Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction, and (sometimes) recovery

Kristin here:

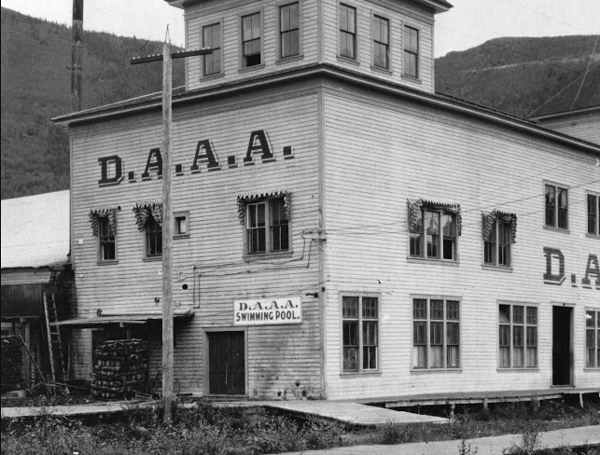

Many readers of this blog have heard of the Dawson City Film Find (hereafter DCFF), as it is called in Bill Morrison’s extraordinary documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time. How in 1978 work on a construction site in Dawson City, Canada, led to the discovery of hundreds of reels of nitrate films packed into a swimming pool in 1929, covered over, and forgotten. How these reels turned out to be from silent films, mostly from the 1910s, many of them previously thought entirely lost.

Few will know the story in the detail with Morrison provides, nor will they know the rich historical context that he provides for the discovery and recovery of the reels. His film is not, however, simply a presentation of the DCFF. It’s about growth, loss, recovery, and destruction in several areas, all circling around Dawson City as their hub. The subtitle “Frozen Time” is a bit misleading. The reels of nitrate sealed away in the permafrost were no doubt frozen, and the temporal fictional and newsreel images they contained were lost for decades.

Morrison, however, weaves information about a variety of other subjects together in a way that makes the passage of time palpable for us. We see its effects on people and places and discover the odd, fortuitous connections among them in a dizzying fashion.

A complex film like this deserves an extended commentary, which I offer below. There are spoilers galore in it, and I would suggest seeing the film before reading this. It should appeal to anyone interested in early cinema, in North American history, and in documentaries in general. Kino Lorber has recently released Dawson City: Frozen Time on Blu-ray, with extras including eight films from the DCFF.

Easing into the past

The films-in-a-swimming-pool hook is what Morrison uses to lure us into his larger historical weave. He begins with a hint of the recovered footage, showing a baseball game which will later be revealed as the scandalous 1919 World Series where White Sox players were bribed to throw the deciding game. Then we see briefly see Morrison himself being interviewed by a talk-show host, followed by a lady in 1890s costume enthusiastically introducing a premiere screening of some of the restored films for an audience in the Palace Grand. That theatere is a modern reconstruction of the first theater built in Dawson City, used for live drama, opera, eventually films, and other forms of entertainment.

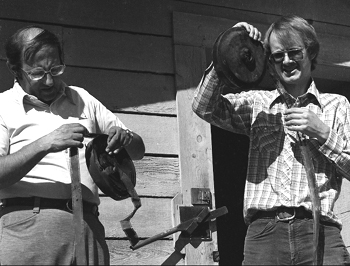

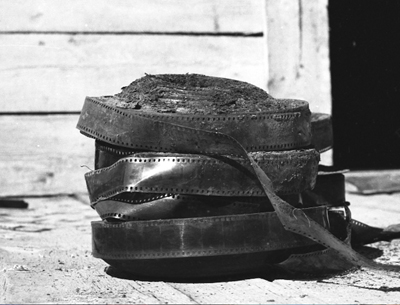

We move by stages back into history. Fifteen months before the premiere the discovery was made: a man running a back hoe turned up reels and coils of film. We meet the protagonists of the film-discovery portion of Morrison’s tale: Michael Gates, curator of Collections at Parks Canada from 1977 to 1996, and Kathy Jones-Gates, Director of the Dawson Museum from 1974 to 1986. She was Kathy Jones at the time of the discovery; this tale even has a romance, since the pair married after working together on the recovery of the buried reels. The couple describe the initial find, over still photos of mud-covered reels taken with Jones’s camera (above).

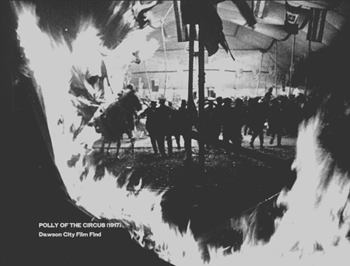

Morrison now takes us further back, to demonstrations of how nitrate film was made (with extracts from a 1937 film optimistically titled Romance of Celluloid) and how it is prone to catch fire and burn fiercely. The well-known 1897 Charity Bazaar disaster in Paris is cited, while film of a burning tent and fleeing spectators is shown. No visual record survives of the Charity Bazaar disaster, not even photographs. News accounts used engravings as illustrations. The burning tent footage is from a film released twenty years later, Polly of the Circus (1917), one of the main lost films recovered in the DCFF.

Morrison does not hide this source but superimposes a caption giving the film’s title, date, and source. This is the first time he draws upon DCFF images to evocatively represent real historical events. Later in Dawson City, the mention of an actual person, such as Gates, sending a letter will be accompanied by a montage of letter-reading moments culled from DCFF films. It’s a clever way to add a little humor and to show off a wide variety of the titles without dwelling on long clips from any one film.

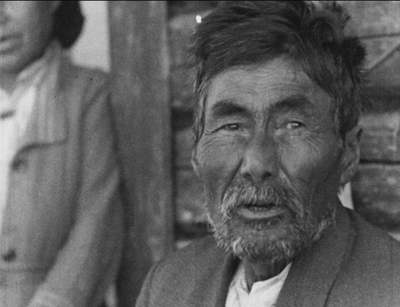

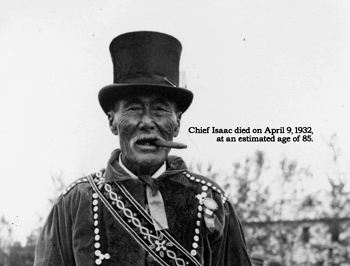

Having established the destructibility and danger of nitrate, Morrison flashes back to the earliest period portrayed in the film. Epic photographs show forested landscape. The narration, done with captions rather than voiceover, informs us that for millennia the area where the Klondike River flows into the Yukon has been the hunting grounds for one of the First Nations, the “native Hän-speaking people.” (The footage is from City of Gold, the famous 1957 Canadian documentary about Dawson City, which will become more important later in Morrison’s film.) A photo introduces Chief Isaac, leader of one subgroup of the Hän.

Nothing is said at this point, but the fate of these hunting grounds initiates one of the major threads recurring through the film, that of ecological destruction.

The third major thread is the history of Dawson City itself, which is as fascinating as the story of the buried films. In late 1896 or early 1897 one Joseph Ladue claimed 160 acres as a town site, where he sold lumber and lots to prospectors. By the summer of 1897 there were 3500 residents, and Morrison uses population figures to trace the wide swings in the town’s fortunes over the decades.

At this point the Northwest Mounted Police relocated the Häns’ village five miles downriver, and their fishing and hunting grounds were destroyed by mining.

