Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Oof! Out!

I Remember Mama (1948).

DB here:

Jim Naremore calls 1940s American studio cinema “the beating heart of Hollywood.” I think he’s right. For about five years I’ve been working on a book taking EKGs of that beating heart. The book tries to understand some factors that made Forties Hollywood so dynamic and continually captivating.

Doing this called my attention to so many things: the fresh subject matter, the variations in genres, the stylistic experiments, the superb performances, the quality of line-by-line writing. But I focused on something that’s still pretty big: new, or newly revived, storytelling methods. Those methods made that period exciting–not just in film noir, where we tend to think that narrative got pretty wild, but also in melodramas, rom-coms, musicals, and the rest.

It’s the only study I know of how narrative techniques emerged and developed in a single era. No wonder it took five years. I watched over 600 films. I trawled through books and trade papers for hints about what the producers, directors, and writers thought they were doing. And because a lot of techniques weren’t unique to film (e.g., flashbacks, first-person voice-over, etc.), I wound up reading forgotten plays and neglected novels, while listening to hours of old-time radio.

The project started when I was asked to do a series of lectures, “Dark Passages,” for Belgium’s Summer Film College in 2011. Just before that, I tried out some ideas in some spring blog entries. Things crystallized in 2013, when I firmed the project up. In this entry, I promised, falsely, that the book would be short.

Since then, I’ve been immersed in fun, except for the Red Skelton movies. I loved having Mercury Theatre playing in my car during drive-time, and digging out 1930s and 1940s books from the oldest section of our university library.

I think the book says some new things about films of the period, and about the development of American popular entertainment more generally. For one thing, I think I have a better understanding of how High Modernist techniques (out of Joyce, Woolf, etc.) made their way into mass art. (Not directly, I’m convinced.) For another, I have a new respect for those filmmakers who tried something daring, even if–see my last post on The Chase (1946)–they somewhat botched it. And it develops some ideas I floated in The Way Hollywood Tells It: ideas about how modern filmmakers like Tarantino and Nolan are continuing a Forties tradition of somewhat experimental narrative.

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling went off to the publisher this afternoon. Said publisher is the University of Chicago Press, who did a fine job with our Minding Movies and my recent little book The Rhapsodes, to which this is sort of a bigger, thuggier brother.

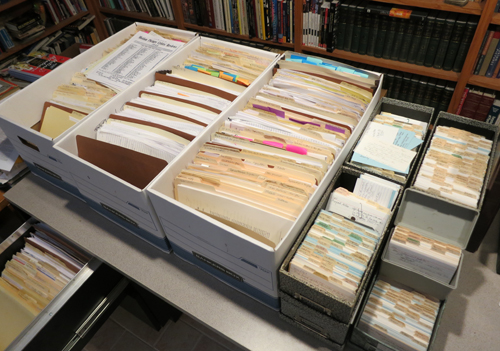

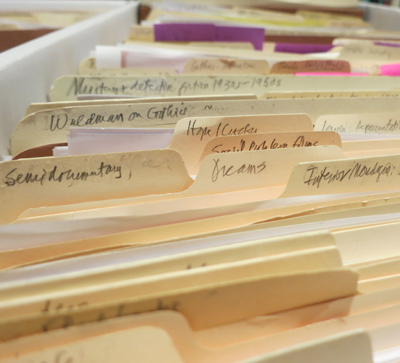

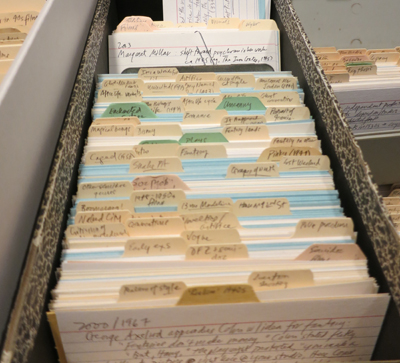

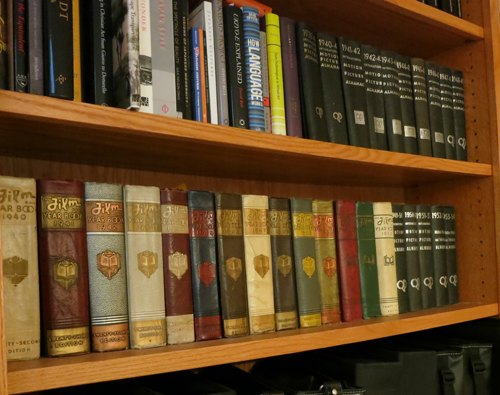

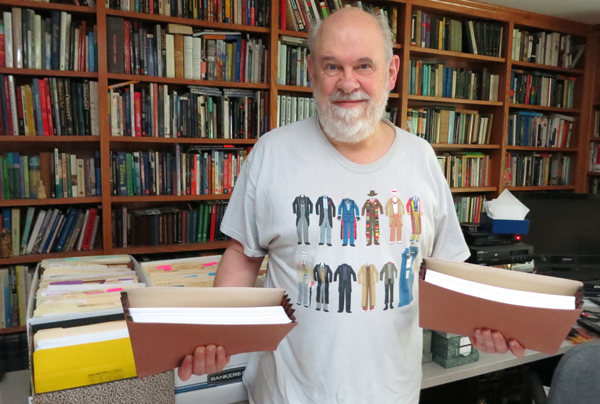

In the meantime, just to give you an idea of how one writer makes a book, I append some images from the workbench, before I pack up the paperwork. Here are the file folders and note cards I worked from. Hard to get those long note-card boxes nowadays; I needed 8 1/2 for this project.

