Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Christian Bale picks up a rail

DB here:

In James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma, some law officers are taking the captured killer Ben Wade (Russell Crowe) to the farmhouse of Dan Evans (Christian Bale). When the stagecoach sinks into a rut, Evans limps out of his house, snatches up a fence rail, and uses it to pry the wheel free.

Not an earth-shattering moment, but one I got to know pretty well last week when I visited the mixing session as the director’s guest. About a year ago, Jim sent me an email expressing his liking for my book The Way Hollywood Tells It. We kept corresponding through the planning and production of Yuma, and last month he asked me if I wanted to see the picture-locked film and visit a sound mixing session.

As we say in Wisconsin: You bet.

Watch their eyes

Mangold has been prolific, turning out seven films in about twelve years. Heavy, CopLand, Girl, Interrupted, Kate and Leopold, Identity, and Walk the Line nicely illustrate the difference between convention and cliché. While embracing each genre’s conventions, Mangold always tries to enlarge, enrich, and explore them. Where other directors try for brute impact, he seeks out implication and understated lyricism. Above all there are the nuanced performances, female ones in particular. (Remember those Oscars for Angelina Jolie and Reese Witherspoon.) If anybody can bring the psychological nuances of that elusive “indie sensibility” to mainstream filmmaking, James Mangold is a likely candidate.

As a writer-director, he balances concern for story and character with a carefully wrought visual style. The opening of Heavy makes a shabby tavern beautiful through precise compositions and geometrical cutting that recall Ozu, whom Mangold has acknowledged as an influence.

At the same time, he has understood one of the great strengths of the Hollywood tradition—letting the actors’ faces tell as much of the story as possible. He believes that the script should include not only dialogue but also “pieces of silent acting.” John Ford remarked of actors: “Watch their eyes.” Mangold’s version of this precept can be found on the DVD commentary of Girl, Interrupted: “Actors dance with their looks and glances.”

In fact, his commentary tracks are gold. Anybody who wants to know more about the craft of writing and directing should simply sit down and listen. Mangold is not one of those I-do-what-I-feel guys; he channels the story’s feeling into precise, writable and filmable moments, and his commentary tracks explain how he does it.

Delmer Daves’ original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) is one of Mangold’s favorite films, as he explained several years ago in the interview with Tod Lippy that prefaces the published screenplays of Heavy and CopLand. He’s been bold enough to remake it, in an era in which Westerns are supposed to be unpopular. I was keen to see what a director renowned chiefly for intimate psychological dramas would do with a Western. Yet maybe the gap isn’t so great after all. Mangold points out in the Lippy interview that most classic Westerns aren’t action pictures but character studies.

In the shadow of John Ford

The Yuma production has been chronicled elsewhere on the internets, so I won’t rehearse it here. I came in on the third day of mixing. The session was held on the Twentieth Century Fox lot, at the John Ford theater (a lucky spot, surely). Mangold, his editor Mike McCusker, and half a dozen sound specialists had already been working through the morning. The team included the lauded sound rerecording mixer Paul Massey, winner of three BAFTAs and recipient of five Oscar nominations. His work includes Nixon, Clueless, Gattaca, Jerry Maguire, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, the second and third Pirates of the Caribbean films, and not least, the wonderful SCTV parody The Last Polka.

For me, it was an intensive four-hour seminar. Once I start to focus on a movie soundtrack, I have to marvel at the level of precision you can find. As we tell our students: It’s hard to really watch a movie, but even harder to really listen to it.

When Jim asked if I’d sat in on a mix before, I had to confess that I’d visited only one—a session in which Walter Murch was blending rustling foliage and mosquito noises for a scene in Apocalypse Now. (Must blog about that some day.) Things had changed a lot since the 1970s. No longer was a scratchy black-and-white print run and rerun; now we get a 4K image on a large screen, crisp and bright and frozen on a frame for as long as you like. Now there are several mixing stations, each one with a glowing Mac monitor alongside.

The standard division of labor endures, but it’s much more refined. Music is filed on many tracks and with a few mouseclicks can be reworked in tempo, timbre, and orchestration. The dialogue tracks consist of thousands of stored line readings, ready to be pulled up in moments. As for sound effects, at this point Yuma had 96 effects tracks, each of them already premixed from many sources. I usually notice the impact that the digital revolution has had on camerawork and editing, but this session really drove home to me the ways in which the computer has made the art of the soundtrack more exact and exacting.

