Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Comic-Con 2008, Part 2: Why Hollywood cares

Kristin here-

You can’t picture the typical reader of Variety or the New York Times picking up the latest issue of Superman at the local comics shop. So why is Comic-Con, the annual confab of fans from around the world, gathering so much interest from both mainstream media and the trade press?

The obvious answer is that a growing number of megapictures and TV series are derived from superhero comics and, more broadly, fantasy and science-fiction literature. The chance to see stars and directors on panels, the first look at preview clips–these draw both fans and entertainment reporters.

Recently, the press is suggesting that Hollywood’s presence is becoming dominant at this gathering of self-professed geeks. After going to my first Comic-Con last month, I’m thinking that something else is going on. First, it’s not clear that Hollywood rules the Con. Second, and more interesting, is the question of exactly how Hollywood benefits from being there–or indeed, whether it benefits at all.

Hollywood vs. comics

Michael Cieply’s July 25 article in the New York Times is entitled, “Comic-Con Brings Out the Stars, and Plugs for Movies.” To read it, you would think that Comic-Con is a purely film event. Cieply Refers to Hugh Jackman promoting X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Mark Wahlberg presenting clips from Max Payne, the cast and director of Twilight addressing a squealing crowd of young female fans, and so on. Nary a mention of comics, video games, action figures, collectibles, original artworks, and other items being sold or promoted in the vast exhibition hall, let alone the numerous simultaneous panels going on all day upstairs and the long, sinuous lines of fans awaiting their turn for autographs from artists.

Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Geoff Boucher started his July 28 story, “This is the year they tried to take the comic out of Comic-Con.” The piece is entitled “Comic books overshadowed by the embrace of Hollywood.” A reporter could probably find plenty of people at Comic-Con to deplore the decline of comics’ representation at the event and an equal number to say that the non-Hollywood part of Comic-Con is alive and well.

Boucher quotes two of the former, who tend to be people who have been attending Comic-Con and other such events for decades. Michael Uslan, a comic-book author in the 1970s and now the executive producer of, among others, The Dark Knight, declares, “I think Comic-Con is in danger of having Hollywood co-opt its soul. It’s turning into something new, and you could really see it this year.” Robert Beerbohm, who has sold comics at every Comic-Con since it was first held in 1970, also worries about the trend: “All the Hollywood directors say that they loved comics as a kid, but now they [i.e., the comics] are being pushed off the floor. Where are the next generation of directors going to come from?”

I tend to think that young directors get influenced by such a diverse mix of popular and high cultural works that the putative lack of comics at Comic-Con won’t make much difference. Plus these days the “comics” are often graphic novels, readily available to any future director from big bookstore chains and internet sources.

Avoiding Hall H

Comic-Con has grown hugely over its nearly four decades of existence, and other media have crept in slowly. Hollywood has been prominently represented for years now. Peter Jackson promoted The Lord of the Rings there, and Adrien Brody and Naomi Watts showed up to promote his King Kong. But somehow this year the journalistic zeitgeist seems to have dictated that most writers choose to stress that Hollywood is in danger of taking over the con. Well, it makes for a dramatic story premise.

Admittedly, I’m a Comic-Con newbie. I’m sure to the old hands the creeping presence of films and TV is noticeable and perhaps worrisome. To me the big Hollywood previews were something you had to seek out, and they weren’t that easy to get to. As I mentioned in my first blog on the subject, the ground floor of the enormous, lengthy building is divided into halls A to H. A to G formed one vast open space, and an attendee could trek from one end to the other without going through doors or lobbies. Hall H, where most of the biggest Hollywood previews and panels took place, was entered from a separate door on the outside of the building. The lines to get in snaked in the opposite direction from doors A to G. Entering and exiting the exhibition hall’s lobby through one of those doors, you might not even notice the lines.

The other big “Hollywood” space is Ballroom 20, on the second floor. Anyone going from one part of the building to the other on this level, on the way to the panel rooms or the autograph area, would be likely to pass it.

My sole Hall H experience came when I attended the Terminator Salvation and Pixar previews on Saturday afternoon. The rest of my time at Comic-Con bore no resemblance to what the news stories describe. Apart from Hall H, I moved extensively around the exhibition hall, the various hallways between the panel rooms, through the “sails pavilion” and along the main lobby without having any sense of the big film and television events going on. I occasionally passed Ballroom 20 when there was a long line outside, but even then there was seldom any indication of what the people were waiting for—no banners or posters. (In general, Comic-Con has sold only very limited “signage” outside the exhibition hall. The upstairs hallways outside the panel doors were unadorned apart from small schedule boards.) In the exhibition hall I saw the studio logos hanging above their exhibit spaces and learned to skirt around them to avoid the particularly dense crowds in that area—but it was one area among many in that giant space. I seem to have experienced a different Con from the one widely reported on.

I’m not alone in thinking that Comic-Con is a giant, diverse event that simply has a big Hollywood screening room next door for those who are interested. Marc Graser, who wrote several pieces on this year’s Con for Variety, talked with its PR director, David Glanzer:

“Not every studio has a presentation every year,” Glanzer says. “It’s not an earth-shattering event. Sometimes people read too much into it.”

Yet the irony in all of this is that film- and TV-specific programming makes up less than 25% of the Con’s schedule, Glanzer says. And even on the event’s show floor, studios are overshadowed by comicbook publishers, retailers, videogames and toy companies.

The rest of the panels are educational sessions on how to break into the comicbook biz, for example, that allow Comic-Con to consider itself an educational nonprofit.

In other sources, Glanzer gives the more specific figure for film- and TV-related programming as 22%.

Those educational sessions for budding comic-book creators do make up quite a share of the program. These aren’t just how-to-draw lessons. There was a panel, “Comic Book Law School Afternoon Special: Gone But Not Forgotten!” dealing with intellectual property rights and others on the practicalities of the business. There were also 50-minute “Spotlight” sessions devoted to individual artists like Ralph Bakshi and Lynda Barry. The Eisner Awards ceremony celebrated accomplishment in the comics world.

Camping in Hall H

Why do journalists covering Comic-Con tend to stress Hollywood so much? I assume because the previews and panels are where the big stars are. They and their forthcoming films are the big news, the buzz that makes it worthwhile for magazines, newspapers, and blogs to spend the money to send their reporters or hire free-lancers. Most reporters experience that other “Hall H” con that I only visited once. I saw Anne Thompson at the “Masters of the Web” panel on Thursday morning, and she duly blogged about it. Still, most of the many Comic-Con stories posted on her Variety blog by her and other reporters were on the films and TV shows.

And why not? The big entertainment reporters get access to the major talent for short interviews, and their photographers can get up close for glamorous shots to use as illustrations. That’s no doubt what the largest portion of their readership or viewership is interested in. Attending the Con is an efficient way of generating a lot of copy.

Nevertheless, it doesn’t hurt to note that Hall H seats 6500 people, dozens, perhaps hundreds of them the entertainment reporters and bloggers. That’s out of 125,000 attendees who bought passes and probably tens of thousands more who were exhibitors, “booth babes,” or panel presenters. Granted, people circulated in and out of Hall H, though my impression is that some people stayed there much of the time. If sheer numbers of fans were to determine news coverage, the other facets of Comic-Con would get more attention than they do. But it’s the stars.

What’s in it for the studios?

