Archive for the 'Film history' Category

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Much ado about noir things

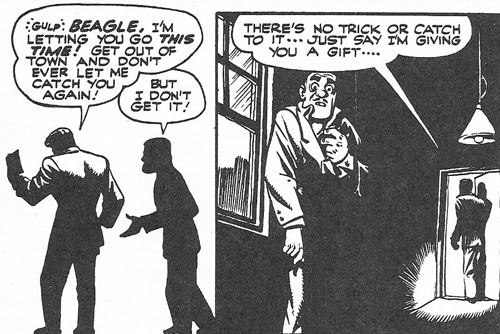

From “The Killer,” Spirit Comics (8 December 1946), by Will Eisner and studio.

DB here:

This is my final effort to cram my latest book down the resisting gullet of the reading public. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling has just come out in paperback and I’ve been using our blog to trace out some relevant ideas that surfaced in recent books and DVD releases. The first entry dealt with some general issues, the second with popular culture’s drive toward variation, the third with craft and auteurism. This one has murder on its mind.

Noir as mystery and mystique

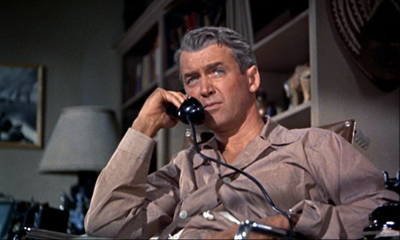

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

Crime looms large in Reinventing Hollywood. But I forsake the usual category of film noir. It didn’t exist as a concept for the filmmakers or audiences of the day. It’s the creation of critics, first overseas and then, much later, here at home. That doesn’t make the category invalid, though. Many art-historical categories (Baroque, Gothic) are later inventions, and those can be illuminating. Still, I think we gain some understanding if we situate our inquiry, for a time at least, at the level of what people seemed to be trying to do at the time.

Put it another way. By focusing on noir as the model of Forties narrative, we miss the ways in which the films we pick out under that rubric participate in wider trends. We miss, for instance, the new importance of mystery in all plotting of the period.

In the 1930s, mystery was mostly confined to detective stories. Think of your prototypical 1930s movie; it’s unlikely to have a mystery at its center. (Okay, maybe we’re curious about the identity of Oz the Great and Powerful.) In the 1940s, though, filmmakers began to scatter mystery devices into other genres. Mystery became a central storytelling strategy for personal dramas (Citizen Kane, 1941; Keeper of the Flame, 1943), romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan, 1945), war films (Five Graves to Cairo, 1943), social comment films (Intruder in the Dust, 1949), and domestic melodrama (Mildred Pierce, 1945; The Locket, 1946; A Letter to Three Wives, 1948). Some of what we call noir is part of this trend.

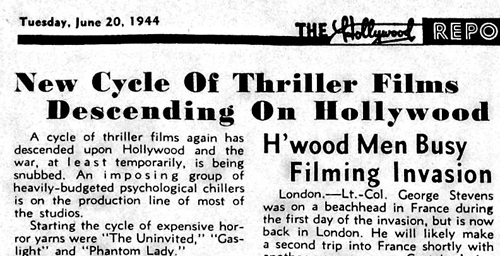

Over the same period, a fairly minor genre got promoted. Psychological thrillers can be traced back to Gothic novels and sensation fiction, but they became a distinct part of crime literature in the 1930s. They became an important genre for cinema in the 1940s, and so Reinventing Hollywood devoted a chapter to films like The Spiral Staircase (1945) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

These aren’t canonical “noir” films, at least if your notion of noir stems from hard-boiled fiction. Some rely on the guilty-party plot exemplified in C. S. Forester’s novel Payment Deferred (1926), Patrick Hamilton’s play Rope (1929), and Anthony Berkeley Cox’s novel Malice Aforethought (1931). Less famous but just as interesting is the “woman-in-peril” thriller.

This was an upmarket version of romantic suspense novels associated in earlier decades with Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), one of the top-selling books of the 1940s, lifted the genre to respectability. Revisiting traces the wide-ranging variations that followed in film, fiction, and theatre. (An early draft of that chapter is elsewhere on this site.) Mystery is central to this subgenre. Who is endangering the protagonist? What are the real motives of the people around her, especially her lover or husband? Are her friends complicit? How will she escape?

The gynocentric thriller remains powerful in popular literature today. We’re currently in a rapid-fire cycle of it, typified by the work of Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn. Some of the books have come to the screen: Gone Girl (2014), The Girl on the Train (2016), and A Simple Favor (2018). The HBO series Big Little Lies (2017-on), turns a fairly satiric domestic-suspense novel into a heavier exploration of spousal abuse. I’ll be writing more about this cycle later (and giving a paper on it this summer), but let me note two recent examples. One takes its Forties sources for granted, the other flaunts them. Both are coming to a screen near you.

In Alex Michaelides’ new novel The Silent Patient Alicia Berenson, an emerging painter, is found guilty of shooting her husband. Because she seems in permanent shock and refuses to speak a word, she’s confined to a mental institution. There the ambitious young psychotherapist Theo Faber tries to ferret out why she remains silent. The narration alternates, Gone Girl fashion, between Theo’s first-person investigation and Alicia’s diary of events leading up to the killing.

It’s a spare tale narrated in a clumsy style that doesn’t distinguish the two voices. And it reminds us that if you become a character in a novel or movie, don’t get into a car. But it does show the persistence of Forties strategies.

There’s the Crazy Lady (recalling Shock of 1946, above, and Possessed of 1947, as well as John Franklin Bardin’s 1948 novel Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There’s the sinister side of the artworld, with a predatory dealers, a demented painter, and portraits that suggest sinister psychic forces. There’s the apparently rational man who becomes obsessed with a woman in a picture (as in Laura, 1944). There’s a mythological parallel to the heroine (here, Alcestis; in The Locket of 1946, Cassandra). There’s the therapeutic motif of a doctor falling in love with a mentally disturbed patient (Spellbound, 1945). And there is, of course, a twist depending on suppressive narration.

The Silent Patient quietly absorbs these Forties conventions, with virtually no mention of the tradition. At the other extreme sits the self-conscious geekery of A. J. Finn’s The Woman in the Window. In an earlier entry on the eyewitness plot I swore I wouldn’t give space to this novel, largely because I resist people swiping titles of movies I admire. But after alert colleague Jeff Smith told me, “It’s as if he read your Forties book,” I figured I could break my rule.

Indeed this eyewitness thriller relies on a great many narrative tricks from the period. We get a Crazy Lady, dreams, hallucinations, an unreliable narrator, the drama of doubt, flashbacks within flashbacks (with the revelatory one coming at the end), and a Gothic climax punctuated by lightning bursts. Also, inevitably, a car crash.

