Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories

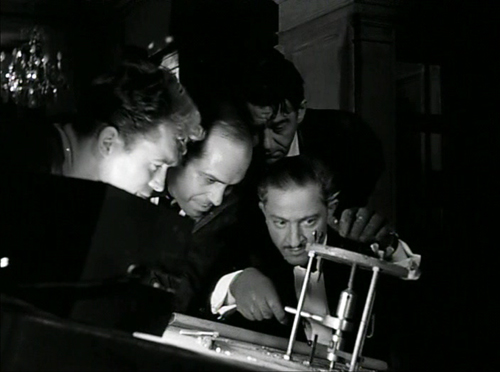

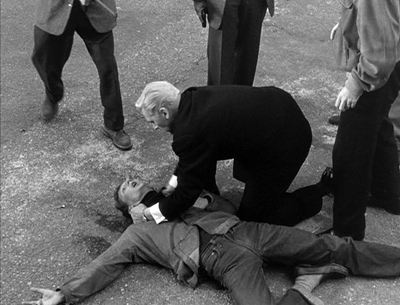

The Underneath (1995).

DB here:

The announcement of Ocean’s Eight (premiering, when else?, on 8 June next year) reminded me of the staying power of the heist genre, also known as the big-caper film. I discuss it a bit in Reinventing Hollywood, my book on 1940s storytelling, but it developed and spread out most vigorously from the 1950s on.

In its origins it relies on masculine roles; if women are present they’re likely to be at best helpers, at worst traitors. The big job is likely to be endangered by a man telling his wife or mistress too much, and then the police or rival gangs may interfere. So the news that Ocean’s Eight will center on a female gang constitutes an intriguing wrinkle. (Will a boyfriend try to spoil the caper?) Warners’ ambitions for another trilogy seem evident: presumably the entry is Eight because Warners hopes for a Nine and a Ten. Commenters are already worried that a “feminized” version runs the risk of flopping the way Ghostbusters did last year, but I’m more hopeful. The reason is that clever storytelling is encouraged in this genre. There’s a chance that the film, produced though not directed by Steven Soderbergh, will show us that this old dog has new tricks.

Because I’m interested in the storytelling strategies of popular cinema, the heist film is a natural thing for me to consider. Refreshing the genre may involve not just adjusting the story world—giving men’s roles to women—but also considering ways of handling two other dimensions of narrative: plot structure and cinematic narration. I argue in Reinventing that Hollywood filmmaking uses a sort of variorum principle, a pressure to explore as many narrative devices as possible within the constraints of tradition. For this reason, the prospect of Ocean’s Eight prodded me to think about how convention and innovation work in the caper movie. It’s also a good excuse to go back and watch some skilful cinema.

From the fringes to the core

The Asphalt Jungle (1950).

It’s useful to think of a genre as a category having a core and a periphery. At the core are prime, “pure” instances: prototypes. Stretching out from it are less central, fuzzier cases. Prototypical musicals are Footlight Parade, Shall We Dance?, Meet Me in St. Louis, and My Fair Lady. Somewhat less central are concert films and musical biopics like Lady Sings the Blues and Coal Miner’s Daughter. At the periphery are movies with a single song or dance number. Of course the category changes across history; a critic in 1960 might have picked North by Northwest as a prototypical spy thriller, but ten years later a Bond film would have probably held that place.

The prototypical heist film, critics seem to agree, doesn’t just include a robbery. There are robberies in films about Robin Hood and gentleman thieves like Raffles and the Saint. The outlaw or bandit film like They Live by Night and Bonnie and Clyde contains a string of robberies, but they wouldn’t be at the center of the heist category.

Donald Westlake proposed a concise characterization: “We follow the crooks before, during, and after a crime, usually a robbery.” This indicates two things. First, the plot is structured around the big caper, though there might be lesser crimes enabling it, such as stealing weapons. Second, the viewpoint is organized around the criminals, not the detectives who might pursue them, as in a police procedural. By these criteria, High Sierra (1941), although allied to the bandit tradition, fits because most of the film concerns a single robbery, its preparations and aftermath.

Westlake shrewdly goes on to note that the interest of a heist plot inverts that of the traditional locked-room detective story. Instead of wondering how something difficult was done, we wonder how something difficult will be done. “The puzzle exists before the crime is committed.” To fill in the how, crooks with specific skills (safecracking, demolition, getaway driving, and so on) are recruited. Because the process matters so much, Westlake adds that heist plots focus on details of time and physical circumstance, and they draw attention to impediments such as “dogs, locks, alarms, watchmen, and complicated traps.” Most of these features are missing from High Sierra; we’re not encouraged to speculate how the job will be pulled, there’s little meticulous planning and no division of labor by expertise, and the only dog is friendly. So it’s unlikely to be a core instance of the genre as we now consider it.

Most critics consider The Asphalt Jungle (novel, 1949; film, 1950) a solid prototype. In fiction and film it’s not the very earliest instance, but it displays what we might call the “completed arc” of a heist plot. A gang of varying talents is assembled and funded to pull off a jewel robbery, which succeeds partly at first and eventually fails.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

Criss-Cross and The Asphalt Jungle show that we’re dealing with an exceptionally schematic plot pattern. For convenience we can distinguish five parts.

Circumstances lead one or more characters to decide to execute a heist (robbery, hijacking, kidnapping).

The initiators recruit participants.

As a group they are briefed and prepare their plan. They study their target, rehearse their scheme, or take steps to make it easier.

The heist itself begins and concludes.

The aftermath of the heist, failed or successful, shows the fates of the participants.

There are other conventions, nicely laid out by Stuart Kaminsky in 1974 and more recently by Daryl Lee. But I’ll just concentrate on this structure and how it governs narration, because these aspects show very clearly the constant dynamic of schema and revision in the filmmaking tradition.

Four capers, mostly unhappy

Criss Cross (1948).

Four films in the period covered in my book point toward the heist genre, though only one became a core instance. The presence of a “consolidating” film might be one way genres emerge.

The earliest candidate is an unlikely one. In 1941 Laura and S. J. Perelman mounted a notably unsuccessful play called The Night Before Christmas, a farce in which crooks buy a luggage store in order to tunnel from its basement into the bank vault next door. Although Paramount was a backer of the stage show, Warners bought the rights and revamped it for Edward G. Robinson, who had had success in gangster comedies like A Slight Case of Murder (1938). The adaptation, Larceny, Inc. (1942) maintained the premise but revised the plot, multiplying the complications that face the leader Pressure and his two minions. The twist is that thanks to Pressure’s daughter, who’s unaware of the scheme, business starts booming and the crooks find themselves prosperous businessmen. Woody Allen swiped the premise for his Small-Time Crooks (2000).

Just as we don’t expect a comedy to be the initial entry in a genre mostly associated with drama, we might expect that the early entries in the genre would be the tidiest, with complex variations building on them. Actually, two precursors of The Asphalt Jungle display remarkable complexity.

The simpler one, Criss Cross (1948), starts late in the preparation phase: the night before the caper, when the gang is holding a party to distract a local cop who has his eye on them. We learn that Steve is working with Slim’s wife Anna to double-cross the gang. The next day, Steve is driving the armored car and recalling how he got into this situation. A flashback provides the circumstances for the robbery—Steve’s pursuit of Anna, her marrying Slim, and Steve’s impulsive proposal of a robbery to protect Anna from Slim’s punishment.

Next comes the planning phase. The robbers assemble and the task is reviewed by a mastermind they hire. This second flashback ends and, back in the present, we see the heist itself. The aftermath of the bloody robbery shows Steve in the hospital, honored by the community. A thug kidnaps him and takes him to Anna. Slim has survived the gun battle and finds the couple; he kills them before he is mowed down by the police.

