Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Snakes, no, Borat, yes: Not all Internet publicity is the same

Kristin here–

This past summer I had my first experience of being quoted as a pundit in a major newspaper. The Los Angeles Times was planning a story on the internet buzz around Snakes on a Plane and more specifically around the fact that some of that buzz had actually influenced New Line to change the film.

In late July I had completed the final revision and updating on The Frodo Franchise. Two chapters cover the official and unofficial internet publicity for The Lord of the Rings. The last thing I had added to those chapters was a reference to the Snakes internet phenomenon—which was still ongoing, of course, since the film was not released until August 18. The connection is closer than it may appear, since New Line distributed both films.

Dawn Chmielewski, of the LA Times, got wind of my work on fans and the internet. She called me, and we had a pleasant 40-minute conversation. The result was one pretty uncontroversial statement from me near the end of the story, describing how studios have a mixed attitude toward fan sites on the internet: “It is a phenomenon where the studios are having to keep a delicate balance between, on the one hand, wanting to use this enormous potential for publicity, and on the other hand have to control over copyrighted materials and over spoilers.”

This story was part of the huge amount of attention paid to the Snakes phenomenon, with Brian Finkelstein, webmaster of the main fan site, Snakes on a Blog, widely quoted about how New Line had cooperated with him and even invited him to LA for the premiere. One of the main points of interest to the media was that New Line had added a line of dialogue that had originated on a fan site for Samuel L. Jackson’s character. The studio also added some sex and gore, moving the film’s rating from PG-13 to R.

Fans’ influencing films was not entirely new by this point. After The Fellowship of the Ring came out in 2001, two fans elevated a non-speaking elf extra from the Council of Elrond to fame by dubbing him “Figwit” and starting a website devoted to him. As a salute to the fans, the filmmakers brought the extra back and gave him one line to say in The Return of the King, where he is credited as an “Elf escort.” That phenomenon, however, didn’t get much notice beyond fan circles. The Snakes revisions got far more attention.

Much was made of the fact that industry officials were eager to see whether wide internet buzz—especially when covered by mainstream news media—would translate into boffo box-office figures. As we all know by now, Snakes was a deemed a failure. New Line said that its opening gross was typical for a low-budget genre film. Snakes cost a reported $33 million. Ultimately it took $34 million in the domestic market and a total of just under $60 million internationally. I suspect that New Line spent a great deal more on advertising that it ordinarily would have, hoping in vain to expand the enthusiasm. The film’s box office takings would certainly not bring in a profit, but doubtless New Line hopes for better things on DVD. That DVD was released on January 2, so no sales figures are available yet, but the widescreen edition is doing reasonably well at #19 on Amazon.

The film’s disappointing ticket sales led to questions. Why would fans spend so much time on the internet and generate such hype and then not go to the film? After all, fans created parody posters, music videos, comic strips, and photos on their sites, as well as designing T-shirts and other mock-licensed products. (The DVD supplement “Snakes on a Blog” presents a generous sampling of such homages; see also Snakes on Stuff.com.) And if that much free hype—even aided and abetted by the studio—didn’t translate into ticket sales, was the internet all that useful for publicizing films?

The film’s disappointing ticket sales led to questions. Why would fans spend so much time on the internet and generate such hype and then not go to the film? After all, fans created parody posters, music videos, comic strips, and photos on their sites, as well as designing T-shirts and other mock-licensed products. (The DVD supplement “Snakes on a Blog” presents a generous sampling of such homages; see also Snakes on Stuff.com.) And if that much free hype—even aided and abetted by the studio—didn’t translate into ticket sales, was the internet all that useful for publicizing films?

Of course fan sites had already proven their worth for New Line’s own Austin Powers: Man of Mystery and Lord of the Rings. Other films had benefited from free fan labor and enthusiasm. Famously The Blair Witch Project became a massive hit primarily because of the internet. But anytime a hitherto dependable formula results in even a single failure, the studio publicity departments go into a tizzy of doubt. It’s true of genres, stars, and just about any other factor you can name. Snakes fails, so maybe the internet isn’t that powerful a publicity force.

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan came along to confuse things even further. It, too, had a huge fan presence on the internet. In this case, the main activity was the posting of clips on YouTube. Well before the film was released on November 3, deleted footage and some scenes from the film were showing up. There were about 2000 by then, and as of yesterday a search for “Borat” on YouTube yielded 6,293 items.

It came to be a joke on the internet: “What is the difference between Google and Borat? The latter knows how to make money from YouTube.” (“Borat” was recently reported to be one of the top search terms on Google in 2006.) Webmasters and chat-room denizens who were already fans of Sacha Baron Cohen from Da Ali G Show, where the Borat character originated, promoted the film. The internet buzz probably led to more coverage of the film in mainstream infotainment outlets than would have otherwise occurred.

Borat’s reported budget was $18 million. To date, it has grossed $126 million domestically and a total of $241 million worldwide.

