Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Cavalcanti + Ealing = a little-known gem

Went the Day Well? A traitor gives information to a German infiltrator, who takes notes against a memorial to World War I dead

Kristin here—

As David and I sit here revising our Film History textbook for its third edition, we’re looking forward to the annual Il Cinema Ritrovato film festival in Bologna (June 28-July 5). We blogged from there last year and plan to do so again this year.

One of the festival’s themes in recent years has been World War II. Last year the program included Alberto Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well?, which he directed for Ealing Studios in 1942. Partly out of a sense of duty, since I cover Great Britain for the textbook, I went to the screening. It turned out to be a well-made, engaging, and surprisingly affecting film.

Alberto De-Almeida Cavalcanti

Alberto Cavalcanti is one of those names that people who take courses in film tend to be vaguely aware of, and that for only a handful of titles. He got his start as a set designer on Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1923). His first film as a director, the 1926 experimental city symphony Rien que les heures, is a minor classic of the era. Coal Face (1935) is one of the better known British documentaries of the 1930s. Cavalcanti worked for Ealing for several years in the 1940s, and a modern cinema buff is likely to know his two episodes of the collectively directed Dead of Night (1945), including “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy,” the most highly regarded of the batch. Devotees of Ealing or of classic British comedy will also be familiar with his Champagne Charlie (1944). His other best-known films are Nicholas Nickleby and They Made Me a Fugitive (both 1947).

In an era of globilization, Cavalcanti’s career looks positively modern. Born in Rio De Janeiro, he made his early films in Paris. He worked in British documentaries during the 1930s before moving to Ealing, and he remained in England throughout the 1940s. The rest of Cavalcanti’s filmmaking career saw him on the move, including projects in East Germany, Israel, and Brazil. He had a brief stint in TV in the early 1970s before he retired. He died in Paris in 1982. He tended to sign his films simply “Cavalcanti,” as is the case on Went the Day Well?

British Pluck

Based on Graham Greene’s short story, “The Lieutenant Died Last,” Went the Day Well? is a “what if?” tale. A group of Germans disguised as British soldiers deceive a small village’s citizens into letting them billet there and conduct practice exercises. In reality they are there to set up observation posts in preparation for an invasion.

When the film was being planned, there were many rumors in England that a German invasion was imminent and much speculation as to whether the country could resist such a thing successfully. The film has no doubts. In fact, its brief frame story is set in 1945, and the narrator, one of the inhabitants of the fictional village Bramley End, reveals that Germany has been defeated. The narrator shows us the grave of several German soldiers who died in the attempted infiltration.

From the start, then, the spectator is aware that the apparent British soldiers who arrive in Bramley End are disguised Germans and that they will be defeated. This seems like an odd tactic, letting us know so much, and yet it makes perfect sense. The point of the early part of the film is to introduce us to the villagers who will form the collective hero of the plot. Seeing them going about helping British soldiers settle into the local hall and various households would hardly be dramatic. As it is, knowing more than they do, we are in suspense as to whether and how they will discover the truth and react.

From the start, then, the spectator is aware that the apparent British soldiers who arrive in Bramley End are disguised Germans and that they will be defeated. This seems like an odd tactic, letting us know so much, and yet it makes perfect sense. The point of the early part of the film is to introduce us to the villagers who will form the collective hero of the plot. Seeing them going about helping British soldiers settle into the local hall and various households would hardly be dramatic. As it is, knowing more than they do, we are in suspense as to whether and how they will discover the truth and react.

At first they seem the conventional characters of a comedy or light drama—the sorts who would be the supporting roles in a Hitchcock film like The Lady Vanishes. They innocently cooperate in typical British fashion, giving directions and offering tea and spare bedrooms. The initial third or so of the film is pleasant in tone, despite our underlying awareness of the enemy being let into these people’s midst.

