Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

Superheroes for sale

DB here:

After a day at the movies, maybe I am living in a parallel universe. I go to see two films praised by people whose tastes I respect. I find myself bored and depressed. I’m also asking questions.

Over the twenty years since Batman (1989), and especially in the last decade or so, some tentpole pictures, and many movies at lower budget levels, have featured superheroes from the Golden and Silver age of comic books. By my count, since 2002, there have been between three and seven comic-book superhero movies released every year. (I’m not counting other movies derived from comic books or characters, like Richie Rich or Ghost World.)

Until quite recently, superheroes haven’t been the biggest money-spinners. Only eleven of the top 100 films on Box Office Mojo’s current worldwide-grosser list are derived from comics, and none ranks in the top ten titles. But things are changing. For nearly every year since 2000, at least one title has made it into the list of top twenty worldwide grossers. For most years two titles have cracked this list, and in 2007 there were three. This year three films have already arrived in the global top twenty: The Dark Knight, Iron Man, and The Incredible Hulk (four, if you count Wanted as a superhero movie).

This 2008 successes have vindicated Marvel’s long-term strategy to invest directly in movies and have spurred Warners to slate more comic-book titles. David S. Cohen analyses this new market here. So we are clearly in the midst of a Trend. My trip to the multiplex got me asking: What has enabled superhero comic-book movies to blast into a central spot in today’s blockbuster economy?

Enter the comic-book guys

It’s clearly not due to a boom in comic-book reading. Superhero books have not commanded a wide audience for a long time. Statistics on comic-book readership are closely guarded, but the expert commentator John Jackson Miller reports that back in 1959, at least 26 million comic books were sold every month. In the highest month of 2006, comic shops ordered, by Miller’s estimate, about 8 million books (and this total includes not only periodical comics but graphic novels, independent comics, and non-superhero titles). There have been upticks and downturns over the decades, but the overall pattern is a steep slump.

Try to buy an old-fashioned comic book, with staples and floppy covers, and you’ll have to look hard. You can get albums and graphic novels at the chain stores like Borders, but not the monthly periodicals. For those you have to go to a comics shop, and Hank Luttrell, one of my local purveyors of comics, estimates there aren’t more than 1000 of them in the U. S.

Moreover, there’s still a stigma attached to reading superhero comics. Even kitsch novels have long had a slightly higher cultural standing than comic books. Admitting you had read The Devil Wears Prada would be less embarrassing than admitting you read Daredevil.

For such reasons and others, the audience for superhero comics is far smaller than the audience for superhero movies. The movies seem to float pretty free of their origins; you can imagine a young Spider-Man fan who loved the series but never knew the books. What’s going on?

Men in tights, and iron pants

The films that disappointed me on that moviegoing day were Iron Man and The Dark Knight. The first seemed to me an ordinary comic-book movie endowed with verve by Robert Downey Jr.’s performance. While he’s thought of as a versatile actor, Downey also has a star persona—the guy who’s wound a few turns too tight, putting up a good front with rapid-fire patter (see Home for the Holidays, Wonder Boys, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Zodiac). Downey’s cynical chatterbox makes Iron Man watchable. When he’s not onscreen we get excelsior.

Christopher Nolan showed himself a clever director in Memento and a promising one in The Prestige. So how did he manage to make The Dark Knight such a portentously hollow movie? Apart from enjoying seeing Hong Kong in Imax, I was struck by the repetition of gimmicky situations–disguises, hostage-taking, ticking bombs, characters dangling over a skyscraper abyss, who’s dead really once and for all? The fights and chases were as unintelligible as most such sequences are nowadays, and the usual roaming-camera formulas were applied without much variety. Shoot lots of singles, track slowly in on everybody who’s speaking, spin a circle around characters now and then, and transition to a new scene with a quick airborne shot of a cityscape. Like Jim Emerson, I thought that everything hurtled along at the same aggressive pace. If I want an arch-criminal caper aiming for shock, emotional distress, and political comment, I’ll take Benny Chan’s New Police Story.

Then there are the mouths. This is a movie about mouths. I couldn’t stop staring at them. Given Batman’s cowl and his husky whisper, you practically have to lip-read his lines. Harvey Dent’s vagrant facial parts are especially engaging around the jaws, and of course the Joker’s double rictus dominates his face. Gradually I found Maggie Gyllenhaal’s spoonbill lips starting to look peculiar.

The expository scenes were played with a somber knowingness I found stifling. Quoting lame dialogue is one of the handiest weapons in a critic’s arsenal and I usually don’t resort to it; many very good movies are weak on this front. Still, I can’t resist feeling that some weighty lines were doing duty for extended dramatic development, trying to convince me that enormous issues were churning underneath all the heists, fights, and chases. Know your limits, Master Wayne. Or: Some men just want to watch the world burn. Or: In their last moments people show you who they really are. Or: The night is darkest before the dawn.

I want to ask: Why so serious?

Odds are you think better of Iron Man and The Dark Knight than I do. That debate will go on for years. My purpose here is to explore a historical question: Why comic-book superhero movies now?

Z as in Zeitgeist

More superhero movies after 2002, you say? Obviously 9/11 so traumatized us that we feel a yearning for superheroes to protect us. Our old friend the zeitgeist furnishes an explanation. Every popular movie can be read as taking the pulse of the public mood or the national unconscious.

I’ve argued against zeitgeist readings in Poetics of Cinema, so I’ll just mention some problems with them:

*A zeitgeist is hard to pin down. There’s no reason to think that the millions of people who go to the movies share the same values, attitudes, moods, or opinions. In fact, all the measures we have of these things show that people differ greatly along all these dimensions. I suspect that the main reason we think there’s a zeitgeist is that we can find it in popular culture. But we would need to find it independently, in our everyday lives, to show that popular culture reflects it.

*So many different movies are popular at any moment that we’d have to posit a pretty fragmented national psyche. Right now, it seems, we affirm heroic achievement (Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Kung Fu Panda, Prince Caspian) except when we don’t (Get Smart, The Dark Knight). So maybe the zeitgeist is somehow split? That leads to vacuity, since that answer can accommodate an indefinitely large number of movies. (We’d have to add fractions of our psyche that are solicited by Sex and the City and Horton Hears a Who!)

*The movie audience isn’t a good cross-section of the general public. The demographic profile tilts very young and moderately affluent. Movies are largely a middle-class teenage and twentysomething form. When a producer says her movie is trying to catch the zeitgeist, she’s not tracking retired guys in Arizona wearing white belts; she’s thinking mostly of the tastes of kids in baseball caps and draggy jeans.

* Just because a movie is popular doesn’t mean that people have found the same meanings in it that critics do. Interpretation is a matter of constructing meaning out of what a movie puts before us, not finding the buried treasure, and there’s no guarantee that the critic’s construal conforms to any audience member’s.

*Critics tend to think that if a movie is popular, it reflects the populace. But a ticket is not a vote for the movie’s values. I may like or dislike it, and I may do either for reasons that have nothing to do with its projection of my hidden anxieties.

*Many Hollywood films are popular abroad, in nations presumably possessing a different zeitgeist or national unconscious. How can that work? Or do audiences on different continents share the same zeitgeist?

Wait, somebody will reply, The Dark Knight is a special case! Nolan and his collaborators have strewn the film with references to post-9/11 policies about torture and surveillance. What, though, is the film saying about those policies? The blogosphere is already ablaze with discussions of whether the film supports or criticizes Bush’s White House. And the Editorial Board of the good, gray Times has noticed:

It does not take a lot of imagination to see the new Batman movie that is setting box office records, The Dark Knight, as something of a commentary on the war on terror.