The book’s epigraph comes from Shadow of a Doubt, and the pages that follow are littered with references to 1940s movies. Our homebound heroine lives in thrall to DVDs and TCM, though her impending fate gives a new meaning to “Netflix and chill.”

The Woman in the Window is soaked in contemporary movie-nerd culture. The heroine updates Jeffries’ tech gear in Rear Window by shooting video footage of the suspects across the way. She mentions Kino and Criterion discs, and even refers to “diegetic sound.” (Has she read Film Art: An Introduction?}

Like The Silent Patient, Finn’s book illustrates how much modern thrillers owe to Forties movies. But it also exemplifies how noir has become a kind of brand and a signal of hip tastes. Maybe that’s a reason to back off the label for a while.

Noir in brief

But let’s not back off too far. Any student of 1940s Hollywood can learn a lot from the vast literature on noir. The most recent item to cross my desk is James Naremore’s Film Noir: A Very Short Introduction. (It’s due to be published in April.) As you’d expect, the author of More Than Night will bring a wide-ranging expertise to a compact survey of books, films, and ideas.

I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations:

I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations:

In the previous two decades modernism had influenced melodramatic fiction of all kinds, and writers and artists with serious aspirations now worked at least part time for the movies.

When the trend reached a peak in the early 1940s, it made traditional formulas, especially the crime film, seem more “artful.”. . . And yet there was a tension or contradiction within the Hollywood film noirs of the 1940s. Certain attributes of modernism—its links to high culture, its formal and moral complexity, its frankness about sex, its criticism of American modernity—were a potential threat to the entertainment industry and were never fully absorbed into the mainstream.

Naremore goes on to discuss several influential writers—Hammett, Greene, Cain, Chandler, Woolrich—and key films such as The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity as examples of “tough modernism” in fiction and film. One of the virtues of the book is its sweep: it covers nearly eighty years of noir on the page and on the screen. Like everything else Jim writes, it’s essential for film fans and researchers. His recently inaugurated webpage displays his range of interests.

The Big Nutshell

Did the 1940s give us the habit of calling a movie The Big Whatever? True, we had The Big Parade in 1925 and The Big Broadcast of 1935 but it seems that the next decade was quite big on bigness. Apart from The Big Sleep (1946), we had The Big Store (1941), The Big Street (1942), The Big Shot (1942), The Big Clock (1948), The Big Steal (1949), and The Big Cat (1949). Many episodes of Dragnet, as both radio show and later TV program, had The Big . . . as their title prefix.

So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink).

So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink).

There are small-scale operations (the short con), as well as complex ensemble efforts using, naturally, the Big Store (fitted out with a fake racetrack wire). The scam shown in The Sting (1973) is a Big Store con. Maurer provides a sociological study as well: “Confidence men, like civilians, mate once or more (usually more) in their lives.” I don’t know exactly how I would have worked in a footnote to The Big Con, but I would have tried.

While Maurer was writing The Big Con, something more sinister was going on. In her four-story farmhouse, Frances Glessner Lee was laboring over the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

These were crime scenes presented on an itty-bitty scale. Little corpses—stabbed, drowned, hanging—are surrounded by the most banal furnishings. Exquisitely miniaturized chairs, rugs, lamps, beer bottles, calendars (“Corn Products Sales Company”) surround the pathetic figures. A woman stares up from a bathtub alongside tiny towels, hanging socks, and even a simulacrum of tap water endlessly gushing. Frank Harris is found drunk and crumpled in front of a saloon; the next scene shows him dead in his cell. What happened?

Ms Lee, a wealthy devotee of criminal investigation, recreated these grim tableaus as audio-visual aids for police training. Exactly how useful they were as pedagogy isn’t clear. The imagery recalls classic mysteries, and it’s not surprising that Lee was a friend of Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason. Yet her scenes have a creepy melancholy quite alien to Golden Age puzzle plots. As a testimony to the 1940s fascination with aestheticized homicide, they’re close to Weegee or Chester Gould. But they’re rendered as fastidiously as a Joseph Cornell box. I see in the Nutshells the populist Surrealism that led, at the other end of the scale, to Wisconsin’s House on the Rock (which began construction in the 1940s).

Corinne May Botz is the David Fincher of the Lee oeuvre. Her camera in The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death gets deep into the scene and renders the most upsetting images with a cold precision that matches the staging. These bits of cloth and plastic, sculpted and arranged with maniacal precision, make death at once childish and bleak. Blown up in Botz’s photos, the scenes radiate anxiety and menace. Dollhouse noir?

Frozen movies

Will Eisner, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” Spirit Comics (3 November 1946).

In Reinventing Hollywood I suggest that techniques we find in the films have their counterparts in popular novels, short stories, plays, and radio shows. Artists in these media were also exploring shifting time frames and viewpoints, voice-over narration, and other devices. I called it the multimedia swap meet, where mass-culture wares were available for use and revision (thanks to the variorum).

A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover.

A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover.

One example is shown at the top of today’s entry: an effort toward optical POV in Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Eisner renders almost all the panels on that page as subjective. At the time, films were exploring the same idea for certain scenes (e.g., Hitchcock’s work), for long stretches (Dark Passage, 1947), and for nearly the whole movie (The Lady in the Lake, 1947).

Of course Eisner’s Spirit tales evoke noir visuals as well–and become more noirish as the Forties go along, at least to my eye. Other cartoonists, particularly Chester Gould and Milton Caniff, push toward the steep compositions and chiaroscuro lighting we find in the films. I’m inclined to say that the movies got there first; I argued in The Classical Hollywood Cinema that noirish visual designs were often recruited for scenes of crime and mystery in the 1920s and 1930s. (A blog entry found examples from the 1910s.) I suspect that artists of the comics adopted those schemas when they started to make cops-and-robbers strips. By the 1940s, though, with Eisner and others, the visual dynamism pushed beyond what we see in most films. Except, as always, for Welles: Mr. Arkadin seems an Eisner comic brought to life.

Vanilla noir

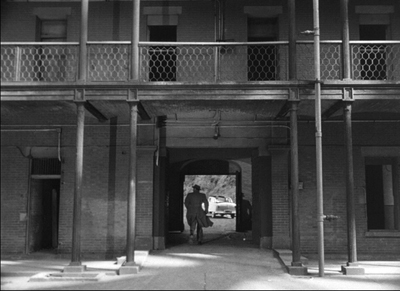

The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950).

Noir is a tricky category because it’s a cluster concept. It can refer to visual style, matters of narrative or narration (haunted protagonists, plays with viewpoint), genre (drama, not comedy), and themes (betrayed friendships, dangerous eroticism, male anxiety). Take away one dimension and you might still be inclined to call the movie a noir. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956) has a noir plotline, but its disarmingly drab images mostly lack the low-key look. And maybe someone would call Murder, He Says (1945) a noir comedy.

