Archive for the 'Film history' Category

The Cross

The Puffy Chair (2005).

Mark: [The actors] need to improvise. They need to find the moments, and we don’t let them lean on the script too much. We want them to try to reinvent some of the dialogue and make it fresh.

Jay: We don’t do any blocking. Our whole goal is just to set up a room and basically foster an interaction that we feel is interesting and real.

Mark: And spontaneous.

Jay: And spontaneous.

Jay and Mark Duplass, talking of their new film Cyrus.

DB here:

We don’t do any blocking. Dude, we noticed. In The Puffy Chair, the Duplass brothers typically settle the actors into one spot and pan or cut between them.

Seldom do the characters move around the setting. When they do, it’s usually by means of a walk-and-talk traveling shot that transitions to the next static layout of actors.

We are talking about filmmakers who refuse the challenge of staging.

At the other extreme of budget and commercial clout, consider another film by two brothers. In The Matrix Reloaded, Neo meets the Oracle in the virtual courtyard and sits on a bench with her.

The whole scene, which runs nearly seven minutes, contains 94 remarkably static shots. After Neo settles on the bench beside her, we get simple reverse shots—lots of them, mostly one per line of dialogue. The setups are maniacally repeated. There are thirty-one iterations of the first framing below and eighteen of the second.

The only variation is a slightly tighter framing on each character, creating another brace of single setups during Neo’s acknowledgement of his dream of Trinity’s death. Each of these gets nine iterations.

Sustained two-shots would have let the actors do more with their upper bodies, but in this string of singles, faces and dialogue have to present Neo’s reactions to his new mission to save Zion. Granted, there are seven shots showing both Neo and the Oracle in the same frame, but these are very brief and seem to be there simply to provide beats and add some variety to the load of exposition the scene must carry.

Breaking the scene up so much has interesting rhythmic implications. Paradoxically, our movies are cut very fast but they feel rather slow (and run very long). When we need a cut to see a character’s reaction, a scene plays out more slowly than if the characters were held in the same frame for a significant period. Then we might see Neo’s reactions while the Oracle is speaking, rather than having to wait for them afterward.

But my main point is that the actors are planted in one spot. Like the Duplasses, the Wachowski brothers have felt no need to imagine the characters’ interaction through blocking. Indeed, when shooting a conversation, most of today’s filmmakers seem happiest if the actors stay riveted in place—standing, seated, riding in a car, typing at a computer terminal. Improvised cinema or storyboard cinema: Both camps are refusing the challenge of staging.

In some books and some web entries (most recently, here and here and here and here), I’ve tried to trace the rich tradition of ensemble staging. From almost the start of cinema, filmmakers have explored creative ways of moving actors around the set, aiming at both engaging storytelling and pictorial impact. Since the 1960s, on the whole, this tradition has been waning. Now, I fear, it has nearly disappeared.

I’m not going to reiterate those earlier arguments. Instead I want to talk about one simple staging tactic that directors almost never employ today. I offer it at no cost to young directors. Try it! You might get a taste for a range of cinematic expression that is nowadays neglected.

Cross and double cross

Assume you have two characters in a set. At a crucial moment, you invent some business that lets them exchange places, so that the one on the left winds up on the right, and vice-versa. At a minimum, this gives you visual variety; it keeps the viewer’s attention engaged by refreshing the composition. It can of course also heighten dramatic impact.

Naturally, we expect to find the Cross in the first golden age of cinematic staging, the 1910s. Here’s a case that combines the cross with depth staging, from the Doug Fairbanks picture The Matrimaniac (1916).

Marna and the Court officer have switched places in the frame. Note especially that her movement to the right, clearing our view of the officer at the door, is motivated by her hesitation at following him. Actually such moments probably don’t need much motivation; the flow of the action is so quick that no viewer will ask why she moved to the right, since our attention is on what her action reveals.

One way to motivate the Cross is to have A turn sharply away from B but keep talking. This is a bit of actor’s business that seems far more common in the classical era of moviemaking. Here is an excerpt from a single-shot scene in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). Brennan tries to console Mrs. Mrs. Mims, who has realized that her husband betrayed her. He enters the shack and then walks past her, as if considering exactly how to calm her.

This has been the prelude to a more intense confrontation. She comes closer to the camera, and Brennan joins her, forcing her to look at him as he says they must concentrate on staying alive.

In Demy’s Lola (1961) the Cross is motivated by the urge to offer another emphatic view of the protagonist. Roland has been talking to the two mother-figures who run the café he frequents. He’s dragging himself off to work as Jeanne fetches her radio from the bar and goes into the back room. We get two Crosses.

The shot’s climax comes when Roland pauses in the foreground and says: “One day I’ll go away too.” Again, a key character is turned from the other but continues to speak.

No need to cut in to a close-up because Roland’s face is perfectly visible. Just as important, while his face shows a certain reverie, his nervousness is conveyed by the way he waggles the novel in his hand. The actor is given a chance to act, not just with line reading and facial expression but with his slumped posture and his arms—one casual, the other in anxious motion. Taken together, the body and the face present Roland’s confusion.

Crossfire

Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949) yields many offhand instances of the Cross, indicating how taken for granted the technique was in studio films. When the slippery Fiske invites Joan in, she comes to the left foreground and he moves to the right side of the frame to shut the door.

Approaching her by stepping into medium shot, he tries to warm her up, but she slaps him. Cut in to underscore her reaction. “What did you expect—kisses?”

In a return to the earlier setup, she turns away and executes another Cross, settling on the sofa.

Simple and concise; some would say banal. But compared to The Puffy Chair and The Matrix Reloaded, it looks brisk. The characters move easily through the frame without camera arabesques, and the medium shot is saved for the slap. The single of Joan adds another spike to the drama. Close-ups no longer rule but are used for momentary emphasis.

So the Cross can be sustained by cutting and camera movement. In The Lady Is Willing, Liza has found a baby and called a pediatrician. Director Mitchell Leisen gives us an over-the-shoulder shot of her and at the close of it she walks around Dr. McBain’s arm, with her feathery hat brushing his face.

If the shot were sustained with a pan, we’d have a Cross, but instead there’s a cut to Liza continuing the movement. McBain turns to watch her.

He starts to follow her diagonally. When she pauses to face him, the Cross is completed.

They leave the room. After a cutaway shot showing Liza’s secretary, the camera pans to follow McBain into depth washing his hands. When he comes through the door past Liza, we get another Cross.

With positions switched, the camera travels with her as she catches up with him in a medium shot. He is opening his medical bag.

This pause enables Leisen to underscore a key line of dialogue. “I detest children of all ages. I detest infants particularly.”

