Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO

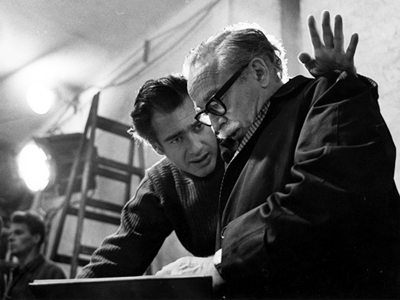

Bryan Cranston as Dalton Trumbo; John Frankenheimer and Dalton Trumbo.

DB here:

Who better to comment on the historical implications of Jay Roach’s Trumbo than our friend and collaborator on Film Art, Jeff Smith? He’s not only an expert on film sound, as he showed in his guest post on Brave, but he has written a book on the Hollywood blacklist. Jeff offers these observations on the film.

Last week, I was delighted to see that Bryan Cranston received an Oscar nomination as the star of Trumbo. Throughout the month of November, I was “johnny-on-the-spot” for local media interested in covering the new biopic about Dalton Trumbo. The story had a local angle. In 1962, Trumbo donated a large collection of scripts, notes, contracts, photos, and business correspondence to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Since then, scholars interested in the Hollywood blacklist have been making pilgrimages to Madison to probe Trumbo’s collection as well as the papers of five other members of the Hollywood Ten (Albert Maltz, Ring Lardner Jr., Herbert Biberman, Samuel Ornitz, and Alvah Bessie.)

I had done a lot of work with the collection, so I could do interviews with WMTV, WISC, The Wisconsin State Journal, and University Publications. Unfortunately I had not yet seen Trumbo, the Jay Roach film based upon Bruce Cook’s 1977 biography. I could talk about Trumbo’s life and career and the buzz I’d heard about the movie, but until it played Madison, I had to stay mum about the movie itself.

After a couple of weeks in distribution in limited release, Trumbo went wide just before Thanksgiving. Now that I’ve seen it, I am delighted to report that Trumbo merits every bit of the hype that surrounded it. To my mind, it is the best fictional film about the blacklist that Hollywood has yet produced.

Buoyed by a standout performance by Cranston, Trumbo is fast-paced and funny, and rather nimbly summarizes many of the political and industrial issues that led to the institution of the blacklist in 1947. It also showcases the effect that “unemployable” writers working on the black market had in undermining the rhetoric of the blacklist throughout the Cold War period. It became hard to say with a straight face that you were protecting American screens from the taint of Red propaganda when films secretly written by Communists were winning awards and topping the box office.

I was struck by some of the choices made by Roach and screenwriter John McNamara in bringing Trumbo’s story to the big screen. Although Trumbo’s career has been well documented by film scholars, Roach and McNamara faced the same challenges in adapting Cook’s biography that any filmmaker does in transforming a literary property into a classical narrative structure. How do you make Trumbo an active, goal-oriented protagonist despite the fact that he was the victim of historical circumstance? How do you deal with the welter of historical actors and subplots that populate Cook’s biography? How do you boil down a complex historical situation into a clear, transmissible narrative?

Witnesses, friendly and otherwise

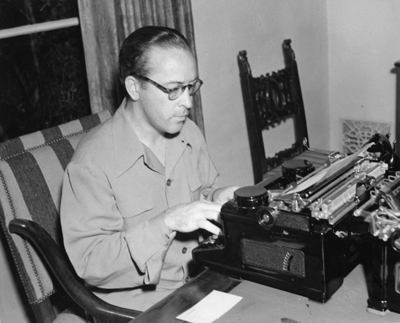

Dalton Trumbo at work.

Like many contemporary Hollywood biopics, Trumbo doesn’t try to convey the full sweep of its subject’s quite colorful life. It omits reference to young Dalton’s Christian Scientist upbringing, his early toils in the Davis Perfection Bakery, or even the publication of his first story in 1933. Indeed, the film also makes only offhand references to Trumbo’s early achievements as a novelist and screenwriter. These are briefly acknowledged near the film’s start through a series of shots in Trumbo’s office at the Lazy-T Ranch that reveal his award for Johnny Got His Gun and his Oscar nomination for Kitty Foyle.

Instead the film focuses on the period of Trumbo’s career during which the screenwriter became one of Hollywood’s sacrificial lambs at the altar of HUAC’s anti-Communism. When the film begins in the mid-forties, Trumbo was the most highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood, earning $75,000 per script. In today’s currency, that amounts to about $800,000 per picture, a remarkable sum for someone under studio contract.

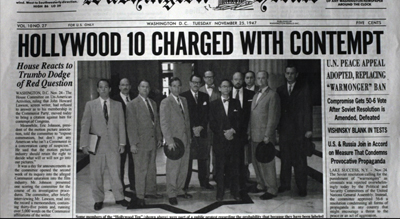

Just a few years later, Trumbo would appear as an “unfriendly witness” during hearings conducted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in October of 1947. As a result, he’d eventually be convicted of Contempt of Congress charges and sent to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky.

Although HUAC was concerned about the potential subversion of American screen content, it was not, in fact, illegal to be a member of the Communist Party. It was, however, a criminal offense to advocate for the overthrow of the American government according to the provisions of the Alien Registration Act (aka the Smith Act) passed in 1940.

About six months after HUAC concluded their hearings on Hollywood, a dozen Communist Party leaders were indicted for Smith Act violations. Defendants insisted that political change in America could be accomplished through democratic process and constitutional principle. But prosecutors claimed these statements couldn’t be trusted since Communists employed “Aesopian language” and therefore did not really mean what they said. The attack proved successful and effectively criminalized membership in the Communist Party as a result. Since any individual’s denial of revolutionary rhetoric would be viewed with suspicion, you were likely seen as guilty of the Smith Act if you simply owned a copy of Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto.

Even before the Foley Square trials, as they came to be known, many of the Communist Party’s rank and file, including the Hollywood Ten, also feared that they would be prosecuted on similar grounds if they admitted their membership. This proved to be one factor that favored the Ten’s failed “first amendment” defense. True, they risked getting cited for Contempt of Congress. But that had the prospect of looking more dignified than simply being hauled off in cuffs on Smith Act charges.

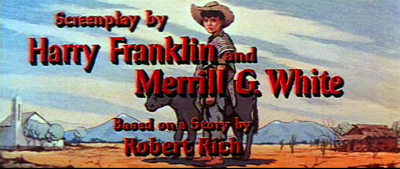

When he returned from prison, Trumbo encountered an industry that wanted him, but not his name on the credits. Producers recognized his talent, and he continued to write through the circuitous network of fronts and pseudonyms. Trumbo would win two Oscars for his work as a black market screenwriter: one for the Gregory Peck/Audrey Hepburn classic, Roman Holiday (below) and another for a Disneyesque “boy and bull” story, The Brave One.

By the end of 1960, Trumbo’s name would once again grace movie screens as the credited screenwriter on Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus and on Otto Preminger’s Exodus. This moment essentially ended what remained of the Hollywood blacklist. In moving from the limelight to the shadows and back again, Trumbo’s life had the kind of plot arc that Hollywood loves. It’s a story of redemption in which the hero overcomes overwhelming odds to regain the professional respect and recognition he’d been denied.

Although all of this suggests that Trumbo is a pretty conventional biopic, it’s quite unconventional in its treatment of the blacklist. As the late Jeanne Hall noted years ago, Hollywood’s representation of this dark chapter of its past was surprisingly evasive, getting on the right side of history but for all the wrong reasons.

Bad Faith in Appleton

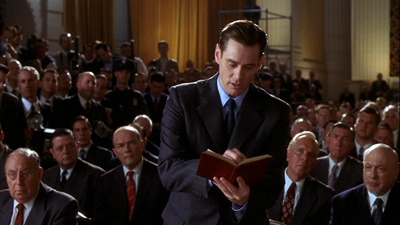

The Majestic (1999).

In titles like The Way We Were, The Front, and Guilty by Suspicion, filmmakers pulled a “bait and switch.” They substituted obvious cases of injustice for the much messier questions posed about HUAC’s abrogation of basic civil rights protections. The Hollywood Ten tried to defend themselves on First Amendment grounds, questioning whether HUAC itself had the right to invade their privacy or to limit their freedom of assembly. But in most of these earlier films about the blacklist, HUAC’s inquiry eventually entangles someone who was never a member of the Communist Party. In The Way We Were, the WASP-y Hubbell comes under suspicion for his relationship with the Jewish radical, Katie. In The Front, Howard comes under suspicion after selling black market scripts by Communist writers under his own name. Both of these instances present obvious cases of individuals wrongfully accused. They recruit our sympathies for characters that suffer as a result of HUAC’s tactics, but gloss over more fundamental questions about whether someone should be denied employment on the basis of their political beliefs.

