Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Caught in the acts

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005).

DB here:

If you’re interested in how films tell stories, I think that you’re interested in several dimensions of narrative. Those include the story world (characters, settings, action), narration (how story information is parceled out as the film unrolls), and plot structure (the arrangement of parts).

Plot structure matters because a movie’s parts, like parts of a song or a symphony, help shape our experience. Just as a “curtain line” makes us return after intermission, a cliff-hanging climax to a TV episode makes us tune in next week–or click to continue, if we’re binge-watching. Accordingly, storytellers reflect on how to chop up and lay out sections of their plots. Novelists fret over chapter divisions, TV writers massage their scripts to allow for commercial breaks, and playwrights map action into acts.

The idea of act-structure has passed into commercial screenwriting as well. Just when that happened is hard to say, but certainly by the 1980s scriptwriters consciously broke their screenplays into big chunks. That trend was largely the result of Syd Field’s 1979 book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, although some of his points had been anticipated in Constance Nash and Virginia Oakley’s Screenwriter’s Handbook (1974). From these books came the idea that a feature film script had a three-act structure, measured by time segments (30 minutes/ 60 minutes/ 30 minutes). The prototype was a 120-minute film, with each script page running about one minute of screen time. Field fleshed the model out by noting that “plot points” at the ends of acts one and two turned the conflicts in a new direction. Although other writers argued for other templates, and Field’s model was refined (what’s the “inciting incident” in Act One?), versions of the three-act model still rule the international film industry.

Field presented his anatomy as an analysis of hit films like Chinatown and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He suggested it as a template for a successful plot. As Field’s book gained prominence, his guidelines gave production companies an heuristic for triaging submissions. Now a story analyst could simply check pages 25-35 and 55-65 for turning points, and “incorrect” scripts could be discarded immediately. (But see P.S. below.) Through a feedback cycle, the Field model became a guide to both screenwriters and industry decision-makers. Inevitably, the whole thing got mocked. The day-by-day structure of Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang parodies Field’s scheme, and it closes with a self-conscious epilogue. “So,” says the narrator, “that’s pretty much that….”

To what extent, though, was the three-act structure employed in earlier eras? Field’s original edition drew its examples from current hits, but he implied that classics would display the same underlying architecture. Kristin, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, claimed that four parts were more common than three, and she supported her analysis with examples from films from the silent era and the classic studio years.

But film analysis depends on your perspective. In any movie you can find patterns different from the ones I find, and each of us can make persuasive cases. It would be valuable to know whether American screenwriters in the studio system consciously worked with an act-based model. If they did, what assumptions did they make about the length and organization of each act?

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

For some time, I’ve held the same view. I couldn’t find any script draft broken into acts. Some veteran screenwriters admitted using a three-act model in plotting, but their testimony came long after the era. So, for instance, Philip Dunne says he used a three-act organization for his 1940s screenplays, but he makes the claim in an interview published in 1986. Billy Wilder says he “wrote [Charles Boyer] out of the third act” of Hold Back the Dawn (1941), but the remark comes in an interview given decades later. There’s always the possibility that older writers, newly aware of the Fieldian template, were projecting it backward onto their work—assuring us that they conform to contemporary standards, or even asserting precedence.

Similarly, we can’t rely too much on secondary sources. True, screenplay manuals, from at least 1913 onward, have recommended a three-part structure, purportedy corresponding to Aristotle’s idea that a plot must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But this rests on a misunderstanding. As I’ve mentioned before, Aristotle isn’t talking of acts; ancient Greek plays didn’t have act divisions. And almost none of the manuals use the term “acts” to describe the parts.

Richard Brooks’ novel The Producer (1951), about a weak-willed executive trying to do the right thing, offers some hints along similar lines. He mentions that a screenplay should run to 120 pages, confirming the canonical length that Field proposes. Likewise, Brooks obliquely appeals to Aristotle.

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter has to create a beginning, a middle and an end, and all the dialogue.

Perhaps there’s an intentional irony in the fact that Brooks’ Hollywood exposé is itself broken into three parts, labeled “The Beginning,” “The Middle,” and “The End.”

