Archive for the 'Film history' Category

German classics for the pandemic and beyond

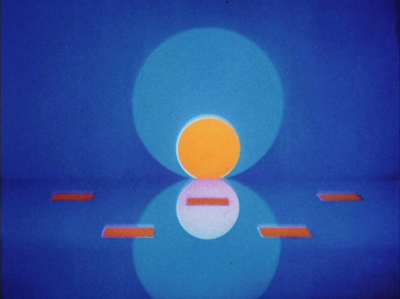

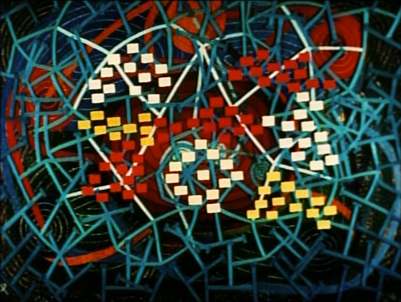

Kreise (Circles, 1934).

Kristin here:

Recently I acquired discs of the work of two important German directors of the silent and early sound periods. The first is a new Blu-ray/DVD edition of Paul Leni’s Waxworks from Flicker Alley. The second is a pair of DVD releases of Oskar Fischinger shorts, which I recently ordered from The Center for Visual Music, co-founded by Fischinger’s daughter Barbara. All are vital for anyone interested in these two major figures in German film history.

Telling scary stories

As with so many cinema classics, I first saw Paul Leni’s Wachsfigurenkabinett (Waxworks) during my grad-school years. The print was 16mm and very dark. It was hard to get any real sense of its pictorial design. I had seen Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari in my first film course and had been hugely intrigued by how different it was from the movies I was used to. It was one of the films that lured me into cinema studies. Since then I have been partial to German silents of the 1920s and especially those of the Expressionist movement. Waxworks was made in 1924, which also saw such high points of the decade as Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen, F. W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, and Carl Dreyer’s second German-made film, Michael. Still, the poor print did not give much sense of how it fit into the creative trends of the mid-1920s. Later I saw it in a 35mm archival print on a flat-bed viewer. That print was also too dark to allow a judgment of its aesthetic and historic importance.

At last, however, a restoration by the Deutsche Kinemathek and the Cineteca di Bologna (released on combination Blu-ray and DVD by Flicker Alley in the USA, from the British Eureka! print) has revealed the set design and impressively bold lighting that suggest why it is considered one of the classics of the Expressionist movement.

While Expressionist stage plays had tended to use stylized settings and acting to create frantic denunciations of contemporary politics and society, German Expressionist films usually remained within popular genres. Horror, fantasy, and science fiction could justify the distortions of the sets as ways of creating strange, often menacing worlds. Waxworks fits right into the horror genre. Set in a carnival sideshow booth, the frame story sets up the premise of the proprietor hiring a young man to write publicity tales about three wax figures of monstrous figures from history and legend: Caliph Haroun-al-Raschid, Ivan the Terrible, and Jack the Ripper. We see the three tales played out as the hero writes them.

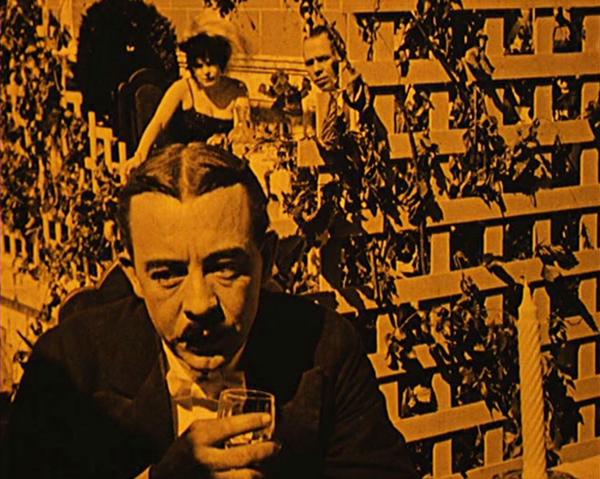

The villains are played by Emil Jannings (see bottom), Conrad Veidt, and Werner Krauss, three top male stars of the era. They do not, however, appear together, since their stories are self-contained vignettes. The narrative returns between the imbedded stories to the table where the young man writes and a romance quickly blooms between him and the sideshow owner’s daughter. The two actors playing them, Wilhelm Dieterle (later to have a career as a director in Hollywood as William Dieterle) and Olga Belajeff, appear as the central victimized couple in each inner tale.

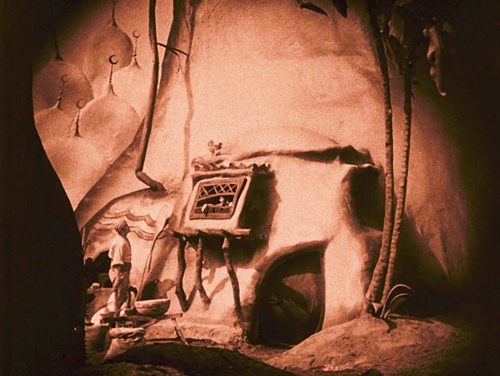

A different style is used for each of these three tales. The first story (in this print, at least) tells of Haroun trying to seduce the beautiful wife of a Baghdad baker. The settings are of the melting-clay variety familiar from Der Golem and Kriemhild’s Revenge. The image at the top of this section shows the baker’s home, with its sagging doorway and artificial trees. The image below displays a typical technique of designing sets to echo the shapes of the actors, as the doorway in the rear imitates Haroun’s blobby outline in the foreground.

The Ivan the Terrible episode comes next, maintaining the blobby look, but with more solid-looking, often symmetrical sets. Here Ivan emerges from his palace.

The brief third episode has suspenseful visions of Jack the Ripper pursuing the couple in nightmare fashion, with multiple superimpositions of the implacable killer.

Apart from these techniques, the improved visual quality of the film reveals a dark style of lighting that helps explain where the influences on Hollywood film noir came from. The opening of the frame story takes place at night, and a chiaroscuro look is established with a sophisticated use of Hollywood’s three-point lighting, which had only reached Germany a few years earlier.

There are some other daring uses of foreground silhouettes, as when the jealous baker watches his wife move away into darkness (left) or Ivan’s poison-maker realizes that he has been doomed to die (right).

These are only a few of the many frame-grabs I made while watching this visually dramatic print. I could post many more, but I’ll end with this interesting comparison that I noticed. On the left, a shot from the Haroun episode as he plays chess with courtiers, and on the right, an interior of the house where the Woman from the City is lodging in Murnau’s Sunrise (1927).

The Waxworks we see today is not the original German version. The original negative was lost in a Paris customs-house fire in 1925. The most complete surviving version was the one released in the UK in 1926. Where it was deteriorated, footage from other surviving release prints was substituted. This English version was about 25 minutes shorter than the German one, with the footage removed mainly from the frame story and from the exposition about the wedding of the young couple in the Ivan episode. The premiere of the film in Berlin had the stories in a different order: Ivan, then Jack, than Haroun. Possibly this aimed at a more cheerful ending for the film, but the order was changed shortly thereafter, presumably to that of the British and other release versions.