The timing of the two events triggered much press coverage and show-business hand-wringing. What did it all mean? Is the fan-based sector of the internet good for films or not?

This isn’t some idle question as far as the industry is concerned. Twentieth Century Fox wisely encouraged all the Borat uploaders at YouTube. Far from threatening to sue over copyright, they leaked footage. Then, however, shortly before the film’s release, audience research (that highly dubious tool in which studios put such faith) revealed that many members of the public had never heard of Borat. What to do? At the last minute Fox cut back the number of theaters in which the film would be shown. Did anyone else in the world think that was a good idea?

Back on November 11, with Borat freshly successful and speculation about internet coverage rife, I promised to explore how the two films differed when it came to internet hype and success. That would be possible to do without seeing either film. I saw both, though. Like many others, I watched Borat in a theater and Snakes on DVD.

Others have offered reasons for the difference. On NPR, Kim Masters made some plausible observations. Snakes, she points out, “was a film with a very broad concept—Samuel L. Jackson battles snakes on a plane. The buzz took off on thousands of Web sites as the film became the butt of many jokes. The problem is that the movie wasn’t really meant to be that funny. Borat, on the other hand, is meant to be funny.” True enough. In fact, Snakes has a weird mixture of tones, starting off with a highly non-humorous scene of a gangster killing a man with a baseball bat. It goes on to interject funny moments in the midst of grim ones in a seemingly random way.

Moreover, Masters claims, the buzz for Snakes “took off too fast” and in the wrong places. The sites making all the jokes and parodies weren’t the same ones that horror fans frequent, and the humor may in fact have created a negative reaction among what would ordinarily have been the film’s target audience. Borat had no such problem. Fans of comedy and especially of Cohen spread the word to likeminded fans through what is termed viral marketing in the publicity business.

All true, and yet, having studied Lord of the Rings fan sites for a long time, I think there was another crucial factor that never occurred to the anxious studios. That factor was what the fans were doing with the films on their websites, in chat rooms, and on YouTube.

Many popular films, especially in genres like fantasy, science fiction, action, and horror, generate fanfiction, fanart, spoofs, and other creative responses. Snakes on a Plane offered the inspiration for all sorts of clever writing and drawing and videomaking through its title alone. As was pointed out over and over, from that title and the casting of Jackson, everyone knew what the film would be like. It could be parodied without even being seen. Indeed, I suspect that after months of posting and mutually enjoying hundreds of amusing riffs on “Snakes on a Plane,” many fans realized that they could never have as much fun watching the film as they had playing around with its title and concept. It had never been the movie itself they were really interested in.

Borat’s full, unwieldy title was also an attention-getter, but no one could possibly predict much about the film from it, let alone parody it. Here the focus was primarily on how funny Cohen was as Borat and how funny the film was going to be. What circulated were samples that seemed to prove exactly that. People would go to this film and have more fun than they could possibly make for themselves by messing around on the internet with its title. The words “snakes on a plane” could inspire just about anybody with a creative bone in their body, but only Cohen could do Borat.

Print and broadcast media spread the same message. For Snakes, they had zeroed in on the internet coverage and stuck with that. End message: there is a lot of fan attention being paid to a rather silly-sounding film. For Borat, they had Cohen appear as an interviewee.

Cohen brilliantly manipulated the infotainment outlets, especially the chat shows, by appearing in character as Borat. As the film’s release approached, Cohen was a hot property, a ratings booster. Talk-show hosts and soft-news reporters presumably couldn’t alienate him by insisting that he speak as himself. Maybe they didn’t want to. As a result, three things happened. First, the endlessly talkative Borat dominated each interview. On The Daily Show, the ordinarily in-charge Jon Stewart was totally unable to control the situation and frequently cracked up, once badly enough that he had to turn his back on the audience momentarily.

The second result was that each appearance by “Borat,” supposedly there to talk about the film, ended up being a hilarious performance by Cohen, ad-libbing on everything around him—the chairs, the coffee mugs, the cameras, the audience. Spectators ended up with one impression about the film: it was about this incredibly funny guy doing incredibly funny things.

Third, there could be no discussion of the less savory aspects of Borat, the ones that mostly surfaced after the film was already a hit. These included allegations that people had been manipulated by false claims into signing consent forms and “performing” in the film. One has to suspect that when Cohen was explaining his project to them, he may have appeared as his own rational self and not in the wild-and-crazy persona of Borat. The stylistics of the film itself betray many points at which encounters with real people could have been manipulated. Who knows what the crowds at the rodeo where Borat butchers the national anthem were actually reacting to? None of their responses is ever visible in the shots of Borat. How many non-bigoted interviews were thrown out for every bigoted one that could be used?

The point is, though, that the interviews were like the internet clips, furnishing more evidence of how entertaining the film would be. Borat could provide a sort of creativity that was all his own, and fans could never imagine it ahead of seeing the film or create a more fun version of it themselves. Many, many of the people who posted or read stuff about Borat on the internet went to the film.

