Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Reeling and dealing: Rescuing movies, by hook or by crook

DB here:

There have long been film collectors, and they’re central to film preservation. Some archives, notably the Cinémathèque Française and George Eastman House, were built on the private hoardings of passionate cinephiles. Filmmaking companies, both American and overseas, had little concern for saving their films until home video showed that there was perpetual life in their libraries. By then, many classics had been dumped, burned, or left to rot, and in many cases collectors came to the rescue.

In America, private collecting really took off after World War II. What happened afterward is too little known among cinephiles, but it represents an important part of film culture. A new book fills in a lot of the detail, and in a very entertaining way. It’s a big contribution to our knowledge of the afterlife of the movies.

16 + 35 = $$$$

In the late 1940s, 16mm versions of theatrical releases became widely available. For a while the studios contemplated replacing 3 5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

Many of those firms dealt in foreign titles, which weren’t as attractive to most collectors—who were in love with Gollywood. For them, the floodgates had already opened when the studios licensed their pre-1948 product to television. The 1950s and 1960s were very unlike the multi-channel 24/7 TV environment of today. The networks didn’t fill the broadcast day, and many independent stations tried to support themselves apart from the nets. So everybody needed what we now call content. Our colleague Eric Hoyt has traced in detail how C & C Movietime and other entrepreneurs bought rights to classics and not-so-classics and packaged them in 16mm bundles for local TV stations. Those prints were shown throughout the day and night, interspersed with commercials cut in by staff like Barry C. Allen.

In the 1950s hundreds of copies of film classics were abroad in the land. But many of these TV prints wound up discarded and scavenged by guys (almost always guys) who wanted to show them at home. Aficionados started building their own libraries.

Collecting 35 was tougher, but it could be done. Older films were stored in labs and depots. They might wind up in Dumpsters or be smuggled out by enterprising employees. Of course showing 35 was more difficult, but it wasn’t impossible to get 35 projectors fairly cheap, and if the hobbyist was willing to make major home renovations, he (again, almost always a he) could set up a personal screening room. Some went with curtains, masking, auditorium seats, popcorn machines, and other amenities. The idea of “home theatres” for ordinary folks has its origin here.

Acquiring 16mm was gray-market but ultimately not very criminal. Because of the First Sale Doctrine, a collector was not in violation if he bought a 16 print that had already been sold (to a TV station). If I buy the new Carl Hiaasen novel Razor Girl, I can sell my copy to you because someone sold it to me. What got 16mm dealers in real trouble was their zeal to copy prints. If they got access to a nice 35, they might make a 16 reduction; or if they had a decent 16, they might pull dupes. These were definitely illegal, as if I were to scan Razor Girl and sell you a pdf.

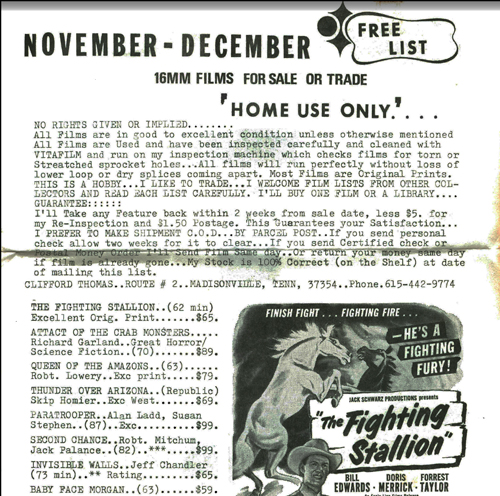

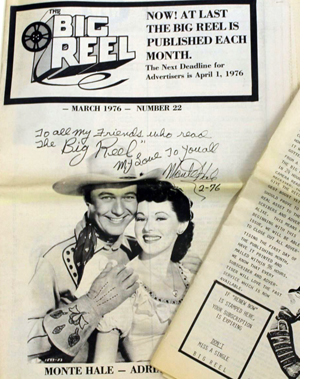

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

With some exceptions, 35 prints weren’t originally sold, only rented, and so possession of one suggested, to suspicious minds, big-time theft. Actually, most collectors’ prints had been junked, and you can argue that once something is tossed out, it’s the American Way to scavenge and recycle it.

Beyond the domestic collectors’ market, there was money to be made with 35 prints. American films didn’t circulate much in Cuba, South Africa, parts of Asia, and Eastern Europe, so there was an international demand for bootleg copies, and some dealers were happy to meet it. I lost out on a collection of Hong Kong films that was bought by an Indian dealer who intended to circulate them at home. I always think of that episode when I see the almost inevitable kung-fu fight in an Indian action movie.

The sale of 35 boomed because of another factor. With the rise of the blockbuster mentality in 1970s-1980s Hollywood, the nation was awash in theatrical prints. Then as now, a film might open on thousands of multiplex screens, play a few weeks, and be done. The studio would keep a few of those prints, but the rest would have to be disposed of. Salvage companies were contracted to destroy them, but—human nature being what it is—often some copies slipped out and into eager hands.

Films stored in laboratories or warehouses had a habit of disappearing as well, and prints shipped to theatres might be waylaid. I remember booking Blue Velvet and learning that the copy had disappeared in transit. The fact that prints were labeled with their titles printed in large letters probably didn’t help keep them safe. I was always startled to see the casual ways in which prints were handled. On Thursday midnights I’d leave a screening at one local theatre and see, neatly lined up on the sidewalk, shipping cases bearing the titles of films that had played there in recent weeks, waiting for a UPS pickup the next morning. After a theatrical run, exhibitors cared as little for prints as producers and distributors did.

Many collectors favored older titles, but others were as susceptible to blockbuster mania as general audiences. Star Wars, Jaws, The Godfather, and all the other top hits became as sought-after as Casablanca and Snow White. Collectors still boast of having multitrack, IB-Tech copies of 1970s and 1980s franchise pictures.

Enter the Feds

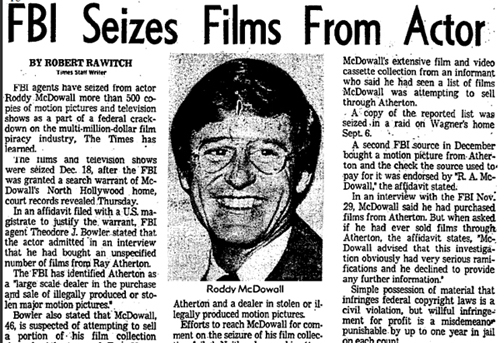

Los Angeles Times (17 January 1975), B1.

I’ve moved from describing the collectors’ market to describing the dealers’ market. That’s because they were almost one and the same. Collectors needed dealers to help find the rarities they yearned for; collectors started to deal to support their habit; and dealers, whether collectors or not, found that they could make money acquiring and selling movies. Demand and supply, in solid capitalist fashion, created an underworld traffic in prints.

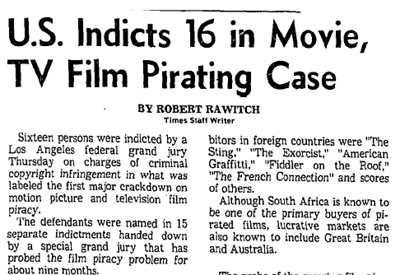

The studios didn’t take this lying down. With the aid of the FBI, they pursued collectors, pressuring them to snitch on their suppliers and fellow addicts. Former child star Roddy McDowall, an avid collector, was the most visible target of these maneuvers. I well remember the chill that passed through the collector community at the news of the Feds’ raid on his house, which turned up hundreds of prints and videos. McDowall, who could probably have won a legal case, gave up many of his contacts. Charges against him were dismissed, but the U.S. Attorney pursuing the case warned that the activities of film collectors (said to number 65,000) “could constitute serious violations of both state and federal law.”

Most collectors flew under the radar, though. Although McDowall’s collection was mostly 16mm, the studios turned a blind eye to 16mm collectors. Famously, William K. Everson helped studios uncover lost films (e.g., obscure Fords and Stroheims) and as payment received 16mm copies of his discoveries. Collectors like Bill, who accumulated several thousand prints, shared their libraries with archives and film schools; at NYU, Bill taught from his collection for many years.