No film, however, displays the equivocation evident in previous representations of the blacklist as vividly as Frank Darabont’s The Majestic. The protagonist, Peter Appleton, is a Hollywood screenwriter who has just been named by the committee. Distraught, he takes a drive out of Hollywood, but has an accident en route. Suffering from amnesia, Appleton finds himself in the small town of Lawson, California where is mistaken for Luke Trimble, a soldier killed in action some nine years earlier. Appleton becomes immersed in the Lawson community, helping his “father,” Harry, restore the small town theater that gives the film its title. Prompted by a combat film shown in the Majestic, Appleton regains his memory, and confides the truth of his situation to his new girlfriend. After his car is discovered, federal agents give Appleton a summons to testify about his Communist affiliations.

During the climax, Appleton appears before HUAC with the aim of clearing himself. Congressman Elvin Clyde confronts Appleton with evidence that he attended a meeting of the “Bread Instead of Bullets” club. Appleton pleads innocence, saying he only went because he was a “horny, young man” seeking to impress his date, Lucille Angstrom. Just as he is about to deliver his prepared statement purging himself of Communist associations, Appleton changes his mind. Instead he gives an impassioned speech that cites his First Amendment rights and denounces the investigation as a betrayal of America’s real ideals. Appleton saunters out of the hearing to the loud applause of onlookers. Yet Appleton’s lawyer later tells him that Angstrom is currently a CBS producer on Studio One, and his reference to her as a member of the Communist front organization is viewed as cooperation with the Committee.

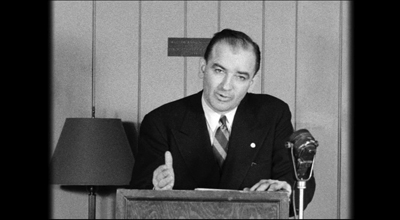

In The Majestic’s civic fantasy, the committee hearing revives the “wrongly accused” trope seen in earlier blacklist films. Worse, it shows its hero successfully using the First Amendment legal defense that had spectacularly failed when the Hollywood Ten used it during the 1947 hearings. Moreover, because Appleton is a political naïf, his inadvertent naming of names redounds to his benefit. Given the film’s hopelessly confused politics, perhaps there is unintentional irony in the fact that Appleton is also the name of the Wisconsin hometown of Senator Joseph McCarthy (below), the man synonymous with the Cold War’s anti-Communist campaign.

Trumbo, in contrast, doesn’t pull any punches. The film condemns HUAC’s activities not because it was prone to wild, unproven accusations like those of McCarthy, but rather because the very nature and essence of its inquiry was itself an abuse of power. The movie does nothing to deny Trumbo’s guilt. Indeed, the real-life Trumbo freely admitted it. In the 1976 documentary Hollywood on Trial, Trumbo described his reaction to his trial thusly: “As far as I was concerned, it was a completely just verdict. I had contempt for that Congress and have had contempt for several since.”

Yet, while not excusing Trumbo’s actions, the film dramatizes the debilitating effects of being blacklisted, both in his professional and personal life. The burden of Trumbo’s black market work put a strain on his marriage and his family, all of whom were enlisted to perform services he himself could not do publicly.

The blacklist: More than Red-baiting

Besides providing a more accurate picture of Red-baiting and its effects, Trumbo also proves remarkable in making passing reference to some of the important secondary causes that eventually led to the blacklist. An early scene, for example, shows Trumbo (above) on a picket line during the vituperative Congress of Studio Union strikes that took place in 1945. Film historian Jon Lewis argues that one reason for the studio’s cooperation with HUAC’s investigation was that it served their interests in their long-term relationship with Hollywood’s craft guilds. Once Communists within the film industry’s labor unions became targets of government scrutiny, only the more moderate factions remained. Whether or not HUAC’s investigation was a direct cause, Hollywood did not experience another strike until more than four decades later.

Trumbo refers to another cause of the blacklist: anti-Semitism. Although it was something of a stereotype, Communists were popularly associated with European Jews. In fact, when Warner Bros. released I Was a Communist for the FBI in 1951, several moviegoers wrote studio head Jack Warner complaining that the film repeated the lie that all Jews were Communists. Said one Julius Newman of Roxbury, Massachusetts: “I demand that this dangerous, rotten, and libelous bit of propaganda be withdrawn immediately before some Jewish mother somewhere, gets her son’s skull cracked for Mother’s Day.”

The perception that anti-Semitism was an underlying cause of the blacklist was aided by the fact that three of the Committee were members of the Ku Klux Klan at the time of the 1947 hearings, including the Chair, J. Parnell Thomas. Moreover, in a speech before the House of Representatives, another HUAC member, Mississippi Democrat John Rankin, attacked members of the Committee for the First Amendment, who had lobbied on behalf of the Hollywood Ten. Rankin claimed that certain performers were suspect because their Anglicized names hid their actual Jewish origins:

One of the names is June Havoc. We found that her real name is June Hovick… Another one is Eddie Cantor, whose real name is Edward Iskowitz. There is one who calls himself Edward Robinson. His real name is Emanuel Goldenberg. There is another here who calls himself Melvyn Douglas, whose real name is Melvyn Hesselberg.

Screenwriter John McNamara wrote a similar speech for Trumbo, but placed it in the mouth of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. When MGM boss Louis B. Mayer reminds Hopper that the legal situation was complicated by the fact that several of the Hollywood Ten had contracts, she responds:

Then how about I make crystal clear to my thirty-five million readers who runs Hollywood and won’t fire these traitors? How about I name names, real names? Like yours, Lazar Meir; or Jack Warner, Jacob Varner; Sam Goldwyn, Schmuel Gelbfisz.

The presence of Hedda Hopper in Trumbo hints at a third underlying cause of the blacklist: the role of the trade press and gossip columnists, who prosecuted and enforced it. Hopper was not alone in this endeavor. Publishers like Billy Wilkerson of The Hollywood Reporter and columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan “cheered” HUAC’s efforts from the sidelines. They also helped the enforcement of the blacklist once it was instituted, calling public attention to the surreptitious presence of banned writers on the black market.

All of these elements in Trumbo’s script make it a richer, more sophisticated depiction of the Hollywood blacklist than that offered by its predecessors. They also remind us that its operations were about more than just politics. Once the blacklist was established, studio bosses gained the upper hand in their dealings with labor, gossipmongers used rumor and accusation to fill column inches and sell papers, and anti-Semites exploited the common association of Communism and Jewish intellectuals to thwart activism among progressives, including those in the Civil Rights movement.

In sum, Trumbo offers a more nuanced sense of the various factors at play at the time of the blacklist than virtually all of its cinematic predecessors. This makes it all the more surprising then that the film nonetheless rewrites history in other ways. In an effort to both streamline and personalize its protagonist’s story, Trumbo invents new characters, revises the order of historical events, and shorts the achievements of other black market screenwriters who also contributed to the blacklist’s ultimate demise.

The eleventh member of the Hollywood ten

Although most film audiences expect that movies will generally portray historical events with some degree of accuracy, Hollywood cinema rewrites history all the time. Despite the fact that this is common practice, some films that take such liberties are hurt by negative publicity, especially around awards time. Recall the controversy surrounding Selma’s depiction of President Lyndon Johnson as an opponent of Martin Luther King’s famous march rather than as a “behind the scenes” ally. Some believe that the loud complaints coming from the LBJ camp cost director Ava DuVernay an Oscar nod.

Trumbo is no exception to this principle, even though it has been unusually forthright about the changes made to the historical record. My spidey senses were alerted to this during the movie when they introduced Louis CK’s character as “Arlen Hird.” I’d never heard of Arlen Hird.

Both in interviews and in an article in the New York Times, screenwriter John McNamara has acknowledged that Hird is a composite character, whose traits and experiences are based on five other members of the Hollywood Ten. Louis CK, for example, physically resembles the real-life Alvah Bessie, who, like the character, was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish civil war.

Moreover, when Hird is in prison, he hears a radio broadcast of Edward G. Robinson’s “friendly” testimony. Robinson calls him “the top fellow who they say is the, uh, commissar out there,” a swipe that blacklist historians would immediately associate with John Howard Lawson. And sadly, like Samuel Ornitz, Hird dies after battling cancer, having never seen the blacklist come to its ignoble end.

As Nicolas Rapold observes in the Times, Hird is meant to stand in for other Communist screenwriters whose attitudes were more doctrinaire than Trumbo’s. Yet I believe the real purpose of using a composite character is to simplify the historical record to make it more digestible for the viewer. Rather than tracing out Trumbo’s relation to all of the eighteen other “unfriendly witnesses” subpoenaed by HUAC, McNamara opts to consolidate them into a single character. Such a decision makes some intuitive sense, since viewers would be hard pressed to keep tabs on a parade of many characters. By creating Hird as a composite, Trumbo’s interactions with him gain vividness and salience.

