Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

Bwana Beowulf

KT: I do not understand Beowulf. I don’t understand why the director who made one of the great modern Hollywood films, Back to the Future, and several very good ones, including Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and Cast Away, now has this fixation with creating nearly photo-realistic 3D digital images.

DB: I think that on the whole Zemeckis’ films have become weaker since Bob Gale stopped working with him. I like the sentiment of I Wanna Hold Your Hand and the crass misanthropy of Used Cars, and I think the Back to the Future trilogy mixes both in clever ways. But now almost every Zemeckis film seems to be less about telling a story than solving a technical problem. How to best merge cartoons and humans (Roger Rabbit)? How to push the edge of spfx (Death Becomes Her, Forrest Gump, Contact)? How to make half a movie showing only one character (Cast Away)? There’s a stunting aspect to this line of work, though I grant that it can lead to technical breakthroughs, as in Gump.

KT: I also don’t understand why most of the supposedly state-of-the-art effects technology looks distinctly cruder than the CGI in The Lord of the Rings, the first part of which came out six years ago. I don’t understand why studios that are trying to push 3D to a broad audience make a film with silly action aimed at teenage boys. That’s an OK strategy when you’ve got a $30 million horror film, but a budget of $150 million demands a lot broader appeal.

DB: And the evidence so far indicates Beowulf doesn’t have that appeal. The obvious comparison is 300, from earlier this year. According to Box Office Mojo it cost about $65 million to make, but it reaped $70 million domestically in its first weekend and wound up with $450 million theatrically worldwide. Beowulf grossed $27.5 million in its first US weekend and currently sits at about $146 million worldwide. I’d think that this has to be a disappointment. Recall too that the Imax screenings have higher ticket prices, so there are fewer eyeballs taking in Angelina Jolie’s pumps, braid, and upper respiratory area.

In addition, sources suggest that a 3-D version of Beowulf will not be available on DVD, so the sell-through takings—the real source of studio profit—may be significantly smaller than average.

KT: It seems to me that the people who are pushing 3-D so hard and hoping for it to become standard in filmmaking are forcing it on the public too soon. It’s still fiendishly difficult and expensive to shoot live action material in digital 3-D, so most projects are animated. One approach, taken in Beowulf, is to motion-capture real people and animate the characters to make them appear as much like the real people as possible. The problem is that they still have a weird look about them, like moving dolls. People have complained about the dead-eyed gaze of the characters in The Polar Express, and though there’s apparently been an improvement between the two films, the eyes don’t always look as though they’re focusing on anything. It can be done, though; the extended-edition Lord of the Rings DVD supplements about Gollum show how much effort went into making his eyes have a realistic sheen and flicker.

I was also struck by how clunky some of the animation looked. Beowulf is supposedly state of the art, and it certainly had the budget of a major CGI film. Yet some of the rendering and motion-capture was distractingly crude. I noticed that particularly on the horses. Their coats looked pre-Monsters, Inc., and their movements at times reminded me of kids rocking plastic toys back and forth. I suspect this effect had something to do with a lack of believable musculature. If you look at the way the cave troll was done in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (again, demonstrated in the DVD supplements), there was a specific program to simulate the way muscles move on skeletons, even the skeletons of imaginary creatures. Now, six years later, we see these things that look like hobby-horses—and that all run alike.

The backgrounds were often strange as well, simple and flat-looking, like painted backdrops. There were some exceptions, with the seascapes and rocky crags pretty realistically done. But just plain hillsides and groups of tents and so on looked almost sketchy in comparison with the moving figures, and I noticed that at times some fog would be put in, presumably to cover that problem up. There certainly was some very good animation as well, most notably the dragon, but there was no consistency of visual style.

DB: I’d go farther and say that 3-D hasn’t improved significantly since the 1950s. It ought to work: just replicate the eyes’ binocular disparity by setting two cameras at the proper interval or, now, by manipulating perspective with software. Yet in films 3-D has always looked weirdly wrong. It creates a cardboardy effect, capturing surfaces but not volumes. Real objects in depth have bulk, but in these movies, objects are just thin planes, slices of space set at different distances from us. If our ancestors had seen the world the way it looks in these movies, they probably wouldn’t have left many descendants.

It would take a perceptual psychologist to explain why 3-D looks fake. Whatever the cause, I’d speculate that good old 2-D cinema is better at suggesting volumes exactly because the cues to depth are less specific and so we can fill in the somewhat ambiguous array.

By the way, in watching a 3-D movie I seem to go through stages. First, there’s some adjustment to this very weird stimulus: I can’t easily focus on the whole image and movement seems excessively fuzzy. Then adaptation settles in and I can see the 2 ¼-D image pretty well. But adaptation carries me further and by the end of the movie I seem to see the image as less dimensional and more simply 2-D; the effects aren’t as striking. But maybe this is just me.

Back to the Future, or at least 1954

DB: I’d like to think about it from a historical perspective for a while. The industry seems to be repeating a cycle of efforts that took place in 1952-1954. The American box office plunged after 1947 as people strayed to other entertainments, including TV, and so the industry tried to woo them back with some new technology. Today, as viewers migrate to videogames, the Internet, and movies on portable devices, how can theatres woo their customers? Answer: Offer spectacle they can’t get at home.

Beowulf brings together at least three factors that eerily remind me of the early 1950s.

(1) Obviously, 3-D. The first successful 3-D feature era was Bwana Devil, released in November of 1952. It was an uninspired B movie, but it launched the brief 3-D craze. Columbia, Warners, and other studios made major pictures in the format, most notably House of Wax (1953). But costs of shooting and screening 3-D were high, with many technical glitches, and apart from novelty value, the process didn’t guarantee a big audience. The fad ended in spring of 1954, when all studios stopped making films in the format.

The process has been sporadically revived, notably in the 1980s (Comin’ at Ya, Jaws 3-D) and once more it fizzled. So, ignoring the lessons of history and chanting the mantra that Digital Changes Everything, we try it again.

