Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Orpheum descending

State Street, Madison, Wisconsin, 1927.

DB:

When it comes to film culture, Wisconsin yields to no one in weird-assery. I’ve chronicled Mad City Movie Mania on other occasions (here and here), and a current flap has just added to the annals of the addled.

It revolves around Madison’s Orpheum Theatre, a 1927 movie palace that has gone through many incarnations. In recent years it’s become mainly a music venue, but it was also fitted out with a restaurant and still showed the occasional art movie. Until it was shut down last month.

The problem is that after several years of confusion, feuding, moving money around, petty spite, and general dodginess, nobody knows exactly who owns the Orpheum. Is the owner Henry Doane, local restauranteur, who for years was publicly considered the purchaser? Is it Eric Fleming, Doane partner who became anything but silent? Is it Gus Paras, wealthy landlord and restauranteur, who bid a couple of million for it at auction last month? What of the woman who acquired Fleming’s share of the building? And the shadowy figure who made off with a plastic bag holding $175,000—how does he fit in?

“I’ve never done anything to deserve the negative treatment that I’ve been getting. I’m very compromising. I’m willing to do whatever it takes to make things work—as long as it’s profitable.” Eric Fleming

“I’ve gone through every kind of humiliation known to mankind, so I’m kind of immune to it at this point.” By 2007 the partnership had gone so sour that Doane keyed Fleming’s car in broad daylight.

Please visit the story by Steven Elbow at the Capital Times for all the details. My account will be drawing on Elbow’s patient sleuthing, but I also want to recall the glorious, not to mention the inglorious, days of this old house.

Marbles

Orpheum Theatre, 1927. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Designed by Rapp and Rapp, premiere theatre architects, the New Orpheum opened in 1927. (It was initially called that because it superseded the Orpheum, a vaudeville house in another part of town, which was soon renamed the Garrick and specialized in live theatre.) The New Orpheum’s lavish French Renaissance foyer swept up to a staircase leading to the balcony. The auditorium held over 2400 seats, making it the biggest theatre in town until the slightly larger Capitol was built across the street a year later, also by Rapp and Rapp.

The New Orpheum (hereafter, the Orpheum) was one of those picture palaces that aimed to elevate the filmgoing experience while also being a good community citizen. It had a corps of ushers, a smoking lounge, and a reputation for punctilious service. The theatre sponsored community events too. When the local newspaper launched a marbles tournament, the Orpheum held a screening for 2000 kids.

The kids came early and jammed the State street side of the New Orpheum, so it was necessary to call extra policemen to handle the traffic. Once inside the theatre they yelled and applauded the two comedy features which were shown for them, and practically jumped out of their seats during the showing of “Why Sailors Go Wrong.”

Six months before the 1929 stock market crash, the Orpheum was reportedly selling 20,000-25,000 tickets per week, in a town of about 55,000 souls.

An RKO town

View from the Orpheum stage, Halloween, 1930. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

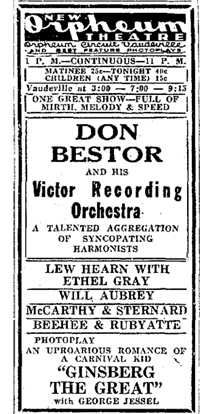

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

Despite the Great Depression, RKO moved quickly to monopolize the Madison movie scene. In 1931, the Parkway (capacity 1100) was acquired by the chain, and soon afterward RKO cut a deal with the Fox Film Corporation to take over the Strand (1400 seats). The swap permitted Fox to dominate Milwaukee in exchange for making Madison an RKO town for first-run films. Of course, in good oligopolistic fashion the RKO theatres showed films from all the studios, as did the second-run houses.

I’ve been unable to determine at what point RKO lost control of its Madison screens. [But see the P. S. below.] Presumably it was after the 1948 divorcement decrees severed Hollywood studios from control of theatres. At some point the Milwaukee entrepreneur Dean Fitzgerald acquired seven local houses, including the Orpheum, under the rubric of the Madison Twentieth Century Theater Corporation.

In 1969, a second screen was carved out of the backstage area of the Orpheum and the minuscule theatre that resulted was called the Stage Door. The contrast with the imposing classic house was startling: the Stage Door was almost certainly the worst theatre in town. Then it declined even more. By the end, with its spidery movable chairs and dank atmosphere, it was reminiscent of the storefront theatres of the nickelodeon era, except that they were surely more comfortable.

Less than heavy traffic

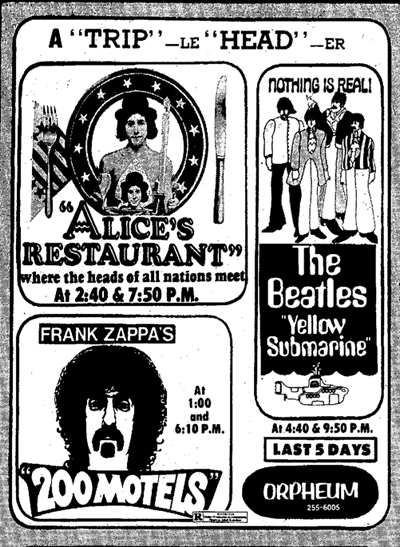

Capital Times advertisement, September 1973.

When Kristin and I came to Madison in 1973, we saw a sort of Sargasso Sea of old movie houses. The Majestic, a decrepit vaudeville house built on a plan as cockeyed as an Escher drawing, was showing X-rated fare, kung-fu, and double-bill repertory. It became a Landmark calendar house. A neighborhood house, the Atwood (aka the Eastwood and the Cinema), built in 1930, screened porn and kiddie shows , though not together. The Esquire also offered sex: arty (The Story of O) or not (Dr. Feelgood, with Harry Reems). The mammoth Strand was still functioning as a first-run house; Star Wars played there for months. The Middleton (seating 500 or so) was designed as a Quonset hut in 1946, and was said to have been built in a week. By our day it was playing second run. The Capitol, where I saw The Exorcist, was still operating too. Every year one theatre or another seemed to run the endlessly popular Eastwood Dollars trilogy.

The mall cinemas were emerging as single-screeners or duplexes. They got the premiere first-run pictures like The Sting, often leaving the downtown houses with lesser items. The most obvious options were counterculture movies and sexploitation.

The Orpheum went along. “Entertainment for the Entire Family!” trumpeted a 1965 Orpheum ad, but by 1969 there were revivals of Bullitt and Bonnie and Clyde. Sometimes classier items like The Godfather would show up in second run, but Orpheum fare in the early seventies was more likely to be Heavy Traffic, Enter the Dragon, The Filthiest Show in Town, revivals of headflix (see above), and a double-bill of Russ Meyer’s Vixen and Up! This was the period when the movie page of the papers included ads for This Is Heaven Sauna Massage, The Rising Sun Counseling Clinic (Adults Only), Photographic Arts Do It Yourself Nude Photography (Camera and Film Supplied), Ms. Brews Lounge (Nude Dancing Daily), and The Dangle strip club.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

Two forces were contending for the property. As part of a plan to revitalize the downtown area, the Madison Idea Foundation proposed putting in an IMAX facility. But preservationists objected that an IMAX setup would wreck the layout of the house. By contrast, restaurant owner Henry Doane (right) favored restoration. He proposed to rehabilitate the old place respectfully and use it for art films, film festivals, and live music. He also wanted to install an upscale café and bar.

Doane won the City Council’s approval and in 1999 he purchased the Orpheum. Throughout the 2000s, thanks to some clever programmers, it played remarkably eclectic fare, from Arnaud Depleschin ‘s A Christmas Tale to Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle (running two weeks, no less). In addition, Doane’s plan to revive the Orpheum as a live music venue, with booze, was finding some success. The grand house that had hosted Gene Krupa, Frank Sinatra, Bob Marley, and Journey now had popular indie bands. When local critic Rob Thomas drew up his list of ten-best shows for the decade, Orpheum concerts took five places. Most memorably, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones played to a packed house the night after the World Trade Tower attacks, highlighted by a version of “God Bless America.”

Drinks plus dining plus music kept the Orpheum doors open, but by the late 2000s the place was obviously not flourishing. There were rumors that distributors, long unpaid, were withholding films. The place was becoming disheveled, with seats broken, that stratospheric ceiling ominously peeling, and the sound system a fog of distortion.

