Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Don’t knock the blockbusters

Promoting Pirates of the Caribbean in Japan (By tralala.online)

Kristin here:

When was the last time you heard someone complaining about the high cost of the latest Toyota prototype? Probably not recently, since car manufacturers don’t tend to boast about how much it costs them to design a new model. In fact, I couldn’t find any information on how much the development of automobile prototypes costs. Some new models catch on, some don’t. Presumably some don’t make a profit for their makers. The same tends to be true for other big-ticket items.

In a way, a film’s negative is like a prototype. It costs a lot for a mainstream commercial film to be made, tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in many cases, before the first distribution print is struck and the first ticket sold. Yet once that prototype exists, any number of distribution prints can be struck, and a film may make back many times its negative cost.

[Added October 28: A friend of mine privy to information about car manufacturing informs me that an ordinary prototype runs $50 to 250 million. A radically new product like an electric car could run over a billion. And car companies do keep those figures secret, so it’s no wonder I couldn’t find them.

Coincidentally, $50 to 250 million is pretty much the range of budgets for mainstream commercial Hollywood features these days.

My friend told me other things about car manufacturing that make it sound as though the comparison between the two industries is a pretty reasonable one. For example, car companies can save money by releasing new, slightly modified versions of a popular model, such as the Honda Civic, rather than designing a new model from the ground up. Sort of like sequels in the film industry. More surprisingly, when car manufacturers (and some companies in other industries) make their products by outsourcing some of the components, they call it the “Hollywood model.”]

For some reason, the cost of making that negative is often public knowledge. To some extent, at least, since we all know that the budget as acknowledged by a studio may be considerably less than the actual costs. The notion that a movie set its company back by $200 million is to some extent a selling point. I’m sure that back in 1922 Universal wasn’t happy that Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives ended up costing more than a million dollars. Still, they turned it to their advantage by advertising it as the first million-dollar movie, and studios have been using the same tactic ever since.

The producers and makers of other kinds of artworks don’t tend to make such information public. How much does it cost to put on a symphonic concert or publish a book? We may hear about big advances paid to an author, but that’s basically a lump-sum against future royalties, and the author doesn’t get any more until–if ever–the advance is paid off. But how much do editorial supervision, printing, and binding set a publisher back? What kind of money goes into the creation of a large stone sculpture?

Journalists looking for a hook for an article about movies find a sturdy one in the idea that today’s film budgets are bloated. They point to classic movies of decades past that cost only a few million to make and then compare these to the loud, overblown summer tentpoles of today, with their multi-hundred-million-dollar costs. Of course this overlooks the inflation of the dollar over the years. In the 1950s the average family income was about $5000 and an average house cost under $20,000. A penny bought a gumball and could be used in parking meters. Just about everything costs a lot more now.

To be sure, other factors have raised the budgets of films well beyond what they would be through inflation alone. The key factors have been star salaries and computer-generated special effects. The latter can account for half the cost of an effects-heavy film. Beyond the negative cost, typical budgets for prints and advertising have skyrocketed.

Some people seem to see an innate immorality in today’s biggest budgets, as well as an almost inevitable lack of quality in the films that result. Here’s one of the first results of a search on “big budget movies,” from Dmitry Sheynin on suite101.com. He even makes the car comparison:

The film industry has had a good summer this year – action sequences were bigger than ever, and expensive displays of pyrotechnics and CGI showcased new and exciting ways to destroy cinematic credibility.

With the economic crisis forcing many companies to scale down or even discontinue some of their more opulent product lines (think GM), it’s comforting to know Hollywood studios are still spending inordinate sums of money producing bad movies.

I think that’s fairly typical of the grousing you find on the internet and in print. No doubt Hollywood produces many bad movies. But actually, it is comforting to know that Hollywood is still spending great sums of money, ordinate or in-, if you think of the welfare of the country as a whole.

Every now and then I’ve pondered the possibility that American movies must be one of the products, if not the product, that has the most favorable balance of trade. While the US doesn’t have quite the stranglehold on world film markets that it used to, most significant Hollywood films get exported to numerous countries. Conversely, very few films from abroad are imported, and those that come in, especially the foreign-language ones, play in far fewer theaters and sell far fewer tickets than do domestic films. In 2006, according to US census figures, foreign films took in $216 million in the U.S., while domestic films sold $7.1 billion worth of tickets. So that’s 3% of the U.S. market for imported films, which is the figure I’ve heard pretty consistently for decades.

(In passing, I note from the same report that theaters made 66% of their income on tickets, meaning that we moviegoers spend about a third of our cash on all that stuff in the lobby.)

Turns out my ponderings have been correct. On the Motion Picture Association of America’s “Research & Statistics” page, there appears the claim, “We are the only American industry to run a positive balance of trade in every country in which we do business.” (“The industry” includes both film and television.) In April the MPAA put out its latest annual report, “The Economic Impact of the Motion Picture & Television Industry on the United States.” The combined trade surplus in the moving-picture industry for 2007 was $13.6 billion, or 10% of the US trade surplus in private sector services. According to the report, “The motion picture and television surplus was larger than the combined surplus of the telecommunications, management and consulting, legal, and medical services sectors, and larger than sectors like computer and information services and insurance services.”

Lest anyone think these figures are mere industry propaganda, the MPAA’s information, though made public, is gathered for the benefit of the film studios, which collectively own the association. Screen Digest, a highly respected trade publication, summarized some of the report’s material in its September issue (“Film and TV Are Key to US Economy,” p. 265).

For better or worse, most films that are really successful abroad are big-budget items, with lots of expensive special effects and (usually) top stars. Back in 1997 people were aghast at the first $200 million movie, Titanic—until it brought in nearly $2 billion around the world. Here, in unadjusted dollars, are the top foreign earners for the past nine years (not including domestic box-office):

2008 Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull $469,534,914

2007 Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End $651,576,067

2006 Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest $642,863,913

2005 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire $605,908,000

2004 Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban $546,093,000

2003 The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King $742,083,616

2002 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets $616,655,000

2001 Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone $657,158,000

2000 Mission: Impossible II $330,978,216

Add in the DVDs and ancillary products, and the balance of trade gets even more favorable.

Yes, it may sound absurd that it requires $200 million to make a movie, especially one that gets mediocre reviews from critics and fans. Still, from a business point of view, it makes sense and it’s good for the country. It’s especially important in a period of financial crisis, when the movie industry’s income seems considerably less affected than many others. Our overall trade deficit is falling, since Americans are saving more and buying less from abroad. This year the film and television industry’s share of the surplus will presumably grow.

Apart from the balance of trade, according to the MPAA report, in 2007 the moving-image industry also employed 2.5 million people, paid $41.1 billion in wages, spent $38.2 billion at vendors and suppliers, and handed over $13 billion in federal and local taxes.

If you think the trade deficit doesn’t affect you, think again the next time you travel abroad and curse the exchange rate with the euro or the yen.

No doubt there’s a great deal of waste and slippery dealing involved in those huge budgets, but there are definite advantages that don’t get considered often enough.

I do see a lot of foreign cars on the roads.