Unlike many authors of manuals, Brooks was an established screenwriter, and we might expect his novel to refer to acts. It doesn’t. But Lewis Herman, a minor scribe with three screen credits (including Anthony Mann’s Strange Impersonation), does. His 1952 manual declares that a feature-length film is built upon “a three-act theme outline.” The context suggests that the Hollywood studios demand this as a step toward developing a full screenplay. Herman usefully illustrates the outline with a hypothetical example.

Still, manuals or novels aren’t ironclad sources for studio practice. Better would be contemporaneous evidence from memos, story conferences, and similar unpublished documents. Claus Tieber has done extensive research into such sources and has found no discussions of three-act structure. I’ve found a few, but they’re fairly sketchy.

Overseeing Casablanca, Hal Wallis told Michael Curtiz, “The Epsteins have agreed to deliver the film’s ‘second act’ the following day.” Darryl F. Zanuck mentioned the “last act” in correspondence about Viva Zapata! and On the Waterfront. Supposedly John F. Seitz asked Preston Sturges about the flashback structure of The Great Moment: “Why did you end the picture on the second act?” As I noted in an earlier entry, David Selznick’s papers record a story conference on Portrait of Jennie in which Jed Harris remarks: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” He adds that at this point the film “is about 1/3 gone.” This suggests that some practitioners thought of the parts as roughly equal in length. (Kristin’s model proposes that this was the case.)

It may be, of course, that three-act structure of some sort was so ingrained in studio writers’ habits that they didn’t have to discuss it explicitly. Field was addressing aspiring screenwriters who wanted inside knowledge, but as intuitive craft workers, the old contract writers wouldn’t be likely to spell out rigid rules about length and dramatic patterning.

Since corresponding with Steven for his book, I’ve found that one screenwriter explicitly invoked three-act structure in his working notes. And I’m embarrassed not to have noticed it earlier.

Coupling, recoupling, and Joe Breen

F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sheilah Graham.

NICOLAS: Marriage has its phases–its acts–like anything else. This is another act, that’s all.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, screenplay for Infidelity.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Hollywood career was mostly a fiasco. Thanks to temperament, a mentally disturbed wife, bouts of breakdown and alcoholism, and an implacable industry, he worked his way down the hierarchy to unemployment. From July 1937 to his death in 1940, he earned screen credit for just one film, Three Comrades (1938). He also started, but didn’t finish, the best Hollywood novel I know, The Love of the Last Tycoon (aka The Last Tycoon). I think it spells out some features of the Hollywood aesthetic with special vividness.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

Back in the present, to ramp up his mood, Nicolas decides to hold a party in the country estate he had more or less abandoned. At the same time, Althea rekindles her friendship with a former suitor, Alex. She can’t arouse herself to passion, though, and Alex leaves her. As she drives more or less hysterically to the estate where the party is in full swing, Nicolas is wandering through his mansion among the shrouded furniture.

At this point, because of objections from the Production Code office, Stromberg halted Fitzgerald’s work on the screenplay. Aaron Latham’s biography tells us that Fitzgerald had planned to present a reconciliation, in which a photographic trick presents Althea seeing herself as Iris and thus forgives Nicolas. But this ending would suggest that the husband’s sin went unpunished. Fitzgerald suggested an alternative, but this too was rejected by Joseph Breen. He tried to redraft the script later in 1938, but the project dissolved.

Fitzgerald had systematically studied Hollywood releases, even filing plot synopses on index cards. Accordingly, the Infidelity screenplay we have shows an awareness of 1930s storytelling conventions: montage sequences, wordless scenes, and revealing visual detail. We learn that Nicolas’ ardor is cooling when we notice that he has stopped opening Althea’s letters. Fitzgerald’s acquaintance with current trends led him to a thumbnail characterization of Althea’s friend Alex:

He is the type played by Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth–handsome, attractive, worthy, thoroughly admirable, but somehow too heavy in manner to grip the sympathy of an audience if playing opposite a man of charm.

Occasionally, voice-over dialogue in the present is matched with images in the past, in the manner of Sturges’ “narratage” in The Power and the Glory. (See our entry here.) And the large-scale flashback structure, leaving a key action in the present suspended for nearly an hour, anticipates a mode of construction that would be common in the 1940s.

Despite its up-to-date air, the plot of Infidelity creaks a bit. It relies on a great many coincidences and introduces rather late a major menace, a sinister surgeon who seems slated to play the disruptive role of George Wilson in Gatsby. But what’s of special interest to us is a schedule of work that Fitzgerald sent to Stromberg during the planning stages.