During the descriptions and facts about the huge amounts of gold coming out of the area, Morrison introduces other motifs and threads. He mentions that Jack London was among the prospectors. He was the first of several writers and theater figures who were in the Yukon, often during these early years. Most of them resurface late in the film later on, turning out to have surprising connections with the history of the cinema and each other.

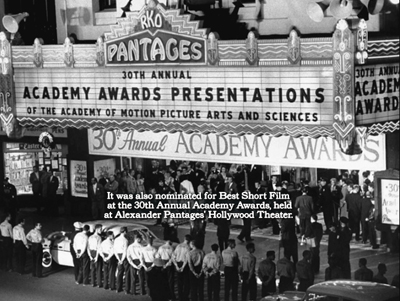

Famous entrepreneurs of later years got their starts here. Sid Grauman was a newspaper boy who eventually went on to build a theater chain, including the Egyptian and Grauman’s Chinese in Los Angeles. Ted Richard, who staged boxing matches in the Monte Carlo theater, later founded the New York Rangers and rebuilt Madison Square Garden. Alex Pantages started as a bartender, rebuilt Dawson City’s Orpheum theater after it burned to the ground in 1899 and showed traveling programs of early movies. He became one of the first major film tycoons, building a string of 70 theaters in North America.

The Gold Rush frozen in time

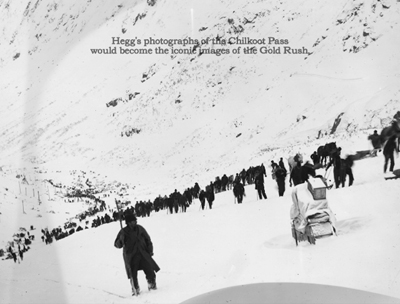

One of the revelations of Dawson City is the work of photographer Eric Hegg, who traveled to the Yukon alongside with the hordes of hopeful prospectors. He, however, worked as a photographer, and shot thousands of images that became, as Morrison’s caption says, “the iconic images of the Gold Rush.” The one above shows the arduous and crowded journey up over the notorious Chilkoot Pass. Chaplin later staged a remarkably similar scene for The Gold Rush (1925), though whether he could have seen Hegg’s images is unclear.

By the summer of 1898, the population of Dawson City was around 40,000, and the richest claims were all taken. Businesses were set up to cater to the prospectors, including Hegg’s photographic studio. Saloons, casinos, theaters, as well as more practical boat-builders and banks sprang up. Of the two initial banks that opened branches, the Canadian Bank of Commerce is the more important to Morrison’s story, since it eventually acted as the Dawson City agent for distributors sending films to town.

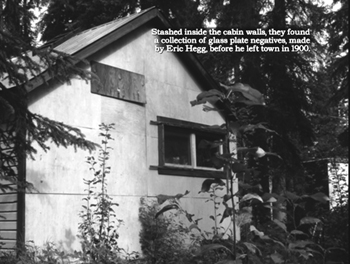

The first boom ended in the spring of 1900, after the announcement of a gold strike in Nome. Three-quarters of Dawson City’s population left, including Hegg, who left his collection of glass negatives with his partner, Ed Larss. He opened a new studio in Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush.

After his departure, Hegg disappears from Dawson City for quite some time. His work there, however, was also fortuitously rescued from oblivion. Twenty minutes from the end, we are introduced to Irene Caley and Will Crayford, who married in 1947 and decided to move a cabin from Dawson City to Rock Creek. Inside the walls they found hundreds of Hegg’s glass negatives. How they got there is unknown. Coincidentally, Hegg died in 1947, presumably unaware of the recovery of his early negatives.

The newlyweds proposed to strip the emulsion off the plates and use them to build a greenhouse. Luckily a local shopkeeper recognized their nature and gave the couple plain plates in exchange for the 93 glass ones, as well as 96 nitrate negatives. He donated the collection to the National Museum of Man in Ottawa. Arguably this rescue is as significant as the DCFF, especially given that Hegg’s photographs mostly survived in beautiful condition and constitute the best record of the Gold Rush’s first stage.

In 1949 a book of Hegg’s photographs, edited by Edith Anderson Bccker, was published as Klondike ’98.

Subsequently documentary film director and producer Colin Low saw the plates in Ottawa and was inspired to make City of Gold (1957), co-directed by Wolf Koenig. City of Gold, which drew extensively on Hegg’s images, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Short Film. The awards ceremony took place at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles, built and owned by the same Alexander Pantages who launched his theatrical career in Dawson City. It would be nice to think that whoever attended that ceremony representing City of Gold saw the connection.

In 1900, Hegg moved to Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush. His post-Dawson City photographs also survive. The University of Washington’s collection contains over 2100. Its library offers a short biography and a generous sampling of those photographs here.

Weaving the threads together

Dawson City’s second boom was less spectacular but more ominous. The White Pass Railroad made Dawson City more accessible, and heavier equipment was brought in: giant hoses to break up the ground, sluices to convey the ore to a central locale, and so. Miners brought their families to live in Dawson City, with the population steadying at 9000. Various institutions, including banks, the Carnegie Library (above), and, in 1902, the huge Dawson Amateur Athletic Assocation (DAAA) building was built, with an auditorium, billiards room, bowling alley, skating rink, and swimming pool (top). I can’t summarize the whole film, but by this point Morrison has introduced enough people and places to start connecting them up in unexpected ways.

One such thread meanders like this. The celebrity motif returns at about this point, with Marjorie Rambeau (later to have a career as a character actress in movies from 1917 to 1957) performing in Dawson City with a traveling theatrical trouple. Rambeau is not significant here, but Fatty Arbuckle was also in the cast. This information is accompanied by a frame from Fatty’s Day Off (1913), a film discovered in the DCFF.

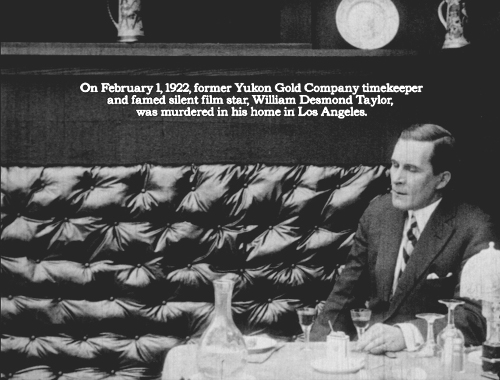

Shortly after this, we hear of two further celebrities-to-be who were in Dawson City. In 1908, poet Robert Service arrives to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and the following year he writes his first and best-known novel, The Trail of ’98 (1909), about the Gold Rush. From 1908 to 1912, William Desmond Taylor works as a timekeeper on a large gold-mining dredge belonging to the Yukon Gold Company, founded by Daniel and Soloman Guggenheim in 1907. These dredges handled most of the mining, throwing many out of work and causing Dawson City’s population to shrink to 3000. Huge dredges would continue to grind down the land for decades.

In 1912, Taylor left for Hollywood, where he enjoyed a short but prolific career as an actor and director, before, as Morrison foreshadows, his untimely death.

These people disappear for a time, and we learn that in 1911 the auditorium of the DAAA was turned into a movie house, the DAAA Family Theater. Other theaters in town went over to showing films. Morrison conveys this via an amusing montage of shots of people in cinema and theatrical audiences, all from DCFF films. He also provides a quick summary of disastrous nitrate fires during the early 1910s.