The answer to that question might seem self-evident: publicity, and lots of it. The situation fuels itself. As more reporters from bigger outlets come to Comic-Con, the studios get more valuable publicity at a relatively small cost. (USA Today’s July 28 wrap-up occupied nearly a page and a half of the print edition.) And as more studios send previews and big stars, more news sources will find it worth sending their main reporters. In fact, perhaps this year the situation reached saturation. Hollywood studios filled all the possible slots in the two large halls, and in some cases big news outlets sent teams of reporters. That might be what gave both studio execs and reporters the impression that Hollywood is steamrolling the rest of the Con.

Publicity is all very well, but in the August 1 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, Steven Zeitchik questions whether it’s really worth all the fuss to preach to the converted. He notes the growth of the big studios’ efforts to impress fans: “On its face, this shouldn’t be the case. A brand’s cult following isn’t a very large number, and it’s also a group already inclined to like and spend money on a product, which by most marketing logic is exactly the group you should spend the fewest resources on.”

Sure, the Comic-Con previews may impress fans who are assumed to be tastemakers, particularly in the blogosphere. Zeitchik comments, “And if the tastemaker effect doesn’t happen, the strategy loses its teeth. One director who’s had repeated visits to Comic-Con noted just before he went to this year’s convention that ‘The total number of people in the blog world is probably only a few hundred thousand, and as much as they might hate to hear it, for most movies that’s not going to make the difference between a success and a failure.’” Zeitchik points out that the Speed Racer preview at the 2007 Con was cheered, but that didn’t mean that a lot of fans bought tickets to the film itself. The wider public stayed away.

Yet surely the studio suits know all this, and they keep providing glimpses of films and series to come. What other advantages do they perceive?

A Comic-Con preview can be a chance not only to woo fans but to get clues that might help in the general publicity campaign. Focus Features president James Shamus, who previewed Hamlet 2 at Comic-Con this year, views the process as a chance to get instantaneous feedback that might help later in promoting a film: “It’s the start of an ongoing dialog. It doesn’t just start and end there. It’s not a thumbs up or thumbs down because some guy didn’t like your poster.”

Many studio executives also still believe in the viral quality of fan buzz on the internet. Lisa Greogorian, the executive vice-president of marketing for Warner Bros. Television, assesses past years’ previews of Chuck, Pushing Daisies, and The Sarah Connor Chronicles: “We saw an immediate impact online. Word of mouth is now one individual impacting a couple hundred individuals who can impact thousands. Social networking has allowed us to empower one fan to impact thousands of potential viewers.” (Both executives spoke to Marc Graser for a July 11 Comic-Con preview in Variety.)

I emailed James, who is an old friend of ours, about the subject. He pointed out that while the blockbusters may have a pre-sold audience, smaller films like Shaun of the Dead can create momentum at Comic-Con. Moreover, there are a lot of blogs out there now, and studios monitor the more important ones to help shape their own publicity efforts.

A Comic-Con presence often, however, is not simply a matter of persuading fans to watch a film or TV series. Sometimes major negative buzz began to surround a film from a few bad online comments based solely on the Con previews. Wooing the fans with stars and footage can be a way to prevent that negativity from getting started—or a big reason for some studios not to preview a film at the Con.

One factor that doesn’t get mentioned in the press coverage of why the Hollywood studios bother with Comic-Con previews is that this event in effect provides them with huge, low-cost press junkets.

The modern press junket for a tentpole film is typically an expensive affair. The studio pays for dozens, maybe hundreds of reporters to travel to a single spot. It may be as bland as a rented hotel conference room, or it may be set in some more picturesque locale. At Cannes in 2001, New Line held a big junket for The Lord of the Rings at a hillside chateau with a spectacular view. Other junkets might be on-set, at a studio where the film is still shooting. The studios have to shell out for the reporters’ hotels, give them a per diem, and supply a reasonably impressive swag-bag. And there isn’t just one junket, but several in the course of publicizing a major release.

With Comic-Con, the studios have a whole bevy of reporters, many of them famous names in their own right, delivered to them at their employers’ expense. There are rows up front in Hall H reserved for them They sit through preview session after preview session for four days and generate a huge amount of publicity. Certainly there are expenses involved for the studios, but cutting together a few scenes or a random collection of finished shots together with a temp music track doesn’t cost a lot, and the actors don’t get paid extra for their publicity appearances. Transportation might be a relatively simple matter of sending whatever stars happen to be in Los Angeles in a limo down to San Diego. James specified to me that Comic-Con is “a very cost-effective” way of bringing the talent from a film together with fans to gauge how they interact.

I suppose for the reporters, the chance to attend what is in effect a whole passel of press junkets in one stretch saves a lot of time on airplanes.

Oh, yes, the comics

Some stories do stress the comics. Not surprisingly, Publisher’s Weekly printed an excellent preview that talked about the comics and graphic-novels companies that would be present. The author also pointed out that the connections between comics and films are getting closer, what with all the adaptations that have been made or are in the pipeline. The article quotes comics author Steve Niles (30 Days of Night) as saying, that the Con is “crawling with producers now, which means some of the up-and-comers have a chance to get someone to notice their book.”

USA Today ran a story that analyzed the recent trend toward comics-based movies quite carefully. Author Scott Bowles discusses the trends toward darker stories and heroes who aren’t conventional heroic, such as Hancock and the Watchmen. The story also discusses whether this trend indicates that the superhero genre is nearly over or just reaching a more imaginative stage.

Bowles also points out that the traditional notion of the Con as largely frequented by fanboys is no longer accurate. This year nearly 40% of the fans were female.

Costumes and the press

Naturally journalists with cameras make a beeline for costumed Comic-Con attendees. They stand out in the crowd, they seem to these journalists to epitomize the fan sensibility, and they are delighted to pose at any length for photos. (Anne Thompson’s blog has a sampling posted.) Many of them have very impressive costumes and put on little skits or tableaux in the hallways. There’s a “masquerade” competition with cash (up to $150) and merchandise prizes on Saturday night.

[Added August 11: David Glanzer kindly emailed me to compliment me on this entry. He informed me that roughly one percent of fans attending Comic-Con come in costume. Not that either he or I have anything against costumed fans. On the contrary, I enjoyed seeing them, and obviously they were having a terrific time. But some journalists adopt a definitely mocking tone, and even those who are respectful tend to mislead the public about the attendees at the Con in general.]

But most attendees are content to declare their interests on their T-shirts, as I did, and their shopping bags. Again, that doesn’t make for good copy or images. The photos at top and bottom show what I saw much of the time in the exhibition hall. These people are not likely to be approached by journalists, though these days they might have a questionnaire thrust into their hands by a sociologist or ethnographer trying to figure out what makes fans tick.

If you have to ask …

For my account of things and event relating to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings at Comic-Con, see here.

Games cinephiles play

From DB:

The Europeans have long been fascinated by the subject of cinephilia. The French supplied not only the word but the most outstanding instances, from the founding of Cahiers du cinéma to the passions of the Nouvelle Vague. (1) In the last decade particularly, French critics have often returned to the subject–worrying, for instance, that home video might have changed or even decimated cinephilia–and this has led critics from other countries to join in.

I was reminded of how strongly the idea persists when, at Il Cinema Ritrovato this year, I was invited to sit in on one of several lunches at which critics and historians talked about the subject. The discussion consisted mostly of recollections of the guests’ first encounters with cinema, of the films that affected them most powerfully, of the film-related activities they engaged in during their salad days. Some of us hadn’t done this exercise in autobiography before, but others had had practice. Jonathan Rosenbaum and Eric de Kuyper had both written a fair amount about the sources of their affinity for film. (Sometimes I feel I remember Jonathan’s life better than my own.)