Yet the little scenes of ordinary life swiftly and subtly set up the traits in these people that will allow them to fight back later. The local shopkeeper and telephone operator may be a bit dotty and forgetful, but she also bridles when one of  the Germans manhandles a boy who had been snooping around the equipment in the soldiers’ truck. In the same scene, that boy is established as spunky and curious. Went the Day Well? manages to set up several major characters that we come to care about, as well as many recognizable supporting figures. There is no one protagonist. In fact, the film’s top-billed actor, Leslie Banks (familiar to modern audiences mainly from The Most Dangerous Game, the original Man Who Knew Too Much, and Henry V), is a traitor, secretly aiding the Germans. That’s Banks in the photo surmounting this entry.

the Germans manhandles a boy who had been snooping around the equipment in the soldiers’ truck. In the same scene, that boy is established as spunky and curious. Went the Day Well? manages to set up several major characters that we come to care about, as well as many recognizable supporting figures. There is no one protagonist. In fact, the film’s top-billed actor, Leslie Banks (familiar to modern audiences mainly from The Most Dangerous Game, the original Man Who Knew Too Much, and Henry V), is a traitor, secretly aiding the Germans. That’s Banks in the photo surmounting this entry.

Naturally once the villagers discover who their guests really are, they come through with English pluck and resourcefulness–the women as well as the men. The film doesn’t sugar-coat the conflict, though. A number of characters one would not conventionally expect to die do meet heroic ends, and the tone rapidly turns more serious roughly halfway through the action.

Went the Day Well? is a handsome film, too. British films of the 1930s sometimes look like low-budget Hollywood imitations, but by the 1940s the studios had more resources. Cavalcanti’s design sense serves him well, and the beautifully lit scenes and crisp editing look like something MGM could have been proud of. William Walton contributes a brief but suitably grand score.

Went the Day Well? is a handsome film, too. British films of the 1930s sometimes look like low-budget Hollywood imitations, but by the 1940s the studios had more resources. Cavalcanti’s design sense serves him well, and the beautifully lit scenes and crisp editing look like something MGM could have been proud of. William Walton contributes a brief but suitably grand score.

Sources

Unfortunately Cavalcanti’s films aren’t easily available on DVD in the U.S. The only current way to buy Went the Day Well? on region 1 DVD is as part of a set, the “British War Collection.” (The set was originally released as individual discs as well, and several copies of that edition of Went the Day Well? are offered on eBay.) Amazingly, the only other in-print films are Le Capitaine Fracasse (a re-discovered 1929 French film with a young Charles Boyer, co-directed by Cavalcanti), Nicholas Nickleby, and They Made Me a Fugitive.

Those with multi-region players can visit Amazon.uk, where one can find Went the Day Well?, the three films just listed, Dead of Night, and Champagne Charlie.

Went the Day Well? seems like the kind of film ripe for a Criterion edition, if we may drop a hint in their ear.

Added May 11:

David Cairns, director and scriptwriter, critic and blogger, and Cavalcanti fan has responded to this entry with one of his own, discussing other aspects of Went the Day Well? (Beware, his entry has more SPOILERS than mine.) As he rightly points out, the early portions of the film not only set up the bucolic village and its apparently conventional British country folk, but they provide an object lesson for citizens not to behave in such a naive and unquestioning fashion. Germans might be anywhere! I was mainly writing about the narrative conventions that would hold for a modern audience watching a decades-old classic. There’s no doubt, though, that for a contemporary audience there would have been that implication. The point is fairly explicitly made when one character finally finds a clue that makes her begin to suspect something is wrong, while another dismisses her ideas–with we all the while knowing that the woman who becomes suspicious is right.

I don’t think I buy another claim David makes about a subtext for the film: “the film becomes more subversive. According to Cavalcanti, a pacifist, his objective was to show that when war comes to even a place as charming as Bramley End, the people become monsters. Without the slightest change in underlying personality, peace-loving and jocular countryfolk pick up weapons and set about slaughtering their fellow humans.”