Home video didn’t destroy this underworld right away. The first video systems were of such poor quality that they couldn’t compete with 16mm projection, let alone 35. However, as formats improved in the 1990s, more and more collectors turned to video. Why thread up a battered copy of an MGM musical when a pretty nice DVD could just be popped into your player? With the arrival of Blu-ray, which can look very impressive projected in theatrical conditions, 35 began to be seen as more and more a retro hobby. And your average hobbyist was discovering that he (still almost certainly a he) was aging. Or dying.

The studios mostly lost interest in film-based piracy, once video presented a threat on a much bigger scale. Duplicating VHS and laserdisc, always imperfect, was followed by the cloning of perfect copies of DVDs. Now, of course, the main arena is the Net, where film piracy via BitTorrent has exploded to a level the old-timers couldn’t imagine. Back in the 60s, there were very few film collectors. Now, thanks to digital convergence and massive hard drives, everybody is a film collector—not only he’s.

Boom and busts

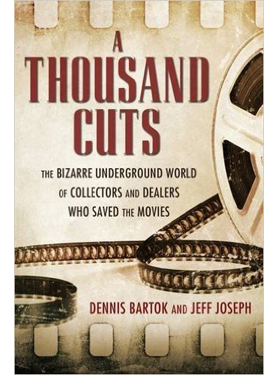

This is the world chronicled, with affection, humor, gossipy detail, and a pang of melancholy, in Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph’s A Thousand Cuts. Dennis has been head of programming for the American Cinematheque, and he currently heads the distribution company Cinelicious Pics. Jeff was one of the top film dealers in the country; at its peak, his company SabuCat sold about 1,000 prints per month. In the wake of the McDowall bust, Jeff became the only film dealer to serve time for selling prints. Jeff is now a distinguished archivist, conserving 3-D prints and, most recently, rare Laurel and Hardy movies.

The book lives up to its subtitle: The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies. Through interviews, documents, and vast knowledge of the world of film dealing, Bartok and Joseph have given us an invaluable survey of a wondrous land. It’s as gripping, and sometimes as hallucinatory, as any Forties B noir.

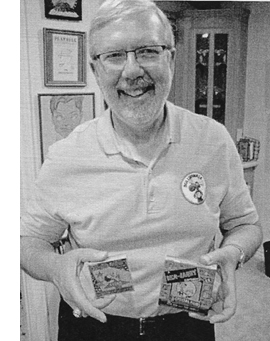

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Once we leave behind the celebrities, things take a more exotic turn. There’s Evan H. Foreman, the first collector targeted by the studios, a tough customer who fought for the right to sell prints and was called to testify before a Senate committee. There’s Ken Kramer, proprietor of The Clip Joint, a Burbank archive and screening facility decorated with posters and Christmas lights. There’s Tony Turano, who claimed for years that he was the baby in the bulrushes in The Ten Commandments. Tony kept his apartment heavily curtained, the better to preserve Claudette Colbert’s headdress and robe from Cleopatra (1934). Paul Rayton, projectionist extraordinaire, stores the cans for his rare Oklahoma! print in the back seat of his car. Not the film–it went vinegar long ago. Just the cans.

There’s Al Beardsley, uniformly considered untrustworthy, perhaps because he simply picked up a 70mm print of Lawrence of Arabia posing as a delivery courier and immediately sold it to a collector. Beardsley gave up film dealing for sports memorabilia, and became a participant in the O. J. Simpson throwdown in Vegas. As Beardsley recalls his encounter with one Thomas Riccio, who had set up the O. J. meet: “I had a drink and, I believe, a hamburger that Riccio paid for. He feeds you before he screws you.” O. J. was more direct: “Motherfucker, you think you can steal my shit and sell it?” Yes, firearms were involved.

This is as wild and crazy as any nerd culture can be. Like collectors of comic books and LPs, film mavens are clannish and wily, generous and secretive, boastful and yet somewhat innocent. These guys can’t be considered Geek Chic; they retain an unselfconscious love for what moved them in their youth. They live in the Adolescent Window, as we all do, but they don’t pretend to have become hip. And they run risks that other collectors don’t. A book or record collector runs no risk of arrest. But should a film collector offer a rarity to an archive? Will the studio claim it and bury it? Will the law get involved? Paranoia strikes deep, and justifiably.

Some of the tales are painfully funny, some just painful. This is the sort of book that contains sentences like:

The two were briefly partners as film dealers in the early 1970s, until Ken’s then-wife Lauren left him to marry Jeff, shortly after they were discovered having an affair at the 3rd Annual Witchcraft and Sorcery Convention.

Turano, wheelchair bound, had a habit of bursting into showtunes at the top of his voice. Tom Dunnahoo, of Thunderbird films, “routinely passed out on the floor of his film lab drunk on Drambuie.” A dealer takes pride in the fact that at his trial, the expert on the stand couldn’t tell his dupe of Paper Moon from the original. Another bit of dialogue:

“You remember I had a beet-red print of Giant? Well, Louie Federici ran it and borrowed a beautiful IB print of Giant. Afterward he sent it back to Warners, and you know what they got? A beet red print,” he says, face lighting up.

“You swapped it out?” Jeff asks.

“I did. And later I traded it to you for Singin’ in the Rain. How about that, huh?”

Nearly every page of my copy boasts my penciled ! in the margin.

Saving the movies

Jeff Joseph and Dennis Bartok, Cinecon 2016.

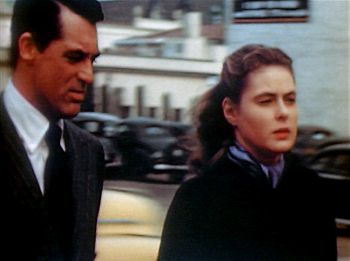

The book stresses that collectors functioned as preservationists. Just as in the early days of archives, they have saved films major and minor from destruction. Just last week, we learned that a collection of 9.5mm has added more footage to a partially surviving Ozu film, A Straightforward Boy. Famously, missing King Kong footage was discovered by a collector. . . and given, not sold, back to the studio. Tony Turano found a missing Fred Astaire number from Second Chorus in Hermes Pan’s closet. Jeff Joseph preserved color behind-the-scenes footage of Animal Crackers and found remarkable home-movie Kodachrome footage of Hitchcock, Bergman, and Grant out for a walk during the shooting of Notorious (surmounting today’s entry). Mike Hyatt has devoted his life to cleaning up The Day of the Triffids. Using a jeweler’s loupe and a needle, across many years, he flicked over 20,000 bits of dirt out of the camera negative.

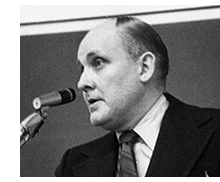

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Most of the stories in the book come from the West Coast, as you’d expect. Other regions have their own lore and characters. The East Coast was a lively scene, centering on Manhattan’s Theodore Huff Film Society (duly noted in A Thousand Cuts) and Bill Everson’s screenings at the New School and elsewhere. Scorsese is, of course, a famous collector. Until this last year hard-core fans of old films gathered at Syracuse’s fine Cinefest. The Midwest had its own center of film trade, Festival Films in Minneapolis, now a source of public-domain items. The screening-and-dealing gathering Cinevent, in Columbus, Ohio, is entering its 49th year.

There were colorful personalities hereabouts too, including a Milwaukee collector with a stupendous array of original Hitchcocks from the 1950s. Another Wisconsin collector, Al Dettlaff, discovered and jealously guarded Edison’s 1910 version of Frankenstein. I met a collector in remote Minnesota who had converted his garage for 35mm screening both indoors and outdoors. He could aim his projectors to shoot out onto the back yard for neighborhood shows (a popular pastime for collectors). During the snowbound winters, he could swivel the machines to shoot through the kitchen to the living room. I asked how his wife felt about sawing holes in the walls. He said: “She’s fine with it. She knows I can get a new wife a hell of a lot easier than an IB Tech of Bambi.”

Dennis and Jeff are to be thanked for recording precious information about a phase of American film culture that has been neglected. They’re continuing the effort with a clip show on 23 September at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre. It will include many items mentioned here, as well as a Bela Lugosi interview from 1931.

