover, Martin pointed out that because not all the scratches and fuzziness of the 16mm material could be purged, it’s better to let these stand stand out somewhat as evidence of the vagaries of film history–like leaving some damage visible in historic buildings.

*Why is the restoration in black and white, since most silent film restorations are in color? Lang was opposed to tinting and toning, so Metropolis premiered in black and white. This caused a debate among critics, some of whom considered it a promising departure from contemporary practices of coloring scenes. The tinted versions that one can occasionally see are likely export versions colored at the request of distributors in particular markets.

*Although future screenings of the 2010 version are to be accompanied by other ensembles devising their own music, there’s a powerful case for retaining Huppertz’s original score. It reflects the filmmakers’ intentions, and its Wagnerian romanticism and modern rhythms are enjoyable simply as music. Just as important, Huppertz designed his score around leitmotifs that, as in opera, can call to mind characters who aren’t onscreen at the moment.

*Metropolis, Martin argued, is too often considered simply a late Expressionist film or an early science-fiction effort. Now we can see that it’s much more: “a compendium of everything in the air in 1927 Germany.” It brings together political ideas, debates about class society and urban life, current trends in the fine arts, acting styles, and cinematic experiments. It owes a great deal to the “monumental” films of the late 1910s, such as Joe May’s Herrin der Welt (1919), but it’s also a synthesis of what filmmaking had become since then. “It’s a little encyclopedia of 1927 cinema. . . . There’s something in it for everybody.”

To see the restoration with the stirring score, vigorously conducted by Frank, was a high point of my Hong Kong trip and indeed of my filmgoing year.

This version of Metropolis was simulcast, if that’s the right word, on 12 February by Arte during the premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival. My frames are taken from that broadcast version; hence the bug. The restoration will be screened on Turner Classic Movies in the fall, and then released on DVD in the US by Kino International.

The epigraph quotation from Arnheim comes from Film Essays and Criticism, trans. Brenda Benthien (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 119. The article about the US cut of the film, which became widely seen around the world, is Randolph Bartlett, “German Film Revision Upheld as Needed Here,” New York Times (13 March 1927), X3.

Thanks to Martin Koerber for an abundance of information. For further reading, he recommends Erich Kettelhut’s memoirs on designing and filming the project, Der Schatten des Architekten (Munich: Belleville, 2009), ed. Werner Sudendorf, with many documents from sketches and photos; and the Deutschen Kinemathek exhibition catalogue, Fritz Langs Metropolis, ed. Franziska Latell and Werner Sudendorf (Munich: Belleville, 2010). You can get a sense of the tangled history of the versions of the film from Martin’s article in the latter volume, which includes a detailed account of the digital restoration. An earlier version of his piece, keyed to the 2001 version, is available as “Notes on the Proliferation of Metropolis,” in Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002), 128-137. The Metropolis exhibition runs through 25 April.

A special thanks to Lee Tsiantis, Langian extraordinaire.

“I am not Carl Dreyer, and I should shut up”

Kristin here:

So says director Guillermo del Toro in his self-deprecating lead-in to his audio commentary on the great Danish filmmaker’s 1932 classic, Vampyr. Fortunately he did not act on his words but goes on to give an erudite, often personal series of insights into the film.

Owners of the Criterion boxed-set edition of Vampyr (2008) may be wondering if their memories are playing them tricks, since its audio commentary was done by our good friend Tony Rayns. Tony’s comments are on the Eureka! edition of the film (also 2008), too, but the British label got del Toro to sit down and record an exclusive second commentary. British websites reviewed the disc, but I suspect that many film fans in other countries are not aware of the existence of del Toro’s commentary.

Early in that commentary, the modest, humorous tone continues, as del Toro says his remarks are “The equivalent of inviting a fat Mexican to your house and feeding him, and then you have to listen, for mercifully a short time, and then disagree, agree, insult, or share any of my opinions.”

From that point on, though, del Toro gets serious. He has worked in the vampire genre himself. His first feature, Cronos, is a vampire tale of sorts, and in June he and co-author Chuck Hogan released The Strain, the first novel of a trilogy that treats vampirism as a fast-spreading virus. Beyond these works, however, del Toro knows an enormous amount about the history of the vampire genre.

For the most part, his comments don’t follow the action on the screen. He begins with a lengthy disquisition on the skull imagery and its creation of a memento mori motif. At times the subject under discussion syncs up briefly with the unfolding narrative. As the protagonist, Allan Gray, watches reflections in a pond that have no visible cause, del Toro discusses the nature of Dreyer’s take on the genre:

In strict terms, it is perhaps one of the few vampire films that have actually gone to the root of the mythos and made the vampire a spirit, not a physical creature. Most of the time you get a living corpse . . . And in the oldest European tradition, in the most antique manuscripts in Eastern Europe and Greek manuscripts about vampirism and so forth, in reality it is a spiritual infection. The vampire is a hungry spirit that will drain the living and will of choice materialize partially and selectively if it needs it, if it serves him so. But essentially a vampire is a shadow and the father or the mother of shadows. It is this hungry shadow that haunts the living and drains them.

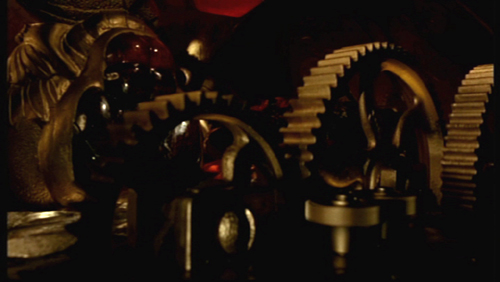

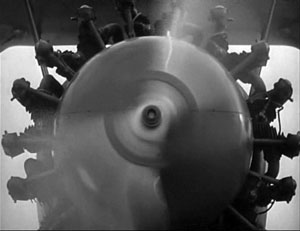

Del Toro clearly loves Vampyr and stresses its influence on him. Seeing Gray as a Christ figure, he named the protagonist of Cronos Jesus Gris (Spanish for “gray”) as an homage. He copied the cracked gravestone of the vampire in Hellboy. In discussing the shots of the gears of the milling machine that kills the villainous doctor at the end of Vampyr (above), he remarks, “I have myself tried to reproduce the beauty of those gears, incessantly and not very fruitfully I may add, but I try for sure.” (See below.)

