Archive for the 'Film history' Category

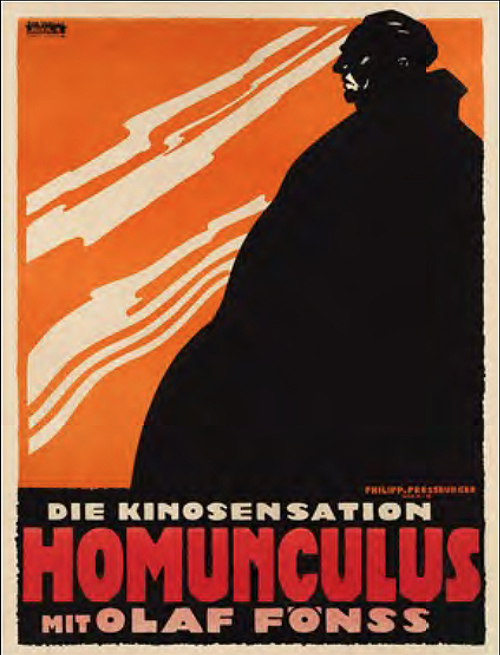

The return of Homunculus

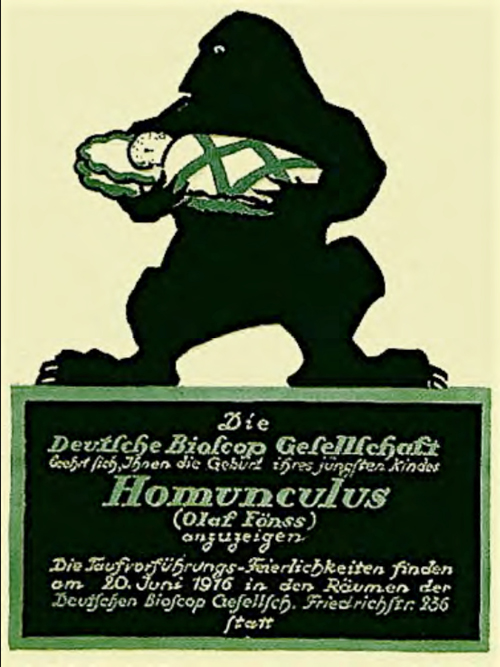

On 21 November, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will be screening a version of Otto Rippert’s long-lost German serial Homunculus (1916). It was reconstructed by Stefan Drössler and his colleagues at the Munich Film Museum on the basis of material from the Moscow Film Archives and other collections. Here’s the background offered by the opening titles on this version.

Homunculus was shown as a six-part series in movie theaters in Germany and its occupied territories in 1916, in the midst of World War I. Each episode was about an hour long. In 1920 the opus was reissued as a three-part version. Scenes were shifted around and new intertitles added.

The following reconstruction adapts the structure of the reissue edition, but it also contains some scenes that had been shortened for the later version and often only survived as photographs.

Fewer than 20% of the original German intertitles have been preserved or are known in their exact wording. Newly worded texts for this reconstruction were based, when possible, on information from contemporary program notes and reviews; also, some were translated back from foreign-language versions of the film and others were created from keywords scratched into the film as montage cues.

For the first time, the current work print makes it possible to recognize the original concept of the entire series.

Today, as a preparation for this very important event, each of us offers you something. First Kristin sketches the trend of fantasy filmmaking in German cinema of the 1910s. After providing this context for the film, David offers some thoughts on this new version of Homunculus and its value for us today.

Kristin here:

The seeds of Expressionism

Many viewers who come to Homunculus for the first time may be expecting traits of the most famous German silent film trend, Expressionism. And indeed historians have mentioned Rippert’s serial, along with Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague, 1913), Hoffmanns Erzählungen (Tales of Hoffman, Richard Oswald, 1916), and others, as forerunners of the Expressionist movement.

But we don’t have a very concrete account of how these earlier films led up to the more famous trend that began with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’s release in early 1920. Moreover, at first glance there aren’t many visual qualities in these earlier films that remind you of Expressionism. They display few or none of those Expressionist distortions of mise-en-scene influenced by contemporary trends in painting and theatre. Similarly, the acting, while exaggerated in a fashion common during the 1910s, seldom reaches the extreme stylization of the performances in Expressionist films.

Yet there are clearly some other similarities between the two groups of films. Most obviously, the early films brought to prominence two related genres to which many of the Expressionist films would belong: the phantastischen film and the Märchenfilm, or fairy-tale film.The main examples of the latter all starred Paul Wegener: Rattenfänger von Hameln (The Pied Piper of Hameln, 1918), Hans Trutz im Schlaraffenland (Hans Trutz in the Land of Cockaigne, 1917), and Rübezahls Hochzeit (Rübezahl’s Wedding, 1916).

For Expressionist filmmakers, elements of the supernatural or the legendary could motivate highly stylized mise-en-scene. In contrast, these 1910s films often used relatively realistic mise-en-scene. Location shooting, straightforward period costumes, and skillfully executed trick photography introduced the fantastic elements into the milieu of a concrete, seemingly everyday world.

A changing view of cinema

Despite such differences, the two genres provide a specific link between some of the most prominent German films of the 1910s and those of the Expressionist movement. Moreover, fantasy films seem to have provided a basis for at least a tentative exploration of theoretical issues surrounding the relationship of cinema to the other arts. In Germany, cinema had previously been compared primarily to literary and theatrical arts, but Wegener’s Der Student von Prag and other films led to a wider consideration of cinema in relation to visual arts such as painting.

