Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Germany in autumn, in style

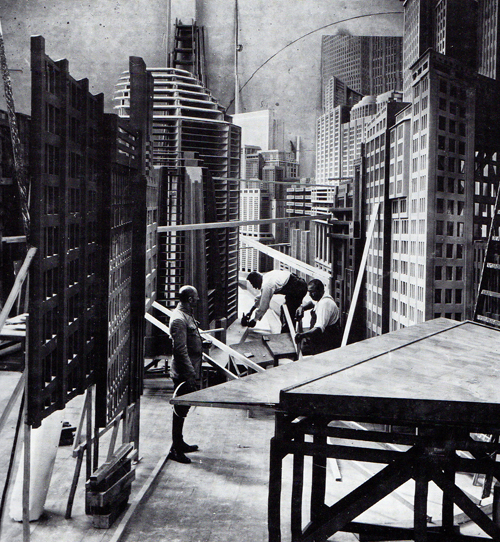

Shooting Frau im Mond (1929) at Neubabelsberg studio, Potsdam.

DB here:

Friends say that Berlin is now the most exciting city in Europe–a little too exciting, others say. I can’t prove either claim, but I can declare that I had a fine time last month during my second visit to Germany this year. Part of the fun was, as usual on many of our trips, finding tangible traces of film history.

Stylin’

Lobby space, Konrad Wolf Film School.

With Michael Wedel, I re-saw Hong Sang-soo film’s Turning Gate in the wonderful Arsenal theatre, part of the Deutsche Kinemathek. The Arsenal is run by Milena Gregor, another old friend (who happens to be Michael’s wife). On another night I also had a delicious dinner with filmmaker Christine Noll Brinckman and other friends. Then there was a pleasant lunch with another filmmaker, Carlos Bustamante (below), in his picturesque neighborhood.

But Berlin literally wasn’t the half of it. I visited Philipps Universität in Marburg, a charming university town. Part of the campus fronts onto the Lahn River, and it makes a charming place to relax.

After my lecture on 1940s Hollywood, my hosts Malte Hagener and Dietmar Kammerer took me out to dinner with their lively colleagues.

Most of my visit was spent in Potsdam, where I’d been invited by the Netzwerk Filmstil. This is a research team composed of several young professors teaching in German-language universities around Europe. Their focus is the exploration of style in audiovisual media–centrally film, but not ignoring television, video games, Internet pieces, and even surveillance and security videos. The two and a half days of the seminar were very stimulating. Michael Wedel, Chris Wahl, Malte, Dietmar, and Kristina Kohler gave illuminating papers on (respectively) digital sound, superimpositions, split screen, freeze-frames, and dance in silent film. The participants offered me good criticisms of my presentation, which explored how E. H. Gombrich’s explanations for stylistic change in visual art might apply (or not) to cinema.

Our seminar sessions were held in the remarkable Konrad Wolf Film School, a towering building crisscrossed by staircases and walkways. I visited it once before some years ago, and once more I admired its airy yet rectilinear architecture.

The stripped-metal look is offset by lots of glass–the light pours in from all directions–and a corner with plenty of plant life. As in our house back home, winged silhouettes on the windows keep bird-brains from flying into the glass.

I also gave a talk on film style during the 1910s at the monumental Filmmuseum Potsdam.

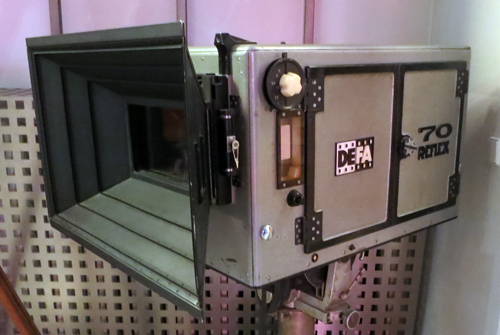

The museum holds a fine screening space and a fascinating collection of historic materials, including a Soviet-era 70mm camera.

The current exhibition was devoted to the rise of the film studio Babelsberg, not far away. The displays included scripts, set photos, production sketches, photos, and maquettes.

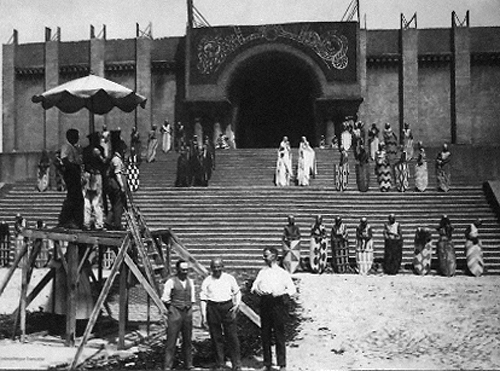

Have you seen this still of the great Cathedral set from the Nibelungen?

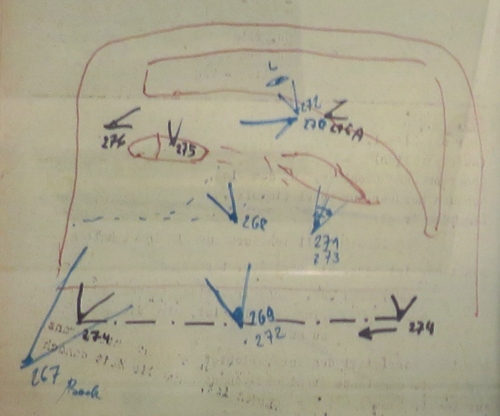

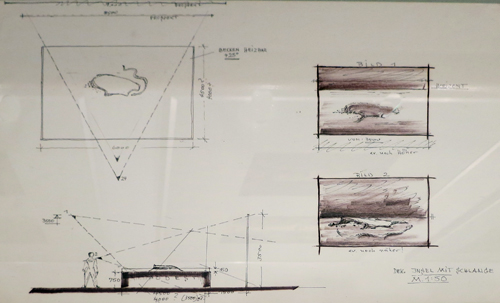

The tradition of fastidious planning created during the silent era persisted into the period of the German Democratic Republic. Each set design was marked up to show camera positions (numbered), lens lengths, and special-effects elements.