What is cinephilia? Literally, the love of film. But everybody likes, even loves film, no? The term “cinephilia” connotes an overwhelming passion for film, even an obsession about it. And not just particular films. I meet civilians all the time who are devoted to their favorites—The Godfather, The Princess Bride, The Matrix. But they’re not cinephiles. So is it just a matter of quantity? Is it just that the cinephile enjoys a great many movies? Partly, but there’s still more to it.

The cinephile displays symptoms of cinemania, as chronicled in the film of the same name. If you haven’t seen it, Cinemania tracks five people who organize their lives around watching movies. As I watched it, some of my reactions ran to “Wow, that is really hard-core,” but every now and then I thought: “Well, that‘s not so weird. I do that.” So I see the similarities.

Most obviously, both the cinephile and the cinemaniac show symptoms of compulsiveness. Each one makes lists, checks off titles seen, plans a day of moviegoing with care. When visiting a new city, s/he first scans the cultural scene for what’s playing. Both types of film lover are strict—no pan-and-scan, no colorization, no dodgy projection. Either type might have a weblog or a diary or just patient friends. If s/he has friends.

But I do see differences. For one thing, most cinemaniacs like only certain sorts of movies—usually American, often silent, sometimes foreign, seldom documentaries. Do cinemaniacs line up for Brakhage or Frederick Wiseman? My sense is not.

Cinephiles by contrast tend to be ecumenical. Indeed, many take pride in the intergalactic breadth of their tastes. Look at any smart critic’s ten-best lists. You’ll usually see an eclectic mix of arthouse, pop, and experimental, including one or two titles you have never heard of. Obscurity is important; a cinephile is a connoisseur.

The real crux, I think, is this. The cinephile loves the idea of film.

That means loving not only its accomplishments but its potential, its promise and prospects. It’s as if individual films, delectable and overpowering as they can be, are but glimpses of something far grander. That distant horizon, impossible to describe fully, is Cinema, and it is this art form, or medium, that is the ultimate object of devotion. In the darkening auditorium there ignites the hope of another view of that mysterious realm. The pious will call Cinema a holy place, the secular will see it as the treasure-house of an artform still capable of great things. The promised land of cinema, as experimentalists of the 1920s called it: that, mystical as it sounds, is my sense of what the cinephile yearns for.

This separates the cinephile from the lover of novels or classical music. They love their art, I suspect, because of its great accomplishments. Who with literary or musical taste would embrace the subpar novel or the apprentice toccata? But cinephiles will watch damn near anything looking for a moment’s worth of magic. Perhaps this puts cinephiles closer to theatre buffs. They too wait hopefully for the sublime instant that flickers out of amateur performances of Our Town and Man and Superman.

That’s also why I think that the cinephile finds the desert-island question so hard to answer. What movies would I want to live with for the rest of my life? All of them, especially the ones I haven’t yet seen.

Another difference: Fussiness and solitude. The cinemaniac has a favorite seat, even if it’s way off to the side. To secure it, the cinemaniac shows up early and tries to be first in line. Your average cinephile isn’t so picky about where to sit, and so may slip in at the last minute. While waiting for the show to start, the cinemaniac seldom acknowledges others; a book is the faithful companion. But the cinephile is, if not extroverted, at least gregarious and wants to talk with other cinephiles.

What sort of talk? I’m glad you asked.

Cooperative games: Playing well with others

Jules and Jim leave a screening.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: Yeah, great!

Jules: Well, see ya.

Jim: Yup, later.

This is the minimal, polite cooperative game. When the energy level is cranked up, you get something like this.

Jules: Great movie! I love M*x *ph*ls.

Jim: God, yes. Those camera movements knock me out.

Jules: But then there’s R*n**r too!

Jim: God, I love R*n**r. And M*z*g*ch*–there’s a man for camera movements.

Jules: My man! M*z*g*ch* is just terrific.

This can go on indefinitely. To get a sense of how special cinephiliac enthusiasms are, imagine littérateurs talking about Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, and iambic pentameter in these terms.

A cooperative game can go a little further.

Jules: What a fantastic movie!

Jim: Yes, fabulous. M*nn*ll* movies get better and better, the more you see them.

Jules: I completely agree—except for The S*ndp*p*r.

Jim: Yeah, that’s kind of weak, but it’s got some good points.

Jules: Really? I haven’t seen it in twenty years.

Jim: I have a pretty good copy off Turner. Let me dub it and send it to you.

Jules: That’s really nice of you.

Even if Jim never sends the disc, he has played the game charitably and Jules has accepted graciously.

Jim: What a terrific movie.

Jules: I wasn’t so impressed. Want to grab a coffee and talk about it?

Jim: Good idea!

This is probably the optimal way to play Cinephilia cooperatively.

But many cinephiles want to play rougher. The extreme option is flat-out disagreement, usually expressed in terms that bluntly doubt the competitor’s sanity, intelligence, or good will. I won’t dwell on this abrasive strategy here. There are stealthier ways to go.

Competitive games: Upsmanship

Jules and Jim leave a screening.

Jules: I loved it. What did you think?

Jim: Well. . . Have you seen earlier films by H*ng S*ng-s**?

This is an opening gambit. If Jules says no, then Jim can say something like: It’s really one of his weaker movies or His films get worse and worse. Now Jules would be playing defense, on unfriendly terrain. If he hasn’t seen the other films, the comparison-strategy will be his undoing. So:

Jules: Yeah, I’ve seen all of them. I thought that this was a strong one.

Now Jim can fight to at least a draw. Maybe Jules was bluffing and hasn’t seen all the films; or maybe Jim remembers them better.

Jules has used what we can call the breadth strategy: I’ve seen more than you. This need not bear only on other films; it can work along other dimensions.

Jim: I was so impressed by St*g* Fr*ght, but I never heard anybody refer to it among H*tch’s best.

Jules: Well, in the critical literature it’s often considered a masterpiece. Have you read . . .?

Or:

Jules: Yes, it’s a great movie, but what a terrible print! The reel ends were chopped off, and there were splices all the way through. I remember seeing a pristine print at the Director’s Guild Theatre. [The haymaker:] Jane Wyman was there to talk about it.

With a silent film you can extend the strategy to multiple versions: I remember a MoMA screening that ran an extra half-hour or The DVD from Austria fills in the missing scenes with stills. Oh, you didn’t know there were missing scenes…? Jim doesn’t have many options here.

If Jules sticks to the breadth strategy, this can go on quite a while. Once I got cornered after a friendly critic asked me about 1930s Ozu. Yes, I’d seen them all. Naruse? Yes. Shimizu? Quite a lot. I held my own, but then he changed up his pitching rhythm: “And how about 1930s English comedies? No? Oh, you must see them—they’re wonderful.”

Akin to the breadth approach is the longevity strategy, aka I was here first. We old guys like to use this. It can get pretty brutal.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: First time you saw it?

Jules: Um, yeah.

Jim: It gets better on multiple viewings. I liked it when I saw it in 1971. In fact, I liked it so much I wrote about it for Sight & Sound. Let me send you a copy of the essay.

Jules: Um…thanks…

There’s also the depth strategy. Here the player goes very specific, invoking details that suggest sensitivity and massive memory power.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: You said it. I especially liked the scene when the camera tracks sideways, picking up the back of the guy who’ll turn out to be so important at the end.