Fitzgerald groups his scenes into clusters, and alongside each one he notes a date on which he expects to complete it. Since each scene usually runs only a couple of pages, the groupings present a feasible day-by-day timetable. These clusters of scenes are gathered into eight “sequences,” labeled with Roman numerals. In the 1930s, a “sequence” meant, according to screenwriter Frances Marion, “a series of scenes in which the action is continuous without any break in time.” Each of Infidelity‘s sequences presents a unified phase of the action and is more or less continuous in time, although there are some ellipses as well.

Here’s the news: Fitzgerald’s timetable assembles the sequences into acts. Sequences I through IV are labeled “FIRST ACT 45 pages.” Sequences V through VIII are labeled “SECOND ACT 50 pages.” Sequence VIII is continued to form “THIRD ACT 25 pages.”

The first act establishes the loveless marriage and launches the flashback. While Althea is away, Nicolas re-encounters Iris. Meanwhile, as Althea and her mother are on their way home, they conveniently run into her old beau Alex. Their departure for the United States ends this setup. In the screenplay Fitzgerald has typed: “The First Act may be said to end here.”

The second act develops the conflict to a point of crisis. Althea returns a week early to find Iris at breakfast with Nicolas. She resigns herself to a loveless union. Back in the present, he plans the party and at the instigation of Althea’s mother Alex starts to woo her. But he abandons Althea, and by chance she’s found by Dr. Borden, whom she starts kissing. In the notes for Sequence VIII, Fitzgerald cryptically ends the act on an alternation between the couples:

CUT TO husband and back to old beau [Alex]

[Alethea] with beau [Alex]

Crisis with beau and switch [to the surgeon, Dr. Borden?]

CUT TO husband

After presenting this alternation in scenes, the manuscript concludes:

Full shot of a bedroom, large and luxurious like everything else in this house. Soft lighting, everything covered with cloth or canvas.

Nicolas Gilbert is standing in the middle of the floor.

Close shot of Nicolas.

This is presumably the end of the passage labeled “CUT TO husband.” In the Stromberg schedule, this last portion marks the end of Act Two. Act Three isn’t in the canonical version of the screenplay.

A couple of final points about the structure. Although the screenplay is estimated at 120 pages, its proportions don’t conform to the Field paradigm. At 25 pages or minutes, the third act is short. This is a characteristic of both modern and older Hollywood climax sections. But Act One was projected to be very long at 45 pages, and Act Two approximates it at 50. Fitzgerald’s layout is perhaps more characteristic of a stage play, which can afford a longish exposition and equivalent second act. In the script version we have, both acts run equivalent page lengths.

Fitzgerald may have expected some trimming and compression at later stages. In The Producer, Brooks’ protagonist notes that a 120-page script would usually be cut down to 90 minutes because exhibitors wanted films at about that length. It’s true that few films of the studio era run to two hours.

Set aside brute measurements. What, in Infidelity, makes an act a coherent unit? Not a specific span of time. Act One breaks off partway through the flashback, and Act Two ends before the evening party does. The first act ends when we know a crisis is coming: Althea is returning home early and hasn’t told Nicolas, whom we’ve seen flirting with Iris. Act Two ends at another high point. Nicolas confronts the emptiness of his life without his wife, and nearby Althea is heedlessly making love to a stranger with dubious designs. We could easily imagine the script as a stage play, with a curtain ringing down on each of these teasing situations.

In sum, we have one clear-cut case of a studio screenwriter laying out his plot in three acts. We can’t generalize from a single instance, of course, and we would need many more pieces of evidence to consider this a widespread writing strategy. Perhaps Fitzgerald isn’t typical. Did his relative inexperience as a screenwriter make him rely on a theatrical template that others could do without? Did he employ it more as a rhetorical device to convince Stromberg that the plot was firmly constructed? Still, taken with the reminiscences of Dunne, Wilder, et al. and the sketchy mentions we have in production records, the Infidelity project suggests that some conception(s) of three-act structure were operative in the studio period.

Needless to say, we’ll need even more evidence before we can begin to consider whether the filmmakers’ craft practice matches the structural patterns that today’s analysts disclose in the films. The search continues!