The Filmmuseum’s collection was only one reminder of the towering importance of Babelsberg, now celebrating its hundredth anniversary year. Luckily the studio was an easy walk from the Konrad Wolf school. One sunny day our host Michael Wedel took the Style Network on an insider’s tour.

Babelsberg’s birthday

The 1910s and 1920s saw many production facilities spring up in Germany. Films were made in Munich, Frankfurt, and other major cities, and the area around Berlin boasted a number of studios. But the Potsdam facility, initially called Neubabelsberg, became the most well-known, something like Europe’s answer to Hollywood.

Founded by the Deutsche Bioscop company, the studio began production in 1911 and released its first film, Totentanz (The Dance to Death), in 1912. That starred Asta Nielsen, whose popularity had already enriched Bioscop. In this story she’s attracted to a rather louche composer, as we see below. (Yes, that mass of black is mostly her hat.) Later, she slices the guitar strings in a fit of passion and glares out defiantly at us. As if our attention might wander.

Neubabelsberg was home to such classics as The Student of Prague (1913), the Homunculus series (1916-1917), Madame Dubarry (1919), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), The Golem (1920), and Genuine (1920). Fairly soon Bioscop merged with Erich Pommer’s Decla, and in 1921 the big company Ufa took over the facility and the resident firms. Ufa also had a studio in Tempelhof, a Berlin suburb, but the attention-grabber was Neubabelsberg, which became a sprawling complex of 350,000 square meters–the biggest studio in Europe.

Here Murnau shot Phantom (1922), as well as portions of The Last Laugh (1924). E. A. Dupont filmed some of Variety (1925) here, and Pabst shot all of The Loves of Jeanne Ney (1927) on its stages. Above all, Neubabelsberg helped sustain one of cinema’s great hot hands, the string of films Fritz Lang made in the 1920s: Destiny (1921), the Mabuse duo (19221-22), the Nibelungen saga (1924), Metropolis (1927), Spies (1928), and Woman in the Moon (1929).

The studio remained a powerful force across the next two decades, from The Blue Angel (1930) to the epic color production The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1943).

The partitioning of Germany after World War II put it the studio the eastern sector, and the new state-sponsored film company, DEFA (Deutsche-Film-A. G.), took over the facility in 1953. That made it what Ralf Schenk calls “the exlusive site of feature cinema production in the GDR until 1990.”

After the Wall came down, the Babelsberg studio revived itself as a facility for international productions. It has hosted films by Polanski (The Pianist, The Ghost Writer) and Tarantino (Inglourious Basterds; below, a set on the Babelsberg backlot). The Wachowskis have been loyal supporters, with Speed Racer, V for Vendetta, and most recently Cloud Atlas using the facility.

You can get a sense of the studio today by visiting the website, which presents it as a modern resource for world filmmaking. But its early years matter more to me. To walk these quiet pavements and to imagine following in the steps of Lang, Jannings, Dietrich, and other legends ought to thrill any cinephile. Seeing some streets named for the greats, Tarantino requested a street in his name. It’s apparently a dead end.

A new Babylon

In the cold winter of 1911-1912, Deutsche Bioscop built its first studio, a 45 x 60 foot “glass house”at Babelsberg.

Michael Wedel explains:

Not only was a special cement-less glazing developed for the glass, but even the supporting beams of the infrastructure had to be installed outside of the studio, so as not to spoil the sunlight. . . . In contrast to already existing glasshouse studios that had been “set up” in Berlin and Munich in multi-level apartment blocks and office buildings, the ground-level location of the new Bioscop building at Babelsberg had the advantage of trucks with props and sets being able to be driven through a sliding door directly into the glass studio. . . .

Michael again:

The ground floor of the immediately adjacent factory building accommodated wardrobe and prop rooms, a woodshop, art studio, and a canteen. On the first floor, the production company’s office, as well as the laboratory for developing negatives and positives, were set up. On the floor above was where one found the dry drums for developed film material, the room in which the films were edited, and the rooms where intertitles were prepared. Except for the costume department, which would be built systematically a few years later, Bioscop oversaw a completely integrated film studio, which made it possible to perform most stages of film production on-site.

Later in the 1910s Guido Seeber, the cinematographer and all-around creative genius who had planned the Babelsberg plant, began to use supplemental artificial light. But this glass house and its bigger brother, built later, were relied upon throughout the silent era. A closed unit lit entirely by artificial light wasn’t built until 1926. Appropriately huge, it was called the Great Hall and eventually renamed the Marlene Dietrich Stage.

The Frau im Mond production shot atop today’s entry was taken in the Great Hall. Here’s another picture of the interior in the late 1920s. In both shots, those little figures on the far right are men.

On our stroll we caught glimpses of some filming taking place in a parking lot.

Not quite as glamorous as the behind-the-scenes action on–oh, let’s say Metropolis.

We ended our unofficial tour with a quick look at the backlot, which can be redressed to be almost any European city you like.

