Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Can you spot all the auteurs in this picture?

DB here:

Some movies consist of several distinct episodes, each directed by a different filmmaker and all focused on a single theme. I’ve heard them called anthology films, omnibus films, and portmanteau films.

The earliest one I know is If I Had a Million (1932); later, Hollywood offered us Ziegfeld Follies (1946) and O. Henry’s Full House (1952). The Brits gave us the horror anthology Dead of Night (1945). Still, I think we associate the form chiefly with European cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. We got Love in the City (1953), Amori di mezzo secolo (1954), The Seven Deadly Sins (1962), RoGoPaG (1963), Les plus belles escroqueries du monde (1964), Paris vu par . . . (1965), Three Faces of Woman (1965), The World’s Oldest Trade (1967), and Amore e rabbia (1969).

Why the emergence of omnibus movies at this point in history? Some causes are surely financial. Most high-budget European films of the period had to be cross-national coproductions. Bringing in directors from several different countries could help guarantee funding under EU auspices and participating nations’ subsidy schemes. Just as important, the anthology format appeared when the festival scene was starting to become a vast clearing house for international film trade.

Although you can argue that many people seeing If I Had a Million would recognize the Lubitsch episode, Hollywood’s use of the form didn’t stress directorial differences. But as the Euro auteur was becoming a marketable commodity in the postwar era, a collection of short films could sell if they were signed by big-name filmmakers. “Paris As Seen by…” signals the importance of the different directorial approaches, and the very title of RoGoPaG invokes Rossellini, Godard, and Pasolini as brand-name labels. (Granted, the final G, Hugo Gregoretti, didn’t add much to the deal.)

For full enjoyment, the 1960s portmanteau film requires a degree of specialized film knowledge. At one level, we enjoy varied treatments of a theme, but at another we’re supposed to recognize each director’s personal vision, as we know it from other films. Even political-commentary portmanteau films like Far from Vietnam (1967), Lucía (1968), and Germany in Autumn (1978) gathered international attention because of the name recognition of the filmmakers who participated. The same branding operates in New York Stories (1989) and, more openly, in the documentary 12 registri per 12 città (“12 Directors for 12 Cities,” 1989).

The format has returned recently. We’ve had 11’09”01—Sept. 11 (2002), Eros (2004), Tickets (2005), and Paris, je t’aime (2006), the last virtually a rebooting of Paris vu par . . . . As we’d expect, such films continue to highlight the personal signatures of festival familiars. But we can spot some new twists too.

For one thing, the unifying idea may be formal as well as thematic. The episodes of 11’09”01 were all obliged to be the same length, eleven minutes, nine seconds, and one frame. Lumière et cie (1995) not only celebrated the centenary of film but obliged the directors to make their entries with a Lumière camera, to shoot without sync sound, to shoot no more than three takes, and to restrict the length to 52 seconds, the approximate running time of the earliest films. The Lumière homage also introduces the key themes of cinema and cinephilia, an angle that doesn’t seem prominent in the 1960s omnibus movies.

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

A half-dozen things strike me while watching the French DVD version (which has English subtitles but is unaccountably lacking the Coens’ entry). Most notable, I suppose, is the way that many of the shorts replay tendencies that are characteristic of art cinema generally (1).

1. Cinema invokes eroticism . . . We get a dreamy Wong Kar-wai scene of a man watching, or recalling, heavy petting in the theatre. Polanski’s episode plays amusingly on the similarity of orgasmic moans and painful groans. Gus van Sant’s First Kiss reinvents Sherlock Jr., while the Dardenne brothers give us a tight tale of hands in the dark. Olivier Assayas’ episode, a crisp piece of filmmaking, reveals its l’amour fou at the very end. Angelopoulos makes clever use of the Kuleshov effect to create a touching exchange between Jeanne Moreau and the lamented Mastroianni.

2. . . . and childhood, especially for the Chinese directors, who haven’t exactly risen to the occasion here. The international art film has long traded on the appeal of kids, but the treatment of them in these episodes is remarkably banal. Tsai Ming-liang, who already passed his benediction for classic cinema in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, gives us a dream of a family reunited at the pictures. Chen Kaige shows children watching—hold on now—a silent Chaplin film. Hou Hsiao-hsien provides a sepia-toned flashback to going to the movies in Taiwan, while Zhang Yimou takes us to movie night in a Mainland village. At least the Hou episode opens on a lengthy shot that nicely decenters areas of interest in a busy street scene.

