Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Rebooked

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, CinemaScope).

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers? I asked once before, but in a different tone of voice. Books are still being published, thick and fast, and everybody who cares about cinema should take a look at these.

In the frame

Ballet mécanique.

When the talk turns to the great film theorists of the heroic era, you hear a lot about Bazin and Eisenstein, less about Rudolf Arnheim. But the prodigiously learned Arnheim pioneered the study of art from the perspective of Gestalt psychology. Although he’s probably best known for his studies of painting in Art and Visual Perception, as a young man he was a film critic and in 1930 published a major theoretical book on cinema. First known in English as Film, then in its 1957 revision as Film as Art, this has long been considered a milestone. But Arnheim was famously skeptical of color and sound movies, and he had comparatively little to say about the many cinematic trends after 1930. (He died in 2007, aged 102.) While psychologists grew wary of Gestalt ideas, cinephiles embraced Bazin and academics moved toward semiotics and other large-scale theories. For some time Arnheim has seemed a graceful, erudite relic.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

This is no esoteric exercise. The essays present probing arguments with patient lucidity. Encouragingly, most of the contributors are early in their careers. (I have a piece in the collection as well, an expanded version of a blog entry.) The anthology proves that a seminal thinker can always be reappraised. There’s always more to be understood.

In the Higgins collection Malcolm Turvey furnishes an essay on Arnheim’s relation to various strands of modernism. That vast movement is treated at greater length in Turvey’s new book, The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s. At the book’s core are close analyses of five exemplary films encapsulating various trends. Turvey studies Richter’s Rhythm 21 and abstract film, Léger and Murphy’s Ballet mécanique and cinéma pur, Clair’s Paris Qui Dort and Dada, Dalí and Buñuel’s Chien Andalou and Surrealism, and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and the “city symphony” format. For each film Turvey provides informative historical background and, often, some controversial arguments. For example, he finds Léger to be surprisingly concerned with preserving classical standards of beauty. Indeed, one overall thrust of the book is to suggest that modernism was less a rejection of all that went before than a selective assimilation of valuable bits of tradition. (This applies as well to Eisenstein, I think, as I try to show in my book on his work.)

No less controversial is Turvey’s careful dissection of what has come to be known as “the modernity thesis.” This is the idea that urbanization, technological change, and other forces have fundamentally changed the way we perceive the world, perhaps even altered our basic sensory processes. Specifically, some argue, because the modern environment triggers a fragmentary, distracted experience, that experience is mimicked by certain types of film, or indeed by all films. Step by step Turvey argues that this is an implausible conclusion. This last chapter is sure to stir debate among the many scholars who argue for film’s essential tie to a modern mode of perception.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Cossar advances to more familiar ground, studying early widescreen practice in The Big Trail and moving to analyses of films by masters like Preminger, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin. Although most chroniclers of the tradition stop in the early 1960s, Cossar presses on to consider the changes wrought by split-screen films like The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair. The survey concludes with discussions of cropping techniques in digital animation (e.g., Pixar) and web videos, which often employ letterboxing as a compositional device. In all, Letterbox traces recurring technological problems and aesthetic solutions across a wide swath of film history.

Critics’ corner

Two of America’s senior film writers have revisited their earlier writings, with lively results. Dave Kehr’s collection When Movies Mattered samples his Chicago Reader period, from 1974 to 1986. Disguised as weekly reviews, Kehr’s pieces were nuanced essays on films both contemporary and classic.

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

It resurrects the flashback structure of his 1950 Sunset Boulevard, but it goes further, placing flashbacks with flashbacks and complicating the time scheme in a manner reminiscent of such demented 40s films noirs as Michael Curtiz’s Passage to Marseille and John Brahm’s The Locket. . . But the jumble of tenses also clarifies the film’s design as a subjective stream of consciousness. The images come floating up, appearing in the order of memory.

How many of those reviewers whose flash-fried opinions count for so much on Rotten Tomatoes can summon up information about the construction of Passage to Marseille or The Locket? And how many could make the case that Wilder, in returning to the forms fashionable in his early career, would repurpose them for the sake of a reflection on death, resulting in “a film as deeply flawed as it is deeply felt”? Kehr’s work from this period is appreciative criticism at its best, and he never lets his knowledge block his immediate response. “I admire Fedora, but it also frightens me.” It’s time we admitted that Dave Kehr, working far from both LA and Manhattan, was writing some of the most intellectually substantial film criticism we have ever had.

Also hailing from the Midwest is Joseph McBride, a professor, critic, and biographer. Apart from his rumination on Welles, his books have focused on popular, even populist, directors like Capra (The Catastrophe of Success), Ford (Searching for John Ford), and Spielberg (Steven Spielberg: A Biography). The University Press of Mississippi and bringing first two volumes of this trilogy back into print, and it has just reissued the third in an updated edition.

Here Spielberg emerges as far more than a purveyor of popcorn movies. McBride sees him as a restless, wide-ranging artist, and the additions to the original book have enhanced his case. McBride offers persuasive accounts of Amistad and A.I., which he regards as major achievements. He goes on to argue that Spielberg’s unique power in the industry allowed him to face up to central political issues of the 2000s.

He made a series of films in various genres reflecting and examining the traumatic effects of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the repression of civil liberties in the United States during the George W. Bush/ Dick Cheney regime. . . . No other major American artist confronted the key events of the first decade of the century with such sustained and ambitious treatment (450).

McBride is no cheerleader. He can be as severe on Spielberg’s conduct as on his films, criticizing much of the DreamWorks product as dross and suggesting that Spielberg sometimes trims his sails in interviews. I’d contend that McBride underrates some of Spielberg’s work, notably Catch Me If You Can and The War of the Worlds. But McBride has perfected his own brand of critical biography, blending personal information (he reads the films as autobiographical), tendencies within the film industry and the broader culture, and critical assessment. All studies of Spielberg’s work must start with McBride’s monumental book. Ten years from now we can look forward to another update; surely his subject will have made a few more movies by then.

Foreign accents

8 1/2.

Today we regard Citizen Kane as a classic, if not the classic. But for several years after its 1941 release it wasn’t considered that great. It missed a place on the Sight and Sound ten-best critics’ polls for 1952; not until 1962 did it earn a spot (though at the top). Its rise in esteem was due to changes in film culture and, some have speculated, the fact that Kane was a regular on TV during the 1960s. Something similar happened with His Girl Friday, another stealth classic. I’ve traced what I know about its entry into the canon in an earlier blog entry.

What about the postwar classics like Open City and Bicycle Thieves and the works of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni and Kurosawa and the New Wave? Surely some of the films’ fame comes from their intrinsic quality—many are remarkable movies—but would we regard them the same way if their reputation hadn’t spread so widely abroad, especially in America? Questions like this lead us to what film scholars have come to call canon formation: the ways artworks come to wide notice, receive critical acclaim, and eventually become taken for granted as classics.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

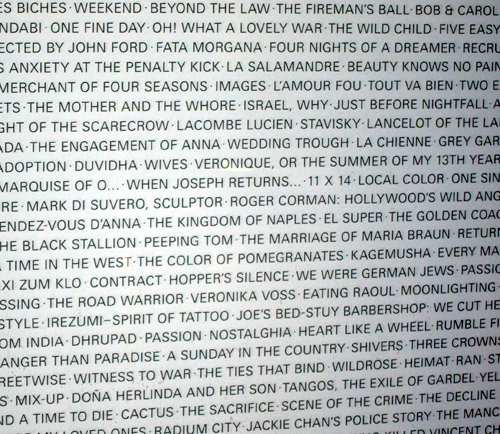

Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 reveals a side of canon formation that’s too often overlooked. Balio is less concerned with analyzing films than Turvey, Cossar, Kehr, and McBride are. He is asking a business question: What led the U. S. film industry to accept and eventually embrace films so fundamentally different from the Hollywood product?

