Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Retro-mania

The Gold of Naples (L’oro di Napoli, 1954).

DB here:

With the growing popularity of subscription streaming services, I suspect that film festivals will need to amp up their retrospective offerings. I was very surprised that a good film like I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, which would in earlier years have played arthouses, had no theatrical release. Despite its acclaim at Sundance, it went straight to Netflix online. True, Amazon has shown great willingness to port its high-profile titles to big screens. But by and large, as Netflix, Amazon, and other services produce and buy up new films, I suspect that festival premieres of indie titles will become more and more a display case for streaming. See it this week at our festival, and next month online!

It must be dispiriting for filmmakers hoping for theatrical play. Yet this crunch may oblige festival programmers to emphasize archival and studio restorations. These rarities are unlikely to show up on streaming any time soon, and festival screenings can build a public for them—so that they may eventually come to DVD or subscription services.

Case in point: Several restored titles at our Wisconsin Film Festival drew sellout crowds.

AMPAS comes through

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

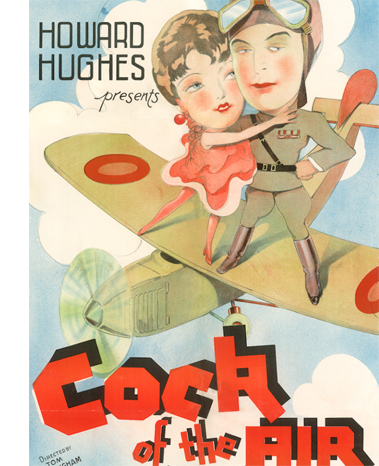

I did manage to squeeze into another Academy restoration, Howard Hughes’ Cock of the Air (1932). The film amply showcases Hughes’ two principal concerns, aviation and the female mammary glands. (I guess technically that makes three concerns.) It’s a minor-key Lubitsch switch in which priapic flyboy Chester Morris pursues sexy Billie Dove, who’s resolved to bring his ego crashing to earth. We get lots of nuzzling, murmured double entendres, and scenes of passion quickly doused by the woman’s coquettish withdrawal. I thought the plot thin, needing a romantic rival or two, but the leering pre-Code stuff is good dirty fun. The high point comes when Billie encases herself in a suit of armor and Chester arms himself with a can opener.

The direction is credited to Tom Buckingham, a lower-tier artisan, but it seems possible that parts of the film were handled by Lewis Milestone, who contributed the original story. The first couple of reels are very flashy, with odd angles, complicated tracking shots, and bursts of rhythmic editing. They’re typical of Milestone’s showy, sometimes showoffish, style in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and The Front Page (1931; also shown at WFF).

Cock of the Air encountered heavy censorship, with the can-opener episode entirely snipped from the release version. The Hays Office even provided local censor boards with guidance for further cutting. When Heather discovered a pre-censorship print at the Academy—an exciting find—she discovered that the offending footage was there, but the soundtrack portions were lost.

Heather proceeded to hire actors to voice the parts in accord with the script and the onscreen lip movements. The results are sonically smooth, but in the spirit of fair dealing, the bits of replacement are marked with a discreet bug in the lower right corner of the frame. This is a nice piece of archival integrity. Heather also showed an informative short on the restoration of this engaging piece of naughty early sound cinema.

Of incidents and non-incidents

The Incident (1967).

Two other pieces of film history got fitted into place with the revival of Larry Peerce’s One Potato, Two Potato (1964), a classic of American social-problem cinema, and the rarer The Incident (1967). This latter glimpse of mean streets creates what screenwriter David Koepp calls a Bottle, a tightly constrained space in which the drama plays out. Here the Bottle is a subway car in which several people, a cross-section of New York life, become the playthings of two young thugs, played by Tony Musante and Martin Sheen.

Starting by gay-bashing and culminating in a charged racial confrontation, the subway conflicts sought to show how the solid citizens can’t summon the will to respond collectively—even when they take their turn under the thugs’ lash. It was intended as a response to the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese, whose screams were mostly ignored by her Queens neighbors. (A recent documentary, The Witness, revisits the case.)

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

A believer in improvisation, Peerce rehearsed different groups of actors separately, then brought them together to let some natural friction emerge. He encouraged them to add to the script and build immediate reactions—so immediate that Thelma Ritter, a veteran unused to improv methods, responded to Musante’s goadings by slapping him. All this is captured in a superheated style of fast cuts, big close-ups, and screeching sound. It’s a white-knuckle ride that retains its power. I hadn’t seen it since 1970, but the violent climax, utterly earned, is disturbingly contemporary. The film’s final moments are being replayed, in reality, all over America as you read this.

