Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Observations on Filmart (This is not a typo)

A modest display at Filmart, Hong Kong Convention Centre.

DB here, channeling an apparently apocryphal Soupy Sales line:

Kids, what starts with f and ends in art? No, not that. It’s Filmart, the annual trade gathering that kicks off the Hong Kong Film Festival. Add a space and a capital, and you have the main title of one of our books. Sometimes accidental cross-promotion can work out pretty well, as you see above.

Seriously, though, Filmart is a wonderful event. It includes an opening ceremony to launch the festival, the Asian financing forum known as HAF, the Asian Film Awards (covered a bit here), and a teeming meet-and-greet that sponsors panels, lunches, and hundreds of booths that allow media buyers and sellers to get together. I’ve covered Filmart in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Here are some comments and images from last week’s edition.

The shebang started with the ceremony introducing some of the opening films and their stars. Here the Filmart’s official hostess, Miriam Yeung, is about to go onstage to greet the audience.

And here at the ceremony are the three stars of Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, Gao Yuanyuan, Daniel Wu, and Louis Koo.

Ho Yuhang’s clever neo-noir Open Verdict was a highlight of the shorts collection Quattro Hong Kong 2. Here he is with his star, the radiant Kara Wai Ying-hung, Shaw Brothers action queen and star of both Open Verdict and Ho’s earlier feature Daybreak.

Filmart’s main business takes place in a vast hall, with companies’ displays lined up in rows and along aisles. Most firms have fairly modest stalls, but others are flamboyant, like these big boys for Mei Ah and Universe, two long-established Hong Kong production/ distribution companies.

But the place isn’t so big that you can’t run into old friends, like Margaret Pu (far right) and her colleagues Jack Lee and Dan Zhu from the Shanghai Film Festival.

More movers and shakers: Patrick Frater, CEO of Film Business Asia, and Peggy Chiao, producer (Trigram Films) and doyenne of Taiwanese New Cinema.

At Filmart one can always find some unclassifiable items, as witness the project pictured at the very end of this entry.

New Action on the Mainland

Most panels ran opposite film screenings, so I usually plumped for the movies. But I did attend an intriguing session on “Beyond Box Office: China: The World’s Largest Developing Market.” Sponsored by the Hong Kong Film New Action committee and moderated by Shanghai media executive Bill Zhang Ming, the panel included many Chinese figures and the American Ted Perkins, who has worked for both Warners and Universal and is now serving as executive VP of production for IDG China Media.

Some of the themes discussed echo things I talked about in the added chapters of Planet Hong Kong, but I garnered some new information as well.

*Several panelists pointed out that the stupendous growth in the Chinese box office, over 50% each year, demands that many new cinemas be built. The major cities have now got a good supply of screens, but now the third- and fourth-tier cities need to have more screens. Some commentators spoke of a “new five-year plan” aiming to upgrade and increase the nation’s screens.

*As in America and other countries, a few films typically garner the lion’s share of receipts; one panelist estimated that 80% of income stems from 20% of the films. For the foreseeable future, the big films, from China or the US, will drive the market.

*The growth of the market is even more remarkable given the comparatively small audience (around 20 million, one panelist surmised). Average ticket price is 32 renminbi, or about US$4.88.

*Hong Kong remains essential to the mainland market but also vulnerable. Films with local stars and directors can succeed, and Hong Kong is a key site for financing and packaging projects. But purely local films will remain low-budget items; the bigger films will be mainland co-productions, with some PRC talent and scenery on the screen.

*The popular audience, according to screenwriter-producer Qi Hai, is driven by female tastes: date movies are chosen by the woman, and family films are picked by mothers.

*Ted Perkins pointed out that although recent growth is good for all players, in any film industry there are always more funds in production than can be recouped overall. There will be winners and losers, especially if there’s an overabundance of production, as there currently is on the mainland. Although about 500 films were produced last year, more than half did not find theatrical release or screen in the best cinemas. (Panelists’ estimates of unseen or underseen titles varied from 250 to 400.) Marcus Lim provides a comparable set of figures.

*Some panelists opined that the market lacks directors and stars who are likely to provide success. One panelist estimated that only half a dozen directors have strong track records, and only one star, Ge You, can guarantee an audience.

*Most panelists agreed that 3D was not viable for most films, but in China the new format can help the business in an unusual way. Historically, most mainlanders couldn’t afford going to films, so they aren’t in the habit of attending theatres. They watch films on video or on the Net. Curiosity about 3D may attract new cinemagoers, “educating” spectators to the pleasures of seeing movies on the big screen.

*Most big countries have a well-structured pattern of “windows,” whereby a film moves from the theatre to video, cable, and online. But in China, the expansion of screens is occurring simultaneously with the growth of online distribution, with the danger of piracy. The Chinese will have to come to grips with decisions about pricing and more stable windows.

Seldom do we have a chance to realize that we’re witnessing a historic change in the global film industry. The rise of China is such an event, and film historians should be watching the unfolding process closely.

Changing the film ecology

The Jockey Club Cine Academy, formed last summer, is an educational enterprise guided by the HKIFF Society and funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. It’s a three-year program aiming to increase film literacy among young people. The Academy held a major event during Filmart, a nearly three-hour master class with Jia Zhangke, director of Platform, The World, Still Life, and most recently I Wish I Knew. High school students made up a large part of the audience.

Researcher and editor Wong Ain-ling (above, with Jia) interviewed him about his career and then opened things up for questions. Here are a few points Jia made.