One more Cross and the shot is done. The camera pans again to follow McBain bending over the child, and Liza slips into the shot behind him, remonstrating with him. “A man who dislikes children simply can’t be a baby specialist.”

As so often, the Cross is used to present one character turning from another, or one trying to catch up with another who for dramatic reasons plows ahead. And the Cross favors a moderate depth, not the eye-smiting foregrounds of Welles but something less aggressive. In these ways, the simple device can participate in a broader pattern of fluid craftsmanship. The action can unfold in a clean rhythm, consistent with what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis.” Story points arise smoothly out of the flow of behavior. Actors get a chance to use their whole bodies, to create character through posture or stance, or even the angle of the elbows. Imagine if Dietrich, in the left shot just above, had sauntered to McBain with her hand on her hip as she does in so many other movies; the scene would take on a different tint.

When thinking about staging, we usually invoke Renoir or Ophuls or Jancsó, directors who integrate complex choreography with complicated tracking shots. (They also use the Cross a lot.) My examples try to show that even simple camerawork can enhance the performers’ grace. Nor do they have to execute the calisthenics on display in the office scenes of His Girl Friday. The modest moves we see in The Big Steal and The Lady Is Willing are within the grasp of eager filmmakers and game actors.

Cross purposes

I don’t have a good explanation for why such simple staging tactics have gone out of fashion. It’s too easy to cite laziness or lack of imagination, though they may play a role. I wonder as well if complicated staging is much taught in film schools. More specifically, improvisational methods may actually inhibit creative blocking. An actor who’s winging it may be reluctant to shift around the set, for fear that this creates new problems for framing or lighting or the other performances. Better, the actor may think, to concentrate on line readings, expressions, and other things that she can control while staying rooted to the spot. And maybe our directors don’t want to work their actors too hard, especially when the actors are beginners or nonprofessionals, as we find in indie filmmaking. Yet some masters of supple, intricate staging, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, employ untrained performers.

Contemporary directors may have a more principled objection to the older staging style: It’s too artificial. In real life, people mostly chat with each other when they’re sitting down, or walking, or riding in a car. Static staging, some might say, captures the passive nature of everyday interactions.

But dramatic narrative typically doesn’t consist of ordinary life. A film offers heightened, focused, pointed encounters, shot through with meaning and feeling. The actors and the filmmaker have a chance to sharpen the viewer’s perception of the situation and pass along the moment-by-moment play of thought, emotion, and action. There are both loud and quiet ways of doing this. Antonioni’s famously “dedramatized” scenes are staged as dynamically as the more florid moments of Visconti or Fellini. Emotionally subdued action can be shaped just as precisely as passionate outbursts, and it can carry its own impact.

I should make it clear that I’m not asking anybody to embrace a single style. Sometimes stand-and-deliver and intensified continuity editing work very well. Directors will always seek specific solutions to the problems of a scene. But I don’t see much variety in the solutions many people now pursue. I don’t see evidence that most young filmmakers around the world are aware that traditions furnish lots of alternatives.

In earlier periods, some directors were as editing-oriented as today’s mainstream ones, while other directors adopted more staging-driven approaches. But either sort had a broader palette than what we see today. Any accomplished director could stage a conversation in a variety of ways. Just to take Demy, some scenes in Lola are handled in full shots like the one highlighting Roland in the café. Other scenes are broken up into tight singles, and still others are treated in two-shots.

All the classical films I’ve mentioned are pluralistic in their technical choices. Today, though, we see more uniformity, or rather conformity.

Cinephile conversation on the internet is currently rippling around a controversy about “slow cinema.” Whatever that rough category covers, it surely includes those festival films that put the camera in one spot per scene and simply observe. I’d argue that many of these minimalist movies are also AWOL when it comes to staging. After watching a long-take, flatly shot film with me, a Hong Kong filmmaker friend remarked, “This sort of thing is just too easy.” One difference between a solid “slow film” and an empty one, I suspect, lies in the extent to which the filmmakers explore the resources of staging. How do we know? We have to analyze the films. (More on this matter here.) Absent that analysis, critics’ appeals to realism or meditative restfulness or “time flowing through the shot” risk becoming alibis for inert moviemaking.

Many young directors want to be innovative. They want to shake things up. This is a good impulse. The way things are going, the ambitious way forward is obvious: Go backward. Avoid stand-and-deliver. Avoid walk-and-talk. Get your actors on their feet and move them around the setting. Invent bits of business that let them crisscross the frame, laterally and in depth. Dynamize all areas of the shot. In the process you may discover new dimensions of creativity.

The Cross is only one tactic, but I think it’s useful as a way to sensitize ourselves to staging. The best way to understand staging is to watch, really watch, a lot of classic cinema from Hollywood and elsewhere. When you’re ready for the hard stuff, Mizoguchi is waiting.

I expect disagreements with my criticisms of contemporary film technique, so I hope skeptics will consider my more extensive arguments in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I haven’t found references to what I call the Cross in manuals of direction. The closest technique, and the one that called my attention to the possibilities of the technique, is what Mike Crisp in his valuable book The Practical Director (first ed., 1993) calls the “rise and cross.” This refers to actors getting up from sit-down conversations in one spot and moving to another sit-down area, while switching position in the frame. I’ve expanded the idea to cover a broader variety of situations.

As far as I can tell, my term doesn’t have much in common with the stage direction “Cross,” which you’ll find in play scripts. Janie Jones provides definitions here. While staging in film is in many respects different from that in theatre, I think that moviemakers can find intriguing practical ideas in Terry John Converse, Directing for the Stage.

Alicia Van Couvering’s interview with the Duplass brothers, “Don’t you want me?”, is published in Filmmaker 18, 3 (Spring 2010; not yet available online); my quotation is from p. 43. In his essay Slow Cinema Backlash, Vadim Rizov argues that lesser attempts at “slow cinema” have led to a somewhat predictable style.

Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979).

DER GOLEM: Revisiting a classic

Kristin here:

In 2009, Il Giornate del Cinema Muto, the silent-film festival held each year in Pordenone, Italy, launched a new series. “Il canone rivisitato/The Canon Revisited” addressed the fact that many rare and often obscure silent films are made available through restoration each year, and yet many young enthusiasts who have started attending the festival have seldom had the chance to see the classics on the big screen with musical accompaniment. The opening group of films proved highly successful, and “Il canone rivisitato 2” will be presented this year, when Il Giornate will run October 2 to 9.

Part of the point of the series is to have historians re-evaluate these classics and examine how well they live up to their status as part of the film canon. Last year I contributed a program note on Paul Wegener and Karl Boese’s 1920 German Expressionist film Der Golem. This year I’ve written about Danish director Benjamin Christensen’s 1916 thriller Hævnens Nat (Night of Revenge, released in the U.S. in 1917 as Blind Justice), which will be shown this year, and rightly so.