The Fitzgerald outline is reproduced on pp. 161-162 of Aaron Latham, Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood (Viking, 1971). This book is not only a stimulating account of the novelist’s Hollywood years but also a helpful view of the movie colony’s culture. My discussion relies upon the version of Infidelity published in Esquire 80, 6 (December 1973), 193-200, 290-304. It is available in a digitized version here. The original manuscripts are in the University of South Carolina library.

Philip Dunne’s remarks about three-act structure are in Pat McGilligan, Backstory (University of California Press, 1988), 158. Billy Wilder’s remarks come in George Stevens, ed., Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age (Knopf, 2006), 316. (In the same interview Wilder claims that Some Like It Hot has four acts.) Richard Brooks’ The Producer (Simon & Schuster, 1951) is worth reading for its almost documentary survey of the process of production at the period. Lewis Herman’s Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films (World, 1952) is an unusually detailed guidebook.

On Wallis’ memo about Casablanca‘s second act, see Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Visual Design Program of Casablanca,” Post Script 9, 3 (Summer 1980), 38. For Zanuck’s comments see Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years at Twentieth Century-Fox, ed. Rudy Behlmer (Grove, 1993), 173, 226. Seitz’s remark to Sturges about The Great Moment is quoted in James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt, Brace, 1982), 172. There’s more discussion in our blog entry on The Great Moment.

I take Frances Marion’s definition of “sequence” as a bundle of scenes from her How to Write and Sell Film Stories (Covici-Friede, 1937), 373. Tamar Lane offers a comparable definition in his New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936), 123. Interestingly, Lane adds that some scenarists think of each sequence as moving toward a high point, like an act in a play; but this seems only a rough analogy, and the comparison entails that a script would have several more “acts” than three. Steven Price suggests that the “sequence” as an extended script segment emerged in the silent period and hung on in some sound screenplays; see A History of the Screenplay, especially 63, 115-116, and 153-157. At the same time, “sequence” could refer to a single brief segment, as in “action sequence” or “montage sequence.”

Thanks to Steven Price and Claus Tieber for correspondence about act structure. Claus has a relevant case study of Grand Hotel, “‘A Story Is Not a Story But a Conference’: Story Conferences and the Classical Studio System,” in Journal of Screenwriting vol. 5, no. 2 (2014): 225-237. More generally, I’m grateful to researchers at the Screenwriting Research Network for what I’ve learned from their conferences in Brussels in 2011 and in Madison in 2013.

Other entries on this site have considered act structure. Kristin explains her model, based on goal formulation and injections of new information. She expands on this as it affects character subjectivity and point of view. I illustrate her model with reference to what is supposedly the most wayward and narratively fragmented modern genre, the action picture. I offer some general reflections on how the four-part structure informs not only current films but best-selling novels. For a more general discussion of the dimensions of film narrative, you can download this chapter from my Poetics of Cinema. Also, too: there’s the precept that form follows format. Finally, I consider modern trends in screenplay construction, including act structure, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

After a while you see the triplicate scheme everywhere. In Case History of a Movie (1950), p. 30, Dore Schary says that Charles Schnee turned in the script of The Next Voice You Hear in thirds. Acts? I’ll have to get back to you.

P.S. 19 May 2014: In reply to this post, Greg Beal comments that my discussion of rejecting screenplays based on Field’s plot points is inaccurate.

My claim was, I now think, an overstatement. I should not have suggested that the absence of canonical plot points would be sufficient to doom a screenplay. Naturally, I realize that the analyst would still be obliged to write fuller coverage. I meant simply that the Field template could set up expectations that the script wasn’t written to standard. Other factors would surely be taken into account in a final decision. The larger point, that three-act structure along Field’s lines shapes analysts’ judgment, remains to be determined.

My most concrete evidence for the saliency of the three-act, plot-point model in this production context comes from two manuals by story analysts. T. L. Katahin’s Reading for a Living: How to Be a Professional Story Analyst for Film and Television (Blue Arrow, 1990) recommends that analysts look for three acts, including a ten-page initial setup followed by a development and two further acts that forward the protagonist’s goals. But Katahin doesn’t propose exact page counts for further twists.

More specific is Jennifer Lerch’s 500 Ways to Beat the Hollywood Script Reader: Writing the Screenplay the Reader Will Recommend (Simon and Schuster, 1999). In following the three-act layout, she suggests that Act One, the setup, be consummated between pages 20 and 30 (ideally consisting of two scenes 10-15 pages each). Act 2, as per Field, is said to run long, up to pages 80-90, and typically consists of four to eight sequences (each 10-15 pages or so). This act is said to lead to a point of no return, the pivot-point for Act 3.