Early as Criss Cross is in the history of the film genre, the plot components are already being scrambled. Thanks to 1940s Hollywood’s commitment to flashbacks and character subjectivity, the novel’s linear action gets fractured, compressed, and stretched. Moreover, in most films, the decision to pull the heist is made fairly early. Here and in the novel, circumstances slowly force Steve to rescue Anna from the man who mistreats her. The buildup to this decision consumes nearly fifty minutes of an 87-minute movie. Similarly, the aftermath of the heist is quite protracted, running about twenty minutes. And whereas other films (and novels) dwell on the recruitment of thieving talent, here this is elided. That’s because the other members of the gang are less significant than the central triangle of Steve, Anna, and Slim.

The Killers (1946) is even more complex because it clamps the block construction of Citizen Kane onto the heist schema. We start with one bit of the heist aftermath: the death of the gas-station attendant Ole. Like Kane, who also dies in his bed at the start of his film, Ole is the protagonist of the past-tense story. We next meet the protagonist of the present-time story, the insurance investigator Riordan, who functions like the reporter Thompson in Kane, and sometimes even gets the same silhouette treatment.

The rest of the film splits up the basic parts of the heist schema, rearranges their order, and presents them through a series of several flashback blocks, anchored in six characters’ testimony.

The heist itself is very brief, running only about two minutes, and the planning phase is only a little longer. As in Criss Cross, the leadup and the aftermath constitute the bulk of the film, but these phases are broken up into many bits, and these are often shuffled out of chronological order. We see Ole’s discovery by Big Jim years after the heist and then we see Ole, days after the heist, distressed that his lover Kitty has betrayed him. Similarly, a crucial event after the heist—Ole’s stealing the loot from the gang—precedes a scene before the heist in which he learns the gang is planning to double-cross him. We have to reconstruct the canonical sequence, from circumstance to aftermath, out of fragments revealed in testimony taken by Riordan.

Critics haven’t taken Criss Cross and The Killers as the first core instances of the heist film, perhaps because these movies complicate the classic plot template. In addition, they downplay the planning and execution phases. The heist scenes are relatively minor compared to the time devoted to other phases, particularly the circumstantial buildup. Moreover, the robber teams aren’t vividly characterized and don’t display a range of expertise. The emphasis falls on Steve and Ole, both played by Burt Lancaster, as the beautiful losers who become suckers for treacherous women and their brutal men.

By contrast, the linearity of The Asphalt Jungle throws the plot template into crisp relief. Both novel and film offer a full-blown enactment of central features picked out by Stuart Kaminsky. The gang, despite low social standing, has many skills. They’re held together by a leader who may also be a brainy planner. The robbers’ plan requires “skill, practice, training, and above all, perfect timing.” The gang’s resourcefulness is tested by accidents. The caper is partly successful but largely a failure, often through sexual weakness on the part of some players.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

The novel lays out the canonical action phases with surgical efficiency. But as in the films I’ve just mentioned, the planning and the heist itself take relatively little space. Given so many characters’ contribution to the action, their gradual convergence and their dispersed fates dominate the book. Over a hundred pages are devoted to setting up the circumstances and recruiting the gang. The aftermath, tracing the outcome for all involved, runs another 140 pages.

The film adaptation retains the novel’s scope, trimming only a couple of minor characters. It moves briskly among the ensemble, attaching us to several in turn, so we know more than any one character does. The narration creates parallels among the team members and their affiliates (such as four women of different classes, with varying commitments to their men).

The result is something of a network narrative, a cross-section of several people whose lives change because of the robbery. There’s no clear-cut protagonist like Steve in Criss Cross. Dr. Riedenschneider has the most screen time, but the film begins and ends with the hooligan Dix, and the fate of both men dominates the climax. I point out in Reinventing Hollywood that a multiple-protagonist film often gives extra weight to one or two characters.

50s and 60s stylings

Violent Saturday (1955).

With The Asphalt Jungle as a robust prototype, writers and filmmakers developed the heist plot throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Despite his clumsy style (”He nodded with his head”), Lionel White became known as “the king of the caper novel” for his tireless variants on robberies, hijackings, and kidnappings. The other major figure was the far superior Donald Westlake, who wrote brutal heist tales as “Richard Stark” and comic ones under his own name.

In the comic register, Westlake was beaten to the post by heist films from England. The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) showed a timid clerk engineering the theft of gold bullion, which he disguises as kitschy miniature Eiffel Towers. The Lady Killers (1955) centered on a gang fooling their landlady into thinking that their planning meetings are actually string-quartet sessions. In Italy, the classic Big Deal on Madonna Street (I soliti ignoti, 1958) showed five incompetents trying to break into a pawnshop safe.

Big Deal was considered a parody of a much more serious film, one that was by then a landmark: Rififi (Du rififi chez les hommes, 1955). It did a great deal to consolidate the genre in France, along with Touchez pas au grisbi (1954) and Bob le flambeur (1956). (Both The Killers and Criss Cross had been imported in the Forties.) In England, the heist drama was seen in The Good Die Young (1954), while in the US there were 5 Against the House (1955), Violent Saturday (1955), Plunder Road (1957), The Big Caper (1957, from a White novel), and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). The year 1960 saw a remarkable number of releases, with The League of Gentlemen (U.K.), The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, Seven Thieves, and most famously Ocean’s 11 (all U.S.).

Through the 1960s the genre proliferated, including a remake of The Asphalt Jungle (Cairo, 1963), Jules Dassin’s near-self-parody of Rififi (Topkapi, 1964), and a string of heist films that mixed in romantic comedy (e.g., Gambit, 1966; How to Steal a Million, 1966). The Italian Job (1964) became a cult movie, with tourists visiting the sites of shooting in Turin. The genre has remained robust throughout world cinema ever since.

The very rigidity of its format and the constraints it lays down, have allowed for ingenious innovations. I’ll sample some of those from the genre’s first dozen or so years, concentrating on three areas: the differing emphasis given to the plot phases; variants of point-of-view; and manipulations of time.

Where’s the action?

Rififi (1955).

The Asphalt Jungle offers a fairly pure geometry: the heist, lasting about eleven minutes, ends just before the film’s midpoint. On the other side of that is another big scene: a gunfight initiated by Emmerich’s henchman Brannom when Dr. Riedenschneider and Dix bring in the loot. That confrontation takes another seven minutes, so the heist and its immediate wrapup sit at the center of the running time. What led up to the heist, the circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases, consume the first forty-five minutes of the film, and the aftermath of the heist, affecting the surviving characters, will take just about as long. This balanced geometry, putting the heist snugly at the center of the plot but devoting most time to showing many lives leading up to and away from the crime, suits the extensive characterization of all involved.

This is a neat structure, but not the only possibility. Any phase of the action can be given great weight. The first half hour of Bob le flambeur is an episodic introduction to Bob’s routines and associates. It’s the circumstantial phase—he’s running out of money—presented at low pressure, emphasizing instead the fascinating milieu Bob coolly drifts through. Only when Roger points out a croupier at the Nantes casino does Bob formulate “the job of a lifetime.” Then crew assembly and planning can begin. As the plot develops, characters and relationships presented casually in the exposition become crucial to the heist and its unraveling.

Other phases can be stretched out. Ocean’s 11 dwells on the phase of gathering the talent. Before the start, Danny Ocean has already conceived the heist, but we aren’t told the plan. Instead we watch his team members converge on Las Vegas. Not until the film’s midpoint, at 53:00, is the plan revealed in a briefing. The dawdling exposition suits a film about cool guys hanging out.

The formation of the crew is exceptionally protracted in Odds Against Tomorrow, because here two members hesitate about participating. The racist Earl Slater, wracked by the shame of not providing for his wife, finally gets her to agree to let him join. Not until twenty-three minutes from the end does the African-American musician Johnny Ingram finally accept a role in the heist, which immediately becomes the film’s climax.