*His recent turn toward documentary filmmaking isn’t a new development for him. When he was starting out, documentaries were the most dynamic part of the PRC film scene. Although the films captured aspects of contemporary life ignored by mainstream movies, they were seldom watched by audiences. So the question for Jia became: “How to change our film ecology?”

He has used a documentary project to spark a fiction feature. In Public (2001) became a draft for Unknown Pleasures. Jia enjoyed eliminating dialogue and narration from his documentaries, relying on peoples’ faces and situations to convey ideas. Critics complained that documentarists couldn’t tell stories, but he wanted mainland audiences to learn to find the latent emotions in the scenes, the “poetic” side of realistic cinema.

*His early films incorporated popular music, including Taiwanese tunes sung by Teresa Teng. Why? During the 1980s and 1990s, mounted loudspeakers broadcast a lot of Mandarin pop songs, making this music just part of a city’s ambience. This was something he exploited in his first feature, Xiao Wu.

*Jia had arguments with censors on his first three features, and those films weren’t widely seen. But in 2004, the censorship system changed, mostly for the better. Yet distributors still block films shot on video from being shown in cinemas, creating what Jia called a “technical censorship.”

*The reports are true: He is making a martial arts film with Johnnie To’s Milkyway firm. Jia wants to examine the imperial system in the period around 1900. He would like to follow it with another historical film, this one about Hong Kong in 1949, centering on two characters, a Communist and a KMT Nationalist.

Like Hong Kong itself, Filmart has a pulsating energy and offers an overwhelming array of choices: you can watch movies, attend events, and just gawk. You must run to keep up. That’s as it should be.

For more coverage of industry doings at Filmart, see Liz Shackleton’s rundown at Screen International (may be proprietary). Another story in Screen International mulls over the prospect that China could fairly soon become the world’s biggest market. See as well several items at Film Business Asia, particularly Stephen Cremin’s article on Chinese coproductions. For our takes on some Jia Zhangke films, you can go to this category.

PS 31 March (HK time): I should have mentioned what the New Action panel did not: Piracy. The LA Times has a good recent article on DVD bootlegging in the PRC, raising the crucial factor I’ve heard mentioned as well: the role of the People’s Liberation Army.

Rebooked

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, CinemaScope).

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers? I asked once before, but in a different tone of voice. Books are still being published, thick and fast, and everybody who cares about cinema should take a look at these.

In the frame

Ballet mécanique.

When the talk turns to the great film theorists of the heroic era, you hear a lot about Bazin and Eisenstein, less about Rudolf Arnheim. But the prodigiously learned Arnheim pioneered the study of art from the perspective of Gestalt psychology. Although he’s probably best known for his studies of painting in Art and Visual Perception, as a young man he was a film critic and in 1930 published a major theoretical book on cinema. First known in English as Film, then in its 1957 revision as Film as Art, this has long been considered a milestone. But Arnheim was famously skeptical of color and sound movies, and he had comparatively little to say about the many cinematic trends after 1930. (He died in 2007, aged 102.) While psychologists grew wary of Gestalt ideas, cinephiles embraced Bazin and academics moved toward semiotics and other large-scale theories. For some time Arnheim has seemed a graceful, erudite relic.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

This is no esoteric exercise. The essays present probing arguments with patient lucidity. Encouragingly, most of the contributors are early in their careers. (I have a piece in the collection as well, an expanded version of a blog entry.) The anthology proves that a seminal thinker can always be reappraised. There’s always more to be understood.

In the Higgins collection Malcolm Turvey furnishes an essay on Arnheim’s relation to various strands of modernism. That vast movement is treated at greater length in Turvey’s new book, The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s. At the book’s core are close analyses of five exemplary films encapsulating various trends. Turvey studies Richter’s Rhythm 21 and abstract film, Léger and Murphy’s Ballet mécanique and cinéma pur, Clair’s Paris Qui Dort and Dada, Dalí and Buñuel’s Chien Andalou and Surrealism, and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and the “city symphony” format. For each film Turvey provides informative historical background and, often, some controversial arguments. For example, he finds Léger to be surprisingly concerned with preserving classical standards of beauty. Indeed, one overall thrust of the book is to suggest that modernism was less a rejection of all that went before than a selective assimilation of valuable bits of tradition. (This applies as well to Eisenstein, I think, as I try to show in my book on his work.)

No less controversial is Turvey’s careful dissection of what has come to be known as “the modernity thesis.” This is the idea that urbanization, technological change, and other forces have fundamentally changed the way we perceive the world, perhaps even altered our basic sensory processes. Specifically, some argue, because the modern environment triggers a fragmentary, distracted experience, that experience is mimicked by certain types of film, or indeed by all films. Step by step Turvey argues that this is an implausible conclusion. This last chapter is sure to stir debate among the many scholars who argue for film’s essential tie to a modern mode of perception.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Cossar advances to more familiar ground, studying early widescreen practice in The Big Trail and moving to analyses of films by masters like Preminger, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin. Although most chroniclers of the tradition stop in the early 1960s, Cossar presses on to consider the changes wrought by split-screen films like The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair. The survey concludes with discussions of cropping techniques in digital animation (e.g., Pixar) and web videos, which often employ letterboxing as a compositional device. In all, Letterbox traces recurring technological problems and aesthetic solutions across a wide swath of film history.

Critics’ corner

Two of America’s senior film writers have revisited their earlier writings, with lively results. Dave Kehr’s collection When Movies Mattered samples his Chicago Reader period, from 1974 to 1986. Disguised as weekly reviews, Kehr’s pieces were nuanced essays on films both contemporary and classic.

