Archive for the 'Film history' Category

A variation on a sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film

Kristin here:

On April 21 a young Spanish film student uploaded his remarkable little film, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 onto Vimeo. There it languished, like so many contributions to the internet, good and bad. In the first four months of its presence on the site, it attracted 17 views.

Then, on August 17, Variation was viewed twice and earned its first “Like.” (One has to be a member of Vimeo to Like a film, so one cannot assume that none of its viewers to that point had enjoyed it.) That first Like, and perhaps both views were by Kevin B. Lee, best known for his many video essays on classic films. (See here for an index; I contributed the commentary for the La roue entry.) Over the next week and a half there were five additional views, four on August 28. I suspect some or all of these last ones were repeat visits by Kevin, since on August 31 he was the first to post an essay on Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 (hereafter Variation), along with some information on its maker, Aitor Gametxo.

The immediate result was a flurry though not a stampede of views: 33 on August 31, along with a second Like; and 15 on September 1, with a third Like. One of those views and the third Like were mine. On September 2, there were 12 views, dwindling to 2 on September 3 and 1 on September 4.

(Among the viewers after the Fandor entry was Evan Davis, University of Wisconsin-Madison film-studies alumnus, who read Lee’s blog, watched the film, and passed the links along to us. Thanks, Evan!)

It’s a pity that more attention has not been paid to this charming, clever, and informative film. Not only would people enjoy it, but it could easily be used as a tool for those teaching, or indeed researching silent cinema. So here’s my bid to help it go viral.

Variation is a found-footage film based on Griffith’s American Biograph one-reeler The Sunbeam, made in December, 1911, and released on March 18, 1912. It is not among the most famous of the nearly 500 one- and two-reelers Griffith directed at AB between 1908 and 1913, but it’s better known than most. In the opening, a sick mother dies, and her little girl, thinking her mother is asleep, goes out into the hallways of their working-class apartment building. She tries to find someone to play with, but everyone rebuffs her until she manages to charm two lonely people, a bachelor and spinster, who live opposite each other on the floor below the child’s home.

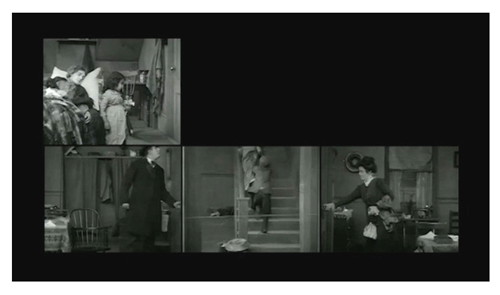

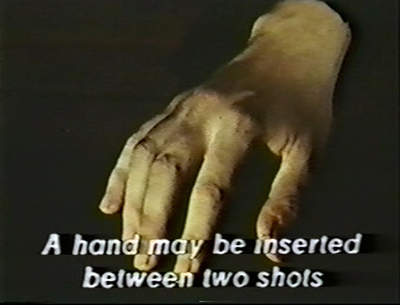

Aitor noticed three key things about the film. First, the action takes place in a very limited space, with the three apartments and hallway all close to each other. Second, the doorways through which the characters pass between these rooms are on the edges of the screen, so that when they exit through the doorway in one shot and after the cut enter the space on the other side of the doorway, there is often a sort of elusive match on action formed (what I termed a “frame cut” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, p. 205 and figures 16.36 and 37). Third, and perhaps most importantly, Griffith was intercutting actions that were happening simultaneously, so that at many of the cuts, he jumped from the end of an action in one space back in time to catch up with what had been happening in another space. At times he would jump back twice if simultaneous actions were happening in three spaces.

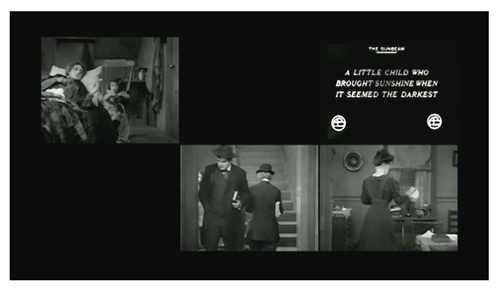

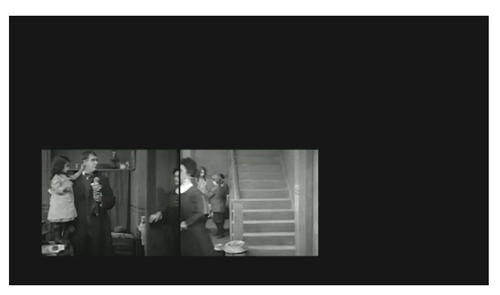

Aitor has taken the individual shots and redone them, putting them into a grid of six small frames, three on the bottom and three at the top. Scenes in the child’s upstairs apartment are shown only in the upper left, the top of the stairway in the upper center, and the two apartments on the ground floor at the sides, with the hallway and bottom of the stairs between them. (See above.) These are roughly the actual positions these spaces occupy in relation to each other in the building represented in the film. The shots run in their true temporal relations, so that there is no jumping back.

I suggest that before reading further, you watch The Sunbeam, especially if you have never seen it before. It would be impossible, I think, to entirely follow the story just from seeing Variation. The shots are so reduced in size to fit into the grid that small but important gestures and details get lost. Here is the original film, from YouTube.

With Aitor’s kind permission, we present his take on Griffith’s one-reeler. (The Sunbeam runs about 15 minutes, but due to the simultaneous presentation of many shots, Variation is only about 10 minutes.) Click on the “Vimeo” logo in the lower right corner for a larger image:

A fascinating film, isn’t it? I think many viewers would reach the end of Variation and wish that the same sort of presentation could be created for other films–at least, early ones that are short enough to make such rearrangement viable. Kevin Lee is enthusiastic about the idea: “Imagine this multi-dimensional, real-time approach being applied to footage from other films, as a way of not just mapping out scenes in a movie, but also gaining insight into filmmaking technique.” It might be possible, but the six-rectangle grid used here would not work for very many films. Aitor has chosen the ideal film for such an approach. Not only are there a limited number of significant characters, but they also live in the same building, with three rooms and a hallway, all viewed from the same direction, making them fit perfectly into a “doll-house” style scene.

Had Griffith not routinely shot directly toward the back wall in all his sets, placing the shots directly side by side across the grid would not work, at least not so neatly. Many other directors of this era were exploring shooting into corners and having doorways for entrances and exits centered at the rear. Perhaps filmmakers like Aitor could still place different shots side by side, but the actors’ movements from one space to another would not be so smooth. One of the attractions of Variation is that those movements are smooth, and as a result the action plays as if it were part of a continuous, “real” film.

Even other Griffith films shot in the style of The Sunbeam would be far more difficult to lay out on a similar grid. Longer rows of more rectangles would need to be added, or the upper row would have to represent actions taking place at a distance and the lower one actions taking place within a building. (I’m thinking here of something like The Lonely Villa, where action in a series of contiguous rooms is intercut with the husband’s race from a distant locale back to his house.) The placement of the bachelor’s room opposite the spinster’s, on either side of the hallway through which all of the minor characters pass, is crucial to Aitor’s project. A complex film with many characters and locales might create a grid with rectangles too small to be grasped by the viewers. Ways of indicating techniques like flashbacks would have to be devised. And of course, not all films contain simultaneous action.

Variation has some technical disadvantages. The titles appear in the upper right corner of the screen, since no locale opposite the child’s apartment is ever shown. The titles are small and difficult to read, and since they pop up simultaneously with the action, it’s almost impossible to read them anyway. One cannot tell where the titles originally came in the flow of shots, though one can always check the original film. Another problem is the cropping of the images on all four sides. The DVD copies are somewhat cropped, and more of the image is eliminated in the Variation frames; the action of the little heroine hiding a hairpiece in the spinster’s home, an important motivation for later action, can barely be grasped because it is so small a detail and happens at the very bottom of the frame; in the DVDs it can be clearly seen.

The Griffith Project and our knowledge of his techniques

I do not intend by any means to diminish what Aitor has accomplished when I say that the three main techniques he works from have been known to Griffith scholars for years. Variation offers a new way of examining and explaining those techniques.

