Archive for the 'Film history' Category

The enemy next door

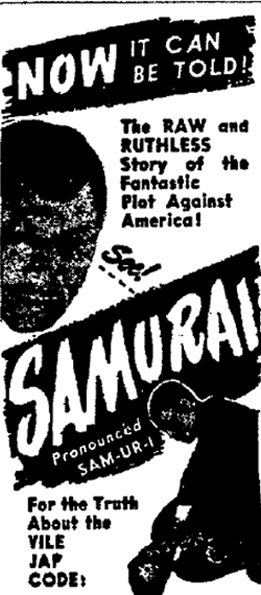

Left: Original caption: “Enforced farewell–These Japs wave farewell to relatives as they leave for Manzanar reception camp” (Los Angeles Times, 24 March 1942, p. B). Right: Advertisement for Samurai (Fitchburg [MA] Sentinel, 23 January 1946, p. 5).

DB here:

World War II never goes away, as the current attention given to Hollywood’s relation to Nazi Germany indicates. Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler and Ben Urwand’s The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler trace how the American studios responded to the rise of Nazism and the launching of hostilities. While working on 1940s Hollywood, I ran across two films that deal with another member of the Axis. They remind us of some painful incidents in our history, and they show how inflamed patriotism can burst into racial panic and oppressive public policy.

Call it a mass migration

Soon after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, there arose a fear that saboteurs were at work in America. No solid evidence of this was demonstrated, but the most powerful decision-makers were not in a mood to be tentative. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed an executive order that authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to demarcate areas from which anyone could be excluded. The Pacific coast was declared such a zone.

In early 1942, the US Army rounded up 110,000 California residents of Japanese ancestry and sent them to what were called concentration camps. (At that point the term simply meant a camp in which enemy populations were “concentrated.”) The evacuees were dispersed to makeshift camps throughout California, as well as in Wyoming, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington state.

Some of the internees were first-generation immigrants, but about 90,000, were citizens. A 1942 government documentary film presents the “relocation” process as necessary for national security, and it shows the evacuees accepting, in a spirit of patriotic submission, the need for such measures. In the film the evacuees effortlessly re-create their communities in their new locations.

Bizarre as it sounds today, the film takes pride in showing that a democracy can create humane concentration camps. But a reading of Richard Lingeman’s Don’t You Know There’s a War On? points up some things the film doesn’t say. The film doesn’t mention that the people rounded up were forced to abandon their homes, businesses, and farms and were permitted to take only what they could carry. (Newspapers often described the relocation as “voluntary.”) The film doesn’t show that the relocation centers were jerry-built, some by the inmates themselves, and were often located in harsh climates. The camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, was subject to sandstorms, blizzards, and subzero temperatures. Nor does the documentary note that the camps were enclosed in barbed wire and watched over by armed guards in security towers. Nor does the documentary show that, because Japanese-American farms produced 40 percent of the California vegetable crop, rival growers pressed for the internment and then snapped up the displaced farmers’ lands at what Lingeman calls “eviction–sale prices.”

The Japanese weren’t unique in undergoing internment; other ethnic groups were subject to investigation, confinement, and relocation. But no other minority was subjected to such a comprehensive roundup. It’s estimated, for example, that about 11,000 German-Americans, innocent or suspected, were interned–a significant violation of their rights, but nothing on the scale of Japanese internment. White people of European extraction, German-Americans had become pillars of American society, and were very numerous. (They were and remain the largest U. S. minority self-identified by descent.) Japanese-Americans, a much tinier and more vulnerable minority, were more easily marked as potentially alien to American values.

Late in 1942, the government began resettling Japanese-American internees outside the camps, spreading them to several states. In December of 1944, partly as a result of a Supreme Court decision the government could not consign “concededly loyal” citizens to camps, authorities declared that the west coast was no longer a war zone. But fears of Japanese espionage didn’t subside, as we can see from a 1945 independent film called Samurai.

Pledged to the God of War

Samurai shows an adopted Japanese boy growing into a traitor and spy. In September 1923, Mr. and Mrs. Morrey rescue Kenkichi from the ruins of the Tokyo earthquake and bring him home to San Francisco. While attending school and assimilating into American society, Kenkichi secretly visits a Buddhist temple where the priest inculcates him in the martial tradition of Bushido, the way of the samurai. Studying to be a doctor, Kenkichi becomes a proficient painter. At the same time, he swears to live and die by the sword, repeating the priest’s pledge that “The God of War presents the key to eternal life!”

The unsuspecting Morreys send Kenkichi to Italy and Germany for his studies, and the priest exhorts him make contacts that will train him as a secret agent. Back in America he begins painting abstract landscapes that conceal military information in coded form–a strange version of that motif of paintings and portraits that winds through 1940s American cinema (The Two Mrs. Carrolls, Suspicion, The Ministry of Fear). When the painting is abstract and nonrepresentational, it usually suggests that the painter may be mad.

Telling his parents that he will be a curator of Asian art, Ken goes to Tokyo and there, at the Black Dragon Society, he decodes his paintings. The Dragon Society’s leader suspects that his visitor is an American spy, but the doubts are dispelled when Kenkichi alters photos from Shanghai to appear that the Japanese are aiding the Chinese. Ken further proves his loyalty by murdering a journalist. He is assigned to the unit of General Sujiyama as a full-fledged spy.

Back at home, Kenkichi tells his priest of his mission, and shows what his reward will be: When the Japanese take over the west coast, he will become governor of California. Explosives are smuggled in, and Japanese farmers (“another link in the chain,” the voice-over narrator tells us) are coordinating domestic spies and saboteurs. The Morreys’ younger son Frank discovers Ken’s plot and tips off the police, while Kenkichi tries to convince the parents that he’s a double agent—before stabbing his father to death. Meanwhile, the invasion has been synchronized with the Pearl Harbor attack. At the climax, the temple priest realizes that his spy network has been arrested and his plan has failed. He commits ritual suicide, but Kenkichi, after brandishing the long samurai sword boldly, doesn’t follow the warrior’s way and instead flees to the beach. There he’s shot down by the police.

Premiered in New York in August 1945, after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Samurai seems to have gotten a very limited release. It’s a cheap production, filled out with montages of newsreel footage, feeble special effects (the back-projection of the Kanto earthquake is especially jarring), and minimalist studio sets. Chinese actors, some with prior Hollywood experience, played the Japanese characters. The device of Kenkichi’s coded paintings seems to be borrowed from illustrative examples of espionage techniques filed as evidence in the 1942-1943 Dies Committee investigation. The We-want-your-white-women motif is made salient in a scene in which Ken and General Sujiyama disport with women captives. Ken toys with a blonde before tripping her.

During the same scene, a Chinese woman fights off the General’s advances before tearing up the Japanese flag. As was typical of the period, the Chinese were presented as courageous and defiant in the face of the Japanese invasion.

Samurai was planned in 1943 under the title “Confessions of a Japanese Spy,” an echo of Warners’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy of 1940. According to the AFI entry, another working title was Orders from Tokyo. Producer Ben Mindenburg supplied the story, and the director Raymond Cannon (who worked intermittently at Fox, Monogram, and elsewhere) is credited with the screenplay. Scenes suggesting rape of the General’s captive women displeased the Production Code Administration. The picture was awarded a PCA seal eventually, so perhaps some portions were omitted.