When I went back and reread my Golem notes to remind myself what sort of coverage is needed, I decided that the text I wrote then might be of wider interest to those who weren’t at the festival last year. Thanks to Paolo Cherchi Usai, one of the festival’s founders and organizers, for permission to revise my brief essay as a blog entry. I’ve changed it minimally and taken the opportunity to add illustrations. Here’s what I said at the time:

Der Golem is a classic film—doubly so.

First, it has long nestled comfortably within the list of titles that make up the German Expressionist movement of the 1920s. Teachers of survey history courses are more likely to show Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (which premiered in early 1920) but a serious enthusiast will make it a point to see Der Golem (which appeared later the same year) as well.

From the start, reviewers recognized Der Golem as Expressionist. In 1921 the New York Times’ critic wrote, “Resembling somewhat the curious constructions of THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, the settings may be called expressionistic, but to the common man they are best described as expressive, for it is their eloquence that characterizes them” (George Pratt’s Spellbound in Darkness, p. 362). In 1930, Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, the most ambitious world history of cinema in English to date, appeared. Highly influential in establishing the canon of classics, Rotha adored Weimar cinema, including Der Golem.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art obtained a large number of notable European films. The core collection of the young archive contained such prestigious titles as Caligari, Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis, and Der Golem. These films soon became part of the museum’s 35mm and 16mm circulating programs. With MOMA’s sanction as historically important classics, they remained the most widely accessible older films available to researchers and students alike for many decades.

There is, however, a second, largely separate audience: monster-movie fans. Starting in the 1950s, German Expressionist films were promoted as horror fare by Forrest J. Ackerman in his magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland. In 1967 Carlos Clarens included Der Golem in his An Illustrated History of the Horror Film. Really dedicated horror devotees pride themselves on their expertise across a wide variety of films, including foreign and silent ones. Der Golem became a certified horror classic.

In the 1950s and 1960s, companies offering public-domain 8mm and 16mm copies for sale enabled both film-studies departments and movie buffs to start their own film libraries. Ultimately home video made previously rare silent classics easily obtainable—including a restored Golem from the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau-Stiftung, with new tinting and a musical score, on DVD. Such a presentation reconfirms the film’s status as a classic.

But what sort of classic is it? An undying masterpiece that one must see immediately? A film one should definitely watch someday if the chance arises? On the occasion of Der Golem being presented on the big screen with live musical accompaniment, we have a chance to specify what distinguishes it from its fellow exemplars of Expressionism.

I suspect that horror-film fans won’t feel that a reevaluation is necessary. Der Golem is a forerunner of Frankenstein and hence an important early contribution to the genre. It’s a striking film to look at and obscure enough to impress one’s friends during a late-night program in the home theater.

But for film historians returning to Der Golem in the early twenty-first century, after nearly ninety years of taking it for granted, what is there to say?

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

It’s a subject susceptible to endless debate. To avoid that, it’s helpful to accept historian Jean Mitry’s simple, useful distinction between graphic expressionism, with flat, jagged sets, and plastic expressionism, with a more volumetric, architectural stylization. If Caligari introduced us to graphic Expressionism in 1920, Der Golem did the same for plastic Expressionism later that year.

For me, seeing Der Golem again doesn’t much affect its status as an historically important component of the German Expressionist movement. It’s not the most likeable or entertaining of the group. Caligari has more suspense and daring and black humor. Die Nibelungen has a stately blend of ornamental richness with a modernist austerity of overall composition, as well as a narrative that sinks gradually into nihilism in a peculiarly Weimarian way.

Moreover, Der Golem’s narrative has its problems. None of the characters is particularly sympathetic. Petty deceits and jealousies ultimately are what allow the Golem to run amok. The narrative momentum built up in the first half of  the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

But putting aside Der Golem’s minor weaknesses, it has marvelous moments that summon up what cinematic Expressionism could be: the opening shot, which instantly signals the film’s style (below); the black, jagged hinges that meander crazily across the door of the room where Löw sculpts the Golem; the juxtaposition of the Golem with a Christian statue as he stomps across the crooked little bridge returning from the palace (at top).

Hans Poelzig was perhaps the greatest architect to design Expressionist film sets. He designed only three films, and Der  Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Speaking of performances: A lot of the actors in German Expressionist films were movie or stage stars who didn’t specialize in Expressionism. There were, however, occasional roles that preserve the techniques the great actors of the Expressionist theater. There’s Fritz Kortner in Hintertreppe and Schatten. There’s Ernst Deutsch, who acted in only two Expressionist films, as the protagonist in the stylistically radical Von morgens bis Mitternacht (out this month on DVD) and as the rabbi’s assistant in Der Golem.

Just watching his eyes and brows during his scenes in this film conveys something of the experimental edge that Expressionism had when it was fresh—before its films had become canonized classics.

Watching a movie, page by page

The Ghost Writer (above); The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (below).

DB here:

Aristotle said, quite reasonably, that every plot has a beginning, a middle, and an end. But that doesn’t mean that every plot consists of three acts. Aristotle doesn’t mention act divisions in the Poetics for the good reason that classical Greek plays didn’t have them. The three-act play is just one convention that emerged in the history of storytelling.

As early as 20 BCE Horace was suggesting, “Let no play be either shorter or longer than five acts.” Influenced by this edict, Renaissance editors and playwrights adhered to five acts for many years. We have, of course, plays in two acts (Alan Ayckbourn’s Norman Conquest cycle) and four acts (Pygmalion, The Admirable Crichton, many of Chekhov’s). TV dramas are routinely divided into a teaser and four acts, broken up by commercials. All of those plots have beginnings, middles, and ends, so it’s silly to think that only the three-act structure can fulfill Aristotle’s dictum.

As early as the seventeenth century, the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega recommended three acts as best. In Europe, the format came into its own during the nineteenth century, evidently dislodging the five-act one. One reason may have been that three parts are architecturally simple, sturdy, and easily visualized. Around 1820 Hegel remarked: “Three such acts for every kind of drama is the number that will adapt itself most readily to intelligible theory.” What such a theory might look like was sketched by Lope, who anticipates modern advice manuals.

In the first act set forth the case. In the second weave together the events, in such wise that until the middle of the third act one may hardly guess the outcome. Always trick expectancy.

So proponents of the three-act screenplay formula should revise their pedigree. They’re actually pushing the Lope-Hegel tradition—which admittedly sounds less impressive than dropping the name of Aristotle.