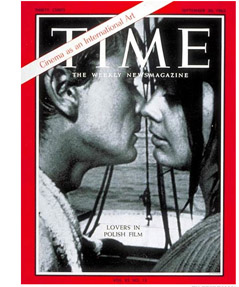

Several researchers have pointed to the roles played by influential critics, film festivals, and new periodicals like Film Comment and Film Culture. Intellectual and middlebrow magazines promoted the cosmopolitan appeal of the foreign imports. By 1963 Time could run a feverish cover story on “The Religion of Film” to coincide with the first New York Film Festival.

Balio duly notes the importance of such gatekeepers and agenda setters. But he goes back to the beginnings, with the small import market of the 1930s. Turning to the prime postwar phase, he broadens the cast of players to include the business people who risked buying, distributing, and publicizing movies that might seem hopelessly out of step with US audiences. He shows how small importers brought in Italian films at the end of the 1940s, and these attracted New York tastemakers, notably Times critic Bosley Crowther, who were keen on social realism. Within a few years ambitious entrepreneurs were marketing British comedies, Swedish psychodramas, Brigitte Bardot vehicles, and eventually the New Waves and Young Cinemas of the 1960s. As distributors fought censors and slipped films into East Side Manhattan venues, an audience came forward. The “foreign films”—often recut, sometimes dubbed, usually promoted for shock, sentiment, and sex—were positioned for the emerging tastes of young people in cities and college towns.

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Bryant Haliday and Cy Harvey of Janus Films. . . devised a successful campaign to craft an image of Bergman as auteur and to carefully control the timing of each release. . . . Janus released the films in an orderly fashion to prevent a glut on the market and to milk every last dollar out of the box office. No other auteur received such treatment.

The work paid off: Bergman made the cover of Time in 1960, and soon The Virgin Spring and Through a Glass Darkly won back-to-back Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. Eventually, Bergman and other foreign auteurs attracted the big studios. Now that small distributors had shown that there was money in coterie movies, the major companies (having problems of their own) embraced imported cinema—first through distribution and eventually through financing. If you admire Godard’s The Married Woman, Band of Outsiders, and Masculine Feminine you owe a debt to Columbia Pictures, which underwrote them.

Work like Balio’s does more than bring the name Cy Harvey into film history. It reminds us to follow the money. If we do, we’ll see that not every “foreign film” stands radically apart from big bad Hollywood. More generally, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens reminds us that even high-art cinema is produced, packaged, and circulated in an economic system. The distinction between commercial films and personal films, business versus art, is a wobbly one. Rembrandt painted on commission and Mozart was hired to write The Magic Flute. Sometimes good art is good business.

I couldn’t work this in anywhere else: The bulk of the essays in Arnheim for Film and Media Studies are by people associated with our department at Wisconsin. They do us proud, naturally. Incidentally, Joe McBride went to school at UW too, and Tino and I taught together here for over thirty years.

Dave Kehr maintains a blog and teeming forum here.

Hart Perez has made a documentary, Behind the Curtain: Joseph McBride on Writing Film History. An excerpt is here. McBride’s website has information about his many projects.

James E. Cutting provides an unusually precise account of canon creation in his 2006 book Impressionism and Its Canon, available for free download here. I’ve written an earlier blog entry discussing Jim’s research into film.

My mention of American generations is based on Elwood Carlson’s study The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Carlson examines the varying experiences and life chances of people who fought in World War II; people who came of age during the 1960s; and the less populated cohort that fell in between. Doing some pop sociology, I’d hypothesize that the art-film market’s growth relied on a convergence of all three, which were more disposed to art film than cohorts in earlier periods. For example, veterans who had served overseas and gone to college on the GI Bill were more familiar with non-US cultures than their parents and, I surmise, weren’t entirely put off by foreign films. When I first met Kristin’s mother, Jean Thompson, she already knew the work of Carl Dreyer, having seen Day of Wrath at an art cinema in Iowa City. She was in graduate school after World War II, on the G.I. Bill, as was her new husband, Roger, also in school on the G.I. Bill and managing that art cinema. They saw Children of Paradise and other wartime foreign films just getting their releases in the U.S., as well as post-war films like Bicycle Thieves.

The Lucky Few, also known as the Good Times generation, were born between the late twenties and the early 1940s. They were well placed to enjoy postwar prosperity and the period’s explosion of artistic expression. The Lucky Few cohort includes powerful film critics like John Simon (born 1925), Andrew Sarris (1928), Richard Roud (1929), Eugene Archer (1931), Susan Sontag and Richard Schickel (1933), and Molly Haskell (1939). Aged between twenty and thirty when the foreign-film wave struck, they were mighty susceptible to it. (Pauline Kael, though born in 1919, had a delayed career start, entering film journalism in the 1950s along with Sarris et al.) You might slip in David Thomson (born 1941), Jonathan Rosenbaum (1943), and Richard Corliss (1944).

The Baby Boomers jumped on the carousel in the 1960s, with results that are all too apparent. Dave Kehr and Joe McBride are Boomers, as are Kristin and I. Tino, for the record, is ageless.

Minority Report.

Venues and visions

Vitrine outside future quarters of the Film Society of Lincoln Center (detail).

DB here:

During our month in NYC, we didn’t visit only art museums (although KT was at the Met a great deal). We also, no surprise, hit some of the city’s premiere movie spots. The places were often as impressive as the films, and all deserve the support of cinephiles both local and visiting. Herewith, a recap of our visits.

Fun things happen on your way through the Forum

Mike Maggiore, in the lobby of Film Forum.

Film Forum, running since 1970, has established itself as an outstanding venue for new releases and classics. It has done heroic work over the years. I stopped by to see my old Wisconsin friend Mike Maggiore, one of FF’s programmers, and met his colleagues, including Karen Cooper, a legend in US film culture. They had just recently had a remarkable triple-night string of visitors: Scorsese introducing his new documentary Public Speaking, Jerry Schatzberg with Scarecrow, and Paul Schrader with a fresh print of Diary of a Country Priest. The current FF program, running on three screens, is here and it’s very rich.

Uncle Boonmee will have hit FF by the time you read this. Chris Ware’s gorgeous poster decorates the Forum lobby.

The gem of Astoria

Under MoMI projection, Rachael Rakes (Assistant Film Curator), David Schwartz (Chief Curator), KT, Ethan de Seife (Professor, Hofstra).

The refurbished Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria is a thing of great beauty. Family-friendly, with lots of hands-on kid activities, it also offers a bounty to the cinephile.

For one thing, it has a superb screening theatre. We sampled it when MoMI screened a pretty print of King Hu’s The Valiant Ones (1975). Kristin and I were happy to see our old favorite again.