Worse, even though most Madisonians had an affection for the old house, nobody much went there to watch a film. Things had started promisingly: Doane’s introduction to the movie business was the blistering summer of Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace and The Blair Witch Project. But that was an atypical season. During the 2000s, most of the biggest audiences showed up during the Wisconsin Film Festival. It was indeed thrilling to see the place packed out for classics like A Hard Day’s Night (introduced by Roger Ebert) and imports like The Foul King and Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself (both shown in the presence of the directors).

At some point, accommodations were made to favor the concerts: front rows were ripped out to provide dance space.

It became a wretched place to watch movies. Lobby dance parties during screenings could drown out the soundtrack. District 13 was projected within a rectangle framed by a scaffolding erected for an upcoming show. As the decade wore on, you might go to the Orpheum for music, but you didn’t go for the films.

Orpheum vs. Orpheum

Now we know a bit more about what happened behind the scenes in the 2000s. At some point Doane split ownership of the Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison 50-50 with Eric Fleming, a real-estate and restaurant operator.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming’s business style is traced in Elbow’s article. After Fleming became co-owner of the Orpheum, a busted real-estate investment required him to pay creditors $1.5 million. Seeking to dislodge Doane, he created a new company, Orpheum of Madison, claiming that entity as the functioning business arm. He folded that into a package of assets he transferred to Ms. Olesya Kuzmenko for $175,000. “This is what I do for a living,” Fleming explains in Elbow’s article. “I create things and I sell them.”

Who is Kuzmenko, who wound up with a mammoth downtown theatre for the price of a small house on the outskirts of town? She is believed to be Fleming’s girlfriend, but beyond that little is known. She is listed on a license application as President, Vice-President, Secretary, Treasurer, Director, and sole stockholder in Orpheum of Madison. A few years before, Fleming had sold Crave to Christina Bishop, his secretary and girlfriend at the time, under the rubric of a new company Evarc (Crave spelled backward).

There were some curious incidents over these years. There were three fires at the Orpheum, at least two considered by the police to be arson. So far no arrests have been made in the cases. There was also reportedly a break-in, during which a computer was stolen. Perhaps the strangest incident involves the fate of Kuzmenko’s payment. Elbow’s article reports Fleming’s account:

He withdrew the $175,000 he got from Kuzmenko in $100 bills from his bank account, put the cash in a plastic bag and handed it over to a guy identified in court records as Marcus DaMarko, and never saw it again.

“I loaned somebody money,” says Fleming. “I loaned him some money to invest in something. I haven’t talked to him since so I don’t have the money currently.”

So, a reporter asks, you were taken?

“Essentially.”

One more for the road

Because of these maneuvers, Fleming has been running the Orpheum for over a year without input from Doane. The newest issue involves alcohol.

Wisconsin, you must understand, has a frenzied drinking culture. We lead the nation in binge drinking, drinkers per capita, heavy drinkers per capita, and drunk driving. Madison’s main downtown artery, State Street, is packed with bars and restaurants, and the UW’s reputation as a party school attracts an endless supply of youths eager to get wasted. Consequently, what state law calls “alcohol beverages” have been central to the revival of the Orpheum. To establish the lobby restaurant (above) Doane needed to serve beer, wine, and spirits. And Fleming’s cash flow in recent years has been boosted by numerous weddings, which demand booze.

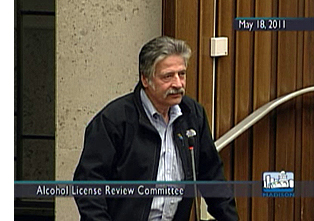

But over the years, the Orpheum’s state vendor’s permit and its liquor license have become problematic. Just during the fall of 2006, the venue under Fleming’s management accumulated some 200 points of alcohol-related violations, and there was a demand that its license be suspended. Across the spring months of 2011, things became more dramatic.

In a series of appeals to the Alcohol License Review Committee of the Common Council, Fleming began to press for the Orpheum’s liquor license to be transferred to his company, Orpheum of Madison. He assured the ALRC that Doane’s original company, Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison, would be evicted from the premises. Doane replied he knew nothing about this, and indeed he was not evicted. Moreover, he argued that Fleming was making purchases for his own company but billing their original one. And Fleming, he claimed, had changed the door locks. The ALRC, declining to step into the middle of the feud, decided to let Doane’s original company hold the license until ownership was clarified.

Auction fever

That fracas took place a year ago, but things really got going this spring. While Doane was suing Fleming to regain control of the building, the Orpheum faced foreclosure because of unpaid bills. In April it went on the auction block.

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Gus Paras had had many dealings with Fleming when both sought to buy property in the area. Now Paras wanted the Orpheum as well. But when the property went to auction, along with the 300 block that had also been part of the Fleming/ Kuzmenko package, Olesya Kuzmenko showed up and began bidding against Paras. In a scene reminiscent of the auction in North By Northwest, she bid the price for the Orpheum up to $1.9 million, but Paras won it for $2.25 million. She bid again on the 300 block properties, but Paras bid her up and then folded, leaving her stuck with her $2.25 million bid. But she couldn’t make the down payment, so the court gave both the Orpheum and the 300 block to Paras for $1.9 million each. However, as of this writing, the sale has not yet been consummated. A court will need to determine who actually owns the building.

In the meantime new alcohol problems resurfaced. Doane requested that the Orpheum’s state seller’s permit not be reactivated. It expired. But the Orpheum continued to sell booze. For a time it seemed that every drink poured since April 2011 had been in violation. A June 2012 story explained:

[Assistant City Attorney Jennifer] Zilavy said the Orpheum should not have served alcohol at concerts and other events. She isn’t sure if the city will pursue civil charges, which could result in a $1,000 fine for each infraction, or refer the matter for criminal charges, which could result in a fine of up to $10,000 or nine months in jail per offense.

As a result, last month the Common Council of the city declined to renew the Orpheum’s liquor license. When the police tried to serve notice of non-renewal, they were unable to rouse anyone. “It is locked up, lights out, nobody there,” reported the officer. Now, however, it seems that Fleming managed to re-activate the license fairly soon after Doane deactivated it, so it’s unclear how long, if at all, the Orpheum was serving drinks illegally.

The city later discovered that Fleming, nothing if not tenacious, was at some point granted a state seller’s permit for his new company. But as of early July the sort-of-partners remained at loggerheads. Doane’s company had a liquor license but no seller’s permit. Fleming’s company now has a seller’s permit but no liquor license. And Doane’s company’s liquor license expired last Saturday. The Madison Common Council has sent the matter to the ALRC for a public hearing. possibly as soon as next week.

I wish I could answer every question that’s come up. Who is Mr. DaMarko, and what became of the 1750 $100 bills? If Paras finally acquires the building, what status does Fleming’s operation have with respect to it? What about Doane’s stake in the theatre he originally bought?

One thing seems certain: If the old place resumes operations, it will be as a venue for weddings and live music, with a bar and perhaps a café. As movies evicted vaudeville from the Orpheum in the 1930s, so now live performance has replaced movies. The drama and comedy have moved off the screen into the streets, the Common Council, and the halls of justice.

Steven Elbow follows up his main story here. If anything develops, he will probably report on it in his blog.

The Orpheum website reflects the chaotic state of its circumstances. Videos of the ALRC hearings, from which my three portraits of the protagonists are taken, may be streamed here and here. In late June, Eric Fleming conducted a brief video tour of the Orpheum’s restorations. The most recent application from Kuzmenko’s company requests that the liquor license begin on 1 July 2012 and end on 30 June 2012. Will the fun never stop?

Some accounts date the Orpheum from 1926, but it opened in March 1927. (See, for example, “New Orpheum’s First Birthday Cake,” The Capital Times, 3 April 1928, 3.) To view more magnificent Orpheum photos from the Wisconsin Historical Society collection, go here. The color shot of the Lobby Restaurant is from the Onion. (The Onion originated–where else?–in Madison.) The color shot of the missing front rows is from the 2010 Wisconsin Film Festival. For a sense of what a wedding looks like in the Orpheum, go to Valo Photography.

Wisconsin’s mad flight from sobriety is documented in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel‘s award-winning series. As far as I know, nothing much has changed since that 2008 survey.

This has been my Year of Living Exhibitionistically; see the Pandora posts and the e-book for accounts of different movie theatres. Older entries are here and here.

P.S. 15 July 2012: Douglas Gomery writes that RKO probably lost its grip on the Orpheum and other theatres much earlier than I speculated:

The Film Daily Yearbook of 1931 lists RKO holdings in Wisconsin: Madison, the Capitol & Orpheum; Milwaukee, the Riverside; and Racine, the Downtown (literally). In 1932 RKO goes into bankruptcy, and all its Wisconsin holdings disappear from FDY. My guess is that the Orpheum and other houses became locally owned.