Movie magic, the Dream Factory: the rationalist side of me rejects these catchphrases as mere mystification. Filmmaking is hard thinking and hard work. But it’s tough to be purely rationalist when you’re facing an illusion machine that has thrilled audiences worldwide for a hundred years. If you see Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters, spare a thought for the tradition of Germanic lore that made it possible–and the hard work of the thousands of men and women who built a cinematic metropolis here.

Thanks to all my hosts and colleagues for making my trip to Germany, however short, intense and enjoyable.

Noll Brinckmann’s films and writings are available, at least in part, in this edition. A sample of Carlos Bustamante’s recent work is available online here.

For a fairly detailed timeline of Babelsberg’s history, see this page of the Filmmuseum site. When spring comes, you can take a studio tour (German language only) or visit the nearby theme park.

My quotations come from Michael Wedel, ChrisWahl, and Ralf Schenk, 100 Years Studio Babelsberg: The Art of Filmmaking (teNeues, 2012). This is that rare coffee-table book whose historical texts (footnotes included) are as valuable as the luxurious photos. The book, in an English/German edition, is available from the Filmmuseum and from Amazon.de.

This post gathers information from Hans-Michael Bock and Michael Töteberg’s encyclopedic Das Ufa-Buch (Zweitausendeins, 1992). Also helpful was Klaus Kreimeier’s The Ufa Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company, 1918-1945 (Hill and Wang, 1996).

We hadn’t planned it this way, but Kristin’s previous entry discusses several recent DVD releases of German classics. I wrote a little bit about Totentanz (1912) here.

My lecture at Potsdam, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” was a new version of a talk I’ve been giving for the last couple years to whatever audiences of innocents that fate has flung my way. Alert filmmaker Erik Gunneson, who prepared our video essay on constructive editing, is currently turning this talk into a video lecture. We hope to put it up on this site early in 2013.

The stylish Film Style Mafia, Neubabelsberg, November 2012.

10 Dec 2012: Thanks to Antti Alanen for two spelling corrections!

Is there a blog in this class? 2012

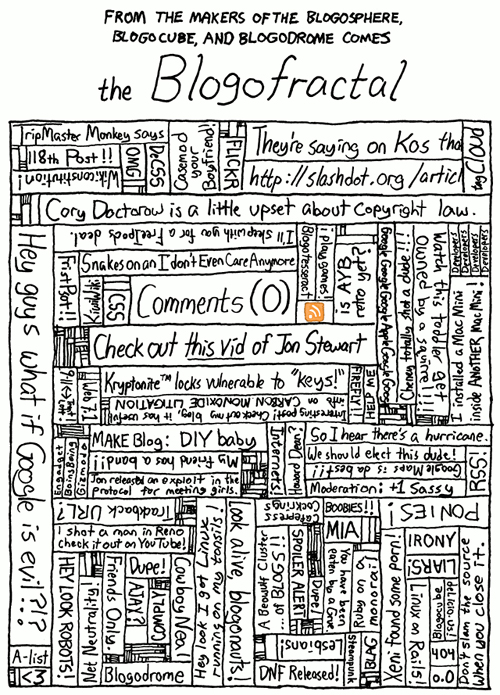

From the xkcd webcomic

Kristin here:

August is here, and many film teachers are back from summer research trips and starting to prepare syllabi for the fall. Those who are using the new tenth edition of Film Art will have noticed that tucked away in its margins are references to blog entries relevant to the topics of each chapter. But since the new edition went to press, we’ve kept blogging. As has become our tradition, we offer an update on blogs from the past year that teachers might want to consult as they work on their lectures or assign their classes to read. Even if you’re not a teacher, perhaps you’d be interested in seeing some threads that tie together some recent entries.

For past entries in this series, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011.

First, some general entries about the blog itself and the new edition of Film Art. On our blog’s fifth anniversary last year, we posted a brief historical overview of it. That entry contains some links to some of our most popular items. If you’re new to the blog and want some orientation, it could prove useful. Maybe students would be interested as well. At least the photos reveal our penchant for Polynesian adventure and shameless pursuit of celebrities.

In case you haven’t heard about the changes we made for the new Film Art, including our groundbreaking new partnership with the Criterion Collection to provide online examples with clips from classic movies, there’s a summary post available.

And here’s another entry on the new edition, discussing a new emphasis on filmmakers’ decisions and choices.

Now for chapter-by-chapter links.

Chapter 1

Understanding the movie business often means being skeptical of broad claims about supposed trends. We explained why the widespread “slump” of the movies in 2011 was no such thing in “One summer does not a slump make.”

Trying to keep one step ahead of students (or just keep up with them, period) on the conversion to digital projection and its many implications? Our series “Pandora’s Digital Box” explores many aspects:

In multiplexes: “Pandora’s digital box: In the multiplex”

In small-town theaters: “Pandora’s digital box: The last 35 picture show”

At film festivals: “Pandora’s digital box: At the festival”

On home video: “Pandora’s digital box: From the periphery to the center or the one of many centers”

In art-houses: “Pandora’s digital box: Art house, smart house”

Challenges to film archives: “Pandora’s digital box: Pix and pixels”

How projection is controlled from afar: “Pandora’s digital box: Notes on NOCs”

Problems introduced by digital: “Pandora’s digital box: From films to files”

Another case study of a small-town theater: “Pandora’s digital box: Harmony”

Or you can pay $3.99 and get the whole series, updated and with more information and illustrations, as a pdf file.