A good example of mild noirishness is The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), now made available in a handsome UCLA restoration from Flicker Alley. Ed Cullen is a tough homicide cop lured by a rich woman into a murder plot. He helps her cover it up, but his younger brother, just starting out in the police force, gets too close to solving the case.

The action climaxes in a vigorous showdown in San Francisco’s Fort Point compound. Director Felix Feist, who gave us the better-known The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947) and The Threat (1949), exploits this impressive location.

Most of the film is more soberly shot, but one long take of an interrogation uses the typical Forties image: a low-slung camera, figures deployed in depth and rearranged as the pressure intensifies.

The Blu-ray release includes a well-filled booklet and two excellent documentaries. Brian Hollis pinpoints the use of San Francisco locations and has interesting comparisons with Vertigo. A second short provides background on the participants and the film’s production, with shrewd remarks on the film’s casting by Eddie Muller. I was also pleased to see that the film, full of smokers, includes Hollywood’s favorite brand of the Forties, Chesterfields.

From Sunrise to Moonrise

Moonrise offers a different negotiation of noir conventions. The Criterion Blu-ray release, produced by Jason Altman, makes this 1948 classic available in a much better version than I’ve seen before. I discuss the opening in Reinventing, taking it as an example of a deeply subjective montage sequence, and I posted the clip online as a supplement.

After knowing the film for years, I expected that the 1946 source novel by Theodore Strauss would have some of the delirious prose we get in Steve Fisher’s I Wake Up Screaming (1941). Strauss wrote film journalism for the New York Times, so it seemed likely he would incorporate some of the pseudo-cinematic techniques of voice-over, subjectivity, and the like, as do other crime novels I mention in Reinventing. Instead, the storytelling is standard hardboiled. Here, for instance, is Strauss sketching the buildup of grudges that leads Danny to kill his long-time nemesis Jerry:

Every time his fist smacked into Jerry’s soft side or smashed Jerry’s mouth against his teeth Danny knew he was paying back. He was paying back for that first day at grade school when he was the new kid and Jerry had whipped him with the whole playground backing him. He was paying back for the night Jerry and his gang took him into the alley and tarred him because Jerry said he’d squealed to the principal. He was paying back for the scar on his shoulder left by Jerry’s cleats in scrimmage seven years ago. He was paying back for every dirty crack jerry had ever made about him or his father in public or private, to his face and behind his back. Paying back. Paying pack good.

Borzage’s movie turns this compact backstory into something much more hallucinatory.

The montage intersperses a hanged man with vignettes of his son being bullied from childhood on. First the rippling miasma seen under the credits gives way to blobs appearing as if in reflection. The camera reveals them as mysteriously projected on a wall (or is it a screen?), and then it picks up feet stalking toward the gallows.

Witnesses are revealed standing in the rain, and the camera rises to show the execution as shadows flung onto the wall/screen.

It seems more of a feverish childhood vision of the hanging rather than any veridical presentation. Cut to a view of a baby with a doll dangling over his crib. This traumatic image is followed by scenes of jeering schoolboy cruelty. (“Danny Hawkins’ dad was hanged!”)

It’s a murky, delirious passage. Its tactility, with mud smeared into Danny’s face, admirably prepares us for a film steeped in swamp water and dank foliage. Here, as elsewhere, 1940s filmmakers are rehabilitating the expressionist devices of late silent film.

The rest of the film doesn’t present such overpowering imagery, but by continuing the opening sequence in the present, following Danny as he drifts past a dance pavilion, the narration makes Danny’s fight with the bully Jerry a furious culmination of all the indignities he’s suffered.

The plot traces a familiar Forties trajectory, following a flawed but not despicable man driven to conceal a crime. In the course of his evasions, he tries to make a life with a compassionate woman. There are many wonderful scenes, including a suspenseful ride on a ferris wheel and a lyrical dance in an abandoned mansion. The lawman tracking Danny comes off as gentle and compassionate. The rippling imagery of the opening recurs in the background of shots, as if the swamp were waiting to claim Danny. As Hervé Dumont points out in a bonus conversation with Peter Cowie on the Criterion disc, all this gloom eventually clears to arrive at a sun-drenched resolution quite different from your typical noir payoff. (Though it’s faithful to the novel, as indeed most of the film’s plot is.)

This time around I was struck by the delicacy of Frank Borzage’s direction in the less flamboyant passages. This master of silent cinema knows how to let a pair of hands show distress, an effort toward tenderness, and then rejection.

Borzage was most famous for his feelingful melodramas Humoresque (1920), Seventh Heaven (1927), and Street Angel (1928). He made those last two features at Fox while F. W. Murnau was there, and it’s probably not too much to see the brackish mist of Borzage’s 1948 film as reviving the look of the nocturnal countryside scenes of Sunrise (1927).

Some shots might almost be homages to Murnau’s film.

The compositions remind us that the 1940s deep-focus style isn’t far from the wide-angle imagery Murnau pioneered in the silent era. Although Strauss’s novel gives the Borzage film its title, we’re free to imagine Sunrise (in which the moon figures prominently) as a prefiguration of Moonrise, in which we never see the moon rise.

A final thanks to all who have picked up a copy of Reinventing Hollywood. Apart from its arguments, I hope that it steers you toward some new viewing pleasures.

Film rights to The Silent Patient, whose author has an MFA in screenwriting, have been sold to Annapurna and Plan B. Amy Adams is set to star in The Woman in the Window, from Fox 2000.

It seems that The Woman in the Window owes a debt to more than movies. A detailed profile of its author in The New Yorker suggests that exposure to Highsmith’s Ripley novels at an impressionable age can have serious consequences, especially if you wind up among the Manhattan literati.

Robert C. Harvey offers a careful analysis of Eisner’s Spirit story, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” in The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History (University Press of Mississippi, 1996), 178-191. Interestingly, the chapter is titled, “Only in the Comics: Why Cartooning Is Not the Same as Filmmaking.”

The most comprehensive book on Borzage’s career I know is Hervé Dumont’s de luxe edition Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood (Cinémathèque Française, 1993). An English translation was published in 2009.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Urk.

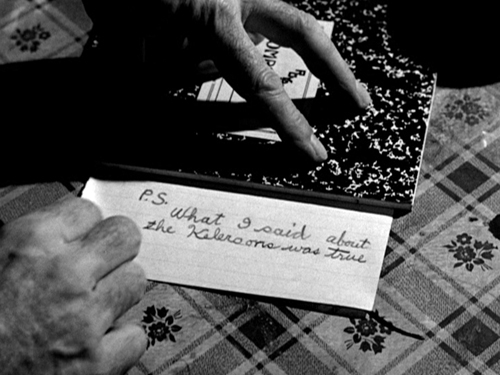

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Eep. I try to do the film, and its genre, justice in another entry.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Omigosh.