Douglas wrote the definitive book on American exhibition, Shared Pleasures, and I thank him for the correction.

P.P.S. 16 July: My original post indicated that Kuzmenko won the Orpheum temporarily before she proved unable to make the down payment. Steve Elbow corrected my claim on this: what she acquired at auction was actually the 300 block property, which had been folded with the Orpheum into the overall property Fleming sold her for $175,000. Gus Paras bid successfully on the Orpheum itself.

The blog has been revised to reflect another piece of information Steve provided me: that Fleming may have reactivated the Orpheum’s liquor license quite soon after Doane deactivated it. Thanks to Steve for these corrections.

P.P.P.S. 27 May 2013: A query from Laura Ursin has led me to correct the date in the caption of the top photo, which I had dated from 1938.

The Orpheum Theatre under construction, 1926. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Octave’s hop: Andrew Sarris

La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939).

DB here:

The death of Andrew Sarris last week isn’t just a saddening moment for those of us who admire exhilarating film criticism. It also reminds us how much American culture can owe to a single person.

Everyone who writes about Sarris writes about how they came to know his work. It was that powerful, and if it hit you young, you were never the same. (You never hear about the sixty-year-old who suddenly becomes an auteurist.) The period of his greatest impact was the 1960s-1970s when, to borrow a phrase from Dave Kehr, movies mattered. But his influence has lingered, powerfully, a lot longer.

I think that the best way to honor Sarris is to take his ideas–not just his opinions, but his ideas–seriously, so that’s what I’ve tried to do in this tribute. First, though, some comments that are obligatory in any discussion of Sarris.

Obligatory autobiography 1

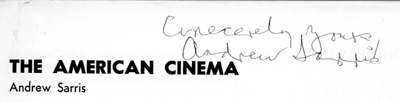

1963: When I was sixteen I wrote to various film magazines and asked for sample issues as a “prospective subscriber.” Surprisingly, several answered, and I amassed a few copies of Film Quarterly, Films and Filming, and Movie. No gift from the land of film journals was more propitious than that fateful issue 28 of Film Culture entitled “American Directors.” It was the first draft of what would become Sarris’ 1968 book, The American Cinema.

Issue 28 was a dangerous item to give a kid. It contained what Georgie Minafer calls “touchy chemicals.” At first I was baffled. There were those famous categories: How to distinguish “Lightly Likeable” from “Less Than Meets the Eye”? Who were Budd Boetticher, Tay Garnett, and John M. Stahl? What did it mean to say that Robert Montgomery “executed a charming champ-contre-champ joke in Once More, My Darling”? To me it was all Expressive Esoterica. Here was a cave of mysteries, but it hinted at treasures.

Sarris’s filmographies were packed with titles I’d never heard of. How could I catch up? Around 1955, the studios had begun selling their pre-1948 titles to local television stations. By the next year, people living in major cities could tune in five or six movies a day. At the forefront of TV sales was the financially precarious RKO, which sold over seven hundred titles to an outfit called C & C. C & C packaged the library as 16mm TV prints under the rubric of “Movietime.”

Sarris’s filmographies were packed with titles I’d never heard of. How could I catch up? Around 1955, the studios had begun selling their pre-1948 titles to local television stations. By the next year, people living in major cities could tune in five or six movies a day. At the forefront of TV sales was the financially precarious RKO, which sold over seven hundred titles to an outfit called C & C. C & C packaged the library as 16mm TV prints under the rubric of “Movietime.”

Auteurism owes a good deal to the 1950s-1960s equivalent of home video, the thousands of 16mm prints floating around local TV stations. In Manhattan, WOR-TV screened their films under the rubric “Million Dollar Movie.” The same film might run once or twice every night for a week (and twice or more on weekends). Without benefit of WOR or New York’s revival houses, I was still able to use Rochester television to sample some of the titles that Sarris had listed, especially those given in big caps. (Italicizing must-see items didn’t show up until the book version.) Sarris’s essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” was published in Film Culture in 1956, the same year that the RKO library began to be syndicated and Kane was reissued in theatres around the country.

I did wind up subscribing to Film Culture. It was the least I could do to pay them back.

Obligatory autobiography 2

Fall 1965: At a state college up the Hudson, the English department hosted a debate on contemporary American movies. The adversaries were Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, both just coming into the national spotlight. One freshman came early and sat with comic earnestness in the front row, a spot he would fetishize later.

Kael was witty and acerbic, tossing off judgments with a wave of her cigarette holder. The Cincinnati Kid was the best of the current crop; Jewison showed great promise. She was riding high because I Lost It at the Movies had come out that spring and was greeted with hosannas. The New Yorker review contrasted her with “the far-out Sarris.”

He didn’t look so far-out. In a crumpled suit, he was resolutely uncharismatic, looking mildly unhappy to be dragged blinking out of the Thalia and shipped upstate. He talked fast, interrupted himself, and, finding few recent movies to praise, celebrated Max Ophuls and Jean Renoir. He delivered enigmatic observations like, “All movies should probably be in color.”

At evening’s end, I knew which camp I belonged in. I got an appropriately nerdy autograph for my Film Culture issue: “Cinecerely yours, Andrew Sarris.” More important, I exulted in a sense that my almost grim obsession with movies had been validated. Not for some time would I realize that I had enlisted, to put it melodramatically, in a fight for American film culture. The battle lines were drawn more sharply in Manhattan than in Albany, but everywhere one thing was clear. Kael was clearly the standard bearer for them, and Sarris was ours.

Obligatory comparison: S vs. K

Who were the them? They were the hip intellectuals who enjoyed a night at the movies. At faculty parties throughout the 1970s I had to check myself when professors of lit or law asked me if I didn’t find Kael’s review that week intoxicating. And she writes so well! As chief New Yorker critic, Kael became the grand tastemaker, a person even filmmakers courted. But who would try to curry favor with the guy who wrote for the Village Voice? It reminds you of the joke about the starlet so dumb she slept with the screenwriter.

Of course like all acolytes we overplayed the differences. Both Kael and Sarris loved classic studio cinema, the performers and scripts as much as the directorial handling. Both critics bemoaned Soviet montage and what they saw as its descendant, the overbusy technique of the 1960s. Both deplored stylistic aggressiveness (the Tony Richardson Syndrome) and both idolized Renoir. Both loved lyricism.

According to us, though, Kael wrote for those who dug movies, while Sarris wrote for those who loved cinema—the medium itself, or rather an exalted idea of the medium’s potential, an ideal form of expression at once dramatic, poetic, pictorial, and musical. He saw each film as bearing witness to the promise of what cinema might be, and he looked in even the tawdriest products for something approximating his dreams. Despite his enthusiasms, he tried for detachment, viewing the latest movie from some unpredictable historical perspective.

Kael famously declared that she watched a new film only once, because that was the way her readers would consume it. But who, we thought, would want to write about a movie after seeing it only once? Mightn’t it reveal some strengths or weaknesses on a second viewing? If it was a good movie, who wouldn’t want to see it more than once? In that same freshman semester, when there were still first-run double features, I sat through The Glory Guys twice in order to watch Help! three times. And that wasn’t even a particularly good movie.

Kael pounced on faults, Sarris savored beauties. Kael made each weak film seem like a blow to her intelligence. Sarris, although he could be harsh, tended to forgive. He taught that it was better to leave a door open than to write someone off—even Bergman, whom some of us would never learn to like until Persona, some not until Fanny and Alexander. Sarris subordinated his personality to that of the movie and its director, which made him seem less fiery than his uptown counterpart; but his attitude suited our own somewhat adolescent amorphousness of character. The arrogant certainty of our tastes was, paradoxically, born of a passionate humility, a sense of serving wise masters named Dreyer, Murnau, Mizoguchi.

Rethinking film history

Sarris is known primarily as the man who gave us the American version of auteurism, or what he called “the auteur theory.” It wasn’t a theory of cinema as such, but rather a heuristic approach to criticism: tips on what to think about and look for when you wanted to plumb a movie’s artistry. But initially, auteurism claimed to be a theory of something else. The opening chapter of The American Cinema is called “Toward a Theory of Film History.”

In Sarris’s day, most people writing about the history of film as an art accepted a notion of technical progress. According to this view, filmmakers became significant by contributing toward the development of the medium. Editing emerged through the efforts of Méliès, Porter, and Griffith, followed by the Russian Montage directors. Various national schools revealed more possibilities of the medium: fantasy and abstraction with the German Expressionists, derangement of sense with the Surrealists.