3. The cinema is on the decline . . . . One way to interpret Kitano Takeshi’s cryptic sequence is that films, even his own Kids’ Return, are little more than an anachronism today. More explicitly, David Cronenberg’s single-take close-up, captured by a surveillance camera shows himself as the world’s last surviving Jew, on the threshold of suicide in a movie house.

4. . . . yet it holds us in a magical spell. Some directors celebrate the simple folk at the movies. Claude Lelouch’s parents watch Top Hat and fall in love. Raymond Depardon takes us to a rooftop cinema in Alexandria, and Wenders shows a Congolese village running Black Hawk Down on video (more kids, but this time to disturb us). Kaurismaki seems to be poking fun at this arthouse commonplace by showing foundry workers blankly watching a rather different image of workers at the end of the day. The cinema, Ruiz and González Iñárritu suggest, mesmerizes even blind people.

Walter Salles provides a charming, deflating musical dialogue (below) that might be called Far from Cannes, showing that this festival casts a quasi-religious spell felt across the world. In my favorite section, Kiarostami gives us shots of women responding to Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. The image/sound pairing hints at their own thwarted loves, while certain lines, such as “Where be these enemies?,” seem addressed to Westerners who try to dehumanize the people of Iran.

5. Film can be silly. Von Trier, decked out in a tux, silences a businessman through extreme means, and the rest of the audience hardly notices. Jane Campion, in an awkward episode, reveals a bug living in a theatre speaker. Probably the funniest contribution shows a mute Elia Suleiman preparing for a Q & A session after a screening. There are more gags in this three minutes than in all the other episodes put together.

5. Lest we forget . . . This couldn’t help but be a nostalgia exercise, encouraging filmmakers to muse on their lives in cinema. This theme recalls Cinema Paradiso, Scola’s Splendor, and all the other films soaked in the melancholy sweetness of movie memories. Moretti (top image above), gives us an anecdotal monologue, while Youssef Chahine unashamedly thanks Cannes for giving him an award ten years ago. The most formally ingenious entry here is Atom Egoyan’s tale of a couple sitting in different screenings while texting each other. Eventually one grabs an image from La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and passes it along, creating a parallel to what’s happening in the other film (Egoyan’s The Adjuster).

In particular, there’s nostalgia for the golden age of auteurs, the very period when the anthology film gained its purchase. Chacun son cinéma is dedicated to Fellini, and Konchalovsky’s episode centers on 8 ½. Bresson and Godard are the most frequently referenced directors. (More generally, in our new century Bresson seems to have become the prototype of the serious filmmaker.) Other icons of the 1960s, such as Mastroianni and Anna Karina, keep popping up.

6. Spot the auteur. Most episodes don’t reveal the director’s name until the end, so the cinephilia takes on a suspenseful dimension, forcing you to guess who filmed the bit you’re watching. You also have to identify movies within the movies on the basis of clips and soundtracks. It’s a great game for arthouse aficionados, but it also highlights festival cinema’s reliance on the cult of the director and the organic unity of his/her body of work.

Suppose that all these films omitted the director’s name and replaced the recognizable players with nobodies. Would any of these episodes have been accepted for Cannes’ short film programs? Probably not, but we shouldn’t be cynical about this. Clearly artworks can gain in interest by virtue of their place in history or an artist’s career. Renoir’s Sur un air de Charleston (1927), Bresson’s Les affaires publiques (1934), Dreyer’s They Caught the Ferry (1948), and Fassinder’s episode in Germany in Autumn are not masterpieces, but these shorts show fresh sides of great filmmakers, and our understanding of their accomplishment is enriched by having them.

So we’re right to recognize the director’s career as a meaningful whole. But we should also recognize that today such careers continue thanks to a distinct system of marketing. At the Cannes site, Rauol Ruiz says: “It’s a delight to be a preferred filmmaker and especially a favored filmmaker of Gilles Jacob.” The system depends on reciprocity. “Without the auteurs,” says Jacob, “there wouldn’t be a festival.” (2) In turn, auteurs are obligated to festival gatekeepers and tastemakers, the powerful critics, programmers, and impresarios. The filmmaker knows the drill. You showed my film last year, so yes, I’ll sit on a jury or offer a master class or show up on the red carpet this year.