3D is a technological aspect of cinematography, but it’s also a business strategy. We explore how powerful forces within the industry used it as a stalking horse for digital projection in “It’s good to be the King of the World” and “The Gearheads.”

Independent films can be the basis for blockbuster franchises. “Indie” doesn’t always equal “small,” as we show in “Indie blockbuster franchise is not an oxymoron.”

One of the top American producers and screenwriters of independent films is James Schamus, head of Focus Features. We profile him in “A man and his focus.”

3D is probably here to stay, but it may have already passed its peak of popularity, as we suggest in “As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?”

The late Andrew Sarris played a crucial role in shaping the “auteur” theory of cinema. We talk about his work in “Octave’s hop.”

Chapter 2 The Significance of Film Form

“You are my density” is an analysis of motifs in Hollywood cinema, including a detailed look at a scene from Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

We offer a narrative analysis of a Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, a film many viewers found difficult to follow on first viewing, “TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed.” A follow-up, “TINKER TAILOR once more: Tradecraft,” concentrates on the adaptation of Le Carré’s novel.

A tricky narrative structure in Johnnie To’s Life without Principle called forth our entry, “Principle, with interest.”

In “John Ford and the Citizen Kane assumption,” we consider the possibility that Kane, analyzed in this chapter, might not be the greatest movie ever made.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

For some reason teachers (and apparently students) always want more, more, more on acting, the most difficult technique of mise-en-scene to pin down. “Hand jive” talks about hand gestures, which in the past were used a lot more than they are now. “Bette Davis eyelids” takes a close look at the subtleties of Bette Davis’ use of her eyes.

“You are my density,” already mentioned, offers several examples of dynamic staging in depth.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style as a Formal System

We have posted two entries dealing with form and style, specifically experimental artifice in 1940s Hollywood. These could be of interest to advanced students. “Puppetry and ventriloquism” deals in general with the topic, while “Play it again, Joan” looks at scenes that replay the same action or situation. The latter contains an analysis of a lengthy scene of Joan Crawford performing that could be useful in discussing staging and acting for Chapter 4.

Chapter 9 Film Genres

If you teach a unit on genre and choose to focus on mysteries, “I love a mystery: Extra-credit reading” gives some historical background information on the genre in popular literature and cinema.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

“Solomonic judgments” centers on the gorgeous experimental films of Phil Solomon.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

Our discussion of Tokyo Story in Film Art could be supplemented by this brief birthday tribute: “A modest extravagance: Four looks at Ozu.”

Chapter 12 Historical Change in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

Last September I found an extraordinary little piece of formal and stylistic analysis using video, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912. A Spanish film student, Aitor Gametxo, had displayed the staging and cutting patterns of Griffith’s Biograph short, The Sunbeam, by laying out the shots in a grid reflecting the actual spatial relations among the sets and running the action in real time. If you teach a history unit or just want an elegant, clear example of how editing of contiguous spaces works, this is a wonderful teaching tool. Classes may be particularly intrigued that a student was able to put together something this insightful. Plus The Sunbeam is a charming film that would probably appeal to students more than a lot of early cinema would. See “Variations on a Sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film.” Gametxo’s film also provides an elegant example of how editing of adjacent spaces works and could be a useful teaching tool for Chapter 6.

Teachers showing a Georges Méliès film might have their students read “HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to George Méliès,” which has some background information on the career of this cinematic conjurer.

German silent film was the focus of “Not-quite-lost shadows.”

Not strictly on the blog, but alongside it, is a survey of how developments in film history generated changes in film theory. The essay is “The Viewer’s Share: Models of Mind in Explaining Film.”

Further general suggestions

Looking for some new and interesting films to add to your syllabus? We cover quite a few in our dispatches from the Vancouver International Film Festival 2011: “Reasons for cinephile optimism,” “Son of seduced by structure,” “Ponds and performers: Two experimental documentaries,” “Middle-Eastern crowd-pleasers in Vancouver,” and “More VIFF vitality, plain and fancy.”

Or if you seek information on historical films newly available on DVD, we occasionally post wrap-ups of recent releases, including a cornucopia of international silent films. See “Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings.”

We have also carried on our tradition of a year-end ten-best list—but of films from 90 years ago. Not all the films on our list for 1921 are on DVD, but most are: “The ten best films of … 1921.”

Every now and then we post an entry pointing to informative DVD supplements that might be useful teaching tools. It’s surprising how few of them go beyond a superficial level where the actors and filmmakers sit around praising each other: “Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something.”

Digital projection, there and here

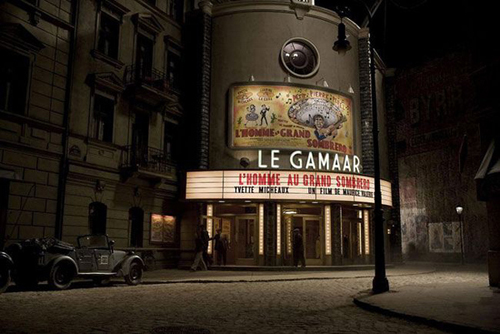

Galeries Cinéma banner, Brussels, 2012.

DB here:

The Cinéma Arenberg, in the splendid Galerie de la Reine, has long been a mainstay of Brussels film culture. Since 1939, the lovely Art Deco theatre was what we Americans call an art-house. Over the years Kristin and I visited the city, the Arenberg’s autumn and spring schedules featured recent releases, but every summer the programmers plunged into plucky repertory programs. While the multiplexes ran Hollywood blockbusters, the Arenberg provided 90 or so classics and little-known releases under the rubric of Écran Total. It was here, for example, that I saw von Trier’s The Kingdom and resaw Vanishing Point. Four years ago I left a little note about the three titles I watched during my last day in town: India Song, Serpico, and Darjeeling Limited. That trio gives you a sense of how varied and interesting the programming was.