I don’t find the villagers in any way to be monsters, even in their most violent acts against the invaders. For one thing, it’s self-defense in wartime. The starkly violent scene of the Germans ambushing and mowing down a group of men from the Home Guard makes that clear from before the point when the villagers respond. I certainly can’t believe that the audiences of 1942 would have seen the villagers as descending into some primitively violent instincts. After all, this film came out only a little over a year after the end of the Blitz. In fact, the Germans had attempted to infiltrate England in preparation for the Battle of Britain, which in turn was to culminate in a land invasion. All infiltration attempts were thwarted, and poor intelligence was a major contributing factor to what became Germany’s first significant loss of the war. There would have been few people in Britain who could conceive of pacifism as a response to what they had recently lived through.

For another thing, the villagers don’t kill ruthlessly. All three women who kill someone pause afterward, clearly upset and even nauseated . The men are more blithe about it, but they’re seldom seen killing except in pitched battles, and just as often the village menfolk are the victims up until the rescuing soldiers arrive at the end. I’d argue that the characters’ underlying personalities are assumed to include the courage and determination that surface in time of need.

Thanks to David for his thought-provoking comments and for backing me up in urging that cinephiles should seek out this and other Cavalcanti films. He mentions They Made Me a Fugitive in particular.

DVD reviewer Slarek has reviewed Went the Day Well? on DVD Outsider. (Again, SPOILERS.) Among other interesting comments, he reveals that it was shot in Turville, Oxfordshire. I think Bramley End is probably supposed to lie in the south of England, where most of the German aircraft and the putative invasion would have entered the country. Still, the rolling landscapes and hedgerow-lined fields of Kent and Sussex are fairly similar to those of Oxfordshire. As Slarek proves with a photo, the village is not all that much changed today.

A glimpse into the Pixar kitchen

DB here:

On some of Bill Kinder‘s business cards, the I in PIXAR is represented by Buzz Lightyear, the blustery, not-too-swift astronaut of Toy Story. It’s a typical gesture of self-deprecation from the studio that showed that computer animation didn’t have to be just plastic surfaces and mechanical expressions. Pixar is cool, geeky, and warm all at the same time. Its films are both smart and soulful, made by movie fans for movie fans, and for everybody else. Like the best of the Hollywood tradition, Pixar movies have the common touch and still offer the most refined pleasures.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

A graduate of Brown, where he studied with our old friend Mary Ann Doane, Bill is like Pixar movies—intellectual, good-natured, energized, and adept at connecting with people. He started his career in news-gathering and TV editing before moving to work at Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope, in the days of Jack (1996) and the uncompleted Pinocchio project. He joined Pixar in 1996, while they were finishing Toy Story. When the success of A Bug’s Life enabled Pixar to move to a purpose-built facility in Emeryville, Bill went along.

Whittling vs. building

I’ve always been uncertain about what an editor does in the animation process. Since every shot is planned and executed in detail, what can be left for an editor to do? Bill started from that question. No, editing digital animation isn’t just a matter of cutting off the slates and splicing perfectly finished shots together.

As in live-action filming, the animation editor is working with dozens of alternate versions of every shot. The reason is that at Pixar, there are roughly five phases of production: storyboarding, layout, animation, lighting, and effects/ rendering. Each one generates footage that has to be cut together.

The static storyboards, for instance, present poses, expressions, and movements against a blank background. They are assembled in digital files that can be played back as if they were a movie. In order to plan the next phase, the resulting “footage” has to be edited, and choices are made at every cut. And each scene is storyboarded at least five different ways, with many variations of action and timing. A single film uses up to 80,000 boards!

At the next phase, layout, the scene’s overall action is planned. Layout artists develop the staging of each shot, testing different backgrounds and camera angles with the editors. Again, the alternatives have to be assembled and cut in various combinations.

Whittling versus building, Bill called it. The live-action editor gets a mass of footage that has to be triaged, but the animation editor is building and tuning the film from the start. Editing operates at each phase, from storyboarding to final rendering. This “almost overwhelming iteration,” as Bill called it, demands that the editorial department hold all the alternatives in its collective mind at once. Add to this the fact that Pixar can take up to five years to produce a film, maintaining several editorial teams to cover projects at different degrees of completion. When you realize that all this brainpower and bookkeeping are necessary for even the simplest shot, you appreciate the felicities of the finished product even more. These people make it all look easy.