In a 1916 lecture, Wegener expressed dissatisfaction with most of what had previously been done with the cinema. He sought to establish the cinema as an independent visual art, separated from theatre and literature:

When a new technology is developed, it is initially cultivated in relation to existing ones, and a new idea does not immediately find its own unique form. The first steamboats looked like big sailing schooners, except that instead of masts they had high funnels. The first railway cars copied mail coaches, the first automobiles kept the large bodies of landaus, and the cinema was like pantomime, drama, or the illustrated novel.

A more broadly based view of the cinema as combining theatrical and graphic arts created a newtradition which carried over from the 1910s to the Expressionist movement of the 1920s. These early films may have become models for the development of an “art cinema” movement in the next decade.

The painterly approach to film promulgated by Wegener lingered in German cinema for about a decade. Starting around 1924, a new approach, based on the moving camera and a more realistic three-dimensional space, would largely replace the older one.

Frames and books

Der Student von Prag.

Aside from this specific link created by Wegener’s emphasis on the pictorial powers of the camera, several conventions of the fantasy films of the 1910s look forward to Expressionism. Perhaps most notable among these devices is the use of the frame story.

Expressionist films frequently employ this device: Francis’ tale to the fellow asylum inmate in Caligari, the record of the Bremen town historian in Nosferatu (as well as the imbedded narratives of the Book of the Vampyres and the ship’s log), the young poet hired to write publicity anecdotes for a sideshow in Wachsfigurenkabinett, and so on.

Yet this pattern was already well established during the 1910s. Der Student von Prag begins and ends with a poetic scroll (“Ich bin kein Gott/bin kein Dämon …”), with the final return leading to a shot of Balduin’s gravestone—upon which sit the Doppelgänger and a crow. (The 1926 remake, which has some distinct Expressionist touches, begins and ends with a gravestone that summarizes Balduin’s life.) Wegener’s other major surviving film from the mid-1910s, Rübezahls Hochzeit, begins with a scene of Wegener, as himself rather than in character as the titular hero, reading to a group of children from a book entitled Rübezahls Hochzeit.

In some cases the frame story introduces multiple embedded narratives. Richard Oswald’s two main fantasy films of the pre-1920 era, Hoffmanns Erzählungen (1916) and Unheimliche Geschichten (Uncanny Stories, 1919), both use this technique. The first begins with a prologue showing Hoffmann surrounded by strange characters like Count Dapertutto and Coppelius. Three dream sequences show him incorporating these figures into bizarre stories; the transition from the prologue to the the main portion of the story begins with Hoffmann in bed as the three sinister figures stand over him.

Unheimlische Geschichten begins, as an intertitle announces, with “A fantastic Prologue at an antiquarian book dealer’s.” On the wall are three large pictures depicting a whore, death, and the devil. After the proprietor chases away his customers and departs, the three images come to life and amuse each other by reading tales out of a book. The series of embedded tales, adapted from Poe, Hoffmann, and other authors of the uncanny, form the bulk of the film.

Not all fantasy films of the 1910s contain frame stories or embedded narratives. Characters do, however, often read or write books that contribute major premises or motifs. In Homunculus, Richard Ortmann keeps a large diary, which records his shifting and somewhat contradictory thoughts, feelings and goals—and thus conveys them to us. Joe May’s Hilde Warren und der Tod (Hilde Warren and Death, 1917) also has no frame story. Its opening, however, involves the heroine reading in a book that death is an escape from sadness. This notion becomes a motif, as the figure of Death appears to her at intervals, foreshadowing her eventual surrender. Books would become an important motivating device in Expressionist films, introducing embedded narratives or crucial motifs.

Hilde Warren und der Tod also carries through the pictorial tradition of Der Student von Prag. Here the special effects are not used to allow one actor to play two roles through split exposure. Rather, superimpositions introduce the figure of Death into the everyday scenes of Hilde’s life.

Some early hints of Expressionism

Although the fantasy films of the 1910s don’t contain strongly Expressionist elements, a few stylistic touches foreshadow the distortions of the later movement. Some of these relate to performances by actors who were to become central to the Expressionist movement. In Hoffmanns Erzählungen, for example, Werner Krauss’s stylized acting in the role of Count Dapertutto suggests why he was later cast as Dr. Caligari. Conrad Veidt’s acting and especially his makeup as Death in Unheimliche Geschichten mark him as the ideal candidate to show up in Caligari’s cabinet.

The stylized hand gestures in these two shots are particularly striking, and the same device is carried through in a séance sequence in Unheimliche Geschichten. The lighting of the séance looks forward to more famous scenes in Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), and The Ministry of Fear (1944)—yet here Oswald introduces a twist by including one more hand than there should be for the number of bodies present.

There are other major films made in 1919 which contain stylistic and generic elements soon to become far more prominent. Lang’s Die Spinnen (The Spiders, 1919-1920) draws upon conventions of the thriller serial which would soon by transmogrified in his Expressionist film, Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler. Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (The Puppet) and Die Austernprinzessin (The Oyster Princess), both 1919, could be counted as comic Expressionist films that introduced the style into the cinema months before the appearance of Caligari. The exact cut-off date between pre-Expressionism and Expressionism proper is not vitally important. Some 1910s developments in genre and style prepared the way for Expressionism. Caligari, however great its stylistic challenges were, did not appear in a vacuum.

DB here:

Wanted: Love. #Homunculus

The 1920 reissue of the Homunculus serial compresses its original story considerably, but the outlines are clear. Some omissions in the Munich reconstruction may reflect gaps in the 1920 version. Still, the basic outline of the tale is clear.

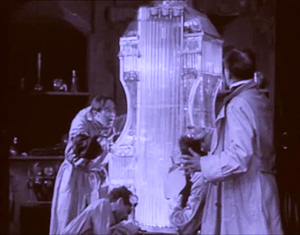

Very likely the first test-tube baby, the Homunculus arrives on the scene as the result of a pseudoscientific effort to create life. Out of a bubble, properly zapped, comes an infant.