Ultimately the studios have yet to emerge from their early love-hate relationship with fan-generated publicity on the internet. They dread the early posting of bad reviews and crave good ones, naturally. But they still seem to believe that most other online publicity means the same thing: eyeballs on monitors should equal bottoms in theater seats. Publicists have not yet grasped that fans don’t go to the web just to talk about films and learn about films. They do things with films, and different films inspire different sorts of activities. Those different activities may or may not mean that the fan ultimately wants to see the film itself.

In most cases they probably do end up seeing the film. Snakes on a Plane is most likely an aberration, as Blair Witch was. But Snakes does prove one other thing. Fawning attention paid to the webmasters and bloggers who launch these unofficial campaigns is no guarantee of success. The “Snakes on a Blog” supplement displays some interesting aspects of New Line’s wooing of the main fans involved in the online hype. The documentary seems to have been made at just about the time Snakes was released. It ends with the bloggers, by invitation, on the red carpet at the Chinese Theater for the film’s premiere and later at the bloggers’ party put on by New Line at a bar. The whole tone is very enthusiastic about the internet’s impact on the film’s success; there is no sense that the film will disappoint and raise doubts about the value of fan publicity. There is also the implicit suggestion that fans starting future film-related blogs might get similar encouragement and hospitality from studios.

Clearly no amount of studio cooperation and attention to fans’ interests will make a film succeed if the right blend of ingredients isn’t there. Nevertheless, fans’ enthusiasm and willingness to spend great amounts of time, effort, and even their own money to create what amounts to free online publicity for films is of incalculable value to the studios. Yet for the most part those studios are still making only grudging, limited use of this amazing resource. The resentment they garner from fans as a result may be squandering part of that resource’s potential.

Gradually, though, the studios are giving up their policy of stifling the fans by making vague threats about copyright and trademark violations. If they go further and actually learn how fans use all the amazing access the internet has given them, maybe movie executives can relax and recognize the obvious answer to the current debate: Yes, fans on the internet are good for the movie business.

Good Actors spell Good Acting, 2: Oscar bait

Kristin here–

David and I seem to be swimming against the stream of end-of-year blog entries. No ten-best lists, no predictions about Oscar nominations.

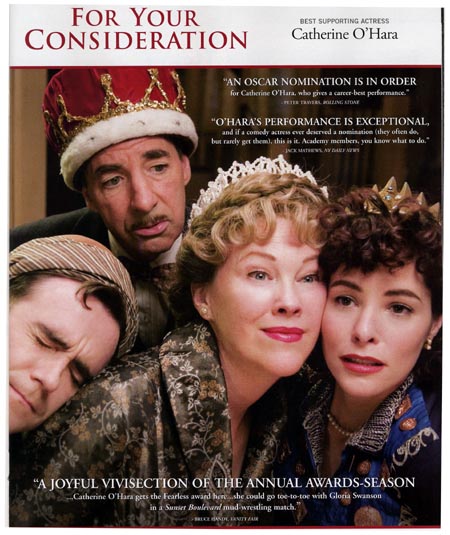

Instead, I’ll develop on the theme I introduced in my entry concerning the over-emphasis on star turns in reviews of films that contain an obviously outstanding performance. It’s interesting that quotes from such reviews are now routinely used in the “For Your Consideration” ads in show-business trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter when a studio is pushing a performance for award nominations.

There are a lot of good performances in any given year. We’ve all seen reviews that call a performance “Oscar-worthy” without the actor ending up getting nominated or even mentioned by pundits at year’s end predicting those nominations. Some types of performances just seem more like Oscar bait than others. What makes them that way?

Some of the reasons are apparent to almost anyone who pays any attention during the awards season. Notoriously, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences members prefer to honor dramatic roles rather than comic or musical ones. In 1985, a good deal of outrage was expressed—and rightly so–over the fact that Steve Martin was not nominated for his hilarious turn in All of Me. Conversely, the nomination of Johnny Depp for a comic role in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl created a stir, though few probably thought that he would actually win. (Remember, just being nominated is an honor, as nominees—and who would know better?—often point out.)

So, actors tend to be nominated for serious roles. Not just any kind of serious roles, though. History teaches us that playing a real person gives one’s chances for a “nod” (as nominations are for some reason now called). From Paul Muni in The Story of Louis Pasteur to George C. Scott in Patton to Ben Kingsley in Gandhi to Phillip Seymour Hoffman in Capote, it’s a familiar pattern. In the television age, when famous people’s appearances and behaviors are often familiar to the public, performances can become in part a matter of impersonation, and a skill at mimicry becomes a strong signal of “good acting.” Undoubtedly a performance like Helen Mirren’s as Elizabeth II in The Queen adds subtleties that go beyond the imitation of appearance and speech patterns and other obvious characteristics, but it’s the impersonation that gets talked about more.