The source for Odds Against Tomorrow (one of the better heist novels) handles the basic pattern very differently, putting the heist just before the midpoint and devoting the second half of the book to the increasingly hopeless getaway, where the interracial tensions play out at length.

The planning phase sometimes includes a rehearsal for the heist, and that may require a subsidiary crime, such as stealing keys or a vehicle. The League of Gentlemen has an unusually long planning phase, in which the gang masquerades as soldiers in order to seize weapons from a military post. This robbery, running nearly twenty minutes, takes longer than the film’s main heist but serves to demonstrate the team’s resourcefulness and esprit de corps. The men’s precision and resourcefulness (based on their wartime experience) lead us to expect a successful main event.

Kaminsky suggests that the big-caper genre resembles the soldiers-on-a-mission movie, which centers on the details of a process executed by skillful specialists. That display of process comes to the fore in The Asphalt Jungle’s central robbery, which initiated the convention of detailing the mechanics of the heist. Other films expanded the heist sequence to larger proportions than was evident in The Killers or Criss Cross. Rififi became the model; its heist runs twenty-five minutes without any words being spoken. (That sequence is part of an even longer wordless stretch that runs over thirty minutes.) Dassin’s film meticulously breaks down the steps of a complicated robbery, allowing us to appreciate the men’s clever planning while, as usual, ratcheting up moments of suspense when it appears they might fail.

After Rififi, heist scenes got longer and more intricate. The one in Big Deal on Madonna Street runs twenty minutes, those in Seven Thieves and The Day They Robbed the Bank of England run thirty minutes, and those in Topkapi and The Italian Job approach forty minutes. To motivate these long, virtuosic passages, there need to be many obstacles, many ingenious ways around them, and many characters concentrating on their assigned duties.

Long or short, the heist can be shifted off-center. The heist can be the climax, as in The Big Caper, or it can be virtually the film’s entire second half, as in The Italian Job (which arguably doesn’t complete the heist and so never provides a proper aftermath). Topkapi’s flamboyant robbery, involving elaborate subterfuges, dominates the film’s latter stretches, leading to a quick reversal in its epilogue. The heist is finished early on in The Lady Killers, since the crucial action is the long aftermath in which, contradicting the title, the crooks dispose of one another. By contrast, the heist dominates nearly all of Larceny, Inc. Most of the film is devoted to the crooks’ slowly deepening tunnel, as the process is interrupted by breaks in the water main, a geyser of furnace oil, and their decision to abandon their plan in favor of going straight—before another crook comes along to continue the caper.

Or the heist can launch the film. In Plunder Road, after the train robbery is completed, the rest of the film is the aftermath, consisting of chases and suspense sequences. The circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases are alluded to in dialogue, as suits a low-budget production. The plot of Touchez pas au grisbi starts the morning after the caper and shows thieves trying to protect their loot from a treacherous drug dealer. It was probably inevitable that somebody would make a heist movie that keeps the heist offscreen and makes the action one long aftermath.

Steering the moving spotlight

Topkapi (1964).

Many films based on mystery rely on restricting a character’s range of knowledge, as in detective novels told in the first person. But suspense, Hitchcock and others recognized, relies on greater access to story information. If there’s a bomb under the table, Hitch advised, tell the viewer but don’t tell the characters. The heist film, as an account of how a crime is committed, depends more on suspense than mystery. So we’d expect a constant shuttling from character to character, filling us in on how the scheme is going and letting us worry about impending dangers.

This is generally what we find. Criss Cross is unusual in confining us to what Steve knows about Anna’s and Slim’s real agendas, and this confinement is what yields the surprises that pop up in the film’s final stretches. Mostly, though, heist movies and novels use omniscient narration. Employing what I call in Reinventing Hollywood the “moving spotlight” approach, the film shifts us from attachment to one character to another.

The moving spotlight permits us to understand the choreography of the crime, in which many characters play a part, and to feel suspense when matters of timing or accident intrude. Indeed, the convention of the unforeseen accident that spoils the heist relies on our breaking attachment to the crooks and getting privileged access to the off-schedule night watchman, the passing witness, or the failed piece of machinery. In Topkapi we and not the thieves learn how a stray bird will upset their getaway.

This omniscient narration (which need not tell us absolutely everything) can be deployed in a range of ways. One option is chapter titles, as in Big Deal on Madonna Street (and revived by Tarantino in Reservoir Dogs). A more common resource is the non-character narrator, present as an authoritative voice-over. In Bob le flambeur, a worldly male voice introduces us to Bob’s daily routine and comments somewhat cynically on his place in his milieu.

A similar all-knowing voice introduces us one by one to the heisters in The Good Die Young; there it eases the transition into expository flashbacks. Topkapi treats this convention, as others, with self-conscious playfulness. At the beginning the beguiling woman in the gang addresses the camera and explains that the heist aims to get the emerald she covets. She doesn’t take this narrating role again until the very end, in a brief epilogue that replays the gathering of the gang in stylized form.

Heist films must often choose whether to widen the field of view to include either the cops or civilians. Armored Car Robbery (1950), for me a peripheral instance of a heist film, alternates the gang’s activities—which do pass through the phases I’ve outlined—with the detectives’ investigation. The result is balanced between heist film and police procedural. Something similar happens in Violent Saturday (1955), which devotes most of its plot to a gang’s scheme to rob a mining town’s bank. Crosscut with the gang’s gathering and planning are scenes showing several members of the community, each with domestic problems. These scenes, typical of small-town melodrama (dissolute rich people, sexy nurse, repressed librarian, lovelorn bank manager), not only pad out the film but show us characters who will be affected by the heist. Some become witnesses and bystanders during the robbery, one is killed, and one, a local mining manager, will be forced to fight the gang at the climax.

The timing and selection of the shifts among characters can build up specific effects. For instance, in Big Deal on Madonna Street, the heist is conceived by Cosimo, a hardheaded crook doing time. A handful of would-be crooks decides to execute the robbery without him. We know, as the gang does not, that he has been released and is conspiring to interfere. The filmmakers could have made Cosimo’s return a surprise revelation, but instead our expectation that he’ll start meddling intensifies our interest.

Similarly, we know, as the Topkapi gang does not, that Arthur is a police spy. But then he confesses to them, so we know, as the Turkish police do not, that he is to be a double agent. The film milks suspense during the scenes in which Arthur relays information to the authorities, and then it makes us wonder how the gang will use their new knowledge of police surveillance. This is the sort of fine-tuned choice about “who knows what when” that heist films must make at every turn.

At a more granular level, when the spotlight is on one character, the filmmakers must choose whether to make those moments, shot by shot, highly restricted or not. In The Killers, Nick Adams’ account of Ole’s reaction to the stranger stopping for gas is more or less plausibly limited to Nick’s ken. But the precise exchange of glances between the driver and the Swede signal to us that Ole has been recognized. Nick doesn’t register this, since he’s standing at the rear of the car (barely visible in my first still, over Ole’s right shoulder).

In effect, this is a narrational aside to the audience. Nick can’t see this significant exchange of glances, and his voice-over doesn’t specify it, so we can’t assume Riordan learns of it. But this privileged moment primes us to see Big Jim as a major menace in scenes to come. This sort of deviation from what a character could plausibly know or notice is common in cinematic narration and differentiates it from literary narration, which is more tightly restricted in handling “point of view.” Classical Hollywood is biased toward unrestricted narration; radical restriction is rare. The heist genre can exploit many fine gradations between attachment to a character and more wide-ranging knowledge.

What’s our clock?

The Killing (1956).