Griffith has, of course, been one of the most closely studied filmmakers in history. A vast summary of and contribution to the research on Griffith was recently compiled by “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” film festival in Pordenone, Italy. From 1997 to 2008, the festival mounted a nearly complete retrospective of Griffith’s work, hampered only by those films which still exist only as negatives or in other forms that could not be projected. A team of experts divided up the work and wrote extensive program notes for every single film Griffith made, whether it was shown at the festival or not. The notes, some more general essays, and Griffith’s writings were edited into twelve volumes jointly published by the festival and the British Film Institute (1999-2008). I had the privilege of contributing notes to most of the volumes, and although I cannot claim to know Griffith’s entire œuvre intimately, I got to know the films assigned to me quite well and learned a great deal about his methods.

The program notes for The Sunbeam were written by Griffith specialist Russell Merritt (Volume 5, 2001). As these excerpts from his description of the film’s setting indicate, the doll-house arrangement of the sets in The Sunbeam were distinctive, but not atypical of Griffith’s approach:

This was the second of Griffith’s three December tenement films (falling between The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls); spatially it is his simplest. Griffith uses only five setups (fewer than half what he works with in The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls.), but far from feeling cramped or monotonous, the three rooms and two hallways spaces seem perfectly designed for the playful romps, the practical jokes, and the unfolding of the gentle love story.

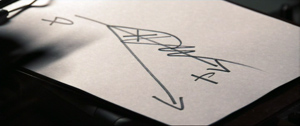

By 1911, the Griffith apartment set had developed a personality of its own, or more precisely, had become both distinctive and flexible enough to accommodate a broad range of narratives. Griffith’s planimetric style, with the camera always aimed straight on into the back wall with at least one side of the room aligned to the margin of the frame, had become as much a Biograph signature as the last-minute rescue, the fade-out, parallel editing, and the stock company of actors [….] In The Sunbeam, the familiar hallway and one-room apartments turn into something resembling a row of a child’s wooden blocks or the rooms in a child’s dollhouse, albeit with a dead mother in the garret. In each space, whether the hallway, the spinster’s apartment or the bachelor’s one-room across the hall, there is something to play with or play upon. The prank with the string stretched across the hallway literally links the two apartments and provides the perfect center of a the film–a gag that depends upon the mirror symmetries of the rooms and the tug-of-war actions of the two incipient sweethearts. (p. 196)

For the prank with the stretched string made symmetrical spatially as well as temporally, see below.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ book Theatre to Film (1997) points out that cutting among multiple adjacent interior rooms was typical of Griffith’s work in this period: “By early [1911] a film like Three Sisters has a climactic sequence of 28 shots alternating between three set-ups–long-shot views of three rooms, a kitchen, a hall, and a bedroom, which movements from room to room that coincide with cuts establish as side by side.” (p. 189) My own notes for The Griffith Project volumes discuss adjacent sets and room-to-room movements using frame cuts. (See the end of this entry for a list.)

Griffith’s use of editing to convey simultaneous events, as well as to portray thoughts and flashbacks has been extensively discussed in the literature on the director.

What is remarkable is that a 22-year-old film student has noticed these devices and found a simple, elegant method to demonstrate what we already knew, but with greater precision and vividness than could be done with prose analysis. To experts, that is what should make Aitor’s film so appealing.

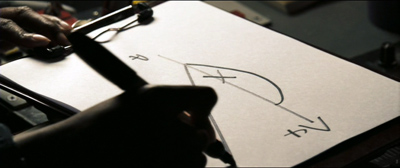

For example, the precision of Griffith’s matches on action at the frame cuts is illustrated time and again in Variation:

Were it not for the fact that Griffith’s camera is closer to the action in the smaller hallway set than it is in the two outer rooms, the spinster’s move through the door would almost appear to be a single smooth glide. Unless one freezes the frame, as I have done here, some of these movements look uncannily continuous.

For those teaching or reading Film Art: An Introduction, Variation also provides a clear example of story time versus plot time. Griffith’s The Sunbeam presents us plot time, with its jumps backward to cover all the action in multiple locales. Aitor’s film presents story action as we ordinarily would reconstruct it only in our minds. Usually we describe story action with synopses or outlines. To see it played out in real time is a rare treat.

The filmmaker

Aitor has a blog, which contains primarily many lovely still photographs taken in Spain, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. It offers, however, minimal information about him. Kevin Lee wrote to ask him for information, which is included in the Fandor entry linked above. I also emailed Aitor with some questions to further contextualize Variation, and he provided a short summary of his background and his interest in Griffith.

My name is Aitor Gametxo. I was born in Bilbao in 1989 and have been living in Lekeitio. I started the Communication and Film degree in the University of the Basque Country, but I moved to the University of Barcelona to finish it this year. I’m currently living and working in Barcelona, and I’m going to do a “Creative Documentary” masters degree this upcoming year. I really enjoy taking pictures of everyday things and places, as a way of reporting reality. I also love film, specially documentaries, found footage films and cinema-essay pieces. I honestly believe in the power films have to make us think about things. Not only because of the topic the film is about, but also about the way in which the film is made (a kind of dialectics between Bill Nichols’ expository and reflexive modes). I love watching old (and odd) films and thinking about things that are different from the purpose they were created for. (As I told Kevin) we are able to take some footage which is temporally and geographically unconnected to us and remodel, or refix, or remix… it, giving birth to another work. This is the way I see the found-footage praxis.

About this particular film, The Sunbeam, I watched it for the first time just before doing the variation. I knew other works made by Griffith, such as “Intolerance” (quoted in several film history books). But this was unknown for me, so that the first watching was crucial. While I was enjoying it, I was wondering what the place where it was shot looked like. I suddenly imagined it as a two-floor house, where the characters cross in some moments. Also the doors were essential to fix one part with another. This was the main idea where I worked on. It was great fun doing it.

The result is this variation in real-time action of the classic work where we can see how Griffith worked on. It’s like returning back to Griffith’s mind, to the first idea, as he imagined one hundred years ago (!) how The Sunbeam would look like. This is the magic of cinema.

My contributions to The Griffith Project‘s program notes for the Biograph years are these. In Volume 2, January-June 1909: Those Boys; The Fascinating Mrs. Francis; Those Awful Hats; The Cord of Life; The Brahma Diamond; Politician’s Love Story; Jones and the Lady Book Agent; His Wife’s Mother; The Golden Louis; and His Ward’s Love. In Volume 3, July-December 1909: Lines of White on a Sullen Sea; In the Watches of the Night; What’s Your Hurry?; Nursing a Viper; The Light That Came; The Restoration. In Volume 4, 1910: A Child’s Faith; The Italian Barber; His Trust; His Trust Fulfilled; The Two Paths; and Three Sisters. In Volume 5, 1911: The Lonedale Operator; The Spanish Gypsy; The Broken Cross; The Chief’s Daughter; A Knight of the Road; and Madame Rex. In Volume 6, 1912: The Unwelcome Guest; The New York Hat; My Hero; and The Burglar’s Dilemma. In Volume 7, 1913: The Hero of Little Italy; The Perfidy of Mary; and A Misunderstood Boy.

Like the other contributors, I found myself dealing with a few famous films (e.g., the wonderful Lines of White on a Sullen Sea) and others that were largely unknown. Each little cluster of titles assigned to us consisted of films that had been made sequentially, so that each of us could get an intensive look into Griffith’s work over the course of a few weeks. It proved to be a rewarding way of approaching the study of the director. The general editor for the series was Paulo Cherchi Usai, assisted by Cindi Rowell.

The Sunbeam is also available in the U.S. in two DVD sets: Image’s “D. W. Griffith: Years of Discovery: 1909-1913” and Kino’s “D. W. Griffith’s Biograph Shorts Special Edition.” (The discs can also be bought separately.)

Ruiz in memoriam: Rules and ruses

Of Great Events and Ordinary People.

DB here:

Last week, Raúl Ruiz died. His death is an enormous loss to world film culture, not least because his penultimate work, Mysteries of Lisbon, brought him a prominence he had been denied throughout his forty-year career. More important, we lost a modest, kindly, and zestful man.

From the mid-1960s through 1975, it seems to me, there emerged an interesting in-between group of filmmakers. By then film festivals had canonized an official art cinema typified by Fellini, Bergman, Wajda, and the New Wave. Now there appeared a more capricious clutch of directors, of varying ages, who pushed in a more avant-garde direction. Many made outstanding short films, like Wenders’ Same Player Shoots Again, or the Straub/ Huillet Not Reconciled, or Akerman’s Hotel Monterey, or the peculiar early efforts of Peter Greenaway.