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. So I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death: Parsonage Parlor, by Lorie Shaull.

André Bazin, man of the cinema

DB here:

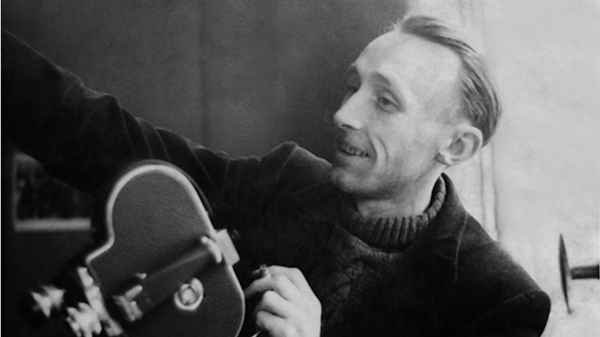

André Bazin was born in 1918 and died on 11 November 1958. In his short life he became, without aiming at it, one of the greatest theorists and critics of cinema.

A central figure in the founding of Cahiers du cinéma, Bazin was also active in building film culture through ciné-clubs and festivals, most notably Cannes and the Festival du film maudit. His writings were poetic, original, and provocative in the gentlest way you can imagine.

As a reviewer he discussed hundreds of releases, and in essay mode he produced subtle reflections on cinema as both medium and art. He wrote about Westerns, pin-ups, Stalinist cinema, documentaries on art and exploration, and of course the commercial storytelling cinemas of France, Italy, and Hollywood. His friendship with two generations of filmmakers–Renoir and Truffaut, among others–gave him a living link to film history. Many would argue that the “young cinemas” of the 1960s, building on both Italian Neorealism and the pictorial styles that crystallized in the 1940s, owe a great deal to the tradition of critical debate he fostered.

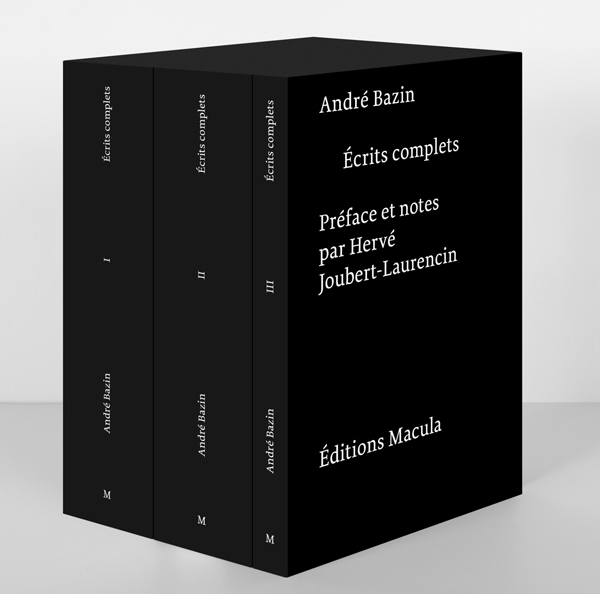

Bazin’s thousands of pieces have now been gathered by Hervé Joubert-Laurencin. A three-volume collection is scheduled to appear this week in a deluxe edition published by Macula of Paris. The press kit, with excerpts, is here.

Beyond reading the work itself, if you want to know more about the man, I think the best place to start is with Dudley Andrew’s biography. It’s a sensitive overview of Bazin’s life and thought, giving particular emphasis to the philosophical and religious influences on him.

Bazin has shaped my thinking about film history and aesthetics since 1967, when I first read Hugh Gray’s translation of What Is Cinema? I taught his work for decades here at Wisconsin, and in On the History of Film Style, I tried to analyze his pivotal role in our understanding of the “development of film language.” That chapter situates his thinking about technique in the context of the “nouvelle critique” of the 1930s and 1940s, a trend that tried to locate an aesthetic suitable for the sound cinema.

Later, I wrote an essay for the German journal montage a/v, which ran a special 2009 issue devoted to Bazin. The original English text, slightly updated, is now available on this site (here, and on the left). That piece suggests how Bazin’s thinking has shaped my own approach to understanding cinema.

Commentators pledged to labels may wonder how a “formalist” like me can find common cause with a “realist” like Bazin. Actually, in both method and substance, his work offers much to the research program I’ve called a poetics of cinema. To see Bazin as being “for” deep-focus and the long take and “against” montage is an oversimplification, it seems to me. He saw more deeply and more widely than that, not least because he was always aware that filmic expression—in style, in narrative—changes across history.

Film criticism owes Bazin an immense debt; he taught us to look closely at what’s onscreen. Elsewhere on this site, we discuss some examples (for example, here and here and here).

There are many ways of thinking about his work, as you can see from the swelling number of articles, books, and conferences devoted to him. He remains a tremendous figure, blending modesty, tolerance, patient attention, close viewing, and bold speculation. Film studies could scarcely exist without him.

FILM HISTORY: AN INTRODUCTION: Not back to the future but ahead to the past

DB here:

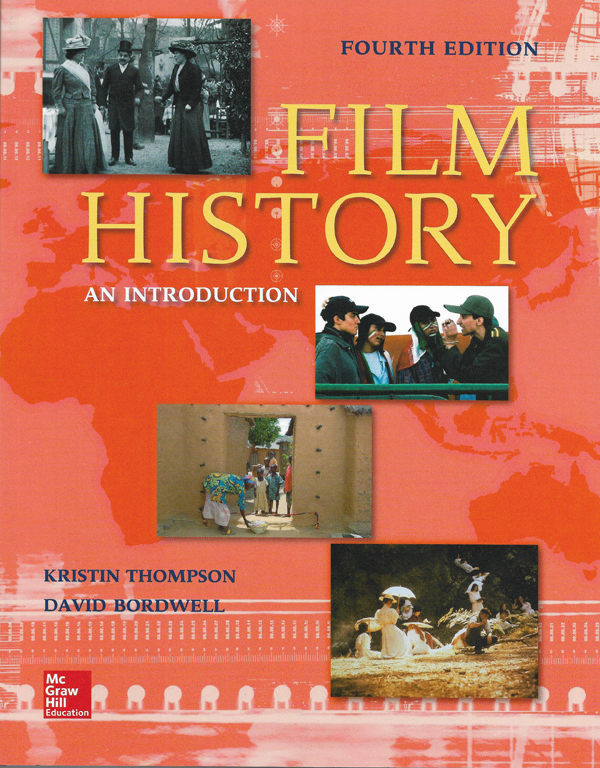

After nine years, here comes another Thompson/Bordwell boulder: Film History: An Introduction in a fourth edition.

When I was in college (1965-1969) my university offered no courses in film. The year after I graduated, two courses appeared: one, a survey history, the other a study of adaptations. Those pretty much defined the early zones of film studies on most campuses.