Lerch, who was a professional story analyst for the William Morris Agency for eight years, claims, “Your script’s setup can literally make or break your project in the Hollywood Reader’s eyes, particularly at some companies that instruct readers to stop at page thirty of a script if it looks substandard. You may have a great second act and climactic sequence, but Hollywood will never see it unless you give it a savvy setup” (91). Passages like this one led me to think that the Field template weighs quite strongly in analysts’ judgment. But I’ve never supervised story analysts, so I welcome Greg’s expert comment on the matter.

P.P.S. 20 May 2014: More information on Fitzgerald’s Infidelity screenplay and its act breaks. In a letter to Hunt Stromberg dated 22 February 1938, Fitzgerald wrote:

The first problem was whether, with a story which is over half told before we get up to the point at which we began, we had a solid dramatic form–in other words whether it would divide naturally into three increasingly interesting “acts” etc. The answer is yes. . . .

This point, the decision to sail, also marks the end of the “first act.” The “second act” will take us through the seduction, the discovery, the two year time lapse, and the return of the old sweetheart–will take us, in fact, up to the moment when Joan [later, Althea] having weathered all this, is unpredictably jolted off her balance by a stranger. This is our high point–when matters seem utterly insoluble.

Our third act is Joan’s recoil from a situation that is menacing, both materially and morally, and her reaction toward reconciliation with her husband.

Evidently the timetable reprinted in Crazy Sundays was prepared after this letter was sent. This letter is printed in F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (Scribners, 1994), 348-349.

P.P.P.S. 30 May 2014: I always enjoy getting correspondence from readers, and I must catch up by noting some other responses I’ve received. David Cairns, whose wonderful blog Shadowplay is always worth checking on (his latest post is on Hannibal, the TV show), writes with this comment:

Hold Back the Dawn (1941).

Back in THE Place

View of Hong Kong harbor from the Convention and Exhibition Centre. Above, the flag of the People’s Republic of China; below, the Hong Kong flag bearing the Bauhinia emblem. According to official protocol the national flag must be larger and be mounted more prominently.

“For us, Hong Kong will always be the place.”

Chuck Norris, The Octagon (1980)

DB here:

After missing two editions because of some minor health problems, I’m back in Hong Kong for their annual festival. As customary, it kicked off with the Filmart, now the biggest film market in Asia. It gathers producers, distributors, and financiers for discussions and dealmaking. There are panels, equipment demos, and displays of media items for sale. There’s the Hongkong-Asia Film Financing Forum, a competition that funds planned projects. (This year’s winners are here.)

Some booths are huge. The TVB display was towering, dwarfing the TV chat show being shot underneath.

Since its founding in 1997, Filmart has been so successful that it spawned an umbrella event. The Hong Kong Entertainment Expo, now in its tenth year, is a jamboree for the international entertainment industry, including music and digital entertainment of all sorts.

Filmart is now very big. This year it packed in over 760 exhibitor stalls from over 30 countries (including Brunei and Malta). It attracted over 6500 attendees, and most, unlike me, were there to buy and/or sell films, TV shows, and video games.

National film organizations use Filmart to coax production into their territory. Government agencies like KOFIC can put producers in touch with prime locations and service firms.

The opening reception was graced by Chief Executive C. Y. Leung, who while extolling the rule of law in the territory did not mention the recent violent attack on a major journalist. A characteristically blank-faced Leon Lai looked on. In the crowd, you might also meet Bruce Lee, or at least his avatar.

On the market floor, a Chinese vampire squared off against Donnie Yen, immortalized by Madame Tussaud.

Who would win in a face-off? The movie is probably being shot as we speak.

China ahead

Out of Inferno (2013).

The big news this year was, as ever, mainland China. By any measure it just keeps growing. Back in 2012 it became the world’s second-biggest market, yielding $2.74 billion in box-office grosses. (US and Canada were at $10.8 billion.) In 2013 Chinese grosses were $3.6 billion, a growth of 25%. (North American grosses grew only about 3%.) In tandem, the number of exhibition sites expanded hugely. China added over 5,000 screens in 900 new multiplexes, yielding a total of 18,195 screens. That is still remarkably few for such a populous country; North America has over twice that number. So we can expect still further growth. More generally, another sign of the times was that last year Asia-Pacific became the most lucrative region outside North America, and of course China is the centerpiece of that.