When sound arrived, a few directors (Clair, Mamoulian, Hitchcock) explored the stylized possibilities of that new technology. But many historians, considering that cinema was inherently a visual medium, declared sound an unwanted intrusion. Clearly, the great days of cinematic artistry were over. Most synoptic histories of the period fell silent about the evolution of technique after the 1920s and concentrate on the emergence of certain genres, such as the musical and the film of social comment.

Even André Bazin could be said to accept the premises of step-by-step artistic progress. Bazin showed that sound cinema wasn’t a dead end, that new artistic possibilities were exploited in the 1930s and 1940s. These were mostly creative alternatives to editing-based technique: the long take, extended camera movement, deep-space staging, and deep-focus cinematography. Bazin claimed that these techniques were most fully on display in the works of Renoir, Wyler, Welles, and some Neorealists.

Sarris was deeply influenced by Bazin’s ideas, but he didn’t accept the conception of film history as an accumulated technical evolution. Sarris called this the “pyramid fallacy,” with each filmmaker adding his slab to the rising and narrowing edifice of cinema. Instead, he proposed thinking of film history as an inverted pyramid, “opening outward to accommodate the unpredictable range and diversity of individual directors.”

In practice this demands that the historian survey entire careers, especially the works of ripe old age. It demands that the historian plot directors’ creative trajectories as paralleling and intersecting and overlapping—perhaps coalescing into broader trends, perhaps creating dead ends. The cinematic universe expands with each new film made, every old film rediscovered or simply re-seen. Auteurism “places a premium on having seen every work by a director who is deemed worthy of a study in depth; and by the time all the cross-references have been pursued in every possible direction auteurism seems to insist that every film ever made is relevant to the inquiry.”

Film history becomes less a linear progress toward something than a vast network of affinities and differences. This idea naturally led Sarris the writer not to the mammoth survey but to multifaceted essay collections. His big book, “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet,” looks like a panoramic history but is in fact a free-range miscellany, a sort of unbuttoned late-career redo of that Film Culture issue..

You can argue that Sarris was proposing a non-historical history, one that dispenses with concepts of influence and cause and that pulverizes any coherent narrative. That seems to me a valid objection. Despite its claim to be a theory of film history, Sarris’s auteurism strikes me as a historically informed approach to film criticism. The ultimate aim isn’t a convincing historical narrative but a compelling aesthetic judgment. Sarris’s idea of expanding filiation, infinite comparison and contrast, allows him to pursue what matters: evaluation.

In this respect at least, he’s agreeing with his predecessors, the writers who saw history as linear progress. But his criteria of value are different. For the traditionalists, the filmmakers who grasped the next step that the medium should take in its creative development become the best. For Sarris, the best filmmakers used the resources at their disposal to create valuable works that also displayed a distinct conception of human life. “Griffith, Murnau, and Eisenstein had different visions of the world, and their technical ‘contributions’ can never be divorced from their personalities.” Innovation was secondary to expression, and expression could best be gauged by tracking the wayward currents of the history of film style.

Auteur, yes; but of what?

New York Film Festival 1966: Pier Paolo Pasolini, translator, Andrew Sarris, and Agnes Varda. Photo by Elliott Landy. From Film Culture no. 42 (Fall 1966).

The auteur “theory” creates a decentralized and dispersed conception of film history—not a tree with a solid trunk and clear-cut branches but a bristling, tangled bush. The historian will dissolve big changes and broad trends into the doings of particular film artists. Who are these artists? Well, obviously, directors.

This move shouldn’t have been controversial. Critics had long assigned primary creative responsibility to directors. In the 1910s Louis Delluc heaped praise on DeMille and Sjöström, while Griffith was acknowledged around the world as a great innovator. Later von Stroheim, von Sternberg, Eisenstein, Pabst, Clair, Welles, Hitchcock, Maya Deren, and many other filmmakers were recognized as the artistic authority behind their work. In the early 1950s, foreign-language filmmakers such as Kurosawa and Bergman were identified (and even promoted by their distributors) as all-powerful creators saying something through their art.

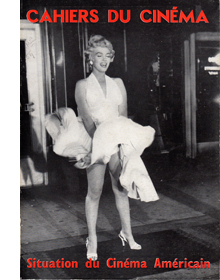

Sarris’s real innovation was, along with the critics around Cahiers du cinéma and Movie, to transfer the idea of the expressive film artist from the headier regions of art cinema to the jostling, compromised world of Hollywood. There were obvious objections.

*Filmmaking is a “collaborative” activity, so you can’t attribute the final work to a single hand.

Yet in the collaborative medium of opera we speak of a Zeffirelli production as opposed to a Peter Sellars one. Why can’t a film director be a synthesizing artist orchestrating the contributions of many other artists?

*But in opera and other theatre forms, you have a preexisting text, the script or libretto or score. Why isn’t the screenwriter the artist, as Shakespeare or Verdi is?

Because theatrical texts are designed to be instantiated on different occasions, while film scripts are written to be produced only once. The film’s final form includes elements of the script, but that final form, being cinematic, can’t be uniquely specified in verbal language. As we all realize, give the same screenplay to six filmmakers, and you get six different and equally free-standing films.

*Popular film can’t be compared to high art. Artistry demands control, and the novelist, the painter, and even the opera director will exercise complete control over the final work. A Bergman or Antonioni has the cultural clout to dictate every aesthetic effect, but the Hollywood filmmaker works as part of a larger process controlled by others. He is handed a script and shoots it, and not necessarily all of it; second-unit and visual effects staff have their input too. The producer may demand more close-ups. In the classic studio system, the director wouldn’t typically get final cut; the producer would shape the released film. All these conditions constitute barriers to artistic expression. The auteur theory, when applied to Hollywood, is deeply inappropriate.

One answer to this objection is that many directors, including some of the best ones, did have a good deal of control over their work: Hitchcock, Hawks, and others were their own producers and worked on their scripts and oversaw their post-production. Moreover, a director can control choices down the line in sneaky ways, as when Ford shot his films so that they could be assembled in only one way.

Sarris advanced another reply to the control objection. If it owed something to the Cahiers young critics, he articulated and practiced it more keenly than they. He proposed a critical method: Take as many films signed by the director as you can find. Attend to the way they exercise their craft, the way they tell their stories and convey their meanings. Seek out an expressive core that seems distinctive, even unique.

Most directors’ collected works won’t yield this. “Not all directors are auteurs. Indeed, most directors are virtually anonymous.” Only the best directors will display a distinct expressive quality. Hawks and Hitchcock evoke radically different worlds of action and feeling, just as Mozart and Rembrandt can.

Fifteen years after his initial statement on the matter, “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Sarris suggested that the elusive concept of personality was not to be derived from the director’s biography. “I was never all that interested in the clinical ‘personalities’ of directors. . . . A director’s formal utterances (his films) tell us more about his artistic personality than do his informal utterances (his conversation).”

For example, we understand John Ford’s respect for what Sarris calls “codes of conduct” not through the old curmudgeon’s interviews but by confronting the tangible texture of the movies. One of Sarris’s favorite examples occurs in The Searchers. Drinking his coffee, the Ward Bond character glances toward the wife of the household. Then his point of view reveals her stroking the uniform of her husband’s brother, played by John Wayne.

Cut back to Bond as the wife and her brother-in-law meet for a tender farewell. Bond stares off into space, chewing.

“Nothing on earth,” writes Sarris, “would ever force this man to reveal what he had seen. There is a deep, subtle chivalry at work here, and in most of Ford’s films, but it is never obtrusive enough to interfere with the flow of the narrative.” The economy is part of the point. “If it had taken him any longer than three shots and a few seconds to establish this insight into the Bond character, the point would not be worth making.”

In the Hollywood studio context, there was something heroic about the rare director who could surmount all the pressures, filter out all the noise, and shape the impact of his work. “The auteur theory values the personality of the director precisely because of the barriers to its expression.” Like a great Renaissance painter paid by a pope or a duke and pledged to illustrate well-known stories, the Hollywood director working for a studio could occasionally conjure up something powerful and distinctive.

Auteurism, Sarris claimed, is our straightest road to determining a film’s value. The great films, by and large, will be those that evoke distinctive directorial sensibilities. But “by and large” allows for the possibility of excellent movies that we can attribute to other forces—script, stars, source material, the happy intersection of talents. Casablanca, writes Sarris, “is the most decisive exception to the auteur theory.” Sarris loved movies more than he loved his theories.