(2) Big, big screens. In September of 1952, Cinerama burst on the scene with its huge tripartite screen and multitrack sound. It attracted plenty of viewers, but it could be used only in purpose-built venues. Like 3-D, its technology could never replace ordinary 35mm as the industry standard. The contemporary parallel is Imax, which though very impressive will not replace orthodox multiplex screens—too expensive to install and maintain, pricy tickets. Like 3-D, it’s a novelty. (1)

(3) The sword-and-sandal costume epic. It’s a long-running genre, but it got significantly revived in the late 1940s. It was a logical input for the new technologies of widescreen—not Cinerama but more practical offshoots that gained more general usage.

From the standard-format Samson and Delilah (1949), David and Bathsheba (1951), and Quo Vadis (1951) it was a short step to The Robe (1953) and The Egyptian (1954) in CinemaScope, The Ten Commandments (1956) in VistaVision, The Vikings (1958) in Technirama, Hercules (1959) in Dyaliscope, Solomon and Sheba (1959) and Spartacus (1960) in Super Technirama 70, and Ben-Hur (1959) in anamorphic 70mm Panavision. It is, incidentally, a pretty dire genre; the peplum might be the only genre that has given us no great films since Cabiria (1914) and Intolerance (1916).

In parallel fashion, the revival of the beefcake warrior film with Gladiator (2000) coincided with innovations in CGI and thus furnished new forms of spectacle for Troy (2004), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), and 300 (2007). This trend paved the way for Beowulf. When screens get bigger, Hollywood hankers for crowds, oiled biceps, big swords, and nubile ladies in filmy clothes. Not to mention soundtracks with pounding drums, wailing sopranos, and choirs chanting dead or made-up languages. And the conviction that Greeks, Romans, and those other ancient folks spoke with British accents. The innovation of Beowulf is to turn a Nordic hero into a Cockney pub brawler.

In other words, it’s 1954 again. So if we ask, Will it all last? I’m inclined to answer, Did 1954?

KT: Yes, the studios see the new technology as one more way to lure people away from their computers and game consoles and into the theaters. Maybe that will work to some extent. There’s no doubt that a lot of the people who have seen Beowulf have praised it as a fun experience and as having effectively immersive 3-D effects. I’m surprised at how many positive comments there are on Rotten Tomatoes, where the average score from both amateur and professional reviewers is 6.5 out of 10. That’s not exactly dazzling, but it’s a lot higher than I would give it.

Even so, the film hasn’t lured all that many people away from their other activities. You’ve mentioned that Beowulf hasn’t done all that well at the box-office. It did much better in theaters that showed it in 3-D. If it hadn’t been for the 3-D gimmickry, it would probably have been dead in the water from the start. And if 3-D effects remain on the level of gimmickry, they will soon wear out their welcome. Presumably the people who have been going to Beowulf are to a considerable extent those who are already interested in 3-D, and I can’t believe there are huge numbers of people really passionate about the idea of someday being able to watch lots of films in 3-D. If more films like Beowulf come out—ludicrous, bombastic action with distracting animation problems—they’re not likely to make the prospect any more attractive.

Eventually somebody—James Cameron or Peter Jackson, perhaps—will make the first great 3D film, and then maybe the passion will spread.

3-D in 2-D

DB: I’m doubtful that there will ever be a great 3-D film, and especially from those directors. But one last historical note.

I think that ordinary mainstream cinema has been setting us up for the flashiest 3-D flourishes for some time. One of the goals of the Speilberg-Lucas spearhead was to amp up physical action, to make it more kinetic, and this often showed up as in-your-face depth. Spielberg used a lot of deep-focus effects to create a punchy, almost comic-book look, and who can forget the opening shot of Star Wars, with that spacecraft arousing gasps by simply going on into depth forever? Seeing the movie in 70mm on release, I was struck by how the last sequence of Luke’s attack mission was maniacally concerned with driving our eye along the fast track of central perspective. Did it foreshadow the tunnel vision of videogame action?

In any case, I think that aggressive thrusting in and out of the frame was integral to the style of the new blockbuster. Since then, our eyes have been assaulted by plenty of would-be 3-D effects in 2-D. In Rennie Harlan’s Driven (2001), the crashing race cars spray us with fragments.

Jackson is definitely in the Spielberg line, favoring steep depth and big foreground elements. In King Kong, the primeval creatures lunge out at us, heave violently across the frame, and fling their victims into our laps.

Such shock-and-awe shots recall American comic-book graphics. These affinities are at the center of 300, as we’d expect. For example, a cracking whip curls out at us in slow motion, like a two-panel series.

Beowulf draws on this thrusting imagery, but inevitably it doesn’t seem fresh because so many 2-D films have already used it. Maybe the most original device is having the camera pull swiftly back and back and back, letting new layers of foreground pop in and shrink away. This is viscerally arousing in 3-D, but aren’t there precedents for it—in the Rings, in animated films, or some such?

Zemeckis tries to transpose into 3-D the style of what I’ve called, in The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity. This style favors rapid cutting, many close views, extreme lens lengths, and lots of camera movement. I found Zemeckis’ restless camerawork even more distracting than in 2-D. So I’m wondering if current stylistic conventions can simply be transposed to 3-D, or do directors have to be more imaginative and make fresher choices?

KT: That pull-back effect may be viscerally arousing, but in Beowulf it was usually pretty gratuitous and, for me at least, it called attention to itself in a way that was often risible. I don’t think there’s anything in Rings as crude as the shots in Beowulf that you’re talking about. In the opening scene of the latter, in the mead-hall, the camera zips into the upper part of the room, with rafters, chains, torches, and even rats whizzing in from the sides of the frame. None of that contributes to the narrative.

The flashiest backward camera movement, or simulated camera movement, I can think of in Rings is the one in the Two Towers scene where Saruman exhorts his army of ten thousand Uruk-hai to battle. The final shot is a rapid track backward through the ranks of soldiers holding flag poles. The point is to stress the enormous numbers of soldiers. There’s no gratuitous thrusting-in of set elements from the sides, just the cumulative effect of so many similar figures. The simulated camera also at one point “bumps” one of the flagpoles, causing it to wobble, but I take it that that’s an attempt to add a certain odd realism to the “camera” movement, not a knowing nudge to the audience. In Rings, the virtual camera usually follows action rather than moving independently through space. It tends to go forward or obliquely rather than backward.

As to transferring classical Hollywood style to 3-D or finding a whole new set of conventions to fit 3-D, Beowulf offers an object lesson. It uses a combination of the two. At times we have conventional conversations using shot/reverse shot, and at other times we have the swoopy-glidey style you described, with the camera zipping around the space and trying to see it from every angle within a few seconds.