The collecting adventure is not quite over. The book profiles passionate younger aficionados, some of whom keep the energy going online. Still, as someone who has relinquished his passion for owning film on film and is happy that archives are taking over the task, I’m afraid it’s evident that the curtain is coming down. Without collectors, who will scavenge all the films not likely to be transferred to digital formats? The book ends with a list of six interviewees who died during writing and publication. And in the podcast below, Jeff glumly notes that studios are still junking prints.

Thanks to Jeff Joseph for illustrations. The Len Maltin picture is by Dennis Bartok. For a fascinating podcast that gives the authors a chance to expand on many aspects of A Thousand Cuts, check The Projection Booth. There’s a shorter streaming interview at KPCC radio.

Typical collector story: How did William K. Everson acquire his K? He told us that the first movie he remembered seeing was by William K. Howard, so Bill borrowed the middle initial. Another: We did our bit. After seeing an ad in The Big Reel for a hand-tinted Méliès print, we alerted Paolo Cherchi Usai, then at Eastman House. It turned out to be one of the lost Méliès titles.

Thanks to Haden Guest for tipping me to the Ozu rediscovery. I talk about how piracy created a classic here. For more on 16mm collecting and showing, go here and here. In this entry we cover Joe Dante’s remarkable visit to Madison and his presentation of The Movie Orgy, one result of his insatiable collecting appetites.

P.S. 14 September 2016: I should have mentioned another collector committed to preserving 3D films. Since 1980 Bob Furmanek has been building a large 3D archive, a project that is still ongoing. The history of his work is traced on his site.

P.S. 15 September 2016: Thanks to Christoph Michel for correcting a howler that out of shame I shall not name.

Animal Crackers, Multicolor on-set record (1930). Courtesy Jeff Joseph.

How he (mostly) got away with it: Matthew H. Bernstein on Preston Sturges

DB here:

Matthew H. Bernstein is a long-time friend and a superb scholar. His biography of Walter Wanger has become a classic of Hollywood business history, and his many books and articles have refined our sense of American cinema. When we learned of his research into Sturges (a favorite of this blog), we were happy to propose that he do a guest entry. Here’s the lively, trailblazing result.

How should films portray sex and marriage? Hollywood’s Production Code, established in 1930, set forth some definite ideas.

Sex

The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing. . . .

Scenes of Passion

They should not be introduced when not essential to the plot.

Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown . . .

Seduction or Rape

They should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot, and even then never shown by explicit method.

They are never the proper subject for comedy.

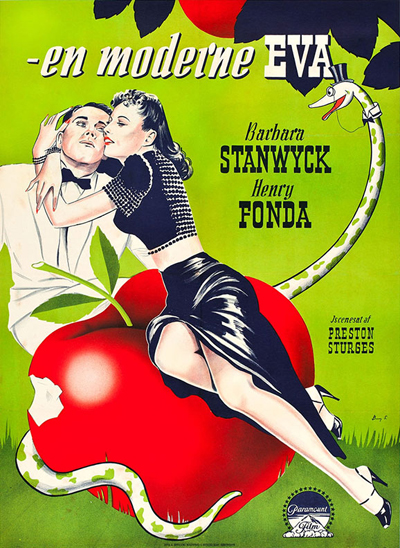

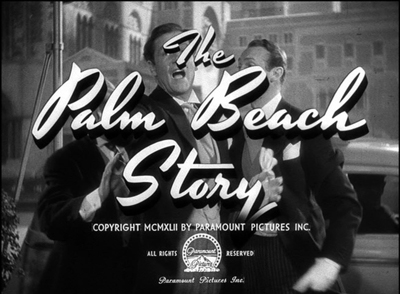

Those of us who savor Preston Sturges’s great romantic comedies of the 1940s—The Lady Eve (1940), The Palm Beach Story (1942) and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944)—admire them in part for their violation of just about all these tenets. They are full of “suggestive postures” like the lengthy chaise longue scene in The Lady Eve. Their central topic is often the seduction of men by women (The Lady Eve, The Palm Beach Story and arguably Miracle). References to extra-marital sex, contemplated or accomplished, abound. And all three films ridicule “the sanctity of the institution of marriage” into the ground. Film critic Elliot Rubinstein once observed, “If Sturges’s scenarios don’t quite invade the province of the flatly censorable, they surely assault the border outposts, and some of the lines escalate the assault into bombardment.”

The Production Code Administration, on paper and in practice, was particularly obsessed with regulating the depiction of female sexuality on screen. Yet Sturges’ attacks on conventional morality are launched by heroines: con artist/card sharp Jean/Eve (Barbara Stanwyck) in The Lady Eve, the hard-headed Gerry Jeffers (Claudette Colbert) in The Palm Beach Story and the naïve man-bait Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. They are all variants of what Kathleen Rowe has called the “unruly woman,” characters who create “disorder by dominating, or trying to dominate, men,” and being “unable or unwilling” to stay in a woman’s traditional place. Mary Astor’s much-married Princess Centimilia/Maude in The Palm Beach Story deserves an honorable mention here too.

True, by each film’s conclusion, the Sturges heroine agrees to get or stay married. She fulfills the conventions of romantic comedy and the stipulations of the PCA. Yet in each film the path to a proper end looks so much like a roller-coaster ride that the significance and sanctity of marriage come to seem ridiculous.

How did Sturges get away with so much? A look behind the scenes at the negotiations around The Lady Eve can help us understand his strategies. It also shows that the Code was more flexible and fallible than we often realize.

Convolutions in the Code

Sturges had one advantage at the outset. He worked in a genre that was already testing the limits of the Code. Granted, the PCA in 1934 aimed to regulate film content in every genre. None, however, flaunted, even parodied, the strictures of the Code more thoroughly than screwball comedy did. Rubinstein puts it well: “The very style of screwball, the complexity and inventiveness and wit of its detours around certain facts of certain lives, the force of its attack on the very pieties it is pledged to sustain, cannot be explained without recognition of the censors. Screwball comedy is censored comedy.“

By the end of the 1930s, filmmakers were pushing hard against censorship. Romantic comedies were growing more risqué by the month, as shown by 1940 releases like My Little Chickadee, The Philadelphia Story, The Road to Singapore, Too Many Husbands, The Primrose Path, Strange Cargo, and most especially, This Thing Called Love. A sort of arms race took place, and Sturges, emerging as a writer-director in 1940, benefited from this escalation.

Just as important is a fact that many fans of Hollywood still don’t realize. We like to think that daring filmmakers were charging boldly against an iron wall, with chief censor Joseph Breen and his associates setting forth implacable demands. But the administration of the Code was not a mechanical, totalitarian affair. It was most often a matter of negotiation.

Releasing Hollywood’s product, even risqué films, benefited all parties involved. If the Code were enforced with absolute rigidity, the industry would suffer. Some films would have to be abandoned. Then urban audiences would have found the safely released product pallid, and critics would have complained about bland output. Then as now, edginess sold, and at least some audiences were eager for it.

Accordingly, Breen and co. recognized that the Code could not be applied ruthlessly. Indeed, historians Lea Jacobs, Richard Maltby and Ruth Vasey have shown that the PCA, like its forerunner the Studio Relations Committee, often helped filmmakers find ways around the most stringent policy demands. Through a give-and-take, censors and filmmakers could settle on scenes and lines of dialogue that could avoid public outcry. No one flaunted and taunted the PCA as well as Sturges, yet Breen and co. often helped him find ways of rendering suggestive situations without baldly transgressing the Code.

One typical filmmaker/PCA tactic that favored Sturges was an appeal to ambiguity. Far from being inflexible, the staff recognized that not every viewer picked up on a lewd line or suggestive situation. Some viewers would find no innuendo in a sexually-charged scene. (The 1940s critic Parker Tyler referred to this as “the Morality of the Single Instance.”) For example, in The Lady Eve, there’s a fade-out from Charles’s and Jean’s passionate embrace in the bow of the ship at night to the fade in of the ship’s prow slicing through the ocean the next morning.

That passage would suggest to the naïve viewer that they kissed for a while and went to their cabins separately. After all, in the morning we find Jean getting dressed in her stateroom and talking with her father. Then we see Charles on deck alone, waiting for Jean.

