Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

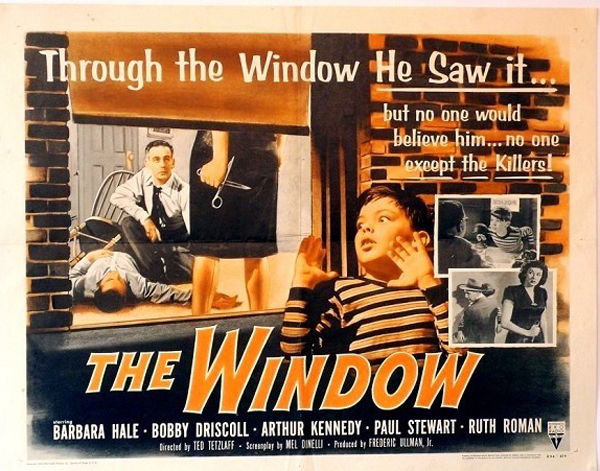

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

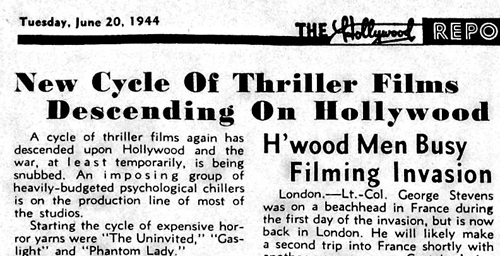

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

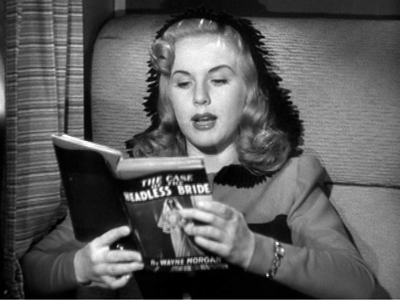

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

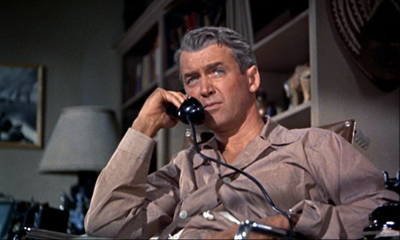

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

At the window, and outside it

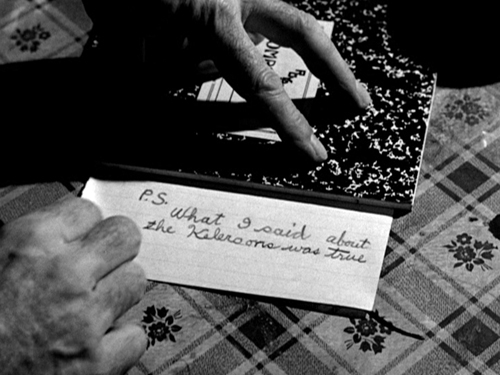

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

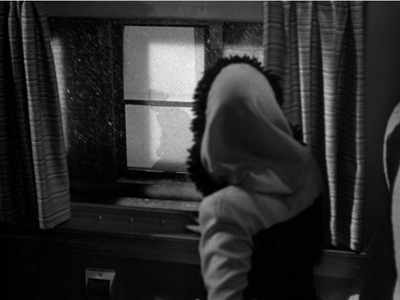

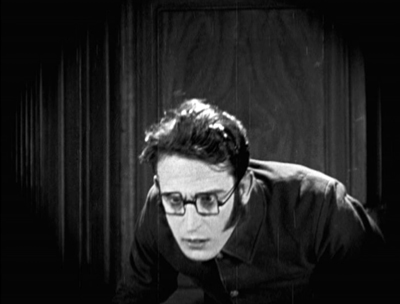

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

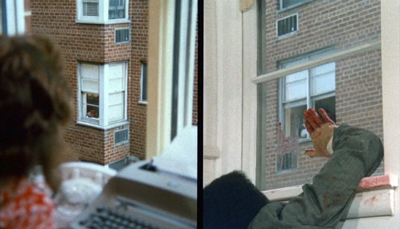

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

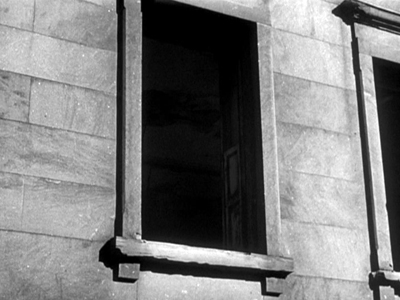

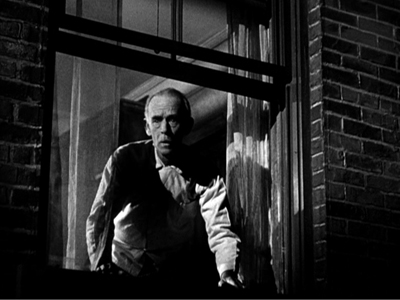

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.

Another motif is the vertical link between the two apartments, given in looming shots of the staircase (a common piece of iconography in 1940s cinema) and in cutting that links Tommy’s bedroom to the Kellersons above him. He listens to their footsteps through his ceiling.

The next layer up, the rooftop, serves as a route from the families’ building to the abandoned one, and eventually the chase will play out there.

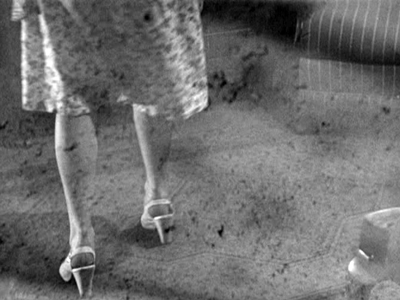

Vertical space more generally is important at the very start of the film. During Tommy’s mock ambush of his playmates, we look down over his shoulder. At the very end, Kellerson has trapped Tommy on the broken rafter.

The rooftop and rafter become part of another pattern, the circular one that rules the plot. Woolrich’s original story doesn’t feature the opening we have, showing Tommy in the abandoned tenement pretending to snipe at the other boys. Nor does the shooting script I’ve seen. Starting the film there establishes the locale of the climactic chase, while creating parallel scenes of Tommy hiding. We even get to see the broken rafter early on, when Tommy is prowling around his playmates.

The result is a pleasing, somewhat shocking symmetry of action: Tommy pretends to kill somebody at the start, and he succeeds in killing someone at the end.

The film offers a cluster of images that are recycled with variations, amplifying the basic story action through patterns of space and visual design.

The thickening of texture isn’t only pictorial. The drama of doubt involves a questioning of parental wisdom. Tommy’s mother actually endangers her boy by asking him to apologize to Mrs. Kellerson. More central is a testing of the father’s faith in his son. Tommy’s dilemma is to tell the truth even though he’ll be disbelieved by all the figures of social authority. The father’s increasingly desperate efforts to change Tommy’s story are revealed in Arthur Kennedy’s delicate portrayal of exasperation–at first gentle, then severe and nearly abusive.