We’re told by Anne Thompson that a more complete DVD edition, including the David Lynch entry, will be available before Christmas. That gesture makes the disc I bought the equivalent of the plain-vanilla DVD of a blockbuster that will be followed at the right moment by the Deluxe Edition. Who says the art cinema operates above pressures of business and the market?

(1) I discuss the idea of art cinema in a 1979 article, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” revised in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(2) Nancy Tartaglione-Vialatte, “‘Without the auteurs there wouldn’t be a festival,'” Screen International (May 18-31, 2007), p. 15. See also the accompanying article by Nick Roddick, “The bucks start here,” pp. 14-15. These are available online to subscribers.

PS: Speaking of Cannes and the art cinema, I wrote an essay about camerawork in contemporary Danish film for the festival issue of the Danish Film Institute magazine. It’s now online here (pp 22-26). And speaking of Danish filmmakers. . . .

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill.

Movies on the radio

DB here:

There’s no shortage of podcast film reviews, but I confess that I’ve listened to only a few. I’m just not that interested in following a movie review at the pace of a speaking voice; I prefer skimming print to pluck out the good parts. And I’m on the lookout for ideas and information, not only opinions. I want to learn new stuff. So my iPod favors shows that center on interviews with directors, writers, and moguls. The two programs that I like best are produced by the extraordinary KCRW in Santa Monica and are also available from iTunes.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

A recent installment focused on the latest cycle of teenage horror, with input from Eli Roth, director of the Hostel films, and Oren Koules, producer of the Saw series. They talk about marketing directly to the fan sites and avoiding the expensive TV ads that studios bombard the public with. Putting banners and flashing ads on the horror sites, Roth says, attracts the same eyeballs as an ad on Lost, but for a fraction of the price. Koules:

Playing [an ad] on a Friends rerun doesn’t help anyone.

Likewise for budgets overall. Roth:

The scare is the star. . . .Nobody wants to see a $50 million version of Saw II. . . . People aren’t paying for big special effects. They’re paying to be scared.

In one of the most interesting stretches of the interview, Roth and Koules explain how they negotiate with the MPAA ratings board. According to the filmmakers, the board completely understands what they want to give the audience and the board is willing to cooperate. Koules:

We’re very respectful of the process. . . . And they know that we kind of know the market.

The fact that the films are designed for an R rating makes the task easier, of course, but sexual violence remains the most sensitive area. Roth:

They’re reflecting what the parents of America are going to say. . . . Just look at the culture. We have violence on television, people watch it—no problem. The stuff that I did in Hostel 1 is now on 24. [But] Janet Jackson shows her nipple and Congress is in session meeting about it and there’re all sorts of fines. So [the raters] really are just reflecting the temperature of the culture.

More proof that the MPAA and the ratings board find it easier to accept the excesses of genre filmmaking than to support the naughty indie material Kirby Dick surveys in This Film Is Not Yet Rated. Why should bathing in blood rate an R while boinking, boffing, and the Wild Mambo get threatened with an NC-17?

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

He asks Robert Rodriguez, for instance, how music shapes a film’s editing rhythms. After acknowledging that he plays music for actors on the set (as Wong Kar-wai does), Rodriguez adds:

I’ll be doing music all the way through the process of making a movie. And then I’ll usually just start editing first. Then I’ll put the edit into my music system, write the music for it, and if I like how the music is driving the scene and if the edits don’t match, I’ll go and adjust the edits. So I tell other composers—they’re probably very jealous—that I’m the composer who can tell the editor to go back and make the picture fit the music.

Another example: A while back, I posted a blog entry on how framing and the choice of lenses can create comic effects. I illustrated with an instance from Shaun of the Dead. Serendipitously, last week I discovered Mitchell’s recent interview with Shaun‘s director Edgar Wright, who acknowledged that the idea was central to his filmmaking.

The thing I’ve been trying to do in Spaced and Shaun and Hot Fuzz is the camera almost becomes a personality. Not only is the script funny and the performances are funny, but the compositions are funny—the framing of the shots is funny. . . . I remember seeing Raising Arizona and thinking, “Oh, why isn’t all comedy shot like this? It’s amazing.” . . . You get the actors to think of the camera as another performer that they’re blocking with.