The same hall gave us a restoration of Manoel de Oliveira’s Doomed Love (1978). The movie, 4 ½ hours long, was shot in 16mm for television. It frankly acknowledges its novelistic source by including stretches of letters and florid declamation (“I will be dead to all men, except you, Father!”), as well as a plot turning on forbidden love and oppressive social relations. This is a world of parlors, convents, trusty servants, candlelit rooms, barred windows, and lovers who actually waste away. The title could apply to virtually every character, down to the maidservant who adores our protagonist and vows, “When I see I am not needed, I will end my life.” The affair draws others into its downward spiral, leaving the hero plenty of time to reflect on his misery and the pain he has inflicted on others.

The plot is quite engrossing in the manner of a triple-decker novel. That makes it all the more surprising that we get no Viscontian spectacle or even the plush upholstery of a Masterpiece Theatre episode. The presentation is rather dry and detached. I wondered if Ruiz’s recent Mysteries of Lisbon, drawn from another novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, was in effect a reply to Oliveira’s film. By comparison with Ruiz’s sparkling compositions and glissando flashbacks, Doomed Love looks reticent and austere.

The austerity is heightened by a self-conscious stylization. The music is aggressively modern, and the lengthy takes (the average shot runs about a minute) are often shot with the low, straight-on camera reminiscent of early cinema.The film begins with a partial view of a door opening, inviting us into the story world, but obliquely. The film closes with a hand lifting a bundle of love letters from the sea and a voice-over (Oliveira’s) explaining how the novel came to be written. The images provide as overt a marking of a narrative’s beginning and its end as you could ask for, and one completely in keeping with the film’s balance between respect for artifice and its concern to let compromised passions leak through.

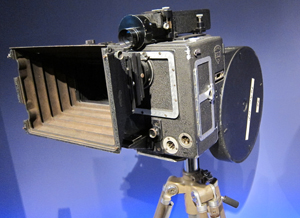

MoMI also hosts a splendid exhibition of media technology. One floor is a wonderland of cameras, sound rigs, printers, and projectors of all sorts, from film to TV and beyond. One favorite among many: A Mitchell VistaVision camera from 1954. It’s a funny-looking thing, but it took very crisp pictures. The horizontal film transport allowed larger and sharper images than the vertically-run formats that were normal for 35mm.

There are also displays devoted to screenplays, make-up, hairdressing, and special effects. I was especially taken with the finely detailed miniature for the Tyrell corporation building in Blade Runner.

In all, MoMI deserves all the praise it has gotten after its reopening. Rochelle Slovin, the founding director of the museum, started in 1981 and is retiring this week. She can be proud of what she and her colleagues have accomplished.

Jaywalking down Broadway

Wundkanal (Thomas Harlan, 1984).

Then there’s Lincoln Center, another long-time shrine of cinephilia. Like MoMI, the Film Society is in the process of building. The new complex will house theatres, a café, and a flexible lobby space. It’s scheduled to open in late spring.

The Film Society’s František Vlácil retrospective early in our stay brought this little-known filmmaker to my attention. I had seen only his best-known item, Marketa Lazarova (1967), and that quite a while back. So I was happy to catch his charming early short, Glass Skies (1958), and three features.

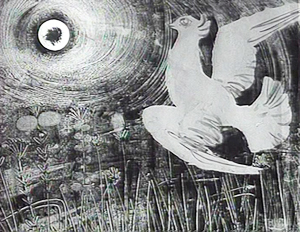

Vlácil mastered both filmic poetry and prose. The White Dove (1960) is a simple, lyrical story of two young people who never meet: a girl living in a beachside town and a wheelchair-bound boy in the city. Alternating sequences show them brought together by the homing pigeon that the girl sends out. The boy in a moment of thoughtless cruelty shoots the pigeon with his air rifle. Soon, with the help of an artist living in the same apartment house, he nurses the bird back to health. The film is richly shot in crisp, wide-angle black-and-white, and Vlácil exploits eyeballish imagery to create links between the girl’s seaside milieu and the artist’s Chagall-like paintings.

Like most filmmakers moving from the 1960s to the 1970s and from black and white to color, Vlácil recalibrated his visual design. Smoke in the Potato Fields (1976) gets your attention from the start with its disconcerting cutting during an airport departure. Laconic and elliptical, shot with long lenses and long takes, it tells an understated story of a middle-aged doctor moving to a small-town clinic. We get a cross-section of the townsfolk, from ambulance driver and gravedigger to censorious nurse and an unhappy married couple. The central drama concerns the doctor’s care for a tomboyish girl who gets pregnant and considers an abortion.

Shadows of a Hot Summer (1977), set in 1947 and shortly before the Communist takeover of the Ukraine, is more conventionally gripping. A farm family is held prisoner by rapacious resistance fighters. The taciturn father has no allies among the locals, who seem to resent his prosperity, and he dares not call attention to his plight. As in a Boetticher film, the hero plays his hand judiciously, mostly passive but carefully picking the battles he can win. The final sequence, precipitated when the marauders find him hoarding shotgun shells, is a taut, suspenseful exercise in action cinema. Shadows of a Hot Summer has daring stretches of silence and an unsettling score, along with discreet zoom shots typical of the period worldwide. These installments in the Vlácil retrospective show that we nonspecialists still probably underestimate the range of artistry that could be achieved in the apparently inhospitable atmosphere of Communist Eastern Europe.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

I’m a big fan (at a distance) of the Chauvet caves and their Ice Age imagery, so Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), a 3D tour of the site, was right up my alley. The film turned out to be a strong argument for 3D (as Kristin anticipated), since it lacked that sense of cardboard-cutout planes you usually get and really brought out volumes. The tigers, bison, and other wondrous creatures seemed to bulge and ripple across the walls.

The biggest revelation the Film Comment program held for me was the double bill of Thomas Harlan’s Wundkanal (Gunwound, 1984) and Robert Kramer’s Notre Nazii (Our Nazi, 1984). Wundkanal was made by Thomas Harlan as part of his crusade to expose the bad faith of postwar Germany, where many former Nazis held positions of power. Harlan’s father was the Nazi filmmaker Veit Harlan, and as Kent Jones pointed out in his illuminating introduction, the son seems to have taken upon himself the burden of guilt that his father should have felt.

Wundkanal proposes that a terrorist gang has kidnapped the respectable citizen Dr. Seibert, interrogated him about his murderous past, recorded the sessions on videotape, and eventually staged some of their own suicides as part of the exercise. Dr. S. is played by Alfred Filbert–himself a Nazi let out of prison for medical reasons. The whole production, then, becomes both a vision of Germany’s blindness to history and a trap for a man whom Thomas Harlan suggests has gotten off far too easily. “A new idea: to use the real criminal, to deceive him and convince him it was a film about him.”

Filmed by the great Henri Alekan, it is a phantasmagoria. We are in a sunless bunker jammed with old photos, thermos jugs, automatic pistols, video clips from a Harlan film, and other detritus: a sort of chamber-play version of a Syberberg no-man’s land. Questioned by offscreen interrogators, Dr. S. admits to his crimes plaintively. The hallucinatory quality of the exercise is enhanced by sound cuts that split a sentence into bits (sometimes clear and close, sometimes filtered through speakers) and a drifting camera that may start on Dr. S. but then wanders across the litter to end on a video image of Dr. S. testifying in another session, at which point the sound of that session may take over. In one passage, the camera tours the room and picks up several bits of Dr. S.’s testimony, in the real space and in several video monitors crowding the area.

