Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Pandora’s digital box: Art house, smart house

The Art Theater, Champaign, Illinois. Photo by Sanford Hess, reproduced with permission.

DB here:

Theatres’ conversion from 35mm film to digital presentation was designed by and for an industry that deals in mass output, saturation releases, and quick turnover. A movie comes out on Friday, fills as many as 4,000 screens around the country, makes most of its money within a month or less, and then shows up on VoD, PPV, DVD, or some other acronym. The ancillary outlets yield much more revenue to the studios, but the theatrical release is crucial in establishing awareness of the film.

Given this shock-and-awe business plan, movies on film stock look wasteful. You make, ship, and store several thousand 35mm prints that will be worthless in a few months. (I’ve seen trash bags stuffed with Harry Potter reels destined for destruction.) Pushing a movie in and out of multiplexes on digital files makes more sense.

After a decade of preparation, digital projection became the dominant mode last year. Today “digital prints” come in on hard drives called Digital Cinema Packages (DCPs) and are loaded (“ingested”) into servers that feed the projector. The DCPs are heavily encrypted and need to be opened with passkeys transmitted by email or phone. The format is 2K projection, more or less to specifications laid down by the Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI) group, a consortium of the major distributors.

Upgrading to a DCI-compliant system can cost $50,000-$100,000 per screen. How to pay for it? If the exhibitor doesn’t buy the equipment outright, it can be purchased through a subsidy called the Virtual Print Fee. The exhibitor can select gear to be supplied by a third party, who collects payment from the major companies and applies it to the cost of the equipment. The fee is paid each time the exhibitor books a title from one of the majors. See my blogs here and here for more background.

It’s comparatively easy for chains like Regal and AMC, which control 12,000 screens (nearly one-third of the US and Canadian total), to make the digital switchover efficiently. Solid capitalization and investment support, economies of scale, and cooperation with manufacturers allow the big chains to afford the upgrade. But what about other kinds of exhibition? I’ve already looked at the bumpy rise of digital on the festival scene. There are also art houses and repertory cinemas, and here one hears some very strong concerns about the changeover. “Art houses are not going to be able to do this,” predicts one participant. “We will lose a lot of little theatres across the country.”

The long, long tail

‘Plexes, whether multi- or mega-, tend to look alike. But art and rep houses have personality, even flair.

One might be a 1930s picture palace saved from the wrecking ball and renovated as a site of local history and a center for the performing arts. Another might be a sagging two-screener from the 1970s spiffed up and offering buns and designer coffees. Another might look like a decaying porn venue or a Cape Cod amateur playhouse (even though it’s in Seattle). The screen might be in a museum auditorium or a campus lecture hall. When an art house is built from scratch, it’s likely to have a gallery atmosphere. Our Madison, Wisconsin Sundance six-screener hangs good art on the walls and provides café food to kids in black bent over their Macs.

Most of these theatres are in urban centers, some are in the suburbs, and a surprising number are rural. Most boast only one or two screens. Most are independent, but a few belong to chains like Landmark and Sundance. Some are privately held and aiming for profit, but many, perhaps most, are not-for-profit, usually owned by a civic group or municipality.

What unites them is what they show. They play films in foreign languages and British English. They show independent US dramas and comedies, documentaries, revivals, and restorations.

In the whole market, art houses are a blip. Figures are hard to come by, but Jack Foley, head of domestic distribution for Focus Features, estimates that there are about 250 core art-house screens. In addition, other venues present art house product on an occasional basis or as part of cultural center programming.

Art house and repertory titles contribute very little to the $9 billion in ticket sales of the domestic theatrical market. Of the 100 top-grossing US theatrical releases in 2011, only six were art-house fare: The King’s Speech, Black Swan, Midnight in Paris, Hanna, The Descendants, and Drive. Taken together, they yielded about $309 million, which is $40 million less than Transformers: Dark of the Moon took in all by itself. And these figures represent grosses; only about half of ticket revenues are passed to the distributor.

More strictly art-house items like Take Shelter, Potiche, Bill Cunningham New York, Senna, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Certified Copy, Page One, The Women on the 6th Floor, and Meek’s Cutoff took in only one to two million dollars each. Other “specialty titles” grossed much less. Miranda July’s The Future attracted about half a million dollars, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives grossed $184,000, and Godard’s Film Socialisme took in less than $35,000. For the distributors, art films retrieve their costs in ancillaries, like DVD and home video, but the theatres don’t have that cushion.

Something else sets the art and rep houses apart from the ‘plexes: The audience. It’s well-educated, comparatively affluent, and above all older. Juliet Goodfriend’s survey of art house operators indicates that only about 13% of patrons are children and high-school and college students. The rest are adults. A third of the total are over sixty-five. As she puts it, “Thank God for the seniors!” However much they like popcorn, they love chocolate-covered almonds.

Almonds aside, how will these venues cope with digital? To find out, I went to Utah.

Harmonic Convergence

Tim League, Alamo Draft House, during his keynote address at the Art House Convergence.

Five years ago, the Sundance Institute founded the Art House Project, a group of theatres that could screen a tour of Sundance Festival films. The original members recognized the advantages of collaborating, and Russ Collins of the Michigan Theatre organized an annual meeting held just before the festival. In its first year, 2008, the Art House Convergence attracted twenty-two people. This year it drew nearly three hundred—not only programmers and operators and major speakers, but delegates from distribution companies, service firms, and equipment manufacturers. To my eye, it’s becoming an informal trade association.

My three and a half days at the Convergence in Midway, Utah filled me with information and energy. Having attended one of the classic art theatres in my youth, the Little Theatre in Rochester, New York, I’ve been a patron in this sector for fifty years. But I never really met the people behind the scenes. This bunch is exuberant and committed to sharing their love of cinema. They want to watch a movie surprise and delight their audiences. Ideally, the customers would so completely trust the programmer’s judgment that they would come to that theatre without knowing what’s playing.

If you wonder where old-fashioned movie showmanship went, look here. These folks mount trivia contests, membership drives, singalongs. They help out with local film festivals. They bring in filmmakers and local experts for Q & A sessions. They screen those plays, operas, ballets, and concerts that attract a broader arts audience. The bigger entities, like the Bryn Mawr Film Institute and the Jacob Burns Film Center, offer courses in filmmaking and appreciation, along with special events for children, teenagers, and other sectors of the community.

Everything is about localism. These people know their customers, often by name. They sense the currents of taste crisscrossing their town. The success of the Alamo Draft House reveals that Austin has a demographic hungry for the kung-fu classic Dreadnaught, an Anchorman quote-along, or a compilation of the worst CGI work in film history. In LA, The Cinefamily attracts a crowd ready to watch Film Socialisme alongside Battle Royale, Pat O’Neill films, and the 1927 Casanova. “Mission” was a word heard often heard in Midway. These people aren’t only about making money but about weaving unusual cinema into the fabric of their town’s culture and subcultures.