Jules: Yeah. . . Actually, I didn’t notice that.

Jim: You didn’t? Gosh, that’s the key to the whole movie. It sets up the last scene beautifully. Of course there’s also that killer opening line.

Jules (who doesn’t even remember the opening scene): Yeah, that was really effective.

Jules lost, and Jim knows it.

Another strategy relies on eloquence. Both Jules and Jim are evenly matched on range and depth and longevity, but Jules has the edge in using language.

Jules: What’d you think?

Jim: I liked the opening shot.

Jules: Me too. Most long-take crane shots look pretentious, but this one had a sinuous grace that’s hard to achieve on location.

This strategy can be amped up into philosophical disquisition that usually sounds better in French but can occur in English too.

Jim: I just don’t see why people take W**dy *ll*n seriously. Cr*m*s *nd M*sd*m**n*rs is heavy-handed in its metaphors of blindness and sight.

Jules: What’s remarkable about W**dy is the way his metaphors hover between the banal and the extraordinary. They’re at once familiar and unfamiliar, both distant and near. They lie, we might say, in a zone of zigzag indeterminacy.

Okay, this plays better on the page than in conversation, but I have encountered it occasionally face to face. It’s a hard serve to return. Resorting to I just don’t know what that means usually makes you look dumb, whereas Do you buy effluvia like that in ten-gallon drums? would be considered hostile.

Then there’s the insider strategy.

Jules: Solid movie, but a little choppy.

Jim: Yeah, the director sent me a rough cut on DVD a few months ago. Looks like she dropped a lot. And the producer’s son attempted suicide, which probably screwed up the whole project.

Advantage: Jim.

What we talk about when we talk about talk

I’ve taken face-to-face dialogue as my default, but you can find these strategies at play in those monologues we call film criticism. The maneuvers are usually a bit subtler, though. For instance, the longevity strategy often surfaces guilelessly, as a homey touch of autobiography. Some critics like to start their pieces with a chatty narrative recounting how they learned about this film—that is, way before you, loser.

And of course these strategies are all over forums and chat threads. In those settings the players can be anonymous and can loose a barrage that they might hesitate to launch in person.

One last question: Are these games for boys only? Is cinephilia itself defined as a guy’s thing? In my experience, no, not wholly; but mostly. Have women opted out? Do they play it differently? I might have to recast my dialogues in order to include Catherine.

In any case: Substantively speaking, this is a minuet. Jules’ claims might be right or wrong. Ditto Jim’s. Any of the competitive strategies can produce information and ideas. We just have to remember that lots of life is about playing games.

And remember that you can always change the subject to sports or rock and roll. No one-upsmanship in those domains!

(1) Antoine de Baecque’s entertaining La cinéphilie: Invention d’un regard, histoire d’une culture 1944-1968 (Paris: Fayard, 2003) has become the standard history of this tendency.

Times go by turns

Kristin here—

Last week during the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference here in Madison, I got to talking with Prof. Birger Langkjær of the University of Copenhagen. He asked me some questions about the concept of “turning points” in film narrative as I had used it in my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Specifically he wondered if turning points invariably involve changes of which the protagonist or protagonists are aware. The protagonist’s goals are usually what shape the plot, so can one have a turning point without him or her knowing about it?

I couldn’t really give a definitive answer on the spot, partly because it’s a complex subject and partly because I finished the book a decade ago (for publication in 1999). It seemed worth going back and trying to categorize the turning points in films I analyzed. Describing those turning points more specifically could be useful in itself, and it might help determine to what extent a protagonist’s knowledge of what causes those turning points typically forms a crucial component of them.

Characteristics of turning points

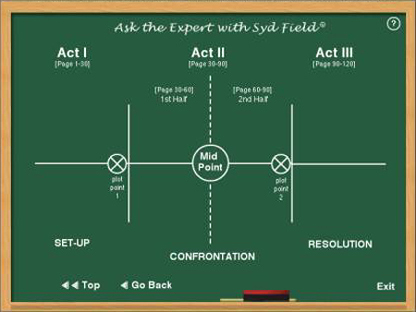

Most screenplay manuals treat turning points as the major events or changes that mark the end of an “act” of a movie. Syd Field, perhaps the most influential of all how-to manual authors, declared that all films, not just classical ones, have three acts. In a two-hour film, the first act will be about 30 minutes long, the second 60 minutes, and the third 30 minutes. The illustration at the top shows a graphic depiction of his model, which includes a midpoint, though Field doesn’t consider that midpoint to be a turning point.

I argued against this model in Storytelling, suggesting that upon analysis, most Hollywood films in fact have four large-scale parts of roughly equal length. The “three-act structure” has become so ingrained in thinking about film narratives that my claim is somewhat controversial. What has been overlooked is that I’m not claiming that all films have four acts. Rather, my claim is that in classical films large-scale parts tend to fall within the same average length range, roughly 25 to 35 minutes. If a film is two and a half hours rather than two hours, it will tend to have five parts, if three hours long, then six, and so on. And it’s not that I think films must have this structure. From observation, I think they usually do. Apparently filmmakers figured out early on, back in the mid-1910s when features were becoming standard, that the action should optimally run for at most about half an hour without some really major change occurring.

Field originally called these changes “plot points,” and he defined them as “an incident, or event, that hooks into the story and spins it around into another direction.” Perhaps because of that shift in direction, these moments have come more commonly to be called “turning points.” But what are they? Field’s definition is pretty vague.

In Storytelling I wrote, “I am assuming that the turning points almost invariably relate to the characters’ goals. A turning point may occur when a protagonist’s goal jells and he or she articulates it .… Or a turning point may come when one goal is achieved and another replaces it.” I also assumed that a major new premise often leads to a goal change (p. 29). “Almost invariably” because I don’t assume that there are hard and fast rules. As with large-scale parts, my claims about other classical narrative guidelines aren’t prescriptive in the way that screenplay manuals usually are.

To reiterate a few other things I said about turning points. They are not always the same as the moments of highest drama. Using Jaws as my example, I suggest that the moments of decision (not to hire Quint to kill the shark and later to hire him after all), rather than the big action scenes of the shark attacks, shape the causal chain (p. 33).

Not all turning points come exactly at the end of a large-scale part of the film (an “act” in most screenplay manuals). A turning point might come shortly before the end of a part, or the turning point may come at the beginning of the new part (pp. 29-30). The final turning point that leads into the climax comes when “all the premises regarding the goals and the lines of action have been introduced” (p. 29).

Most screenplay manuals consider goals to be static. To me, “Shifting or evolving goals are in fact the norm, at least in well-executed classical films” (p. 52). This doesn’t mean that the goal changes at every turning point. Instead, the end of a large-scale part may lead to a continuation of the goal(s) but with a distinct change of tactics (p. 28).

One big advantage of talking about different types of turning points is that it allows the analyst to see how the different large-scale parts function. A well-done classical film doesn’t just have exposition and a climax with a bunch of stuff in the middle. (Field calls that long second act the “Confrontation” in the diagram above.) I believe that once the setup is over, there is a stretch of “complicating action,” which often acts as a sort of second setup, creating a whole new situation that follows from the first turning point. The third part is the “development,” which often consists of a series of delays and obstacles that essentially function to keep the complications from continuing to pile up until the whole plot becomes too convoluted. The development also serves to keep the climax from starting too soon. The third turning point is the last major premise or piece of information that needs to be set in place before the action can start moving toward its resolution in the climax.