Details, details

Most of the session was devoted to effects. The first problem was that the track seemed to Mangold too “absent,” too thin and empty. Mike remarked that he didn’t feel the atmosphere, the air between the more discrete noises. “There’s nothing of any character that’s holding it all together,” Mike said. The difficulty, though, as Jim pointed out, is that if you simply add in more sounds, you can confuse things. “If we hear just one moo, that becomes an event.” How to thicken the acoustic atmosphere without muddying it or creating competing noises?

Step by step, the team filled in the ambience. They added tiny air currents, always seeking to avoid what Mangold called “radio wind.” We got very soft and distant moos, shifting horse hooves, even low “horse vocals.” After it was all blended, I found the ambience full and modest, but Jim and the others felt that it was still too bright. They would go back later and mute it a bit.

Now that the ambience was fleshed out, the rest of the session was devoted to specific effects and a few lines. Jim asked for a heaving sound as the stagecoach burst out of the rut, more jingling on the coach reins, a little clinking on Russell Crowe’s handcuffs, a gun-cock. When Crowe’s henchman (Ben Foster), watching from the ridge, urges his horse to move, he makes a smootchy tsk-tsk; Mangold wanted to give it a slightly mocking edge, suggesting the killer’s disdain for the guards’ efforts to protect Wade.

During the 1990s I’d noticed the greater detailing of movie soundtracks. I heard garments brushing against sofas and flakes of tobacco crackling when someone lit a cigarette. Now I was seeing and hearing how skilled artisans orchestrated thousands of such sonic micro-events. They clarified a muffled line. They inserted the sound of stagecoach springs shifting. The words “Good luck” were shifted eight frames. At one point Jim asked for a new line to be put in. “We need a ‘Let’s go.'” “Should I steal it?” “Steal it.” How much of this would be heard in the typical multiplex, or even in fancy home theatres? These guys were going all the way down, creating something of great finesse.

Jim reminded me that sound can create a sense of visual momentum too. The coach drives off in two shots, a long shot and an extreme long shot, and Mangold thought it seemed to go a bit faster in the second. So he added noise that gave an accelerating launch to the first shot.

Then there were Mr. Bale’s steps and the rail he picks up, which gave me an acoustic hallucination.

David is hearing things

As Dan Evans limps out of the cabin (he was wounded in the war), Jim found his footsteps too thudding. He wanted to hear that they were “grounded,” that there was some loose earth underfoot. The team worked to add the textures of pebbles and grit as Evans makes his way to the coach. The action was replayed many times. As the texture thickened, the fence rail that Evans grabs started to sound different to me. At first it was a soft but distinct scrape against the ground; at the end of the mix, it had a faintly twangy timbre. I congratulated the team on giving the rail its own little moment.

They looked at me. They hadn’t done a thing to the rail.

Two explanations arise, maybe both correct. (1) The sound team said that constantly replaying a clip can create such little mirages. Faced with so much repetition, maybe the mind needs to project some variation into it. (2) Changing the texture of the whole scene can alter our sense of the individual, unchanged elements. If there was a little twang to the rail, perhaps it came from overtones or other emergent qualities of the mix.

Maybe too, in my third hour of concentrating on minutiae of the track, I was getting oversensitive to sound.

Realism and convention

After the stagecoach drives off, Wade and the men guarding him trudge into Evans’ cabin. There’s a short scene with Wade and his wife, and that too needed its ambient filling in. I noticed that the banker, first glimpsed inside the cabin, is somewhat closer to the couple a few shots later. Jim noticed it too. In a jiffy three or four very soft bootsteps and slightly creaking boards were added, so that subliminally we were prepared to see the banker on the porch.

Night falls and two of the men guarding Wade are lingering on the cabin porch. It was simple dialogue, filled out with the atmospheric sound. The sound mixers had to redo one actor’s line reading, yanking an alternative out of the files. Jim still wasn’t satisfied and thought they might reloop the line later. Most interesting was Jim’s idea to add some softly clinking dishes to the tail of the scene, preparing us for the cut inside to Evans’ family at dinner with Wade. In these ways, barely perceptible sound smooths over cuts and shifts of point-of-view.