110,000 people inconvenienced

As a minor independent production with small circulation, Samurai can be dismissed as an outlier. It apparently wasn’t reviewed in Variety, but the New York Times called it “an example of opportunistic filmmaking . . . lurid and sensational. At this late hour, a motion picture should do something more than just shout, ‘The Japanese are brutal, scheming beasts.’” Yet three years before, in summer of 1942, Twentieth Century-Fox released a B-film that is hardly less virulent, and the Times, though finding it a “mediocre melodrama,” paid homage to its authenticity in pinpointing “details about incidents of espionage plotted in Los Angeles’s Japanese colony.”

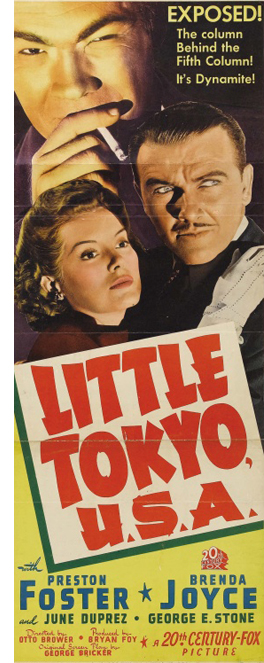

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Steele’s investigation is blocked when he can’t find the radio used by one of the gang to receive instructions from Tokyo. Takimura murders Teru, Hendricks’ Japanese mistress, and Steele is framed for the crime. Steele is in prison when Pearl Harbor is attacked. As “dangerous aliens” are rounded up, he escapes and finds Takimura’s hideout. Mavis, who has been skeptical of Steele’s suspicions, is taken captive by the gang. Takimura finds Steele hiding out in the city morgue. But when they confront Steele he springs a trap of his own: cops burst in and seize the conspirators. The film concludes with Mavis broadcasting the need to stay vigilant.

If Samurai crudely employs techniques of current semidocumentary (voice-over narrator, newsreel footage, some location shooting), Little Tokyo, USA remakes the G-man film into an affair of domestic espionage. We get the familiar frame-ups, the silhouettes and night streets, and the montages of headlines and police dispatches. Given how supple Fox’s B-pictures often were in the 1930s, with the Moto and Chan films and the Sherlock Holmes series, this is a very routine affair. The major Japanese villains are played by Caucasians in Yellowface; even the ubiquitous Abner Biberman (in the poster at right) is recruited to look Japanese.

Unlike Samurai, Little Tokyo, USA indicates that there are loyal Japanese-Americans like Steele’s friend Oshima. Nonetheless, the film buys wholly into the notion of a pervasive Japanese menace. A voice-over prologue presents this as a “film document,” and provides a montage of Japanese men photographing industrial and military sites much like those Kenkichi scouted in Samurai. More subtly, after Pearl Harbor, members of Takimura’s gang are shown putting up signs in their shops claiming to be patriotic citizens—something that many innocent Japanese-Americans did to forestall reprisals. Takimura even establishes a charity that purportedly finances the building of bomber planes.

Beyond spreading a general mistrust, the film aims to justify Japanese-American internment. To do this, it has to show that, as the prologue’s voice-over puts it, before Pearl Harbor Americans had been lulled into a false sense of security by “the mouthing of self-styled patriots.” So we meet several characters who exhibit fatal naivete. Early in the film, Mavis’ broadcast voices her hopes for peaceful negotiation with the Japanese. After Japanese-Americans protest Steele’s investigation, his superior claims:

The Japanese are peaceful, harmless, industrious citizens. They’re loyal too—most of ‘em. ‘Course there may be some rats in the bunch, but that’s nothing to get excited about. I was reading only this morning that 93 percent of the vegetable crop of California is in the control of the Japanese.

Steele replies:

Yeah, I know. They’ve got farms right next to all the airplane factories, and the dams, and the oil-storage concentrations.

He goes on to claim that the farmers lose money, but they’re subsidized by funding from a Tokyo bank.

On the other side, Takimura warns his gang that internment is what he fears most. “Mass evacuation will defeat our operation here.” Fortunately, he remarks confidently, evacuation will be blocked by Japanese civic groups and “certain sympathetic American interests.” This phrase casts anyone who might object as an unwitting tool of the Axis.

A new problem arises when the film must admit that not all 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry on the coast could be Fifth Columnists. So, like the government documentary, and like the LA Times news photo of grinning men bound for a resettlement camp, Little Tokyo, USA treats the innocent evacuees as accepting internment in a cheerful spirit. It’s proof of their patriotism and their contribution to the war effort. Here are the film’s final scenes, including some documentary footage of relocation and the empty streets of Little Tokyo.

At the denouement Steele punches Takimura (“That’s for Pearl Harbor, you slant-eyed–“) and Steele’s captain abandons his misplaced sympathy by clobbering the “squarehead” Hendricks. In the final scene, Mavis, her eyes now open, uses her broadcast to explain the need for some to sacrifice.

And so in the interests of national safety, all Japanese, whether citizens or not, are being evacuated from strategic military zones on the Pacific Coast. Unfortunately, in time of war the loyal must suffer inconvenience for the disloyal.

As happens today, those calling for sacrifice from others usually give up nothing themselves.

I offer no fancy analysis of these humdrum films. It simply seemed to me that, on the eve of the anniversary of the US bombing of Nagasaki, it would be worth remembering how quickly Americans in a state of war could find enemies among civilians overseas and in our cities here. Among us today there are many who would happily call for some American minority to be rounded up, locked up, sent away, put out of sight somehow. Look around you, as Resnais and Cayrol remind us in Night and Fog, and you will see the eager faces of future jailers.

Thanks to the staff of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium for permitting me to view Samurai. On the role of race in the Pacific War, see John Dower’s War without Mercy. The Dies Committee, later known as the House Un-American Activities Committee, produced a report on Japanese espionage that makes astonishing reading. Here is one passage:

California, with its mild climate and extraordinary agricultural resources, delighted the industrious Japanese. In fact, some of their vernacular newspapers went so far as to call California ”the New Japan.” They were not content to remain day laborers, as had the Chinese, but rapidly acquired their own land, or leased farm land which they frequently worked to depletion. Their women worked alongside the men in the fields for long hours, often with their babies strapped to their backs. Whole towns became Japanese, the native white population gradually leaving areas where the Japanese settled, since competition with them was so difficult if not impossible. They were assertive and aggressive, and did not achieve the reputation for honesty and faithfulness that was enjoyed by the Chinese. California fearfully envisioned the complete control of her agricultural land by the acquisitive Japanese, and became thoroughly aroused. Feeling ran high, but there was little of the violence against the Japanese which had unfortunately marked the agitation for exclusion of the Chinese.

The New York Times review of Samurai appeared on 24 August 1945, p. 7. Variety‘s review of Little Tokyo, U.S.A. appeared in the issue of 8 July 1942, p. 8, and the Times review was published on 7 August 1942, p. 13.