David uses this approach to large-scale parts in his online essay, “Anatomy of the Action Picture,” which discusses Mission: Impossible III.

TYPES OF TURNING POINTS

Returning to some of the examples I used in Storytelling, let’s see what sorts of changes their turning points involve. In most of these cases, the protagonist is aware of what is happening, but there are some exceptions or nuances.

1. An accomplishment, later to be reversed

Top Hat: end of setup, Jerry and Dale fall in love, but she soon conceives the mistaken idea that he is married to her best friend. (p. 28)

Tootsie: end of setup, Michael gets a job, but the results will throw his life increasingly into chaos. (p. 60)

Parenthood: end of complicating action, the parents seem to be making progress in solving their problems. (p. 268)

2. Apparent failure, reiteration of goal

The Miracle Worker: end of development, parents remove Helen from cabin, Anne states goal again. (p. 28)

The Silence of the Lambs: turning point comes at beginning of development, Chilton makes Lecter a counter-offer, removing him from the FBI’s charge. The FBI’s tactic has failed, but soon Clarice visits Lecter to pursue her questioning. (p. 123)

Here’s a case where we don’t see Clarice learning about Chilton’s treacherous undermining of the FBI’s efforts. A few scenes later she simply shows up to visit Lecter, and we realize that she has not given up her goal of getting information from him. Clearly a turning point can occur without the main character’s knowledge, but he or she will usually learn about it shortly thereafter.

Groundhog Day: end of development. Failure to save old man. No reiteration of goal, which is implicitly that Phil will continue to improve himself. (p. 147)

2a. Failure, new goal

Amadeus: end of complicating action, Salieri declares that he is now God’s enemy and will ruin Mozart. (p. 195)

Amadeus is an example of what I call a “parallel protagonist” film. Here Salieri is aware of his own decision, but Mozart never learns that his colleague hates him so. Parallel protagonists have separate goals, but they need not be aware of each other’s goals. The same would be true in a film with multiple protagonists, to the extent that they have separate goals.

2b. Failure, lack of goal

Groundhog Day: end of complicating action, suicidal despair. (p. 144)

Amadeus: end of setup, Salieri humiliated by Mozart, conceives strong resentment but no specific goal. (p. 191)

Parenthood: end of development, the parents are all resigned to their failures. (pp. 275-76)

3. Major new premise, reiteration of strategy

Witness: end of complicating action, Carter tells Book to stay hidden. (p. 29)

The Wrong Man: end of complicating action, Manny is freed on bail; he has the chance to try and prove his innocence. (p. 39)

Terminator 2: end of development, Sarah, Terminator, and John steal chip from Cyberdine, continue in their attempt to destroy it. (p. 42)

Amadeus: end of second development, Constanza leaves Mozart, allowing Salieri the access that will permit him to fulfill his goal of killing his rival. (p. 205)

4. Protagonist/Important character makes a decision, then changes or modifies goal

Little Shop of Horrors (1986): end of complicating action, Seymour agrees to kill someone to feed blood to Audrey II. (p. 29)

The Godfather: end of development, Michael says family will go legit, asks Kay to marry him. (p. 30)

Casablanca: end of complicating action, Rick rejects Ilsa’s account of her relationship with Victor. (p. 32)

The Producers: end of setup, Leo decides to join Max in committing fraud. (p. 38)

Tootsie: end of complicating action, Michael decides to start improvising Dorothy’s lines, setting up “her” success. (p. 64)

Back to the Future: end of development. Martie decides to leave a message for Doc warning him about the Libyan attack; the result is to save Doc from being killed. (p. 94)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of setup, Roberta apparently decides to pursue Susan, change her boring life. (p. 166)

Such decisions obviously form the basis for turning points fairly frequently, and by definition the protagonist is aware of what is happening.

5. Major Revelation, new goal or move into climax

Witness: end of setup, Book is told the killer is a cop, changes tactics, flees. (p. 28)

Witness: end of development, Book learns partner has been killed, realizes he must act. (p. 29)

The Bodyguard: end of development, revelation of Nikki as villain, attack on house, death of Nikki. (p. 31)

Terminator 2: end of setup, John discovers the Terminator must obey him, sets goals of protection without killing and of rescuing Sarah from the asylum. (p. 41)

Terminator 2: end of complicating action, Sarah realizes that the war can be prevented, conceives goal of killing Dyson. (p. 42)

Tootsie: end of development, Michael’s agent tells him he must get out of playing Dorothy without being charged with fraud. (p. 69)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of setup, Clarice finds the body in the warehouse and realizes that Lecter is willing to help her. (p. 115)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of development, Clarice and Ardelia realize “He knew her,” the clue that will lead to the solution. (p. 126)

Alien: end of development, revelation that the “company” and Ash are prepared to sacrifice the crew; will lead to decision by survivors to abandon the ship and save themselves. (p. 299)

Such revelations usually involve the protagonist knowing what is happening, but I believe there are exceptional cases where the viewer learns something that the protagonist does not. This kind of revelation often involves either villains turning out to be allies or apparent allies turning out to be villains.

Take the case of Demolition Man. At 54 minutes into the film, about nine minutes before the end of the complicating action, the audience learns that the apparently benevolent Dr. Cocteau (Nigel Hawthorne), who has developed the new pacifist society of Los Angeles, is a ruthless villain. This moment isn’t the turning point that ends the complicating action; I take that to be the escape of the “Scraps,” the rebels who oppose Cocteau, from their underground prison. Most of those nine minutes consist of the hero, John (Sylvester Stallone) meeting Cocteau and going out to dinner with him. John shows signs of strongly disliking the new society, and he refuses to kill the rebels when they escape. Still, there is no sign that he considers Cocteau a villain. Rather, John thinks of himself as a misfit and expresses a desire to leave the new Los Angeles. The turning point that ends the complication depends on his assumption that Cocteau on his side, even if John considers the leader’s bland society to be unattractive.

The development portion is full of typical delays: the scene of John visiting Lenina Huxley’s (Sandra Bullock) apartment, where she invites him to have virtual sex, and the following scene of John exploring the odd, modernistic apartment assigned to him. At 74 minutes in, or about six minutes before the end of the development, John begins to learn of Cocteau’s true nature. He confronts Cocteau in the latter’s office and nearly shoots him. The scene where John tells the members of the police department who remain loyal to him that they will invade the underground prison to capture Cocteau’s violent agent, Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes) marks the end of the development, with a new, specific goal determining the action of the climax.

Here is a case where for a significant portion of the narrative the protagonist remains ignorant of something that the audience has been shown. Even here, however, John displays a dislike of Cocteau and what he has done to Los Angeles society. Classical films seem disinclined to show their heroes as thoroughly deluded. John’s underlying decency and common sense make him ready to distrust a leader whom everyone else, including Lenina, admire.

6. Enough information accumulates to cause the formulation of goals

Back to the Future: end of complicating action, goals of synchronizing with lightning storm, getting Marty’s father and mother together at dance. (p. 90)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of complicating action. Information about gangsters and growing attraction to Dez lead to convergence of Roberta’s goals. (p. 170)

Parenthood: end of setup, in this case with multiple goals formed for four separate plotlines.