Compare, contrast, repeat

Sarris’s breakthrough essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” appeared in Film Culture during the 1956 revivals of the film. This detailed explication, published when Sarris was twenty-eight, betrays his grad-school training at a period when the New Criticism reigned. In a single stroke, he pioneered the sort of close reading that would become central to Anglo-American academic film criticism.

I can’t recall any later Sarris essay offering such an intensive analysis of a single film. As he developed his historically-guided critical appraisals, he favored synoptic appreciations of directorial careers. These became the occasions for him to point out interacting directorial personalities that comprise that vast network of cinema.

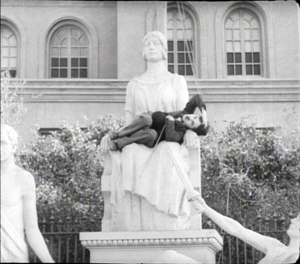

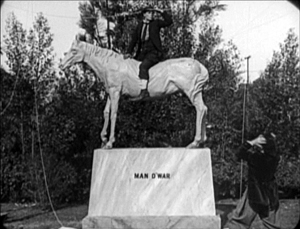

Instead of macro-analysis, Sarris embraced a strategy of “drilling down,” we’d now say, to a single revelatory passage. The chief tactic is comparison, often involving two directors faced with a comparable situation. Both City Lights and The Goat show a protagonist hiding on a statue about to be unveiled. Chaplin seizes the chance to deflate the ceremony.

But Keaton, says Sarris, is less interested in satire; he is “a pessimist in perpetual motion.” In The Goat, “Keaton remains mounted on the clay horse until it begins to sag and crumple under his weight, and the sculptor, a bearded nincompoop in a beret, proceeds to break down and weep.”

“Keaton’s expression here,” Sarris claims, “is mercilessly pragmatic. What good is a clay horse (art?) if you can’t mount it to your own advantage? There is something unabashedly ruthless about Keaton’s comedy, which chills his humor.” This was the period when critics, having just rediscovered Keaton’s films, claimed him as a “metaphysician.” Sarris likened him to Beckett.

Sarris wasn’t alone in turning to detailed commentary at the period; we had Dwight Macdonald’s appreciative 1964 essay on 8 ½ and John Simon’s book-length study of Bergman (1973). But Sarris got there early with the Kane piece, and throughout his career he used analysis to pinpoint authorial personality. Attention to nuanced differences allowed him to create a kind of connoisseurship.

The ultimate expression of this connoisseurship emerges in his concern for privileged moments. A critic has to be alert for shots or gestures or lines of dialogue that encapsulate the emotional tenor of a film and a director’s sensibility. Sarris’ example is a moment in La règle du jeu:

Renoir gallops up the stairs, stops in hoplike uncertainty when his name is called by a coquettish maid, and then, with marvelous post-reflex continuity, resumes his bearishly shambling journey to the heroine’s boudoir.

If I could describe the musical grace note of that momentary suspension, and I can’t, I might be able to provide a more precise definition of the auteur theory. As it is, all I can do is point at the specific beauties of interior meaning on the screen and later catalogue the moments of recognition.

No director but Renoir, Sarris suggests, would have Octave break the scene’s rhythm in exactly this way–and in a manner, Sarris’s bear-metaphor hints, that anticipates Octave’s costume for the climactic party in the chateau. The nonchalant, slightly awkward interruption epitomizes Renoir’s entire style of filmmaking, which has room for casual deflections from neat plotting and groomed performances. The critic’s words can’t wholly capture the force of Octave’s hop, and its resonance for Renoir’s film and his oeuvre. It is, says Sarris, “imbedded in the stuff of cinema.”

Both cinephiles and ordinary viewers are seized by luminous instants that change our skin temperature. We come out of a film satisfied if a few epiphanies have flashed upon us. The critic can signal them but not explain them fully. Interior meaning is the product of craft and personality, but it can’t be reduced to them. It creates a tingling, fugitive beauty that is unique to cinema.

Everyone has his or her own Sarris. The foregoing offers merely bits of mine, and they’re largely academic in slant. That’s because I think that Sarris changed, among other things, the way film history and criticism were taught in American universities. While Kael influenced film journalism, particularly in the upscale markets, Sarris’s legacy is best seen in cinephile criticism (Film Comment, Film Quarterly et al.) and academic film studies. Some Paulettes went to work for the New York cultural weeklies, high and low. Many people who were Sarrisites to some degree (Jeanine Basinger, James Naremore, John Belton, William Paul, Elisabeth Weis, Chuck Wolfe, Mark Langer, Robert Lang, et al.) became professors. Kael’s followers turned out essays, but Sarrisites like Todd McCarthy and Joseph McBride wrote books based firmly in research. Sarris’s version of auteurism has been reworked, in plenty of intriguing ways, in directorial monographs from university presses. He once remarked ruefully that he was an academic among journalists and a journalist among academics, but he managed to bridge the gap adroitly.

Sarris was too far-out for the New Yorker in 1965, and probably for the New Yorker of today. But history, and not just the history of movies, was on his side.

Sarris’ life and death have called forth many eloquent tributes. Among the best are Kent Jones’ career overview, Richard Corliss’s moving memoir, and Jim Emerson’s calm discussion of the excesses of the Sarris vs. Kael dichotomy. See also Ben Kenigsberg’s memories of Sarris’s teaching style.

My quotations are taken from Film Culture no. 28 (Spring 1963), The American Cinema (Dutton, 1968), Confessions of a Cultist: On the Cinema, 1955/1969 (Simon and Schuster, 1971), The Primal Screen (Simon & Schuster, 1973), and The John Ford Movie Mystery (Secker & Warburg, 1976). Thanks also to email conversations with John Belton of Rutgers and Dennis Bingham of Indiana University.

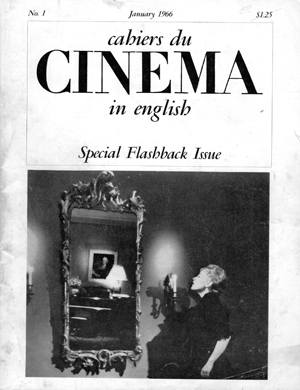

When I received Film Culture no. 28, I didn’t know that it represented a continuation of a Cahiers du cinéma tradition. In December 1955, the journal had published a special issue, “Situation du Cinéma Américain” (no. 54). It included not only critical essays but a “dictionary” of contemporary American directors: small-print filmographies followed by a paragraph of lapidary commentary. (“Lang’s work is founded on a metaphysics of architecture.”) Later issues devoted “dictionaries” to current French cinema (no. 71, May 1957), the Nouvelle Vague (no. 138, December 1962), and more recent American cinema (no. 150-151, December 1963-January 1964). In his American Cinema project, Sarris altered the format significantly by expanding the commentaries into essays and then grouping directors within sharp-edged, highly memorable categories of value. In turn, Sarris’s catalogue seems to have been the model for Martin Scorsese’s “Personal Journey through American Movies.” In the same tradition is Jean-Pierre Coursodon and Pierre Sauvage’s too-little-known American Directors (1983).

When I received Film Culture no. 28, I didn’t know that it represented a continuation of a Cahiers du cinéma tradition. In December 1955, the journal had published a special issue, “Situation du Cinéma Américain” (no. 54). It included not only critical essays but a “dictionary” of contemporary American directors: small-print filmographies followed by a paragraph of lapidary commentary. (“Lang’s work is founded on a metaphysics of architecture.”) Later issues devoted “dictionaries” to current French cinema (no. 71, May 1957), the Nouvelle Vague (no. 138, December 1962), and more recent American cinema (no. 150-151, December 1963-January 1964). In his American Cinema project, Sarris altered the format significantly by expanding the commentaries into essays and then grouping directors within sharp-edged, highly memorable categories of value. In turn, Sarris’s catalogue seems to have been the model for Martin Scorsese’s “Personal Journey through American Movies.” In the same tradition is Jean-Pierre Coursodon and Pierre Sauvage’s too-little-known American Directors (1983).

For more on C & C, which was a soda-pop company, go here. By 1956, WOR-TV was owned by the same company that owned RKO, so it’s no surprise that Kane, King Kong, and other items from the Movietime package played ceaselessly on that station. WOR’s radio station intersected my life from another angle.

For more on the standard version of the history of film art, along with Bazin’s revision of it, see my On the History of Film Style.