Yes, I’m still a pen-and-paper nerd. All that’s changed since my 60s student years is the worsening of my handwriting.

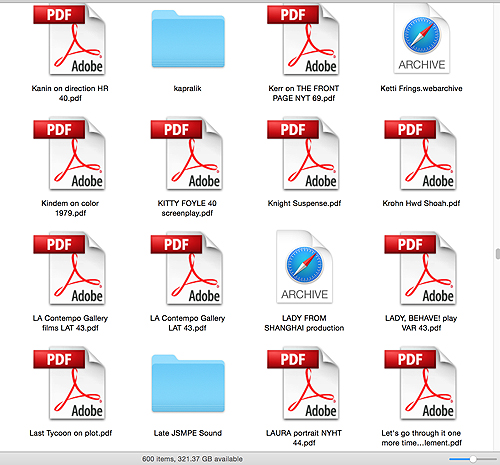

Like you, I have hundreds of digital files too.

I was reliant on my old friends, The Motion Picture Almanac and The Film Daily Yearbook.

I amassed many albums of DVDs, as you’d expect–thanks chiefly to Turner Classic Movies.

Of course there are scores of books about films and figures of the period. I depended a lot on two key surveys: Douglas Gomery’s Hollywood Studio System (both editions) and Tom Schatz’s Boom and Bust: American Cinema of the 1940s. I didn’t rely much on all those books of a reflectionist, Zeitgeisty flavor–for reasons I’ve indicated here as well as in the book.

Reinventing Hollywood should be out this time next year. It should run to around 550 pages, with 180 illustrations. In addition, I’ll be putting up a dozen or so clips online to supplement some of my analyses. Hereabouts, from time to time I’ll preview arguments in the book.

I want to thank my editor, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues at the University of Chicago for supporting the book. I also owe a debt to Jim Naremore, Jeff Smith, and Malcolm Turvey for their close reading of the thing in draft form, and of course to Kristin for help in matters big and small. The couple dozen of friends and colleagues who helped me, too many to list here, are gratefully acknowledged in the text.

To give you a sense of what the book is up to, I’ve gathered most of my Forties blog entries into a separate category. Some of these are grist for the book, and some, like the ones on The Magnificent Ambersons and on The Chase, expand the book’s analysis.

In all it reminds me of what the Duke of Gloucester said to Gibbon: ““Another damn’d thick, square book! Always, scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh! Mr. Gibbon?” I’ve used this before, but after writing or rewriting seven books since I retired in 2004, it seems even more grimly appropriate. The reader is warned.

Photo by Kristin Thompson.

Is there a blog in this class? 2016

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991).

KT here–

Another year has passed, and Observations on Film Art is approaching its tenth anniversary. The blog was never intended as a formal companion to our textbook Film Art: An Introduction. Basically we write about what interests us. Still, many of our entries use concepts from the book, and we hope that teachers and students might find them useful supplements to it.

As each summer approaches its end and teachers compose or revise their syllabi, we offer a rundown, chapter by chapter, of which posts from the past year might be relevant. (For previous entries, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015.) For readers new to the blog, these entries offer a way of navigating through the site.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Film projection made the national news in late 2015 when Quentin Tarantino released his new film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film. Only 100 theaters in the USA, most of them specially equipped with old, refurbished projectors, could show it that way. We went behind the scenes to see how the theaters coped in THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth and THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing.

This year the studios took tentative steps toward instituting The Screening Room, a system of streaming brand-new theatrical films to people’s homes for $50. Whether or not this service succeeds, it represents one new distribution model that Hollywood is exploring to cope with the increasing delivery of movies via the internet. See Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop.

Popular film franchises can go on generating new products and influencing other films for years. We examine the lingering impact of The Lord of the Rings thirteen years after the third part was released in Frodo lives! And so do his franchises.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In this chapter we put considerable stress on the concept of narration, the methods by which a film conveys story information to the viewer. There is no end to the ways in which narration can be structured. Often one of the characters in a film can to tell us what happened. . . even if that character is dead. This, as we show in Dead Men Talking, is not as rare as one might expect.

The Walk combines narrative and genre in an unusual way. The first part is a romantic comedy, the second a suspense film, and the third a lyrical piece. We suggest why in Talking THE WALK.

The way a film tells its story can vary considerably depending on whether it has a single protagonist, a dual protagonist, or a multiple protagonist (as in The Big Short, bottom). We examine some of the differences in Pick your protagonist(s).

Looking back over our blog as we passed 700 entries early this year, it occurred to us that several entries discussing principles of storytelling could be arranged to create a pretty good class in classical narrative strategy. We made up an imaginary syllabus in Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101. No tuition charged.

With the very end of the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise–the release of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third Hobbit film–we discuss the strengths of the film and the plot gaps left unfilled in A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

To celebrate Orson Welles’s 101st birthday, we examined some of the sources for some of the techniques used in Citizen Kane, a film we analyze in detail in Chapters 3 and 8. See Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts.

In Hollywood it is a common assumption that the protagonist(s) of a film must have a “character arc.” Filmmaker Rory Kelly, who teaches in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, wrote a guest entry for our site. Rory analyzes the character arc in The Apartment, with examples from Casablanca, Jaws, and About a Boy as supplements. See Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly.

