Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Dispatch from the Land of the Long White Cloud

Kristin here—

David and I are currently in New Zealand. The University of Auckland offered us both Hood Fellowships, and we will be in residence here for the month of May.

After settling into a hotel room with a splendid view of part of the Auckland harbor and downtown, we were shown around the campus by our host, Brian Boyd, Nabokov scholar extraordinaire. We’ll be giving lectures in classes and to the public over the next week and a half. I’ll also be doing some media interviews relating to The Frodo Franchise, which is due to be published here by Penguin New Zealand, probably in early September. Today, in fact, I met my editors and publicity person at Penguin.

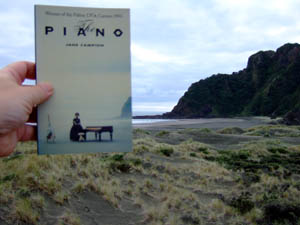

Yesterday Brian and his wife Bronwen Nicholson drove us out to the Waitakere Ranges Regional Park, a large area on the coast west of Auckland. The park is spectacularly beautiful in itself, but our goal was Karekare Beach, one of several black-sand beaches within the park. It was the location where the beach scenes of Jane Campion’s The Piano were shot and even now remains a popular tourist destination. There we are (above), more or less at the spot where Holly Hunter’s character brought her piano ashore in her new home.

Naturally we have also done some book and DVD shopping. When I first came to New Zealand to work on The Frodo Franchise, back in September and October of 2003, there were almost no Kiwi films on DVD: Once Were Warriors, of course, and Whale Rider, the two most popular New Zealand features, and a few others.

As I discuss in the book (Chapter 10), The Lord of the Rings had a beneficial impact on New Zealand cinema. In large part because of the trilogy, filmmakers gained new skills, new production infrastructure was created, local directors and other talent returned from jobs abroad, and government funding increased. Kiwi films became more popular within their own country. When I talked to Dr. Ruth Harley, CEO of the New Zealand Film Commission, in late 2005, she declared that the national cinema was perhaps having its best year ever, and the momentum does not seem to have slowed.

One sign of success is that one can now find some of the older classics on DVD. There’s actually a “Roger Donaldson Collection” series. (That’s the same Roger Donaldson who is more famous in U.S. for The Bounty, Dante’s Peak, and Cocktail.) We picked up his Sleeping Dogs (1977), notable as the first New Zealand film to play in American theaters, and Smash Palace (1981), the movie that led to his career abroad. A DVD set from this series containing both films is available in the U.S.

I saw Donaldson’s latest, The World’s Fastest Indian (2005) at the American Film Market in 2005—the same occasion upon which I interviewed Dr. Harley for the second time for my book. I opined to her that the film might well be a considerable success in the US. It’s an engaging and entertaining film with Anthony Hopkins giving a marvelous performance in the true story of an eccentric Kiwi who tinkered with an old motorcycle (the “Indian” of the title) and set a world speed record with it.

Unfortunately The World’s Fastest Indian was released without much publicity and didn’t do much business in the US. It’s well worth seeking out on DVD.

There are other signs of increased interest in local films. Geoff Murphy’s hit film Goodbye Pork Pie (1981), previously available on a PAL DVD without region coding, has come out in a “Special Collector’s Edition” with a new transfer, a stereo soundtrack not included on the original release prints, and a second disc of extras. Three years ago I would not have predicted that an older Kiwi film would get such treatment. Murphy is better known in the art-cinema world for his later Utu (1983) and The Quiet Earth (1985).

Similarly, May 6 saw the inauguration of a series of eight older Kiwi films to be shown weekly on Sunday nights until June 24 on Māori Television, one of the national channels in New Zealand. Most of these are not specifically oriented toward Māori subject matter—perhaps further indication that a curiosity about Kiwi cinema in general has spread through the national culture. The opening film, The Last Tattoo (1994), was an engrossing political thriller set in 1943. I look forward to seeing as many of the others in the series as time permits.

Recent DVDs have also allowed me to catch up with two 2006 New Zealand films that I had not had a chance to see yet. Both received favorable reviews from Variety when they played at North American film festivals.

Sione’s Wedding is set among the Samoan community of Auckland. It follows four irresponsible young men as they try to fulfill a condition that will allow them to attend the wedding: they must all find “real” dates to bring along. No. 2 deals with an extended family struggling to organize a traditional Fijian feast on short notice when the matriarch declares that she will name her successor at the event.