The entire conversation seems to me mandatory for students of film. Coaxed by Mitchell, Wright supplies specifics about planning a shoot, varying camera setups, and the “epileptic” style of the contemporary action films that Hot Fuzz is satirizing. Wright even seems to like Domino, which shows that he can see virtues in extravagance.

So I recommend both The Business and The Treatment to anyone who wants to get filmmakers’ thoughts about current trends in movie tradecraft.

Live with it! There’ll always be movie sequels. Good thing, too.

DB:

You’ve heard it before. Facing a summer packed with sequels, a journalist gets fed up. This time it’s Patrick Goldstein in the Los Angeles Times, and his lament strikes familiar chords. Sequels prove that Hollywood lacks imagination and is interested only in profits. Sequel films are boring and repetitious. They rarely match the original in quality. And when good directors sign on to do sequels, they get a big payday but they also compromise their talents.

Me, I want more original and plausible ideas. So, I expect, do you. Time to call in the Badger squad, the ensemble of email pals drawn from various generations of UW-Madison grad students and faculty. I asked them if we can’t understand sequels in a more thoughtful and sophisticated way—historically, artistically, in relation to other media. The result is another virtual roundtable, like the one on B-films held here a few months ago.

There were enough ideas for several blogs, and I’ve regretfully had to drop a whole thread devoted to comics and videogames. Maybe I’ll compile those remarks into a sequel. For now, the participants are: Stew Fyfe; Doug Gomery; Jason Mittell (of JustTV); Michael Newman (of Zigzigger and Fraktastic); Paul Ramaeker; and Jim Udden. I throw in some ideas as well.

Are all sequels in the arts automatically second-rate?

DB: The Odyssey is a sequel to the Iliad, and the second, better part of Don Quixote is a sequel to the first. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is explicitly a followup to The Hobbit. After killing off Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Final Problem,” Conan Doyle resurrected him for more exploits. The Merry Wives of Windsor brings back Sir John Falstaff after his death in Henry IV Part II, because, supposedly, Queen Elizabeth wanted to see him again, this time in a romance plot.

Michael Newman: Sequels exist in all narrative forms–novels, plays, movies, television, videogames, comics, operas. What is the Bible but a series of sequels? Didn’t Shakespeare follow up Henry IV with a part II? What of Wagner’s Ring Cycle and Updike’s Rabbit novels? Many novelists of high reputation have written sequels, including Thackeray, Trollope, Faulkner, and Roth. There is nothing intrinsically unimaginative about continuing a story from one text to another. Because narratives draw their basic materials from life, they can always go on, just as the world goes on. Endings are always, to an extent, arbitrary. Sequels exploit the affordance of narrative to continue.

What about film sequels? What’s their track record?

DB: Goldstein grants the excellence of Godfather II, but what about Aliens, The Empire Strikes Back, Toy Story 2, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (arguably the best entry in the franchise)? We have arthouse examples too, provided by Satyajit Ray (Aparajito and The World of Apu), Bergman (Saraband as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage), and Truffaut (the Antoine Doinel films). If we allow avant-garde sequels, we have James Benning‘s One-Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later. As for documentaries, what about Michael Moore’s Pets or Meat?, the pendant to Roger and Me?

The world of film would be a poorer place if critics had by fiat banned all the fine Hong Kong sequels, notably those spawned by Police Story, A Better Tomorrow, Drunken Master, Once Upon a Time in China, Swordsman, and so on up to Johnnie To’s Election 2 and Andrew Lau’s Infernal Affairs 2. And arthouse fave Wong Kar-wai hasn’t been shy about making sequels.