In the course of all this, as Paul and Mike and the others were fixing things, Jim came back to talk with me. He answered my questions and we chatted about directors, mostly Spielberg. Close Encounters is a favorite of his, and he pointed out ways in which it’s been influential on a range of other movies. He also showed how aware he is that realism in sound goes only so far and that pure conventions often kick in. In a movie, when somebody hangs up a phone abruptly, the person on the other end hears a dial tone. Does that ever happen in life? You just get silence. But the dial tone conveys a stronger sense that the line has been broken.

In the course of all this, as Paul and Mike and the others were fixing things, Jim came back to talk with me. He answered my questions and we chatted about directors, mostly Spielberg. Close Encounters is a favorite of his, and he pointed out ways in which it’s been influential on a range of other movies. He also showed how aware he is that realism in sound goes only so far and that pure conventions often kick in. In a movie, when somebody hangs up a phone abruptly, the person on the other end hears a dial tone. Does that ever happen in life? You just get silence. But the dial tone conveys a stronger sense that the line has been broken.

Jim halted the session as the family dinner scene began. The team would continue to polish it, and he’d be back tomorrow to keep going. I snapped a picture of him just before he left. Later, I caught up with Mike McCusker, who also edited Walk the Line. He has an enormous respect for Mangold, saying that his success with female performers was reminiscent of Cukor’s accomplishments.

Next day, watching the premix version of the whole movie, I saw Christian Bale limp thuddingly to the coach. Almost no moos or jingles, and definitely no clinking crockery. No twang when he picked up the rail. You almost never get a chance to notice this sort of before-and-after differences on soundtracks, and it brought home to me how much skill and effort would go into reworking every scene. Making movies is really, really hard work. And I remembered another reason I like movies: They sharpen your senses.

Coming attractions

I plan to write more on 3:10 to Yuma in a few days. In the meantime, Kristin may be posting her experience at another mixing session–that one in Wellington, New Zealand in May. Over the next week we’ll also be filing reports from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. Sign up for a feed if you want to keep abreast of developments.

Once more on New Line, Peter Jackson, and The Hobbit

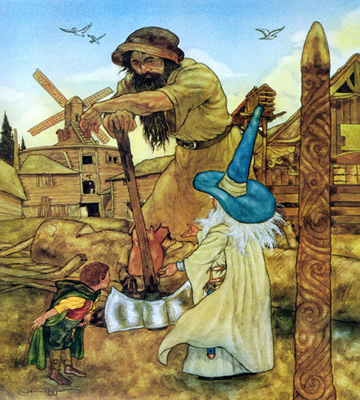

Gandalf introduces Bilbo to Beorn. Illustration by Michael Hague

Kristin here–

After several months of raised and dashed hopes, the question of who will direct the film of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit remains open. I first weighed in on the question back on October 2 of last year, when this blog was in its infancy. MGM had just announced that they would be making The Hobbit and hoped that Peter Jackson would direct. At that point I was trying to sort out Peter Jackson’s large number of film projects and to explain how his schedule might include time to direct The Hobbit.

Subsequently there was a clarification. MGM, which owns the distribution rights to any film version of the novel, would co-produce with New Line, which produced The Lord of the Rings and owns the filmmaking rights for The Hobbit.

Then, early this year, New Line founder and co-president Bob Shaye declared in an interview that Jackson would never direct The Hobbit while he is in charge of the company. The obstacle was a lawsuit that Jackson had filed against New Line; he wanted an accounting of earnings on the DVDs of The Fellowship of the Ring and various licensed products. See my January 13 attempt to explain all that.

As before, no doubt negotiations are going on behind the scenes. To reiterate my disclaimer from the earlier entries, I have no inside information, given that my contact with Jackson and the other filmmakers was back in 2003 and 2004, during the research for The Frodo Franchise. As someone who has followed the situation very closely since undertaking my book back in 2002, however, I can make what I hope are some enlightening comments on the scraps of news that have appeared since January.

A faint hint that Shaye might possibly be backing away from his absolute rejection of Jackson as director for The Hobbit came in a brief interview in the April issue of Wired (also online). As far as I could tell, this went largely unremarked at the time. The first two questions related to The Last Mimzy, the children’s fantasy directed by Shaye, which was then being released to what proved to be disappointing box-office results. Inevitably, though, the interviewer switched to the Hobbit situation:

You recently said Peter Jackson would never touch The Hobbit while you were at New Line.