When they turned to features, this group of directors produced films like October à Madrid (Marcel Hanoun), The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (Straub/ Huillet), Fata Morgana (Herzog), Katzelmacher (Fassbinder), and Jeanne Dielmann (Chantal Akerman)—more rigorous and forbidding than anything attempted by the older generation. In later years some of these talents moved comfortably into the festival niches vacated by senior directors, but for many years most were little known outside a small circle.

If they were marginal to most moviegoers, Ruiz was marginal to them. Exiled from Chile, where he made his first features in his twenties, he moved to France in 1973. There he proceeded to direct over a hundred films, often financed by television, while staging plays and running the Maison de la Culture in Le Havre.

His films’ repute was in inverse proportion to their availability. He was celebrated by critics in France (Cahiers du cinéma took up his cause) and England (particularly by London’s Afterimage group). Ruiz had his fans in North America too, notably Jim Hoberman and David Ehrenstein. But the films were chiefly seen at festivals, and none of his productions of this period, so far as I can tell, found stable distribution, theatrical or nontheatrical, in the United States. In 1989-1990, while Ruiz was teaching at Harvard, a batch of his films was circulated here by the quixotic International Film Circuit.

What set him apart from the other marginals was a devotion to esoterica (philosophical, literary, ecclesiastical), pursued with a sly humor. He remarked that during one screening, he was the only person laughing at his movie. Although like most of his contemporaries his sympathies lay on the left, he didn’t seem to take himself seriously, and this put him at a disadvantage in 1970s-1980s world film culture. True, Herzog had a comic side, and in The Falls Greenaway offered whimsy, though of a relentless, almost oppressive variety. Most other directors, though, were somber as well as severe. But Ruiz enjoyed intellectual lampoon, pastiche, clever cross-references, and straight-faced absurdity; the Chris Marker of Letter from Siberia (1957) is perhaps a predecessor, though Marker himself didn’t escape Ruizian parody.

Ruses

Of Great Events and Ordinary People.

Having seen about ten percent of the Ruiz oeuvre, and a lot of it quite long ago, I can’t offer a comprehensive appraisal. (Visit the bottom of the page for some more assured threads through the maze.) For reasons that will be understandable to regular readers of this page, however, I feel obliged to write something in his memory. I merely offer some observations on aspects of his work.

Ruiz often based a film on a striking formal premise, what Henry James might call a donnée. Socialist Realism (Considered as One of the Fine Arts) (1973) began, Ruiz tells us, from the idea of

having two stories that would never meet (like in Faulkner’s Wild Palms), separated by a poem. The link would be made through this lyrical element placed at the centre – the element I eventually decided to throw out. These two stories would touch each other for a single moment, accidentally, and this moment would be secondary in relation to the totality of the film.

Imagine another sort of intersection: two films in one, not a film-within-a-film but two distinct movies, one incomplete, the other filling the gaps but revising and correcting the first (The Suspended Vocation, 1977). Or imagine making an art-history documentary that speculates on the possibility of a missing link in the output of an imaginary, mediocre artist (The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting, 1979). How about dismantling the conventions of TV election coverage, to the point where one can no longer discern what candidate won (Of Great Events and Ordinary People, 1979)? Or what if a man assigned to memorize the names of 15,000 political resisters becomes absorbed in recalling visiting a movie house as a child (Life Is a Dream, 1986)? Or perhaps a single actor could play different characters (Three Lives and Only One Death, 1996)?

In their working out, however, these givens often fret and fall away. They are overtaken, or nowadays we might say overwritten, by digressions, anecdotes, accidents, interruptions, abstruse commentary, coincidences, free associations, labyrinthine plot twists (often driven by conspiracies and secret pacts), and Surrealist juxtapositions. The movie house of Life Is a Dream has a toy train running through it. Ruiz’s affinities with Borges and Góngora and Chesterton point to an almost academic fascination with schematic systems, as well as the desire to push them toward absurdity. It’s telling that the poem that was to knot the two strands of Socialist Realism was clipped from the movie.

Narrative binds, but narrative also loosens. It can be a robust oak, but it can also be kudzu. Ruiz understood that what keeps us listening, reading, watching is the promise of a surprise that in retrospect will seem inevitable. The best tragic plot, Aristotle says, is one that makes unexpected things happen within a cogent chain of causality. Ruiz knew our inclinations, but what he gave us were plots of the sort that Aristotle calls episodic–perhaps we should say fragmentary. His plots exfoliate, in both senses of the word: they spread out from a kernel, and they peel off in flakes.

In this respect he turns out to be the realist, and Aristotle the fabulist. Ruiz understood that real-world stories breed like rabbits. Listen to yourself and a friend in conversation, and you’ll find one story calling up another, with yet a third crowding from at a tangent before the first one is finished. In plotting our fictions, we can multiply tales neatly, staking them out in parallel lines or coiling them inside Chinese boxes. But if we take the pressure off, the stories can burst out of control, intertwining or doubling back or sprawling out or just dying off. Feuillade and his contemporaries understood this: A serial could go on forever, because we could plop in a fresh character and create a further adventure. The same thing happens with news on the Internet, spreading and splintering, each version of a story torn apart but also expanded by rehash and critique.

Perhaps we can take some of Ruiz’s abrupt deep-focus shots, blowing up an action or a bit of the set that would otherwise be minor background detail, as a pictorial reminder of the centrifugal impulse of narrative. Anything looming in the foreground hints at the possibility of a new character with a new story. In Three Crowns of the Sailor, while the sailor listens to a tale told by the Blind Man, we are distracted by grotesque glimpses of what unseen others are up to in the bar.

Stories have to end, but nothing at the end can match the arousal of a beginning. Endings usually disappoint. The explanation of an puzzling situation–say, footprints on the ceiling–will inevitably be more prosaic than the premise that sets our imaginations on a wanton chase. (Hence the perfunctory, even arbitrary, resolutions of detective stories.) By contrast, openings refresh us and, as the name implies, “open” things up to crazy possibilities. So why not use the prospect of endless beginnings, perpetual change of situation, to sustain the magic?

What becomes inevitable isn’t a logical resolution, which has to be more or less imposed by tradition. What’s inevitable is a perpetual spawning of characters, plots, and situations. So an apparently stable, albeit fantastic, narrative situation posited at the start may be undermined. Again and again the film seems to start over; the rules keep changing. Ruiz made shaggy-dog stories for cinephiles. He was a formalist who liked unraveling forms.

On the whole I was more an admirer than an enthusiast. I thought Ruiz’s films were imaginative and risky in ways that opened up new horizons. I tried to do justice to his importance in the survey of film history that Kristin and I composed.

Yet here we confront the difference between critical judgment and personal taste. I tended to find each Ruiz film intriguing on an intellectual level, but dry and scattershot as well. For all the prodigious invention, and given his bias toward free-range story breeding, I sometimes thought that the données were underdeveloped. He had wondrous ideas, but I wasn’t sure that he did enough with them. And of course some stretches of his yarns were downright opaque to me.

Still, artists have a way of teaching us how to watch, and rewatch, their work. Maybe now, after having been absorbed by Mysteries of Lisbon for reasons sketched here, I’m better prepared to appreciate the legacy of a unique sensibility–one that has already given us the adjective Ruizian. It is a term of praise.

No filmmaker had more zealous proselytizers. His admirers have shown how to blend analytical precision with brio. They make you want to see the films pronto. The Ruiz initiate can start with Adrian Martin’s homage at girish’s site. You won’t read a more sensitive piece of film criticism this year. Next savor James Schamus’ memoir at Filmmaker, where he recalls working with Ruiz on his first US film. Proceed to Jonathan Rosenbaum’s posting of one of his classic studies of Ruiz, which includes links to other essays.

Now you’re ready for the heady experience of the annotated filmography (complete up to 2004) in the journal Rouge. Both Adrian and Jonathan participated. My quotation about Socialist Realism comes from there. By now you should be on to the films, and perhaps the writings collected in volumes one and two of Ruiz’s Poetics of Cinema.

By chance I commented on Ruiz just a little while ago. And thanks to B. Kite for the note about Ruiz and Harry Stephen Keeler, obviously kindred spirits. Mr. Kite sent Ruiz some Keeleriana, which may have influenced what Ruiz says here.

Apologies for my tongue-twisting title, which is offered in the spirit of Tres Tristes Tigres.

Mysteries of Lisbon.