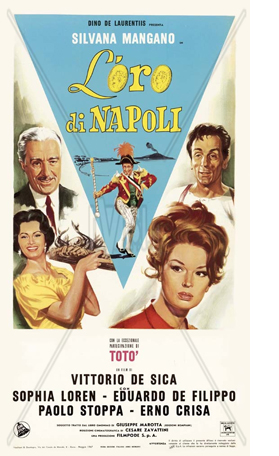

The nicest surprise of my retrospective viewing was The Gold of Naples (1954). Studded with big names (Ponti and De Laurentiis, Totó and de Sica, Silvana Mangano and Sophia Loren), it has sometimes been thought to be one of those lightweight Italian comedies that represent a quiet refusal of the Neorealist impulse. On the contrary, it proves to be a bold contribution to block construction, here in the omnibus genre. Several stories are laid end to end, exemplifying the vivacity and poignancy of life in Naples’ back alleys.

One story has a tight, shocking arc: the tale of a prostitute (Mangano) who thinks she’s marrying for love until she learns her new husband’s guilt-ridden sadomasochistic motives. The finale is a scrappy anecdote, in which The People give a local plutocrat the ultimate vocalization of disrespect.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

Above all, in an episode cut from the original American release (and missing from this poster, though at the top of today’s entry), a mother follows her son’s coffin driven through the street. She throws wrapped candies for children to pick up. That’s it. No flashbacks to life with her boy, no dialogue telling us how he died, no colorful secondary characters to provide that life-goes-on final note. It could be called “The Incident,” though nothing more unlike the fever-pitch drama of Larry Peerce’s film could be imagined.

According to screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, a Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

The lack of a dramatic peak, to which a normal scene would build, can force our attention to downshift to the minutiae of moment-by-moment action, or rather micro-action. That’s what happens in this sequence of The Gold of Naples, which Zavattini helped write. Every gesture and glance becomes potentially, but ambiguously, significant. De Sica’s patient recording of a very thin slice of life is as radiantly unpretentious a model of “pure Neorealism” as anything to come from the 1940s.

This is just a glimpse of the delights among the 150 screenings that are gracing our eight-day film festival. (We’re now the largest university-sponsored festival in the country, though probably not in budget.) Details of this magnificently programmed affair are here. We’ll blog again soon.

Thanks to the programmers Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King, along with all the institutions, wise elders, community supporters, and volunteers that make WFF fun. You can browse earlier reportage from this event here.

You can also see the restored Front Page (1931) in Criterion’s new His Girl Friday DVD release. On Cock of the Air’s censorship travails, see the AFI site. It will be screened very soon at the TCM Festival. Also set for the TCM festival is The Incident, which will screen later in April at Film Forum. Mike Mashon gives more information on Aloha Wanderwell in his LoC blog.

How wrong I was to miss booking The Gold of Naples when I ran a film club in college and good old Audio-Brandon offered it. Even without the funeral scene and the up-yours finale, it would be worth seeing. Now no version seems available in the US; WFF director Jim Healy brought a print from Italy. It would be perfect for FilmStruck.

Read…watch movie…grab food…read…watch movie…

Some things not yet spilled on the blog

The Film Style Mafia, Studio Babelsberg, November 2012.

DB here:

Malte Hagener, professor at the University of Marburg, was my host four years ago when I visited the dynamic research group Filmstil (aka The Film Style Mafia) at the Konrad Wolf Film University. I had a very enjoyable and informative time; the papers and discussions were excellent. Here’s my account of my visit, along with side trips to the Filmmuseum Potsdam and Studio Babelsberg.

A few days ago, Malte published an interview he conducted with me on email. It’s in NECSUS, the English-language journal of European Film Studies. Regular readers of this blog might be interested in its take on my academic work in film history and analysis. It discusses some things that we haven’t broached hereabouts, as far as I remember. At least it has a provocative title!

Many thanks to Malte and his colleagues for their efforts.

Konrad Wolf Film University, November 2012.

Silents nights: Stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings, the sequel

Kristin here:

A welcome translation, long awaited

From 1991 to 2003, the University of Wisconsin Press published an even dozen books of cinema history in the series Wisconsin Studies in Film. The editorial board consisted of David Bordwell, Donald Crafton, and Vance Kepley, with me as supervising editor. In a little over a decade, we accomplished our simple goal of fostering excellent historical studies in an era when it was far less easy to get such books published than it is now.

Among the dozen was Film Essays and Criticism, a volume of previously untranslated reviews and essays by Rudolf Arnheim (1997). That volume was made possible by the dedication of Brenda Benthien, its translator. Now Brenda has pursued a project she and I discussed long ago. She has brought to fruition a translation of the important classic book, Rudolf Kurtz’s 1926 Expressionismus und Film.