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

It resurrects the flashback structure of his 1950 Sunset Boulevard, but it goes further, placing flashbacks with flashbacks and complicating the time scheme in a manner reminiscent of such demented 40s films noirs as Michael Curtiz’s Passage to Marseille and John Brahm’s The Locket. . . But the jumble of tenses also clarifies the film’s design as a subjective stream of consciousness. The images come floating up, appearing in the order of memory.

How many of those reviewers whose flash-fried opinions count for so much on Rotten Tomatoes can summon up information about the construction of Passage to Marseille or The Locket? And how many could make the case that Wilder, in returning to the forms fashionable in his early career, would repurpose them for the sake of a reflection on death, resulting in “a film as deeply flawed as it is deeply felt”? Kehr’s work from this period is appreciative criticism at its best, and he never lets his knowledge block his immediate response. “I admire Fedora, but it also frightens me.” It’s time we admitted that Dave Kehr, working far from both LA and Manhattan, was writing some of the most intellectually substantial film criticism we have ever had.

Also hailing from the Midwest is Joseph McBride, a professor, critic, and biographer. Apart from his rumination on Welles, his books have focused on popular, even populist, directors like Capra (The Catastrophe of Success), Ford (Searching for John Ford), and Spielberg (Steven Spielberg: A Biography). The University Press of Mississippi and bringing first two volumes of this trilogy back into print, and it has just reissued the third in an updated edition.

Here Spielberg emerges as far more than a purveyor of popcorn movies. McBride sees him as a restless, wide-ranging artist, and the additions to the original book have enhanced his case. McBride offers persuasive accounts of Amistad and A.I., which he regards as major achievements. He goes on to argue that Spielberg’s unique power in the industry allowed him to face up to central political issues of the 2000s.

He made a series of films in various genres reflecting and examining the traumatic effects of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the repression of civil liberties in the United States during the George W. Bush/ Dick Cheney regime. . . . No other major American artist confronted the key events of the first decade of the century with such sustained and ambitious treatment (450).

McBride is no cheerleader. He can be as severe on Spielberg’s conduct as on his films, criticizing much of the DreamWorks product as dross and suggesting that Spielberg sometimes trims his sails in interviews. I’d contend that McBride underrates some of Spielberg’s work, notably Catch Me If You Can and The War of the Worlds. But McBride has perfected his own brand of critical biography, blending personal information (he reads the films as autobiographical), tendencies within the film industry and the broader culture, and critical assessment. All studies of Spielberg’s work must start with McBride’s monumental book. Ten years from now we can look forward to another update; surely his subject will have made a few more movies by then.

Foreign accents

8 1/2.

Today we regard Citizen Kane as a classic, if not the classic. But for several years after its 1941 release it wasn’t considered that great. It missed a place on the Sight and Sound ten-best critics’ polls for 1952; not until 1962 did it earn a spot (though at the top). Its rise in esteem was due to changes in film culture and, some have speculated, the fact that Kane was a regular on TV during the 1960s. Something similar happened with His Girl Friday, another stealth classic. I’ve traced what I know about its entry into the canon in an earlier blog entry.

What about the postwar classics like Open City and Bicycle Thieves and the works of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni and Kurosawa and the New Wave? Surely some of the films’ fame comes from their intrinsic quality—many are remarkable movies—but would we regard them the same way if their reputation hadn’t spread so widely abroad, especially in America? Questions like this lead us to what film scholars have come to call canon formation: the ways artworks come to wide notice, receive critical acclaim, and eventually become taken for granted as classics.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

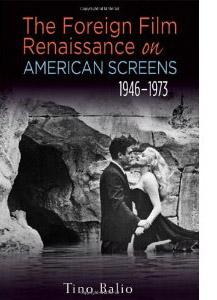

Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 reveals a side of canon formation that’s too often overlooked. Balio is less concerned with analyzing films than Turvey, Cossar, Kehr, and McBride are. He is asking a business question: What led the U. S. film industry to accept and eventually embrace films so fundamentally different from the Hollywood product?

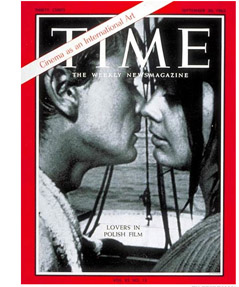

Several researchers have pointed to the roles played by influential critics, film festivals, and new periodicals like Film Comment and Film Culture. Intellectual and middlebrow magazines promoted the cosmopolitan appeal of the foreign imports. By 1963 Time could run a feverish cover story on “The Religion of Film” to coincide with the first New York Film Festival.

Balio duly notes the importance of such gatekeepers and agenda setters. But he goes back to the beginnings, with the small import market of the 1930s. Turning to the prime postwar phase, he broadens the cast of players to include the business people who risked buying, distributing, and publicizing movies that might seem hopelessly out of step with US audiences. He shows how small importers brought in Italian films at the end of the 1940s, and these attracted New York tastemakers, notably Times critic Bosley Crowther, who were keen on social realism. Within a few years ambitious entrepreneurs were marketing British comedies, Swedish psychodramas, Brigitte Bardot vehicles, and eventually the New Waves and Young Cinemas of the 1960s. As distributors fought censors and slipped films into East Side Manhattan venues, an audience came forward. The “foreign films”—often recut, sometimes dubbed, usually promoted for shock, sentiment, and sex—were positioned for the emerging tastes of young people in cities and college towns.