The homage volume, Citizen Sarris: American Film Critic, includes many fine pieces, but please don’t read my contribution. Editorial carelessness has mangled it beyond recognition. The version I’ll stand by, “Cinecerity,” is available in my Poetics of Cinema. Portions of this blog entry are lifted from that essay, but I’ve omitted most of my discussion of Sarris’s conception of film style.

New York Film Festival, 1966: Nat Hentoff, Pauline Kael, Parker Tyler, Arthur Knight, Judith Crist, Hollis Alpert, Andrew Sarris. Photo by Elliott Landy. From Film Culture no. 42 (Fall 1966).

PS 24 June 2012: More moving commentary in memoriam at the Film Comment site.

PANDORA’s digital book

DB here:

Looking back at Kristin’s and my ventures online, I see a gradually expanding series of experiments. Step by step, maybe too cautiously, we’ve moved toward what you might call “para-academic” film writing–a way of getting ideas, information, and opinions out to a film-enthusiast readership whom we hadn’t reached with our earlier work. (Although we’re happy when academics take note of what we do.)

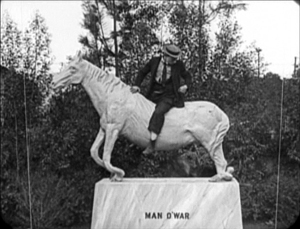

Today we have a new experiment to try. Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies is now available here. Backstory follows.

Baby steps, then longer ones

To take another metaphor, we’ve been gradually exploring various niches in the online ecosystem. At first, back in 2000, knowing almost nothing about cyberculture, I dumped my vitae and a little essay onto my brand-new Geocities site. Later I saw the site mainly as a supplement to print publication, a way to add and correct things I’d written in my books Figures Traced in Light (2004) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (2005), along with material we’d included in our textbooks Film Art and Film History. By then I had retired from teaching.

I started to write more online. I began posting long, stand-alone pieces that I couldn’t imagine any journal or anthology publishing. (They’re in the list on the left-hand column of this page.) Somewhere around 2007, after finishing the collection Poetics of Cinema, I made Web publishing my primary expressive vehicle. So when I was asked to write pieces for various occasions, I tried to secure permission to publish them here as well. They too have wound up in the line-up on the left– a little essay on Paolo Gioli, one on Shaw Brothers’ widescreen cinema, and a liner note about The Mad Detective for the Masters of Cinema DVD line. There are more to come in this vein, including a historical survey of how film theorists have drawn ideas from psychological research.

While moving to fill the essayistic niche, we saw archival and revival opportunities as well. Thanks to Markus Nornes, I was able to republish the out-of-print Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema in a downloadable pdf version, with color illustrations. That’s on the University of Michigan Press site. Vito Adiraensens, who made a pdf of Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment, allowed us to post that on our site.

At this point, whole books we’ve done were available online. But those were straight reprints. The next logical step was to offer a revised edition. After the rights to Planet Hong Kong (2000) reverted to me, I decided to update and expand it and add color illustrations. I also decided to ask for money, making PHK 2.0 the only item on the site that wasn’t free. That was an experiment too, to see if the year I spent reshaping it might yield some payback. It did; so far, the sales have covered the costs of design and yielded me a little for my efforts.

Meanwhile we’ve explored the blog niche. Started in 2006, refreshed once or twice a week, our blog has become greatly satisfying to us. This entry is number 499. We’ve treated the blog wing of the site as a sort of magazine, with each entry as a feature or column or festival report or book notes. We write about anything cinematic, old or new, that interests us. The freedom is exhilarating, and we don’t lack ideas. I have a desk drawer’s worth of folders on topics I want to explore.

Nearly all of these are long-form endeavors. Some run to 6000 words. Even our festival reports, which could have been emitted in a flurry of communiqués, are blended into spacious pieces that permit us to compare films or develop a common theme. At a time when everyone declares that attention spans have shrunk to pinpoints, readers have been very patient with us. People still visit our blog, recommend it to others, and even Facebook and Tweet about it. Roger Ebert has been an especially generous supporter. Thanks to the efforts of Rodney Powell of the University of Chicago Press, we gathered some of our entries into a book, a “real” one called Minding Movies, and I’d hope that the length and contextual depth of the pieces gave them some bookish solidity.

Another niche coming up: As virtual books have found a public, I’ve made a book designed primarily for an e-reader.

Not bloviation, blogiation

Last fall, after realizing the scope of the digital conversion of movie theatres, I decided to write a series of blogs about it. I had no fixed number in mind, but I didn’t expect it to run as long as it did. I kept learning more, so the series, called Pandora’s Digital Box, stretched from December through March. I was encouraged by people who praised it in blogs and on social media. I decided to try to build a book out of the pieces.

Some people think that this is silly. One reviewer of our blog book, Minding Movies, wondered why anyone would buy something that’s available for free. More alert reviewers, like Scott Foundas of Film Comment (May/June 2011), understood that some readers don’t like to read long-form prose online, or don’t like zigzagging through the labyrinth that is our site, or want some guidance in selecting what to pay attention to. Moreover, by gathering items topically, the book suggested recurring themes and an overall frame of reference governing what we do. The broad aims of our enterprise aren’t apparent in a daily skim of each entry.

Still, Minding Movies was a varied mixture. Pandora was from the start a more focused series. And we added no new essays for our collection, but I had quite a bit more to say about the digital conversion. So I cooked up new rules for my latest experiment.

1. The original entries wouldn’t be taken down. As with Minding Movies, the entries will remain available online.

2. The book wouldn’t be simply a blog sandwich. I’ve rewritten, rearranged, and merged entries for smoother reading. The topics are more logically ordered, and the whole thing hangs together organically. The blogs formed a kaleidoscope; the book is a narrative.

3. The book would have lots of new material. It includes things I didn’t know when I wrote the blog, ideas that have come to me since, and as much background and context as I could supply. The original blogs amounted to about 35,000 words (enough for a Kindle single). The finished book runs over 57,000 words.

4. It wouldn’t be an academic book. It’s written in the same conversational tenor as the blog. I try not to make anybody’s head hurt. No footnotes, but….

5. The book would exploit online access. The text is unsullied by links, to promote continuity of reading. But a section of references in the back contains citations and hyperlinks to documents, interviews, sources, and sites of interest. This section tells you where I got my information and, if that information is online, takes you there.

6. The book would have to be for sale… Part of this experiment is to see whether I can make back what I’ve spent on the project. I reckon that my travel to theatres and events like the Art House Convergence in Utah, along with other expenses like paying our Web tsarina Meg to polish up my self-designed Word book, comes to about $1200. In addition, I’d like something for my extra time and effort.

7. …but not cost too much. Planet Hong Kong 2.0 runs $15, which I think is a fair price given the cost of designing a book with hundreds of color pictures. But Pandora is a lot simpler and has only a few stills. So I’m offering it for much less: $3.99.

Another Whatsit, but only $3.99

Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies traces how the digital conversion came about, how it affects different sorts of theatres, how it shapes the tasks of film archives, and what it portends for film culture, especially the culture of moviegoing.

A key concern was trying to go beyond what I’d already written. For one thing, I try to answer questions I didn’t pursue in the blog entries. How did the major distributors orchestrate the transition? How did they reconcile the interests of the various stakeholders—filmmakers, theatre owners, manufacturers? By 2005, the specifications for digital cinema were established, but the real uptake came five to six years later. What led to the delay? How was digital cinema deployed outside the US? And so on.

Second, I provide background and context for areas I surveyed quickly online. For example, instead of sketching how a movie file gets projected, I take you into a booth and we follow the process step by step. The chapter on small-town cinemas reviews the role of single-screen theatres in the industry. The chapter on art-house cinemas goes back to the 1920s and shows remarkable continuity of taste and business tactics up to the present. Throughout, I consider how the US exhibition system has worked since the rise of multiplexes.

Third, there are unexpected tidbits. How did celebrity directors like Lucas, Cameron, and Jackson spearhead the shift to digital and later innovations? (I touched on that in a couple of recent entries here and here, but there’s more in the book.) Who invented multiplexes? Cup holders? When did those annoying preshow displays start, and more important, who controls them? How do distributors decide whether to release a movie wide or to let it “platform”? Why do art-house theatres serve coffee? There are even a couple of jokes (maybe more unintentional ones).

I think it has worked out well. I’ve tested the text on Kindle, Nook, and the iPad, and it fits very snugly. You just have to import it as a pdf from your computer. On the iPad, it seems to work particularly well with the app GoodReader, which permits smooth searches, easy bookmarking, and quick shifts back and forth.