James Schamus’ Indignation, an adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, draws on novelistic narrative devices not in the original. In INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film, we suggest that those devices first became standard in cinema during the 1940s.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

Teachers and students always want to us add more about acting to our book. It’s a hard subject to pin down. We introduce the great stage actor Mark Rylance, who was largely unknown outside the United Kingdom before he won an Oscar for Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, and discuss how he achieves his expressively reserved performances in that film and the series Wolf Hall. See Mark Rylance, man of mystery. (Above at left, on set with Tom Hanks and Spielberg.)

In an era when most staging of actors in movies follows a few simple conventions, we examine the more imaginative ways of playing a scene on display in Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950) in Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers young and old.

Continuing with the theme of acting and staging, our friends and colleagues, Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have put a revised version of their in-depth study of silent-cinema acting online for free. Learn about it and the enhancements that internet publishing has allowed in Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

We look at the visual style of Anthony Mann’s Side Street (1949) and show how a simple, seemingly minor technique like a reframing can create a strong reaction in the spectator. See Sometimes a reframing …

Framing a composition is one of the most basic aspects of cinematography. We discuss centered framing, decentered framing, balanced framing, framing in widescreen movies, and particularly framing in Mad Max: Fury Road (above) in Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom.

In a follow-up entry, we discuss framing in the classic Academy ratio, 4:3, with emphasis on action at the edges of the frame: Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket.

Chapter 7 Sound in Cinema

For the new edition of Film Art, we had to eliminate our main example of sound technique, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige. But we put that section of the earlier editions online. THE PRESTIGE, one way or another takes you to it.

For those who have been looking for examples of internal diegetic sound, we take a close look (listen) at a sneaky one in Nightmare Alley: Do we hear what he hears?

The fact that the protagonist narrates The Walk in an impossible situation, standing on the torch of the Statue of Liberty and talking to the camera, bothered a lot of critics. We suggest some justifications for this decision in Talking THE WALK.

We offer brief analyses of the Oscar-nominated music from 2015 films in Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Many different filmic techniques can serve similar functions. Filmmakers of the 1940s had a broad range to choose from when they portrayed dead people, or Afterlifers, on the screen. We look at how their choices affected the impact of the scenes (as in Curse of the Cat People, above) in They see dead people.

Style and form in three films of Terence Davies: Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes; and especially his most recent work, Sunset Song. See Terence Davies: Sunset Songs.

Style and form in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, on the occasion of its magnificent release by The Criterion Collection, in A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY: Yang and his gangs.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated

Leo Hurwitz’s little-known documentary, Strange Victory (1948) has recently come out on Milestone’s DVD/Blu-ray. Released shortly after the end of World War II, it suggests that the Nazi atrocities were only an extreme instance of the cruelty of racism. We discuss the film and its relevance to the current political situation in Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948).

Experimental filmmaker Paolo Gioli makes films without cameras, or at least, he cobbles together pinhole cameras of his own from simple materials. The results are remarkable. We describe his work and link to a recent release of his work on DVD in Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

The eleventh edition of Film Art contains a new sample analysis of Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom. We discuss some additional aspects of the film in Wesworld.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

At the end of each year we avoid doing a standard ten-best list by choosing the ten best films of ninety years ago. For 2015, we dealt with The ten best films of … 1925 (including Frank Borzage’s Lazybones, above). It was a very good year.

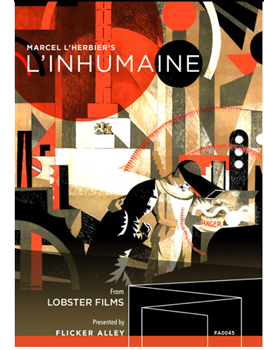

A rare French Impressionist film, Marcel L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine, has been released on DVD/Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. We discuss the film and its background in L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema.

Film Adaptations

Our eleventh edition offers an optional chapter on film adaptations from a wide variety of art forms and even objects.

For thoughts on popular female novelists whose books were adapted into films during the 1940s and 1940s (and who sometimes became screenwriters), see Deadlier than the male (novelist).

Adaptations can be made from nonfiction as well fictional books. We look at how Dalton Trumbo’s life was made into a biopic in Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO.

In a series of entries, we have commented on the adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit into a three-part film. For an analysis of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third part, see A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump? (Links in that entry lead to earlier posts on this subject.)

As always, we have blogged about some recent books and DVDs/Blu-rays. See here (Vertov, sound technology, 3D), here, (Kelley Conway’s new book on Agnès Varda), here (experimental films, the first Sherlock Holmes, the Little Tramp), here (Tony Rayns on In the Mood for Love), and here (on some older foreign classics that have finally made it to home video in the USA, primarily those of Hou Hsioa-hsien). The publication of the eleventh edition of Film Art led us to look back on how it was written and some of the ideas that went into it. We took the occasion to introduce our new co-author, Jeff Smith. See FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

We were also profiled in Madison’s local free paper, Isthmus, by Laura Jones, reporter and filmmaker. She read Film Art as a student.

The Big Short (2015).