Even when we’re not familiar with the person a character represents, for some reason it helps to have “based on a true story” attached to a title. Publicity often stresses that the actor met and spent time with the real person in order to craft an authentic performance.

Obviously making oneself less attractive to play a role gets Brownie points in a big way: Robert DeNiro gaining 60 pounds to play boxer Jake La Motta in Raging Bull, Charlize Theron sacrificing glamor in Monster, Nicole Kidman sporting an unflattering fake nose as Virginia Woolf in The Hours.

Characters with disabilities can definitely put an actor into the Oscar-bait realm: Cliff Robertson in Charly, John Mills in Ryan’s Daughter, Daniel Day Lewis in My Left Foot, or Jack Nicholson in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Presumably the implication of playing a real person or gaining weight for a role or simulating a disability all imply work, harder work than “just” playing a healthy, good-looking fictional person.

There are other indicators for nomination likelihood.

It helps to be old. Think Helen Hayes in Airport or Art Carney in Harry and Tonto. Their best performances? This year Peter O’Toole may finally get a non-honorary acting statuette.

It helps to be English and to have done Shakespeare.

For that matter, it helps to speak English. We’ll see if Penélope Cruz ends up being one of the very few to succeed without doing so. She did get nominated for a Golden Globe for Volver, but foreign-language films are definitely an afterthought when it comes to Academy Awards.

It helps to be Meryl Streep, whose performances don’t even have to fit any of these tendencies.

Oddly enough, most of these generalizations don’t seem to apply as much to the supporting-actor categories. Presumably “supporting” implies a less bravura turn that doesn’t compete with the stars.

Of course there are all sorts of reasons why actors get Oscars. A lot of people were surprised in 1997 when Juliette Binoche (The English Patient) beat out Lauren Bacall (The Mirror Has Two Faces) as Best Supporting Actress. It helps to recall that three years earlier, through a technicality, Binoche had been judged ineligible to be nominated for Best Actress in Three Colors: Blue. The injustice of that clearly rankled Academy members (the majority of whom are actors), and the first time they had a chance to make it up to Binoche, they did. Both Jimmy Stewart and Denzel Washington supposedly won their Best Actor awards because voters felt they had deserved them for previous roles.

On Thursday the Golden Globes nominations were announced. Reporting on the Globes tends to center around their predictive powers for the later Academy Awards. (See “And … They’re Off!” in the new Entertainment Weekly.) The Globes are just as interesting, though, for the fact that they divide the main film-acting awards into two categories: “Drama” and “Musical or Comedy.” (Two parallel best-picture awards are given in these categories as well, but for some reason the supporting-actor awards aren’t divided by genre.) So Sacha Baron Cohen and Johnny Depp can get nominated for comedies and not have to compete against Will Smith and Forest Whitaker in dramas.

If you like endless speculation on nominees-to-be, check out the December 2006 Hollywood Reporter issue “The Actor.” In it Stephen Galloway talks about actors playing real people: “Whether a story surrounding a character is biographical or fictionalized, actors are determined to find the truth behind their real-life role models” (“As a Matter of Fact”). Part of the reason that the trade press devotes so much space to awards speculation is because these special issues sell lots of “For Your Consideration” ads. This year my favorite one touts Catherine O’Hara as best supporting actress. They don’t even have to tell us the title.

By Annie standards

Kristin here—

Way back in 1979, I published a theoretical essay on animation.* It explored how animation is different from live-action because it can mix types of perspective cues within the same image. That was basically the only original idea I have ever had about animation, and I never followed it up by writing more on the subject.

At that point, animation studies were lagging behind film studies in general. A single essay in the area was enough to brand one as an expert. Ever since people have thought of me as an expert on animation. By now, though, animation studies have grown into a healthy area of scholarship, with its own journals and conferences. There are many people studying animation who know far more about it than I. My only work in this area since 1979 has been to write most of the sections on animation in Film Art and Film History.

Still, that leaves me the resident animation expert on this blog, and since I seem to end up writing about the subject occasionally, we’re adding it as a new category as of this entry.

Among the new films I’ve seen in the past couple of years, I find that a significant proportion are animated. I don’t think that’s because I prefer animated films but because these days they are among the best work being created by the mainstream industry.

Why would that be? There are probably a lot of reasons, but let me offer a few.

Animated films, whether executed with CGI or drawings, demand meticulous planning in a way that live-action films don’t. David has written here about directors’ heavy dependence on coverage in contemporary shooting. Coverage means that many filmmakers don’t really know until they get into the editing room how many shots a scene will contain, which angles will be used, when the cuts will come, and other fairly crucial components of the final style. This is true even despite the fact that filmmakers increasingly have storyboarded their films (mainly for big action scenes) or created animatics using relatively simple computer animation.