The Arenberg closed down at the end of 2011, but the cinema has reopened under new management as Galeries Cinéma. It didn’t sponsor an Écran Total season this year. Instead it offered brand-new releases on its three screens, along with some children’s programs.

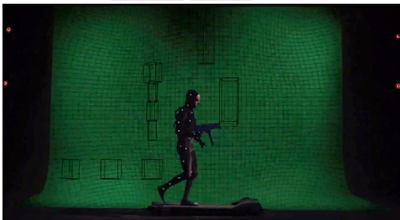

Most notable for me this time was Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. Whatever you’ve heard about this film is probably accurate. I found it an exhilarating, frustrating, and continuously provocative descent into Surrealist role-playing. It’s a tour of cinema genres and an anthology of bits of other movies, from Marey to Franju, and not forgetting Carax’s own. Especially evocative were the poetic fusions, such as the way that the body stocking Oscar dons for digital motion-capture evokes both ninja outfits and the leotards of Feuillade’s Vampires. Carax films Oscar’s SPFX exercise in a way that connects Muybridge to video games and recalls the exuberantly spasmodic scene in Mauvais Sang in which Denis Lavant races madly down the street to the accompaniment of David Bowie’s “Modern Love.”

Whether you find Holy Motors infuriating or beguiling, you won’t forget it.

Exquisitely shot on digital capture, Carax’s film was given crisp, bright digital projection at the Galeries. And speaking of digital projection. . . .

The new issue of Film History, devoted to digital technology’s impact on filmmaking and film culture, includes Lisa Dombrowski’s article “Not If, But When and How: Digital Comes to the American Art House.” It’s a very fine survey of all the issues facing the art-film community at this moment. Lisa reviews the major technological and financing conditions before going into depth on a case study of three art theatres in Miami. The author of a very good book on Samuel Fuller, Lisa knows how to tie together industrial and aesthetic issues skilfully.

Another young scholar, this one at the Free University of Brussels, has concentrated on the digital transition in Europe. Since 2005 Sophie De Vinck has been studying how the conversion of theatres fits into European film policy. The result was her 2011 thesis, “Revolutionary Road? Looking back at the position of the European film sector and the results of European-level film support in view of their digital future.” The thesis, running to a whopping 769 pages, is an immense resource, and not just for people interested in digital cinema. Sophie surveys the history of national and international support of the Western European film industry, from production through exhibition, and she provides both a broad context and very specific analysis.

Part of her argument is that the “diversity” aimed at by subsidized filmmaking hasn’t been matched by diversity in audiences. But digitization offers a new chance to show films outside the dominant forms of commercial cinema and perhaps attracted new sectors of the public. “Every innovation usually brings with it possibilities for new or smaller sector players to strengthen their competitive position.” Her examination of how digital conversion affects small and art-house venues provides a complement to Lisa’s research.

I wish I’d known about Sophie’s thesis when I was writing the blogs that became Pandora’s Digital Box, but at least I can signal her work now. Best news of all: Sophie has generously made “Revolutionary Road?” available under a Creative Commons license here as a pdf. Full of valuable statistics and well-honed observations, her work helps us understand how the contemporary European film industry has survived and sometimes flourished over the last fifty years.

Cinema Arenberg, Brussels, 2008. The original design of the curved doorway and neon sign was restored in 2005-2006.

The indispensable site Cinema Treasures has a brief entry on the history of the Cinéma Arenberg/ Galeries. More extensive information can be found in Isabel Biver’s luxurious survey, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins, which I wrote about in an earlier entry.

P.S. 1 August 2012: I just learned from Gabrielle Claes that Giovanna Fossati’s book on digital restoration in film archives, From Grain to Pixel, is now available for free in pdf form here. It’s well worth reading.

Orpheum descending

State Street, Madison, Wisconsin, 1927.

DB:

When it comes to film culture, Wisconsin yields to no one in weird-assery. I’ve chronicled Mad City Movie Mania on other occasions (here and here), and a current flap has just added to the annals of the addled.

It revolves around Madison’s Orpheum Theatre, a 1927 movie palace that has gone through many incarnations. In recent years it’s become mainly a music venue, but it was also fitted out with a restaurant and still showed the occasional art movie. Until it was shut down last month.

The problem is that after several years of confusion, feuding, moving money around, petty spite, and general dodginess, nobody knows exactly who owns the Orpheum. Is the owner Henry Doane, local restauranteur, who for years was publicly considered the purchaser? Is it Eric Fleming, Doane partner who became anything but silent? Is it Gus Paras, wealthy landlord and restauranteur, who bid a couple of million for it at auction last month? What of the woman who acquired Fleming’s share of the building? And the shadowy figure who made off with a plastic bag holding $175,000—how does he fit in?

“I’ve never done anything to deserve the negative treatment that I’ve been getting. I’m very compromising. I’m willing to do whatever it takes to make things work—as long as it’s profitable.” Eric Fleming

“I’ve gone through every kind of humiliation known to mankind, so I’m kind of immune to it at this point.” By 2007 the partnership had gone so sour that Doane keyed Fleming’s car in broad daylight.

Please visit the story by Steven Elbow at the Capital Times for all the details. My account will be drawing on Elbow’s patient sleuthing, but I also want to recall the glorious, not to mention the inglorious, days of this old house.