But the sophisticated viewer would understand that the earlier fade-out indicated what Joseph Breen routinely called “a sex affair.” (The ocean spray on the fade-in could be seen as a very subtle extra touch.) Crucially, Jean’s later statement to Hopsy after she is unmasked as a cardsharp sustains both readings. “I’m glad you got the picture this morning instead of last night, if that means anything to you . . . it should.” When self-regulation was well-calibrated—and this was a moment-to- moment, scene-by-sceene, film-by-film achievement—there was wiggle-room that would let innocent viewers remain innocent while letting sophisticated viewers feel sophisticated.

Apart from the increasing eroticism in screwball comedy and the willingness of the PCA to work with filmmakers to allow double layers of meaning, Sturges benefited from good timing. During this period, Breen grew more permissive in his application of the Code. He never explained why, but the late-1930s bombardment of questionable material was probably one cause. Breen was pretty exhausted after seven years of trying to accommodate the filmmakers’ increasingly outré ideas. He was so tired that he temporarily resigned in Spring 1941.

Sturges’ circumvention of the Code also depended on his personal qualities. Clearly he was a persuasive negotiator. The PCA correspondence shows Breen and his successor, Geoffrey Shurlock, rescinding countless directives they initially gave him to eliminate dialogue lines or bits of action. It’s likely that the PCA admired Sturges’ comic gifts and thus gave him greater room to maneuver than other directors enjoyed. (Much the same thing happened when the Studio Relations Committee had given leeway to Ernst Lubitsch prior to 1934.) Sturges also employed a tactic of overkill. In his scripts and in the scenes as finally staged and shot, he created so many potential infractions of the Code that to challenge each one would reduce the film to rubble, or reduce Breen and co. to stress-induced madness.

Still, Sturges played the PCA game. His convoluted plots stuck to the letter of the Code, always finally coming down on the side of pure romance and happy marriage. But they wreaked havoc with its spirit—often with the PCA’s sanction. By the premiere of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Sturges was relentlessly mocking the PCA’s regulations. It’s likely, I think, that the PCA was for the most part in on the joke.

After negotiations, which grew more elaborate with each title, each Sturges romantic comedy received a seal. The films made it through partly because of the PCA’s quixotic mandate, partly because the Code’s requirements had been loosened, and partly because of Sturges’ extraordinary skill in exploiting the Code. These are the crucial reasons Sturges got away with it. Along with his prolific comedic imagination, he was often aided by the very body that was supposed to be censoring him.

Once the Sturges film was released, the PCA staffers could wearily pat themselves on the back for a job well done. Yet critics’ reviews, complaints from state censor boards, and letters of protest from ordinary viewers indicate that the agency often badly misjudged how the films’ moral tone would be received. The PCA’s dual mandate—to try to give filmmakers the maximum freedom to create risqué situations but at the same time to uphold the Code–was a tightrope walk. With Sturges and other filmmakers, the agency lost its balance. Sometimes the PCA didn’t diminish the sexual dimensions enough, and sometimes the agency did not even notice elements that could give offense.

There were signs already, in the reaction to the 1940 burst of sexier films like The Primrose Path and This Thing Called Love. Local informants had asked MPPDA attorney Charles C. Pettijohn, “Doesn’t Mr. Hays have any influence with the producers any more, and has that fellow Breen out there killed himself or has he just been compelled to walk the gangplank?” Unlike the PCA staff, who had worked day by day to tone down an audacious script and had faced the charms of a persuasive filmmaker, local censorship boards reacted solely to a finished Sturges film. They merely saw what was on the screen. Many did not like what they saw.

Up the Amazon for a year

The PCA correspondence concerning The Lady Eve is surprisingly brief. Before the film was completed and a seal was granted, Breen sent only two letters to Luigi Luraschi, Paramount’s liaison on censorship. They strikingly illustrate how cooperative Breen could be when it came to scenes regarding illicit sex.

When he read Sturges’s first complete script of 7 October 1940, Breen had objections to many “questionable lines of dialogue.” Breen warned Sturges and Luraschi against anything “suggestive” in the scene between Muggsy and Lulu as they say their farewells before departing the expedition. In this brief exchange, Mugsy stiffly tells her “So long, Lulu…I’ll send you a post card” as she demurely (looking down) places a lei over his neck. This brief exchange directly undercuts Hopsy’s just-spoken, high-minded farewell to the Professor: “This is the way I’d like to spend all my time…in the company of men like yourselves…in the pursuit of knowledge.”

While it’s difficult to imagine Muggsy as a sexual partner to anyone, the woman’s downcast face and her gift of a lei could be seen to suggest her heartbreak.

Jean’s later, rapid-fire description of Hopsy’s many female admirers in the Main Dining Room of the S.S. Southern Queen originally contained comments about women who were “a little flat in the front” or “a little flat behind. ” These were cut because they were too physiologically specific about the female form. We hardly miss them, as Jean was permitted to deliver plenty of color commentary, as she detailed the women’s futile attempts to attract Hopsy’s attention.

However, Breen wrote the word “in” alongside certain demands he had made for eliminations in his 9 October letter, indicating that Sturges and Luraschi had persuaded him to relent. For example, Breen eventually accepted this exchange from Jean and Charles’s first evening together. Charles has suggested they go dancing:

Jean: Don’t you think we ought to go to bed?

Charles (after a pause): You’re certainly a funny girl for anyone to meet who’s just been up the Amazon for a year.

Jean: (after a pause): Good thing you weren’t up there two years.

Breen’s next letter (21 October) on Sturges’s revised script expressed satisfaction with all the changes made, noting that Jean’s line about heading to bed “will be delivered without any suggestive inference, or reaction.”

In the finished film, there is nothing arch about Stanwyck’s thoughtful, almost parental delivery of the first line, spoken as she looks straight ahead and then looks down to stub out her cigarette before she turns to face Charles. Likewise, her delivery of the second line is wry and mildly mocking yet almost compassionate. Still, the connotation remains that Jean is suggesting they sleep together. Instead, the couple proceeds to Charles’s cabin to meet his snake Emma.

Breen was particularly concerned about other allusive dialogue. At the Pikes’ party, Sir Alfred (Eric Blore) explains to Charles a fictionalized version of Jean’s family history which resulted in the existence of two sisters, one a lady, one a cardsharp. (Sir Alfred will later describe this as “Cecilia or the Coachman’s daughter, a gaslight melodrama.”) Breen insisted that Sir Alfred’s tale include a line indicating that Jean’s mother divorced her elderly earl before taking up with the groom “Handsome Harry” and giving birth to Jean. That way Jean’s birth would not seem illegitimate. Sturges obliged. Yet he somehow persuaded Breen to retain this later portion of the Alfred-Charles exchange, also alluding to an adulterous affair.

Charles: They [Jean and Eve] look exactly alike!

Sir Alfred: We must close our minds to that fact…as it brings up the dreadful and thoroughly unfounded suspicion that we must carry to our tombs, you understand…as it is absolutely untenable…that the coachman, in both instances…need I say more?

Why did Breen let Sturges keep in this suggestion that Handsome Harry was the biological father of both sisters, perhaps as the result of adulterous affairs? It is hard to say. True, the offending line concerns a “suspicion” voiced by Sir Alfred, rather than a fact. But Charles immediately affirms its likelihood: “But he did, I mean, he was, I mean…” before being shushed for the nth time by Sir Alfred. Here again, Breen consented to Sturges’s use of questionable material.

Breen’s greatest objection in his initial letter concerned pp. 70-74 of the first submitted script, which suggested “a sex affair.” “Inasmuch as this is treated without the proper compensating moral values, it is in violation of the Production Code, and will have to be eliminated entirely from your finished picture.”