Three acts, more or less

Despite the historical misunderstandings, there’s some reason to think that Hollywood screenwriters, and now filmmakers across the world, have followed a rough three-“act” scheme. Where they got this idea and when it started is still hard to say, but it’s been at the core of nearly every screenplay manual since the 1980s. Kristin and I have looked at this format from an academic perspective, and our views are outlined briefly on this site here and here and here. For more detailed arguments you can read her Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

In those places we’ve argued that Hollywood feature films tend to fall into chunks of 20-30 minutes. As a result a movie may display three parts, or four, or more (if the film is very long) or even two (if it’s unusually short). When the film has four parts, it tends to split the long second act that the manuals recommend into two.

A four-parter usually goes like this. A Setup lays down the circumstances and establishes the primary characters’ goals. The Complicating Action is a sort of counter-setup, modifying the original goals or creating new ones. At about the midpoint, there emerges a Development section characterized by delays, subplots, and backstory. There follows the Climax, which resolves the action by decisively achieving or failing to achieve the protagonist’s goals. The film typically ends with a brief Epilogue that establishes a settled state, happy or unhappy. Each of these sections is demarcated by a turning point—a moment of crisis, usually involving an unforeseen twist or a major decision by the protagonist.

Two recent films, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, offer good examples of how the four-part template governs plot structure. I won’t walk through each one here, but both seem to me to adhere quite closely to this model. Today I’m more curious about the original novels. We know that books are routinely reshaped for movie treatment. Is there a sense in which the plot structure of the originals fits the film formula?

Fiction as film

I ask because some fiction writers have come to believe in the enduring power of the three-act structure for all narratives. In The Weekend Novelist (1994), Robert J. Ray recommends that aspiring writers use it (although he breaks Act II into two parts around the midpoint). He finds the pattern enacted in his book’s primary model, the novel The Accidental Tourist. “We’re working with the structure of [Anne] Tyler’s Tourist because it is classical, three acts” (142). This, Ray claims, follows “Aristotle’s dictum of beginning, middle, and end” (141). Ray makes a comparable suggestion in The Weekend Novelist Writes a Mystery (1998), naming the three parts Setup, Complication, and Resolution; a midpoint again splits “Act II.1” from “Act II.2.”

Ray’s are the earliest instances I’ve found of explicitly applying screenwriting structure to prose fiction. Later ones would include Stephen Greenleaf’s 1996 article “A Mystery in Three Acts” and James Scott Bell’s 2004 book Plot and Structure. Bell argues somewhat grimly that life itself has three acts: childhood, “the middle where we spend most of our time,” and “a last act that wraps everything up” (23). Ridley Pearson, in the 2007 article “Getting Your Act(s) Together,” tells us that the “three-act structure, handed down to us from the ancient Greeks [!], is one that’s proven successful for thousands of years” (67). “Name a film or book you think rises above others, and chances are, if you go back and study it, the story line will fit into this form” (85). Brenda Janowitz recommends plotting a Harlequin romance as if it were a movie like Mean Girls.

But screenwriting adepts will notice one thing that these advisors neglect: the lengths of the parts. The book that popularized the three-act structure in film circles was Syd Field’s Screenplay of 1979. Not only did he lay out the template, but he indicated running times for each section. Act 1 should last about thirty minutes, Act 2 sixty minutes, and act three about thirty. Assuming that one minute of screen time equals a page of the screenplay, that means that a two-hour movie should run about 120 pages. Field’s metric proved very influential, with script readers, producers, and writers all striving to find plot points at twenty-five minutes and ninety minutes.

To be strictly parallel, then, a “three-act novel” should be divisible into parts having a page ratio of 1:2:1. The only manual I know that is willing to bite this bullet is Writing Fiction for Dummies (2009). (The title has a catchy ambiguity, no?) According to the authors, Act 1 takes up the first quarter of the book, Act 2 the middle half, and Act 3 the last quarter (p. 147).

In the film versions of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, the segments and timings fit the four-part model fairly neatly. (Try it yourself, in the theatre or when the films come out on DVD.) But what happens when we look at published books? Will we find what Ray found in The Accidental Tourist—conformity to the formula? Are practicing novelists using the template? Are the timings, or rather the page-counts, of the books congruent with the film model?

First I’ll consider Robert Harris’ novel The Ghost, the source of The Ghost Writer. The next section looks at Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. If you want to avoid spoilers, skim and skip accordingly.

Ghost writers in the sky

The opening chapters of The Ghost introduce the unnamed narrator, a professional writer who is on the verge of breaking up with his girlfriend. Hired to ghost-write ex-Prime Minister Adam Lang’s memoirs, he is replacing Lang’s aide McAra, who drowned under mysterious circumstances. The Ghost takes the job just as news media are floating the charge that Lang helped the US ship British citizens to black sites to be tortured. The Ghost travels to join Lang, who is staying in America with his secretary Amelia and his wife Ruth. At his hotel, the Ghost encounters a surly British man who asks him pointed questions about Lang. This setup lays out the affair between Amelia and Lang, Ruth’s sexual jealousy, and the mounting political pressure on Lang, along with the sinister Brit in the bar. The section ends on p. 83 of the 335-page Gallery paperback edition, almost exactly one-quarter of the book.

The complicating action arrives when the Ghost’s first sit-down with Lang the next day is interrupted by the announcement that Rycart, former Foreign Secretary in Lang’s government, has asked the Hague to investigate the PM for war crimes. Under pressure from protestors, Lang decides to go to Washington for appearances’ sake. In the meantime, the Ghost discovers a set of clues McAra has left behind: photos of Adam in his Cambridge days, records and news reports of his party activities, and a mysterious phone number that turns out to be Rycart’s. All this creates a counter-setup. There is something foul afoot.

The Ghost ruminates constantly on McAra, a writer who has become something of a ghost haunting his successor. Soon the digital file of McAra’s draft of the memoir vanishes from the Ghost’s email. Most fundamentally, he discovers that in the first interview Lang has lied to him about how he got into politics.

That was when I realized I had a fundamental problem with our former prime minister. He was not a psychologically credible character. In the flesh, or on the screen, playing the part of a statesman, he seemed to have a strong personality. But somehow, when one sat down to think about him, he vanished. This made it impossible for me to do my job. . . . I simply couldn’t make him up (162).

At this point the protagonist decides on a new goal: to investigate on his own. This transforms his official assignment, and it happens on p. 163—quite close to the midpont of the book.

The development section is filled out with the usual delays, false leads, counter-maneuvers, and backstory. The Ghost’s investigation brings him to an interrogation of an old man who suspects foul play in McAra’s death, a sexual encounter with Ruth, a meeting with a professor with apparent CIA connections, and a suspicious vehicle in the vicinity. The turning point comes with another decision. “The more I considered it, the more obvious it seemed that there was only one course of action open to me.” The Ghost phones Rycart and flies to New York to meet him. This passage concludes on p. 256.