You see the China syndrome in the films as well. For several years Hong Kong producers and directors have partnered with mainland talent and business groups. Two of last year’s best Hong Kong films, Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Drug War and Wong Kar-wai’s Grandmaster, epitomize cross-border initiatives, mixing HK and PRC stars in stories that hold appeal for both audiences.

A new wrinkle: Now even films that might seem purely of Hong Kong interest credit major Chinese companies as coproducers, and they may feature mainland stars. Tim Youngs, local HK film expert, suggests that because some big-budget Chinese films haven’t succeeded in Hong Kong, mainland investors may be interested in financing small films that will catch on in the territory.

Yet some films persist without mainland financing. An example I saw at Filmart is the modest indie Dot 2 Dot, by first-time director Amos Why.

The story is rooted in local history and geography. Chung, returning from Canada to take a job in a design firm, recalls how much he enjoyed connect-the-dots puzzles as a boy. Now he discreetly puts up speckles on walls, marking sites that were significant to him and his city. Xue, a young teacher, discovers them, puzzles them out, and draws out the abstract patterns that Chung embedded in them. When he spots her graceful graffiti he determines to find who has cracked his code. What gives the story contemporary currency is the fact that Xue has emigrated from the mainland and is teaching Mandarin to Hong Kongers, and she is played by Meng Tingyi.

Dot 2 Dot interrupts its lovers-at-a-distance plot with images from Hong Kong’s past. Xue’s supervisor, an elderly teacher, and Chung, a nostalgia buff who treasures his childhood comics, recall moments in local history, such as when the Daimaru department store closed after a gas explosion. The émigré Xue, in finding her way around this imposing city, comes to appreciate its past. Eventually we learn through a degrees-of-separation device that both Chung and Xue have shared Hong Kong kid culture–two dots, in effect, waiting to be connected in adulthood. Those interested in allegory could see here a claim that for decades, China’s modern popular culture has been imported from Hong Kong, and that fact fosters cross-border bonds.

On a bigger budget there are other more or less “pure” Hong Kong films–in tone and genre, despite mainland backing–being made. Even the cockeyed English title Out of Inferno (2013) brings back the 1980s and 1990s, as does the premise. Two brothers dedicated to firefighting fall out; one (Lau Ching-wan) becomes obsessed with his job, the other (Louis Koo) leaves to form a company specializing in modern fire-protection equipment. When a skyscraper catches fire during a party demonstrating the equipment, Koo and Lau’s pregnant wife, along with many others, are trapped inside. The brothers must reconcile, inside and outside, to save innocent lives. In short: Towering Inferno + Backdraft + Johnnie To’s Lifeline. Indeed, certain shots and the very presence of Lau Ching-wan, recall To’s genre masterpiece. So what’s new? Well, it’s set in Guangzhou and it’s in 3D.

Out of Inferno comes to us co-funded by the HK company Universe and the mainland company Bona. It grossed about US$2.6 million in Hong Kong and over $20 million in China, which says all you need to know about the relative power of the two markets.

Nobody I respect seems to like this movie. Most critics have written off the directors, the brothers Danny and Oxide Pang, as hacks. Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm states the case against. Granted, the film is routine in many ways and can’t match Lifeline, but I enjoyed its almost unceasing bursts of clear, cogent action. I began to realize that one benefit of a firefighting movie is that rooms can explode, ceilings and floors can collapse, and elevators can stop or plunge–at any time, whenever you something to goose a scene. After all, it’s a fire, right? Who can predict what a fire will do? In 3D, many shots were splendid, and I will watch Lau Ching-wan doing sullen integrity in nearly anything. Still, Tim Youngs alerts me (so I alert you) to another action-filled firefighter movie, As the Light Goes Out–not screened at Filmart, not yet available on disc, and with more admirers, at least in my vicinity, than Out of Inferno.

A future for Retro

The White Storm (2013).