The classic art house was mission-driven too, and it could pay a little as well. Before the advent of videotape, you could make decent money showing Ealing comedies, Fellini, and Bergman years after their initial release. Some exhibitors continue as profit-driven businesses. But many, perhaps most, people in the Project operate not-for-profit venues. The cinemas are funded by donations, foundations, and government agencies, such as arts councils. Russ Collins has argued for embracing this trend.

“New model” Art House cinemas are community-based and mission-driven. . . . Most “new model” Art House cinemas are non-profit organizations managed by professionals who are expert in community-based cinema programming, volunteer management and the solicitation of philanthropic support from local cinephiles and community mavens.

Russ points out that over the twentieth century, opera, theatre, and other sectors of the performing arts have moved toward non-profit status. “If it makes sense that if music has a range from very commercial to very subsidized, film should too. There are all kinds of movies, and there should be all kinds of outlets.” The University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque and the Wisconsin Film Festival have shown me that this strategy can work—again, if the programming meshes with the tastes of its community.

There are clouds on the horizon, of course. Gary Palmucci of Kino Lorber recalled a line from Irvin Shapiro, who distributed foreign-language films for fifty years: “When were there ever not problems?”

For example, the baby-boomers, cinephiles since the ‘60s, are likely to be around for ten or fifteen more years. Where will new patrons come from? When I was in college, you scheduled your life around theatres’ showtimes, but younger people have gotten used to time shifting and on-demand access via tape, disc, cable, or the Web. A more worrisome sign: even in art houses near college campuses, students tend to make up a small fraction of the audience. The next few years will tell if changed tastes, along the habit of unbridled access to movies, will keep an aging Gen X from the art house.

More pressing the problem is digital conversion. It was the topic of two information-filled sessions at the Convergence, and it came up often during other panels.

Where do they get those movies?

An AHC panel: Russ Collins, Ira Deutchman (Emerging Pictures), Jeff Lipsky (Adopt Films), and Gary Palmucci (Kino Lorber).

Historically, most major new film technology was introduced in the production sector and resisted in the exhibition sector. Exhibitors have been right to be conservative. Any tinkering with their business, especially if it involves massive conversion of equipment and auditoriums, can be costly. If the technology doesn’t catch on, as 3D didn’t in the 1950s, millions of dollars can be wasted.

Shooting movies on digital was no threat to theatres as long as 35mm prints were the standard for screening. But distribution has long been the most powerful and profitable sector of the film industry. Today’s major film companies—Warners, Paramount, Sony et al.—dominate the market through distribution. So when the Majors established the Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI) standards, exhibitors had to adjust.

Since distributors call the tune, let’s look at the different digital alternatives available.

Mainstream commercial films from the major studios are currently distributed in both 35mm copies and digital copies. But at some point fairly soon, the majors will cease releasing 35mm. Twentieth Century Fox has taken the lead in declaring that at the end of this year it will circulate no more film prints. John Fithian, the plain-spoken President of the National Association of Theatre Owners, said in March of 2011:

Based on our assessment of the roll-out schedule and our conversations with our distribution partners, I believe that film prints could be unavailable as early as the end of 2013. Simply put, if you don’t make the decision to get on the digital train soon, you will be making the decision to get out of the business.

This means that the theatre will require full 2K/4K projection, and the exhibitor will need a DCI-compliant projector and a server for every screen. To pay for the upgrade, many exhibitors will want to take advantage of the Virtual Print Fee. But many VPF programs have set their signup deadlines during this year.

Arthouse films distributed by studio subsidiaries are the tentpoles and blockbusters of the arthouse market. Sony Pictures Classics, Universal Focus, and Fox Searchlight usually furnish the most desirable pictures for these screens. Add in certain titles supplied by “mini-majors” like Relativity, The Weinstein Company, and Lionsgate/ Summit. This season, for instance, art houses would have suffered without Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (Focus), The Descendants (Fox Searchlight), A Dangerous Method and The Skin I Live In (SPC), and The Iron Lady, The Artist, and My Week with Marilyn (Weinstein).

As far as I can determine, all these firms currently supply 35mm prints. Jack Foley of Focus recognizes that film copies remain the default for most art houses. For Focus, 35mm circulation makes sense because many films play widely enough and roll out slowly enough to amortize print costs.

Focus will be patient with its core customers and their financial challenges in going digital. . . . Supplying them with 35mm in the meantime allows us to play them and play them cheaply by using prints multiple times at no cost more than shipping.

But studio subsidiaries must also provide the DCI-compliant Digital Cinema Packages. Some art houses have converted and can handle them. More important, many of these films play in “smart houses.” These are screens, located in a mainstream multiplex, that will show films that get good response in art-house runs. If a movie has crossover appeal, a smart house can hold it long enough to build word of mouth. Right now, several multiplexes are playing Tinker Tailor, The Descendants, My Week with Marilyn, and the like. There are, Jack Foley estimates, between 250 and 500 screens of this sort in the country.

Smart houses, as parts of multiplex circuits, are usually showing DCPs. At the moment, Foley points out, the Virtual Print Fee is onerous for non-major distributors, since if they supply a DCP to a theatre, they must pay the fee (often about $850). Foley believes that eventually all viable art houses will convert to DCI projection, the VPFs will expire, and every party will reap the benefits of digital cinema.

Films distributed by smaller, independent distributors offer still other options. These are companies like Kino Lorber, IFC, Magnolia, Strand, Roadside Attractions, Oscilloscope, Zeitgeist, and their peers. They circulate the most offbeat product, dramas like The Messenger and Meek’s Cutoff (Oscilloscope), along with documentaries and foreign titles like Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Pina, and Certified Copy (IFC) and 13 Assassins (Magnolia). Restorations and reissues of classics, such as Metropolis (Kino Lorber) and On the Bowery (Milestone), operate in this sector as well. Like their studio counterparts, these firms need the video aftermarket to support purchasing theatrical rights.

Some of these distributors supply 35mm prints, like Magnolia’s very pretty one of Melancholia that I saw in Madison a few weeks ago. But most Virtual Print Fee agreements apparently demand that if a non-Majors film arrives on DCP and is to be played on a projector financed through the VPF, the independent distributor must chip in the fee. Some are willing to do that.

What surprised me most was learning that independent distributors will supply the film in many digital formats, even Blu-ray and DVD versions. There are now first-run films playing commercial theatres, even in Manhattan, in Blu-ray. On small screens, many exhibitors say, that format works fine and their patrons don’t notice. Many of these films aren’t available on 35mm prints at all, although a distributor may prepare a print if there’s enough interest to help pay for it.