Both are made with the sorts of technical resources that one would expect of an American indie film. New Zealand films still work with small budgets, but funding is distinctly larger than in the pre-Lord of the Rings era. Strikingly, both of these films deal with the familiar situation of a big family event where irresponsible men must be led to maturity by their women. Both are also highly enjoyable, especially No. 2, with its skillful blend of humor and sentiment and its powerful performance by Ruby Dee as the matriarch.

Sione’s Wedding, retitled Samoan Wedding for the North American release, received an enthusiastic review from Variety after its premiere at the Montreal World Film Festival late last summer. Magnolia released it on November 10, 2006, with a run of 14 weeks. It started in two theaters, with a respectable $7,852 average on its opening weekend. Eventually it played in only three theaters, made $72,244, and disappeared. It did, however, come out on DVD.

No. 2, also well-reviewed by Variety, is apparently to be released in the U.S. under the title Naming Number Two. For those living in or near New York, it will be shown on May 10 as part of the Pacifika Showcase series.

By a happy coincidence, next Saturday on TV2 at 5:30 pm, I’ll be able to watch the premiere of the children’s animated series Jane and the Dragon. Back in October 2003, when I interviewed Richard Taylor, head of Weta Workshop, he mentioned that he was trying to diversify the company’s projects so as to be able to offer steady work to his employees. One project was this series, for which he was then seeking financing.

Just over a year later, in early December 2004, I interviewed Richard again. By another coincidence, that was the day when Weta was beginning to test its new motion-capture studio that had been created to help in the production of Jane and the Dragon and other projects. Now at last the series is finished.

It’s already playing on Canadian TV, and the YTV.com site offers an entire episode for viewing here. The official website, aimed specifically at children, is here.

I hope to report back on it and other media-related experiences here in New Zealand, or Aoteroa, which means “The Land of the Long White Cloud.” It’s a well-deserved name. Anyone who thinks the mountains and other unspoiled landscapes shown in The Lord of the Rings and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe were created by CGI are mistaken. Much of New Zealand actually looks like that. I’m hoping to visit a few of the film locations that I haven’t seen on previous visits.

The view from our hotel balcony.

Swords vs. lightsabers

Solaris.

Kristin here–

On April 12, Jason Silverman posted a brief piece on Wired: “Writers, Directors Fear ‘Sci-Fi’ Label Like an Attack from Mars.” According to Silverman, film studios, book publishers, novelists, film directors, and other involved in the creative process often try to find alternative descriptions when publicizing their work. Thus Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road is “post-apocalytic” or “dystopian.” The executive producer of Battlestar Gallactica, Ronald D. Moore, is quoted: “It’s fleshed-out reality. It’s not in the science-fiction genre.” Never mind that it plays on the Sci-Fi Channel.

Such obfuscation is not universal. Plenty of works get labeled “science fiction.” Still, according to Silverman, the term sci-fi is dodged “especially when it applies to ‘serious’ fiction or cinema.”

There is something to this, though it needs to be qualified and expanded in a way that Silverman couldn’t do in such a short piece.

I think recent years have actually witnessed a decline in the popularity of sci-fi genre in the cinema. In discussing the impact of The Lord of the Rings in The Frodo Franchise (Chapter 9), I trace the ending of the major sci-fi franchises and the rise of their replacement: fantasy franchises. Already in late 2002, Lev Grossman wrote a perceptive article for Time, “Feeding on Fantasy” that noted the downward trend in sci-fi and the concurrent rise in the popularity of fantasy.

Fantasy films used to be considered box-office poison. In the January 2002 issue of Empire, Adam Smith published “Fantasy Island,” (which I can’t find online) listing a whole series of fantasy duds (Willow, anyone?). For some reason, Smith and some other like-minded commentators on this subject ignore the work of Tim Burton, whose Beetle Juice (1988) and Edward Scissorhands (1990) are surely classics of the genre.

Now perhaps it is science fiction that has become dubious box-office fare. Since 2000, sci-fi hits that were not part of an established franchise have been few and far between: War of the Worlds (2005), I, Robot (2004), and Planet of the Apes (2001). The first two had the advantage of starring two of the most popular actors in the world. Minority Report (2002) was considered a solid success, and again it had the advantage of Tom Cruise and Steven Spielberg’s names attached.

OK, Battlefield Earth was an unparalleled flop, but middling to disastrous sci-fi releases are easy to find (and here I’m defining sci-fi according to the genre lists on Box Office Mojo). Among the also-rans: AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001), The Adventures of Pluto Nash (2002), Solaris (2002), Simone (2002), The Time Machine (2002), Rollerball (2002), The Stepford Wives (2004), Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005), and, perhaps cursed by its title, Doom (2005).