Marbles

Orpheum Theatre, 1927. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

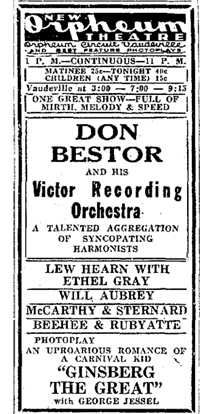

Designed by Rapp and Rapp, premiere theatre architects, the New Orpheum opened in 1927. (It was initially called that because it superseded the Orpheum, a vaudeville house in another part of town, which was soon renamed the Garrick and specialized in live theatre.) The New Orpheum’s lavish French Renaissance foyer swept up to a staircase leading to the balcony. The auditorium held over 2400 seats, making it the biggest theatre in town until the slightly larger Capitol was built across the street a year later, also by Rapp and Rapp.

The New Orpheum (hereafter, the Orpheum) was one of those picture palaces that aimed to elevate the filmgoing experience while also being a good community citizen. It had a corps of ushers, a smoking lounge, and a reputation for punctilious service. The theatre sponsored community events too. When the local newspaper launched a marbles tournament, the Orpheum held a screening for 2000 kids.

The kids came early and jammed the State street side of the New Orpheum, so it was necessary to call extra policemen to handle the traffic. Once inside the theatre they yelled and applauded the two comedy features which were shown for them, and practically jumped out of their seats during the showing of “Why Sailors Go Wrong.”

Six months before the 1929 stock market crash, the Orpheum was reportedly selling 20,000-25,000 tickets per week, in a town of about 55,000 souls.

An RKO town

View from the Orpheum stage, Halloween, 1930. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

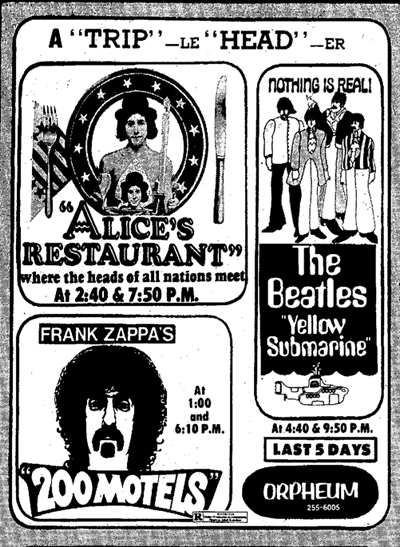

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

Despite the Great Depression, RKO moved quickly to monopolize the Madison movie scene. In 1931, the Parkway (capacity 1100) was acquired by the chain, and soon afterward RKO cut a deal with the Fox Film Corporation to take over the Strand (1400 seats). The swap permitted Fox to dominate Milwaukee in exchange for making Madison an RKO town for first-run films. Of course, in good oligopolistic fashion the RKO theatres showed films from all the studios, as did the second-run houses.

I’ve been unable to determine at what point RKO lost control of its Madison screens. [But see the P. S. below.] Presumably it was after the 1948 divorcement decrees severed Hollywood studios from control of theatres. At some point the Milwaukee entrepreneur Dean Fitzgerald acquired seven local houses, including the Orpheum, under the rubric of the Madison Twentieth Century Theater Corporation.

In 1969, a second screen was carved out of the backstage area of the Orpheum and the minuscule theatre that resulted was called the Stage Door. The contrast with the imposing classic house was startling: the Stage Door was almost certainly the worst theatre in town. Then it declined even more. By the end, with its spidery movable chairs and dank atmosphere, it was reminiscent of the storefront theatres of the nickelodeon era, except that they were surely more comfortable.

Less than heavy traffic

Capital Times advertisement, September 1973.

When Kristin and I came to Madison in 1973, we saw a sort of Sargasso Sea of old movie houses. The Majestic, a decrepit vaudeville house built on a plan as cockeyed as an Escher drawing, was showing X-rated fare, kung-fu, and double-bill repertory. It became a Landmark calendar house. A neighborhood house, the Atwood (aka the Eastwood and the Cinema), built in 1930, screened porn and kiddie shows , though not together. The Esquire also offered sex: arty (The Story of O) or not (Dr. Feelgood, with Harry Reems). The mammoth Strand was still functioning as a first-run house; Star Wars played there for months. The Middleton (seating 500 or so) was designed as a Quonset hut in 1946, and was said to have been built in a week. By our day it was playing second run. The Capitol, where I saw The Exorcist, was still operating too. Every year one theatre or another seemed to run the endlessly popular Eastwood Dollars trilogy.

The mall cinemas were emerging as single-screeners or duplexes. They got the premiere first-run pictures like The Sting, often leaving the downtown houses with lesser items. The most obvious options were counterculture movies and sexploitation.

The Orpheum went along. “Entertainment for the Entire Family!” trumpeted a 1965 Orpheum ad, but by 1969 there were revivals of Bullitt and Bonnie and Clyde. Sometimes classier items like The Godfather would show up in second run, but Orpheum fare in the early seventies was more likely to be Heavy Traffic, Enter the Dragon, The Filthiest Show in Town, revivals of headflix (see above), and a double-bill of Russ Meyer’s Vixen and Up! This was the period when the movie page of the papers included ads for This Is Heaven Sauna Massage, The Rising Sun Counseling Clinic (Adults Only), Photographic Arts Do It Yourself Nude Photography (Camera and Film Supplied), Ms. Brews Lounge (Nude Dancing Daily), and The Dangle strip club.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

Two forces were contending for the property. As part of a plan to revitalize the downtown area, the Madison Idea Foundation proposed putting in an IMAX facility. But preservationists objected that an IMAX setup would wreck the layout of the house. By contrast, restaurant owner Henry Doane (right) favored restoration. He proposed to rehabilitate the old place respectfully and use it for art films, film festivals, and live music. He also wanted to install an upscale café and bar.