The climax sporadically unravels the clues McAra has left behind. In their meeting Rycart and the Ghost conclude that Lang was recruited by Professor Emmett during their Cambridge days and became a US puppet. Rycart has taped his exchange with the Ghost and uses that to force him to return to confront Lang. On Lang’s private plane, the Ghost accuses him but Lang’s denials are disconcertingly sincere. On disembarking, he is killed by a suicide bomber—the crusty Brit who blames Lang for the death of his son in Iraq. Although he’s haunted by dreams of a drowning McAra (“You go on without me. . .”), the Ghost plows ahead with Lang’s now-posthumous memoirs. All seems to have been settled until the book launch, when the Ghost discovers another way to interpret the evidence. He returns home to check McAra’s manuscript, where he finds a coded message identifying Ruth as the one recruited by Emmett; she was the mole. This revelation that the first solution was wrong, a detective-story device going back at least to Trent’s Last Case of 1913, arrives on p. 330.

An epilogue of only five pages reports that the Ghost is on the run. If anything happens to him, his former girlfriend will publish his story. “Am I supposed to be pleased that you are reading this, or not? Pleased, of course, to speak at last in my own voice. Disappointed, obviously, that it probably means I’m dead.”

The result conforms fairly strongly to the triple ratio: Act 1 runs 83 pages, Act 2 runs 173 pages, Act 3 runs 79 pages. Using the four-part template, we get 83/80/93/74, with a five-page epilogue.

Not perfect symmetry, but that’s hardly to be expected. Novelists stretch or compress as needed, and they can make scene boundaries a little fuzzier than what we find in films. For such reasons, other analysts might shift my breakpoints a few pages fore or aft. In addition, many films make the climax section somewhat shorter than the others, so we won’t always get perfect symmetry in novels either. Still, The Ghost offers a reasonably close approximation to the sort of plot template that we find in many commercial movies.

Double duty

Stieg Larsson’s The Girl Who Played with Fire provides a somewhat different sort of plot. We have two protagonists and three lines of action—two mysteries plus a search for revenge—or rather four, if you count the prospect of a romance between the protagonists. The book is also much longer than The Ghost, running 644 pages in the Vintage paperback edition I have. You might therefore expect more large-scale parts. But . . . .

The setup lays out the three major lines of action. Journalist Mikael Blomkvist, misled by an informant, publishes a false news story about the dealings of the businessman Wennerström. After Blomkvist is sentenced to prison, the second line of action kicks in: Henrik Vanger asks him to find what happened to his brother’s granddaughter Harriet. Meanwhile the neopunk hacker Lisbeth Salander is introduced as a security analyst researching Blomkvist for Vanger. By p. 138 Blomkvist has decided to accept the Vanger assignment. This section is not far from being a quarter of the text, and it corresponds to a major break, the end of Part 1 (“Incentive”).

The next large-scale section complicates things on two levels. It plunges Blomkvist into the details of Vanger family history and Harriet’s disappearance, and it brings Lisbeth Salander’s life to a point of crisis. We learn her past as an orphan and a denizen of the streets and hacker subculture, living under the thumb of her guardian Bjurman. This section is rather long, about 150 pages, because it has to establish Lisbeth as a dual protagonist and show her stratagems for escaping Bjurman’s sexual exploitation. Blomkvist must also serve his short prison time in this segment.

I’d argue that the plot’s midpoint occurs on page 323, halfway through the book. Chapter 16 begins:

After six months of fruitless cogitation, the case of Harriet Vanger cracked open. In the first week of June, Blomkvist uncovered three totally new pieces of the puzzle. Two of them he found himself. The third he had help with.

These revelations propel Blomkvist into a lengthy investigation of serial murders, which requires him to hire Lisbeth as his research assistant. While the two follow up clues, they start an affair.

On p. 477, it seems to me, the climax begins. The investigation has cast suspicion on Martin Vanger, Harriet’s brother. Blomkvist hears Martin returning home. “That somehow brought matters to a head.” Blomkvist goes out to confront him. Two pages later Martin shows him into the basement. “Blomkvist had opened the door to hell.” Now scenes of Lisbeth’s research and return to the village alternate with scenes showing Blomkvist at the mercy of Martin in his torture chamber.

Because the central plot involves two mysteries, the climax is extended. I’d argue that the two mysteries, the serial killings and Harriet’s disappearance, are solved by page 560 or so. But there remains the matter of Blomkvist’s revenge on the plutocrat Wennerström, who had tricked him into printing a phony story.

That dangling plotline is tied up in the next chunk (pp. 562-628), which forms in effect a second climax. Thanks to Lisbeth’s research, Blomkvist and his partners prepare to publish an expose of Wennerström’s crimes in Millennium. The evening that Blomkvist goes on TV, public opinion shifts decisively in his favor, and as the translation has it, “Blomkvist’s appearance marked a turning point.” He has won, and so has Lisbeth, who has drained money from Wennerström’s offshore accounts.

The sixteen-page epilogue tells us that Wennerström, facing disgrace and jail, kills himself. By now the two protagonists have struggled up from below. Blomkvist redeems his reputation and becomes the toast of journalism. Lisbeth, poor and victimized by men, becomes independent and enjoys her stolen fortune. There remains only the question: Will the two unite romantically? A final scene replies with a very old plot devices that’s one of Larsson’s favorites: a chance encounter that triggers a misunderstanding.

So I’m proposing a 138-page setup, a 150-page Complicating Action, and a 154-page Development. If you consider my two climaxes a single stretch, you have a 149-page climax section. That makes the big parts roughly equal, with a tailpiece of 16 pages. Even though The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has nearly twice the page-count of The Ghost and crams in two protagonists and several plotlines, it displays the symmetry we find in the more compact book. The chief difference is between a comparatively short climax and a protracted one—the same difference we often find in classically constructed films. For these novels, and I suspect many others, the three-act/ four-part template provides a solid architecture for the plot.

Miracles, critical fantasies, or just tradition?

I won’t try to align the parts articulated in the novels with those we find in the finished films. The congruences are fairly close, once you grant that both films compress scenes and lop off characters and plotlines that are developed in the novels. Instead, I want to close by asking some questions.

Would novelists admit to consciously adopting this structure? If they don’t, or if we think it’s implausible that they would, we’re confronted with the charge that we’re simply projecting this structure onto the books. Are we and the writers of manuals shoehorning these plots into the three-act/ four-part format? Could we come up with equally persuasive patterns if we set out looking for seven or seventeen or seventy “acts”?

To take the last question first: Probably not. I think my analyses carve the films and books at the joints, more or less. One reason I like Kristin’s analytical method is that it hinges on characters’ goals and their pivotal decisions or reactions. These tend to be emphatic, well-articulated moments in the plot; a lot, as we say, depends on them.