The baby is brought up in an ordinary human family, thanks to the classic switched-in-the-cradle device. Known as Richard Ortmann, the creature grows up into something of a superman, with extraordinary strength and explosive energy. But his core is hollow. Richard discovers that he lacks fellow-feeling and finds himself alienated from his carousing peers.

When Richard discovers his technological origin, he sets himself a drastic choice: either discover human love or destroy this worthless world.

Each episode replays the same dynamic. Somewhere Richard discovers a possibility of uncorrupted love. But that prospect shatters, either because of prejudice (would you want your daughter to marry a homunculus?) or his sadistic urge to plunge the world into chaos. Only his friendship with Edgar Rodin, one of the scientists who attended his birth, forms an enduring bond across the episodes.

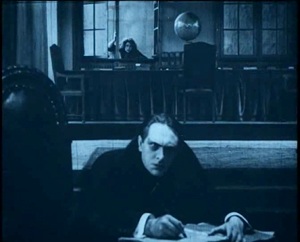

Richard Ortmann plays many roles in his saga. He’s a scientific tinkerer who invents an explosive, a wanderer who ventures into Africa, and a capitalist who enjoys masquerading as a rabble-rouser bent on fomenting rebellion. No sooner has he provoked a war than he tries his own social experiment, that of isolating a young couple in hope of breeding a new society. All these exploits he records in a mighty book

This tome becomes a handy narrative device when the plot demands that other characters learn of his inhuman origins.

Like those films that clone a Stallone or a Van Damme, the series realizes that one monster can be defeated only by another one. The long tale comes to a climax when Rodin creates a second Homunculus and raises him up to conquer Ortmann–already somewhat weakened from age and fear of death. The titanic confrontation is played out on mountain craigs.

Who will win? Or will both perish?

Annihilation, courtesy Homunculus

The rocking-horse rhythm of the episodes, with hope for Ortmann’s redemption rising and inevitably falling, takes some getting used to. To the filmmakers’ credit, they vary the prospects for love: an array of women, a dog, and in the fourth episode a woman who wholeheartedly embraces Ortmann’s wicked side.

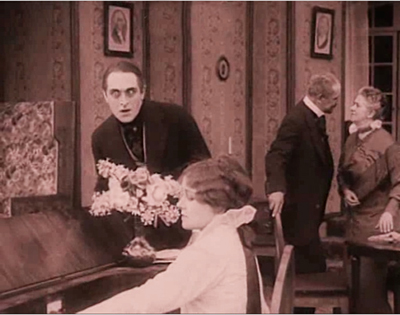

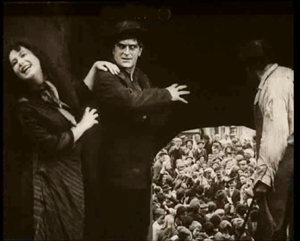

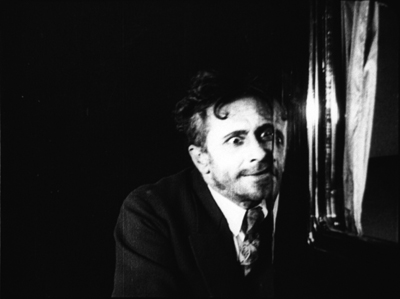

Today’s viewers will also need to accustom themselves to the seething extremes of Olaf Fønss’s performance. Fønss was a major Danish actor who became famous in Atlantis (1913) and who migrated to Germany to star in this series. Fønss conceives his performance as a matter of ferocious glares, raised fists, and heroically villainous postures. It looks overdone to us today.

His box cape, reminiscent of bat wings, helps the brooding effect.

But this isn’t merely a matter of old-fashioned hamming. Fønss’s performance is calibrated to be ragingly different from the other portrayals. Most of the actors exaggerate less, and the pacifist preacher actually underplays. Fønss goes over the top because Homunculus does.

What makes the series compelling? For one thing, it offers a fairly original reworking of the Frankenstein premise. For another, its central conceit of a mad, misunderstood supervillain in search of love can evoke some empathy. There’s also the effort to convey a world in flames, to suggest a cosmic catastrophe with minimal means. While the Great War devastates Europe offscreen, one can hardly avoid thinking of trenches and bombardment in blasted shots like these–which also look forward to the jagged decor of Expressionism.

The student of film technique will, I think, be struck by the filmmakers’ pictorial ambitions. It’s now clear that by focusing just on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) we have limited our sense of the wide-ranging visual discoveries of German cinema. Homunculus belongs with the splendid string of films that includes Der Tunnel (1915), Algol (1920), I.N.R.I. (1920), and the outstanding pair of 1919 films by Robert Reinert, Opium and Nerven. Reinert, unsurprisingly, wrote the screenplay for Homunculus.

The fourth episode, which I commented on back in the summer (based on a much inferior copy), remains a treat for your eyes, with unexpected camera angles and daring use of depth. In the one on the left, we see touches of Expressionist performance in the orchestration of hands.

Elsewhere Kristin has remarked that during the 1910s filmmakers began to go beyond basic storytelling and explore the expressive dimensions of cinema—not only in acting but also in composition, lighting, and set design. The Jugendstil curves of the incubator gleam inside a cavernous chamber you might not expect to find in a lab.

Other episodes provide both grand images—landscapes, sumptuous sets, crowd scenes—and an arresting, small-scale play of light and shade. A purely expository shot of Ortmann approaching Steffens’ study becomes a little suite of shadow patterns, stressed when Ortmann pauses and swivels to the camera and creates a pictorial climax.

Seeing the three-dimensional lighting effects of German cinema of the mid-1910s onward, I wonder whether Caligari‘s jutting, broken-up planes and painted shadows are not only a borrowing from Expressionist painting but also a reaction against the rich volumes created by directors like Rippert.