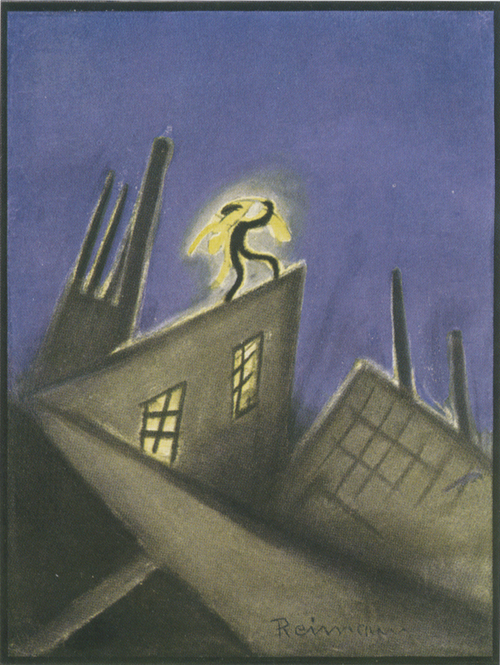

Kurtz’s book has been important enough to warrant two reprint editions in German, one in 1965 by Verlag Hans Rohr, with the illustrations all in black and white and the original cover painting by Paul Leni not used, and another in 2007 by Taschen, edited and with a lengthy essay by Christian Kiening and Ulrich Johannes Beil, as well as the original color illustrations and cover. The English translation, published earlier this year by John Libbey, essentially replicates the 2007 edition, including the cover design and the Kiening/Beil essay. The color illustrations, such as the frontispiece, a design by Walter Reimann for Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (top), are also reproduced.

Kiening and Beil are listed as editors here as well. As they point out in their brief introduction to the English edition, there had already been translations into French and Italian, but without the illustrations. Our English version may be late, but it comes much closer to replicating Kurtz’s original.

Kurtz’s title sums up his approach. He defines Expressionism in relation to the other arts of the era, particularly painting and theatre, and discusses the style of six films. Of these, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Waxworks are familiar; From Morn to Midnight, Genuine, and Raskolnikow less so; and The House on the Moon is still, as far as I know, completely lost. (An excellent DVD of Von Morgens bis Mitternacht is available from the FilmMuseum via the link. The Alpha editions of Genuine and Raskonikow are, by report, American cut-down versions with poor visuals.)

One benefit of consulting the original or Benthien’s translation is to reveal that Siegfried Kracauer distorted the famous quotation from designer Hermann Warm that he includes in From Caligari to Hitler: “Films must be drawings brought to life” (p. 68). The original, “Das Filmbild muss Graphik werden” (p. 66 of Expressionismus und Film) is more accurately rendered by Benthien as “The filmed image must become graphic art” (p. 68). “Graphic art,” after all, includes far more than drawings.

The Kiening and Beil essay mentioned above is included in the translation. It is a substantial piece, taking up 75 pages of the book’s total of 214. The authors explain Kurtz’s background in the art world and film industry of the era, as well as discussing conceptions of Expressionism in the years leading up to the release of Caligari. They cite many contemporary theorists’ and critics’s views of of Expressionism in the cinema. Kiening and Beil flesh out Kurtz’s work by pointing out several Expressionist or semi-Expressionist films that Kurtz doesn’t mention. They explain how From Caligari to Hitler and (slightly later) Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen became popular as explications of Expressionist cinema, leaving Kurtz in relative obscurity until recent decades. In short, the essay, entitled simply “Afterword,” is an erudite and invaluable addition to this edition of Kurtz’s book.

Cinematic after all

Way back in 1969, when I was taking my first film class, I saw The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and became fascinated with German silent cinema, especially the Expressionist movement. I still retain a surprising willingness to sit through German films of the era–even mediocre ones–with their slow pace and heavy acting. Back in those early days, I tried to see the German classics, many of which were available in poor 8mm and 16mm copies.

I vaguely remember being disappointed by my first viewing of The Student of Prague. At the time of that viewing, film studies were still in their early days, and just about everyone assumed that a film was “cinematic” if it had quite a bit of editing and camera movement. The Student of Prague, like many films of its era, was short on both. Its long-take opening shot, with no cut-ins or tracking camera, seemed the epitome of stagy cinema.

I don’t know which version of the film I saw, but it wasn’t the original 1913 one. The film has a complicated history of re-editing and re-release, both theatrically and for home video. This history is recounted in the booklet accompanying the Munich Filmmuseum’s new DVD release of a reconstructed version approximating the 1913 release print, as well as the much shorter American release print. The original version was sold to a producer, Robert Glombeck, who exploited the occasion of the 1926 remake to release the original, highly reworked, including the addition of 107 intertitles. (The original had deliberately been made using a minimal number of intertitles.) Although shortened American and Japanese release prints of the 1913 version survived, the original German one did not.

The new reconstruction has been made from the Glombeck negative, as well as the other release prints, a script, and the incomplete censor’s record. While it cannot claim to be an exact replica of the original, it is far closer than we have had up to now. The excessive intertitles have been removed and a prologue shot showing scriptwriter Hanns Heinz Ewers and lead actor Paul Wegener looking up at Prague Castle restored. (It survived only in the American print.)

Even before this new release, I had gained a far greater respect for this supposedly uncinematic film. My first viewing came before academic interest in early film blossomed with events like The Brighton Project in 1978, trends like the spread of film archives and the rediscovery of many lost prints, and a general recognition of the historical, entertainment, and aesthetic value of early films, even among the general public. Gradually historians had realized that editing and camera movement were not the only techniques that exploited the techniques of the medium. There were long takes and intricate staging. There was the compositional exploitation of depth and the surprises of offscreen space. During the period 1992 to 1998, Yuri Tsivian, Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster, David, and I explored various techniques that cinema of the 1910s used for expressive purposes. (See the codicil for citations.)