[October 23: Coincidentally, two days ago Steven Saito posted a story on how foreign-language films that have achieved blockbuster status in the rest of the world don’t stand much of a chance of getting into the American market. He mentions the “Christmas Vacation” series that I referred to in an earlier post.]

Your tax dollars at work for Michael Bay

Kristin here–

Back in July, when I was watching films at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, I managed to catch several of the films in the Frank Capra retrospective. Two of them, Dirigible (above and left) and Submarine, were surprisingly spectacular, given that at the time Columbia was still a relatively minor studio. It wasn’t known for high-budget items. How had Capra managed such lavish-looking films?

One clue lies in the title at the beginning of Dirigible: “Dedicated to the United States Navy without whose cooperation the production of this picture would not have been possible.” Clearly the film’s second sequence (from which both frames here were taken) was shot at an actual air field with real planes and dirigibles. Many shots in the scene were taken during what seems to have been a public air show.

One clue lies in the title at the beginning of Dirigible: “Dedicated to the United States Navy without whose cooperation the production of this picture would not have been possible.” Clearly the film’s second sequence (from which both frames here were taken) was shot at an actual air field with real planes and dirigibles. Many shots in the scene were taken during what seems to have been a public air show.

I recalled that when I was growing up, every now and then a movie I saw had a similar acknowledgement. Jimmy Stewart and other stalwart stars played government employees of various sorts, with pictures of impressive buildings in Washington and superimposed titles thanking this agency or that for its aid.

It also reminded me of The Lord of the Rings. One sequence in The Return of the King, the battle before the Black Gates, was shot in an old military practice range of the New Zealand army (right and below). The country, with its lush forests and stunning mountains, is short on desolate plains. The practice range was the only suitably Mordor-like landscape that could be found.

Not only did the army clear the field of unexploded ordnance, but it supplied soldiers to serve as extras by playing the Gondorian troops. The supplement on the extended-version DVD, “Cameras in Middle-earth,” shows these troops, as well as the officers who gave them orders. Apparently the soldiers were far more capable than regular extras of marching in straight lines and less willing to merely mime fighting during the battle.

Not only did the army clear the field of unexploded ordnance, but it supplied soldiers to serve as extras by playing the Gondorian troops. The supplement on the extended-version DVD, “Cameras in Middle-earth,” shows these troops, as well as the officers who gave them orders. Apparently the soldiers were far more capable than regular extras of marching in straight lines and less willing to merely mime fighting during the battle.

All this got me to wondering how much free or cheap labor and mise-en-scene movies have received from the military over the years. Coincidentally, when I got home in July, the stack of magazines awaiting me included an issue of Variety with the headline “Tanks a Lot, Uncle Sam,” on this very subject. In the article author Peter Debruge explains a lot about the nuts and bolts of how the military’s contributions work. (As often happens, Variety opted for a more dignified title for the same article online: “Film biz, military unite for mutual gain.”)

The occasion was the release of Transformers : Revenge of the Fallen. Lt. Col. Greg Bishop, an Iraqi vet appointed last year to handle the Army’s interface with Hollywood, says of it, “This is probably the largest joint-military movie ever made.” Indeed, Transformers enjoyed the assistance of four of the country’s five military branches, with the Coast Guard being the only exception. That’s unusual, as Bishop points out. Black Hawk Down mainly called upon the Army, Top Gun upon the Navy, and Iron Man upon the Air Force.

Debruge doesn’t offer a lot of historical background, but he does mention that the Vietnam War led to a period of anti-military films. Naturally the armed forces didn’t supply aid to films excoriating them. In recent decades relations have become chummier.

What are the typical financial arrangements? According to the article,

Hollywood has every incentive to seek the military’s blessing. A film like ‘Transformers’ gets much of the access, expertise and equipment for a fraction of what it would cost to arrange through private sources, with the production on the hook only for those expenses the government encounters as a direct consequence of supporting the film (such as transporting all that megabucks equipment to the set from the nearest military base). But the production pays no location fees for shooting on military property and no salaries to the service men and women who participate in the filming, in front of or behind the cameras.

In some cases, military exercises are arranged that can be incorporated into the filming. Capt. Bryon McGarry, the deputy director of the Air Force’s PR office, is quoted concerning a day when Transformers was shooting “at White Sands when a formation of six F-16s popped flares over the set, simulating a low-level, air-to-ground attack. ‘The flyover was very much the type of training the Air National Guard does every day. Only that day, Michael Bay and his cameras had a front-row seat to the air power show,’ he says.”

This sort of military assistance isn’t available to films that shoot entirely overseas, such as Saving Private Ryan and HBO’s Band of Brothers. Hence films like Transformers and Iron Man arrange to shoot some key sequences in the American West, where deserts and mountains can convincingly double for places like the Middle East.

Even in this day of elaborate CGI special effects, many directors prefer the real thing. For one thing, it often looks more realistic, and for another, CGI is really expensive.

Naturally the military doesn’t do all this for nothing. They want influence over the way the Armed Forces are depicted. Spielberg’s War of the Worlds had military assistance. The Pentagon’s film laiason, Phil Strub, says, “The big battle scene at the end was going to be different. We just wanted the case made that the Marines understood that they were not going to prevail, but they were nobly sacrificing so the civilians in that valley could escape.”

Naturally the military doesn’t do all this for nothing. They want influence over the way the Armed Forces are depicted. Spielberg’s War of the Worlds had military assistance. The Pentagon’s film laiason, Phil Strub, says, “The big battle scene at the end was going to be different. We just wanted the case made that the Marines understood that they were not going to prevail, but they were nobly sacrificing so the civilians in that valley could escape.”

Strub also decries “the enduring stereotype of the loner hero who must succeed by disobeying orders, going outside the rules by being stupid.” As Debruge points out, “By contrast, the ‘Transformers’ sequel embodies the military philosophy that teamwork is essential to success.”

The positive depiction of the military also might attract young people to enlist—and give enemies an impression of America’s overwhelming might. McGarry says, “Recruiting and deterrents are secondary goals, but they’re certainly there.”

The idea that Hollywood often gets in bed with the military won’t come as a surprise to anyone. (For a book emphasizing this aspect of the military’s involvement in filmmaking in the U.S., see David L. Robb’s Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies.) But the extent to which even the biggest—or maybe that should be especially the biggest—Hollywood films boost their budgets in a big way is less obvious. From the standpoint of the business history of Hollywood, it’s fascinating and deserves a closer look.

Class of 1960

DB here:

By now most people accept the idea that 1939 was a kind of Golden Year of cinema. You know, Rules of the Game, Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, that movie about the Civil War, etc. TCM has even made a movie about 1939. On this site Kristin and I have talked about earlier wonder years, like 1913 and 1917. So in planning this year’s Bruges week-long Zomerfilmcollege (aka Cinephile Summer Camp), Stef Franck and I discussed building my lectures around a single year. I proposed 1941, but he countered with 1960.

1960 was a logical choice in providing spread for the whole program. At Bruges we intertwine several threads of lectures and screenings, and this year we had silent films (The Cat and the Canary, The Wind), Hollywood’s cinema of emigration (Florey, Siodmak, Ophuls, etc.), and contemporary Korean film. All in 35mm, of course. So picking 1960 filled in another area.