The severe hyperinflation in Germany in the mid-1920s led to financial problems, and these curtailed the shooting of the film. One intended episode about Rinaldo Rinaldini, a fictional “Robber Captain,” was never shot, though the wax figure of Rinaldini is clearly visible in the sideshow lineup of miscreants. The Jack the Ripper story was never shot in full, though the shapeless nightmare sequence was shot without benefit of script. It ends up as a short but frightening climax to the film. As a result of all this, the Haroun episode is fairly lengthy, the Ivan one less so, and the Jack the Ripper one brief but memorable. Essentially what we have is a restoration of the British version.

The restored version uses the intertitles from the British print, as the German ones have not survived, and the tinting and toning are also based on the British print. The accompanying booklet has an essay on the history of the film and its versions by Richard Combs, a sketch of Leni’s career by Philip Kemp, and a description of the restoration by Julia Wallmüller. Adrian Martin contributes the insightful commentary. One charming extra is a short, Rebus-Film Nr. 1 (1926), part of a series of eight brief crossword-puzzles that audiences could play along with in the program of short subjects before the feature. These included animations and experimental montage-style superimpositions done by the brilliant German cinematographer Guido Seeber. I got all the answers right. Could you? (Actually, they’re very easy, as they would have to be in a theatrical situation.) The Blu-ray is regions A, B, and C. For more technical and historical background on the film, see Jan Christopher-Horak’s review of the Flicker Alley release. (It’s entry number 260; you’ll need to scroll down to find it.)

Leni continued on in the horror mode late in his career in Hollywood, making The Cat and the Canary (1927), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and The Last Warning (1928), all at Universal. These, along with the various films of Lon Chaney, notably The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1922) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), built the foundation for Universal’s famous horror films of the 1930s.

The Visual Music of Oskar Fischinger

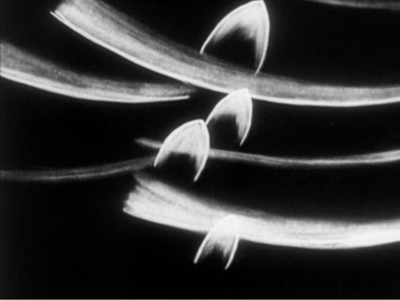

In my recent year-end entry “The Ten Best Films of … 1930,” I included Oskar Fischinger’s series of “Studies” from that year: short films of white shapes (drawn in charcoal on white paper and shown in negative) zipping around the screen in time to musical pieces. These run from Study No. 2 to Study No. 7, though others numbered up to 12 were made in 1931-32. Study No. 4 is apparently lost, and No. 1 is listed on the Fischinger Archive website (linked below) as having been accompanied by live organ music and never released on home video, while the subsequent ones were done with recorded music.

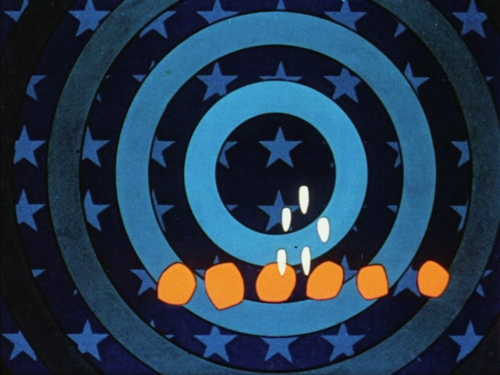

In that entry I linked to the Center for Visual Music as the sole source of two DVDs collecting Fischinger’s work. (I have discovered one other source. See the end of this entry.) At the time I had ordered them, and they subsequently have arrived. It was a great pleasure to sit down and watch both straight through. The films are delightful and lift the spirits. My viewing was on Inauguration Day, when my spirits were already quite lifted, and Fischinger’s An American March (1941), set to Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (above), was especially cheering on a day when our country got rid of a fake president and welcomed a real one.

Although Fischinger used both popular and classical pieces, he retained a similar, recognizable style for both. The black-and-white films were relatively simple, as in Study No. 6.

Like his contemporary, New Zealand animator Len Lye, Fischinger adopted color early and used the soft but extraordinarily vibrant Gaspar Color system. Most of his films of the 1930s employed it, as in Circles (at top) and Composition in Blue (1935).

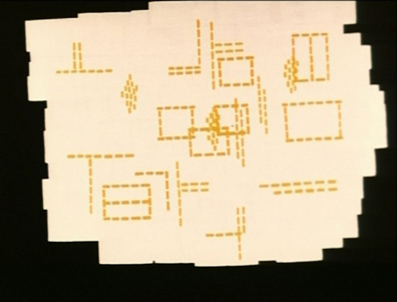

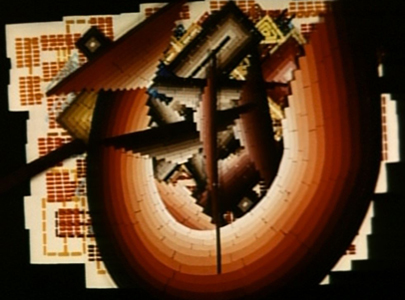

His masterpiece, at least in my opinion, is his last significant film, Motion Painting No. 1. It is his longest film at eleven minutes and is set to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3. It also departs from his usual modes of animation. Rather than substituting a new drawing or moving abstract shapes in space slightly between exposures, he added a brushstroke per frame, creating a continuously moving line that gradually created a series of compositions that changed the image completely as the line proceeded relentlessly and obliterated what went before. Thus across the film there is no pause in the line’s movement as it paints over its earlier progression. Here are some of the stages of its mutations. (Spoiler alert!)

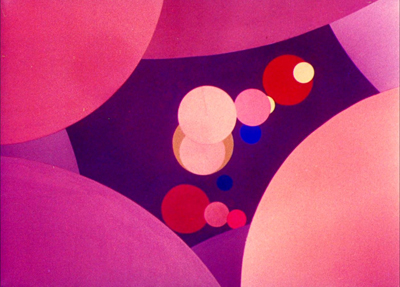

While these two discs contain nearly all of Fischinger’s important films, a conspicuous absence is An Optical Poem, which is an abstract animation of the usual sort made by Fischinger but for a major studio. MGM produced it as one of the seven-minute cartoons that were shown among the shorts in movie-theater programs for decades. Set to Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody Number 2,” it’s typical Fischinger, with lively colored discs and other shapes darting around. The main difference is that here he was working in Technicolor. As smaller discs pass behind larger ones, a distinct sense of depth is often achieved.

The reason for An Optical Poem‘s absence from the CVM discs is presumably because it is the only Fischinger film not controlled by the Estate. Fortunately the gap has been filled by its inclusion in Flicker Alley’s set, “Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970,” which I reviewed when it was released in 2015. Flicker Alley obtained permission from Warner Bros. and Turner Entertainment, which now control MGM’s library. This allowed them to include the original MGM logo and title, plus an introductory opening text that tries to prepare the audience for what’s to come. (These are missing from the prints posted online.)

Between the two CVM discs and the Flicker Alley set, we now have good copies of all but some minor, often unfinished works by Fischinger. The CVM discs do not contain much in the way of supplements, but one can get much more information from William Moritz’s Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger (2004). More information, including a bibliography of books and articles on the filmmaker, can be found on the website of CVM’s Fischinger Archive. Fischinger died in 1967, and several years later his wife Elfriede sent a collection of his equipment and the material used in his animated films to the Deutsches Filminstitut in Frankfurt. This collection included the plexiglass sheets upon which Motion Painting No. 1 was created.