Ed Woodry fails in his duty. The adults aren’t capable of protecting the child. A conventional plot would’ve had Ed redeem himself by rescuing his son, but the film we have leaves the killing to Tommy. It’s a grim condemnation of the people supposed to protect him.

Another convention, it seems, of the eyewitness film involves punishing the peeper. In Lady on a Train, Nicki has to brave a spooky house and risk death. Elaine of Shock suffers in the mental institution, and in Rear Window Jeff eventually falls from the very window that was his interface with the courtyard. Tommy, who acknowledges his inclination to tell whoppers, is subjected to a final burst of peril. After Kellerson has plunged to his death, Tommy is left in mid-air and he must jump to the firemen’s waiting net. In the epilogue, he announces that he’s learned his lesson, not least because of several brushes with death.

Revising the rules

The 1940s eyewitness cycle laid out some options for future thrillers. Rear Window, as we’ve seen, crystallizes the plot premise in rather pure form, and interestingly that was copied almost immediately in the Hong Kong film Rear Window (Hou chuang, 1955). Some passages are straight mimicry, albeit on a much smaller budget.

Thereafter, the eyewitness premise resurfaced, notably in Sisters (1973, with split screen) and with another child protagonist in The Client (1994).

In recent decades filmmakers have revised the premise in ways typical of post-Pulp-Fiction Hollywood. Vantage Point (2008) multiplies the eyewitnesses and uses replays to conceal and eventually reveal information. The Girl on the Train (2016), streamlining the multiple-viewpoint structure of the novel, alternates plotlines centered on three women. The novel and the film recast the eyewitness schema by making the eyewitness unable to recall exactly what she saw, thanks to an alcoholic blackout. (It’s a cousin to our old 1940s friend amnesia). This uncertainty raises the possibility that the eyewitness is actually the killer.

With its goal-directed protagonist and trim four-part plot structure, The Window is a completely classical film. As often happens, a forgivably flawed character gains our sympathy by being treated unfairly but triumphs in the end. And in the film’s integration of dramatic and pictorial elements, its alternation of subjectivity and wide-ranging narration for the sake of suspense, it nicely illustrates some ways in which 1940s filmmakers recast classical traditions for the thriller format and opened up new storytelling options.

Woolrich’s “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is available under the title “Fire Escape” in Dead Man Blues (Lippincott, 1948), published under the pseudonym William Irish. Woolrich, ever the formalist, initially gave “It Had to Be Murder”/”Rear Window” my dream title: “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” An earlier Woolrich story, “Wake Up with Death” from 1937, flips the viewpoint: A man emerges from drunken sleep to discover a murdered woman at his bedside and gets a call from someone who claims to have watched him commit the crime. Then there’s “Silhouette” from 1939, in which a couple witness a strangling projected on a window shade. See Francis M. Nevins, Jr.’s exhaustive Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (Mysterious Press, 1988), 158, 186, 245. There are doubtless many earlier eyewitness thrillers, which the indefatigable Mike Grost could tabulate.

The screenplay by Mel Dinelli that I consulted, with help from Kristin, is a rather detailed shooting script dated 23 October 1947. It is housed in the Dore Schary collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Dinelli benefited from the thriller boom in his screenplays for The Spiral Staircase, The Reckless Moment, House by the River, Cause for Alarm!, and Beware, My Lovely.

There are plenty of discussions of thrillers on this site; try here and here. Apart from the chapter in Reinventing Hollywood, you can find overviews here and here. See also the category 1940s Hollywood. I discuss the sort of plot fragmentation characteristic of some current Hollywood cinema, built on 1940s premises, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

For more images from my summer movie vacation, visit our Instagram page.

P.S. 24 July: Thanks very much to Bart Verbank for correcting my embarrassing name error in Rear Window! Also, if you’re wondering why I didn’t mention the very latest instantiation of the the eyewitness plot, A. J. Finn’s Woman in the Window, it’s because (a) I haven’t read it; and (b) I resist reading a book with a title swiped from a Fritz Lang movie.

DB accepts a fine Kriek from the Antwerp Summer Film College team: David Vanden Bossche, Tom Paulus, Lisa Colpaert, and Bart Versteirt.

Edgy color, trial testimony, and the world in unison: More movies at Ritrovato

The Woman under Oath (1919).

DB here:

Hard to keep up. Herewith, some highlights as Cinema Ritrovato, the Cannes of classic cinema, winds down.

Grease, still the word

Patricia Birch was a dancer with Martha Graham and Agnes De Mille. She went on to participate in West Side Story and to choreograph The Wild Party (1975) and both stage and film versions of A Little Night Music (1973, 1977). What brought her to Bologna was the restored version of Grease (1978). She choreographed that on both stage and screen, and she talked about it at a stimulating panel with Ehsan Khoshbakht and her son Peter Becker, of Criterion Films.

I had thought that Grease followed the vogue for boomer high-school nostalgia triggered by American Graffiti (1973), but it was actually ahead of that. The original Chicago version, reportedly raunchier than the New York version, premiered in 1971. It opened on Broadway in 1972 and ran until 1980. The film modified the stage show and added some songs.

Ms. Birch was a font of information about how she conceived the numbers. She says she thinks of dance as “timed behavior,” not set steps but patterns of motion. This idea allows her to choreograph actors who didn’t have dance training but who could “move well.” Peter ran a clip showing a passage of cascading hallway mischief that was as rhythmic as a dance number. This was one of several group-action scenes that Ms. Birch coordinated.

The Grease ensemble was huge, and Ms Birch organized it in a quasi-military way. There was a core of twenty proficient dancers, ten male-female couples. They supervised and coached the less skilled performers. For “We Go Together,” set in a carnival, each couple found business and steps for thirty other dancers.

“We Go Together” was the sort of big showstopper she called “Paramount numbers.” There were also the smaller-scaled “semi-Paramount numbers” and the intimate, character-driven “Internal numbers.” Ms Birch pointed out how the Paramounts built their power on unison steps and, eventually, massive kicklines. “People like to see the world in unison. Gets ’em every time.”

I learned a lot from Patricia Birch’s spirited discussion. Watch for a version of the panel to show up online.

Cutting edges

Film curator Olaf Müller set a new Ritrovato record: the shortest retrospective to date. Three films running less than twenty minutes introduced us to the oeuvre of Franz Schömbs.

Schömbs was a painter who became, according to Olaf, “probably the only avant-garde filmmaker of 1950s West Germany.” He started in the thirties by mounting paintings in rows, inviting viewers to walk along and sense the changes among them. After the war Schömbs tried to revive the experimentation of the Weimar period, principally through abstract films rich in color and design.