Universe and Bona, who seem to team up for blockbusters, offered a more delirious example of the Hong Kong flavor in The White Storm, which also screened at the Filmart. It’s another exercise in mixing. We have Bullet in the Head: three boyhood friends undergo a harrowing trip to wilder Asia, expending much sweat and tears, and even more blood. We have Infernal Affairs too, with the deadly game of undercover work and the possibility that a Triad mole has infiltrated the police. The three buddies consist of the familiar pairing of Lau Ching-wan and Louis Koo, along with the ever-dependable Nick Cheung as the apparently weakest member of the trio.

Unusually long at nearly 140 minutes, The White Storm (the title refers to the heroin plague that has descended on Hong Kong) is really three movies in one. The first centers on Koo in the now-familiar role of the cop who wants to come in from the cold. After a frantic drug bust gone wrong, he’s forced to return to the underworld and lead his comrades to a Thai kingpin. The second stretch takes place in Thailand. There after a savage assault on the dealer’s compound, our three are captured. The dramatic weight shifts to Lau, who must choose to kill either Koo or Cheung. His decision gains complexity because we know something he doesn’t about his partners’ loyalty. The film’s last portion returns to Hong Kong, with a few surprises and a bloody casino finale.

While building suspense in the Infernal Affairs mode–will the gang discover the mole in their midst?–director Benny Chan also tries to recover the searing romanticism of Woo’s heroic bloodshed films. As far back as The Big Bullet (1996) he showed a flair for shocking, precise action, and his Jackie Chan vehicle New Police Story (2004) is an exhilarating piece of work. Benny Chan shows his skill in each of the three sections’ violent set-pieces. Add in the 1980s-1990s Hong Kong excess–bodies thrown into pools of crocodiles, a sexy transsexual, outrageous haircuts–and you have an almost purely retro exercise.

Another throwback is the shameless but stirring tear-jerking moment in which the three men comfort Cheung’s dying mother. She thinks that Lau is her son, back from study abroad with his buddies. They spontaneously accept her delusion, each pretending to be another member of the trio. The film’s play with false identities turns melancholy, and in comforting her the men apologize, obliquely, to one another. Chan’s use of singles and two-shots deftly traces out the flow of feeling, as the men exchange glances and Cheung starts to weep in shame.

The old Hong Kong cinematic energy resurfaced in another, stranger film, Fruit Chan’s new release The Midnight After. It’s based on a popular internet novel by Pizza (yes, you read that right). The premise is apocalypse, the time is now. A minibus driving from downtown Hong Kong to the New Territories passes through a tunnel and emerges into an urban landscape from which everyone seems to have vanished. A mass extinction? An evacuation? A time warp? The mystery deepens after we get an occasional glimpse of dark figures in protective gear monitoring the frantic efforts of the survivors to make sense of their fate. Some of the passengers die–crumbling to bits, suffering giant boils, bursting into flame. Even a compassionate bicyclist is drawn into the desperate struggle for survival.

A Hong Kong director often asks us to take his or her film as reflecting a general mood in the territory. Fruit Chan says:

It feels as though Hong Kong is suffering the worst of times. People’s lives, people’s businesses and the political climate are all seriously depressed. The impact hit us harder than anything else in the past century. Through The Midnight After I’d like to tell the est of the world something about the problems that Hong Kong faces in this period of social upheaval.

The tone, as well as the plethora of familiar landmarks, may give the film some local resonance. More broadly, the film also joins a tradition of horror-fantasy that hearkens back to classic Hong Kong movies about the supernatural and even dystopian exercises like The Wicked City (1992). The latter was rendered with typical Tsui Hark brio, though, and The Midnight After is more sober and straightforward, at times perilously close to flat. Nor does it have the conciseness and growing creepiness of Chan’s Dumplings (2004).

I didn’t find The Midnight After particularly compelling. The characters are viewed from the outside and don’t solicit much sympathy; they’re mostly collections of types and tics, including a mysterious young woman who is given I-may-be-a-demon treatment by the expedient of momentarily billowing hair. As usual when a Cantonese film doesn’t know what else to do, it sets its characters screeching, quarreling, running around, and punching. Moreover, I couldn’t figure out what made the unfortunate victims die in different ways. And what’s behind the mysterious watchers? My friends say: “There aren’t any rules.” Maybe they’re right. But it’s fairly easy to pile on mysteries in your plot; the task is to tie them up in the end.

To be fair, we don’t really have the end. The film adapts only the first part of Pizza’s cybernovel, so perhaps everything will get straightened out in a sequel. What matters, for better and worse, is that many Hong Kong filmmakers still resort to Reboot mode.