The offending pages outlined a scene between Charles and Jean set on the deck of Jean’s cabin at the end of their first evening together. Just previously, Jean has caught Charles and her father the Colonel (Charles Coburn) playing double or nothing. Charles would then be called away to receive from the ship’s purser the incriminating photo of Jean, the Colonel and Gerald. Charles would then return to the gaming room table and the dialogue exchange with Jean about all women being adventuresses. Then Charles would ask Jean if they can go down to her cabin. There, Charles lights Jean’s cigarette; he “struggles to say something” but Jean tells him, “Kiss me,” and he obeys. (“He crushes her in his arms” as she “sinks back against the chaise longue.”) The film would then cut to a shot of the rail of Jean’s deck and of “the moonlit water beyond. A lighted cigarette arcs over the rail and down into the water. FADE OUT.”

This version presents Charles sleeping with Jean even though he knows from the purser’s photograph that she’s a cardsharp. As Brian Henderson notes, this arrangement of events would make Charles a cad, far worse than the hypocritical prig that he is in the finished film. Sturges eventually solved the problem by having Charles learn of Jean’s duplicity on the morning of their third day together at sea. But before Sturges made this change, Breen’s October 9 letter directed that Charles could not speak the line about going down to her cabin; that the scene could not play out on Jean’s private deck; and that “it would be better to have the embrace with the couple standing up.” The shot of the cigarette thrown over the railing also “should be omitted, on account of its connotations.”

In response, Sturges watered down the offending scene of passion and relocated it to the bow of the ship, where (in a reworking of a scene he had always envisioned) Charles recites his “I’ve always loved you” speech and they eventually embrace as the scene fades out. This created the PCA-approved ambiguity about what transpired sexually between them.

Here, Sturges’s solution to a problem of plot and characterization went hand in hand with the double-meaning practices of the Production Code. Sturges must have written the passionate private deck scene knowing full well that Breen would demand its elimination or transposition. His immediate agreement to revise it was likely a bargaining ploy to earn Breen’s goodwill to bank against other PCA objections.

When Sturges cut the cabin deck setting and the prone postures of pp. 70-74 from the first submitted script, he also saved a crucial part of Jean and Charles’s penultimate exchange as they enter Jean’s cabin.

Charles: Will you forgive me?

Jean: For what? Oh, you mean…on the boat…the question is, will you forgive me?

Although Breen accurately predicted that this bit of dialogue would “probably be acceptable” if the earlier scene “is cleaned up,” for now, Breen stated that their exchange had to be cut “by reason of its reference to the aforementioned sex affair.” In other words, Breen, not unreasonably, read Jean and Charles’s dialogue as referring only to their sleeping together, rather than to everything that transpired between them on the S.S. Southern Queen, including Jean’s duplicity and Charles’s narrow-mindedness. Forgiveness is of course a key issue in the drama of The Lady Eve.

Hix Nix Sexy Pix

The MPPDA issued its seal on 26 December 1940. Released in mid-March 1941, The Lady Eve passed the censors without cuts in Chicago and the states of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia. However, Kansas, Maryland, Ohio and Pennsylvania were a completely different story.

Some local censors demanded deletions of elements Breen had highlighted. Ohio and other localities objected to Sir Alfred’s dialogue about the fantasy fatherhood of Jean and Eve (“as it is utterly untenable that the coachman in both instances. . . .”). But most of the eliminations concerned elements Breen and his team had not commented upon. Among these were (again for Ohio, initially) Sir Alfred’s summary recap of the tale to Jean the next morning: “So I filled him full of handsome coachmen, elderly Earls, — young wives, and the two little girls who looked exactly alike.”

Other targets were Jean’s wisecracks. When Jean and Charles return from her stateroom after changing her shoes, the Colonel archly comments, “Well, you certainly took long enough to come back in the same outfit.” Jean’s reply–“I’m lucky to have this on. Mr. Pike has been up a river for a year”—offended Pennsylvania. Ohio objected to Jean’s comment, “That’s a new one, isn’t it?”, when Charles invites her into his cabin to see Emma.

Yet another instance concerned Charles’s exchange with Eve during their wedding night train ride. He is asking about her previous marriage to Angus.

Charles: When they brought you back, it was before nightfall, I trust.

Jean: Oh, no.

Charles: You were out all night?

Jean: Oh, my dear, it took them weeks to find us. You see, we’d make up different names at the different inns we stayed at.

Though Jean and Angus were married, the implication of using false names at a hotel (which Sturges would recycle for Trudy and her unknown husband in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek) was the deal-breaker for Ohio. Of course, one possible connotation of Eve’s many pre-Charles couplings is that not all of them were marriages. (If they were, this imaginary Eve is an early version of the Princess in The Palm Beach Story, another figure who satirizes conventional marriage.) Yet Breen’s only comments on this scene concerned Eve’s nightgown and particularly the scene’s blocking—that Eve’s revelations of her previous marriages occur away from the bed and that the bed be deemphasized throughout the scene.

Sturges must have made the case that there was no room to have the actors sit elsewhere. Meanwhile, Breen was distracted from what Jean was saying by where she was when she said it.

Local censors were most keenly opposed to two other scenes that Breen had ignored. Both take place in Jean’s stateroom.

In the first, Charles replaces Jean’s broken shoe. In one twenty-second two-shot, he kneels down to slip the shoe on her foot; looks over her foot and slowly looks up her leg all the way to her face; expresses his hope that he didn’t hurt her when she tripped him in the dining room; and then on his way to looking down at her leg and foot again, pauses momentarily but very definitely, on her décolletage. Then he looks back up at her again. There is no dialogue to distract the viewer from what Charles is looking at.

Oddly, no censors objected to this very suggestive shot; instead they focused on what ensued. Ohio, Kansas, and Maryland joined Pennsylvania in demanding the elimination of what the last described as the “semi close-up view where [Charles] allows his eyes to pass up and down over her.” This was a quick POV series of shots in which (1) Charles struggles to look at Jean; (2) Jean appears blurry and asks Charles if he’s all right; and (3) Charles, after swallowing, struggles to reply in the affirmative.

Charles is so “cockeyed” from Jean’s perfume that when they eventually stand up, he can make only the weakest attempt to kiss her, which Jean easily repulses. To the censors, however, the combination of close shot scale, physical intimacy, and intoxication (even from perfume) was intolerable–too expressive of Charles’ rising desire. I suspect they actually conflated the lengthy take and the medium close-ups (no “looking over” occurs in the point of view sequence). In any case, censors had seldom seen such “looking over” shots since the early 1930s.

In addition, all four offended states were roused by the famous chaise longue scene. As Charles tries to apologize for scaring Jean with his snake Emma, she holds him close, runs her hands through his hair, tickles his ear, and breathes heavily in his face. Taking the key elements of the shoe-replacement business to another level, the erotic hilarity of this scene arises from the complete power of Jean’s spell over Charles and their sheer proximity, in two long takes (one lasting 36 seconds, and then a closer, three-minute and fourteen-second shot). During all this time, Jean won’t let Charles kiss her, but their faces are close together and their lips are never far apart. For some censors, the most provocative elements of the scene resided in the dialogue that begins with Charles’s fall to the ground ands run through his “accompanying indecent action” (Pennsylvania again) of pulling down Jean’s skirt.

Pennsylvania also cut Jean’s sigh of anticipatory orgasmic release after describing her first encounter with her future husband: “And the night will be heavy with perfume and I’ll hear a step behind me and somebody breathing heavily and then – Ohhhhh!”

Ohio originally wanted the entire scene deleted, starting with Jean’s command “Oh, come over here and sit down beside me” through their final exchange:

Jean: Oh, you’d better go to bed, Hopsy. I think I can sleep peacefully now.

Charles (adjusting his bow tie): Well, I wish I could say the same.

Jean: Why, Hopsy!

Industry representatives negotiated with the Ohio and Pennsylvania boards to try to reduce their demands; Pennsylvania was unmoved, but Ohio was persuaded to let all but their final exchange remain in the film. An outraged San Antonio Amusement Inspector articulated the boards’ thinking when she cut what she called the film’s two “prolonged scenes of passion” in Jean’s stateroom. These, she pointed out to Breen, violated Section 2 of the Code, about “suggestive postures and gestures” and seduction being used for comedy. So in San Antonio, as in Pennsylvania and Kansas, viewers missed the bulk of two of the most celebrated comic scenes in American film history.