Interestingly, the documentary Japanese Relocation appropriates portions of Virgil Thomson’s scores for Pare Lorentz’s documentary The River (1938), and I think I heard a bit from The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) as well. Presumably the government owned the rights.

Every day brings a fresh example of highly-placed and lunatic bigotry against immigrants to the US. Consider this. Or this.

The photograph below of a Nagasaki in 1946 is from the National Archives; I have taken it from the site About Japan. The quotation at bottom is from Life magazine, 20 August 1945, 27.

Seventy-five hours after the world’s first atomic bombing, an interval marked by President Truman’s demand for unconditional surrender, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, shipbuilding port and industrial center. This bomb was described as an “improved type,” easier to construct and productive of a greater blast. It landed in the middle of Nagasaki’s industries and disemboweled the crowded city. Unlike the Hiroshima bomb, it dug a huge crater, destroying a square mile–30% of the city.

When the bomb went off, a flier on another mission 250 miles away saw a huge ball of fiery yellow erupt. Others, nearer at hand, saw a big mushroom of smoke and dust billow darkly up to 20,000 feet and then the same detached floating head observed at Hiroshima. Twelve hours later Nagasaki was a mass of flame, palled by acrid smoke, its pyre still visible to pilots 200 miles away.

The bombers reported that black smoke had shot up like a tremendous, ugly waterspout. Physicists at the bomber base theorized that this smoke was the pulverized fragments of the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works. With grim satisfaction they declared that the “improved” second atomic bomb had already made the first one obsolete.

The other Kurosawa: SHOKUZAI

Shokuzai (2012).

DB here:

This year’s trip to Brussels and the Royal Film Archive of Belgium was more low-key than usual. The Cinematek’s mini-festivals were suspended this year, with Cinédecouvertes to resume next summer and the L’age d’or competition to get its own slot in the fall. The usually reliable Écran Total series at the Galeries Cinema was gone, replaced by mostly recent releases. The Cinematek’s main venue was featuring America in the 1980s (not to be despised, but these items were familiar to me) and Antonioni, because of the current exhibition devoted to him in the Musée des Beaux-Arts. And even my archive viewing was slimmed down to only a few days, as I watched some 1940s American features too obscure even to circulate on bootleg DVDs.

I wasn’t exactly bereft of choices, and I could occupy my time preparing for my Antwerp lectures on Ozu, but I was angling for something special. Luckily, our old friend Gabrielle Claes, recently retired as Director of the Cinematek, called my attention to a one-off showing of Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Shokuzai (“Penitence,” 2012) at Cinéma Vendôme, a local arthouse. The bonus: Kurosawa in person! So of course Gabrielle and I went.

Before and after the movie, I began thinking about his career and his place in recent Japanese film history.

Making waves in the 90s

Sonatine (1993).

During the 1990s a new generation of Japanese directors came to international attention. Thanks to home video formats, as well as to a rising taste for international crime and horror films, western audiences became aware of filmmakers from many countries who unabashedly worked in low-end popular genres. The success of Hong Kong films in 1980s festivals had made programmers open to Asian pulp fictions. Soon commercial companies saw a fan market for video versions of movies that were unlikely to get theatrical distribution outside Japan. These films changed forever the image of Japanese cinema as a refined and dignified tradition.

Admittedly, Western views of Japanese film were probably too sanitized. Ozu never shrank from bawdy humor, Mizoguchi could display acute suffering, and Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sanjuro were exceptionally bloody by 1960s American standards. Still, things had gotten quite wild in later years. Films that weren’t widely exported, such as those exploiting juvenile-delinquency, yakuza intrigues, and swordplay, as well as the softcore erotica known as “pink” films, would have shown western audiences something quite surprising. In the 1980s, charmers like Tampopo, The Funeral, and other export releases could hardly have prepared audiences abroad for the cinema of shock that was becoming common at home. Perhaps only Ishii Sôgo’s Crazy Family (1984), widely circulated in Europe and America, hinted at what was ahead.

The oldest provocateur was Kitano Takeshi (born, like me, in 1947), who came to directing after a solid career as a comedian. His Sonatine (1993) established him as master of the impassively violent, disturbingly amusing gangster movie. I don’t think anyone can forget Sonatine’s elevator-car shootout, which is unleashed after an awkward, semicomic passage of passengers behaving as we all do in an elevator, adopting neutral expressions and avoiding each other’s eyes. The most celebrated director of this group, Kitano influenced action filmmakers around the world and probably helped spark a revival of interest in classic yakuza pictures.

Other directors were younger and got their start in more marginal filmmaking. Tsukamoto Shinya had worked in Super-8 since childhood and made his breakthrough film, Tetsuo (1989) in 16mm, which became a cult hit on worldwide video. Soon Tetsuo II (1992), Tokyo Fist (1995), Bullet Ballet (1998), and other films showcased a frenetic, assaultive style that was the cinematic equivalent of thrash-rock. Miike Takeshi made several V-films before he hit international screens with Audition (1999), and soon his earlier theatrical releases Shinjuku Triad Society (1995) and Fudoh: The New Generation (1996) became staples of cult screenings and video collecting. Miike pushed things over the edge. Even Kitano did not dare to show a schoolgirl assassin firing deadly darts from her vagina.

I don’t mean to suggest that these directors were sensationalistic all the time. Miike made children’s films, a discreet heart-warmer (The Bird People in China, 1997), a mystical drama (Big Bang Love Juvenile A, 2005), and classical swordplay sagas (Thirteen Assassins, 2010). Kitano developed his interest in prolonged adolescence through sentimental drama (A Scene at the Sea, 1991), Chaplinesque road movie (Kikujiro, 1999), symbolic pageant (Dolls, 2002), and self-referential absurdity (Takeshi’s, 2005, and others). Still, these two directors have often returned to the downmarket genres that launched their reputations.

Nor do I want to suggest that all the filmmakers emerging to wider awareness at this time were roughnecks. Kore-eda Hirokazu began his career in documentary films, followed by the solemn, elemental Maborosi (1995). Kawase Naomi, one of Japan’s few women directors, won acclaim with the sensitive rural drama Suzaku (1997), and Suo Masayuki became a top-grossing export with his satiric comedies Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (1992) and Shall We Dance? (1996). Yet Kore-eda, widely respected for his nuanced family films, made a movie centering on a sex dolly (Air Doll, 2009), and Kawase had worked for years on autobiographical documentaries dealing bluntly with family tensions, old age, and women’s oppression. Suo’s debut was a pink film called Abnormal Family: My Older Brother’s Bride (1984) in which an affectionate parody of Ozu’s style was used to present copulation, teenage sex work, and a golden shower.

In sum, in Japan the distance between serious art and more sensual, not to say shocking, cinema isn’t that great. To take a more recent example, who would have expected that the director of the quiet, deeply moving Departures (2008; Academy Award, Best Foreign-Language Film) would have learned his craft in a series centering on men who grope women on commuter trains? (Sample title: Molester’s Train: Seiko’s Ass, 1985.)

Mysteries, mundane and supernatural

Shokuzai.

Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s career fits the trend I’ve sketched. Born in 1955, he started with pink films and V-cinema, but the theatrical release Cure (1997) won festival berths and international distribution. It presents the now-familiar mixture of mystery story and supernatural tale, in which a detective with personal problems investigates serial killings and begins to suspect that the murders are performed under some mesmeric influence. In Charisma (1999) the supernatural elements dominate, as a police officer tries to understand the powers of a tree that can magically regenerate itself. Pulse (2001) locates the otherworldly forces in the Internet, where ghosts take over people’s lives and eventually lead humans to flee Tokyo.

Kurosawa’s films became perhaps too quickly identified with what was known as J-horror. His taut, slowly unfolding plots and calm but menacing style did have something in common with the Ring series (1998-2000) that was becoming popular at the time. At the same time, Kurosawa draws on a some story elements common across Asian crime and horror films: revenge, often by a parent or elder figure in the name of a lost child; the suggestion that childhood, especially that of girls, has a corrupt and sinister side; and a sense that modern technology such as computers and cellphones harbor demonic threats. But I think that his films were more thematically ambitious, even pretentious, especially in the case of Charisma, with its ambiguous ecological symbolism. And like his peers, he wasn’t interested only in suspense and shock. His mainstream family drama Tokyo Sonata (2008) attracted western viewers with no knowledge of his spookier side.

The policier aspect is evident from the start of Shokuzai. Originally a five-part TV drama broadcast in weekly installments, it starts with the rape and murder of a schoolgirl, Emili. Her four playmates have seen her attacker ask her to leave the playground with him, so when she’s found dead, the police and Emili’s mother Asako press the girls to identify him. Through fear or trauma, none of the girls can remember what he looked like. Asako summons all four to her home and demands penitence from them in the future—in ways each one must find for herself.

After this prologue, Shokuzai downplays supernatural elements in favor of character studies of the four surviving girls, with a “chapter” devoted to each. The young women live separate lives and their paths don’t intersect; only the implacable Asako reappears in each thread. By the final installment, Asako has more or less given up tracking the killer, but when one young woman accidentally recognizes him, on TV, Asako pursues him and discovers the roots of the crime in her own past.

This is pretty much modern thriller territory, with a whiff of Barbara Vine/Ruth Rendell in the film’s effort to trace how a single event resonates terribly through innocent lives. As with such thrillers, the strength of Shokuzai seems to me to lie largely in characterization and atmospherics. Each young woman is given a distinctive personality, and each one’s professional and personal life fifteen years after the crime is presented with a teasing, hypnotic deliberation. Sae is a meek, sexually immature nurse who is lured into marriage with a rich former schoolmate; his seemingly harmless obsession turns domineering. Maki becomes a schoolteacher herself, and her relentless, demanding methods soon antagonize the local parents—until she unexpectedly proves herself heroic. Akiko has become a hikikomori, a recluse, and is only briefly drawn out of her drowsy existence by the daughter of her brother’s girlfriend. The good-natured little girl in effect reintroduces Akiko to childhood. In the penultimate chapter, the sexual bargainer Yuka seeks to seduce her brother-in-law and to take revenge upon her sister for being their mother’s favorite.

Each young woman is associated with an object or gesture seen in the prologue: a French doll, a bloody blouse, a policeman’s kindly squeeze on the shoulder. At one level, these bits of the past take on psychological impact. The trauma around Emili’s death suggests sources of the grown-up women’s neurotic behavior. Maki, the girl who after the killing rushes frantically through the school looking for someone in authority, becomes an all-controlling schoolteacher. Akiko’s bloody school blouse will find its fulfillment in a brutal crime involving a girl’s toy.

Yet these associations carry extra resonances. It’s partly because of the quietly ominous way Kurosawa films commonplace objects like a ruby ring or a jump rope. Maybe there is a whiff of the supernatural after all, given the unexpected connections revealed between the men in the women’s later lives and the little girls’ fetishes and rituals. Fate plays such cruel tricks that it might as well be malevolent magic.

The demand for expiation and the mother’s implacable intervention in an investigation will remind many viewers of Bong Joon-ho’s Mother (2009, South Korea) and Nakashima Tetsuya’s Confessions (2010). Asako’s characterization gets fleshed out in the fifth episode, which presents two crucial flashbacks leading up to the crime. One even replays a moment leading up to the murder, supplying a previously withheld reverse-shot in the manner of Mildred Pierce’s replay. (Some things don’t change.)

Presumably the recurring flashbacks to the prologue were also motivated by the rhythm of the weekly TV broadcasts. Viewers couldn’t be expected to recall everything from earlier installments.

You can object, as critics have, that the revelations in Shokuzai’s finale are creaky and far-fetched. Raúl Ruiz, in Mysteries of Lisbon, embraces the arbitrariness of old-fashioned plotting, with its felicitous accidents, secret messages, and hidden identities. He scatters these devices freely throughout his story, making them basic ingredients of his film’s world. Instead, Kurosawa introduces most such devices at the last minute, which makes them more surprising but also more apparently makeshift. Still, you can argue that once you eliminate purely supernatural causes for the creepy things we see and hear, audiences will embrace convoluted plots (as again, in Confessions) to rationalize their thrills. As so often in popular narrative, no coincidence, no story.

Quiet elegance

Kurosawa uses long takes, fairly distant framings, and solemn tracking shots to heighten an atmosphere of dread. The questioning of the children is played out in an extreme long shot, refusing exaggeration but conveying very well the flat, obdurate refusals confronting the cop.

In the Q & A after the screening, Kurosawa explained that he didn’t alter his filming style much for the television series, although he found himself writing more dialogue than he would have included in a theatrical feature. His visual technique displays a dry, precise elegance–the Japanese might say it possesses shibui— and it has, as far as I know, no equivalent in current American cinema. The compositions are painstakingly exact, though they’re not as rigidly geometrical as Kitano’s planimetric images and they don’t self-consciously evoke Ozu in the way Suo’s do.

Everything lies in plain sight. The bright, saturated tones of the childhood prologue contrasts sharply with the wan color schemes throughout the present-day sequences.

Kurosawa’s staging has a clarity and point that’s rare today. He often lets significant action unfold without interruption. For example, in Yuka’s flower shop, he gives us a shot lasting nearly a minute. Yuka’s sister has come to voice her suspicion that her husband has had sex with Yuka. Kurosawa moves the two women around the frame discreetly, sometimes hiding their facial reactions, and using the Cross to shift their positions both laterally and in depth. A single step forward can mark rising tension as the sister demands an explanation, and a retreat from the foreground can create a mini-suspense about Yuka’s reaction.

After hiding Yuka’s reaction in the distance, Kurosawa creates a mini-climax by having her turn abruptly to the camera before bending over and sobbing.

Kurosawa saves the cut, as David Koepp might say, in order to ratchet the drama up. In a closer view we can watch the sister, ashamed of her suspicions, consoling Yuka and succumbing to her lies.

Contrary to what proponents of intensified continuity will tell you, you can build an engrossing scene without fast cutting, tight close-ups, and arcing camera movements. Like American directors of the studio era, Kurosawa always knows the best place to put the camera, and he keeps things simple and direct.

Kurosawa’s patient, compact staging has its counterparts in the work of Claire Denis, Manuel de Oliveira, and many other European filmmakers. It’s just that it’s a bit unexpected in the 1990s Japanese iconoclasts. For all their self-conscious extremism, they have wound up reinvigorating certain classic techniques of cinematic expression. This is just one of many reasons to catch Shokuzai on a screen, big or little, near you.