As we’ve seen, two early instances of heist films break with a linear layout of the story. Criss Cross presents what Reinventing Hollywood calls a crisis structure, beginning just before the turning point and flashing back to show what led up to it. The Killers has a refracted narration, with all of the past events passed to the investigator Riordan and us through witnesses’ testimony. The flashbacks in Criss Cross are chronological, but those in The Killers are drastically out of order.

Time-scrambling, then, seems to be especially welcome in the heist film (as not, say, in the Western). The basic plot pattern is such a simple one that shuffling phases or parts of phases doesn’t create confusion. Yet few films of the 1950s I’ve found display the complexity of the Forties examples. Indeed, a time-juggling heist novel, The Lions at the Kill (Simon Kent, 1959) was ironed into straightforward linearity in the film version, Seven Thieves.

The Good Die Young displays a more complicated structure. It begins at a point of crisis, with four men driving in a car to the site of the caper.

The voice-over narrator introduces each man in turn, and then a long flashback explains his backstory. Deprived of information about the heist, we have to wonder how the narration will bring the men together and create their plan.

After the long section explaining each man’s circumstances, all involving women and money, the flashbacks meld. The men gradually come to know each other through frequenting the same pub. Their desperation pushes them toward accepting one man’s proposal that they rob a post office. With so much time spent on preparation and assembly, the actual planning is necessarily brief. Eventually the final flashback flows seamlessly into the present-time situation, initiating a brief replay of the dialogue in the car that opened the film. The heist (devolving into a disastrous gun battle) initiates the climax, and an airport aftermath concludes the film.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

On the day of the robbery, White’s narration again attaches itself seriatim to each man as he executes his role in the scheme. While the early part of the book had a few mild jumps back in time to follow each heister, the day of the job creates extreme back-and-forth shifts. We follow the bartender, for instance, going to the track on the fateful day, before the next subchapter skips back to the cashier waking up and then going to the same train. In a later section, we skip back to the previous day and attach ourselves to the sniper who will shoot the racehorse. Because of the overlapping lines of action, the shooting of the horse and the starting of the bar fight are presented twice. Everything eventually converges on Johnny Clay, the mastermind, who breaks into the money room and steals the day’s revenue.

These temporal overlaps emerge partly from the description of the action, but they’re also marked by either characters looking at clocks or watches, or by explicit mention in the prose, such as “It was exactly six forty-five when…”

The film version makes these overlapping schedules much more explicit. A detached voice-over describing police routine or criminal behavior had become a commonplace in the 1940s, in both “semidocumentary” films and in radio drama, notably Dragnet. In The Killing, apart from lending an aura of authenticity, the voice-over exaggerates the time markers of the novel by introducing scenes crisply. The first five scenes are introduced with these tags:

“At exactly 3:45…”

“About an hour earlier…”

“At seven PM that same day…”

“A half an hour earlier…”

“At 7:15 that same night…”

These lead-ins remind us of the ticking clock, set up parallels among the characters, and get us acclimated to the film’s method of tracking one character, then jumping back in time to track another. This is moving-spotlight narration on markedly parallel tracks. The same method will be applied during the heist, when ten consecutive scenes and several others will be tagged in the same way. (“Mike O’Reilly was ready at 11:15.”)

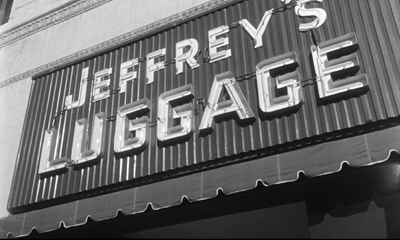

It’s not just the repetitions that exaggerate White’s jagged time scheme. When the sniper Nikki is shot after plugging the racehorse, the narrator reports drily: “Nikki was dead at 4:24.” Cut to Johnny leaving a luggage store, and the voice-over announces: “At 2:15 that afternoon Johnny Clay was still in the city.”

The time jumps more or less buried in White’s prose are made dissonant in the film. Here the juxtaposition heightens the likelihood that Johnny’s robbery won’t go according to plan.

The replays are no less sharply profiled. As the scenic blocks move from character to character and skip back in time, they include actions we’ve already seen. The most persistent is the repetition of the track announcer’s calling the start of the crucial seventh race, but we also get replays of the wrestler Maurice starting a fight, the downing of the horse, and glimpses of Johnny waiting to slip into the cash room.

Instead of shuffling flashbacks in the manner of The Killers, The Killing offers brief time chunks stacked in slightly overlapping array until they all square up in a single moment, the consummation of the robbery. This structure allows for the sort of character delineation we find in The Asphalt Jungle while also offering the audience a formal game to enjoy. Kubrick’s film can be seen as pointing in two directions—revising the flashback format of the 1940s entries, but becoming a point of reference for later filmmakers eager to innovate games with time and viewpoint that would remain comprehensible to the audience.

The Killing helped make Clean Break White’s most famous novel. It was often republished under the film’s title. Perhaps in a grateful spirit White’s 1960 novel Steal Big (1960) included this scene.

Donovan didn’t look at the half-dozen worn, barely legible signs in the dingy lobby of the building. He went at once to the elevator and asked for the fifth floor. Getting out of the elevator, he turned left, took a dozen steps and knocked on a pebbled-glass door. The door bore the legend, KUBRIC NOVELTY COMPANY.

Mr. Kubric, it turns out, supplies illegal guns and explosives.

Art for artifice’s sake

Inside Man (2006).

White’s in-joke, along with The Killing’s gamelike approach to structure, reminds us that whatever its claim to realism, this is a highly artificial genre. The strict template and the ritualistic steps in it—recruiting the crew, casing the target, checking watches—invite filmmakers to tinker with self-conscious narration that lets the viewer in on the joke.

One convention, that of the rehearsal for the big job, is flaunted in Bob le flambeur, when the narrator simply breaks into the film with the line, “Here’s how Bob pictured the heist,” and we get a stylized, hypothetical enactment of the job carried off perfectly. In these films, when the rehearsal goes well, you know the real thing will face problems.

Something similar, though suited to light comedy, takes place in Gambit. Here we think we’re seeing the heist as executed (across twenty-three minutes), but it proves to be no more than the fantasy of the crook hatching it. Again, everything that succeeds in the fantasy goes wrong in reality.

As it gained a profile, the genre got reflexive. In the novel that was the source for The League of Gentlemen, the heisters explicitly model their plan on the one in Clean Break. The film version likewise sets its heisters mimicking a pulp novel, though it didn’t specify the title. And in The Wrong Arm of the Law (1963), Peter Sellers’ cockney mastermind promises to show his henchmen “educational films and training films” like Rififi, The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, and The League of Gentlemen.

The opportunities the genre provides for experimenting with story stratagems, sometimes in very self-conscious ways, seem to have been part of the reason later filmmakers tried their hand at it. In the 1990s and 2000s, writers and directors drawn to neo-noir and narrative experiment took up thriller conventions generally, and the heist film was one option.

In Reservoir Dogs (1992), Tarantino revived the shuffling of time and viewpoint that was ingredient to the genre. Although the film pays homage to Clean Break, its form is no less indebted to Criss Cross. Like that film, it flashes back from the day of the heist in order to run through the canonical phases of action. And as in The Killers, those phases are scrambled out of order. Brian Singer’s The Usual Suspects (1995) brings the (very ‘40s) device of the lying flashback to the genre, within the template of police questioning after the heist. Inside Man (2006) mixed to-camera narration, flashbacks, and flashforwards to interrogations after the crime.