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Bryant Haliday and Cy Harvey of Janus Films. . . devised a successful campaign to craft an image of Bergman as auteur and to carefully control the timing of each release. . . . Janus released the films in an orderly fashion to prevent a glut on the market and to milk every last dollar out of the box office. No other auteur received such treatment.

The work paid off: Bergman made the cover of Time in 1960, and soon The Virgin Spring and Through a Glass Darkly won back-to-back Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. Eventually, Bergman and other foreign auteurs attracted the big studios. Now that small distributors had shown that there was money in coterie movies, the major companies (having problems of their own) embraced imported cinema—first through distribution and eventually through financing. If you admire Godard’s The Married Woman, Band of Outsiders, and Masculine Feminine you owe a debt to Columbia Pictures, which underwrote them.

Work like Balio’s does more than bring the name Cy Harvey into film history. It reminds us to follow the money. If we do, we’ll see that not every “foreign film” stands radically apart from big bad Hollywood. More generally, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens reminds us that even high-art cinema is produced, packaged, and circulated in an economic system. The distinction between commercial films and personal films, business versus art, is a wobbly one. Rembrandt painted on commission and Mozart was hired to write The Magic Flute. Sometimes good art is good business.

I couldn’t work this in anywhere else: The bulk of the essays in Arnheim for Film and Media Studies are by people associated with our department at Wisconsin. They do us proud, naturally. Incidentally, Joe McBride went to school at UW too, and Tino and I taught together here for over thirty years.

Dave Kehr maintains a blog and teeming forum here.

Hart Perez has made a documentary, Behind the Curtain: Joseph McBride on Writing Film History. An excerpt is here. McBride’s website has information about his many projects.

James E. Cutting provides an unusually precise account of canon creation in his 2006 book Impressionism and Its Canon, available for free download here. I’ve written an earlier blog entry discussing Jim’s research into film.

My mention of American generations is based on Elwood Carlson’s study The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Carlson examines the varying experiences and life chances of people who fought in World War II; people who came of age during the 1960s; and the less populated cohort that fell in between. Doing some pop sociology, I’d hypothesize that the art-film market’s growth relied on a convergence of all three, which were more disposed to art film than cohorts in earlier periods. For example, veterans who had served overseas and gone to college on the GI Bill were more familiar with non-US cultures than their parents and, I surmise, weren’t entirely put off by foreign films. When I first met Kristin’s mother, Jean Thompson, she already knew the work of Carl Dreyer, having seen Day of Wrath at an art cinema in Iowa City. She was in graduate school after World War II, on the G.I. Bill, as was her new husband, Roger, also in school on the G.I. Bill and managing that art cinema. They saw Children of Paradise and other wartime foreign films just getting their releases in the U.S., as well as post-war films like Bicycle Thieves.

The Lucky Few, also known as the Good Times generation, were born between the late twenties and the early 1940s. They were well placed to enjoy postwar prosperity and the period’s explosion of artistic expression. The Lucky Few cohort includes powerful film critics like John Simon (born 1925), Andrew Sarris (1928), Richard Roud (1929), Eugene Archer (1931), Susan Sontag and Richard Schickel (1933), and Molly Haskell (1939). Aged between twenty and thirty when the foreign-film wave struck, they were mighty susceptible to it. (Pauline Kael, though born in 1919, had a delayed career start, entering film journalism in the 1950s along with Sarris et al.) You might slip in David Thomson (born 1941), Jonathan Rosenbaum (1943), and Richard Corliss (1944).

The Baby Boomers jumped on the carousel in the 1960s, with results that are all too apparent. Dave Kehr and Joe McBride are Boomers, as are Kristin and I. Tino, for the record, is ageless.

Minority Report.

Still cheating on video games

KT here:

Since I got back from England a month ago, I’ve been catching up with all the magazines that accumulated during the three weeks I was gone. Recently I read the November 15 issue of Newsweek. Initially I was happy to see the “Back Story,” the one-page article that comes at the end of each issue. It’s called “How Super Is Mario?” and compares the income of the video games and move industries. (It’s not available online complete unless you agree to a free trial of the online magazine. If you do, it’s here.)