In all, Stefan Drössler and all the archives and individuals working with him have done world film culture a great service. As with Gance’s Napoleon and Lang’s Metropolis, more footage may appear and need to be integrated into this version. Perhaps some day we’ll have something approaching the full scope of the original series. For now, we should be thankful that another silent classic steps out of the shadows and forces us to rethink what we thought we knew about the history of cinema.

Many thanks to Stefan Drössler for his assistance in preparing this entry.

At Nitrateville Arndt has posted helpful synopses of all six parts of the restoration. Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel (Amsterdam University Press, 1996), pp. 160-167. Excerpts can be found here.

Kristin’s discussion of fantasy films is excerpted from her essay “Im Anfang War…: Some Links between German Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” in Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Bibliotexa dell’Immagine, 1990), 138-161. The Wegener quotation is from Paul Wegener, “Die künsterlischen Möglichkeiten des Films,” in Kai Möller, ed., Paul Wegener: Sein Leben und seine Rollen (Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag, 1954), p. 102. Translation by KT.

Elsewhere on this site we discuss other neglected German films of the period: Der Stoltz der Firma (The Pride of the Firm, 1914); Der Tunnel (1915); Asta Nielsen features of the teens; Doktor Satansohn (1916); Hilde Warren und der Tod (1917); Die Pest in Florenz (The Plague in Florence, 1919, directed by Rippert after Homunculus); late-1910s Lubitsch; Algol and I. N.R.I. (both 1920); and Der Golem (1920). I have an essay on Robert Reinert’s remarkable films in Poetics of Cinema. Some day I hope to write more about Paul Leni’s war drama Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, 1917) and Joe May’s energetic and entertaining serial Die Herrin der Welt (Mistress of the World, 1919).

Homunculus and his friends

Sappho (1921).

DB here:

Of the big-ass explosion movies, only two items in this summer’s spate of them have intrigued me. I liked Mad Max: Fury Road well enough, but not as much as MM2 and 3. I look forward to Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, in a series for which I have much affection. As for the arthouse releases, the ones I’ve already seen are A Pigeon Sat… (good but not as sardonically bizarre as earlier Andersson, methinks) and About Elly. That one is a masterpiece.

I have stronger reasons than indifference for missing so much, and for tardy blogging besides. I’ve been on my annual trip to Belgium for research and lecturing in the Summer Film College. As a result, your recent movie experiences and mine have been divergent, perhaps even insurgent.

Apart from two screenings in the Brussels Cinematek’s Hou series (their restoration of Green, Green Grass of Home, gorgeous vintage print of City of Sadness), I spent the last four weeks watching 35mm prints of movies by Godard, movies starring Burt Lancaster, and assorted silent films from the 1910s and 1920s. I also re-met one of the most charming directors I know of, and in general had a hell of a time.

Today’s entry focuses on my archive work. Next up, a report on the Summer Film College.

Conrad’s many moods, mostly unhappy

Landstrasse und Grosstadt.

The archive stuff was recherché. I’ve been trying to see as many 1910s and early 1920s features as I could, but this time around I didn’t catch anything as mind-bending as Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (1911) or Doktor Satansohn (1916) or Fabiola (1919) or I.N.R.I (1920), encountered on earlier visits to the Cinematek. I did get further confirmation that in Germany the “tableau style” exploited so vigorously in Europe and somewhat in America in the 1910s, was pretty much replaced by Hollywood-style editing by 1920. And I got some welcome doses of Conrad Veidt, another favorite in this vicinity.

In Die Liebschaften des Hektor Dalmore (“The Liaisons of Hektor Dalmore,” 1921), Veidt plays a callous playboy who keeps on retainer a man who looks very much like him. It’s a lifestyle choice. When a compromised woman’s father demands that Hektor do the right thing, he sends out his double to marry her. Surprisingly, the double isn’t rendered through trick photography. Richard Oswald, always a fast man with a gimmick, found a pretty good Veidt lookalike, which can’t be easy to do.

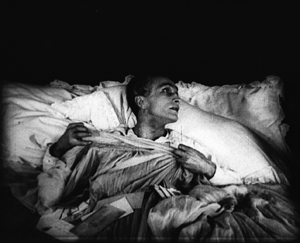

The hero’s Casanova complex carries him from dalliance to dalliance, and as you’d expect in a twins situation, there are confusions between the real and the fake Hektor. Fights and abductions liven things up. The climax is a duel in which the real Hektor, overconfident, learns to his grief that an outraged husband is a better marksman. The scene is handled through brisk shot and reverse-shot, garnished with an over-the-shoulder shot as Hektor aims his pistol. And there are dashes of mildly Expressionist set design (furnished by Hans Dreier). Veidt in a phone booth does the décor proud. But he doesn’t need fancy sets to project a feeling: on his deathbed, his expression and his clutching fingers show a man bereft of erotic illusions.

The other Veidt vehicle lacked doubles but not ambition. Landstrasse und Grosstadt (“Village and City,” 1921) casts him as Raphael, a wandering violinist who teams up with Migal, an organ grinder. They become a popular act in the big city, and as Raphael’s playing improves, Migal becomes his manager. Nadia, a woman who joins them, falls for Raphael and shares his success. But in an accident he suffers a hand wound and his career slumps. Migal sees his chance to move in on Nadia. Perhaps this shot gives you a hint of his designs.

Actually, most of Landstrasse and Grosstadt isn’t as hammy as this. A very nice shot shows Raphael in silhouette approaching a mansion to hear his rival Cerlutti give a salon concert. And of course Conrad gives the blind violinist a delicate, spectral pathos, as shown above.

Artificial man lurks in the shadows, destroys humanity

Sappho.

