Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Breaking AMBERSONS news: Did you say Buried?

DB here, again and still:

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film.

That’s me, just two days ago. I suggested that the mystery poster tucked into the corner of one shot in The Magnificent Ambersons is the Pathé release of 1912, The Cow-Boy Girls. Readers with long memories and no life of their own will recall that this question has bugged me since my earlier post in May. Last week my colleague Eric Hoyt suggested what the title might be, and some rummaging in various sources, particularly the invaluable Lantern database, seemed to confirm it.

To recap: Here are two blow-ups from a 35mm print, showing the two angles from which Welles’ camera captures the poster. The text is clearer in the half-size one, but the more distant one yields a fuller view. The poster seems to depict a man thrashing an American Indian, with a young woman, arm outstretched, in the rear. Note also the shield-like triangular shape underneath the title on the first image.

Last night came word from two more vigilant correspondents, each with new evidence–again, unearthed by the light of Lantern.

My first correspondent was Luke McKernan, early film specialist and master builder of the vastly informative website The Bioscope. Luke has stopped posting there, but he continues to write keenly on cinema at lukemckernan.com. His message to me runs as follows:

Dear David,

I have struggled and struggled with this one til I’m at the point of worrying about my eyesight. I don’t think it can be The Cowboy Girls, but searching for the keyword Cowgirl might be productive. I found this in the Lantern site, searching for ‘cowgirl’ and 1912:

http://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/movingpicturenew05unse_0122

It’s not the right film, but the still is quite close to that in the Ambersons poster, which at least gives encouragement.

Luke

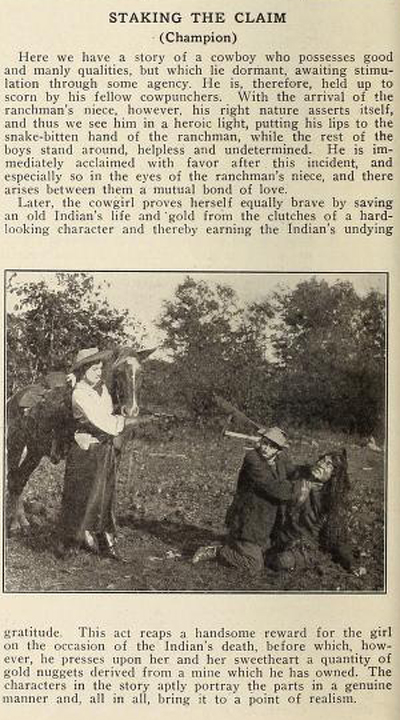

The entry Luke refers to is this one, from The Moving Picture News of 1912.

The picture shows the situation we find in the Ambersons poster. But as Luke says, our poster’s title clearly is not Staking the Claim. More research, as we academics say, is needed.

Just a few hours later came this from another colleague here at Madison, Ph.D. candidate Eric Dienstfrey.

Hi David,

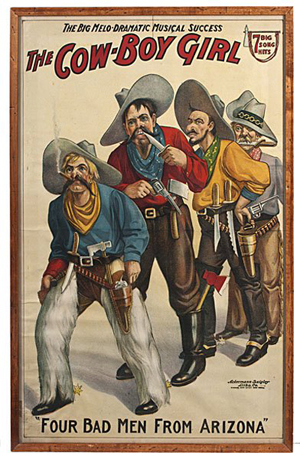

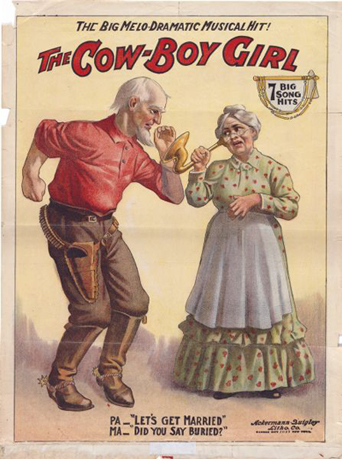

Reading your post on Ambersons now, I remember coming across the title The Cow-Boy Girl while researching stage musicals that were contemporary to Gottschalk’s The Tik-Tok Man From Oz and The Patchwork Girl of Oz. You are absolutely correct, the poster does say “The Cow-Boy Girl” but it was for a theatrical musical, not a film… at least I don’t think so. (But many films were probably called Cowboy Girl too.) I’ve attached two different posters from the musical that I found online. The triangle shield is not the Pathé rooster after all!

I hope you find this interesting/useful… or better yet, I hope this brings you a little closure.

Cheers,

Eric

I had mentioned on Saturday that there was a stage show called The Cow-Boy Girl, and I wondered whether the poster was promoting not a film but the theatre piece. In the end, I went with a film title. But Eric D’s visual evidence of the title font and the triangular motif (not a shield but a swag curtain, I think) strongly suggests that we’re dealing with a play. It would be characteristic of a theatre in 1912 to include vaudeville, stage shows, and other live entertainment alongside movies.

The Cow Boy Girl (no hyphen), a thirty-minute playlet including songs, was reviewed, unfavorably, by Variety (29 October 1910). The review doesn’t mention a scene like that depicted on the poster.

Other sources lists touring shows of The Cow-Boy Girl (with and without hyphen) from 1910 onward, so it might well have been playing the Bijou in the Ambersons’ town in 1912. Actually, Eric D. has found that it did play another Bijou. The Billboard of 18 February 1911 lists the following:

How can you argue with something that played the home of thrillers?

Are we there yet? Until we find a copy of the poster itself, I’m inclined to think so. But as Luke’s discovery indicates, we’re dealing with a period in which imagery, titles, and situations were copied and circulated in great profusion. In 1912 plenty of cowgirls and cowboys and cowboy girls and cow-boy girls were swarming over American entertainment. More or less like superheroes today.

No research project is finished, only abandoned. Thanks to the Fussbudget Team for playing!

The Fussbudget Report: An AMBERSONS solution

DB here:

Some readers may recall my post on The Magnificent Ambersons back in May. I argued that Welles built a sense of the irretrievable past into many aspects of the film’s narration. He used the voice-over commentary to evoke times gone by, but also ellipsis, offscreen action, constant recitation of memories, and other strategies. In addition, there were moments of cinephile nostalgia, including the iris shot at the end of the snow scene and the concluding credits of the actors slowly turning to face the audience, as in the manner of films of the 1910s.

Then there were the movie posters. George and Lucy are walking through the town. He’s about to leave for Europe, and she feigns a polite lack of concern. They pass the Bijou movie house, which flaunts several posters. I managed to identify all but one, the one tucked in the lower right of the frame above. I just couldn’t properly read the title, even on a good 35mm print.