There follows a long interlude of coverage of the suppression of laborers and leftists during this period, in part to show off some of the newsreel footage preserved in the DAAA swimming pool. These include the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, the “Silent Parade” protesting violence against African-Americans in 1917, and the World Series scandal of 1919.This somewhat tangential though interesting foray into politics also serves to bring us forward nearly a decade.

The Solax studio fire, which also happened in 1919, provides a rather wobbly transition back to film and Dawson City as the end point of a film distribution line. The population has sunk to 1000 by this point. Since the films shown in the town during this decade were not shipped back to the distributor, many of them were stored in the basement of the Carnegie Library and continued to be through the 1920s.

A long, effective montage of shots from various DCFF films follows, beginning with people listening through doors and going through them, so that we get the impression of a giant house with dozens of people sneaking around. This is followed by shots of men attempting to embrace women and being repulsed.

The last of these is from The Kiss (1914), starring William Desmond Taylor. A caption announces his murder in 1922.

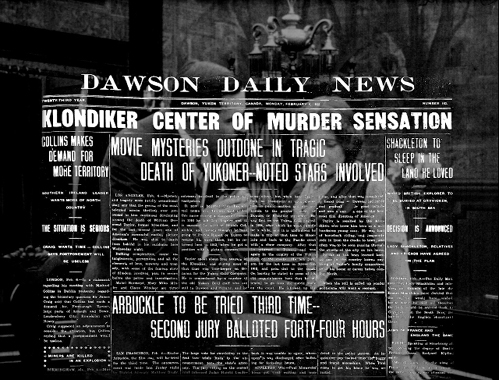

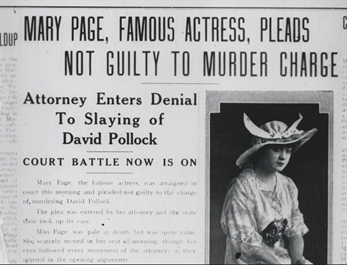

A Dawson City newspaper page announcing the murder and calling Taylor a “Klondiker” and a “Yukoner” is superimposed over another image from The Kiss. Coincidentally, just below this story is one about Arbuckle’s second murder trial ending in a hung jury. The second Taylor headline points out: “Noted Stars Involved.” One of these was Mary Miles Minter, and Morrison shows her in a film, The Little Clown (1921), from the DCFF. Minter had acted in films directed by Taylor, though this is, alas, not one of them. It was however, discovered among the DCFF films. Not one to quit there, Morrison cuts to a shot from another DCFF film, The Strange Case of Mary Page (1916), which has a plot that resembles Taylor’s case.

That two Hollywood directors should have been linked to murder cases, one as victim, one as alleged perpetrator (Arbuckle was never convicted), was certainly a gift to a director keen to stitch as many elements of his film together as possible through associations rather than straightforward historical causes.

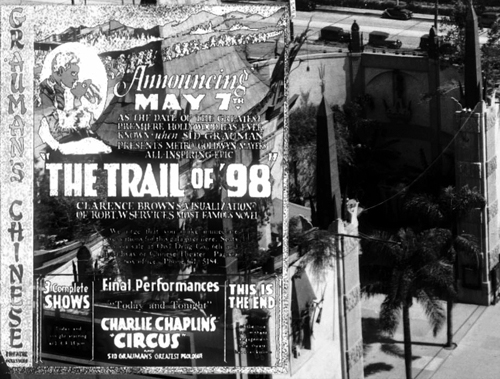

Other connections are less elaborate. At the point where the story of Dawson City has reached the late 1920s, The Trail of ’98 (1928), an adaptation of the Robert Service novel mentioned above, is shown via a superimposed poster to be screening at Grauman’s Chinese, another chance confluence of two people who could not have crossed paths in the Yukon, since Grauman left there in 1900.

The burial

All this material has brought us to the point when the accumulating films in the library basement were transferred to the DAAA swimming pool. By 1928 Dawson City had developed a “modest season tourist industry.” Chief Isaac, whom we met early on, had become mayor of Moosehide (above). And Clifford Thomas, the man responsible for putting the film reels in the swimming pool, moved to Dawson City to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce. He also became the treasurer of the Dawson Amateur Hockey League, which played on the ice rink installed annually over the swimming pool.

In 1929 the library storage had reached capacity, and when Thomson inquired of the studios what he should do with the films, he was instructed to destroy them. At about the time, it was decided to fill in the pool so as to allow for a the skating rink to get rid of a broad bulge caused by the pool’s cover. Thomson made the decision to use the reels as fill in this conversion. Numerous other reels were burned or thrown into the Yukon River–a standard way of disposing of trash.

Morrison could have skipped back to the recovery of the films roughly fifty years later, but instead he continues the Dawson City story. First, he poetically indicates the long decades the reels spent sealed underground with a montage of women asleep, all drawn from DCFF films. The talkies finally reach Dawson City, and more silent reels are dumped or burnt. Chief Isaac dies in 1932.

Parades continue to celebrate the Gold Rush heritage, as recorded by George Black, an avid local amateur cinematographer who recorded several events shown in Dawson City. The one below took place in 1941.

By 1950, the population of Dawson City dropped under 900 people. The last theater was torn down in 1961, though the replica of the Palace Grand went up as a multi-purpose facility in 1962.

On November 15, 1966, the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation closed down its last dredge. A lengthy drone shot flies high over the tortuous, unnatural landscape that resulted from many decades of grinding down and spewing out the land (bottom). The ecological thread has not been emphasized through most of the film, but it comes to a devastating conclusion.

Morrison reaches the discovery of the reels in 1978, and Gates and Jones-Gates resume their story. They contact Sam Kula, Director of Audiovisual Archives, 1973-1989 at the National Archives of Canada. Kula comes to Dawson City, and he (left) and Gates (right) investigate the sodden reels of film.

Kula initially suggested donating the films to the local museum and contacted Kathy Jones. She helped dig up the films, which turned out to be far more numerous and buried far more deeply than they imagined. A newspaper item about the find led to a letter from Clifford Thomson. His explanation of how he had arranged for the films to be put in the swimming pool solved that mystery and provides us with our basic knowledge of the origins of the reels.

The rest of the film’s tale of the reels’ discovery follows how the three rescuers tried to ship the thems to the National Archives of Canada, with several truck, bus, and air services refusing to deal with nitrate film. In November of 1978 a Canadian Air Force plane delivered 506 reels to the Archives.

Morrison ends with a series of shots from various DCFF films with heavy deterioration. The thread of nitrate’s flammability and the recounting of numerous nitrate fires finds its quiet ending in the film’s lengthy final shot. A female dancer performs a modern dance that apparently expresses anguish. Blank white flashes flicker across the frame, suggesting that the dancer is being enveloped by the flames generated by nitrate film.

It is a fitting ending to a film that blends fascinating information and poetic associations in equal measures.

Some caveats

Despite my considerable admiration for Dawson City: Frozen Time, I have to take issue with some of the descriptions in this last part of the film. The narration does not point out that most of the films recovered were incomplete–not surprisingly, given how many reels were burned or otherwise destroyed. A film historian would assume that. A casual viewer would not. Similarly, there is an explicit statement that “every other copy” of these films had been lost to fire and decay. Some of these films, however, survived elsewhere, and sometimes in better copies.

