Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Bwana Beowulf

KT: I do not understand Beowulf. I don’t understand why the director who made one of the great modern Hollywood films, Back to the Future, and several very good ones, including Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and Cast Away, now has this fixation with creating nearly photo-realistic 3D digital images.

DB: I think that on the whole Zemeckis’ films have become weaker since Bob Gale stopped working with him. I like the sentiment of I Wanna Hold Your Hand and the crass misanthropy of Used Cars, and I think the Back to the Future trilogy mixes both in clever ways. But now almost every Zemeckis film seems to be less about telling a story than solving a technical problem. How to best merge cartoons and humans (Roger Rabbit)? How to push the edge of spfx (Death Becomes Her, Forrest Gump, Contact)? How to make half a movie showing only one character (Cast Away)? There’s a stunting aspect to this line of work, though I grant that it can lead to technical breakthroughs, as in Gump.

KT: I also don’t understand why most of the supposedly state-of-the-art effects technology looks distinctly cruder than the CGI in The Lord of the Rings, the first part of which came out six years ago. I don’t understand why studios that are trying to push 3D to a broad audience make a film with silly action aimed at teenage boys. That’s an OK strategy when you’ve got a $30 million horror film, but a budget of $150 million demands a lot broader appeal.

DB: And the evidence so far indicates Beowulf doesn’t have that appeal. The obvious comparison is 300, from earlier this year. According to Box Office Mojo it cost about $65 million to make, but it reaped $70 million domestically in its first weekend and wound up with $450 million theatrically worldwide. Beowulf grossed $27.5 million in its first US weekend and currently sits at about $146 million worldwide. I’d think that this has to be a disappointment. Recall too that the Imax screenings have higher ticket prices, so there are fewer eyeballs taking in Angelina Jolie’s pumps, braid, and upper respiratory area.

In addition, sources suggest that a 3-D version of Beowulf will not be available on DVD, so the sell-through takings—the real source of studio profit—may be significantly smaller than average.

KT: It seems to me that the people who are pushing 3-D so hard and hoping for it to become standard in filmmaking are forcing it on the public too soon. It’s still fiendishly difficult and expensive to shoot live action material in digital 3-D, so most projects are animated. One approach, taken in Beowulf, is to motion-capture real people and animate the characters to make them appear as much like the real people as possible. The problem is that they still have a weird look about them, like moving dolls. People have complained about the dead-eyed gaze of the characters in The Polar Express, and though there’s apparently been an improvement between the two films, the eyes don’t always look as though they’re focusing on anything. It can be done, though; the extended-edition Lord of the Rings DVD supplements about Gollum show how much effort went into making his eyes have a realistic sheen and flicker.

I was also struck by how clunky some of the animation looked. Beowulf is supposedly state of the art, and it certainly had the budget of a major CGI film. Yet some of the rendering and motion-capture was distractingly crude. I noticed that particularly on the horses. Their coats looked pre-Monsters, Inc., and their movements at times reminded me of kids rocking plastic toys back and forth. I suspect this effect had something to do with a lack of believable musculature. If you look at the way the cave troll was done in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (again, demonstrated in the DVD supplements), there was a specific program to simulate the way muscles move on skeletons, even the skeletons of imaginary creatures. Now, six years later, we see these things that look like hobby-horses—and that all run alike.

The backgrounds were often strange as well, simple and flat-looking, like painted backdrops. There were some exceptions, with the seascapes and rocky crags pretty realistically done. But just plain hillsides and groups of tents and so on looked almost sketchy in comparison with the moving figures, and I noticed that at times some fog would be put in, presumably to cover that problem up. There certainly was some very good animation as well, most notably the dragon, but there was no consistency of visual style.

DB: I’d go farther and say that 3-D hasn’t improved significantly since the 1950s. It ought to work: just replicate the eyes’ binocular disparity by setting two cameras at the proper interval or, now, by manipulating perspective with software. Yet in films 3-D has always looked weirdly wrong. It creates a cardboardy effect, capturing surfaces but not volumes. Real objects in depth have bulk, but in these movies, objects are just thin planes, slices of space set at different distances from us. If our ancestors had seen the world the way it looks in these movies, they probably wouldn’t have left many descendants.

It would take a perceptual psychologist to explain why 3-D looks fake. Whatever the cause, I’d speculate that good old 2-D cinema is better at suggesting volumes exactly because the cues to depth are less specific and so we can fill in the somewhat ambiguous array.

By the way, in watching a 3-D movie I seem to go through stages. First, there’s some adjustment to this very weird stimulus: I can’t easily focus on the whole image and movement seems excessively fuzzy. Then adaptation settles in and I can see the 2 ¼-D image pretty well. But adaptation carries me further and by the end of the movie I seem to see the image as less dimensional and more simply 2-D; the effects aren’t as striking. But maybe this is just me.

Back to the Future, or at least 1954

DB: I’d like to think about it from a historical perspective for a while. The industry seems to be repeating a cycle of efforts that took place in 1952-1954. The American box office plunged after 1947 as people strayed to other entertainments, including TV, and so the industry tried to woo them back with some new technology. Today, as viewers migrate to videogames, the Internet, and movies on portable devices, how can theatres woo their customers? Answer: Offer spectacle they can’t get at home.

Beowulf brings together at least three factors that eerily remind me of the early 1950s.

(1) Obviously, 3-D. The first successful 3-D feature era was Bwana Devil, released in November of 1952. It was an uninspired B movie, but it launched the brief 3-D craze. Columbia, Warners, and other studios made major pictures in the format, most notably House of Wax (1953). But costs of shooting and screening 3-D were high, with many technical glitches, and apart from novelty value, the process didn’t guarantee a big audience. The fad ended in spring of 1954, when all studios stopped making films in the format.

The process has been sporadically revived, notably in the 1980s (Comin’ at Ya, Jaws 3-D) and once more it fizzled. So, ignoring the lessons of history and chanting the mantra that Digital Changes Everything, we try it again.

(2) Big, big screens. In September of 1952, Cinerama burst on the scene with its huge tripartite screen and multitrack sound. It attracted plenty of viewers, but it could be used only in purpose-built venues. Like 3-D, its technology could never replace ordinary 35mm as the industry standard. The contemporary parallel is Imax, which though very impressive will not replace orthodox multiplex screens—too expensive to install and maintain, pricy tickets. Like 3-D, it’s a novelty. (1)

(3) The sword-and-sandal costume epic. It’s a long-running genre, but it got significantly revived in the late 1940s. It was a logical input for the new technologies of widescreen—not Cinerama but more practical offshoots that gained more general usage.