Blown up from 35, the clearest view we get of it looks like this.

I thought it might be The Coin-Box Girl, but no such film title existed. Some readers– Jacopo Pes, Ivo Blom, and Paolo Cherchi Usai (thanks to all)–proposed some possibilities. Alas, none of their suggestions seemed to fit. Even running through the Library of Congress copyright listings for films didn’t yield a plausible candidate.

Over a lunch with colleague Eric Hoyt last week (Eric is one of the geniuses behind Lantern), we talked about this. Eric had access to a bigger list of titles than that of the LoC, and he suggested that the first words might be cow-boy. Checking his list, we find that there was indeed a May 1912 Pathé release called The Cowboy Girls. It’s also listed in Lauritzen and Lundquist’s American Film-Index 1908-1915 under that name. It might well have been postered as The Cow-Boy Girls. (We now assume that the squiggly line after “Cow” is a hyphen. It might be just a really curly w.) An April 1913 ad from the Carbondale Daily Free Press lists a film called The Cow Boy Girls, so if it’s the same movie, there was some freedom of punctuation around it.

I left the second ad underneath so you can appreciate having electricity.

It would be very nice to check a poster of the film, but I haven’t found one. Here, though, is a synopsis from Moving Picture World of 1912. (Again, thanks to Lantern.)

This doesn’t quite match the image on the poster, which shows a man apparently about to strike a Native American kneeling before him. But in the background, more visible in the half-framed poster, there seems to be a young woman coming out of a cabin protesting, and perhaps brandishing a pistol. (Open Carry applies here.)

There are other anomalies. If this is indeed The Cowboy Girls from Pathé, does the triangular shield logo in the northwest corner boast a rooster? Some Pathé titles did, as for this 1908 French release (one of the most important films ever made). On the four shields, the rooster (also to be seen as decor in Pathé interiors) is joined by the eternal symbol of the theatre, the comic and tragic masks.

And if The Cowboy Girls is a Pathé title, did the Carbondale ad list it as “Essany” (Essanay) by mistake? Or is that a different cowgirls movie? It may be relevant that there was a vaudeville play called The Cow Boy Girl, which was touring at the same period. Filmmakers may have tried to cash in on that. Or maybe the Ambersons Bijou was presenting that stage show rather than a film?

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film. The clincher for me is the Cowboy Girls’ date: 1912. Except for the fake lobby card promoting a nonexistent Jack Holt movie, all the discernible film posters in the Ambersons scene are from 1912 releases.

This obsessive synchronization is surely the work of a film nerd, either Welles or a staff member. Geek calls out to geek, from 1912 to 1942 to 2014. See? I’m not the only fussbudget here.

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book

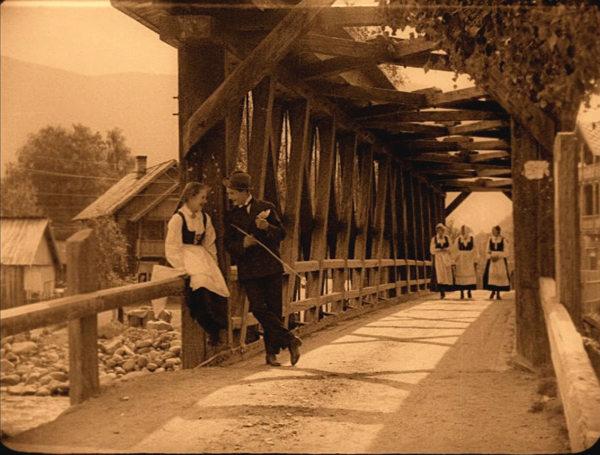

Gipsy Anne (1920).

Kristin here:

A stack of new DVDs/BDs and books has been gradually building up on the floor in a corner of my study. I’ve been meaning to blog about them, but first I had to catch up with viewing and reading. Or did I? With this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato starting next week, I suddenly realized that the DVDs at the bottom of the pile were ones I bought there last year! Clearly, I would never catch up.

So this entry aims to notify you of releases, many obscure, that you may so far have missed. Mostly the DVDs and BDs come from the dedicated archives and independent home-video companies that release historical rarities and restorations.

Early Scandinavian films

I don’t think I had ever seen a Norwegian silent film, apart from the one Carl Dreyer made there, Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1925). Though produced between Master of the House and the wonderful La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, The Bride of Glomdal is unquestionably one of Dreyer’s lesser works.

In the sales room at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, one stand was selling four new releases of Norwegian and Swedish silent and early sound films. All were issued by the Norsk FilmInstitutt.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

This is the only one of these Norwegian films that I have so far watched, and it’s a remarkable one. Clearly Breistein and his cinematographer Gunnar Nilsen-Vig were influenced by the great Swedish films of Sjöström and Stiller, and though Gipsy Ann is not up to the best work of those two, it shares the same feeling for landscape for for allowing a melodramatic situation to develop slowly and in unexpected ways.

It tells the story of a foundling child, Anne taken in by a widow who owns a large farm and who raises the girl alongside her son, Haldor. Haldor is a timid boy, constantly led astray by the adventurous Anne. Once they grow up, the two fall in love, but Haldor’s mother pushes her son into an engagement with a young woman from a well-to-do family. In the meantime, Jon, a humble tenant farmer working for the widow, falls in love with Anne, who snubs him.

Gipsy Anne has none of the clumsiness in lighting and staging that one so often sees in European films of the period around 1920. The cinematography is beautiful, as the frame at the top shows. Breistein has mastered shot/reverse shot and other aspects of analytical editing. The lighting is impressive, with some interiors using a strong backlight through windows and a soft fill that gives a sense of realism (left).

The film also sets up neat visual parallels. In a scene in Anne’s childhood (below left), she hides by an old farm building and curiously spies on some local lovers. Much later, she lurks heartbroken by Haldor’s lavish new house as he shows it to his fiancée:

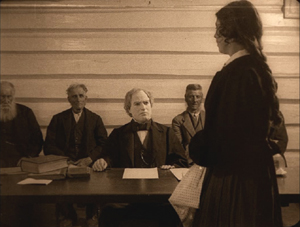

There are even some planimetric shots that yield dramatic compositions, one when Jon comforts the young Anne when she learns that she was adopted, and another, much later, when Anne is in court testifying about the fire that burned down Haldor’s new house:

Again there is a parallel, since Anne is hiding her own guilt in starting the fire, and Jon is about to falsely confess to the crime to protect her. (There’s also a hint at influence from Dreyer in that courtroom shot.)