Kramer’s Our Nazi is in a way a making-of for Wundkanal, but it’s also a powerful film in its own right. Acting as his own cameraman for the first time, Kramer (director of the classic militant films The Edge, Ice, and Milestones) takes us behind the scenes to show Thomas Harlan’s obsessions and to expose Filbert more directly than Wundkanal does. Harlan talks of the fatal love he had for his father, reflecting that the old man’s charm finally withered in the face of his inhuman complicity with the Reich. Intercut with this soliloquy are shots of Filbert being made up for his video scenes, as he talks of his dueling scars and his youth: “All the ambitious men became Nazis.”

Our Nazi gives us two disturbing confrontations, one with Kramer sitting Filbert down and charging him with crimes against humanity, the other more prolonged and painful. Harlan and the crew encircle their star and hurl accusations at him. This scene, glimpsed and abstracted in Wundkanal, pulls the viewer in different directions as the feeble old man tries to escape Harlan’s relentless recitation of Filbert’s war crimes. In the discussion with Kent Jones after the screenings, Paul McIsaac rightly called the Kramer film a demonstration of the concreteness that direct cinema can yield. Shot in Hi-8, Our Nazi counterbalances the abstract, somewhat detached artifice on display in Wundkanal. Kramer dwells on unexpected details, such as Alekan hesitating to autograph a souvenir production photo for old Filbert. The two movies need to be seen together because they engage in a crosstalk that yields provocatively different information, emotions, and cinematic resources.

Our month in New York went by all too fast. We seldom visit the city these days; I’m in Hong Kong more often than Manhattan. Our trip brought back memories of my undergrad visits from Albany in the 1960s (packing four films into a day-trip) and, during the 1970s, doing dissertation research and visiting friends and teaching for a semester at NYU. It also allowed me to get back in touch with some of my oldest friends, like Rich Acceta-Evans from junior-high days. And the trip reminded me of what a cosmopolitan film culture is like, with institutions like these and still others (Anthology Film Archives, MoMA, etc.) braving tough times to bring the right movies to lucky audiences.

Apart from those named above, I want to thank the friends we met with during our stay. Scott Foundas was particularly helpful on this entry. I gave talks at various venues, so I’m grateful to Malcolm Turvey of Sarah Lawrence College, to the NYU Film Studies faculty, and to Patrick Hogan at the University of Connecticut–Storrs. Special thanks to Ken Smith and Joanna Lee for arranging a visit to the Museum of Chinese in America for a discussion of Planet Hong Kong.

Speaking of Planet Hong Kong, I discuss The Valiant Ones in Chapter 8 there, as well as in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema. For a sensitive examination of Doomed Love, go to Tativille.

Some films in the Film Society’s Vlácil retrospective are available on DVD from Facets Multimedia. Wundkanal and Our Nazi have been issued on a single DVD edition with English subtitles, and it can be found on the Edition Filmmuseum site. Every film studies and filmmaking department should order it, I believe. See also “Truth or Consequences,” Kent Jones’ essay in Film Comment 46, 2 (May/ June 2010), 48-53, from which I’ve taken the Harlan quotation. Jones discusses other films, including Christoph Hübner’s 2007 study of Thomas Harlan, Wandersplitter, which is also available on a Filmmuseum disc. Thomas Harlan is one of the main interviewees in the documentary Kristin recently wrote about, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss.

For more coverage of the “Film Comment Selects” series, see R. Emmett Sweeney’s review on the Movie Morlocks site, with particularly discerning remarks on I Wish I Knew. Jesse Cataldo provides sharp commentary on Wundkanal at The House Next Door.

Alfred Filbert, confronted with the tattooed arm of an Auschwitz survivor (Our Nazi).

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

The East Is Red (1993).

DB here:

In about two weeks, we try something new here. It’s an experiment in self-publishing, like everything on this site, but this time we offer a new version of an oldish book.

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000. It sold pretty well for an academic book, shifting about 7000 copies through 2007. It was translated into Chinese twice, once in Hong Kong and once on the mainland. It also got encouraging reviews; I’ve put up links at the end of this entry.

At some point in 2008, Harvard University Press took the book out of print, a decision I learned about accidentally in spring of 2009. The story is here.

Since then, the book has become rather scarce; only about twenty copies are currently offered on Amazon. Rather than letting the poor thing fade away, I considered revising it for the web. The more I thought about it, the better the prospect looked. I could add as much to the text as I wanted. The text could be corrected, updated, and supplemented in the future. I could add photos, lots of them, and they could be in color. The text would be searchable. And instead of waiting nine to thirteen months to see the result, I could see it in weeks.

Moreover, readers could use the book as they liked. If it was presented as a pdf download, they could read it on a computer or on several models of e-book readers. They could also print out all or part of it. Interestingly, when I asked students and faculty if they’d use the book, nearly all said they’d print it, or let a facility like Kinko’s do it. All in all, it looked like an experiment worth trying.

[Insert montage of fluttering calendar pages here]

God of Gamblers (1989).

Since July I’ve spent virtually all my time on the book, with a break to go to the unmissable Vancouver film fest. Reworking the manuscript, watching and rewatching films, and preparing new material kept me from writing other things I had planned. No blog for Godard’s eightieth birthday, aiming to defend Film Socialisme as an intelligible part of his career. No web entry on the remarkable films of Kon Satoshi, creator of Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, and The Girl Who Leaped through Time. No discussion of the 1950s-1960s art-cinema canon in the light of Tino Balio’s fine new book on that period in U. S. film culture. No speculations on the psychological processes aroused by a movie’s opening scenes. Maybe next year.

Instead, apart from two quick entries provoked by Inception, I was absorbed in Hong Kong movies on film and DVD, notes from ten years of film festivals and conferences, and plenty of books and websites. Two blog entries, one on coincidence and the other on Jackie Chan’s Police Story, were chips from the workbench. As for my seeing recent releases, The Social Network and Megamind have been about it.

Now, after a month of fourteen-hour days, Planet Hong Kong redux is close to ready. I hope to make it available on this site during the week of 20 December.

The beast has grown in captivity. The first edition ran about 130,000 words; the new version adds 40,000 words. (In defense, I remind you of Adorno explaining why The Authoritarian Personality turned out so long: “We didn’t have enough time to make it short.”) There are over 150 new stills, all in color and many from 35mm prints. But no clips! These films are too beautiful to be reduced to those wretched mutants you get on YouTube. Besides, I don’t have the rights.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0 will not be free. My Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment are free online, but neither of those was revised, and we absorbed comparatively little of the costs of production. By contrast, the digital PHK is the fruit of a lot of paid labor. Heather Heckman and Mark Minett did excellent scanning and Photoshop tweaking, and Meg Hamel, our web tsarina, designed the book and is making it web-ready. I’m still reckoning the cost of the e-book, but it will be $20 or less. Payment will be rendered unto Caesar, aka Caesar Bordwell, via PayPal.