The films on the program were dense. Opuscula (1946-1952) consists of patches of color that slide to and fro “on top” of one another thanks to panning and tilting movements. The superimpositions create some striking visual hallucinations, as when blocks of white refuse to change color while other forms around them do. Die Geburt des Lichts (“The Birth of Light,” 1957, above), my favorite, transposes that constant movement to the patches of color themselves. These patches, as crisp as paper cutouts, have thrusting edges that keep slicing into the mates around them. Apparently Schömbs achieved the effect by applying paint to layers of glass and adjusting them frame by frame. Den Eisamen Allen (“To All the Lonely Ones,” 1962) uses what seemed to me traveling mattes, again enlivened by rich color.

Once more, Bologna proves a showcase for films that would otherwise go missing from film history.

Trial, with error

The courtroom drama was a mainstay of early twentieth-century theatre, but in 1915, playwright Elmer Rice gave it a twist. On Trial presented a murder trial by dramatizing the witnesses’ testimony in flashbacks. Rice offered another innovation as well: his flashbacks are non-chronological, starting with the most recent incident and reserving the climax for the earliest piece of action. Using the courtroom drama to play with time and viewpoint became a staple of American theatre and cinema.

Popular culture is a teeming mass of copies and near-copies–the switcheroo principle–so it didn’t take long for other storytellers to vary and complicate the trial format. One of the neatest examples was on display in Bologna. In the John Stahl silent drama The Woman under Oath (1919), flashbacks replay key actions according to what different witnesses know. We get no fewer than five flashbacks, some presenting incidents leading up to the crime, others recounting the murder itself. The later ones fill gaps in the earlier ones and culminate in a full, accurate version of the killing.

Proving once more that 1910s cinema can be pretty intricate, the same pieces of action get redeployed in different witnesses’ testimony. Sometimes the camera setups are varied to differentiate the versions.

At other moments, nearly identical framings mislead us by concealing important information. The young man accused of the murder is shown near the victim in three pieces of testimony, with the first two instances being essentially identical but the last presentation providing different information. (To avoid a spoiler, I don’t show the portion of the third shot that yields that information.)

The Woman under Oath shows a sophisticated understanding of how framing can conceal information without our being aware of it. And in retrospect what seems a colossal coincidence during the first presentation of the killing turns out to be a perfectly motivated key to the solution.

Switcheroos on the trial-testimony format showed up in other Ritrovato films. By 1928, the idea of conflicting testimony enacted in “lying” flashbacks was conventional enough to be parodied in René Clair’s Les Deux timides (“Two Timid Souls”). Here the disparities are wildly comic, accentuated by split-screen and freeze frame. Albert Valentin’s La Vie de Plaisir (1944), made under the German occupation of France, is an elegant social comedy pitting a couple against one another in divorce court. The spiteful witnesses offer testimony damning the husband only to get refuted in replays that reveal extra information. Throughout world cinema, the flashback trial film seems to have been one way oblique narrative strategies were made understandable for a wide audience.

Thanks as ever to Guy Borlée for assistance, and to the Ritrovato programmers for supplying so many treats. Thanks also to Kelley Conway for discussion of the courtroom movies. We should also be grateful to the BFI for providing Bologna with the copy of The Woman under Oath.

One rough precedent for Rice’s play is Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). The lingering awareness of Rice’s play is evident in Variety‘s review of The Woman under Oath, which the critic labeled “a sort of ‘On Trial’ affair” (20 June 1919, 52). In the same year there was an interesting parallel in the flashback testimony in Dreyer’s The President (1919).

You can find more about the switcheroo premise in my Reinventing Hollywood, which also discusses the trial format. For more on flashbacks see this entry. A series of entries on complex 1910s cinema start with this one.

P.S. 3 July 2018: Thanks to Peter Becker for a correction.

Les Deux timides (1928).

Who got played? A guest post by Jeff Smith on THE PLAYER

The Player (1992).

Jeff Smith, our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction just recorded an installment of our Observations on Film Art series for the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck. Here’s a supplement to that. –DB

In my installment, focusing on genre play in The Player, I discuss Robert Altman’s film in relation to two important traditions in Hollywood cinema: crime thrillers and films about filmmaking. As anyone who knows Altman’s other films would expect, The Player toys with the conventions of both genres in a number of different ways.

As I note in the video, The Player was received as something of a comeback film for Altman. It augured a resurgence in the director’s career that ultimately produced such late masterpieces as Short Cuts and Gosford Park.

Today, I sketch out some additional ideas about The Player’s use of genre conventions. I hope to shed light on some other connections to the crime thriller that I didn’t discuss in the video. I also hope to show just how unusual the film is in this context. Spoilers ahead, not only for The Player but for the novel and film of The Ax.

Will the real Griffin Mill please stand up?

In Reinventing Hollywood, David notes that there are usually four sorts of characters involved in a crime thriller plot: victims, lawbreakers, forces of justice, and more or less innocent bystanders. Filmmakers customarily organize the film’s narration around one or more of these character roles. Typically, a cascade of further choices flows from this initial decision about whose perspective forms the focal point of the story.

In The Player, much of the narration is restricted to the knowledge of the protagonist, Griffin Mill. The film includes a few scenes where Griffin is not present, like the one where the studio’s management awaits his arrival at a meeting. That, in itself, is not unusual. Many thrillers, like Chinatown or The Ghost Writer, employ similar tactics. What is slightly unusual is the fact Griffin takes on two of the typical character roles in the crime thriller as both victim and lawbreaker.

Griffin is a suit, and as a studio functionary he doesn’t immediately engender audience sympathy. Our first glimpse of Griffin shows him listening to pitch sessions. His questions to the people proposing new film projects are glib and capricious, representing the worst aspects of Hollywood commercialism.

Yet The Player does marshall some sympathy for Griffin as the victim of a stalker. Every time Griffin finds a postcard in his mail or on his car, it reminds us that he might be in mortal danger. After the stalker plants a venomous rattlesnake in Griffin’s passenger seat, we can’t believe the threats are empty.

Any sympathy that Griffin garners as a result of this psychological warfare is mollified, though, when the victim becomes victimizer. As Griffin later explains to June, his job is to tell people “no” more than a thousand times each year. Griffin believes that one of these rejections is the reason for the threatening postcards he receives. But he tragically miscalculates in targeting aspiring screenwriter David Kahane as the likely suspect.

Griffin contrives a meeting with Kahane at a Pasadena movie theater, and having bumped into him, tries to make amends. Yet Kahane recognizes that he is being pimped. This leads to a shouting match in a parking lot with Kahane threatening to ruin Griffin’s reputation. And when Kahane accidentally knocks Griffin over with his car door, Griffin reacts with rage, grabbing the screenwriter’s head and banging it repeatedly against the lot’s concrete surface. Although it seems clear that Griffin was acting on impulse, he’s nonetheless crossed a line that separates victims from perpetrators.