You said it! Takes no imagination at all. But what is the commentary? The Board decides that the water is murky, that some elements of the movie line up on one side, some on the other. The result: “Societies get the heroes they deserve,” which is virtually a line from the movie.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). That’s the bait the Times writers took.

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Back to basics

If the zeitgeist doesn’t explain the flourishing of the superhero movie in the last few years, what does? I offer some suggestions. They’re based on my hunch that the genre has brought together several trends in contemporary Hollywood film. These trends, which can commingle, were around before 2000, but they seem to be developing in a way that has created a niche for the superhero film.

The changing hierarchy of genres. Not all genres are created equal, and they rise or fall in status. As the Western and the musical fell in the 1970s, the urban crime film, horror, and science-fiction rose. For a long time, it would be unthinkable for an A-list director to do a horror or science-fiction movie, but that changed after Polanski, Kubrick, Ridley Scott, et al. gave those genres a fresh luster just by their participation. More recently, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It, the fantasy film arrived as a respectable genre, as measured by box-office receipts, critical respect, and awards. It seems that the sword-and-sorcery movie reached its full rehabilitation when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King scored its eleven Academy Awards.

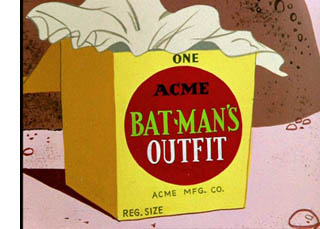

The comic-book movie has had a longer slog from the B- and sub-B-regions. Superman, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy were all fodder for serials and low-budget fare. Prince Valiant (1954) was the only comics-derived movie of any standing in the 1950s, as I recall, and you can argue that it fitted into a cycle of widescreen costume pictures. (Though it looks like a pretty camp undertaking today.) Much later came revivals of the two most popular superheroes, Superman (1978) and Batman (1989).

The success of the Batman film, which was carefully orchestrated by Warners and its DC comics subsidiary, can be seen as preparing the grounds for today’s superhero franchises. The idea was to avoid simply reiterating a series, as the Superman movie did, or mocking it, as the Batman TV show did. The purpose was to “reimagine” the series, to “reboot” it as we now say, the way Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns re-launched the Batman comic. Rebooting modernizes the mythos by reinterpreting it in a thematically serious and graphically daring way.

During the 1990s, less famous superheroes filled in as the Batman franchise tailed off. Examples were The Rocketeer (1991), Timecop (1994), The Crow (1994) and The Crow: City of Angels (1996), Judge Dredd (1995), Men in Black (1997), Spawn (1997), Blade (1998), and Mystery Men (1999). Most of these managed to fuse their appeals with those of another parvenu genre, the kinetic action-adventure movie.

Significantly, these were typically medium-budget films from semi-independent companies. Although some failed, a few were huge and many earned well, especially once home video was reckoned in. Moreover, the growing number of titles, sometimes featuring name actors, fueled a sense that this genre was becoming important. As often happens, marginal companies developed the market more nimbly than the big ones, who tend to move in once the market has matured.

I’d also suggest that The Matrix (1999) helped legitimize the cycle. (Neo isn’t a superhero? In the final scene he can fly.) The pseudophilosophical aura this movie radiated, as well as its easy familiarity with comics, videogames, and the Web, made it irrevocably cool. Now ambitious young directors like Nolan, Singer, and Brett Ratner could sign such projects with no sense they were going downmarket.

The importance of special effects. Arguably there were no fundamental breakthroughs in special-effects technology from the 1940s to the 1960s. But with motion-control cinematography, showcased in the first Star Wars installment (1977) filmmakers could create a new level of realism in the use of miniatures. Later developments in matte work, blue- and green-screen techniques, and digital imagery were suited to, and driven by, the other genres that were on the rise—horror, science-fiction, and fantasy—but comic-book movies benefited as well. The tagline for Superman was “You’ll believe a man can fly.”

Special effects thereby became one of a film’s attractions. Instead of hiding the technique, films flaunted it as a mark of big budgets and technological sophistication. The fantastic powers of superheroes cried out for CGI, and it may be that convincing movies in the genre weren’t really ready until the software matured.

The rise of franchises. Studios have always sought predictability, and the classic studio system relied on stars and genres to encourage the audience to return for more of what it liked. But as film attendance waned, producers looked for other models. One that was successful was the branded series, epitomized in the James Bond films. With the rise of the summer blockbuster, producers searched for properties that could be exploited in a string of movies. A memorable character could tie the installments together, and so filmmakers turned to pop literature (e.g., the Harry Potter books) and comic books. Today, Marvel Enterprises is less concerned with publishing comics than with creating film vehicles for its 5000 characters. Indeed, to get bank financing it put up ten of its characters as collateral!

Yet a single character might not sustain a robust franchise. Henry Jenkins has written about how popular culture is gravitating to multi-character “worlds” that allow different media texts to be carved out of them. Now that periodical sales of comics have flagged, the tail is wagging the dog. The 5000 characters in the Marvel Universe furnish endless franchise opportunities. If you stayed for the credit cookie at the end of Iron Man, you saw the setup for a sequel that will pair the hero with at least one more Marvel protagonist.

Merchandising and corporate synergy. It’s too obvious to dwell on, but superhero movies fit neatly into the demand that franchises should spawn books, TV shows, soundtracks, toys, apparel, and so on. Time Warner’s acquisition of DC Comics was crucial to the cross-platform marketing of the first Batman. Moreover, most comics readers are relatively affluent (a big change from my boyhood), so they have the income to buy action figures and other pricy collectibles, like a Batbed.

The shift from an auteur cinema to a genre cinema. The classic studio system maintained a fruitful, sometimes tense, balance between directorial expression and genre demands. Somewhere in recent decades that balance has split into polarities. We now have big-budget genre films that made by directors of no discernible individuality, and small “personal” films that showcase the director’s sensibility. There have always been impersonal craftsmen in Hollywood, but the most distinctive directors could often bring their own sensibilities to projects big or small.

David Lynch could make Dune (1984) part of his own oeuvre, but since then we have many big-budget genre pictures that bear no signs of directorial individuality. In particular, science-fiction, fantasy, and superhero movies demand so much high-tech input, so much preparation, so many logistical tasks in shooting, and such intensive postproduction, that economy of effort favors a standardized look and feel. Hence perhaps the recourse to well-established techniques of shooting and cutting; intensified continuity provides a line of least resistance. A comic-book movie can succeed if it doesn’t stray from the fanbase’s expectations and swiftly initiates the newbies. Not much directorial finesse is needed, as 300 (2007) shows.

The development of the megapicture may have led the more talented directors to the “one for them, one for me” motto. Think of the difference between Burton’s Planet of the Apes or even Sweeney Todd and, say, Ed Wood or Big Fish. Or think of the moments of elegance in Memento and The Prestige, as opposed to the blunt handling of Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Too much is never enough. Since the 1980s, mass-audience pictures have gravitated toward ever more exaggerated presentation of momentary effects. In a comedy, if a car is about to crash, everyone inside must stare at the camera and shriek in concert. Extreme wide-angle shooting makes faces funny in themselves (or so Barry Sonnenfeld thinks). Action movies shift from slo-mo to fast-mo to reverse-mo, all stitched together by ramping, because somebody thinks these devices make for eye candy. Steep high and low angles, familiar in 1940s noir films, were picked up in comics, which in turn re-influenced movies.