The reception of the film has, through no fault of Morrison, distorted the significance of the DCFF considerably further. This evidently started with a extensive article in Vanity Fair that dubbed the DCFF “The King Tut’s Tomb of Silent-Era Cinema.” Numerous reviewers picked up this idea and repeated it, as when Kenneth Turan began his review, “It’s been called the King Tut’s Tomb of silent cinema, a celluloid find at one of the world’s far corners that dazzled the film universe.”

I cannot think of a more inapt comparison. Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of only two largely undisturbed royal tombs from the entire three-thousand-year history of ancient Egypt, and it is far and away the more important of the two. Despite the tomb’s small size in comparison with others in the Valley of the Kings, an extraordinary number of intact royal grave goods came from it–about 5000 of them (a small sample shown above). Indeed, most of what we know about ancient Egyptian royal grave goods is derived from those pieces. Tutankhamun’s tomb is, as far as we now know, unique.

In contrast, there have been many hundreds of discoveries of original silent films. One of the most notable is the Desmet collection in the Netherlands, which contained over 900 films, most of them complete and in excellent condition. Other such discoveries have ranged from single prints to large collections. Those who have discovered and restored these films are still building the international archival holdings of silent cinema. The Dawson City find is simply one important contribution to this extensive and ongoing effort.

Sam Kula himself wrote, “No-one familiar with the considerable resources now accessible through the work of film archives throughout the world would seriously argue that the Dawson Collection, or any one cache of early film, will lead to a wholesale re-write of the histories.”

The story continued

Morrison essentially ends his account when the films leave Dawson City, which is quite understandable. But the viewer might ask what happened next. There is little attention paid to the lengthy, complex procedures necessary to rescue the films from the effects of their long burial and to transfer their images onto modern negatives.

The Blu-ray release contains a nine-minute supplement, Dawson City: Postscript, which does trace some of the subsequent history of the rescued reels. We see the washing of the films in the Canadian facility, as well as the storage facilities in which the original films were stored once they had been duplicated. In the US, the Library of Congress’ 388 reels are now kept at the Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia, which David visited and blogged about earlier this year. Morrison maintains his history of Dawson City as well, noting that in the summer of 1979 the town suffered a disastrous flood and that the premiere of some of the restored films took place shortly after that, on September 1.

At first glance, the Dawson find seems to have been handled in a casual way, with local administrators who were not film archivists digging up reels with shovels and handling them in a way that today would seem reckless. Some have assumed that considerable unnecessary damage was done to the films after their discovery. Yet no written account of the whole affair has yet been published.

I asked our friend Paolo Cherchi Usai, Senior Curator of the Moving Image Department of the George Eastman Museum, for his opinion. He kindly gave me his account of the rescue process, which suggests that the original participants in Dawson City did the best they could under extremely challenging circumstances.

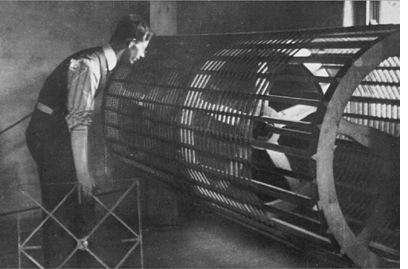

As Paolo wrote in introducing his description, “Please note that what I know is just a matter of oral history — things I heard from the protagonists and witnesses of the events, several years ago. Also, I have not yet seen Bill Morrison’s film.” Others may be able to correct or expand upon some of what Paolo has written. Still, it provides a very informative and useful summary of the rescue process. (I have identified the people mentioned below in brackets. The undated image of a silent-era drying drum is the only image in this entry that is not from Dawson City: Frozen Time.)

In my opinion, the rescue of the Dawson City was a miracle of improvisation and initiative achieved under extremely difficult and often adverse circumstances (see below). In all fairness, I can’t call it a disaster (I can think of other occurrences in my field where that term could rightfully apply). In hindsight, it is all too easy to point out the mistakes made in the process; back in 1978, archival practices were less sophisticated than they are now.

The comparison with Tutankhamen’s tomb is indeed excessive in regard to the aesthetic importance of the films; there is no exaggeration, however, in pointing out the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the discovery, and the steps taken in a very short period of time. You don’t find silent films in a frozen swimming pool that often. When you do, the historical value of the artifacts is not an issue. You want to save all the objects, and then find out their worth. That’s the main reason for the mystique surrounding the discovery; that’s also why I heard about it as soon as I started studying silent film history and film preservation.

It must be pointed out at the outset that the film reels found in the layer right under the permafrost that covered the swimming pool were already decomposed. Nothing could be done to save those prints. It is my understanding that preliminary identification work was undertaken at Dawson City, and that such work was implemented in a cold area. It may be argued that there was no particular reason why this work had to be done there instead than later in Ottawa, but that’s what happened. The late Sam Kula, one of the protagonists (together with Bill O’Farrell [Head of Film Preservation, 1975-2002, National Archives of Canada] and Paul Spehr [former Secretary for the Motion Picture Section of the Library of Congress and Assistant Chief of the Motion Picture Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress], among others) of this story, may have been able to explain this.

The reels gradually thawed in at least three stages, during their transfer to a) an air-force base near Dawson City; b) the National Archives in Ottawa; c) the Library of Congress. The thawing could perhaps have been minimized (if not avoided altogether) if the material had been processed in a refrigerated area from beginning to end. This didn’t happen. The nitrate unit at the National Archives of Canada had been shut down to make room for operations on safety materials, and no special precaution could apparently be taken while dividing the collection in two main groups: the Canadian newsreels to be kept at the National Archives, and the American films to be sent to the Library of Congress.

Bureaucracy was the nemesis of the Dawson City rescue project. The only way Bill O’Farrell could bypass it was for him to personally transport the reels of American films from Canada to the US by car, in a large station wagon, from Ottawa to Suitland, Maryland. His heroic feat — perhaps the most important of his career — would have hardly been possible today. He had no choice; following the usual protocol would have taken months, and the emulsion on the prints would have melted completely. Paul Spehr did his part by having the films accepted into the collection in record time, without following the standard acquisition procedures at the LoC. O’Farrell had alerted Spehr that “there is water in the cans” — this is what Spehr heard on the phone, and he expected this to be the case when the material arrived. It’s not that the reels were drenched in a pool of water in each can; but there was water. The prints had thawed.

In that situation, it was deemed necessary to do something about that water. The technical staff at LoC designed and built  a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

To reiterate the point, the whole story has always been described to me as an emergency rescue performed at breakneck speed, a chain of events where careful advance planning could not be part of the picture. The only way to avoid the partial loss of the emulsion would have been to undertake the entire process in a much colder working area. By the time the reels reached Dayton, however, it would have already been too late to apply such a solution, even if a low-temperature processing area had been available. All that could be done at LoC was to “stabilize” the material long enough for it to go through the printers for duplication.

So that’s that. I hasten to add that my recollections raise a number of questions to which I have no answer.

Our thanks to Paolo for filling in so much of the rest of the story of the Dawson City Film Find.