Del Toro also remarks that there is no reason that characters in vampire stories—or other kinds of stories—must be nuanced. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences may prefer to reward actors who play complex characters. Still, he sees no reason why in Vampyr the doctor needs to be anything other than evil, the hero anything other than spiritually pure.

Del Toro refuses to try and interpret the film’s symbolism, saying that decoded symbols become “ciphers.” He continues:

It is foolish to try to decode the symbols in Vampyr. It is important to understand the rhythm and the repetition of them. And it is important to try and talk about them in the most general sense, but one should not foolishly try to assign specific value to them, because in doing that you would asphyxiate the poem, you would asphyxiate the film.

There is relatively little discussion of film style, but at about 49 minutes in del Toro talks about camera movement and how it creates mood rather than strictly serving the narrative. He challenges his auditors to examine films shot at the same time (in 1931-32) and find three or four other films that were experimenting with camerawork in this way. He even gives one of his email addresses so people can write and give him lists of titles that might contradict him. (With The Hobbit script in progress and pre-production already begun, I suspect that del Toro is not checking that particular address—which he reserves for fans—as often as he used to.)

There are other interesting points, as when del Toro suggests that Dreyer was influenced by Un chien andalou. Not that he created a surrealist vampire film but that he felt freed from the necessity to follow a narrative closely. To del Toro, the underlying plot of the film is simple and easily comprehensible, leaving Dreyer free to devote much of his film to a more poetic, evocative style.

The Criterion and Eureka! versions share several of the same supplements, including a 1966 documentary on Dreyer’s career, a “visual essay” by Casper Tybjerg on Vampyr, as well as the original Sheridan Le Fanu story on which the film was loosely based (in pdf form on the disc in the Eureka! version and in a booklet also containing the original screenplay in the Criterion one), and improved English translations. Criterion has included a 1958 radio broadcast of Dreyer reading an essay on filmmaking, while Eureka! provides two deleted scenes that were removed by the German censor before the film’s premiere. These scenes are not entirely unfamiliar, since they remained in the French version. The Criterion rendering of the film seems to have boosted the contrast, perhaps too much. The Eureka! version’s gray, misty visuals look more like those that I’m familiar with from reasonably good 35mm copies.

For a detailed comparison of these two releases and the older Image edition (1998), see DVD Beaver. For a review of the Eureka! disc, supplement by supplement, see DVD Outsider.

As with other Eureka! DVDs, this one is region 2 coded.

Cronos

Daisies in the crevices

DB here:

If you wanted a prototype of some unique visual pleasures of 1930s cinema, you could do worse than pick this innocuous image. It’s perfunctory in narrative terms, merely telling us that Sylvia Day is calling on Bill Smith. Beyond its plot function, though, it’s fun to see. We can enjoy the unfussy modern edge of the doorjamb, the curve of the manicured thumb, and soft highlights bringing out the hand and knuckles.

Above all, there is that starry gleam at the top of the doorbell. Who needs it? It’s just a doorbell. Why take so much trouble lighting a throwaway shot?

Add to this that Parole Girl (1933) is a program picture, and from Columbia, no less—the Poverty Row studio that had yet to break through with It Happened One Night (1934). We learn from Bernard F. Dick’s deeply-researched book on Harry Cohn that the budget for Parole Girl would have been about $250,000, when MGM B’s were running about $400,000. Why spend money on a shot like this?

Because that was the standard of good-looking moviemaking at the time. Most problems of converting to talkies had been solved, so films were regaining not only the fluent narration but the sparkling imagery of 1920s cinema. Under Cohn’s leadership, Columbia was trying to compete with the bigger studios’ movies, and looking classy was one way to do it. Recently I spent a day or so watching four titles, and I was reminded how pictorially sophisticated and refreshing low-end Hollywood can be. These movies also offer us an unusual window into what was already characteristic storytelling strategies of classical Hollywood. But there will be spoilers ahead too.

Welcome to 1933

As so often, I have TCM to thank. Since their Jean Arthur tribute of 2007, they have been running a generous number of Columbia titles (all restored by the master hand of Grover Crisp). By including less-known 1930s items along with classics like The Awful Truth and the Capra titles, they continue their mission of serving American film culture every hour.

Lea Jacobs has convinced me that it’s useful to think of studio releases in those days as filling a season running from Labor Day to Memorial Day rather than a calendar year. Studio heads planned budgets and production schedules according to that time frame, like network TV broadcasters now. Unlike today, summer was not a big release period, maybe because of the competition of other leisure activities, maybe because with air-conditioned movie houses people would come watch anything thrown on the screen. In any case, the big pictures were saved for fall, winter, and spring.

So my frame of reference is the 1932-33 season. Columbia ushered in the new year with its best-remembered film of the season, Capra’s Bitter Tea of General Yen (6 January). The studio probably considered Washington Merry-Go-Round (15 October), Virtue (25 October), and No More Orchids (15 November) to be A projects, but the large output of Westerns, the absence of historical pictures, and the relative dearth of stars in this output confirm the studio’s status as a Poverty Row company.

My movies come from the winter and spring of 1933. Each was shot in two to three weeks and each runs about seventy minutes.

Air Hostess (15 January, directed by Albert Rogell) tells of the daughter of a WWI ace who marries a reckless young pilot. Trying to build a new type of plane, he shops his business plans to a rich woman investor, who tries to seduce him.

In Child of Manhattan (4 February, directed by Edward Buzzell), a wealthy widower falls for a taxi dancer and takes her as his mistress. When she becomes pregnant, he marries her. But the baby dies soon after birth and the wife flees to Mexico for a divorce while the husband tries to track her down.

In Parole Girl (4 March, directed by Edward Cline), a department store executive sends a woman con artist to prison. She vows revenge. When she gets out, she seduces the executive, although he’s unaware of who she is.