True, there is some room to argue about which ones might be most far-reaching. You can propose alternatives, and I can change my mind. But the rival candidates for goals and decisions and major turning points aren’t likely to be radically different. We agree on most structural conventions, and our differences tend to be fine-grained, not gross.

Still, this sort of analysis arouses skepticism, and rightly so. How can writers and filmmakers achieve this neat structure without conscious planning? Can you follow the rules without doing so deliberately? Kristin offers an explanation that emphasizes the intuitive search for proportion in the creative process. She invokes Vivaldi concerti, medieval altarpieces, daily comic strips, and even the Great Pyramid at Giza as examples of balance among parts in both high and popular arts.

The evident use of proportions in many narrative films provides one more indication of the enduring classicism of the mainstream Hollywood system. Presumably what practitioners have intuitively assumed to be the optimum range of lengths for each part was discovered early on. It has been passed down the generations of filmmakers as a result of the simple fact that most practitioners gain their basic skills by watching a great number of movies (Storytelling in the New Hollywood, 44).

I think that there’s still a lot to learn about these templates. How are they disseminated among filmmakers? Why are we unaware of these parts while watching the film? They don’t stand out like chapter divisions in a novel. Or do we sense them subliminally? And how widespread are they? Do we find them in classic studio cinema of the 1920s through the 1950s? (Kristin thinks so, as do most writers of screenplay manuals.) Do we find them in films from other cultures and periods? If so, perhaps filmmakers elsewhere have found them to be reliable ways to engage viewers. Possibly these models were spread with the circulation of American movies.

I’ll provide my own epilogue by noting that the novelists’ borrowing of screenplay structures is a recent instance of a long-term process: the “cinefication” of other media. Today we call successful novels “tentpoles” or “blockbusters” or “locomotives,” and we say they’re “released” rather than “published.” What used to be called a series of novels is now likely to be called a franchise. It may be that many novelists have absorbed the lessons of screenplay manuals. If you wanted your book to be bought by a producer, why not make it like a film beforehand?

More abstractly, we have artistic transfer and technical influence. For a long time critics have argued that literary modernists like Faulkner and Hemingway, along with more popular genre writers, have tried for “cinematic” styles and have sought to imitate the “camera eye” in their narration. Today perhaps we see a structural influence as well: rules of film plotting mapped onto prose fiction. The next page-turner you read may have been engineered to flow across your eyes at the brisk pace of a Hollywood movie.

Several of my references to classical theorizing about act divisions are taken from Oscar Lee Brownstein and Darlene M. Daubert, eds., Analytical Sourcebook of Concepts in Dramatic Theory (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1981). For more on classical Greek drama’s structure, go here. You can read a brief summary of the history of act divisions in western drama here.

On the three-act screenplay structure as applied to independent films, see J. J. Murphy’s You and Me and Memento and Fargo. See also J. J.’s independent cinema blog.

Stephen Greenleaf’s “A Mystery in Three Acts” appeared in The Writer 109, 4 (April 1996). Ridley Pearson’s article “Getting Your Act(s) Together” appeared in Writer’s Digest 87, 2 (April 2007), 67-69, 85. For another application of three-act structure to the novel, go here. The author claims that “movies rather than books are easier to analyze in that the main plot points are visual.”

On The Ghost Writer, a useful interview with Robert Harris is here. An entry on Creative Loafing points out ambiguities and vague spots in the movie’s plot. A January 2008 draft of the script, which incorporates voice-over narration, is available here.

The most influential account of how American novelists adapted cinematic techniques is Claude-Edmonde Magny’s Age of the American Novel: The Film Aesthetic of Fiction between the Two Wars. See also Keith Cohen’s Film and Fiction: The Dynamics of Exchange.

The Ghost Writer.

A hundred years, plus a few thousand more, in a day

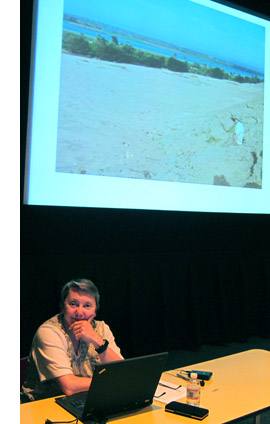

Charlie Keil, Yuri Tsivian, Henry Jenkins, Kristin Thompson, and Janet Staiger. Photo by Joel Ninmann.

Last Saturday we held the symposium “Movies, Media, and Methods” in honor of Kristin’s arrival at age sixty. Four distinguished scholars, all professors from major universities, presented top-flight talks. As a bonus, Kristin gave The Film People a glimpse into her Egyptological work. I report on this very full day in the hope of giving a sense of how stimulating we found it.

Thanhouser was an American film company that flourished between 1909 and 1917. It has been overshadowed by Biograph because that firm put out more films and, not incidentally, employed D. W. Griffith. But Ned Thanhouser has been diligently gathering his family company’s output from archives around the world and releasing it in informative DVD editions. The most famous Thanhouser production is probably Cry of the Children (1912), a powerful attack on child labor. You could also try the thriller The Woman in White (1917), adapted from Wilkie Collins’ masterful novel. A study in sadism, and more subtle than The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Charlie Keil, an expert in 1910s US film from the University of Toronto, examined Thanhouser’s films with two questions in mind. Did the studio have a “distinctive personality” in its products? And does its output reflect the development of film style across the crucial transitional years of the early 1910s? Borrowing a method that Kristin had applied to Vitagraph films in an essay, Charlie took one film from 1911, one from 1912, and one from 1913. Charlie wasn’t ready to conclude that these specimens displayed a unique studio style, but it was clear that across just three years, big changes in storytelling were taking place.

The plot of Get Rich Quick (1911) involves a man who joins a business that is scamming innocent investors. The film uses only five locales and plays scenes in long takes. The Little Girl Next Door (1912) has a more complex plot, with two distinct lines of action that converge on a child’s drowning. It uses many more locales and an ellipsis of a year to trace the changes in a family’s fortunes. It also incorporates cut-in close views and point-of-view editing. The Elusive Diamond (1913) is less psychology-driven than The Little Girl Next Door, but its intrigue relies almost completely on dialogue titles and it includes many close-ups and variation of camera setups.

Three films and three years: A vivid cross-section of the rapid development of what soon became classical visual storytelling. Moving from 18 shots to 53 shots to 74 shots, the films became less dependent on staging and more dependent on editing. At the same time, Charlie didn’t fail to notice how the long takes in Get Rich Quick allow some felicities of performance, particularly the way that the wife’s handling of her apron charts her psychological states. She brushes it aside to show how poor they are, then she uses it as a giant hankie.