Chinese boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies

The Locket.

DB here:

In the 1990s and 2000s, American cinema was hit by a rash of fancy storytelling. Filmmakers experimented with flashbacks, replays, shifting points of view, multiple universes, network narratives, and a host of other unusual devices. (Some prototypes: Pulp Fiction, The Usual Suspects, Memento, and Short Cuts.) These developments nudged me into analyzing the trend in The Way Hollywood Tells It, but my interest in such tricky narration goes back to my adolescent love of detective fiction and the stories of Henry James, Faulkner, and James Joyce. For me, mysteries and modernism went together.

That was especially true of 1940s movies, which I now realize loom large in my film consciousness. Many of the fractured, densely plotted movies I wrote about at length in Narration in the Fiction Film, such as Murder My Sweet, The Big Sleep, In This Our Life, and The Killers, come from the same era as Citizen Kane and How Green Was My Valley. So do subjects I wrote about later, such as Mildred Pierce and Rope and network pictures like Weekend at the Waldorf and Tales of Manhattan.

This summer I face up to my proclivities and give a batch of lectures under the rubric “Dark Passages: Storytelling Strategies in 1940s Hollywood.” The series, accompanied with ten screenings, is part of a “Film College” to be held in Antwerp under the auspices of the Flemish Service for Film Culture and the Belgian Cinematek. I first wrote about this “summer movie camp” here. I probably shouldn’t have called it that; I still get emails from services that sell canoeing gear and organize outings to the Poconos.

Starting to think about this course has given me more ideas than I can pursue in seven lectures, so in the weeks to come don’t be surprised if some chips from the workbench get swept up here. Even if you merely like the 1940s for those gleaming cigarette cases and those fashion shoulders that seem to have been designed with a carpenter’s level, we can enjoy some rather tricky pieces of movie storytelling.

The inner circle

During the early 1930s American studio filmmakers experimented considerably with flashbacks. (I write about that trend here.) Several associated conventions, such as the dissolve-plus-music, as well as the track-in to a narrating or remembering character, seem to have been installed then. But in the 1940s, the flashback became a more wondrous thing.

Relatively rare in the later 1930s, after a few years the technique seemed to be everywhere. You’d expect that Citizen Kane might have set the fashion, but at least eleven other pictures from 1941 boasted flashbacks. A year earlier, Sturges’ The Great McGinty had built its plot around the device and John Farrow’s Married and In Love crammed six flashbacks into less than sixty minutes. Soon critics, those chronic malcontents, protested. In 1944, the Los Angeles Times reviewer Philip K. Scheuer wrote of Double Indemnity, “I am sick of flash-back narration and I can’t forgive it here.” One producer claimed that “the market is glutted with flashback pictures,” and had alternative scripts of The Chase (1946) written to allow the editor to omit the original novel’s flashback. Since the late 1920s, flashbacks had been staples of courtroom dramas, but by late 1948 a reviewer expressed relief that in The Paradine Case (1948) “There are no flashback devices to clutter the trial.”

As flashbacks proliferated, they got weirder. Films gave us flashbacks retelling events from different characters’ perspectives, flashbacks that proved deceptively incomplete or downright false, even flashbacks narrated by corpses. Then there was the embedding option: setting a flashback within an already-established flashback.

Here’s an example. In Shoot to Kill (1947), Marian Dale is brought into the hospital from a car crash and is pumped by a reporter anxious to get her story. The narration flashes back to happier times, when the reporter introduced Marian to Larry, the new district attorney. When Larry takes her to dinner, Marian explains how she came to find him attractive. Now a further flashback shows her listening raptly to Larry’s aggressive prosecution of the case against mobster Dixie Logan. Coming out of this flashback, we’re back in the restaurant, and flirtation continues between Marian and Larry. At later points we’ll come out of that earlier time frame back to the present, with Marian and the reporter in the hospital.

This sort of embedding is an obvious option, but let’s go to the next level. What about a flashback within a flashback that’s already nested inside another flashback? Or even, gulp, flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks? Do the math. The result is like the famous Chinese boxes or Russian dolls, with one story held within another, which is held within another, and so on.

Many of the strangest narrative experiments of the 1940s are to be found in B films. Perhaps in that domain the demand for novelty and rapid turnover is greater and the constraints on plausibility, or even just good sense, are fewer. Shoot to Kill, an independently produced B-item, would seem to be an example, though it’s not as wild as The Sin of Nora Moran (1933), my candidate for America’s most peculiar flashback movie. Surprisingly, though, the multiply-embedded flashback is most prominent in two high-profile films of the 1940s.

How could I talk about them without spoilers?

Marseille or bust

Flashbacks are often presented as solutions to a mystery: we go back to the past to learn how or why something took place in the present.

Passage to Marseille (1944) opens with Manning, a war correspondent, visiting a camouflaged air base in the English countryside. From here Free French pilots launch bombing raids on Germany and occupied France. Struck by the intensity he sees on one gunner’s face, Manning asks his host Freycinet about the man’s past. Freycinet answers with “the story of a little group of whom Matrac was one.” That is the first layer, or the surrounding box.

Aboard the Ville de Nancy: We go back a few years to a French cargo ship carrying nickel ore to Marseille. Freycinet, traveling on orders, runs into conflict with the right-wing Major Duval and his coterie. The ship rescues five men from a drifting boat. Are they prospectors, as they claim? Soon Freycinet realizes that they are convicts, escaped from Devil’s Island. They start to explain how and why they got away.

Devil’s Island: We see the men plan to escape, but these convicts don’t simply want freedom. They are patriots who yearn to fight the Germans. But one, Matrac (Humphrey Bogart), sits apart from the others and won’t explain himself. Why? Another member of the team, Renault, explains.

France, 1938: Daladier returns from Munich with news of an accommodation with Hitler. Matrac, a crusading reporter, is disgusted and writes scathingly of this sellout to Nazidom. His newspaper office is smashed by right-wingers while police and citizens look on. Disabused of his faith in France, Matrac seizes the chance to flee with his lover Paula. But he is arrested, tried on trumped-up charges, and sent to Devil’s Island.

Devil’s Island: After Matrac has been let out of solitary confinement (where he shouted, “I hate France!”), the five men escape from the prison camp. The old man who helps them asks only that they promise to serve French freedom. But Matrac refuses to recite the pledge (above). The new mystery becomes: What has turned him into the loyalist gunner that Manning sees in the opening scene?

Aboard the Ville de Nancy: On the ship, word comes that Marshall Pétain has signed an armistice with the Germans. The captain secretly swerves the ship from Marseille, a Pétain-controlled city, and sets sights on England. But his ruse is discovered by Duval, whose men seize the ship. A fight ensues, with the crew and the Devil’s Island brigade pitted against the pro-German officers. Soon a German bomber arrives to sink the ship, but only after Matrac assures the dying cabin boy that they will drive the enemy out of France.

Back in the frame story, all mysteries from the past have been cleared up. Now Manning appreciates what the pilots have sacrificed, and he understands what has turned Matrac back into a patriot. The film could close quickly, but the plot sets up a new future-oriented suspense. Manning and Freycinet wait for the planes to return from the night’s bombing run. Renault’s plane, though, is delayed, and it brings back a fatally wounded Matrac. This time he has not been able to drop a message to Paula as his plane passes over their farm, but at Matrac’s funeral, Freycinet assures everyone “That letter will be delivered.”

In Passage to Marseille, Matrac’s 1938 adventure forms the core, wrapped in three layers. We have a flashback within a flashback within a flashback, itself surrounded by a frame story set in the present. The whole action takes place across about six years. Why tell the story in this complicated way?

Because, I think, it enhances mystery. The initially formulated mystery is vague, revolving around Manning’s inquiry about the charismatic Matrac, but other questions get more specific. What led these five men to near-death on the open sea? Are they really gold prospectors? Why does Matrac sit sullen while his comrades explain their patriotism to Freycinet? What has made him so bitter? And since we know from the start that he has become a committed patriot, what led him away from his solitude? These aren’t the sorts of questions you get in a classic detective story; they focus on personal psychology and character change. A more linear story tends to give us motives straightforwardly, and it explicitly traces the process of people changing their minds and hearts. The broken timeline creates more curiosity as we are led to ask why people do what they do. These are puzzles of personality.