Ann Carver’s Profession (26 May 1933, directed by Buzzell) centers on a couple torn by career rivalry. After being a gridiron hero in college, the husband is failing as an architect. Meanwhile, his wife is becoming a celebrated trial lawyer. Eventually the husband leaves the household and takes up with a floozie, who winds up strangled. His wife must defend him against the murder charge.

For connoisseurs of naughty pre-Code movies, there are the usual attractions of double beds, extramarital sex, peekaboo negligees, and risqué dialogue. Child of Manhattan goes the farthest, perhaps because it’s an adaptation of a Preston Sturges play. “You’re a fascinating little witch,” says the millionaire. “Did you say witch?” the dancer asks. This is the same girl, played by perky Nancy Carroll, who thinks the man is trying to feel her up when he slips a thousand-dollar bill into her garter. Later she recalls her mother’s advice: “Never, ever walk upstairs in front of a gentleman.” And when she confesses to her Texan admirer in her mangled pronunciation, “I’m a courtesian,” he pauses and replies, “Well, religion doesn’t make any difference with me.”

Despite such pleasant moments, and two screenplays credited to Robert Riskin and Norman Krasna, these movies won’t win prizes for imaginative scripting. The tone is often uncertain, with comic banter clashing with scenes of melodramatic sacrifice. The long arm of coincidence becomes elastic. In Parole Girl, the heroine happens to meet the offending executive’s first wife in prison. During the taxi dancer’s stay in Mexico, she runs into the cowpoke who had wooed her aggressively in Manhattan. In Ann Carver’s Profession, the husband’s girlfriend accidentally strangles herself. Yes, you read that correctly.

Still, you have to give points for speed. Only Parole Girl has unusually quick cutting, at an average of 6.6 seconds per shot, but the overall pace of most of the plots is pretty rapid. (The exception is Child of Manhattan, whose lumbering dramatic rhythm is echoed in an average shot length of sixteen seconds.) Playing far-fetched action fast makes it less noticeable and more forgivable. Today any movie that can tell a moderately interesting story in a little more than an hour feels like a triumph. You can watch two of my pictures in the time it takes to groan your way through Funny People. And in these movies, the opening credits flash by in less than fifty seconds. Those were the days when crafts people under contract didn’t have to be acknowledged, and there were no executive producers.

Apart from Capra, whom do we remember as a Columbia director? Probably not my three guys. Albert Rogell, director of Air Hostess, began directing in the early 20s and worked for Columbia, Tiffany, Monogram, RKO, Universal, and Paramount. A prototypical B filmmaker, he signed over a hundred films in twenty-five years. Edward Buzzell was somewhat more prominent. After Ann Carver’s Profession, he left Columbia for Universal and eventually moved to MGM, where he directed (as if that were possible) the Marx Brothers in At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940), as well as helming Song of the Thin Man (1947). Like Rogell, Edward Cline (Parole Girl) skipped among studios; like Buzzell, he landed on his feet with comedian comedy, steering W. C. Fields through You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man (1939), My Little Chickadee (1940), and other vehicles. In all, studio artisans, yes; auteurs, no.

Two Joes and a Ted

Parole Girl

If you’re interested in how Hollywood tells its tales, there’s a fair amount to chew on in these modest releases. The scripts tend to obey Kristin’s four-part model, adapted to very short running times, with the key turning point taking place midway through the film. Despite the coincidences, the characters’ goals and changes of heart tend to be planted early. In Ann Carver’s Profession, Ann’s intense ambition and Bill’s swaggering overconfidence prepare us for the crisis in their marriage, when each is unwilling to compromise.

As for performances, perhaps the very speed of production forced actors to play naturally. True, Fay Wray is a bit arch as Ann Carver, but Gene Raymond as her husband moves convincingly from boisterousness to self-doubt. In Child of Manhattan, John Boles, trying to mingle with the little people, can be stiff, but Nancy Carroll has pep, and Buck Jones as her cowboy swain adds a welcome dose of naive gallantry. All three show how important distinct voices had already become: Boles mellifluous, Carroll up and down the scale, Jones slow and sincere. Reliable Columbia regular Ralph Bellamy shows up in Parole Girl, but more memorable is the performance, or rather presence, of Mae Clark. When she comes back from prison bent on vengeance, she’s a glowering figure in her stylishly chopped hairdo.

As for performances, perhaps the very speed of production forced actors to play naturally. True, Fay Wray is a bit arch as Ann Carver, but Gene Raymond as her husband moves convincingly from boisterousness to self-doubt. In Child of Manhattan, John Boles, trying to mingle with the little people, can be stiff, but Nancy Carroll has pep, and Buck Jones as her cowboy swain adds a welcome dose of naive gallantry. All three show how important distinct voices had already become: Boles mellifluous, Carroll up and down the scale, Jones slow and sincere. Reliable Columbia regular Ralph Bellamy shows up in Parole Girl, but more memorable is the performance, or rather presence, of Mae Clark. When she comes back from prison bent on vengeance, she’s a glowering figure in her stylishly chopped hairdo.

The films make fluent use of storytelling devices that predate the 1930s but are forever associated with that decade. Sequences are linked through headline montages and wipes, recently made possible by the optical printer. There are more elaborate techniques too, particular the visual or auditory hook connecting scenes. We’re not surprised to see commonplace instances, as when a note pad listing an apartment number dissolves to that number on the door. In Air Hostess, however, a spinning propeller gives way to a roulette wheel, and this association does a little more work, linking Ted Hunter’s reckless flying to his gambling and his general tendency to take risks.

In Child of Manhattan, as Madeleine resolves to leave her husband after the death of her child, she tearfully shakes a baby rattle, and this dissolves to marimbas in a nightclub, swiftly turning her pathos into her effort to start a new life with a Mexican divorce.

But what is perhaps most striking about these films is their photography. Ten minutes into Air Hostess, the first one I watched, we get a lovely sustained track into a sunny airfield, our view guided by the walkway wheeled up to a plane door as passengers step out.