Like all good papers, Charlie’s left a lot to be discussed. People asked about how much pre-planning was done at Thanhouser, about the directors and screenwriters on staff, about the division of labor. We were left with a sense that here was another mostly unknown region that would reward further study.

Fernand Léger, Cubist Charlot (1923).

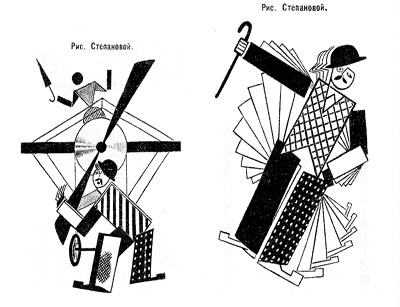

Yuri Tsivian of the University of Chicago carried us into the twenties with an in-depth examination of early Russian reactions to Charlie Chaplin. The paper held many surprises. Chaplin was popular in many countries from 1915 onward, and very soon after he was celebrated by European intellectuals. But Russia lagged behind; there’s no concrete evidence that any Chaplin films were shown there until 1922. Yet the Soviet avant-garde embraced him. How and why?

Instead of looking for a dual relationship—Chaplin directly influencing Russian artists—Yuri postulated a “triangular” relationship, in which Chaplin’s image was mediated through other European sources. For instance, Léger’s numerous images of a fragmented Chaplin led Futurists and Constructivists to declare Charlie “one of us.” They loved the idea of man as a machine executing precisely articulated movement, and what they heard of Chaplin’s pantomime and gags led them to praise him. Chaplin, said Lev Kuleshov, is “our first teacher” because he knows bio-mechanical premises better than anyone. According to the photographer and graphic designer Rodchenko Chaplin instructs viewers in how to walk or put on a hat in the most perfect manner.

So strong was this “virtual” image that artists could read Chaplin into the slapstick comedians they did see. Yuri showed that Varvara Stepanova’s striking rendition of Chaplin as an airplane propeller derived from a film he wasn’t in!

Perhaps she didn’t care: Nikolai Foregger suggested that Chaplin himself was unimportant, that the crucial fact was that he created a whole school of comedians within what Yuri called “a collaborative research community”—that is, Hollywood!

Yuri’s paper, in homage to the Russian Formalists, invoked the “law of fortuity” in art. This refers to the possibility that artistic borrowings, blendings, and crossovers are not determined by any broader social processes, as the Marxists were arguing, but are merely contingent. “Life interferes with art from below.” Accidents and unforeseen intersections, such as the Chaplin craze meeting the Constructivist movement, allow artists to seize on whatever is around them for new material. Yuri’s reference was to Kristin’s revival of Formalist methods in her “neoformalist” studies of Eisenstein, Tati, and other filmmakers.

Janet Staiger of the University of Texas at Austin collaborated with us on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and she has for several years been the leading scholar of reception studies in film and television. In looking at the Indiana Jones series, her paper nodded to Kristin’s work on the Lord of the Rings franchise and her study of fans’ responses to the films.

“Nuking the fridge,” Janet explained, has become fan jargon for an outrageous plot twist. The phrase comes from a notorious moment in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), in which Professor Jones escapes an atomic blast by diving into a lead-lined refrigerator. The moment becomes a crux for clashing fan judgments: This is totally unrealistic vs. Realism doesn’t matter. Janet went on to show how these and other fan responses, entwined in IMDB commentary threads, utilized several different interpretive frames.

One was authorship. Like academics and journalists, fan are auteurists. They assign the director responsibility for major aspects of the film. But this doesn’t mean that they agree in how to use this frame. In the case of Crystal Skull, a certain Kid Mogul asked if Spielberg’s willingness to reinvigorate the franchise was purely mercenary: “Is it just about the money?” Others took a more career-survey approach, noting that after prestige pictures like Schindler’s List Spielberg recalibrated his popcorn movies, particularly by handling violence more gingerly.

Another frame was story-based “lit talk.” Fans disparaging the film found it clumsily plotted and lacking in character development. Several were quite sensitive to narrative coherence, one-off gags (such as nuking the fridge), and pacing. Those defending the film appealed to the emotional burst of the final chase scenes.

Janet’s third frame of reference was what she called “formula dissonance.” She sought to capture what seeing the film would be like for those who knew Indy’s story only through the TV series or video versions of the earlier installments in the franchise. She suggested that the formula was by 2008 quite abstracted and idealized for many fans. Their sense of the franchise was thus tested by the extraterrestrial twist that resolved the Crystal Skull plot. Does it reframe the whole series in a cosmic context, or is it a violation of the premises of the Indy universe?

Janet’s survey of these types of responses made me notice that the assumptions of academic film studies and of journalistic criticism overlap with fan conversation. Fans who liked the film tried to make everything fit by appeal to organic unity, technical proficiency, emotional intensity, and other familiar criteria. It made me suspect yet another reason why “amateur” and “professional” film criticism seem to be merging: Perhaps their conceptual frames of reference aren’t so far apart. But their tastes and their degrees of commitment surely are.

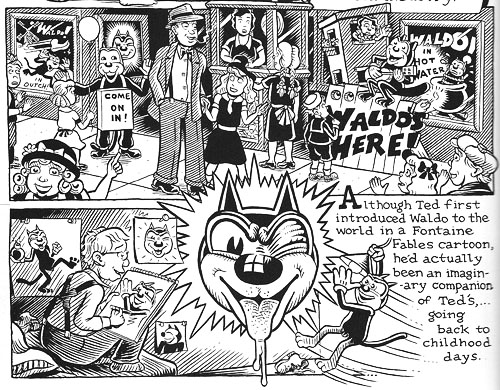

You might have expected Henry Jenkins of the Annenberg School at the University of Southern California to talk about fans too. After all, he practically invented the modern study of media fandom with his book Textual Poachers, and his work influenced Kristin’s study of fan promotion of The Lord of the Rings. Instead he turned to a survey of an artist’s oeuvre. He showed how Kim Deitch’s vast output of stories appropriate imagery from nineteenth and twentieth century mass media and present highly personal versions of the history of popular culture.

In a way, though, Henry’s talk involved fandom because Deitch is himself a prototypical fanman. He’s an obsessive collector, likely to turn his search for a rare toy or drawing into a Byzantine odyssey on the page. Fascinated by Hollywood scandal, he has constructed a phantasmagoric history of mass media through fictional characters (e.g., fake movie stars) who confront real people (e.g., Fatty Arbuckle). He’s particularly concerned about what he takes to be the warping of animated film by the influences of the mass market, epitomized by the Disney empire. The emblematic moment in Boulevard of Broken Dreams comes when Deitch’s Winsor McKay stand-in addresses torpid animators at a tribute dinner and denounces them for selling out.