Of the four releases, Fante-Anne is the only one put out in a Blu-ray version, packaged along with a DVD and an informative booklet in Norwegian and English. The print, with toning and a pleasantly rustic-sounding score, has English subtitles. Oddly enough, the Norsk Filminstitutt does not have an online shop. The film is available from at least two Norwegian online dealers in Scandinavian videos, Nordicdvd and Dvdhuset. It can also be ordered from an American source, Blu-ray.com.

Markens Grøde (The Growth of the Soil) was made only a year later, in 1921; it was directed by Gunnar Sommerfeldt and is another rural melodrama, adapted from a Nobel Prize-winning novel of the same title. This release is 89 minutes long and includes subtitles in English, French, Spanish, German, and Russian. It, too, can be ordered from Nordicdvd and DVDhuset.

The third release is an epic film, Brudeferden i Hardanger (The Bridal Party in Hardanger, 1926). Its two parts run 104 and 74 minutes; it was also directed by Rasmus Breistein, with cinematography by Gunnar Nilsen-Vig. DVDhuset carries it, but not Nordicdvd. It is, however, available from Amazon.uk. It has English subtitles.

Finally there is “Bjørnson på film,” a compilation of three early films based on the pastoral writings of Nobel Prize-winning author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and was issued in 2010, the centenary year of the author’s death. Two of these are Swedish productions: Synnøve Solbakken (1919, director John W. Brunius) and Et Farlig Frieri (A Dangerous Proposal, 1919, director Rune Carlsten). Lars Hansen stars in both, and Karin Molander co-stars in Synnøve Solbakken. The third is an early Norwegian talkie, En Glad Gutt (A Happy Boy, 1932, director John W. Brunius).

After considerable searching, I can find no online source for this 2-DVD set. Perhaps it will become available. Otherwise you’ll have to come to Il Cinema Ritrovato and see if it’s on sale again. If not, at least you will have a great time!

All these releases are PAL, though Fante-Anne is also Blu-ray region B; they would all need to be played on a multi-standard machine.

(Mostly) American treasures

The well-known and invaluable “Treasures” series from the National Film Preservation Foundation has become somewhat difficult to keep track of. It started with “Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films.” That was followed by “More Treasures from American Film Archives: 1894-1931.” After that volume numbers appeared, and the references to archives were dropped in favor of thematic collections: “Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film 1900-1934” and “American Treasures IV: Avant Garde 1947-1986.” Then Roman numerals disappeared with “Treasures 5: The West 1898-1938.”(The ones linked are still in print.)

Now we have an unnumbered entry, but it’s still part of the series: “Lost & Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive.” Most readers will recall that in 2010 it was announced that about 75 films had been found in the New Zealand Film Archive. News coverage mostly centered on John Ford’s 1927 feature Upstream, which had up to that point been lost. That film forms the central attraction for this new release.

It also includes, however, an incomplete print of a distinctly non-American film, The White Shadow (1924). It was directed by Graham Cutts, but it is mainly of interest now as a film on which the young Alfred Hitchcock worked in several capacities. He wrote the script, based on a novel, and was assistant director, editor, and art director. Despite the enthusiastic tone of the program notes in the booklet accompanying this set, there is little detectable of the later Hitch. The story is ludicrously far-fetched, depending on the old good twin/bad twin contrast, with Betty Compson in both roles (above). At various points the twins pretend to be each other, much to the confusion of the bad twin’s fiancé, played by Clive Brook. The convoluted plot becomes even more so when a series of titles tries to convey the action of the missing final three reels.

The film has its moments. Cutts, who was a decent if not outstanding director, manages some lovely compositions, as with the backlighting in the night interior below left. As with many of Hitchcock’s sets for the film, this one is pretty standard-issue. He obviously had some fun with the set for the tavern called The Cat Who Laughs. It looks a bit jumbled, but it’s actually full of little areas that Cutts uses effectively for picking out pieces of action amid the chaos:

So the Treasures series moves on, as does the Foundation. Not all of the discovered prints made it onto the DVD set. Several more have been preserved since and generously made available for free online viewing at the Foundation’s website; more will be added as the restorations are completed.

Blu-ray USA

American classics continue to make their way onto BD.

Flicker Alley has teamed with the Blackhawk Films Collection to release The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923, director Wallace Worsley). No original 35mm negative or print is known to survive, so this release was mastered from a 16mm tinted copy struck at some point from the original negative. Some restrained digital restoration was done to clean it up a bit. The extras include an essay and audio commentary by Michael F. Blake and a 1915 film, Alas and Alack, with Chaney in his pre-movie star days playing a hunchback.

The film is available at Flicker Alley’s website, where you can also pre-order their three upcoming releases: a set of all Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies (1916-17); the first volume of The Mack Sennett Collection, including 50 films; and We’re in the Movies, which collects some early local films made by itinerant moviemakers, as well as Steve Schaller’s 1983 documentary, When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, about the first film made in Wisconsin. There’s also a documentary about a small local theater in Los Angeles that showed silent films in the sound age.

D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation will celebrate its centennial next year, and now it’s also out on Blu-ray, from both Kino Classics in the USA and Eureka! in the UK. Both have the same new restoration from 35mm elements accompanied by the same score. The extras also appear to be identical–most notably seven Biograph shorts by Griffith about the Civil War. The main difference is that Kino throws in David Shepard’s 1993 restoration, with different musical accompaniment and a 24-minute documentary on the making of the film. Again, the Eureka! version is BD region B.

Last month Eureka! also released a BD of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951, BD region B) in their “Masters of Cinema” program. The release also contains a DVD version. You can check it out, along with other recent releases and upcoming ones here.

Edition-Filmmuseum

This German series works with an impressive array of archives, mostly German but also Swiss and Luxembourgian. The titles that result include modern films (Straub and Huillet figure in their catalogue, as does Werner Schroeter), television, experimental cinema (they’ve done several James Benning films), documentaries, and older films. (No Blu-ray as of now. Perhaps too expensive or perhaps just the sort of restraint that dictates the white backgrounds on their covers.)

Recently Edition-Filmmuseum released a set with two films by Gerhard Lamprecht, a little-known and but in the 1920s an important director of socially conscience films set among the working class. The two-disc release includes Menschen untereinander (1926) and Unter der Laterne (1928), each with two musical tracks to choose from. The German intertitles are subtitled in English and French, and the enclosed booklet is likewise trilingual. Like all the DVDs from this company, there is no region coding.