The relaxed play of light and shadow in this geometrical shot yields one of those fugitive visual delights that classic cinema so often supplies.

What’s it doing in a Columbia programmer? This Poverty Row studio realized that they could give their pinched budgets an upscale look with polished cinematography. Accordingly, you can argue that the biggest talents on the Columbia lot were the directors of photography. Our four films were shot by ace DP’s.

Joe August (Parole Girl) was the grand old man. He filmed some of the best-looking hits of the 1910s, including Ince’s Civilization (1916) and a great many William S. Hart movies (including Hell’s Hinges, 1916). In the 1920s and up to 1932 he worked at Fox on films by Ford, Hawks, and Milestone. At Columbia August would shoot Borzage projects like Man’s Castle (1933) before moving to RKO for Sylvia Scarlett (1936), Dance, Girl, Dance (1940), and the flamboyant All That Money Can Buy (aka The Devil and Daniel Webster, 1940).

Another Joe, somewhat younger, was no less gifted. Joseph Walker, the DP of Air Hostess came to Columbia early and soon teamed with Capra; he would shoot twenty movies with the director, including the splendid American Madness (1932), a particular favorite of mine. Walker stayed loyal to Columbia, shooting Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), Penny Serenade (1941), and on and on—returning to Capra for the independent production It’s a Wonderful Life (1947). Walker also patented an original zoom-lens design.

Ted, sometimes known as Teddy, Tetzlaff was another Columbia loyalist, and he certainly cranked them out. Hawks’ The Criminal Code was one of eleven movies Tetzlaff was credited with in calendar 1931. But by the spring of 1933 he seems already to have become a free lance, eventually working at Paramount on a string of classics (Easy Living, Remember the Night, Road to Zanzibar), then RKO (The Enchanted Cottage, Notorious), and occasional jobs back at Columbia. Tetzlaff became a director as well, remembered chiefly for the cult classic The Window (1949).

No wonder my four films dazzle, even on TV. According to Bob Thomas’s biography King Cohn, Columbia took special care to create a phosphorescent look through careful processing that enhanced the DPs’ efforts. Hence not only the sparkle on a door buzzer but glowing applications of then-standard edge lighting. Hence as well the use of striped shadows to suggest venetian blinds, a convention we associate with the forties but here in precise array (Child of Manhattan, Parole Girl).

Trust Joe Walker to provide a little of that striped texture with a fuselage.

Hence too some striking depth. Here is the next-to-last shot of Walker’s work in Air Hostess, the sort of fancy aperture composition that crops up surprisingly often in the 1930s.

Tetzlaff, first in Child of Manhattan and then Ann Carver’s Profession, seems to be fooling around with faces and elbows.

Probably the most visually and narratively complex of my films from spring 1933 is Ann Carver’s Profession. It’s possible that it was Columbia’s equivalent of an A production: Gene Raymond was a mid-range star known for a few Paramount and MGM pictures, and Fay Wray’s King Kong had premiered a week before filming started. Whatever the cause, Ann Carver has more complex plotting and more consistently inventive visuals than the three other titles.

From the very start, when gridiron hero Bill promises to provide for Ann the waitress, we get the sort of offhand flash that I like in 1930s movies. As Bill follows Ann into the kitchen, she’s framed in a swinging door and the camera moves closer to pick up their clinch.

Once they’re married, the circle has become a rectangle, and trouble is on the way.

There are fancy mirror shots, pov constructions that lead characters to the wrong inferences, and examples of the big-foreground compositions that would come to prominence in the 1940s.

The trial recesses; crane up to the clock; spin the hands to cover a couple of hours; crane back to the trial resuming. Or start with Bill’s girlfriend, passed out and garroted by the necklace that has snagged on a leering chair carving. Dissolve to Bill’s night on the town, before ending that fuzzy montage with a dissolve back to the chair carving.

Bill didn’t kill her, but the pictorial logic makes him almost magically responsible, with the carving mocking him for what’s to come.

Above all there is one of the most laconic (and cheaply filmed) courtroom montages I’ve ever seen. A string of witnesses testifies, and after a newspaper pops out the first one, we get a fusillade of extreme close-ups, cut very quickly.

Just as striking is the coordinated sound montage, which reduces the testimony to clipped sentences, then phrases (“”Four-thirty!” “Quarter to five!” “Both of ‘em!”), then single words (“Drunk!” “Drunk!” “Strangulation!”), all damning Bill. Why take us through all the rigamarole—people sworn in and questioned at length—when you can give the essence of it in twenty-eight shots and twenty-five seconds?

My 1933 quartet contains no great film; perhaps none is worth more than one viewing. But what I learned from watching ordinary movies for our Classical Hollywood Cinema book is borne out by my soundings here. We can enjoy seeing a well-honed system steering us through a story, especially when gifted people like Teddy and the two Joes are shifting the gears. We can appreciate the opportunities for grace notes in what some call formula filmmaking. And we can see that this lowly studio, making films ignored in traditional histories, has something to teach filmmakers today: proud modesty. A film can radiate pride in being concise, in exercising a craft, and in telling a story that hurtles forward while shedding moments of casual beauty.

Most critical writing on early 1930s Columbia pictures focuses on Frank Capra, but there is good general background in Bernard F. Dick, The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row: Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009). My mention of budget levels comes from his discussion on pp. 119-120. An older, citation-free but still helpful biography is Bob Thomas, King Cohn (Beverly Hills: New Millennium, 2000). In-depth information on Joseph Walker as a Columbia cinematographer is available in Joseph McBride’s excellent biography Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 189-215. Walker’s engaging autobiography supplies nothing specific to these films, but he sprinkles technical information among its anecdotes. See Joseph Walker and Juanita Walker, The Light on Her Face (Los Angeles: ASC Press, 1984).

On 1934 as the end of naughtiness, see Tom Doherty’s Pre-Code Hollywood. For a skeptical account of the idea of Hollywood “before the Code,” see Richard Maltby, “More Sinned Against than Sinning [2003],” in Senses of Cinema here, and essays in “Rethinking the Production Code,” a special issue of The Quarterly Review of Film and Video 15, 4 (1995), ed. Lea Jacobs and Richard Maltby.