Thanks to Jonathan Hertzberg of Kino Lorber for his assistance.

The Sam Kula quotation comes from his account of the DCFF rescue, “Rescued from the Permafrost: The Dawson Collection of Motion Pictures,” which can be found on Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archvists #8 (Summer 1979), reprinted from American Film (July 1979).

A brief description of the “Public Archives of Canada/Dawson City Collection” is on the Library of Congress “Motion Pictures in the Library of Congress” page.

Mmm, M good

DB here, boasting about Kristin:

Our series on the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck continues with this month’s entry, Kristin on M as an exceptionally rich sound film. She talks about how Lang adapted silent-film techniques to the demands of sound while also using sound to achieve effects that couldn’t be achieved purely through images.

Watching her discussion and the clips, I was reminded of what a precise director Lang was–a unique mixture of stylistic flamboyance and swift economy. You see that mix in silent masterpieces like the Mabuse films, Metropolis, The Niebelungen, and Spione. In various entries (here and here and here) I’ve dwelt on his poised, meticulous compositions that use the entire frame area. Sound gave him a new set of resources for dynamic expression. Rather than becoming more conventional, Lang’s American films seem to subtly absorb the discoveries of M. Examples are the tapping of the “blind” man’s cane in Ministry of Fear and the ominously croaking frogs in You Only Live Once. And the propulsive sound cuts in his last film, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, show that he never forgot that sound could be edited as freely as images.

You can sample a clip from the episode at On the Channel at Criterion’s site. A complete list of the Observations on Film Art series (eleven already!) is here. Go here for blog entries offering background on those installments.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their teammates at Criterion.

Books not so briefly noted

“What a piece of junk!” Star Wars: Episode IV–A New Hope.

DB here:

Over there, across the room, a stack of more or less recently published books has haunted me for months. I wanted to tell you about them. True, I had plenty of excuses: My stay in Washington, a health nuisance, our trip to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, and our looming deadline for a new edition of Film History: An Introduction. But excuses aren’t necessarily good reasons. My delay was especially painful because the books were by friends.

So here’s some penance. As usual, some of the books I’ve read completely; others I’ve read only stretches of. But each is on a fascinating subject, by people of sound mind and impeccable character–in other words, exceptional researchers, thinkers, and writers.

Christine N. (Noll) Brinckmann is both a critic and a filmmaker. In Color and Empathy, she brings hands-on expertise to two subjects too often ignored. Her essays treat the handling of color in silent cinema, 1950s Hollywood, experimental film, and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. On the empathy side, she analyzes its role in documentary, Hitchcock films, and Eric de Kuyper’s Casta Diva.

Christine N. (Noll) Brinckmann is both a critic and a filmmaker. In Color and Empathy, she brings hands-on expertise to two subjects too often ignored. Her essays treat the handling of color in silent cinema, 1950s Hollywood, experimental film, and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. On the empathy side, she analyzes its role in documentary, Hitchcock films, and Eric de Kuyper’s Casta Diva.

Noll is very good on what I’d call the “historical poetics” of color, starting from perceptual and technical aspects and moving to the ways conventions emerged historically. For example, she contrasts Pal Joey and Chungking Express: sharp-edged versus blurred, object colors versus ambient colors, narratively motivated color clusters versus poetic and associational ones. She introduces the useful concept of color “chords,” mingled hues that create motifs that weave through the film. With this concept she’s able to treat late 1950s Hollywood color comedies as having a “mannerist” style, with chords dissolving into moments of patches of pure abstraction. She finds this strategy in some very unexpected places; I never thought I’d need to look at Bob Hope’s Bachelor in Paradise again, but now it’s a must.

As a filmmaker, Noll is also sensitive to the bodily reactions of viewers. Empathy is one such general phenomenon. What I appreciated in her discussion was her eagerness to go beyond the usual sense of the term, which involves feeling for characters in an emotional register. By analyzing passages in Secret Agent and Frenzy, she also considers how visceral factors like motor mimicry play into our responses. She takes the face as the main arena of empathy, but gestures–like cracking open fingers closed in death–are central as well. Thanks to empathy, she notes, films align us with some fairly unpleasant people. “We have not invested any sympathy in the characters; we disapprove of their actions, yet wish them to succeed.”

As a filmmaker, Noll understands that films are made not with themes but with images and sounds, so her account of bodily engagement, like her analyses of color dynamics, is pervaded by the recognition that first of all a movie is a concrete experience engaging our senses and our minds. The critic can point to abstract meanings, but we’re also interested in the mechanics underlying those meanings, how movies arouse our appetites for action and emotion.

Two critics attuned to the many levels of a film’s appeals are represented in new collections. There’s now a second edition of Roger Ebert‘s Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, from the University of Chicago Press. The 2006 original, which contained his personal choice of his strongest reviews and essays through 2005, has been enhanced with new pieces on Roger’s favorite films from the years 2006-2012, the year before his death. Films covered are Pan’s Labyrinth, Juno, The Social Network, A Separation, and Argo, along with shorter notices on many more.

It’s clear that Roger’s abilities were undiminished despite his illness. As ever, he brings his own variety of empathy to the characters and story worlds displayed. His eye stayed sharp:”Del Toro moves between many of these scenes with a moving foreground wipe–an area of darkness, or a wall, or a tree. . .. The technique insists that his two worlds are not intercut, but live in edges of the same frame.” The dozens of pieces in the collection are full of warm, sensitive moments of appreciation. I have updated my introduction to add some further reflections on Roger’s legacy.

While Roger Ebert was starting his career in Chicago with a review of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967, Joseph McBride was at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, writing his own film criticism and working on his still valuable book on Orson Welles. A prodigy, yes. He moved to California the same year Kristin and I came to Wisconsin; we met him once, as I remember, just before he was about to leave. We’re kindred spirits, born sixteen days apart and bound by Boomer Auteurism.

Joe’s most famous screenplay is for Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, but he also scripted many of the AFI tributes. He’s a professional journalist and currently a university professor. But he is at bottom, as he readily admits, a book writer. His biographies of Capra, Spielberg, and Ford have become indispensable, while his memoir and analysis of Welles’ late career (What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?) is just as meticulously researched and intellectually ambitious.

Now Joe has given us a massive collection of his shorter pieces. Two Cheers for Hollywood, its ambivalent title echoing E. M. Forster’s Two Cheers for Democracy, includes a vast panorama of work. Journalist Joe, who has done over 15,000 interviews in his career, gives us a tempting sample here. He records encounters with screenwriters (Polonsky, Michael Wilson, Marguerite Roberts et al.) and directors (from Cukor and Wilder to Bernds, of Three Stooges fame). He talks with Stepin Fetchit in a Madison strip club and Peter O’Toole in the Beverly Wilshire (“his bony white hands and feet protruding from his royal purple robe like the wings of a great pale bird”). Saul Zaentz complains of “pseudo-stars” and Billy Wilder shows Walter Matthau how to rip out a phone cord in two jerks: “Zis is the first one, and the second zis is a ZUMP!” Each interview is prefaced by a thoughtful reflection on Joe’s own evolution as a writer.