Even Joss Whedon, who had tremendous success with Buffy the Vampire Slayer and its spin-offs, hit a brick wall with his sci-fi TV series Firefly and its film continuation Serenity (2005).

Fantasy, on the other hand, has become so prominent and so successful that it is hardly necessary to list examples. X-Men, Spider-Man, Rings, Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Pirates of the Caribbean are hugely popular franchises. Add on animated fantasies like those made by Pixar, and fantasy practically rules the box office. A surprising number of current big-budget projects are fantasies (among the most prominent, His Dark Materials: The Golden Compass).

By the way, here I include both the X-Men and Spider-Man series as fantasy rather than science fiction, which is debatable. Each offers some sort of physical explanation for the super-powers of their characters: various genetic mutations of uncertain cause, a spider bite during a school lab fieldtrip. These are not scientific explanations, though, at least not of the semi-plausible sort that sci-fi films usually delight in providing.

Genres move in cycles, and sci-fi films will probably return to prominence. For the moment, though, cable television seems to have become the medium where sci-fi thrives. Battlestar Galactica is one example. MGM is currently using the success of its “stalwart” Stargate series to move into foreign television markets. (For a Variety story, click here.) Stargate already has one spinoff, another is in the works, and two movies are planned. (Maybe MGM should reconsider that last idea.) There’s always the possibility of another Star Trek TV series.

Sci-fi films are far from moribund, however, and not everyone shuns calling them by that name. Most obviously, James Cameron’s ambitious project Avatar, currently announced for May 22, 2009, is underway. (The announcement in Variety calls it a sci-fi film.) A film often referred to as Star Trek XI has a release date of December 25, 2008.

Silverman’s article expresses puzzlement that in an era when science is such a prominent part of our lives, the genre of science fiction should loose favor. My own guess would be that it is precisely because technology is advancing at such a dizzying rate that stories about a real or alternative future may seem a bit tame.

When we casually refer to robots as “bots,” have mechanical dogs in our homes, and watch rovers photographing Mars, are films about robots quite as interesting as they used to be? Unless they star Will Smith, of course. When companies are actually planning to offer space tourism to paying customers within some of our lifetimes, are fictional rocket ships as intriguing? And perhaps we have simply by now seen stories based on these subjects a bit too often. Perhaps to find renewed respectability, the genre needs to move beyond its most familiar conventions.

Willow.

A many-splendored thing 12: The long goodbye

Two sides of the Triangle: Ringo Lam and Johnnie To.

My last day in Hong Kong, and still so much to say.

A few days ago I saw the new print of Patrick Tam’s Love Massacre (1981). It’s one of the stranger contributions to the Hong Kong New Wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The early stretches play as Antonioniesque scenes of alienation and loss, with a dash of Godard in the red/white/blue color design. About halfway through it becomes a movie about a stalker with a knife. Tam has great visual flair and devises some remarkable compositions and cuts, but I think that the film’s descent into gore comes too abruptly. We never understand the killer’s dementia, or his relation to his suicidal sister. Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia is as usual restrained and subtle in her performance, but such can’t be said for most of the other participants.

A few days ago I saw the new print of Patrick Tam’s Love Massacre (1981). It’s one of the stranger contributions to the Hong Kong New Wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The early stretches play as Antonioniesque scenes of alienation and loss, with a dash of Godard in the red/white/blue color design. About halfway through it becomes a movie about a stalker with a knife. Tam has great visual flair and devises some remarkable compositions and cuts, but I think that the film’s descent into gore comes too abruptly. We never understand the killer’s dementia, or his relation to his suicidal sister. Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia is as usual restrained and subtle in her performance, but such can’t be said for most of the other participants.

The seminar on Herman Yau’s films, “Herman’s Hermitage,” offered valuable critical commentary and a dialogue with Mr. Yau (right). A major cinematographer, Yau gained fame with two remarkably aggressive films, The Untold Story (1993) and Ebola Syndrome (1996). He has worked in many genres, lending a distinct local tang to cop dramas and even musicals. He’s a unique and energizing presence on the Hong Kong scene.

The seminar on Herman Yau’s films, “Herman’s Hermitage,” offered valuable critical commentary and a dialogue with Mr. Yau (right). A major cinematographer, Yau gained fame with two remarkably aggressive films, The Untold Story (1993) and Ebola Syndrome (1996). He has worked in many genres, lending a distinct local tang to cop dramas and even musicals. He’s a unique and energizing presence on the Hong Kong scene.