Movies now love to make everything airborne, even the penny in Ghost. Things fly out at us, and thanks to surround channels we can hear them after they pass. It’s not enough simply to fire an arrow or bullet; the camera has to ride the projectile to its destination—or, in Wanted, from its target back to its source. In 21 of earlier this year, blackjack is given a monumentality more appropriate to buildings slated for demolition: giant playing cards whoosh like Stealth fighters or topple like brick walls.

I’m not against such one-off bursts of imagery. There’s an undoubted wow factor in seeing spent bullet casings shower into our face in The Matrix.

I just ask: What do such images remind us of? My answer: Comic book panels, those graphically dynamic compositions that keep us turning the pages. In fact, we call such effects “cartoonish.” Here’s an example from Watchmen, where the slow-motion effect of the Smiley pin floating down toward us is sustained by a series of lines of dialogue from the funeral service.

With comic-book imagery showing up in non-comic-book movies, one source may be greater reliance on storyboards and animatics. Spfx demand intensive planning, so detailed storyboarding was a necessity. Once you’re planning shot by shot, why not create very fancy compositions in previsualization? Spielberg seems to me the live-action master of “storyboard cinema.” And of course storyboards look like comic-book pages.

The hambone factor. In the studio era, star acting ruled. A star carried her or his persona (literally, mask) from project to project. Parker Tyler once compared Hollywood star acting to a charade; we always recognized the person underneath the mime.

This is not to say that the stars were mannequins or dead meat. Rather, like a sculptor who reshapes a piece of wood, a star remolded the persona to the project. Cary Grant was always Cary Grant, with that implausible accent, but the Cary Grant of Only Angels Have Wings is not that of His Girl Friday or Suspicion or Notorious or Arsenic and Old Lace. Or compare Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve, Double Indemnity, and Meet John Doe. Young Mr. Lincoln is not the same character as Mr. Roberts, but both are recognizably Henry Fonda.

Dress them up as you like, but their bearing and especially their voices would always betray them. As Mr. Kralik in The Shop around the Corner, James Stewart talks like Mr. Smith on his way to Washington. In The Little Foxes, Herbert Marshall and Bette Davis sound about as southern as I do.

Star acting persisted into the 1960s, with Fonda, Stewart, Wayne, Crawford, and other granitic survivors of the studio era finishing out their careers. Star acting continues in what scholar Steve Seidman has called “comedian comedy,” from Jerry Lewis to Adam Sandler and Jack Black. Their characters are usually the same guy, again. Arguably some women, like Sandra Bullock and Ashlee Judd, also continued the tradition.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

Horror and comic-book movies offer ripe opportunities for this sort of masquerade. In a straight drama, confined by realism, you usually can’t go over the top, but given the role of Hannibal Lector, there is no top. The awesome villain is a playground for the virtuoso, or the virtuoso in training. You can overplay, underplay, or over-underplay. You can also shift registers with no warning, as when hambone supreme Orson Welles would switch from a whisper to a bellow. More often now we get the flip from menace to gargoylish humor. Jack Nicholson’s “Heeere’s Johnny” in The Shining is iconic in this respect. In classic Hollywood, humor was used to strengthen sentiment, but now it’s used to dilute violence.

Such is the range we find in The Dark Knight. True, some players turn in fairly low-key work. Morgan Freeman plays Morgan Freeman, Michael Caine does his usual punctilious job, and Gary Oldman seems to have stumbled in from an ordinary crime film. Maggie Gylenhaal and Aaron Eckhart provide a degree of normality by only slightly overplaying; even after Harvey Dent’s fiery makeover Eckhart treats the role as no occasion for theatrics.

All else is Guignol. The Joker’s darting eyes, waggling brows, chortles, and restless licking of his lips send every bit of dialogue Special Delivery. Ledger’s performance has been much praised, but what would count as a bad line reading here? The part seems designed for scenery-chewing. By contrast, poor Bale has little to work with. As Bruce Wayne, he must be stiff as a plank, kissing Rachel while keeping one hand suavely tucked in his pocket, GQ style. In his Bat-cowl, he’s missing as much acreage of his face as Dent is, so all Bale has is the voice, over-underplayed as a hoarse bark.

In sum, our principals are sweating through their scenes. You get no strokes for making it look easy, but if you work really hard you might get an Oscar.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

But of course the caricaturists got here first, from Hogarth and Daumier onward. Most memorably, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy strip offered a parade of mutilated villains like Flattop, the Brow, the Mole, and the Blank, a gentleman who was literally defaced. The Batman comics followed Gould in giving the protagonist an array of adversaries who would even raise an eyebrow in a Manhattan subway car.

Eisenstein once argued that horrific grotesquerie was unstable and hard to sustain. He thought that it teetered between the comic-grotesque and the pathetic-grotesque. That’s the difference, I suppose, between Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands, or between the Joker and Harvey Dent. In any case, in all its guises the grotesque is available to our comic-book pictures, and it plays nicely into the oversize acting style that’s coming into favor.

You’re thinking that I’ve gone on way too long, and you’re right. Yet I can’t withhold two more quickies:

The global recognition of anime and Hong Kong swordplay films. During the climactic battle between Iron Man 2.0 and 3.0, so reminiscent of Transformers, I thought: “The mecha look has won.”

Learning to love the dark. That is, filmmakers’ current belief that “dark” themes, carried by monochrome cinematography, somehow carry more prestige than light ones in a wide palette. This parallels comics’ urge for legitimacy by treating serious subjects in somber hues, especially in graphic novels.

Time to stop! This is, after all, just a list of causes and conditions that occurred to me after my day in the multiplex. I’m sure we can find others. Still, factors like these seem to me more precise and proximate causes for the surge in comic-book films than a vague sense that we need these heroes now. These heroes have been around for fifty years, so in some sense they’ve always been needed, and somebody may still need them. The major media companies, for sure. Gazillions of fans, apparently. Me, not so much. But after Hellboy II: The Golden Army I live in hope.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell for information about the history of the comics market.

The superhero rankings I mentioned are: Spider-Man 3 (no. 12), Spider-Man (no. 17), Spider-Man 2 (no. 23), The Dark Knight (currently at no. 29, but that will change), Men in Black (no. 42), Iron Man (no. 45), X-Men: The Last Stand (no. 75), 300 (no. 80), Men in Black II (no. 85), Batman (no. 95), and X2: X-Men United (no. 98). The usual caveat applies: This list is based on unadjusted grosses and so favors recent titles, because of inflation and the increased ticket prices. If you adjust for these factors, the list of 100 all-time top grossers includes seven comics titles, with the highest-ranking one being Spider-Man, at no. 33.

For a thoughtful essay written just as the trend was starting, see Ken Tucker’s 2000 Entertainment Weekly piece, “Caped Fears.” It’s incompletely available here.

Comics aficionados may object that I am obviously against comics as a whole. True, I have little interest in superhero comic books. As a boy I read the DC titles, but I preferred Mad, Archie, Uncle Scrooge, and Little Lulu. In high school and college I missed the whole Marvel revolution and never caught up. Like everybody else in the 1980s I read The Dark Knight Returns, but I preferred Watchmen (and I look forward to the movie). I like the Hellboy movies too. But I’m not gripped by many of the newest trends in comics. Sin City strikes me as a fastidious piece of draftsmanship exercised on formulaic material, as if Mickey Spillane were rewritten by Nicholson Baker. Since the 80s my tastes have run to Ware, Clowes, a few manga, and especially Eurocomics derived from the clear-line tradition (Chaland, Floc’h, Swarte, etc.). I believe that McCay and Herriman are major twentieth-century artists, with Chester Gould and Cliff Sterrett worth considering for the honor too.