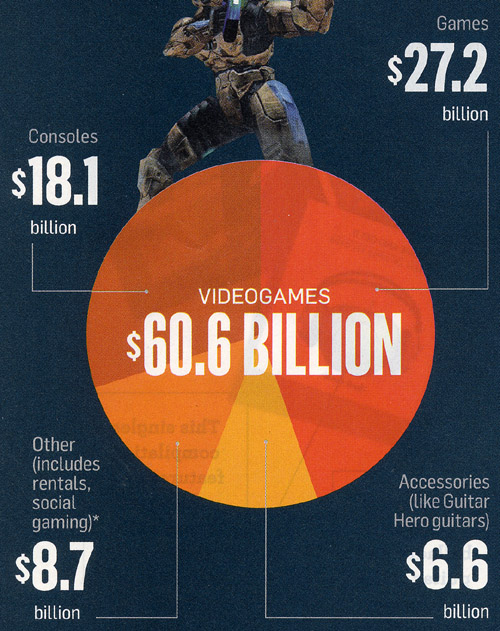

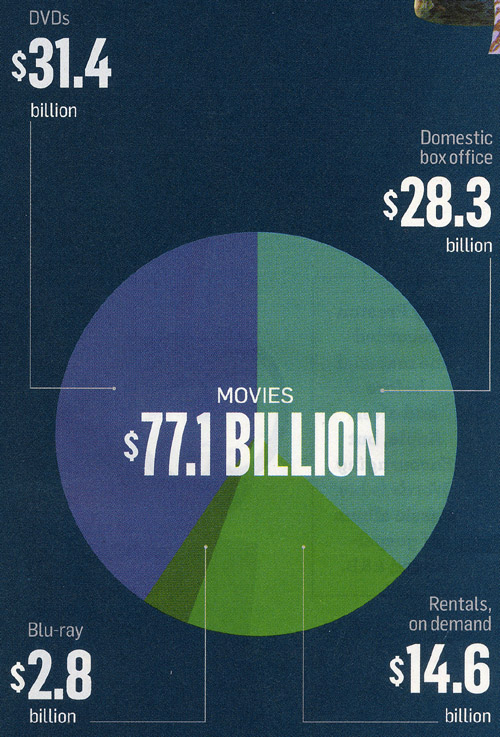

The article consists of two pie charts (above and below) and a brief text. At first the text sounded promising: “A big game—take September’s release of Halo Reach, for example—can sell millions of copies at about $50 a pop. That’s far pricier than any movie ticket, of course. But despite the conventional wisdom, the silver screen still rakes in more cash overall than the gaming industry, according to an analysis of recent revenue.” Great, I thought, at last a publication that makes an accurate comparison between the amounts of money brought in by games and by movies.

But in fact the Newsweek analysis just repeats the conventional wisdom it claims to overturn and makes the same old invalid comparison that entertainment-business journalism has been making since video games started making real money. A cursory glance at the pie charts makes it seem as if the gaming industry is not all that far behind films: the games total is $60.6 billion vs. $77.1 billion for movies. But let’s take a glance that isn’t cursory.

I’ll make the same point that I made in Chapter 8 of The Frodo Franchise (2007), where I deal with video games. There, too, I quoted a Newsweek article (from June 3, 2002): “In 2001, consumers snapped up $9.4 billion worth of game software and hardware—up 43 percent from the previous year—led by Sony’s world-beating PlayStation 2. Noting that the game industry had once again outstripped Hollywood’s box-office revenues, the head of Sony’s U.S. computer-entertainment division, Kaz Hirai, says his next target is the $18 billion home-video industry.” (225-26)

Note that reference to “software and hardware.” The figure includes the consoles and other equipment people buy in order to play games. But the pie chart of movie-industry income doesn’t include hardware. What would happen if the sales of theater and home projectors, DVD and Blu-ray Players, iTouches, and all the other gadgets used to watch movies were factored into the film-income figures? As we know, there have been a lot of digital theater projectors and 3D systems sold in recent years, not to mention all those portable media players. The games industry would fall farther behind than it already is. (And let’s not forget that most of those gaming consoles also play movies, so an indeterminate part of their income should go into the movies column. Since last January, the Wii even comes with a Netflix connection installed.)

As of 2004, the most recent year I could get figures for when I was writing my book, games software brought in $6.2 billion. That same year all forms of film distribution (including home-video and broadcast and cable television) grossed $45 billion.

Yes, games are gaining, but they’re not nearly as close to catching up with movies as media coverage would lead you to believe. The good thing about Newsweek’s recent pie chart is that it allows us easily to factor out the hardware income from the games’ side.

Consoles are listed at $18.1 billion and accessories at $6.6. Take them away, and games software brought in $35.9 billion in the period covered (January 1, 2008 to September 30, 2010). There’s nothing to take away from the film pie, since it consists entirely of software rentals and sales. So film still brings in more than twice as much, $35.9 billion vs. $77.1. DVD and Blu-ray sales, at $34.2 billion, make nearly as much as all games.

True, the games revenue has risen considerably in proportion to films since 2004. In that year, games made 13.8% of what films did. In the 21-month period covered by the Newsweek analysis, they made 46.6% as much. Will there be as big a jump proportionately in the next five years? Maybe. It’s possible that the move into streaming downloads as a distribution basis for home video will mean that movies simply cost less per view and hence will lose ground against games in terms of total income, if not in terms of popularity. Still, methods of distributing games might end up making them cheaper as well.

None of this takes into account that most mainstream blockbusters spawn a lot more ancillary products than do comparable video games.

I don’t know why entertainment journalists keep making this basic and pretty obvious mistake of continuing to include hardware sales only for games when they compare the success of these two media. It is after all their job to research the figures and analyze them in the way most useful to their readers. Giving those readers the erroneous impression that video-game sales have nearly caught up with film income doesn’t seem useful. The myth is probably something that the gaming industry fostered years ago to give the impression that it was more successful than more balanced comparisons would reveal. Journalists kept making the same kind of misleading comparison, which became the “conventional wisdom” that Newsweek only thinks it’s correcting.

As I point out in the same chapter of my book, game companies and film studios are not entirely in competition with each other. They cooperate to a considerable extent, since movies and games are often part of the same franchises. Some of the same people work on both. Often similar or identical technology is used in creating both. Increasingly film studios big and little have their own game-production units, and gaming companies are seeing more value in creating intellectual property that can be used across platforms. Some of the top film directors have been involved in creating games. Films routinely get adapted into games as part of their overall franchises, and some games get adapted as films. A successful film usually makes for a successful game, though the opposite isn’t yet as common. Though the industries do compete for leisure time and money, neither is out to kill the other. In many cases they’re out to boost each other’s success.

New Zealand is still Middle-earth: A summary of the Hobbit crisis

Richard Taylor during the October 20 anti-boycott march.