Similarly, another new release is devoted to the early films of Michail Kalatozov, a Georgian director better known for his Soviet films of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., The Cranes Are Flying and I Am Cuba). One of the films here is Salt for Svanetia (1930), one of those vaguely familiar but rare titles from the history books on Soviet montage cinema. The other is Nail in the Boot (1932).

Salt for Svanetia is indeed a classic that anyone interested in silent cinema and the Soviet Montage movement should see. Set in an extremely isolated, primitive area of the Caucasus, Svanetia obviously needs a dose of Soviet modernizing. The peasants can barely subsist, and a lack of salt makes their cows and goats unable to produce milk. It’s basically an attempt to combine an ethnographic documentary with large doses of Montage-style rapid editing, canted cameras, heroic framings of people against the sky. At one point a man cutting another’s hair is framed against one of the local feudal era towers in a low angle that makes it look like something out of Alexander Nevsky (above). The film is a fascinating peep into a little-known culture.

Kalatozov stages some sketchy scenes using the locals: an avalanche which kills some men, a resulting funeral, a woman giving birth alone in the countryside. There’s no over-arching plot, though, and the director wisely sticks with showing off local customs. Naturally at the end the Soviets are building a long road to reach the area, and there’s a promise of good things to come.

Nail in the Boot is impressive for about two-thirds of its length. It stages some large battle scenes between what I take to by the Red and White Armies during the Civil War. The Whites are attacking an armored train, and a lot of explosions result. The soldiers aboard the train fire machine-guns, and Kalatozov conveys the sound by alternating single-frame shots of the muzzle of the gun with single-frame shots of the man firing it. Sound familiar? It happens two or three more times in the course of this film. Both of these films are definitely part of the Montage movement, but the director has come along so late in it that he seems to feel all the good ideas have been used, and they’re worth using again. So we get another quotation from October in a canted shot of a cannon’s wheel, and Kalatozov even steals the idea of our hero looking and feeling very small and his prosecutor becoming a looming giant, as in Kozintsev and Trauberg’s The Overcoat:

We are some time into the film before we meet the hero, and I was thinking that this might be one of those Montage films with no single central figure. But well into it, the ammunition on the train is running out, and a messenger is sent to run and get help. Much of the film simply shows him running along, becoming increasingly lame as a bullet in his boot digs into his foot. Ultimately he does not reach his goal, though he tries hard. Once he is put on trial for treason, he blames the shoddy workmanship of the cobblers who made his boot badly. This seems a strange anti-climax after the exciting battle scenes earlier on, but the film actually turns out to be about Soviet workers paying attention to what they’re doing and not putting out a bad product. All the workers looking on at the trial look shame-faced at the hero’s accusation, suggesting that if a hundred percent of the workers are doing a bad job, there’s not much hope of rectifying the situation.

Both films are fascinating because they come so late in the Montage movement, which lasted from 1925 to 1933, and they are particularly valuable because it’s harder to see the films from this late period than those from the 1920s.

Both films have optional English subtitles.

By the way, Edition Filmmuseum also sells Flicker Alley films, and those in Europe and elsewhere might find them easier to order on its website.

You’re gonna need a bigger shelf

There are three notable new releases of French films. Before I get to the two epic, brick-like sets, let me mention the new Eureka! Blu-ray of Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont du Nord (1981) in the “Masters of Cinema” series. Admirably, the film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio. The supplements consist mainly of a thick booklet with some new essays, an interview with Rivette, and so on. You can read more about the booklet’s contents and buy the film here. Note that it is coded BD region B.

Now to the bricks.

At long last the French Impressionist director Jean Epstein is well represented on DVD. Although a few of his most famous films have appeared on video from time to time, these eight discs are a cornucopia of his work (plus a 68-minute documentary on his work by James June Schneider). They come from what are probably the best possible prints, since the set is issued by La Cinémathèque Française. Marie Epstein, who had made films herself in the late 1920s and 1930s, worked at the Cinémathèque for decades and helped preserve her brother’s work. A major retrospective of Epstein’s work ran at the Cinémathèque in April and May; the restorations in preparation for the series made possible to this DVD set. (This page links to further resources on Epstein.)

Epstein started out working for some of the large French film companies, though he mixed somewhat experimental films with more standard ones. His second surviving feature film, Cœur fidèle, is one of his most famous, and perhaps his masterpiece. A beautiful print of it is already available on a Eureka! DBD/BD combo (BD region B). There’s also a French DVD. I wrote a little about it when it made our top-ten films of 1923 list.

The big outer box of the set comes with three inner fold-out disc holders that reflect the phases of his career. The first is “Jean Epstein chez Albatros.” In 1924 Epstein joined the Russian-emigré company Albatros. Three of the four films he directed there are grouped together: Le Lion des Mogols (1924), starring Ivan Mosjoukine and Nathalie Lissenko; Le double amour (1925); and Les aventures de Robert Macaire (1925). The big gap here, and indeed in the entire set, is the absence of the fourth, L’Affiche (1924), which I think is one of his best. It does survive, so I hope it will eventually appear on disc. Apart from L’Affiche, these are all big-budget productions, and Robert Macaire is a serial running 200 minutes. This set has no overlap with the Albatros set from Flicker Alley that I wrote about last year and indeed is an excellent supplement to it.

Beginning in 1926, having been successful with his big Albatros films, Epstein produced his own work under the name “Les Film Jean Epstein.” Again, there were four films, the surviving three of which are on the discs in the second folder, “Jean Epstein: Première Vague”: Mauprat (1926), La glace à trois faces (1927), and La chute de la maison Usher (1928). (The lost film is Au pays de George Sand, 1926.) La chute de la maison Usher was for a long time the only Epstein film available on 16mm prints, which didn’t really do justice to its eerie German Expressionist-influenced sets.

Gradually, however, the reputation of La glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”) has grown, and it is another highlight of Epstein’s career. It introduced a trope of modernism into the cinema, the notion of using point of view to create ambiguity. The story shows scenes concerning one man as seen through the eyes of his three lovers–each, of course, making him seem a very different person.