People planning animated films don’t have the luxury of lots of coverage, and that’s probably a good thing. Storyboards for animated films mean a lot more, because it’s a big deal to depart from them. Every shot and cut has to be thought out in advance, because whole teams of people have to create images that fit together—and they don’t create coverage. There aren’t many directors in Hollywood who think their scenes out that carefully. Steven Spielberg, yes, and maybe a few others.

A similar thing happens with the soundtrack. In animated films, the voices are recorded before the creation of the images. That’s been true since sound was innovated in the late 1920s. Pre-recording means that images of moving lips can be matched to the dialogue far more precisely than if actors watched finished images and tried to speak at exactly the right time to mesh with their characters’ mouths. The lengthy fiddling possible with ADR isn’t an option. Most stars are used to recording their entire performances within a few days, picking up their fees, and moving on to more time-consuming live-action shooting.

[Added December 11: Jason Mittell, who teaches at Middlebury College, has pointed out to me other factors closely related to the thorough storyboarding of animated films and to the pre-recording of dialogue.

Live-action projects often go into the shooting phase with the script still being tinkered with. The main writers are long gone, script doctors have taken over, and stars may request, nay demand, changes in their dialogue. But for animated films the script, like the editing, is in finished form at the move from preproduction to production.

Jason also points out makers of animated films very carefully distinguish the characters by distinctive dialogue and voices. In contrast, do planners of live-action films think much about the combination of vocal tones that the actors will bring to the project? It’s indicative of the difference, I think, that the Annies have a category for best vocal performance and the Oscars don’t. Ian McKellen has been nominated for an Annie in that category for his contribution of the Toad’s dialogue in Flushed Away–completely tailored to the role and totally unrecognizable from his usual voice.

As Jason concludes, “Live-action filmmakers should try to emulate Pixar’s pre-production strategies to raise the quality bar.”]

In The Way Hollywood Tells It and Film Art, David has briefly discussed the modern vogue for muted tones, usually brown and blue, of many modern features. (Remember what a big deal it was when Dick Tracy used bright, comic-book colors in its sets?) The old vibrant tones of the Technicolor days are largely absent, at least from dramas and thriller. Not so in animated films. Most animated films are full of bright colors. (Some tales, like Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride and Happy Feet, call for the elimination of color, but they’re exceptional.) Think of Monsters, Inc. and, say, any David Fincher film, like Se7en. (Yes, Se7en is dark in its subject matter, but I’ve illustrated the two early getting-ready-for-work scenes in each film, before the nastiness starts in Fincher’s film.) For those of us who like some variety in our movie-going, an animated film can be visually pleasing in ways that few other films are.

Makers of animated films aren’t obligated to drag in sex scenes or to undress the lead actress. Maybe such scenes in live-action films really do draw in some viewers, but they can be hokey and definitely slow down the action. (Remember Ben Affleck rubbing animal crackers on Liv Tyler’s bare midriff in Armageddon?) Animated films tend to have romances and sometimes even mildly raunchy innuendo, but it doesn’t slow down the plot. The romances in Flushed Away and Cars are very much like the ones in Hollywood comedies of the 1930 and 1940s, flowing along with the narrative in a more logical way.

live-action films really do draw in some viewers, but they can be hokey and definitely slow down the action. (Remember Ben Affleck rubbing animal crackers on Liv Tyler’s bare midriff in Armageddon?) Animated films tend to have romances and sometimes even mildly raunchy innuendo, but it doesn’t slow down the plot. The romances in Flushed Away and Cars are very much like the ones in Hollywood comedies of the 1930 and 1940s, flowing along with the narrative in a more logical way.

Animated films don’t have to be tailored to the egos and ambitions of their stars to the degree that many live-action features are. Indeed, often stars bring film projects to studios or produce their own films. The growing number of stars providing voices for mice and penguins and spiders don’t have that sort of investment, emotional or financial.

Some of the best directors working today are in animation. Pixar’s John Lasseter hasn’t let us down in any of his Pixar films, whether he personally directs them or supervises others. Nick Park’s shorts and features, especially Creature Comforts and The Wrong Trousers, are the works of a genius, and other director/animators at Aardman aren’t bad either. Then there’s Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, to mention only one). There aren’t many live-action directors working in commercial cinema today with such track records.

Despite all this, studio executives and commentators continue to debate whether there are now too many CGI films coming out. Indeed, the November 24 issue of Screen International says, “Much has been made this year of the seeming over-saturation of studios’computer-generated titles, with critics and analysts pointing to growing movie-goer apathy.” Of course to most people don’t notice any difference between CGI 3D films and those made with claymation (Parks) or puppets (Burton), so SI’s article talks about the successes and failures among the family-friendly animated films of 2006, including 2D Curious George.

This debate over a possible saturation of the market with CGI films seems bizarre. As a proportion among the total number of films made, CGI’s box-office successes seem fairly high compared to live-action films. Yet one doesn’t see execs and pundits mulling over whether audiences are tired of those.