In 1993 I gave a keynote address at the fifteenth IAMHIST conference, “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity, 1913-1919,” at the University of Amsterdam. In it I discussed a wide range techniques of framing, staging, acting, and unusual editing that were innovated in films made in many countries, all tending to enhance expressivity. Among my examples was that opening scene of The Student of Prague. I said, “This seems to me a case that could be dismissed as primitive. Yet it could also be described as a complexly staged scene that sets up the basic narrative situation and uses depth and unexpected appearances from off-screen to heighten the impact of the action.”

Now that we have something approximating the original version, we can look again at that first shot. There are two presentations of the reconstruction in this set, one with a piano rendition of the original score, which survives only in a printed piano score, and one with an orchestration of that score. The piano version runs distinctly shorter, and it looks to be projected at about the right rate. In this presentation, the first shot runs 3 minutes 40 seconds. It contains only two intertitles. After an establishing shot of a beer-garden, our hero enters, and the students hail him as the best fencer among them. This is information that we could only learn through speech. The title also provides his name, Balduin.

He sits glumly, largely ignoring the action behind him as Lydushka (apparently secretly in love with Balduin) enters and the students lift her onto a table for a dance. As this ends, a coach suddenly drives in from the left, and as it blocks most of the background, the students swiftly exit.

Scapinelli gets out of the coach and joins Balduin, tapping him slyly on the shoulder as Lydushka watches, growing anxious as the two start a conversation. The second intertitle provides crucial plot information, as Balduin announces that he is ruined and needs either a winning lottery ticket or a rich heiress. Scapinelli leads him out, the camera reframing slightly with them and with Lydusha, who moves forward to watch them. Soon Scapinelli will appear in Balduin’s room and make the fateful bargain, providing riches and the heiress in exchange for his mirror image.

There is nothing quite like this shot in the rest of the film, but there are some very impressive depth shots. These typically involve a character in the foreground or background looking at other characters. Such shots substitute for eyeline-match cutting, which was not yet a convention of German cinema. In the shot at the bottom of this entry, Lydushka spies on a romantic scene between Balduin and Countess Margit. Below, Balduin realizes that his Doppelganger has killed Margit’s fiancé in a duel, thereby disgracing him.

And there are, of course, the extraordinary shots of Balduin together with his Doppelgänger , achieved by the great German cinematographer, Guido Seeber. When the double, on the right, confronts the lovers in the old Jewish cemetery, the careful staging and double exposure allow Balduin to cross behind the large tombstone and enter the space where his nemesis has been moments before (see the top of this section).

Apart from the different versions of The Student of Prague, the DVD set contains a 1913 short, Die ideale Gattin (“The Ideal Wife”), also “made by” Hanns Heinz Ewers. (The edition treats Ewers as the main creator of The Student of Prague, though most sources credit Stellan Rye as the director. It is true that at the time the scriptwriter was considered the creator of a film, but there’s no clarification of this in the notes.)

This is a charming little comedy starring Paul Biensfeldt as the hero oppressed by his strict, humorless female relatives and in search of a perpetually-smiling wife. Biensfeldt is a familiar face if not name, having played roles in several of Lubitsch’s German features, such as Menon in Das Weib des Pharao. Lubitsch himself plays a small role here, appearing as the matchmaker in only one scene. He is unrecognizable under a wig and beard and has nothing little to do.

The DVDs can be ordered directly from the Edition Filmmuseum shop. I note that Filmmuseum editions are now being sold on Amazon.de as well.

No buffalo were harmed in the making of this film

In March we praised the rescue of a major documentary, Strange Victory, released by Amy Heller and Dennis Doros’ Milestone Film & Video. The company has since brought out a film long thought to be lost, The Daughter of Dawn, one of a handful of fiction features from the decade that used casts entirely made up of Native Americans. (Notable others are Hiawatha [1913], In the Land of the Headhunters [1914], The Vanishing Race [1917], and Before the White Man Came [1920].)

As often happens in such cases, the director of The Daughter of Dawn, Norbert A. Myles, was a white man. He had started as an actor in 1913, directed three features in the 1920s, and went on to a long career working as a makeup artist (usually uncredited) on many of the most famous films of the 1930s and 1940s–most notably Ray Bolger’s makeup as the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz.

And as also often happens, the scenario avoids analyzing the culture of the ethnic group in question. The film largely falls back on a very conventional central premise. The film centers around a love rectangle, with the heroine, a Kiowa chief’s daughter nicknamed Daughter of Dawn, in love with the stalwart hunter White Eagle. Black Wolf, a rich brave seeking to become the new chief, spurns the devoted Red Wing and seeks permission to marry Daughter of the Dawn.