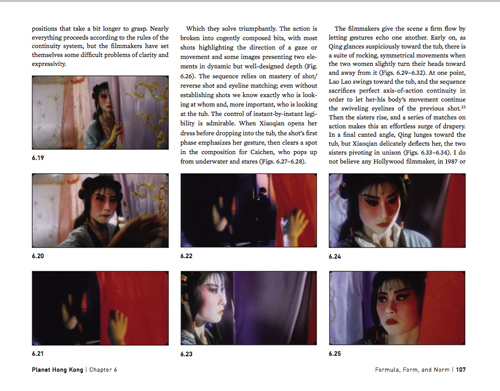

Here’s a sample page from our beta version. I’m still fiddling with the text, but the design looks to me like a nice compromise between the stability of a book page and the flow of a website. The file I’m using here is low-resolution, and this frame from it is a paltry 72 dpi jpeg, but the final pdf page should look very sharp. For curious boffins, the 35mm frame stills were scanned at 2000 dpi and reduced to 300 dpi for insertion. We don’t know yet how big the whole book’s file will be, but of course Meg will optimize it for downloading.

By the way: No, Wong Kar-wai did not invent the luscious image of the yearning woman.

Once the book is up, I plan to add a Hong Kong picture gallery to this site. It will include snapshots of celebs and fans from across the years 1995-2010.

ISNAQs (Infrequently, Sometimes Never, Asked Questions)

Enter the Dragon (1973).

PHK isn’t a comprehensive history of Hong Kong filmmaking; for that you must turn to Stephen Teo’s Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. Nor is it a fan’s guide to the wild and crazy side of this local cinema. Stefan Hammond’s two books handle that task nicely, and there are many similar handbooks since. Most strikingly, the fanboys have been usurped by the professors. A geyser of academic books and articles about Hong Kong cinema burst in the new millennium, along with invaluable documentation from the Hong Kong Film Archive and the Hong Kong International Film Festival. My book doesn’t rival these.

What does this book do, then?

I try to design my books in layers, with different implications and possibly different readerships, at each level. The first and founding layer of Planet Hong Kong is my effort to convey the sheer pleasure offered by this filmmaking tradition. I write as an enthusiast for other enthusiasts, and for potential converts. In this respect, PHK is an academic dressup of a noble gonzo tradition. Hong Kong cinema has benefited from the gusto of admirers like Ross Chen, Lisa Morton, Stephen Cremin, Grady Hendrix, Stefan Hammond, Chuck Stephens, Richard Corliss, David Chute, Howard Hampton, and other lively writers. This cinema inspires dazzling, sometimes headbanging appreciations from critics.

Next there’s a historical layer. Hong Kong cinema is, I’m convinced, an important “national school” in world film history. It shaped global popular culture to a degree matched only by the westerns and gangster films turned out by the Hollywood studios. Every video game that includes martial arts, every American action movie, and every comic book showing a sword-wielding superhero owe a lot to Bruce Lee and the cinema he springs from. Less obviously, Hong Kong innovated approaches to film form and style that remain striking today. When I wrote the book, this artistic heritage was almost completely unappreciated, by both general audiences and specialized film scholars. The situation is a little better now, but the case always needs restating. Through close analyses of many films and sequences, the book tries to show the originality and force of the Hong Kong touch.

Another layer up, the book asks how popular cinema works. The clichéd split between “art” and “business” isn’t much help in understanding mass-entertainment film. The business relies on artistic traditions, and those traditions in turn are born from and shaped by industrial factors–not just constraints but also enabling opportunities. Hong Kong film provides a case study in how a mass-entertainment movie builds its effects on genre, star appeal, storytelling strategies, and stylistic tactics. It shows vividly how a media industry relies on conventions, and how artists tap those, stretch them, and sometimes twist them out of recognition. My interviews with several writers, directors, choreographers, and actors helped me understand the ways that creativity could be fostered by craft traditions.

At the most general level, PHK is a small-scale demo of an approach to asking questions about cinema. It shows how we might systematically study the principles of construction informing popular filmmmaking. Stealth poetics, in other words.

The old and the new

Leave Me Alone (2004).

The big changes in Asian cinema of the last decade make the original book something of a historical artifact itself. I did the research across the 1990s and wrote nearly all of it in 1998. Its emphases reflect issues circulating in fan and academic culture at that time. DVDs, introduced in 1997, had not become widespread, and VCDs were unwatchable. (Still are.) Most of the films that mattered had to be studied on film copies, although laserdiscs offered a passable backup in some cases. VHS tapes were seldom letterboxed, but laserdiscs often were.

The biggest constraint on the book was the scant availability of Shaw Brothers films on any format. Thanks to the Hong Kong International Film Festival, trips to archives, and the film collector’s market, I was able to see quite a few, but nothing like what’s available now in the massive and restored Shaw DVD library. Consequently, apart from the work of King Hu, Chang Cheh, and Lau Kar-leong, PHK doesn’t deal with the very interesting output of the territory’s most famous company. Fortunately, Shaws has been carefully studied in the years since my book, in a massive volume from the Hong Kong Film Archive and in Poshek Fu’s China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema. For my part, this web essay and these blog entries try to make amends.

I could have recast PHK top to bottom, but I wasn’t convinced that I could come up something as pointed as the original. The text has been corrected, of course, and patches have been recast for greater clarity. It has also been enhanced by a few more examples, film sequences I referred to in passing but could not illustrate because I couldn’t find a print or couldn’t include color images. The chief updating is a series of sections added to the back end.

So here is what the book now looks like.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

Chapter 5 surveys the industry, with emphasis on filmmakers’ craft traditions (how stories are planned, scenes are cut, and so on). The interlude that follows takes Tsui Hark as an instance of a director who creatively reworked such traditions. Chapters 6 and 7 go into the most detail about the aesthetics of Hong Kong film, surveying the dynamics of genre, the star system, visual style, and plot construction. Between these two chapters is sandwiched an interlude devoted to Wong Jing, the most disreputable major filmmaker in the territory. The longest chapter, the eighth, explores the distinctive aesthetic of action pictures, from martial arts to contemporary crime movies. The interlude that follows discusses three outstanding directors in the martial-arts tradition: Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, and King Hu. The final chapter of the original book considers how the premises of popular cinema can be adapted to create “art films.” The principal, but not sole, example is the work of Wong Kar-wai. The original book concluded with an analysis of Chungking Express.

The new material in this edition starts with a chapter on changes in the film industry since 1997. That’s followed by an interlude focusing on the Infernal Affairs trilogy, which was as you know the source for The Departed. The next chapter considers how the artistic trends surveyed in the first edition have changed over the last ten years or so. While discussing developments in genre, storytelling, technology, and style, the chapter includes sections on Stephen Chow (particularly Shaolin Soccer and Kung-Fu Hustle), Wong Kar-wai (In the Mood for Love and 2046), and Johnnie To Kei-fung. The final interlude is a more in-depth discussion of To’s crime films and their relation to the indigenous action-movie tradition. At the very end is a new bibliography and endnote citations.

Readers not drawn to Hong Kong cinema might find my more general arguments of interest. For example, I suggest that Hong Kong shows us how important regional and diasporan networks are in creating and maintaining a film culture. To the claim that films reflect their societies, I reply that Hong Kong films suggest a different way to think about such a dynamic, using the model of cultural conversation. Readers interested in fandom should find something intriguing in the story of how cultists around the world helped establish Hong Kong film as a cool thing in the early 1990s. I also argue against the tendency in film studies to assume that when a film tradition doesn’t follow the rules of classical plot construction it must be based on something called “spectacle.” I suggest instead that we need to study principles of episodic plotting, which are probably quite common in popular art generally. In these and other areas, I wanted to use this cinema as a way into thinking about popular moviemaking as a whole.