A lateral option, sometimes called i- or e-cinema, also exists. There are now companies offering theatre delivery via the Internet. The idea is to stream encrypted files, in HD, to cinemas signed onto the system. Emerging Pictures, currently the dominant player in this domain, will deliver material from many independent distributors, including Sony Classics, IFC, and Magnolia. Emerging will also supply performing arts shows. Other companies offering or preparing to offer comparable services are Specticast, Proludio and Storming Images.

Summing up: If an art house wants to show only films from the independent, second-tier distributors, then the pressure to convert to DCI isn’t great. The exhibitor will, however, be playing more and more movies on DVD or Blu-ray. But the fact is that one Iron Lady pays for a lot of Take Shelters. The need to show art house blockbusters will eventually push most art-house operators toward buying or leasing the high-end equipment.

In between

Juliet Goodfriend, Art House Convergence. Photo by Chuck Foxen, reproduced with permission.

The new digital problems confronting the art-house market don’t end with decisions about equipment.

For one thing, DCP playback creates a degree of inflexibility that festivals have also encountered. Shifting showtimes and screens is more difficult, as it may require special permission and a new key to open the file. There is, moreover, an air of surveillance that is inimical to the more informal, trust-based atmosphere of most art-cinema milieus.

More constraints appear if the exhibitor chooses to fund the changeover through the Virtual Print Fee. For example, VPFs oblige the exhibitor to screen only films supplied by the major companies–the ones that created the Digital Cinema Initiatives. If an exhibitor wants to play an independent distributor’s title on a DCP, that distributor needs to pay the fee, in effect helping to cover the theatre’s conversion. Other constraints are more obscure. I can’t report reliably on them because when joining a VPF program, the exhibitor signs a non-disclosure agreement pledging not to reveal details of the deal. But hints suggest that exhibitors could be prevented from “splitting,” that is showing two or more films in the same auditorium on one day. This is a practice that many art cinemas rely on because it allows them to vary programs in mid-week, or to compensate for having only one or two screens.

Another effect of the digital revolution comes from streaming, or Video on Demand. Many of the most desirable films from independent distributors are released on VoD simultaneous with or even before theatrical release. At the Convergence, one exhibitor pointed out that Melancholia was available on VoD several weeks before she could play it on her screen.

Distributors offer several justifications for their streaming decisions. Ancillary income from DVD has declined steeply, and VoD pays well. According to Josh Dickey’s Variety article and Daniel Miller’s Hollywood Reporter piece on the rise of VoD deals, Margin Call, which attracted $5.3 million theatrically, took in an estimated $4-$5 million on VoD. Another advantage is that streaming provides fast returns, while any DVD income won’t show up for many months. Moreover, VoD can reach audiences in areas of the country that don’t have art houses. And some distributors believe that the theatrical and VoD audiences don’t significantly overlap. For Margin Call, it’s claimed, most people who saw it in the theatre didn’t know that it was on VoD, and many who caught it on VoD would not have gone to a theatre.

There don’t seem to be any firm conclusions about how much day-and-date or early release on VoD can harm a film’s theatrical release. In the absence of detailed evidence about VoD grosses, exhibitors are understandably nervous.

Finally, what about access to older films in studio collections? These titles are central to repertory cinemas, and many art houses that play recent releases schedule some classics too. Yet some studios are increasingly reluctant to supply 35mm prints from their libraries. If the film isn’t on DCP, exhibitors may be told that they must pay to have a DCP made, or show a Blu-ray or DVD. But repertory cinemas are reluctant to screen on the low-resolution formats, and rarer and more obscure titles are unlikely to be available on disc. Unhappily, we may get less repertory programming on the whole. Audiences that don’t live in a town with an archive or cinematheque will have less chance to discover film history.

A tradition, forced to reconfigure

The energetic arts entrepreneurs who gathered at Midway can claim a proud tradition. The art-house and repertory model of exhibition, originating in the 1920s, came to prominence after World War II. These theatres played imported films from small distributors, with occasional independent items mixed in. A 1949 Variety article noted that the market had a boom that was starting to level off.

Postwar surge of art theatres, born as an outlet for the flock of British and foreign-lingo pix which hit this country after V-J Day, is now slowing to a normal growth. In the U. S. at the present time there are 57 theatres which are out-and-out art houses and 226 additional flickeries which play foreign-made product part of their time. . . . With the exception of Newark. . . every city of 200,000 or over now sports at least one art theatre.

Then as now, these theatres offered a more personal atmosphere and upscale service (tea, coffee). Like today’s art houses, they depended on what we call buzz; their films were very much critic-driven. Then as now, British films could break out, with Henry V (1944), Hamlet (1948), and The Red Shoes (1948) proving very successful. The major studios sensed a new market and began financing and importing films from overseas. This policy has been revived several times since, up to today’s “studio boutiques” like Focus and Sony Classics. And some art-house operators moved into distribution themselves. Exhibitor-distributors like Cinema 5 and New Yorker are the predecessors of IFC and Music Box.

This system of distribution and exhibition has survived six decades. But in that period, art houses haven’t faced any change as sweeping as this. The big distributors have decided on a standard, and the most powerful theatre chains have converted. History suggests that critical mass on this scale is irresistible.

Many major art houses and nonprofits have already converted. Film Forum in New York City, which mixes repertory and new releases, has long had a policy of showing classics on 16mm or 35mm film. But now the theatre is using DCPs; some restorations are not offered on film, and that trend is almost certain to grow. Taking the bull by the horns, Film Forum is running a series, “This is DCP,” to introduce the audience to the format. Bruce Goldstein’s program note asks:

Is watching a DCP the same experience as watching a film print? The jury is still out, so for this one-week series, we’ve chosen the crème de la crème of classics on DCP and have invited Sony Pictures’ Grover Crisp, one of the true giants of film restoration, to explain things on opening weekend. You be the judge.

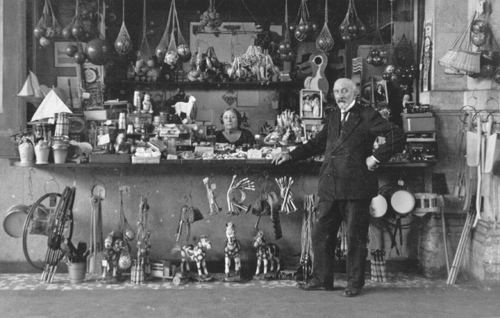

Exhibitors who haven’t yet converted are raising funds through information campaigns and capital exercises. Single-screeners face the toughest climb. Take the Art Theatre of Champaign, Illinois, seen in my topmost still. It opened in 1913 and has had a pretty typical history (including showing erotic films). Revived as an art house in 1987, it has screened foreign and independent cinema, as well as classics and out-of-the-way items, including a revival of City of Lost Children. Now the Art needs to go digital. Its operator, Sanford Hess, stresses that without the new gear, priced at about $80,000, he will have to close the venue when the lease runs out in December. He has started to rebuild the enterprise as a co-operative. Since the co-op launched in December, 270 people have bought shares, generating about $29,000 toward a new projection system. (You can trace the progress of the campaign on Facebook.)