From the standard-format Samson and Delilah (1949), David and Bathsheba (1951), and Quo Vadis (1951) it was a short step to The Robe (1953) and The Egyptian (1954) in CinemaScope, The Ten Commandments (1956) in VistaVision, The Vikings (1958) in Technirama, Hercules (1959) in Dyaliscope, Solomon and Sheba (1959) and Spartacus (1960) in Super Technirama 70, and Ben-Hur (1959) in anamorphic 70mm Panavision. It is, incidentally, a pretty dire genre; the peplum might be the only genre that has given us no great films since Cabiria (1914) and Intolerance (1916).

In parallel fashion, the revival of the beefcake warrior film with Gladiator (2000) coincided with innovations in CGI and thus furnished new forms of spectacle for Troy (2004), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), and 300 (2007). This trend paved the way for Beowulf. When screens get bigger, Hollywood hankers for crowds, oiled biceps, big swords, and nubile ladies in filmy clothes. Not to mention soundtracks with pounding drums, wailing sopranos, and choirs chanting dead or made-up languages. And the conviction that Greeks, Romans, and those other ancient folks spoke with British accents. The innovation of Beowulf is to turn a Nordic hero into a Cockney pub brawler.

In other words, it’s 1954 again. So if we ask, Will it all last? I’m inclined to answer, Did 1954?

KT: Yes, the studios see the new technology as one more way to lure people away from their computers and game consoles and into the theaters. Maybe that will work to some extent. There’s no doubt that a lot of the people who have seen Beowulf have praised it as a fun experience and as having effectively immersive 3-D effects. I’m surprised at how many positive comments there are on Rotten Tomatoes, where the average score from both amateur and professional reviewers is 6.5 out of 10. That’s not exactly dazzling, but it’s a lot higher than I would give it.

Even so, the film hasn’t lured all that many people away from their other activities. You’ve mentioned that Beowulf hasn’t done all that well at the box-office. It did much better in theaters that showed it in 3-D. If it hadn’t been for the 3-D gimmickry, it would probably have been dead in the water from the start. And if 3-D effects remain on the level of gimmickry, they will soon wear out their welcome. Presumably the people who have been going to Beowulf are to a considerable extent those who are already interested in 3-D, and I can’t believe there are huge numbers of people really passionate about the idea of someday being able to watch lots of films in 3-D. If more films like Beowulf come out—ludicrous, bombastic action with distracting animation problems—they’re not likely to make the prospect any more attractive.

Eventually somebody—James Cameron or Peter Jackson, perhaps—will make the first great 3D film, and then maybe the passion will spread.

3-D in 2-D

DB: I’m doubtful that there will ever be a great 3-D film, and especially from those directors. But one last historical note.

I think that ordinary mainstream cinema has been setting us up for the flashiest 3-D flourishes for some time. One of the goals of the Speilberg-Lucas spearhead was to amp up physical action, to make it more kinetic, and this often showed up as in-your-face depth. Spielberg used a lot of deep-focus effects to create a punchy, almost comic-book look, and who can forget the opening shot of Star Wars, with that spacecraft arousing gasps by simply going on into depth forever? Seeing the movie in 70mm on release, I was struck by how the last sequence of Luke’s attack mission was maniacally concerned with driving our eye along the fast track of central perspective. Did it foreshadow the tunnel vision of videogame action?

In any case, I think that aggressive thrusting in and out of the frame was integral to the style of the new blockbuster. Since then, our eyes have been assaulted by plenty of would-be 3-D effects in 2-D. In Rennie Harlan’s Driven (2001), the crashing race cars spray us with fragments.

Jackson is definitely in the Spielberg line, favoring steep depth and big foreground elements. In King Kong, the primeval creatures lunge out at us, heave violently across the frame, and fling their victims into our laps.

Such shock-and-awe shots recall American comic-book graphics. These affinities are at the center of 300, as we’d expect. For example, a cracking whip curls out at us in slow motion, like a two-panel series.

Beowulf draws on this thrusting imagery, but inevitably it doesn’t seem fresh because so many 2-D films have already used it. Maybe the most original device is having the camera pull swiftly back and back and back, letting new layers of foreground pop in and shrink away. This is viscerally arousing in 3-D, but aren’t there precedents for it—in the Rings, in animated films, or some such?

Zemeckis tries to transpose into 3-D the style of what I’ve called, in The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity. This style favors rapid cutting, many close views, extreme lens lengths, and lots of camera movement. I found Zemeckis’ restless camerawork even more distracting than in 2-D. So I’m wondering if current stylistic conventions can simply be transposed to 3-D, or do directors have to be more imaginative and make fresher choices?

KT: That pull-back effect may be viscerally arousing, but in Beowulf it was usually pretty gratuitous and, for me at least, it called attention to itself in a way that was often risible. I don’t think there’s anything in Rings as crude as the shots in Beowulf that you’re talking about. In the opening scene of the latter, in the mead-hall, the camera zips into the upper part of the room, with rafters, chains, torches, and even rats whizzing in from the sides of the frame. None of that contributes to the narrative.

The flashiest backward camera movement, or simulated camera movement, I can think of in Rings is the one in the Two Towers scene where Saruman exhorts his army of ten thousand Uruk-hai to battle. The final shot is a rapid track backward through the ranks of soldiers holding flag poles. The point is to stress the enormous numbers of soldiers. There’s no gratuitous thrusting-in of set elements from the sides, just the cumulative effect of so many similar figures. The simulated camera also at one point “bumps” one of the flagpoles, causing it to wobble, but I take it that that’s an attempt to add a certain odd realism to the “camera” movement, not a knowing nudge to the audience. In Rings, the virtual camera usually follows action rather than moving independently through space. It tends to go forward or obliquely rather than backward.

As to transferring classical Hollywood style to 3-D or finding a whole new set of conventions to fit 3-D, Beowulf offers an object lesson. It uses a combination of the two. At times we have conventional conversations using shot/reverse shot, and at other times we have the swoopy-glidey style you described, with the camera zipping around the space and trying to see it from every angle within a few seconds.

The odd thing is, neither one works. The very close shot/reverse shot views of the digital characters make them look unnatural and emphasizes the not infrequent failure of their eyes to connect with each other. The swoop-glidey camera movements are silly and don’t stick to the narrative.