Thanks to Lee Tsiantis for a correction to the Oskar Fischinger section!

January 27, 2021. Thanks to Cindy Keefer of the Center for Visual Music for providing some additional information on the availability of Fischinger’s films. A number of art museums and specialty bookshops have sold the CVM DVDs in the past. The only place that is still doing so, as far as I can tell, is Walther Koenig‘s fine bookshop in Berlin. The CVM also has some excerpts and complete films on their Vimeo channel.

When John was Jack: Ford’s early westerns rescued

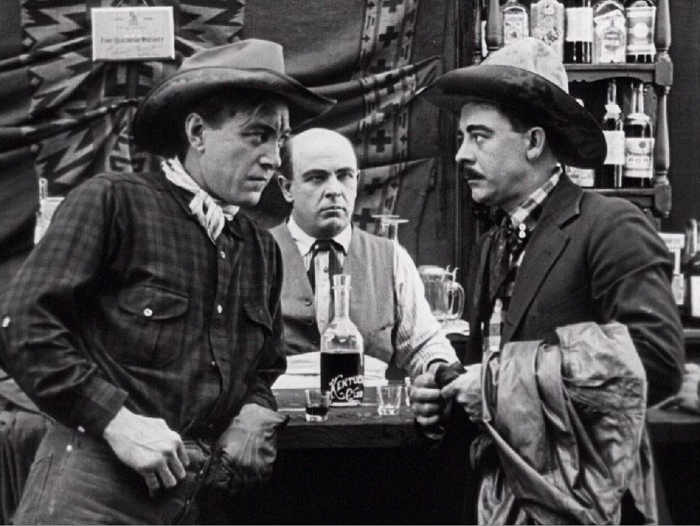

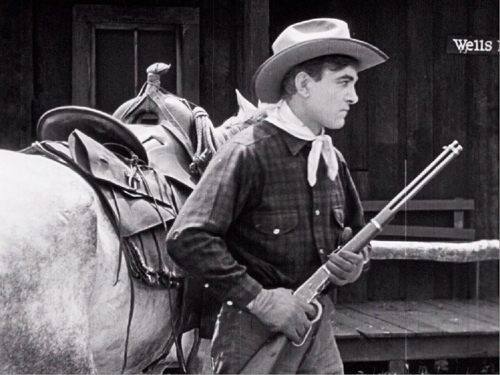

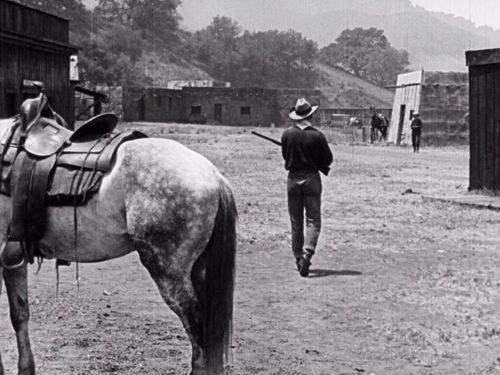

Straight Shooting (1917).

Kristin here–

Recently I received a most welcome message from cinephile extraordinaire Michael Campi, whom David first met at the 1995 Hong Kong Film Festival and with whom we have shared many a meal at subsequent festivals on three continents. His smiling face has shown up often across the history of this blog, most recently here. Michael was alerting me to the existence of a Blu-ray edition of John (aka Jack) Ford’s Hell Bent (1918). Kino Lorber released it on August 25, and as I discovered upon investigation, it had released a Blu-ray of Straight Shooting (1917) on July 14. A third feature, Bucking Broadway (1917) also survives, albeit in somewhat truncated form. (See below.)

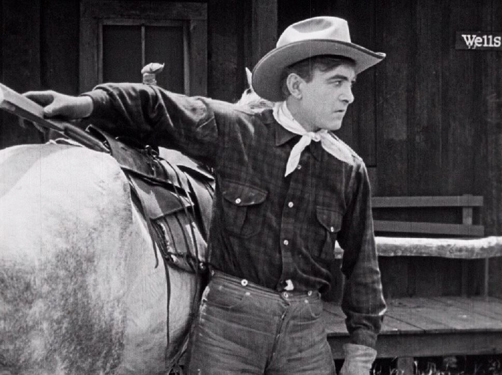

Jack Ford, as he signed his films up to 1923, had made five two-reel westerns in 1917 before his first feature, Straight Shooting, followed by three other features that year. Harry Carey’s character, Cheyenne Harry, was popular, and Universal was clearly happy to have Ford crank out five-reelers starring Carey. (Stories of how Ford supposedly tricked Universal into “letting” him make a feature strike me as having been concocted well after the fact.) Cheyenne Harry was Carey’s main persona, but these features were not a series or serial. Carey is a different Harry each time, winning and marrying different women. When he departed from his good-bad man character, he took a different name, as with upstanding cowboy Buck in Bucking Broadway.

Even across these three films, the plots seem fairly formulaic, but the execution already displays considerable stylistic and technical sophistication. Ford had already mastered the continuity guidelines that had gelled over the previous years. Most of his films were shot in direct or diffused daylight, but he knew how to create an effective chiaroscuro with artificial light when a scene called for it. He often staged in depth to a degree that was unusual in that period. Particularly in Hell Bent he creates flashy scenes to show off his mastery of the cinema.

Both films survived only at the Národní filmovy archiv in the Czech Republic. (Go here for a remarkable list of major international classic films which have survived only because there were unique prints of them in this archive.) That chance survival is very lucky for us. Ford is credited with making 32 films from 1917 to 1919 (fifteen in 1919 alone, though some were shorts). Only three survive in anything close to complete form, and a few brief scraps have come down to us as well. These new releases and an earlier one make all three available in the best prints out there.

Straight Shooting

Straight Shooting is the earliest and arguably the best of the three. Its story is tight and develops continually, without the padding noticeable in Hell Bent and Bucking Broadway. The plot of the ranchers trying to drive out the settlers runs through it consistently and holds it tightly together. Straight Shooting also sets the pattern of making a romance line of action prominent in the plot. In both Straight Shooting and Hell Bent Harry begins as a criminal and reforms when he falls for the virtuous heroine. In Bucking Broadway, another common pattern is used. As a cowhand on a ranch, Harry woos and wins the hand of the rancher’s daughter, only to lose her to a slick visitor from the city who persuades her to elope with him to New York. Naturally he turns out to be a scoundrel, and she needs rescuing to return to the little house Harry has built for his bride.

To some extent, these patterns are taking up conventions of William S. Hart’s films, though Harry is a more easygoing, comic character than the solemn, stalwart heroes Hart tended to play.

Already Ford displays his remarkable mastery of the medium. The famous shoot-out scene is handled with an unusual panache. After Harry comes out of a building and sees Fremont riding toward him, he unsheathes his rifle. A reverse shot shows Fremont dismounting and doing the same.

In the same shot, Fremont moves forward, leading to a tighter reverse shot of Harry, waiting.