Among Americans it’s Steven Soderbergh who has returned to the caper film most frequently. The Underneath (1995) is a remake of Criss Cross, with an extra layer of flashbacks. Logan Lucky (2017), with its deadpan redneck losers, joins the tradition of comic heist movies. Most strikingly, the Ocean’s series makes a virtual fetish of the male camaraderie and playful plot tricks typical of the genre. The films pepper the action with voice-overs, cunning ellipses, and flashbacks within flashbacks. The plots hide key information about the plan. They fill the action with in-jokes, such as a star cameo by Bruce Willis commenting on box-office grosses. Like 1960s films, they incorporate romantic comedy. In Ocean’s Eleven ((2001) Danny and Tess arrange a post-divorce reconciliation, and in Ocean’s Twelve (2004) Danny’s pal Rusty gets involved with police agent Isabel.

Piling up obstacles, reversals, bluffs, and double-bluffs, the films form a kind of anthology of the genre’s tricks. By the time we get to Ocean’s Thirteen (2007), the early phases of the standard plot schema can be given short shrift. We know the gang and its modus operandi, so the bulk of the film becomes a mind-bogglingly intricate heist including everything from planting bedbugs in a hotel room to manufacturing loaded dice in a Mexican factory under threat of strike. The network of rules and roles laid out in the 1950s—master mind, aged expert, financier, crooked helpers, allies and rivals and go-betweens and stooges—are given baroque elaboration and treated with an almost self-congratulatory panache.

So am I looking forward to Ocean’s Eight? It’s directed by Gary Ross, so I don’t expect Soderbergh’s casual sheen. And the target of the heist, a fashion show at the Met, may be a bit too on the nose; why can’t the ladies tackle a payroll or a munitions factory? Still, like a butterfly collector looking for new specimens, I’m quite curious. When it comes to narrative strategies, I’m a sucker for a fresh con.

Thanks to Jim Healy and Geoff Gardner for discussion of the genre.

Stuart Kaminsky’s American Film Genres: Approaches to a Critical Theory of Popular Film (Plaum, 1974) is a trailblazing study, and the chapter on the “big-caper” film is an indispensible starting point for studying this kind of movie. Later editions of the book eliminated this chapter. A wide-ranging recent survey is Daryl Lee’s The Heist Film: Stealing with Style (Wallflower, 2014). Alastair Phillips offers an in-depth analysis of a classic in Rififi (Tauris, 2009).

My quotations from Donald Westlake come from Murderous Schemes: An Anthology of Classic Detective Stories (Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 1 and 126. I also found the entry on Lionel White in Brian Ritt’s Paperback Confidential: Crime Writers of the Paperback Era (Stark House, 2013) helpful. The “KUBRIC” passage in White’s Steal Big (Fawcett, 1960) is on p. 47. White much influenced Westlake, as I hope to show in a future entry, but Westlake was a far superior stylist, as I discuss a little in this entry. See also this note on Levi Stahl’s anthology of Westlake nonfiction.

For more on analyzing narrative see “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” and “Understanding Film Narrative: The Trailer.” Tarantino’s debts to the 1940s are reviewed in this entry. See as well my recent entry on thrillers. I analyze the convoluted narrative of The Killers in Chapter 9 of Narration in the Fiction Film. The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies discusses 1990s filmmakers’ relation to the Forties. Multiple-protagonist plotting is considered in Chapter 3 of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The concept of schema and revision is considered here as applied to style; this entry, like Reinventing, applies it to narrative principles. My Dunkirk entry points out affinities between the overlapped time frames in The Killing and the three-track scheme Nolan gives us. Unlike Kubrick, Dunkirk applies the principle to the entire film and assigns each timeline a different duration, but it generates a back-and-fill organization and clusters of replays reminiscent of The Killing.

Burt Lancaster is considered here, and why not?

P. S. 26 March 2020: Thanks to Adrian Martin for correcting two slips in my account of Criss Cross!

Ocean’s Eight (2018).

DUNKIRK Part 2: The art film as event movie

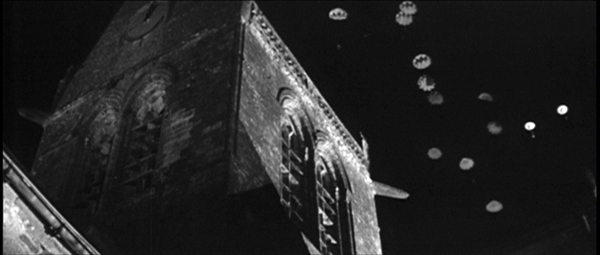

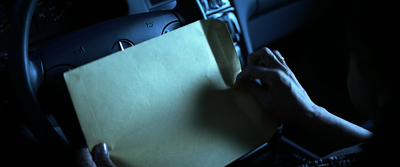

Dunkirk (2017).

DB here:

In some ways Christopher Nolan has become our Stanley Kubrick. Many directors have found ways to turn genre movies into art films; think of Wes Anderson and comedy, or Paul Thomas Anderson and melodrama. But seldom does the result become both a prestige picture and an event film.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Like Kubrick, Nolan moved from the independent realm to an assignment (Insomnia) before being entrusted with a big picture, the first of the Batman reboots. As he developed the Dark Knight trilogy, he made two films in the one-for-them, one-for-me mode (The Prestige, Inception). But Inception became his 2001, a genre hybrid (science-fiction/heist film) that proved that he could turn an eccentric “personal” project into a blockbuster. After The Dark Knight Rises, Interstellar showed that he could make an original genre film that was both prestigious (brainy, based on real science) and an event film. He became another director you want to be in business with. Warners obliged.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

True, Kubrick the former photographer is the more fastidious stylist. You can’t imagine him accepting that his film could be shown in three aspect ratios (as Dunkirk is). The Prestige shows that Nolan can be a precise pictorialist, but as I argue in our little book on his work he’s usually looser at the level of composition and cutting. What he’s interested in above all is narrative.

It’s rare to find any mainstream director so relentlessly focused on exploring a particular batch of storytelling techniques. Like Resnais, Godard, and Hong Sangsoo (a strange crew, I admit), Nolan zeroes in, from film to film, on a few narrative devices, finding new possibilities in what most directors handle routinely. He seems to me a very thoughtful, almost theoretical director in his fascination with turning certain conventions this way and that, to reveal their unexpected possibilities.

Specifically, I think, he’s interested in subjective storytelling, and how it interacts with a very traditional film technique: crosscutting. And he manages to make both fit within a genre framework.

Take Dunkirk. Spoilers ahead.

Field-stripping the war movie

In working on Reinventing Hollywood, I came to realize that the war film bristles with a lot of narrative possibilities. You can focus on a single protagonist, as Sergeant York and Hacksaw Ridge do. Or you can spread the protagonist function to two pals, three comrades, or an entire unit. Mission-team movies like Desperate Journey or The Guns of Navarone can be tightly plotted, but films about ongoing combat can be more episodic, stressing the long slog (The Story of G.I. Joe) or the need to respond to more or less random attacks (Battleground). In most variants, battles and strategy sessions alternate with relatively dead time when the grunts ponder their fate and talk about life back home. Letters from mom or photos of wives and girlfriends are a must.

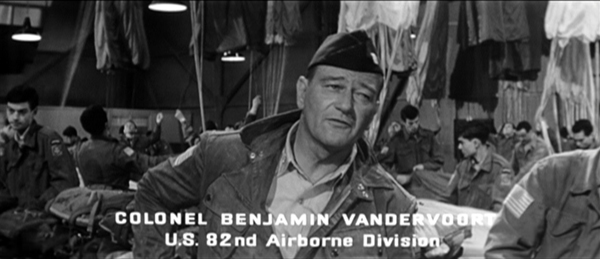

One popular subgenre is the Big Maneuver movie. In The Longest Day the Allies’ landing at Normandy is given as a panorama across nations and a trip through the military hierarchy. The viewpoint sweeps from top brass on both the Allies’ and Axis side to lower-down infantrymen, partisans, and ordinary citizens. Although A Bridge Too Far stresses the generals’ debates about what turns out to be a failed strategy, it too spends time on lower-echelon officers.