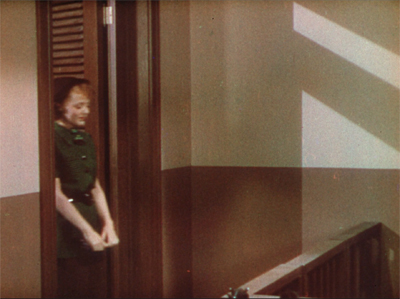

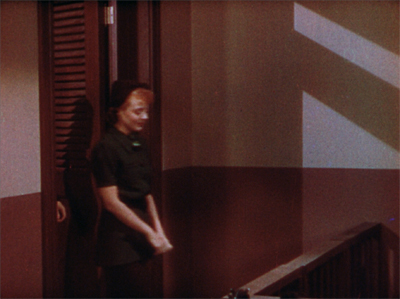

All the films I saw broke down scenes into many close shots, reminding us that Caligari (released 1920) probably wasn’t typical of German staging or cutting of that moment. It now seems to me almost consciously anachronistic, rejecting the reverse angles and precise scene breakdown that were becoming common. In Die Ehe der Fürstin Demidoff (“The Marriage of Fürstin Demidoff,” 1921), when a governess drags a recalcitrant girl back to her bedroom, the action is split up into four shots, all of different scales from close-up to long-shot.

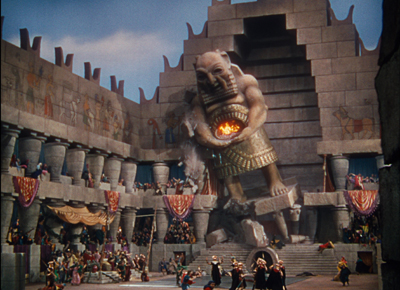

Although I saw a fragmentary print of Sappho (1921), it’s clear that in parts it has the audacious monumentality of a Joe May production. The most staggering shot is that of the Opera surmounting today’s entry, but there’s no shortage of striking images. Above I include a shot of a madman that, thanks to window reflections, suggests his split-up psyche.

Sappho also doesn’t shirk editing effects either. During a frantic automobile ride, there are glimpses of hands on a steering wheel, a foot on brakes, panicked passengers, and POV shots through the windshield. Forty-nine shots rush by in a flurry, anticipating similar sequences in French Impressionist films like L’Inhumaine (1924). Feuillade was experimenting with rapid cutting of action at about the same time.

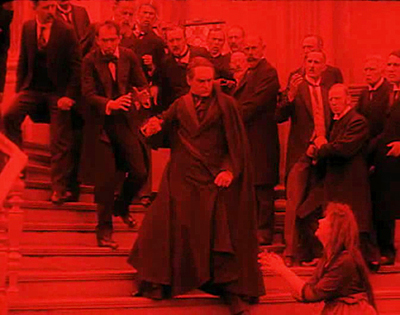

The most impressive, and nutty, film in this batch came from Homunculus, the largely lost German serial released through 1916 and into early 1917. The script was written by one of the blog’s favorite peculiar directors, Robert Reinert. The plot involves an artifical man created in the lab, à la Frankenstein’s monster. He’s a superman, in both strength and ambitions. The only surviving episode of the serial is Die Rache des Homunculus (“The Revenge of Homunculus,” 1916). (But see the codicil.) In this installment, posing as Professor Ortmann, Homunculus decides to drive humanity to destroy itself. He assumes a disguise to rouse the rabble, even inducing them to turn against himself in his Ortmann guise.

As in Expressionist drama, this overachiever is pitted against a crowd that, in the end, pursues him maniacally.

Director Otto Rippert gives us splendid mass effects in a quarry and along a beach, but there are also deep tableau images and sustained chiaroscuro, particularly in a showing the heroine Margot shrinking from Homunculus as he locks his rival in a dungeon.

Fans of Metropolis will notice that Rippert anticipates Lang’s unison choreography of crowds, as well suggesting that mob frenzy can create a sort of ecstasy in the woman who’s swept along.

In her book The Haunted Screen Lotte Eisner traces the films’ mass spectacle back to the stage work of Max Reinhardt and other theatre directors of the era. On the basis of this episode alone, Homunculus ranks with Algol and May’s Herrin der Welt as an example of big-scale fantasy in German silent cinema. Who needs Ant-Man when we have Homunculus?

Next time: Burt and Jean-Luc, together again for almost the first time.

Thanks to Nicola Mazzanti, Francis Malfliet, Bruno Mestdagh, and Vico de Vocht for their assistance during my visit to the Cinematek.

Kristin analyzes stylistic conventions of German cinema of this period in her Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available for download here). She’s written on Caligari here and here.

A so-so copy of Sappho is on YouTube.

On Homunculus, Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel, pp. 160-167. Substantial excerpts can be found here.

Munich archivist Stefan Drössler has recovered a mass of Homunculus footage and has assembled a version of the serial, which premiered last year in Bonn. Nitrateville has the story.

The Brussels Cinematek will release its Hou restorations on DVD early next year: Cute Girl, The Boys from Fengkui, and Green, Green Grass of Home. As a reminder, my video lecture on Hou is here.

The still below, taken as the prints were readied for the Summer Film College, points ahead to our next entry–number 701, as it turns out.

Nitrate days and nights

Paolo Cherchi Usai introducing a session of The Nitrate Picture Show.

DB here:

Our entries have been laggardly lately because of various factors: a trip to a family wedding in DC, work on a new edition of Film Art, a stubborn cold, and not least, a bustling trip to Rochester’s George Eastman House for The Nitrate Picture Show. This last event is the topic for today, and hoo boy was it something.

Handle with care, respect, and admiration

Light Is Calling (2004).