I’m not optimistic enough to think that directors can come up with a whole set of “fresher stylistic choices” to make 3-D work. Maybe Sergei Eisenstein, with his meticulous attention to every aspect of such topics, could have thought the issue through, but his solution would probably not be viable for the Hollywood studios. My own thought is that directors working in 3-D should probably stick to classical Hollywood style and avoid flashy stylistic effects. So far, the more blatantly 3-D something looks on the screen, the less it makes 3-D seem like something we want to watch on a regular basis. Think of the best films of this year: Zodiac, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Ratatouille, Across the Universe, and so on. Would any of them be better in 3-D? Probably not.

Plus, I don’t like watching movies through something. Movies should just be the screen and you. The 3-D glasses are definitely better now than in the earliest days of the cardboard, red/green versions. Still, the Imax glasses we used in watching Beowulf were heavy enough to leave a groove on my nose. Make the mistake of touching the lenses, and you’ve got a blur on one half of your vision of the film. In short, I think that 3-D still has to prove itself, and Beowulf didn’t add any evidence.

(1) PS 9 December: DB: I originally added in regard to Imax: “It’s actually waning in popularity, except in newly emerging markets like China.” This disparaging comment was misleading. Yesterday I learned from Screen International that Imax recently signed a deal with AMC to install 100 systems in 33 US cities. Oops! Today Paul Alvarado Dykstra of Austin’s Villa Muse Studios kindly wrote to point out the Hollywood Reporter‘s coverage, which gives background on the costs of installing and maintaining an Imax facility.

I was, obscurely, thinking of the traditional Imax programming of travelogues and documentaries. I failed to register that these have been largely displaced by screenings of blockbuster features, catching fire in 2003 with The Matrix Reloaded and proving successful with The Polar Express and other titles. Imax is now largely an alternative venue for megapictures, and its seesawing financial performance may have been steadied by moving into the features market.

PS 26 December: Travel has delayed our timely linking, but we couldn’t neglect Mike Barrier’s in-depth critique of Beowulf here.

PPS 5 January 2008: Harvey Deneroff has a comprehensive and judicious discussion of the 3D situation here.

Bob Shaye is the most reckless man in Hollywood. True or false?

|

=

? |

|

Kristin here–

As a writer and even more as a reader, I am frequently baffled when an author with a fascinating, innately dramatic story to tell feels it necessary to ratchet up its appeal with hype. I’m an amateur Egyptologist and sometimes watch the documentaries made by the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, and the other educational TV outlets. Now, a great many people are fascinated by ancient Egypt in a way that they aren’t by virtually any other period of history. So many events and aspects of that society are at least intriguing, at most amazing. The building of the pyramids, the process of mummification, the distinctive artworks–all of these could sustain straightforward presentation.

Instead, the filmmakers responsible for these documentaries feel it necessary to beef up their ancient subject matter. The factual scenes are interspersed with shots of actors dressed in pharaonic costumes driving chariots across the desert, accompanied by overblown music. Archaeologists hover outside supposedly sealed tombs or chambers, speculating breathlessly as to what might be inside. Artificial mysteries are overly prolonged, when all along the filmmakers know the answers. Since the channels producing these documentaries are often subsidizing the archaeologists’ work, there is pressure for these scholars to make more glorious claims for their findings than the facts warrant.

Similarly, film history contains innumerable stories that are both educational and entertaining, if told in a straightforward, factual way. Any major film’s making yields many facts and anecdotes that are in themselves interesting. Yet here, too, many authors—especially journalistic ones—seem to feel the need to inject an artificial drama into their tale. This can be harmless, but if an author tries too hard, the facts get obscured or distorted.

In the case of big box-office successes, journalists tend to find one over-arching claim that can seem to explain a film while giving it an extra dose of drama. There was one such concerning The Lord of the Rings that I encountered over and over when I was researching The Frodo Franchise. Despite all the twists and turns that the progress of the film took—the unlikely move from Miramax to New Line, the last-minute casting of Viggo Mortensen, the struggles to reach remote filming locations, the third part’s winning eleven Oscars, and many, many more—somehow there wasn’t enough drama. In this case, the big claim was that Rings was an immense gamble on the part of New Line’s founder and co-president, Bob Shaye. Some have believed, both before and after the trilogy’s release, that its failure would have meant the end of New Line. The independent firm would have been absorbed into parent company Time Warner, and Shaye would have been stripped of power.

My book was written after all three parts of Rings had gone into the box-office record books. New Line had grown considerably and was in no danger. During my research I questioned people involved in the film’s production and people in the industry who would have reason to know whether New Line really stood in such a precarious position in 2001. Opinions were divided, but few thought that New Line would have disappeared had the trilogy flopped. A gamble, yes, but ones where the stakes were lower and the odds more in New Line’s favor than most accounts would suggest.

Boffo! by Bart

I can see why journalists, even in trade papers like Variety and Hollywood Reporter, would find it convenient to fall back on this gamble motif when writing copy on a short deadline. Now, however, the familiar claim has reappeared in Peter Bart’s book, Boffo! How I Learned to Love the Blockbuster and Fear the Bomb (Miramax Books, 2006). Bart deals with extremely successful films, plays, and TV shows. The Lord of the Rings occupies one chapter.

When the first anniversary of this blog rolled around, David wrote about some of our goals as film scholars and bloggers. One of them was this:

We’ve tried to deflate some clichés of mainstream film journalism. Writers of feature articles are pressed to hit deadlines and fill column inches, so they sometimes reiterate ideas that don’t rest on much evidence. Again and again we hear that sequels are crowding out quality films, action movies are terrible, people are no longer going to the movies, the industry is falling on hard times, audiences want escape, New Media are killing traditional media, indie films are worthwhile because they’re edgy, some day all movies will be available on the Internet, and so on. Too many writers fall back on received wisdom. If the coverage of film in the popular press is ever to be as solid as, say, science journalism or even the best arts journalism, writers have to be pushed to think more originally and skeptically.

The same goes, only more so, for books written in the same spirit. Journalistic writing is at least somewhat ephemeral. Books, though, stay on the shelf, and they automatically command a certain respect.

As I said, the story of Rings, told straightforwardly, is immensely dramatic. What better story could a film historian possibly have to tell? All through the researching and writing processes, I tried simply to discover, convey, and interpret that story without adding hype.