Two docus of note to fans of Asian film: In Development Hell (2007), Fukazawa Hiroshi chronicles the efforts of Teddy Chen to make Dark October, a film about Sun Yat-sen. As we follow Chen’s efforts, we learn of an earlier project undertaken by Chan Tung-man, father of prominent director Peter Chan Ho-sun. Tidbits about HK filmmaking emerge from comments by producers and directors.

Two docus of note to fans of Asian film: In Development Hell (2007), Fukazawa Hiroshi chronicles the efforts of Teddy Chen to make Dark October, a film about Sun Yat-sen. As we follow Chen’s efforts, we learn of an earlier project undertaken by Chan Tung-man, father of prominent director Peter Chan Ho-sun. Tidbits about HK filmmaking emerge from comments by producers and directors.

Yves Montmayeur’s In the Mood for Doyle (2006) follows Chris Doyle across a year of projects and interviews his collaborators, including Wong Kar-wai and Fruit Chan. Doyle appears somewhat calmer than I’ve seen him before (and certainly calmer than his reputation would indicate), and he shares some of his working methods.

Some points, such as the importance of place in determining a film’s style, Doyle has emphasized fairly often. But I’d never heard him say this before: “The choices you make push you in a certain direction, and that becomes what people call style.” Exactly right, methinks. Making a film is what technological historians call “path dependent”; one choice creates a limited but coherent set of future choices. The cascade of choices can precipitate into an overall stylistic pattern.

In a film with many good quotes, Peter Chan contributes another: “Working under the banner of a genre can give you more creative freedom.” In the Mood for Doyle and Development Hell would both be fine for festivals.

I have been written up a little in the Chinese-language press here and here. The loyal Golden Rock blogspot has pointed out that the stories misunderstood what I said in my blog about Johnnie To’s style.

Speaking of Johnnie To, as I frequently am: Last week he invited critics Lorenzo Codelli (below) and Shelly Kraicer and your obedient servant to dinner at his brother’s restaurant in Sai Kung. It was a wonderful meal, from the French sausages to the Kobe beef, prepared by the estimable Dracula Kwong. I never thought anybody would ever say this sentence to me: “And now meet Dracula.”

Soon Mr. and Mrs. To were singing American pop hits of the 1960s, including Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer.”

Ringo Lam, one of Hong Kong’s most celebrated filmmakers, dropped by.

Mr. Lam is the director of the middle section of Triangle, which I commented on in an earlier blog. In our conversation, he pointed out that the idea of taking off from another director’s story was something already present when he and Mr. To worked at TVB. The station would commission a 100-episode series (!), and either he or Mr. To would be responsible for the first five episodes. Then the next director would pick up the series and contribute another five installments, possibly taking the plots in entirely new directions. So this sort of serial production, a bit like Japanese linked verse, was already at work in Hong Kong popular culture.

Mr. Lam is known as bringing a level of harsh realism to the action pictures of the 1990s. In our conversation, he talked a lot about censorship troubles with the hard-edged School on Fire (1988). He also explained how he shot the jarring vehicle chase in Full Alert (1997) with virtually no retakes. “No problem! If other drivers see a crash or gunfire, they just drive around it.” Remarkably, Mr. Lam recalled reading our book Film Art when he was studying film in Canada.

Shu Kei has made a brief, gentle film called Ten Years, centered on a pair of dancers at the Academy for Performing Arts, where he is head of the School for Film and TV. Without words, accompanied solely by a Keith Jarrett piece, it tells its story through abstract compositions and carefully selected details.

A plush new local magazine, Muse, has published Vivienne Chow’s discussion of attitudes toward the festival. The story, not available online, discusses the festival’s efforts to broaden its public and seek commercial sponsorship. For many years after its launch in 1977 HKIFF ran as a municipal venture, but recently it went private. Now several high-profile companies like Giordano, Diesel, Starbucks, Shui On Land, and others support it. The festival has filled the central city with banners and billboards and created many red-carpet events, which generate press coverage and sizable local turnout.

Some long-time supporters feel that HKIFF has been pandering to the mass audience. They suggest that the festival’s principal mission was once to bring to Hong Kong the rare films, usually European, that wouldn’t be shown theatrically. Others resent the influx of viewers who aren’t strict cinephiles. One loyal festival attender is quoted in Chow’s piece: “The gimmicks and publicity brought in a lot of non-regulars who do not have much theater etiquette.” Long-timers complain of cellphone chatter and rude patrons.

As an outsider, I offer my $.02.

There are now a huge number of festivals, chasing the same films, lusting for red-carpet events. In Asia alone, Pusan, Tokyo, and Shanghai have become strong contenders, all more or less imitating Hong Kong. Moreover, the western world has finally recognized that Asia is a source of tremendous cinematic innovation, and now the big European and American festivals are cherry-picking films and filmmakers. If Wong Kar-wai can premiere his film at Cannes, why should he offer it to Hong Kong a month before? The HKIFF is hurt by its years of success: many of the filmmakers it introduced to the world are now snapped up by other festivals.