Kristin here:

Ordinarily I post about Peter Jackson’s Tolkien-adapted films on my other blog, The Frodo Franchise. But over the past five weeks a dramatic series of events has played out in New Zealand in regard to the Hobbit production. Those events tell us interesting things about today’s global filmmaking environment. As countries around the world create sophisticated filmmaking infrastructures, complete with post-production facilities, they are creating a competitive climate. Government agencies woo producers of big-budget films by offering tax rebates and other monetary and material incentives. Usually such negotiations go on behind closed doors, but the recent struggle over The Hobbit was played out more publicly.

Back in late September, the progress of Jackson’s project seemed slow. We Hobbit-watchers were mainly fretting over the lack of a greenlight for the two-part film “prequel” to The Lord of the Rings.

Of course, Tolkien’s LOTR (1954-55) was a sequel to The Hobbit (1937), but the films will have been made in reverse order. That’s due to MGM’s having the distribution rights back in 1995 when Peter Jackson went looking to use Tolkien’s novels to show off Weta Digital’s fancy new CGI abilities. Miramax bought the LOTR production and distribution rights and the Hobbit production rights.

Most of the news I was then blogging about related to MGM’s financial problems and how they would be resolved. Would Spyglass semi-merge with the ailing studio, convert its nearly $4 billion in debt into equity for its creditors, and bring it back into a position to uphold its half of the Hobbit co-production/co-distribution deal with New Line? Or would Carl Icahn push through his scheme to merge Lionsgate and MGM? The answer, by the way, came just this Friday, October 29, when the 100+ creditors voted to accept the Spyglass deal. I have been saying all along that the MGM situation was not the primary sticking point that was delaying the greenlight, even though most media reports and fan-site discussions assumed that it was. The greenlight having been given before this past week’s vote, I assume I was right. The real reason for the delay has not been revealed.

Meanwhile, other websites were speculating about casting rumors. Would Martin Freeman really play Bilbo, or were his other commitments going to interfere? (He will play Bilbo. Good choice, in my opinion. The man looks just like a hobbit.)

Then, on September 25 came the news that international actors’ unions were telling their members not to accept parts in The Hobbit. There was a boycott. The result was a maelstrom of events for the past five weeks or so. You may have heard about some of them. There were meetings and petitions. When Warner Bros. threatened to take the film to a different country, pro-Hobbit rallies followed. A visit by some high-up New Line and WB execs and lawyers to New Zealand led to hurried legislation to change the labor laws to reassure the studios that a strike wouldn’t happen. Finally, the government ended up raising the tax rebates for the production. Result: The Hobbit will be made in New Zealand after all. New Line, by the way, was folded into Warner Bros. by their parent company, Time Warner, after The Golden Compass failed at the box office. It remains a production unit but no longer does its own distribution, DVDs, etc.

The news that followed the launch of the boycott has come thick and fast, often involving misinformation. It was complicated, centering on an ambiguity in New Zealand labor laws as applied to actors and on a strange alliance between Kiwi and Australian unions. One of the biggest American film studios decided to use the occasion to demand more monetary incentives from the New Zealand government. I tried to keep up with all this and ended up posting 110 entries on the subject. (In this I was helped mightily by loyal readers who sent me links. Special thanks to eagle-eyed Paul Pereira.) That was out of 144 total entries from September 25 to now. There was plenty of other news to report. During all this, the MGM financial crisis was creeping toward its resolution, firm casting decisions were finally being announced, and the film finally got its greenlight. Whew!

For those who are interested in The Hobbit and the film industry in general but don’t want to slog through my blow-by-blow coverage, I’m offering a summary here, along with some thoughts on the implications of these events. Those who want the whole story can start with the link in the next paragraph and work your way forward. Obviously the links below don’t include all 110 entries.

In some cases the dates of my entries don’t mesh with those of the items I link to, given that New Zealand is one day ahead. I’ve indicated which side of the international dateline I’m talking about in cases where it matters.

September 25: Variety announces that the International Federation of Actors (an umbrella group of seven unions, including the Screen Actors Guild) is instructing its members not to accept roles in The Hobbit and to notify their union if they are offered one.

At that point, the film had not yet been greenlit, so it wasn’t clear how this would affect the production. The action against The Hobbit originated with the Australian union MEAA (Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance) and its director, Simon Whipp. Because relatively few actors in New Zealand are members of New Zealand Actors Equity, that small union is allied with the MEAA. The main goals of the union’s efforts were to secure residuals and job security for actors. The MEAA maintained that Ian McKellen (Gandalf), Cate Blanchett (Galadriel), and Hugo Weaving (Elrond) all supported the boycott; so far no evidence for this has been offered. Possibly they agreed to abide by it but were not in favor of it. Given the lack of a greenlight, none had been offered a role yet.

The main bone of contention has been a distinction made in labor laws in New Zealand. Actors are considered to be equivalent to contractors rather than employees, since they are hired on a temporary basis; it is illegal for a company to enter into negotiations with a union representing contractors. On that basis, Peter Jackson, who was first contacted in mid-August, refused to meet with the group. Besides, he isn’t the producer hiring the actors. Warner Bros., through New Line, is. As with all significant films, a separate production company, belonging to New Line, has been set up to make The Hobbit. It’s called 3 Foot 7. (The LOTR production company was 3 Foot 6, the average height of a hobbit being 3’6″.)