David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest suggests that 5% of US screens could disappear during the conversion. That number sounds small, but it amounts to nearly 2000 screens, and many are likely to be in art houses. The prospects remind me of 1928, when the studios agreed to shift to talking pictures. Put aside your pity for those actors like George Valentin in The Artist. Harder hit were the people who worked at the more than four thousand movie theatres too small, too remote, or too poor to be wired for sound. Of course that technological shift took place during the Great Depression. But our economy isn’t looking exactly vigorous, and in some ways today’s technological changeover is more hazardous. 1930s audiences didn’t have cable and Netflix to make staying home more attractive.

This is the fifth in a series on the transition to digital projection.

Thanks to Jack Foley of Focus Features distribution for sharing information with me. I also got useful information from Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics, Mike Maggiore and Bruce Goldstein of Film Forum, Jim Healy of our Cinematheque, Sanford Hess of the Art Theatre, and Merijoy Endrizzi-Ray of Sundance 608.

I’m very grateful to Jan Klingelhofer of Pacific Film Resources, Russ Collins of the Michigan Theater Foundation, and the membership of the Art House Project for welcoming me so generously to their annual Convergence. Special thanks as well to Juliet Goodfriend, Cordelia Stone, and Valerie Temple of the Bryn Mawr Film Institute for their survey of the art-house market, which I have drawn on here. That online survey, conducted in late 2011, collected data from 126 theatres in 29 states and Canada. I also benefited from conversations with Lisa Dombrowski, who’s writing a book on specialty cinema in the US, and Jenn Jennings, who is making a film, The Lost Picture Show, about digital conversion.

A good overview of the early development of digital art-house exhibition is offered by Michael Goldman’s 2008 article, “Digitally Independent Cinema,” in Filmmaker magazine. The Variety article I quoted from is “7 out of 10 Sureseaters Click” (27 July 1949), 13. For the history of art cinemas, see Michael F. Mayer, Foreign Films on American Screens (Arco, 1965); Barbara Wilinsky, Sure Seaters: The Emergence of Art House Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2001); and Kerry Segrave, Foreign Films in America: A History (McFarland, 2004). Tino Balio’s The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2010) traces the phenomenon from the standpoint of distribution. I discuss Tino’s book more here.

Box office figures for recent releases are taken from Box Office Mojo. My figures on theatres that closed during the conversion to sound come from The Film Daily Yearbook from the years 1931-1935. The process, which has many analogies with today’s digital conversion, is discussed in Donald Crafton, The Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound 1926-1931, vol. 4 in History of the American Cinema, ed. Charles Harpole (Scribners, 1997), Chapter 11, and Douglas Gomery, The Coming of Sound (Routledge, 2005), Chapter 8.

Seven Gables Cinema, Seattle, Washington. Photo by Joe Mabel. Reproduced under Gnu Free Documentation License.

PS 20 February: John Fithian, President of the National Association of Theatre Owners, confirms the prospect of theatre closures here: “For lower-grossing theaters, it’s just not affordable. I predict we’ll lose several thousand screens in the U.S.”

The ten best films of … 1921

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

More Northern European drama

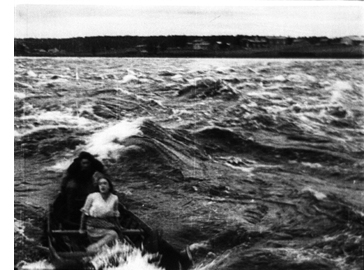

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

We’re introduced to the couple by following the rogue Vallavan’s entry into the town; Johan seems almost a secondary character until Vallavan leaves. When Johan breaks his leg, Merit agrees to be his wife. Now we’re attached to her standoint and see her life of drudgery under the petty tyranny of Johan’s mother. Vallavan returns, and Merit falls under his spell. Taking her hand, he says, “I want to rescue you.” After she has fled with him, Johan clumsily wanders the rocky shore. “Will I ever see Merit again in this life?” The narrational weight passes to him as he decides to pursue the runaways.

Like Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919), Johan presents marriage as a trap for unwary women. Our shifting attachment, from Vallavan to Merit and eventually to Johan, allows us to see the situation in many dimensions. As a sort of parallel, Stiller makes fluid use of the now solidly-established conventions of continuity editing. Vallavan’s seduction of Merit is played out in tense shot/ reverse-shot, and there’s an engrossing moment involving delicate shifts in point of view. When the bedridden Johan sees Merit leaving, after his mother has cast her out of the house, he must smash a window pane with his elbow in order to call to her. Stiller’s dynamic eyelines, direction of movement, and precise changes of camera setup here show that he had mastered the American style.

Alongside this finesse, there is still plenty of outdoor action, highlighted when Vallavan rows Merit away in the tumultuous river. Filmed from another boat, the actors are all but engulfed by the waves. It was presumably scenes like this that the parent company, Svensk Filmindustri, hoped would attract international attention. At this period Svensk, dominant in the local industry, was hoping to sell its films on a global scale. That ambitious plan failed, but it left us with many outstanding movies and soon brought Stiller, along with Sjöström, to Hollywood.

Johan is available on a Region 2 PAL DVD, coupled with Kaurismaki’s Juha, another adaptation of the Juhani Aho story.

The joys of small-town life

Last year I included two films by William C. deMille, the considerably less famous brother of Cecil B. The year 1921 saw the release of what is today his best-known film, Miss Lulu Bett. It was based  on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

The return of the husband’s globetrotting younger brother Ninian after a twenty-year absence injects some life into the situation. Taking the family out to dinner, he realizes just how boring the family is (right), and to liven things up, suggests that he and Lulu perform mock marriage vows. Dwight realizes that the ceremony is legally binding, and, already attracted to Lulu, Ninian suggests that they treat it as a real marriage. Desperate to escape her dreary situation, Lulu agrees. The relationship proves agreeable, and Lulu declares that she will learn to love Ninian–when he reveals that he had previously been married, though he doesn’t know whether his first wife is dead (in which case he and Lulu are married) or alive (in which case they aren’t). Unwilling to take a chance, Lulu returns to the Deacons, who consider her disgraced and treat her even worse.

The film avoids melodrama. Ninian is not a villain; he’s kind to Lulu and sorry for the position he’s placed her in. It remains to Lulu to summon the gumption to leave the family and find her own happiness.The whole thing is told with restraint and little touches of humor that draw the viewer into a deep sympathy with Lulu’s plight.

Lois Wilson’s performance as Lulu is crucial in this. She is at once plain enough that we can believe she is in danger of becoming an old maid and pretty enough to plausibly attract the attention of the handsome local schoolteacher. Wilson’s most prominent role came two years later, when she starred as the heroine in James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon.