Doane won the City Council’s approval and in 1999 he purchased the Orpheum. Throughout the 2000s, thanks to some clever programmers, it played remarkably eclectic fare, from Arnaud Depleschin ‘s A Christmas Tale to Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle (running two weeks, no less). In addition, Doane’s plan to revive the Orpheum as a live music venue, with booze, was finding some success. The grand house that had hosted Gene Krupa, Frank Sinatra, Bob Marley, and Journey now had popular indie bands. When local critic Rob Thomas drew up his list of ten-best shows for the decade, Orpheum concerts took five places. Most memorably, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones played to a packed house the night after the World Trade Tower attacks, highlighted by a version of “God Bless America.”

Drinks plus dining plus music kept the Orpheum doors open, but by the late 2000s the place was obviously not flourishing. There were rumors that distributors, long unpaid, were withholding films. The place was becoming disheveled, with seats broken, that stratospheric ceiling ominously peeling, and the sound system a fog of distortion.

Worse, even though most Madisonians had an affection for the old house, nobody much went there to watch a film. Things had started promisingly: Doane’s introduction to the movie business was the blistering summer of Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace and The Blair Witch Project. But that was an atypical season. During the 2000s, most of the biggest audiences showed up during the Wisconsin Film Festival. It was indeed thrilling to see the place packed out for classics like A Hard Day’s Night (introduced by Roger Ebert) and imports like The Foul King and Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself (both shown in the presence of the directors).

At some point, accommodations were made to favor the concerts: front rows were ripped out to provide dance space.

It became a wretched place to watch movies. Lobby dance parties during screenings could drown out the soundtrack. District 13 was projected within a rectangle framed by a scaffolding erected for an upcoming show. As the decade wore on, you might go to the Orpheum for music, but you didn’t go for the films.

Orpheum vs. Orpheum

Now we know a bit more about what happened behind the scenes in the 2000s. At some point Doane split ownership of the Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison 50-50 with Eric Fleming, a real-estate and restaurant operator.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming’s business style is traced in Elbow’s article. After Fleming became co-owner of the Orpheum, a busted real-estate investment required him to pay creditors $1.5 million. Seeking to dislodge Doane, he created a new company, Orpheum of Madison, claiming that entity as the functioning business arm. He folded that into a package of assets he transferred to Ms. Olesya Kuzmenko for $175,000. “This is what I do for a living,” Fleming explains in Elbow’s article. “I create things and I sell them.”

Who is Kuzmenko, who wound up with a mammoth downtown theatre for the price of a small house on the outskirts of town? She is believed to be Fleming’s girlfriend, but beyond that little is known. She is listed on a license application as President, Vice-President, Secretary, Treasurer, Director, and sole stockholder in Orpheum of Madison. A few years before, Fleming had sold Crave to Christina Bishop, his secretary and girlfriend at the time, under the rubric of a new company Evarc (Crave spelled backward).

There were some curious incidents over these years. There were three fires at the Orpheum, at least two considered by the police to be arson. So far no arrests have been made in the cases. There was also reportedly a break-in, during which a computer was stolen. Perhaps the strangest incident involves the fate of Kuzmenko’s payment. Elbow’s article reports Fleming’s account:

He withdrew the $175,000 he got from Kuzmenko in $100 bills from his bank account, put the cash in a plastic bag and handed it over to a guy identified in court records as Marcus DaMarko, and never saw it again.

“I loaned somebody money,” says Fleming. “I loaned him some money to invest in something. I haven’t talked to him since so I don’t have the money currently.”

So, a reporter asks, you were taken?

“Essentially.”

One more for the road

Because of these maneuvers, Fleming has been running the Orpheum for over a year without input from Doane. The newest issue involves alcohol.

Wisconsin, you must understand, has a frenzied drinking culture. We lead the nation in binge drinking, drinkers per capita, heavy drinkers per capita, and drunk driving. Madison’s main downtown artery, State Street, is packed with bars and restaurants, and the UW’s reputation as a party school attracts an endless supply of youths eager to get wasted. Consequently, what state law calls “alcohol beverages” have been central to the revival of the Orpheum. To establish the lobby restaurant (above) Doane needed to serve beer, wine, and spirits. And Fleming’s cash flow in recent years has been boosted by numerous weddings, which demand booze.

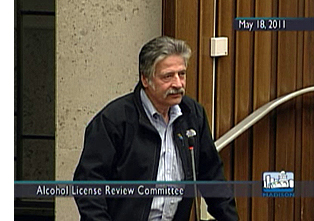

But over the years, the Orpheum’s state vendor’s permit and its liquor license have become problematic. Just during the fall of 2006, the venue under Fleming’s management accumulated some 200 points of alcohol-related violations, and there was a demand that its license be suspended. Across the spring months of 2011, things became more dramatic.

In a series of appeals to the Alcohol License Review Committee of the Common Council, Fleming began to press for the Orpheum’s liquor license to be transferred to his company, Orpheum of Madison. He assured the ALRC that Doane’s original company, Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison, would be evicted from the premises. Doane replied he knew nothing about this, and indeed he was not evicted. Moreover, he argued that Fleming was making purchases for his own company but billing their original one. And Fleming, he claimed, had changed the door locks. The ALRC, declining to step into the middle of the feud, decided to let Doane’s original company hold the license until ownership was clarified.