In the Big Maneuver movie, certain scenes are conventional. We see briefing rooms fitted out with maps and models of the terrain. Because the cast is vast, officers are sometimes distinguished by titles (as well as being played by instantly recognizable stars).

And when the film’s narration shifts to the grunts, we get quick characterizations that invoke their pasts. Early in The Longest Day, a rosary in an envelope reminds paratrooper Schultz of an incident at Fort Bragg.

Later in the film we’ll find out what this incident was, and what it says about his character.

As many critics have noticed, Dunkirk adopts the framework of the Big Maneuver war movie but it strips away many of these conventions. The only map we can examine, as Kristin mentioned, is the one on the leaflets the Germans are circulating, and for our protagonist the leaflets’ biggest value is as toilet paper. Commander Bolton and Colonel Winnaut are the only brass we see, apart from a brief visit from a Rear Admiral. More important, they’re in the thick of it, not in some safe HQ reading dispatches and pushing toy ships around tabletops.

Just as important, Nolan has purged the characters of backstory. Tommy, Farrier, pilot Collins, the French boy posing as Gibson, and Alex, the angry soldier who attaches himself to Tommy, aren’t given family or memories, nor do they display tokens of home. We don’t even know how Tommy got those scars on his knuckles. Only Mr. Dawson has a bit of a past, and that’s given us late when we learn that his son, an RAF pilot, was killed–thus giving extra motivation to his patriotic urge to help in the evacuation.

While critics complained of too much exposition in Inception, now Nolan gives almost none. In one sense, this laconic presentation is characteristic of the blank spaces we find in “art films,” where character motivation and psychology are often obscure. This is, by Hollywood standards, certainly a sparse war picture. Yet Nolan has spoken of this strategy as reworking a familiar structure. His film, he says, is all climax.

For me, this film was always going to play like the third act of a bigger film. There have been films that have done this in recent years, like George Miller’s last Mad Max film, Fury Road, or Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, where you’re dealing with things as the characters deal with them.

Kristin’s previous entry points out that in her model of classical plot structure, the film is actually both a Development and a Climax–that is, parts three and four. A Development section consists of obstacles and delays, which comprise most of the action of this film before the climactic bomber attack. Still, Nolan’s point is well-taken. In most climax sections (third acts), we know everything we need to know about the action. All the relevant motivations and backstory have been supplied in the earlier stretches, so we can concentrate solely on what happens next. In Dunkirk, we don’t see those prior sections, so we’re plunged into the prolonged suspense characteristic of climaxes.

The war movie as thriller

Granted, suspense is an ingredient of any war picture. Alongside GHQ debates about strategy, the Big Maneuver movie includes episodes aiming at momentary tension. The dive into the French village in The Longest Day offers the painful spectacle of men being shot down like a flock of geese, while A Bridge Too Far shows Urquhart (Sean Connery) trapped in a Dutch household as Nazis surround him.

Nolan’s strategy, though, is to make virtually the entire film an exercise in suspense. He understands that pure suspense doesn’t require us to like or even know a lot about the characters. We can feel tension in relation to characters we don’t like (e.g., Bruno’s reaching for the lighter in Strangers on a Train) or characters we don’t know much about at all.

Dunkirk offers a cascade of primal dangers, an anthology of narrow escapes and last-minute rescues.

The whole film is a race against time, enclosing mini-races. Nolan plays on fears of being crushed, swallowed by darkness, blasted to bits, and shot out of the sky. How many ways can you drown–in a sinking ship, under a flaming oil slick, inside a Spitfire cockpit? The appeals are elemental and irresistible; a child of five could understand the dangers here. This catalogue of stark situations takes us straight back to silent cinema, to cliffhangers, Griffith rescues, and Lang’s dungeons filling with water. Nolan points out:

Dunkirk is all about physical process, all about tension in the moment, not backstories. It’s all about ‘Can this guy get across a plank over this hole?’

Those who want films to focus only on higher things, big ideas or subtle emotions, miss the visceral dimension of cinema. It’s led critics to avoid analyzing musicals, cop thrillers, Asian martial arts films, and Eisenstein’s action sequences. (Ritual invocations of The Body notwithstanding.) The Battleship Potemkin, Police Story, The Raid: Redemption, and much other excellent cinema happily passes The Plank Test.

Does this make the film superficial? Nolan explains that even in the absence of characterization, suspense triggers involuntary, universal responses. Consider Tommy trying to run across the plank.

We care about him. We don’t want him to fall down. We care about these people because we’re human beings and we have that basic empathy.

In creating the suspense, Nolan went, as he puts it, “in a more Hitchcock direction.” That entails, for reasons we’ve talked about here and here, playing between restricted and more unrestricted point of view. Not only do we not see the GHQ strategizing, we aren’t taken into the enemy camp. From the start, when gunfire drives Tommy down the Dunkirk streets, the attacks come from offscreen. Only at the very end will a couple of blurry Nazi-shaped figures appear behind the captured pilot Farrier.

In the end, the key for me was reading a lot of firsthand accounts of the people who were there. It became apparent to me that the subjective approach — really putting the audience on the beach with the characters, putting them in the cockpit of the plane, putting them on one of the boats coming across to help — that was going to be the way to tell the story and get across this much bigger picture.

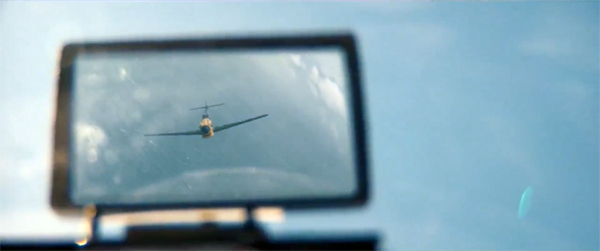

To drive home what it feels like to just barely get by, Nolan ties us tightly to Tommy the foot soldier, Mr. Dawson and his son Peter on their boat, and Farrier the Spitfire pilot, with side visits to Commander Bolton on the Mole. Sometimes he supplies optical POV shots, but more generally he simply confines us to what happens in these men’s ken. The result is both surprise–when the bullets or bombers appear–and suspense, when we cut between Tommy and other soldiers swamped below deck while Gibson struggles to open the hatch and free them.

Even the clicking shut of a cabin latch–or not clicking it shut–generates tension, heightened by the ticking of Zimmer’s score. (At times I thought the pulse in my skull was synched up with the metronomic soundtrack.) The emblem of Nolan’s narrational strategy might be the pitiless shot surmounting today’s entry, showing Tommy flattened while bombs drop one by one behind him, coming inexorably closer to the foreground. Nolan turned superhero films, science-fiction films, and fantasy films into ticking-clock thrillers, and now he does it with a war movie.

The limiting of viewpoint links to some of Nolan’s perennial concern with subjectivity, I think, but it’s also there as a strain within the tradition of war fiction and film. Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front is like a diary, told in first-person present tense but with flashbacks in the past tense. Catch-22 is in long stretches tied to Yossarian’s jumbled memories of flight missions and hospital stays. Terrence Malick’s adaptation of The Thin Red Line, a film Nolan much admires, turns James Jones’ third-person novel into a lyrical fantasia on war as both a violation of nature and an extension of it, with flashbacks and brooding soliloquys. But in Dunkirk Nolan avoids the deeper registers of subjectivity he’s explored before–no memories, no dreams or fantasies, just brute happenings and the stubborn physical demands of earth and rock and water.

The viewpoint range isn’t as narrow as I’ve suggested, though. Nolan broadens his scope by cutting back and forth among the subjective stretches. Again, this is standard operating procedure in the Big Maneuver film. But that crosscutting was never like this.