You can read the trade papers’ Filmart daily publications here. Also visit Film Business Asia for many articles on deals announced at Filmart. Peter Martin reports on a panel on the Asian industry at Twitchfilm. Perhaps most important, Patrick Frater of Variety signals an important upcoming change in PRC distribution policy.

My information on the 2013 growth in Chinese screens is gleaned from David Hancock’s survey in of world exhibition in IHS Media and Technology Digest no. 504 (September 2013), 9-12. Additional information comes from Jeremy Kay’s CinemaCon report in Screen International and Patrick Frater’s account of screen expansion in Variety. Derek Elley offers a very thorough analysis of the contemporary Chinese industry in “Mainland Cinema’s New Maturity,” in Film Business Asia.

The trailer for Dot 2 Dot is here. Kozo, as you’d expect, has a nuanced review of The White Storm.

In other welcome news related to The Place, Grady Hendrix is back with Kaiju Shakedown. The inital entry is a full-blooded overview of the career of mystery auteur Jeff Lau.

P.S. 1 April 2014 (HK time): This entry has been revised to correct my original claim that Dot 2 Dot had some financing from the mainland. Director Amos Why wrote to explain that despite the credited participation of two companies based in Beijing, there was no investment from Chinese sources; the funding came entirely from Hong Kong. I thank Amos for the correction.

Smoke from a towering inferno? The creeping miasma of The Midnight After? No, just a low-lying cloud settling on Central after a rainstorm.

Agee & Co.: A Newer Criticism

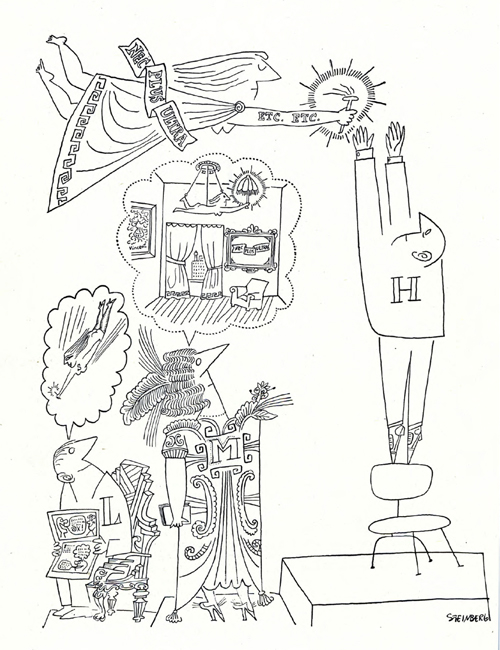

Saul Steinberg, “Lowbrow, Middlebrow, Highbrow”; Harper’s Magazine, February 1949.

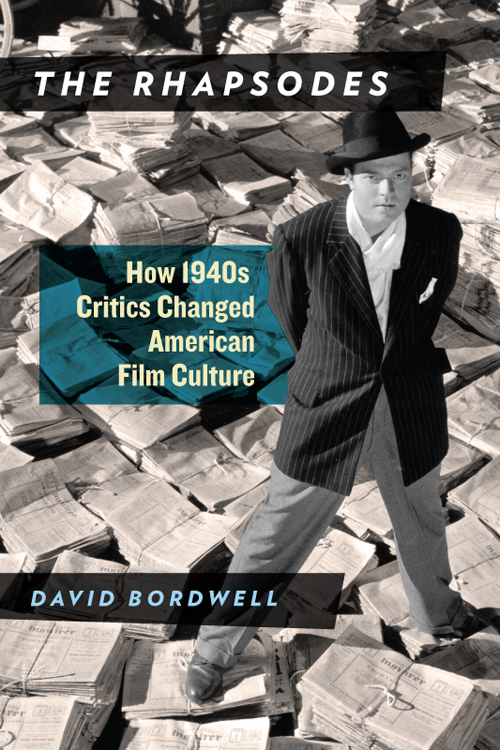

The original entry at this URL, published 9 February 2014, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

I explain the development of the book in this entry.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

Thank you for your interest!

Otis Ferguson and the Way of the Camera

The original entry at this URL, published 20 November 2013, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

I discuss the development of the book in this entry.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

Thank you for your interest!