You can see some trailers and extracts from Shokuzai here, but you have to sit through a wretched Peugeot ad every time.

Shokuzai is coming to the Vendôme on 24 July.

On the earthy side of Japanese culture, which I think feeds into the 1990s trends I’ve mentioned, see Ian Baruma’s Behind the Mask.

P.S. 23 July 2013: Adam Torel of the ambitious Third Window Films writes to tell me that the company is releasing Eyes of the Spider and Serpent’s Path on DVD in September. Third Window distributes other recent Japanese films, including items by Miike and Tsukamoto.

Il Cinema Ritrovato, number 9 and counting

Kristin here:

For a second year running I unexpectedly ended up attending Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna alone. (For the 2012 report, see here.) Last year David’s back went out shortly before we were due to leave. This year an exceptionally long stretch of days with heavy thunderstorms resulted in flooding in our basement (where many of our books reside). I had already been in London for nearly three weeks and was planning to meet David in Bologna. Instead, he valiantly stayed home to deal with the unwanted water, and I went on to the expanding smorgasbord of films presented by the festival.

The programmers are limited to their existing venues: the relatively small Mastroianni and Scorsese auditoriums in the Cineteca’s building, the larger Arlecchino and Jolly commercial cinemas, and the vast space of the Piazza Maggiore for the nightly open-air screenings starting at 10 pm. This year for the first time, to accommodate the many films, post-dinner screenings, starting at 9:30, 9:45, or 10 pm, were scheduled in the Scorsese and Mastroianni.

Faced with so many options, one could only focus on a few of the bounteous threads of programming. I opted to see as many of the early Japanese sound films as possible, the early (pre-mid-1960s) Chris Marker works, and the annual Cento Anni Fa series, this year presenting a sampling of films from 1913, the year when worldwide the cinema seemed to take an extraordinary leap forward in complexity and inventiveness. Whenever there was a gap, I could fit in items from the other threads: European widescreen movies; cinema of the 1930s that presaged the coming war; a retrospective of the work of Soviet director Olga Preobrezhenskaja, another devoted to Vittorio de Sica, primarily as an actor, more Chaplin restorations from the Cineteca’s ongoing project, the newly restored Hitchcock silents, and of course various other newly restored films. A tradition of highlighting the work of a Hollywood director has become a centerpiece of Il Cinema Ritrovato, with the subject this year being Allan Dwan.

Japanese Talkies, Part 2

Last year I caught only a few of the films in the retrospective of early Japanese sound films. I regretted not being able to see more, but the Ivan Pyriev and Jean Grémillon threads lured me away. This year the rival was Chris Marker, but I determined that by careful planning, I could fit almost everything in both retrospectives into my schedule. These became my top priorities.

The Japanese series is ongoing and organized not by auteurs but by film companies. The programmers were again Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the history of Japanese studios of the 1930s made  for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

I had seen only one of the films in the series, Mikio Naruse’s 1935 masterpiece, Wife, Be like a Rose. I didn’t remember much about it, except that it was marvelous, and it proved so on second viewing. Naruse often has been compared with Ozu, both during his active career and since. Overall, he seems to me not as great a filmmaker, but Wife, Be like a Rose must be among his best films and would undoubtedly rank alongside some of Ozu’s work of this period. A moga (modern girl) is upset that her father has deserted his family in Tokyo and established another family in the countryside. Determined to drag him back to his familial responsibilities, the daughter confronts the possibility that he was right in leaving her mother. The film is shot in a somewhat Ozu-like style, with low camera heights and across-the-line shot/reverse shots. Still, there is no slavish imitation (the climax is filled with camera movements), and Naruse’s film is both moving and stylistically engaging.

Naruse was the only director with two films in the retrospective. His Five Men in the Circus, also released in 1935, was a less ambitious work than Wife, Be like a Rose, but it was an entertaining story of musicians on the road earning a living during the Depression, encountering disappointments in work and love.

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

The Japanese musicals were all charming films. Romantic and Crazy (1934) starred the popular comic performer Kenichi Enomoto, better known as Enoken. (In the West, he is most familiar from his comic role in Akira Kurosawa’s third feature, The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail [1945].) Romantic and Crazy is basically a college musical imitating the early 1930s films of Eddie Cantor–and at  moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

Another notable film was Sadao Yamanaka’s Kôchiyama Sôshun (1936), one of his three surviving feature films. (These and fragments of others are available on a new set from Eureka! in its “Masters of Cinema” series.) It’s a strange film, partly comic but mostly a crime story. An attractive woman, played by a very young Setsuko Hara, keeps a shop owned by a local gangster, and tries to prevent her thuggish younger brother from becoming a criminal. The title character, Kôchiyama Sôshun, appears to be an idler getting by on the income from his wife’s gambling house, but he apparently has unlimited sources of money. Despite his shady background, Kôchiyama tries to help save the heroine when, after her brother has gambled away the house and shop, she is forced to sell herself into prostitution.

The seasons of early Japanese sound films will continue during the 2014 Il Cinema Ritrovato, with a focus on Shochiku.

Chris Marker’s youth returns

It has been difficult to see any of Chris Marker’s early films lately. By early I don’t mean early 1950s, but essentially anything made before La jetée (1962). As Florence Dauman of Argos Films explained in an introduction to one of the programs, Marker thought of the films made during his first decade as a director as mere trials and didn’t want them seen again. Fortunately Dauman and others made the decision not to honor his wishes. Perhaps Marker thought that his later films, more complex and philosophical (Sans soleil comes to mind), were how he wanted to be remembered. But the playful, emotional, politically committed film essays of the 1950s and early 1960s are precious and not to be abandoned. We were treated to excellent restored prints of them during the festival.

The only film that made me understand Marker’s reluctance to show his early work was Olympia 52 (1952), a documentary on the Olympic Games in Helsinki. It was Marker’s first professional feature, and it is barely competent. The coverage sticks almost entirely to the track and field events, with endless 100-meter dashes, shot-puts, hurdles, high jumps, pole-vaults, and so on. The several cameras filming the events rendered very different footage, ranging from excellent to dark gray. Cut together, these shifting images look amateurish. A brief series of shots of yacht-racing, equine-jumping, and other sports leads back to more shot-puts, hurdles, pole-vaults, and so on. Valuable practice for Marker, no doubt, but a film which bears no hint of the talent soon to burst forth.

It was wonderful to see Letter from Siberia (1958) again after so many years. David and I had taught it in an introductory class in the mid-1970s. Its repeated series of shots of a bus on a street and some men doing construction work has been an example of the powers of the sound track from the very first edition of Film Art in 1979 to the present one.

There were no subtitles on the prints, and the headphone translation could never keep up with the rapid, contemplative voice that accompanied these images, so I missed much of the point of Dimanche à Pékin (1956) and Description d’un Combat (1960). Marker’s written contribution to Joris Ivens’ documentary …À Valparaiso (1963) presaged much of his later work. His 16mm documentation of American hippies’ gently protesting assault on the Pentagon in La sixiéme face du Pentagone (1968) made me proud to be an American (something not too easy in the light of recent events).