The odd thing is, neither one works. The very close shot/reverse shot views of the digital characters make them look unnatural and emphasizes the not infrequent failure of their eyes to connect with each other. The swoop-glidey camera movements are silly and don’t stick to the narrative.

I’m not optimistic enough to think that directors can come up with a whole set of “fresher stylistic choices” to make 3-D work. Maybe Sergei Eisenstein, with his meticulous attention to every aspect of such topics, could have thought the issue through, but his solution would probably not be viable for the Hollywood studios. My own thought is that directors working in 3-D should probably stick to classical Hollywood style and avoid flashy stylistic effects. So far, the more blatantly 3-D something looks on the screen, the less it makes 3-D seem like something we want to watch on a regular basis. Think of the best films of this year: Zodiac, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Ratatouille, Across the Universe, and so on. Would any of them be better in 3-D? Probably not.

Plus, I don’t like watching movies through something. Movies should just be the screen and you. The 3-D glasses are definitely better now than in the earliest days of the cardboard, red/green versions. Still, the Imax glasses we used in watching Beowulf were heavy enough to leave a groove on my nose. Make the mistake of touching the lenses, and you’ve got a blur on one half of your vision of the film. In short, I think that 3-D still has to prove itself, and Beowulf didn’t add any evidence.

(1) PS 9 December: DB: I originally added in regard to Imax: “It’s actually waning in popularity, except in newly emerging markets like China.” This disparaging comment was misleading. Yesterday I learned from Screen International that Imax recently signed a deal with AMC to install 100 systems in 33 US cities. Oops! Today Paul Alvarado Dykstra of Austin’s Villa Muse Studios kindly wrote to point out the Hollywood Reporter‘s coverage, which gives background on the costs of installing and maintaining an Imax facility.

I was, obscurely, thinking of the traditional Imax programming of travelogues and documentaries. I failed to register that these have been largely displaced by screenings of blockbuster features, catching fire in 2003 with The Matrix Reloaded and proving successful with The Polar Express and other titles. Imax is now largely an alternative venue for megapictures, and its seesawing financial performance may have been steadied by moving into the features market.

PS 26 December: Travel has delayed our timely linking, but we couldn’t neglect Mike Barrier’s in-depth critique of Beowulf here.

PPS 5 January 2008: Harvey Deneroff has a comprehensive and judicious discussion of the 3D situation here.

You may own the night, but I’ve got a lien on midday

DB here:

Since I retired, I usually go to matinee shows. It’s cheaper, and the auditorium is depopulated. Sometimes I’m the only person there. I know, movies are supposed to be seen with a big audience; but I’ve seldom liked the experience of a packed house. Does the humble worshipper in the temple need a congregation to confirm his faith? Isn’t it best to commune with the deity alone? More to the point: Even before the advent of cellphones, somebody always coughs or talks at the wrong time.

If there are any other people around during my matinees, they are likely to be elderly folks, misfits, losers, idlers, and troublemakers. This makes me feel superior. But then I realize that to an objective observer, I could fit into any of those categories. Last time I went to my local, the cashier at the ticket stand gave me the Senior Citizens discount automatically. The pleasure of saving a dollar was small compensation for the blow to baby-boomer pride—sort of the reverse of being carded at a bar when you’re 30.

Curiously, as film attendance is dropping, multiplexes are offering more screenings. I enjoyed the idea of starting the screening cycle at noon or so, but now some ‘plexes start running as early as 10:30. At my neighborhood ‘plex, you can attend the Baby Box Office (“The lights are a little brighter, the sound a little softer”) on Tuesdays at 10:00 AM. It’s currently featuring the ideal picture for babes in arms, American Gangster.

Here are some jotted opinions on movies seen at midday over the last couple of weeks.

We Own the Night: I admired James Gray’s The Yards, but this seemed to me quite standard. One brother’s a cop, the other’s on the shady side: back to Warner Bros. of the 1930s. (Where’s the tough priest, though?) Although set in the 1980s, it looks a bit like a 1970s movie, with all those long-lens shots and flattened color values. The plot was by-the-numbers, and lines like “You’re a dead man” and “I love you very much” don’t help. I guess it’s a “personal” project for Phoenix and Wahlberg, both brave performers in other vehicles but mostly going through the motions here. Further evidence that today’s cinema is classic studio cinema, with more sex, violence, drugs, and rock-and-roll.

We Own the Night: I admired James Gray’s The Yards, but this seemed to me quite standard. One brother’s a cop, the other’s on the shady side: back to Warner Bros. of the 1930s. (Where’s the tough priest, though?) Although set in the 1980s, it looks a bit like a 1970s movie, with all those long-lens shots and flattened color values. The plot was by-the-numbers, and lines like “You’re a dead man” and “I love you very much” don’t help. I guess it’s a “personal” project for Phoenix and Wahlberg, both brave performers in other vehicles but mostly going through the motions here. Further evidence that today’s cinema is classic studio cinema, with more sex, violence, drugs, and rock-and-roll.

Gone Baby Gone: At least We Own the Night doesn’t promise to be more than a typical genre piece. For several years now, many ambitious or “prestige” pictures have given genres the uplift treatment, making them—well, serious. So a crime thriller that might have been trim at 90 minutes gets padded out to portentous dimensions, chiefly through scenery-gobbling performances and tricky narration. A recent model is The Departed, but Mystic River also worked this ground.

Such is Gone Baby Gone, another Lehane exercise in male pain in a gritty ethnic enclave. Director Ben Affleck shoots it in a standard way, with long-lens glimpses of homely people sitting on stoops (don’t get too close), and he resorts to the now-common device of flashbacks that fill us in on what really happened in a crucial scene. As usual in such fare, the plot is a pretext for Oscar-bait performances, and I confess that to my surprise I found Casey Affleck pretty riveting.