As I mentioned above, you can go here to order the book. On the same page you can examine the Table of Contents and a bit of the Introduction.

It’s possible that some people might want to make a bulk purchase. Pandora might be used in a class, or given to staff members working at a film festival, or presented to members or patrons of an art house. For such worthy purposes, I can make the bulk price quite low. If you’re interested, please write to me at the email address above.

Self-publication is a risk for both author and reader. If you decide to buy the book, I thank you.

The next logical steps? A new ecological niche? A completely original book online, maybe. Or PowerPoint lectures with voice-over. Who knows? As Jack Ryan says at the end of The Hunt for Red October: Welcome to the new world.

Thanks as usual to our Web tsarina Meg Hamel, who did her usual superb job turning Pandora the Blog into Pandora the Book, and who has set up the payment process to be quick and easy. Earlier helpmates were Vera Crowell and Jonathan Frome, whose efforts in creating this site are remembered and appreciated.

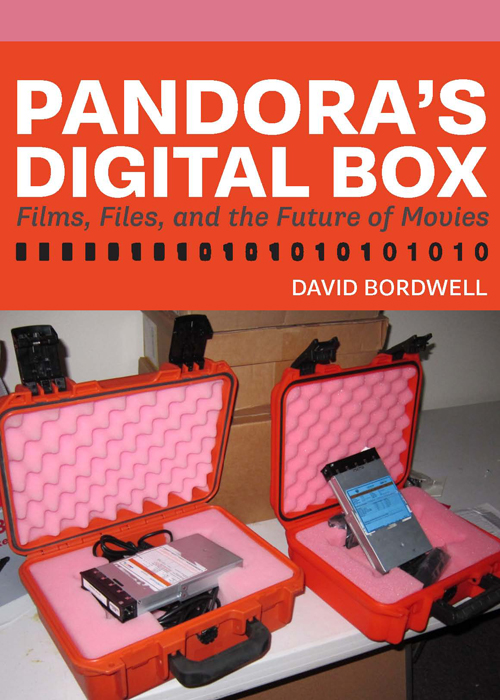

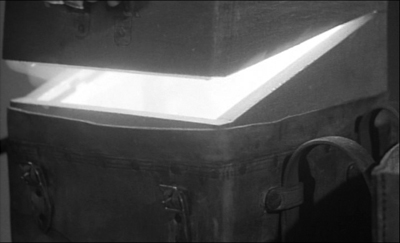

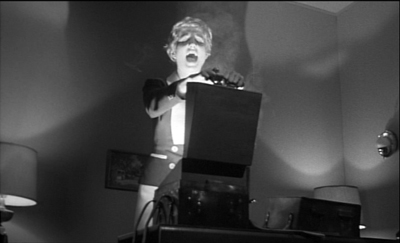

The illustrations are from Kiss Me Deadly and Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, but you knew that. Thanks to Jim Emerson for his suggestions.

The Gearheads

Mourning.

DB here:

At the Wisconsin Film Festival I saw the best film I’ve seen over the last six months. I can’t really say much about it, but I’ll do what I can. My remarks make most sense, I think, if I embark on a pretty long detour.

The frame-rate shuffle

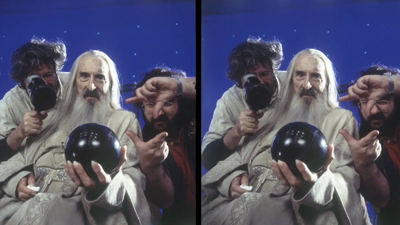

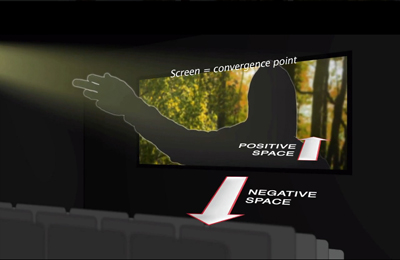

3D still photographs by Peter Jackson taken during the filming of the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In the wake of April’s convention of the National Association of Theater Owners, the biggest press tumult surrounded Peter Jackson’s ten-minute demo from The Hobbit. Fulfilling what James Cameron had called for at the 2011 NATO confab, Jackson has been shooting at 48 frames per second, and the demo was screened at that rate. Cameron and Jackson are concerned that there’s too much image judder and strobing in digital cinema, especially 3D. They propose a higher frame rate to smooth things out.

Opinion on the Hobbit footage was divided. Some theatre owners and operators were happy with it, but others were uneasy. The higher frame rate tends to eliminate motion blur and create a sharpness that recalls, for some viewers, the brittle look of HD sports broadcasts. “It looked to me like a behind-the-scenes featurette,” said one.

Jackson, who has been preparing for this initiative on his Facebook page, defended his decision. He maintains that audiences will adapt to it, just as his production team has. Many exhibitors seem to have dismissed the new initiative as too expensive, particularly at a time when many are still paying off the digital conversion. But the Regal Entertainment Group, the largest cinema chain in the US, announced plans to outfit up to 2700 screens so that The Hobbit can be screened at 48 fps. It now seems possible that The Hobbit may be shown in no fewer than six formats: 2D, 3D, and Imax, and in each there will be both 24 fps and 48 fps presentations.

Not being present to watch the footage, I have to withhold judgment about how it looks. I haven’t though, withheld my opinion about how Cameron and Jackson, along with George Lucas, have used their roles as superstar directors to prod exhibitors to adopt expensive new technology. They acted as the figureheads for the switch to digital in 2005, using 3D as the incentive for exhibitors to convert. A few years later, after proposing 3D television, Cameron upped the ante by urging higher frame rates for film. Jackson has joined him by actually making a film at 48 fps. Cameron has said he prefers 60 fps, which may mean that the goal posts get shifted again when Avatar 2 or something else comes along.

You can go to my earlier post for more thoughts on their tactics. My book on the digital conversion, due out on this site in a few days, offers a fuller account. In the meantime, I’m going to try to understand this frame-rate fracas in a wider historical context.

The palette

Cinema technology has been surprisingly stable, as befits its status as the last surviving nineteenth-century engine of popular entertainment. The dimensions of the film strip, the rate of shooting and showing, and other fundamental factors have altered relatively little. The coming of sound and then the replacement of nitrate-based film by acetate are perhaps the biggest alterations in the basic technology. Below this macro-level, though, innovation has been constant.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, most of the change came in the production sector. The adoption of panchromatic film stock; color processes, principally Technicolor and the monopack systems like Agfacolor and Eastman Color; the development of various lighting units (carbon-arc, incandescent, Xenon); the shift from optical sound recording and reproduction to magnetic processes; the emergence of different sorts of camera support (varieties of tripod, dollies, and cranes, along with handheld devices)—all of these shaped how movies were made but had relatively little effect on how they were shown.

Some 1950s innovations launched in the production sector, notably widescreen cinema, stereophonic sound, and 3D, reshaped exhibition more drastically, because they came at a moment when theatres were anxious to lure back their clientele. Other revampings of exhibition, like wide-gauge film (65mm/70mm) and Cinerama, were never intended to be the universal standard. They were designed for a distribution system that included roadshow exhibition. Dedicated screens showcased big films like The King and I and Lawrence of Arabia for long, well-upholstered runs before the film hit the neighborhoods and the suburbs.

Producers innovate and exhibitors hesitate. Exhibitors must be cautious and conservative; they risk revamping their venue at great cost only to find that the new technology isn’t catching on. The roadshow system repaid exhibitors well, until it collapsed in response to the rise of saturation booking in the 1970s. For similar conservative reasons, exhibitors looked askance at the digital sound reproduction technologies that emerged from the 1970s through the 1990s. At one point, a house had to accommodate four different sound systems, some of them subject to periodic upgrades.

When technologies emerge in the production sector, they mostly promise to enlarge the filmmaker’s palette. A 1950s film could be made black-and-white or color, deep-focus or soft-focus, with arc or incandescents, flat or anamorphic, and so on.

In practice, of course, not everything was possible on every project. Budgets, as ever, limited options, and many directors and DPs disliked shooting in color or CinemaScope but were obliged to do so. And there were some trade-offs. Filmmakers of the 1930s could not shoot on orthochromatic stock, and after the mid-1950s, it was hard to make a film destined for the classic 1.37 Academy ratio. Still, there were few absolutely forced choices, and many directors explored different options from project to project.