Dwan at his peak? The 1920s

I missed most of the Dwan films, but I managed to fit in three of the four from the 1920s. These did not include the 1923 Gloria Swanson vehicle Zaza, alas, though I heard good things about it from friends who saw it. The three I caught seemed to represent Dwan at the height of his career.

I had seen the other Swanson film, Manhandled (1924) before, but it was a treat to see it again. It’s a strange mixture of realism–most notably in the famous early scene of the working-class heroine’s commute home on a crowded subway–and an absurdly melodramatic plot in which she manages to attain the pampered stature of a kept woman while maintaining her virtue. Swanson is a delight, and the fact that the film is incomplete, missing a scene in which she demonstrates her talent for mimicry by imitating various characters, including Charlie Chaplin, is a true pity. We can only hope that a complete version will someday surface.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

As always it was a treat to hear anecdotes from the man who had the inspired idea of interviewing stars and filmmakers from the silent era before it was too late. The Iron Mask was another impressive print, dated 1999 and bearing a Carl Davis score. I much prefer Douglas Fairbanks in his early comedies to his more famous swashbuckler films, and the story and staging in this one seemed very by-the-numbers, especially in comparison to the more imaginative East Side, West Side. Its main interest, and that was considerable, lay in the impressive sets designed by Ben Carré and William Cameron Menzies and its glowing cinematography by Henry Sharp.

By the end of the week, I was happy to have caught these particular Dwan films. From conversations with people who followed his thread more closely, I gathered that they thought the 1920s titles were the best of those shown in Bologna.

Glimpses of 1913

There was a time when the Cento Anni Fa series, programmed by Mariann Lewinsky, was a must-see for me. With the proliferation of screenings, however, seeing all of the sessions has become difficult, and I found myself ducking in and out to catch a few items now and then. I wanted to see the new restoration of Mario Caserini’s remarkable feature, Ma l’amor mio non muore!, but there was something else I wanted to see playing opposite both screenings. Luckily the Cineteca has put the film out on DVD. The catalog claims that it’s the first diva film. It stars Lyda Borelli in a spectacular performance, plus it has many complex examples of what David calls tableau staging (see here), especially in the amazing set in the frame above. One of the must-see films of 1913.

I am not a great fan of Italian (or any other) spectacles set in ancient times, and there were quite a few included in the series. They also tend to be rather long, which makes it more difficult to fit them into a packed schedule. Still, I did like Spartaco ovvero il gladiatore della Tracia (Giovani Enrico Vidali). Its minor actors and extras avoided giving the usual impression of people milling around in sets; they actually behaved as if they were living in real places in antiquity. The actress playing Emilia (not listed in the catalog) gave an engaging performance, quite the opposite of the diva approach, though Mario Guaita as Spartaco depended largely on rolling his eyes upward at frequent intervals to convey suffering. As Ivo Blom points out in his program notes, however, Guaita turns out to be the the first strongman figure, bending iron bars with his hands a year before Bartolomeo Pagano supposedly innovated this iconic gesture as Maciste in Cabiria.

More than that film, though, I was impressed by Luigi Maggi’s La lampada della nonna. It begins with an old woman knitting beside an oil lamp. When her grandchildren try to present her with a new electric one, she objects. The bulk of the film is an extended flashback set in the era of the Risorgimento, with the heroine in her youth helping to shelter a wounded officer and falling in love with them. The lamp, seen unobtrusively in the background of several shots, comes to play a key role as a signal in the climactic scene. Again there is an unusual degree of naturalness in the acting, with the extras in the military campground scene, for example, all given bits of plausible action to collectively present the impression of an actual campground. The flashback structure, framing, staging, and acting all reminded me strongly of Griffith at the same period.

There were slight but charming films like Léonce et Toto, a very funny Léonce Perret comedy (director unknown, but probably Perret). Léonce’s wife receives a tiny chihuahua as a gift and immediately dotes on it, to the point of putting it on the table at meals. The hero is disgusted and tries increasingly devious and extreme ways of getting rid of the little pest. Another was an American documentary with the irresistible title Aquatic Elephants. Who would not delight in five minutes of elephants rolling cheerfully in a pond while silly men try to stand on them and invariably fall into the water?

DVDs and Blu-ray

Just about every film scholar and buff in the world probably knows the Criterion Collection. As a brand, it’s sort of the Pixar of high-end home-video. We all have at least some of its releases on our shelves, whether lined up alphabetically or by director or by number. This year a session was devoted to the background of the company, with guests Jonathan Turell and Peter Becker (left and right, above). The history of Criterion is a bit complicated. Briefly, it was founded in 1984 to release laserdiscs and eventually, after the introduction of DVDs in 1997, switched to that format, eventually adding Blu-ray discs. Becker joined the company in 1993.

Criterion is closely linked to the historically important Janus Films, founded in 1956 and responsible for distributing many of the most famous art films of subsequent decades. In 1966 it was acquired by Saul J. Turell and William Becker, the fathers of the two speakers. Their sons are now co-owners of the Criterion Collection, of which Peter is the president; Jonathan is director of Janus.

To David’s and my generation of film students, Janus was a key player in our discovery of art cinema. How many of us, I wonder, first watched many of the classics that now grace Criterion DVDs through the landmark PBS series, “Film Odyssey,” in 1972? I first saw and was bowled over by Ivan the Terrible in that series. Three years later, when I was working on my dissertation on the film, I called Janus and got through to Saul Turell. Could I possibly borrow 35mm prints of the two parts of the film, I asked, explaining that I needed and to take frames from good copies. He gave me the name and phone number of a person in the company’s storage facility to call, and she arranged to ship the prints to me. I was able to spend weeks in front of a Steenbeck in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, wallowing in strange, beautiful images and sounds. Nearly all the illustrations in my book, Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, were taken from those prints.

That same spirit of cooperation with academic film studies has lived on. David and I are grateful for our friendly relationship with the Criterion team, who have cooperated in our creation of video-based online examples tied to Film Art: An Introduction. (The examples all come from Janus films; a sample analysis of a clip from Vagabond is available on YouTube.)

The pair’s presentation included a video, The Criterion Collection in 2.5 Minutes. It features over 600 clips from the collection as of September 1, 2012, chosen and edited by Jonathan Keogh, clearly one of the company’s most devoted fans. Although cut too fast too allow the viewer to identify every title (and I must admit, I don’t think I could recognize every single one, even with longer excerpts), it’s an exhilarating paean to great cinema.

The plaudits in the festival’s annual DVD contest were spread, deliberately or not, among many DVD/Blu-ray companies, with none winning more than one award. A number of items that we’ve covered here took home awards: Flicker Alley’s collection of films by the Russian firm in Paris, Albatros, was deemed the best boxed-set of silent films; and Edition Filmmuseum’s set of four Asta Nielsen films shared the award for best rediscovery. Our friends at the Belgian Cinematek won best Blu-ray boxed set for the “Henri Storck Collection.” Criterion took home best Blu-ray for its edition of Paul Fejos’s Lonesome. For these and the other winners of this year’s DVD awards, see Jonathan Rosenbaum’s website. (As one of the jurors, he explains the changes in the award categories this year.)