After World War II, a tailor shop in Hong Kong put up a sign: “Reopening soon. Sooner if possible.” The same goes for me: Planet Hong Kong Redux is coming soon. Sooner if possible.

Here are some reviews of Planet Hong Kong by Richard Corliss in Time Asia (said I typed in my shorts with a beer at my elbow), Paul F. Duke in Variety (liked the book, worried that I talked like a Marxist), an anonymous writer in The Economist (said I’m a scholar who writes as a fan), Steve Erickson in Senses of Cinema (noticed my appreciation of stars), Mina Shin for Framework (developed my suggestions about festival culture), Leon Hunt in Scope (liked book, called me an empiricist, which tickles me down to my sense data), and Shelly Kraicer at chinesecinemas.org (as usual, more generous than he should be).

The most unexpected mention of the book seems to have vanished from the web. A New York critic who is surprisingly easy to outrage made an interesting attempt to charge me with synergistic marketing. He proposed, in the midst of a pan of Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide, that PHK was a covert attempt to promote Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had just won acclaim at Cannes. I wrote James Schamus, writer-producer of CTHD: “Now that we’ve been found out, we have to abandon our scheme to reprint my Dreyer book so as to coincide with Ang’s remake of Ordet.”

My quotation from Adorno may be apocryphal.

P.S. 13 December: Thanks to Daniel Erdman, I’ve now got the synergistic review mentioned above. It’s here. Thanks as well to Antti Alanen, who writes from Finland:

About ‘no time to be short’: quite possibly Adorno said so, and you are in good company:

Blaise Pascal: “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte” (The Provincial Letters). J.W. von Goethe: »Da ich keine Zeit habe, dir einen kurzen Brief zu schreiben, schreibe ich dir einen langen« (letter to his sister Cornelia, but Goethe had apparently learned this from Cato and Cicero).

And soon after that came from Antti, Philippe Theophanidis wrote to point out the Pascal source as well. Once more I pay for the lack of a classical education!

Golden Scissors Part I (1963). Famous martial-arts choreographer and director Lau Kar-leung is on the far right. Source: Hong Kong Film Archive.

The ten best films of … 1920

High and Dizzy

Kristin here:

Three years ago, we saluted the ninetieth anniversary of what was arguably the year when the classical Hollywood cinema emerged in its full form. The stylistic guidelines that had been slowly formulated over the past decade or so gelled in 1917. We included a list of what we thought were the ten best surviving films of that year.

In 2008 we again posted another ten-best list, again for ninety years ago. This annual feature has become our alternative to the ubiquitous 10-best-films-of-2010 lists that print and online journalist love to publish at year’s end. It’s fun, and readers and teachers seem to find our lists a helpful guide for choosing unfamiliar films for personal viewing or for teaching cinema history. (The 1919 entry is here.)

There were many wonderful films released in 1920, but, as with 1918, I’ve had a little trouble coming up with the ten most outstanding ones. Some choices are obvious. I’ve known all along that Maurice Tourneur’s The Last of the Mohicans (finished by Clarence Brown when Tourneur was injured) would figure prominently here. There are old warhorses like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Way Down East that couldn’t be left off—not that I would want to.

But after coming up with seven titles (eight, really, since I’ve snuck in two William C. de Mille films), I was left with a bunch of others that didn’t quite seem up to the same level. Sure, John Ford’s Just Pals is a charming film, but a world-class masterpiece? A few directors made some of their lesser films in 1920, as with Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow or Lubitsch’s Sumurun. Seeing Frank Borzage’s legendary Humoresque for the first time, I was disappointed—especially when comparing it with the marvelous Lazy Bones of 1924. (Assuming we continue these annual lists, expect Borzage to show up a lot.) Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1920, and Keaton and Lloyd were still making shorts, albeit inspired shorts. Mary Pickford’s only film of the year, the clever and touching Suds, is a worthy also-ran. Choosing Barrabas over The Parson’s Widow or Why Change Your Wife? over Sumurun has a certain flip-of-the-coin arbitrariness, but we wanted to keep the list manageable. But they all repay watching.

The year 1920 can be thought of as a sort of calm before the storm. In Hollywood a new generation was about to come to prominence. Griffith would decline (Way Down East may be his last film to figure on our lists). Borzage will soon reach his prime, as will Ford. Howard Hawks will launch his career, and King Vidor will become a major director. The great three comics, Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd will move into features. In other countries, an enormous flowering of new talent will appear or gain a higher profile: Murnau, Lang, Pabst, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dozhenko, Kuleshov, Vertov, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Jean Epstein, Pabst, Hitchcock, and others. The experimental cinema will be invented, and Lotte Reiniger will devise her own distinctive form of animation. Watch for them all in future lists, which will be increasingly difficult to concoct

In the meantime, here’s this year’s ten (with two smuggled in). Unfortunately, some of these films are not available on DVD. They should be.

The great French emigré director Maurice Tourneur figured here last year for his 1919 film Victory. The Last of the Mohicans is just as good, if not better. I haven’t read the Cooper novel, set during the French and Indian War, but it’s obvious that Tourneur has pared down and changed the plot considerably. The sister, Alice, is made a less important character, with the plot focusing on two threads: the Indian attack on the British population as they leave their surrendered fort and on the virtually unspoken attraction between the heroine Cora and the Mohican Indian Uncas. The seemingly impassive gazes between these characters, forced to conceal their attraction, convey more passion than many more effusive performances of the silent period. The actress playing Cora also wore less makeup than was conventional, de-glamorizing her and making her a more convincing frontier heroine.

The film is remarkable for its gorgeous photography, with spectacular location landscapes, some apparently shot in Yosemite (below left). Tourneur’s signature compositional technique of shooting through a foreground doorway or cave opening or other aperture appears frequently (below right). (Brown’s account of the filming in Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By makes it sound as though he shot most of the picture, but in watching the film I find this hard to believe.)

Finally, the film stands out from most Hollywood films of its day for its uncompromising depiction of the ruthless violence of the conflict between the British and those Indians allied with the French. The scene in which the inhabitants of the fort leave under an assumed truce and are massacred can still create considerable suspense today, and the outcome puts paid to the notion that all Hollywood films end happily.

The word melodrama gets tossed around a lot, and many would think of much of D. W. Griffith’s output as consisting of little besides melodramas. But Way Down East is the quintessential film melodrama. An innocent young woman (Lillian Gish) is lured into a mock marriage and ends up deserted and with a baby. The baby dies and she finds a place as a servant to a large country family, where the son (Richard Barthelmess) falls in love with her. Her sinful status as an unwed mother leads the family patriarch to order her out, literally into the stormy night. She ends up on an ice flow, headed toward a waterfall. Along the way there’s comic relief from some country bumpkins and a naive professor who falls for the hero’s sister. It all works, partly because Griffith treats the main plot with dead seriousness and partly because Gish elicits considerable sympathy for her character.

Not only is it a great film, but it provides a window into the past, preserving a popular nineteenth-century play and giving insight into the drama of that era. It’s hard to think of another feature film that conveys such a genuine record of the Victorian theater, directed by a man who had made his start on the stage of the same period. (Unfortunately the film does not survive complete. The Kino version linked above is from the Museum of Modern Art’s restoration, which provides intertitles to explain what happens during missing scenes.)