There are some action scenes, notably a chase after a herd of buffalo early on. We don’t see any actual killing of buffalo, and although the hunters return to their village announcing success, there is no glimpse of carcasses. Whether this was due to budgetary factors or legal or safety restrictions is unclear. A later battle scene between the Kiowas and some raiding Comanches is more successful. Myles wisely keeps his camera at a distance from most of the action, which creates a sense of genuine combat, unlike the effect of fake-looking close shots of two actors struggling hand to hand.

Still, most of the scenes are devoted to the romance plot, which is rather a pity.

The attraction of the film, though, is its authenticity. Not only did hundreds of Kiowas and Comanches perform for the camera, but they brought their own tipis, costumes, and accessories. They were by this point living on reservations but not so long that they had lost touch with their traditions. The period when the action is set is never specified, but there is no sign of white encroachment, no visible roads, and no mention of the threat of westward-moving pioneers or military. It is as close a look into this vanished past as we are ever likely to have. The Native Americans seem to have been happy to display their heirlooms for the camera, as in this scene where the heroine converses with her father in their tipi.

The performances of most of the cast are predictably rather stiff, with most of them primarily standing or moving where told to by the director. Dialogue titles rather than pantomime handle most of the story information. Myles successfully cast two more natural performers for his leads. Esther Le Barre and White Parker were Comanches (the tribe cast as the villains in the story) but played Kiowas, no doubt because they were both expressive and attractive–though to the filmmakers’ credit, they made no attempt to glamorize the pair.

In short, The Daughter of Dawn is an extraordinary historical document. For more information on the film’s making, rediscovery, and modern release, see the site of the institution that found the surviving print, the Oklahoma Historical Society. Its museum, by the way, has on display the historic tipi used in the film as the heroine’s dwelling. In 2013, after the film was preserved, the Library of Congress added it to the National Film Registry.

I discuss The Student of Prague‘s seminal role in establishing fantasy and horror as key genres that would remain important and culminate in the Expressionist films in “Im Amfang war … : Some Links between Germany Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli, eds. (Edizioni Biblioteca dell’Immagine, 1990): 138-148.

Yuri Tsivian concentrated on the introduction of mirrors into 1910s cinema to create a new way, nontheatrical way of presenting space to the spectator. See his “Portraits, Mirrors, Death: On Some Decadent Clichés in Early Russian Films,” Iris nos. 14-15 (Autumn 1992): 67-83. My 1993 keynote address quoted above was published as “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, eds. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995): 65-85. Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs focused on acting and staging in dept in their Theatre to Cinema (Oxford University Press, 1998). The revised edition is available online.

David began discussing tableau staging and compositions in depth in Chapter 6 of his On the History Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997) and continued the exploration in the Feuillade chapter of Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging (University of California Press, 2005). For entries relevant to German Expressionism, check our Ten Best lists and our entries on Homunculus, on Sappho and others, on INRI and others, and on Murnau before Nosferatu.

[November 22: Brenda informs me that she also did the intertitles for FilmMuseum DVD of The Student of Prague.]

The Student of Prague.

Reeling and dealing: Rescuing movies, by hook or by crook

DB here:

There have long been film collectors, and they’re central to film preservation. Some archives, notably the Cinémathèque Française and George Eastman House, were built on the private hoardings of passionate cinephiles. Filmmaking companies, both American and overseas, had little concern for saving their films until home video showed that there was perpetual life in their libraries. By then, many classics had been dumped, burned, or left to rot, and in many cases collectors came to the rescue.

In America, private collecting really took off after World War II. What happened afterward is too little known among cinephiles, but it represents an important part of film culture. A new book fills in a lot of the detail, and in a very entertaining way. It’s a big contribution to our knowledge of the afterlife of the movies.

16 + 35 = $$$$

In the late 1940s, 16mm versions of theatrical releases became widely available. For a while the studios contemplated replacing 3 5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

Many of those firms dealt in foreign titles, which weren’t as attractive to most collectors—who were in love with Gollywood. For them, the floodgates had already opened when the studios licensed their pre-1948 product to television. The 1950s and 1960s were very unlike the multi-channel 24/7 TV environment of today. The networks didn’t fill the broadcast day, and many independent stations tried to support themselves apart from the nets. So everybody needed what we now call content. Our colleague Eric Hoyt has traced in detail how C & C Movietime and other entrepreneurs bought rights to classics and not-so-classics and packaged them in 16mm bundles for local TV stations. Those prints were shown throughout the day and night, interspersed with commercials cut in by staff like Barry C. Allen.

In the 1950s hundreds of copies of film classics were abroad in the land. But many of these TV prints wound up discarded and scavenged by guys (almost always guys) who wanted to show them at home. Aficionados started building their own libraries.

Collecting 35 was tougher, but it could be done. Older films were stored in labs and depots. They might wind up in Dumpsters or be smuggled out by enterprising employees. Of course showing 35 was more difficult, but it wasn’t impossible to get 35 projectors fairly cheap, and if the hobbyist was willing to make major home renovations, he (again, almost always a he) could set up a personal screening room. Some went with curtains, masking, auditorium seats, popcorn machines, and other amenities. The idea of “home theatres” for ordinary folks has its origin here.