You can argue that Oliver Stone’s films create ambivalence inadvertently. JFK seems to have a clear-cut message, but the plotting is diverted by so many conspiracy scenarios that the viewer might get confused about what exactly Stone is claiming really happened.

On the ways that worldmaking replaces character-centered media storytelling, the crucial discussion is in Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York University Press, 2007), 113-122.

On franchise-building, see the detailed account in detail in Eileen R. Meehan, “‘Holy Commodity Fetish, Batman!’: The Political Economy of a Commercial Intertext,” in The Many Lives of the Batman, ed. Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio (Routledge, 1991), 47-65. Other essays in this collection offer information on the strategies of franchise-building.

Just as Star Wars helped legitimate itself by including Alec Guinness in its cast (surely he wouldn’t be in a potboiler), several superhero movies have a proclivity for including a touch of British class: McKellan and Stewart in X-Men, Caine in the Batman series. These old reliables like to keep busy and earn a spot of cash.

PS: 21 August 2008: This post has gotten some intriguing responses, both on the Internets and in correspondence with me, so I’m adding a few here.

Jim Emerson elaborated on the zeitgeist motif in an entry at Scanners. At Crooked Timber, John Holbo examines how much the film’s dark cast owes to the 1990s reincarnation of Batman. Peter Coogan writes to tell me that he makes a narrower version of the zeitgeist argument in relation to superheroes in Chapter 10 of his book, Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, to be reprinted next year. Even the more moderate form he proposes doesn’t convince me, I’m afraid, but the book ought to be of value to readers interested in the genre.

From Stew Fyfe comes a letter offering some corrections and qualifications.

*Stew points out that chain stores like Borders do sell some periodical comics titles, though not always regularly.

*Comics publishing, while not at the circulation levels seen in the golden era, is undergoing something of a resurgence now, possibly because of the success of the franchise movies. Watchmen sales alone will be a big bump in anticipation of the movie.

*As for my claim that film is driving the publishing side, Stew suggests that the relations between the media are more complicated. The idea that the tail wags the dog might apply to DC, but Marvel has made efforts to diversify the relations between the books and the films.

They’ve done things like replacing the Hulk with a red, articulate version of the character just before the movie came out (which is odd because if there’s one thing that the general public knows about the character is that he’s green and he grunts). They’ve also handed the Hulk’s main title over to a minor character, Hercules. They’ve spent a year turning Iron Man, in the main continuity, into something of a techno-fascist (if lately a repentant one) who locks up other superheroes.

Stew speculates that Marvel is trying to multiply its audiences. It relies on its main “continuity books” to serve the fanbase who patronizes the shops, and the films sustain each title’s proprietary look and feel. In addition, some of the books offer fresh material for anyone who might want to buy the comic after seeing the film; this tactic includes reprinted material and rebooted continuity lines in the Ultimate series. Marvel has also brought in film and TV creators as writers (Joss Whedon, Kevin Smith), while occasionally comics artists work in TV shows like Heroes, Lost, and Battlestar Galactica. So the connections are more complex than I was indicating.

Thanks to all these readers for their comments.

News from the fragrant harbor

DB here:

For those of you who have had problems connecting with this site: Sorry! Our server was down for a couple of days. Ironically, I was one of the last to climb on. Hence the slight delay in this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Whither Hong Kong film?

The Warlords.

Local cinema is still in the doldrums. As in most countries, Hollywood rules the box office. Production has dropped to about 50 releases last year, and the quality of what I’ve seen over the last week isn’t on the whole strong.

I’m told by a film professional who follows things closely that critics feel that 12-15 local films from 2007 are worth seeing and about 5 are actually good. Those five are Ann Hui’s The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, Derek Yee’s Protégé, Johnnie To’s Mad Detective, Yau Na-hoi’s Eye in the Sky, and Peter Chan’s The Warlords. It’s significant, my friend indicates, that almost never before has the same clutch of films been nominated for best picture, best screenplay, and best director at the Hong Kong Film Awards. (The awards will be given on 13 April.) “The falling industry has reached a plateau,” she remarks.

My sense is that Hong Kong cinema is sustained, however minimally, on three levels. As usual, there are the program pictures, chiefly urban action films and romantic comedies and dramas. These come and go, using local singers and TV stars, and allow theatres to keep their doors open. More creative are the films from local auteurs, principally Johnnie To Kei-fung. (Should I count Wong Kar-wai as a local filmmaker any more?) To’s Milkyway company turns out several worthy items per year, most directed by To. As I indicate in an earlier post, The Sparrow is their upcoming release; it’s also the best Hong Kong movie I’ve seen so far on my trip.

A third category includes the increasingly important China coproductions, nearly always military costume dramas. The emblematic shot: Mighty warriors on mighty steeds galloping toward the camera in a telephoto framing. Add spears, swords, shields, and slow-motion to taste.

The Warlords is the prime instance from last year, but it was preceded by The Myth (2005) and A Battle of Wits (2006). The genre was made popular by Mainland movies like Zhang Yimou’s overdecorated epics, and it has already furnished us two spring releases, An Empress and the Warriors (yes, you read that right) and The Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon. Both are straightforward tales of military struggle, centering on loyalty and honor, with relatively little of the palace intrigue that usually furnishes plot motivation.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

The Three Kingdoms, a Korean-China coproduction directed by Hong Kong’s Daniel Lee, is a somewhat more impressive item. The plot traces the rise of a general (Andy Lau), aided by his mentor (Sammo Hung), and their confrontation with a rival general, whose cause is taken over by his daughter (Maggie Q). There is little characterization; everything hinges on honor, retribution, and service to one’s superior. A tranquil interlude with Andy’s love interest, a shadow puppeteer, is quickly forgotten in the rush to combat. The musical score channels Morricone, and as in Empress, it employs thunderous drumbeats, chanting male choruses, and a keening soprano. Inevitably, we also sense the influence of Wong Kar-wai in the meditative voice-over and the fight scenes (choreographed by Sammo) that recall Ashes of Time in their slurring and spasmodic rhythms.

Are such films really desired by Asian audiences, let alone Western ones? The jury is still out. Thanks to shooting in China and the diffusion of CGI technology, such genre pieces can be made for much less than Hollywood would spend. Three Kingdoms came in at less than US$20 million, which is twice the budget purportedly spent on Empress. But international sales of the genre are spotty, and audience uptake isn’t overwhelming. Somebody will have to tweak the formula creatively. Will it be John Woo, with Red Cliff? Odds are against it, but I’d like to be surprised.

Incorrigibly optimistic, I’m still looking forward to Ann Hui’s newest film, The Way We Are, premiering tonight, and Coffee or Tea, the collaboration of veteran director Shu Kei and his student Mandrew Kwan Man-hin. That’s the closing film of the festival.

Films briefly noted

Kabei–Our Mother.