Certainly success or failure isn’t based on quality. Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-rabbit, last year’s winner of the Oscar as Best Animated Feature, was a commercial disappointment (in the U.S., not elsewhere). Monster House got a lot of highly favorable reviews, but similarly had a mediocre reception by ticket-buyers.

This week the nominations for the Annie Awards, given out by the International Animated Film Society, were announced. The Best Animated Feature competition is among Cars, Happy Feet, Monster House, Open Season, and Over the Hedge. But in the “what’s the logic behind that?!” world of awards, Cars and Flushed Away got the highest number of individual nominations, nine each, followed by Over the Hedge with eight.

I’ll confess right now that I’ve only seen three CGI-animated films this year, because, as I say, I’m not an animation specialist. I go to animated films for specific reasons. One, Cars, is a Pixar film. Two, Flushed Away, is an Aardman film. Three, Happy Feet, is directed by George (Road Warrior) Miller.

On the other hand, Over the Hedge was advertised as being “from the creators of Shrek.” Shrek was an entertaining film, but I think it has been overrated. Besides, a check through the main credits of Over the Hedge reveals no one who had worked on Shrek. “Creators” here must mean Dreamworks. That, by itself, is not enough to draw me in.

Of the three I’ve seen, I would rate Cars the best, Flushed Away a not too distant second, and Happy Feet a distinct third. (More about Happy Feet later.) So how come Flushed Away didn’t get nominated for Best Animated Feature?

A cynic might point out that, on a list of the ten highest-grossing animated features of 2006, by year’s end the five nominees will end up among the top six. Ice Age: The Meltdown, currently at number two, received four nominations, but not one for best feature. Flushed Away is at number nine and likely to remain so. I’m sure that’s not the only factor, but as with many other awards nominations, hits tend to maintain a high profile through the year. I suspect that Cars will end up becoming the fourth Pixar film to win the Annie for Best Animated Feature during the seven-year period since Toy Story, the first totally CGI feature, won.

Quality apart, though, why do industry people doubt the wide appeal of CGI animation? Why do they think rising above an indeterminate number of such features per year causes CGI-fatigue among moviegoers? They certainly go on releasing far more live-action films than could possibly all become hits.

As I suggested in my earlier entry on Flushed Away, most of companies releasing animated films don’t know how to market them very well. Let me offer a couple of suggestions as to why everyone but Pixar often seems so clueless.

First, although animated features seem like the ideal family-friendly audience, they’re quite different from the family-friendly live-action film. Every studio wants films that appeal “to all ages” (i.e., to everyone but small kids), preferably with a PG-13 rating. Think Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, and Titanic, in ascending order the three top international grossers of all time (in unadjusted dollars).

With most animated features, however, there’s a big gap in that family audience: teenagers. Animated films (“cartoons”) are still perceived as largely for children. Sure, savvy filmmakers like the people at Pixar and Aardman are putting more sophisticated references and jokes into their films, things that are more entertaining to adults than to children. The assumption is that parents who take their kids to the movies might be more likely to pick a film if they think they’ll have something to engage their attention, as opposed to sitting tolerantly waiting for the thing to be over.

This, by the way, is another reason why some animated films are among the best products of the mainstream film industry these days. They’ve got a wit and visual sophistication that is sorely lacking in many live-action films. (That’s certainly not true of all of them. I thought Madagascar and the first Ice Age had simple plots that would be engaging mainly to small children.)

So the grown-up humor may please the adults, many of whom, like me, go to them without children in tow. Kids, of course, will watch just about anything animated that’s put in front of them. But suppose a bunch of high-school kids on a Saturday are trying to decide which film to attend. Would any of them nominate Cars or Happy Feet? Maybe I’m behind the times, but I find it hard to imagine. Most teen-agers among themselves, after all, would do anything to avoid seeming not to be grown-up, and watching cartoons is just too childish. (Even the CGI film most obviously aimed at teens, Final Fantasy, was a flop.)

This is not to say that teen-agers don’t see or enjoy Cars and Happy Feet, but I’m guessing they probably go with their families on holidays or see them at home on DVD.

The second big problem that stymies the industry when it comes to promoting animated features is that they usually can’t be branded by director or star, the way “regular” films are. Pixar, as usual, is the exception. John Lassetter is sort of the Steven Spielberg of animation—one of the few directors with wide popular name-recognition. Pixar quickly became a brand in the world of animation, even more than Disney was at that point. Now they’re under the same roof. But Dreamworks really isn’t a high-profile brand, and the newer Sony Pictures Animation certainly isn’t. Their films succeed and become franchises in a hit or miss way. “From the people who brought you Shrek” is a feeble way of branding a film. Mostly I think distributors market animated films to kids and hope the adults will be there, too. Maybe they don’t even think about the teenage audience, considering it a lost cause.

More and more famous actors are doing voices for animated films, but that’s far from the same thing as appearing in a live-action one. Hugh Jackman was a big selling point for the X-Men movies, but who would go to see Flushed Away just because he voices the lead character?