Continuity and the viewer’s eye

Bill explained that digital animation occasionally requires something like live-action coverage. (1) Action sequences with fast cutting need to be spatially clear, and “chase scenes can be hard to board.” So sometimes the layout artists create master shots and closer shots from different angles that the editor will pick out and assemble, live-action fashion.

Like live-action editors, Pixar editors have to keep an eye on continuity of the objects in the frame. Because each shot is reworked across many phases, items of the set, lighting, color, atmosphere, effects and rendering have to be maintained, on many layers or levels of the program. (I gather it’s like the layers in PhotoShop.) Sometimes a layer, whether a prop, character, or set element, fails to “turn on” and so a discontinuity can crop up. A finished Pixar film typically has 1500 shots or more, so there’s a lot to keep track of.

In another carryover from live-action features, Pixar plots are conceived and executed in three discrete acts. It’s not only a storytelling strategy but a convenience in production. Rather than waiting until the entire film is done to examine the results of the different phases, the filmmakers can finish one act ahead of the others in order to troubleshoot the rest.

I’ve studied how filmmakers compose the image in order to shift our attention (2), so I was happy to hear that this process is of concern to the Pixar team. “Guiding the viewer’s eye,” Bill called it. He explained that in looking at storyboards and animated sequences, his colleagues sometimes use laser pointers to track the main areas of interest within shots and across cuts, especially when characters’ eyelines are involved. Nice to see that sometimes academic analysis mirrors the practical decisions of filmmakers.

The auteurs of Pixar

What makes Pixar films so fine? Bill supplied one answer: It’s a director-driven studio. As opposed to filmmaking-by-committee, with producers hiring a director to turn a property into a picture, the strategy is to let a director generate an original story and carry it through to fruition (aided by all-around geniuses like the late Joe Ranft). Within the Pixar look, John Lasseter’s Toy Story 2 and Cars are subtly different from Brad Bird’s The Incredibles and Ratatouille or Andrew Stanton’s Finding Nemo and upcoming Wall.E.

Bill covered many other fascinating topics, including the importance of sound (“the animated film’s nervous system”). But I’ll end with some pull-quotes from Bill’s talk.

*Francis Ford Coppola: “No film is ever as good as its dailies or as bad as its first assembly.”

*Gary Rydstrom: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

*Bill himself: “Editing is just writing, but using different tools.”

We’re grateful to Bill for his visit and look forward to seeing him again. Goes to prove what we’ve said before: Popular American filmmaking harbors many of the most intelligent, sensitive, and generous people you’ll ever find.

(1) In live-action production, coverage involves shooting a master shot of a scene that shows the entire action. Then parts of the action are repeated and filmed in closer views. This allows the editor several options for cutting the scene together.

(2) I talk about this in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style and throughout Figures Traced in Light. See also Film Art, pp. 140-153, and this blog here and here.

PS: Another glimpse into the kitchen: Bill Desowitz reports on Wall*E at Animation World. Now Pixar is trying to emulate the look of 70mm. And there’s footage from Hello, Dolly! in there? All the signs point to another nutty, dazzling achievement.

Lines of sight and light

DB here:

Two weeks ago the film critic and historian Paul Arthur died. (An obituary is here.) Apart from being a warm and robust man, Paul advanced our understanding of cinema in important ways. He was a committed teacher and an energetic writer. For years it seemed that almost every issue of Film Comment or Cineaste contained an essay by him. Although he had an encyclopedic knowledge of film, he wrote with particular brilliance about experimental work. His book, A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (2005), reflects a lifetime of sensitive study.

Paul was naturally on my mind as I watched the avant-garde films on display here at the Hong Kong Film Festival. I’ve mentioned some in an earlier entry, but I wanted to signal others that seemed to me especially fine.