Way Down East displayed a conservative attitude toward sex that was rapidly receding into the past–at least as far as the movies were concerned. The same year saw two films that set the tone for the Roaring ’20s in their more risqué depiction of romantic relationships: Cecil B. De Mille’s Why Change Your Wife? and Mauritz Stiller’s frankly titled Swedish comedy Erotikon.

De Mille has featured on our previous lists, for Old Wives for New in 1918 and Male and Female in 1919. Why Change Your Wife? ramped up the sexual aspect of the plot, however, as a Photoplay reviewer made clear: “”Having achieved a reputation as the great modern concocter of the sex stew by adding a piquant dash here and there to Don’t Change Your Husband, and a little more to Male and Female, he spills the spice box into Why Change Your Wife?” The plot is not nearly as daring as this suggests. Gloria Swanson plays a wife who is straight-laced and intellectual, driving her husband to spend time with a stylish woman who tries to seduce him. Yet he flees after one kiss, and after his wife divorces him on the assumption that he has cheated on her, he marries the seductress. The heroine discovers the error of her ways and becomes sexy in her dress and behavior. As a result the husband regains his old love for her, and they remarry. No actual adultery occurs, and the first marriage is affirmed with a happy ending.

Why Change Your Wife? may have seemed more daring because De Mille here externalizes the shifting relationships through the costumes to the point where no viewer could miss the implications. Initially the wife’s demure dresses mark her as prudish, while the woman who lures her husband away is dressed like a vamp. Once the wife lets go, she dons similar revealing, expensive designer clothes. As a result, the male members of the audience might revel in a fantasy of their ideal wife, and the women would delight in displays of fashions most of them could never own in reality. It proved a successful combination. We tend to forget it now, but the 1920s was full of variants and imitations of Why Change Your Wife?, often featuring a fashion-show scene that was nothing but a parade of models in outlandish clothes. (Early Technicolor was sometimes shone off in such sequences.) Top designers like Erté were recruited to bring their talents to such films.

Fashion as a selling point in films remains with us. The glossy new version of The Hollywood Reporter, recently decried by David, now has a regular “Hollywood Style” section. The November 24 issue ran “Costumes of The King’s Speech,” and the December 1 issue describes “Fashions of The Tourist,” with photos of Angelina Jolie in her various costumes. In addition to shots of the stars, both articles feature enticing close-ups of lipstick, shoes, jewelry,and purses.

A double feature of Why Change Your Wife? and Erotikon would provide a vivid sense of the differing moral outlooks of mainstream America and Europe in the post-war years. In Erotikon, the situation is reversed. An absent-minded entomologist neglects  his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

Erotikon reflects some of the influences from Hollywood that were seeping into European films after the war. Sets are larger, cuts more frequent (though not always respecting the axis of action), and three-point lighting crops up occasionally. Yet Stiller maintains the strengths of the Scandinavian cinema of the 1910s, with skillful depth staging (left) and a dramatic use of a mirror. In the opening of a crucial scene where the sculptor confronts the wife with her adultery, tension builds because she does not know he is watching her until she sees him in the mirror (see bottom). Still, apart from its European sophistication, Erotikon could pass for an American film of the same era. Stiller and lead actor Lars Hansen would both be working in Hollywood by the mid-1920s.

I can’t allow the nearly unknown director William C. de Mille to take up two slots this year, though it’s tempting. William’s career was shorter than that of his much better-known brother Cecil. It peaked in 1920 and 1921, though, and I still look back fondly on the films by him that were shown in “La Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival of 1991. That year saw a large retrospective of Cecil’s films, and the organizers wisely decided to include a  sampling of William’s surviving work.

sampling of William’s surviving work.

The two men’s approaches were markedly different. Where Cecil by this point was setting his films among the rich and using visual means like costumes to make the action crystal-clear to the audience, William was more likely to favor middle-class settings with small dramas laced with humor and presented with restrained acting and small props. Despite William’s skill as a director and his ability to create sympathy for his characters, he never gained much prominence, especially compared to his brother. He retired from filmmaking in 1932, at the relatively young age of 54. Yet obviously he was attuned to his brother’s style, having written the script for Why Change Your Wife? It may be characteristic of the two that Cecil capitalized the De in De Mille, while William didn’t.

Relatively few of William’s films survive, but these include two excellent films from 1920, Jack Straw and Conrad in Quest of His Youth. I don’t remember Jack Straw well enough to describe it. It involved the hero’s falling in love with a woman when they both live in the same Harlem apartment building. When her family becomes rich, Straw disguises himself as the Archduke of Pomerania in order to woo her. Sort of a Ruritanian romance but played out in the U.S.

I remember Conrad in Quest of His Youth better. The hero returns from serving as a soldier in India. He feels old and decides to try and recover his youth. The first attempt comes when he and three cousins agree to return to their childhood home and indulge themselves in the simple pleasures of their youth. Eating porridge for breakfast is a treasured memory, but the group discovers that this and other delights are no longer enjoyable to them as adults. Conrad goes on to seek romance elsewhere and eventually finds a woman who makes him feel young again. The film’s poignant early section manages in a way that I’ve never see in any other film to convey both nostalgia for the joys of childhood and the sad impossibility of recapturing them.

Neither film is available on DVD. Indeed, I couldn’t find an image from either to use as an illustration. The only picture I located is a rather uninformative one from Conrad in Quest of His Youth, above right, which I scanned from William C.’s autobiography (Hollywood Saga, 1939). It’s no doubt an indicator of William’s modesty that the frontispiece of this book is a picture of his brother directing a film.

Maybe this entry will serve as a hint to one of the DVD companies specializing in silent movies that these two titles deserve to be made available. They’re high on my list of films I would love to see again.

Most people who study film history see Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari very early on, though they probably push it to the backs of their minds later on. I have a special fondness for Caligari precisely because I did see it early on. I took my first film course, a survey history of cinema, during my junior year. Maybe I would have gotten hooked and gone on to graduate school in cinema studies anyway, but it was Caligari that initially fascinated me. It was simply so different from any other films I had seen in what I suddenly realized was my limited movie-going experience. It inspired me to go to the library to look up more about it, a tiny exercise in film research.

Some may condemn it as stage-bound or static. Despite its painted canvas sets and heavy makeup, however, it’s not really like a stage play. Many of the sets are conceived of as representing deep space, though often only with a false perspective achieved by those painted sets:

Still, in an era when experimental cinema was largely unknown, Caligari was a bold attempt to bring a modernist movement from the other arts, Expressionism, into the cinema. It succeeded, too, and inaugurated a stylistic movement that we still study today.

I haven’t watched Caligari in years (I think I know it by heart), but I’m still fond of it. The plot is clever grand guignol. It has three of the great actors of the Expressionist cinema, Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, and Lil Dagover, demonstrating just what this new performance style should look like. The frame story retains the ability to start arguments. The set designs area dramatically original, and muted versions of them have shown up in the occasional film ever since 1920. Even if you don’t like it, Caligari can lay claim to being the most stylistically innovative film of its year.