Just as important, the festival has offered comprehensive documentation of local cinema. Recognizing that Hong Kong film was largely unknown, the festival set about creating retrospectives and publications that brought to light the entire history of a great tradition. (On right, the festival’s book on the 1970s.) Without the precious catalogues published by the festival, both Chinese and westerners would know much less about Hong Kong cinema. The festival’s mission of education and scholarship has continued unabated, matched by the programs and publications of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Just as important, the festival has offered comprehensive documentation of local cinema. Recognizing that Hong Kong film was largely unknown, the festival set about creating retrospectives and publications that brought to light the entire history of a great tradition. (On right, the festival’s book on the 1970s.) Without the precious catalogues published by the festival, both Chinese and westerners would know much less about Hong Kong cinema. The festival’s mission of education and scholarship has continued unabated, matched by the programs and publications of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

The festival shrewdly merged with a broader event, the Entertainment Expo, which included Filmart, the Asian Film Financing Forum, and the Asian Film Awards. Variety reports that a lot of business was done at Filmart, and the Awards were broadcast and rerun on Chinese television. In all, the festival seems to have created a unique identity for itself as a regional gathering place for both industry types and film fans.

Like all great festivals, this is really many festivals in one. Confronted by nearly 300 programs in 23 days, you’re in a vast cafeteria. You could, as I did, stick close to the Hong Kong retrospectives and archival shows. But you could also attend a rich array of avant-garde screenings, highlighted by the Paolo Gioli work. Or a documentary thread, including Enemies of Happiness and Nanking. Or a sampling of contemporary Asian film, showcasing dozens of works from South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, India, and on and on. Viewers craving contemporary European items had a chance to see eight films from Romania, eight from Germany, eight from the Nordic countries, and assorted titles from France, Italy, Portugal, and elsewhere; not to mention retrospectives of Visconti and Pedro Costa.

Add to this the enormous friendliness of everyone you encounter and the sheer exhilaration of being in this city. It would be ungrateful to ask for more. For the chance to see all these movies and wander through Hong Kong, I’d let Starbucks stamp its logo in my tooth fillings.

Will I see you here next year?

The Celestial Multiplex

Kristin here—

The Internet is mind-bogglingly huge, and a lot of people seem to think that most of the texts and images and sound-recordings ever created are now available on it—or will be soon. In relation to music downloading, the idea got termed “The Celestial Jukebox,” and a lot of people believe in it. University libraries are noticeably emptier than they were in my graduate-school days, since students assume they can find all the research materials they need by Googling comfortably in their own rooms.

A lot depends what you’re working on. For The Frodo Franchise, studying the ongoing Lord of the Rings phenomenon would have been impossible without the Internet. A big portion of its endnotes are citations to URLs. On the other hand, my previous book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, a monograph on the stylistic and technical aspects of Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, has not a single Internet reference. Lubitsch can only be investigated in archives and libraries, where one finds the films and the old books and periodicals vital to such a project.

Vast though it is, the Internet is tiny in comparison with the real world. Only a minuscule fraction of all the books, paintings, music, photographs, etc. is online. Belief in a Celestial Jukebox usually works only because people tend to think about the types of texts and images and sounds that they know about and want access to. Yes, more is being put into digital form at a great rate, but more new stuff is being made and old stuff being discovered. There will never come a time when everything is available.

Even so, every now and then someone proclaims that in the not too distant future all the movies ever made will be downloadable for a small fee, a sort of Celestial Multiplex. A. O. Scott declared this in “The Shape of Cinema, Transformed at the Click of a Mouse” (New York Times, March 18): “It is now possible to imagine—to expect—that before too long the entire surviving history of movies will be open for browsing and sampling at the click of a mouse for a few PayPal dollars.”

Not only that, but Scott goes on, “This aspect of the online viewing experience is not, in itself, especially revolutionary.” He’s more interested in the idea that online distribution will allow filmmakers to sell their creations directly to viewers. That would be significant, no doubt, but as a film historian, I’m still gaping at that line about “the entire surviving history of movies.” Such availability would not only be “revolutionary,” it would be downright miraculous. It’s impossible. It just isn’t going to happen.