You know, we’re being sued right now, so I can’t comment on ongoing litigation. But I said some things publicly, and I’m sorry that I’ve lost a colleague and a friend.

Is The Hobbit still a viable project?

I can only say we’re going to do the best we can with it. I respect the fans a lot.

Shaye’s statements might be seen by some as implying that he regretted his rejection of Jackson as a director. Given that the vast majority of fans want Jackson to direct, the last sentence seems to offer hope that Shaye might relent and bow to their wishes.

A greater stir was caused by Entertainment Weekly’s April 16 announcement that Sam Raimi had expressed interest in directing The Hobbit—a possibility that had been circulating widely as a rumor since shortly after Shaye’s January pronouncement. As I suggested in my previous entry, however, most directors would shrink from upsetting Jackson and his fans by simply taking the job. Raimi made it clear what circumstances would be necessary: “First and foremost, those are Peter Jackson and Bob Shaye’s films. If Peter didn’t want to do it and Bob wanted me to do it—and they were both okay with me picking up the reins—that would be great. I love the book.” (Raimi presumably refers to films in the plural because MGM had suggested in September that it was considering a two-part adaptation.)

Raimi risked riling not only Rings fans but Spider-Man afficionados, who were upset at the idea that he might bow out of a presumed fourth entry in his own franchise. In the nearly two months since Raimi’s statement, there has been no public indication that he is being seriously courted to accept the job directing The Hobbit.

Jackson, however, has been busy. The projects on his plate have changed considerably since early October. Only a few weeks after my summary, Universal and Twentieth Century Fox, which had been on board to finance the video-game-to-film adaptation of Halo for co-production by Jackson and Microsoft, bowed out. The project is now on hold, with the assumption that the release of the Halo 3 game, announced for September 27, will regenerate studios’ interest.

The remake of The Dam Busters is moving forward, but it is being directed by Christian Rivers rather than Jackson, who serves as producer. The acquisition of Naomi Novik’s “Temeraire” series by Jackson and partner Fran Walsh, announced September 12, apparently has not resulted in a specific project. The pair presumably have the option of making it into a film at some future date or letting their option lapse.

The project that has made great progress is Jackson and Walsh’s adaptation of Alice Sebold’s bestseller The Lovely Bones. Their script was up for bids this spring, and on May 4, Variety announced its sale to Dreamworks. Reportedly the film will be delivered by the fourth quarter of 2008. It might be possible to commence pre-production work on a Hobbit film while The Lovely Bones is in progress.

Less than two weeks later, Variety revealed that Steven Spielberg is teaming with Jackson to produce three feature films based on the classic Belgian comic books starring Tintin. Each plans to direct one of the features, with a third director undertaking the other.

In October I suggested that most of Jackson’s projects were flexible in their timing, and that left the possibility that he could shift them around to fit in The Hobbit. Given that no timing has been announced for the Tintin films, Jackson’s only apparent project with a deadline is The Lovely Bones.

Finally, at the Cannes Film Festival, Shaye and co-president of New Line Michael Lynne spoke to Variety’s editor-in-chief, Peter Bart, about the Hobbit project. Their remarks might give Rings fans cause for hope.

Shaye maintained his stance, declaring that New Line had paid Jackson and Walsh $250 million in profit participation. “The clash happened because ‘one of us has gotten poor counsel,’ Shaye said, without elaborating.”

The story continues: “Co-chief Michael Lynne struck a more upbeat note. ‘We do want to settle our dispute and I think we will.’” Neither would comment on the rumors that Raimi was being wooed for the Hobbit adaptation. When asked about Raimi, Lynne replied, “There’s never been any announcement.” Shaye added, “Like a lot of people, he might.”

I think there are two major factors underlying this feud between Jackson and Shaye that haven’t been pointed out and need to be. First, lawsuits of the type Jackson brought are pretty common in Hollywood. Second, Shaye is perhaps forgetting the amount of personal investment and financial risk Jackson took to get Rings made—investments that cost New Line nothing but which brought in a hugely successful film on a surprisingly low budget. (I explain how in the first chapter of The Frodo Franchise.)