Acquiring 16mm was gray-market but ultimately not very criminal. Because of the First Sale Doctrine, a collector was not in violation if he bought a 16 print that had already been sold (to a TV station). If I buy the new Carl Hiaasen novel Razor Girl, I can sell my copy to you because someone sold it to me. What got 16mm dealers in real trouble was their zeal to copy prints. If they got access to a nice 35, they might make a 16 reduction; or if they had a decent 16, they might pull dupes. These were definitely illegal, as if I were to scan Razor Girl and sell you a pdf.

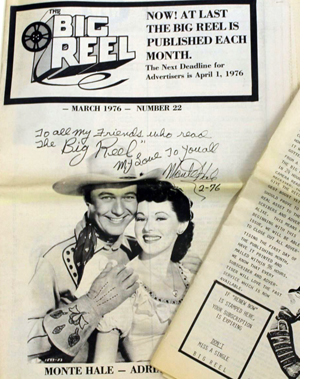

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

With some exceptions, 35 prints weren’t originally sold, only rented, and so possession of one suggested, to suspicious minds, big-time theft. Actually, most collectors’ prints had been junked, and you can argue that once something is tossed out, it’s the American Way to scavenge and recycle it.

Beyond the domestic collectors’ market, there was money to be made with 35 prints. American films didn’t circulate much in Cuba, South Africa, parts of Asia, and Eastern Europe, so there was an international demand for bootleg copies, and some dealers were happy to meet it. I lost out on a collection of Hong Kong films that was bought by an Indian dealer who intended to circulate them at home. I always think of that episode when I see the almost inevitable kung-fu fight in an Indian action movie.

The sale of 35 boomed because of another factor. With the rise of the blockbuster mentality in 1970s-1980s Hollywood, the nation was awash in theatrical prints. Then as now, a film might open on thousands of multiplex screens, play a few weeks, and be done. The studio would keep a few of those prints, but the rest would have to be disposed of. Salvage companies were contracted to destroy them, but—human nature being what it is—often some copies slipped out and into eager hands.

Films stored in laboratories or warehouses had a habit of disappearing as well, and prints shipped to theatres might be waylaid. I remember booking Blue Velvet and learning that the copy had disappeared in transit. The fact that prints were labeled with their titles printed in large letters probably didn’t help keep them safe. I was always startled to see the casual ways in which prints were handled. On Thursday midnights I’d leave a screening at one local theatre and see, neatly lined up on the sidewalk, shipping cases bearing the titles of films that had played there in recent weeks, waiting for a UPS pickup the next morning. After a theatrical run, exhibitors cared as little for prints as producers and distributors did.

Many collectors favored older titles, but others were as susceptible to blockbuster mania as general audiences. Star Wars, Jaws, The Godfather, and all the other top hits became as sought-after as Casablanca and Snow White. Collectors still boast of having multitrack, IB-Tech copies of 1970s and 1980s franchise pictures.

Enter the Feds

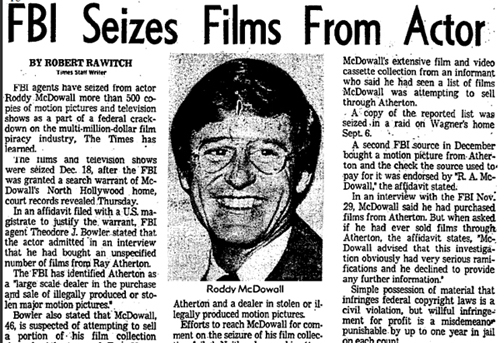

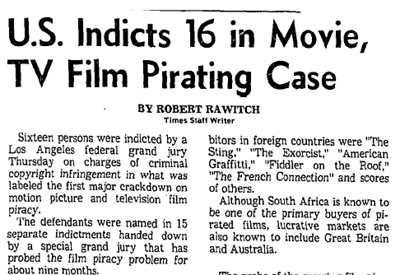

Los Angeles Times (17 January 1975), B1.

I’ve moved from describing the collectors’ market to describing the dealers’ market. That’s because they were almost one and the same. Collectors needed dealers to help find the rarities they yearned for; collectors started to deal to support their habit; and dealers, whether collectors or not, found that they could make money acquiring and selling movies. Demand and supply, in solid capitalist fashion, created an underworld traffic in prints.

The studios didn’t take this lying down. With the aid of the FBI, they pursued collectors, pressuring them to snitch on their suppliers and fellow addicts. Former child star Roddy McDowall, an avid collector, was the most visible target of these maneuvers. I well remember the chill that passed through the collector community at the news of the Feds’ raid on his house, which turned up hundreds of prints and videos. McDowall, who could probably have won a legal case, gave up many of his contacts. Charges against him were dismissed, but the U.S. Attorney pursuing the case warned that the activities of film collectors (said to number 65,000) “could constitute serious violations of both state and federal law.”