Miss Lulu Bett is the only one of William’s films available on DVD, paired with Cecil’s Why Change Your Wife? As so often happened, William seems to take a back seat to his famous brother, but the pairing is a logical one, in that William wrote the script for Why Change Your Wife?

Another small-town drama of the same year is Lois Weber’s The Blot. In 1981, when I was teaching a course on American silent film at the University of Iowa, I wanted to quickly demonstrate to the students that the silent period was not an era of exaggerated acting and naively melodramatic plots. I showed a double feature of The Blot and King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924). The latter portrays changing sexual mores through the story of three generations of the same family, with a young woman of the Roaring Twenties questions the necessity of marriage when she discovers that her mother is contemplating divorce. I think Wine of Youth (unfortunately not available on video) and The Blot convinced my class that silent films could be both sophisticated and subtly acted.

The “blot” of Weber’s title refers to the notion that people in professions depending on intelligence and education are poorly paid, while tradespeople and children from rich families are well off. The representatives of the underpaid are a college teacher, Prof. Griggs, and a young, idealistic minister. The parallels to recent events are striking. College professors may not be so badly paid as in the 1920s, but the move toward institutions of higher learning depending on adjunct lecturers has created a similar issue. In general, the income gap is familiar: the rich young wastrels taking Prof. Griggs’s course represent what we now call the one percent, while the professor and minister live on a much lower plane.

Weber’s drama is not quite this bald, however. Various levels of prosperity are represented. The professor’s family lives in shabby gentility, his wife grimly struggling to keep food on the table and his daughter Amelia, in delicate health due to a lack of nourishing food, working in the local library. Their neighbors are the family of a successful shoemaker, who live well but lack education. The shoemaker’s wife in particular resents what she perceives as intellectual snobbishness in the professor’s family and takes every opportunity she can to flaunt her comparative wealth.

Her son, however, has a crush on Amelia, as does the poor minister. Into this situation comes Phil West, the professor’s rich but indolent and mischievous student. Also attracted to Amelia, Phil for the first time encounters real poverty and is  shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

The plot is remarkably dense and unpredictable. Every scene involves glances that lead to new knowledge or serious misunderstanding, deflecting the plot into new directions. Early on it is impossible to say which of the three young men Amelia will end up with, and even by the late scenes, when only two plausible romantic candidates remain, we have no idea which she will pick. As in many of Weber’s films, she does a bit of preaching about the social problem involved, but in The Blot she leaves this until near the end and gets it over quickly and fairly believably. The considerable but gradual change in Phil’s attitude toward education and the problems of poverty is also made believable. The prosperous neighbor’s change of attitude may seem a bit sudden, though it is somewhat motivated by a line early on.

But on the whole, even more than with Miss Lulu Bett, this is an absorbing story with characters for whom we care. Weber uses motifs as skillfully as any director in the early phase of the classical Hollywood cinema. Watch in particular how many different ways she uses the Griggs family’s cat and her two kittens: to demonstrate the family’s poverty, to be the main means of the neighbor lady’s spite, to introduce some comedy, and so on. Even more pervasive is the way that shoes become tokens of characters’ various social positions.

The Blot is available on DVD from Image. Those interested in Weber as a director should note that next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna plans a retrospective of her work.

Which is best? Damfino.

In past year-end lists, we’ve watched Harold Lloyd, Charles Chaplin, and Buster Keaton creeping toward their great features of the 1920s. This year two of them move cautiously into longer films, and the other releases two more terrific one-reelers.

The Boat is one of Keaton’s most admired shorts. In it, he, his wife, and their two young sons build a boat, the Damfino, and unwisely launch it on the open ocean. Everything that can go wrong does: the life-preserver sinks, the anchor floats, and naturally a storm hits. The wife’s pancakes aren’t edible, but one temporarily patches a leak. Throughout the intrepid band carries on against all obstacles.

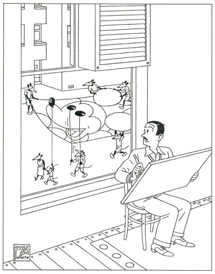

Less perfect but more dazzling and (perhaps) funnier is The Playhouse. The premise of a small variety theater creates an episodic, messy narrative, but it allows Keaton to play out a series of four “acts.” Initially we see Keaton buy a ticket and enter an auditorium where the audience, the orchestra, and all the performers are played by “Buster Keaton.” As one of the audience members remarks, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show,” which is true in more way than one. The multiple images of Keaton were accomplished entirely in the camera, by cranking back the film with precise timing and uncovering a different part of the lens at each pass. The precision when one Keaton figure talks to or dances with another is amazing.

This all turns out to be a stagehand’s dream. (Keaton being the stagehand.) The multiplication motif returns as an act involving two pretty girls who happen to be twins–something Buster  doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

The Boat is included on Kino’s disc of The Navigator and The Playhouse with their out-of-print DVD of The General. Still in print, however, is Kino’s eleven-disc set of the features and shorts. For those in the UK and other region-2 countries, Eureka! has a “Masters of Cinema” three-disc set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films 1917-1923,” which includes many of his earlier films with Fatty Arbuckle.

The year saw Lloyd and Chaplin make their first feature films, though both releases were still fairly short. I’m not really counting A Sailor-Made Man as one of the top ten of the year, since it’s a delightful but decidedly light item. Just another reminder that Lloyd is inching toward greatness.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

The shipboard scenes allow Harold to get in some funny bits, mainly involving him trying to be tough and succeeding at first by sheer accident. Later, however, he is inspired by the heroine’s danger to become a real rescuer. It’s a sign of bigger things to come.

New Line’s Harold Lloyd boxed set is out of print, but you can still get the volumes separately. A Sailor-Made Man is in Volume 3, along with such delights as Hot Water and For Heaven’s Sake.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

In the meantime, the mother has become a rich singer, and coincidentally she comes to the slums doing charitable work. The authorities eventually try to remove the Kid to an orphanage, and later a flop-house proprietor turns him in to receive a reward. Still, Chaplin doesn’t milk the pathos, and a happy ending duly arrives.

The Kid is available in a decent print along with A Day’s Pleasure and Sunnyside on the “Charlie Chaplin Special” DVD. Our recording off Turner Classic Movies strikes me as being slightly better quality, so you might keep an open to see if they reshow it. It was also announced this week that The Kid has been added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

Fuzzy movies, big and small

Soft-style cinematography had been tried in some films of the late 1910s, most notably in Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. But in the 1920s it spread. In Hollywood, it was mainly a technique for making beautiful images and especially for creating glamorous close-ups of actresses. In France, it was a way of tracking a character’s inner life.