Bart adds the hype. His chapter on Rings not only revives the old gamble angle but goes further, asking, “What was the bravest gamble in the history of filmmaking?” Arguably, he answers, the trilogy.

Why? First, it was risky to make all three films at once. Granted, though as Bart acknowledges, there were enormous cost benefits from doing so. Second, the initial budget of $130 million, according to Bart, ballooned to $330 million. Now the problems start. $130 million was the budget when Rings was still a two-part project at Miramax. Taking over the film, New Line provisionally kept the existing budget until a three-part script could be written and the costs estimated on a firm basis. The estimate then grew to $270 million, which we should count as the budget the studio was really working from. The success of Fellowship of the Ring led New Line to agree to requests for more money in making the second and third parts. Costs did not run wildly over expectations.

What else was so risky? According to Bart, New Line earmarked “virtually its entire production budget to support the effort.” If Bart has evidence for this claim, he doesn’t share it. Without access to New Line’s accounts, we can’t be absolutely certain. Still, there is considerable evidence to the contrary. New Line executives have consistently pointed out that, spread over the three years of the trilogy’s release, their own annual investment was relatively small. Co-president Michael Lynne has said in a number of interviews that most of the budget was covered by other companies. In a recent issue of Screen International, he declared, “The foreign distribution rights alone were responsible for close to 70%” (Mike Goodridge, “The Ringleaders,” October 26, 2007, p. 23).

There were 26 foreign distributors, several of whom paid visits to the Wellington facilities during the production. I have talked with some of the filmmakers who took those distributors on tours. My book includes a case study of the Danish distribution company based on a two-hour interview with one of its executives (Chapter 9). During the years of the trilogy’s release, the trade journals, including Variety, ran stories about these distributors. The 70% figure, by the way, doesn’t count the merchandising licenses, many of which had been sold in 2000, helping to finance the trilogy. New Line was gambling, but largely with other people’s money.

Further, Bart declares, Shaye’s decision was a gamble because the narrative of Tolkien’s novel was so complex that it had previously scared off Spielberg, Kubrick, Harvey Weinstein, Saul Zaentz, and the Beatles (p. 51). Again, my research points in other directions. I have never heard that Spielberg was in the running to make Rings at any point. Stanley Kubrick was approached by Apple, the Beatles’ company, back in the late 1960s, when the Fab Four were interested in starring in a film adaptation of Rings. I suspect that it wasn’t the novel’s complexity that made Kubrick decline. (The Beatles got interested in transcendental meditation and went off to the Far East.) Bart says that Saul Zaentz “did little” with the production rights once he acquired them (p. 54). But in 1978 Zaentz produced an unsuccessful animated version of the first half of the book and decided not to make the sequel. Harvey Weinstein very much wanted to keep the Rings project at Miramax, but he was forced by parent company Disney’s head, Michael Eisner, to scale it back to a single two-hour feature. Peter Jackson refused to accept that condition and took the project to New Line.

Finally, Bart points out that Jackson was then a little-known director with not a hit to his name. True, but as I point out in my book, for the short time the Rings was in turnaround from Miramax, Jackson alone had the power to bring the project to New Line. Shaye undoubtedly wanted the rights to Rings, believing that it would make a successful franchise. Jackson came along with those rights.

Late in the chapter, Bart offers another reason why taking on the trilogy flew in the face of conventional wisdom: New Zealand is very remote from Hollywood (p. 63). Perhaps the distance caused some troubles, but it saved a huge amount of money—enough to make the difference between the trilogy getting made or not. In The Frodo Franchise I calculate (based on costs for a comparable effects-heavy epic, Titanic) that Rings might have cost roughly $544 million if made in North America (or $700 million if one includes the 120 minutes of extended-edition footage). Jackson undertook a similar estimate based on Pearl Harbor and came up with a figure of $180 million for Fellowship—and three times that is $540 million. The difference between those figures and $330 million pays for a lot of airline tickets.

Shaye’s “Gambler” Reputation

One of Bart’s conclusions is, “For those who, like Bob Shaye and Michael Lynne, believed that big returns emanate from big risks, Lord of the Rings provided a unique and generous validation” (pp. 63-64). This is peculiar indeed. I don’t think either Shaye or Lynne would agree with that assessment of their approach to production. Shaye was known for running a tight fiscal ship at New Line. His company became famous for turning miniscule investments into massive hits and franchises: most notably, Nightmare on Elm Street and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Shaye has a sign on his office wall that reads “Prudent Aggression.” That, I would say, is the attitude with which he approached the Rings decision.

Neither Shaye nor Lynne has generally encouraged the notion of the Rings deal as a gamble. (See my first chapter for more on this.) In the Screen International piece cited above, the interviewer asks that very question: “Do you agree that the trilogy was the riskiest venture that any film company has tried to date?” Shaye responds, “We had hedged somewhere between 70%-80% of our investment.” Lynne adds, “If it had broken even, nobody would have been happy. The company wouldn’t have gone out of business, but it definitely would have been a problematic issue for people who had invested with us, and for Time Warner itself.” (The investors were the international distributors who had pre-bought the entire trilogy.)

In an interview on The Charlie Rose Show earlier this year, Lynne said something similar: “The problem was, if the first film didn’t work, the next two were certainly not going to work, that these films would at best break even. Well, no one at Time Warner was going to be thrilled that we invested the three hundred million dollars and just got our money back! So although we weren’t betting the ranch, we certainly were betting our credibility.”

The gambler image no doubt redounds to Shaye’s advantage in some ways. He was the only one in Hollywood willing to take on the immense project when Jackson was shopping it around the studios. He was famously the one who told the director that he should make three films, not two. Despite occasional tensions between the filmmakers and studio executives, Shaye and Lynne not only stuck with the project but acceded to requests for tens of millions in additional spending. Shaye’s resulting image is that of a savvy maverick who outguessed the heads of the other studios.

On the other hand, it can’t be to his advantage to be perceived as reckless. If people think that Rings really was the biggest gamble in the history of Hollywood and that Shaye risked $330 million of his own firm’s money, blithely taking a chance on a director of splatter films, then he risks coming across as irresponsible. Hence, I suspect, his and Lynne’s care in informing interviewers that they had found investors and licensees to cover the bulk of the trilogy’s budget. Shaye has also pointed out that the trilogy stretched over three fiscal years, as I mentioned, making the annual investment in Jackson’s film modest relative to its epic qualities.