Michael Clayton: Another tricked-out genre effort, with echoes of Three Days of the Condor. Again a mystery plot is overlaid with a guy’s personal problems: divorce, druggy brother, loyalty to his mentor. (By the way, when is someone going to do a study of the hero’s weak friend in Hollywood cinema?) We get the fancy flashbacks as well, starting at a high point—an exploding car bomb, which ought to grab you—before a title pops up: “Four days earlier.” Eventually, as per usual nowadays, the opening scene is replayed, from a more omniscient point of vantage. And just as I have problems with any movie that resolves its plot with somebody writing a check, I don’t find it terribly original to settle things by secretly taping the bad guys admitting their chicanery. Yet I appreciated Paul Gilroy’s calm direction. I especially liked his crosscut sequences, in which the sound of one line of action plays out over images from the other line. This technique isn’t brand-new, but Gilroy handles these passages well, building story momentum while creating compact characterizing bits (e.g., the insecurity of lawyer Tilda Swinton faced with critical meetings).

Michael Clayton: Another tricked-out genre effort, with echoes of Three Days of the Condor. Again a mystery plot is overlaid with a guy’s personal problems: divorce, druggy brother, loyalty to his mentor. (By the way, when is someone going to do a study of the hero’s weak friend in Hollywood cinema?) We get the fancy flashbacks as well, starting at a high point—an exploding car bomb, which ought to grab you—before a title pops up: “Four days earlier.” Eventually, as per usual nowadays, the opening scene is replayed, from a more omniscient point of vantage. And just as I have problems with any movie that resolves its plot with somebody writing a check, I don’t find it terribly original to settle things by secretly taping the bad guys admitting their chicanery. Yet I appreciated Paul Gilroy’s calm direction. I especially liked his crosscut sequences, in which the sound of one line of action plays out over images from the other line. This technique isn’t brand-new, but Gilroy handles these passages well, building story momentum while creating compact characterizing bits (e.g., the insecurity of lawyer Tilda Swinton faced with critical meetings).

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford: The really successful fancy-pants genre film in my latest round of viewings. Andrew Dominik has made a grave, spare movie about the myth of Jesse and his murderer that doesn’t splash on period details and swamp the action in overproduced sets. The film could have been another funny-hats Western, but it turns out to be as austere as a sharecropper’s porch in a Walker Evans photograph. With an average shot length close to seven seconds, the film lets actors use their bodies a bit and interact within a fixed frame. In this context, the vignetted shots stand out, but not as mere flourishes; their wavery softness is picked up in the distorting windowpanes of the farmhouses and eventually in the fatal reflection in the picture Jesse is adjusting.

For once a post-Unforgiven western earns its meta-commentary on the Legends of the West. Jesse is the quietly charismatic star, while Ford is the overeager admirer, the outlaw as groupie. Daringly, the plot wanders away from its main characters for considerable stretches, and the protracted dialogues feature archaic turns of speech that can become ominous. Jesse is a raconteur whose paranoia can unnerve anybody: “You got a tale to swap with me now?” Assassination also reminded me of Magnolia in the dry authority of its voice-over narration and in its epilogue, which follows Ford to the end of his enigmatic life.

But where am I at the peak hours on Friday and Saturday, when throngs at the multiplex line up for popcorn, nachos and Dots? At our cozy Cinematheque, where we screen dazzling items like Nouvelle Vague and Utamaro and His Five Women. Right now, Godard and Mizoguchi own my nights.

Legacies

DB here:

By now James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma has had its critics’ screenings and sneak previews. It’s due to open this weekend. The reviews are already in, and they’re very admiring.

Back in June, I saw an early version as a guest of the filmmaker and I visited a mixing session, which I chronicled in another entry. I was reluctant to write about the film in the sort of detail I like, because I wasn’t seeing the absolutely final version and because it would involve giving away a lot of the plot.

I still won’t offer you an orthodox review of the film, which I look forward to seeing this weekend in its final theatrical form. Instead, I’ll use the film’s release as an occasion to reflect on Mangold’s work, on his approach to filmmaking, and on some general issues about contemporary Hollywood.

An intimidating legacy

It seems to me that one problem facing contemporary American filmmakers is their overwhelming awareness of the legacy of the classic studio era. They suffer from belatedness. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that this is a relatively recent development, and it offers an important clue to why today’s ambitious US cinema looks and sounds as it does.

In the classic years, there was asymmetrical information among film professionals. Filmmakers outside the US were very aware of Hollywood cinema because of the industry’s global reach. French and German filmmakers could easily watch what American cinema was up to. Soviet filmmakers studied Hollywood imports, as did Japanese directors and screenwriters. Ozu knew the work of Chaplin, Lubitsch, and Lloyd, and he greatly admired John Ford. But US filmmakers were largely ignorant of or indifferent to foreign cinemas. True, a handful of influential films like Variety (1925) and Potemkin (1925) made an impact on Hollywood, but with the coming of sound and World War II, Hollywood filmmakers were cut off from foreign influences almost completely. I doubt that Lubitsch or Ford ever heard of Ozu.

Moreover, US directors didn’t have access to their own tradition. Before television and video, it was very difficult to see old American films anywhere. A few revival houses might play older titles, but even the Museum of Modern Art didn’t afford aspiring film directors a chance to immerse themselves in the Hollywood tradition. Orson Welles was considered unusual when he prepared for Citizen Kane by studying Stagecoach. Did Ford or Curtiz or Minnelli even rewatch their own films?

With no broad or consistent access to their own film heritage, American directors from the 1920s to the 1960s relied on their ingrained craft habits. What they took from others was so thoroughly assimilated, so deep in their bones, that it posed no problems of rivalry or influence. The homage or pastiche was largely unknown. It took a rare director like Preston Sturges to pay somewhat caustic respects to Hollywood’s past by casting Harold Lloyd in Mad Wednesday (1947), which begins with a clip from The Freshman. (So Soderbergh’s use of Poor Cow in The Limey has at least one predecessor.)

Things changed for directors who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s. Studios sold their back libraries to TV, and so from 1954 on, you could see classics in syndication and network broadcast. New Yorkers could steep themselves in classic films on WOR’s Million-Dollar Movie, which sometimes ran the same title five nights in a row. There were also campus film societies and in the major cities a few repertory cinemas. The Scorsese generation grew up feeding at this banquet table of classic cinema.