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a huge bestseller, and the first film adaptation in 1921, directed by Rex Ingram, was equally successful. To many, it is remembered for having made a super-star of its main actor, Rudolph Valentino. Anyone who has seen him as the caricatured Latin Lover of his later films will be pleasantly surprised to discover that the man could act, as could his leading lady, the lovely Alice Terry.

Ingram was the quintessential middlebrow director of the 1920s, doing big-budget, respectable adaptations of popular literature (e.g., Scaramouche, The Prisoner of Zenda). To me, Four Horsemen escapes the stodginess of the later films, at least to some extent (as does his other 1921 film, The Conquering Power). It and the other film in this section were borderline cases, chosen as much for their historical importance as their quality, perhaps, but definitely worth watching.

One of Four Horsemen‘s greatest strengths is its photography. Ingram worked consistently with one of the greatest cinematographers of the 1920s, John F. Seitz, who created glowing images of  sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

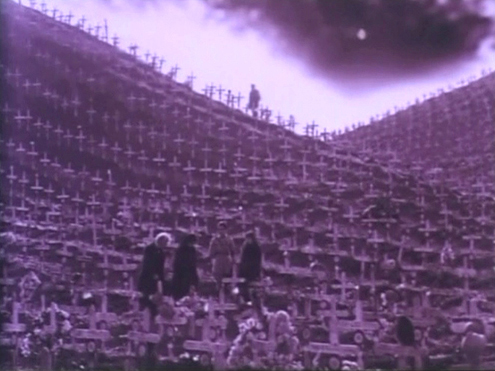

Four Horsemen was also an early entry in the anti-World War I genre of the 1920s and 1930s. Its final scene in a vast military cemetery of identical white crosses remains a powerful one. (See above.) Here, however, the Germans are still stereotypes, militaristic puppets with no redeeming features. Even that notion would gradually change, however, until nine years later All Quiet on the Western Front could recount the war from the German point of view.

Four Horsemen is available on DVD on demand from Amazon, supplied on DVD-R. In the same format, one can order it on a set with a documentary on Valentino. The reviews of the latter suggest that the visual quality is good.

(For more on this photographic style, see my “The soft style of cinematography,” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 287-293.)

I’m not a huge fan of Marcel L’Herbier, and I’m not entirely sure that El Dorado is a full-fledged  masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

In a way this is a somewhat silly, literal notion, and yet it’s exciting to see filmmakers exploring new devices relatively early in film history. Gauzy filters, distorting mirrors, slow-motion superimpositions, rhythmic cutting, and subjective moving camera were soon to be in common use by a small group of French directors. El Dorado was also the first film to be filmed within the Alhambra, which lends it considerable visual interest.

If we’re still writing this blog in 2019, our list will probably include the culminating film of the movement, and arguably L’Herbier’s best silent film, L’Argent.

Not many French Impressionist films are available in the U.S. If you have a multi-region player, El Dorado is paired with L’Herbier’s earlier L’homme du large (1920) on a French DVD.

Tigers and lepers and a mysterious yogi

We tend to think of serials as having many episodes and being low-budget additions to programs. That’s the American model, but in Europe things were different. Louis Feuillade’s serials are among the gems of the 1910s. In Germany, serials tended to have fewer episodes but bigger budgets–much bigger. Many were only two parts, most famously Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (coming next year to our top-ten list) and Die Nibelungen (coming in 2014). Lang had launched into serials with Die Spinnen (1919 and 1920). The two parts have terrific things in them, but Lang never went on to finish it.

He was, however, still collaborating on screenplays for director Joe May, who specialized in epic serials set in exotic countries and starring his wife, Mia May. Highly entertaining though these films are, they are largely forgotten, even by most lovers of silent cinema. Das indische Grabmal is the exception, though even now few have had a chance to see it. In 1996 it was shown at “Il Gionate del Cinema Muto” festival in Pordenone and was all too briefly available on an Image DVD (as The Indian Tomb) now out of print. Track it down if you can.

Full of the stars of its day, Das indische Grabmal is set largely in India, and its plot was inspired by the Taj Mahal. A ruthless maharajah (played with relish by Conrad Veidt) cloaks his cruelty under a veneer of European courtesy. He plots to shut his unfaithful princess (Erna Morena) in a beautiful tomb along with her lover (Paul Richter, better known to modern audiences as Siegfried). He calls in a famous European architect (Danish star Olaf Fønss) to build it, and the architect’s fiancée (Mia May), rightly fearing dirty work afoot, follows. One pit full of tigers and one of lepers lie waiting to endanger the visitors. The sets are beautiful. The Germans by this point could do them at full scale (above left) and as marvelously deceptive miniatures (above right). Das indische Grabmal is constantly entertaining and perhaps the best of its type, at least of the films we have access to.

Lang directed a two-part remake of this film in 1959. Both are good, but I prefer the silent one.

Some runners-up

As I mentioned, we had trouble narrowing down our list this year. Here are some others that could have replaced some of our prime choices. The German stage director Leopold Jessner adapted the play Hintertreppe (Backstairs). It’s a Kammerspiel, set in two apartments and the courtyard between them, and concerns a simple love triangle among a maid, her absent lover, and the postman who loves the maid so much that he forges letters from her sweetheart to keep her happy. Antti Alanen kindly reprinted my notes on the film here.

Carl Dreyer’s third feature, Leaves from Satan’s Book, remains one of the most widely-admired variants on the Intolerance formula of presenting thematically linked historical episodes. The dynamic final last-minute non-rescue shows that Dreyer learned a good deal from Griffith’s crosscutting too. Leaves is available on a Danish DVD with English subtitles and an alternate ending. Murata Minoru’s Japanese feature Souls on the Road, another exercise in complex crosscutting, and Feuillade’s polished L’Orphéline are solid runners-up as well. Neither is available on commercial DVD, as far as we know.

Destiny.

HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to Georges Méliès

Kristin here:

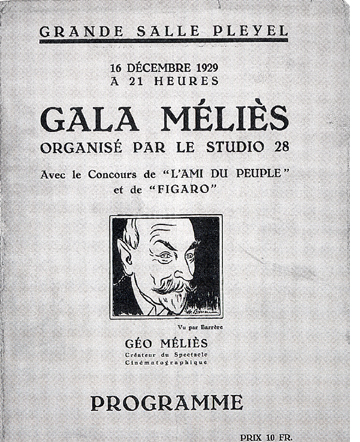

This is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Georges Méliès (1861-1938). I doubt that the release of Hugo was timed to coincide with the occasion. If it were, no doubt the press kits issued by Paramount would have stressed the fact. Still, it’s a happy coincidence.

Hugo is receiving a lot of press attention, not surprisingly. If you’ve read more than one or two of the reviews and articles about Martin Scorsese and his film, you already know the two main hooks that journalists have hung them on. (Whether these originate from the pressbook or are just so darned obvious that everyone can figure them out, I don’t know.)