As so often happens, a contingent choice came to seem a necessary one. By the time I opened my mouth to introduce The Bad Sleep Well, I had convinced myself that 1960 was another watershed year. Consider these releases:

Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti), La Dolce Vita (Fellini), L’Avventura (Antonioni), Le Testament d’Orphée (Cocteau), Plein Soleil (Clement), À bout de souffle (Godard), Les Bonnes femmes (Chabrol), La Verité (Clouzot), The Bridge (Wicki), Wild Strawberries (Bergman), The Devil’s Eye (Bergman), Lady with the Little Dog (Heifetz), The Letter that Wasn’t Sent (Kalatozov), The Steamroller and the Violin (Tarkovsky short), The Teutonic Knights (Alexander Ford), Innocent Sorcerors (Wajda), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Reisz), Tunes of Glory (Neame), Sergeant Rutledge (John Ford), Psycho (Hitchcock), Spartacus (Kubrick), Elmer Gantry (Brooks), 101 Dalmatians (Disney/ Reitherman), The Magnificent Seven (Sturges), Exodus (Preminger), Home from the Hill (Minnelli), Comanche Station (Boetticher), Verboten! (Fuller), The Bellboy (Lewis), The Young One (Buñuel), TheYoung Ones (Alcoriza), The Shadow of the Caudillo (Bracho), Devi (Ray), The Cloud-Capped Star (Ghatak), This Country Where the Ganges Flows (Karmakar), Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin), The Back Door (Li Han-hsiang), Enchanting Shadow (Li Han-hsiang), The Wild, Wild Rose (Wang Tian-lin), Desperado Outpost (Okamoto), Spring Dreams (Kinoshita), When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Naruse), Daughter, Wives, and Mother (Naruse), Cruel Story of Youth (Oshima), The Sun’s Burial (Oshima), Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima), The Island (Shindo), Pigs and Battleships (Imamura), Sleep of the Beast (Suzuki), and Fighting Delinquents (Suzuki).

We didn’t show any of them.

Several factors constrained our choices, including the availability of good prints with Dutch subtitles, or at least English ones. We also didn’t want to run too many official classics. And we fudged a little for pedagogy’s sake. We had to include a Godard, but instead of À bout de souffle, we picked Le Petit soldat—made in 1960 but not released until 1963. The World of Apu was released in 1959 in India, though it made its world impact in the following year. Lola was finished in 1960 but released in early 1961. A dodge, but I wanted a Nouvelle Vague counterpoint to Godard, and it fit well with the Ophuls thread, and—well, it’s Demy. In any case, we wound up with a list of outstanding movies.

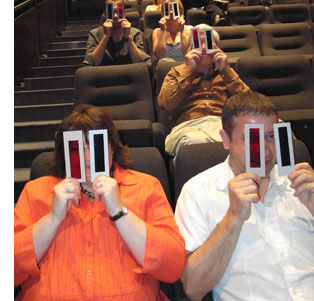

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

All in all, quite a week. My sessions ran from 9:00 AM to 12:30 or 1:00 PM, with the film embedded. After lunch, there were more talks and screenings, usually winding up at about 1:00 AM. Other speakers included Kevin Brownlow, Tom Paulus, Steven Jacobs, Muriel Andrin, Egbert Barten, and Christophe Verbiest (linking his talks on contemporary Korean film to the absolutely nuts 1960 Kim Ki-yong melodrama The Maid). The locals’ lectures were in Dutch, but these worthies are fluent in English, so sharing meals with them allowed me to catch up with their ideas.

Pegging a batch of movies to a single year can seem gimmicky, so I treated the films as exemplifying different trends, many of which started before 1960 and have continued since. I concentrated on trends within world film culture, though in several cases those were tied to still broader social and political developments. Above all, the 1960 frame allowed me to do the sort of comparative work I enjoy.

Generations

My first grouping was “Twilight of the Masters.” This allowed me to develop the idea that, remarkably, people who had started making films in the 1910s and 1920s were still active in the 1960s—and often making films that recalled their youthful efforts. Renoir revisited La Grande illusion in The Elusive Corporal, and Dreyer returned to his origins in tableau cinema through the staging of Gertrud.

In this connection, Fritz Lang’s 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, his final movie, revisits his Mabuse cycle in the way his previous films for Artur Brauner revise the “sensation-films” he wrote for Joe May (especially The Indian Tomb). Drawing on some ideas in my online essay, “The Hook,” we studied Lang’s crisp transitions between scenes. From this angle, 1000 Eyes is a sort of encyclopedia of ways you can connect scenes (visual link, auditory link, association of ideas, etc.). The transitions whip up a breathless pace and steer past some plot holes, and sometimes they generate a level of mistrust, implying story possibilities that don’t turn out to be valid.

Testament’s motif of eyes and vision became expanded to television surveillance in 1000 Eyes. There might even be an oblique connection between the Hotel Luxor’s panopticon and the rise of television ownership in Europe at the period. Here, as ever, cinema doesn’t have good things to say about TV.

Twilight of another, not quite so old master: Late Autumn by Ozu. I reviewed some features of Ozu’s style and then analyzed the film as a multiple-character drama. Ozu and his collaborator Noda Kogo split up the plot in order to present different characters’ attitudes to the central situation: the question of a daughter’s marriage. The plot ingeniously withholds information about the attitude of Akiko, the mother, by deleting certain scenes that would clarify it. Here too, the old master recalls earlier films by having characters discuss their college flirtations, which invoke scenes from Days of Youth and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?

Both Billy Wilder and Akira Kurosawa furnished me with a second generational cohort. I know, probably nobody in his right mind would see common features between these two directors. But desperation can fuel audacity. Both emerged during the late 1930s, began directing in the 1940s, and enjoyed a string of great successes in the 1950s; but both fell on harder times in the 1960s. Both became accusatory living legends, haunting local industries that had kept them from working.

Leading up to The Apartment, I considered Wilder’s contribution to two trends. First, the industry had hit the doldrums. In Europe television and new leisure lifestyles were not yet the threat they would become, but in America, the industry needed to pull its audience away from the TV set and the barbecue. Wilder proved skilful in using Hollywood’s turn to sex as the basis for his cynical comedies. The Lubitsch touch, a worldly appreciation of the oblique approach to matters of sex, was replaced by something harsher. In Wilder’s world, there are mostly sharks and shnooks, those who take and those who are taken.

Second, I situated Wilder as a leading figure in the emergence of the writer-turned-director in the 1940s (Sturges, Huston, Brooks, Fuller, Mankiewicz, etc.). This encouraged me to probe his dramaturgy, and so we analyzed the taut structure of The Apartment’s plot. It has rightly been recognized as a model screenplay, making us sympathize with a careerist covering up his bosses’ infidelities, all the while whetting our interest by shifting the range of knowledge away from the protagonist at key moments. It also displays a nice interweaving of motifs that function both dramatically and metaphorically (especially Miss Kubelik’s hand mirror). Of course at the end I had to run a clip showing the influence of The Apartment on the opening of Jerry Maguire.