Still, McNamara’s narrative technique is merely one approach among a larger menu of options, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses. He could have treated the Hollywood Ten as a group protagonist, who all share the same goal in legally challenging HUAC’s authority. Such a gambit, though, would have displaced Trumbo from the center of the story early on. That decision would have weakened the causal motivation behind his later emergence as a black market crusader.

Alternatively, McNamara could have dramatized Trumbo’s individual interactions with Bessie, Lawson, and Ornitz, et.al., using a superimposed title to identify each one. The gain in accuracy, though, would likely mean a loss of dramatic clarity and a mildly more self-conscious style of narration. More important perhaps, it also would make for a less emotionally engaging story. The film shows Hird confiding in Trumbo at the Lazy-T ranch, participating in the Ten’s legal strategy, serving his prison term, and undergoing surgery for lung cancer. The accumulation of these details provide for a more fully fleshed out character. There’s also the opportunity to feel empathy for Hird’s children at his funeral, an effect that couldn’t have been as focused if Hird’s problems were scattered among separate individuals.

None of this is meant to suggest that McNamara absolutely made the right choice in deciding to treat so many members of the Ten as a composite. Rather, it is simply the recognition that such a technique is the result of a deliberate choice and further that one creative decision can lead to a cascade of others. Had McNamara stayed doggedly faithful to the historical record, Trumbo would have been a different film, but perhaps not a better one.

Perhaps we should recognize that screenwriters often must adapt historical narratives in the same way that they adapt literature. And the same sorts of questions about fidelity will bedevil us as when films change details of our favorite novels and stories. Rather than being dogmatic in expecting that historical films stick close to the facts, maybe we simply should ask whether the film is faithful to the spirit of the historical record, especially when its creators are so open and honest about the changes they made. Such a stance would at least recognize the difficulties faced by screenwriters in balancing the weight of classical narrative conventions against the strict measure of historical accuracy. If, as many screenwriters argue, films differ from literature in their emphasis on conflict and action, then the decision in Selma to treat LBJ as an obstacle to Martin Luther King’s goal makes a certain dramatic sense. Here again, one can debate the merits of that creative choice. But at least we do so with a fuller understanding of why such choices are made in the first place.

Get me rewrite!

Besides creating composite characters, McNamara rewrites history in other ways. Perhaps the most obvious is when he creates a scene in prison between Trumbo and HUAC chair, J. Parnell Thomas, which never actually happened. True, Thomas was convicted on corruption charges and was sent to federal prison. But he served his term in Danbury, Connecticut rather than Ashland, Kentucky where Trumbo was incarcerated.

In this case, the real-life story proves more entertaining than what appears in the film. While at Danbury, Thomas encountered two other members of the Hollywood Ten – Lester Cole and Ring Lardner, Jr. — serving their time on Contempt of Congress charges. Upon seeing Thomas working in the prison yard, Cole made a wisecrack that led the former HUAC chair to respond, “I see that you are still spouting radical nonsense.” Cole’s sharp retort: “And I see you are still shoveling chicken shit.”

In other cases, McNamara revises the chronology of events. In the film, Trumbo first meets with the King Brothers, Frank and Hymie, just after he is released from prison. In reality, Trumbo started working for the King Brothers just weeks after his HUAC testimony. Almost immediately after being suspended by MGM, Trumbo did black market work on the screenplay for the King Brothers’ cult classic, Gun Crazy, using fellow writer Millard Kaufman as a front. With Kaufman serving as intermediary, the Kings likely did not know of Trumbo’s involvement. But the brothers began working directly with Trumbo shortly thereafter. In fact, Frank King personally visited the Lazy-T ranch just prior to the Trumbo’s departure for prison, offering to pay him $8,000 to write the script for Carnival Story.

Trumbo coyly acknowledges the screenwriter’s contribution to Gun Crazy by featuring posters of the film in several shots. But by revising the historical circumstances of Trumbo’s first involvement with the Kings, the film more or less denies him actual credit attribution, ironically engaging in the same sort of opportunism displayed by the producers who surreptitiously hired him.

McNamara’s most significant changes to blacklist history, though, involve omissions. Trumbo’s Oscar victory for The Brave One is well documented and the episode – both in the film and in real-life – neatly captures his role as industry gadfly. But the same year that the mysterious “Robert Rich” won the Academy Award for Best Original Story, Michael Wilson also was nominated for a project for which he was publicly denied screen credit.

Wilson had completed a first draft of Friendly Persuasion for director Frank Capra in 1946, but no film was made from the script until producer/director William Wyler took over the project in 1955. When it came time to determine the screenwriter credit, Wyler suggested that it go to Robert Wyler and Jessamyn West for their extensive revisions, including many rewrites completed on set during shooting. When Wilson became aware of this, he immediately protested Wyler’s decision and forced arbitration by the Screen Writers Guild. The Guild ruled in Wilson’s favor, but also reminded the film’s distributor, Allied Artists, that they could legally deny credit to any screenwriter who had failed to clear himself before HUAC. When Friendly Persuasion was released in 1956, its only writing credits read “From the Book by Jessamyn West.”

Despite a good deal of press coverage of the dispute, the incident might have been a mere blip on the cultural radar if not for the 1957 Oscar nominations. When they were announced, a film with no credited screenwriter unexpectedly received a nomination for a screenwriting award. And with public acknowledgement of Wilson’s contribution to Friendly Persuasion more or less verboten, the text of the nomination simply said the writer was ineligible under Academy rules.

Worried that a public victory by a blacklisted writer would give the industry a big ol’ black eye, the Academy reportedly instructed Price Waterhouse to excise the nomination from the Oscar ballots that were sent to voters. Yet, even though the Academy essentially rigged the vote against Wilson, Groucho Marx offered an incisive quip about Wilson’s situation at the Writer’s Guild Awards banquet held about two weeks before the Oscars. Said Groucho, “The Ten Commandments. Original story by Moses. The producers were forced to keep Moses’s name off the credits because they found out he had once crossed the Red Sea.” Given all the effort that went into preventing Wilson from receiving the award, Trumbo’s Oscar win as “Robert Rich” must have tasted even sweeter. The award was given in absentia by Deborah Kerr, and Jesse Lasky, Jr. accepted it.

Moreover, the Rich incident was hardly the last humiliation that the Academy would suffer. The very next year novelist Pierre Boulle received a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination for The Bridge on the River Kwai, which was based on his book. But Boulle had been a front for Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, who had taken the assignment as black market work for producer Sam Spiegel. When Boulle’s name was announced as the winner, the novelist was nowhere to be found. Instead, Kim Novak accepted the award on his behalf. But insiders knew exactly why Boulle was absent. As someone who wrote and spoke in French rather than English, his stumbling acceptance speech would have exposed the hypocrisy by which Foreman and Wilson were denied an award that they merited. (Sadly, neither Foreman nor Wilson would live to see their work duly recognized. In 1984, the Academy posthumously recognized them as the true authors of Kwai’s screenplay.)

Nathan E. Douglas = ?

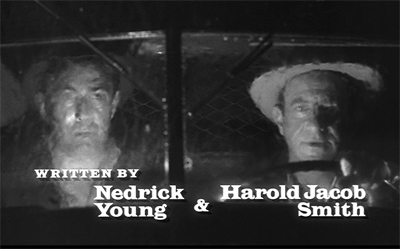

The original credits sequence of The Defiant Ones (1958) listed Nedrick Young as a coauthor under his pseudonym Nathan E. Douglas. He appeared in a bit part coinciding with his credit listing, along with coauthor Smith, in the cab of the truck. Video versions such as this have restored his name.

Things didn’t end there. The Oscar nominations in 1959 saw yet another brewing controversy regarding eligibility of a black market scribe. The writing team of Harold Jacob Smith and Nathan E. Douglas earned a nod for Best Original Screenplay for The Defiant Ones, even though the latter was a pseudonym for blacklisted writer Nedrick Young. If anything, Young’s participation in the making of The Defiant Ones was signaled by producer-director Stanley Kramer’s giving him a notable cameo in the film. During the opening credits, Young and Smith are both seen as prison guards riding in the front seat of a truck used to transport convicts. In a rather coy gesture, when the film’s writing credits are shown, Young’s pseudonym “Nathan E. Douglas” is superimposed over the man himself. Even though the general public didn’t know Young from Adam, his cameo made his participation an open secret in Hollywood.