Of course the trilogy was a gamble. As Shaye said in the Charlie Rose interview, “But every film commitment is a gamble to some extent.” The size of this particular gamble, however, has been considerably exaggerated. Shaye and Lynne knew what they were doing. They saw the savings to be had by filming in New Zealand and by committing the cast members up front to all three films—hence obviating the possibility of ballooning salary demands if the first part was successful.

I’m sure there were many moments of worry and doubt in the years between New Line’s official announcement of the project on August 24, 1998 and the triumphant preview screenings at Cannes in May, 2001—when journalists and foreign distributors alike realized that the studio had, as Harvey Weinstein put it at the time, “another ‘Star Wars’ on their hands.” Still, I would place a small bet that during those same years the disastrous Town & Country (filmed in 1998 and released in late April, 2001) was giving Shaye and Lynne at least as much anxiety. That long-delayed film cost $90 million, with a publicity budget of $15 million. It grossed $10 million worldwide.

Above all, Shaye saw the likelihood of the trilogy’s success in a way that no one else did. My favorite statement of his was quoted in a Time article in late 2002, shortly before the release of The Two Towers. Asked why he had wanted three films instead of two, Shaye replied: “It was so wonderfully presold. It was like Superman or Batman.” Juxtaposing Tolkien’s novel with those comic-book superheroes might bring a smile—but he was right. If we can just set aside the persistent notion that Rings was a huge gamble, we can see that Shaye was remarkable for his foresight, not his recklessness.

I was, and may still be, a spy for the MPAA

DB here:

The Motion Picture Association of America is the trade association of the major film production and distribution companies. Founded in 1922, it helped the Hollywood studios maintain their control of the US industry and foster its business abroad. (See Kristin’s book Exporting Entertainment for an explanation of how it worked.) In 1945 the MPAA split off its international efforts and created a subsidiary, the Motion Picture Export Association of America, which helped the majors move in a systematic way into world markets. The current MPAA members are the Big Six: Sony (Columbia), Buena Vista (Disney), Universal, Paramount, Warner Bros., and Twentieth Century Fox.

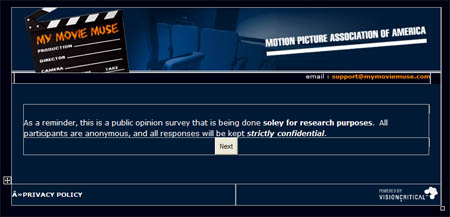

About fifteen months ago, the MPAA created a survey called My Movie Muse. Reading about it in Variety, I eagerly signed up. Every three or four months My Muse contacts me and asks me to answer some questions. At the end of the survey, I’m told that my name has been entered in a drawing for a gift certificate from Amazon.

I’ve never won. I’ve never heard who did. Maybe I won and the MPAA forgot to tell me.

The Movie Muse survey started last year with 7500 participants. You can join us by going to the website.

The initiative, according to MPAA head Dan Glickman, enables moviegoers to tell the industry their concerns.

People want to have input. They want to know that their movie viewing experiences are worth their time and money, and they want to know that our industry is hearing their criticisms and demands. In this age of participatory media, My Movie Muse will give consumers an opportunity to be heard.

Unfortunately, we Musers have little opportunity to say anything that doesn’t fall into a narrow set of multiple-choice queries. Let’s take a little drive through the questions. Beware the speed bump.

Eyes on your own paper, buddy

Every Muse form I’ve filled out is essentially the same, with a few seasonal variants. (What is your favorite Halloween movie?) The Muse announces that some questions will be repeated every few months “so that we can see how your opinions change over time.” You could perhaps make the Muse happy providing different answers at each iteration of the survey.

The Muse’s first clutch of questions involves your opinion of movies in general. Do you like ‘em or dislike ‘em? Do you think they’re better than they were in the 1990s? How do they compare with other forms of entertainment, like TV shows, videogames, and music? Do you like indies, kid movies, dramas, comedies, animation, documentary, whatever? How often do you see movies in theatres, rent DVDs, buy DVDs, or watch a movie online? How do you like the moviegoing experience in your local theatre? And so on. This is all pretty banal and anodyne, though I can imagine a firm using these data to help back up production decisions. (“See? I told you nobody likes Westerns.”)

The Muse proffers the Don’t Know option often, sometimes to puzzling effect. Is Don’t know really an appropriate answer to statements like the following?

Movies are often a topic of conversation among my friends.

I like to watch my favorite movies over and over again.

I use a DVR, iPod, computer CD or DVD burner on a regular basis.

Sometimes the inquiry turns Borgesian. Here’s one statement:

Movie plots are more predictable than they used to be.

If you don’t know, they’re probably not more predictable, at least to you. Another question asks:

Did you know that some movie theaters offer programs for frequent moviegoers, where you can earn free popcorn, sodas, and movie tickets depending on how many times you go to the theater?

The options are: Yes/ No/ Don’t know. Presumably if you don’t know, you’ll answer No. But if you answer Don’t know, does that mean that you don’t know whether you know?

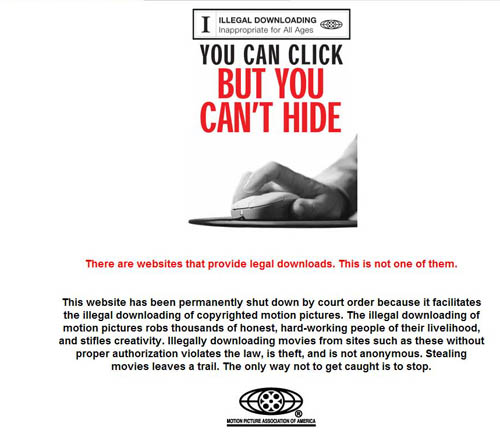

In any case, the speed bump comes up soon enough. Not to scare you, but maybe there’s some serious stuff ahead.

Don’t know what a slide rule is for

We’re eased into the hard questions gradually:

Are you aware of peer-to-peer file-sharing services that allow you to download full-length films or TV shows via the Internet for free?

Again we get Don’t know as an option, which isn’t really viable. Try telling an interrogator allowed to use harsh measures, I don’t know if I’m aware of peer-to-peer file-sharing services. . . But now there’s another option: Prefer not to say. Good choice. Too bad it won’t come up again.