The other films deserve discovery as well. Le Lion des Mogols has a clever story (written by Mosjoukine) which starts out in a fictional Tibetan city where the hero, a nobleman (Mosjoukine) incurs the sultan’s wrath and flees. A cut to a ship suddenly reveals that we are in a modern world, and the film becomes a fish-out-of-water story as the hero blunders onto the set of a movie location shoot on deck (above). Intrigued, the female star of the film helps him adjust and brings him in as a leading actor. Thus our hero jumps from one genre, the fantasy Far-Eastern melodrama (familiar from various German films of the time, including the Chinese sequence from Lang’s Der müde Tod) to a modern romance. The film has the advantage of scenes in and around Albatros’s own studio:

Les Film Jean Epstein produced some major work, but it didn’t make money, and in 1928 Epstein changed course, He made 28 more films, up until his death in 1953, most of which are virtually unknown. The exceptions are some films modest, lyrical films he shot in Breton. Seven of these are presented as “Jean Epstein: Poèmes Bretons”: Finis Terrae (1928, Epstein’s last silent film), Mor’vran (1930), Les Berceaux (1931) L’Or des mers (1933), Chanson d’Ar-mor (1935), Le tempestaire (1947), and Les feux de la mer (1948). These range from 6 minutes to 82 minutes long. Most have simple plots and involve the sea.

The set has been put together so that the supplements for each film are on the end of its disc, not lumped together on a separate disc. There is also a 158-page book, not booklet, with program notes and many images: posters, designs, publicity stills, and frames. (It also has the smallest page numbers I have ever seen.) I can find no indication that the set is region-coded, but the Amazon.fr page says it’s PAL region 2. (I cannot find any reference to the set on the Cinémathèque’s own site, so I can’t confirm either way.) It does have optional English subtitles.

Since the beginning of film history, France has produced one of the world’s great national cinemas, and Jacques Tati is one of its greatest directors. On Facebook, Ingrid Hoeben, one of Tati’s devoted fans, runs a page called “I’d like to be part of the Monsieur Hulot universe, if only as a cardboard cut-out”, and I think she speaks for many of us. (She also runs a FB page on PlayTime–as she spells it. Many writers use Playtime, and I prefer Play Time.)

For those who love Tati, there is finally a new set of his complete works, restored and available in separate DVD and Blu-ray sets. The imposing big black box contains seven discs, each in its own cardboard fold-over holder, one for each of the features and one for the shorts. There are extras on each disc. The small book included with the set has a brief bio of Tati, information on the restoration of the films, and program notes.

There are various versions of some Tati films. The Mon Oncle disc includes both the French and English-dubbed versions. The Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot disc has the 1953 version and the 1978 restoration. Jour de fête, which Tati tried to make in color, has three versions: the 1949 release print, the 1964 one with selective color added, and the 1994 restoration of the color version Tati had had to abandon.

The print of Play Time, though visually beautiful, is altered by some tampering by the restorers. It originally contained passages of music over a dark screen at beginning and end. I described these moments in my essay, “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception” (published in 1988 in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis). Of the beginning I wrote:

The film begins with pre-credits music involving percussion; at a seemingly arbitrary point in this music, the bright credits shot of clouds fades suddenly in from the darkness. Already we encounter the sound track as a separate level from the image track–as something to which we should pay cloe attention in its own right. (Unfortunately, most of this music seems to have been edited out of the re-release print.) (p. 253)

(The darkness and music actually last about 10 seconds before the cloud shot.)

And the ending, which in the original has several minutes of music played over a black screen:

Play Time structures even our transference, at the end, of aesthetic perception to everyday existence, by continuing its theme music for several minutes after the images stop–so long that we are forced to get up and move about to this music. The film’s sound track becomes an accompaniment for our own actions, inviting us to perceive our surroundings as we have perceived the film. (p. 261)

(The actual timing is about one minute, though it seems longer when you’re sitting in a darkened theater and are used to leaving immediately at film’s end.)

This new disc includes the dark footage at the end and the music, but the credits for the restoration and video are superimposed throughout–quite a different experience than music accompanying darkness. The music over darkness is shortened at the beginning to about 3 seconds, with the logo of Les Films de Mon Oncle’s logo and a dedication to Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s daughter.

All these superimposed credits alters Tati’s intentions considerably. He clearly meant for that concluding music to make us almost actors in his film and to carry over its defamiliarization of the fictional world into the real world. Without it, this cannot be considered the definitive version of Play Time. It may seem a small matter, but the original decision was completely reflected Tati’s distinctive style.

Fortunately the Criterion collection’s version retains the music over black at the end, as well as a different set of supplements. Completists will need to have both.

For many, Tati’s last feature, Parade, will be new. It’s not a M. Hulot film or even really a fiction film. It was made in Sweden and consists of a variety performance by musicians, singers, a magician, and so on, all MCed by Tati in propria persona. Between other acts, Tati performs some of his most famous pantomime bits, including a remarkable scene where, as a tennis player, he mimes part of the action as if caught by a slow-motion news camera. Tati also devised some little scenes to take place among the audience, which contains some of the same sort of cardboard cut-outs that first appeared in Play Time:

Parade was shot on video during live performances, but the acts were also staged in a studio in 35mm (see bottom). That’s the source of the inconsistent visual style, though it’s less apparent on video than when projected in 35mm on a large screen.

It’s a strange but enjoyable and even complex film, if one goes into it without expecting it to be like Tati’s others.

Very few will have seen all of Tati’s shorts. These fall into three periods.

Three of them are from the mid-1930s, brief comedies ranging from 16 to 24 minutes: On demande une brute, Gai Dimanche, and Soigne ton gauche. Tati was a young music-hall performer at the time, specializing in sports pantomimes.

Second, there is L’École des facteurs (1946), a 16-minute version of of the same story that he expanded into Jour de fête a few years later. L’École des facteurs was his directorial debut, the earlier shorts having been directed by others.

And third, Tati made some shorts late in his career: Cours du soir (directed by Nicolas Ribowski), Degustation maison, and Forza Bastia (the latter two directed by Tati’s daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, who used the original family name).

The set has optional English subtitles and is BD Region B.

On early Soviet cinema and much more

The title of Natascha Drubek’s new book, Russisches Licht: Von der Ikone zum frühen Sowjetischen Kino might seem to imply a narrow field of study. Actually, though, it ranges far, examining the introduction of electric lighting into Russia and examining what a wide range of Russian commentators wrote about light at the time. This includes, of course, the cinema, an art form both composed of light and using light during the filming.

The introductory section covers theoretical approaches to cinema, including the work of the Russian Formalists. Drubek goes on to consider factors in the early history of media in Russian and Soviet cinema, including writings on theaters and film censorship.

She then goes back to the roots of thought on light and media further back in Russian history, dealing with icons and the church, as well as the influence of icons on the Russian avant-garde of the pre-Revolutionary period. Finally she deals with cinema and in particular with the films of Evgenii Bauer.