By the mid-1960s, however, Wilder was pushing his luck, especially with Kiss Me Stupid. In The Apartment he wanted to make “a movie about fucking,” and he predicted that some day people would do the deed onscreen. But having glimpsed the promised land of the 1970s, he was unable to enter. Despite some worthy efforts, notably The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, he haunted Hollywood as a major director who had outlived his moment.

Human, all too human

Kurosawa’s international fame came largely through the growth of the film festival as a prime institution of international movie culture. This situation let me sketch in the importance of festivals in bringing directors like him to world recognition. (By the way, Richard Porton has just brought out an informative collection of thoughts on film festivals.) With The Bad Sleep Well, I was able to talk a bit about something that is often forgotten—Kurosawa’s efforts in social, even political cinema. From Sugata Sanshiro, a tribute to Japanese martial arts, and The Most Beautiful, the loveliest movie you’ll ever see about girls making lenses for gunsights, up through Occupation projects like No Regrets for Our Youth and Scandal, Kurosawa engaged with political subject matter. Ikiru and I Live in Fear made this side of his work even more salient in the 1950s.

The Bad Sleep Well’s attack on corporate corruption sits well with this tendency. It considers the “iron triangle” of Japanese politics, the collusion of bureaucrats, politicians, and private industry—particularly the building industry, whose livelihood depends on bids for government projects. Still, it’s hard to believe that while Kurosawa made the film, and while Ozu made the serene Late Autumn, students were fighting police in the streets over the US-Japan security treaty. That turmoil surfaced in Oshima Nagisa’s demanding and formally daring Night and Fog in Japan.

The movie is shot with Kurosawa’s usual muscularity, including virtuoso compositions in what he called, following Toland, “pan-focus.”

The film’s twists also seemed to me worth examining. The protagonist is a minor presence in the first scenes, and his reticence in the beginning is mirrored in the finale, when he simply vanishes and his pal has to tell us what happened to him. Such a daring structure, reminiscent of the abrupt midway break in Ikiru, gives the film an almost Brechtian discomfiture, as well as highlighting the secondary characters’ rather perverse reaction to the hero’s fate.

Kurosawa was widely called a “humanist” director, and this concept sheds light on what we might call the “international film ideology” pervading festivals in the 1950s. In various areas of social and philosophical thought, a notion of humanism emerged out of disillusionment with the “age of ideology” that had engulfed the world in war. Several thinkers declared that the age of religious dogma and social collectivism, either Nazi or Communist, was over. Now what mattered were the features that drew people of all societies together, and the prospect of enlightened social action based on those commonalities—tolerance, respect, and a belief that people ultimately took individual responsibility for their communities. Catholics, Communists, and people of all stripes scrambled to call themselves humanists. As Dwight Macdonald, former Trotskyite, put it, “The root is man.”

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

Film festivals embraced this universalism, pointing to the great films of Italy’s Neorealist trend as proof of cross-cultural communication. Although these films often scored specifically Italian political points, they could also be seen as human documents speaking to audiences anywhere. Who could not empathize with Ricci and his son in Bicycle Thieves (named at the 1958 Expo as the third-greatest film ever made)?

The turn to humanism helps answer a puzzling question: Why Satyajit Ray? Virtually no Europeans had ever seen a film from India. What enabled a director from this country to achieve worldwide renown? And why not other Indian directors of his era, such as Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak? All of these had to wait many years for discovery by European tastemakers.

For one thing, Ray was highly westernized himself. He was a child of the Bengali Renaissance, a virtuoso in many fields (he composed music, drew with facility, wrote detective stories and children’s books), and an admirer of European cinema. A stint assisting Jean Renoir exposed him to one of the greatest of Western filmmakers. A viewing of The Bicycle Thieves determined him to make films. He was skeptical of imitating Hollywood, which had been a prime inspiration for Hindu cinema. He criticized Bollywood’s reliance on schematic romance and musical numbers. If any Indian director was to make the move to the festival circuit, it would be him. (You can argue that other non-European filmmakers who made it into the fold were the most “western”—Kurosawa, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, etc.).

Just as important, Ray’s stories suited the humanist program. Whereas Ghatak and Sen made politically charged films, Ray concentrated on the individual. In The World of Apu, social conditions are shown, but as a background to the development of personality and psychological tensions. At the film’s start, students are holding a street march demanding political rights, but they are offscreen, a backdrop to Apu’s meeting with his old professor as he gets his letter of recommendation. What follows is a drama of artistic failure, blossoming love, and a young man’s confused growth to maturity and responsibility.

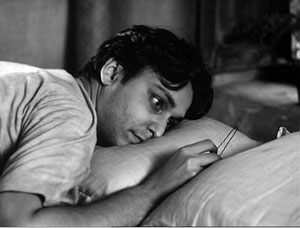

It’s a simple story, rendered lyrical through constantly developing imagery: Apu stretched out prone, the famous grimy window curtain, and a cluster of visual motifs I hadn’t noticed on previous viewing. Ray’s concise direction links the torn curtain in Apu’s room to the famous (Langian?) transition from a movie screen to a carriage window, the cluster unified by associating Apurna with male children. Thanks to Andrew Robinson’s book on Ray, we know that in the carriage scene she is already thinking of the son she will bear.

It’s easy to romanticize this handsome, happy-go-lucky hero. I think the College participants thought I was a little hard on Apu, since I treated him as far from the “conscientious and diligent” young man his professor wrote of. Surely his idealistic-novelist persona is sympathetic. But if he is to grow as the film suggests, he must have failings, and Ray shows them to us—dreamy indolence, self-centeredness, even poutiness. The film is a character study, a sort of Bildungsroman tracing how Apu learns his place in his world. Our discussion after this film was particularly rich, with one participant suggesting that in accepting his son he isn’t abandoning his art entirely, but giving it human significance: He promises to tell Kajal stories.

Ray came to directing in middle age, a somewhat rare option. So too did Gillo Pontecorvo, but the latter made many fewer films. Although Kapò, isn’t as strong a movie as our other entries, it did allow us to talk a bit about coproduction, about European cinema’s relation to World War II, and about what came to be known as the morality of technique.

European coproductions are another fundamental part of the 1960 landscape, and they illustrate how economic considerations penetrate artistic choices. (Why are American and Italian actors in the “German” film 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse? Why do we find Anouk Aimée in 8 ½ and Jeanne Moreau in La Notte? Follow the money.) For the Italian production Kapò, the primary roles are taken by an American (Susan Strasberg, playing the heroine Edith) and two French actors—the concentration camp translator played by Emmanuelle Riva and the heroic Soviet soldier played by Laurent Terzieff. The film was shot in Yugoslavia.

The story centers on a young Jewish girl who, in order to survive Nazi internment, passes herself off as a Gentile and becomes a camp commandant, whipping other prisoners into line. Other Italian films of the period, notably Rossellini’s Generale Della Rovere, were dealing with issues of conscience during the war, but Kapò was apparently the first fictional feature in Western Europe to confront the Holocaust since Alessandrini’s Wandering Jew of 1947. In 1960, Adolf Eichmann had been captured by the Mossod and stood trial the following year, and after Kapò came a few other films addressing the camps, notably Wajda’s Samson (1961) and Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1965). So the film had a strong contemporary resonance; after its US release, it would be nominated for an Oscar.