Deitch’s most famous character is Waldo the cat, and Henry traced the powerful connotations of this emblematic figure. Waldo recalls Felix, the most heavily merchandised comics figure before Mickey, as well as the black cat as a figure of deception, witchcraft, and even African-American minstrelsy. Through Waldo, Deitch could hop across the history of film and comics, from McKay to Mighty Mouse and 1940s abstract films. In Alias the Cat!, Deitch finds in the 1910s everything that we associate with media today: serial narrative, stories shifting across different media platforms, an uncertain line between publicity and self-expression, and a mixing of news and sensational fiction.

Henry situated Deitch in a broader trend of comic artists trying to find a new history of their medium, one that dislodges superheroes from a central role. Deitch’s themes of old-fashioned craftsmanship, lovably antiquated technology, adult dread and degeneracy lurking behind children’s stories, and the commodity demands of comic art link him to contemporaries like Chris Ware and Art Spigelman.

Henry’s talk spurred a lot of discussion, including the question of whether we can treat an artist as offering a history that is comparable to academic research. Can Deitch’s hallucinatory vision of American media be a plausible basis for understanding what really happened? On the whole we don’t expect an artist to offer rigorous arguments. An artwork appropriates history for its own end. (Not all the Greek philosophers actually gathered together in the way Raphael depicts them in the School of Athens painting.) How cogent you find Deitch’s critique probably also depends on whether you share his disdain for Disney. His floppy-limbed denizens fuse headcomix grotesquerie with the 1930s animation that most prestige studios abandoned. As in Sally Cruikshank’s sprightly cartoon Quasi at the Quackadero, Deitch’s rubbery frames revive a style in which everything seems to throb and shimmy.

Kristin’s talk, “How I Spend My Winter Vacations: The Amarna Statuary Project and Techniques of Visual Analysis,” had two parts. In the second part, she reviewed her recent work in assembling statues out of tiny bits that had been dumped by archaeologists decades ago. You can read some of this story here. The side of her work most intriguing to students of film, I think, involves her attraction to Egyptian art in the first place.

Egyptian art is often thought of as unrealistic, but during his reign in the fourteenth century BCE the pharaoh Akhenaten introduced a peculiar sort of stylization into it. When he instituted a monotheistic religion centered on the sun god Ra (embodied in the Aten), he also demanded a new pictorial style. Thus the Aten is depicted as a disc shedding rays, a symbol of life and dominion. In addition, the royal family displays biggish hips and thighs, which fit the fecundity theme. More strikingly to our eye, Akhenaten’s family were represented as somewhat distorted, with long and narrow faces, hands, and feet. The ruler’s crown is elongated as well. Several aspects of the new style are present in Kristin’s favorite scene, a beautiful relief carving known as the Berlin family stela.

You can see the Aten’s rays ending in little hands holding ankh signs to the royal couple’s noses. But just as important is the human dimension of the scene, and two sorts of action displayed there: swiveled shoulders and pointing hands.

Unlike the flat, frontal portrayal we associate with Egyptian art, the family members are caught in twisting postures that bring one shoulder forward. Kristin explained:

Akhenaten is lifting his daughter, his foreground arm moving backward to hold her legs, the other moving forward to support her body as he kisses her. She reaches with her rear arm to chuck him affectionately under the chin, while her other arm moves backward in a pointing gesture. On the opposite site, Nefertiti’s foreground arm is held bent and backward to steady the youngest daughter of the three present, who is standing on her thigh and reaching up rather precariously to grab a golden decoration hanging from her mother’s crown. Nefertiti’s rear hand goes forward to steady the second daughter, who is also pointing, this time with her rear arm as she twists to look at her mother. These kinds of gestures can be found again and again in such scenes.

The twisting movement wasn’t unknown among images of workers and private individuals; Amarna artists, presumably encouraged by Akhenaten, applied the device to portraying the royal family.

Just as significant are the pointing gestures we find in the stela. Some scholars have interpreted them as protective gestures, which are found in other images. But Kristin points out:

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

After pondering this scene quite a lot, it occurred to me that it looked like a really early film, a short scene, perhaps 30 seconds long, that we were to interpret as a tiny narrative. The pointing gestures seemed comparable to pantomime, where one has to interpret movements in the absence of intertitles.

Given that so much Amarna art is about displaying the royal couple as having created life by giving birth to their daughters and as sustaining that life, it seems to me that this stela is full of indications of nurturing. The columns and roof indicate that the parents have their kids in a little shelter to keep them out of the hot sun. The rows of pots behind Akhenaten’s stool are no doubt filled with cool drinks for them. Nefertiti carefully holds onto the two children on her lap while Akhenaten kisses the eldest. My interpretation is that the eldest is saying something like, why don’t you kiss sister, too?” and the one opposite is pointing out the kiss to her mother and saying something like, “Look, daddy’s kissing sister; I want a kiss too.”

This may not sound like the sort of thing kids would say, but the circulation of affectionate gestures among the family members in these casual scenes is nearly universal. The chucking under the chin gesture used by Meretaten here shows up again and again, as do embraces and kisses.

Despite all the stylization, then, Kristin concludes that the stela depicts a scene of intimate affection, complete with a child toying with a mother’s ornament. This homely realism chimes with other realistic tendencies in Amarna art, such as the differentiation of right and left feet and the presentation of plants and animals in non-stereotyped ways. In sum, Kristin’s ability to look closely at film style helped her make discoveries about visual narrative in a completely different domain.

So our Saturday talks included cinema-related material from 1911 to about 2010, and with Kristin’s lecture we flashed back about 3300 years. Every talk was crisp and lucid. We were spared the juggling of empty abstractions, the free-associative rambling, and the self-congratulatory cleverness that plague the humanities. We got knowledge and opinion presented with enthusiasm, modesty, and good humor.

Kristin and I are grateful to our presenters, as well to all the friends old and new who showed up: Leslie Midkiff Debauche from Stevens Point, Carl Plantinga from Michigan, Peter Rist from Montreal, Brenda Benthien from Cleveland, Virginia Wright Wexman from Chicago, Vicente José Benet from Spain (via Chicago) and many others. In all, a day to remember.

For more information on Kristin’s research see my earlier entry. For other cinematic implications of the Berlin stela of Akhenaten’s family , see Kristin’s blog entry here. Her article, “Frontal Shoulders in Amarna Royal Reliefs: Solutions to an Aesthetic Problem,” is available in The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 27 (1997, published 2000).

All of our speakers are represented on the Web: Henry here, Charlie here, Janet here, and Yuri here (and of course on Cinemetrics). For more on Janet’s study of online critics and the frames they inherit, see her essay, “The Revenge of the Film Education Movement.”

Kim Deitch, Boulevard of Broken Dreams.