In the 1970s, however, the survey history was supplemented by a survey of film aesthetics (sometimes called “film language”), which organized the course not chronologically but conceptually. Weekly topics took up categories like “editing” and “acting,” and usually something about adaptation. Eventually the aesthetic survey became more popular than the historical overviews, and often it served as the introductory course for a major. (Film majors were starting then too.)

It’s likely that our textbook Film Art: An Introduction (1979) contributed to the rise in aesthetic surveys. For reasons rehearsed here, we tried to make it more comprehensive and in-depth than earlier books of that type. We tried to synthesize the ideas developed by film researchers about narrative, filmic modes (documentary, animation), authorship, genre, and film as a vehicle of ideology. We also floated ideas about form and style we developed in our research. Film Art‘s approach proved influential; many later books adopted our conceptual layouts, our terms, and our explications of techniques.

We also tried something that wasn’t common in other “film-language” texts. We included a chapter surveying film history. It was short and very selective, of course, but we tried to show that the expressive resources we surveyed conceptually could also be understood as part of a larger historical dynamic.

About a dozen years after the first edition of Film Art, we published our own version of a synoptic film history. Again, we tried to incorporate film research as we understood it, and—

But wait. I already wrote this, back in 2009. To save you a click, let me quote myself, with some light modifications.

The 1970s: More than disco

Star Wars Uncut: Director’s Cut (Casey Pugh et al., 2010).

For a long time, and sometimes still, film histories written by Americans took a very partial look at the phenomenon of cinema. For one thing, they tended to focus on a series of masterpieces, films that had been deemed important within a narrow canon. The earliest lineup went pretty much this way: Lumière films, Méliès’ Trip to the Moon, Porter’s Great Train Robbery, Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and/ or Intolerance. Then came national schools, such as German Expressionism (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), Soviet Montage (Battleship Potemkin), and Continental Dada and Surrealism (Entr’acte, The Andalusian Dog). Early sound was M and Sous les toits de Paris and maybe Love Me Tonight. The 1940s was Grapes of Wrath and Citizen Kane and Enfants du Paradis and Italian Neorealism. And so on.

But in the 1970s archivists began opening their doors to researchers. Thanks to wider and deeper viewing, new film historians, young and old, were questioning the canon. André Gaudreault and Charles Musser showed that Porter’s Life of an American Fireman, which supposedly gave birth to crosscutting, did not do so; in fact the version people had used for years was a re-cut print! In Jay Leyda’s seminars at NYU, young scholars like Roberta Pearson were tracing what Griffith actually did and didn’t do, a task taken up by Joyce Jesionowski as well. At the same time, Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Noël Burch, and others began questioning the idea that “our cinema” developed step by step from “primitive” beginnings. In England, Ben Brewster, Barry Salt, and others were minutely analyzing changes in film technique in the earliest years. Here at Madison, Tino Balio and Doug Gomery were revising the study of Hollywood as a business enterprise. Specialists working on national cinemas, from Russia, Italy, and the Nordic countries, were showing that there was far more diversity in world cinema than was dreamt of in orthodox histories.

We were part of this generation of revisionists. In the 1970s and 1980s Kristin concentrated on European and American silent film, studying both stylistic movements and film distribution. She also studied particular filmmakers like Eisenstein, Godard, and Tati. I studied European and Japanese cinema. We spent years working on a reconsideration of the history of American studio film in collaboration with Janet Staiger. Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 we realized that asking fresh questions was both necessary and exciting.

That’s what made our task perilous. Everything, it seemed, needed to be rethought.

Most obviously, countries outside Europe and North America had been neglected. Our book was, I think, the first synoptic history in English to make use of statistical information on production and exhibition, and the numbers brought out a striking omission.

In the mid-1950s, the world was producing about 2800 feature films per year. About 35 percent of these came from the United States and Western Europe. Another 5 percent were made in the USSR and the Eastern European countries under its control. . . . Sixty percent of feature films were made outside the western world and the Soviet bloc. Japan accounted for about 20 percent of the world total. The rest came from India, Hong Kong, Mexico, and other less industrialized nations. Such a stunning growth in film production in the developing countries is one of the major events in film history.

Traditional histories, and film history textbooks, had virtually ignored the bulk of film-producing nations. Only one or two major directors would step in from the shadows. Kurosawa summed up Japan, Satayajit Ray stood in for India. And the books’ layout of chapters indicated this second-class status.

The history of film was portrayed as Euro-American, with East Asia, Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa, appearing, if at all, in periods when westerners first got glimpses of their film culture. So Japan was typically first mentioned after World War II, when Rashomon won a prize at the Venice Film Festival. One would hardly know that there were many, and many great, Japanese filmmakers working in a long-standing tradition.

As if this weren’t enough, we were determined to include other varieties of artistic filmmaking. Documentary cinema, animation, and experimental film had attracted subtle historians like Bill Nichols, Mike Barrier, and P. Adams Sitney. We weren’t experts in these areas, but we were keenly interested in the debates in that domain, and so, guided by these and other scholars, we sought to integrate the histories of documentary, avant-garde, and animated cinema into our survey.

1980s-2000s: Kristin and David’s excellent adventure

Kristin at Bonded Storage, Fort Lee New Jersey.

In sum, we decided that we could write a plausible international history of cinema—not a be-all and end-all, but a new draft that reflected the rich variety of new findings and fresh perspectives. Like all historians, we had to be selective. We couldn’t, for instance, track every nuance of the “false starts and detours” in early film technique. More globally, we decided to concentrate on three lines of inquiry.

First, we studied changes in modes of film production and distribution. This inquiry committed us to a version of industrial history. How filmmaking was embedded in particular times and places, how it connected to local culture and national politics: these factors affected the ways films were made and circulated. For example, the early distribution of films followed the trade routes of late nineteenth-century imperialism. That global system started to crack with the start of World War I. A new world power, the United States, became the major film exporting country—a position it has enjoyed for most years since then.

Secondly, we studied changes in film form, style, and genre. We treated these artistic matters as not wholly the products of individual innovators but also as more widely-developed practices and norms. This emphasis on norms allowed us to link, in some degree, the development of technique to opportunities and constraints presented by film industries.

This angle of approach also meant looking at older works with a fresh eye, informed by others’ research but also by our own interests in film as an art. We were obliged to seek out films lying outside the orthodox story. Birth and Caligari and M featured in our account, but so did The Cheat and Liebelei and Assunta Spina (1913, below). In those pre-DVD days, few of the titles we sought could be found on video, but we preferred to watch film on film anyway.

So it was off to the archives. Fortunately, many collections were wide-ranging. We saw Egyptian and Swedish films in Rochester, French and Italian films in London, Indian and Japanese films in Washington, D. C., Polish and African films in Brussels. Committed to documenting our claims with frame enlargements, not production stills, we were lucky to be able to take photos from many of the movies we saw.