A tighter reverse shot of Fremont follows, leading to a repetition of the original framing as Harry moves rightward.

The original framing of Fremont is repeated as he responds by moving leftward. A long-shot in depth (emphasized by the placement of the horse in the foreground, shows the two men in the same space, establishing the distance between the two but also setting up the building on the far right that Fremont will duck behind, leading to a cat-and-mouse game that forms the last part of the shoot-out.

A tighter shot-reserve shot places the two men in irises. Harry moves toward the camera.

Fremont moves forward as well and comes even closer to the camera than Harry does; the camera also lingers on his face longer than on Harry’s. These close views of Fremont place considerable emphasis on his fearful expression in comparison with Harry’s determination. This fear sets up the moment when Fremont ducks behind the building.

A cutaway to some onlookers ducking into the alley at the rear builds suspense but also shows that the sheriff is too scared to interfere (as he had been in an earlier scene in the bar).

In the repeated depth framing, the two men walk slowly toward each other. More cutaways show frightened townspeople ducking into hiding. Harry and Fremont walk past each other without firing , which adds an unconventional little twist to the scene, and Fremont suddenly hides behind the building.

Although a high point, the shoot-out is not the only indication that Ford was born to make movies.

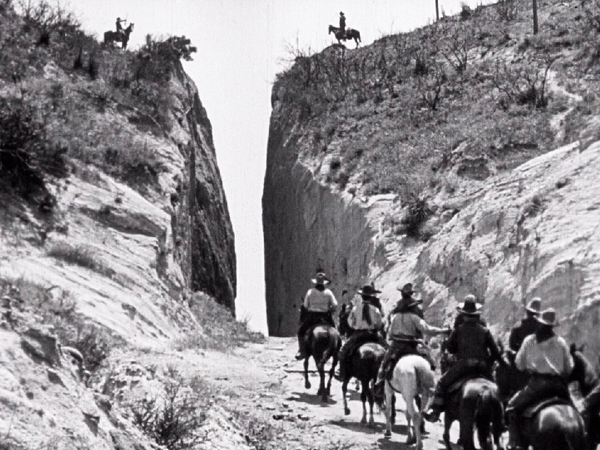

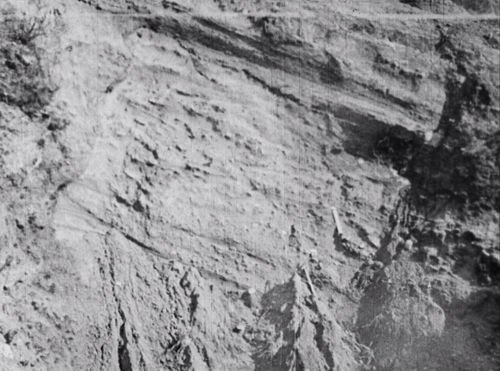

His use of natural locations was distinctive from the start. He may have already been using Beale’s Cut, the narrow passage in the frame at the top of this section, in his short films. (Other filmmakers, such as Keaton, shot there as well. Tag Gallagher’s video essay on the disc runs through a few of them.) This formation appears relatively briefly in Straight Shooting, but Ford used it more extensively in Hell Bent. It may have been the Monument Valley of Ford’s early career.

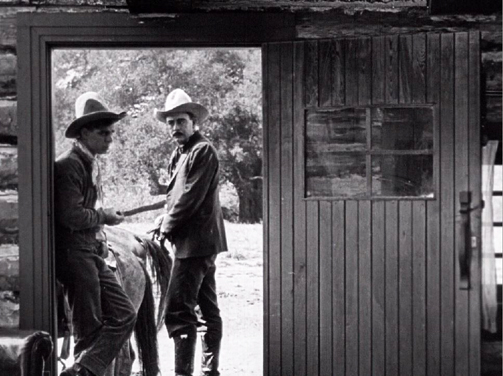

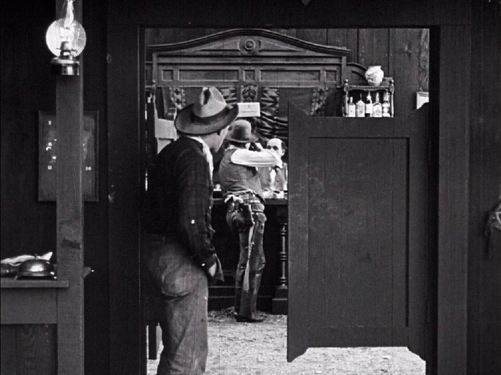

His penchant for doorways has appeared by this early point. On the left, the young cowboy Danny and Fremont pass in the door of the villainous rancher Flint’s house. On the right, the bar doorway is combined with considerable depth as Harry arrives to announce that he is quitting the gang.

Depth is used in natural settings as well. The ranchers’ attack on the farmhouse includes a dramatic composition with horsemen shown in near silhouette against the distant house, visible through a cloud of gunsmoke and dust. At the right, the staging of a meeting in which Flint discusses strategy with his henchmen has the furniture in the foreground, with the placement of the sofa forcing two of the men to face away from the viewer, creating a naturalistic touch. By the way, compare the diffused lighting and set design, with its ceiling beam, with a nighttime scene at the villain’s lair in Hell Bent, below.

Most Ford fans are probably familiar with Straight Shooting, albeit in inferior prints. Before I pass on to the lesser-known Hell Bent, some information about the Kino Lorber version.

According to Tag Gallagher’s essay in the accompanying booklet, the Nederlands Filmmuseum used a copy of the Czech print to create a tinted version. The Museum of Modern Art also made a version from the Czech print; its head title and credits copy the design of Universal intertitles of the period. That print, presumably the one I saw years ago, translated the Czech titles. The Kino Lorber print is a 2016 restoration by Universal, which adopts the MoMA credits but uses title text drawn from an early continuity script of the film. I must agree with Gallagher that the decisions to use those titles and not to tint the print were correct. As the image at the top of this entry shows, the result is a huge improvement on previously available versions.

Apart from this booklet, the supplements also include a brief video essay on Ford’s early career by Gallagher, an audio commentary by Ford scholar Joseph McBride, and a three-minute fragment of Hitchin’ Posts, which is all that is known to survive of Ford’s 1920 film.

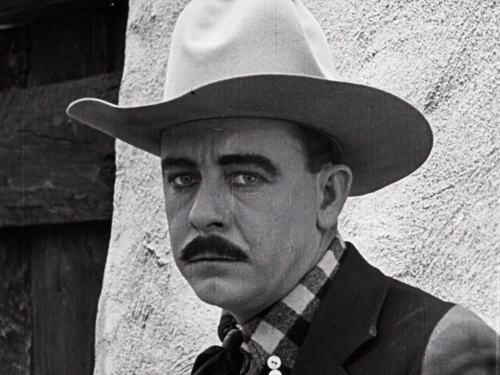

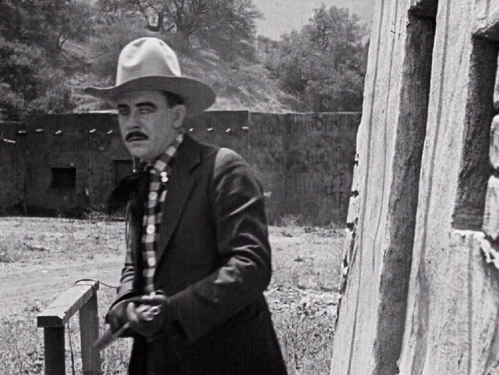

Hell Bent

We first saw Hell Bent when it was screened at “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival in 1988. Although the surviving Czech print was missing over twenty minutes of footage (near the beginning and especially the ending as far as I could tell), it was another impressive revelation of Ford’s very early work. It was also quite worn, more than Straight Shooting, it would seem, since even a comparable restoration by Universal could not quite replicate the visual quality of the Straight Shooting Blu-ray. Still, it is again a big improvement.