During awards season, Young as “Nathan Douglas” collected a lot of hardware, including awards from the New York Film Critics Circle and the Writer’s Guild of America. With the nominations imminent, leadership within the Academy recognized that a third straight public relations disaster was in the offing. Just before Christmas in 1958, former Academy president George Seaton approached Young and Smith seeking assistance in overturning the Academy bylaw prohibiting blacklisted personnel from eligibility for awards. For his part, Trumbo himself stayed abreast of the situation and even rescheduled a media interview order to avoid fanning any flames of opposition from within the Academy.

On January 15, 1959, Seaton, Young, and Trumbo all got their wish as the hated bylaw was officially rescinded, passed by the Academy’s Board of Governors with near unanimous support. Two days later, Trumbo confirmed to newsman Bill Stout that he was, indeed, Robert Rich. On Oscar night a few months later, Young enjoyed the spotlight in a way that had been denied his predecessors. And when The Defiant Ones won the Oscar for the Best Story and Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen, Young strode to the podium along with Smith and offered a humble thank you. Ward Bond, one of John Wayne’s allies in the Motion Picture Alliance for American Ideals, observed: “They’re all working now, all these Fifth-Amendment Communists. We’ve just lost the fight. It’s as simple as that.”

Where does all of this backstory fit into the story told in Trumbo? As it turns out, nowhere. In choosing to concentrate on Trumbo’s story, the movie keeps all of this rich contextual material offscreen. As is often the case, the historical realities surrounding the end of the Hollywood blacklist were much denser, messier, and more complex than what can easily fit into a standard two-hour film. Classical Hollywood narrative, with its emphasis on goal-orientation and clearly motivated, causally linked events, tends to nudge screenwriters away from the sprawl more often found in novels or television miniseries. In the case of Trumbo, screenwriter John McNamara likely opted for the virtues of clarity and concision. He concentrated only on those incidents that directly involved the titular character, eliminating or minimizing anything that would detract from that narrative focus.

That being said, the creative choices of McNamara and director Jay Roach are, above all, choices. The screenplay for Bridge of Spies, for example, manages to convey something of the complex bilateral negotiations that linked the downing of U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers with the seemingly unrelated espionage case of KGB officer Rudolf Abel. One could imagine Roach and McNamara devising very brief scenes of Wilson, Foreman, and Young in their Academy imbroglios. Or alternatively, the film might have included Trumbo’s voiceover reading the text of his actual letters to Wilson, many of which commented on the perpetually changing conditions of the black market. As before, the inclusion of such material wouldn’t necessarily make Trumbo a better film. But it would make it a different one.

Although Dalton Trumbo led the fight against the blacklist, often using the industry’s greed, hypocrisy, and mendacity against itself in the process, my brief synopses of these other screenwriters’ Academy Award travails show that he was not alone. Many individuals taking small incremental actions led to the blacklist’s end. It wasn’t smashed; it crumbled through erosion. The fact that one of Hollywood’s “untouchables” was able to openly accept a major industry award made open screen credit a logical next step. Dalton Trumbo happened to be the lucky individual to regain his name without having to bow and scrape before HUAC. But even he knew it could just as easily have been Nedrick Young. Or Michael Wilson. Or Albert Maltz.

Come Oscar night on February 28th, if Bryan Cranston is lucky enough to hoist the Best Actor prize above his head, it will be a fitting tribute to a man whose struggles with this same institution helped to define him and his era. Yet an Oscar victory would also pay tribute to all those whose stories have not reached the screen, but whose grit and determination made Trumbo’s triumph possible. And Mr. Cranston, if you get to deliver that acceptance speech, be sure to remember all those unsung heroes that joined Trumbo in the fight.

Trumbo is based on Bruce Cook’s biography, which was first published in 1977. Readers should also check out Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo’s massive, exhaustively researched new biography, Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical. Ceplair is also the co-author, with Steven Englund, of the standard work on the Hollywood blacklist itself, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics and the Film Community, 1930-1960. My book, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds, also considers Trumbo’s contribution to Spartacus.

Trumbo’s collection of correspondence, speeches, business papers, scripts, and photographs is held at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. A rich sampling of material from it is available here. Several of the photos in this entry come from the WCFTR collection. Go here to listen to excerpts from his HUAC testimony.

Excerpts from John Rankin’s infamous speech about Jewish actors in Hollywood can be found in Gordon Kahn’s Hollywood on Trial: The Story of the Ten Who Were Indicted. Trumbo himself commented on the role of anti-Semitism in HUAC’S investigations in The Time of the Toad: A Study in Inquisition in America.

Franklin Leonard interviewed John McNamara last November about his work on Trumbo for his Black List Table Reads podcast. Nicolas Rapold offers a useful guide to the individuals profiled in Trumbo, including its composite characters. If you’re interested, you can see actual footage of the announcements of various screenwriting awards at the Oscar ceremonies of 1957, 1958, and 1959.

For more on how adaptation works, see the thirteenth chapter of the new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming next week. That chapter is available for courses as an add-on to both the printed edition and the McGraw-Hill electronic edition.

Trumbo.

They see dead people

DB here:

Continuity editing was one of the great collective inventions of filmmakers. In the ten years after it crystallized in Hollywood around 1917, it was adopted around the world. The technique has hung on a surprisingly long time, rather like geometrical perspective in pictorial art. It’s so powerful that it’s hard to escape.

It’s powerful partly because it’s adaptable to a lot of narrative situations. It provides filmmakers what we can call a set of stylistic schemas, or routine patterns, that can be adjusted in various ways. Analytical cuts that take us into or back from the action, shot/reverse shots and eyeline matches, over-the-shoulder framings (OTS), and slight camera movements that set up reestablishing shots: these straightforward schemas can be used in an indefinitely large number of ways.

I‘ve been noticing this flexibility while writing (still!) my book on narrative strategies in 1940s Hollywood. In particular, I was looking at fantasy tales and the peculiar problems they pose for filmmakers. First, how do we represent ghosts, angels, and other visitors from the Afterlife? And how do we make sure that audiences understand that what we see isn’t necessarily what some of the characters onscreen are seeing?

Angels unawares

Our Town (1940).

On the first problem: Today we have CGI resources that allow Afterlifers to move freely among the living characters. These effects were much harder to achieve back then. The supernatural-fantasy genre developed its own conventions (yep, schemas). Most films resorted to presenting the Afterlifer in double exposure.

But superimposed characters can’t move easily among the clutter of furniture in a set. A supered ghost can’t go behind a sofa; the sofa will always be visible through it. You might resort to a traveling matte shot, as William Cameron Menzies did in Our Town (1940), when Emily revisits her family after her death. The shot (just above) is particularly flashy because the younger Emily is also in it.

Or you could pull off the remarkable trick in Earthbound (1940). Here a ghostly Warner Baxter settles comfortably into the middle ground and strides around behind furniture and other actors.

He can even give up his seat to an old lady and shift to another.

These effects were achieved by a technical feat that I don’t fully understand. (See the codicil.) But the trick wasn’t widely adopted, and most filmmakers opted for a simple expedient. Typically the Afterlifer shows up as a superimposition, but he or she gradually materializes and becomes a solid presence like all the other actors. This is from The Canterville Ghost (1945).

Then comes the second problem. Sometimes the living can see the spectre, but sometimes not. In Here Comes Mr. Jordan, the angel Jordan and Joe the prizefighter arrive from the Beyond and watch the murderous couple from behind. They aren’t visible to the living, but they’re just as tangible.

If a living character seems oblivious to the otherworldly guest, we’re to assume that the guest is invisible. Each film has to inform us of who can see what, and most films do—redundantly. The spook or divine messenger will explain that the living can’t see them, or that only certain characters can. (Sometimes children and animals can see them while grownup humans can’t.)

These conventions can get tweaked. Once we know the Afterlifers aren’t visible to the living, they can comment on the action from the sidelines, as when the dead pilot in A Guy Named Joe (1944) slips in wisecracks while his girlfriend is wooed by a young aviator. In the comic The Man in the Trunk (1942), an all-too-tangible ghost can’t follow a character leaving a room. He explains, “I failed my examination on how to walk through walls.” In The Remarkable Andrew (1941), the ghosts of US founding fathers can ransack offices for evidence in an utterly unconstitutional search and seizure. Most ghosts can pick up objects, but the ones in The Cockeyed Miracle (1946) can’t, a fact redundantly explained to us. This generates suspense when they try to grab a fallen bank check. (Incidentally, this is a long, skillfully directed scene, and it does have recourse to a matte shot when one ghost tries. unsuccessfully, to hide the check by standing on it.)

All of these tweaks rely on continuity editing. But in the course of the 1940s, I’ve noticed, filmmakers played a little more ambitiously with the Afterlife conventions, and continuity style allowed them to do it. The results are sometimes provocative.