One reason Stef and I picked Kapò was the controversy around Jacques Rivette’s accusation in Cahiers du cinéma that for a particular tracking shot Pontecorvo deserved “the most profound contempt.” The film, as Rivette indicates, is dominated by an already compromised conception of realism: grimed faces, make-up that hollows cheeks, somewhat ragged clothes, moderately shabby bunks. The shot shows the body of Theresa hurled against the electrified barbed wire, with the camera coasting slowly toward it. Her silhouette is almost classically composed, with the hands artfully pivoted and standing out against the sky. For Rivette this pictorial conceit is virtually obscene.

It seems to me that Rivette’s essay sought in part to reply to those who thought that Cahiers’ policy amounted to pure formalism. In calling for an ethics of technique, Rivette argues that artistic choices which might seem to be in the service of correct politics can betray a deeper immorality: using a historical cataclysm as an occasion for a safe realism and self-congratulatory flourishes. Similar complaints could be lodged against Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg and Stone’s World Trade Center. And because for the Cahiers team artistic cinema was an expression of a creator’s vision, the morally maladroit traveling shot brands the director as a man of bad faith.

Rivette isn’t saying that film artists shouldn’t try to represent historical trauma. He simply argues that other paths could be taken. For instance, Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour acknowledge that some events cannot be encompassed by normal understanding, and the form of each film enacts an effort to understand, not a fixed conclusion. What we see in Night and Fog is “a lucid consciousness, somewhat impersonal, that is unable to accept or understand or admit this phenomenon.” For Rivette, Pontecorvo seems convinced that romantic love and self-sacrifice can overcome Nazism, albeit with some help from the Red Army. He tries to explain, even prettify, an event that cannot be understood within the usual humanistic categories.

New Wave, still new

Lola.

Godard’s Le Petit soldat is far more preoccupied with uncertainties, even confusions, than Kapò is. 1960 saw an extraordinary number of former colonies, especially in Africa, gain independence, and during that year the Algerian war of resistance was spreading to Europe. Godard’s central character Bruno is working with the OAS vigilantes dedicated to killing Algerian terrorists, but when he meets the lovely Veronica Dreyer he decides to leave politics behind and flee with her to Brazil. Perhaps “decides” is the wrong word, since his actions are impulsive: he abruptly shies away from committing a political assassination, and he abruptly abandons his colleagues. But he’s captured by FLN terrorists and, in the film’s most famous sequences, tortured. At the end, he commits the assassination, not knowing that Veronica, herself in league with the Algerians, has been captured by his pals and killed. But his final voice-over is almost a shrug, and his act of murder takes on the flavor of an existentialist acte gratuite.

Le Petit soldat doesn’t offer heroic figures, as Kapò does in Theresa and the Soviet soldier. Nor does it allow us to sympathize much with the egotistical, capricious Bruno. The texture is more disjunctive, littered with the usual digressions and citations. Since the film was shot in Geneva, there’s a persistent motif of Swissness, with citations of Paul Klee. A sneaky one I never noticed before: the seduction game Bruno plays is modeled on the three fundamental shapes in the Bauhaus basic course, which Klee taught.

Having experimented with discontinuous imagery in À bout de souffle, Godard in his second feature turns his attention to the soundtrack, creating one of the most minimalist ones I know. If Bresson whittles down his soundtrack to a spare but recognizable realism, Le Petit soldat goes a step further, scrubbing out nearly every noise until we’re almost watching a silent film. Traffic scenes lack traffic noises, with only a car horn or a bit of dialogue breaking in. One passage on a train could almost be a sound loop.

The strategy of suppressed sound is carried to a paroxysm in the torture scenes, with the clink of handcuffs and the soft tapping of typewriter keys highlighted and bits of music played spasmodically…but no sounds of pain. Only during the rushed and almost throwaway climax, is something like a plausible city ambience heard. In a dichotomy that will be familiar throughout Godard’s work, there’s a split between image (Bruno is a photographer, and in the early part of the film he takes snapshots of Veronica in her apartment) and sound (the political factions rely on telephones and tape recorders, and the OAS thugs trick their way into Veronica’s apartment through sound recording).

In all, Le Petit soldat isn’t exactly fun but it’s exhilarating in its bursts and unexpected frictions. Next time somebody tells me that Godard’s technical innovations have all become commonplace, I’ll point to this film of 1960, which would be daring and demanding if released tomorrow.

Fun, albeit grave, is what Lola is all about. It takes formal artifice far beyond realism, creating a sort of non-musical musical. (It has one number, and even that is a sketchy rehearsal.) As geometrical as a minuet, its plot plays out in a hall of mirrors, where characters share names, pasts, and sentiments. The sailor Frankie and the wandering Michel, both in love with Lola, are blonde giants. Lola is actually named Cécile, and the little girl of the same name seems in some ways an early version of her, while Cécile’s mother has a dash of Lola in her past.

Roland starts out as the protagonist, but as he warms and cools and warms to Lola, the story momentum shifts to others. There’s Lola of course, and young Cécile who strikes up a friendship with Frankie, and Cécile’s mother who yearns a bit for Roland, and Michel, who left Nantes years ago and has lived in another movie, specifically, Mark Robson’s Return to Paradise (1952). Here the structure of the plot unfolds the network of relationships among people, linked mostly by casual encounters across a few days. The last section accordingly consists of a series of farewells, as if the story can end only by breaking ties of affection.

In surveying these films, I was struck by how much most of them owed to the growth of postwar institutions of film culture, and how strong those institutions remain. Coproductions and subsidies were feeding a massive buildup of European cinema. Contrary to what you might expect, as attendance cratered from the late 1950s onward, the number of European films produced went up. The EU countries still overproduce, releasing nearly 1200 theatrical features in 2008.

Film festivals were promoting not only universal humanism; they were also packaging films under rubrics of authorship or the New XXX Cinema and the Young ZZZ Cinema. 1940s Neorealism, aka “New Realism in Italian Cinema,” seems to have been, once more, the prototype. Festivals must make discoveries and emphasize novelties. At the same period film schools taught professional standards, and film archives showed classics and gave postwar filmmakers a more secure sense of the medium’s history. Lang, Ozu, and Wilder weren’t dependent on such institutions, but younger filmmakers were. And still are.

1960 is an arbitrary data point, but it stands out as an extraordinary year for quality. In addition, picking it as a benchmark allowed me to think about some important trends of the period. What probably didn’t show through my lumbering PowerPoints, with their charts, diagrams, and frame enlargements, was how much I learned from my Bruges stay. One of the deep satisfactions of teaching is remembering, no matter how confidently you declare your claims, how much more there is to know. Of things cinematic there is no end.

We also asked participants to read Serge Daney’s essay, “The Tracking Shot in Kapò.” Daney’s elaborate exercise in autobiography, irony, and moral reflection could not be plumbed in the time at my disposal, there or here. But it did help me understand Rivette’s argument. In preparing my lectures, I also owed a debt to some excellent books, notably Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity; Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye; Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism; and Richard Brody, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. As ever, the invaluable documentation provided by the print editions of Screen Digest over the years enabled me to compile my tables of attendance, releases, and the like.

Late Autumn.