In the following years, cable television, videocassettes, and eventually DVDs made even more of the American cinema’s heritage easily available. We take it for granted that we can sit down and gorge ourselves on Astaire-Rogers musicals or B-horror movies whenever we want. Granted, significant areas of film history are still terra incognita, and silent cinema, documentary, and the avant-garde are poorly served on home video. Nonetheless, we can explore Hollywood’s genres, styles, periods, and filmmakers’ work more thoroughly than ever before. Since the 1970s, the young American filmmaker faces a new sort of challenge: Now fully aware of a great tradition, how can one keep from being awed and paralyzed by it? How can a filmmaker do something original?

I don’t suggest that filmmakers have decided their course with cold calculation. More likely, their temperaments and circumstances will spontaneously push them in several different directions. Some directors, notably Peckinpah and Altman, tried to criticize the Hollywood tradition. Most tried simply to sustain it, playing by the rules but updating the look and feel to contemporary tastes. This is what we find in today’s romantic comedy, teenage comedy, horror film, action picture, and other programmers.

More ambitious filmmakers have tried to extend and deepen the tradition. The chief example I offer in The Way is Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire, but this strategy also informs The Godfather, American Graffiti, Jaws, and many other movies we value. I also think that new story formats like network narratives and richly-realized story worlds have become creative extensions of the possibilities latent in classical filmmaking.

James Mangold’s career, from Heavy onward, follows this option, though with little fanfare. He avoids knowingness. He doesn’t fill his movies with in-jokes, citations, or homages. Instead, he shows the continuity between one vein of classical cinema and one strength of indie film by concentrating on character development and nuances of performance. In an industry that demands one-liners and catch-phrases sprinkled through a script, Mangold offers the mature appeal of writing grounded in psychological revelation. In a cinema that valorizes the one-sheet and special effects and directorial flourishes, he begins by collaborating with his actors. He is, we might say, following in the steps of Elia Kazan and George Cukor.

Sandy

By his own account, Mangold awakened to these strengths during his formative years at Cal Arts, where he studied with Alexander Mackendrick. Mackendrick directed some of the best British films of the 1940s and 1950s, but today he is best known for Sweet Smell of Success.

Seeing it again, I was struck by the ways that it looks toward today’s independent cinema. It offers a stinging portrait of what we’d now call infotainment, showing how a venal publicist curries favor with a monstrously powerful gossip columnist. It’s not hard to recognize a Broadway version of our own mediascape, in which Larry King, Oprah, and tmz.com anoint celebrities and publicists besiege them for airtime. While at times the dialogue gets a little didactic (Clifford Odets did the screenplay), the plotting is superb. Across a night, a day, and another night, intricate schemes of humiliation and aggression play out in machine-gun talk and dizzying mind games. It’s like a Ben Jonson play updated to Times Square, where greed and malice have swollen to grandiose proportions, and shysters run their spite and bravado on sheer cutthroat adrenalin.

Sweet Smell was shot in Manhattan, and James Wong Howe innovated with his voluptuous location cinematography. “I love this dirty city,” one character says, and Wong Howe makes us love it too, especially at night.

Today major stars use indie projects to break with their official personas, and the same thing happens in Mackendrick’s film. Burt Lancaster, who had played flawed but honorable heroes, portrayed the columnist J. J. Hunsecker with savage relish. “My right hand hasn’t seen my left hand in thirty years,” he remarks. Tony Curtis, who would go on to become a fine light comedian, plays Sidney Falco as a baby-faced predator, what Hunsecker calls “a cookie full of arsenic.” Falco is sunk in petty corruption, ready to trade his girlfriend’s sexual favors for a notice in a hack’s column. Hunsecker and Falco, host and parasite, dominator and instrument, are inherently at odds, then in a breathtaking scene they double-team to break the will of a decent young couple. There are no heroes. Nor, as Mangold points out in his Afterword to the published screenplay, do we find any of that “redemption” that today’s producers demand in order to brighten a bleak story line.

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.

Mangold became a willing apprentice to Mackendrick. “He taught me more craft than I could articulate, but beyond that, he showed me how hard one had to work to make even a decent film.” (1) Mangold’s afterword to the Sweet Smell screenplay offers a precise dissection of the first twenty minutes. He shows how the script and Mackendrick’s direction prepare us for Hunsecker’s entrance with the utmost economy. Mangold traces out how five of Mackendrick’s dramaturgical rules, such as “A character who is intelligent and dramatically interesting THINKS AHEAD,” are obeyed in the film’s first few minutes. The result is a taut character-driven drama, operating securely within Hollywood construction while opening up a sewer in a very un-Hollywood way. Surely Sandy Mackendrick’s boldness helped Mangold find his own way among the choices available to his generation.

Movies for grownups

Mangold has often mentioned his love for classic Westerns; on the DVD commentary for Cop Land he admits that he wanted it to blend the western with the modern crime film. But why Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma?

The Searchers, Rio Bravo, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance were objects of veneration for directors of the Bogdanovich/ Scorsese/ Walter Hill generation, while Yuma seemed to be a more run-of-the-mill programmer. To American critics in the grips of the auteur theory, Delmer Daves sat low in the canon, and Glenn Ford and Van Heflin offered little of the star wattage yielded by John Wayne, James Stewart, and Dean Martin. In retrospect, though, I think that you can see what led Mangold to admire the movie.

For one thing, it’s a close-quarters personal drama. It doesn’t try for the mythic resonance of Shane or The Searchers or Liberty Valance, and it doesn’t relax into male camaraderie as Rio Bravo does. The early Yuma simply pits two sharply different men against one another. Ben Wade is a robber and killer who is so self-assured that he can afford to be courteous and gentle on nearly every occasion. Dan Evans is a farmer so beaten down by bad weather, bad luck, and loss of faith in himself that he takes the job of escorting the killer to the train depot.

That dark glower that made Glenn Ford perfect for Gilda and The Big Heat slips easily into the soft-spoken arrogance of Wade. His self-assurance makes it easy for him to play on all of Evans’ doubts and anxieties. In counterpoint, Van Heflin gives us a man wracked by inadequacy and desperation; his flashes of aggression only betray his fears. In the end, his courage is born not of self-confidence but of sheer doggedness and a dose of aggrieved envy. He has taken a job, he needs the money to provide for his family, and, at bottom, it’s not right that a man like Wade should flourish while Evans and his kind scrape by. As in Sweet Smell of Success, the drama is chiefly psychological rather than physical, and the protagonist is far from perfect.