Ghosts coming and going

Consider the arrival/departure of the Afterlifer. The default is the special-effects twinkling that lets him or her materialize into the scene and fade out of it. But some filmmakers tried more natural options. In Alias Nick Beale, the title character, aka Satan, strolls in from offscreen, or, thanks to John Cromwell’s staging, is masked by other players before being revealed on the scene. He’s presented to all the characters as a real person, but the staging gives him arrivals of relaxed abruptness.

Joseph Mankiewicz’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) finds other ways to avoid the hugger-mugger of transparency and melting departures. Captain Gregg assures Mrs. Muir that to her he is “like a blasted lantern slide,” but for us he just steps into the frame and stays on as a solid presence. He disappears just as simply: Mrs. Muir turns away, then a new shot shows that Gregg has gone. Good old shot/reverse shot does the trick.

It’s neat that the second reverse shot on Mrs. Muir reaffirms Gregg’s absence by making her seem more isolated than the earlier mid-shot does. This cut-back to show her isolation after his departure is stressed even more in a later scene, when a medium shot shows her turned slightly away from him; in that interval, he disappears again.

Only after the captain has decided to leave her forever does he resort to the standard spook trick of dissolving away. But in this melancholy context, the familiar device takes on a forbidding finality. He leaves her sleeping and has magically made her forget all about their year together.

In the epilogue, when the elderly Mrs. Muir dies, the captain returns, sturdy as ever, and again the film avoids the cliché. The default schema is to let the dead person’s spirit float up in superimposition from the corpse. Instead, Mankiewicz presents Gregg standing over the lady in a tight shot and simply lifting the now eternally young Mrs. Muir into the frame. Again, all we need is shot/reverse shot, this time with the extra intimacy of an OTS.

These uncommon options take us a little by surprise, refreshing the genre conventions, while also suggesting that the films drive a little deeper into the heart than the usual spook story. The simplicity of presentation helps us take their spectral affair more seriously.

In The Bishop’s Wife (1947) the angel Dudley, like Gregg, comes and goes via offscreen space. A pan follows Henry the bishop, who hears a noise outside his study. The shot pays off with a reverse-angle cut to Dudley, now magically present at the fireplace where Henry was.

At other points, as in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, the framing excludes Dudley, and when we cut to the long shot Dudley is gone.

Soon, though, there’s a gag on the device. Henry, furious with Dudley, turns away and prays that Dudley will leave him. As earlier, the camera tracks in.

At first it seems that the prayer has been answered, when the camera tracks back from Henry and we see his slightly surprised expression, implying that Dudley has vanished.

But it’s then revealed to us, before Henry knows, that Dudley has changed position and is still in the room.

This quiet revision of the schema is in keeping with the film’s other jabs at Afterlifer conventions. At another point, Henry demands that Dudley execute a miracle. He locks the study door, evidently expecting Dudley to stalk through it in the usual phantom fashion. Instead, Dudley just twists the knob, magically opens it, and exits, closing it behind him and leaving Henry to bang against the relocked door.

Re-turning the screw

In general, supernatural romances play down the magical side of the Afterlifers’ visits. This is partly because they rely on a certain ambiguity about who can see what.

Henry James’ brilliant tale “The Turn of the Screw” provides an instance that people have argued about for generations. The unnamed governess, sent to take care of little Miles and Flora, starts to see dead people: the servant Peter Quint and the governess Miss Jessel. Most of her encounters with the ghosts take place when she’s alone, or with the children. Since the story is narrated from her viewpoint, and in the first person, we have no other testimony about the apparitions. The children seem to spot the spooks, but we can’t be sure. And we can’t be sure that they aren’t simply figments of the governess’s imagination. In the one scene that brings in another witness, the housekeeper Mrs. Grose declares that she can’t see Quint or Miss Jessup. Is the governess mad, or are the children really haunted by the corrupt couple?

The tension exemplifies what narrative theories Tzvetan Todorov called the “fantastic,” the tale of uncertain explanation. The fantastic hovers between scientific, or at least real-world explanations, and supernatural ones. Either the ghosts exist, as in most ghost stories, or they can be explained psychologically, as the narrator’s hallucinations.

Actually, in film, and I think in “The Turn of the Screw,” there’s a third possibility: that the Afterlifers exist as beings who can be seen only by the select few. In “The Turn of the Screw,” Flora definitely seems to see Miss Jessel on one occasion, so perhaps we can posit that the governess sees the ghosts when Mrs. Grose can’t.

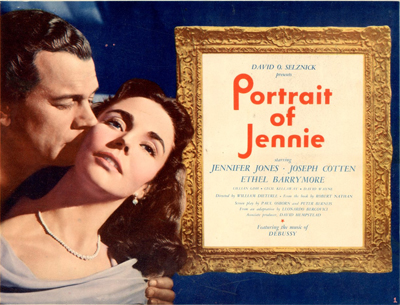

This possibility is of course the premise for The Sixth Sense, and we find it as well in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, in which Gregg is visible only to Mrs. M. The situation is more equivocal in Portrait of Jennie (1949). In this film, David O. Selznick inflated the fantasy-romance genre as he had pumped up the historical drama (Gone with the Wind), the home-front film (Since You Went Away), and the western (Duel in the Sun).

During the winter and spring of a single year, the luckless painter Eben Adams encounters Jennie at different points in her life: as a little girl, a teenager, a college student, and a mature woman. He falls in love with her. Their penultimate encounter takes place when she comes to his apartment and allows him to paint her portrait. Then she disappears.

Is Jennie a time traveler or a ghost or an illusion, or even a supernatural muse? A bit of each. After each brief visit she withdraws, leaving Eben yearning for her. The art dealer Miss Spinney suggests that in order to paint well, Eben must love someone, so perhaps he has conjured up Jennie to inspire his art. It’s true that he sketches, draws, and paints several Jennies. (The final version, the portrait, won’t be shown us until the film’s last image, in blazing Technicolor.) And it’s true that, in a scene much like that featuring Mrs. Grose in James’ tale, we get a hint that Eben is hallucinating Jennie.

He has just spoken with the adolescent Jennie in Central Park when Spinney comes up to him. He watches Jennie go off, in a standard passage of continuity editing.

But then, thanks again to continuity eyeline technique, Spinney doesn’t see her.

Normally this cutting pattern would suggest that Jennie is purely Eben’s vision. (For a modern example, see Johnnie To’s The Mad Detective.) Yet we will soon learn that Jennie did exist. Playing detective, Eben discovers that she was orphaned, taken care of in a convent, and left for college—all things her apparition told him. Worse, he learns how she died: on a rocky seacoast he has already depicted in some paintings.

Selznick was concerned to make Jennie neither a real person nor a pure product of Eben’s imagination. In an early story conference he remarked that Jennie is both in Eben’s mind and in some really existing realm. “We must convince the audience that this story may be strange and odd, but it’s true. All the other characters may say, “Poor Adams, he must be nuts,’ but we know it is true.” The fact that only Eben can see Jennie doesn’t make her a figment of his imagination. Eben may have conjured her up, but she also chose to visit him, predicting that some day he will paint her portrait. The man has, somehow, met a woman from a spiritual world who has been seeking him. Eurydice-like, she will be pulled back into it.

Too few fancies, one powerful friend

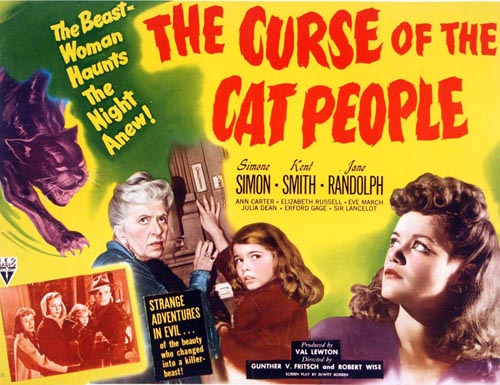

Recognizing that spirits can become selectively visible to the living helps explain the delicate power of another supernatural fantasy of the period. The Curse of the Cat People (1944) uses hyper-judicious framing and editing to create perhaps the most mysterious 1940s Afterlifer.

Irena, the woman who can change into a panther, has died in The Cat People (1943). Her widowed husband Oliver has married Alice, and their child Amy, dreamy and unpopular, wishes for a friend. Near the start of the film we’re led to think that Irena is that imaginary friend, wholly a product of Amy’s mind. Irena comes to her in the garb of a traditional princess or fairy godmother, a bit like the fairy of Pinocchio (1940), so we might take her as Amy’s imagining. And the teacher Miss Callahan, who might seem to be playing the raisonneur, says that the little girl has “too many fancies, too few friends.” But that doesn’t seem to me quite right. I don’t think that ultimately Irena is Amy’s projection. Nor are we exactly in the realm of Todorov’s fantastic, hesitating between subjective and objective explanations.

Consider the progression in the film’s depiction of Irena. At first, Amy is shown playing in the garden, purportedly with her friend but alone in the frame.