The Return of Carbon Arcs

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

They came from the remarkable 2006 find of a wealth of films, equipment, posters, and even sets and puppets, in a warehouse in Belgium. The collection all originated from the stock of the traveling Théâtre Morieux, which had started with puppet and magic-lantern programs, adding films in 1906. All this material had been in the warehouse for a century and was in good condition.

The projector used for the program was not from 1906, but it was old, and very heavy. I happened to be between films when a truck with a crane delivered the projector and a generator and a team set up the equipment facing a small screen on one side of the courtyard. (At the very top of today’s entry, the crane lowers the projector body onto its platform. Above, festival coordinator Guy Borlée watches as the lamp housing is attached. Bottom, all ready to go and waiting for the sun to set.) The projector was a Prevost, of French manufacture, I would guess from the 1940s.

When 10 pm arrived, it became apparent that the light from buildings near the Cineteca could not be entirely controlled. Shadows of the trees in the courtyard were cast on the screen, with light patches between them. But traveling cinemas no doubt frequently set up in venues where nearby sounds and other distractions abounded, so we all accepted the light pollution as part of the experience.

Perhaps the most memorable of the films was Cambrioleurs modernes (“Modern Burglars,” director unknown, 1904). In some ways it was rather crude, with the set consisting of two large painted house façades facing each other, angled from the front, and a wall beyond them. The acrobatic burglars arrived over the wall to rob one house, propping a long board against an upper window to use as a chute for sliding furniture and other large objects down.

The action becomes faster and more impressively choreographed as police arrive, also over the wall, and give chase. Soon burglars and comic cops are diving through windows and doors in the two buildings, as well as performing comic acrobatics on the chute. The whole thing, as far as I could tell, was done in a single take, though there might have been some invisible cuts. If it was indeed one shot, it was a most impressive piece of staging and performance.

This ‘n’ that

Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1963 crime/road movie L’Aîné des Ferchaux (based on a minor Georges Simenon novel) is almost impossible to see on the big screen, apparently due to some sort of rights problem that keeps the French distributor from circulating it. (It is available on a region 2 French DVD without subtitles.) The festival managed to show it in the European widescreen thread by borrowing a print from Svenska Filminstitutet, complete with Swedish subtitles. Translations in Italian and English were projected on small screens below the image. I quickly got accustomed to skipping down to the read the third set of subtitles. It’s certainly not one of Melville’s masterpieces, but it’s definitely worth seeing.

The basic premise is that an unscrupulous banker, Dieudonné Ferchaux (veteran French star Charles Vanel), flees arrest by flying from Paris to New York and then setting out toward the South via car. Michel Maudet, an unsuccessful young boxer (Jean-Paul Belmondo), also unscrupulous but so far with no apparent serious crimes to his name, goes along as his secretary. Although the two seem to like each other, Michel becomes increasingly tempted to steal the suitcase stuffed with cash that Ferchaux has picked up in New York, while Ferchaux seems to lose interest in visiting various other places where he has stashed away large sums. The gradual switch in their power relationship furnishes one main line of interest.

The film is also remarkable in that the two stars did not go to the U.S.A. to appear in the considerable amount of landscape footage shot there by a second unit. Instead, they worked in interior sets in France, as well as exteriors that pass for America. Melville managed to stitch these two kinds of footage into a reasonably convincing depiction of an American road trip.

Another film that has long been hard to see outside Italy, at least in its original form, is Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948), two contrasting short tales displaying the acting talent of Anna Magnani. The first, Une voca umana, is based on Jean Cocteau’s  much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

The longer second part, Il Miracolo, is more engaging and original. It is based on an idea by Fellini and a script by Tullio Pinelli and Rossellini. A feeble-minded homeless woman, Nannina, who is tending a herd of goats near a small Italian village, meets a traveler (played by Fellini, left) whom she, being very pious, assumes to be St. Joseph. He offers her wine and, when she falls asleep, rapes her. Learning that she is pregnant, and not realizing what the traveler did, Nannina becomes convinced that she is carrying the baby Jesus. She is teased and hounded by the townspeople. This part of the film led to censorship problems, not because of the sexual content (the rape is simply skipped over and merely implied) but because of the apparent parody of the Immaculate Conception. (This, too, has been available in a mediocre copy without subtitles on an Italian DVD.)

Apart from its innate interest, L’Amore is historically important for the “Miracle Decision” in the U.S., where it was banned for sacrilege. The Supreme Court decision in the case led to the extension of first-amendment protection to cinema.

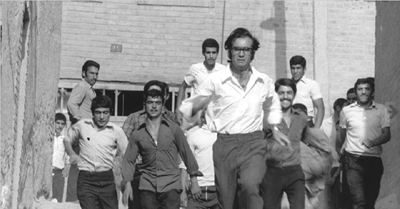

Il Cinema Ritrovato has become a venue for the exhibition of the latest restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation. This organization restores films from countries whose archives do not have the means to do such work. Since 2007, the foundation has preserved on average three films a year. This year the items on show at Bologna included Filipino director Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975, also known as Manila in the Claws of Neon). I had never seen a Brocka film (it’s discussed in a passage of Film History: An Introduction, for which David was responsible), but I was impressed by this one, widely considered to be his best.

It follows a naive young man from the countryside whose girlfriend has become the victim of sex-trafficking; he seeks her in Manila and experiences unfair wage practices and other forms of corruption. Brocka managed to blend seamlessly an absorbing narrative with sympathetic characters and an undercurrent of bitter social critique. Remarkably, Brocka also shot a 22-minute making-of documentary, quite similar to modern DVD supplements, that explains how he created realistic scenes of construction work with a small budget and shooting on location with non-professionals.

Another World Cinema Foundation restoration shown this year is the 1971 classic, Ragbar (Downfall, directed by Bahram Bayzaie). Given the extraordinary burst of creativity that has occurred in Iranian filmmaking since the 1980s, I had high hopes for this. In some ways it resembles more recent classics, most notably in its setting in a school.

The hero is a misfit who has come to teach at the school and becomes the victim of pranks and taunts by his unruly students. A rumor gets started that he is in love with the older sister of one of the students, and in attempting to scotch the rumor, he falls in love with her. Gradually he comes to understand his students and gain their respect. The film is entertaining, though the slim plot seems dragged out too long. The approach is more like commercial mainstream art cinema than like more recent Iranian films. Culturally it is quite interesting, showing some of the customs of the era shortly before the overthrow of the Shah. Most notably the women wear western-style clothes, and some are unveiled.

Unfortunately I had to miss a third Foundation restoration, Ousmene Sembène’s early short Borom Sarret (1969).

The World Cinema Foundation screenings are among the high points of Ritrovato, and I look forward to seeing more of them in years to come. Among all the festival’s restorations of well-known classics (this year Hiroshima mon amour, Richard III, and so on), it was a pleasure to see as well some well-known but hitherto difficult to see films. I hope all three, plus Brocka’s making-of, are included in a future WCF DVD set. (The first set was issued last year and is available from amazon.fr.)