So what can the studios do to integrate CGI and other types of animated films into their flow of regular releases, comparable to live-action films?

One solution is obvious: Make the characters into stars. Disney created the prototype with Mickey Mouse. Buzz Lightyear and Woody would be stars with or without Tim Allen’s and Tom Hanks’s voices. Shrek is a star. Wallace and Gromit are beloved stars outside the U.S. It might have occurred to Paramount to lead up to its release of The Curse of the Were-rabbit by circulating a package of the three earlier shorts, in order to familiarize Americans with the duo. (That was done in European theaters years ago.) Roger Ebert’s review of the feature opined that “Wallace and Gromit are arguably the two most delightful characters in the history of animation.” A pity the American public have not yet been given much of a chance to discover that.

Another possibility is doing what Hollywood is slowly doing for live-action films: Publicize award nominations other than the Oscars. More awards ceremonies are being broadcast on TV as time goes by, and audiences seemingly love these contests. Why not tout an animated film’s garnering of Annie nominations?

Of course companies use Oscar nominations in their ads, but under Academy rules, only three animated features can be nominated in any year unless sixteen or more such features are released that year. Then the number of nominations jumps to five, as has happened only once so far–in 2002, for the 2021 releases. It may become more common, as animated films become more common.

One might object that the general public doesn’t know or care about the Annies. But it’s a vicious circle. They don’t know about them because the industry doesn’t bother to publicize them, and the industry doesn’t publicize them … well, you can see where this is going. If the industry promoted the Annies as signs of quality animation, the public might know and possibly care about them. They’ve learned to be interested in the Golden Globes, because those have been increasingly covered by the infotainment section of the media. And the infotainment industry largely covers the “news” that the industry’s publicity departments want it to (star scandals excepted).

And then there’s the Internet, where fans often do a better job (and for free) of publicizing films than their distributors do. Case in point, Lyz’s WallaceAndGromit.net. I can’t get into online publicity here, or this entry would balloon out of control. Still, there seems an obvious link between people who spend time on the internet and those who are interested in CGI animation.

Epilogue: On Happy Feet (Spoilers!)

I went to Happy Feet with high expectations, based both on reviews and on my liking for previous George Miller films like The Road Warrior and Babe: Pig in the City. I saw it under ideal conditions, in an Imax auditorium.

I enjoyed it but was somewhat disappointed. For one thing, much of the time the images seemed to be going by in fast-forward. The swishing movements of figures combined with rapid-fire editing occupied a lot of screen time. The story has its penguin hero, Mumble, shunned by his vast flock as having dancing rather than the conventional singing talents. The plot hinges on Mumble’s two goals: to win the love of talented singer Gloria and to gain respect by finding out why the supply of fish has dwindled recently.

Both of these goals are, however, put on hold for great stretches of the film’s middle. Miller seems so caught up in Mumble’s escape from a seal or his encounters with a nearby troop of Puerto Rican-accented penguin hipsters that the plot gets sidetracked. Once the search for the “aliens” who are decimating the fish supply reveals that they are humans on huge ships, the scenes that resolve that plot-line seem perfunctory.

The animation itself is dazzling, the vocal talent excellent, the ecological message unobjectionable, and the wild mix of musical styles amusing. I just wish I hadn’t spent much of the movie wondering where it was all heading.

*Kristin Thompson, “Implications of the Cel Animation Technique,” in The Cinematic Apparatus, eds., Stephen Heath and Teresa de Lauretis. St. Martin’s Press, 1980, pp. 106-120.

Film educators no longer criminals

Kristin here—

The rise of digital media has made the unauthorized copying of intellectual property easy. That, of course, drives the producers of that material crazy. We all know that the entertainment industry is said to be losing billions of dollars world wide from various sorts of piracy, from the sale of bootleg DVDs in southeast Asia to the downloading of sounds and images from the internet.

Much of this activity is undoubtedly illegal and undoubtedly violates entertainment producers’ copyright. But in trying to stem the tide of piracy, the industry hasn’t just gone after the wrongdoers. It has encouraged Congress to make more and more uses of intellectual property illegal, in the process riding roughshod over the Fair Use provision in the United States Code. A brilliant way to stamp out crime: make more activities into crimes and hence have more criminals to pursue. You’d think they have enough problems just going after the real pirates. But people like educators and scholars who try to use clips from movies in their classes or frame enlargements as illustrations in articles and books were thrown into the general mix of copyright violators.

That happened in 1998, when the Digital Millennium Copyright Act was signed into law by Bill Clinton. It essentially made any copying of visual or sonic material that involved breaking a digital encryption code illegal. All sorts of means exist to break these codes. Programs exist to grab frames from movies on DVD. Fans can post images on their websites (thereby offering the studios free publicity). Professors can import frames into their Powerpoint-based lectures. Scholars can illustrate their articles and books with reasonably high-quality images. The devising of such programs and the activities just mentioned were all illegal under the DMCA.