For the first fifty years or so of cinema, commercial feature films were shot and shown on nitrate-based film stock. The film emulsion, consisting of silver halide crystals (for black and white) or dyes (for color), was supported by the base, a clear, flexible strip. That strip was made of nitrocellulose.

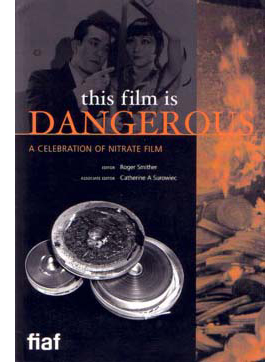

In a talk at the Picture Show, Roger Smither, editor with Catherine Surowiec of the definitive compendium This Film Is Dangerous, reviewed some essential features of nitrate. As most people know, it catches fire easily. Quentin Tarantino built the climax of Inglourious Basterds around a theatre fire deliberately set by touching off heaps of nitrate. Robert Flaherty famously barbecued his initial footage of Nanook of the North by smoking while he worked on editing it. No surprise that nitrocellulose was used in munitions, where it was often called “gun-cotton.”

In a talk at the Picture Show, Roger Smither, editor with Catherine Surowiec of the definitive compendium This Film Is Dangerous, reviewed some essential features of nitrate. As most people know, it catches fire easily. Quentin Tarantino built the climax of Inglourious Basterds around a theatre fire deliberately set by touching off heaps of nitrate. Robert Flaherty famously barbecued his initial footage of Nanook of the North by smoking while he worked on editing it. No surprise that nitrocellulose was used in munitions, where it was often called “gun-cotton.”

Once ignited, nitrate is hard to control. It will burn under water, and it can feed on its own flames. A dramatic 1948 documentary screened at the Picture Show presented almost comically horrifying ways in which a nitrate fire resists extinction. Nitrate also produces highly toxic gases. For such reasons, nitrate projection booths are designed to slam shut tight and let the fire eventually exhaust itself. God help you if nitrate goes up in an open warehouse or theatre space.

It was this volatility that forced most national film industries to convert from nitrate-based stock to acetate, or “safety,” stock. In America, the process began soon after World War II and, among other advantages, allowed exhibitors to lower their fire-insurance costs. Other countries were slower to convert; at the Picture Show, some people mentioned that the Soviet Union was still using nitrate stock in the early 1960s. As for archives and laboratories storing nitrate films, conflagrations were distressingly common. Roger and Catherine’s book list dozens of major nitrate fires from 1896 to 1993.

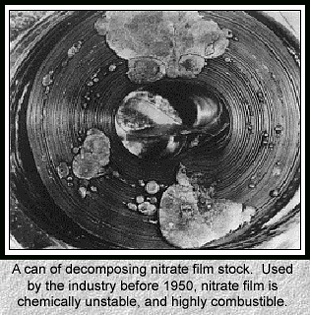

Apart from its tendency to blow up, nitrate is chemically unstable and can decompose. Heat, moisture, and exposure to chemicals can wreck nitrate in a host of ways. It can become infiltrated with a blotchy growth that some find piquant (viz. Bill Morrison’s Light Is Calling, above). The base can flake off from the emulsion. A nitrate print can shrink, warp, blister, or become brittle. The film can start to smell, or turn to brown powder. Some of these problems are present with acetate as well, but combined with the possibility of nitrate combustion, acetate had an advantage.

A string of well-publicized explosions in the 1970s at the Library of Congress, Eastman House, and the Cinémathèque Française resulted in millions of feet of film being lost. National governments became aware of the threat to their film heritage. Archivists seized upon the slogan, “Nitrate won’t wait,” and circulated scary images like the one on the left. Money was given, and thousands of feet of film were transferred to safety stock. In the process, however, a fair amount of nitrate was discarded. In 2000, Roger noted, archivists were surprised to learn that a great deal of nitrate around the world remained in good shape. The late Susan Dalton, our archivist here at Madison for many years, argued that all of today’s films should be transferred to nitrate, the most proven and reliable long-term format.

A string of well-publicized explosions in the 1970s at the Library of Congress, Eastman House, and the Cinémathèque Française resulted in millions of feet of film being lost. National governments became aware of the threat to their film heritage. Archivists seized upon the slogan, “Nitrate won’t wait,” and circulated scary images like the one on the left. Money was given, and thousands of feet of film were transferred to safety stock. In the process, however, a fair amount of nitrate was discarded. In 2000, Roger noted, archivists were surprised to learn that a great deal of nitrate around the world remained in good shape. The late Susan Dalton, our archivist here at Madison for many years, argued that all of today’s films should be transferred to nitrate, the most proven and reliable long-term format.

There was also an argument for keeping nitrate around on artistic grounds. As Roger put it: “It’s pretty.” Everyone I know agrees. In the late 1970s Kristin and I saw at MoMA a double bill of two nitrate prints, Gance’s La Roue and Ford’s How Green Was My Valley. They glistened. Later, attending the Pordenone Giornate del Cinema Muto and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, we saw lots of nitrate prints and were always overwhelmed. The images, especially from very early films, seemed at once sharp in contour and soft in textures.

So nitrate images look great. But why? Some say that nitrate prints have more silver in the emulsion than acetate ones. In This Film Is Dangerous, John Reed suggests that the increased “silver load” yields solidity in shadow areas and vitality in white ones. He also speculates that nitrate-based copies may benefit from projector lenses, screen surfaces, and carbon-arc projection (this last a topic I’ve touched on briefly with respect to Technicolor). If all these factors are in play, the beauty of the copy may be only contingently related to nitrate as such.