7. A disaster, accidental or deliberate, changes the characters’ situations/goals

The Wrong Man: end of setup, Manny is mistakenly arrested. (p. 39)

Jurassic Park: end of complicating action, Nedry shuts down the electricity grid of the park, letting the dinosaurs loose. (p. 32)

Jaws: end of complicating action; the attack involving his son makes Brody force the mayor to accept his original, thwarted tactic of hiring Quint. (p. 34)

Alien: end of setup, facehugger attaches itself to Kane. The goal conceived shortly thereafter is to investigate it and save him. (p. 292)

Alien: end of complicating action, alien bursts from Kane’s stomach; goal becomes to save the crew and ship. (p. 295)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of development, Roberta’s arrest leads to a low point, and she opts to turn to Dez for help. (p. 172)

Amadeus: end of first development, death of Leopold, which Salieri later exploits in his plot against Mozart. (p. 201)

The Hunt for Red October: end of complicating action, Ramius realizes he has a saboteur aboard and needs Ryan’s help; Ryan starts planning actively to help him. (p. 233)

8. Protagonist’s tactics are blocked or he/she is forced to use the wrong tactics

Jaws: end of setup, Brody’s desire to hire Quint rejected. (p. 23)

Back to the Future: end of setup, Doc sets time machine’s date; after new large-scale section begins, attack by Libyans accidentally sends Marty back to 1955. (p. 85)

Groundhog Day: end of setup, Phil trapped in repeating time, goal of becoming a network weather forecaster destroyed. He soon opts for irresponsible self-indulgence. (p. 139)

9. Characters working at cross-purposes resolve their differences

Jaws: end of development, the three main characters bond, allowing them to cooperate to kill the shark. (p. 35)

The Hunt for Red October: end of development, Ramius and Ryan make contact, with Captain Mancuso’s help, they start working together. (p. 237)

10. A supernatural premise determines a character’s behavior

Liar, Liar: end of setup, Max wishes that his father would have a day where he is unable to tell a lie. Also end of complicating action, where Max fails to cancel the wish. (p. 38)

11. The protagonist/major character succeeds in one goal, allowing him/her to pursue another

Liar, Liar: end of development, Fletcher wins his court case, freeing him to try and regain his wife and son. (p. 39)

The Hunt for Red October: end of setup, Ramius learns that the silent feature of his new submarine works; he apparently intends some sort of attack on the US but is in fact plotting an elaborate ruse to defect. (p. 225)

These examples suggest that protagonists usually do know about the major events that form turning points, or they learn about them shortly after they occur. The main exception would seem to be when there are two major parallel characters, one of whom is to some extent villainous, as in the case of Amadeus, where one of the characters is duped. This reminds me of The Producers, where Max and Leo leave the theater early, convinced that they have succeeded in their goal of creating a box-office disaster. Lingering in the theater, the narration allows us to see the transition from audience disgust to fascination. Only after the audience comes into the bar where the two partners are celebrating do they realize what has happened (“I never in a million years thought I’d ever love a show called Springtime for Hitler!”) To understand the irony and/or humor in such situations, the film spectator must at least briefly know more than the main characters do.

The examples also confirm that character goals seldom endure unchanged across the length of a film. Revelations, decisions, disasters, supernatural events, and presumably others kinds of causes frequently cause major shifts in characters’ goals or at least in the tactics they employ in pursuing them. Even in what seems like a fairly straightforward thriller like Alien, the crew’s assumptions that they must loyally protect their spaceship are completely reversed at the end of the development, and the narrative turns into an attack on corporate greed and ruthlessness. Whatever one thinks of classical Hollywood films, they are usually more complex than the three-act model allows for.

Note: My title comes from Robert Southwell’s poem of the same name.

[July 11: Jim Emerson has made some insightful comments on this entry on his Scanners blog.]

American (Movie) Madness

Grover Crisp and Lea Jacobs outside the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

DB here, again:

He holds sway over thousands of movies and the transfer of hundreds of DVDs. At home he has a high-definition set, but he gets local channels on a rabbit-ears antenna. If that isn’t a working definition of a Film Person, I don’t know what is.

Over the years our UW Film Studies area has hosted many visiting Film Persons, including archivists Chris Horak, Mike Pogorzelski, Joe Lindner, Schawn Belston, and Paolo Cherchi Usai. (1) Being a department centrally interested in film history, we’re eager to screen recent restorations and learn the ins and outs of film archivery.

This year our Cinematheque screened several Sony/ Columbia restorations, running the gamut from Anatomy of a Murder to The Burglar. We wound up our series, and our season, with a stunning print of Frank Capra’s American Madness (1932). To conclude things with a bang, Lea Jacobs, Karin Kolb, and Jeff Smith brought Grover Crisp, Sony’s Senior Vice President of Asset Management, Film Restoration, and Digital Mastering.

Kristin and I had met Grover at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, and after hearing him introduce some restorations, we knew he had to come to Madison. It was a Bologna screening of American Madness that convinced me that we had to show this sparkling print on our campus. Fortunately for us, Grover squeezed a Madison visit into his schedule and suffered the caprices of American Airlines’ delays. We had about two days of his company.

It was a great learning experience. On Thursday 8 May he addressed our colloquium, where he showed two shorts: a 1933 Screen Snapshots installment explaining the process of motion picture production, from script to final product, and a trim 75-second short by his colleague Michael Friend tracing the evolution of filmmaking technology. On Friday Grover introduced American Madness and took questions.

Just a note about terminology: Archives engage in both film preservation and film restoration. Preservation means, as you’d think, saving films for the future. This involves maintaining the materials (prints, negatives, camera material, sound tracks) in surroundings that minimize harm and deterioration. Restoration demands more resources. It involves trying to create an authoritative version of the film as it existed in some earlier point in history. But that’s a complicated matter, as we’ll see.

Archives and assets

Grover brings a Film Person’s sensitivity to the mission of film preservation. What does that mean? For one thing, he takes the long perspective. Film archivists think about how to store and maintain films for decades, even hundreds of years. In an industry geared to short-term cycles, booms and busts and jagged demand curves, a commercial archivist like Grover, or Schawn of Fox, has to reconcile traditional museum standards with market demands, strategic release considerations, and current studio policies. In short, he has to think both about saving the film for a century and about hitting a DVD street date.

Grover explained his obligations at Sony Pictures Entertainment. He manages all film and television materials. That means preserving everything for any future use and restoring some items for video and theatrical screening. It also means that he keeps abreast of current TV and film productions. This gives him a chance to “embed archival needs” into production and postproduction processes. For example, from 1991 to the present, YCM separation masters are prepared for every film. (2) And today, when a film is finished and output digitally onto a negative for release prints, another negative is assembled from the camera negative, the most pristine source, and that goes into cold storage.

Grover supervises a staff of about twenty-five people, six of whom are overseeing film laboratory and audio work full-time. Unlike other studio archives, Sony does not hand off preservation tasks to outside companies. Being a Film Person, Grover asks that for films a new negative be created, and fresh screening prints be prepared.

What impelled a big company like Sony to invest so much in preservation and restoration? Grover explained that the rise of home video taught most studios that their libraries had some value. In particular, executives were impressed by Ted Turner’s 1986 purchase of MGM for its library, which he could recycle endlessly on TBS. They realized that the libraries were genuine assets. Old movies enhanced the firm’s value (if it were to be sold, as many were in those days) and could be exploited through new media platforms, like cable.

The arrival of DVD made all the studios return to their libraries to make high-quality versions of their top titles. Now the high-definition format of Blu-ray will re-start restoration because of the leap in quality it offers.