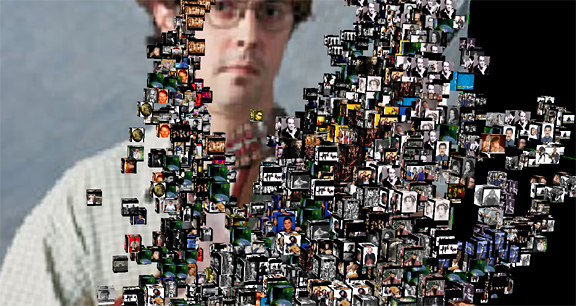

(The image above was generated to publicize the “Search inside the Music” program that is an important part of the Celestial Jukebox. Imagine movie screens with actors’ faces in those little boxes, and you’ve got the Celestial Multiplex.)

I will give Scott credit for specifying “surviving” films. Other pundits tend to say “all films,” ignoring the sad fact that great swathes of our cinematic heritage, especially in hot, humid climates like that of India, have deteriorated and are irretrievably lost.

Dave Kehr has already briefly pointed out some of the problems with Scott’s claims, mainly the overwhelming financial support that would be needed: “Tony Scott’s optimism struck me as, well, a little optimistic.” On the line about “the entire surviving history of movies,” Kehr suggests, “That’s reckoning without the cost of preparing a film for digital distribution — the same mistake made by the author of the recent vogue book ‘The Long Tail’ — which, depending on how much restoration is necessary, can run up to $50,000 a title. None of the studios is likely to pay that much money to put anything other than the most popular titles in their libraries on line.” As Kehr says, the numbers of films awaiting restoration and scanning isn’t in the hundreds, as Scott casually says. No, it’s in the tens of thousands even if we just count features. It’s more like hundreds of thousands or more likely millions if we count all the surviving shorts, instructional films, ads, porn, everything made in every country of the world. To see how elaborate the preservation of even one short medical teaching film can be, go here.

Putting aside the need for restoration, newer films present a daunting prospect. To help put the situation in perspective, let’s glance over the total number of feature films produced worldwide during some representative years from recent decades (culled from Screen Digest‘s “World Film Production/Distribution” reports, which it publishes each June): 1970, 3,512; 1980, 3710; 1990, 4,645; 2000, 3,782; and 2005, 4,603. For me the numbers conjure up the last shot of Raiders of the Lost Ark, only with just stack upon stack, row upon row of film cans.

Scott isn’t the first commentator to prophesy that all films will eventually be on the Internet. It’s an idea that crops up now and then, and it would be useful to look more closely at why it’s a wild exaggeration. It’s not just the money or the huge volume of film involved, though either of those factors would be prohibitive in itself. There are all sorts of other reasons why the advent of practical digital downloading of films will never come close to providing us with the entire history of cinema.

Coincidentally, two experts on this subject, Michael Pogorzelski, Director of the Film Archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Schawn Belston, Vice President, Film Preservation and Asset Management for Twentieth Century Fox, visited Madison this past week. Mike got his MA here in the Dept. of Communication Arts and now returns about once a year to show off the latest restored print that he has worked on. Schawn isn’t an alum, but he has also visited often enough that most students probably think he is. The two brought us the superb new print of Leave Her to Heaven that Fox and the Academy have recently collaborated on.

I figured it would be very enlightening to sit down with these two and talk about why the Internet is never going to allow us to watch just anything our hearts desire. They kindly agreed, and with my trusty recorder in tow we went for burgers—and fried cheese curds, a commodity not available in Los Angeles—at the Plaza Tavern. I’m grateful for the fascinating insights they provided into some of the less obvious obstacles to putting films on the Internet en masse.

No Coordinating Body

Before we launch in, though, one point needs to be made: there is no single leader or group or entity out there organizing some giant program to systematically put all surviving movies on the Internet. There isn’t a set of guidelines or principles. There’s no list of all surviving films. How would we even know if the goal of putting them all up had been achieved? When the last archivist to leave turned out the light, locked the door, and went looking for a new line of work?

Most of the physical prints that would be the basis for such transfers are sitting in the libraries of the studios that own them or in the collections of public and private archives (including many individuals). The studios would make films available online for profit. The archives might be non-profit organizations, but they still would need to fund their online projects in some fashion, either by government support, from private grants, or by charging a fee for downloads. Most archives are more concerned about getting the money to conserve or restore aging, unique prints than about making them widely available. Preservation is an urgent matter, and making the resulting copies universally available for public entertainment or education is decidedly a secondary consideration.

Mike works for a non-profit archive, Schawn for a studio, so together they provide a good overview of some key problems facing the creation of an ideal, comprehensive collection of movies for download.

Money

People who claim that all surviving films could simply be put on the Internet don’t go into the technology and expenses of how that could be done.