A set by Ben Rivers had quiet poetic overtones. Very short (We the People lasts only one minute), they center on landscapes. I especially liked House (2007), a spectral suite of images derived from a miniature house Rivers contrived.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

Ken Jacobs is a legendary figure in the avant-garde. Prolific, outrageous, and wide-ranging in his interests, he has been at it for fifty years. His oeuvre includes the casually goofy Little Stabs at Happiness (1960), the epic Star Spangled to Death (1957-2004), and the classic Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969). There Jacobs dissected a 1905 Biograph film on the optical printer (see P. S. below), revealing not only isolated faces and gestures in its crowded shots but also abstract masses of light and dark, and even the grain of the film stock.

Across several years, Jacobs and his wife Flo have developed a mode of multiple-projection performance. Their Nervous System shows films at different speeds, halts them, drops down filters, even superimposes slightly different frames from prints of the same film, creating vivid 3-D effects. Such spectacles trigger comparisons to nineteenth-century impresarios of wonder: the conjuror who calls up ghosts, the sideshow entertainer whose calliope happen to be a movie machine. (1)

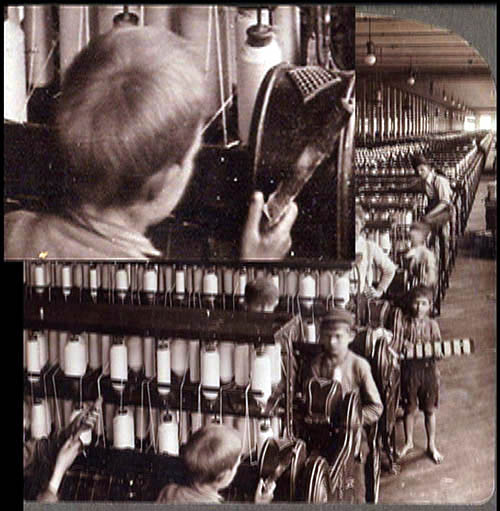

Capitalism: Child Labor (2006) might at first seem a rerun of Tom, Tom. A photograph shows men and boys at work in a thread factory. This dire image, with the workers’ flat expressions only adding to the sadness, might suffice in itself. But Jacobs takes the picture to pieces and shows us everything. He creates close-ups and long-shots, embedding them within one another to create games of scale. And then? Informed by Nervous System discoveries, Jacobs takes things a step further.

The picture originated as a stereoscope card. A stereoscope card consists of two side-by-side images, shot at angles corresponding to the difference between our eyes. Looking at the card through the viewer, the viewer has an illusion of 3-D. (Remarkably, my top illustration also features a factory scene.) For a detailed account of stereoscopy, see the Wikipedia entry.

Jacobs intercuts the two slightly different photos, often allotting only a single frame to each. With simple geometric shapes this procedure would yield “wiggle stereo,” as illustrated in the Wikipedia piece. But the density of the images evidently allows Jacobs to create a fluttering, nagging sense of volume. We seem to move just a bit around the figures and their workstations before popping back to our starting place, then launching again, endlessly. Somehow my brain thinks I’m spasmodically starting to circle through the factory.

This is why we’re right to call such films experimental. They often try to discover how our senses, our minds, and our emotions reveal themselves in their encounter with cinema. The goals are different, I grant you: Art exposes, science explains. But scientists should have a special eagerness to study avant-garde films. I can’t imagine anyone interested in filmic perception—and not just cognitivist film researchers—who wouldn’t find Capitalism: Child Labor a provocation to marvel at how our vision jumps to conclusions about depth. This movie makes us say Wow.

Song and Solitude, a 2006 film by Nathaniel Dorsky, was simply stunning. (2) In the Brakhage tradition, it’s woven out of lyrical shots of details seized and abstracted. Reflections, silhouettes, out-of-focus textures, veils and grids shedding unexpected ripples of light: everything seems radiant. Sometimes you recognize a familiar object, like a window screen pebbled with rain. Often, though, you have to ask: What am I seeing? And then Why don’t I ever notice this?