Sony moved early, partly because it understood new media. When Sony bought Columbia Pictures in 1989, the Japanese executives envisioned a synergy between Sony’s hardware and a movie studio’s software. “One of the first things they asked,” Grover recalls, “was, ‘What’s the condition of the library?’” Soon afterward, Sony set up the first systematic collaboration between studio archivists and museum-based archivists. The Sony Pictures Film Preservation Committee included archivists from Eastman House, the Library of Congress, UCLA, MoMA, the Academy, and other institutions. In addition, Grover modeled Sony’s restoration policies on the exemplary work of legendary UCLA archivist Bob Gitt (whose work on sound restoration we’ve already saluted in another entry).

Digital restoration has been part of the Sony program. The 1997 restoration of Capra’s Matinee Idol (1927), from a Cinémathèque Française print, was the first live-action high-definition restoration from any studio.

Sony holds between 3600 and 5000 titles. It’s impossible to be more precise at this point because in hundreds of cases the rights situation is uncertain. But of the core library, about half to two-thirds of the films are restored. Crisp’s team is at work on about 200 titles at any moment! Many more are restored than warrant DVD release, but they may be available On Demand and via TCM, which has recently acquired cablecast rights to several older Columbia titles.

Restore, yes! But what, and how?

We’re grateful for preservation, but for cinephiles, restoration holds a special thrill. A “restored” Intolerance or Napoleon or von Sternberg movie gets us salivating. This year Cannes ran nine restorations on its program.

But what is a restoration?

We expect that a restoration will provide a film with a better-quality image or soundtrack than we’ve had so far. We often expect as well that a restoration will provide a more complete version of the title. Yet there are problems with both expectations.

First, who’s to say what the quality of the original is? Grover encountered this difficulty in restoring Funny Girl. It was released in the classic Technicolor dye-transfer process, usually considered the gold standard for color cinematography. He assembled five original Technicolor prints and all of them looked different. It turns out that Technicolor prints varied quite a bit. (3) The kicker was that Grover couldn’t make the new dye-transfer 35mm print of Funny Girl match any of these reference prints. That didn’t stop it looking fabulous when it premiered in LA.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

Moreover, it’s possible to “over-restore” a film. That is, by adding footage culled from many versions, the restorer may be creating an expanded version that nobody actually saw.

Original version? What does that mean? Paolo Cherchi Usai has reflected on this at length. (4) Is the original what the film was like on initial release? This is tricky nowadays for new titles, because as Grover pointed out, most films are “initially released” in several versions. Since Hollywood filmmaking began, different versions have been made for the domestic and the overseas markets, and often the overseas versions are longer. Sometimes a film opens locally or at a film festival and then is modified for release. Major films by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wong Kar-wai have played Cannes in versions longer than circulated later.

Now suppose that the film was modified by producers or censors for its initial release somewhere. If you can determine the filmmaker’s wishes, should you restore the film to what she or he wanted it to be? That flouts the historical principle of getting back to what people actually saw. Consider the shape-shifting Blade Runner. Only now, twenty-five years after its release, has the U. S. theatrical version appeared on video.

Or what do we do when a filmmaker, after the release, decides that the film needs to be changed? Late in life, Henry James felt the urge to rewrite many of his novels, and the revised versions reflect his mature sense of what he wanted his oeuvre to be. Why can’t a filmmaker decide to recast an older film? Such was the case with Apocalypse Now Redux and Ashes of Time Redux. Since the later version represents the artist’s latest viewpoint, should that be the authoritative version?

Grover encountered a variant of this problem when he invited one cinematographer to help restore a film. The cinematographer’s own aesthetic and approach to his work had evolved over the years, so he started to tweak things in a way that was taking the look of the film to a level much different than the original achievement. Grover had to steer him back to respecting the film’s original look.

On the brighter side: Grover brought in master cinematographer Jack Cardiff to advise on the restoration of A Matter of Life and Death. Cardiff said that one scene needed a “more lemony” cast. Grover tried, but each time Cardiff said it wasn’t right. Finally, Grover confessed that he just couldn’t get that lemony look. Cardiff nodded. “Neither could I.”

Grover offers this nugget of wisdom: It is almost impossible to get an older film to look the way it does when it was originally released. The color will never look as it did, nor will sound sound the way it did. Film stocks have changed, printing processes have changed, technology in general has changed. Every version is an approximation, though some approximations may be better than others. Take consolation in the fact that even when the movie was in circulation, it may have already existed in multiple versions.

What do consumers want?

All archivists explain that compromises enter into the preservation process down the line. One of the revelations of Grover Crisp’s visit was the awareness of just how many of these compromises come into play, and how some of them are tied to what DVD buyers expect.

Many films from Hollywood’s studio era are soft, low-contrast, and grainy. Project a 1930s nitrate copy today, and though it will be gorgeous, it’s likely to look surprisingly unsharp. Things apparently didn’t improve when safety stock came along in the late 1940s; projectionists complained that those prints were even softer and harder to focus than nitrate ones. As recently as the 1970s, films were not as crisp as we’d like to think. I’ve examined the first two parts of The Godfather on IB Tech 35mm originals, and though they look sharp on a flatbed viewer, in projection the grains swarm across the screen like beetles. (I should add that many of today’s films also look mushy and grainy in the release prints I see at my local.)

But I think that DVD cultivated a taste for hard-edged images, perhaps in the way that music CDs cultivated a taste for brittle, vacuum-packed sound. It’s not surprising, then, that video aficionados are often startled when a DVD release of a classic movie looks far from clean. This is not always attributable to a film’s not being cleaned up to the fullest extent the technology allows. Some films are inherently grainy, gritty, or soft-looking. With the advent of Blu-ray and HD imagery for the home, those films’ look is often mistaken for problems with the transfer, or signs that the distributor didn’t care enough to spend the money to thoroughly make it new. “New” in this case means contemporary.

So there are compromises, according to Grover, that the studios are having to deal with:

What do do about a film that is really grainy? Do you remove the grain, reduce the grain, leave the grain alone? Everyone seems to have a different answer, and it often puts the distributor in a difficult situation. These are questions that will be answered over time, as the consumer gets used to seeing images in HD that truly represent the way a film looks.

Another compromise involves sound. “Now you’re getting to an ethical area,” Grover remarks. In restoring early sound movies, Sony removes only clicks, pops, and scratchy noises (while still keeping the original, faults and all, as a reference). Sound problems are compounded in films from the early 1950s. Many releases at that time were shot in a widescreen process but retained monaural sound. Yet avid DVD buyers want multitrack versions to feed their home theatres. “If it’s not 5.1, we get complaints.” So Grover’s engineers “upmix” mono, as well as two-channel stereo, to 5.1—though they strive to keep the 5.1 minimal and retain as much authenticity as possible. Not on every film, of course: often the original mono track is included on the DVD.

On the positive side, Sony held the original tracks for Tommy (1975), originally released in Quintaphonic. (Old-timers will remember that audiophiles were urged to upgrade to this, and some LPs were released in that format.) Grover was pleased that he could replicate the theatrical version’s 5-channel mix on the DVD. (More details here.)