Jackson’s isn’t even the first suit against New Line by someone central to the film’s making. Independent producer Saul Zaentz sold the adaptation rights to Miramax back in 1997, and that company in turn sold them to New Line in 1998. As part of these deals, Zaentz was to receive 5% of gross international receipts. He sued, claiming that the $168 million paid to him was calculated on net receipts, leaving a balance of $20 million owed him. The suit was to come to court on July 19, 2005, but New Line settled for an undisclosed amount shortly before that. The same thing could happen in Jackson’s case, and the settlement could come at any time.

Zaentz isn’t the only other person claiming to have been shortchanged by New Line. On May 30 of this year, a group of fifteen Kiwi actors filed a suit claiming that they had not been paid the 5% of net merchandising revenues for products bearing their likenesses. (The group includes Sarah McLeod, who played Rosie Cotton, Craig Parker, who played Haldir, and Bruce Hopkins, who played Gamling.) The suit isn’t likely to reach court soon, if ever, but Jackson isn’t alone in his doubts about New Line’s accounting practices.

Moreover, Jackson and Walsh spent an enormous amount of their own money upgrading the filmmaking firms in Wellington to make them sophisticated enough to handle all phases of Rings’s production. Weta’s two halves, Digital and Workshop, of which the couple owns a third, were vastly enlarged. Jackson and Walsh bought the country’s only post-production facility, The Film Unit, when it was for sale and under threat to be moved out of New Zealand. They went into debt to do that, and it, too, was enlarged and moved into a huge facility full of highly sophisticated equipment. Much of this expansion was paid for with the money Jackson received for making Rings.

The result was a trio of films that grossed nearly $3 billion internationally, as well as untold additional revenues for the DVDs, video games, and other ancillaries. New Line went from a small subsidiary of Time Warner known mainly for its Nightmare on Elm Street series to a well-respected company making prestige films like Terence Malick’s The New World and the upcoming The Golden Compass, an adaptation of the first novel of Phillip Pullman’s award-winning trilogy. Oh, and there’s the matter of the seventeen Oscars Rings won. Previously New Line, founded in 1967, had won two.

In the wake of Rings, Jackson was faced with having to keep Weta, The Film Unit (now renamed Park Road Post), the Stone Street Studios, and his WingNut production firm going. Beyond the physical facilities, which no doubt involve enormous overhead costs, there are the many hundreds of employees to be paid. New Line did not invest in these facilities. Jackson and Walsh, along with their partners Richard Taylor and Jamie Selkirk, did.

When I first visited Wellington, there was a question as to whether there would be enough business to keep the facilities going and the employees in work. King Kong helped in the short run, but would other big films follow? Since then, Weta Workshop has diversified and is thriving. Weta Digital gets regular work doing the CGI for large numbers of shots in such films as X-Men 3: The Last Stand and Eragon. James Cameron’s decision to make Avatar in Jackson’s facilities seems the final seal of approval. Weta Digital is now widely considered one of the top digital effects houses in the world, alongside such firms as ILM, Sony’s Imageworks, and Rhythm & Hues.

Now the Wellington facilities all seem to be doing well. Nevertheless, in the era before Rings’s release and huge success, Jackson took as big a risk as Shaye did. Maybe bigger. Shaye might ponder that as he decides what to do about the Hobbit project. He owes the Kiwi filmmaker gratitude for more than simply directing a runaway hit.

Beyond that, unless New Line has short-changed Jackson very badly through its accounting procedures (and all that would presumably come out eventually when the suit finishes up), the added value provided by the director’s name on a Hobbit film would surely be at least as great as the money owed. Unless there is some major unknown factor influencing Shaye’s decision, he would do well to tamp his resentment, make peace, and initiate a project that is as close to a guaranteed mega-hit as anything can be these days. He could settle out of court, as he did with Zaentz, and just get on with it.

[Added July 21: For my update on the Hobbit film, go here.]

[Added August 6: For my earlier comments on the Hobbit film, go here and here.]

Can you spot all the auteurs in this picture?

DB here:

Some movies consist of several distinct episodes, each directed by a different filmmaker and all focused on a single theme. I’ve heard them called anthology films, omnibus films, and portmanteau films.