With The Lady Eve, Breen’s instincts were generally astute. He had advised against Sir Alfred’s sketch of the Handsome Harry plot. He had eliminated the overt sex affair scene in Jean’s cabin. Yet he missed many elements as well. Besides those stateroom scenes cut by state and city censors, there were ostensibly innocent lines. As Charles searched for a new pair of shoes, Jean says, “See anything you like?” and leans back with a bare midriff.

The constantly repeated phrase “been up the Amazon for a year” references Charles’s extended sexual privation and naivete, which make him susceptible to Jean’s wiles. But the phrase can also be taken as evoking female anatomy itself. The neglect of these details resulted from Breen’s increasing tolerance and his equally increasing tiredness. We’re lucky he left them in.

Upping the ante

The negotiations over The Palm Beach Story and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek followed the pattern set by The Lady Eve. The writer-director proposed increasingly outlandish scenarios; Geoffrey Shurlock and Breen again demanded an increasinglyu longer list of changes across a longer series of letters. Sturges alternately made cuts or assured them he could handle the material.

Once more, certain moments wound up offending local censors. For The Palm Beach Story, released in late 1942, only New York and Kansas passed the film without eliminations. Elsewhere, many of the suggestive elements that Shurlock had criticized were cut. One was Gerry’s line—describing how Tom sees her after many years of marriage–as “just something to snuggle up to and keep you warm at night, like a blanket” (Pennsylvania). Another was the first vertebrae-kissing scene in which a very drunk Tom breaks down a very drunk Gerry’s resistance to having sex.

Other deletions concerned details that had escaped Shurlock’s notice: Pennsylvania removed the underlined portion of Gerry’s explanation to Tom, after the Wienie King’s visit and munificence, of “the look” women get from men: “From the time you’re about so big, and wondering why your girl friends’ fathers are getting so arch all of a sudden – nothing wrong – just an overture to the opera that’s coming.” Even after many changes to her dialogue, scenes with Princess Centimilia could have provoked bans or major cuts. After all, she is followed around by her gigolo Toto (Sig Arno) and (in an ironic adherence to the Code’s demands) marries purely to legitimize her sexual impulses. Yet in part because of Mary Astor’s frantic line delivery, her scenes were retained. Overall, relative to its many potential offenses, The Palm Beach Story faced surprisingly minimal objections.

The entire premise of Miracle and the ensuing action mock the notion of marriage’s sanctity from multiple angles. Breen, the American military, and the Legion of Decency examined the film minutely before it was issued a seal, and many changes were made. For this reason, only one state board (Kansas) cut one line of dialogue: Trudy’s comment that “Some sort of fun lasts longer than others.”

Still, there was much to offend audiences and censors in the completed film. For example, the MPPDA and Sturges received numerous letters of complaint linking the film to the growing problem of juvenile delinquency. One viewer in Minneapolis wrote that the film showed it to be “a subject for slapstick and high comedy, especially if the delinquent is unusually fruitful. . . . My boy thought she must have passed the night with 6 soldiers or sailors. . . . In Hollywood I understand you can get away with despoiling young girls and morals don’t exist except for yokels. Do you have to spread that poison?” Given the growing panic over what was seen as a national JD epidemic, Paramount’s delay in distributing Miracle—it was completed in Spring 1943 but released in January 1944—exacerbated the controversy.

Upon reviewing The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, James Agee famously stated that “the Hays office has been either hypnotized …or raped in its sleep.” The same might seem to be true of The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story, but this was manifestly not the case. There were elements that the PCA didn’t catch–suggestive postures and dialogue, scenes of seduction–because Sturges created so many and whisked them by so swiftly. But he got away with it for other reasons as well. The PCA helped steer Sturges to finding ways of modifying the most brazenly unacceptable material. The standards of acceptability were expanding, controversially, and they would continue to do so. Meanwhile, the response of local censor boards and individual audience members provides crucial evidence of how at times the PCA succeeded and at other times it failed to suppress material that might offend. Knowing this history can only deepen our appreciation of what the Sturges comedies achieved.

This entry is a revised version of a portion of an article that appears as “The edge of unacceptability: Preston Sturges and the PCA” in Refocus: The Films of Preston Sturges, editors Jeff Jaeckle and Sarah Kozloff, forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. Primary sources include Sturges’ correspondence and the PCA files housed at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills. The Lady Eve and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek files are available on microfilm in MLA, History of Cinema: Selected Files from the Motion Picture Association of America Production Code Administration Collection (Woodbridge, CT: Primary Source Microfilm, 2006).

I’ve also drawn on these published sources: David Bordwell, “Parker Tyler: A suave and wary guest”; Brian Henderson, Five Screenplays by Preston Sturges (1986); Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Work of Preston Sturges (1994); Lea Jacobs, The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film (1997); Kathleen Rowe, The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter (1995); and Elliot Rubenstein, “The End of Screwball Comedy: The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story,” Post Script 1, no. 3 (Spring-Summer 1982), 33-47.

Comic-Con: The end of an era, and other highlights

Kristin here:

Long-time readers of this blog may recall that in 2008 I went to Comic-Con for the first time. I can’t recall exactly what led me to take the plunge. It may have been that by that time it was evident that the con had grown into a major opportunity for Hollywood studios to publicize their upcoming blockbusters to their core audience and I wanted to witness the process in person. Until this year, I hadn’t returned to Comic-Con. I was motivated in part by the fact that this was the last big promotional event for a film in the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise. I had briefly discussed Comic-Con in relation to LOTR in The Frodo Franchise, but I had not witnessed any of the appearances of cast and crew promoting the first trilogy. This was my final chance, the end of an era.

I blogged about my first visit four times. I wrote about the LOTR/Hobbit presence on the Frodo Franchise blog. On this blog I gave an overview of the Comic-Con experience, analyzed why Hollywood poured so many resources into an event nominally about comic books, and posted a conversation between Henry Jenkins and me. Henry, who had helped found the area of fan studies back in the 1990s with such widely cited publications as Textual Poachers, was also a Comic-Con newbie that year, and we shared our reactions. (This year Henry was on a panel, “Creativity Is Magic: Fandom, Transmedia, and Transformative Works,” one of a number of panels on fan culture. I missed it because I was in line for Hall H. More on that below.)

A friend of mine who has a press pass assured me that they were not as hard to obtain as I had feared, so, based on my collaboration on this blog and my position on the staff of TheOneRing.net, I applied. To my delight, I was granted one, so I set out to cover Comic-Con more officially.

Going to Comic-Con alone isn’t nearly as fun, and I was lucky enough this year to meet up there with my friends, Professors Jonathan Kuntz and Maria Elena le las Carreras and their irrepressible daughter Rebecca, who are always terrific company.

Preview night

On the Wednesday evening before Comic-Con begins, there is a preview. This means that people with various special passes can get into the big exhibition hall where most of the booths are set up. These range from dealers in rare comic books to the biggest entertainment companies, like Warner Bros. and Lego. Many of them offer unique items only for sale or give-away at Comic-Con.

Many attendees have realized this, and they buy tickets that include the preview evening. The floor was much more crowded than when I attended the preview night in 2008. There were lots of lines with people trying to get those unique collectibles.

Others were there to look at comics. Yes, there are still plenty of comics at Comic-Con. There are dealers offering rarities, as in the image above. There are comics publishers with their latest offerings.

A particular favorite of ours is Fantagraphics, which specializes in reprinting comics. They’ve launched a set of hard-cover volumes of Walt Kelly’s syndicated Pogo strips. They also, I discovered, are doing a series of Don Rosa comics, also in hardback. In fact, when I was strolling around the booth, I realized that Rosa himself was signing autographs until 8 pm. It was then 7:59, so I grabbed volume 1 and was the last person to get my copy signed. By the way, it includes “Cash Flow,” one of the Uncle Scrooge stories I mentioned in our first blog entry on Inception. Volume 1 hasn’t actually been published, but it’s available for pre-order on Amazon.

The big moment of my evening, entirely by chance.

My first press conference

Once you’re granted a press pass, your name is put on a list made available to the exhibitors and publicists planning events. Companies big and small send you announcements about signings, press  conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

I showed up and got a front-row seat off to the side. The room filled up (right).