Time out from battle

Dunkirk, sans credits, runs a little more than 99 minutes and consists of around 99 sequences. It’s very fragmentary. But then, so is a lot of war fiction. All Quiet consists of many fairly short scenes. Evelyn Scott’s vast novel The Wave (1929) surveys the US Civil War through over a hundred vignettes of the home front and the battlefront, involving characters mostly unaware of each other. William March’s Company K (1933) consists of 113 short segments, each bearing the name of one soldier and told in first-person by him (even if he dies in the course of the episode). Unlike what happens in The Wave, the men are mostly known to one another, and some actions are replayed through different viewpoints. A fancier sort of fragmentation goes on in Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (1948), which interrupts its scenes with flashbacks (“The Time Machine”) and sections called “Chorus.”

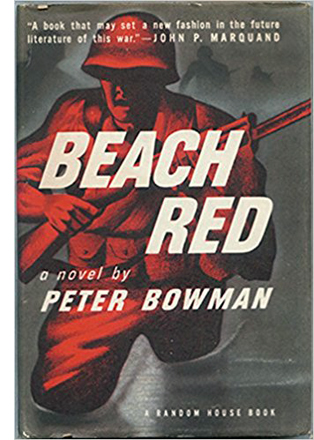

T he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

His novel is in blank verse, in stanzas of varying length but all conforming to a strict pattern. Each line is equal to one second of story time. Each chapter consists of sixty lines, or one minute of story time. And the book has sixty chapters, representing the hour in which the forces take the beachhead. Like Nolan, Bowman wants a deep, visceral subjectivity, and he aims at this through a frankly mechanical layout of his text. The rigid pattern seeks to force the reader to sink into time. Bowman explains:

I have tried to create a mood of inexorable regularity that would correspond to the subtle tyranny of the military timetable. . . . I have attempted to do for the eye what the ticking of a clock accomplishes for the ear. . . the relentless inflexibility of time itself.

The aching inching forward of time is stressed thematically too, which includes reflections like “Would there be armies if clocks had never been invented?” The book ends with the second-person narration (“You”) dying. Soldier Whitney reports: “There is nothing moving but his watch.”

Like Bowman, Nolan is interested in both the psychology of time and the problem of representing it in his artistic medium. I maintained in our book on Nolan that he isn’t only interested in shuffling chronology. I think that he’s particularly keen on exploring what the technique of crosscutting does to story time.

He has explained that he got the idea from Graham Swift’s 1983 novel Waterland.

It opened my eyes to something I found absolutely shocking at the time. It’s structured with a set of parallel timelines and effortlessly tells a story using history–a contemporary story and various timelines that were close together in time (recent past and less recent past), and it actually cross cuts these timelines with such ease that, by the end, he’s literally sort of leaving sentences unfinished and you’re filling in the gaps.

Crosscutting would become a central artistic strategy for Nolan, a way of shaping his other storytelling choices.

Admittedly, what strikes you first about Memento is its flagrant exercise in reversing story order. But that 3-2-1 sequencing is accompanied by a counterpoint, that of chronologically advancing time, 1-2-3 in the present. Backwards-moving sequences are crosscut with forward-moving ones. Likewise, the structure of Following stems from treating phases of a single action as different story strands which can be crosscut. And the shuffling of order in The Prestige comes from intercutting stretches of two characters’ lives in complicated polyphony.

In his last three films, I think that Nolan, intuitively or deliberately, has hit upon an important feature of conventional crosscutting. Nearly all crosscutting in fictional cinema presumes different time spans, or rather different rates of change, in the crosscut lines of story action. We presume that overall the actions are simultaneous, but at a finer level, they proceed at different speeds. Some parts of the action in one line are skipped over, while other actions in another line are prolonged.

This disparity can be seen in some of Griffith’s classic sequences. In The Birth of a Nation, the black soldiers are inches away from breaking into the cabin’s parlor while the Ku Klux Klan is riding to the cabin, but the riders are miles away. If both strands were on the same clock, the Klan would arrive much too late.

Crosscutting allows Griffth to skip over the distance that the Klan covers, so the riders arrive at the cabin “implausibly” fast. Correspondingly, the glimpses we get of the cabin stretch out the action “unrealistically.” To put it technically, we get ellipsis in one line of action, expansion in the other.

Nolan does the same thing in his crosscut sequences. Consider the passage in The Dark Knight when the judge opens the Joker’s fake message. One or two seconds in her timeline are stretched while Gordon’s conversation with Commissioner Loeb runs on a different clock, consuming several seconds. And when Harvey Dent talks with Rachel and is grabbed by Bruce, that action takes even longer.

To speak of different clocks is a bit misleading; we can’t think that the judge turns over the envelope in super-slo-mo. But the idea of different rates of unfolding is useful because it reminds us that crosscutting aims to convey an overall impression of simultaneity. When we look closer, we realize that the action in one story line can be slowed or accelerated while another story line is onscreen.

Nolan’s interest in this quality of crosscutting is literalized in Inception, in which embedded dream actions unfold at different speeds on different levels. In Interstellar, cosmology motivates crosscutting between slow and fast rates of change. In the first planet the astronauts visit, one hour is equal to seven years on earth, so characters literally live at different rates. The pathos of the film depends upon the fact that Cooper returns, barely aged, to his daughter, to find an old woman on her deathbed. But the differential also allows Cooper to appear to her as the ghost that she saw in childhood and, in circular fashion, set him off on his mission.

The war movie as puzzle film

Nolan notes for Interstellar.

For Dunkirk, Nolan found another way to highlight the rate differences secreted within crosscutting. Like Bowman in Beach Red, he lays down crisp time markers. Farrier’s combat sortie lasts one hour; Dawson’s rescue efforts at sea last one day; and events around the breakwater (the Mole) are said to consume one week. The actual evacuation ran longer, but Tommy and his pal aren’t the last to leave.

These three stretches of action could have been presented as separate blocks. We might have been attached first, say, to Dawson and his boat to attain a pitch of excitement during the bombing of the minesweeper. Then we could flash back to Tommy at the start, in a long lead-up to being rescued by Dawson. Finally we could cover the same events yet again by starting with Farrier’s aerial combats and tracing his fate. The film could have concluded with an epilogue showing Tommy and his pal safely on the train.

Interestingly, Kubrick explored this creative option to a limited extent in The Killing, his 1955 adaptation of Lionel White’s Clean Break. As in the novel, one string of scenes sticks with one participant in a racetrack robbery. Then we jump back in time, guided by a voice-over narrator (“About an hour earlier…”) and follow another man leading up to the situation we’ve already seen. Tarantino did the same block-shifting in Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown, and he (rightly) noticed it as a standard literary technique.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action. . . . Flashbacks, as far as I’m concerned, come from a personal perspective. These [in Reservoir Dogs] aren’t, they’re coming from a narrative perspective. They’re going back and forth like chapters.

But Nolan avoided block construction and went for braiding. He splintered his story lines and crosscut them. Events that are mostly taking place at different times are, as it were, laid atop one another and offset. Crosscutting en décalage, we might say.

I’m struck by how bold this is. A more conventional choice would be to confine the action to a fairly brief stretch of time, say two hours, with the rescue fleet arriving at the climax. There might even have been an effort to handle the action as occurring in “real time,” that is, with the duration of the scenes matching their duration in the story. In any event, Nolan could have crosscut his four men–Farrier in the air, Dawson and others at sea, Bolton and Tommy around the Mole–at the points when their activities are roughly simultaneous. If Nolan wanted to include earlier incidents, such as Tommy’s escape from the Germans or his efforts to board the Red Cross ship, those could have been presented as personalized flashbacks. Instead, all that material appears in chronological scenes, but on three distinct time scales.