September 27. Peter Jackson responded angrily to the boycott, laying out the issues that would ultimately guide the New Zealand government’s response to the crisis:

“I can’t see beyond the ugly spectre of an Australian bully-boy using what he perceives as his weak Kiwi cousins to gain a foothold in this country’s film industry. They want greater  membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

“I feel growing anger at the way this tiny minority is endangering a project that hundreds of people have worked on over the last two years, and the thousands about to be employed for the next four years, [and] the hundreds of millions of Warner Brothers dollars that is about to be spent in our economy.”

Losing The Hobbit would leave New Zealand “humiliated on the world stage” and “Warners would take a financial hit that would cause other studios to steer clear of New Zealand”, Jackson said.

“If The Hobbit goes east [East Europe in fact], look forward to a long, dry, big-budget movie drought in this country. We have done better in recent years with attracting overseas movies and the Australians would like a greater slice of the pie, which begins with them using The Hobbit to gain control of our film industry.”

Various people and organizations in New Zealand soon line up behind one side or the other. Those siding with Jackson include Film New Zealand (which promotes filmmaking by foreign countries in New Zealand) and SPADA (the Screen Production and Development Association) and eventually the government. On the unions’ side is the Council of Trade Unions.

September 28. New Line, Warner Bros., and MGM weigh in with a statement that ups the ante. It dismisses the MEAA’s claims as “baseless and unfair to Peter Jackson” and continues:

To classify the production as “non-union” is inaccurate. The cast and crew are being engaged under collective bargaining agreements where applicable and we are mindful of the rights of those individuals pursuant to those agreements. And while we have previously worked with MEAA, an Australian union now seeking to represent actors in New Zealand, the fact remains that there cannot be any collective bargaining with MEAA on this New Zealand production, for to do so would expose the production to liability and sanctions under New Zealand law. This legal prohibition has been explained to MEAA. We are disappointed that MEAA has nonetheless continued to pursue this course of action.

Motion picture production requires the certainty that a production can reasonably proceed without disruption and it is our general policy to avoid filming in locations where there is potential for work force uncertainty or other forms of instability. As such, we are exploring all alternative options in order to protect our business interests.

Thus the specter of the production being not only delayed but also taken to another country is raised, and the implications of such a threat will gradually force the government to take measures to prevent that happening.

Peter Jackson also makes a statement to the Wellington newspaper that the Hobbit production might move to Eastern Europe. (The next day he reveals that WB is considering six countries for it.)

That night, a group of 200 actors met in Auckland, issuing a statement again asking the producers to meet for negotiations.

October 1. Jackson and WB voluntarily offer a form of residuals to Hobbit actors:

Sir Peter Jackson said New Zealand actors who did not belong to the United States-based Screen Actors’ Guild had never before received residuals – a form of profit participation. Warner Brothers had agreed to provide money for New Zealand actors to share in the proceeds from the Hobbit films.

It would be worth “very real money” to New Zealand actors. “We are proud that it’s being introduced on our movie. The level of residuals is better than a similar scheme in Canada, and is much the same as the UK residual scheme. It is not quite as much as the SAG rate.”

After much speculation, an announcement is made that Peter Jackson will definitely direct the film (which Guillermo del Toro had exited in May).

At about this time members of the filmmaking community begin campaigning actively against the boycott. An anti-boycott petition for New Zealand filmmakers and persons indirectly related to production to sign goes online; it ends with 3275 people having endorsed it.

October 15. The Hobbit is greenlit, but the possibility of moving the production out of New Zealand remains. Actors who have already been auditioned begin to be officially cast.

October 20. Actors Equity NZ is due to meet in Wellington. Richard Taylor (head of Weta Workshop) calls for a protest march. The actors’ meeting is called off due, the union says, to the “angry mob” that results. (Videos and photos posted online show a lengthy line of people walking through the streets in a peaceful fashion; that’s Richard talking to the press in the photo at the top. A person less likely to incite a “mob” to anger I cannot imagine.) An actors’ meeting scheduled for the next day in Auckland is also called off, putatively for the same reason, though no protest event had been planned there.

The turning-point day

October 21 (NZ). Jackson and his partner Fran Walsh issue a statement that implies that Warner Bros. has decided to move The Hobbit elsewhere:

“Next week Warners are coming down to New Zealand to make arrangements to move the production offshore. It appears we cannot make films in our own country even when substantial financing is available.”

Helen Kelly, president of the Council of Trade Unions calls Jackson “a spoiled little brat” on national television, helping turn the public against her cause.

Fran Walsh hints during a radio interview that WB might move The Hobbit to Pinewood Studios in England (where the Harry Potter films have been shot).

Prime Minister John Key says he hopes the production can be kept in New Zealand. Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee says he will meet with the WB delegation.

The international actors’ boycott against The Hobbit is called off.

October 21 (U.S.)/22 (NZ). WB is still considering moving the production, saying it has no guarantee that the actors will not go on strike. Key suggests that the labor law might be changed to provide that guarantee. The proposed legislation soon will become known as the “Hobbit bill.”

The Wall Street Journal suggests that a slight slip in the value of the New Zealand dollars against the American dollar is partly due to uncertainties about whether The Hobbit production will stay in the country.

WB announces the casting of Martin Freeman as Bilbo, plus several actors chosen as dwarves.

Bilbo Baggins by Tolkien and Martin Freeman, Bilbo-to-be.

A “positive rally” to convince WB to keep the production in New Zealand is announced. This eventually results in individual rallies in several cities and towns on October 25.