Then there are the critical pieces, many of them magnificent. There’s the most detailed defense I’ve ever seen of the Coens, a nuanced investigation of Ford’s attitudes on race, a predictably acute account of Spielberg’s strengths and weaknesses, an appreciation of performance in Fahrenheit 451, a probing of Wild River (Kazan’s most Fordian film, methinks), and much, much more. The book contains 56 essays, all substantial. It runs to over 650 big pages. It lacks neither passion nor precision, just an index.

Another Boomer Auteurist is William Paul. Bill did some film reviewing in his younger days but became an academic like Noll and Joe and me. Currently Professor of Film and Media Studies at Washington University of St. Louis, he has written fine books on Lubitsch’s American films and on the tie between modern horror and modern comedy. What has consumed him in recent years is an in-depth investigation of the history of the movie house. When Movies Were Theater: Architecture, Exhibition, and the Evolution of American Film is the result, and it’s a landmark study.

Another Boomer Auteurist is William Paul. Bill did some film reviewing in his younger days but became an academic like Noll and Joe and me. Currently Professor of Film and Media Studies at Washington University of St. Louis, he has written fine books on Lubitsch’s American films and on the tie between modern horror and modern comedy. What has consumed him in recent years is an in-depth investigation of the history of the movie house. When Movies Were Theater: Architecture, Exhibition, and the Evolution of American Film is the result, and it’s a landmark study.

The broad historical arc moves, as you’d expect, from storefront theaters to picture palaces and then drive-ins and arthouses. But this is no simple account of buildings. Bill argues that the manner of presentation shaped the rise of the feature film, the recurring strategy of roadshows, the demands for double bills, and other factors of film form and industry conduct.

Bill suggests that the 1910s demand for “life-size figures” in film might have been a response to theater size, and he speculates that the move to closer shots in the 1920s might reflect enlarging venues. Makes you wonder if “intensified continuity” of the 1960s and thereafter owes something not only to TV as the ultimate destination of the images but also to the cramped screens of early “twinned” houses, those sticky-floored abominations.

As usually happens when a good historian dives deep, you get surprises. Bill uncovers floor plans with seats facing in the wrong directions, horseshoe-shaped venues, auditoriums packed with pillars, and other peculiarities. One counterintuitive thing that I learned was that screens were rather small for most of film history. A screen for a palace seating a thousand people might be only twenty feet across. Bill’s frames from Footlight Parade and Saboteur show views from the back of a playhouse, and they indicate that often the proscenium area wasn’t filled by the screen, which was cloaked in black masking.

The Hitchcock is of course a studio reconstruction of Radio City Music Hall, but Bill indicates that the proportions are accurate. In all, his When Movies Were Theater joins Douglas Gomery’s Shared Pleasures in showing, in sharp detail, just how varied and diverse American movie exhibition has been.

I would recommend Steven Rybin‘s anthology The Cinema of Hal Hartley: Flirting with Formalism even if I didn’t have a piece in it. For one thing, I too flirt with formalism. Hell, I nearly eloped with it. Second, my study of staging in Simple Men is pretty bare-bones compared to the rich and varied work on display in the other essays in the book. Steve has written widely on American film, both classic and contemporary (Malick, Mann). His introduction to the book ranges across a vast terrain, from models of independent film to debates about “smart cinema.”

I would recommend Steven Rybin‘s anthology The Cinema of Hal Hartley: Flirting with Formalism even if I didn’t have a piece in it. For one thing, I too flirt with formalism. Hell, I nearly eloped with it. Second, my study of staging in Simple Men is pretty bare-bones compared to the rich and varied work on display in the other essays in the book. Steve has written widely on American film, both classic and contemporary (Malick, Mann). His introduction to the book ranges across a vast terrain, from models of independent film to debates about “smart cinema.”

The essays that follow offer agreeably intricate analyses of Hartley as a romantic comedy director, of “small films,” of Parker Posey as a muse, and on the Henry Fool trilogy as centered on the implications of writing. I especially appreciated the way that all the contributors (Mark L. Berrettini, Jason David Scott, Steven Rawle, Sebastian Manley, Daniel Varndell, Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni Berns, Zachary Tavlin, and Jennifer O’Meara) show how Hartley’s authorial obsessions responded to conditions of production, industry pressures, or critical reception. It’s called context, and yields a body of criticism that does honor to a director still not as fully appreciated as he deserves to be.

Another thick context, Wisconsin-revisionist style, is on display in Bradley Schauer‘s Escape Velocity: American Science Fiction Film, 1950-1982. In working on my book on 1940s cinema, I was struck by the absence of today’s dominant genres: fantasy and science fiction. SF books and magazines became widely popular in the period but, apart from cheap serials, the genre had a delayed arrival on movie screens. When it did arrive, Brad explains, it was presented not as classic space opera but something else, what he calls “topical exploitation cinema.”

To escape the pulp associations of Flash Gordon, SF movies traded on current scientific discoveries and headline items like flying saucers. As often happens, it took a marginal player to push a new cycle. Eagle-Lion’s Destination Moon (1950) caught the attention of big studios, which embarked on mid-budget items like When Worlds Collide and The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951). Brad traces the cycle’s urge for legitimacy through special effects, more sophisticated narratives, and even appeal to Scripture. These developments were shaped by broader changes in the American film industry, especially concerning budgets and program policy.

To escape the pulp associations of Flash Gordon, SF movies traded on current scientific discoveries and headline items like flying saucers. As often happens, it took a marginal player to push a new cycle. Eagle-Lion’s Destination Moon (1950) caught the attention of big studios, which embarked on mid-budget items like When Worlds Collide and The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951). Brad traces the cycle’s urge for legitimacy through special effects, more sophisticated narratives, and even appeal to Scripture. These developments were shaped by broader changes in the American film industry, especially concerning budgets and program policy.

After spelling out this early history, Brad takes us through familiar titles from 2001 to Star Wars: Episode IV–A New Hope, but always fleshing out the story with new information and ideas. He shows that Kubrick gave his film prestige through art-cinema style and storytelling, while Lucas’s film gained traction by treating space-opera formulas with earnestness and respect rather than camp condescension. Brad analyzes important SF films that are often forgotten, like Logan’s Run and Rollerball. His discussion of Alien and Planet of the Apes reminds us that the current incarnations of these franchises have strayed somewhat from their original entries.

Again, the historian unearths surprises. Given the revulsion of today’s intellectuals toward Star Wars, which gets blamed for ushering in the Big Dumb Movie, it’s worth remembering that nearly all the critics praised it. Under the rubric “Fun in Space,” Newsweek‘s reviewer noted: “I loved Star Wars and so will you, unless you’re. . . oh well, I hope you’re not.” That’s sort of the way I feel about these books.

Earlier book-dedicated blog entries are here.

Designing Woman (1957): “There are three pillows stacked on each side of the sofa, and as if by chance they take up the colors of the party: red, turquoise, bluish-purple. . . . The color chord of the party becomes an end in itself, and the composition obtains a playful intrinsic value” (Christine Brinckmann, Color and Empathy, p. 48).

Ladies at all levels

La cigarette (1919)

Kristin here:

Earlier this month Flicker Alley released another of its ambitious collections of historic films, Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology. The dual-format edition contains three discs DVDs and three Blu-ray discs. Its ambitions are reflected in part by the volume of material included (652 minutes) and in part by the range of its contents, from well-known classics to obscure titles.