The film thus gains a double propulsion. We have the usual forward movement, the rhythm of anticipation hinging on the question: What will happen next? But the mystery element adds curiosity about the past, asking: What led up to the situation of crisis that we see now? This double movement is seen in many 1940s films, which in retrospect (my own flashback here) may be one reason I turned to that era in exploring storytelling options in my narration book.

Hopelessly twisted

When we encounter embedded flashbacks, the plot often treats the core, or innermost layer, as the ultimate secret, the source of what teases us in other layers. Like Passage to Marseille, The Locket (1946) turns on a puzzle of character: Is the beautiful and charming Nancy exactly as she seems? We find out when we witness a childhood trauma located in the center of the plot’s geometry.

It’s the wedding day of John Willis. While his dazzling bride-to-be Nancy beguiles the guests, John is called away to meet Dr. Blair in his study. Dr. Blair has come to warn him: Nancy is “hopelessly twisted.” He explains….

Some years earlier: Nancy and Blair meet, fall in love, and marry. With a lovely wife and a flourishing psychiatric practice, Blair couldn’t be happier, but one day a young artist, Norman Clyde, visits his office. Norman tells him that Nancy could be charged with murder, and she must act to save the life of a man about to be executed (image above). He explains….

Earlier: Nancy is visiting Norman’s studio for an art class, and soon they’re involved in a romance. Her boss Andrew Bonner is a patron of the arts, and she calls his attention to Norman’s work. After a party celebrating Norman’s recent success, Norman finds that Nancy has stolen another guest’s expensive bracelet. He asks her why she did it, and she explains….

Childhood trauma: Nancy is ten, and her mother works as a servant for a wealthy family. The daughter of the house, Karen, is Nancy’s best friend. Karen gets a diamond locket for her birthday, but she gives it to Nancy. When her mother finds out, she takes it back and upbraids the girl. Later Karen’s locket is missing. Although it simply went astray, Karen’s mother brutally forces Nancy to confess that she stole it. Nancy and her mother are dismissed from the household.

Back in Norman’s studio, he points out that Nancy’s stealing the bracelet at the Bonners’ party was her effort to get even with Karen’s mother. Nancy swears to never steal again, and he anonymously mails the bracelet back to its owner. Later, at another art-crowd party at the Bonners, Norman is looking for Nancy when he hears a gunshot. Upstairs, he finds Nancy running down the corridor while a maid discovers Bonner’s body. Later, Nancy denies killing her boss, and Norman agrees to conceal what he saw. But he’s tormented by the fact that a manservant is now the chief suspect. Claiming that he’s too suspicious of her, Nancy breaks off their affair.

Back in Blair’s office, Norman begs Blair to induce Nancy to confess and save the servant, who’s to be executed tonight. Norman visits Blair and Nancy, who admits their old affair but denies killing Bonner. The next day, with the servant now executed, Norman flings himself through Blair’s office window and falls to his death. Shaken, Blair returns to England, where he and Nancy take up the war effort. When a bomb is dropped on their own street, Blair searches the rubble of their apartment and finds jewels that have gone missing from the collection of an acquaintance. Nancy turns up unharmed, but Blair has a breakdown and Nancy leaves England.

Back at the wedding: John remains skeptical, especially after Nancy comes in. She smilingly admits knowing Blair, but says he was only her psychoanalyst. She points out that he cracked up in London and was recently released from an asylum. Having renewed John’s trust, she goes to meet his mother, revealed as well to be the mother of Karen, her playmate of long ago.

We now understand that Nancy is marrying into the family that had cast her out as a child. Karen has died, and her mother fastens Karen’s treasured locket around Nancy’s neck. Trying to brazen through the ceremony, Nancy is assailed by memories of her childhood and her crimes. She becomes dizzy, screams, and faints. As she’s taken to a sanitarium, John decides to go with her, adhering to Blair’s last bit of advice: “Lockets are only symbols. It’s love she needed–and love she needs now.” Maybe she isn’t as hopelessly twisted as he had initially said, or as the plot itself seems to be.

Hitchcock’s films Spellbound and Marnie saved the revelation of childhood trauma for the climax, but The Locket doesn’t do that. Nor does the scene come at the exact center of the running time, as the plot geometry might suggest. The childhood scene arrives at the sacred twenty-five-minute mark, after Nancy’s confession to Norman that she stole the bracelet at the Bonners’ party. The plot thus emphasizes the aftershocks of Nancy’s childhood, creating suspense about whether she can continue to hide her trauma.

Someone versed in modern literature might ask: But can we be sure that we now know her trauma? Her confession to Norman is embedded in the tale Norman tells Dr. Blair. He is a somewhat unbalanced fellow, rude, proud, and inclined to do rash things. “Why,” he asks in his voice-over, “was I always throwing away the very things I wanted?” And of course his tale is embedded within the story Blair tells John Willis, the prospective bridegroom. By the end of his time with Nancy, Blair is a nervous wreck; he could be delusional. In literature, we might well suspect a trauma that has made its way through three filters (adult Nancy-Norman-Blair).

This possibility is accentuated by the film’s unusual adherence to each character’s range of knowledge during each flashback. We know pretty much only as much, in turn, as the child Nancy, Norman, and Blair know. Most classical flashbacks roam more freely outside the recounting or recalling character knew, or could have known. The Locket‘s restriction to each man successively optimizes the mystery of grown-up Nancy. But the strategy also offers no outside validation that what each man tells us actually happened. With no external or objective scenes of Nancy doing vicious things, the film locks us within what could be wholly hallucinatory tales.

Classical Hollywood film doesn’t try to undermine us so thoroughly, though. However modernist the multiple-narrator format of the film looks, the implications for reliability aren’t as unsettling as in literary works like The Sound and the Fury. The conventionally realistic style of most of the film makes it difficult for us to imagine layers of lying. We’re most likely to take what see and hear as veridical, unless there are explicit clues (as in, say, the landscapes and plot twists of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) to ask us to ask whether what we’re seeing is unreal in the fiction. What actually ensues is a drama of crafty concealment. As the evidence piles up against her, the question becomes: How will Nancy outwit her man this time?

This maneuver is especially significant in the film’s last third, when Blair suspects that she has stolen jewelry from Lord Windham’s collection. He tries to peek into her purse, but when she finally shakes out its contents, the missing locket isn’t there. He is relieved, though his suspicions continue to prey on his mind. We have to wait too, but when Blair finds the necklace in the apartment wreckage, we’re hardly surprised. Everything we see has been actual; we must doubt Nancy, not the narrators.

A ghastly melodrama

Even in the men’s stories, the film drops a few hints that Nancy isn’t what she seems. At one point, the camera lingers on her after Blair has left her in their London apartment. As she closes the curtains for the blackout, she crouches and looks askance in the classic posture of the guilty one. (On re-viewing, we might take this as suggesting she was looking off at the real hiding-place of Lord Windham’s locket.) Earlier, when she starts to tell Norman of Mrs. Willis’ abuse of her, she turns from him and looks at the camera, as if asking us to believe her.

Above all, there is the linkage of Nancy with Cassandra, the suffering madwoman of Greek mythology who was notoriously ignored by those she tried to warn. She had the gift of prophecy, but that quality seems denied Nancy. The prophetess we meet in the movie is a horoscope reader at the wedding, and she supplies banal and contradictory predictions. More telling, and spooky, is the fact that the Cassandra of the film is seen in Norman’s painting, and her eyes are filmed over, blank and presumably blind. This image is counterposed to the portrait Norman later paints of Bonner’s wife. She is confined to a wheelchair but on the canvas, she is presented as majestically erect and possessed of a penetrating glance.

The blind Cassandra seems scarily oblivious to her madness, while this painted mother-figure seems all-seeing. It’s no great reach to consider her a variant of Karen’s mother, who tormented the young Nancy and who comes back at the end as another, less serene incarnation of Norman’s second painting.

In sum, the prophetic quality of the heroine’s namesake is taken over by the film’s overall narration, which makes sure that everything that is planted early (the locket, the painting, a music box, the mean Mom) comes back with a relentless logic at the end.

But we shouldn’t forget that the Cassandra of legend was repeatedly raped. If she’s mad, men helped make her that way. The film is as much a study in male neurosis as in female frailties. Behind the swagger and insults, Norman is insecure, and he ends his life spectacularly. Earlier he had told Nancy: “If I had to relive these past few weeks, I’d kill myself.” As for Dr. Blair, on the strength of a single encounter, he smugly diagnoses Norman as “a paranoiac with guilt fantasies.” Yet he forgets that Norman told him about the partygoer’s missing bracelet, as if his wife’s childhood loss of the locket erased his awareness of what led her to tell it. After a few years with Nancy and the blitz, he’s the one who ends up in an asylum.