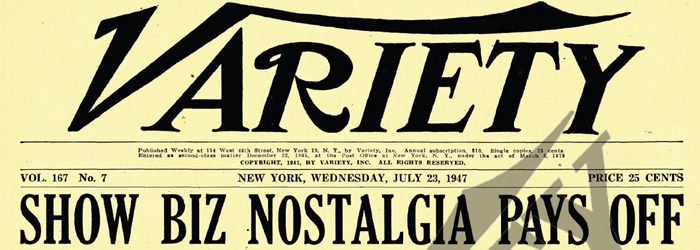

Born on the 23rd of July

The Wisconsin State Journal, Wednesday 23 July 1947.

DB here:

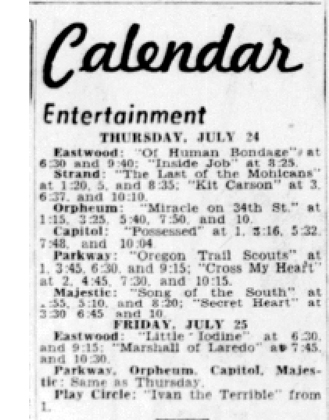

Today I turn 69. (Please keep the cheers discreet.) I was born in western New York State, but I’ve spent over forty years in Madison, Wisconsin. So for fun I thought I’d take a look at what you could have seen on 23 July 1947 in my current home town.

This isn’t (just) an exercise in baby-boomer self-regard. Looking at the movie ads in the Wisconsin State Journal for that fateful day can remind us of interesting stuff about American cinema of the postwar years. Or so I think, fueled by work on Hollywood in the 40s for a book I’m nearly done with.

Classics, just passing through

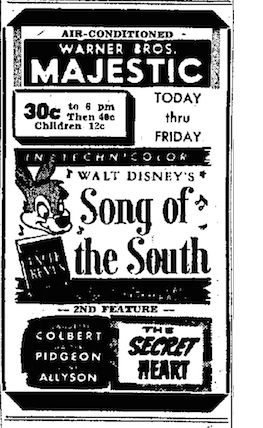

Song of the South (1946).

The first thing that strikes me the quality that’s on offer. On that Wednesday you could have seen four superb films (Rebecca, Stairway to Heaven, Song of the South, Possessed) and two worthwhile pictures (Of Human Bondage and Miracle on 34th Street). These movies are still remembered and admired.

Can this morning’s list of multiplex showtimes promise anything so enduring? Maybe Finding Dory and The BFG will be watched sixty-nine years from now, but our other current releases seem bound for oblivion. And of course the 1947 bill of fare was, with the important exception of Song of the South, designed for grownups.

Those who want to use this 1947 data-point as an example of the death of American cinema are welcome to do so.

Admittedly, today we don’t expect summer to generate the highest-quality films. (Though it often does; think of the last Mad Max installment. And James Schamus’s Indignation is coming up next week.) In 1947 the summer market was rather different from that today. Studios planned their major releases from late August onward, with big pictures playing through fall, winter, and early spring. June, July, and much of August were a slack stretch, when, Hollywood charmingly assumed, people wanted to be outside. So summer releases tended to be minor titles, and exhibitors turned to foreign fare, B pictures, and reissues.

Still, Possessed and Miracle were brand-new releases. At the end of the 40s, it seems clear, studios began releasing more of their important pictures in the summer. And as you can see, air conditioning–rare then, even in public buildings–lured some folks in.

In any case, for moviegoing purposes, I’d rather have been in Madison in July of 1947. In the two weeks sandwiching my birthday (16 July-30 July), I could have seen Brief Encounter, Her Sister’s Secret, Tomorrow Is Forever, Tender Comrade, The Sea Hawk, The Sea Wolf, Dead Reckoning, The Hucksters, The Unfaithful, The Lady in the Lake, Bohemian Girl, Boom Town, The Razor’s Edge, Love Laughs at Andy Hardy, Mr. District Attorney, Calcutta, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, Angel and the Badman, The Dark Mirror, Till the Clouds Roll By, Pursued, and Sister Kenny—along with a couple Lone Wolf and Falcon movies. Not a bad lineup. And I’m not counting La Grande Illusion and Ivan the Terrible on the UW campus.

Safety in numbers

Possessed (1947).

Then there’s quantity. Madison, Wisconsin had a population of about 65,000 in the year of my birth. It was dwarfed by Milwaukee, which had nearly ten times that. Yet by my count, over the two weeks around my birthday, a Madison moviegoer had 73 films to choose from. For the same 15-day stretch in town today, I come up with no more than 20. (For both time frames, I’m not counting campus or library screenings.)

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

Of course my 69-year-old self has a much bigger choice of movies than what’s in theatres. I can choose among thousands of titles on cable TV, disc, or streaming. TV wasn’t a significant part of the American landscape in 1947. Cinema existed in an economy of scarcity rather than overabundance.

This circumstance led people to go immediately to see the newest picture, as they couldn’t be sure it would return in second-run or a reissue. Today many of us skip a new release in theatres because we know we can catch it in a later video window. Does this all-you-can-eat plenitude make cinema seem less urgent and immediate—more a matter of “content” filling libraries and bookshelves and hard drives and Netflix queues? I think so. We’re all collectors now, in a way a 1947 moviegoer couldn’t be, but that means we lack the impulsion to see most films immediately. It takes effort to go out to see a film, but maybe that effort makes the experience more valuable (when the movie is satisfying, of course).

Dueling duals

Oregon Trail Scouts (1947).

The ads reveal more about quantity. You’ll have noticed that a great many of the films are playing on double bills (“duals”). From the 1930s on there was a perpetual debate about whether duals helped or hurt the industry. Most studio chiefs deplored them and confidently announced that a majority of audiences didn’t like them. The trade papers regularly ran stories predicting that the dual’s days were numbered.