Other festival highlights for me:

Please Vote for Me! A primary school in Wuhan is introduced to democracy when the teacher decides that the monitor will be elected by the class. There ensues a struggle all too reminiscent of U.S. political campaigns. We have sound bites, applause lines, political operatives (here, overzealous parents), scurrilous charges, personal attacks, and outright bribery. The collision of human nature and democratic ideals make this a charming and thoughtful movie. I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it, if only for its reminder of how humiliation feels when you’re nine years old.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Mauerpark. From the Austrian collective Stadtmusik, Tati-goes-Betacam. A long shot of a snow-covered park is at first puzzling, then amusing, then engrossing.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

The weirdness comes in the color values–sometimes blinding orange, sometimes bilious green reminiscent of Sovcolor—and in a murmuring soundtrack that blends machine whirs and conversation with barely discernible swoops of orchestral and vocal music. (Since Galina Vishnevskaya plays the old lady, are these fragments from her performances?) Nobody makes soundtracks quite like Sokurov; even an unadorned shot can take on urgency through the drifting whispers our ears struggle to make out.

Jim Hoberman has a discerning review here.

Elegy of Life. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Also a pleasure to listen to, but much more straightforward. A documentary tribute to the great cellist/ conductor and the singer. Since I’m interested in Russian music and cultural politics, this was an unadorned pleasure. To hear Rostropovich compare Prokofiev the classicist with Shostakovich the Mahlerian was especially worthwhile.

Kabei—Our Mother. Yamada Yoji received a lifetime tribute at the Asian Film Awards. Having directed over seventy movies, including the long-running Tora-san series, he’s usually discussed in terms of sheer productivity. But his calm, grave period films Twilight Samurai (2002), Hidden Blade (2004), and Love and Honor (2006) have reminded people that he’s a fine director too. A man of restraint, he never shoots handheld, he seldom moves the camera, and he uses close-ups as high points, not default values. His sobriety makes the 1.85 ratio look as cleanly fitted to the human body as the 1.33 one is. “The last classical director,” Mike Walsh called Yamada after the screening, and it’s hard to disagree.

Kabei was for me the high point of the festival so far. It’s 1940, and a Tokyo intellectual is arrested for “thought crimes.” As he endures prison, his wife and two daughters struggle to make ends meet, with the help of Yamazaki, a loyal student. An epilogue reminds us of the now-elderly mother’s devotion to her husband.

That’s about it, but the poise of the performances and the simplicity of the presentation make this like a film from the era it portrays. I wish I had a DVD to illustrate the craftsmanship that Yamada brings to the very first shot, which unhurriedly introduces the family while the mother simply hangs out wash on the line. I wish I could show you how the moment that a badminton birdie lands on a rooftop pivots from comedy to sadness. I wish I could replicate the composition that hides a weeping Yamazaki from us—a shot that actually makes the audience burst into laughter. Who else would have the film’s biggest star, Tadanobu Asano, keep his back to us for an entire scene?

But maybe it’s better I don’t give such things away. Best to say: Despite all the other movies you see, Kabei shows one way that cinema can still be.

Finally, as antidote to my somewhat depressing diagnosis of the state of HK film, two items. First, the reception for Sylvia Chang‘s Run, Papa, Run showed off her lively charm. Here Sylvia, in black, is flanked by her stars, Yuhan Liu, Rene Liu, Lewis Koo, and Nora Miao, who played in Bruce Lee pictures.

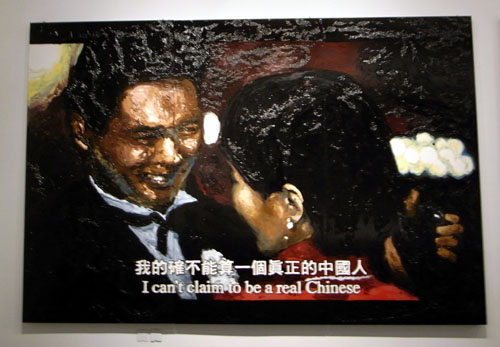

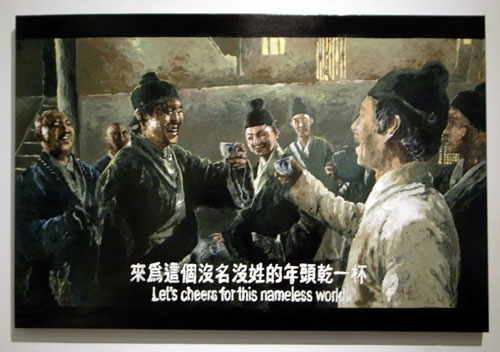

Second, in the entertaining exhibit Made in Hong Kong at the art museum, you will find the work of Chow Chun-fai, whose output includes large, glossy enamel images taken from movies, complete with letterboxing and subtitles (typically about Chinese/ Hong Kong identity). The blocky figures seem both chunkily monumental and somewhat decaying. One of Chow’s huge pictures, derived from Love in a Fallen City, surmounts this blog entry. Below is another, based on King Hu’s Dragon Inn.

More to come in a few days, including, I hope, thoughts on Maya Deren and an interview about sound design in Milkyway movies.

PS later on 27 March: I’ve just discovered a remarkable array of comments on Alexandra in this Criterion thread. John Cope‘s discussion is particularly admirable.

A behemoth from the Dead Zone

DB here:

The first quarter of the year is the biggest slump time for movie theatres. (1) Holiday fatigue, thin budgets, bad weather, the Super Bowl, and the distractions of the awards season depress admissions. If people go to the movies, they tend to catch up on Oscar nominees, and studios don’t want to release high-end films that might suffer from the competition. But screens need fresh product every week, so most of what gets released at this time of the year might charitably be called second-tier.

Ambitious filmmakers fight to keep out of this zone of death. You could argue that the January release slot of Idiocracy told Mike Judge exactly what Fox thought of that ripe exercise in misanthropy. Zodiac, one of the best films of 2007, opened on 1 March, and even ecstatic reviews couldn’t push it toward Oscar nominations. You can imagine what chances for success Columbia has assigned to Vantage Point (a 22 February bow). [But see my 4 Feb. PPPS below.]

Yet this is a flush period for those of us who like to explore low-budget genre pieces. I have to admit I enjoy checking on those quickie action fests and romantic comedies that float up early in the year. They’re today’s equivalent of the old studios’ program pictures, those routine releases that allowed theatres to change bills often. In their budgets, relative to blockbusters, today’s program pix are often the modern equivalent of the studios’ B films.

More important, these winter orphans are often more experimental, imaginative, and peculiar than the summer blockbusters. On low budgets, people take chances. Some examples, not all good but still intriguing, would be Wild Things (1998), Dark City (1998), Romeo Must Die (2000), Reindeer Games (2000), Monkeybone (2001), Equilibrium (2002), Spun (2003), Torque (2004), Butterfly Effect (2004), Constantine (2005), Running Scared (2006), Crank (2006), and Smokin’ Aces (2007). The mutant B can be found in other seasons too—one of my favorites in this vein, Cellular (2004), was released in September—but they’re abundant in the year’s early months.

By all odds, Cloverfield ought to have been another low-end release. A monster movie with unknown players, running a spare 72 minutes sans credits, budgeted at a reputed $25 million, it’s a paradigm of the winter throwaway. Except that it pulled in $46 million over a four-day weekend and became the highest-grossing film (in unadjusted dollars) ever to be released in January. Here the B in “B-movie” stands for Blockbuster.

I enjoyed Cloverfield. It starts with a sharp premise, but as ever, execution is everything. I see it as a nifty digital update of some classic Hollywood conventions. Needless to say, many spoilers loom ahead.

If you find this tape, you probably know more about this than I do

Everybody knows by now that Cloverfield is essentially Godzilla Meets Handicam. A covey of twentysomethings are partying when a monster attacks Manhattan, and they try to escape. One, Rob, gets a phone call from his off-again lover Beth, who’s trapped in a high-rise. He vows to rescue her. He brings along some friends, one of whom documents their search with a video camera. It’s a shooting-gallery plot. One by one, the characters are eliminated until we’re down to two, and then. . . .