Unlike the stalwart heroes of Passage to Marseille, Nancy’s men trace no smooth character arc. The fragments given us in Passage can be swiftly reassembled. We understand that characters can change, and we expect that the film will trace out the men’s survival, especially after the opening establishes their successful bombing missions. We also note that Matrac is played by Bogart, and anyone who caught Casablanca (released fifteen months earlier) could see his change of heart coming from far off.

In The Locket, the failure of the men to understand, let alone heal, Nancy is made explicit when she tells Blair about a film she’s just seen. “I’m all goosepimples.” “A melodrama?” he asks. (We need to recall that in the 1940s that term was often applied to crime films and thrillers.)

Nancy: Yes, it was ghastly. You ought to see it, Harry. It’s about a schizophrenic who kills his wife and doesn’t know it.

Blair, laughing: I’m afraid that wouldn’t be much of a treat for me.

Nancy: That’s where you’re wrong. You’d never guess how it turns out. Now it may not be sound psychologically, but the wife’s father is the–

Blair: Darling, do you mind? You can tell me later.

Nancy’s father, she told Norman, was a painter like him, but he failed, and he is already dead when we see her as a child. In the popularized Freudianism of the 1940s, perhaps Nancy lacks the firm guidance of a strong male; certainly her kindly but ineffectual mother isn’t much help to her. But then neither are these supposedly grown-up men.

Risks and rewards

During Nancy’s hallucinatory march to the altar, music and dialogue and visual moments from earlier in the film collide and overwhelm her. But this is merely the climax of the inward bent of The Locket as a whole, which contains almost no exterior scenes. We might be tempted to attribute this interiority to the old standbys, wartime trauma and postwar malaise. The subjective sequences could be put down to the resurgence of Expressionist style, purportedly under the influence of German directors and technicians who fled to Hollywood. So far, so familiar.

I’m inclined to see a different dynamic at work. What if the stereotypes of situation and imagery sprang not from a Zeitgeist or localized influences? What if current themes and trends were exploited by filmmakers aiming for a more complicated sort of storytelling that still adhered to the models given by tradition? For reasons I hope to explore in my lectures and in some blog jottings, I think that many American filmmakers aimed more or less deliberately to revise Hollywood narrative norms in fresh, sometimes startling ways. In their urge to shake up their audiences, writers, directors, and others competed in pushing the envelope, straining the premises further as the decade went on. Why not a blind Cassandra or a mixup of mother-figures? Why not tell a story from a corpse’s point of view?

This enterprise gave us many fresh, even shocking films, but they risked incoherence. You see it in the resort to amnesiac heroes, to savage dreams, to perfunctory or downright inconsistent endings, to angels who might rescue us, to moments that repeat or condense or contort other images scattered across the movie, like the queenly mothers and blind prophetess of The Locket. When a producer is ready to leave decisions about flashbacks to the editing stage, you shouldn’t be surprised by gaps and disparities.

Still, even if a movie gets hopelessly twisted, it can provide a creative play with storytelling options. Or so I’ll try to show from time to time in the next few months.

An earlier entry discusses the cycle of early-1930s flashback films. The quote from Philip Scheuer comes from James Naremore’s subtle and informative More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts, 2d ed., 2008, 17. The quotation from Seymour Nebenzal, producer of The Chase, appears in “Hollywood Inside,” Variety (16 September 1946), 2. The finished film did drop the novel’s flashback, but something more peculiar was put in its place. (That’s a whole other blog.) The Paradine Case review is quoted in an advertisement for the film in Variety (15 January 1948), 3.

My outline of Passage to Marseille simplifies the plot architecture just a little. The first Devil’s Island block is actually two chunks, a brief one introducing a few of the team, followed by a return to the narrating situation on the ship, and then followed by much lengthier set of scenes on Devil’s Island. The logic of the “sandwich-structure” flashbacks remains intact, though.

Barbara Deming’sRunning Away from Myself: A Dream Portrait of America Drawn from the Films of the 40’s, pp. 23-25, fits the iconography and narrative reversals of Passage to Marseille into a wider trend of wartime patriots who, apparently having cast off their cynicism, make commitment to the cause seem a new form of their earlier despair.

The embedded-story strategy is a recursive one. How many levels can a viewer handle before confusion sets in? I raise the problem in discussing Inception here, and I mention Robin Dunbar’s suggestion that five layers is the limit most people can follow. The 1940s films I discuss in this entry have four, counting the framing situations, but Inception pushes the limit with its five.

An informative history of nested boxes, dolls, and the like across cultures can be found here, the source of my array of caskets in the illustration above.

The Locket.

P.S. 8 June: William Benzon, of the vivacious site The Valve and the blogsite New Savanna, has written to point out that what I’ve characterized as boxes-within-boxes belongs to a broader tradition known as ring composition. It is an ancient literary technique that can operate at many levels, from that of plot down to a passage of a few lines. The essential feature is that the components are arranged in that ABCDCBA pattern. Ring composition has been analyzed by Mary Douglas in Thinking in Circles, and Bill has written about it here. Thanks to Bill for reminding me!

Forking tracks: SOURCE CODE

Source Code.

DB here:

Who cares if the Source Code software is junk science? The muzzy premise forms the basis of an agreeable little thriller from the tail end of this year’s Dead Zone. Even if you don’t share my admiration for this movie, maybe I can persuade you that it points up an intriguing wrinkle in the recent history of American studio storytelling.

I surveyed this history in some books, but Source Code provides a nice occasion to update my argument. My main point remains: More than we often admit, today’s trends rely on yesterday’s traditions. Quite stable strategies of plotting, visual narration, and the like are still in play in our movies. When a movie does innovate in its storytelling, it needs to do so craftily. The more daring your narrative strategies, the more carefully, even redundantly, you need to map them out. The game demands clarity through varied repetition.

More generally, there’s a value in thinking of movies as combinations and transformations of inherited conventions. We’re used to considering conventions as matters of theme and genre, but I’m equally interested in conventions of technique and of narrative form. These are areas we’re still only starting to understand, although many entries on our site try to make progress in understanding changing norms of style and storytelling. (Check our Narrative Strategies category for further leads.)

If you haven’t seen Source Code, you shouldn’t read on. I reveal damn near everything.

He couldn’t come home

Colter Stevens awakes on a Chicago commuter train in the body of another man, Sean Ventress, who’s accompanying the attractive Christina Warren. Very soon the train explodes, and Colter reawakens in a pod in a military facility. He learns that after being shot down in Afghanistan he has been at the Nellis facility for two months, awaiting an experiment in “time realignment.”

Because a person’s brain activity does not cease immediately at death, memory modules can be accessed across an eight-minute period before full shutdown. Colter’s brain anatomy happens to be attuned to that of Ventress, so the experimenters can in effect insert his mind into Ventress’s body in the few minutes before the train explosion. The investigators know that the bomber is planning to set off a much bigger explosion in downtown Chicago, and Colter-as-Ventress could gather enough information to prevent it.

Under the tutelage of officer Goodwin and her superior, chief researcher Rutledge, Colter will be sent back in to the train, neurally speaking, to try to identify the bomber for them. He cannot prevent the train blowup, Rutledge insists. He can only hope to identify the bomber before the dirty bomb goes off downtown. But Colter can, in the shrinking time remaining, be sent back again and again, though it’s physically and emotionally punishing for him.

As a result, the film alternates between two zones of action. At the Nellis facility, time moves forward as Colter gradually comes to understand his circumstances and his mission. This action is under the pressure of a deadline: find the culprit before the dirty bomb is triggered. The other zone of action is the train, where the deadline is tighter (eight minutes before Ventress’s death) and the action is replayed as Colter tries different tactics to fulfill his charge.

Many incidents fill out this dynamic. In the pod, the early scenes are dominated by Colter’s efforts to understand the experiment he’s involved in and to grasp what has happened to him since his chopper crash. He is being kept alive artificially so that his brain activity can sync with Ventress’s. Eventually he breaks through Goodwin’s façade of coldness, converting her to sympathy for his plight. When she finally stares compassionately down at his broken body in its glowing casket, she resembles a mother or nurse looking down at a baby. On the train, the early scenes throw up some decoy suspects, most prominently an agitated man of vaguely Middle Eastern appearance. He is proven not to be the bomber, who’s eventually revealed as a dough-faced nerd. (Between the stereotyped Islamic terrorist and the stereotype domestic one, the plot opts for the latter.)