We’re asked how often we download purchased movies and TV shows, download bootleg material, buy bootleg DVDs, copy DVD files to hard drives, and receive CD or DVD copies from a friend. The Muse is also curious about how often you copy such material to disc for a friend, or for your personal use. The permitted answers range from Never to 4 or more times a month. This menu may need revising; I suspect some of my friends pursue these activities 4 or more times an hour.

Anyhow, it seems likely that nearly everybody between the ages of 4 and 50 has done at least one of these things. You’d prefer to say Prefer not to say, but the only evasive tactic is Don’t know.

You recall the Perry Mason trick: After the sweating witness has testified, Perry asks, “Are you aware of the penalties for perjury?” Something similar happens here. Once the Muse establishes that you’ve surely broken the law, with relentless prosecutorial logic it asks if you did so willfully. Getting cozy in a Good Cop way, the Muse acquires a singular personal pronoun:

For each of the following activities, please tell me whether you think they are legal or illegal:

Copy a movie or TV show on a CD or DVD to give to someone else.

Go to a website and download a TV show you paid for.

Go to a website and download a full-length movie you paid for.

Copy files from DVDs onto your hard drive.

Buy a bootleg DVD.

Go to a file-sharing site and download a TV show for free.

Receive a copy of a movie or a TV show on a CD or DVD for your own use—to watch whenever you want.

But the statements are too bald and inexact. These activities aren’t necessarily illegal, according to intellectual property attorney Jim Peterson:

The work might be in the public domain (too old, registration or renewal failure) or it might be a fair use. You could conceivably download a movie as a fair use for your own scholarship without violating the DMCA prohibitions on defeating copy protection or removing copyright management information. The guy who cracked the copy protection on the DVD probably has some Digital Millennium Copyright Act problems, though. Same thing with buying a bootleg DVD. I don’t think buying is illegal; it’s selling that’s the problem.

Since the Muse’s questions don’t allow for such nuances, once more the Don’t know option is looking mighty attractive.

My Muse goes on to ask if any of the following considerations would affect your decision to undertake the illegal activities you’ve already mentioned. Now if you thought that they were all legal, or if you answered Don’t know, then presumably you don’t have to reply to what follows. In any case, imagine Penn Gillette reciting each of these possibilities in his most explosively disrespectful voice, with expletives freely inserted. Would you avoid breaking the law . . .

If official DVDs were $5 cheaper?

If tickets for the movie theater were $2 cheaper?

If a portion of the DVD price was contributed to charity?

If you were concerned that buying and downloading unofficial copies was tied to criminal activities or terrorism?

If friends or somebody in your community were being prosecuted for a similar activity?

If you received a notice warning you that you might be prosecuted?

If you got off with a wrist slap and a threat of future surveillance?

If you were made an example in order to deter other scum?

If specially-made DVDs carried an electrical charge of 50,000 volts to be shot into a user when s/he sought to copy them?

If certain DVDs were sprayed with microbes carrying sexually transmitted diseases?

Granted, I made up some of these, but maybe you can’t tell which ones. Anyhow, the correct answer is Don’t know, said quickly ten times with your hands over your ears.

Suppose you say you don’t download movies illegally. Then My Muse, not one to back off, asks why you don’t break the law. The lengthy set of options includes such noble justifications as I don’t have the time, I don’t know how to do it, I don’t like to watch movies at my computer, It takes too long, and I wouldn’t get the DVD bonus materials. For such freedoms brave men died.

The replies It is illegal and I’m afraid of getting prosecuted and sued come at the very end. Correct answer: Oh, riiight . . . It’s illegal. Sure . . . that’s it . . . Illegal. Of course, if the purpose of the questionnaire is not to find out what we think but to tell us what to think, then these questions come at the right moment. They tacitly say: All of the above-mentioned things you are doing, or are now thinking about doing, can be punished by lawsuits and a stay in the Big House.

The last page offers you a list of legal movie download sites, asking if you recognize or use any of them. I recognized most, but Guba and Vongo were new names to me. I don’t think I could bring myself to use any service, even for roto-rooting purposes, called Guba or Vongo.

Just as you’re ready to pack your toothbrush for the holding tank, the Muse gives a cheery farewell. “That’s it! . . .You’re done!”

When My Muse went online last year, industry observers noticed right away that the survey seemed more about selling people the MPAA’s line on copyright than about getting their responses. Anthony Kaufman, one of the dueling cavaliers of the cineblogosphere, wrote:

The leading questions are clearly part of a larger MPAA struggle to bolster copyright initiatives and crack down on fair use, file sharing and anything that threatens the bottom line of the international conglomerates. Dan Glickman may be the kinder, gentler face of the MPAA in the wake of Jack Valenti’s exit, but if his demeanor is softer, his goals are still just as nefarious.

This is a plausible interpretation. But I don’t want to rule out the possibility that the studios might really listen to my write-in request that they upgrade release prints and stick with 35mm instead of going digital. Or maybe the MPAA is branching out into online entertainment, like those commercials, quizzes, and snack-bar plugs that come up before the trailers. Is My Movie Muse a trial balloon for a new feature, DRM: Be Very Afraid?

Don’t know, Don’t know, Don’t know.

I’m not holding my breath for my Amazon certificate either.

Scribble, scribble, scribble

Detective (Godard, 1985).

Another damned, thick, square book! Always scribble, scribble, scribble, eh, Mr. Gibbon?

William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, 1781.

David here:

Kristin kept the blogfires burning while I traveled last week and did UW duties this one. I had a great time at the University of Georgia in Athens (but didn’t see Stipe) and at Emory in Atlanta (but didn’t see Scarlett). At both places I met sharp, energetic students and faculty. I have a couple of blog entries backlogged for posting, but now recent items relating to publications get the pole position.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

Second, the University of California Press is having a big sale on many outstanding media titles, from Richard Abel’s books on French silent cinema and André Bazin’s classics of film theory to Michele Hilmes’ study of NBC television and Mike Barrier’s new Disney biography, The Animated Man. To get the discount you must sign up for an e-newsletter, but it’s not intrusive.