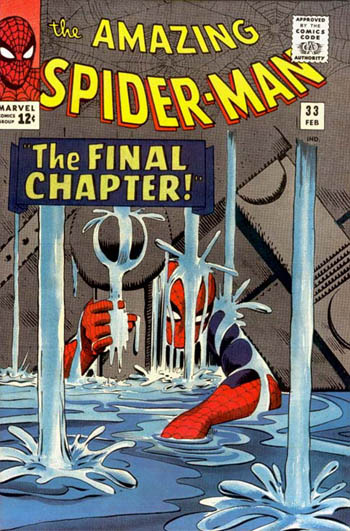

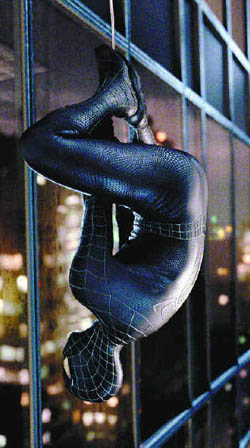

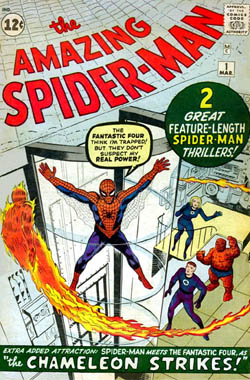

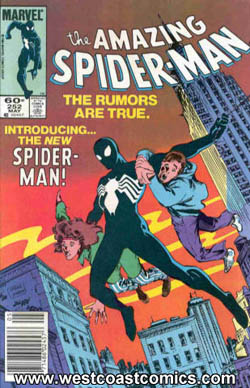

Stew Fyfe: Other sequels of quality: The Bride of Frankenstein, Mad Max II (The Road Warrior), Spider-Man 2, X-Men 2, Dawn of the Dead, Sanjuro, Quatermass and the Pit. Personally, I’d also add Blade 2, Babe 2 and The Devil’s Rejects, but I’m sure those are arguable. Would The Limey be a sequel to Poor Cow? Del Toro speaks of Pan’s Labyrinth as a companion piece or “sister-film” to The Devil’s Backbone. If you want to include docs, there’s always the Up series.

Why are there film sequels in the first place?

DB: Most film industries need to both standardize and differentiate their products. Audiences expect a new take on some familiar forms and materials. Sequels offer the possibility of recognizable repetition with controlled, sometimes intriguing, variation. This logic can be found in sequels in other media, which often respond to popular demand for the same again, but different. Remember Conan Doyle reluctantly bringing back Holmes, and Queen Elizabeth asking to see Sir John in love.

Doug Gomery: Sequels happen because the studio owners have never figured out any business model to predict success. If #1 is popular, perhaps #2 will be almost as popular. Until recently, producers seldom expected the followup’s revenues to equal the first. The basics were keep costs low, keep risks low, and make a profit. Maybe not a large as the breakthrough initial film—but at least a profit.

But they’re not a contemporary development. As part of the Hollywood studio system, they have existed in all eras—the Coming of Sound, the Classical Era, and the Lew Wasserman era. They surely seem to be surviving Wasserman as well. Indeed, as much as I admire Wasserman, who can defend Jaws 2 and its successors?

In the classic era, it may seem that there were fewer sequels as such, but there was a variant called rewrites in another genre. Years ago as I did my first book, a study of High Sierra, I watched Colorado Territory with something close to awe. It’s a gangster film turned western almost line by line. After all, Warners owned the literary rights: why not recycle it?

Given the mercenary impulse behind sequels, does a director’s willingness to make one mean that he or she has sold out?

Goldstein: “Look at the great talent who’s on the sequel beat: Steven Soderbergh has done two Ocean’s sequels. Bryan Singer, the wunderkind behind The Usual Suspects, has done X-Men 2 and is at work on a sequel to Superman Returns. Christopher Nolan has left behind the raw originality of Memento to do Batman movies. Robert Rodriguez, who burst on the scene with El Mariachi, has done two sequels for Spy Kids, with a Sin City sequel on its way. After making Darkman and A Simple Plan, Sam Raimi seemed poised to be our generation’s dark prince of meaty thrillers but has turned himself into an impersonal Spider-Man ringmaster instead.”

Paul Ramaeker: To assume that the Spider-Man films must necessarily be less personal than Darkman or A Simple Plan (both of which are heavily indebted to the strictures of their genres) is to perpetuate a culturally snobbish perspective on comic books. I’ve not seen S-M3, but Raimi is a genuine fan of the character, a character with a long and complex narrative history, and given the way S-M2 continues and develops threads from the first film, I see no reason to assume he didn’t have some artistic investment in presenting his interpretation of the character over 3 films (or however many) to present a larger “story” about the character. Why should this not be seen as “personal” filmmaking to the same extent as any other kind of adaptation?