In looking at national film industries and artistic change, we wanted to go beyond local observations. So a third question pressed upon us. What international trends emerged that knit together developments in different countries? We could not claim expertise in all the relevant national traditions, but we could, by drawing on films and other scholars’ writings, create a comparative study that gave a sense of the broad shape of film history.

For example, we could point to the emergence of tableau cinema in many countries in the 1910s. We could consider various models of state-controlled cinema in the 1930s and discover the “New Waves” that emerged not only in France but around the world in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Citizen Kane popularized a “deep-focus” look, but comparative study showed us that its principles were prefigured in Soviet cinema of the 1930s and spread to most major filmmaking nations in the 1940s.

Not all trends march in lockstep, but there was enough synchronization to let us plot broad waves of change across the 100 years of film. Our aim was a truly comparative film history.

As a kind of overarching commitment, we wanted readers to think about what historical processes had shaped earlier writers’ frames of reference. How, for instance, did the “standard story” and the mainline canon get established in the first place? Part of the answer lies in the growth of film journalism and film archives. Why did Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, and other directors get so much fame in the 1950s and 1960s? True, they made exceptional films, but so did many other directors who remained unknown to a wider public. We suggested that the “golden age of auteurs” owed a good deal to developments in film criticism and to the postwar growth of film festivals.

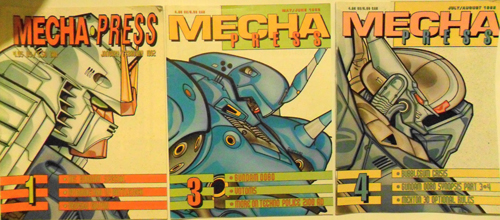

What led Japanese anime to a period of international popularity in the 1980s? Not only worldwide television distribution, but also devoted fans who spread their gospel through videocassettes, the youthful Internet, and such fanzines as Protoculture Addicts and Mecha Press.

In general, the “institutional turn” in film research of the 1970s and 1980s pushed us to consider how film industries and international film culture governed the way films were made and circulated.

The research programs that were launched in the 1970s were characterized by a greater self-consciousness than we had seen before. Historians questioned their assumptions and explanations. Why attribute originality only to “great men” without also examining their circumstances? Why presuppose that film technique grows and progresses in a linear way? To capture this new self-consciousness about purposes and methods, we incorporated something that had never been seen in a film history before: an introduction to historiography. Originally in the printed text, in its latest incarnation it can be found elsewhere on this site.

We also appended to each chapter short “Notes and Queries” discussing intriguing side issues, debates in the field, and topics for further research. Those were put online for download. The third edition’s are here; sample them through the “Choose a Chapter” dropdown menu. The fourth edition’s updates will soon be available.

2018: Results just in

Tangerine (Sean Baker, 2015).

The first edition was published by McGraw-Hill in 1994, a second edition in 2002, a third in 2009—when I wrote the sections you’ve just read. Now we have a fourth edition, published in June. After ten years or so, what’s changed?

We have the same chapter breakdown. Part One deals with Early Cinema, from the beginning to the end of the 1910s. Part Two surveys the late silent era to 1929. Part Three considers the sound cinema up to 1945. Part Four considers post-World War II filmmaking, through the 1960s. Developments from the late 1960s are reviewed in Part Five. The last part deals with the age of New Media, including analyses of changes in Hollywood, the rise of globalization, and the emergence of digital technologies.

We’ve incorporated new lines of research in some early chapters. The chief change involves Alberto Capellani, a director who was little-known before a retrospective at Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna brought many of his works to attention. He worked between 1905 and 1922, making extraordinary films like L’Assommoir (1909) and Germinal (1913), discussed here by Ben Brewster. In the new edition we contrast Capellani’s delicate staging within the shot to the editing-oriented approach of his much more famous contemporary D. W. Griffith. This is the sort of historical contextualizing we’ve striven for in all the editions of the book.

Likewise the availability of films on DVD has enabled us to explore fresh examples of films in the Young German Cinema, the Japanese New Wave, and other movements. We didn’t give up on 35, though. A lot of frames still come from prints. For example, thanks to Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, we were able to obtain a frame from Med Hondo’s extraordinary West Indies.

As you’d expect, the bulk of new material comes in the final stretches. In Chapter 24, we incorporate discussion of The Missing Picture, The Act of Killing, the work of Wang Bing, and the emergence of the animated documentary (Waltz with Bashir, Tower). Our survey of experimental cinema widens to include Liu Jiayin’s work (a favorite of the blog), as well as films by Chick Strand, Marlon Riggs, Phil Solomon (ditto), and Mark LaPore, along with internet experiments like Matt Bucy’s Of Oz the Wizard (2016).

In considering national cinemas outside Hollywood, we catch up with industrial developments in Europe and Russia. Naturally, we take account of new talents, such as Serge Loznitsa and the directors of the Romanian New Wave. The last edition spotlighted many directors still powerful on the international stage, from Almodóvar and Haneke and Denis to Herzog and Varda, but I’m glad we found room for updates on Oliveira and Alexei German, whose beyond-bleak Hard to Be a God (2013) is one of the most tactile films I’ve ever seen.

What do we do with “slow cinema”? We treat it as a development out of classic art-cinema strategies of prolonged duration and “dead time.” We also counterpose it to the nervous “free-camera” style on display in films like Gomorrah (2008) and Toni Erdmann (2016). Our approach to cinema remains comparative, showing how creative alternatives can operate in the same historical period.

DVD availability allowed us to expand our treatment of Nollywood in Chapter 26. There we also trace the emergence of Iran’s Asghar Farhadi (I still admire About Elly) and Cuba’s Fernando Pérez. We’ve especially widened our treatment of Indian cinema, which not only dominates its local market but, in the period since our last edition, has emerged with international successes. I was also happy to learn, thanks to the advice of Lalita Pandit and Patrick Hogan, of the striking films of Rituparno Ghosh. (This hallucinatory scene is in The Last Lear, 2007).

Chapter 27, devoted to Pacific Asia and Oceana, brings those national industries up to date while discussing Taika Waititi, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and others. Of course we retain considerations of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Hong Sangsoo, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and many other major artists. Our box on Sony, which I always liked, has been exiled to the Notes and Queries online, the better to make room for a box in which we pay tribute to the great Hayao Miyazaki. And of course our section on China has been largely redone, to reflect its rise to international power. We analyze how government officials and private investors leveraged a minor national industry into one of the filmmaking behemoths of our time. Not that it always goes well, as The Great Wall (2017) showed.