As I did for our 1918 ten-best, I’m cheating a bit by filling one slot of the ten with a pair of shorts by two of the great comics of the silent period. Both have matured considerably in the intervening two years. In 1918, Harold Lloyd was still working out his “glasses” character. By this point he is much closer to working with his more familiar persona. Similarly, in 1918, Buster Keaton was still playing a somewhat subordinate role in partnership with Fatty Arbuckle. In 1920, he made his first five solo shorts, co-directing them with Eddy Cline.

The Lloyd film I’ve chosen is High and Dizzy, the second short in which he went for “thrill comedy” by staging part of the action high up on the side of a building. (See the image at the top.) Four years later he would build a feature-length plot around a climb up such a building in Safety Last, one of his most popular films. In High and Dizzy, Harold is not quite the brash (or shy) young man he would soon settle on as the two variants his basic persona. The opening shows him as a young doctor in need of patients. He soon falls in love with the heroine, and through a drunken adventure, ends up in the same building where she lies asleep. She sleepwalks along a ledge outside her window, and when Harold goes out to rescue her, she returns to her bedroom and unwittingly locks him out on the ledge. The film is included in the essential “Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection” box-set, or on one of the two discs in Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection,” Vol. 2.”

Neighbors was the fifth of the five Keaton/Cline shorts made in 1920. (It was actually released in early 1921, but I’ll cheat a little more here; there are other Keaton films to come in next year’s list.) It’s a Romeo and Juliet story of Keaton as a boy in one working-class apartment house who loves a girl in a mirror-image house opposite it. Two bare, flat yards with a board fence running exactly halfway between them separate the lovers. Naturally the two sets of parents are enemies.

Lots of good comedy goes on inside the apartment blocks, but the symmetrical backyards and the fence inspire Keaton. We soon realize that his instinctive ability to spread his action up the screen as well as across it was already at play. The action is often observed straight-on from a camera position directly above the fence, so that we–but usually not the characters–can see what’s happening on both sides. For one extended scene involving policemen, Keaton perches unseen high above them, hidden. Even though we can’t see him, the directors keep the framing far enough back that the place where we know he’s lurking is at the top of the frame as we watch the action unfold. The playful treatment of the yard culminates in an astonishingly acrobatic gag that brings in Keaton’s early music-hall talents.

The boy and girl have just tried to get married, but her irate father has dragged her home and imprisoned her in a third-floor room. She signals to Keaton, across from her in an identical third-floor window. A scene follows in which two men appear from first- and second-story windows below Keaton, and he climbs onto the shoulders of the two men below. This human tower crosses the yard several times, attempting to rescue the girl; each time they reach the other side, they hide by diving through their respective windows:

They perform similar acrobatics on the return trips to the left side, carrying the bride’s suitcase or fleeing after her father suddenly appears.

Neighbors is included as one of two shorts accompanying Seven Chances in the Kino series of Keaton DVDs, available as a group in a box-set.

Our final two films lie more in David’s areas of expertise than mine, so at this point I turn this entry over to him.

DB here:

With Barrabas Feuillade says farewell to the crime serial. Now the mysterious gang is more respectable, hiding its chicanery behind a commercial bank. Sounds familiar today. As Brecht asked: What is robbing a bank compared with founding a bank?

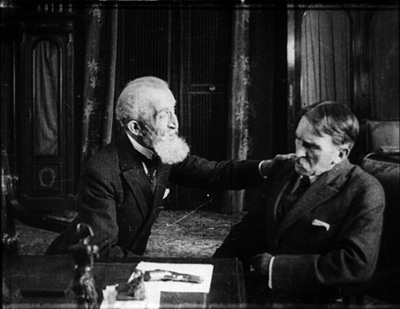

Over it all towers another mastermind, the purported banker Rudolph Strelitz. In his preparatory notes Feuillade called him “a sort of sadistic madman, a virtuoso of crime . . . a dilettante of evil.” Against Strelitz and his Barrabas network are aligned the lawyer Jacques Varèse, the journalist Raoul de Nérac (played by reliable Édouard Mathé), and the inevitable comic sidekick, once again Biscot (so perky in Tih Minh).

The film’s seven-plus hours (or more, depending on the projection rate) run through the usual abductions, murders, impersonations, coded messages, and chases. But there’s little sense of the adventurous larking one finds in Tih Minh (1919), in which the hapless villains keep losing to our heroes. The tone of Barrabas is set early on, when Strelitz forces an ex-convict into murder, using the letters of the man’s dead son as bait. The man is guillotined. The epilogue rounds things off with a series of happily-ever-afters in the manner of Tih Minh, but these don’t dispel, at least for me, the grim schemes that Strelitz looses on a society devastated by the war. Add a whiff of anti-Semitism (the Prologue is called “The Wandering Jew’s Mistress”), and the film can hardly seem vivacious.

According to Jacques Champreux, Barrabas was the first installment film for which Feuillade prepared something like a complete scenario, although it evidently seldom described shots in detail. The film has a quick editing pace (the Prologue averages about three seconds per shot), but that is largely due to the numerous dialogue titles that interrupt continuous takes. With nearly twenty characters playing significant roles and some flashbacks to provide backstory, there’s a lot of information to communicate.

Of stylistic interest is Feuillade’s movement away from the commanding use of depth we find in Fantômas and other of his previous masterworks. Here the staging is mostly lateral, stretching actors across the frame. Very often characters are simply captured in two-shot and the titles do the work, as if Feuillade were making talking pictures without sound. Once in a while we do get concise shifting and rebalancing of figures, usually around doorways. Here Jacques vows to go to Cannes and tell the police of the kidnapping of his sister. As Raoul and Biscot start to leave, Jacques pivots and says goodbye to Noëlle, creating a simple but touching moment of stasis to cap the scene.

Full of incident but rather joyless, Barrabas will never achieve the popularity among cinephiles of the more delirious installment-films, but it remains a remarkable achievement. The ciné-romans that would follow until Feuillade’s death in 1925 would lack its whiff of brimstone. They would mostly be melodramatic Dickensian tales of lost children, secret parents, strayed messages, and faithful lovers. Barrabas is not available on DVD.

You might think that a movie that opens with a frowning old man studying a skeleton would also be somewhat unhappy fare. Such isn’t actually the case with Victor Sjöström’s generous-hearted Mästerman, a story of a village pawnbroker obliged to take a young woman as a housekeeper. With his stovepipe hat and air of sour disdain, Samuel Eneman, known to the village as Mästerman, is a ripe candidate for rehabilitation. Once Tora is installed and has put a birdcage (that silent-cinema icon of trapped womanhood) on the window sill, the scene is set for Mästerman’s return to fellow feeling. But she is there merely to cover the debts and crime of her sailor boyfriend, and eventually Eneman realizes he must make way for young love. The drama is played out in front of the townspeople, and as often happens in Nordic cinema (e.g., Day of Wrath, Breaking the Waves) the community plays a central role in judging, or misjudging, the vicissitudes of passion.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

For a valuable source on Feuillade’s preparation for Barrabas and other of his works see Jacques Champreux, “Les Films à episodes de Louis Feuillade,” in 1895 (October 2000), special issue on Feuillade, pp. 160-165. I discuss Feuillade’s adoption of editing elsewhere on this site.

Tom Gunning provides an in-depth discussion of Sjöström’s style at this period in “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930, ed. John Fullerton and Jan Olsson (Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), pp.204-231. For more on some of the directors discussed in this entry, check the category list on the right.

Erotikon.