Later she says that her friend taught her a song, but she can’t recall the words. This suggests that that encounter, kept offscreen, is a vague one. That night, as Amy awakes from a nightmare, she is soothed back to sleep by her friend, whom we hear softly singing but see as only a shadow. Her lullaby continues as Amy sleeps.

Still later, Irena appears to Amy in the garden only after Amy sees a picture of her. Irena appears un-magically, entering the shot as casually as Dudley or Captain Gregg and holding the ball that Amy has tossed out of frame.

Amy asks her who she is. “I’m your friend.” The fact that Amy doesn’t recognize her from earlier friend-encounters, suggests that the friend wasn’t yet defined in bodily form. She had magical powers, such as darkening or lightening the garden or teaching Amy a song, but she assumed no particular shape. We, however, saw her female silhouette while Amy slept. Now Irena is fully embodied, and we can see her along with Amy.

Apart from the Irena scenes, we do get into Amy’s mind. But the techniques used in those scenes are ones that are never applied to Irena. When a deranged neighbor lady recites the tale of the Headless Horseman, we get exaggerated optical POV shots from Amy’s perspective and the subjective sound of wind and horses’ hooves.

The sounds are repeated as auditory flashbacks in Amy’s nightmare and while she is hiding in the forest during the climactic snowstorm. Later, Amy will calm the old woman’s homicidal daughter by envisioning her as Irena (in a superimposition) and embracing her as “My friend.”

From a storytelling standpoint, such images and sounds are sharply distinguished from Irena’s scenes with Amy. Those are treated in quite a neutral, objective manner.

There’s more. At the midpoint of the plot, in a crucial scene, Oliver learns that Amy considers the dead Irena as her playmate. He’s convinced she’s imagining it all. Anxious and angry, he takes her out into the garden and demands to know if Irena is there. Amy sees Irena under the tree, but Oliver doesn’t. As in Portrait of Jennie, reverse-angle cutting conveys each character’s vision.

In cinema, we assume objective (fictional) reality to be the default value. So the incompatible viewpoints of Amy and Oliver in the garden might suggest that Irena exists only in Amy’s mind. But in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir and Portrait of Jennie, the protagonist can see the ghost when no one else can. Nothing in this garden encounter denies the possibility that Irena is a ghost visible only to Amy and us.

We get some immediate backing for this. When Amy looks at Irena a second time, at Oliver’s insistence, Irena puts her finger to her lips, as if urging Amy not to acknowledge her.

This, to put it stiffly, is the action of an independent agent. Amy is unlikely to conjure up an imaginary friend who warns her to keep quiet. And by telling Oliver that of course she sees her friend, she disobeys just as briskly as if Irena were of flesh and blood.

We have a clincher at the very end of the scene. Oliver and Amy go in, turning away. Neither sees the garden, but we get two shots of Irena watching them and reacting unhappily.

Again, it’s hard to reconcile this image with Irena being a pure projection. She’s behaving like an ectoplasmic free agent. In addition, Alice and Oliver, despite their skepticism about Amy’s friend, don’t rule out supernatural goings-on completely. At various points both mention they sense Irena’s presence in the house. Irena has become in the course of the action a full-fledged ghost, but one with benefits.

The epilogue confirms Irena’s otherworldly mission. As Oliver takes Amy into the house, he asks if she can see Irena. She looks and sees her, smiling.

Can Oliver see Irena? Now that he’s decided to trust Amy, he says yes—without even looking.

As in the earlier garden scene, once father and daughter have gone inside, we’re treated to an independent shot of Irena under the tree. And now she melts away, in the conventional disappearing act of an Afterlifer. As with Captain Gregg’s withdrawal from Mrs. Muir, by saving this well-worn option for this moment the filmmakers invest it with an air of permanent departure.

The Curse of the Cat People cleverly invokes the possibility that Irena is purely imaginary, then dispels it. For once, nobody redundantly explains to us who can and who can’t see the ghost; we have to figure things out. Instead, the vague role of imaginary playmate gets gradually defined as Irena, the ghost. Continuity editing is recruited to suggest that Irena is coalescing into the friend Amy wishes for. At first only an atmosphere, then a shadow, and finally a properly solid spirit, Irena is a shape-shifter, more elusive than other apparitions of the period. The plot creates a sympathetic spirit seeking to console a lonely child and correct her father’s harsh, plodding common sense. Perhaps making amends for her effort to destroy Oliver’s romance with Alice in the previous film, the dead cat-woman fills out the role of imaginary playmate and saves a family.

There are other ingenious ways that the conventions of 1940s supernatural films are tweaked by the resources of continuity style, and I’ll be considering them in the book. The general point is that even schemas as commonplace as eyeline matching, or conventions as hoary as having a ghost dissolve out of the scene, can take on new force when filmmakers practice their craft with discreet intelligence.

Earthbound‘s ghost effect derives from a prism set in front of the camera. Warner Baxter is located in an adjacent set, and one face of the prism was silvered to reflect him onto the primary set. The best description I’ve found is here, thanks to good old Lantern. But we need more information. How can Baxter move so precisely around “our” set if he’s offscreen? Presumably, he’s in either a black set or one with furnishings laid out like ours. In that case, the furniture would need to be draped in black, so parts of his body will be blocked to the right extent. But in either case, we need to explain how he manages to synchronize his movements so exactly with the actors in front of the camera. If you know more, please correspond!

My quotation from Selznick comes from “Portrait of Jennie Conference notes (1/20/47),” David O. Selznick collection, Box 1123, file 11, Harry Ransom Research Center. Thanks to Emilio Banda and to Steve Wilson, Curator of Film at the Harry Ransom Center.

I’m using the concept of an artistic schema as E. H. Gombrich does in Art and Illusion (2000). For more about it on this site, see these entries.

You probably know that “The Turn of the Screw” was filmed as The Innocents (1961). It’s also the basis of a strong Benjamin Britten opera.

A vast survey of Afterlifers on screen is provided in James Robert Parish, Ghosts and Angels in Hollywood Films (McFarland, 1994).

For more on my still-in-progress book on 1940s Hollywood, go here and here. If you’re keen on the Forties generally, you might be interested in The Rhapsodes, my study of film criticism of the period, to be published in March by the University of Chicago Press.

The ten best films of … 1925

The Big Parade (1925).

Kristin here:

As all about us in the blogosphere are listing their top ten films for 2015, we do the same for ninety years ago. Our eighth edition of this surprisingly popular series reaches 1925, when some of the major classics of world cinema appeared. Soviet Montage cinema got its real start with not one but two releases by one of the greatest of all directors, Sergei Eisenstein. Ernst Lubitsch made what is arguably his finest silent film. Charles Chaplin created his most beloved feature. Scandinavian cinema was in decline, having lost its most important directors to Hollywood, but Carl Dreyer made one of his most powerful silents.

For previous entries, see here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.

The lingering traces of Expressionism vs the New Objectivity

The Joyless Street (1925).

Last year I suggested that German Expressionism was winding down in 1924. It continued to do so in 1925. Indeed, no Expressionist films as such came out that year. What I would consider to be the last films in the movement, Murnau’s Faust and Lang’s Metropolis, both went over budget and over schedule, with Faust appearing in 1926 and Metropolis at the beginning of 1927.

Murnau made a more modest film that premiered in Vienna in late 1925, Tartuffe, a loose adaptation of the Molière play. The script adds a frame story in which an old man’s housekeeper plots to swindle and murder him. The man’s grandson disguises himself as a traveling film exhibitor and shows the pair a simplified version of the play, emphasizing the parallels between the hypocritical Tartuffe and the scheming housekeeper.

The film has some touches of Expressionism but cannot really be considered a full-fledged member of that movement. The lingering Expressionism is not surprising, considering that some of the talent involved had worked on Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr.Caligari: screenwriter Carl Mayer, designers Walter Röhrig and Robert Herlth, and actors Werner Krauss and Lil Dagover.

The visuals include characteristically Expressionist moments when the actors and settings are juxtaposed to create strongly pictorial compositions. These might be comic, as when the pompous Tartuffe strides past a squat lamp that seems to mock him, or beautifully abstract, as when Orgon is seen in a high angle against a stairway that swirls around him:

A restored version is available in the USA from Kino and in the UK in Eureka!‘s Masters of Cinema series. (DVD Beaver compares the two versions.) The restoration was prepared from the only surviving print, the American release version; it runs about one hour.

The other German film on this year’s list, G. W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street, contrasts considerably with Tartuffe. It was arguably the first major film of the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity trends in German cinema. I have already dealt with it in a DVD review entry shortly after its 2012 release. The restoration incorporated a good deal more footage than had been seen in previous modern prints, but it remains incomplete.

Once more the comic greats

The Gold Rush (1925).