They were wrong. Duals persisted into my college years; to see Help! (1965) twice in first release without buying another ticket, I had to sit through The Glory Guys (1965). Most exhibitors were independent of the studios, and they liked duals. So, obviously, did many viewers, who enjoyed getting two movies for the price of one.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

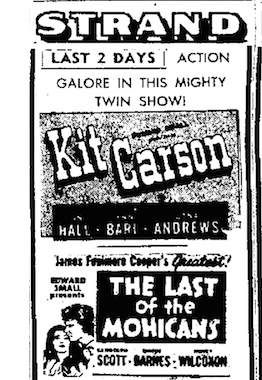

The other theatres in the ad are running duals. Some of them ran recent releases, but late in the run. For instance, the Parkway (despite its name, another downtown theatre) was a big venue, with a 1200-seat capacity. On my birthday it screened Cross My Heart (a January ’47 release) and Oregon Trail Scouts (a May release). These were first-run, but with less must-see appeal than Miracle and Possessed. Also, Oregon Trail Scouts is a prototypical B picture, running 58 minutes. So the Parkway, another Fox-controlled screen, mated a mildly attractive Paramount programmer or “nervous A” with a Republic B. A third Fox venue, the Strand, a 1300-seater on the square, drew on second-run titles and reissues for its duals.

The town’s smaller theatres relied on duals. The Majestic, an old vaudeville house with some of the most skewed sightlines in Christendom, was at that point another Warners house. Yet it had no qualms about showing subsequent-run titles from Disney/RKO (Song of the South, in its third Madison run) and MGM (The Secret Heart, back for a second).

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

As a result, in my one-day snapshot every major Hollywood studio is represented; even RKO gets in with its “Passport to Nowhere” short. How can this be, in a town with four Fox screens, two Warners screens, and only one independent exhibitor? Research by our colleague Andrea Comiskey has shown a remarkable flexibility in studio screening policies. Often a subsequent-run house owned by a studio played few or none of the studio’s own releases. This way everybody could make money off everybody else’s movies. Such are the ways of oligopolies.

Why so many B’s, particularly Westerns? Given double bills, they were what the trade papers openly called fodder, and they saved money. B’s were rented on a flat-fee basis, while A’s were rented on a percentage basis. Some exhibitors ran the B more frequently than the A each day, so as to keep more of the box-office take. Such wasn’t the case with the Madison, though: Both Stairway and Vigilante played an equal number of times each day.

Was the B the chaser, clearing the house after the A? Maybe, but maybe someone coming to see a prestigious Powell and Pressburger would stick around for Jon Hall and Andy Devine. In any case, since the Big Five studios were making fewer pictures in the 1940s and were concentrating on A items (the big-ticket income), the ongoing demand for duals helped less important studios, which were heavy suppliers of B’s.

There was only one independent house in Madison proper. The Eastwood (still standing, now a live venue and called the Barrymore) was playing second-runs in its 950-seat auditorium.

Finally, runs were tied to ticket price. I haven’t got good information on ticket costs in these theatres, but the fact that the Majestic boasts of charging $.30 until 6 PM, and then bumps the cost to $.40, is typical of a second-run house of the time. First-run tickets, depending on time of day, could be $.50 or more.

Those costs, by the way, translate to ticket prices between $3.30 and $5.50 in today’s currency. Another data point favoring the good old days.

Heavy rotation

The Middleton Theatre, Middleton Wisconsin, in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

Duals multiplied the number of pictures on offer. So did the length, or rather the brevity, of runs.

The first-run A’s, Possessed and Miracle on 34th Street, ran a week; Miracle, in fact, was moved over to the Madison at the end of July for a longer stay. But most duals changed more frequently. The Madison’s dual of Tomorrow Is Forever and Tender Comrade ran five days, as did the Strand’s Last of the Mohicans and Kit Carson. But the Parkway typically changed bills every three days, while other theatres split up the week even more. Some programs ran only two days.

We’re so used to pictures hanging on for weeks or months that these rapid playoffs are surprising. But here my birthday snapshot is a bit misleading. Many of the films brought in for two or three days were second-run titles, and a surprising number were reissues.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

The number of reissues increased powerfully just before my birthday. In late May, the Hollywood Reporter claimed that of 224 pictures playing in metropolitan New York, 105 were “oldies.” Just after said birthday, HR reported that “the highly satisfactory boxoffice results from reissues in recent months, plus the necessity of averaging down the cost of new productions which continue to call for multi-million dollar budgets, will result in nearly twice as many reissues in 1947-48 as in the past year.” That number was said to be 75 from the Majors, along with another 100 or so titles already sold or leased by non-Majors.

The oldest reissue on offer in Mad City on my birthday was The Last of the Mohicans (1936), paired with Kit Carson (1940). This package had already had great success in New York and had helped sustain the reissue boom. So strong was this Mighty Twin Show that producer Edward S. Small could demand not the usual flat-rate terms but rather a 35% of the box office. In Madison during the weeks around 23 July, you could have seen a great many other films from the 1930s and 1940s, on brief-stay duals.