If you’re interested in more complicated narrative strategies in films of this period, try our entry “Grandmaster Flashback.” For another take on low-budget 1930s films, there’s our entry on Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan.

(50) Days of summer (movies), Part 2

DB here:

How I spent part of my summer vacation: notes on three more films.

Gangbusters

Two major directors–one an emblem of goofy bravado, the other emerging as a contemporary master–gave us movies this summer, and both let me down. I have cautiously championed Tony Scott’s recent work because at least he’s willing to go all the way, however misguided the direction. From Spy Games on, he has stuck to the credo that too much is never enough. His technique is swaggering and undisciplined, mannered to the nth degree. Yet I find his fevered visuals more genuinely arresting than the safe noodlings of most of today’s mainstream cinema. Man on Fire and Déja Vu reheat their genre leftovers into something spicy, if not nourishing, while Domino, the cinematic equivalent of hophead graffiti, wraps its sleazy characters in a visual design apparently inspired by the glowing interior of a peepshow booth.

So it’s with a chagrin that I report that The Taking of Pelham 123 is utterly square. The violence isn’t reveled in, the color scheme isn’t garish, the story has a florid villain played by scenery-masticating Travolta, and Denzel Washington has never seemed more passive and drab. In Scott’s DVD commentaries, he insists that art-school training led him to approach cinema with a painterly eye. But this project has the feel of a commissioned magazine illustration, not the delirious wall-size outrage that he could make if given his head.

I’ve respected Michael Mann since I saw Thief on its initial run. Heat seems to me on the whole his best work, though I admire many qualities of Manhunter, The Last of the Mohicans, The Insider, and Collateral. Ali and Miami Vice seem to me lesser achievements, and with Public Enemies he has gone somewhere I can’t follow.

I found it a surprisingly flat exercise, skimming over familiar territory–the charming bandit vs. the square-jawed cop, the struggle of the freebooter vs. the mob, the cynical politics of law enforcement vs. the authentic impulses of the outlaw. The plot is unusually straightforward for Mann, and the last shot, which ought to be a corker, is wasted. Too many scenes are nakedly expository, relying on fussy period detail to carry them. At the same time, more basic exposition seemed to me botched at the outset. In the opening scene, shouldn’t we get a clearer sense of what Dillinger’s sidekicks look and act like? A classically constructed film would dwell on them, characterize them, give them bits of behavior that develop in the course of the film. Mann treats them as part of the scenery setting off his handsome hero. Later, when one of Dillinger’s hired pistoleros goes kill-crazy, shouldn’t we have been set up to see him as a possible risk?

Typically Mann romanticizes, even sentimentalizes, his hard cases in that tough-guy way we know from fiction. But I couldn’t discern any vivid attitude toward his parallel protagonists Dillinger and Purvis. After Heat, where crook and cop both show a willingness to abandon women who want them, it’s probably significant that Dillinger is characterized by his fidelity to Billie. Yet while she’s in jail he’s back to an insouciant night on the town with his familiar floozies. In all, I can’t figure out why Mann made this movie about these people, or why we should care.

Collateral was already veering toward a certain obviousness of construction, when Vincent talks initially about how in impersonal L. A. a dead guy can ride the subway without anyone noticing. In Public Enemies the final line returns to the film’s most underscored motif in a distressingly on-the-nose way. Similarly, one thing I admire about Heat is that it acts as if no other gangster movie has ever been made. Its scenes offer plenty of opportunities for cute citations of old crime movies, especially when Vincent (a different Vincent) catches his wife’s lover watching TV. Instead, Mann treats the material as cut off from cinema, and this saves him from the coyness of so much genre work today.

Is he then a realist? His interviews and DVD commentaries indicate that he thinks of himself this way. Yet he strikes me instead as a genre purist. Each film is sui generis because it aims to recover the authentic dramatic core of the policier, the social comment film, or the wilderness adventure. But in Public Enemies, Dillinger’s visit to the movie house to watch Manhattan Melodrama (1934), even though the event is historically accurate, hits the parallel chords hard. Dillinger, who’s about to be cut down in a few moments, smiles in fascination when Gable says: “Die the way you lived–all of a sudden.” In such scenes, Mann seems to me to have retreated into being a more ordinary filmmaker. The worst thing I can say about Public Enemies is that it risks becoming academic.

Mann’s claims to realism are partly his efforts to deny being a self-conscious stylist. For many of his admirers, me included, his pictorial sense is a large part of what makes his work distinctive. There’s plenty of controversy about the look of Public Enemies, and I have to come down on the side of the nay-sayers. I saw it twice, once in 2K digital projection in a superb multiplex in Europe. My second viewing was on 35mm, in a reliable Madison, Wisconsin venue. The digital version too often teemed with artifacts, blown-out bright areas, and disconcerting shifts in tonal values within scenes. The next two images are successive shots in the HD trailer, and I haven’t adjusted them. The disparities between them reflect the sort of mismatches that struck me in the digital screening.

On film, the faces lost the edge enhancement and the mushy textures I saw in the digital version, and the tommygun fire was less tinged with yellow, pink, and orange. On the whole, I thought that the images benefited from the mercies of emulsion.

The chance to take high-definition video all the way, especially in low-light situations, seems to have invigorated Mann creatively, but it may have distracted him from basic craft. Investing wholly in a new look, he belabors even the simplest action through staccato cutting; getting people in and out of cars should not take such effort. Action scenes occasionally succumb to the jittery camera. I consider the climactic bank robbery in Heat somewhat awkwardly staged (though the dazzling sound work there compensates somewhat), and similar short-cuts can be found in the Wisconsin shootout here.