The earliest one I know is If I Had a Million (1932); later, Hollywood offered us Ziegfeld Follies (1946) and O. Henry’s Full House (1952). The Brits gave us the horror anthology Dead of Night (1945). Still, I think we associate the form chiefly with European cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. We got Love in the City (1953), Amori di mezzo secolo (1954), The Seven Deadly Sins (1962), RoGoPaG (1963), Les plus belles escroqueries du monde (1964), Paris vu par . . . (1965), Three Faces of Woman (1965), The World’s Oldest Trade (1967), and Amore e rabbia (1969).

Why the emergence of omnibus movies at this point in history? Some causes are surely financial. Most high-budget European films of the period had to be cross-national coproductions. Bringing in directors from several different countries could help guarantee funding under EU auspices and participating nations’ subsidy schemes. Just as important, the anthology format appeared when the festival scene was starting to become a vast clearing house for international film trade.

Although you can argue that many people seeing If I Had a Million would recognize the Lubitsch episode, Hollywood’s use of the form didn’t stress directorial differences. But as the Euro auteur was becoming a marketable commodity in the postwar era, a collection of short films could sell if they were signed by big-name filmmakers. “Paris As Seen by…” signals the importance of the different directorial approaches, and the very title of RoGoPaG invokes Rossellini, Godard, and Pasolini as brand-name labels. (Granted, the final G, Hugo Gregoretti, didn’t add much to the deal.)

For full enjoyment, the 1960s portmanteau film requires a degree of specialized film knowledge. At one level, we enjoy varied treatments of a theme, but at another we’re supposed to recognize each director’s personal vision, as we know it from other films. Even political-commentary portmanteau films like Far from Vietnam (1967), Lucía (1968), and Germany in Autumn (1978) gathered international attention because of the name recognition of the filmmakers who participated. The same branding operates in New York Stories (1989) and, more openly, in the documentary 12 registri per 12 città (“12 Directors for 12 Cities,” 1989).

The format has returned recently. We’ve had 11’09”01—Sept. 11 (2002), Eros (2004), Tickets (2005), and Paris, je t’aime (2006), the last virtually a rebooting of Paris vu par . . . . As we’d expect, such films continue to highlight the personal signatures of festival familiars. But we can spot some new twists too.

For one thing, the unifying idea may be formal as well as thematic. The episodes of 11’09”01 were all obliged to be the same length, eleven minutes, nine seconds, and one frame. Lumière et cie (1995) not only celebrated the centenary of film but obliged the directors to make their entries with a Lumière camera, to shoot without sync sound, to shoot no more than three takes, and to restrict the length to 52 seconds, the approximate running time of the earliest films. The Lumière homage also introduces the key themes of cinema and cinephilia, an angle that doesn’t seem prominent in the 1960s omnibus movies.

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

A half-dozen things strike me while watching the French DVD version (which has English subtitles but is unaccountably lacking the Coens’ entry). Most notable, I suppose, is the way that many of the shorts replay tendencies that are characteristic of art cinema generally (1).

1. Cinema invokes eroticism . . . We get a dreamy Wong Kar-wai scene of a man watching, or recalling, heavy petting in the theatre. Polanski’s episode plays amusingly on the similarity of orgasmic moans and painful groans. Gus van Sant’s First Kiss reinvents Sherlock Jr., while the Dardenne brothers give us a tight tale of hands in the dark. Olivier Assayas’ episode, a crisp piece of filmmaking, reveals its l’amour fou at the very end. Angelopoulos makes clever use of the Kuleshov effect to create a touching exchange between Jeanne Moreau and the lamented Mastroianni.

2. . . . and childhood, especially for the Chinese directors, who haven’t exactly risen to the occasion here. The international art film has long traded on the appeal of kids, but the treatment of them in these episodes is remarkably banal. Tsai Ming-liang, who already passed his benediction for classic cinema in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, gives us a dream of a family reunited at the pictures. Chen Kaige shows children watching—hold on now—a silent Chaplin film. Hou Hsiao-hsien provides a sepia-toned flashback to going to the movies in Taiwan, while Zhang Yimou takes us to movie night in a Mainland village. At least the Hou episode opens on a lengthy shot that nicely decenters areas of interest in a busy street scene.

3. The cinema is on the decline . . . . One way to interpret Kitano Takeshi’s cryptic sequence is that films, even his own Kids’ Return, are little more than an anachronism today. More explicitly, David Cronenberg’s single-take close-up, captured by a surveillance camera shows himself as the world’s last surviving Jew, on the threshold of suicide in a movie house.