The collection was one of the last projects curated and produced by the late David Shephard. As with many of Flicker Alley’s releases, it was a joint project with Film Preservation Associates (Blackhawk Films) and Lobster Films of Paris, working with several film archives. The films are arranged chronologically, with the earliest being Les chiens savants (1902), a music-hall dog act attributed to Alice Guy Blaché, and the latest Maya Deren’s classic experimental film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943).

The publicity for the collection emphasizes that “More women worked in film during its first two decades than at any time since” (from the slipcase text). I would be interested in how such a claim was arrived at. It seems unlikely to me, if only because the film industries of the major producing countries have grown enormously since the silent and early sound periods. Still, despite this claim, the notes in the accompanying booklet (written by Kate Saccone, Manager of the Women Film Pioneers Project) describe how the DVD/Blu-ray release “reclaims that stature of ‘woman director’ and celebrates it in all its glory.” (One film included, Discontent [1916], is listed as “by Lois Weber”; in this case she wrote the screenplay, which was directed by Allen Siegler.) Thus the program does not survey the range of filmmaking work women performed–but such a survey would be essentially impossible. The lack of detailed credits on early films makes it difficult to determine even the director of a given film.

The silent films

It is not really possible to discuss all the films, but I’ll mention some and link to earlier entries where we’ve discussed some of them.

Of the 25 titles on the three discs, fourteen are silent. Six of these give an overview of work of Blaché, with three French films and three made after her move to the US.

Lois Weber is represented by three films, starting with perhaps her best-known work, Suspense (1913). With its unusual angles (see above), elaborate split-screen phone conversations, and action shown in the rear-view mirror of a speeding car, this is one of those films you show people to demonstrate how wonderfully inventive directors around the world became in that incredible year. I am also very fond of her feature, The Blot (1921).

The third Weber film, Discontent (1916), may surprise those familiar with her socially conscious features. In the mid-1910s Weber worked in a variety of genres. While David was doing research recently at the Library of Congress, he watched some incomplete or deteriorated Weber films that haven’t been seen widely. He wrote about False Colors here and here. Discontent is a comedy with a moral. An elderly man is living in a home for retirees, but he envies his well-to-do family. Finally they invite him to live with them, and naturally everyone ends up annoyed by the situation–including the protagonist, who winds up returning to the home and his friends.

Mabel Normand apparently directed quite a number of her films for Mack Sennett, and Mabel’s Strange Predicament (1914) is one of them. Its cast also includes Charles Chaplin and was his third film to be released, although it was the second shot and the first one in which he wore a version of his Little Tramp costume. Not surprisingly, he steals every scene he’s in. Normand even plays second fiddle to him, with her character forced for a stretch of the action to hide under a bed, where she is barely visible while Chaplin performs some funny business in the same room. (The print seems to have been assembled from two different copies, the bulk of the film being in mediocre condition with the ending abruptly switching to a much clearer image.)

One curious item in the program is Madeline Brandeis’ The Star Prince (1918). According to her page on the Women Film Pioneer’s Project, Brandeis was a wealthy woman who made films, mainly centering around children, as a hobby. Some of these were apparently intended for educational use. The Star Prince, her first film, is clearly aimed at children. A few of its adult characters are played by young adults, while children play both children and adults. This becomes a bit disconcerting when we assume for a long time that the prince and princess are perhaps seven or eight, until they fall in love and become engaged.

Despite the amateur filmmaking, there are some attempts at superimpositions and other special effects to convey the fantasy, as well as an charmingly clumsy pixillation of a squirrel puppet, the position of which is changed far too much between exposures.

This is the sort of local production, made outside the mainstream industry, that so seldom survives, and it is a welcome balance to the more sophisticated works that make up the bulk of this collection.

Speaking of which, the next part of the program consists of two features by one of the best-known female directors, Germain Dulac. The first, La cigarette, appeared in 1919. It’s melodrama about an fifty-ish Egyptologist, who has just acquired the mummy of a young princess who was unfaithful to her older husband. The professor begins to imagine that he is suffering a similar fate when his young and beautiful wife (see top) begins spending time with an athletic young fellow.

I remember seeing this film nearly forty years ago and thinking it was pretty weak. Luckily I have seen many films from this era since and know better how to watch them. Seeing it again I liked it quite a bit. It’s beautifully shot and well acted, and its sympathetic depiction of the doubting husband and the clever and resourceful wife is more subtle, in my opinion, than that of the marriage in The Smiling Madame Beudet (which is also included in this set). I was glad to have a chance to see the film again and recognize it as being among Dulac’s best work.

The silent section of the program ends with Olga Preobrazhenskaia’s The Peasant Women of Ryazan (1927). The title emphasizes that Preobrazhenskaia’s film is set in a provincial area. Ryazan, the capitol, is about 120 miles southeast of Moscow, so it is not one of the far-flung regions of the USSR. Still, it would have been distant enough at the time to have its own distinctive culture. Peasant Women gives us plenty of local costumes and customs without giving the sense of this being ethnography first and narrative second. Exotic though it may seem to us, this would have been recent history to Russians when it first came out.

Although most synopses claim that the story runs from 1916 to 1918, it actually begins shortly before World War I, probably in 1914, as the heroine Anna marries Ivan in a lively wedding scene including a carriage ride for the bridal couple (below). Shortly thereafter news of the war comes, and Ivan reluctantly departs for to serve in it. Anna is left in the household of her lecherous father-in-law, who rapes and impregnates her. The war goes on and ends, with the Revolution taking place entirely off-screen.

The second woman of the title is Wassilissa, a tougher sort, who applies to convert a decaying local mansion (we are left to assume that it was confiscated in the wake of the Revolution). She is seen at the end as being the prototype of the new Soviet woman, though Preobrazhenskaia throughout avoids hitting us over the head with overt propaganda.

The sound films

Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the directors on the third disc, devoted to sound films, are likely to be more familiar to modern viewers. Nevertheless, Marie-Louise Iribe and her film Le Roi des Aulnes (1920), were completely unknown to me. She was the niece of designer Paul Iribe and worked primarily an actress during the 1920s, and this seems to have been her only solo directorial effort. (IMDb lists her as the co-director of the 1928 version of Hara-Kiri, which she also starred in.)

Le Roi des Aulnes is one of the musically based movies that were popular in the early sound era, being based on both Goethe’s and Schubert’s versions of “Der Erlkönig.” It’s nicely photographed, and the part of the father is played by Otto Gebühr, known for being trapped by his resemblance to Friederick der Grosse into playing that role time after time from 1921 to 1941. He’s predictably excellent here, though the stretching of the short poem into a 45-minute film forces him to register worry and eventually grief throughout. Indeed, despite extrapolated incidents, such as the injury of the father’s horse and the need to procure a new one, a great deal of repetition occurs: lots of riding through marshes and menacing appearances by the Erlkönig, who is portrayed as a large man in chain-mail.

The special effects are the most impressive thing about the film, using double superimpositions in widely different scales, with the giant king holding a small fairy on his palm.

Despite its problems, the film is a valuable addition to our examples of this mildly avant-garde trend that flourished for a short time.

Most of the rest of the directors are well-known and can be mentioned more briefly.