One, Scorsese is passionate about film history and preservation, so Brian Selznick’s best-seller quasi-graphic novel for children, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, based on the old age of early director George Méliès, would be a natural source for him to adapt. Especially so, since Selznick designed the illustration-heavy book to imitate a film, with series of drawings suggesting camera movements.

Two, the subject of Méliès’ pioneering special effects in the service of fantasy would be the perfect vehicle for Scorsese’s first venture into 3D.

True, no doubt, both of those points, and necessary to ease viewers with no knowledge of film history into this fairly sophisticated film. Not that the critics provide much help with the film’s many allusions to Parisian culture of the first decades of the twentieth century. There are real popular songs and posters for many silent films. I didn’t see any reviews pointing out that James Joyce and Salvador Dalí can be glimpsed fleetingly in Madame Emile’s café. (I spotted Joyce but not Dalí, only learning of the latter’s presence from the credits.)

Apart from signalling such references, however, there is a great deal more that one can say about the film. Some aspects of it are obvious, as befits a movie made in part for children. Others are more subtle, as befits a movie made in part for adults. I’ll offer a few observations here.

By the way, reviewers have made much of the idea that Hugo is not really for children, who would be bored and perhaps frightened by it. I suspect that children under about the age of 10 would be, but older children and teenagers, especially those who read books, should be intrigued by and enjoy it. Like Pixar films or The Simpsons, it’s the sort of thing that can be enjoyed by adults as well as children.

Movies within movies

Hugo is centered around Méliès’ work and tries to recreate something of the magic of the making and viewing of these films. Yet beyond this, it is steeped in the forms and subjects of pre-World War I cinema in general, to the point where the plotlines of Hugo subtly imitate early films.

A turning point in Hugo‘s story comes when Hugo and Isabelle invite fictitious film historian René Tabard (whose name is borrowed from the popular, Chaplin-impersonating teacher young student in Zero for  Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

In the book, the station’s Inspector, played by Sacha Baron Cohen, is a minor figure, glimpsed once from a distance by Hugo and finally coming to threaten him with arrest on page 412. His war wound and early life as an orphan are not part of his character. The Inspector is abetted by the café owner Madame Emile and the newsstand proprietor Monsieur Frick, sinister figures who appear only in this single late scene. They exist primarily to reveal the news of the discovery of the corpse of Hugo’s drunken uncle and to bear witness to Hugo’s thefts of croissants and milk from the café. The flower-shop girl, Lisette, whom the Inspector clumsily courts in the film, is not in the book at all.

What Scorsese very cleverly does is to expand these characters and have them play out what are in effect two brief narratives that could easily be imagined as early silent shorts. Madame Emile (Frances de la Tour) and Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths) are transformed from nasty busybodies into a charmingly comic elderly couple whose tentative flirtation is thwarted by Emile’s aggressive dachshund. In two scenes, the dog bites Frick, once on the finger and once on the ankle. In the third scene, Frick solves the problem by providing a lady dachshund to divert the pesky pooch’s attention. One could easily imagine this as a short film from around 1906, making these two the leads and concentrating on their courtship. The dog could thwart the news-vendor’s approaches a few times before the happy ending is achieved with the introduction of the second dog.

The overbearing Inspector’s romance with Lisette is developed at greater length, and one could imagine it as a one- or even a two-reeler of the early 1910s. The Inspector’s attempts to court the young lady could be contrasted with his chivvying of the pathetic young orphan, actions that make her reject his advances. At the end, she might witness him relenting and treating the boy kindly, as indeed happens in Hugo, leading to another happy romantic conclusion.

In general, the situations and characters that we encounter in Hugo are common in early cinema. How many films, especially French ones, involve gendarmerie with their round, flat-topped caps, chasing mischievous little boys? How many melodramas revolve around poor children made homeless by their parents’ or guardians’ drunkenness? How many gags involve men stepping on musical instruments and smashing them? While the most explicit cinematic reference is to the Harold Lloyd feature Safety  Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

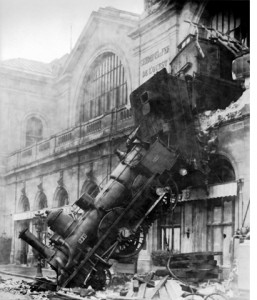

In a sense there are little topical and instructional films as well, with the reference to the dramatic historic accident at the Gare du Montparnasse on October 22, 1895, when a train crashed through its buffers and out the front wall of the station. (In reality, one death occurred: the wife of a news vendor who was minding the shop for her husband. Perhaps the Emile-Frick romance creates a happy ending of the cinematic variety to make up for that tragedy.) We also have the lesson in cinema history provided by Tabard. At one point in the flashback narrated by Méliès, apparent newsreel footage of World War I troops, touched up with hand-coloring, appears.

The film-like subplots all end happily, yet they are represented as being reality within Hugo. Perhaps for that reason, none of these brief narratives is the sort that Méliès would have used in his own films. They’re more like the non-fantastical comedies and chases made by Louis Feuillade and other directors.

The happy ending for Méliès occurs in Scorsese’s film, and yet it also happened in reality, if not quite the way it is shown here.

Cruelty, kindness, and the shape of the story

The structure of the narrative reflects the simplicity of each short film. It conforms well to the four-part narrative structure that I have claimed to be conventional practice in classical storytelling. Yet it also breaks neatly into two halves, the first about cruelty and the second about the sort of kindness that makes possible the happy endings. One can picture it as a V shape, with Hugo descending into greater loneliness and danger up to the mid-point and then climbing back toward happiness with the help of others.

Early on, both fate and other people are cruel. A museum fire has killed Hugo’s father, and his mother had earlier died of unspecified causes. Hugo’s drunken uncle wrests him from his home and school to live a fugitive life in the station. “Papa Georges,” whose full identity we do not learn until well into the film, seems unnecessarily harsh with the young Hugo. The Inspector obsessively hunts down stray children to send off to the orphanage. The bookseller Labisse, though generous in loaning books to Hugo’s friend Isabelle, looks upon Hugo with disdain. Even the two dogs, Madame Emile’s comic dachshund and the Inspector’s doberman are growling, threatening beasts.

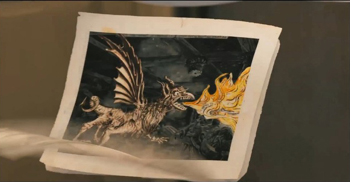

The automaton, of course, is the key to all. Once it provides the necessary clue by drawing the  famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

Ordinarily at this point in a Hollywood film, there would come a section where the protagonist struggles against obstacles to achieve his goal. In Hugo, however, the crisis at the center leads immediately to a series of kind actions. Upon returning to the station after the drawings discovery, Hugo runs into M. Labisse, who unexpectedly gives him a book that the boy and his father had read together. Then Madame Emile urges the Inspector to speak to Lisette, whom he has admired from afar, and coaches him in how to smile pleasantly. His smile, plus his halting success in his first conversation with Lisette, motivate his eventual ability to take pity on Hugo.