Moreover, can we specify the Nitrate Look, in the way we can tell oil paint from water colors? Conducting an informal survey of archivists at the Picture Show, I could find no one who would claim that he or she could confidently spot a nitrate print simply from seeing it projected. Perhaps we are not yet at the stage of connoisseurship of a traditional art historian. Or it may be that foreknowledge that a print is a nitrate one biases us toward ascribing more beauty to the images. To get a precise sense of the Nitrate Look, Reed suggests we’d need an A/B test, running a nitrate print side by side with a fine-grain acetate positive from the same negative.

Richard Koszarski pointed out in conversation that watching a nitrate print we know we’re getting something old–if not an original (it could be a re-release print), at least a copy that audiences did see back in the day. Paolo Cherchi Usai, in introducing the Show, pointed out that the goal was not simply to screen a lot of classic films but to present an experience of cinema from another time. In addition, you have to admire the sheer robustness of these survivors: the prints have been shown a lot and still look lustrous.

To put the emphasis on the “nitrate experience,” nearly all the titles of the films were kept under wraps until we arrived. The goal was not to enhance or deflate the mystique of nitrate, but to call attention to the unique beauties of specific copies and to ask us to reflect on the purposes and consequences of film preservation. To the same end, in a lecture Kevin Brownlow surveyed his efforts to rescue rare footage by Chaplin, Gance, and others.

A panel discussion of archivists considered whether 35mm, in any form, was still viable for public showing. Answer: Most definitely. If a venue meets archival screening conditions, libraries are willing to loan copies. Just don’t count on nitrate ones. Paolo estimates that there are fewer than half a dozen nitrate-secure projection booths functioning in Europe and the US.

No pixels, please, we’re purists

Leave Her to Heaven (1945).

Whatever the cause, the films looked undeniably spectacular. I was least taken with the 1930s Selznick items, A Star Is Born (1937, in a 1946 reissue print) and Nothing Sacred (1937). They have never seemed to me first-rate movies: I think the Cukor Star Is Born is far superior, and Nothing Sacred, after a lively opening, seems to me to run out of comic steam. Not enough characters, maybe; not enough twists, possibly; too much Walter Connolly, I’m sure. Twentieth Century beats it hands down. But of course the prints were very good, and the genial William Wellman, Jr., came by with informative background information keyed to his new biography of his dad. (Lest I seem to be opposed to Wild Bill, let me record my admiration for G. I. Joe, Battleground, The Ox-Bow Incident, and Track of the Cat.)

The Selznick prints suggested progress in 1930s Technicolor. I was struck by the problems of matching brightness and hues from shot to shot, or sometimes right after a cut, as early in A Star Is Born.

By the end of the decade, of course, with Snow White, The Wizard of Oz, and Gone with the Wind, Technicolor had created a more consistent palette.

The 1940s, the great era of Tech, was on rich display in other titles. I had to miss Black Narcissus, but this may have been the British Film Institute copy I’ve seen. I remember the color as being as both gloomy and ripely unrealistic. [Nope! It was the Academy copy, and everybody told me it was gorgeous.]

The copy of Leave Her to Heaven (from UCLA) made Gene Tierney’s ruby lips all but float off the screen at you. Even wilder was a demonically gorgeous print of Samson and Delilah from the Library of Congress. The movie is typically silly DeMille, but it’s fun to watch how a story you already know gets padded out with a fierce lion, bevies of dancing girls, and a somnolent George Sanders, the man who died of boredom.

The spectacle is what the audience was paying for, and the color design gave them their money’s worth. No movie I’ve seen lately galvanizes the spectrum the way this one does. The almost shadowless lighting makes every color pop. I don’t think I’ve ever seen as many shades of pink and purple in a movie, and the pastels admirably set off the burnished beefcake of Victor Mature.

Richard Koszarski, still on a roll, pointed out that Sunset Blvd., the film in which the Gloria Swanson character visits DeMille on the Samson set, features an odd homage. The phone table at the apartment of Artie Green (Jack Webb) boasts a statuette of the god Dagon, whose temple Samson pulls down.

Did Artie pilfer a model? Is it an in-joke like Pike’s Pale? Or a piece of remote cross-promotion? There’s always more to see.

Monochrome as multichrome

The Fallen Idol.

The black-and-white nitrate titles were just as astonishing. Casablanca had a subtle gray scale I had never noticed before; it would be worth comparing this print with the digital copy piped to theatres as part of the recent classics revival series. Can the latter be anything like this? The first Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) is no stranger to this blog; the 1943 print looked crisp and sounded exceptionally good.

Rene Clément’s Les Maudits (1947, “The Damned”) was previously unknown to me. It’s a remarkable wartime thriller, with long, tight tracking shots through a submarine and cramped, noirish deep-space compositions.

Clément employs a flashback narration that stems from the protagonist writing his memoir of the incident. It looks forward to Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest, but in a way it’s a bit more daring, because it mixes the character’s voice-over but with the commentary of an impersonal objective narrator.

Somewhere between color and black-and-white was the delirious fantasy romance Portrait of Jennie. It has its problems, chiefly a subplot showing the painter Eben Adams working on a barroom portrait of Michael Collins, but there is a goofy grandeur to the whole enterprise. The magnificent corps of Eastman projectionists managed to re-create the splashy climax of original 1948 screenings. Not only does the image go green, but it gets bigger. Bosley Crowther reports it an apotheosis of kitsch.

Then, when a green flash of lightning electrifies the screen, which expands to larger proportions, and sound vents around the theatre roar with the ultimate and savage fury of a green-tinted hurricane, the final vulgarization of Mr. Nathan’s little fable is achieved.

The effect is indeed overblown, but I didn’t hear anybody in Rochester complain.

The final title, kept secret until the moment of projection, was The Fallen Idol, one of the great staircase movies in an era of great staircase movies. An exercise in Jamesian restricted viewpoint–What Maisie Knew, for the cinema–it confines us almost wholly to a little boy who worships the family butler but can’t quite fathom the currents of grownup unhappiness and betrayal swirling around him. Carol Reed’s love of low angles and looming foreground planes is kept under precise control, and the moments of suspense, notably the famous swooping circuit of the paper airplane, remain just as strong as ever.