More importantly, Griffin’s violent action complicates the viewer’s allegiance to him. Altman establishes a dramatic context in which the motivations for Griffin’s crime seem completely understandable. Yet whatever sympathies viewers might have for Griffin are muddled by his creepy romantic interest in Kahane’s girlfriend; his cruel treatment of Bonnie, his current partner; and the general smarminess he exudes as a successful but shallow executive. Crime thrillers often ask audiences to sympathize with heels. There’s nothing that Griffin does that is inherently evil, but there’s nothing to really like. It’s less about his crime and more about his slime.

Griffin’s passage from victim to lawbreaker also alters the typical thriller plot. At the start of the film, Griffin himself functions as the investigative agent, trying desperately to figure out who is threatening him. Once Griffin becomes a suspect himself, though, that line of action halts, and the Pasadena police’s investigation of Kahane’s death springs up in its place.

This shift in the direction of the plot doesn’t really change the film’s pattern of narration. We remain as ignorant of the police’s activities as Griffin is. What does change are the stakes of the narrative. Instead of eliciting curiosity and suspense about Griffin’s stalker, we now wonder whether he’ll ever be brought to justice for Kahane’s death. Despite its strong connections and frequent allusions to crime fiction, The Player is not so much a whodunit as it is a will-he-get-away-with-it.

They smile in your face, all the time they want to take your place….

Besides blurring the boundaries between Griffin’s role as both victim and lawbreaker, The Player falls into a specific subgenre of crime fiction: the corporate thriller. Since, the corporate thriller is mostly defined by its setting, it blends pretty easily with the typical thriller plots and characters.

Like the spy thriller, the corporate thriller can focus on protagonists engaged in industrial espionage, as we see in Duplicity, Demon Lover, or Paycheck. Christopher Nolan’s Inception blends the plot mechanics of these corporate espionage thrillers with science fiction tropes to provide a narrative frame, but then embeds elements of the heist film within it.

Like the political thriller, the corporate thriller might also focus on the backroom deals and machinations that enable the protagonist to move up the company ladder. A film like Disclosure is a paradigm case. But even romantic comedies or prestige dramas can borrow elements from it. (Think Working Girl and Glengarry Glen Ross.)

More commonly, though, corporate thrillers feature elements drawn from the crime thriller. The roots of this approach to the genre stretch back a long way and can be found in both literary and cinematic antecedents. Some plots, for example, follow investigations that expose corporate malfeasance. Others focus on murders committed within a corporate environment, as in Dorothy Sayers’s novel Murder Must Advertise and Kenneth Fearing’s novel (and film) The Big Clock and in more modern instances like Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun and John Grisham’s The Firm. Other corporate crime thrillers, like Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (below) and Cindy Sherman’s Office Killer, involve serial murders in white-collar environments.

The corporate crime thriller enables writers and filmmakers to explore thematic parallels between the acts of brutality and violence committed by individuals and the cutthroat tactics employed by business institutions. The plots of many gangster films center on rival mobs battling for competitive dominance in black market trades. Such conflicts often seem like a logical extension of the laissez-faire principles that undergird capitalism. Corporate crime thrillers tread similar thematic territory. They sometimes suggest that the personality traits that make for good business executives and titans of industry are the same ones that produce sociopaths and serial killers.

The Player presents the familiar corporate-thriller rivalry, as Griffin works behind the scenes to outmaneuver Larry Levy. For example, Griffin momentarily ponders using Larry’s admission that he attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings as a way of embarrassing him within the company. Larry quickly undercuts this strategy, though, when he states that he just goes to the meetings because they are a great place to network.

Even more telling is Griffin’s efforts to saddle Larry with a loser project, Habeas Corpus. Midway through The Player, Griffin makes a deal with Andy Civella and Tom Oakley at a Los Angeles restaurant. The next day, he convinces his boss to greenlight the project with Larry as producer, knowing that Tom will likely prove difficult to work with and that his plan to use unknown actors has disaster written all over it. Larry, though, has the last laugh when we get a sneak peek of Habeas Corpus at film’s end. Not only does it have big stars in Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis. It also has the kind of happy ending that the pretentious Tom claimed was too Hollywood when he pitched the project. It turns out Tom cares more about the results of preview screenings than he does the purity of his artistic vision.

Not surprisingly, Altman doesn’t give us a wholly straightforward version of the corporate thriller. In a reflexive and ironic touch, Griffin’s successful ascent to studio boss seems to be secured by the same mysterious stalker who’d been taunting him at the start of the film. In a phone call, the stalker pitches Griffin the plot of the film we’ve just been watching, using his knowledge of Griffin’s crime to leverage his project into development. Here we see Altman slightly reframing the genre’s thesis about the relationship between crime and business. Griffin’s pact with his blackmailing stalker is simply a mildly illicit version of the sorts of quid pro quo arrangements upon which thousands of business deals are made.

If Griffin’s efforts to forestall a rival evoke the political thriller, then his killing of screenwriter David Kahane connects The Player to the corporate crime thriller. Once again, Altman deviates from some of the conventions. The crime doesn’t take place inside a corporate setting, as in Rising Sun and Murder Must Advertise. Griffin kills Kahane in the very public space of a Pasadena parking lot, with film noir overtones.

Similarly, Griffin’s victim is not a colleague, co-worker, subordinate, or client. Rather, Kahane is someone with whom Griffin has had minimal contact, a name plucked almost randomly from a directory of screenwriters in order to jog Griffin’s memory. Consequently, Griffin’s motives for confronting Kahane seem quite different from the culprits in other corporate crime thrillers. More often than not, the murderers in these other stories fear job loss or try to silence others in an effort to cover up some smaller crime or bungled action. Griffin’s actions with Kahane spring from fear about threats to his physical well-being, not from threats to his continued employment. (The latter is Larry’s role.)

Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area.

Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area.

Like Altman, Westlake has some fun with his central conceit. Just as The Player includes faux film clips and rushes as a means of satirizing Hollywood production practices, The Ax incorporates fictional resumes that tweak jobseekers’ business-speak. What makes Westlake’s social criticism in The Ax so resonant, though, is the utter banality of Burke’s ambitions. He doesn’t aspire to the garish lifestyle we see displayed by Tony Montana or Jordan Belfort in Scarface and The Wolf of Wall Street respectively. Instead Burke just wants to return to his modest middle-class lifestyle and to the dignity that a decent job afforded him. Serial murder just seems like the simplest way to achieve that.

As this comparison suggests, one of the things that makes The Player somewhat unusual as a corporate crime thriller is its play with character motivation and point of view. Facing threats and intimidation, Griffin looks more like the target of a crime than a perpetrator. In corporate thrillers, the lawbreaker is more likely to be somewhere in the middle of the corporate ladder, like Burke, than at the top of it. Moreover, although his actions are motivated by a strange combination of both vanity and insecurity, Griffin more or less stumbles into the crime he commits rather than coolly plotting it the way Burke does.