The prospect of an enhanced palette is in fact one reason that some filmmakers embraced new technologies. Sergei Eisenstein (who trained as an engineer) was eager to try out sound, color, and even television because they expanded creative choice. Orson Welles saw in the RKO effects department, which had pioneered sophisticated optical-printer work, a way to create images that couldn’t be generated in the camera. As is now widely known, many of Citizen Kane’s most famous “deep-focus” shots were achieved through special effects. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick renewed the power of his images through his eager adoption of new technologies, including long lenses for Paths of Glory, the handheld camera in Dr. Strangelove, faster lenses for Barry Lyndon, and the Steadicam for The Shining. These filmmakers wanted to multiply options, not foreclose them.

Share our fantasy

The changes that Cameron and Jackson propose are more sweeping. Now that digital projection is an accomplished fact, there will be backward pressure to create a wholly digital workflow. Filmmakers who want to shoot on 35mm will be reminded that they will eventually be fiddling with a digital intermediate, and that the final version will be digital, not film-based. A selling point of digital cinema to the creative community was the promise of complete control over the film’s look and sound, so that the audience gets exactly what the filmmaker envisioned. To assure that integrity, the director will have to shoot and finish the project on digital. That will take away an entire dimension of choice—specifically, shooting on film.

The pressure to shoot 3D adds to this. Martin Scorsese and Ang Lee showed up at the same NATO convention to praise the format. Now films that aren’t tentpole items can be made in 3D, they agreed. According to Variety, Scorsese claimed that “2D projection [sic] will eventually go the way of black-and-white—used primarily as a stylistic choice—as auds will soon acclimate to depth even in indie films.” This sounds like a widening-of-the-palette defense, as does his reaction to new frame rates. “You can do anything you want [in post-production] with that image at that level of clarity, can’t you?”

In contrast to Scorsese’s offhand pluralism, Cameron, Jackson, and their confrère Lucas may be creating a scorched-earth policy. Their conception of cinema, I would say, is now largely that of the Gearhead. Their notion of artistry has become quite mechanical, in that they see progress to depend almost wholly on improved hardware (and software).

They represent three mini-generations of Hollywood techno-lover: Lucas, who began in animation; Cameron, who started as a model-builder; and Jackson, the 1980s fanboy who played with King Kong action figures. They are directors who treat cinema as a delivery system for stories grounded in genre conventions. Fantasy is their touchstone, and realism of any sort bears only on how vividly we perceive the images, not what the films show or say or suggest.

Back in 1999, Lucas noted frankly that film was becoming a form of painting, “unfixing the image.”

You have news footage, you have documentary footage—which are supposedly realistic images—and then you have movies, which are completely fantasy images. There’s nothing in a movie that’s true or real—ever . . . . The people in the movie are actors playing parts. The characters are not real. The sets are not real. If you go behind that door you’ll see there’s no building—it’s just a big flat piece of wood. Nothing is real. Not one little tiny minutia of detail is real.

The Hollywood cinema was then putting fantasy and special effects at the center of its aesthetic, and Lucas understood that every film—action picture, romantic comedy, even dramas—would rely on special effects to a new extent.

Here’s Cameron saying the same thing in defending 3D in 2008.

Godard got it exactly backwards. Cinema is not truth 24 times a second, it is lies 24 times a second. Actors are pretending to be people they’re not, in situations and settings which are completely illusory. Day for night, dry for wet, Vancouver for New York, potato shavings for snow. The building is a thin-walled set, the sunlight is a Xenon, and the traffic noise is supplied by the sound designers. It’s all illusion, but the prize goes to those who make the fantasy the most real, the most visceral, the most involving. This sensation of truthfulness is vastly enhanced by the stereoscopic illusion.

It’s hard to believe that Lucas and Cameron don’t know the long tradition of debate in the arts about realism. Realism can be considered a question of subject matter, plot plausibility, random detail, psychological revelation, and many other things; it isn’t just about trompe l’oeil illusion. Moreover, documentary and experimental filmmakers have suggested that cinema can capture moments of unplanned truth. And André Bazin and others have argued that even when presenting fictional tales, photographic cinema gives us unique access to some essential qualities of phenomenal reality. For Bazin, even an awkwardly shot scene could preserve the sensuous surface of things with a conviction that no painterly manipulation can equal—not perfection but brute facticity. Instead, Lucas and Cameron offer a Frank Frazetta notion of realism: glistening, overripe, academically correct rendering of things we’ve seen many times before.

Turnstile dynamics

NATO’s 2005 ShoWest convention: Lucas, Robert Zemeckis, Randal Keiser, Robert Rodriguez, Cameron.

I see a valid place for a cinema of splendor and spectacle, especially in certain genres. There’s nothing wrong with seeking new methods of pictorial representation, as Spielberg did in Jurassic Park, a genuine triumph of veridical realism. Nor am I trashing Lucas and Cameron wholesale; I admire their early films a fair amount. But they’re forcing their conception of cinema on all filmmakers.

Am I being unfair? I don’t think so. When directors say that digital or 3D or 48 fps is the future of cinema, they’re implying wholesale conversion is in the offing. Although Scorsese says that 2D or another frame rate will remain an option, Cameron and Jackson aren’t quite so open-handed. Because they’re convinced that the result is much more immersive, and immersion is always good, the technology should suit every kind of movie. Cameron again:

It is intuitive to the film industry that this immersive quality is perfect for action, fantasy, and animation. What’s less obvious is that the enhanced sense of presence and realism works in all types of scenes, even intimate dramatic moments.

Both directors usually add that they’re not insisting that every film is suited to the new bells and whistles, that it has to suit the plot and so on—the usual boilerplate about the primacy of “story.” “Stereo [imagery] is just another color to paint with,” says Cameron.

But they sound as if not having 3D or 48 fps puts the movie at a disadvantage. Cameron in 2008:

Every time I watch a movie lately, from 300 to Atonement, I think how wonderful it would have been if shot in 3D.

Jackson in 2011:

You get used to this new look [48 fps] very quickly. . . Other film experiences look a little primitive. I saw a new movie in the cinema on Sunday and I kept getting distracted by the juddery panning and blurring. We’re getting spoilt! . . . There’s no doubt in my mind that we’re headed toward movies being shot and projected at higher frame rates.

As happened before, the pronouncements of the directors mesh well with the initiative of the manufacturers. Back in 2005, Cameron, Lucas, Jackson, Robert Rodriguez, and Bob Zemeckis took to the NATO stage to help sell the Digital Cinema Initiatives program to skeptical exhibitors. Their support (and the box-office numbers of the 3D Chicken Little) aided the projector manufacturers Christie, Barco, NEC, and Sony in rolling out units. The number of digital screens in the US and Canada jumped from ninety in 2004 to over 300 at the end of 2005.

This year, with about two-thirds of all US screens fully converted, Christie circulated a promotional leaflet tied to Jackson’s demo. A few years ago, the future was all about 3D, but now, the text states flatly, “The future of cinema is all about high frame rates.” The cards are on the table.

At just 24 FPS, fast panning and sweeping camera movements that are a critical part of any blockbuster are severely limited by the visual artifacts that would result. . . .

The “Soap Opera Effect” has been derisively used to describe film purist perceptions of the cool, sterile visuals they say is [sic] brought on by digital.

But the success of Hollywood, Bollywood and big-budget filmmakers around the world has little to do with moody art-house films. The biggest blockbusters are usually about immersive experiences and escapism—big, vibrant, high-action motion pictures.

The HFR system, then, aims to spiff up franchises and tentpoles, and all other filmmaking must be dragged along and adjust. Although Jackson says he has heard no plans to charge more for 48 fps shows, Christie thinks we would pay for this treat:

Beyond the simple turnstile dynamics of “must-see” movies, a new, higher standard of movie-going should support premium pricing. Managed right, hotly-anticipated 3D HFR should empower ticket up-charges.

By all signs, the churn won’t stop. “Every three months you’re behind,” says Ang Lee. “We’re guinea pigs.” David S. Cohen, technology writer for Variety, believes that 48 fps is a transitional technology and that 60 fps will win out (“but not soon”). He adds: “Bizzers in both TV and movies are going to be making creative and financial decisions about HFR for years—maybe forever.”

Lucas and Cameron, and then Jackson, grasped that if cinema technology went wholly digital, it would change in fundamental ways. It would turn a medium into a platform, like a computer operating system. The most basic technology of showing a movie would become subject to rapid, radical, ceaseless remaking. It would demand versions, upgrades, patches, fixes, tweaks, and new software and hardware indefinitely.