Most collectors flew under the radar, though. Although McDowall’s collection was mostly 16mm, the studios turned a blind eye to 16mm collectors. Famously, William K. Everson helped studios uncover lost films (e.g., obscure Fords and Stroheims) and as payment received 16mm copies of his discoveries. Collectors like Bill, who accumulated several thousand prints, shared their libraries with archives and film schools; at NYU, Bill taught from his collection for many years.

Home video didn’t destroy this underworld right away. The first video systems were of such poor quality that they couldn’t compete with 16mm projection, let alone 35. However, as formats improved in the 1990s, more and more collectors turned to video. Why thread up a battered copy of an MGM musical when a pretty nice DVD could just be popped into your player? With the arrival of Blu-ray, which can look very impressive projected in theatrical conditions, 35 began to be seen as more and more a retro hobby. And your average hobbyist was discovering that he (still almost certainly a he) was aging. Or dying.

The studios mostly lost interest in film-based piracy, once video presented a threat on a much bigger scale. Duplicating VHS and laserdisc, always imperfect, was followed by the cloning of perfect copies of DVDs. Now, of course, the main arena is the Net, where film piracy via BitTorrent has exploded to a level the old-timers couldn’t imagine. Back in the 60s, there were very few film collectors. Now, thanks to digital convergence and massive hard drives, everybody is a film collector—not only he’s.

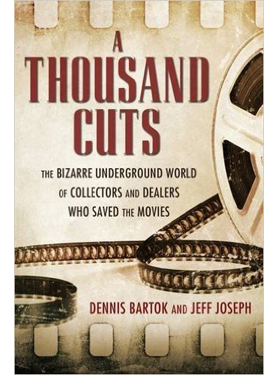

Boom and busts

This is the world chronicled, with affection, humor, gossipy detail, and a pang of melancholy, in Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph’s A Thousand Cuts. Dennis has been head of programming for the American Cinematheque, and he currently heads the distribution company Cinelicious Pics. Jeff was one of the top film dealers in the country; at its peak, his company SabuCat sold about 1,000 prints per month. In the wake of the McDowall bust, Jeff became the only film dealer to serve time for selling prints. Jeff is now a distinguished archivist, conserving 3-D prints and, most recently, rare Laurel and Hardy movies.

The book lives up to its subtitle: The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies. Through interviews, documents, and vast knowledge of the world of film dealing, Bartok and Joseph have given us an invaluable survey of a wondrous land. It’s as gripping, and sometimes as hallucinatory, as any Forties B noir.

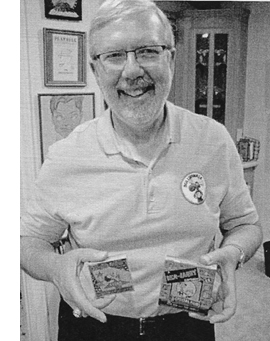

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Once we leave behind the celebrities, things take a more exotic turn. There’s Evan H. Foreman, the first collector targeted by the studios, a tough customer who fought for the right to sell prints and was called to testify before a Senate committee. There’s Ken Kramer, proprietor of The Clip Joint, a Burbank archive and screening facility decorated with posters and Christmas lights. There’s Tony Turano, who claimed for years that he was the baby in the bulrushes in The Ten Commandments. Tony kept his apartment heavily curtained, the better to preserve Claudette Colbert’s headdress and robe from Cleopatra (1934). Paul Rayton, projectionist extraordinaire, stores the cans for his rare Oklahoma! print in the back seat of his car. Not the film–it went vinegar long ago. Just the cans.

There’s Al Beardsley, uniformly considered untrustworthy, perhaps because he simply picked up a 70mm print of Lawrence of Arabia posing as a delivery courier and immediately sold it to a collector. Beardsley gave up film dealing for sports memorabilia, and became a participant in the O. J. Simpson throwdown in Vegas. As Beardsley recalls his encounter with one Thomas Riccio, who had set up the O. J. meet: “I had a drink and, I believe, a hamburger that Riccio paid for. He feeds you before he screws you.” O. J. was more direct: “Motherfucker, you think you can steal my shit and sell it?” Yes, firearms were involved.

This is as wild and crazy as any nerd culture can be. Like collectors of comic books and LPs, film mavens are clannish and wily, generous and secretive, boastful and yet somewhat innocent. These guys can’t be considered Geek Chic; they retain an unselfconscious love for what moved them in their youth. They live in the Adolescent Window, as we all do, but they don’t pretend to have become hip. And they run risks that other collectors don’t. A book or record collector runs no risk of arrest. But should a film collector offer a rarity to an archive? Will the studio claim it and bury it? Will the law get involved? Paranoia strikes deep, and justifiably.

Some of the tales are painfully funny, some just painful. This is the sort of book that contains sentences like:

The two were briefly partners as film dealers in the early 1970s, until Ken’s then-wife Lauren left him to marry Jeff, shortly after they were discovered having an affair at the 3rd Annual Witchcraft and Sorcery Convention.