Nolan set himself enormous problems with this choice. He chose to show the time frames without recourse to an onscreen calendar or clock; after the three initial titles indicating the places and the time spans, we get no more explicit markers. Then Nolan faced the problem of how, on a finer-grained level, to gather these fragments into a whole. He had to create parallels, and, eventually, convergences.

So early in the film, Tommy and Gibson run a stretcher to the departing Red Cross ship.

Cutting makes their urgency flow into that of Mr. Dawson hastening to cast off before the navy requisitions the Moonstone.

Forty-five seconds later Farrier’s team is sent to Dunkirk.

In story time, of course, these aren’t simultaneous at all. Tommy’s attempted escape happens days ahead of Mr. Dawson’s departure, which is hours ahead of Farrier’s mission. But Nolan, aided by Hans Zimmer’s endlessly propulsive score, has given all three primary roles in launching the film’s plot, the start of a time-gapped fugue.

That sort of primacy works at a higher pitch when two life-or-death situations are intercut. Tommy, Alex, and some other soldiers have rashly taken shelter in a fishing trawler, hoping that the tide will carry them away from the beach. But they get pinned inside by target fire. The tide has indeed pulled them out to sea, but the hold is taking on water–at the “same time” (not) that Collins, trapped in the cockpit of his ditched plane, is himself about to drown. The two scenes are intercut.

At the climax, the gestures of rescue are exuberantly crosscut: Dawson hauling on the oily survivors of the blasted minesweeper, the civilians helping the stranded soldiers clamber aboard their boats.

In this passage, Nolan daringly cuts single shots of Dawson’s Moonstone moving as if in sync with the impromptu flotilla, even though he’s some distance off; the crosscutting makes him visually one of the fleet near the Mole.

Crosscutting can also dial up the suspense by delaying the outcome of a line of action. Farrier’s dogfights are pretty much incessant, so cutting away from them to more placid action on the beach or in Dawson’s boat postpones their outcome. Nolan points to another advantage of intercutting the different periods:

You have three different intertwined storylines, and you have them peaking at different moments, so that the idea is that you always feel like you’re about to hit–when you’re hitting the climax of one episode of the story . . . then another one is halfway through and the other one is just beginning. So there’s always a payoff.

Nolan compares this to the “corkscrew” effect of the Shepard Tone in music, which David Julyan used in the drone soundtrack of The Prestige.

At other points, the crosscutting uses one line of action to explain another. While Tommy and Gibson take refuge in the second ship, the Shivering Soldier tells Dawson he refuses to return to Dunkirk because his ship was hit by a torpedo. Soon enough we see a torpedo rip open the ship and plunge Tommy, Gibson, and Alex into the night sea. And soon after that, when they try to clamber into a lifeboat, they’re told by an officer to stay in the water: it’s the Shivering Soldier, pre-PTSD. The contrast between his cool efficiency near the Mole and his spasm of cowardice on the Moonstone is another proof of war’s disastrous impact on warriors.

The lines of action, segregated by crosscutting, intersect eventually. Farrier’s teammate Collins ditches his plane and is rescued by Dawson; later Tommy will get on the Moonstone as well. These are staggered a bit in the film’s unfolding, having the effect of replays. At at least one point, though, I think that all three lines converge. One moment unites Farrier shooting down the German bomber, Dawson steering his ship away from the falling plane, and Tommy, dragged along underwater and hauled to the deck. Shortly the realms of Air and Mole converge when Bolton sees the German plane go down and his men cheer Farrier’s plane as it glides past.

After these moments are briefly pinned together (the script calls it the “confluence”), the time scales diverge again. The epilogue phase of the film resets each strand’s clock. The rescued men arrive at Dorset, and Tommy and Alex board a train at night. Back at the Mole, it’s still daylight and we can see Farrier’s plane burning in the distance. A day or so later in Dorset, the newspaper has published a tribute to George. Now we see Farrier days before, still within his allotted hour of story time, guide the plane down, step out, and set fire to it, as Tommy reads from Churchill’s speech.

Three viewings of the film weren’t enough for me to catch all the alignments, shifts, and echoes, the glimpses of things that take on importance only retrospectively. Early on, a distant shot of Collins’ downed plane briefly shows what turns out to be the Moonstone chugging towards it. On first viewing I was puzzled by Farrier’s view of a sinking private ship; only on the second pass did I realize that it’s the blue trawler that we’ll later see the young soldiers hiding in and fleeing from. And it’s likely, even with many pages of notes, that I’ve mistaken some of the juxtapositions that fly by. (The film averages about 3.3 seconds per shot, and sometimes we jump across story lines in a fusillade of alternations.) Like other puzzle films, the film demands rewatching and scrutiny, and it merits it.

In all, Nolan has taken the conventions of the war picture, its reliance on multiple protagonists, grand maneuvers, and parallel and converging lines of action, and subjected it to the sort of experimentation characteristic of art cinema. (As, in a way, Bowman’s time-grid in Beach Red anticipates the rigor of the Nouveau Roman.) Nolan exploits one feature of crosscutting: that it often runs its strands of action at different rates. He then lets us see how events on different time scales can mirror one another, or harmonize, or split off, or momentarily fuse. As a sort of cinematic tesseract, Dunkirk is an imaginative, engrossing effort to innovate within the bounds of Hollywood’s storytelling tradition.

The juxtapositions aren’t just fancy footwork, I think. In this film, because of the imminence of danger, heroism gets redefined as luck and endurance.

A cynic could call the movie Profiles in Cowardice. Tommy flees German bullets and instead of helping the French hold the barricades, he keeps running. The French boy steals boots and an identity in order to get off the beach sooner. He and Tommy try to slip on board a departing Red Cross ship as stretcher bearers. When that fails, they hide among the pilings. When the ship is hit, they leap into the water, the better to pretend to have been among the survivors and get a new ride. The Shivering Soldier wants to cut and run, and the soldiers who drift beyond the perimeter plan to use the blue trawler to carry them to safety, jumping the evacuation queue. All too often, despite acts of aid and comfort, it’s every man for himself.

At one point Alex claims “Survival’s not fair.” Too right. Mr. Dawson risks his and his son’s life to save a few men, while the lad George, who joined them on impulse and promised to be useful, dies before he can do much, accidentally killed by the Shivering Soldier. The closest the film comes to standard war-movie heroics is Farrier’s cutting down Stukkas. And he doesn’t make it back.

By plunging Tommy and his counterparts into almost unremitting peril, Nolan’s suspense tactics lower the bar for heroism, making us hope that they simply get away, somehow. Trapped on land and sea, you can’t fight dive bombers, U-boats, and marksmen squeezing in from the perimeter. At the end, the boys disembarking at Dorset are reassured that survival was enough. And thanks to Nolan’s crosscutting, individuals at different points in time are shown pulling together to make retreat its own victory.

I wrote nearly all this entry before I got a copy of the published screenplay. Reading Nolan’s conversation with his brother there enabled me to add the quotation about catching lines of action at different points (p. xxii). This conversation also considers the reasons Nolan omitted GHQ scenes (mentioning A Bridge Too Far) and adds comments about Hitchcock, early sound filming (some mistakes here), and The Thin Red Line (“maybe the best film ever made,” xiii). As far as I can tell, the screenplay is fairly close to the finished film until the climactic bombing of the minesweeper; at that point, the onscreen editing doesn’t completely match what’s on the page.

Speaking of climaxes, I should add that even though the film is in Nolan’s sense “all climax,” it also falls quite nicely into Kristin’s four-part structure. I think the midpoint comes when Tommy and his mates head to the blue trawler, starting a typical Development section.

My quotation from Tarantino comes from Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (New York: Applause, 1995), 69-70. The Nolan quotation about Waterland comes from Jeff Goldsmith, “The Architect of Dreams,” Creative Screenwriting (July/ August 2010), 18-26 (available, sort of, here).