This scene leads directly to the scene at the “Film Academy Library” (a giant fictitious room full, apparently, of books on cinema) where the film historian and Méliès fan, René Tabard, appears. He will provide the screening of A Trip to the Moon which finally draws Méliès out of his depression to some degree. Yet the filmmaker still despairs as he thinks of the disappearance of his studio, the rest of his prints, and his beloved automaton. Hugo rushes off to fetch the latter, and after an extended chase sequence returns it to Méliès with the help of the Inspector, who saves the machine and the boy from an oncoming train. Recognizing something of his own youth in the distraught boy, the Inspector turns him over to Méliès for the happy ending.

The exception to the cruelty/kindess division of the film is Isabelle. In the original book she is not such a pleasant character, often arguing with Hugo. She does not have the joyous desire for adventure that the Isabelle of the film displays. The change is an improvement. In part this is because Hugo is such a very grim and forlorn character through much of the book. Portraying him that way in the visual medium of film might make his plight too pathetic to be entertaining. Isabelle’s early sympathy for him and fascination with the mystery of the automaton carries a strong thread of hope across both halves of the narrative.

In the lengthy epilogue there is a gala screening of some recovered Méliès prints, and a party is held. All the significant characters are present, with their satisfactory futures assured. Hugo will seemingly become a magician (as he does in the book). Isabelle has apparently found her hoped-for purpose in life, for she starts writing down the story that we have just witnessed. (In the novel, Hugo himself writes The Invention of Hugo Cabret, though he attributes it to the automaton.)

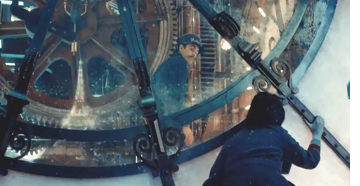

A machine-made ending

The film ends with a tracking shot, independent of the characters’ points-of-view, into a nearby room where the automaton sits, still and alone. As we approach its enigmatic face, the image fades out. The moment ends the imagery that has continued through the film, of humans as machines and  machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

The machine imagery goes further. The opening of the film dissolves from a set of moving clock gears to merge them graphically into a high view of the boulevards of Paris, which momentarily appears as a giant glowing, whirling machine with the Eifel Tower, symbol of the modern machine aesthetic, at its center. The repair of a wind-up mouse becomes the first small point of emotional contact between Méliès and Hugo. The Cinématographe camera/projector that fascinates Méliès even more than the moving images on the screen becomes the central machine, one which produces what one normally thinks of as the most private and mental of events, dreams.

All this machine imagery is fairly obvious, but it seems completely appropriate if we remember that this is, after all, a film partly for children. What I’ve been describing are things that a smart child could grasp, but the imagery and story aren’t done in anything like a condescending way.

The automaton, by the way, really did the drawing in the film itself, without CGI or other sorts of animation being used. For a three-minute film that ends with a fast-motion demonstration of its drawing capabilities, see here. For a demonstration of the restored Maillardet automaton in the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, which Selznick used as his inspiration, see here, where it creates a drawing as complex as the one in the film. This automaton also revealed its origins when, after being restored, it signed its maker’s name.

[Dec 9: My claim that the automaton did the drawing without special effects was based on some statements by the company that made it (or more specifically, 15 versions of it). A recent article here interviews the film’s visual-effects supervisor Rob Legato reveals that the drawing scene was accomplished using magnets below the table: “The robot or automaton was not CG, although there were some CG doubles for some complex shots such as the train line fall. Prop builder Dick George constructed 15 automaton versions and some that actually could draw on paper. The VFX and special effects team solved the complex task by using magnets. Below the paper was a motion controlled magnetic system that traced the hand encoded drawing. The arm then moved to match the magnets and draw the famous picture. In a couple of shots if you could pause and really study the frame you might see that the pen nib, at those points, ‘is a ball point and not an ink well pen,’ comments Legato.” So the automaton did do the drawings, but not based on its complex system of gears and other clockwork visible inside it.]

How accurate is it?

Naturally the events of history are messier than the neat scenario of a mainstream film could encapsulate. Still, given the constraints involved, Hugo‘s modifications of the facts seem quite reasonable, and on the whole the general public will exit the theatre with a decent impression of Méliès’ career.

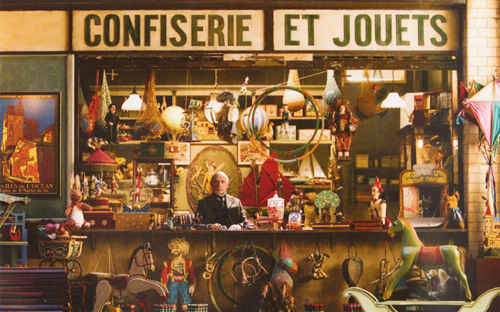

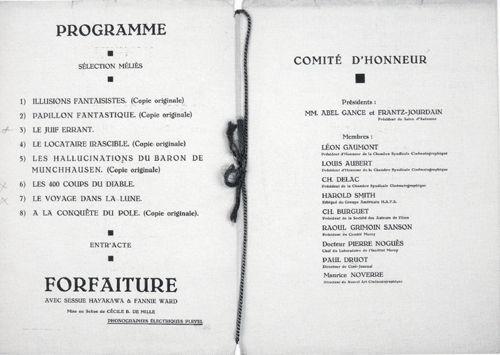

In fact he was married twice. Jehanne d’Alcy had been Méliès’ mistress well before they married in late 1925. They had both worked at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin before the cinema was invented, and d’Alcy appeared in many of Méliès’ films. (His first wife, Eugénie, died in 1913.) D’Alcy brought with her the ownership of a little candy-and-toy shop outside the Gare Montparnasse, which the couple transferred inside the station and ran together (see bottom). World War I did not cause the demise of Star Films. Méliès had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

As biographer Paul Hammond describes his decline, “Georges Méliès had become an anachronism, an artist left behind by economic and aesthetic developments.” In looking at Méliès’ late films, we might keep in mind that 1912 was the year of Albert Capellani’s remarkable serial adaptation of Les misérables. Max Linder was at the height of his popularity, and D. W. Griffith was making some of his finest one-reelers. The three great Swedish silent-era directors, Mauritz Stiller, Viktor Sjöström, and Georg af Klercker, all made their first films in 1912. The year 1913 would see a burst of cinematic inventiveness around the world, and Méliès would have seemed all the more old-fashioned by comparison had he continued to make movies. Nevertheless, he remains perhaps the only one of the very earliest generation of filmmakers whose work we return to not simply out of historical interest but for the fun and wonder of the films.