Despite these differences, The Player and The Ax share an important feature that markedly deviates from the crime thriller as a whole. Both Griffin and Burke get away with it. The plots of most crime thrillers resolve in ways that balance the scales of justice. The bad guys are usually either arrested or killed after climactic confrontations with law enforcement. But this doesn’t always happen. Burke, Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, and Dorine in Office Killer escape punishment. Even though Jordan Belfort is arrested in The Wolf of Wall Street, he gets a slap on the wrist for his crimes.

Perhaps this aspect of the corporate crime thriller reflects the cynicism and amorality that pervades the genre. After all, if your belief is that most corporations get away with murder in a figurative sense, then it’s not hard to accept this idea when it occurs in fictional contexts in a literal sense.

Still, in the case of The Player, the Pasadena police’s failure to prove their case against Griffin Mill may reflect a meshing of both authorial and generic tendencies. When Griffin embraces June in the stylized happy ending of The Player, it quite deliberately parallels the tacked on happy ending of Habeas Corpus we’ve seen just moments earlier. The dialogue Griffin exchanges with June amplifies the similarity between these scenes. When June asks, “What took you so long?”, Griffin responds, “Traffic was a bitch.” These are the exact same lines exchanged by Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis in Habeas Corpus. By allowing Griffin to get away with it, The Player’s “up” ending sharpens Altman’s critique of Hollywood convention, and allows him to subvert the kinds of mainstream genre filmmaking he’s long detested.

Both allusive and elusive: Comparing The Player to Hollywood Story

One of the other topics I discuss in my video essay on The Player is the way the film pays homage to various aspects of Hollywood tradition. Much of this is bound up with its satire of commercial filmmaking. But it also strengthens the film’s relation to the crime thriller. Throughout The Player, Altman makes reference to Hollywood’s past in multiple ways. Celebrity cameos, film posters, and production stills populate the mise-en-scene. The characters also frequently mention older film titles in dialogue.

Perhaps the most interesting allusion in The Player involves a poster of Hollywood Story that hangs in Griffin’s office. The latter is a 1951 film noir directed by William Castle, who later became famous for his use of outrageous gimmicks in the production and promotion of horror films. For The Tingler, Castle supervised the installation of devices that would vibrate theater seats, anticipating today’s 4DX Theater Experience in places like Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and Orlando.

Hollywood Story dramatizes the efforts of film producer Larry O’Brien to develop a project around the unsolved murder of silent film director Franklin Ferrara. O’Brien hires one of Ferrara’s old scenarists to write the script. He also develops a close relationship with Sally Rousseau, the daughter of one of Ferrara’s biggest stars. Once the project is announced, O’Brien finds himself the target of an assassin’s bullet. He surmises that his assailant is trying to prevent the case from being reopened. And as Sally reminds O’Brien, he doesn’t have an ending to his movie is he can’t determine the killer’s identity. O’Brien, thus, sets out to solve the crime, bringing closure to one of the biggest scandals in Hollywood’s history. Hollywood Story offers an even better synthesis of The Player’s mixture of industry exposé and crime film story beats. O’Brien’s lone wolf investigation is treated as being a necessary stage of project development.

If the Franklin Ferrara story sounds vaguely familiar to you, well….it should. Hollywood Story offers a fictionalized account of the unsolved murder of William Desmond Taylor, who was shot to death in his bungalow in the wee hours of a February night in 1922. (David blogged about the crime here.) The subsequent investigation of Taylor’s death ensnared some of the industry’s biggest stars of the period. Mabel Normand’s reputation was tainted by her association with Taylor and by reports of drug use. She took a brief hiatus from filmmaking because of the scandal, but never completely recovered from it. Normand later died of tuberculosis in 1930 at the tender age of 37.

As a fictionalized account of a notorious unsolved crime, Hollywood Story anticipates more modern thrillers that provide speculative solutions to real-life murders. Zodiac and The Black Dahlia are prime examples, as are any number of Jack the Ripper films. Hollywood Story’s approach was not unprecedented. James M. Cain based Double Indemnity on the Ruth Snyder case that was fodder for New York tabloids in the late 1920s. That said, Taylor’s death lingered for decades in popular memory in a way that the Snyder case did not.

What are we to make of The Player’s citation of Hollywood Story? On the one hand, viewers might well notice the almost immediate parallel of our “film execs in jeopardy” storylines. Just as Griffin is stalked by an unknown assailant, so, too, is Larry the target of a shadowy aggressor. Moreover, Hollywood Story, along with Sunset Boulevard, might well be an inspiration of one of The Player’s most interesting features: its intermingling of real life stars with fictional characters. Hollywood Story includes cameos by Joel McCrea and several noted performers of the silent era, such as William Farnum, Francis X. Bushman, and Betty Blythe (below). The Player pushes this aspect of Hollywood Story to extremes, containing plentiful cameos by Cher, Jack Lemmon, Burt Reynolds, Lily Tomlin, Susan Sarandon, and other A-listers.

In several other respects, though, The Player seems like an inversion of Hollywood Story with Griffin emerging as a more venal counterpart to the latter’s crusading producer, Larry. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s investigation actually produces results. This strongly contrasts with Griffin’s guesswork, which, as the result of a tragic mistake, leads to David Kahane’s death in a Pasadena parking lot. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s blossoming romance with Sally furnishes the standard double plotline commonly found in classical cinema. In The Player, though, Griffin’s interest in June seems genuinely sleazy. It also exacerbates the Pasadena police’s doubts about Griffin’s alibi, making him their prime suspect. Finally, the revelation of screenwriter Vincent St. Clair as Franklin Ferrara’s killer provides closure both to Larry’s script and to Hollywood Story itself. In contrast, none of the crimes presented in The Player are really solved. Griffin is blackmailed into greenlighting a project during the film’s epilogue, but the audience never learns the identity of the mysterious stalker. Similarly, although the Pasadena police believe that Griffin is guilty of murder, the botched lineup ensures that he will go free and that David Kahane’s death will remain an unsolved crime. In an odd way, The Player returns to the narrative roots of Hollywood Story. The fate of Kahane, our aspiring screenwriter, seems destined to mirror that of poor William Desmond Taylor, our successful silent film director.

A thriller with no thrills

I’ve sketched out a number of different ways in which The Player relates to the basic conventions of the crime thriller, but all of this is ultimately, in the parlance of the genre, a red herring. This is because The Player is that rare bird: a crime film that engenders relatively little curiosity about its solution and even less suspense about the fate of its protagonist.

This is largely because Robert Altman mostly uses crime film conventions as scaffolding for the things that really interest him: quirky characters, digressive dialogue, and a loose, improvisatory feel to the film’s performances. At its heart, The Player is a comedy that draws upon crime film conventions in much the way Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye does.