Moreover, speaking as a Soderbergh fan: I may not like Ocean’s 12 as much as Ocean’s 11, but it seems like an experiment made in good faith to me. It is a stranger movie than you would think from the way it gets picked up in articles like Goldstein’s. In fact, the way it plays with audience expectations is both dependent upon familiarity with the first film, and radically divergent from it- in many ways, it does the exact opposite of what sequels are supposed to do, which is to provide a “cozy” (Goldstein’s word) repetition of familiar pleasures. Perhaps it failed (again, I remain sort of fond of the film, which I think was best described as being like an issue of Us Weekly as put together by the editors of Cahiers du cinéma), but even so I think you’d have to call it a failed experiment rather than a rehashing.

Stew Fyfe: At a guess, I’d say that audiences or critics might evaluate the worthiness/mercenary nature of sequels by asking three questions:

(1) Has the sequel been made because there’s more story to tell?

(2) Has the sequel been made because the characters are great and people want to see them again?

(3) Has the sequel been made because there’s more money to be made?

Obviously, any combination of all three can be answered in the affirmative for any sequel and presumably the sequel wouldn’t get made if the answer to (3) was No. But with something like The Two Towers, (1) gets priority, while with Pirates 2 + 3, (3) nudges out (2). Even with (3), money, as the primary motivation, one could still make a good film. The suspicion of milking the franchise just makes the movie an easier target for critics.

Do sequels automatically equal predictability?

Jason Mittell: The line that most interests me in Goldstein’s piece is the last: “When it comes to entertainment, I’ll take excitement and unpredictability over familiarity every time.” This sets up a false dichotomy between the known and the unknown. As David and I both blogged about a few months ago, knowing a story doesn’t preclude suspense and excitement (and for some viewers, it might actually enhance it). And arguably knowing a storyworld actually allows for greater opportunities for excitement and unpredictability – a film/episode/entry in any series that doesn’t need to spend much time introducing already-established settings, characters, conflicts, etc. can literally cut to the chase. Think of the second Bourne film as a good example, or Spider-man 2 as a chance to deepen character once basic exposition is accounted for.

Paul Ramaeker: I have a theory. In the contemporary comic-book blockbuster, the sequels will always be better than the first entries. Spider-Man 2 is better than Spider-Man, X-Men 2 is better than X-Men, and I will bet that The Dark Knight will be better than Batman Begins, just as Batman Returns was better than Batman. The pattern seems to me to be that the first film in the series is relatively impersonal—the franchise must be established as a franchise, meaning that few boats will be rocked, and the director must prove that they can handle both a film on that scale, and can be trusted with the property with all the investment it represents.

But once they’ve done so, in the above cases where the first films enjoyed significant economic (and critical) success, the directors are given a bit more leeway, are allowed to drive the family car a little further and a little faster. In each case, the second film in the series by the same director has been significantly more idiosyncratic. Batman Returns has much more of Burton‘s sense of humor and interest in the grotesque; X-Men 2 is a much more serious and ambitious film narratively and thematically, more obviously the product of a prestige filmmaker (Singer’s never been an auteur by any stretch, so that will have to do). Spider-Man seemed sort of anonymous in terms of style, but Spider-Man 2 had a much more extensive and playful use of classic Raimi techniques: short, fast zooms; canted angles; rapid camera movements; whimsical motivations for techniques, like the mechanical-tentacle POV shot (virtually a repeat of his flying-eyeball POV from Evil Dead 2).

Who knows what The Dark Knight will be like, but I’m prepared to put money on the claim that it will have something to do with how people construct elaborate narratives around themselves to explain, justify, or obscure their actions and motives.

Are sequels part of a larger trend toward serial narrative?

DB: We can continue a story in another text within the same medium, but we can also spread the storyline across many platforms—novels, films, comic books, videogames. Henry Jenkins has called this process transmedia storytelling.

Michael Newman: Compared with literary fiction, there seems to be a strong propensity toward the never-ending story in genre storytelling like sci-fi and fantasy and superhero comics and spy novels and soap operas. Much of the cinematic sequel storytelling today might be considered as this kind of serialized genre storytelling. Such serials tend to have a low aesthetic reputation in comparison to more respectable genres. (The cinematic comparison would be summer blockbusters vs. fall Oscar bait.) Serial forms have historically been associated with children (e.g., comic books) and women (e.g., soaps). In other words, there is cultural distinction, a system of social hierarchy, at play.