Cloverfield exemplifies what narrative theorists call restricted narration. (Kristin and I discuss this in Chapter 3 of Film Art.) In the narrowest case of restricted narration, the film confines the audience’s range of knowledge to what one character knows. Alternatively, as when the characters are clustered in the same space, we’re restricted to what they collectively know. In other words, you deny the viewer a wider-ranging body of story information. By contrast, the usual Godzilla installment is presented from an omniscient perspective, skipping among scenes of scientists, journalists, government officials, Godzilla’s free-range ramblings, and other lines of action. Instead, Cloverfield imagines what Godzilla’s attack would look and feel like on the ground, as observed by one group of victims.

Horror and science fiction films have used both unrestricted and restricted narration. A film like Cat People (1942) crosscuts what happens to Irena (the putative monster) with scenes involving other characters. Jurassic Park and The Host likewise trace out several plot strands among a variety of characters. The advantage of giving the audience so much information is that it can feel apprehension and suspense about what the characters don’t know is happening. Our superior knowledge can make us worry about those poor victims oblivious to their fate.

But these genres have relied on restricted narration as well. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is a good example; we are at Miles’s side in almost every scene, learning of the gradual takeover of his town as he does. Night of the Living Dead (1968), Signs (2002), and War of the Worlds (2005) do much the same with a confined group, attaching us to one or the other momentarily but never straying from their situation.

The advantages of restricted narration are pretty apparent. You can build up uncertainty and suspense if we know no more than the character(s) being attacked by a monster. You can also delay full revelation of the creature, a big deal in these genres, by giving us only the glimpses of it that our characters get. Arguably as well, by focusing on the characters’ responses to their peril, you have a chance to build audience involvement. We can feel empathy and loss if we’ve come to know the people more intimately than we know the anonymous hordes stomped by Godzilla. Finally, if you need to give more wide-ranging information about what’s happening outside the characters’ immediate situation, you can always have them encounter newspaper reports, radio bulletins, and TV coverage of action occurring elsewhere.

People sometimes think that theoretical distinctions like this overintellectualize things. Do filmmakers really think along these lines? Yes. Matt Reeves, the director of Cloverfield, remarks:

The point of view was so restricted, it felt really fresh. It was one of the things that attracted me [to this project]. You are with this group of people and then this event happens and they do their best to understand it and survive it, and that’s all they know.

For your eyes only

Restricted narration doesn’t demand optical point-of-view shots. There aren’t that many in Invasion of the Body Snatchers or the other examples I’ve indicated. Still, for quite a while and across a range of genres, filmmakers have imagined entire films recording a character’s optical/ auditory experience directly, in “first-person,” so to speak.

Again, it’s useful to recognize two variants of this narrational strategy. One we can call immediate—experiencing the action as if we stood in the character’s shoes. In the late 1920s, the great documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens tried to make what he called his I-film, which would record exactly what a character saw when riding a bike, drinking a glass of beer, and the like. He was dismayed to find that bouncing and swiveling the camera as if it were a human eye ignored the fact that in real life, our perceptual systems correct for the instabilities of sensation. Ivens abandoned the project, but evidently he couldn’t get the notion out of his head; he called his autobiography The Camera and I. (2)

Hollywood’s most strict and most notorious example of directly subjective narration is Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the Lake (1947). Its strangeness reminds us of some inherent challenges in this approach. How do you show the viewer what your protagonist looks like? (Have him pass in front of mirrors.) How do you skip over the boring bits? (Have your hero knocked unconscious from time to time.) How do you hide the inevitable cuts? (Try your best.) Even Montgomery had to treat the subjective sequences as long flashbacks, sandwiched within scenes of the hero in his office in the present telling us what he did next.

Because of these problems, a sustained first-person immediate narration is pretty rare. The best compromise, exploited by Hitchcock in many pictures and especially in Rear Window (1954), is to confine us to a single character’s experience by alternating “objective” shots of the character’s action with optical point-of-view shots of what s/he sees.

What I’m calling immediate optical point of view is just that: sight (and sounds) picked up directly, without a recording mechanism between the story action and the character’s experience. But we can also have mediated first-person point of view. The character uses a recording technology to give us the story events.

In a brilliant essay on the documentary Kon-Tiki (1950), André Bazin shows that our knowledge of how Thor Heyerdahl filmed his raft voyage lends an unparalleled authenticity to the action. Heyerdahl and his crew weren’t experienced photographers and seem to have taken along the 16mm camera as an afterthought, but the very amateurishness of the enterprise guaranteed its realism. Its imperfections, often the result of hazardous conditions, were themselves testimony to the adventure. When the men had to fight storms, they had no time to film; so Bazin is able to argue, with his inimitable sense of paradox, that the absence of footage during the storm is further proof of the event. If we were given such footage, we might wonder if it was staged afterward.

How much more moving is this flotsam, snatched from the tempest, than would have been the faultless and complete report offered by an organized film. . . . The missing documents are the negative imprints of the expedition. (3)

What about fictional events? In the 1960s we started to see fiction films that presented themselves as recordings of the events as the camera operator experienced them. One early example is Stanton Kaye’s Georg (1964). The first shot follows some infantrymen into battle, but then the framing wobbles and the camera falls to earth. We see a tipped angle on a fallen solider and another infantryman approaches.

He bends toward us; the frame starts to wobble and we are lifted up. On the soundtrack we hear, “I found my camera then.”

The emergence of portable equipment and cinema-verite documentary seems to have pushed filmmakers to pursue this narrational mode in fiction. One result was the pseudo-documentary, which usually doesn’t present the story as a single person’s experience but rather as a compilation of first-person observations. Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1967) presents itself as a documentary shot during a nuclear war, and it contains many of the visual devices that would come to be associated with the mediated format—not only the flailing camera but the face-on interview and the chaotic presentation of violent action. There’s also the pseudo-memoir film, pioneered in David Holzman’s Diary (1967). Later examples of the pseudo-documentary are Norman Mailer’s Maidstone (1971) and the combat movie 84 Charlie MoPic (1989). (4)

As lightweight 16mm cameras made filming easier, directors adapted that look and feel to fictional storytelling. The arrival of ultra-portable digital cameras and cellphones has launched a similar cycle. Brian DePalma’s Redacted (2007), yet another war film, has exploited the technology for docudrama. A digital equivalent of David Holzman’s Diary, apart from Webcam and YouTube material, is Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), which I discussed here.

Interestingly, Orson Welles pioneered both the immediate and the mediated subjective formats. One of his earliest projects for RKO was an adaptation of Heart of Darkness, in which the camera was to represent the narrator Marlowe’s optical perspective throughout. (5) Welles had more success with the mediated alternative, though in audio form. His “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast mimicked the flow of programming and interrupted it with reports of the aliens’ attack. The device was updated for television in the 1983 drama Special Bulletin.

Sticking to the rules

Cloverfield, then, draws on a tradition of using technologically mediated point-of-view to restrict our knowledge. Like The Blair Witch Project (1999), it does this with a horror tale. But it’s also a Hollywood movie, and it follows the norms of that moviemaking mode. So the task of Reeves, producer J. J. Abrams, and the other creators is to fit the premise of video recording to the demands of classical narrative structure and narration. How is this done?