If you find my tone tentative, you’re right. I didn’t care for The Insider on first viewing; it took me a second visit to grasp what I now take as its virtues. That’s why I saw Public Enemies twice. I expect as well that Mann’s eloquent defenders, such as Matt Zoller Seitz, who has done a passionate series of shorts on Mann, will find fault with my evaluation. For the film’s admirers, what I find sketchily indicated they could see as daringly elliptical; what I see as inconsistent they might consider calculatedly ambiguous. The incompatibilities of color and light could be part of Mann’s experimentation too. I see his oeuvre as largely updating cinematic classicism, while others tend to see it as a daring leap beyond it. Maybe I’ll come around eventually. For now, I have to consider Public Enemies the biggest disappointment of my fifty days.

A welcome basterdization

It’s a measure of the changes wrought by the Internets that Inglourious Basterds has in about a month amassed a daunting volume of serious commentary. Without benefit of DVD (let’s be charitable and assume no BitTorrenting), dozens of online writers have dug deep into this movie. As if to demonstrate the virtues of crowdsourcing, this flurry of critical discussion has shown that most professional movie reviewers have tired ideas, know little about film history, and are constrained by the physical format and looming deadlines of print publication. At this point, I’m very glad I’m not writing a book on Tarantino; the sort of secondary sources that normally take years to accrete have piled up in a few weeks, and the pile can only grow bigger, faster.

So what is there left for me to say? A little, though I can’t be sure every point isn’t made somewhere else. In any case, surely you’ve seen it, so I don’t have to warn you about spoilers, do I?

Since I thought Death Proof offered merely proof of the director’s creative death, I went to Inglourious Basterds with low expectations. I came out thinking that it was the most audacious and ambitious American movie I saw in my fifty days of summer viewing.

To deal with the current controversy immediately: I didn’t think its counter-history was intrinsically offensive or immoral, since I remembered those what-if-Germany-had-won counterfactuals in Deighton’s novel SS-GB and Brownlow’s film It Happened Here (1966). Did those express defeatism or an inability to counter the Nazi threat? So why not have a band of vindictive Jews seeking to match the Nazis in ruthlessness (except that their targets, so far as we see, are only soldiers and collaborationists)? We call it fiction.

You can quarrel about whether a revenge plot should carry some signals of the cost to the avenger, but I’m sufficiently convinced that tit-for-tat is embedded in human nature and will always be perceived, however recklessly, as virtuous. In any case, the movie’s emblem of revenge, the powerful image of Shosanna laughing mockingly as she goes up in flames along with the audience, carries the strategic ambiguity of a lot of cunning popular art. It’s at once a glorying in payback, a Jeanne d’Arc martyrdom, and a reminder of the fate of Jews elsewhere at that moment. It doesn’t permit a single easy reading.

Granted, there are some low-jinks, like the misspelled title and heroine’s name; are these jokes on Tarantino’s notorious spelling malfunctions? Yet the movie seemed to me Tarantino’s most mature (to use a term of praise that he hates) since Jackie Brown. I say that not because his other work is juvenile, which it’s not (except for Death Proof). I call Inglourious Basterds mature because it exploits his strengths in fresh but recognizable ways.

First, strengths of structure. Tarantino’s conception of storytelling owes at least as much to popular literature, particularly policiers, as it does to current conventions of screenwriting.

Take his penchant for repeating scenes from different viewpoints. In Elmore Leonard’s novel Get Shorty, Chapter 2 ends with Harry, seeing Chili at his desk, exclaiming, “Jesus Christ!” Chapter 3 consists of the first stretch of their conversation. Chapter 4 starts with Karen approaching Harry’s office and hearing him say, “Jesus Christ!” This overlapping-scene strategy, sketched in Reservoir Dogs, gets elaborated in Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown.

Likewise, thrillers and crime novels commonly play on showing how distant lines of action unexpectedly intersect. In Peter Abrahams’ Hard Rain the agent who becomes the hero tells the story of two coal miners, Bazak and Vaclav, who meet after tunneling from two ends of the field. Needless to say, Hard Rain’s own plot enacts the same pattern. Charles Willeford’s chance-driven, parallel-action novel Sideswipe could be a model for the structure of Pulp Fiction. So it should be no surprise that Inglourious Basterds, labeling its long sequences “chapters,” should rely on the stepwise convergence of Shosanna’s plotline and the Basterds’ guerrilla operations, with the UK Operation Kino serving as the first sign of a merger.

So the film is built on large-scale alternation of the principal forces: Shosanna (Chapter 1), the Basterds (2), Shosanna again (3), the Basterds again (4), and finally the two strands knotting at the screening of National Pride (5). Landa also knits the two strands together, of course, starting when he investigates the tavern shootout at the end of (4). In Chapter 5 the alternation gets carried by classic crosscutting. We shift to and fro among Shosanna’s plot, the capture of Raine and Utivich, the conflagration in the auditorium, and the deal struck between Landa and the US command. Yet right to the end both Shosanna and the Basterds have no awareness of each other’s plan: only we grasp the double dose of Jewish vengeance. More than in most films, but typical for Tarantino, we’re aware of the plot’s abstract architecture.

Then there are strengths of texture—the moment-by-moment unfolding of the action. Again pulp fiction offers some models.

In Get Shorty, Leonard develops the scene I mentioned above in an extraordinary way. Chili, Harry, and Karen talk through the night about Chili’s purpose and about the ways of the movie industry. Their conversation runs for a remarkable seven chapters and sixty pages, interrupted only by a brief flashback. When I met Leonard at a book-signing event, I asked him why he took up a fifth of the novel with a single scene. He said that he hadn’t realized it consumed so much space, because it was “fun to write.”

Tarantino can lay bare his chapter-block architecture because his scenes are devoted to this sort of prolongation. You may remember the bursts of violence, but what he fashions most lovingly is buildup. Here the spirit of Leone hovers over our director. In each entry of the Dollars trilogy, you can see the rituals of the Western getting more and more stretched out, filled with microscopic gestures and eye-flicks. Eastwood’s lips stick slightly together and must peel apart when he speaks: This becomes a major event. I’m a primary-document witness to the fact that 1969 cinephiles were stunned by the long opening scene of Once Upon a Time in the West, which after painstakingly establishing the tics of several characters ends by eliminating them. Later, John Woo gained fame by dwelling on Homeric preparations for combat and endlessly extended bouts of gunplay. From these masters Tarantino evidently learned the power of the slow crescendo and the sustained aria.