Of course, Schawn says, studios want to “digitize the library.” That phrase is highly imprecise, however. He specifies, “For the purposes of this idea of media being online, available, downloadable, streamable, whatever, that’s something that we’re dealing with now using existing video masters. So there isn’t an extra cost to quote, unquote digitize. But there is a cost to make the compression master, what we’re calling at Fox a ‘mezzanine file,’ which is basically a 50 megabit file. That’s the highest-quality ‘low’ quality version of the content from which you can derive all of the different flavors of compression for the various websites that have downloadable media.

“There’s a huge problem with this, in that Amazon, iTunes, and Google all have a slightly different technical specification of how they need the files delivered to them. If you don’t have this kind of mezzanine file, you have to make a different compressed version for each one of these, which costs something, certainly. It’s not incredibly expensive, but it’s not free.

“So why? What’s the motivation to us to compress at Fox the entire library? I don’t know. Are we going to sell enough copies of Lucky Nick Cain [a 1951 George Raft film] compressed on iTunes to cover the costs of making the compression? I don’t think so.”

Compatibility and the Onrush of Technology

Schawn’s mention of the variety of files needed by the big download services raises the problem of compatibility. It’s not just a matter of supplying the files and then forgetting about the whole thing, assuming that the film is available to anybody forever. What about new standards and formats?

Shawn: “Just as with consumer video, the standard changes, so what used to be acceptable yesterday isn’t acceptable now in terms of technical quality.” As time passes, plug-ins make access faster and cheaper, and eventually the original files don’t look good enough. He points out that currently iTunes can’t download HD. If it becomes possible later, “If you want to get 24 in HD, what Fox will have to do is go and re-deliver all the files in HD.” And presumably re-deliver again when the next big format revolution occurs.

Mike explains further, “Using the mezzanine file, you would just have to continue to reformat it to whatever the players demand. The lowest of the low quality will keep going up as people have broadband and can handle larger chunks of data faster.”

What about the film you’ve already downloaded? You acquire films using plug-ins, which change. Think how often you’re told that an update is now available. If you go ahead and keep updating, the changes accumulate. Eventually you may not be able to play the download you paid for. Quicktime will have moved way beyond what the technology was when you made your purchase.

Schawn and Mike both point out that at this stage in the history of downloading, the level of quality is still pretty bad in comparison with prints of films in theaters or on DVDs. It would be nice to think that the virtual film archive could provide sounds and images worthy of the movies themselves, but that will take a long, long time–not the “before too long” that Scott envisions.

Copyright

I raised another matter: “But what about copyright? Every time I hear something about restoration or bringing something out on DVD, it’s, ‘Well, there are rights problems.’ And some of those rights problems don’t get resolved. I assume that quite a few films that they blithely believe can be slapped up for downloading can’t be slapped up.”

Schawn: “Sure, and there are often not any kinds of provisions in the contract about Internet distribution—obviously! So you’re right, how do you deal with that?”

He pointed to Viva Zapata as a film that Fox has restored but can’t make available due to rights issues. The potential sales are not thought to warrant paying to resolve those issues. “I’m sure there are lots of titles in everybody’s libraries that you can’t just pop up on the Internet and start selling.”

The copyright barrier is worse for archives, which seldom own the exhibition or distribution rights to the films they protect. Usually—though not invariably–the studios do not object to archives owning and preserving prints. Making money through showing them or selling copies would be quite another matter.

Mike described the online presence of archival prints. “On a much smaller scale, this is being attempted in the archive world already, like on Rick Prelinger’s site [Prelinger Archives] or on the Library of Congress’s site, where they’ve put up dozens of moving-image files. True, it’s not independent cinema and it’s mostly commercials and the paper prints that have recently been restored. On Prelinger’s site it’s all the industrial films that he’s collected over the years. That has seen a good amount of traffic, but it hasn’t created new audiences for these films, I would argue. At least, not on a huge scale.”

Prelinger’s site contains only public-domain items, including the ever-popular Duck and Cover, allowing him to avoid the problem of copyright. Similarly, the Library of Congress gives access primarily to films in the pre-1915 era.

Suppose an archive and a film studio both have good-quality prints of a minor American film made in the 1940s. The archive does not have the legal right to put it online, and if the studio decides that it does not have the financial incentive to do so, that film will not be made available for downloading. A private collector might possibly create a file and make it available, but he or she would risk being threatened by the copyright-holder.