The event itself started somewhat late, and two gentlemen who were not Benedict Cumberbatch or John Malkovich appeared and answered some questions. (I would give their names, but the usual signs put on the table in front of guests were not in evidence.) We were approaching 11:25. John Malkovich and another gentleman appeared. Another couple of questions were asked, and someone announced that Benedict Cumberbatch’s plane had gotten in late the night before and besides we had to leave to make room for the next event scheduled in the room. We were not escorted to reserved seats in Hall H, where I hear that Benedict Cumberbatch did appear.

I can only trust that this is not how most press conferences turn out. Perhaps I will be invited to another one and find out.

Bill Plympton in person

Given that I had no option to go to the Hall H DreamWorks Animation presentation, I sought out an alternative among the several items offered during the noon slot. I had had my eye on a panel which had as its guests the well-known animator Bill Plympton, as well as Jim Lujan, the co-director of the feature-length Revengeance, in progress. David and have long been fond of Plympton’s work, especially his laugh-out-loud classic, Your Face (1987), which was nominated for an Oscar. It’s just a series of distortions of a man’s face as he sings an utterly wimpy love ditty (above).

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Apart from clips from Revengeance, Plympton also showed a brand new short, Footprints, a charming tale of a man’s search for a mysterious house invader. It will be shown on August 14 as part of the Hollyshorts Film Festival, which will honor Plympton with the Indie Animation Icon Award. The film was entirely hand-drawn in black and white and then colored digitally.

During the panel there was a contest for a T-shirt. The question was: What is Bill Plympton’s middle name? Despite a plethora of cell phones, laptops, and tablets in the audience, no one could come up with the right answer. A second question was put forth: what was Plympton’s first theatrically released film? “The Tune,” came a cry from the audience. It was Sam Viviano, art director of Mad Magazine; he walked off with the shirt. Plympton then sheepishly confessed that his middle name is Merton.

Plympton’s films have been hard to find online, but this fall they will become available on Source HD: “It’s the entire catalog, everything I’ve ever done.” That includes about 60 shorts. As a result of this online exposure, he says, “I expect that when I come back to San Diego next year they’re going to have to give me one of those huge 2000-seat rooms.” I hope so, and I hope it will be filled–but not so jammed that I could not get a seat.

Plympton offered all attending his panel a free autographed drawing. I went to collect mine at his booth in the exhibition hall and found him drawing (right), as he must constantly be doing. Note the Cheatin’ poster behind him at the left and the usual bustle of Comic-Con in the background. He paused to dash me off a delightful image of his famous Dog character. (An animator who doesn’t use cels has to be really fast at drawing.)

Plympton DVDs are not all that easy to find, though you can get them and other merchandise at his website’s shop. If you don’t know his work, it’s time to start catching up.

A new experience: The Indigo Ballroom

Seeking to accommodate more fans without violating fire regulations, Comic-Con has expanded into nearby buildings. One of the facilities utilized this year was the Hilton San Diego Bayfront, just across from the Convention Center on the Hall H end. That’s where the DreamWorks press conference sort of took place. Its biggest room was the Indigo Ballroom. I’m not sure it had 2000 seats, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

My colleagues at TheOneRing.net have been presenting panels on the Hobbit series for several years now. In fact, my visit to Comic-Con in 2008 was as a participant on one of those panels, speculating much before the fact on the shape that the Hobbit project would take. At that point the cast hadn’t even been chosen. I suggested that Wisconsin’s own Mark Ruffalo would make an excellent Thorin. I still think he would have, but Richard Armitage has gained a large fan following in that role. I’m not sure that at that early stage Martin Freeman was everyone’s favorite candidate for Bilbo, but he soon became so–including mine. The man is a born hobbit.

That 2008 panel took place in a relatively small room in the Convention Center. In more recent years, the TORn panel has been joined by such luminaries from the filmmaking team as Richard Taylor. It has gained such a following that this year it was booked into the Indigo Ballroom.

Then we learned that George R. R. Martin was booked into the same room in the time-slot directly before TORn. (I’m sure you all know who he is, but for the few who don’t, I’ll just say, he’s the author of the “A Song of Fire and Ice” series, of which Game of Thrones is the first book.) We were all convinced that Martin’s session would be jammed and furthermore that an overlap in fandoms would mean that the audience there for Martin would stay for the TORn panel, excluding those who showed up just before the TORn session. There was much discussion as to how TORn staff not on the panel (like me) could get in and be sure of a seat. How many seats could be reserved? We didn’t know.

I determined to support my colleagues and attend the TORn panel. The question was, how many sessions would I have to sit through to make sure I could get a seat? (Rooms are never cleared between sessions at Comic-Con, since doing so would take too much time and would mean that people in one room for a session would not be able to get in line for the next session in that room. Hence the strategy of sitting through multiple panels in the same room to guarantee a seat at the one you really want to see.)

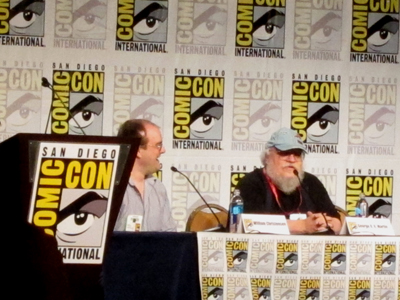

I arrived early in the afternoon in the middle of a session about some show on Comedy Central. This finally ended and the George R. R. Martin panel began. To my surprise, it was only about two-thirds full. I learned later that Martin often attends Comic-Con. Moreover, this time he wasn’t talking specifically about Game of Thrones. The session was billed as “George R. R. Martin Discusses In the House of the Worm.” The title in question is a new comic-book series that Martin is involved with. (Above, William Christensen, publisher at Avatar Press, interviews Martin.)

I had expected to sit through Martin’s session merely waiting for the TORn one to begin. I had read Game of Thrones, widely assumed to be heavily influenced by The Lord of the Rings. Game of Thrones was entertaining, but by the end I found it repetitious. I figured that the series could only become more so, so I quit there. I haven’t seen the TV episodes. Yet Martin turned out to be quite entertaining. He is a long-time fan, and his reminiscences about fandoms during the 1960s and onward were fascinating. He’s a lively, knowledgeable, and entertaining speaker with a wide experience in both reading and creating fantasy works in those days. His presentation made me wish that I liked that first book better.

The next session was “An Unofficial Look at the Final Middle-earth Film: The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies.” (Actually in the program the title said “Final Middle-Earth Film,” but I’m sure my colleagues did not make that capitalization error when they proposed the panel.)

The panel consisted of, from the left, Chris “Calisuri” Pirotta, a TORn co-founder; John Tedeschi, long-time staffer; Cliff “Quickbeam” Broadway, frequent contributor to the site; Kellie Rice, staffer and half of the “Happy Hobbits” fan duo; and Larry D. Curtis, another long-time staffer and frequent contributor. Chris and Cliff were among several TORn interviewees when I was researching The Frodo Franchise.

TORn has made annual appearances at Comic-Con, usually speculating in expert fashion on what might be included–or not–in the next film. Staffers comb the previous films, trailers, Peter Jackson’s production diaries, publicity photos, and cast and staff interviews, seeking for clues. While presenting their findings, they point out things in the earlier parts that people might not have noticed or may have forgotten.

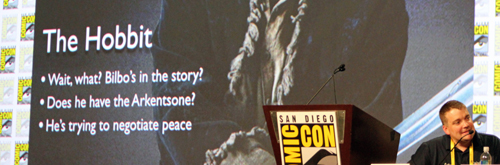

The first line in the Powerpoint image above refers to widespread fan annoyance that Bilbo seems to have been pushed to the periphery of his own story in The Desolation of Smaug. This is a topic of frequent comment on the website. The TORn panel was held on Thursday, two days before any of us had a chance to see the first teaser-trailer’s premiere on Saturday in Hall H. (More on that below.) Although there are shots of Bilbo in that trailer, they mainly show him staring offscreen and reacting. I was left hoping that this is not an indication of more sidelining of our protagonist. In Tolkien’s book Bilbo decides to sit out the Battle of Five Armies and gets knocked unconscious early in the fighting; given that he’s our point-of-view figure, the battle is mainly told through other characters describing it afterward. No one expects Peter Jackson to stay true to that action and sacrifice the chance for another epic battle scene, so maybe Bilbo will get to do his share of fighting.