P.S. 3 Aug: Stef has posted snapshots from our Zomerfilmcollege here.

P.P.S. 3 Aug: This helpful correction from Roland-François Lack on Le Petit Soldat:

One small point: the organisation Bruno works for cannot be the O.A.S., which wasn’t active until the end of 1960.

He is working, rather, for ‘La main rouge’, a government sponsored counter-terrorist agency run by a Colonel Mercier (hence the name of Bruno’s associate).

Nice! Thanks.

Pierced by poetry

DB here:

If I had a time machine, I’d zip over to Japan between 1924 and 1940. I’d trade a year of my life here and now for a year there and then.

Why? First, because the world I see in the movies of that period holds an irresistible fascination for me. I’d like to walk through Ginza, take a train to a spa, wander through Asakusa, have tea at the Imperial Hotel, hike around the temples of Kyoto. Second, if I could go back, I could see all the films I will never see—the lost Ozus and Mizoguchis, of course, but also the films we don’t even know are important.

For Japanese cinema in the 1920s and 1930s was one of the triumphs of world cinema. That era produced not only the two directors who are arguably the very greatest but also a host of talents you can’t really call “lesser.” The bench had depth in every position.

There are good reasons for this burst of genius. Quantity affects quality, but not the way snobs think: The more movies a country makes, the more good ones you’re likely to get. Although Japan had only a little more than half the US population, before 1940 it turned out about as many features as America did.In 1936, both countries released about 530 domestic productions.

The Japanese directors who started in the 1920s had, like Ford and Walsh in their salad days, to feed this audience. We tend to forget that even exalted figures entered the industry as high-volume producers. Mizoguchi averaged about ten releases per year in his first three years, Ozu about six. Everyone’s pace slowed with the coming of sound, but the sheer volume of movies pouring from studios big and small reminds us that young directors had plenty of opportunities to hone their skills.

Probably the most startling instance is Shimizu Hiroshi. In a career that ran from 1924 to 1959, he’s credited with directing 163 films. The earliest one of his that I’ve seen is Seven Seas Part I; this 1931 feature was his seventy-fifth. “Next year,” he remarked in 1935, “I’m going to make only three films the way the company wants me to, and in exchange I can make two films that I want. I want a little more time. I’m too busy right now.” As things turned out, he signed seven films in 1936.

The great bulk of his work, 139 titles, falls before 1946. Fewer than two dozen of these seem to survive. With only about 17% of the films available, we have to keep our generalizations modest. Who knows what we would find in Love-Crazed Blade (1924) or Flaming Sky (1927) or Duck Woman (1929)? Shimizu contributed to a series, the “Boss’s Son” or “Young Master” films, of which only his first, The Boss’s Son at College (1933) seems to survive. What would we find in The Boss’s Son’s Youthful Innocence (1935) or The Boss’s Son Is a Millionaire (1936)?

Luckily, we’ve wound up with some extraordinary movies, not a clunker among the ones I’ve seen. If only a smattering of 1930s and 1940s titles is available, we should be happy that it was this smattering. Shimizu had concerns in common with Naruse Mikio and Ozu Yasujiro, but he established his own world, a rich tone, and a simple but subtle visual idiom. Along the way, he created some of the most heart-rending films in world cinema.

From the city to the spa

Shochiku talent at Izu hotspring, July 1928: Ozu Yasujiro (left), Shimizu Hiroshi (third from left), and screenwriters Fushimi Akira and Noda Kogo. Ozu and Shimizu were 23 years old.

Once more, all hail Criterion. TheTravels with Hiroshi Shimizu DVD collection released this spring includes Japanese Girls at the Harbor (1933), Mr. Thank You (1936), The Masseurs and a Woman (1938), and Ornamental Hairpin (1940). They were previously released on an expensive Japanese set (with English subtitles), but Criterion’s Eclipse series offers them at a more reasonable price, along with brief but helpful notes in English by Michael Koresky.

The collection’s title highlights the image of Shimizu that emerged in the 1980s. The films that struck Western critics then were typically shot outside the usual big cities (Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka), in the mountains and seaside towns of the Izu peninsula. John Gillett’s 1988 National Film Theatre program, the first extensive survey of Shimizu’s work outside Japan, was entitled “Travelling Man.” Not only did Shimizu take his crew on the road, thanks to the expansion of the railway system, but he also exploited what became known as his signature technique: lengthy tracking shots down a road, following characters walking toward us.

Like Ozu, Shimizu worked in modern-day genres (gendai-geki), from slapstick comedies to college sports films. Most of what survives from before 1936 are social dramas of families, friendship, and fallen women. Seven Seas (1931-1932) deals with class conflicts, as a poor girl marries into a rich family and discovers that her husband is a bounder. Eclipse (1934) centers on the failure of young people from the countryside to succeed in a recession-hit Tokyo. The title of Hero of Tokyo (1935) is ironic, in that the stepson who abides by a mother held in disgrace by her other children, winds up destroying her last scrap of respectability. In Japanese Girls at the Harbor, two schoolgirls are driven apart by one’s passion for a young man. After a violent confrontation, she becomes a prostitute and her estranged friend winds up marrying him.

The Shochiku studio deliberately pursued a female market, and these tales of family intrigue and endlessly suffering mothers, wives, and daughters offer obvious figures of sympathy. Less predictably, the films simmer with criticism of modernizing Japan. They focus on the corruption of the upper classes, the collapse of traditions in the countryside, and the uprooting of the extended family.

Most significantly, Shimizu’s films indicate quite explicitly that Japan’s growing prosperity in the 1910s and 1920s was built on the backs of the rural poor, particularly the young women who flocked to textile mills, city shops, and brothels. Like many films of his contemporaries, Shimizu’s urban films mix sentiment and comedy with a harsh appraisal of social tendencies. I’d bet that we’d find both qualities in his Stekki garu (1929), a film apparently about the current craze for “walking stick girls,” women whom men hire to accompany them on strolls.

The manager Kido Shiro summed up the Shochiku spirit in the formula “smiles mixed with tears.” Ozu offered this blend in films like I Was Born, But… (1932) and Passing Fancy (1933), but there are precious few smiles in Shimizu’s surviving early thirties output. Then he took to the road.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

The easygoing plots echo the movies’ production process. Shimizu wasn’t an obsessive planner. Whereas Ozu sketched every shot and checked the composition through the camera, Shimizu wrote minimal screenplays and seldom budged from his chair, even when the camera was traveling. He shot quickly, making up dialogue as needed and giving actors the most cursory direction imaginable. (“Run.”) Yet this wasn’t a high-pressure situation. Some days, uncertain about what to do, Shimizu would shut down the shoot and take people swimming.

Tears and smiles

I don’t want to leave the impression that Shimizu was careless; below I’ll try to show that he set himself some powerful storytelling problems. And his relaxed manner yielded a unique mixture of traditional drama and more vagrant appeals. Take Mr. Thank You, my pick for the crown of the Criterion set.