4. . . . yet it holds us in a magical spell. Some directors celebrate the simple folk at the movies. Claude Lelouch’s parents watch Top Hat and fall in love. Raymond Depardon takes us to a rooftop cinema in Alexandria, and Wenders shows a Congolese village running Black Hawk Down on video (more kids, but this time to disturb us). Kaurismaki seems to be poking fun at this arthouse commonplace by showing foundry workers blankly watching a rather different image of workers at the end of the day. The cinema, Ruiz and González Iñárritu suggest, mesmerizes even blind people.

Walter Salles provides a charming, deflating musical dialogue (below) that might be called Far from Cannes, showing that this festival casts a quasi-religious spell felt across the world. In my favorite section, Kiarostami gives us shots of women responding to Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. The image/sound pairing hints at their own thwarted loves, while certain lines, such as “Where be these enemies?,” seem addressed to Westerners who try to dehumanize the people of Iran.

5. Film can be silly. Von Trier, decked out in a tux, silences a businessman through extreme means, and the rest of the audience hardly notices. Jane Campion, in an awkward episode, reveals a bug living in a theatre speaker. Probably the funniest contribution shows a mute Elia Suleiman preparing for a Q & A session after a screening. There are more gags in this three minutes than in all the other episodes put together.

5. Lest we forget . . . This couldn’t help but be a nostalgia exercise, encouraging filmmakers to muse on their lives in cinema. This theme recalls Cinema Paradiso, Scola’s Splendor, and all the other films soaked in the melancholy sweetness of movie memories. Moretti (top image above), gives us an anecdotal monologue, while Youssef Chahine unashamedly thanks Cannes for giving him an award ten years ago. The most formally ingenious entry here is Atom Egoyan’s tale of a couple sitting in different screenings while texting each other. Eventually one grabs an image from La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and passes it along, creating a parallel to what’s happening in the other film (Egoyan’s The Adjuster).

In particular, there’s nostalgia for the golden age of auteurs, the very period when the anthology film gained its purchase. Chacun son cinéma is dedicated to Fellini, and Konchalovsky’s episode centers on 8 ½. Bresson and Godard are the most frequently referenced directors. (More generally, in our new century Bresson seems to have become the prototype of the serious filmmaker.) Other icons of the 1960s, such as Mastroianni and Anna Karina, keep popping up.

6. Spot the auteur. Most episodes don’t reveal the director’s name until the end, so the cinephilia takes on a suspenseful dimension, forcing you to guess who filmed the bit you’re watching. You also have to identify movies within the movies on the basis of clips and soundtracks. It’s a great game for arthouse aficionados, but it also highlights festival cinema’s reliance on the cult of the director and the organic unity of his/her body of work.

Suppose that all these films omitted the director’s name and replaced the recognizable players with nobodies. Would any of these episodes have been accepted for Cannes’ short film programs? Probably not, but we shouldn’t be cynical about this. Clearly artworks can gain in interest by virtue of their place in history or an artist’s career. Renoir’s Sur un air de Charleston (1927), Bresson’s Les affaires publiques (1934), Dreyer’s They Caught the Ferry (1948), and Fassinder’s episode in Germany in Autumn are not masterpieces, but these shorts show fresh sides of great filmmakers, and our understanding of their accomplishment is enriched by having them.

So we’re right to recognize the director’s career as a meaningful whole. But we should also recognize that today such careers continue thanks to a distinct system of marketing. At the Cannes site, Rauol Ruiz says: “It’s a delight to be a preferred filmmaker and especially a favored filmmaker of Gilles Jacob.” The system depends on reciprocity. “Without the auteurs,” says Jacob, “there wouldn’t be a festival.” (2) In turn, auteurs are obligated to festival gatekeepers and tastemakers, the powerful critics, programmers, and impresarios. The filmmaker knows the drill. You showed my film last year, so yes, I’ll sit on a jury or offer a master class or show up on the red carpet this year.

We’re told by Anne Thompson that a more complete DVD edition, including the David Lynch entry, will be available before Christmas. That gesture makes the disc I bought the equivalent of the plain-vanilla DVD of a blockbuster that will be followed at the right moment by the Deluxe Edition. Who says the art cinema operates above pressures of business and the market?