The plot of Hell Bent is considerably less well constructed than that of Straight Shooting. Early in the film there is an impressive stagecoach robbery sequence that sets up the criminal gang, led by Beau Ross, that Harry is initially linked to as a sometime hit-man. The robbery in fact fails, as the expected Wells Fargo cash-box has been secretly sent by by wagon taking a different route. Nothing comes of that immediately.

The opening of the robbery scene displays Ford’s expertise in both editing and dramatic cinematography. The scene begins with the gang high on a hill looking off expectantly. A POV long shot reveals a stagecoach passing below.

The group turn and begin to ride off left. There follows an extreme long shot of a winding road with the stage moving up the lower part of the road.

We see the bandits riding rapidly down a steep slope. Finally the stagecoach is seen in the same framing as before, now further along, and moments later the gang appear at the upper right around the bend, galloping to intercept the coach.

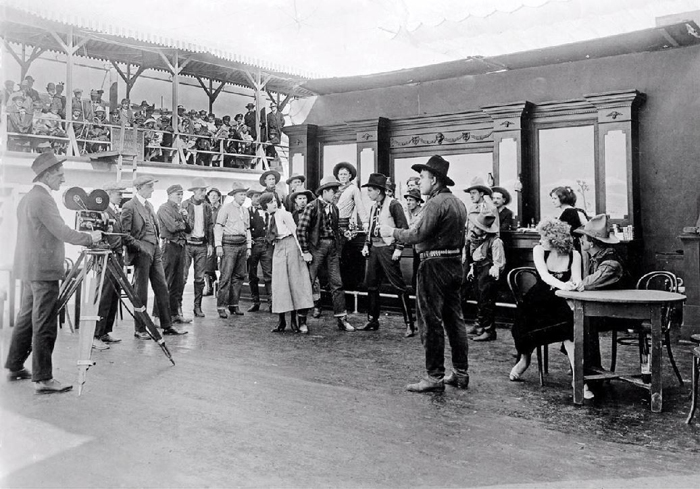

After the failure of the robbery, there is little plot development in the first half of the film. There’s a long comic scene as Harry arrives in town and finds all the beds in the local saloon/dance hall occupied. He rides his horse up to the room with a single occupant who has refused to share his bed. Harry demands that he do so, and the two take turns forcing each other to jump from the window until they end up drinking together and becoming chums. (The bar here may well be the same set as that in Straight Shooting redressed. Bars apparently played a large role in Ford’s films, not only in these scenes but also in the production still at the bottom of this entry.) Teaming up with another cowboy gains Harry an ally in later in the action, but their initial encounter is quite drawn out.

As in Straight Shooting, Harry falls in love and reforms. (We witness the process of him contemplating the benefits of a settled domestic life in the close-up at the top of this section.) The second half becomes more goal-driven, with Harry leading the effort to defeat Ross’s gang.

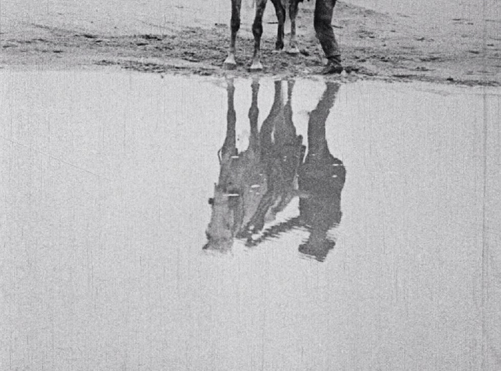

There is no sustained action that is as flashy as the gunfight in Straight Shooting. Still, Ford seems even more determined to flaunt his prowess as a director. He gives us our first view of our hero as a reflection in a pond. He shows horsemen as shadows in a shot that prefigures a similar device in the Indian attack in The Iron Horse (1924).

The beginning of the climactic attack on the stagecoach begins with Ross signaling to his men on distant hilltops to converge. This is handled with excellent graphic matches of Ross, his henchman, and back to Ross. A short time before, as the gang rides out of town, they are filmed so that the horses gallop toward and jump over the camera.

Most of the interiors were shot on stages at Universal with muslin diffusers draped overhead to create an even, overall light. The image at the bottom of today’s entry shows this setup for another Harry Carey film by Ford. Incidentally, it also shows an audience watching the filming. Ford again creates chiaroscuro, this time more elaborately, for Ross’s house. There is a ceiling of log beams with something over them to block out the light. The distant room is lit more brightly than the foreground one, which is lit only by a fire (presumably simulated with one or more arcs) in the left foreground. For some of the more static exteriors, Ford has the camera shooting obliquely toward the sun, creating considerable modeling on the characters.

Although, as I said, there is no big final scene, there is a jaw-dropping shot during the gang’s pursuit of the stagecoach in the climactic sequence that demonstrates how thoroughly Ford had already grasped the powers of mise-en-scene and the camera. Although the scenery looks quite different from that of the high-angle extreme-long shot of the winding road earlier, I’m fairly sure that this is the same road, shot from a different vantage point, more or less where the gang had been waiting in the earlier scene. If not, it is certainly somewhere similar nearby, with a hairpin road on the side of a mountain.

The stage initially comes forward from the distance at the upper left (the area where the gang had come from when they appeared in the final shot of the sequence reproduced above). As the horses round the curve and race down toward the right, the coach breaks lose and begins to fall over the edge.

The camera tilts to follow it, but after it falls out of sight at the bottom, the tilting movement pauses, not continuing with it until it crashes offscreen.

After this pause, the tilt resumes, revealing the crushed coach at the bottom of the cliff. The reason for the pause in the tilt becomes apparent: offscreen the horses have rounded a bend and now come unexpectedly racing through the shot, past the coach. The camera had paused, waiting for the timing to be just right to catch them. I believe that someone who could figure out the logistics of that action and that camera movement had a pretty good feeling for cinema from very early on.

In addition to this dramatic mountain road, Ford uses Beale’s Cut in multiple scenes, making it the location of the gang’s hide-out.

Hell Bent was also restored by Universal from the Czech print. There’s no booklet with this one, but Gallagher again provides a second, different brief video essay. The other supplements consist of another commentary by Joseph McBride, as well as a 1970 interview he did with Ford.