Similarly, Hollywood changes so fast that we needed to recast many stretches of Chapter 28’s survey. But the search for synergy across conglomerate domains, the shift from one-off blockbusters to franchises, the impulse toward mergers and acquisitions that marry “content” to delivery systems (cable, the internet): these and other business strategies emerged in even sharper relief ten years after our last edition. Fortunately for our timing, the acquisition of Fox by Disney began while the book was in press, so we were able to sneak that initiative into a new box devoted to the Disney empire. Too bad we didn’t have this frame from Ralph Breaks the Internet: Wreck-It Ralph 2 to illustrate that.

Of course American cinema is more than the studios, so we’ve updated our consideration of indie films, with discussions of auteurs, genres, and trends. (Yes, Wes Anderson and Damien Chazelle are involved.) The third edition considered Mumblecore; now we’ve got coverage of directors like Lena Dunham moving to television and streaming.

Chapter 29, on globalization, runs through several trends that are still with us, from piracy and festivals to diasporic filmmaking and the multiplex strategy. We consider how worldwide fan culture has exposed new possibilities of filmic expression, through mashups, video essays, and DIY exercises like Star Wars Uncut: Director’s Cut (2010).

The chapter also analyzes how countries outside the US are trying to make international hits. The Europeans mostly sought to do this through art-cinema channels, while other countries found some success with popular entertainments. Baahubali 2: The Conclusion (2017) garnered $81 million outside India.

Chinese filmmakers have become less reliant on exports, since the stupendous growth of the exhibition sector created a mega-market at home. A hit like Wolf Warrior 2 (2017), which was reported as earning over $850 million, can rival Hollywood’s global revenues within a single territory. Interestingly, the popular successes are often heavily indebted to Hollywood: Baahubali 2 owes a great deal to 300 and other special-effects-heavy spectacles, while Wolf Warrior 2 revives the action style and conventions of Rambo and Mission: Impossible.

For the previous edition, we added a final chapter on digital technology’s impact on cinema. That was as up-to-date as we could make it in the late 2000s, but obviously our treatment needed a big makeover. In Pandora’s Digital Box, I traced how digital tools entered cinema. For FH 4.0 we update that by tracking the changes in preproduction and postproduction, in early efforts to shoot digital, and then in more ambitious production possibilities, along with internet publicity and marketing. We then cover digital convergence, chiefly through Hollywood’s Digital Cinema Initiative’s effect on theatre conversion and digital production.

Naturally, we also analyze some of digital technology’s effects on film form and style: the possibilities of 3D, the opportunities for longer takes and photographic experimentation, and the new prominence of digital animation. A box contrasts David Fincher, whose embrace of digital yielded new possibilities for classical storytelling, with—who else?—Jean-Luc Godard, whose digital work such as Éloge de l’amour (2001, below) challenges just that tradition.

The convergence story wraps up by tracing how digital distribution, beginning with the DVD and passing through online distribution, arrived at piping films directly to theatres. The chapter ends by looking at how the Internet, video games, and Virtual Reality have interacted with modern cinema.

Our emendations and updates bring home to me the advantages of seeing change against a background of continuity. The film industry replays time-honored business strategies, such as the impulse toward vertical integration. Amazon and Netflix, not content with controlling distribution and (home) exhibition, move into production to assure themselves of a flow of product—just as 1910s exhibition chains created studios to supply their screens. And as I write this, the 1948 consent decrees are being reconsidered as anachronistic.

Likewise, filmmakers of the 2010s confront choices about technique familiar from earlier eras. Since a digital shot can be indefinitely long, when should I cut? I can reframe a shot in postproduction, but I still have to decide on the shot scale. With highly spatialized sound in theaters, where should I locate this effect? Even with new technologies and changing circumstances of reception, the basic demands of form and style persist.

Here’s a taste of our conclusion:

Digital convergence worked hand in hand with globalization and the power of the American studios. The top Hollywood pictures were successful in most countries, and they could be delivered on many platforms. But in the swift media churn, with new formats coming up all the time, would traditional filmmaking die?

Evidently not. For one thing, the number of feature films was surging. In 2002, the world made over 4,000 feature films. In 2016, that number was over 7600. This vast output included blockbusters, modest independent films, and every form in between. The boom took place in the face of home video, cable, satellite, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, and streaming. It happened despite the fact that a handful of American blockbusters ruled nearly every national market.

But perhaps theaters, the public side of film culture, were in danger? Just the opposite. Screen growth was robust through the 2010s. In 2016, the world had over 163,000 screens. Even without counting the millions of television monitors, computers, and mobile devices, there were far more movie screens than ever before. And plenty of people wanted to visit them. The year 2015 set a record high in worldwide attendance, 7.4 billion admissions. This amounted to about one ticket for every man, woman, and child on Earth.

Digital convergence, boosted by globalization, encouraged the spread of cinema. Personal computers, the Internet, mobile phones, game consoles, tablets, and portable music devices initially could not display films, but all were eventually adjusted to do that. Film wriggled its way into every media device that came along. From broadcast television and videotape to DVD and streaming, films spread beyond the theater. They entered our living rooms and went with us anywhere. Today, more people are watching more hours of motion pictures than at any other time in history. As newer technologies emerge, we suspect that they too will serve the cinematic traditions that have developed over 120 years.

Optimistic, eh? Yep, that’s us. We know that the book is far from perfect, and we’ll be trying to correct mistakes and misjudgments. Still, we hope that Film History: An Introduction tells a story that will encourage young filmmakers and filmgoers to embrace all the traditions of cinema. Those traditions have fascinated us for fifty years, and we hope to communicate some of our enthusiasm to readers.

Film History: An Introduction’s fourth edition is available in several formats, some frankly innovative. To understand why, it’s useful to try to answer the constant question: Why are college textbooks so expensive?

There are plenty of factors to consider, of course, but I want to focus on just one. Much of what follows is my personal speculation, but I think it makes sense if we entertain the prospect that people can act as rational agents.

The professor rationally decides that she wants her students to read a specific book in order to study aspects of the subject. She assigns it.

Some students will decide to borrow a copy, check out a library copy, or risk not reading the book at all. Those are all justifiable courses of action. But many students, deciding that owning the book will help them succeed in the course, buy it. Still, (a) it’s pretty expensive; and (b) they may not wish to keep it after taking the course. Textbooks are among the few books which users are forced, more or less, to buy.

Many students want to recoup part of their investment, so they resell the book for what they can get. Jobbers and campus bookstores buy the books and resell them to new students. Those folks, themselves rational agents, are glad to get a lower price. I speak as someone who’s bought thousands of used books, including textbooks.

But the publisher and authors reap no rewards from a resale, which replaces the purchase of a new copy. It seems likely (though I have no evidence that this shapes our or any company’s decisions) that publishers assume that nearly all purchased textbooks will be resold. Therefore, in order to maintain profitability, the publisher could set the price (wholesale/retail) at a point that will offset at least one future resale.