For several years now these year-end lists have mentioned Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd, in various combinations. Early on it would was Chaplin alone (Easy Street and The Immigrant for 1917) or Lloyd and Keaton alone (High and Dizzy and Neighbors for 1920). In a way most of these films were placeholders, signalling that these three were working up to the silent features that were among the most glorious products of the Hollywood studios in the 1920s. In our 1923 list, each found a place with a masterpiece: Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris, Keaton’s Our Hospitality, and Lloyd’s Safety Last.

This year we may surprise some by giving Lloyd a miss. For years The Freshman was thought of as his main claim to fame, perhaps alongside Safety Last. I think this was largely because The Freshman was the one of the few Lloyd films that was relatively easy to see. (Perhaps also because Preston Sturges dubbed it an official classic by making a sequel to it (The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, aka Mad Wednesday, 1947.) Now that we have the full set of Lloyd’s silent features available, it emerges as a rather tame entry compared to Safety Last, Girl Shy, or our already-determined entries for 1926, For Heaven’s Sake, and 1927, The Kid Brother. Let’s just call The Freshman a runner up.

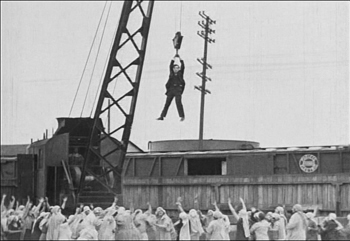

Keaton’s Seven Chances takes one of the most familiar of melodramatic premises and literally runs with it. James Shannon discovers from his lawyer than he stands to inherit a great deal of money if he is married by 7 pm on his 27th birthday–which happens to be the day when he receives this news. A misunderstanding with the woman he loves leads to a split, and in order to save himself and his partner from bankruptcy, Shannon determines to marry any woman who will volunteer in time. Hundreds turn up.

The result is another of the extended, intricate chase sequences that tend to grace Lloyd’s and Keaton’s features, and to a lesser extent Chaplin’s. In fact Seven Chances has a double chase. The first and longer part involves a huge crowd of women gradually assembling behind Shannon as he unwittingly walks along the street. This accelerates and keeps building, exploiting various situations and locales, as when the chase passes through a rail yard and Shannon escapes by dangling from a rolling crane above the women’s heads. Eventually the action moves into the countryside, where the brides temporarily disappear, taking a short cut to cut Shannon off, and he ends up in the middle of a gradually growing avalanche.

Seven Chances is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino.

Of all the films on this year’s list, Chaplin’s The Gold Rush is probably the most widely familiar. The Little Tramp character, here known only as a “Lone Prospector,” blends hilarity with pathos in a fashion that is actually typical of relatively few of the director/performer’s films overall. It is, however, how many people think of him.

The Gold Rush looks rather old-fashioned compared with Seven Chances. Although the opening extreme long shots of an endless line of prospectors struggling up over a mountain pass are impressive, much of the action takes place in studio sets, sometimes standing in for alpine locations. Both the cabins, Black Larsen’s and Hank Curtis’, are like little proscenium stages, with the action captured from the front. Yet the film depends on its brilliant succession of gags and on the Prospector’s status as the underdog who is also the resilient and eternal optimist.

The best bits of humor arise from Chaplin’s ability to create funny but lyrical moments by transforming objects metaphorically. Given the plot, some of the best-known gags arise from meals. One is the dance of the rolls, part of a fantasy sequence in which the Prospector dreams of entertaining a group of beautiful women at dinner (above), when in fact the women stand him up. Trapped by a storm in a remote cabin, the Prospector and his partner cook one of his shoes. He serves it on a platter and carefully “carves it, with the leather becoming the meat, the nails bones, and the laces spaghetti.

Many home-video versions of The Gold Rush have been released, but the definitive restoration of the 1925 version is available from the Criterion Collection.

The Golden Age in full swing

Lazybones (1925).

When people speak of the “Golden Age” of the Hollywood studio system, they usually seem to mean the 1930s and 1940s (and the lingering effects of the system in the 1950s). A look at Hollywood films of the 1920s shows that it was already functioning at full steam. Three features of 1925 display the utter mastery of continuity storytelling and style and a sophistication that matches films of subsequent decades.

Lady Windermere’s Fan may be the best silent made by Ernst Lubitsch, who has appeared on these lists before. It arguably ranks alongside Trouble in Paradise and The Shop around the Corner as one of the best films of his entire career. It’s a loose adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play, but it’s pure Lubitsch throughout.

Anyone who thinks that the classical Hollywood system was merely a set of conventions that allowed films to be cranked out with minimal originality could learn a lot from Lady Windermere’s Fan. Its completely correct use of continuity editing, three-point lighting, and the like does not preclude imaginative touches and methods of handling whole scenes. There’s the sequence when Lord Windermere visits the mysteriously shady lady Mrs. Erlynne in her drawing-room. The camera is planted in the center of the action, with frequents cuts as the two characters move in and out of the frame and even cross behind the camera. There’s not a hint of a mismatched glance or entrance across this complex and unusual series of shots. There’s the racetrack scene, as everyone present watches and gossips about Mrs Erlynne in a virtuoso string of point-of-view shots.

The racetrack scene ends with a wealthy bachelor following Mrs Erlynne out of the track. The camera moves left to follow her, keeping her in the same spot in the frame. As the man gradually catches up, Lubitsch uses a moving matte to hint at their meeting without showing it or cutting in toward the action.

A good-quality transfer of Lady Windermere’s Fan is only available on DVD as part of the More Treasures from American Film Archives 1894-1931. (Beware the copy offered by Synergy, which according to comments on Amazon.com is from a poor-quality, incomplete print.)

The one title on this list whose inclusion might surprise readers is Frank Borzage’s Lazybones. I remember being bowled over by this film during the 1992 Le Gionate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, which included a Borzage retrospective. I found the more famous Humoresque (1920) a disappointment, but Lazybones was a revelation. This is another case of a film that was simply unknown when film historians started writing about the Hollywood studio era. It was not discovered until 1970, when it was found in the 20th Century-Fox archives. As a result, Lazybones was, as Swiss film historian Hervé Dumont put it in his magisterial book on the director, “revealed as the most poignant–and the most accomplished–of Borzage’s works before Seventh Heaven.”

Year by year since we started this annual list, I looked forward to recommending Lazybones, and now we arrive there. I rewatched it for the first time to see if it really deserved to make one of the top ten. The answer is yes. For me, this is as good as 7th Heaven, or as near as makes no difference.

It’s difficult to describe the plot of Lazybones, since it doesn’t have much of one. Steve (played by the amiable Buck Jones) is a very lazy young man living in a rural village. He has a girlfriend, Agnes, whose mother scorns him. The girlfriend has a sister, Ruth, who returns home with a baby in tow. In despair, Ruth leaves the baby on a riverbank and tries to drown herself (image at top of section). Steve rescues her, and she explains that unknown to her family, while she was away she married a sailor who subsequently went down with his ship. She has no proof of this and knows her tyrannical mother will assume that the baby is illegitimate. Steve decides to keep her secret and adopt the apparent foundling himself.

All this happens during the initial setup. Then the little girl, Kit, grows up into a young lady. Along the way, not all that much happens. Steve, lacking any goals, stays lazy, which sets him apart from the energetic, ambitious protagonists of most Hollywood films. Kit is shunned by her classmates and the townspeople, and Steve tries to shelter her from all this. He loves Agnes but quickly loses her to a richer, more respectable man. He goes off to fight in World War I, becomes an accidental hero, and returns home after perhaps the shortest battlefront scene in any feature of the period. Kit finds a boyfriend.

What makes all this riveting viewing is its mixture of quiet comedy and poignancy. Steve is so amiably and unrepentantly loath to work that he is scorned by nearly everyone, and yet he commits an act of great kindness for which he gets no credit at all, except from his devoted mother. It is clear that these snobbish townspeople would scorn him even if they knew how he has kept Kit out of the orphanage and made a happy life for her.

The film is beautifully shot, and Borzage displays such an easy mastery of constructing a scene, particularly in depth, that it is easy to miss the underlying sophistication. Early on, Agnes and her mother arrive at Steve’s house. As Agnes waits outside the fence in the foreground, Steve tips his hat to her, in the foreground with his back to the camera. The mother passes by him toward the house, her mouth fixed in a sneer. We may think that Steve is oblivious to this, but once she passes out of the frame in the foreground, he puts his hat back on and slips it down over his face rather cheekily as he glances at her, his gesture suggesting his indifference to her opinion of him. (Note also the subtle touch of his lazily fastened suspenders.)