Colter not only blocks the Chicago bombing; with Goodwin’s help he is sent back one last time to stop the train bombing as well. In the course of that effort, he manages to reset the past, creating a parallel world in which the briefcase bomb never ignited and the bomber was captured before he left the train. Colter, dead at the Nellis facility, becomes Ventress wholly, able to spend a day with Christina and to send a text message to Goodwin promising that the Source Code has even bigger possibilities than Rutledge imagines. It can change the course of events. And she can reassure Colter’s original self, when he finally is sent on a mission: “Everything’s gonna be okay.”

It’s the new me

This plot is articulated in quite traditional ways. At less than 90 minutes, the film yields three large-scale parts or “acts.” The Setup introduces us to the premises, establishing the train bombing and the Nellis facility supervision; I’d argue that this ends at about 28 minutes. At this point Colter, has to rule out his chief suspect, the commuting businessman with motion sickness, when the train explosion takes place. The second stretch of the plot consists of more failed efforts, but culminates at about 56 minutes, when Colter correctly identifies the bomber, Derek Frost. Again, he can’t forestall the train bombing, but returning to his capsule he passes the key information to his masters, and they can arrest Derek before the dirty bomb hits Chicago. At this point his official mission is over. But the movie isn’t. Colter persuades Goodwin to let him go back one more time to stop the train bomb and save the passengers—effectively countermanding Rutledge’s injunction that the past can’t be altered. A three-minute epilogue starting around 82:00 wraps things up.

Filling out this structure is the characteristic double plot of classical Hollywood: heterosexual romance plus another, usually connected, line of action. The suspense plotline is organized as a series of goals, initially articulated by Goodwin. She tells Colter to find the bomb, which he does in the first replay. But as he can’t prevent the explosion, he needs to know more about who’s behind it. His next passes proceed in steps. He has to identify the guilty passenger; then he must try to steal the conductor’s pistol; then he searches for bomb-related paraphernalia.

About halfway through the film, however, Colter conceives purposes of his own. Inside the capsule, he probes Goodwin about what has happened to him. On the train, he starts to investigate the insignia of the agency controlling him, to trace his own fate in Afghanistan, to try to contact his father, and to phone the Nellis facility. He’ll eventually succeed in all these attempts, balancing the failures of the first chunk of the plot. Ultimately he’ll decide to try to save the train. Crucially, this last goal is formulated after he believes that having been more or less killed in Afghanistan, he is about to be terminated by the Source Code project. So he can now operate in a mode of pure self-sacrifice. As often happens in a classical film, a character finds the resources to throw off others’ demands and make decisions on his own.

In the romance plotline, by assuming the identity of Sean Fentress, Colter becomes attached to Christina. Now saving the train takes on a more personal weight; he will be saving her. The emotional dimension here is deepened by Colter’s backstory, his unresolved relation to his father. Eventually he is able to get closure by posing as Fentress and phoning tell the grieving old man that Colter indeed loved him. In screenwriters’ parlance, Colter is “exorcising his demons.”

Colter’s growing confidence in dealing with his past and the bomb threat changes his behavior toward Christina. No longer the skittish neurotic of his early incarnations, he becomes brisk and confident. Eventually he can relax, paying the standup comic across the aisle to entertain the other passengers. As often happens, character change is measured by a repetition. The first time Colter says, “It’s the new me,” he refers ironically to his discovery that he’s in another man’s body. But now, as the comic launches into his shtick, Christina points out that her companion has changed. He answers by saying, “It’s the new me,” which signals a deeper acceptance of his sacrificial role. He doesn’t expect to survive after he returns to the capsule, but he has saved the people on the train and he can for a moment celebrate a final moment of vitality.

This is not a simulation

These cascading goals and character arcs emerge gradually, thanks to cunning narration. At first we’re restricted largely to what Colter knows, but gradually our awareness widens. We come to learn about Goodwin’s role in the Source Code project and about Rutledge’s ruthless efforts to use Colter as a test case. By the climax, the film cuts freely between the two arenas, the train and the Nellis compound, creating classical suspense as Goodwin postpones erasing Colter’s memory while he races to prevent the train blowup. This is the Griffith heritage of the last-minute rescue.

For the viewer, the film starts with mystery—Colter is on the train and he doesn’t know who he is—and moves toward a mixture of curiosity about his past and suspense about how he will solve his problem. By the start of the climax, we have understood all the forces converging on Colter’s last mission, and sheer suspense takes over. There is, though, one final surprise, which seems to have worried other critics more than it does me. More on this shortly.

Even before the explicit widening of narrational knowledge, we’ve been given a dose of something enigmatic. The shifts from the train explosion to the Nellis pod are provided with whooshing transitions of blurred and fragmentary imagery that, as the film goes on, clarify a bit. At the film’s center, these images will be replaced by distorted flashbacks to his helicopter crash in Afghanistan, a passage that leads him to ask Goodwin: “Am I dead?”

One of the images glimpsed in the vortex montages is that of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate sculpture, which Christina and Colter-as-Sean will visit in the epilogue.

Thematically, the image can be taken as an emblem of the lives Colter has saved, with a hazy overlay that reminds us of his floating consciousness for most of the movie. But the more basic question is about the status of these blurry visions. Are they Colter’s premonitions of a future to come? That assumption seems confirmed at the end when Colter, staring at the sculpture, asks Christina if she believes in Fate. At the same time, the images can be treated as coming from outside his ken, as if the film were providing teasing hints about how the action will resolve.

In these montages we see an interplay between destiny and chance common in Hollywood storytelling. (Christina answers Colter’s question by saying she’s “more of a dumb luck kind of girl.”) Very often, even if chance seems to govern the plot, a film’s overarching narration seems to “know” how things will turn out. Thus the film can have it both ways, acknowledging that life sometimes depends on chance but also recognizing that satisfying stories feel inevitable.

As usual, you will have eight minutes

Since the early 1990s, many films have resorted to what we might call“multiple-draft” plotting, the replaying of key scenes with important variations. Groundhog Day (1993) is our prototype, and it influenced Source Code screenwriter Ben Ripley. An earlier instance is the alternative futures revisited by Marty McFly in Back to the Future II (1989). Yet these films revived an older, although minor, trend going back quite far in Hollywood. The device was sometimes used to present alternative futures, as in The Love of Sunya (1927), but more commonly it presented different characters’ versions of what happened in the past. We find it in the courtroom drama Thru Different Eyes (1929), which dramatizes conflicting trial testimony, and in Crossfire (1947), which somewhat anticipates Rashomon‘s use of the strategy. Contradictory replays are used for more comic effect in The I Don’t Care Girl (1953) and Les Girls (1955).

What led to the resurgence of multiple-draft storytelling in our day? Partly, I think, the changing genre ecology of Hollywood. During the 1970s and 1980s, certain genres like the musical and the Western faded out, and horror and science-fiction/ technofantasy became more important. These genres, still going strong today, encourage playing around with subjective states (dreams, hallucinations), devising misleading narration, and creating branching and looping timelines (through time-travel, telepathy, multiverses, and the like). The filmic experiments probably owe something as well to the rise of popular writers in the vein of Stephen King and Michael Crichton, along with the revival of the work of Philip K. Dick.

Pop science also furnished new narrative possibilities. Researchers discovered the Butterfly Effect: change one little condition at the start of a process, and you get a different result. There was the Forking-Path, or Choose Your Own Adventure, option, whereby you can imagine taking a different path in your life. And there was the Multiple-Universe Hypothesis, whereby we can hop from one parallel world to another.

Even without the pseudoscientific justification, the reset-replay option showed up in films that were influenced by earlier storytelling. Film noir sometimes resorted to replaying scenes in ways that filled in information missing on the first pass (e.g., Mildred Pierce, 1945). Tarantino made no bones about being influenced by the overlapping flashbacks in The Killing (1955), themselves derived from Lionel White’s original novel Clean Break. So in the wake of Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Jackie Brown (1997), we got many thrillers and crime films that retold the same events from different characters’ viewpoints (Out of Sight, 1998), right up to an almost endless series of replays (Vantage Point, 2008).