Daves shows the struggle without cinematic flourishes, in staging and shooting as terse as the prose in Elmore Leonard’s original story. Deep-focus images and dynamic compositions maintain psychological pressure, and as ever in Hollywood films, undercurrents are traced in postures and looks, as when Wade in effect takes over Evans’ role as father at the dinner table.

One more factor, a more subliminal one, may have attracted Mangold to Daves’ western. 3:10 to Yuma was released in 1957, about two months after Sweet Smell of Success. Both belong to a broader trend toward self-consciously mature drama in American movies. Faced with dwindling audiences, more filmmakers were taking chances, embracing independent and/or East Coast production, and offering an alternative to teenpix and all-family fare. 1957 is the year of Bachelor Party, Twelve Angry Men, Edge of the City, A Face in the Crowd, The Garment Jungle, A Hatful of Rain, The Joker Is Wild, Mister Cory (also with Tony Curtis), No Down Payment, Pal Joey, Paths of Glory, Peyton Place, Run of the Arrow, The Strange One, The Tarnished Angels, The Three Faces of Eve, Twelve Angry Men, and The Wayward Bus. These films and others featured loose women, heroes who are heels, and “adult themes” like racial prejudice, rape, drug addiction, prostitution, militarism, political corruption, suburban anomie, and media hucksterism. (Who says the 1950s were an era of cozy Republican values and Leave It to Beaver morality?) Today many of these films look strained and overbearing, but they created a climate that could accept the doggedly unheroic Evans and the proudly antiheroic Sidney Falco.

3:10 x 2

Mangold’s remake is a re-imagining of Daves’ film, more raw and unsparing. Both films give us the journey to town and a period of waiting in a hotel room. In the original, Daves treats the sequences in the hotel room as a chamber play. Each of Wade’s feints and thrusts gets a rise out of Evans until they’re finally forced onto the street to meet Wade’s gang and the train. Mangold has instead expanded the journey to the railway station, fleshing out the characters (especially Wade’s psychotic sidekick) and introducing new ones. This leaves less space for the hotel room scenes, which are I think the heart of Daves’ film.

At the level of imagery, the new version is firmly contemporary. The west is granitic; men are grizzled and weatherbeaten. When Wade and Evans get into the hotel room, Daves’ low-angle deep-focus compositions are replaced by the sort of brief singles that are common today. As in all Mangold’s work, minute shifts in eye behavior deepen the implications of the dialogue.

Similarly, the cutting, the speediest of any Mangold film, is in tune with contemporary pacing. At an average of 3 seconds per shot, it moves at twice the tempo of Daves’ original. Mangold has been reluctant to define himself by a self-conscious pictorial style. “I think writer-directors have less of a need sometimes to put a kind of obvious visual signature over and over again on their movies . . . . I don’t need to go through this kind of conscious effort to become the director who only uses 500mm lenses.” (2)

Mangold puts his trust in well-carpentered drama and nuanced performances. Daves begins his Yuma with Wade’s holdup of a stage, linking his movie to hallowed Western conventions, but Mangold anchors his drama in the family. His film begins and ends with Evans’ son Bill, who’s first shown reading a dime novel. We soon see his father, already tense and hollowed-out. At the end Mangold gives us a resolution that is more plausible than that of Leonard’s original or Daves’ version. What the new version loses by letting Evans’ wife Alice drop out of the plot it gains by shifting the dramatic weight to Bill in the final moments. The conclusion is drastically altered from the original, and it shocked me. But given Mangold’s admiration for the shadowlands of Sweet Smell, it makes sense.

In an interview Mangold remarks that Mackendrick distrusted film school because it stressed camera technique and didn’t prepare directors to work with actors. “It’s a giant distraction in film schools that in a way, by avoiding the world of the actor, young filmmakers are avoiding the most central relationship of their lives in the workplace.” (3) As we’d expect from Mangold’s other films, the central performances teem with details. Bale cuts up Crowe’s beefsteak, and Crowe gestures delicately with his manacles when he softly demands that the fat be trimmed. Bale’s gaunt, limping Evans, a Civil War casualty, becomes an almost spectral presence; his burning glances reveal a man oddly propelled into bravery by his failures. Crowe’s Ben Wade, for all his intelligence and jauntiness, is oddly unnerved by this farmer’s haunted demeanor. Actors and students of performance will be kept busy for years studying the two films and the way they illustrate different conceptions of the characters and the changes within mainstream cinema.

Sometimes I think that Hollywood’s motto is Tell simple stories with complex emotions. The classic studio tradition found elemental situations and used film technique and great performers to make sure that the plot was always clear. Yet this simplicity harbored a turbulent mixture of contrasting feelings, different registers and resonances, motifs invested with associations, sudden shifts between sentiment and humor. In his commitment to vivid storytelling and psychological nuances, Mangold has found a vigorous way to keep this tradition alive. Sandy would have been proud.

(1) James Mangold, “Afterword,” Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman, Sweet Smell of Success (London: Faber, 1998), 165.

(2) Quoted in Stephan Littger, The Director’s Cut: Picturing Hollywood in the 21st Century (New York: Continuum, 2006), 317.

(3) Quoted in Littger, 313.

PS 9 Sept: Susan King’s article in the Los Angeles Times explains that Mangold first got acquainted with Daves’ film in Mackendrick’s class. “We would break down the dramatic structure of the film. This one really got under my skin, partly because it always really moved me. It also felt original in scope in that it was very claustrophobic and character-based.” King’s article gives valuable background on the difficulties of getting the film produced.

Unsteadicam chronicles

DB again:

A spectre is haunting contemporary cinema: the shaky shot.

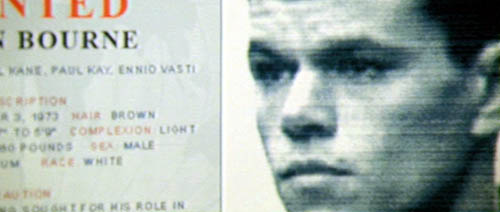

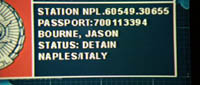

Viewers have been protesting for some years now. I recall friends asking me why the images were so bumpy in Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives and Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark. The Bourne Ultimatum, this summer’s wildest excursion into Unsteadicam, has put the matter back on the agenda.