Borzage has mastered the use of motifs that are so characteristic of Hollywood cinema. There’s a running gag about the dilapidated gate of the picket fence around Steve’s and his mother’s house, with each person remarking “Darn that gate!” as they struggle through it. The repetition becomes cumulatively funnier because about two decades pass in the course of the film without the thing being fixed. The acting, particularly of Buck Jones and Zasu Pitts (as Ruth), is affecting.

It’s difficult to convey the charms of such an unconventional film, but give it a try and you may be bowled over, too.

A superb DVD transfer of Lazybones was included in the lavish Murnau, Borzage and Fox box (2008). The 20th Century-Fox Cinema Archives series offers it separately as a print-on-demand DVD-R. I’ve not seen it but suspect that there would be some loss of quality in this format. Besides, every serious lover of cinema should have that big black box sitting on their shelves next to the Ford at Fox one.

Returning to the more familiar classics, my final Hollywood film of the year is King Vidor’s The Big Parade.

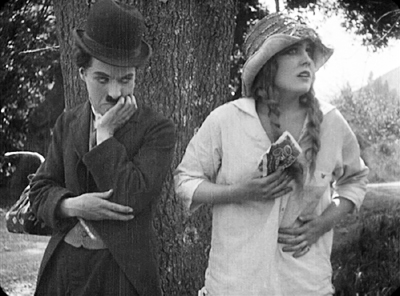

Apart from its success and influence, however, The Big Parade remains an entertaining, funny, and moving film. Vidor’s scenes often run a remarkably long time, suggesting the rhythms of everyday life. One such action involves James fetching a barrel back to where he and his mates are staying so that he can turn it into an outdoor shower. When nearly back, he encounters Melisande, whom he initially can’t see. His stumbling about and her increasing laughter at his antics are played out at length (see top), as is a supposedly improvised scene shortly thereafter where James tries to teach Melisande how to chew gum.

A very different sort of prolonged scene is the long march of James and his comrades through a forest full of German snipers in trees and machine-gunners in nests. They begin by walking through an idyllic-looking forest, then increasingly encounter fallen comrades, and finally reach the Germans.

For years the prints of The Big Parade available were less than optimum, with some based on the 1931 re-release version, where the left side of the image had to be cropped to make room for the soundtrack. A 35mm negative was discovered relatively recently, however, and is the basis for the superb DVD and Blu-ray versions released in 2013.

Finally, I turn you over to David for some comments on films that fall within his specialties.

Eisenstein, action director

Watch this. Maybe a few times.

These two seconds, violent in both what they show and the way they show it, seem to me a turning point in film history. Here extreme action meets extreme technique. The spasms of the woman’s head, given in brief jump cuts (7 frames/5/8/10), create a sort of pictorial fusillade before we get the real thing: a line of riflemen robotically advancing into a crowd.

It’s not usually recognized how often changes in film art are driven by showing violence. Griffith’s last-minute rescues usually take place in scenes of massive bloodshed; not only The Birth of a Nation but the equally inventive Battle at Elderbush Gulch use rapid crosscutting to treat a boiling burst of action. The Friendless One’s pistol attack in Intolerance is rendered in flash frames that Sam Fuller might approve of. Later, the Hollywood Western, the Japanese swordplay film, the 1940s crime melodrama, the Hong Kong action picture, and many other genres pushed the stylistic envelope in scenes of violence. Hitchcock’s vaunted technical polish often depended on shock and bloodletting, from a bullet to the face (Foreign Correspondent) to stabbing in the shower (Psycho). The free-fire zone of Bonnie and Clyde and Peckinpah’s Westerns took up the slow-motion choreography of death pioneered by Kurosawa. Extreme action seems to call for aggressive technique, and intense action scenes can become clipbait and film-school models.

Sergei Eisenstein is celebrated as the theorist and practitioner of montage, whatever that is; but he insisted that what he called expressive movement was no less important. Just as montage for him came to mean the forceful juxtaposition of virtually any two stimuli (frames, shots, elements inside shots, musical motifs), so he thought that expressive movement ranged from a haughty tsar stretching his stork neck (Ivan the Terrible) to peons buried up to their shoulders, squirming to avoid horses’ hooves (Que viva Mexico!). In Eisenstein, psychology is always externalized, crowds move as gigantic organisms, and any action can turn brutal. (I fight the temptation to call him S & M Eisenstein.) We can trace influences—Constructivist theatre, the chase comedies coming from America, his interest in kabuki performance—but when he moved into cinema from the stage, Eisenstein became an action director, in a wholly modern sense.

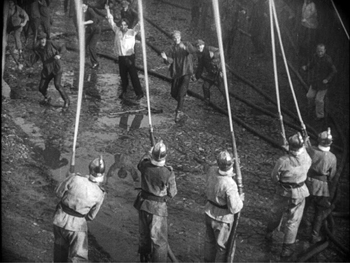

Eisenstein’s first two features bracket the year 1925. Strike was premiered in January, The Battleship Potemkin in December. The first was apparently not widely seen outside Russia until the 1970s, but the second quickly won praise around the world. Potemkin’s centerpiece, the Odessa Steps sequence, became an instant critical chestnut, proof that cinema had achieved maturity as an art. Owing nothing to theatre, this massive spectacle was as pure a piece of filmmaking as a Fairbanks stunt or a Hart shootout. But of course Eisenstein went farther.

The Steps sequence was probably the most violent thing that anybody had ever seen in a movie. A line of soldiers stalks down the crowded staircase. A little boy is shot; after he falls, skull bloodied, his body is trampled by people fleeing the troops. Another man falls, caught in a handheld shot. A mother is blasted in the gut, and her baby carriage, jouncing down the steps, falls under a cossack’s sword. A schoolmistress who has been watching in horror gets a bullet in the eye–or is it a saber slash? The sequence ends as abstractly as it began, if “abstractly” can sum up the horrific punch of these images.

The film is much more than this sequence, of course, but every one of its five sections arcs toward violence, and each payoff is shot and cut with punitive force. The mutiny itself is a pulsating rush of stunts, unexpected angles, and cuts that are at once harsh and smooth. The whole thing starts with a rebellious sailor smashing a plate (in inconsistently matched shots) and ends with the ship confronting the fleet, a challenge rendered by percussive treatment of the men and their machines.

In Strike, Eisenstein rehearsed his poetry of massacre, along with a lot of other things. Instead of rendering an actual incident, as in Potemkin, here he portrays the typical phases any strike can go through. The plot starts with injustices on the shop floor, escalates to a walkout, and then—of course—turns violent, as provocateurs make a peaceful demonstration into a pretext for harsh reprisals. Throughout, Eisenstein experiments with grotesque satire and caricature. The workers are down-to-earth heroic; the capitalists are straight out of propaganda cartoons; the spies are beastly, the provocateurs are clowns. Every sequence tries something new and bold, and weird.

The most famous passage, well-known from his writings if not from actual viewing, is the climax. Here a raid upon workers in their tenements is intercut with the slaughter of a bull. Montage again, of course, but what isn’t usually noticed is the remarkable staging of that police riot, with horsemen riding along catwalks and fastidiously dropping children over the railings. For my money, more impressive than this finale is the earlier episode in which firemen turn their hoses on the workers’ demonstration. The workers scatter, pursued by the blasts of water, until they are scrambling over one another and pounded against alley walls. This is Strike’s Odessa Steps sequence, and for throbbing dynamism and pictorial expressiveness–you can feel the soaking thrust of the water–it has few equals in silent film.

For Eisenstein, the bobbing, screaming head in my clip was the “blasting cap” that launched the Odessa massacre. Is the woman the first victim of the troops, or is her rag-doll convulsion a kind of abstract prophecy of the brutality to come? Yanked out of the actual space of the action, it hits us with a perceptual force that goes beyond straightforward storytelling. Kinetic aggression, making you feel the blow, is one legitimate function of cinema. Eisenstein is our first master of in-your-face filmmaking.

After many tries, archives have given us superb video editions of Potemkin and Strike, both available from Kino Lorber. Potemkin’s original score captures the film’s combustible restlessness. Strike seems to have been shot at so many different frame rates that it’s hard to smooth out, but the new disc makes a very good try, and it’s far superior to the draggy Soviet step-printed version that plagued us for decades.

Chamber cinema

Every so often a filmmaker decides to accept severe spatial constraints, creating what David Koepp calls “bottle” plots. Make a movie in a lifeboat (Lifeboat) or around a phone booth (Phone Booth) or in a motel room (Tape) or in a Manhattan house (Panic Room) or in a remote cabin plagued by horrors (name your favorite). In the 1940s several filmmakers were trying out a “theatrical” approach that welcomed confinement like this; Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, H. C. Potter’s The Time of Your Life, and of course Rope are examples. Today’s filmmakers are still exploring “chamber cinema.” The Hateful Eight is the most recent instance, with most of its chapters set in Minnie’s Haberdashery.