First, exposition. The film is framed as a government SD video card (watermarked DO NOT DUPLICATE), the remains of a tape recovered from an area “formerly known as Central Park.” This is a modern version of the discovered-manuscript convention familiar from the nineteenth-century novel. When the tape starts, showing Rob with Beth in happy times, its read-out date of April plays the role of an omniscient opening title. In the course of the film, the read-outs (which come and go at strategic moments) will tell us when we’re in the earlier phase of their love affair and when we’re seeing the traumatic events of May.

Likewise, the need for exposition about characters and relationships at the start of the film is given through a basic premise. Jason wants to record Rob’s going-away-party and he presses Rob’s friend Hud into service as the cameraman. Off the bat, Hud picks out our main characters in video portraits addressed to Rob. What follows indicates that Hud will be amazingly prescient: His camera dwells on the characters who will be important in the ensuing action.

Next, overall structure. The Cloverfield tape conforms to the overarching principles that Kristin outlines in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and that I restated in The Way Hollywood Tells It. (Another example can be found here.) A 72-minute film won’t have four large-scale parts, most likely two or three. As a first approximation, I think that Cloverfield breaks into:

*A setup lasting about 30 minutes. We are introduced to all the characters before the monster attacks. Our protagonists flee to the bridge, where Jason dies. Near the end of this portion, Rob gets a call from Beth, and he formulates the dual goals of the film: to escape from the creature, and to rescue Beth. Along the way, Hud declares he’s going to record it all: “People are gonna know how it all went down. . . . It’s gonna be important.”

*A development section lasting about 22 minutes. This is principally a series of delays. Rob, Hud, Lily, and Marlena encounter obstacles. Marlena falls by the wayside. They are given a deadline: At 0600 they must meet the last helicopters leaving Manhattan.

*A climax lasting about 20 minutes. The group rescues Beth and meets the choppers, but the one carrying Rob, Hud, and Beth falls afoul of the beast. They crash in Central Park, and Hud is killed, his camera recording his death at the jaws of the monster. Huddled under a bridge, Rob and Beth record a final video testimonial before an explosion cuts them off.

*An epilogue of one shot lasting less than a minute: Rob and Beth in happier times on the Ferris wheel at Coney Island—a shot left over from the earlier use of the tape in April.

Next, local structure and texture. It takes a lot of artifice to make something look this artless. The imagery is rich and vivid, the sharpest home video you ever saw. The sound is pure shock-and-awe, bone-rattling, with a full surround ambience one never finds on a handicam. (6) Moreover, Hud is remarkably lucky in catching the turning points of the action. All the characters’ intimate dramas are captured, and Hud happens to be on hand when the head of Miss Liberty hurtles down the street.

Bazin points out that in fictional films the ellipses are cunning gaps, carefully designed to fulfill narrative ends—not portions left out because of the physical conditions of the shoot. Here the cunning gaps are justified as constrained by the physical circumstances of filming. When Hud doesn’t show something, it’s usually because it’s what the genre considers too gross, so the worst stretches take place in darkness, or offscreen, or strategically shielded by a prop when the camera is set down.

Mostly, though, Hud just shows us the interesting stuff. He turns on the camera just before something big happens, or he captures a disquieting image like that of the empty Central Park carriage.

At least once, the semi-documentary premise does yield something evocative of the Kon-Tiki film. Hud has to leap from one building to another, many stories above the street. He turns the camera on himself: “If this is the last thing you see, then I died.” He hops across, still running the camera, but when a rocket goes off nearby, a sudden cut registers his flinch. For an instant out of sheer reflex, he turned off the camera.

Overall, Hud’s tape respects the flow of classical film style. Unlike the Lady in the Lake approach, the mediated POV format doesn’t have a problem with cuts; any jump or gap is explained as a moment when the operator switched off the camera. Most of Hud’s “in-camera” cuts are conventional ones, skipping over a few inconsequential stretches of time. There are as well plenty of hooks between scenes. (For more on hooks, go here.) Hud says: “I’ll walk in the tunnels.” Cut to characters walking in the tunnels. More interestingly, visible cuts are rare, which again respects the purported conditions of filming. Cloverfield has much longer takes than any recent Hollywood film I know. I counted only about 180 shots, yielding an average of 24 seconds per shot (in a genre in which today’s films average 2-5 seconds per shot).

The digital palimpsest

We could find plenty of other ways in which Cloverfield adapts the handicam premise to the Hollywood storytelling idiom. There are the product placements that just happen to be part of these dim yuppies’ milieu. There are the character types, notably the sultry Marlena and the hero’s weak friend who’s comically a little slow. There’s the developing motif of the to-camera addresses, with Rob and Beth’s final monologues to the camera counterbalancing the party testimonials in the opening. There’s the final romantice exchange: “I love you.” “I love you.” The very last shot even includes a detail that invites us to re-view the entire movie, at the theatre or on DVD. But let me close by noting how some specific features of digital video hardware get used imaginatively.

I’ve already mentioned how the viewfinder date readout allows us to keep the time structure clear. There’s also the use of a night-vision camera feature to light up those spidery parasites shucked off by the big guy. Which scares you more—to glimpse the pinpoint eyes of critters skittering around you in the dark, or to see them up close in a sickly green light?

More teasing is the fact, set up in the first part, that this video is being recorded over an old tape of Rob’s. That’s what turns the opening sequence of Rob and Beth in May into a prologue: the tape wasn’t rewound completely for recording the party. Later, at intervals, fragments of that April footage reappear, apparently through Hud’s inadvertently advancing the tape. The snippets functions as flashbacks, showing Rob and Beth going to Coney Island and juxtaposing their enjoyable day with this horrendous night.

Cleverly, on the tape that’s recording the May disaster something always prepares the audience for the shift. For instance, when Jason hands the camera over, we hear Hud say, “I don’t even know how to work this thing.” Cut to an April shot of Beth on the subway, suggesting that he’s advanced fast forward without shooting. Likewise, when Rob says, “I had a tape in there,” we cut to another April shot of Beth. As a final fillip, the footage taken in May halts before the tape ends, so we get the epilogue showing Rob and Beth on the Ferris wheel in April, emerging like figures in a palimpsest.

No less clever, but also a little poignant, is the use of the fallen-camera convention. It appears once when Beth has to be extricated from her bed. Hud sets the camera down by a concrete block in her bedroom, which conceals her agony. More striking is the shot when the camera, dropped from Hud’s hand, lies in the grass, and the autofocus device oscillates endlessly, straining to hold on his lifeless face.

In sum, the filmmakers have found imaginative ways of fulfilling traditional purposes. They show that the look and feel of digital video can refresh genre conventions and storytelling norms. So why not for the sequel show the behemoth’s attack from still other characters’ perspectives? This would mobilize the current conventions of the narrative replay and the companion film (e.g., Eastwood’s Iwo Jima diptych). Reeves says:

The fun of this movie was that it might not have been the only movie being made that night, there might be another movie! In today’s day and age of people filming their lives on their iPhones and Handycams, uploading it to YouTube. . . .

So the Dead Zone of January through March yields another hopeful monster. What about next month’s Vantage Point? The tagline is: 8 Strangers. 8 Points of View. 1 Truth. Hmmm. . . . Combining the network narrative with Rashomon and a presidential assassination. . . . Bet you video recording is involved . . . . See you there?

PS: At my local multiplex, you’re greeted by a sign: WARNING: CLOVERFIELD MAY INDUCE MOTION SICKNESS. I thought this was just the theatre covering itself, but I’ve learned that no recent movie, not even The Bourne Ultimatum, has had more viewers going giddy and losing their lunch. You can read about the phenomenon here, and Dr. Gupta weighs in here. My gorge can rise when a train jolts, but I had no problems with two viewings of Cloverfield, both from third row center.