(1) I discuss the idea of art cinema in a 1979 article, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” revised in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(2) Nancy Tartaglione-Vialatte, “‘Without the auteurs there wouldn’t be a festival,'” Screen International (May 18-31, 2007), p. 15. See also the accompanying article by Nick Roddick, “The bucks start here,” pp. 14-15. These are available online to subscribers.

PS: Speaking of Cannes and the art cinema, I wrote an essay about camerawork in contemporary Danish film for the festival issue of the Danish Film Institute magazine. It’s now online here (pp 22-26). And speaking of Danish filmmakers. . . .

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill.

Movies on the radio

DB here:

There’s no shortage of podcast film reviews, but I confess that I’ve listened to only a few. I’m just not that interested in following a movie review at the pace of a speaking voice; I prefer skimming print to pluck out the good parts. And I’m on the lookout for ideas and information, not only opinions. I want to learn new stuff. So my iPod favors shows that center on interviews with directors, writers, and moguls. The two programs that I like best are produced by the extraordinary KCRW in Santa Monica and are also available from iTunes.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

A recent installment focused on the latest cycle of teenage horror, with input from Eli Roth, director of the Hostel films, and Oren Koules, producer of the Saw series. They talk about marketing directly to the fan sites and avoiding the expensive TV ads that studios bombard the public with. Putting banners and flashing ads on the horror sites, Roth says, attracts the same eyeballs as an ad on Lost, but for a fraction of the price. Koules:

Playing [an ad] on a Friends rerun doesn’t help anyone.

Likewise for budgets overall. Roth:

The scare is the star. . . .Nobody wants to see a $50 million version of Saw II. . . . People aren’t paying for big special effects. They’re paying to be scared.

In one of the most interesting stretches of the interview, Roth and Koules explain how they negotiate with the MPAA ratings board. According to the filmmakers, the board completely understands what they want to give the audience and the board is willing to cooperate. Koules:

We’re very respectful of the process. . . . And they know that we kind of know the market.

The fact that the films are designed for an R rating makes the task easier, of course, but sexual violence remains the most sensitive area. Roth:

They’re reflecting what the parents of America are going to say. . . . Just look at the culture. We have violence on television, people watch it—no problem. The stuff that I did in Hostel 1 is now on 24. [But] Janet Jackson shows her nipple and Congress is in session meeting about it and there’re all sorts of fines. So [the raters] really are just reflecting the temperature of the culture.

More proof that the MPAA and the ratings board find it easier to accept the excesses of genre filmmaking than to support the naughty indie material Kirby Dick surveys in This Film Is Not Yet Rated. Why should bathing in blood rate an R while boinking, boffing, and the Wild Mambo get threatened with an NC-17?

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

He asks Robert Rodriguez, for instance, how music shapes a film’s editing rhythms. After acknowledging that he plays music for actors on the set (as Wong Kar-wai does), Rodriguez adds:

I’ll be doing music all the way through the process of making a movie. And then I’ll usually just start editing first. Then I’ll put the edit into my music system, write the music for it, and if I like how the music is driving the scene and if the edits don’t match, I’ll go and adjust the edits. So I tell other composers—they’re probably very jealous—that I’m the composer who can tell the editor to go back and make the picture fit the music.

Another example: A while back, I posted a blog entry on how framing and the choice of lenses can create comic effects. I illustrated with an instance from Shaun of the Dead. Serendipitously, last week I discovered Mitchell’s recent interview with Shaun‘s director Edgar Wright, who acknowledged that the idea was central to his filmmaking.

The thing I’ve been trying to do in Spaced and Shaun and Hot Fuzz is the camera almost becomes a personality. Not only is the script funny and the performances are funny, but the compositions are funny—the framing of the shots is funny. . . . I remember seeing Raising Arizona and thinking, “Oh, why isn’t all comedy shot like this? It’s amazing.” . . . You get the actors to think of the camera as another performer that they’re blocking with.

The entire conversation seems to me mandatory for students of film. Coaxed by Mitchell, Wright supplies specifics about planning a shoot, varying camera setups, and the “epileptic” style of the contemporary action films that Hot Fuzz is satirizing. Wright even seems to like Domino, which shows that he can see virtues in extravagance.

So I recommend both The Business and The Treatment to anyone who wants to get filmmakers’ thoughts about current trends in movie tradecraft.