If you drop in at Roger Ebert’s website, you’ll find many annoyed comments from readers about what one calls the Queasicam. The writers make shrewd points about the purpose and effects of director Paul Greengrass’s technique. I’ll try to add some historical perspective and a little analysis.

From whose Bourne no traveling shot returneth

First, what exactly are we talking about? Some viewers and critics think the jarring quality of the movie proceeds from rapid editing. The cutting in Bourne Ultimatum is indeed very fast; there are about 3200 shots in 105 minutes, yielding an average of about 2 seconds per shot. But there are other fast-cut films that don’t yield the same dizzy effects, such as Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (1.6 seconds average), Batman Begins (1.9 seconds), Idiocracy (1.9 seconds), and the Transporter movies (less than 2 seconds).

As for the series itself, The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, was edited a tad slower, averaging 3 seconds per shot. The second entry, The Bourne Supremacy, also signed by Greengrass, was as fast-cut as this, coming in at 1.9 seconds. People noticed the rough texture of the second one, but it didn’t arouse the protests that this last installment does. Something else is up.

Partly, it’s not the pace of the editing but the spasmodic quality of it. Cuts here seem abrasive because they interrupt actions and camera movements. Pans, zooms, and movements of the actors are seldom allowed to come to rest before the shot changes. This creates a strong sense of jerkiness and visual imbalance.

Still, a lot of the film’s effect has to be laid at the handheld camera. The technique in itself, however, shouldn’t shock us. The handheld aesthetic has been with us a long time. There were silent-era experiments with the technique by E. A. Dupont (Variety, 1925) and Abel Gance (Napoleon, 1927). It recurred sporadically after that, but in mainstream cinema handheld shooting became common in 1960s films as different as The Miracle Worker, Seven Days in May, Dr. Strangelove, and the dramas of John Cassavetes. Today, many films from Asia and Europe as well as the US rely on the device all the way through. The Danes call it the “free camera,” and I write about it here. The trend is so widespread that it’s been satirized: In the Danish comedy Clash of Egos (2006), when an ordinary workman gets a chance to direct a movie, he insists that the camera be put on a tripod, and the cinematographer complains that he hasn’t done this since film school. Directors nowadays tell us that they are in search of energy, a moment-by-moment spiking of audience interest. You can get it through fast cutting, arcing camera movements, sudden frame entrances, the nervousness of the handheld shot, or all of the above.

Roughhouse

I think the upsetting qualities of the visuals in The Bourne Ultimatum derive principally from the particular way the handheld camera is used. Several of Ebert’s writers complain that the camerawork made them nauseated, and there seems little doubt that the shots are bouncier and jerkier than in much handheld work. Adding to the effect is the fact that Greengrass often doesn’t try to center or contain the main action. Sometimes, as in a fight scene, the camera is just too close to the action to show everything, so it tries to grab what it can. At other times Greengrass pans away from the subject, or shoves it to the edge of the 2.40:1 frame. In the standard technique of over-the-shoulder reverse angles, we see one character’s shoulders in the foreground and the primary character’s face clearly. Greengrass likes to let a neck or shoulder overwhelm the composition as a dark mass, so that only a bit of the face, perhaps even just a single eye, is tucked into a corner of the shot. This visual idea was already on offer in The Bourne Supremacy.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I described contemporary films as employing “intensified continuity,” an amplification and exaggeration of tradition methods of staging, shooting, and cutting. (I explain a little about it in this blog entry.) What Greengrass has done is to roughen up intensified continuity, making its conventions a little less easy to take in. Normally, for instance, rack-focus smoothly guides our attention from one plane to another. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, when Jason bursts into a corridor close to the camera, the camera tries but fails to rack focus on his pursuer darting off in the distance. The man never comes into sharp focus. Likewise, most directors fill their scenes with close-ups, and so does Greengrass, but he lets the main figure bounce around the frame or go blurry or slip briefly out of view.

Essentially, intensified continuity is about using brief shots to maintain the audience’s interest but also making each shot yield a single point, a bit of information. Got it? On to the next shot. Greengrass’s camera technique makes the shot’s point a little harder to get at first sight. Instead of a glance, he gives us a glimpse.

Although this strategy is more aggressive in this third Bourne installment, we can find it as well in Supremacy. An agent pulls a document out of a carryon bag, and for an instant we can see the government seal. In the next shot the agent bobs in and out of the frame, as if the camera can’t anticipate his next move.

Later in Supremacy, the camera jerks across a computer display and suddenly focuses itself, evoking the jumpy saccadic flicks with which we scan our world.

Greengrass claims that his creative choices were influenced by the cinema-vérité documentary school and cites as well The Battle of Algiers, which helped popularize the handheld look in the 1960s. At other times he says that the style is subjective: “Your p.o.v. is limited to the eye of the character, instead of the camera being a godlike instrument choreographed to be in the right place at the right time.” But our point of view isn’t confined to what Bourne or anybody else sees and knows. The whole movie relies on crosscutting to create an omniscient awareness of various CIA maneuvers to trap him. And if Bourne saw his enemies in the flashes we get, he couldn’t wreck them so thoroughly.

The Bourne Ultimatum belongs to a trend of rough-edged stylization sometimes called run-and-gun. The film has been described as bare-bones but it’s actually quite flashy. All the crashing zooms (accompanied by whams on the soundtrack), jittery shots, drifting framings, uncompleted pans, freeze-frame flashbacks, and other extroverted devices call attention to themselves. You can find earlier instances in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and U-Turn, along with stretches in Michael Mann’s latest films. In milder form you find the style on display in TV crime shows, as well as in the notorious docudrama The Road to 9/11.

The most extreme practitioner of this style is probably Tony Scott. From Spy Game through Man on Fire, Domino, and Déjà vu, he has taken this aesthetic in delirious directions. His framing is often restless, as if groping for the right composition. In this shot from Domino, the camera starts a bit too far to the right, shifts left to frame Frances a little better, zooms back hesitantly, then finally stabilizes itself as he grins at the Motor Vehicles worker.

A single shot may give us not only changes of focus but jumps in exposure, lighting, and color; sometimes it’s hard to say whether we have one shot or several. The result is a series of visual jolts, as in Man on Fire.