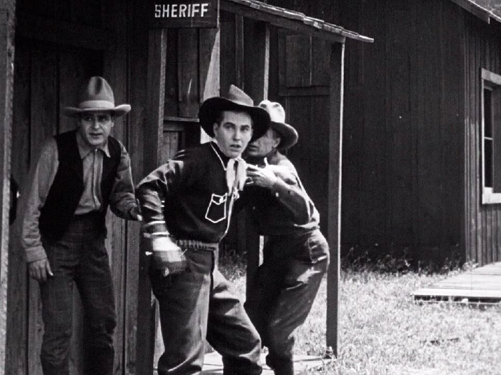

Bucking Broadway

Watching the two Kino Lorber releases, I was reminded that a third Ford feature of this era also survives–though, like Hell Bent, it is missing footage, probably about the same amount, given the running lengths. Bucking Broadway was one of eight features by Ford released in 1918. His ninth feature, it also stars Harry Carey, this time as Buck. The plot is thin, with Harry as a cowhand who falls for the rancher’s daughter and is given his blessing to marry her. She elopes with a man from the city, who does intend to marry her but turns out to be a drunkard and lout. Harry and his cowboy friends come to New York and rescue her.

Even more than Hell Bent, the film seems like a two-reeler stretched to five. Harry’s engagement party involves a comically maudlin scene the cowboys picking out “Home, Sweet Home” on a piano and bursting into tears as they sing along. The final rescue and fight are expanded to create some comedy about cowboys riding their horses through the city, and the final brawl seems barely staged and way too long.

Nevertheless, there are flashes of Ford’s skill at intervals, with his door motif recurring as a site for the rancher to mourn his daughter’s departure and a scene by a fireplace using the stark low-key lighting popularized by The Cheat three years before.

There are plenty of depth shots like this one, as the cowboy in the foreground calls the others to gather and we see three of them in the distance. See the top of this section for an unusually flashy depth shot as two friends of Buck watch the villain getting drunk in the close foreground.

There are none of the virtuoso treatments of editing, landscape, and camera movement that characterize the other two films of this era, but any Ford completist will want it. After all, it comes as a supplement to The Criterion Collection’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of Stagecoach. It includes a charming musical accompaniment by Donald Sosin, whose piano and violin playing (often simultaneously!) has enlivened many an Il Cinema Ritrovato screening.

The photograph below was borrowed from Tag Gallagher’s video-essay supplement on the Hell Bent disc.

Beale’s Cut is not a natural formation. As the name suggests, it is a man-made passageway created in the 1850s and 1860s as a convenient route into and out of nearby Santa Clarita (just north of the San Fernando Valley). It still exists, though comments on Google Maps suggest that, being located on land belonging to an oil finery, it is fenced off, partially collapsed, and full of trash. For a brief account of its sad decline, see here. There are many historical photos of it online.

Shooting an unidentified Ford-Carey movie at Universal City’s stages.

Auteurs by the hour: The Walker Art Center Dialogues

DB:

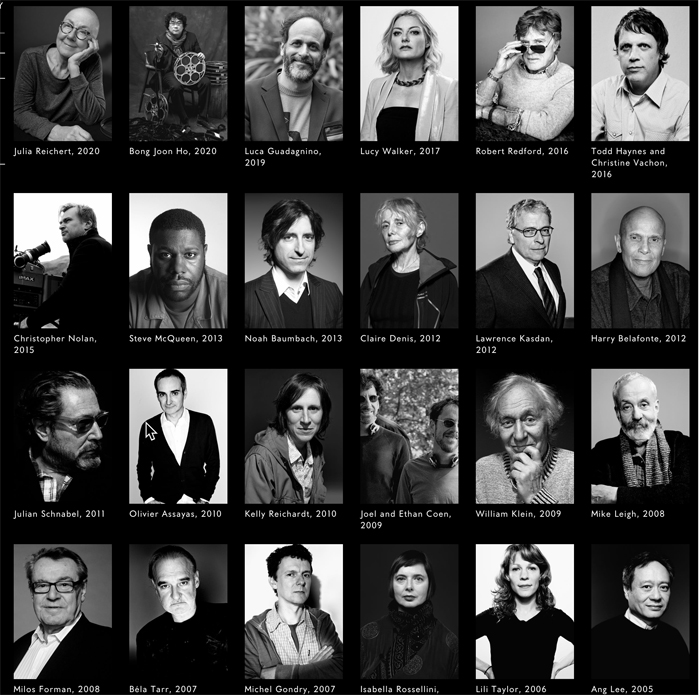

For decades, the world’s top filmmakers have made pilgrimages to the splendid Walker Art Center of Minneapolis. A series of astute curators of film provided a keen public with in-depth conversations about cinema. Now, suitable for a podcast-friendly era, the Center has given the world precious recordings of those discussions. The talent on display is overwhelming. Here’s just the half of it.

Some dialogues are audio only, but many are carefully mounted videos, with stills and clips. The questioners have been chosen from the ranks of archivists, programmers, critics, and academics. (I did one with Altman in 1992.) There are also written transcripts available for download.

In all, this should provide cinephiles with a rich array of ideas and information for years to come: Film history on the hoof. Thank you, Walker demi-gods, for reminding us that the Internet can be benign.

DB and KT with Robert Altman, Walker Art Center 1992.

Back on the book beat

Phoenix (Christian Petzold, 2014).

DB here:

One of my undergrad professors told me: “Bordwell, you have to decide whether you’re going to be a reading man or a writing man.” Professors of the male persuasion talked that way then. When I said I wanted to be both, my mentor puffed his pipe. He really smoked a pipe. He said: “It’s damn hard.” This kindly man knew English Renaissance drama and poetry practically by heart but never wrote a book.

I start to see what he means. For some decades, I managed to read a fair lot and write a decent amount. You’d think in retirement it would get easier. But I have too many interests and projects, and publishers dump a heap of intriguing items on the market every week. The months go by, the books pile up on the side table and on the floor, and I try to keep up. I really do. I’m always behind.

So at intervals I stop obsessing about 1910s cinema and 1940s Hollywood and Rex Stout and how best to think about film form and style, and I swerve to what colleagues are discovering. Turns out, quite a bit. What better time than a plague to catch up?

Flooding the zone

What’s it like to live across the street from a prolific polymath?

For twenty-five years we had as neighbor James W. Cortada, a genuine intellectual range rider. Trained as a scholar in Spanish diplomatic history, he finished his Ph.D. in one of the worst hiring years: 1973, the same year I came out. I was lucky to find work, but Jim took a job selling IBM computers. Eventually he became an executive specializing in innovation and management.

But he was also a compulsive researcher and writer. While holding down a desk job and supervising staff and toting PowerPoints around the world, he managed to publish books in a host of areas. He was a guru of Total Quality Management, producing books and yearbooks on the subject. He also became a premiere historian of computer technology, with such classics as Before the Computer. What I like about this book is the way it integrates study of the tools and machines with examination of the office-based practices of sorting, bookkeeping, and other mundane activities. Unbelievably, Jim continued his graduate interest in Spanish political history. Along the way he wrote a research manual (History Hunting), turned out a study of 9/11’s impact on business, and edited with Alfred Chandler a massive book on information in US life.

Jim writes any size. He has produced The Digital Hand, a magisterial trilogy surveying the use of computers in American life. What about the rest of the world? That’s covered in The Digital Flood, another showstopper. Then there’s IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon, which is the definitive account of a corporate behemoth, with access to information only an insider could obtain.