Dorsky’s Buddhist-influenced aesthetic, revealed in his book Devotional Cinema, drew this commentary from Paul Arthur:

Old School doesn’t describe it. Dorsky has achieved such a subtle mastery over the most basic means of cinematic expression–composition, duration, juxtaposition–that he can squeeze a wealth of emotional vibrations out of the silent, seemingly banal interplay of foreground and background objects. A formalist with a brimming, elegiac soul, Dorsky will gently rock your attitude toward cinematic landscape. His world is a sublime mystery measured by patience and unmatched visual insight.

I didn’t know Paul well. I met him around 1974, when we had a good conversation about landscape in Anthony Mann. We ran into each other occasionally over the years and corresponded a little.

His generosity to Kristin and me came through on several occasions. In a roundtable discussion published in October no. 100, he called attention to the fact that Film Art tried to remind students and teachers of the importance of avant-garde film. (3) In reply to an essay of mine in Film Quarterly, he sent overabundant praise but added several pointed questions that forced me to tighten up my argument. Most vividly, when I was criticized (some would say personally attacked) in the pages of Film Studies’ most prestigious academic journal, he was moved to write me with encouragement. Of my critic he wrote: “To hell with him if he can’t take a joke.”

Like a great many others, I will remember Paul with affection and admiration.

Song and Solitude.

(1) An engrossing interview with Jacobs can be found here.

(2) By the sort of coincidence I like, Song and Solitude also played the Wisconsin Film Festival, which I had to miss this year. Trusty Joe Beres of the Walker Art Center, still a Badger at heart, provides coverage.

(3) The discussion is here, but beyond the first page the material is proprietary.

P. S. 21 May 2009 Keith Sanborn wrote me to point out that, in a reply to Ed Halter (who discusses Anaglyph Tom (Tom with Puffy Cheeks) in Artforum), Ken Jacobs corrects the frequent claim that the 1969-71 Tom, Tom was made on an optical printer. No, says Jacobs; he rephotographed the movie from the screen. Here is the inimitable explanation Jacobs supplied to Halter.

The movie so pushes forward the character of film projection. Images explode out of darkness. Nor was I using a specialized analytic projector that with a steady flicker minimizes exchange of frames. I used what had been a common RCA home sound-projector, from the 1940’s, possibly the late 1930’s, but one with a hand-controllable clutch that allowed for slowing and even stopping the film. Freezing as it’s called but usually more like burning. A heat-shield would fall in place to protect the film from burning but would then darken the image, and so I removed it and took my chances with burning. The energy that is light was a featured and constant presence in the work. Darkness is death and the old reclaimed images constantly struggle against death to proclaim themselves. Release of energy, via intermittent projection or in the return of rambunctious ghost-actors, was much of what the work was about.

Thanks to Keith for calling my attention to this.

Truly madly cinematically

DB here, still in Hong Kong:

You are a film director. How do you convey to an audience that a character mysteriously sees hidden personalities in other characters?

Filmmakers are problem-solvers, at least sometimes, and I’ve argued elsewhere that we can often explain their creative choices as efforts to pose and solve problems. I ran across an intriguing example during my stay here in Hong Kong. I interviewed Tina Baz, the editor for Johnnie To’s film Mad Detective (2007), which I blogged about from Vancouver in October.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Mad Detective was Tina’s first film for Johnnie To, as well as her first experience with the Hong Kong crime genre. She was accustomed, she says, to the more psychologically-driven narratives of French cinema, and she had to work in a new way during the seven weeks it took to edit the film. This is an unusually long editing time for Hong Kong filmmaking, and it reflects the complicated tasks this film set her.

If you haven’t seen Mad Detective, you will probably want to stop reading. The scenes I’m discussing come fairly early in the film, but they do contain some surprises you might not want to know about in advance.

Headquarters

The rough cut of the film, adhering closely to Wai Ka-fai’s script, displayed a complicated flashback structure. The plot began fairly far into the action and then jumped back to establish the exposition. Central to that exposition is the film’s premise: Detective Bun, played by Lau Ching-wan, solves cases by extraordinary telepathic/ intuitive/ visionary insights. But the original cut blurred that concept, mixing it with an early revelation of the identity of the villain, a corrupt cop named Ko Chi-wai, and background on Bun’s young partner Ho. How to cut through the clutter?