Leone and Woo’s amped-up passages rely chiefly on imagery and music. Tarantino is no slouch in either department, but he relies, like his beloved pulp writers, on talk. As everyone has noticed, the conversations in Basterds go on a very long time. In an era when scenes are supposed to run two to three minutes on average, Tarantino has only a couple this brief. The introduction at LaPadite’s farm runs over eighteen minutes, by my count, and the more complicated Chapter 2, with intercut flashbacks and flash-forwards, runs about the same length. Thereafter scenes last anywhere between four and twenty-four minutes, and Chapter 5’s crosscut climax consumes a stunning thirty-seven minutes. All but the last depend completely on dialogue. Leonard would probably consider them to have been fun to write.

Talk in Tarantino comes in two main varieties: banter and intimidation. At the coffee shop the Reservoir Dogs squabble and soliloquize; later exchanges will be conducted at gunpoint. En route to the preppies’ apartment, Jules and Vincent chat casually; when they arrive, the talk turns threatening. If Death Proof lets banter dominate, Inglourious Basterds goes to the other extreme. Here talk is a struggle between the powerful and the powerless.

As Jim Emerson points out, nearly every scene is an interrogation. This entails that someone in authority (Landa, Aldo, Hitler, the Germans who question Archie’s accent in the tavern, Zoller) is trying to pry information out of someone else. Intimidation through interrogation gives every scene an urgent shape. Now Tarantino’s digressions (three daughters, rats and squirrels, a card game, the correct pronunciation of Italian) don’t read as self-indulgence, but rather as feints in a confidence game. Here Tarantino’s tendency to write endless scenes, something he confesses in his recent Creative Screenwriting interview on the film, is fully harnessed to more classic, albeit unusually extended, scene structure.

To keep us focused on the lines and the actors delivering them, Tarantino has adopted a classical approach to style. He shoots with a single camera, so every composition is calculated. “I’m not Mr. Coverage,” he remarked in 1994, “. . . . I shoot one thing specifically and that’s all I get.” He foreswears handheld grab-and-go. In Basterds he locks his camera down, or puts it on a dolly or crane. Cinematographer Robert Richardson says that there is only one Steadicam shot in the film.

We don’t usually call Tarantino tactful, but his technique can be surprisingly discreet. He has the confidence to let key dialogue play offscreen: in the café when Landa arrives at Goebbels’ lunch, we stay fastened on Shosanna, a good old Hitchcockian ploy that ratchets up the tenson. Although Tarantino cuts rapidly throughout each chapter (on average every 5.6 seconds), he repeats setups quite a bit. This permits a simple change of angle or scale to mark a beat or shift the drama to a new level.

He can bury details on the fringes of the shot, as when the cut to the tight close-up of LaPadite shows him tossing his match into an ashtray sitting beside Landa’s cap, which bears the insignia of a skull and crossbones. It’s out of focus and on the edge of the screen, but the glimpse of it increases our fear that LaPadite is indeed harboring a Jewish family. As in Jackie Brown, another film that extends its scenes through detailing of performance, lighting, and setting, there seems no doubt that Tarantino, for all his PoMo reputation, appreciates some traditional Hollywood virtues.

He can inflect them, however. Richardson finds that Tarantino has an unusual approach to the anamorphic format.

I naturally move [the framing of characters] to one side or the other, especially when shooting anamorphic, whereas Quentin enjoys dead-center framing. For singles in particular, we’re just cutting dead-center framing from one side to the other, with the actors looking just past the barrel of the lens.

I noticed this tendency most in the reverse angles. Tarantino’s two-shots tend to be simple and symmetrical, shooting the characters in profile, as in the image surmounting this entry. But in over-the-shoulder shots, about half the frame is unoccupied—as if Tarantino were compensating, like his 1970s mentors, for an eventual TV pan-and-scan version of the scene.

Or take the cliché of arcing the camera around a group of chatting people, picking up one after the other. Tarantino didn’t invent this, but the opening scene of Reservoir Dogs probably helped popularize it. In Chapter 5 he uses the technique in the lobby of the Le Gamaar cinema, only to break its momentum by having the camera trail Landa when he breaks out of the circle and retreats, in a paroxysm of giggles, after Bridget says she broke her leg while mountain climbing.

There are many other intriguing touches, like the mixed typography of the opening credits, all of which seem to use fonts derived from 1970s paperback novels. Or the reference to The Saint in New York, perhaps less important for its plot parallels than for the fact that author Leslie Charteris’ later Saint novel, Prelude to War (1938), was banned in Germany and Italy for its attacks on fascism (even warning about the camps). So is reading a Saint novel a covert act of defiance on Shosanna’s part? Later, she applies make-up in fierce strokes, like an American Indian, reminding us that Raine’s Basterds model their tactics on the Apache.

There are many other intriguing touches, like the mixed typography of the opening credits, all of which seem to use fonts derived from 1970s paperback novels. Or the reference to The Saint in New York, perhaps less important for its plot parallels than for the fact that author Leslie Charteris’ later Saint novel, Prelude to War (1938), was banned in Germany and Italy for its attacks on fascism (even warning about the camps). So is reading a Saint novel a covert act of defiance on Shosanna’s part? Later, she applies make-up in fierce strokes, like an American Indian, reminding us that Raine’s Basterds model their tactics on the Apache.

Perhaps most striking is the dairy motif, from the glass of milk in Chapter 1 to Landa’s ordering a glass for Shosanna in Chapter 3. Is this a hint that he suspects her of being the girl who fled the massacre? Or is it a test he offers to any French national he meets? In the restaurant scene, the extreme close-ups of the crème fraiche may underscore the possibility that Landa is looking for signs that she won’t eat dairy products not prepared according to Orthodox dietary rules. Few filmmakers today would trust audiences to imagine this possibility on their own; instead we’d get an explanation to an underling. (“So here’s a quick way to find out if we have a Jew ….”)