I cannot claim to have read the book, for with my shaky knowledge of German it would be slow going. But it is an impressive achievement, and anyone interested in Russian/Soviet cinema and especially Bauer should have it. It is available online directly from the publisher.

Tati’s classic fishing routine in Parade.

Caught in the acts

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005).

DB here:

If you’re interested in how films tell stories, I think that you’re interested in several dimensions of narrative. Those include the story world (characters, settings, action), narration (how story information is parceled out as the film unrolls), and plot structure (the arrangement of parts).

Plot structure matters because a movie’s parts, like parts of a song or a symphony, help shape our experience. Just as a “curtain line” makes us return after intermission, a cliff-hanging climax to a TV episode makes us tune in next week–or click to continue, if we’re binge-watching. Accordingly, storytellers reflect on how to chop up and lay out sections of their plots. Novelists fret over chapter divisions, TV writers massage their scripts to allow for commercial breaks, and playwrights map action into acts.

The idea of act-structure has passed into commercial screenwriting as well. Just when that happened is hard to say, but certainly by the 1980s scriptwriters consciously broke their screenplays into big chunks. That trend was largely the result of Syd Field’s 1979 book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, although some of his points had been anticipated in Constance Nash and Virginia Oakley’s Screenwriter’s Handbook (1974). From these books came the idea that a feature film script had a three-act structure, measured by time segments (30 minutes/ 60 minutes/ 30 minutes). The prototype was a 120-minute film, with each script page running about one minute of screen time. Field fleshed the model out by noting that “plot points” at the ends of acts one and two turned the conflicts in a new direction. Although other writers argued for other templates, and Field’s model was refined (what’s the “inciting incident” in Act One?), versions of the three-act model still rule the international film industry.

Field presented his anatomy as an analysis of hit films like Chinatown and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He suggested it as a template for a successful plot. As Field’s book gained prominence, his guidelines gave production companies an heuristic for triaging submissions. Now a story analyst could simply check pages 25-35 and 55-65 for turning points, and “incorrect” scripts could be discarded immediately. (But see P.S. below.) Through a feedback cycle, the Field model became a guide to both screenwriters and industry decision-makers. Inevitably, the whole thing got mocked. The day-by-day structure of Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang parodies Field’s scheme, and it closes with a self-conscious epilogue. “So,” says the narrator, “that’s pretty much that….”

To what extent, though, was the three-act structure employed in earlier eras? Field’s original edition drew its examples from current hits, but he implied that classics would display the same underlying architecture. Kristin, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, claimed that four parts were more common than three, and she supported her analysis with examples from films from the silent era and the classic studio years.

But film analysis depends on your perspective. In any movie you can find patterns different from the ones I find, and each of us can make persuasive cases. It would be valuable to know whether American screenwriters in the studio system consciously worked with an act-based model. If they did, what assumptions did they make about the length and organization of each act?

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

For some time, I’ve held the same view. I couldn’t find any script draft broken into acts. Some veteran screenwriters admitted using a three-act model in plotting, but their testimony came long after the era. So, for instance, Philip Dunne says he used a three-act organization for his 1940s screenplays, but he makes the claim in an interview published in 1986. Billy Wilder says he “wrote [Charles Boyer] out of the third act” of Hold Back the Dawn (1941), but the remark comes in an interview given decades later. There’s always the possibility that older writers, newly aware of the Fieldian template, were projecting it backward onto their work—assuring us that they conform to contemporary standards, or even asserting precedence.

Similarly, we can’t rely too much on secondary sources. True, screenplay manuals, from at least 1913 onward, have recommended a three-part structure, purportedy corresponding to Aristotle’s idea that a plot must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But this rests on a misunderstanding. As I’ve mentioned before, Aristotle isn’t talking of acts; ancient Greek plays didn’t have act divisions. And almost none of the manuals use the term “acts” to describe the parts.

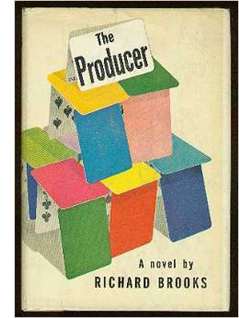

Richard Brooks’ novel The Producer (1951), about a weak-willed executive trying to do the right thing, offers some hints along similar lines. He mentions that a screenplay should run to 120 pages, confirming the canonical length that Field proposes. Likewise, Brooks obliquely appeals to Aristotle.

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter has to create a beginning, a middle and an end, and all the dialogue.

Perhaps there’s an intentional irony in the fact that Brooks’ Hollywood exposé is itself broken into three parts, labeled “The Beginning,” “The Middle,” and “The End.”

Unlike many authors of manuals, Brooks was an established screenwriter, and we might expect his novel to refer to acts. It doesn’t. But Lewis Herman, a minor scribe with three screen credits (including Anthony Mann’s Strange Impersonation), does. His 1952 manual declares that a feature-length film is built upon “a three-act theme outline.” The context suggests that the Hollywood studios demand this as a step toward developing a full screenplay. Herman usefully illustrates the outline with a hypothetical example.

Still, manuals or novels aren’t ironclad sources for studio practice. Better would be contemporaneous evidence from memos, story conferences, and similar unpublished documents. Claus Tieber has done extensive research into such sources and has found no discussions of three-act structure. I’ve found a few, but they’re fairly sketchy.

Overseeing Casablanca, Hal Wallis told Michael Curtiz, “The Epsteins have agreed to deliver the film’s ‘second act’ the following day.” Darryl F. Zanuck mentioned the “last act” in correspondence about Viva Zapata! and On the Waterfront. Supposedly John F. Seitz asked Preston Sturges about the flashback structure of The Great Moment: “Why did you end the picture on the second act?” As I noted in an earlier entry, David Selznick’s papers record a story conference on Portrait of Jennie in which Jed Harris remarks: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” He adds that at this point the film “is about 1/3 gone.” This suggests that some practitioners thought of the parts as roughly equal in length. (Kristin’s model proposes that this was the case.)

It may be, of course, that three-act structure of some sort was so ingrained in studio writers’ habits that they didn’t have to discuss it explicitly. Field was addressing aspiring screenwriters who wanted inside knowledge, but as intuitive craft workers, the old contract writers wouldn’t be likely to spell out rigid rules about length and dramatic patterning.

Since corresponding with Steven for his book, I’ve found that one screenwriter explicitly invoked three-act structure in his working notes. And I’m embarrassed not to have noticed it earlier.

Coupling, recoupling, and Joe Breen

F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sheilah Graham.