Scott, trained as a painter, pushes toward a mannered, decorative abstraction, aided by long-lens compositions and a burning, high-contrast palette. For Supremacy, Greengrass adopted a toned-down version of Scott’s approach, while in Ultimatum, he favors drab surroundings and steely colors. Still, both men’s approaches to run-and-gun are frankly artificial, and both remain within the premises of intensified continuity. Of the Waterloo Station sequence Greengrass says: “It has got a sense of energy.”

The Bourne coverup

There’s one more function of Bourne’s style I want to consider. In an earlier post, I quoted Hong Kong cinematographers’ saying about the shaky camera. The handheld camera covers three mistakes: Bad acting, bad set design, and bad directing. It’s worth considering, as some of Ebert’s correspondents do, what Greengrass’s style may serve to camouflage. One suggests that because the cutting doesn’t let the viewer reconstruct the fights blow by blow, anybody can seem to be a superhero if the filming is flurried enough.

Just as important, the director who is just (apparently) snatching shots doesn’t have to worry about building up performances slowly; s/he can simply give us the most minimal, stereotyped signals in facial close-ups. Lengthier shots let the actor develop the character’s reactions in detail, and force us to follow them. Classic studio cinema, with its more distant framings and longer takes, lets you follow the evolution of a feeling or idea through the actor’s blocking and behavior. The villain in the average Charlie Chan movie displays more psychological continuity than the nasty agents in Bourne Ultimatum.

Moreover, run-and-gun technique doesn’t demand that you develop an ongoing sense of the figures within a spatial whole. The bodies, fragmented and smeared across the frame, don’t dwell within these locales. They exist in an architectural vacuum. In United 93, the technique could work because we’re all minimally familiar with the geography of a passenger jet. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, could anybody reconstruct any of these stations, streets, or apartment blocks on the strength of what we see? Of course, some will say, that’s the point. Jason himself is dizzyingly preoccupied by the immediacy of the action, and so are we. Yet Jason must know the layout in detail, if he’s able to pursue others and escape so efficiently. Moreover, we can justify any fuzziness in any piece of storytelling as reflecting a confused protagonist. This rationale puts us close to Poe’s suggestion that we shouldn’t confuse obscurity of expression with the expression of obscurity.

The run-and-gun style is indeed visceral, but let’s be aware of how it achieves its impact. I’ve argued in Planet Hong Kong that the clean, hard-edged technique of classic Hong Kong films allows extravagant action to affect us viscerally; by following the action effortlessly, we can feel its bodily impact. We’re shown bodies in sleek, efficient movement that gets amplified by cogent framing and smooth matches on action. But in the fancy run-and-gun style, cinematography and sound do most of the work. Instead of arousing us through kinetic figures, the film makes bouncy and blurry movement do the job. Rather than exciting us by what we see, Greengrass tries to arouse us by how he shows it. The resulting visual texture is so of a piece, so persistently hammering, that to give it flow and high points, Greengrass must rely on sound effects and music. As a friend points out, we understand that Bourne is wielding a razor at one point chiefly because we hear its whoosh.

What else does the handheld style conceal? Since the 1980s, in many action pictures the cutting has become so fast, and often capricious, that we can’t clearly see the physical action that’s being executed. That complaint is justified in Bourne Ultimatum, certainly, but here the style also seeks to make the stunts seem less preposterous. Instead of showing cars crashing and flipping balletically, Greengrass barely lets us see the crash. All the conventions of the action film are smudged in Bourne Identity, as if a sketchy rendering made them seem less outlandish. In a Hong Kong film, Bourne in striding flight, grabbing objects to use as weapons without missing a beat, would be presented crisply, showing him executing feats of resourceful grace. But many viewers seem to find this sort of choreography outlandish or cartoony. So when Bourne plucks up pieces of laundry and wraps them around his hands to protect them when he vaults a glass-strewn wall, Greengrass’s shot-snatching conceals the flamboyance of the stunt.

Finally, I’d argue that the style camouflages something else: plot problems. I’m not talking about the hero’s indestructibility, which is a given in this genre. John McClane in Die Hard 4.0 survives about as much mayhem as does Jason Bourne. But there are some howlers here that, because of the rapid pace and the just-barely-visible action, are somewhat muffled. By whisking the action past us and forcing us to keep up, the film doesn’t allow us to dwell on its holes and thin patches.

The plot, praised by so many, is actually a very simple one: Find Guy A, but when he’s killed, locate the clues that will lead you to Guy B, etc. until you get to Mr. Big. The mechanics of how the clues are pursued remain obscure. (Skip ahead to the next paragraph if you haven’t seen the movie.) Why would an all-powerful CIA operation house its key players in offices that can easily be watched from a neighboring building? How does Bourne get into Noah Vosen’s office, past all the security? Is the revelation of Bourne’s identity and his training regimen really much of a surprise? The wrapup, showing the bad guys exposed by the press and punished by government investigation, seemed risible, not only because of the current inability of either press or congress to right any wrongs, but because I had no idea to whom Pamela Landy has faxed the incriminating documents. “You can’t make stuff like this up,” remarks one sinister agency boss, but many, many films have done so.

I’m not against handheld styles as such, and even Late Tony Scott Rococo can have its virtues. Yet I find the style as practiced by Greengrass to be pretty incoherent and nowhere near as engaging as most critics claim. It just seems too easy. But then, I think that certain standards of filmmaking craftsmanship have pretty much vanished, and the run-and-gun trend is one more symptom of that. Given the praise heaped on The Bourne Ultimatum, however, things are unlikely to change. Next time you head to the movies, you might want to bring your Dramamine.

Thanks to Vance Kepley and Jeff Smith for engaging discussion about The Bourne Ultimatum.

The Bourne Supremacy.

PS: I’ve done a followup entry on the Bourne series, elaborating on these points and adding some new ones.

PPS: One more, I hope final, cluster of comments on Ultimatum, this time on the plotting.

PPPS 5 January 2008: Spielberg weighs in on the Bourne style; thanks to Fred Holliday and Brad Schauer for calling my attention to this.

PPPPS 22 September 2008: This blog post and its mates have stimulated critical discussion in Spain. Manuel Garin has a lengthy piece on the Unsteadicam style in Contrapicado.