Compare, for example, each film’s tweaking of the genre’s standard interrogation scenes. In The Long Goodbye, Detective Farmer’s tough questioning of Philip Marlowe is punctured by the latter’s goofy responses. At one point, Marlowe uses the ink from his fingerprinting procedure like it was the “eye black” used by an athlete. Later, he smears the ink all over his face and sings “Swanee” in a mocking homage to Al Jolson in blackface. Similarly, in The Player, the Pasadena police’s interrogation of Griffin is disrupted by Detective Avery’s disarming exchange with her partner about tampons, her mangled pronunciation of “Gudmundstottir,” and her dialogue with Paul about Todd Browning’s Freaks.

The Player has many ingredients characteristic of crime films: a dead body, an investigation, a shady suspect, and a campaign of stalking and extortion. Yet, by the time Altman’s film reaches its ironic and deeply reflexive conclusion, viewers might well conclude that they are the ones who just got played.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their Criterion colleagues. A list of our Observations on Film Art series is here.

For more on Robert Altman’s career, see Patrick McGilligan’s excellent biography, Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. There are also several books featuring interviews with the iconoclastic director. These include David Sterritt’s Robert Altman: Interviews, Mitchell Zuckoff’s Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, and David Thompson’s Altman on Altman.

Those interested in learning more about crime fiction should consult Martin Rubin’s Thrillers, Charles Derry’s The Suspense Thriller: Films in the Shadow of Alfred Hitchcock, John Scaggs’s Crime Fiction, Richard Bradford’s Crime Fiction: A Very Short Introduction, and Martin Priestman’s The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction.

Hollywood Story (1951).

The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

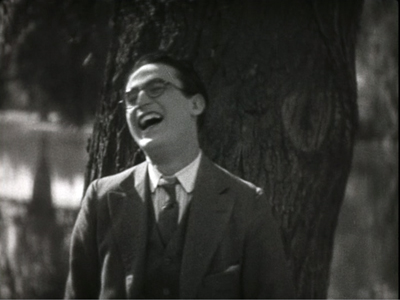

On 9 September 1917, film history changed for the better. That was when we got the eyeglasses.

Their circular, horn-rimmed frames stood out as wire rims would not; besides, horn rims had become fashionable for young people. These specs held no lenses, but so much the better. Reflections from studio lights would have hidden the eyes of the winsome, earnest, clueless young man usually called the Boy.

In Over the Fence, the film introducing him, he’s already amiable, a little vacuous but delighted to be talking to his girl on the phone and watching himself doing it.

Harold Lloyd had already featured in some sixty-five short comedies from 1915, playing characters called Willie Work and Lonesome Luke. Even after introducing the Boy, Lloyd continued with a few Lukes before phasing out this sad sack. No one expected that in a few years the glasses character would become world famous. Lloyd’s films were more lucrative in aggregate than those of any other silent comedian, and he became one of the central figures in Hollywood.

When our comrades at Criterion announced their plan for a centenary Lloyd celebration this month on FilmStruck, I suggested we devote an installment of our series to one of the films. Kristin and I have been Lloyd fans for decades. Fans and collectors kept his work alive. Kevin Brownlow had to remind people with his Lloyd documentary, The Third Genius (1989), that, well, Lloyd was a genius. The more you get to know his work, the better it looks, and the less plausible seem many of the clichés that have clustered around it.

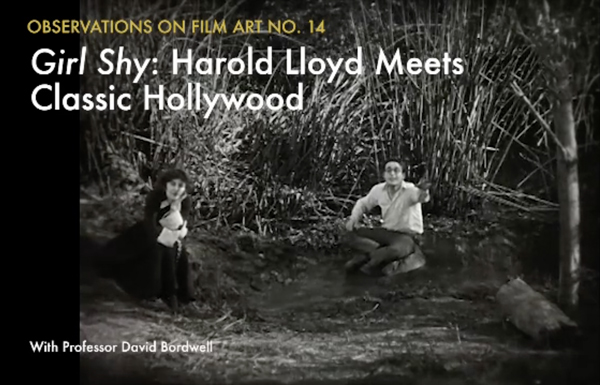

One of the very best films to get to know is Girl Shy (1924). That’s the one analyzed in the latest Observations on Film Art episode on the Criterion Channel.

Man into Boy

For decades after sound came in, American silent comedies dropped mostly out of sight. Some 16mm copies were available in cut-down rental versions, and a few were circulated by the Museum of Modern Art Film Library. (Of Lloyd’s work, that included only The Freshman of 1925.) The MoMA canon became the canon. In the 1970s, thanks largely to piracy, the films of Keaton were added, and still later we came to recognize Charley Chase, Max Davidson, and other talents.

Throughout these years Lloyd’s films were almost invisible because he controlled the rights to them and limited their circulation. Kept in vaults in his rococo estate Greenacres, they would not reemerge until the 1960s, in cut TV versions distributed by Time-Life. Until fairly recently, most critics relied on memory of the films and the received image of the Boy dangling helplessly from the clock face.

Most of the sixty-one shorts featuring the Boy languish in archives, and some were lost in a fire on the Lloyd estate. But several two-reelers are readily available, as are all the longer films. What we have gives the lie to most clichés about this filmmaker.

Take the most persistent one. Socially conscious critics of the 1930s saw Lloyd’s work as naively reflecting the go-go 1920s. The Boy’s resolutely middle-class aspirations made him a crass avatar of complacency before the Crash. Chaplin seemed to stick up for the little guy, but Lloyd seemed to celebrate the striver; he compared himself to Tom Sawyer. It was all very neat. The Boy’s climb up the skyscraper in Safety Last could symbolize the heedless ambition of the white-collar worker, while the his efforts to fit in at college in The Freshman suggest desperate American conformity.

Those interpretations played down the fact that just as often Lloyd played hayseeds humiliated by city folk and con artists. In Girl Shy, the city slicker who wants the girl is a weasel, and Harold has to rescue her. Here, as often, the film is largely a procession of social humiliations. Lloyd, a predecessor of cringe comedy, in turn provided a model of embarrassment for Ozu’s silent films. Those films often feature students wearing the Boy’s glasses (below, Days of Youth, 1929). This isn’t mere imitation or homage; the glasses became a Japanese fashion item, called roydo, named after Lloyd. (Below, a photo from a student ski trip in the 1930s.)

More edgily, Lloyd also played foppish idlers, louche one-percenters who glide obliviously through the lower orders and need to learn humility. The original title of For Heaven’s Sake (1926) was to be The Man with a Mansion and the Miss with a Mission, a phrase retained in an intertitle. Here as elsewhere, the coddled Boy learns to help his social inferiors. If you’re after class-based critique, Lloyd films come out pretty well.

Likewise, there were the complaints that Lloyd’s comedy was mechanical. Chaplin was the poet and dancer. Keaton, in both concept and execution, showed himself a geometer, the dogged engineer of monumental effects more awe-inspiring than hilarious. Though granting that Lloyd, foot for foot, yielded more laughs than any of his peers, critics worried that he was only merely funny, a relentless gag machine. Here is James Agee, in one of the subtlest appreciations of silent cinema ever written:

If great comedy must involve something beyond laughter, Lloyd was not a great comedian.