Not to mention (so I’ll mention it), Jim’s more or less single-handed creation of a whole discipline: the history of information. The ideas are there in early works, but the first crystallization was the stupendous All the Facts, a sweeping survey of how Americans passed along data–not just in business but in cookbooks, diaries, maps, and other vessels of knowledge.

Since 1971 Jim has authored or edited over seventy books. Retirement has revealed what a slacker he was before. Between March 2019 and March 2020, he published four volumes. He also found time to head our neighborhood association, contribute many articles to professional journals, play with his grandkids, and banter over burritos at El Pastor (before lockdown).

You haven’t lived until your neighbor drops by at the cocktail hour with the cheerful greeting, “How many words did you write today?” Fortunately, he’s utterly generous. Jim reads everything I show him, immediately giving me helpful advice. He’s just an all-around intellectual who, because of the 70s job market, wound up in a non-academic line of work. He shows what you can do if you have brains, pluck, and a hunger to find things out. Long before our millennial “knowledge workers,” he showed what a rigorous university education could bring to corporate culture.

Probably the most immediately significant items in Jim’s recent output are two books he wrote with William Aspray. From Urban Legends to Political Fact-Checking: Online Scrutiny in America, 1990–2015 is a scrupulous in-depth account of how fake facts and the debunking of same stretch back to the very origins of the Net. The book digs back to pre-Internet online legends circulated on Prodigy and America On Line, chief among them being the infamous Willie Lynch letter purporting to instruct planters how to discipline their slaves. The bulk of the book shows how over twenty-five years, rumors and half-truths become depressingly long-lived.

In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need.

In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need.

Fake News Nation: The Long History of Lies and Misrepresentation in America is broader and aimed at a more popular audience. It offers eight historical episodes as case studies in rumor and deceit. The earliest instance is the presidential election of 1828, which blended corruption, sex, and racism in an intoxicating cocktail: “General Jackson’s mother was a COMMON PROSTITUTE. . . . She afterwards married a MULATTO MAN, with whom she had several children, of which member General JACKSON is one!!!” Nice to know triple exclamation points aren’t an invention of tweens and trolls. The book surveys conspiracy theories around the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy, mythmaking in the Spanish-American War, and disinformation in controversies about Big Tobacco and climate change. It’s a completely fascinating read.

It’s also fairly dispiriting. It brings out the Mencken in me, admittedly never far from the surface. The books suggest that the venality of hoaxers, the credulity of the multitude, and the social incentives to hide the truth and spread lies don’t promote a public demand for accuracy and nuance. What we see now, in the Republicans’ current attempt at a fascist takeover of our civil society, is the implementation of Steve Bannon’s suggestion to “flood the zone with shit.”

It’s not that the wacko alternatives carry much weight, though they do play to darker desires. More important is the sheer firehose fusillade of preposterous claims. Who can keep up? Nuanced fact-checking seems only to add to the swirl of uncertainty. Are coronavirus cases being undercounted? Overcounted? Confusion and overload are central to the plan. Instead of “Drain the Swamp,” the motto is “Swamp the Drain.”

So books like Jim’s and Mr. Aspray’s buoy us as we paddle to keep our heads above the waves of sludge. Meanwhile, Jim is eight chapters into his next opus.

Techbeat

Jim’s work as a historian of business technology reminds us that tech is a part of film history too. But for many decades, materials, machines, and tools weren’t sufficiently reckoned into the study of film. Scholars of early cinema were, I think, the first to examine the standardization of equipment and film stock; Gordon Hendricks’ dauting Edison Motion Picture Myth (1962) situated the emergence of moving-image technology in the context of Edison’s corporate strategy. Eventually, by the 1980s, people were considering the role of camera and lens design, lighting rigs, film stock, and camera carriages in shaping film style. Our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema was one effort in this direction.

Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available.

Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available.

His analyses of scenes from 1930s and 1940s films, both classic and obscure, train the reader in what to watch for. In all, it’s a persuasive meshing of functional explanations of style with causal accounts of what goes on behind the scenes–not least, the sheer sweat of pushing dollies and following focus. He draws an enlightening contrast with the brain-work of producers, screenwriters, and directors.

The work of production is bodily. The actors move their arms and legs and torsos, and the grip and operator move theirs. Each must anticipate the others’ gestures, like dancers in an ensemble. the Hollywood studio system relied on preproduction planning in order to rationalize production, but the process of filmmaking ultimately came down to craftspeople working together in the moment. One type of collaporation was corporate; the other was corporeal (158).

A graduate of our program, Keating carries forward our respect for filmmaking craft, including its more toilsome routines.

No less sensitive to the concrete demands of technology, and the ingenious workarounds that can be discovered, is Charles O’Brien’s account of the international transition to talkies, Movies, Songs, and Electric Sounds: Translatlantic Trends. Like Keating, he’s studying a body of conventions, here those that arose in the vogue for the international “song film” in 1928-1934. And like Keating, he’s very precise. He measuresg average shot lengths and brings out the implications of how much time is devoted to songs or dialogue.

But this is no simple data dump. O’Brien charts the various strategies in which song sequences allude to the theatre situation and absorb themselves into the ongoing story line. He traces a distinction between the Hollywood song sequences, which were quickly relegated to farces like the Marx Brothers films, and the European sequences, which adapted more varied forms, such as pantomime and verse-like dialogue stretches. The latter strategy was especially common in Germany, partly due to the studios’ commitment to direct sound. O’Brien offers a particularly cogent account of the virtuoso carriage scene in The Congress Dances (1931), which in its joyful excess remains stunning today. (See clip above.)

O’Brien further contextualizes his discoveries by considering broader business culture, such as the market in song recordings and sheet music. All in all, a tight, coherent account of how technological change introduces both functional equivalents of existing techniques and spillover effects–unexpected advantages that artists can exploit.

Shawn VanCour’s Making Radio: Early Radio Production and the Rise of Modern Sound Culture focuses similarly on technology and craft at this period, bringing in other institutional pressures on craft workers making audio artifacts. In fascinating detail, Shawn (another UW alumnus) shows how the separation of body and voice created by radio broadcasts posed many problems for engineers, writers, and other staff. One result was a sort of “practical theory,” a body of ideas about what radio essentially was, alongside particular practices that shaped both technology and dramaturgy.

For instance, everybody recognized the need to dramatize story action with sound effects and music, but paramount was the need to keep dialogue clear. The compromises and trade-offs were debated in trade journals and executed on the airwaves, with fascinating effects on standards of proper audibility. One consequence was the valorization of a “radio voice,” the mellifluous tones suited to the new medium’s demands, both technical and institutional. VanCour shows that these debates were picked up in the motion-picture industry at the period O’Brien investigates. Sometimes, less often than we think, inquiries do converge in fruitful ways.

At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship.

At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship.

This is an encyclopedia that reads like a series of engaging art history lectures. In his opening, Paolo acknowledges the avalanche of new material he faced. More than fifty thousand features and shorts have survived from the years 1894 to 1929, and research has expanded accordingly. He pursues three questions: What was silent cinema thought to be at the time? How may we study it? And why does silent film matter as an expression of culture? These questions are pursued in fifteen chapters bearing one-word titles like “People,” “Building,” “Duplicates.”