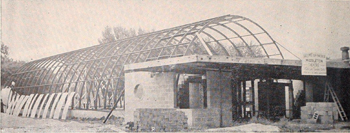

Speaking of reissues, the Middleton, the venue announcing Rebecca in the ad, is interesting in its own right. Middleton is a pretty bedroom community west of Madison, then with about 2000 souls. Now, thanks to infill, it’s more or less a continuation of our town. Its theatre, an independent house built in 1946 and with a capacity of 500, ran both second-run and reissues, including, during the DB magic weeks, Sun Valley Serenade (1941), The Westerner (1940), and, for one day, Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942).

Maybe more interesting is that the Middleton was a Quonset hut, with a wraparound roof.

More about the Middleton here. Kristin and I saw E. T. there, and I wish we’d gone more often. It was demolished in 1992.

Foreign accents

A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven, 1946).

The presence of Stairway to Heaven (in first run) points up another trend. During the 1940s, foreign films gained a new prominence on American screens. While reissues were flooding New York City screens as noted, the number of imports among them was sharply up: fourteen British titles, five French, four Spanish, three Italian, two Russian, and one Swedish.

Those proportions reflect the growing popularity of British cinema. At year’s end, Variety noted that the number of British releases in 1947 doubled from the previous year, from ten to twenty. In the two weeks surrounding my birthday, Madisonians could have seen Brief Encounter, also at the Madison. The Madison seems to have sometimes operated as an art house. It screened Open City a month earlier, promoted in a memorable ad that somehow plays up sexytime without showing Anna Magnani.

Note what’s playing with it. The Madison stayed classy.

1946 was the high-water mark of American movie attendance and Hollywood studio profits. 4.7 billion US tickets were sold, and profits came to nearly $120 million. Attendance remained strong in 1947, but profits started to fall steeply, to about $87 million. The soaring costs of production, including millions spent on rights to projects that were never filmed, came due. And soon enough attendance dropped calamitously as well. Ticket sales in 1952 were only a bit more than half of 1946’s total. A great many Americans stopped going to the movies.

There were rumblings, though, before I showed up. “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” announced the headline of Hollywood Reporter for 20 May 1947. Was this just a “spring slump,” such as those before World War II, when good weather drove people outside? “If there is no general rise in grosses by the middle of July,” said one executive, “then our fears will have been realized, as it will reflect an economic crisis.” Studio employment was off 20%; the Majors’ building plans were put on hold; and reissues from non-Major sources were gaining a bigger share of the receipts. Ultimately, 1947 fell off only a little, but film folk were nervous. The big dip would come soon.

Another crisis: In less than a year after my birthday the Supreme Court would declare that the studios’ ownership of theatres was monopolistic, and the companies would begin gradually splitting off their theatre chains.

I was born, then, on a sort of cusp. By the time I was 5, people were declaring the studio system dead. Knowing nothing of this, I continued watching new releases (Peter Pan, Francis the Talking Mule movies) and old films that were starting to show up on TV. I didn’t suspect that, decades along, I would spend my more-or-less adult life studying those movies that played the Capitol, the Parkway, and the Middleton. Just looking at this page from the State Journal has me hoping that Kristin gets me a time machine for my next birthday.

For help in preparing this entry, thanks to Lea Jacobs, Jeff Smith, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Lisa Marine, and Rob Thomas.

Some sources: “Double-Bill Reissue Packages Prove Surprising B.O. on B’way,” Variety (9 April 1947), 7, 18; “Re-Issues Flood New York Screens,” Hollywood Reporter (22 May 1947), 1, 3; “Reissues Doubled for 1947-48,” HR (26 August 1947), 1, 11;”Industry Schedules 130 Re-Releases for This Year,” HR (5 February 1948), 1, 13; “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” HR (20 May 1947), 1, 12; “Industry in Crucial Period before Upturn, Say Toppers,” HR (26 May 1947), 1, 12; “July Will Disclose Actual Extent of Boxoffice Downturn,” HR (9 June 1947), 10; “8 Majors and 4 Lesser Distribs Released 428 in ’47 vs. 405 in ’46,” Variety (31 December 1947), 6. Chapter 6 of Susan Ohmer’s book George Gallup in Hollywood (Columbia University Press, 2006) provides an excellent overview of the disputes about double bills.

There was another crisis in my late prenatal phase. In response to shopkeepers, the ever-watchful Wisconsin state legislature had drafted a bill banning candy, food, and drink from being sold in movie houses. Exhibitors mobilized and lobbied for tasty snack treats. “With boxoffice grosses rapidly slipping from their wartime peaks to pre-war levels, the candy, popcorn, sandwich and soft drink sales now are especially essential to keep the houses on the profit side of the ledger.” “Wisconsin Candy Sale Ban Doomed,” HR (7 May 1947), 5. Fortunately for all Cheeseheads, this bill was defeated.

Browsing the wonderful site Cinema Treasures can make you aware of all those lost movie houses. The Wisconsin Historical Society presents many photos of Madison’s old theatres. My photo of the Middleton in the 70s comes from this collection, Reference no. 5572.

The saga of Madison’s Orpheum is told in part here, though an update on all the intrigue is probably in order. At least the magnificent sign has been redone and has gone up. The Capital Times covers the process here and here. The refurbished sign got lit up last night. For more on local theatres, including the ones I actually frequented back East, go here and here. Also relevant is this visit to Rochester’s Cinema Theatre, with information from Andrea Comiskey. Also a cat.

On the importing of movies from overseas at this period, the definitive source is Tino Balio’s book The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2010).