Turano, wheelchair bound, had a habit of bursting into showtunes at the top of his voice. Tom Dunnahoo, of Thunderbird films, “routinely passed out on the floor of his film lab drunk on Drambuie.” A dealer takes pride in the fact that at his trial, the expert on the stand couldn’t tell his dupe of Paper Moon from the original. Another bit of dialogue:

“You remember I had a beet-red print of Giant? Well, Louie Federici ran it and borrowed a beautiful IB print of Giant. Afterward he sent it back to Warners, and you know what they got? A beet red print,” he says, face lighting up.

“You swapped it out?” Jeff asks.

“I did. And later I traded it to you for Singin’ in the Rain. How about that, huh?”

Nearly every page of my copy boasts my penciled ! in the margin.

Saving the movies

Jeff Joseph and Dennis Bartok, Cinecon 2016.

The book stresses that collectors functioned as preservationists. Just as in the early days of archives, they have saved films major and minor from destruction. Just last week, we learned that a collection of 9.5mm has added more footage to a partially surviving Ozu film, A Straightforward Boy. Famously, missing King Kong footage was discovered by a collector. . . and given, not sold, back to the studio. Tony Turano found a missing Fred Astaire number from Second Chorus in Hermes Pan’s closet. Jeff Joseph preserved color behind-the-scenes footage of Animal Crackers and found remarkable home-movie Kodachrome footage of Hitchcock, Bergman, and Grant out for a walk during the shooting of Notorious (surmounting today’s entry). Mike Hyatt has devoted his life to cleaning up The Day of the Triffids. Using a jeweler’s loupe and a needle, across many years, he flicked over 20,000 bits of dirt out of the camera negative.

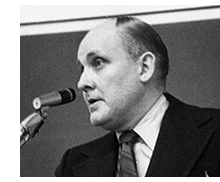

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Most of the stories in the book come from the West Coast, as you’d expect. Other regions have their own lore and characters. The East Coast was a lively scene, centering on Manhattan’s Theodore Huff Film Society (duly noted in A Thousand Cuts) and Bill Everson’s screenings at the New School and elsewhere. Scorsese is, of course, a famous collector. Until this last year hard-core fans of old films gathered at Syracuse’s fine Cinefest. The Midwest had its own center of film trade, Festival Films in Minneapolis, now a source of public-domain items. The screening-and-dealing gathering Cinevent, in Columbus, Ohio, is entering its 49th year.

There were colorful personalities hereabouts too, including a Milwaukee collector with a stupendous array of original Hitchcocks from the 1950s. Another Wisconsin collector, Al Dettlaff, discovered and jealously guarded Edison’s 1910 version of Frankenstein. I met a collector in remote Minnesota who had converted his garage for 35mm screening both indoors and outdoors. He could aim his projectors to shoot out onto the back yard for neighborhood shows (a popular pastime for collectors). During the snowbound winters, he could swivel the machines to shoot through the kitchen to the living room. I asked how his wife felt about sawing holes in the walls. He said: “She’s fine with it. She knows I can get a new wife a hell of a lot easier than an IB Tech of Bambi.”

Dennis and Jeff are to be thanked for recording precious information about a phase of American film culture that has been neglected. They’re continuing the effort with a clip show on 23 September at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre. It will include many items mentioned here, as well as a Bela Lugosi interview from 1931.

The collecting adventure is not quite over. The book profiles passionate younger aficionados, some of whom keep the energy going online. Still, as someone who has relinquished his passion for owning film on film and is happy that archives are taking over the task, I’m afraid it’s evident that the curtain is coming down. Without collectors, who will scavenge all the films not likely to be transferred to digital formats? The book ends with a list of six interviewees who died during writing and publication. And in the podcast below, Jeff glumly notes that studios are still junking prints.

Thanks to Jeff Joseph for illustrations. The Len Maltin picture is by Dennis Bartok. For a fascinating podcast that gives the authors a chance to expand on many aspects of A Thousand Cuts, check The Projection Booth. There’s a shorter streaming interview at KPCC radio.

Typical collector story: How did William K. Everson acquire his K? He told us that the first movie he remembered seeing was by William K. Howard, so Bill borrowed the middle initial. Another: We did our bit. After seeing an ad in The Big Reel for a hand-tinted Méliès print, we alerted Paolo Cherchi Usai, then at Eastman House. It turned out to be one of the lost Méliès titles.

Thanks to Haden Guest for tipping me to the Ozu rediscovery. I talk about how piracy created a classic here. For more on 16mm collecting and showing, go here and here. In this entry we cover Joe Dante’s remarkable visit to Madison and his presentation of The Movie Orgy, one result of his insatiable collecting appetites.

P.S. 14 September 2016: I should have mentioned another collector committed to preserving 3D films. Since 1980 Bob Furmanek has been building a large 3D archive, a project that is still ongoing. The history of his work is traced on his site.

P.S. 15 September 2016: Thanks to Christoph Michel for correcting a howler that out of shame I shall not name.

Animal Crackers, Multicolor on-set record (1930). Courtesy Jeff Joseph.