Among the books of mine on sale, the biggest bargain is the hardcover edition of Figures Traced in Light (2005), originally priced at $65, now going for $7.95 plus postage. (No, apparently I don’t get the full-price royalties.) You can find this item here. There are also paperback copies of Figures (going for $12.95) and of The Way Hollywood Tells It ($15.95). If you’re inclined, hurry: the sale ends on 31 October.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

Bad news first. Poetics of Cinema is priced at $45 in paperback, with no sellers I know offering it at discount. Go ahead, say it: Very expensive. If you haven’t published a book, you may not know that authors have no say in the pricing of their work. Publishers would never set a price or price ceiling in a contract, and calculations about pricing are based on many factors, including what comparable books sell for. A high cost isn’t my preference, of course; every writer wants to reach as many readers as possible. But unless you blog or self-publish your work, the publisher sets the price.

There are some good reasons for the cost. Running to 500 fairly dense pages and containing over 500 photographs, Poetics of Cinema was a complicated book to produce. I peddled it to other publishers, but they ruled it out as too whopping an investment for them. So Routledge has priced it along lines of comparable books, reckoning in the size of the likely audience (I hope, more than 118.3 readers). I have to thank Bill Germano, then Publishing Director at Routledge, for taking a chance on this project.

From age fifteen or so I’ve been a compulsive writer. Scribble, scribble, scribble. I’ve been at work on one book or another for over thirty years. I’ve got several projects in mind for my next effort, but I’ve held back committing. Is there any point in publishing more books, at least as books?

I mean this as a serious question. Would it have made any difference to me or my readers if Poetics of Cinema appeared as pdfs, available at a price considerably less than $45? Wouldn’t I find more readers? What about variable pricing? If Radiohead can do it, why can’t I? Somebody in film studies should try putting a digital book for sale online; maybe I will. But for a few years at least, this last baggy monster will be available only in dead-tree format.

Poetics: Some puzzles

Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (Richard Sale, 1955).

If you’ve read this far, you may be interested in what the book is about. Most basically, it’s predicated on the belief that we make progress in research by asking questions. Some questions are too deep to be answered—call them mysteries—but others can be answered with a fair degree of precision and reliability. We can turn mysteries into puzzles and puzzles into plausible answers.

Here’s a fairly common sort of composition in Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. This shot from The Killers (1946) displays the sort of steep depth I’ve talked about at various points on this blog and in my other books.

But now here’s an equally tense confrontation at a counter, from Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), made in early CinemaScope.

It doesn’t look much like the 1940s shot. The characters stand far from us, and the figure in the foreground doesn’t loom over the background. The shot is more open, the composition more porous. And unlike The Killers, Bad Day doesn’t contain close-ups of the actors in any scenes.

So questions come to mind. Did John Sturges have to stage the scene in Bad Day this way? Did other filmmakers resort to the same choice? What factors created pressures toward this more spacious format? Could more resourceful filmmakers have done something different? And given that such shots are rare today, what changes made it possible for filmmakers in later years to create the tight anamorphic widescreen close-ups we have now (as here in Cellular)?

Despite all that has been written about CinemaScope and other early widescreen processes, no one has explored, shot by shot, what staging options were used by filmmakers. A chapter in Poetics of Cinema called “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses” tries to show how filmmakers used the new format to tell their stories. This led them, I propose, to experiment with some staging strategies that, surprisingly, had precedents as far back as the 1910s.

Take another instance. We’re all familiar with recent films that present alternative futures, like Run Lola Run. A story line runs along and then is interrupted, and we switch to the same characters living a different storyline in a parallel universe. The emergence of such “forking path” movies arouses my curiosity. How do they work? How do they make their alternative-reality stories intelligible to the audience? How is it that we’re able to understand them? (After all, the notion of an infinite number of alternative universes to ours is pretty hard to get your head around.) Are such stories a brand-new innovation, or do they have precedents? (Clue: Remember A Christmas Carol?) Why do we see a cluster of these emerging in recent filmmaking?

I tackle these questions in another essay, called “Film Futures.” There I look at several such movies and try to spell out the tacit rules that filmmakers follow and that audiences pick up on. While this story format probably doesn’t constitute a genre, it does obey certain conventions, and I try to chart those. Some films also make some clever innovations in the format, which I also try to trace. The essay as well suggests how the conventions are handled differently in mass-market films like Sliding Doors and in art films like Kieślowski’s Blind Chance.

These two essays, along with the others in the book, try to explain and illustrate an approach to film studies I call film poetics. At bottom, this is an effort to explain why films are designed the way they are: how filmmakers have made certain choices in order to shape our response to their films. How do movies work? How do movies work on us?

Poetics: The project

Vagabond (Varda, 1985).

As a kind of reverse engineering, film poetics looks at both structure and texture. I argue that we ought to study how films are constructed architecturally, as revealed for instance in plot structure or narration. Poetics also concentrates on stylistic patterning, the way filmmakers organize the techniques available to the medium. Poetics traditionally deals as well with thematics, the subjects and ideas that are mobilized by filmmakers and reworked by large-scale form and cinematic style.

Put it this way: I want to know how filmmakers have confronted problems set by others, or created problems for themselves to solve. I want to know how they draw on the past to borrow or modify or reject creative strategies. I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, including the ones they don’t know they know. And I want to know how all this creative activity is shaped to the uptake of spectators in different times and places.

Some of what I’ve written on this blog could illustrate how the poetics-driven perspective works in particular cases. The book offers more such instances, probed in more detail than is possible here. Using a comparative method, I also trace out some general principles of film form and style as they have developed over history.

The book consists of fifteen essays. Some have been published before; those have been revised for this collection. Other essays are newly written. After a somewhat polemical introduction, the first part concentrates on some theoretical problems. The anchoring essay offers a general introduction to the idea of a film poetics, with several examples. (An earlier version is on pdfs here.) In the same essay, I float a model of how film viewers respond to various aspects of films. I distinguish activities of perception, comprehension, and appropriation, and I suggest that a cognitive perspective sheds light on them.

Part I also contains an essay considering how cinematic conventions work. A poetics-based approach will spend a lot of time on norms, traditions, and received routines, for these are often the basis of filmmakers’ creative choices. This essay argues that some conventions are local and require a lot of cultural knowledge, while others are cross-cultural, compelling us to study why certain cinematic strategies seem to crop up across the world.

The second part of Poetics of Cinema considers narrative, one of the most common ways in which films are organized to affect viewers. I wrote a new essay to launch this section, a wide-ranging study called “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” The three dimensions I consider are narration, plot structure, and the narrative world. The essay considers how each of these shapes our understanding of a film’s story. This essay ends with a discussion called “Narrators, Implied Authors, and Other Superfluities.”