P.S. 30 July 2016: The Middleton Theatre stirs fond memories. See Nadine Goff’s Facebook page on historic Wisconsin photographs for reminiscences of sticky floors and rain on the roof.

Another fateful birthday headline.

L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema

Kristin here:

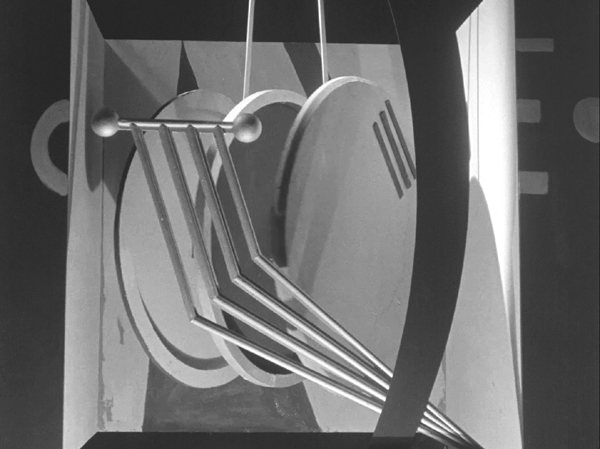

Flicker Alley continues its relationship with Lobster Films of Paris, bringing out beautifully restored versions of French silent films, and in particular the work of the French Impressionist filmmakers. The recent release of Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1924) is stunning visually. L’Herbier produced the film himself with his new Cinégraphic company, and hence he preserved the negative. With the original art-deco intertitles (below) and the colors as chosen by L’Herbier, this is as close as one can get to a version that is identical to the original release prints.

We’ve described earlier Flicker Alley releases of classic French silents in restorations: the extraordinary output of the Russian emigré firm Albatros, the long-lost serial La Maison de mystère, and Abel Gance’s La roue. L’Herbier’s Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), made directly after L’Inhumaine, was in the Albatros set but also released separately.

Although I’ll be mentioning most of the major plot points of L’Inhumaine, I’m not posting a spoiler alert. The action does involve some nominally suspenseful situations, but L’Herbier signals what’s going to happen so far in advance that I suspect few people watching the film would be surprised by the “twists” in the story.

The film’s plot is, to put it bluntly, weak. The “inhuman one” of the title is Claire Lescot, an opera singer who delights in frustrating the powerful suitors and would-be seducers who gather at banquets that she stages in the spectacularly designed rooms of her lavish home. In the opening dinner scene, she is particularly cool to Einar Norsen, a brilliant but naive young inventor who is in love with her. When he seemingly threatens suicide, she laughingly remarks that his life cannot mean much if he can throw it away.

Shortly after, word comes that Norsen’s car has plunged over a cliff into a river. The news makes Lescot realize that she loves him. Grieving, she nevertheless performs at a scheduled concert, after which she is visited by a mysterious man who requests that she act as a witness in identifying Norsen’s newly discovered and mutilated body.

Shortly after, word comes that Norsen’s car has plunged over a cliff into a river. The news makes Lescot realize that she loves him. Grieving, she nevertheless performs at a scheduled concert, after which she is visited by a mysterious man who requests that she act as a witness in identifying Norsen’s newly discovered and mutilated body.

The mysterious man, as is obvious from the start, is Norsen in disguise, preparing an ordeal that will lead Lescot to renounce her cruelty and embrace humanity. (The plot of a man who takes the opportunity afforded by a false report of his death to adopt a new identity apparently fascinated L’Herbier. It would become the core of Feu Mathias Pascal, an adaptation of Luigi Pirandello’s 1904 novel.)

Once Norsen reveals himself to Lescot, he shows her his remarkable laboratory, including a machine that may be able to restore the dead to life.

Lescot’s interest in Norsen has enraged one of her suitors, Djohar de Nopur, and he kills her using a poisonous snake in a bouquet. Norsent rushes her to his laboratory and uses his new invention to revive her.

We learn very little about these characters. They are basically stock figures enacting a familiar melodrama. Georgette Leblance, who plays Lescot, was an opera singer who contributed half of the financing in exchange for playing the role. She employs the florid style associated with the great divas of the 1910s, emoting intensely and striking dramatic poses.

If one embarks upon watching L’Inhumaine as a compelling story, one is likely to be disappointed. Its fascination lies rather in the fact that this simple narrative is considerably embellished with flashy design and the novel depiction of scientific experiment.

A leisurely stroll through some remarkable sets

“Flashy design” here means a great deal. L’Herbier had many prominent friends and contacts within the world of arts and crafts in 1920s Paris. The assemblage of collaborators who worked on the look of L’Inhumaine is quite overwhelming. The heroine’s clothes were by one of the leading fashion designers of the day, Paul Poiret, whose interior design department contributed some of the furniture in her apartment (below). The sculptures in her home are by Joseph Csaky, a Hungarian-born Cubist.

There were four main set designers, with contributions by others. Modernist architect Robert Mallet Stevens created the exteriors of Lescot’s house (left) and Norsen’s (right).

By the way, one can still almost walk into a 1920s film today by visiting the Rue Mallet Stevens in Paris, here seen at the time of its inauguration in 1927.