But immediately, as an honest man, Agee must add:

If plain laughter is any criterion—and it is a healthy counterbalance to the other—few people have equaled him, and nobody has ever beaten him.

Still, Agee admits that Lloyd’s films pass beyond laughter in one respect. They offer harrowing suspense. What his audiences called “thrill comedy” remains chilling today. His antics on skyscraper ledges and girders still induce vertigo, and his car chases risk catastrophe on a scale that would worry Jackie Chan. Agee seems to grant that inducing shrieks as well as guffaws is no small accomplishment.

If Agee could have reviewed all the feature films, though, maybe his judgment wouldn’t have been so absolute. For example, Lloyd’s features take us beyond laughter in serious ways—into regions of vulnerability and inadequacy. The Boy is typically given a fault: cowardice (Grandma’s Boy), self-absorption (as hypochondria in Why Worry? and as self-indulgence in For Heaven’s Sake), lack of confidence (The Kid Brother), neurotic extroversion (The Freshman). In several films, the seriousness undercuts the comedy.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold can’t drive away the tramp, but Granny can do it easily, with some swipes of her broom. Our laughter is cut short when, in the space of a cut, as she calmly returns to the porch, we see the Boy slumped over, his head in his hands.

Soon he will admit that he’s a coward. Lloyd films switch their tone on a dime, shifting between comedy and drama breathlessly. In Girl Shy, the Boy not only dumps the girl he loves but does so by cruelly laughing at her trust in him. (Agee: “He had an expertly expressive body and even more expressive teeth.”) Wobbling and shifting his weight, Harold breaks the laugh with a gulp before carrying on his bluff.

Nothing in Keaton or Chaplin makes us as ashamed of our hero as we are right now. Soon he will do something worse.

This passage reminds us that Lloyd worked his face for all it was worth. Keaton had more expressions than he’s usually credited with (bewilderment, concentration, doggedness); it’s just that he doesn’t smile. Chaplin inherited the white-face clown tradition and often favored deadpan. He limited his facial reactions to squiggles and flashes, often no more than a skew of the mouth or hauteur in the brows, with an occasional embarrassed giggle. With Chaplin, the body expresses nearly everything, as befits an aesthetic predicated on the long shot.

But Lloyd, relying on medium shots, performs as a dramatic actor, with a wide repertory of expressions. Agee refers to his “thesaurus of smiles,” but he had other resources, as this Girl Shy scene attests. His producer Hal Roach is said to have remarked: “Harold Lloyd was not a comedian. But he was the finest actor to play a comedian that I ever saw.”

Another nuance: Comic laughter comes in many varieties. Like Keaton, Lloyd celebrates winning through tenacity and resilience. If we gasp at the geometrical audacity of Keaton’s humor, we’re buoyed by Harold’s righteous settling of accounts. It’s reported that audiences actually leaped up and cheered at the climaxes, when bullies and rascals were punished at delectable length. These are comedies of comeuppance and payback, outcomes universally enjoyed and still much in demand today, when millions hope for a scourging of the jackals in our White House.

Point the last: Neatness of construction. Chaplin’s films are lovably episodic; I still marvel that films that took so long to make are so loosely put together. Keaton by contrast is a metronome-and-protractor director, aiming to make every shot and sequence and reel sit in meticulous order. No one but he could have conceived the marvel of symmetry that is The General, or, on a lesser scale, Our Hospitality and Neighbors.

Lloyd’s films are no less finely put together, as many recognized at the time. A Film Daily review of The Kid Brother (1927) noted: “Lloyd and his gag-men again have devised a corking set of comedy situations that fit consistently into a well-joined plot and laughs keep building from little chuckles to hilarious roars.” Orson Welles praised “the construction of Safety Last, for instance. As a piece of comic architecture, it’s impeccable. Feydeau never topped it for sheer construction.”

To get a little more specific, I think that Lloyd’s model was the well-made dramatic film, the tight classical plot. This is the argument I make in the Girl Shy installment. I try to show that in this, his first film as an independent producer, Lloyd applied the emerging model of Hollywood narrative to feature-length physical comedy. Fairbanks had moved in this direction, and Lubitsch would achieve something similar with social comedy in The Marriage Circle (1924) and the masterpiece that is Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

Lloyd was a pioneer in showing how everything that worked for serious dramaturgy could work for comedy too. Girl Shy gives us a goal-oriented protagonist who has a serious flaw. Going beyond the figures of slapstick, we get access to his psychological yearnings and frustrations. His loneliness and fear of women fuel overwrought fantasies of domination. The Boy is caught up in the characteristic Hollywood double plot, involving love and career—two lines of action that usually block and deflect one another.

This linear action is deepened by a series of motifs. They’re simple in themselves (a stammer, a Cracker Jack box, a dog biscuit box), but they’re worked out with a pictorial and dramatic intricacy that’s rare at the time. And it’s all topped off by a two-reel chase that is simply one of the greatest ever put on the screen. At a time when every superhero blockbuster ends with a big action sequence, it’s worth seeing one that’s both graceful and hilarious, and it owes nothing to special effects.

Girl Shy shows how rewardingly complex silent Hollywood storytelling could be. It reveals Lloyd as a master craftsman of cinematic resources—dramatic, pictorial, emotional. He saw how to make a movie that would be engrossing even without the gags. The comedy deepens a powerful dramatic premise that moves forward with an organic, not mechanical, energy, and it’s developed in funny or poignant detail at every instant.

Filling the format

In the arts, form often follows format. The fourteen-line sonnet, the tondo painting, the twenty-two-minute sitcom, the nine-panel comic-book page: all provide the artist with a set framework within which to create. When Lloyd started out, film reels in the US were standardized at 1000 feet, which typically ran between twelve and fifteen minutes, depending on projection speed. Short films, particularly comedies, were either one or two reels, while features–dramas, mostly–ran four, five, or more.

The task of the filmmaker was to build a story that would fit the format. The temptation was padding. Griffith, for instance, often filled out his shorts with “goings and comings,” shots of characters leaving one place and making their way to another, sometimes across several shots. But once padding was inserted, filmmakers could make it engaging. Griffith did this by embedding the goings and comings in suspenseful situations, so that the travel shots served as dramatic delays. Mack Sennett needed scenes to lead up to a big chase (the “rally”), but those scenes could themselves have a linear logic, as with romantic rivalry or street quarrels.

Lloyd became very sensitive to film length. He knew that his initial popularity depended on the fact that Pathé and producer Hal Roach spit out a Lonesome Luke every week or two; he saturated the market. Even after Luke appeared in two-reelers, Lloyd wanted his new character, the Boy, to start in one-reelers. He recalled telling Roach, in sentences as breathless as the pace of a one-reeler:

Now, I’m getting started in a new character and you want people to get used to the character, you want them to see the character; and besides, if you make a poor, or mediocre, or moderately good, or even a bad picture in a two-reeler, it’ll kind of tend to sour the people on you because they won’t see another one for a month. But if I make one-reelers, we’ll get one out every week, so if a couple of them are not so good, and the third one is, it will cover up the other two, and besides it will keep you in front of the public.