Anyhow, it will be perfectly easy to watch on your cellphone. But we should expect to see at least one pirate version shot in a theatre by someone who’s fighting back the Technicolor yawn, giving us more Queasicam than we bargained for.

(1) The only period that rivals this slow winter stretch is mid-August to October, when genre fare gets pushed out to pick up on late summer business. [Added 26 January:] There are, I should add, two desirable weekends in the first quarter, those around Martin Luther King’s birthday and Presidents’ Day. Studios typically aim their highest-profile winter releases (e.g., Black Hawk Down, 2001) for those weekends.

(2) Joris Ivens, The Camera and I (New York: International Publishers, 1969), 42.

(3) André Bazin, “Cinema and Exploration,” What Is Cinema? Vol. 1, trans. and ed. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 162.

(4) Not all pseudodocumentaries present themselves as records of a person’s observation. Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart (1969) presents itself as an objective record, by a hidden camera, of a psychiatrist’s dealings with his patients. Like a surveillance camera, it doesn’t purport to embody anybody’s point of view.

(5) Jonathan Rosenbaum, Discovering Orson Welles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 28-48.

(6) For Kevin Martin’s informative account of the film’s polished lighting and high-definition video capture, go here (and scroll down a bit). For discussions of contemporary sound practices in this genre, see William Whittington’s Sound Design in Science Fiction (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007).

PS: Thanks to Corey Creekmur for correcting two slips in my initial post!

PPS 28 January: Lots of Internet buzz about the film since I wrote this. Thanks to everyone who linked to this post, and special thanks for feedback from John Damer and James Fiumara.

Some people have asked me to comment on the social and cultural implications of Cloverfield’s references to 9/11. At this point I think that genre cinema has dealt more honestly and vividly with the traumas and questioning around this horrendous event than the more portentous serious dramas like United 93, World Trade Center, and the TV show The Road to 9/11.

The two most intriguing post-9/11 films I know are by Spielberg. The War of the Worlds gives a really concrete sense of what a hysterical America under attack might be like, warts and all. (It reminded me of a TV show I saw as a kid, Alas, Babylon (1960), a surprisingly brutal account of nuclear-war panic in suburbia.) Spielberg’s underrated The Terminal reminds us, despite its Frank Capra optimism, that the new Security State is run by bureaucrats with fixed agendas and staffed by overworked people of color, some themselves exiles and immigrants.

I think that Cloverfield adds its own dynamic sense of how easily the entitlement culture of upwardly mobile twentysomethings can be shattered. Genre films carry well-established patterns and triggers for feelings, and a shrewd filmmaker can channel them for comment on current events—as we see in the changing face of Westerns and war films in earlier phases of Hollywood history.

On this point, Cinebeats offers some shrewd responses to criticisms of Cloverfield here.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

PPS 30 January: Shan Ding brings me another story about the making of Cloverfield, and Reeves is already in talks for a sequel, says Variety.

PPPS 4 February: A recent story in The Hollywood Reporter offers a nuanced account of how Hollywood is rethinking its first-quarter strategies. Across the last 4-5 years, a few big releases have done fairly well between January and April; a high-end film looks bigger when there is less competition. The author, Steven Zeitchik, suggests that the heavy packing of the May-August period and the need for a strong first weekend are among the factors that will encourage executives to spread releases through the less-trafficked months. I hope, though, that tonier fare won’t crowd out the more edgy, low-end genre pieces that bring me in.

PPPPS 8 February: How often has a wounded Statue of Liberty featured in the apocalyptic scenarios of comics and the movies? Lots, it turns out. Gerry Canavan explains here.

Your trash, my TREASURE

DB here:

More informative about American history than Fahrenheit 9/11. More brain-teasing, and far more enjoyable, than I’m Not There. Less graphically violent than almost any other movie you’re likely to see. What else could I be talking about but National Treasure: Book of Secrets?

Jerry Bruckheimer is, in my view, the most astute producer now working in Hollywood. I could cite many proofs, but let’s stick just to the first National Treasure. Here’s a movie with no pop music, no cusswords, no naked ladies, no drugs, no screwing, and scarcely any violence. (One bad guy accidentally falls to his death down a deep black hole.) When it came out—you can verify this by asking Kristin—I said that it was the ideal movie for grandparents to take the grandkids to. The man who gave us Bad Boys and CSI has realized that there’s a market niche for the PG-rated action film. So we get an amiable romp that mixes together Freemasons, the Knights Templar, the Rosicrucians, Ben Franklin, and for all I know Judge Crater, Atlantis, and the Lindbergh baby.

My colleagues, students, and wife think I’m nuts to like National Treasure. In defense I could point to evocative images like the one surmounting today’s entry, the superimposition of Grandpa Gates’ eye on a pyramid as a condensation of the Masonic/ monetary/ paternity motifs swarming through the movie. But I needn’t strain so far. The pleasures are more elemental.

Secret codes, knights, lost treasure, rich sinister Brits, really deep holes filled with cobwebs, and a cipher on the back of the Declaration of Independence—what’s not to like? All of this is pulled together by a hero who is actually intelligent and knowledgeable. He’s a nerdy patriot (another Bruckheimer touch, reminiscent of The Rock) who can turn a priceless hoard over to the US government without a quiver. How often do you find a story whose protagonists are people who know and care about the past? In the DVD supplement, an alternative ending shows schoolboys eyeing the recovered Declaration. One wonders if there’s really a treasure map on the back. The other mutters, “It’s a plot to make us learn history.” What if he is right?

Of course some will say Spielberg/ Lucas/ Kasdan did it already with Raiders. But that was a knowing effort to relive somebody’s phantom vision of B serials. Besides, does anybody believe that Indy knows as much about archaeology as Ben Gates does about nearly everything? If it recycles anything, National Treasure amounts to a revival of the wholesome 1950s Disney adventure movie. What Treasure Island (1950), Davy Crockett (1955), and The Great Locomotive Chase (1956) were for an earlier generation, National Treasure is for today’s twelve-year-olds. It compares favorably with those entries in verve, wit, and speed. (How it gets that speed is a topic I take up in “The Hook,” a new online essay. That piece tries to show that even if you don’t like the movie, its narration provides a nifty tutorial in some strategies of Hollywood storytelling.) My only regret is that in the epilogue NT 1 actually uses, Ben and Abigail are given a mansion and Riley gets a cherry-colored Ferrari. That’s a bit crass. Knowledge, selflessness, and pluck should be their own rewards.

Your correspondent regrets to report that Book of Secrets is not up to its predecessor. It’s still quite entertaining, and it has some transitions as clever as those I talk about in the aforementioned essay. The premise, involving the Lincoln assassination and the besmirched reputation of Ben’s ancestor, is workable and even moving, grounded as it is in parallel father-son reconciliations. The clue-sequences are more ingenious than, say, the simple linear connectives in Bourne Ultimatum. There are a few nifty compositions (e.g., a reflection of Ben in a windshield) and some nicely-timed reaction shots of Riley and Ben’s dad. (Someday, I swear, I will blog about reaction shots, a key to Hollywood storytelling.) I liked the way that the slapped-together family of the first installment—Dad Ben, Mom Abigail, Riley the kid—is expanded to include the old folks. Of course I regard the rekindled affection between Ben’s father and mother as backup for my Grandparents-Grandkids Hypothesis.