Finally, I managed to see a few of the films in the “War Is Near: 1938-1939” thread. One was a program of three of Humphrey Jennings’ less familiar documentaries, all from 1939: Spare Time, about how working-class people spend their leisure time; The First Days, on the preparations for war in England after its declaration; and S. S. Ionian, on a cargo ship paying visits to ports of call in the Mediterranean. The first two had the true Jennings touch, looking at everyday events with a fresh, unpretentiously poetic viewpoint. The third was more conventional, aimed at presenting information about the importance of non-military shipping for the war effort. All three films, along with a dozen others, are available on the first volume in the BFI’s region-free DVD edition of Jennings’ complete films.

I also saw Edmond T. Gréville’s Menaces (1940). Its story of impending war is what David would call a network narrative, set among the residents of a cheap Parisian hotel–a sort of low-rent version of Grand Hotel. Although most of the stories are not directly about the war, its threat hovers over them all. Perhaps the stand-out is Prof. Hoffman, a disfigured emigré German war veteran (Erich von Stroheim) who gradually realizes that once war breaks out, he will be an enemy alien in the country he considers home. (The film is available on a region 2, unsubtitled French DVD.)

Menaces was the last film I saw at this year’s festival, and now I look forward to being able to report in tandem with David at next year’s!

Once more we thank the Ritrovato team (especially Marcella Natale), led by Peter von Bagh, Guy Borlée,and Gian Luca Farinelli, for their visionary achievements. They have changed our conception of what a film festival can be, and they have led us to a deeper and wider appreciation of the glories of cinema.

[July 19: Thanks to Antti Alanen for pointing out that Saul and Jonathan Turell’s name has only one r. It’s spelled indiscriminately all over the internet with one r or two, so thanks also to Brian Carmody of Criterion for confirming that Turell is correct.]

[July 29: Guy Borlée has kindly sent me links for some of the festival events that have gone online at Vimeo since I posted this entry. There’s a set of all the lectures given during the week, including the Peter Becker and Jonathan Turell presentation on the Criterion Collection that I describe above (direct link to the Criterion session here). I mentioned Kevin Brownlow’s introduction to The Iron Mask, but he did a whole presentation on Allan Dwan as well. You can also watch the DVD awards ceremony.]

Albatros soars

Gribiche (1925).

Kristin here:

Lazare Meerson was one of the great set designers of the late silent period and into the 1930s. His name may not immediately ring a bell, but he designed the great French films of René Clair (La Proie du vent, An Italian Straw Hat, Les deux timides, Sous les toits de Paris, Le Million, À nous la liberté, and La Quatorze Juilliet) and Jacques Feyder (Gribiche [above], Carmen, Les Nouveaux Messieurs, Le Grand Jeu, Pensions Mimosas, and La Kermesse héroïque). He crossed paths with most of the major French Impressionist directors, sometimes in their post-Impressionist periods: Marcel L’Herbier (Feu Mathias Pascal, his masterpiece L’Argent, Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, and Le parfum de la dame en soi), Jean Epstein ( Les Aventures de Robert Macaire), and Abel Gance (Le fin du monde and Poliche). His credits include work with such French directors as Maurice Tourneur, Julien Duvivier, and Claude Autant-Lara.

Meerson was born in Russia and fled the Revolution. Making his way via Germany to Paris, he became the assistant to set designer Alberto Cavalcanti on Feu Mathias Pascal. That’s one of the five French films on a new Flicker Alley release, “From Moscow to Montreuil: The Russian Émigrés in Paris: 1920-1929.” Meerson’s illustrious career led him to England in the second half of the 1930s, where he designed several notable films, including Paul Czinner’s As You Like It, Clair’s Break the News, and Feyder’s Knight without Armour, as well as the classic The Scarlet Pimpernel. He died in 1938 at the young age of 38. (The best online source on Meerson is R. F. Cousins’ filmography, bibliography, and brief biography.) His influence lives on in the work of his most prominent student, Alexandre Trauner (Le jour se lève, among many others).

I begin with Meerson in order to stress how many important strands of film history come together in this very ambitious Flicker Alley set. It allows us to trace Meerson’s early years, from his first apprentice work, Feu Mathias Pascal, to his first and third projects for Feyder. That in itself would be enough to make this release notable, but the Albatros film studio in Paris during the 1920s hosted an amazing collection of talented people working in the cutting-edge styles of the era.

Here we also find three films starring the extraordinary Russian star Ivan Mosjoukine, known to most audiences by reputation only, and then only for the ephemeral Kuleshov experiment that used footage from an old film with Mosjoukine.  This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

We can also appreciate Belgian-born director Jacques Feyder, who had begun his feature-film career with L’Atlantide (1921) and Crainquebille (on our 10-best list for 1922) and then suffered a box-office disappointment with the charming, poignant Visages d’enfants, making two notable films for Albatros. Gribiche contains the first performance by Françoise Rosay, Feyder’s wife, who became one of the grandes dames of French cinema.

Most of all, however, this set makes a big step in showing us what happened after the Revolution to the most important Russian production company, that of Josef Ermolieff. The founder, as Lenny Borger points out in the highly informative booklet accompanying the set, had French connections from the start. Ermolieff “begin his career as a technical assistant at Pathé’s Moscow branch, and by 1912 had moved up through the ranks to become Pathé’s sales agent in Russia. On the verge of the war, he founded his own company and studio and gathered around him a core of artists and technicians who later would become the Russian film colony of Paris.”

The Russian work of the Ermolieff company was revealed to modern audiences in the groundbreaking retrospective of pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema presented at the La Giornate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, Italy in 1989. The flood of hitherto unknown films included great melodramas starring Mosjoukine and other wonderful actors who made their way to Paris in the wake of the Revolution.

Ermolieff initially took his company to Yalta, where in 1918-19, they made several films. The next stop was Constantinople, and finally Paris via Marseilles. Ermolieff purchased the old Pathé studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois and set up filmmaking. The first film entirely produced there, Yakob Protazanov’s L’Angoissante aventure (1920) is not included in the Flicker Alley set. It does survive, however. I remember it as an entertaining film with the added attraction of having a story built around filmmaking. Perhaps someday that, too, can be made available on DVD. In the meantime, the five films in the set show the Russian emigrés gradually merging with the French filmmaking establishment of the day and supporting the work of some of the important Impressionist filmmakers.

Ermolieff himself decided to set up shop in Germany, selling the studio to two of his colleagues, Alexandre Kamenka and Noë Bloch. Renaming the firm Les Film Albatros, they brought it into the mainstream of French cinema.

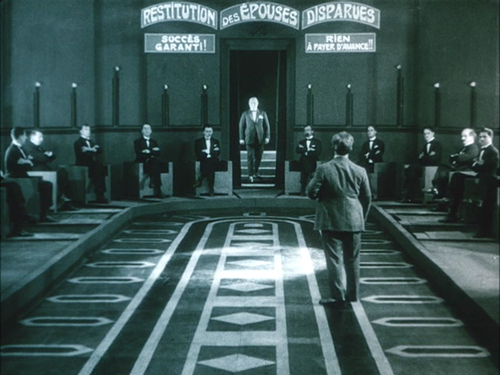

Le brasier ardent (1923)

Mosjoukine directed two films, of which this is the second. It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

Kean (1923)