No summary can do justice to the world that this book opens up. We learn about the machines, the venues, the processes, and the people. There are floorplans of studios and theatres, comparisons of different color processes (gorgeous), and discussions of how projectionists regulated the speed of the show. The book devotes a whole chapter to theatre acoustics, the use of sound effects and recordings, and even the clapper sticks used by the benshi commentators in Japan. Another fascinating chapter traces the fate of a single film through multiple versions, from camera negative to digital format. Throughout, Méliès’s Trip to the Moon is used as a benchmark to remind us of all the ways that every copy is a unique artifact, a claim that Paolo has advanced consistently over the years.

Silent Cinema is a must-have book for everyone interested in cinema of all eras. Its publication price made it the film-book bargain of the year, but Bloomsbury and Amazon are now offering it on obscenely generous terms. If you’re not a silent fan, this giddy ride can make you one.

Auteurs never went away

The Headless Woman (2008).

At intervals people tell us that we need to stop studying directors and turn instead to Culture or Other Collaborators or some other inputs. Surely the classic formulations of auteur criticism have some problems. Still, it’s terribly hard to shake the idea that a great many films are usefully understood in light of directors’ purposes and plans. Directors play a central role in the production process and under certain circumstances are granted the possibility of building a body of work. We can argue about Roy del Ruth or Michael Bay, but not certain “strong filmmakers” who have, as Andrew Sarris put it long ago, personal visions.

An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker.

An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker.

There’s an extensive body of close analysis on Tati, to which Kristin in particular contributed as far back as the 1970s. Malcolm adds to this with some keen studies of framing, sound, and gag structures. What he brings to the table is the way that distinctively modernist conceptions of humor and comedy find their way into this vaudeville-inspired entertainer. From aleatory gags–apparently random synchronizations of noises and movements–to fragmented and incomplete or unconsummated gags, such as the precarious taffy that doesn’t quite plop off its hook, Tati intuitively reawakens the spirit of irrational laughter that inspired avant-gardists.

Malcolm traces Tati’s lineage back to Albert Jarry, Jean Cocteau, and the avant-garde’s fascination with circus and music hall. Other sources were Chaplin, Léger, and René Clair. In a sort of feedback loop, the avant-garde borrowed from slapstick comedy, while Tati’s cinematic transformation of music-hall numbers into decentered, absurd, or perplexing cinematic sequences revives the anarchic spirit of the modernists. His satire of the postwar managed society sought to make us see the world around us from a potentially subversive angle. The dreary vacation routines of M. Hulot’s Holiday and the opaque surfaces and chilly contours of Mon Oncle and Play Time are disrupted by characters who revel in disruption, and a filmmaker who imagines our daily march easily turned into charmingly clumsy dance. Beneath the paving stones, the beach, went a May ’68 slogan. “His was the quintessentially avant-garde project,” writes Malcolm, “of closing the gulf between art and life” (p. 237).

Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan.

Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan.

All the more welcome, then, is Brad Prager’s monograph on Phoenix in the Camden House German Film Classics series. This is an admirable close reading of Petzold’s film, bringing a range of cultural references to bear on the suspenseful story of a woman returning from a death camp to a husband who, it turns out, has his own guilty secret.

Prager skilfully invokes the citations–Vertigo, Siodmak’s work, American noir–and considers how Petzold’s genre affiliations (he often makes politically inflected thrillers) merge with his examination of trauma in German history. It isn’t easy to do justice to the film’s remarkable climax, which I decline to spoil for you, but Prager manages it. This scene is one of the great fake-outs in recent film, I think, and Prager is alive to all its bleak ironies, including the heroine’s rendition of Kurt Weill’s “Speak Low.”

Phoenix (the book) is a model of compact, probing analysis. I’d be happy to have Prager tackle another Petzold, especially one I just saw and much admire, his first feature The State I Am In (Die innere Sicherheit, 2000), which seemed to me to do for Fritz Lang what Phoenix does for Hitchcock. More generally, Petzold has a pictorial exactitude we seldom see nowadays, and he deserves wide-ranging study.

The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year.

The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year.

All the features of a classic auteurism were here (and in The Holy Girl, 2004): persistent themes, distinctive plotting, signature style. These qualities are given full consideration in Gerd Gemünden’s Lucrecia Martel. Gerd has done a thorough job in surveying her career and dissecting the films. He shows that she is especially interested in rendering physical sensation–textures, touch–through evocative images and sounds. Anybody who has seen La ciénaga can’t forget the opening scene’s glimpses of a scummy swimming pool and flaccid necks and groins, let alone the wine and splinters of glass splashed onto a drunken woman’s corrugated chest. The rain in The Headless Woman is no less palpable, while the humid torpor of the colonial outpost in Zama is sticky almost beyond endurance. This tactility makes Martel’s stringent criticism of class inequities even more powerful.

This critical aperçu finds its place in Gerd’s comprehensive account of Martel’s oeuvre. As is usual in the series Contemporary Film Directors (yeah, an auteur title for sure), we get detailed production dossiers, wide-ranging background on literary sources and cultural context of reception, and close studies of the films. There’s also a rich bibliography and an interview with some surprises; for such an elliptical, visually oriented director, Martel claims that oral storytelling is a primary inspiration.

Auteur studies are not what they used to be. Instead of paeans to directorial genius, they can be subtle, wide-ranging discussions of what Eliot called “tradition and the individual talent.” Acknowledging influences, circumstantial pressures, forced choices, opportunities, and the like, our writers can show that some directors still build up films that yield resonant personal expression. Choice within constraints: that’s the story of creativity in all the arts, and the most nuanced auteur accounts can show how that process works in fascinating detail.

Will we still have books as the coronavirus burns its way through our lives? Can publishers survive? Yes, we’re sequestered, and maybe that’s encouraging us to read more; but people will have a lot less money for books. What will entice us to invest in personal libraries?

An encouraging sign is that so many of the books on film here have very fine illustrations, many in color. So thanks to the publishers for understanding that well-reproduced pictures can attract readers as well as document arguments. And Silent Cinema includes a filmography with references to online collections. With books like these, we can correct and expand what my old prof said: You can be a reader and a writer and a viewer. Now we just need time, and safety.

Each of these books represents an integral research project, but all are part of larger research programs too. Jim Cortada’s work is an epic instance, but we find the same trajectory in the film scholars’ careers. As writer, archivist, and filmmaker, Paolo Cherchi Usai has devoted his life to silent cinema. Patrick Keating’s study of camera movement joins his first book on the history of Hollywood lighting. Charles O’Brien has already given us a fine-grained comparison of the conversion to talkies in the US and France. Shawn VanCour is active in archiving sound and is exploring radio’s relation to other acoustic media. Malcolm Turvey’s book on Tati joins his earlier books on avant-garde filmmakers’ conceptions of vision and 1920s modernism in Europe. Petzold’s film is a natural step beyond Brad Prager’s work on Herzog and on visuality in German Romanticism. Gerd Gemünden’s many books include one on German exile cinema and Billy Wilder’s American films.

Kristin’s writings on Tati from the late Seventies are in her Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis.

P.S. 29 May: I just got another volume that chimes with this entry. It’s Marco Abel’s The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School from 2013, and it’s a very comprehensive and in-depth consideration of this important group.

Trafic (Jacques Tati, 1971).