Stew Fyfe: Yes, the longer-standing comics universes have made regular use of serial continuity to forge after-the-fact connections. It’s a form of what fans call retcon or “retroactive continuity.”

Sci-fi writer Phillip Jose Farmer used a similar concept, the “Wold Newton family” to link various mystery, pulp, crime, sci fi, adventure and spy fiction characters (so that Sherlock Holmes, Doc Savage, Sam Spade, The Shadow, Captain Blood and James Bond, among others, all become linked). Alan Moore did something similar with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and Warren Ellis in Planetary. More limited filmic examples of this might be Zatoichi vs. Yojimbo, or Enemy of the State (which more or less sticks The Conversation‘s Harry Caul into a Bruckheimer film). There’s Freddy vs. Jason, which very adroitly observes and incorporates the continuities of two long-standing, mostly dormant franchises. In television, there’s that whole, rather insane St. Elsewhere continuity thing.

In the current crop of movie sequels featuring superheroes, one thing that has been noticeable is the casting of minor characters who might serve as springboards for later storylines. We’ve seen Dylan Baker play Dr. Connors in two Spidey films, for example, so if they decide to go with The Lizard as a villain in one of the later films, they’ve already set him within the film series’ continuity. Aaron Eckhart’s casting as Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight could similarly be used to set up Two Face as a villain for film 3.

This is similar to the idea of leaving a film “open for a sequel,” but it seems more closely integrated into the planning and execution of the film. It also points to a middle ground between the “We’re going into this making three unified films” model (Lord of the Rings) and the “We can make more money, so let’s see what plot elements we can build off of” (Pirates of the Caribbean). This is more of a “We’re probably going to make more films, let’s give ourselves something to work with” model.

It also raises the question, I guess, if you want to start speaking of dangling causes extending past the end of a film, or in the case of Pirates, the conversion of plot elements into something like dangling causes. In Pirates 1, we hear of Bootstrap Bill Turner getting chained to a cannonball and shot out into the ocean, but wasn’t it after he was made immortal by the curse of the Aztec gold? I guess you could call this a retroactive cause. Or, noting the similarity to “retcon,” a “retcause.” Never mind, that sounds lame.

Michael Newman: In the contemporary era of media convergence, serialized storytelling is becoming a mainstay across media and genres. Serial narratives supposedly facilitate spreading franchises out across multiple platforms. The media franchise demands long-format storytelling that can be spun off in multiple iterations. The rise of sequels is a much larger issue than a bunch of directors trying to make lots of money or audiences having unadventurous tastes–sequel/serial franchises are a central business model in the media industry today, supported and encouraged by the structure of conglomeration and horizontal integration.

The real point of the LAT article is that Hollywood is all commerce and no art, and sequels are a symptom. But this is such old news. And to connect it to a Squeeze summer tour is really stretching.

Jason Mittell: I think Michael’s cross-media point is crucial – continuity of a narrative world is a core part of nearly every storytelling form, but the language of “sequel” is applied predominantly to film. “Series” seems a more respectable term, as it suggests an organic continuity rather than a reactive stance of “Hey, let’s do that again!”

Are some serial/ sequel forms better suited to different media?

Jason Mittell: I think the LAT article is ultimately trying to valorize cinema’s potential to introduce something new, in reaction to the presumed rise of legitimate and praised series narratives on television (The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, Lost, etc.). And perhaps he has a point. Maybe film should stick to presenting compelling stand-alone short stories, since television has emerged as the leader in narrating persistent worlds? Or maybe I’m just saying that to pick a fight…

Jim Udden: I disagree that films should stick with one-off feature-length productions and leave ongoing series work to TV. Television has long had its Made for TV Movies, so why shouldn’t cinema think more in terms of series than it does? After all, if these are truly hard times for the film industry, as we’re always told, doesn’t it make more economic sense to adapt, just as TV has done in the last couple of decades?

True, there are things that cannot be matched on either side. I cannot imagine any film ever matching the daunting complexity of Deadwood or The Wire. Then again, some things work best as a stand-alone concern. Try to imagine a sequel to Pan’s Labyrinth or Children of Men, or try to imagine either film being made only for TV, for that matter. Moreover, some sequels should never be made. (Remember 2010?) On the other hand, some films would have been better off had they been pitched as an HBO series. (Syriana comes to mind.)