NICOLAS: Marriage has its phases–its acts–like anything else. This is another act, that’s all.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, screenplay for Infidelity.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Hollywood career was mostly a fiasco. Thanks to temperament, a mentally disturbed wife, bouts of breakdown and alcoholism, and an implacable industry, he worked his way down the hierarchy to unemployment. From July 1937 to his death in 1940, he earned screen credit for just one film, Three Comrades (1938). He also started, but didn’t finish, the best Hollywood novel I know, The Love of the Last Tycoon (aka The Last Tycoon). I think it spells out some features of the Hollywood aesthetic with special vividness.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

Back in the present, to ramp up his mood, Nicolas decides to hold a party in the country estate he had more or less abandoned. At the same time, Althea rekindles her friendship with a former suitor, Alex. She can’t arouse herself to passion, though, and Alex leaves her. As she drives more or less hysterically to the estate where the party is in full swing, Nicolas is wandering through his mansion among the shrouded furniture.

At this point, because of objections from the Production Code office, Stromberg halted Fitzgerald’s work on the screenplay. Aaron Latham’s biography tells us that Fitzgerald had planned to present a reconciliation, in which a photographic trick presents Althea seeing herself as Iris and thus forgives Nicolas. But this ending would suggest that the husband’s sin went unpunished. Fitzgerald suggested an alternative, but this too was rejected by Joseph Breen. He tried to redraft the script later in 1938, but the project dissolved.

Fitzgerald had systematically studied Hollywood releases, even filing plot synopses on index cards. Accordingly, the Infidelity screenplay we have shows an awareness of 1930s storytelling conventions: montage sequences, wordless scenes, and revealing visual detail. We learn that Nicolas’ ardor is cooling when we notice that he has stopped opening Althea’s letters. Fitzgerald’s acquaintance with current trends led him to a thumbnail characterization of Althea’s friend Alex:

He is the type played by Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth–handsome, attractive, worthy, thoroughly admirable, but somehow too heavy in manner to grip the sympathy of an audience if playing opposite a man of charm.

Occasionally, voice-over dialogue in the present is matched with images in the past, in the manner of Sturges’ “narratage” in The Power and the Glory. (See our entry here.) And the large-scale flashback structure, leaving a key action in the present suspended for nearly an hour, anticipates a mode of construction that would be common in the 1940s.

Despite its up-to-date air, the plot of Infidelity creaks a bit. It relies on a great many coincidences and introduces rather late a major menace, a sinister surgeon who seems slated to play the disruptive role of George Wilson in Gatsby. But what’s of special interest to us is a schedule of work that Fitzgerald sent to Stromberg during the planning stages.

Fitzgerald groups his scenes into clusters, and alongside each one he notes a date on which he expects to complete it. Since each scene usually runs only a couple of pages, the groupings present a feasible day-by-day timetable. These clusters of scenes are gathered into eight “sequences,” labeled with Roman numerals. In the 1930s, a “sequence” meant, according to screenwriter Frances Marion, “a series of scenes in which the action is continuous without any break in time.” Each of Infidelity‘s sequences presents a unified phase of the action and is more or less continuous in time, although there are some ellipses as well.

Here’s the news: Fitzgerald’s timetable assembles the sequences into acts. Sequences I through IV are labeled “FIRST ACT 45 pages.” Sequences V through VIII are labeled “SECOND ACT 50 pages.” Sequence VIII is continued to form “THIRD ACT 25 pages.”

The first act establishes the loveless marriage and launches the flashback. While Althea is away, Nicolas re-encounters Iris. Meanwhile, as Althea and her mother are on their way home, they conveniently run into her old beau Alex. Their departure for the United States ends this setup. In the screenplay Fitzgerald has typed: “The First Act may be said to end here.”

The second act develops the conflict to a point of crisis. Althea returns a week early to find Iris at breakfast with Nicolas. She resigns herself to a loveless union. Back in the present, he plans the party and at the instigation of Althea’s mother Alex starts to woo her. But he abandons Althea, and by chance she’s found by Dr. Borden, whom she starts kissing. In the notes for Sequence VIII, Fitzgerald cryptically ends the act on an alternation between the couples:

CUT TO husband and back to old beau [Alex]

[Alethea] with beau [Alex]

Crisis with beau and switch [to the surgeon, Dr. Borden?]

CUT TO husband

After presenting this alternation in scenes, the manuscript concludes:

Full shot of a bedroom, large and luxurious like everything else in this house. Soft lighting, everything covered with cloth or canvas.

Nicolas Gilbert is standing in the middle of the floor.

Close shot of Nicolas.

This is presumably the end of the passage labeled “CUT TO husband.” In the Stromberg schedule, this last portion marks the end of Act Two. Act Three isn’t in the canonical version of the screenplay.

A couple of final points about the structure. Although the screenplay is estimated at 120 pages, its proportions don’t conform to the Field paradigm. At 25 pages or minutes, the third act is short. This is a characteristic of both modern and older Hollywood climax sections. But Act One was projected to be very long at 45 pages, and Act Two approximates it at 50. Fitzgerald’s layout is perhaps more characteristic of a stage play, which can afford a longish exposition and equivalent second act. In the script version we have, both acts run equivalent page lengths.

Fitzgerald may have expected some trimming and compression at later stages. In The Producer, Brooks’ protagonist notes that a 120-page script would usually be cut down to 90 minutes because exhibitors wanted films at about that length. It’s true that few films of the studio era run to two hours.

Set aside brute measurements. What, in Infidelity, makes an act a coherent unit? Not a specific span of time. Act One breaks off partway through the flashback, and Act Two ends before the evening party does. The first act ends when we know a crisis is coming: Althea is returning home early and hasn’t told Nicolas, whom we’ve seen flirting with Iris. Act Two ends at another high point. Nicolas confronts the emptiness of his life without his wife, and nearby Althea is heedlessly making love to a stranger with dubious designs. We could easily imagine the script as a stage play, with a curtain ringing down on each of these teasing situations.

In sum, we have one clear-cut case of a studio screenwriter laying out his plot in three acts. We can’t generalize from a single instance, of course, and we would need many more pieces of evidence to consider this a widespread writing strategy. Perhaps Fitzgerald isn’t typical. Did his relative inexperience as a screenwriter make him rely on a theatrical template that others could do without? Did he employ it more as a rhetorical device to convince Stromberg that the plot was firmly constructed? Still, taken with the reminiscences of Dunne, Wilder, et al. and the sketchy mentions we have in production records, the Infidelity project suggests that some conception(s) of three-act structure were operative in the studio period.