The great animator and innovator of silhouette animation Lotte Reiniger is represented by three short films: Harlequin (1931), The Stolen Heart (1934), and Papageno (1935). I have written about Reiniger’s complex compositions, including her subtly shaded backgrounds. Of the directors represented here, she is the one who enjoyed the longest career, from 1916, when she would have been 17, to 1980, when she was 81. I discuss a BFI boxed set of some of her 1950s films here. I haven’t been able to find a complete filmography, but William Moritz estimates that she made “nearly 70 films.”

Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker’s A Night on Bald Mountain is similarly familiar. Like Iribe’s Le Roi des Aulnes, it falls into the genre of illustrations of existing musical pieces, being an illustration of a piece of the same name by Modest Mussorgsky, as arranged by Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. It was created by manipulating hundreds of pins on a large frame called a pinboard, invented by Alexeieff, his first wife Alexandra Grinevsky-Alexeieff (whom he divorced in order to marry Parker in 1940), and Parker. The textured effect is quite unlike that of any other type of animation.

Dorothy Davenport was a prolific actress from 1910 to 1934. She is perhaps most remembered as the widow of Wallace Reid, a star who died from the effects of morphine in 1923. She directed seven films over the next decade, ending with the film in this set, The Woman Condemned (1934), mostly either uncredited or signing herself Mrs. Wallace Reid.

The Woman Condemned is a B picture, produced independently and distributed through the states’ rights system. It’s a competently done murder mystery that gains some interest by withholding a great deal of information from the audience. There are two main female characters, the victim and the accused (seen below in an interrogation scene), and we have very little idea of their motives and goals until the climax of the film. The revelations involve a twist on the same level of groan-worthiness as “and then she woke up.” But again, having a little-known B picture adds to the wide variety of films presented here.

One can hardly study early women directors and skip over the favored documentarist of the Third Reich, Leni Riefenstahl. Day of Freedom (1935) is a good choice for inclusion, occupying only 17 minutes of screen time and amply demonstrating Riefenstahl’s undeniable gift for creating gorgeous images from ominous subjects.

Experimental animator Mary Ellen Bute is represented by two contrasting abstract shorts, the lovely black-and-white ballet of shapes, Parabola (1937) and the vibrant and humorous Spook Sport (1939), the latter (below) made with the collaboration of Norman McLaren.

Dorothy Arzner, the only woman to direct mainstream Hollywood A films from the 1930s to the and 1940s, is introduced via a clip from one of her most famous films, Dance, Girl, Dance (1940). In the scene, Maureen O’Hara’s character interrupts her dance routine to tell off an audience of mostly men who are cat-calling her.

Maya Deren’s first film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) ends the program (see bottom). It is a happy choice, since of all the films in the program, it has undoubtedly had the greatest influence on the cinema. Much of the subsequent avant-garde cinema has turned away from music-inspired abstraction and opted for ambiguity, psychological mystery, and impossible time, space, and causality.

Valuable though this collection is, I cannot help but think that some of the directors represented have been oversold. Saccone sums them up:

Together, these 14 early women director have produced bodies of work that are inspiring, controversial, challenging, invigorating, and thought provoking. These women were technically and stylistically innovative, pushing narrative, aesthetic, and genre boundaries.

Surely not all of them meet these criteria. We would hardly expect one hundred per cent of the male directors of the same era to be “technically and stylistically innovative,” so why should we expect all of the work by fourteen varied female directors to be so? Saccone quotes Tami Williams’ book, Germaine Dulac: A Cinema of Sensations. on how the director searched “for new techniques that, in the light of official discourse of governmental and social conservatism, and the modernity of the new medium, were capable of expressing her progressive, antibourgeois, nonconformist, and feminist social vision.” Saccone sees this search in The Smiling Madame Beudet, where “Dulac utilizes cinema-specific techniques such as irises, slow motion, distortion, and superimposition, as well as associative editing, to give visibility to the inner experiences and fantasies of an unhappily married woman …”

Readers might infer that Dulac innovated these techniques. Yet they had already been established as conventions of French Impressionist cinema, notably in Abel Gance’s J’accuse (1919) and La roue (1922) and Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado (1921). For example, Dulac surely derived the distorted image of Beudet that conveys his wife’s disgust (below left) from a similar shot of a drunken man in El Dorado (right).

This is not to say Dulac isn’t a fine filmmaker or that she had no new ideas of her own. Only that she didn’t single-handed discover these techniques, but rather she turned the emerging repertoire of Impressionist techniques toward portraying a woman’s experience.

In some cases films that were co-directed by these women are presented as their sole efforts. Lois Weber’s Suspense was directed, as were many of her early shorts, with her husband, Phillips Smalley. Quotations from interviews with both Weber and Smalley make this clear. In 1914, Smalley said of his wife, “She is as much the director and even more the constructor of Rex pictures than I.” “Even more” because Weber often wrote the screenplays for their films and in at least some cases edited them. Weber later described how Smalley worked from her scripts: “Mr. Smalley got my idea. He painted the scenery, played the leading role and helped direct the cameraman.” Directing the cameraman is part of the job of a director.

The list of films in the booklet attributes Night on Bald Mountain entirely to Claire Parker, though on the backs of the disc cases the credit is to Claire Parker and Alexandre Alexeieff. Alexander Hackenschmied (aka Hammid) is not mentioned in the list of films, and the booklet refers to him as having a “close collaboration ” with Deren, even though he and Deren are both listed as directors on the original credits of Meshes of the Afternoon.

Still, if the collection does not make the case that all of the women represented were wildly talented and innovative, it does show the variety of ways in which women managed to work both in and out of the mainstream industry. It’s valuable collection of historical examples and should be welcomed by anyone interested in the silent and early sound eras.

It is worth noting in closing that viewers should not expect all of these films to be presented in the usual beautiful restorations we are used to from Flicker Alley. Some of these films are indeed gorgeous, including the two Mary Ellen Bute shorts, Peasant Women of Ryazan, Day of Freedom, Meshes of the Afternoon, and La cigarette (though the latter has some small stretches of severe nitrate decomposition). Other prints are quite good or at least acceptable. A few of the films simply do not survive in any but battered or faded prints, notably Discontent and The Star Prince. But we are lucky to have them at all.

The quotations from the Smalley and Weber interviews are from Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015), pp. 26-27.

[May 23] Many thanks to Manfred Polak, who has drawn my attention to a higher estimate of Reiniger’s lifetime production of silhouette films. Her friend and executor, Alfred Happ, put the figure at about 80. The source is an exhibition catalog from the Stadtmuseum Tübingen, which houses Reiniger’s archived material: Lotte Reiniger, Carl Koch, Jean Renoir. Szenen einer Freundschaft. Die gemeinsamen Filme. ed. Heiner Gassen and Claudine Pachnicke (Stadtmuseum Tübingen, 1994).

Carl Koch was Reiniger’s husband and collaborator; Reiniger created an animated sequence for her supporter and friend Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise. According to Manfred, “Alfred Happ and his wife Helga were Reiniger’s closest friends and caretakers in her last years in Dettenhausen (near Tübingen, Germany). After Reiniger’s death, Alfred Happ was the administrator of her estate. If you ever come to Tübingen, visit the Stadtmuseum (City Museum), where her estate is hosted now. A part of it is shown in a permanent exhibition.” He also provided a link to a touching account of Reiniger’s friendship with the Happs.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)