Yet film has proven its ability to take on a series format even when it is not called that. In a sense the oeuvres of most of the great art cinema auteurs are series of sorts. Aren’t Tati’s films a series with the ongoing presence of Hulot (or Hulots, if we include the false ones in Play Time)? And does anybody castigate Wong Kar-wai for following up Chungking Express with Fallen Angels, or In the Mood for Love with 2046, which are not series, but mere (gasp!) sequels? Clearly these examples were based not just on aesthetic visions, but on banking on previous success. Why do we give them a pass, but not more mainstream fare?

I think the more closely we look, the more we might find there are series and sequels even if they are not tagged by those names. It does happen in documentary, and not just in the 7 Up series. For example, American Dream does seem to me to a continuation of Harlan County USA, if not an outright sequel. Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11 combined make for a more complex argument about the relation of the defense industry to class issues than each one does on its own.

In other words, none of these formats has any value on its own. Everything depends on the type of stories to be told and the talent and economic wherewithal to find the best format for that story (or argument). The most appropriate format could be just a two-hour film, or it could be a television series going on for years. Or it could be something in between, such as the first two Infernal Affairs films, which got clumsily condensed into one film in The Departed. Both television and film can equally participate in such in-between formats.

DB: I don’t agree with all of these arguments and opinions, and I don’t expect you to either. The point is that compared to journalists’ rote dismissal of sequels, these writers offer more stimulating and more probing arguments. These guys are researchers and teachers, and they offer detailed evidence for their claim. They also write clearly, a point to remember when people say that film academics always talk in jargon and pontificate about gaseous theories.

To end on an upbeat note, I note that some journalists avoid the conventional wisdom. Consider Manohla Dargis’ recent and welcome defense of the blockbuster. Her case doesn’t seem to me spanking new: the artistic possibilities of the format have been defended for several years by film historians, as well in Tom Shone’s lively 2004 book Blockbuster. (1) Still, in the pages of the good, gray Times, Dargis’s piece remains something of a breakthrough. Maybe some day the paper will host a defense of sequels as well. If so, consider this communal blog a prequel.

(1) A sample, with Shone responding to the charge that the ’70s blockbuster drove out ambitious American filmmaking: “Any revolution that left it difficult for Robert Redford to make a movie as self-importantly glum as Ordinary People can be no bad thing” (Blockbuster, 312).

PS 30 June: Jason Mittell continues the conversation by contesting another journo’s claim that the public is tiring of sequels this summer.

Sundancing in Mad City

![]()

DB here:

Though we’re in Auckland and missed the opening of Sundance 608 in Madison, we’re happy to read about it. The company played the local press like a violin, slowly building the news and letting local bigwigs get the VIP tour before opening. Redford hinted that he’d show up, then had to stay home to finish cutting Lions for Lambs.

The Capital Times gave robust coverage to the opening night (screening of Paris, je t’aime) and the benefit followup (La vie en rose). Rob Thomas analyzes the impact on local film culture here, with comments from Lionsgate and other distributors. In Dean Robbins’ Isthmus interview, Redford suggests that Madison was selected because of its progressive politics rather than its movie mania (which I blogged about last year). He also intimates that the new chain may be showing films that didn’t make the cut for his festival. Does this make Sundance a film distributor as well as an exhibitor?

Put aside the amenities–cafe, bar, rooftop restaurant, padded armchairs, free WiFi in the lounges. This is about movies, remember? The first week’s lineup is strong: Waitress, Black Book, Air Guitar Nation, The TV Set, Away from Her, and After the Wedding. If the city’s other art theatres, Westgate and the Orpheum/Stage Door can stay competitive, Madison will have twelve screens devoted to indie and foreign-language fare–pretty good for a city of a couple hundred thousand people.

PS 14 May (New Zealand time): In the blog, Dane101, Sean Weitner provides a vivid and detailed account of going to Sundance 608, including the “convenience fee,” which I’ve never encountered but which makes great sense. One more reason to get homesick for Mad City.

PPS 16 May (NZT): Go here for Ann Althouse’s skeptical take on Sundance 608, including pix. Thanks to Michael Newman for the link.

PPPS 20 May (NZT): Go to this story in The Capital Times and this forum to find out how confusing the “convenience fee” can be, and why it may alienate customers. I hadn’t realized that it doesn’t add that much convenience, becomes obligatory at prime times, and operates even when the theatre is nearly empty.