It’s a road movie, although the trip runs only twenty miles. A rickety bus winds through the mountains around the Kawazu region of Izu, an area of hot springs and tiny villages. The handsome, kindly young driver is known only as Mr. Thank You (Arigato-san) because whenever he forces walkers off the road he waves and calls his thanks. He has earned the devotion of people in the region, who entrust him with messages and duties on their behalf. On this particular day, his bus is carrying a stuffy real-estate agent; a wisecracking moga (modern girl); and a young girl whose mother is accompanying her to Tokyo, where she is to be sold into prostitution. Other passengers—wedding guests, lonely old men—get on and off in the course of the trip.

The bus stops often, and the encounters give us vignettes of the deteriorating life of the countryside. We hear of the magic attractions of Tokyo, reported by a prosperous woman about to get married. A Korean woman working on road construction asks Mr. Thank You to visit her parents’ grave, reminding us that this oppressed minority has contributed its sweat to the new Japan. Counterbalancing these stabs of pure feeling are simple running gags, such as one involving rude auto drivers who insist on passing the bus. And across the trip, the fate of the girl draws ever closer.

The moga (evidently a hooker) becomes our raisonneur, commenting on everyone’s motives, denouncing hypocrisies, flirting with Mr. Thank You, and eventually offering advice on how to save a life. Shimizu fills his film with talk and music, but in quieter moments imagery takes over: shimmering valleys below zigzag mountain roads, tunnels and forests and glimpses of steep paths along which road workers trudge. Within the bus, point-of-view is channeled fluidly. At one point we watch the moga watching the driver watching the girl. The climax of the action is simply omitted, yielding a quick, upbeat coda. In sum, Mr. Thank You radiates the cheerful, compassionate resilience of its namesake.

The mixture of tears and smiles is present as well in The Masseurs and a Woman. In Japan, blind people traditionally have taken up the trade of massage. So we start on the road, tracking back from two masseurs feeling their way along. The gags start immediately, with one praising the view, but poignancy comes just as fast: “It’s a great feeling to pass people who can see.” And again a gag undercuts it: “I bumped into some horses and dogs, though.” Shimizu sets up his brand of incidental suspense—uncertainty about matters of no dramatic moment—when the two begin to guess how many people are advancing to them. Eight and a half? We wait and, when the shot comes, we quickly count to check.

This seesawing between humor and pathos defines the tone of the whole film. Once the men arrive at the inn, we’re introduced to several guests, and a notably piecemeal plot: an aborted romance, a mysterious theft, and the attraction of one masseur toward an enigmatic woman. On the light side, students who tease the blind get extreme massage makeovers, reducing them to hobbling the next morning in a parody of the blind men’s halting gait. Shimizu assures their humiliation by head-on shots of modern girls hiking into the midst of them. And of course the blind-guy jokes multiply when several masseurs are trying to navigate a room or a street. Again, the film is over before you know it, leaving that Shimizu tang of chance encounters and what-if possibilities.

Blind masseurs play a minor role in another spa movie, Ornamental Hairpin (1941), but an almost-begun romance is there as well. Two women, Okiku and Emi, pass through an inn, and after they’ve left Emi’s hairpin jabs a young soldier’s foot. He will spend the rest of the story recovering his ability to walk. Emi returns to the inn and joins its summer guests: a cranky professor, a grandfather and his two pesky grandsons, and a married couple.

“Pierced by poetry,” says Nanmura casually about his wound, but the professor extrapolates on the phrase, trying to weave a romantic plot out of the accident. Shimizu declines to share the fantasy. A bit like Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday, the film is threaded with mundane vacation routines that become running gags, overwhelming what we expect to shape up as a courtship.

Bronzing in the sun and helping Nanmura recover his ability to walk, Emi comes to believe that she has found happiness. She has fled Tokyo and wants to start fresh. But her past, either as wife or kept woman, is kept vague. In two remarkable scenes, one a phone conversation and the other a dialogue with Okiku, her situation is sketched. We start to fear that her man will even come looking for her.

But these bits of conventional plotting are drop away among prolonged scenes of spa gossip and lazy pastimes. The most suspenseful sequences are devoted to Nanmura’s gradual recovery—a sort of deadline, since when he walks again, he will leave. If ever a climax refused to arrive, it’s during the last ten minutes or so of Ornamental Hairpin. The moments of pathos or conflict we would ordinarily see are skipped over, and the surroundings of “minor” scenes become infused with regret.

Shimizu’s ramblings through Izu didn’t lead him to abandon his probing of urban anomie, as we can see in Forget Love for Now (1937). (This must be one of the great Anglicized Japanese titles. I rank it with Blackmail Is My Life and Go, Go, Second-Time Virgin.) And at the same time he consolidated that talent for which he was best known in his lifetime: the exploration of childhood. Children in the Wind (1937), Four Seasons of Children (1939), and Introspection Tower (1941) offer unsentimental portrayal of boys’ rituals and their tenacity in the face of hardship. Shimizu founded an orphanage after the war, and he employed some of his charges in postwar films like Children of the Beehive (1948). Shochiku’s second boxed set, also with English subtitles, gives us the first three I’ve mentioned, plus the schoolteacher drama Nobuko (1940).

East meets West, and North meets South

Ornamental Hairpin.

Japanese film studios differed from their American counterparts in encouraging directors to cultivate individual styles. Kido supposedly fired Naruse by saying, “We don’t need two Ozus.” While Shimizu is not as daring or meticulous a stylist as Ozu, he managed to cultivate a visual approach that, however straightforward, was capable of delicate refinements.

In general, the Shimizus we have conform to trends in Japanese films of his period. His silent films from the years 1931-1935 adhere broadly to the Shochiku house style, using plenty of cuts and single framings of individuals. Most of the surviving silents have average shot lengths between 5 and 6 seconds, completely normal for both Japanese and US silent movies.

More remarkable is the number of dialogue titles, which make up between 24% and 44% of all shots. This would be exceptional for an American film of the 1920s. Other Japanese films, particularly Mizoguchi’s, are heavy with intertitles, but Shimizu took the trend somewhat farther. The preponderance of dialogue titles may owe something to the presence of both American and a few Japanese talking pictures at the time, which justified more spoken lines. In addition, at this period the influence of the benshi, the vocal accompanist to silent films, was waning, and the movies were becoming more self-sufficient in their narration. The hundreds of titles flashing by in Shimizu’s films would specify the scene’s action and curb the benshi’s urge to improvise.

Shimizu’s silent films that survive also contain several instances of a technique I’ve called the “dissolve in place.” The camera setup remains fixed, but one or more dissolves convey the changes in the space across a period of time. It’s commonly used to show long periods; in A Hero of Tokyo, the family’s growing poverty is shown through dissolves that gradually remove the furniture they’re been forced to sell. The technique can be seen in American silent films, a major source for most Japanese directors. Here’s a lovely example from Frank Borzage’s Lucky Star (1929), as the partly paralyzed Tim struggles to climb onto his crutches.

Shimizu often goes a little further by matching the figures precisely across a dissolve. In The Boss’s Son at College, the hero comes home but then sneaks out in his bare feet, and the dissolves concentrate on the reversal of movement, first upstairs, then down.

Again, this device was used by other Japanese directors, even Ozu in some early works, but Shimizu seems to have clung to it longer than most.