This year’s celebrity guest made an appearance at the end and took a few questions: Jim Rygiel, multi-Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor for The Lord of the Rings (and more recently Godzilla and The Amazing Spider-Man):

Whether the panel members were right in their speculations will not be known until December 17 (in the USA). Right or not, it was an entertaining and informative session.

What were they really there to see?

There are many rooms devoted to Comic-Con events, not to mention the various open-air booths and attractions set up in open spaces near the convention center. Room 25ABC is fairly large, but it’s considerably smaller than the Indigo Ballroom, 23ABC, and of course, Hall H. I was not alone in being puzzled as to why the panel “Fight Club: From Page to Screen and Beyond,” was scheduled in 25ABC at 7 pm on Saturday evening. Sure, the topic was an older film, and the panel was largely devoted to a forthcoming graphic-novel sequel to the story. Still, the participants included David Fincher, making his first Comic-Con appearance. I can only suspect that Fincher was a late addition to the panel’s line-up and it was too late to change the venue.

The result was that anyone determined to hear what Fincher had to say was bound to line up for the panels just before the Fight Club one and sit through them in order to see it. I decided to line up for “Disney’s Gargoyles 20th Anniversary” at 5 pm, having no idea what the Gargoyles are, and “Publishing 360: Building a Bestseller” at 6 pm, having no intention of trying to build a bestseller.

I got into a line that looked fairly short and was defined by lines of tape laid down on the carpets in the broad corridor outside 25ABC. It turned out to be one of those Disneyland-style ribbon-candy set-ups, where the line folds back on itself time after time, and you end up walking in one direction, turning around to walk in the opposite direction, only to realize that there is another group of people doing the same thing ahead of you in the same line. Fortunately most people seem to stick to the rules pretty closely, perhaps being aware of the wrath they would call down upon themselves by attempting to cut ahead of others.

I ended up about ten people back in line when the room was full. I never did learn what the Gargoyles were, but I suspected some people behind me had been hoping to get into that panel and were not there for the Fincher event. Indeed, as it became clear that no seats were going open up, a small number of people departed, leaving me about six people back from the front. It was looking good for me to get into “Publishing 360.”

At this point, from behind me I heard “Pardon me, but are you Kristin Thompson?” or words to that effect. Thus I met Ryan Gallagher, one of the stalwarts of The Criterion Cast, which describes itself as “A podcast network and website for fans of quality theatrical and home video releases.” (It is not officially associated with The Criterion Collection.) I recognized his name because he has sent many a reader to Observations on Film Art. Ryan’s latest podcast is a preview of Comic-Con, and I expect he will add one looking back on his experiences there.

What are the odds, I thought, and still think, that with 125,000+ visitors to Comic-Con, I would end up in line next to someone who recognized me? Turns out Ryan had been in line for the Gargoyles panel, so after a brief conversation, he departed. Eventually I was among the first into the room for the “Publishing 360″ panel, though there were people already there who didn’t leave, and I suspect the audience for Gargoyles doesn’t overlap all that much with the audience of people longing to write a bestseller. The procedure for building a bestseller, by the way, seems to consist primarily of getting the best agents and editors in the world. Aspiring writers, take note. Before the session began, I located an unoccupied electrical outlet and recharged my recorder. (This is a serious business at Comic-Con. The convention center is full of cell phones, tablets, and cameras dangling from outlets.)

The panel as pictured above consists of, from the left: moderator Rick Kleffel, Doubleday executive editor Gerald Howard, Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk, David Fincher, and three artists and/or editors from Dark Horse Comics, which will bring out the Palahniuk-penned ten-part sequel starting in May, 2015.

A lot of the panel was about the graphic-novel sequel, of course. The main bit of new information about the film was that although it didn’t do particularly well at the box-office, Fincher finally got 20th-Century Fox to give him figures on how many DVDs were sold. Sales totaled around 13 million, so Fincher reckons the film must have made a profit in the long run. Probably the quotation from Fincher that will be remembered is: “My daughter had a friend called Max. She told me Fight Club is his favorite movie. I told her never to talk to Max again.” Fincher may not have been to Comic-Con before, but he knows how to please the fans.

Check out the Film website for an audio recording of the panel.

Hall H: Getting in

Hall H tends to draw much of the attention accorded to Comic-Con in the media. It’s the largest venue, with 6500 seats–including a large number reserved for representatives of the studios presenting publicity events there. That’s a big venue, but compared to the roughly 125,000 people attending the con each day, it’s not big enough. Although not everyone at Comic-Con wants to get into Hall H, most days the lines snake down and across the street, along the sidewalks. (A video moving along an entire Hall H line at a walking pace was posted on Youtube last year. It runs for over fourteen minutes, despite the fact that the people toward the front of the line are walking forward past the camera; if they were standing or sitting still, it would have run even longer.) In previous years the only way to guarantee getting into the hall for the first events of a day was to get there the previous evening and stay in line overnight. Short departures were possible if someone held your place, but basically you were there for the duration.

I was lucky enough to benefit from the innovation of a new policy on Hall H admissions. Color-coded wristbands would be handed out as the line formed, pausing at 1 am and resuming at 5am. The first portion of the line got a red band, with other colors for the next portions. The purposes were 1) the management could gauge how many people were lined up; 2) those in line could know whether they would get in or not; and 3) for the first time some people could leave for longer stretches of time than required for a rest-room break, as long as someone from their group with the same color wristband remained.

At least, that was how it was described in the online announcement. Those charged with distributing the bands and keeping order informed us that “a majority” of the group had to remain. To what degree that was enforced, we never learned. Fortunately that worked for Jonathan, Maria Elena, and I, since Rebecca had formed a “Hall H-line” group on Facebook and assembled a bunch of friends to camp out in line together. We adults, with our less flexible bones, departed for dinner and some sleep at our hotel. The next morning when we came to rejoin our group, the people in charge of keeping order asked if we had been to the rest room. Yes, we had. That and other things. Apart from everything else, the parking garage under the convention center has to be cleared after 10 pm, so the Kuntzes had to leave to get their car out. Clearly some clarifications of the guidelines are in order, but based on our experience the new wristband policy has improved the Hall H-line experience considerably.

The announced wristband-distribution schedule also had to be adapted. In the past, the Hall H line has started forming in the late afternoon or early evening, depending on the popularity of the first event scheduled for the following morning. Jonathan presciently went and got in line at 2:30 pm, and he was far from the first. Our party gradually grew as other members arrived, and inevitably groups ahead of us also swelled. Soon the line was very, very long. (A small portion of it is pictured above; the line had taken a U-turn a few hundred feet behind us, off right here.) Somewhere around 6:00 the wristbands started to be handed out, and small groups were escorted across the street to line up in the relatively luxurious area on the grass near the entrance to Hall H. There were white canopies overhead and the inevitable red plastic barriers dividing the area into rows approximately one reclining person wide. Those further back in line were less fortunate, having the sidewalk to call their bed. Our group of young stalwarts settled in for games, sleep, and an endless supply of trail mix and donuts. Rumor has it that anyone who arrived after about 9:30 pm didn’t get in. The last wristbands were handed out at around 2:30am. Presumably the handout did not pause at 1 am as planned, since clearly everyone who was going to get in when the hall opened was already there.

The next morning we received a call from Rebecca saying the group had been moved into the “chutes,” a process which had started at 7 am. These are slightly narrower strips of grass with the same plastic barriers; the chutes are opened one at a time, allowing the people in each to go in before the next chute is opened. More people are moved into the emptied chutes, and the process continues until the hall is full.

Although the handlers had said we would be let in at 9:30 for a 10:00 start, they got the process going at 9 am. By 10 we were all seated and ready for the Warner Bros. extravaganza to begin. There I am, wearing my vintage licensed Fellowship of the Ring T-shirt and the crucial pink wristband:

Expensive flash

Warner Bros. had two hours in Hall H on Saturday morning to promote their films. The full program is not announced in advance. People were assuming that The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies, as the biggest item on tap, would be saved for the end. That turned out to be correct.