So the real cost to the student is the difference between what she pays initially and what she can get on buyback. A $100 textbook might be sold back to the bookstore for $25 or $30. If it’s in decent shape, it could be resold for $60 or more. The money the store gets doesn’t flow back to the publisher, and the student in effect rented the textbook for $70-$75.

So the real cost to the student is the difference between what she pays initially and what she can get on buyback. A $100 textbook might be sold back to the bookstore for $25 or $30. If it’s in decent shape, it could be resold for $60 or more. The money the store gets doesn’t flow back to the publisher, and the student in effect rented the textbook for $70-$75.

This has all the marks of an arms race. If publishers raise prices to offset resales, this gives purchasers a greater incentive to resell, thus flooding the market with more used copies. Publishers could also speed up the revision cycle, hoping that new editions will render the old ones less desirable.

I stress that this line of reasoning is my own thinking. Yet it’s evident that the textbook market has presented accelerating prices and triggered growing resentment among faculty and students. Even college administrators have joined the complaint about price rises. (Said administrators aren’t usually inclined to lower tuition, however.) In recent years, the pressure got more intense thanks to two other factors: digital piracy and Amazon.

Start with piracy. Once pdfs of a textbook show up online, publishers suffer big losses. That could prod them, as rational agents, to raise the purchase price. (Lowering the price might seem a way to undercut pirate copies that are sold, but you can’t make the book cheap enough to make a difference.) In effect, when somebody buys a textbook they’re helping subsidize someone else’s download. This creates an incentive for rational agents to download the text themselves, thus pushing the price of the physical book ever upward.

As for Amazon: In past decades, the used-book jobbers were quite adroit at distributing used copies to campus stores, but Amazon’s online model proved far more efficient. Moreover, Amazon revived the long tradition of renting books, and the economies of scale made it easy. As rational agents, the Amazonians bought copies from the publisher and then offered them for rent.

Other companies rent textbooks too, on a smaller scale. In all cases, renters are vulnerable to the frailties of human nature. You can read sad stories of renters who failed to return the book in a timely fashion and ran up charges greater than the cost of a straight purchase.

Publishers have responded to Amazon’s rental initiative by launching rental programs themselves. This is what McGraw-Hill has done with our book.

Let’s go through the options. If you go here and then click on “Print/ebook” and “Bundles,” you can see them all.

Film History exists in both digital and print form. The digital edition may be bought or rented. There’s also the option to fold the e-book into a broader platform called Connect, which gives access to a rich array of material: study aids, an ebook format, questions, video supplements, and more.

The book exists in hard copy as well. It can be rented as a bound volume. Alternatively, it can be bought in a loose-leaf version. If I were buying it, that’s the format I’d pick.

Prices across all these options range from rentals for $60-$80 and purchase for $118–$130.66 and mixtures of both for up to $150.

What about buying the bound version? As you’d expect, that’s the most expensive option. McGraw-Hill offers bound copies on a rent-to-own basis. As I understand it, the customer first rents the book and if she decides to keep it, she pays the rest of the full price. That price is currently $229, a lot, but following my line of reasoning, that price would offset possible resales.

Anecdotes suggest that film majors hang on to their books and try to build personal libraries. If that’s true, I’m happy, for more than one reason. And I learn that Film History will continue to be sold in bound copies outside North America. In my experience, overseas students don’t complain as much about the cost of books, perhaps partly because they attend schools that have low or no tuition fees.

Would I prefer the old days, when you just bought the book and owned it or sold it or gave it away? As a book collector, I would. But Kristin and I are old, old school; we have thousands of volumes in our library. (Many of those won’t be online in our lifetime.) And we also have dozens of e-books, which are great for ephemeral reading or sturdier research. We recognize that publishing, and authoring, are changing because of technology and social dynamics, and so we adjust. The main thing is to get ideas and information and opinions out there for our readers to consider.

For this edition of Film History: An Introduction, we want to thank the staff at McGraw-Hill Higher Education: our editors Sarah Remington and Alexander Preiss, and their colleagues Jen Thomas, Anju Joshi, and Ann Marie Janette. They have helped us make this edition something we’re very proud of.

Sita Sings the Blues (2008, Nina Paley).

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

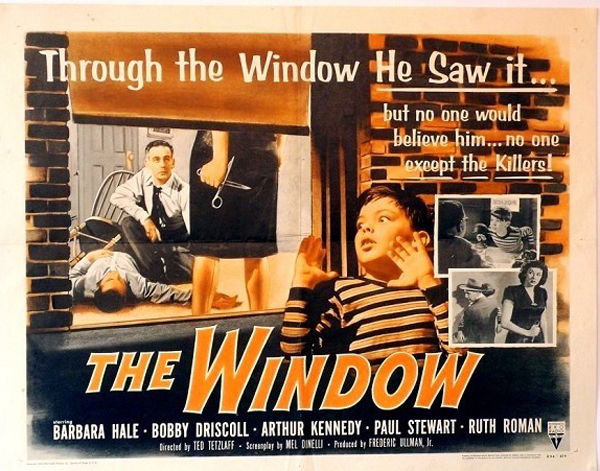

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

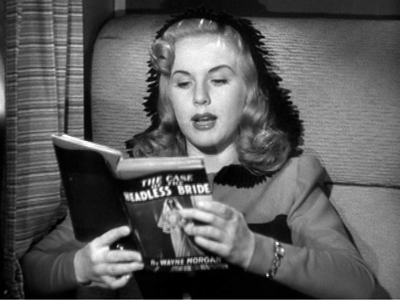

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

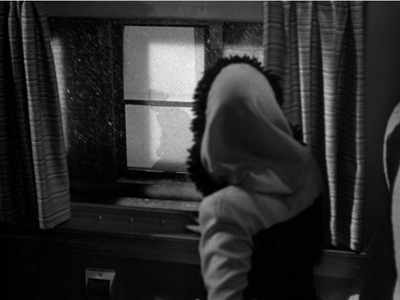

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

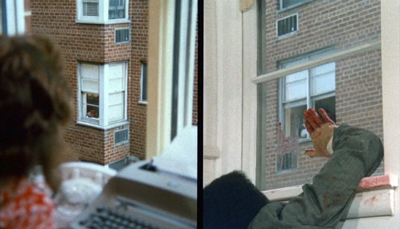

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

At the window, and outside it

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

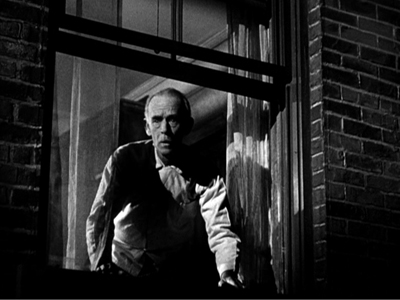

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.