Now for a hobby horse of mine. The 1950s-1960s standards for multichannel sound were not those of today’s theatres. Today’s filmmakers funnel important dialogue through the front central speaker. But in multi-track CinemaScope and other widescreen formats, dialogue was spread to the left and right speakers as well, and these were behind the screen. That meant that a character standing on screen left was heard from that spot as well. (Remember, these screens might be seventy feet across.) Long ago Kristin and I saw an original 70mm release print of Exodus (shot in Super Panavision) in a big roadshow house in Paris. The ping-pong effect of the conversations between Ralph Richardson and Eva Marie Saint was fascinating.

Today, however, it might be distracting. In a home theatre, where discrete tracks present sound from offscreen left or right, it would seem downright weird. Although Grover didn’t comment on this, it’s clear that the big-screen classics from the magnetic-track era are remixed for DVD to suit current theatrical and home-video standards. This makes it very difficult for researchers to study the aesthetics of sound design from that period. Even if you visit an archive, that institution almost certainly isn’t able to project the film in a multi-channel version. (5) Is it too late to ask DVD producers to replicate, on a second soundtrack, the original channel layout? This would be a big favor to the academic study of the history of sound, and some home-theatre enthusiasts might develop a taste for the old-fashioned sonic field.

Last questions

Q: Do Grover and his colleagues take notice of online chat about DVD releases?

A: Yes, because it’s important to know what many participants in those conversations want from a film’s release, and they may also know things (from a hardcore fan’s pespective) about a film that is useful to know. Grover’s staff members can learn about missing scenes and other variant prints. But sometimes the Net writers are working from incomplete information and can get things wrong. A fan fervently announced that one word was intelligible in the “original” version of a film but not on the DVD. Yet the theatrical release version muffled the word. It turns out that the word was audible in a remixed TV version, which the fan had used as reference. Likewise, one critic who found the color on the Man for All Seasons Special Edition DVD too vibrant was evidently using a VHS version as the reference point. (For what it’s worth, the color in the Man for All Seasons theatrical release I saw was extremely vivid.) And Grover and his colleagues never intervene in the online debates.

Q: Why do DVDs seem different from projected prints—often much sharper?

A: An original film frame, in camera negative, has more resolution than can be captured in a print. Most prints are a generation or two past the material that a DVD transfer uses, so they gain a certain softness. Granted, however, in making high-definition video masters sometimes the tools to sharpen and de-grain the image are overused.

In addition, it’s generally a good idea to get your home video display calibrated. Most home displays are way too bright, sometimes brighter than a theatre screen. If you darkened the room and had the display dialed down, DVDs would look more film-like.

Q: When will we get the Boetticher westerns?

A: It’s the most frequent question Grover gets asked. Soon, soon: A boxed set of restored titles is on the way.

Q: And what about all the Capra titles?

A: Sony plans to restore each of them. Columbia struck many prints of them, and so there is some negative wear. Some negatives no longer exist. On one title, Say It with Sables (1928), Sony has neither negative nor prints.

There’s a too-good-to-be-true backstory here. Capra had a ranch in Pomona, which upon his death was bequeathed to Pomona State University. After some years, people found in a locked stable his private collection of prints struck in 1939. The cache included Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It with You, It Happened One Night, and the best-quality print of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Grover had yet seen. There were also photographs Capra had shot of premieres and vacations. Thanks to the good offices of Frank Capra, Jr., Sony acquired the prints and used them in its restorations.

As for American Madness, Grover called it a “training film” for later Capra productions. The theme of faith in the little man, manifested in a bank run that tests a humane banker’s alliances in the community, points ahead to It’s a Wonderful Life and other films. Sony holds a complete soundtrack and a nearly complete original negative. UCLA held a complete nitrate print donated by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department; evidently the film was screened in parks as public entertainment. That print wasn’t in good condition, but it allowed Grover’s team to fill out certain scenes. The nitrate print’s footage is noticeably lighter and grainier in a few places. American Madness wasn’t a digital restoration, but if it were done today Grover would probably use CGI to blend in the alien footage.

Talkies, with a vengeance

It was fine to see the film again; its brisk inventiveness held up. The gleaming and geometrical images of the opening, which acquaint us with the daily routine of opening the bank vault, might have come out of Metropolis. One helter-skelter montage sequence, complete with canted framings and chiaroscuro lighting, looks forward to Slavko Vorkapich’s delirious contributions to Mr. Smith and Meet John Doe.

The tactics of depth composition that we find in many 1930s movies reappear here, and the illumination has dashes of noir.

I especially like the dynamic pans that carry Walter Huston and Pat O’Brien in and out of the main office; I suspect that they’re cut together faster and faster as the climax gets near. And the huge set of the bank lobby, publicized at the time as the biggest set yet built on the Columbia lot, remains not only impressive but functional. It establishes a cogent geography to which Capra adheres strictly while filming it from a great variety of angles.

But this is not a treat just for the eyes. American Madness flaunts its mastery of emerging talkie technique. The rising action is accentuated by the steady increase in volume of the growing crowd in the bank lobby. The clerks’ scattershot morning chat in the vault is captured in microphone distances and auditory textures that suggest a hollow, sealed-off space. Hawks’ rapid-fire patter in Twentieth Century (1934) has an antecedent here, and at the same studio. The actors speak at a terrific clip, scarcely pausing between lines, and sometimes the dialogue overlaps. We even get competing lines, two or more speeches rattled off at once. (And did Hawks get the idea for His Girl Friday’s variants on telephone chatter from O’Brien working the receivers at the climax?)

In films like this, American movies talk American. Consequently, I’m inclined to regard as an in-joke the glimpse we get of a marquee that’s advertising another Columbia picture: Hollywood Speaks.

Thanks to Grover and Sony Pictures Entertainment for a wonderful series and an enlightening brace of talks. American Madness is available on the DVD set The Premiere Frank Capra Collection.

(1) Chris Horak has been head archivist at George Eastman House, the Munich Film Museum, Universal, and the Hollywood Museum; he’s now Director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Mike Pogorzelski is Director of the Film Archive for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Joe Lindner is Preservation Officer there. (Both are former Badgers.) Schawn Belston is Vice President of Asset Management and Film Preservation at Twentieth Century Fox. Paolo Cherchi Usai is Director of ScreenSound Australia, the national archive, and director of the recent film Passio. Kristin interviewed Mike and Schawn for this blog entry.

(2) YCM separation masters are made by copying a color film onto three black-and-white films. Thanks to filtering, these preserve color luminance at the different values of yellow, cyan, and magenta. Since these monochrome versions are not as susceptible to fading, they can be used for archival preservation. Combined, they can recreate the original color image.

(3) This confirms my impression when I’ve seen different Technicolor prints of the same title. You sometimes get this effect with a composite print, in which the color values change from reel to reel. Anecdotally, I’ve heard that Technicolor staff in the studio days would sort reels according to their dominant color (“That’s the yellow pile over there”).

(4) See Chapter 7 of Silent Cinema: An Introduction (London: British Film Institute, 2000). This book, incidentally, is a good introduction to the sheer fun of archive work. Others communicating the same enthusiasm are Roger Smither and Catherine A. Surowiec, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) and Dan Nissen et al., eds., Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002).

(5) This problem renders the activities of Britain’s National Media Museum in Bradford all the more important. There you can see classic films in a great many formats and sound arrays.

American Madness.

15 June: Thanks to Kent Jones for correcting a name slip.

19 June: Breaking News: Grover has just been promoted to Senior Vice President for asset management, film restoration, and digital mastering. Nice timing; wish we could say our blog put him over the top, butVariety explains that it was good old-fashioned talent. Congratulations to Grover!