Another nest of details involves the film-within-the-film, Nation’s Pride. Many online critics have noticed that it provides the sort of film that Basterds refuses to be: We never see our squad in the sort of Merrill’s Marauders skirmishes we probably expected going in. What I find intriguing about the movie, purportedly directed by Eli Roth, is that despite some anachronisms it exemplifies the sort of confrontational cinema we find in the silent Soviet pictures. Surprisingly, this was a tradition that Goebbels admired. Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, he claimed, “was so well made that it could make a Bolshevist out of anyone without a firm philosophical footing.” So in Nation’s Pride Roth and Tarantino have provided a Nazified homage to Eisenstein: a baby carriage rolls away from a mother, a soldier suffers an assault to the eye reminiscent of the wounding of the schoolteacher on the Odessa Steps, and even Soviet-style axial cut-ins are used for kinetic impact.

This pastiche of agitprop culminates in the sort of to-camera address we find in Dovzhenko. Zoller shouts, “Who wants to send a message to Germany?” But this is followed by Shosanna’s spliced-in close-up addressing the audience in her theatre.

She makes her own confrontational cinema.

Several years ago the film theorist Noël Carroll speculated that the Movie Brats of the 1970s sought to create a shared culture of media savvy that would replace the traditional culture based on religion, classical mythology, and official history. For the baby boomers, knowledge of the Christian Bible and iconography of American history would be replaced by deep familiarity with movies, pop music, and TV. This secular sacred would bind the audience in a new set of traditions. On this path, Scorsese, Spielberg, and Lucas didn’t go as far as Tarantino has. In his films every situation or character name or line of dialogue feels like a citation, a link in a web of pop-culture associations. (Aldo Raine = Aldo Ray = Bruce Willis, whom Tarantino once compared to Aldo Ray.) The only other filmmaker I know who has achieved this supersaturated cross-referencing is Godard, another exponent of the vivid-moments model (though he uses it to create a more fragmentary whole). Tarantino is the most visible evidence of what Carroll called “The future of allusion.”

But it’s too limiting to see Tarantino’s films as merely anthologies of references. I think he wants more.

Many viewers seem to assume that Tarantino’s film is somewhat cold. The Basterds are grotesques, parodies of men on a mission; Shosanna, though in a sympathetic position, must maintain a frosty demeanor. Even revenge, so central to films that Tarantino admires, is served frigid here, a purely formal postulate, like the urge for vengeance animating classic kung-fu films.

There is cinema that asks you to empathize with its characters. Then there is cinema that aims to thrill you with a cascade of vivid moments. There is How Green Was My Valley (1941) and Citizen Kane (1941). I think that Tarantino’s films mostly tilt to the vivid-moment pole, seeking to win us through their immediate verve, the way film noir and the musical and the action movie often do. The young man arrested by great bits from blaxploitation and biker movies sees cinema not as merely piling up cinephiliac references—though that’s surely part of it—but as a flow of tingle-inducing gestures, turns of phrase, shot changes, musical entrances. There can be pure pleasure in having time to see how actors move, or savor their lines, or simply fill up physical space by being centered in the anamorphic frame. Our fascination with Landa comes, I suspect, from the spectacle of a man who is utterly enjoying himself every second.

We might be tempted to claim that this effort to create what Jim Emerson calls “movie-movie moments” actually breaks the film’s overall unity. But Tarantino keeps nearly everything in check by the architectural clarity of his plot. The carving of the swastika on Landa’s brow sets you squirming, but it reveals itself as the culmination of a process we have seen piecemeal up to now. It’s the last in a string of firecracker bursts that have kept the film humming along.

So I’m not convinced that Inglourious Basterds lacks emotion. The emotions Tarantino aims for will arise not from character “identification” but from the overall structure and texture of the work. We are to be stirred, enraptured, astonished by a procession of splendors big and small. It’s the tradition (again) of Eisenstein, particularly in the Ivan films, but also of Leone and, in another register, Greenaway. Formal virtuosity isn’t necessarily soulless; it can yield aesthetic rapture.

The most sophisticated analyses and interpretations I’ve found online are led off by the indefatigable Jim Emerson (start here to track his many entries on the subject), along with his knowedgeable readers, who furnished a book’s worth of commentary and critique. Jim provides links to many other writers’ work (here, for example), not all of which I’ve been able to absorb. For exhaustive, not to say exhausting, coverage of things Tarantino, visit The Archives.

On Tarantino’s time-shuffling and its relation to crime fiction, see my Way Hollywood Tells It, 90-91. In Chapter 7 of Film Art Kristin and I provide an analysis of the replayed scene in Jackie Brown. Tarantino’s comments on writing the Basterds script are in Jeff Goldsmith’s article, “Glorious,” in Creative Screenwriting 16, 4 (July/ August 2009), 20-29. His comments on coverage come from Gavin Smith, “When You Know You’re in Good Hands,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerry Peary (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 102. In the same interview he has illuminating comments on the role of the axis of action. Robert Richardson discusses filming Basterds in Benjamin Bergery, “A Nazi’s Worst Nightmare,” American Cinematographer 90, 9 (September 2009); the quotation here is from p. 47. This feature is available online here.

Goebbels’ remark on Battleship Potemkin is quoted in Klaus Kreimeier, The UFA Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company, trans. Robert and Rita Kimber (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996), 207. For background on Goebbels’ agenda for German cinema, summed up by Lt. Archie Hicox, see Eric Rentschler, The Ministry of Illusion: Nazi Cinema and Its Afterlife (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996). I talk about axial cutting in Eisenstein and other Soviet directors at various points in The Cinema of Eisenstein.

Noël Carroll’s comments about popular entertainment as a secular alternative to shared religious culture are in his essay, “The Future of Allusion: Hollywood in the Seventies (and Beyond),” in Interpreting the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 244, 261-63. On the idea of an emotionally arousing cinema that doesn’t rely on attachment to character psychology, see my Cinema of Eisenstein.

PS 20 Sept 2009: Curt Purcell, at The Groovy Age of Horror, finds a similar plot architecture emerging in the comic-book series Blackest Night.