Some more tightly-focused pieces follow. One is devoted to forking-path plots. Another concentrates on an odd question: What role does forgetting play in our watching a film? Cognitive theory can offer some answers, and I take Mildred Pierce as an example. There’s an update of an essay that has been something of a golden oldie in film courses, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” In a supplement to that piece I suggest some new avenues of inquiry and draw on more examples, notably Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi).

The longest piece in Part II is devoted to what I call network narratives. Prototypes of this would be Grand Hotel, Short Cuts, Crash, and Babel. This essay tries to show how a poetics of cinema shed light on this format, currently a very popular one. When I started looking at these movies, I was surprised to discover how many filmmaking traditions work in this vein; I append a filmography with nearly 250 items, and today I could update it with several more. (1) I consider how this option has developed distinctive strategies of narration, plotting, and worldmaking. I also survey some common themes running across network tales, such as the role of chance and fate. The essay finishes with more in-depth analyses of four films: Altman’s Nashville, Iosseliani’s Favoris de la lune, Anderson’s Magnolia, and Jean-Claude Guiget’s Les Passagers.

Poetics: More problems

Bus Stop (Logan, 1955).

Part III moves from questions of narrative to questions of film style, no stranger to this blog. The opening essay is a tribute to Andrew Sarris that appraises his role in making readers of my generation style-conscious. It’s the most personal piece in the book. There follows a study of Robert Reinert, a director in the German silent cinema who might have become much better known if his quite demented Nerven and Opium had been as widely seen as Caligari. The essay “Who Blinked First?” considers how our reaction to films is affected by the ways in which actors use their eyes, including how and when they blink. Big deal, huh? Actually, yes.

The monster essay in this section is the CinemaScope piece, of which I’ve given versions in lecture form over the last couple of years. I argue that some directors responded to the new widescreen technology by adapting certain norms of staging and shooting to the new format, while other filmmakers moved in more adventurous directions. The piece uses the model of problem/solution as a way to understand stylistic continuity and change, a framework I’ve floated in On the History of Film Style as well.

The last four studies in Part III are devoted to style in Asian cinema. There are two essays on Japanese film of the 1920s and 1930s, both expanded somewhat from their original versions. There I argue that we can see Japanese directors as building upon, as well as adventurously departing from, stylistic norms shared by most filmmaking countries of the period. This brace of essays fills out some ideas that I fielded in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, and they should appeal to that growing body of viewers who have developed a passion for Naruse Mikio and Uchida Tomio. It’s gratifying that several of the films I discuss, which I had to study in archives, are now circulating in touring programs.

Poetics of Cinema concludes with two studies of Hong Kong film, one surveying the stylistic tactics by which that very lively tradition excites its audience, the other analyzing the unique innovations of King Hu. The articles are companion pieces to Planet Hong Kong.

Poetics: The mysteries

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

As an approach to answering questions about cinema, poetics blends history, criticism, and theory. It requires that we do research into the artistic history of film, looking at styles, genres, narrative modes, and other traditions. It asks for close analysis and interpretation of films. At the same time, it asks broader questions about what principles govern narrative, stylistic patterning, and the like. I’d say it obliges a historian to concentrate on aesthetics; it makes criticism more historical and theoretical; it ties theory to concrete historical conditions and the fine-grain workings of individual films.

Kenneth Burke used to say that you could get a sense of a book by looking at its first and last sentences. My book’s first essay opens this way:

Sometimes our routines seem transparent, and we forget that they have a history.

I think that this captures my concern to look closely at familiar things in film and try to make their principles a little more evident. Yet in trying to make filmmakers’ choices explicit and tracing out the principles undergirding how we make sense of movies, I’m sometimes criticized for simply stating common sense. Poetics can look bland alongside the skywriting swoops of most academic film theory. But skywriting is blurry and dissolves while you look at it. By contrast, clearly setting out some basics of filmic construction and comprehension offers a firmer place to start answering questions about how movies work and work on us.

Poetics tries to produce concrete, approximately true claims about cinema. Most film theory operates as an application, borrowing big theories of culture, identity, nationhood, and the like and then mapping them onto films. The results are usually thin. It seems to me that most film theory today is not carefully thought through or persuasively argued. For examples, see my essay in Post-Theory, the last chapter of Figures, and my comments here and here on this site.

In trying to establish reliable knowledge about cinema, we won’t answer every question and we will make false steps, but we can make progress. Film poetics is one way we film enthusiasts can join that tradition of rational and empirical inquiry which remains our most dependable path to knowledge. My introduction, though peppered with some pokes at Big Theory, has the serious purpose of making a plea for film scholars to join that tradition.

The final line of the book concludes the essay on King Hu:

The mainstream [Hong Kong] style has given us many beautiful and stirring films, but Hu’s eccentric explorations evoke something that other directors’ works seldom arouse: a sense that extraordinary physical achievement, if caught through precisely adjusted imperfections, becomes marvelous.

To get the full point you need to read the essay, but what should come through here is my concern to highlight filmmakers’ originality when I find it, and to locate it by means of a comparative method. In addition, I hope that what comes through is an appreciation of the sheer exhilaration we feel when a filmmaker has made the right, bold choice. A poetics-based approach probably can’t fully explain this feeling—it may fall under the heading of mysteries rather than puzzles—but at least it can reveal how some forces contribute to it.

My summary, and the size of the book, may leave the impression that I think that I’ve answered these questions fully. Of course I don’t. I try only to make some progress, realizing that offering answers is also an invitation to disagree, to refine the questions and tackle new ones. Nor do I think that these are the only questions that matter. We’re just starting to understand how films work and work on us, and there are a great many areas we haven’t charted. (Performance, to take a big one.) We have to start somewhere, though. I’d hope that by posing some questions and proposing some answers, Poetics of Cinema offers fruitful points of departure.

(1) Some candidates are 25 Fireman Street (1973, Hungary, István Szabó), Feast of Love (2007, US, Robert Benton), Continental—A Film without Guns (2007, Canada/ Stephane Lafleur), The Edge of Heaven (2007, Germany/ Turkey, Fatih Akin), Unfinished Stories (2007, Iran, Pourya Azarbayjani), God Man Dog (2007, Taiwan, Singing Chen [Chen Hsin-hsuan]), A Century’s End (2000, Korea, Song Neung-han), and Why Did I Get Married? (2007, US Tyler Perry).

A Moment of Innocence (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996).