Auction fever

That fracas took place a year ago, but things really got going this spring. While Doane was suing Fleming to regain control of the building, the Orpheum faced foreclosure because of unpaid bills. In April it went on the auction block.

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Gus Paras had had many dealings with Fleming when both sought to buy property in the area. Now Paras wanted the Orpheum as well. But when the property went to auction, along with the 300 block that had also been part of the Fleming/ Kuzmenko package, Olesya Kuzmenko showed up and began bidding against Paras. In a scene reminiscent of the auction in North By Northwest, she bid the price for the Orpheum up to $1.9 million, but Paras won it for $2.25 million. She bid again on the 300 block properties, but Paras bid her up and then folded, leaving her stuck with her $2.25 million bid. But she couldn’t make the down payment, so the court gave both the Orpheum and the 300 block to Paras for $1.9 million each. However, as of this writing, the sale has not yet been consummated. A court will need to determine who actually owns the building.

In the meantime new alcohol problems resurfaced. Doane requested that the Orpheum’s state seller’s permit not be reactivated. It expired. But the Orpheum continued to sell booze. For a time it seemed that every drink poured since April 2011 had been in violation. A June 2012 story explained:

[Assistant City Attorney Jennifer] Zilavy said the Orpheum should not have served alcohol at concerts and other events. She isn’t sure if the city will pursue civil charges, which could result in a $1,000 fine for each infraction, or refer the matter for criminal charges, which could result in a fine of up to $10,000 or nine months in jail per offense.

As a result, last month the Common Council of the city declined to renew the Orpheum’s liquor license. When the police tried to serve notice of non-renewal, they were unable to rouse anyone. “It is locked up, lights out, nobody there,” reported the officer. Now, however, it seems that Fleming managed to re-activate the license fairly soon after Doane deactivated it, so it’s unclear how long, if at all, the Orpheum was serving drinks illegally.

The city later discovered that Fleming, nothing if not tenacious, was at some point granted a state seller’s permit for his new company. But as of early July the sort-of-partners remained at loggerheads. Doane’s company had a liquor license but no seller’s permit. Fleming’s company now has a seller’s permit but no liquor license. And Doane’s company’s liquor license expired last Saturday. The Madison Common Council has sent the matter to the ALRC for a public hearing. possibly as soon as next week.

I wish I could answer every question that’s come up. Who is Mr. DaMarko, and what became of the 1750 $100 bills? If Paras finally acquires the building, what status does Fleming’s operation have with respect to it? What about Doane’s stake in the theatre he originally bought?

One thing seems certain: If the old place resumes operations, it will be as a venue for weddings and live music, with a bar and perhaps a café. As movies evicted vaudeville from the Orpheum in the 1930s, so now live performance has replaced movies. The drama and comedy have moved off the screen into the streets, the Common Council, and the halls of justice.

Steven Elbow follows up his main story here. If anything develops, he will probably report on it in his blog.

The Orpheum website reflects the chaotic state of its circumstances. Videos of the ALRC hearings, from which my three portraits of the protagonists are taken, may be streamed here and here. In late June, Eric Fleming conducted a brief video tour of the Orpheum’s restorations. The most recent application from Kuzmenko’s company requests that the liquor license begin on 1 July 2012 and end on 30 June 2012. Will the fun never stop?

Some accounts date the Orpheum from 1926, but it opened in March 1927. (See, for example, “New Orpheum’s First Birthday Cake,” The Capital Times, 3 April 1928, 3.) To view more magnificent Orpheum photos from the Wisconsin Historical Society collection, go here. The color shot of the Lobby Restaurant is from the Onion. (The Onion originated–where else?–in Madison.) The color shot of the missing front rows is from the 2010 Wisconsin Film Festival. For a sense of what a wedding looks like in the Orpheum, go to Valo Photography.

Wisconsin’s mad flight from sobriety is documented in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel‘s award-winning series. As far as I know, nothing much has changed since that 2008 survey.

This has been my Year of Living Exhibitionistically; see the Pandora posts and the e-book for accounts of different movie theatres. Older entries are here and here.

P.S. 15 July 2012: Douglas Gomery writes that RKO probably lost its grip on the Orpheum and other theatres much earlier than I speculated:

The Film Daily Yearbook of 1931 lists RKO holdings in Wisconsin: Madison, the Capitol & Orpheum; Milwaukee, the Riverside; and Racine, the Downtown (literally). In 1932 RKO goes into bankruptcy, and all its Wisconsin holdings disappear from FDY. My guess is that the Orpheum and other houses became locally owned.

Douglas wrote the definitive book on American exhibition, Shared Pleasures, and I thank him for the correction.

P.P.S. 16 July: My original post indicated that Kuzmenko won the Orpheum temporarily before she proved unable to make the down payment. Steve Elbow corrected my claim on this: what she acquired at auction was actually the 300 block property, which had been folded with the Orpheum into the overall property Fleming sold her for $175,000. Gus Paras bid successfully on the Orpheum itself.

The blog has been revised to reflect another piece of information Steve provided me: that Fleming may have reactivated the Orpheum’s liquor license quite soon after Doane deactivated it. Thanks to Steve for these corrections.

P.P.P.S. 27 May 2013: A query from Laura Ursin has led me to correct the date in the caption of the top photo, which I had dated from 1938.

The Orpheum Theatre under construction, 1926. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.