Needless to say, we’ll need even more evidence before we can begin to consider whether the filmmakers’ craft practice matches the structural patterns that today’s analysts disclose in the films. The search continues!

The Fitzgerald outline is reproduced on pp. 161-162 of Aaron Latham, Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood (Viking, 1971). This book is not only a stimulating account of the novelist’s Hollywood years but also a helpful view of the movie colony’s culture. My discussion relies upon the version of Infidelity published in Esquire 80, 6 (December 1973), 193-200, 290-304. It is available in a digitized version here. The original manuscripts are in the University of South Carolina library.

Philip Dunne’s remarks about three-act structure are in Pat McGilligan, Backstory (University of California Press, 1988), 158. Billy Wilder’s remarks come in George Stevens, ed., Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age (Knopf, 2006), 316. (In the same interview Wilder claims that Some Like It Hot has four acts.) Richard Brooks’ The Producer (Simon & Schuster, 1951) is worth reading for its almost documentary survey of the process of production at the period. Lewis Herman’s Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films (World, 1952) is an unusually detailed guidebook.

On Wallis’ memo about Casablanca‘s second act, see Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Visual Design Program of Casablanca,” Post Script 9, 3 (Summer 1980), 38. For Zanuck’s comments see Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years at Twentieth Century-Fox, ed. Rudy Behlmer (Grove, 1993), 173, 226. Seitz’s remark to Sturges about The Great Moment is quoted in James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt, Brace, 1982), 172. There’s more discussion in our blog entry on The Great Moment.

I take Frances Marion’s definition of “sequence” as a bundle of scenes from her How to Write and Sell Film Stories (Covici-Friede, 1937), 373. Tamar Lane offers a comparable definition in his New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936), 123. Interestingly, Lane adds that some scenarists think of each sequence as moving toward a high point, like an act in a play; but this seems only a rough analogy, and the comparison entails that a script would have several more “acts” than three. Steven Price suggests that the “sequence” as an extended script segment emerged in the silent period and hung on in some sound screenplays; see A History of the Screenplay, especially 63, 115-116, and 153-157. At the same time, “sequence” could refer to a single brief segment, as in “action sequence” or “montage sequence.”

Thanks to Steven Price and Claus Tieber for correspondence about act structure. Claus has a relevant case study of Grand Hotel, “‘A Story Is Not a Story But a Conference’: Story Conferences and the Classical Studio System,” in Journal of Screenwriting vol. 5, no. 2 (2014): 225-237. More generally, I’m grateful to researchers at the Screenwriting Research Network for what I’ve learned from their conferences in Brussels in 2011 and in Madison in 2013.

Other entries on this site have considered act structure. Kristin explains her model, based on goal formulation and injections of new information. She expands on this as it affects character subjectivity and point of view. I illustrate her model with reference to what is supposedly the most wayward and narratively fragmented modern genre, the action picture. I offer some general reflections on how the four-part structure informs not only current films but best-selling novels. For a more general discussion of the dimensions of film narrative, you can download this chapter from my Poetics of Cinema. Also, too: there’s the precept that form follows format. Finally, I consider modern trends in screenplay construction, including act structure, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

After a while you see the triplicate scheme everywhere. In Case History of a Movie (1950), p. 30, Dore Schary says that Charles Schnee turned in the script of The Next Voice You Hear in thirds. Acts? I’ll have to get back to you.

P.S. 19 May 2014: In reply to this post, Greg Beal comments that my discussion of rejecting screenplays based on Field’s plot points is inaccurate.

My claim was, I now think, an overstatement. I should not have suggested that the absence of canonical plot points would be sufficient to doom a screenplay. Naturally, I realize that the analyst would still be obliged to write fuller coverage. I meant simply that the Field template could set up expectations that the script wasn’t written to standard. Other factors would surely be taken into account in a final decision. The larger point, that three-act structure along Field’s lines shapes analysts’ judgment, remains to be determined.

My most concrete evidence for the saliency of the three-act, plot-point model in this production context comes from two manuals by story analysts. T. L. Katahin’s Reading for a Living: How to Be a Professional Story Analyst for Film and Television (Blue Arrow, 1990) recommends that analysts look for three acts, including a ten-page initial setup followed by a development and two further acts that forward the protagonist’s goals. But Katahin doesn’t propose exact page counts for further twists.

More specific is Jennifer Lerch’s 500 Ways to Beat the Hollywood Script Reader: Writing the Screenplay the Reader Will Recommend (Simon and Schuster, 1999). In following the three-act layout, she suggests that Act One, the setup, be consummated between pages 20 and 30 (ideally consisting of two scenes 10-15 pages each). Act 2, as per Field, is said to run long, up to pages 80-90, and typically consists of four to eight sequences (each 10-15 pages or so). This act is said to lead to a point of no return, the pivot-point for Act 3.

Lerch, who was a professional story analyst for the William Morris Agency for eight years, claims, “Your script’s setup can literally make or break your project in the Hollywood Reader’s eyes, particularly at some companies that instruct readers to stop at page thirty of a script if it looks substandard. You may have a great second act and climactic sequence, but Hollywood will never see it unless you give it a savvy setup” (91). Passages like this one led me to think that the Field template weighs quite strongly in analysts’ judgment. But I’ve never supervised story analysts, so I welcome Greg’s expert comment on the matter.

P.P.S. 20 May 2014: More information on Fitzgerald’s Infidelity screenplay and its act breaks. In a letter to Hunt Stromberg dated 22 February 1938, Fitzgerald wrote:

The first problem was whether, with a story which is over half told before we get up to the point at which we began, we had a solid dramatic form–in other words whether it would divide naturally into three increasingly interesting “acts” etc. The answer is yes. . . .

This point, the decision to sail, also marks the end of the “first act.” The “second act” will take us through the seduction, the discovery, the two year time lapse, and the return of the old sweetheart–will take us, in fact, up to the moment when Joan [later, Althea] having weathered all this, is unpredictably jolted off her balance by a stranger. This is our high point–when matters seem utterly insoluble.

Our third act is Joan’s recoil from a situation that is menacing, both materially and morally, and her reaction toward reconciliation with her husband.

Evidently the timetable reprinted in Crazy Sundays was prepared after this letter was sent. This letter is printed in F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (Scribners, 1994), 348-349.

P.P.P.S. 30 May 2014: I always enjoy getting correspondence from readers, and I must catch up by noting some other responses I’ve received. David Cairns, whose wonderful blog Shadowplay is always worth checking on (his latest post is on Hannibal, the TV show), writes with this comment:

Hold Back the Dawn (1941).