In general, Shimizu’s silent films don’t borrow his pal Ozu’s more idiosyncratic techniques. Shimizu doesn’t employ intermediate spaces to link scenes, or create elaborately disruptive transitions, or embed characters in 360-degree shooting space. Sometimes he offers mismatched eyelines in reverse shots, but these don’t usually cultivate the graphically exact alignment we find in Ozu’s editing. Still, Shimizu does often construct a scene’s space in a distinctive way.

For one thing, he will stage many scenes in long shot or even extreme long shot. Within that sort of shot, he’s often drawn to deep perspective, often with a central vanishing point. This is most apparent as a visual motif throughout The Boss’s Son at College.

More interestingly, his fascination with perpendicular depth governs staging and cutting. Imagine a line stretched straight out from the camera lens. By 1935 this lens axis has become Shimizu’s lifeline, his equivalent of the surveyor’s level. Rather than filling the foreground with a big figure or a face or prop, and rather than spreading his depth items wide across the background, he will pack the most important people along the center axis, like crystals growing out from a string. Here are instances from Japanese Girls at the Harbor and Eclipse.

Shimizu’s co-workers have testified that he cared little for the 180-degree rule. Like many Japanese filmmakers, he played fast and loose with it. Instead of an axis running between the characters, he was more concerned with the axis of the lens itself. He often respects that by cutting from one shot to a point (along the axis) 180 degrees opposite.

He also respects the lens axis by cutting straight in and out. In Hero of Tokyo, the mother learns that her husband has pulled a swindle and fled; then the officials leave her alone with her children. Shimizu simply enlarges and shrinks her systematically along the axis. He takes us to the other side of the group for the climax, when her birth children pull away from her stepson. We see no other camera positions in the scene.

This patterning is less abrasive than it might appear because intertitles are sandwiched in among these shots. It’s an intriguing strategy for thrifty filmmaking, since it requires only a rudimentary set, but it also offers a simple way to inflect the drama. Similar axial cuts, though not cushioned by titles, can be found in the shooting scene of Japanese Girls at the Harbor (which may owe something to French and Soviet cutting experiments of the period).

The depth stretching out from the camera lens is crosscut by another plane, perpendicular to it. This plane is often a patterned surface—windows, grillwork, a bedstead. Again, instead of Mizoguchi’s or Ozu’s angular foregrounds, we have an east-west axis slicing through the shot. The frames become boxes, and the characters play out their dramas within the cells of a grid, as in Seven Seas Part II and Japanese Girls at the Port.

Here again, Shimizu is relying on a device that other directors were using at the time. Many compositions of the 1930s play peekaboo with characters and setting. Here’s a flamboyant example from First Steps Ashore (Shimazu Yasujiro, 1932).

So instead of defining space through exaggerated foregrounds, plunging diagonals, or curvilinear edges, Shimizu goes Cartesian on us. His most distinctive layouts rely on two dimensions, one running straight into depth, the other running left to right. The result is a discreet, foursquare style well-suited to concise storytelling (and presumably, to turning out films quickly). Shimizu’s peers indulged in flashier shots, but his persistent choices yield a quiet variant of that continuity system that was already the lingua franca of world cinema.

Hitting the road

What about the sound films? Many Shimizu films still rely on distant planes of depth, as in this shot from Children of the Wind, when, after the father’s arrest, the boys’ buddies arrive at a far-off vantage point.

Interiors will sometimes be given the axial-cutting treatment, as in this passage from Ornamental Hairpin.

And now the crosscut horizontal plane often gets actualized as rooms gliding by the lens in lateral tracking shots. But in general, interior scenes in this 1941 film aren’t as strictly organized as in the silent films. This corresponds to a general move toward more orthodox technique in Japanese films of the period.

Something more original happens in the outdoor traveling shots. Now Shimizu’s beloved camera axis finds tangible expression in the highway. His much-vaunted tracking shots up and down the road translate the silent films’ axial depth into forward and backward movement, and characters, again organized in relation to the axis, are presented with a new simplicity and directness. Rather than being a one-off device, the road shots seem to be a development of the Cartesian coordinates that Shimizu has experimented with in the interior spaces of his silent films.

Star Athlete offers some remarkable examples of the push-pull effects built around the axis—tracking back from advancing characters, or tracking toward retreating ones. But Shimizu’s most thoroughgoing exploration of the camera axis in transit takes place in Mr. Thank You. The first thirteen shots lay out a stylistic matrix, with variants dropped in to prepare us for more compact expression later.

Shot 1: A long shot of the bus approaching.

Shots 2-4: We get the bus’s point of view of the road, with road workers in view; head-on shot of the driver calling “Thank you!” as the men step back; and the bus’s pov of the road receding, with the workers resuming. Dissolve to:

Shots 5-7: Bus’s pov of horsecart ahead; reverse angle of driver calling, “Thank you!”; bus’s pov of cart receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 8-9: Bus’s pov of men toting wood; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of men receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 10-11: Bus’s pov of women carrying bundles; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of women receding. Dissolve to:

Shot 12: Bus’s pov of chickens in road. They scatter as we get closer.

Shot 13: Long shot of bus going into the distance as we hear, “Thank you!”

The cycles move from three-shot clusters to two-shot clusters to a single shot, and a gag at that. (This driver even thanks poultry for traffic courtesy.) As another touch, Shimizu’s prized dissolves-in-place are recalled when the pedestrians approached from the back transform themselves into figures dwindling into the distance.

The same insistence on rectilinear framing takes place on the bus. Using 180-degree reversals, Shimizu creates a remarkable variety of shot scales in the cramped space of a real vehicle, always obeying his self-imposed geometry–facing either forward or backward.

As the trip gains emotional intensity, Shimizu will vary his treatment of these principles. For example, the middle section’s emphasis on forward movement will be counterbalanced near the end by a string of shots of passengers already off the bus, passing into the distance as we roll away.

In Shimizu, compact storytelling is matched by a pictorial strictness that doesn’t seem forced or stiff. After all, people do tend to line up to face one another in depth, and roads and buses do seem to run in two directions. Poetry in language demands strictures of meter, rhythm, rime, and the like, for these can pressurize expressive energies. Shimizu’s films present a disciplined lyricism: powerfully oblique emotions are shaped by simple but rich techniques of storytelling and style.

Most of my information about Shimizu’s work habits comes from essays and interviews in Shimizu Hiroshi: 101st Anniversary, ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong: Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2004). For more on Shimizu’s surviving silent films, see William Drew’s penetrating essay in Midnight Eye. Alexander Jacoby offers a sympathetic career overview atSenses of Cinema. For a filmography, see Jacoby’s A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day Stone Bridge, 2008). Isolde Standish reviews Shochiku’s studio policies in Chapter 1 of her A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film (Continuum, 2005).

Noël Burch was one of the first Western writers to appreciate Shimizu’s artistry. His indispensible 1979 book To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema is available in its entirety here. The Shimizu chapter, concentrating mainly on Star Athlete, starts here. I offer discussions of stylistic trends in Japanese cinema in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (Princeton University Press, 1988), available in toto here, and in two essays in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 337-395.

You can find passionate conversations about Shimizu and the release of these DVDs at the Criterion Forum. See especially the comments of Michael Kerpan.