I have to believe that James Card, legendary master of Eastman House, would have approved of the whole shebang. This is his centenary, and along with the Picture Show there was an informative display surveying the career of the man who, with saintly George Pratt at his side, gave Eastman House its unique cachet.

The Nitrate show drew about 300 passholders and as many as 100-150 locals for some shows. It’s planned as the first in a series. Next year’s session is slated for 29 April-1 May. See you there?

Thanks to Paolo Cherchi Usai and Jared Case for their hospitality during my visit. Thanks as well to the Eastman House staff, especially Deborah Stoiber, Jurij Meden, and Ben Tucker, who made the weekend memorable. In all, excellent programming and presentation!

An entertaining account of the preservation movement is Anthony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait: Film Preservation in the United States (McFarland, 1992). It’s there I learned that Kemp Niver once pulled a gun on Raymond Rohauer. Archivists were tough in those days.

The stupendous volume edited by Roger and Catherine, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) is full of information, anecdotes, and whimsy (poems, caricatures). On the history of the technology, the best starting points in this collection seem to me Deac Rossell’s “Exploding Teeth, Unbreakable Sheets and Continuous Casting: Nitrocellulose from Gun-Cotton to Early Cinema” and Leo Enticknap’s “The Film Industry’s Conversion from Nitrate to Safety Film in the Late 1940s: A Discussion of the Reasons and Consequences.” John Reed’s skepticism is recorded in “Nitrate? Bah! Humbug! A Personal View from an Archive Heretic.”

All of the films screened are available on DVD, but I want to signal Les Maudits, on the Cohen label, as a real find. My Star Is Born frames comes from the Kino Blu-ray release, itself drawn from the Eastman House print we saw.

A sunny spring day in Rochester: the perfect time to head into the Dryden Theatre for a movie.

P.S. 13 May 2015: During the fest I hung around with Richard Leskosky, retired prof and Ebertfest buddy, and he’s written a fine column about the event.

P.S. 15 May 2015: Thanks to André Habib for correcting my attribution to the Bill Morrison film; I’d originally identified it as Decasia. And thanks to Mike Pogorzelski of the Academy for correcting me on the source of Black Narcissus. I sure wish I hadn’t been too logy to stay for it.

They had time for everything then

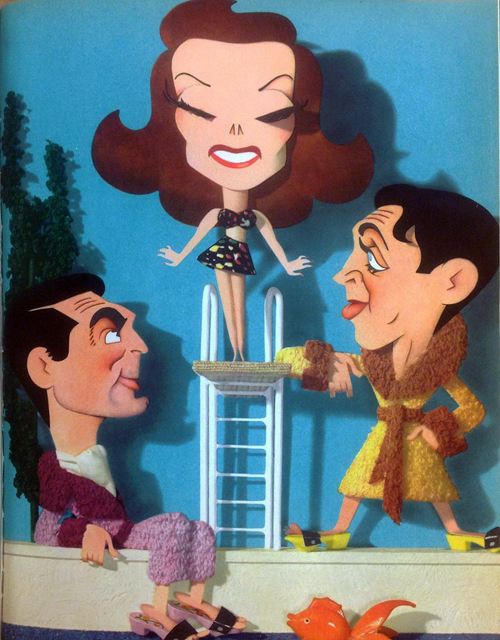

Advertisement for Woman of the Year. From Hollywood Reporter (23 April 1942), 5.

During the 1940s, MGM promoted some of its top pictures with unique illustrations. The artist would make cutout caricatures of the stars, dress them in fabrics, and then prepare little shallow-relief scenes, with props made of wood, carpets, and other stuff. Above, the microphones seem made of metal and plastic, and Tracy’s coat has real buttons attached. Below, the men’s slippers are three-dimensional, as is the toy goldfish and, I suppose, the diving board.

The little tableau would then be photographed, in luscious color. Some were printed with elaborately embossed borders.

I say “the artist” because he or she goes unidentified on these advertisements. The only signature is an enigmatic “K”; in the image above, it’s on the tiny baseball at the bottom. If anyone knows who K is, or can supply further background, please correspond.

Interestingly, these charming images continued to be published from time to time through the early years of the war. I’m afraid my reproductions don’t do them justice, but you get the idea.

Damn, but film research is fun.

P.S. 24 April 2015: Ask and ye shall receive. Alert reader Mark Schoenecker writes:

I’m sure you’ve already received correspondence naming the identity of the mysterious MGM illustrator responsible for those distinctive 3D paper sculpture pieces from the 30s and 40s — but in case you haven’t, his name is Jacques Kapralik. I’m an illustrator myself and have always been vaguely aware of the existence of these cut-out posters. What I didn’t know was that one man was behind them. I’d assumed it was a style prevalent during that era. It wasn’t until I found myself drawing my own series of caricatures in a similar vein that I decided to track down the originals online to see if I was remembering them accurately.

Here is a link to the most interesting article I came across: https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/movie-poster-of-the-week-the-jacques-kapralik-archive

I should’ve known that the indispensable MUBI would have something on this. It’s a fine piece of work by Adrian Curry, showing that Kapralik did movie title sequences as well. Be sure to check the links in that entry and the comments. The University of Wyoming holds Kapralik’s collection, and an online finding aid gives access to many of his beauties.

Many thanks to Mark for clueing me to this. You should immediately check Mark’s own lively, dry, and sometimes scathing, caricatures here. Who else thinks of drawing Dorothy Kilgallen and Korla Pandit?

Advertisement for the The Philadelphia Story. From The Hollywood Reporter (31 December 1940), 7.