Piracy

We briefly discussed the methods used to prevent pirated copies being made from downloaded films. Like DVDs, downloads can be pirated, with people sending copies to their friends or even offering downloads for a fee in competition with the copyright holder. Copy-protection codes might make it necessary for a purchaser to keep a downloaded copy only on a hard-drive without being able to burn it onto a DVD. Another type of code could erase the file once the film had been viewed once or twice. That’s not exactly conducive to the ideal archive of world cinema, where we would hope to be able to study a film in detail if we so choose.

One might think that piracy protection mainly applies to studios, with their need to make money. Mike points out, though, that the need for such protection “even applies to the archival model, too. For films that you mention that have gone out of copyright, there’s still the same costs associated with putting a silent film that no one owns–digitizing it, creating the compressed master that goes on the Web—and they aren’t the kinds of subjects that people are going to get rich on at all, so there isn’t a lot of piracy. You don’t hear many archivists complaining, ‘Hey, you took my 1911 Lubin film, damn you! You can’t put that on your Website. That belongs on the archive’s Website.’ But that scenario becomes more of a likelihood for more popular titles. The obscure 1911 Lubin film is on one extreme, but Birth of a Nation, a well-known silent film a lot more people would like to see, is on the other. Let’s say the highest-quality copy is on the Museum of Modern Art’s Website and can be easily lifted and posted on your own site. And even if you just say, ‘Oh, I’ll charge 99 cents or I’ll charge 50 cents to stream it,’ it’s still going to be someone taking over something that the archive put all of the high-end effort and money into doing. Frankly, I think unless it’s an archive with a national mandate and a little bit higher budget to digitize and to put the contents of their archives online, there’s not going to be any motivation to make that high-end investment up front.”

Thus an archive may simply not bother to put a film on the internet because it can’t guarantee recouping the costs that would be generated.

Language and Cultural Barriers

Scott’s notion of easy access to all of surviving world cinema implicitly depends on an idea that all these films are either English-language or already subtitled or dubbed for English-speaking users.

That’s not true for a start, so there would remain a great deal of work to translate films that have never been released in English-language markets. That’s another huge, expensive task.

Then there’s the opposite side of that coin. For truly complete access, everyone in the world, whatever language they speak, would be able to download and appreciate every film. Of course, there are billions of people without computers or Internet access, and it looks unlikely that being able to go online will become universal anytime soon. (For figures on numbers of people with internet access, check here; percentages can be calculated by clicking on each country and finding the total population. In Tajikistan, for example, .07% of the population was online in 2005. One has to assume that a lot of connections in some of those countries are dial-up, so downloading films would be virtually impossible. [June 21, 2010: In 2008, Tajikistan’s online population has grown to .08%.])

So let’s just say that for the foreseeable future downloadable films would “only” need to be subtitled in the languages of countries or regions where significant numbers of people subscribe to PayPal.

In our conversation, Schawn pointed out that digital compression files mean that there can be huge numbers of versions, with different soundtracks dubbed in or different subtitles added. Technically it’s possible to do all that translation. Still, “it’s very complicated. So for worldwide distribution of anything, like you’re talking about your silent film. If you’re in Pakistan, do you get the American version of the movie or do you get the version of the movie with the intertitles appropriate to wherever it is that you’re showing it? If so, that quickly compounds the amount of stuff that’s digitized.”

I responded, “Yeah, or a 1930s Japanese film put on the Internet for downloading, subtitled in every language where there are people that can pay for it. The more you think about it, the more absurd it becomes.”

Scott must be implying as well that there is some single “original” version of a film and that that version would be the one available in this ideal collection in cyberspace. Yet any archivist or film historian knows that multiple versions of a given film are typically made, depending partly on the censorship laws of the different countries where it is originally shown. In making downloadable files available, does a studio or archive use only the original version of a film made for its country of origin and thus risk having it include material offensive to viewers in some places where it might be downloaded? Or does a whole slew of different versions, one acceptable in, say, Iran, another inoffensive to the Danes, and still another compatible with Senegalese social mores, get put online? How could one even gather all such versions and digitize them? National film archives tend to have government mandates to concentrate primarily on preserving their own countries’ films. Not every version of every film gets saved.

The Bottom Line

For all the reasons noted here and others as well, film availability for download will follow pretty much the same economic principles that have governed film sales in other media. Mike’s opinion is, “Whether they’re from an archive or a studio, I think things’ll start going online in the same pace that they came onto DVD, in an eight to ten-year cycle. And there still will be large gaps.”

Schawn interjects, “Just as there are on DVD.”

Mike concludes, “There’s stuff that will never go online. Yeah, just as on DVD.”

*

A truly celestial screening: a restored 35mm print of Bertolucci’s 1900 projected free, under the stars in the Piazza Maggiore, Bologna, summer of 2006