The first step to a solution was to straighten out the chronology and to focus tightly on Bun from the start. The audience needed to understand the film’s eccentric psychological premise—specifically, that Bun’s gift allows him to detect multiple personalities buried within another person.

In talking with me, Tina went over three scenes that establish Bun’s peculiar abilities. (1) The sequences furnish striking examples of how filmmakers find precise technical solutions to storytelling problems. This trio of scenes also follow Hollywood’s Rule of Three. According to this, a key piece of information should be presented three times, preferably in different ways. (2) (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for slow Joe in the back row.) Tina smiled. “This is not something that French directors would say.” The Rule of Three can be seen as another aid to solving the broad problem of clarity—making sure that the audience understands the story.

Discussing all three scenes adequately would take a lot of space and require dozens of stills, so I’ll concentrate on the first two. These should suffice to show how the filmmakers solved a tricky narrational problem.

The first scene takes place in police headquarters and it’s the simplest. It starts with Bun absorbing details of Ho’s investigation. We hear, offscreen, a whining woman complaining that a maniac can’t solve a case. We think at first that it’s the voice of another cop, but after a second complaint from offscreen, Bun looks up. Cut to the whining woman, who stands among the cops.

Bun rises and walks to a pudgy cop who grins ingratiatingly. Now cut from the cop to the whining woman, in a similar composition against the same background.

An over-the-shoulder shot presents Bun staring as we hear the fat cop asking, “Do you recognize me?”

After the fat cop flatters him, Bun head-butts him. Bending over the fallen cop, Bun says, “Shut up. I see and hear you, bitch!” Cut from the bloody-nosed cop to Bun to the bloody-nosed woman.

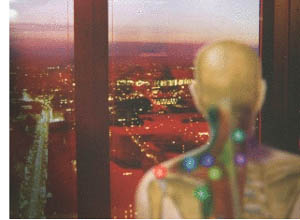

After Ho dismisses the team, Bun slowly approaches and confides: “I can see the inner personalities of a person” (below). This line of dialogue crystallizes what we’ve seen–the bitchy woman inside the ingratiating man–and prepares for the next few scenes.

On the street

The second vision scene is more complicated, and Tina had several discussions with To and Wai about whether to include it. The new problem, based on the key line above, is to establish that Bun can see not one but several hidden personalities in Ko, the crooked cop. How can this premise be shown?

The major scene coming up shows the two partners confronting Ko at a restaurant. There Bun will envision some of Ko’s inner people manifesting themselves. But there’s also dramatic conflict to be conveyed in the scene, which culminates in a beating in the men’s room. Again, too much information! Tina, To, and their colleagues decided to include an intermediate scene, one that had little dramatic consequence but got audiences more comfortable with the premise.

Ho and Bun trail the suspect along the street, first in a car and then on foot. The results have the kind of precision I’ve pointed to in another Milkyway film, PTU.

In the car, Tina’s cutting establishes the differences between the two cops’ points of view. A two-shot of Ho and Bun yields to a straightforward POV shot of Ko striding along the sidewalk.

But a cut to Bun watching is followed by a shot of seven people in Ko’s place. In a nice instant of uncertainty, a few heads emerge from behind a parked van and are only partially visible. At first glance we might take them for passersby walking ahead of Ko.

Before we can fully identify this band of spirits, and as the car draws abreast, a cut to Ho watching leads to a shot of Ko, whistling.

Another cut to Bun, and now we see, as he apparently does, a full view of the platoon of Ko-personalities striding along whistling.

This mildly wacko variant is consistent with the narration’s mixed attitude toward Bun’s visions: are they supernatural insights or hallucinations?

Bun leaps from the car and pursues Ko’s band of personalities, and a new variation shows him and them in the same frame. But this is re-framed by Ho’s POV, which reasserts that to anyone but Bun, Ko is all by himself.