(For the Copyright Office’s own summary of the act, go here; for the Wikipedia summary, here.)

In the 1970s, when David and I were setting out to write Film Art and our other early books, we faced a similar issue, though at that time the copyright law concerning the use of frame enlargements was far less clear. Film studies was still a young field. Most publications on cinema, whether textbook or scholarly article, used studio-generated publicity photos as illustrations. We reasoned that such images did not reflect what really appeared in the film, since they were still photos taken on the set, often with different poses, lighting, and camera position. They were useless for the sort of close analysis we wanted to do.

Film Art thus became the first introductory film text to use frame enlargements extensively. Our publishers accepted the idea that such illustrations fell under fair use. Other publishers, however, were nervous about the idea. Did reproducing frames violate copyright? Editors weren’t always willing to risk finding out the hard way. Some authors paid large “permissions” fees to reproduce frames. Others gave up and settled for production stills.

Around 1990 I was asked by the Society for Cinema Studies (now the Society for Film and Media Studies) to chair a committee to investigate the validity of Fair Use as applied to film images. The result was the “Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Society For Cinema Studies, ’Fair Usage Publication of Film Stills’” (1993). This report established that fair use most probably applied to film frames, and educators and scholars were not violating copyright when they used slides or illustrations photographed from the original film. Several presses changed their policies as a result of the report, no longer requiring their authors to obtain unnecessary permissions for frame reproductions. The use of frame enlargements in scholarly publications spread, and film studies benefited as more authentic and useful images were employed by scholars.

Happy ending, right? Certainly the studios never sued over frame enlargements, before or after the report. In fact, relatively few authors were using frame enlargements. It took special equipment to photograph such frames: expensive camera attachments, color-balanced light sources, and the expertise to use both. Those of us publishing extensively illustrated books on Ozu or Eisenstein weren’t exactly a concern to the film industry. In fact, studio executives probably didn’t know that we existed and wouldn’t care if they had.

Then along came DVDs, which made frame grabbing easy. Scholars who had never bothered to get the special equipment or learn how to photograph film frames suddenly could quickly pull images for use in their publications. The reliance on publicity stills declined further. Frames were everywhere, all presumably covered by the same Fair Use law that 1993 report had opined applied to the reproduction of film frames. Legitimate users of frames had to get around the encryption codes, but like millions of DVD users around the world, most of them were savvy enough to do so.

I’m sure that the DMCA was not envisioned as applying to film scholars seizing frames for their publications or professors using visual examples in classes. Still, the provisions of the act were so broad that suddenly scholars and educators were criminalized for doing what they needed to do to foster knowledge: show clips from DVDs in lectures and use frame enlargements from DVDs in books and articles. They had to get around the studios’ codes that prevented piracy. Many of us went ahead and broke the codes and published DVD-derived illustrations in our books or compiled discs containing clips from films to show in lectures. The studios didn’t seem to care, since to the best of my knowledge no teacher or scholar had ever been prosecuted for violating the DMCA.

Finally the recognition of this ludicrous state of affairs has been partially remedied. The Librarian of Congress, James Billington, himself a fine scholar in the area of Russian and Soviet studies, recommended a series of exemptions to the DMCA. The first one relates to film: “Audiovisual works included in the educational library of a college or university’s film or media studies department, when circumvention is accomplished for the purpose of making compilations of portions of those works for educational use in the classroom by media studies or film professors.” (“Circumvention” is described as “circumvention of technical measures that control access to copyrighted works.”)

This is specific to classroom situations and only applies to DVDs owned by an educational institution. What if the teacher copies clips from his/her own DVDs to use in class? (All too frequent, given the tight budgets of universities and high schools.) Nevertheless, the general implication of this exemption is that the same Fair Use principle that applied to film clips and frames duplicated from analogue copies of films (i.e., 35mm and 16mm prints) should apply even if the educator or scholar is breaking a code to do that duplication. If clips are OK, why wouldn’t single frames be?

The exemption is a small step in chipping away at the monolithic laws protecting intellectual property that the studios are determined to put in place even when it goes against their own interests. Lectures, articles, and books do not damage the studios’ ability to exploit their own films commercially (one of requirements for Fair Use to apply). Quite the contrary. Film professors show clips and still images that publicize films and possibly inspire students to rent or buy DVDs. Articles and books similarly publicize films, even though their contribution to the attention paid to any given title is minuscule.

Making an exception in the DMCA as originally passed to allow for the educational/scholarly use of digital film images would never have occurred to the studios as they lobbied for this sweeping legislation. Few movers and shakers within the industry know there is such a thing as film scholarship, much less understand what we do. Fortunately people like Billington understand. His recommended exemptions went into force November 27.

So, film educator, the next time you prepare a lecture involving clips, you don’t need to pull the curtains, lock the doors, and glance nervously over your shoulder as you copy a tracking shot from Grand Illusion and another from The Magnificent Ambersons. You are no longer a thief.