All of these multiple-draft tactics made their way into global cinema too; Run Lola Run (1998) is a prominent example, but so too is the dazzling anime The Girl Who Leaped through Time (2006). In America, the market’s constant demand for something novel (but not too novel) pushed filmmakers toward all the variants we see in films as different as Thirteen Conversations about One Thing (2001) and Confidence (2003).

For mainstream filmmakers the key is redundancy. The reset-replay device has to be explained through dialogue, diagrams, intertitles, and sheer repetition so that we understand it going forward. (Contrast, say, Primer, which left most viewers behind.) Once we’ve grasped the similarities in the core situation, we can measure the differences in each iteration.

Source Code director Duncan Jones had already shown an interest in replays in Moon (2009), with its Möbius-band treatment of the crashed lunar vehicle, followed by Sam’s awakening in the infirmary. The mystery of the first encounter, in which Sam seems to find another version of himself in the vehicle, gets slowly cleared up through dialogue, the discovery of a secret repository, and not least important, a bandaged hand wound that allows us to keep the two Sams more or less distinct. Similarly, in Source Code, the returns to the train can be more elliptical as we master the situation: the introductory shots (duck pond, Colter waking up) can be skipped or compressed. Our training is guided by Colter’s, as he starts to predict the trivial incidents (coffee spill, cellphone call from Christina’s ex) and handle them matter-of-factly. These repetitions anchor us and allow us to register the different actions he undertakes in each module.

Those modules are ruled by another convention, what screenwriting manuals call the ticking clock. Usually reserved for the climax of films in all genres, even romantic comedies, the ticking clock plays a bigger role in Source Code. It governs both the macro-level (the deadline to stop the dirty bomb) and every return to the train. Strikingly, those replays are very strictly contained. Colter is assigned eight minutes for each mission, and by my count each of the developed train episodes before the climax consumes anywhere between four and eight minutes of screen duration, never more. His recurring deadline becomes a structural cell of the movie.

We have a chance to start over in the rubble

Déjà vu.

Multiple-draft storytelling promises to abandon the classic “linearity” of Hollywood storytelling, but the promise is largely a tease. The convention gestures toward unruly complication, but it tends to reinstall linearity, sorting everything out and making the final stretch of the film seem a logical consequence of what went before. Despite all the cycles and skip-backs of Groundhog Day, Phil changes incrementally into a kinder person and gets the woman he has come to deserve. In the money-drop sequence of Jackie Brown, the minute variations of point-of-view mesh into a single comprehensive account of how the scam went down. Part of the fascination of the technique for us may be similar to what a child feels after spinning around and stopping: the dizziness is fun, but so too is the bumpy readjustment to a stable world.

Source Code wants a happy ending. Does it prepare us sufficiently? We have the vortex transitions that look forward to the Cloud Gate epilogue, but are these enough? Don’t we need something at the level of plot action?

In his last visit to the train, Colter manages to disarm the briefcase bomb and capture Derek Frost. So now the train didn’t explode; the Nellis facility was never put on alert to forestall the dirty bomb; Rutledge and Goodwin never tried using Colter as their Source Code guinea pig. Rutledge earlier denied that this revision of the past would be possible, but the plot nonetheless moves us into a parallel world characteristic of forking-path plots like Run Lola Run and The Butterfly Effect (2004). And this reality has become sovereign, since Colter can now successfully send Goodwin a text message advising her about the unexpected success of the Source Code stratagem. This also means that as more or less a brain in a vat, the wounded Colter survives to serve in other missions.

Given the right sort of motivation, then, the forking-path option can be activated as a resolution device for multiple-draft plots. The film’s makers invoke a multiverse explanation explicitly in one piece of publicity for the film (trailer 2 here). More important, we’re prepared to accept such a switch on pretty slender evidence. Counterfactual thinking in terms of forking paths is a part of our folk psychology. If only we’d left the parking lot ten minutes earlier, we wouldn’t have hit this traffic. If I hadn’t taken this job, I wouldn’t have met my husband….and so on. Despite what experts like Rutledge say, when we see Colter disarm the lethal briefcase, we’re prepared to buy the possibility that everything afterward has changed.

Still, we need some elements in the movie itself to justify the jump. During his final questioning of Goodwin, Colter asks if she could imagine a world in which she didn’t get divorced, being “a woman who took a different fork in the road.” Colter insists that the course of events is changeable: Christina “doesn’t have to be dead.” At various points he says he thinks he can save the train, but like Rutledge, Goodwin reasserts that there’s only one reality, and its events have already happened.

Interestingly, the debate itself might be a minor convention of the multiple-draft plot. In Tony Scott’s Déjà vu, (2006) a close analogue to Source Code, two scientists disagree about whether the past is malleable. Professor Denny says that you cannot change what’s already happened. “God’s mind is made up about this.” But his colleague Shanti adheres to the “branching universe theory,” which she helpfully draws on paper for our benefit (echoing Doc’s famous diagram in Back to the Future II). A significant event, Shanti maintains, can shift the course of events and create a new path. It can even, she claims, wipe out the branch that was initially taken as baseline reality.

Images of linearity deflected, of hiccups and branches off a main line, show up in Source Code too. The train bomb is fired off just as another train passes on a parallel track. But in the final replay, after Colter has set things right and paid the comedian to do his turn, we see “all this life”—the passengers frozen in amusement. The shot is a kind of marker that, as Shanti puts it, something big has changed. Abruptly we get a shot we haven’t seen before: a high angle of our train switching to another track. Then we cut back to Colter and Christina about to kiss, as the rival train passes safely. Our train’s new trajectory confirms that an alternate reality has been put in place. It also echoes an earlier line, when Christina, talking about her plans for the future, asks Colter: “Am I on the right track?”

This will end

Source Code appropriates the forking-path option in order to arrive at a final draft of Colter’s fate. This stratagem reflects a common tendency in the history of narrative forms. Over the years, as readers become more skilled in picking up conventions, authors can be more elliptical and oblique. Descriptions can be more bare-bones, and authorial commentary can be given in a phrase rather than a paragraph. (Elmore Leonard: “I leave out the parts that readers skip.”) Films that once needed to motivate alternative futures through dreams or fortune-telling now do so through scientific gadgetry, or just by referencing similar movies.

We surely lose something in a trend toward such laconic storytelling, but there are gains in speed and impact. What Déjà vu debates for minutes can be abbreviated in Source Code because audiences have caught on: a few cues suffice to let us figure out how this sort of story goes. For me, the very premise of the replay device, plus Colter’s raising the issue of forking paths with Goodwin, plus our commonsense psychology, plus the swooshes, plus the convention of the happy wrapup, not to mention the overall urge to reward our our hero for all his sacrifice—all this is enough to push the ending over the finish line.

More generally, you can invoke Steven Johnson’s argument that we’re getting smarter about picking up quickly-emerging conventions. Popular culture, he claims, is more intellectually demanding than it used to be; examples would be The Wire and Lost. I’m not wholly convinced, since Our Mutual Friend and other items consumed by generations past can be pretty complex, and twentieth-century middlebrow artists like Thornton Wilder, J. B. Priestley, and Alan Ayckbourn have flirted with formal experiment. I’d relate the intricacy of some popular narratives partly to the proliferation of more niche genres and specialized publics, along with the growth of pop connoisseurship. Aging hipsters and cool college-educated youngsters, fortified with high disposable incomes, now flaunt a nerdy side and enjoy avant-gardish innovations.

For whatever reasons, in a lot of mass storytelling, form is the new content. But that newness depends considerably on recasting long-standing traditions. Nothing comes from nothing. And it can be fun to trace the fluctuating dynamic of novelty and familiarity as it emerges in the movies that we see right now.

At Electric Sheep Duncan Jones elaborates on the forking-path dimension of his film.

This entry builds on work I’ve done elsewhere. For more on classical conventions of plotting and narration, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, part one, and Narration in the Fiction Film, Chapter 9. On recent narrative innovations and their relation to classical premises, see The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies, 51-103. On forking-path plots and their relation to folk psychology, see the essay “Film Futures” in Poetics of Cinema. One essay in that volume discusses Mildred Pierce‘s tricky replay of the opening murder, while another surveys another contemporary trend, the network narrative.

On dividing a film’s plot into parts, see Kristin’s earlier entry and my essay on Mission: Impossible III. Go here to see what happens when Archie Andrews takes a forking path.