Abruptly, the visions halt and turn, staring at Bun. By now we are trained to understand what’s happening without a corresponding objective shot of Ko. Ko, we infer, has turned around to check on who’s following him.

Likewise, we can grasp the image of Bun passing through the group of figures as simply Bun walking past Ko.

At this point, we have no need to see the objective action. To and Tina have stressed the absence of an objective view by showing Ho, in the background, looking in another direction and missing this byplay (above). After Bun has passed, the troupe of avatars walks in their new direction, and then we get the objective shot of them “as” Ko.

This effect is anchored when Ho turns and notices Ko going into the restaurant.

As a meticulous touch, Ko’s departure from the frame reveals Bun still walking away in the distance. The geography is simple and impeccable.

The idea of seeing “inner personalities” has been made concrete while undergoing a lot of variation. Sometimes shots of the spirits are sandwiched between shots of Bun looking; sometimes not. Sometimes we have Ho to verify what’s really happening, but sometimes not. And sometimes Bun can be in the same frame as the avatars. Otherwise, Tina points out, the scenes would become boring.

Once the street scene has laid out how Bun sees Ko Chi-wai, the next scene, unfolding in the restaurant and a men’s toilet, can play with the premise still more. Tina explains that the creative team constantly asked, “How far can we go with Bun’s point of view, his vision?” Quite far, it turns out. The premise gets varied further across the whole movie, in imaginative ways. Which is to say that a solution to a problem can pose new problems, which the filmmakers go on to grapple with.

In our discussion, Tina noted that the street scene goes beyond simply giving us information. There’s a disquieting emotional effect when the spirits turn and confront Bun, their expressions ominously blank. Finding a solution to a creative problem often yields an unexpected payoff like this.

Bonus features

As I indicated, I can’t pursue the felicities of the restaurant scene here. Instead, here are some quick final thoughts.

*Mad Detective shows once more the power of basic techniques of performance (e.g., the act of looking), framing, and editing. To and Wai have no need for fancy CGI effects to evoke the “inner personalities” of Ko or the other cop. Our minds make the necessary connections. Lev Kuleshov would have admired the engineering economy of this sequence.

*In passing Tina and I talked about actors’ eyes, a special interest of mine. (3) Tina had noticed that actors try not to blink. She agreed that blinks pose problems for editors: “Blinking is very hard on cutting.” She remarked that Elia Suleiman would strain to keep from blinking until tears flowed from his eyes.

*Mad Detective was signed by both Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai, but their joint projects are usually filmed by To, with Wai supplying the script and consulting as production proceeds. Tina confirms To’s habit of shooting with the whole scene’s layout in his head, using very few takes per shot and not a lot of coverage. The film is “very pre-cut,” she says. You can see this, I think, in the way To relies on matches on action and ends one shot with something that prepares you for the next one.

*To follows Hong Kong tradition of adding all the sound in postproduction. This makes for economy and efficiency in shooting, but it also gives HK films the fluency of silent cinema. The filmmaker gains a freedom of camera placement and is encouraged to think about how to tell the story visually. Tina and Shan Ding, To’s all-around assistant, pointed out that sync sound might make the director depend more on dialogue and static conversation scenes. Still, I think that sometimes they wish for a scene shot with direct sound.

*As with many Milkyway films, several scenes were filmed at the company headquarters. An earlier blog here discussed the ambitious rooftop set for Exiled. For Mad Detective, the fistfight in the restaurant toilet was filmed in the main men’s room of the Milkyway building, with a fake urinal added. Shan Ding provides documentation in the snapshot below, using a double for Lam Suet.

To come: Another Milkyway interview, this one with ace sound designer Martin Chappell. And a final batch of impressions from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, which ends on Sunday.

(1) If you know Mad Detective, you’re aware that Bun’s ability to discern hidden personalities is displayed in an earlier scene. But given the way in which that story action is presented, we can’t say that that his powers are established there. This scene is one of many clever narrational stratagems in a film that benefits from being rewatched.

(2) See Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 31.

(3) Laugh if you must, but I wrote an essay about this. “Who Blinked First?” is available in Poetics of Cinema.