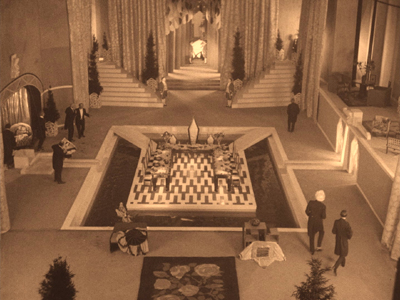

Other designers included Alberto Cavalcanti, who designed the interiors of Lescot’s mansion, notably the huge dining and entertainment hall at the top of this section and a Caligaresque conservatory.

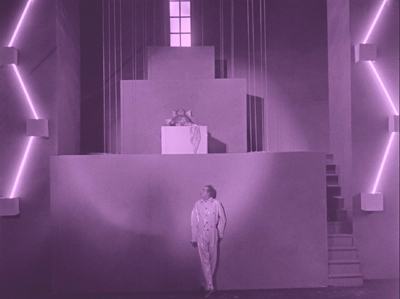

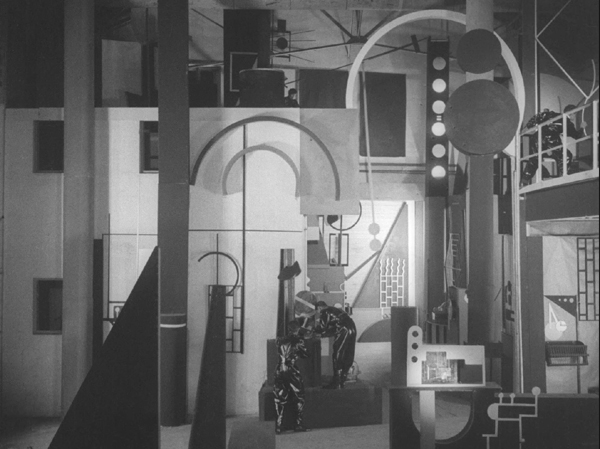

Perhaps most memorably, painter Fernand Léger planned and built the interior of Norsen’s lab (see bottom). More on this below.

The bare bones of the plot are so simple that L’Herbier can proceed at a remarkably leisurely pace through individual decors. In a period when most films consisted of long strings of short scenes, Claire’s opening banquet for her gentlemen guests lasts a remarkable 45 minutes. This includes cutaways to Einar driving rapidly to her house, dithering about whether he should appear late at the party, and finally, after her callous treatment of him, driving away to his apparent suicide. The second sequence, with Claire deciding to perform her song recital despite her grief over Einar’s death, lasts 25 minutes. The primary action here is simply a near-riot in the theatre between her supporters and those indignant about her part in the causing the young scientist’s death.

The lengthy final section of the film visits the laboratory three times, allowing us to get a good look at one of the great sets of the era.

Cinematic touches

L’Herbier did not entirely depend on his designers to carry the visual interest of the film. He was precocious in his use of wide-angle lenses, a technique that would become more prominent in his 1928 masterpiece, L’Argent. Here the lenses used give a less obvious effect, as in the shots of the jazz band that entertains during the opening banquet (above).

He also achieves some impressive compositions using considerable depth of field, most notably a close-up of the hero’s steering wheel as he tears along a road overlooking a deep valley with a city in the distance. It is here where his supposedly suicide takes place. Another striking shot has the jealous villain in the dark foreground, watching as the disguised Norsen enters Lescot’s dressing room.

Très moderne

Although the combined work of such a group of designers is the film’s primary attraction, L’Inhumaine is also notable as an early example of the science-fiction genre. Norsen’s technical genius is represented as going beyond the technology of the age. We see two instances of what he has invented.

The first marvel of Norsen’s laboratory that he demonstrates to Lescot is a television set (so named in the intertitle). Is this the first reference to television in the cinema? Possibly, though the script in quite an illogical way reverses the technology of how actual television would eventually function. Lescot performs a song into a microphone. Instead of a camera beaming her image out to viewers around the world, a screen in Norsen’s lab shows her images of various listeners reacting in delight to her performance–as if somehow cameras could be placed in every spot where someone, whether Arabs, a young black woman in an African field, or a family group in a tropical setting (below) is listening to her over a radio speaker.

The telephone system in Metropolis (1927) that includes screens upon which the speakers view each other reflects more reasonably what actual inventions were later to follow. One can’t help wonder, however, whether that device was inspired by L’Herbier’s film.

More spectacularly, the giant machines that Norsen uses to restore Lescot to life provide the climax of the film. When Norsen tours Lescot around his lab in an earlier scene, he shows her a huge apparatus, including three large, round components that swing through space like a moving Gabo sculpture (see top). He remarks that he believes the machine could restore a dead person to life, but he has not yet had the opportunity to test it.

Rather than trying to suggest how the machine works, the film keeps the set where Lescot lies dead simple and abstract. In perhaps the most famous image from the film, a ziggurat-shaped platform and some simple diagonal lighting tubes shape the composition, with Norsen nervously peering up to gauge the effectiveness of his invention (see top of this section).

The scene of Lescot’s revival consists of rapid, accelerated editing that had become a major trait of the French Impressionist movement by this time in the wake of La roue and Jean Epstein’s Cœur fidèle. There is no way to convey this remarkable sequence with frames from individual shots; the effect is achieved more by the rhythm of the cutting than by the composition of the individual shots.

The Flicker Alley Blu-ray comes with two alternative musical accompaniments, one by the Alloy Orchestra and an adaptation of the original Darius Milhaud score by Aidje Tafial. We listened to the latter, which worked very well with the film. There is also a helpful booklet of notes.