As a result, Lloyd spent two years turning out an astonishing eighty-two one-reelers. Not until Bumping into Broadway (2 November 1919) did he launch a two-reeler featuring the Boy.

There’s evidence that Lloyd’s awareness of the niceties of running times went beyond a concern for building the brand. He understood that form and format had to mesh. His early one-reelers relied largely on the standard episodic knockabout. We’re given a defined situation, such as a modernized hotel (The City Slicker, 1918), a western saloon (Two-Gun Gussie, 1918), or a vaudeville theatre (Ring Up the Curtain, 1919). In this situation, the characters quarrel, pull pranks on one another, engage in fistfights, kick each other in the pants, and usually wind up in a chase. A string of gags might emerge, as when a stray snake terrifies the theatre troupe in Ring Up the Curtain, but the gag is quickly exhausted, and we go on to the next bit.

Once Lloyd settled on two-reelers, he built them up more carefully. He scaled, we might say, his plots and gags to a fairly tight, logical development in the fuller format. Part of that development involves what we might call nested gags. In Captain Kidd’s Kids (1920), the first part (roughly one reel) sets up Harold as a playboy recovering from a bachelor party. In his elaborate bathroom, he tips back his chair, leading us to expect him to fall in. But no: instead his butler, Snub Pollard, dumps ice in the pool.

There follows a string of shaving gags here and in the next room. Early in this series, Harold drips shaving cream in his morning tea; but after other gags he comes to drink it and finds it foul-tasting. Then he returns to the bathroom, tips back the chair again, with results we’d expected several minutes before.

Now we get some elaborate efforts to rescue Snub. The gags are simple, but by setting up one and then moving to set up and pay off others before returning to the first, Lloyd and his team avoid the start-stop-restart pattern than we find in many one-reelers.

The real plot action, of course, doesn’t get going until the second reel of Captain Kidd’s Kids, but Lloyd has provided some lively padding to start. Now or Never (1921) shows the same gag-braiding, with the recurring appearance of two drunks on the train ride that constitutes the bulk of the film.

Lloyd moved toward longer films cautiously—first to three reels, then four (A Sailor-Made Man, 1921), then five (Grandma’s Boy and Dr. Jack, 1922). He always said that most grew organically, beginning as two-reelers and then expanding when the story premises and gag sequences developed. To keep things in proportion, he tested the results on preview audiences, then reshot and recut his footage. The preview responses to one three-reeler, I Do (1921), convinced him to lop off the entire first reel. Although he had increased confidence in his ability to scale up, when he signed a new contract with Pathé in early 1922 he insisted that the company publish a notice to exhibitors declaring that film length would be

strictly governed by the character and quality of the material evolved in the production development of each subject—which means that the Lloyd standard of excellence is to be maintained first of all; a given story that turns out to be adequately filmed in two reels will be confined to two reels, and so released. This is a principle cherished by Lloyd himself.

Lloyd could be so confident because even his shorter releases were becoming the top-billed item on programs across the country. He was, in effect, returning the idea of “feature” to its original meaning—not simply a long film, but rather a movie that could be “featured” in publicity. He was also announcing his unusual concern for tight form.

Comic architecture

Grandma’s Boy (1922).

Lloyd moved to features in synchronization with his peers. Keaton was the first, with The Saphead (September 1920), though it’s less a comedy than a light drama; and Keaton returned to making two-reelers for three years. The Round-Up (October 1920) gave Fatty Arbuckle a comic role in what was basically a serious drama. Arbuckle starred in The Life of the Party (December 1920), another light drama with almost no physical comedy. Chaplin’s The Kid (February 1921), at a bit more than five reels, might be considered the first slapstick feature since the one-off Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914, six reels). The émigré Max Linder got into the act with two 1921 features, Seven Years’ Bad Luck (May 1921) and Be My Wife (December).

It might seem that Lloyd was a bit late with the four-reel Sailor-Made Man (December 1921). But that film capped his most extraordinary year to date, with four earlier films released in spring, summer, and fall. Along with six two-reelers released in 1920, Lloyd was now a major comedy star, and the Boy could carry a longer story.

But how to do that? His peers explored some options. In Arbuckle’s two features, it’s his physical presence that matters, not consistency of character; in one he’s a genial sheriff, in the other a lawyer inclined toward crookedness. Chaplin retained the Tramp persona in The Kid, but the film is a rather episodic affair. Once the main plot is resolved, a reel pads out its length with a dream sequence set in heaven. The Linder films are lively but digressive, with plots propelled by casual pranks and lovers’ misunderstandings.

By contrast, Lloyd’s features moved toward tight construction. Despite his claim that his films just grew longer accidentally, they were shaped in ways that make them seem through-composed. His comedy sequences are deftly prolonged, building and topping themselves with great speed. Gags are embedded and interwoven in ways that yield surprises, and motifs set up early in the film pay off later. We may have forgotten about them, but Lloyd hasn’t.

Lloyd’s obsession with overall form can be seen in his use of the “Lafograf,” a kind of EKG of viewers’ response at previews. Coders sat in the audience with pencil, paper, and stop watches to note every bit of amusement, from a titter to a screech. Once graphed, the entire movie displayed laughs big and small throughout, with most of the big ones spiking in the last reel.

A powerful demonstration of Lloyd’s skill came in his first five-reeler, Grandma’s Boy (1922). Chaplin called it “one of the best constructed screenplays I have ever seen on the screen.” Lloyd began it as a two-reeler, but after expansion it had become more drama than comedy. Roach urged him to add more gags, and the result is a remarkable balance between humor and pathos.

That mixture is given from the start in a prologue showing a baby Harold, glasses and all, bullied by another baby. Then the Boy as a boy is picked on and made to put a chip on his shoulder.

This last bit will pay off fifty minutes later. The rival, the little bully grown up, taunts Harold, not knowing Harold has captured the prowling tramp and proven his courage.

The upshot is a fight that knocks the stuffing out of the Bully. In the course of that fight, another moment calls up a contrast with an earlier scene. The day before, the Bully has pitched Harold into the well; now, after the Rival tries a foul blow, Harold administers payback.

These distant echoes can be very satisfying.

The organization of gags is likewise remarkably sustained. Walking home from his well dunking, Harold finds that his one suit has shrunk grotesquely. But the Girl has invited Harold to her home for an evening, so he needs another suit. Granny digs out his Grandpa’s suit, 1862 vintage. (The peddler said it was unique.) It still has mothballs in it. Granny also finds there’s no shoe polish, so she uses goose grease instead. These bits become the basis of a steadily building gag situation in the Girl’s parlor.