( U.S. time) Variety reports that unnamed sources within WB have said the studio is inclining toward keeping the production in New Zealand. This is the only hint of positive news from inside WB that comes out during the entire process.

Over the next few days, much finger-pointing takes place. Figures concerning the potential loss to NZ tourism if the film goes elsewhere are released. Helen Kelly apologizes for her “brat” remark.

October 25 (NZ). The WB delegation of 10 executives and lawyers arrive in Wellington. The pro-Hobbit rallies take place.

Pro-Hobbit rally in Wellington (Marty Melville/Getty Images).

October 26. News breaks that if The Hobbit is sent to another country, the post-production work (originally intended for Weta Digital and Park Road Post, companies belonging to Jackson and his colleagues) could take place outside New Zealand.

The WB delegation arrives at the prime minister’s residence in a fleet of silver BMWs. After the meeting ends, Key puts the chances of retaining the production at 50-50. He reiterates that the labor law might be changed.

Photo: NZPA

Presumably at this meeting, WB also puts forward a demand for higher tax rebates or other incentives; other countries it has been considering have more generous terms. Ireland has offered 28%, while New Zealand’s Large Budget Screen Production Grant scheme offers only 15%. This demand is not made public until later. During Key’s speech after the meeting, however, he mentions the possibility of higher incentives, but says the government cannot match 28%.

Editorials soon appear attacking the idea of changing a law at the behest of a foreign company.

The government’s deal with Warner Bros.

October 27. The New Zealand dollar again slips in relation to the American dollar, again attributed to uncertainty about The Hobbit.

Key and other government officials meet again with the WB delegation. The legal problem has been resolved to both sides’ satisfaction, but WB is holding out for higher incentives.

In the evening, Key announces that an agreement has been reached and the Hobbit production will stay in New Zealand:

As part of the deal to keep production of the “The Hobbit” in New Zealand, the government will introduce new legislation on Thursday to clarify the difference between an employee and a contractor, Mr. Key said during a news conference in Wellington, adding that the change would affect only the film industry.

In addition, Mr. Key said the country would offset $10 million of Warner’s marketing costs as the government agreed to a joint venture with the studio to promote New Zealand “on the world stage.”

He also announced an additional tax rebate for the films, saying Warner Brothers would be eligible for as much as $7.5 million extra per picture, depending on the success of the films. New Zealand already offers a 15 percent rebate on money spent on the production of major movies.

(The figure for the government’s contribution to marketing costs is later given as $13 million.)

October 28 (NZ). Peter Jackson returns to work on pre-production, which his spokesperson says has been delayed by five weeks as a result of the boycott. Principal photography is expected to begin in February, 2011, as had been announced when the film was greenlit. (The two parts are due out in December 2012 and December 2013.)

The Stone Street Studios. The huge soundstage built after LOTR is at the left; the former headquarters of 3 Foot 6 at the upper left.

In Parliament, a vote to rush through consideration of the “Hobbit bill” passes, and debate continues until 10 pm.

October 29 (NZ). The “Hobbit bill” passes in Parliament by a vote of 66 to 50, thus fulfilling the governments offer to WB and ensuring that The Hobbit would stay in New Zealand. It was known in advance that Key had enough votes going into the debate to carry the legislation.

It is revealed that James Cameron has been in talks with Weta to make the two sequels to Avatar in New Zealand. (Avatar itself was partly shot in New Zealand, with the bulk of the special effects being done there.) The timing has nothing to do with the Hobbit-boycott crisis. The two films are due to follow The Hobbit, with releases in December 2014 and December 2015.

October 30 (NZ). It is announced that the Hobbiton set on a farm outside Matamata will be built as a permanent fixture to act as a tourist attraction. (The same set, used for LOTR, was dismantled after filming, leaving only blank white facades where the hobbit-holes had been; nevertheless the farm has attracted thousands of tourists. See below.) Warner Bros. had been persuaded by the New Zealand government to permit this, though whether this was part of the agreement made with the studio’s delegation is not clear. I suspect it was.

It is also announced that the extended coverage of the 15% tax rebates specified in the “Hobbit bill” will apply to other films from abroad made in New Zealand—but only those with budgets of $150 million or more. (Presumably in New Zealand dollars.)

A remarkable outcome

In a way, it is amazing that a film production, even a huge one like The Hobbit, virtually guaranteed to be a pair of hits, could influence the law of a country–and make the legal process happen so quickly. Yet given the ways countries and even states within the USA compete with each other to offer monetary incentives to film productions, in another way it is intriguing that such pressure is not exercised by powerful studios more often. In most cases, a production company simply weighs the advantages and chooses a country to shoot in. Maybe countries get into bidding wars to lure productions or maybe they just submit their proposals and hope for the best. Certainly the six other countries considered briefly by WB were quick to jump in with information about what they could offer the Hobbit production.

In the case of Warner Bros. and The Hobbit, everyone initially assumed that the two parts would be filmed in New Zealand, just as LOTR had been. Yet the actors’ unions created an opportunity. The boycott gave Warner Bros. the excuse to threaten to pull the film out of New Zealand. Meeting with top government officials, WB executives demanded assurance that a strike would not occur–and oh, by the way, we need higher monetary incentives. As a result, a compromise was reached, the incentives were expanded, and there was a happy ending for the many hundreds of filmmakers of various stripes who would otherwise have been out of work.

Although there is considerable bitterness among the actors’ union members and those who supported their efforts, many in New Zealand see the tactics of the MEAA as extremely misguided. Kiwi Jonathan King, the director of the comic horror film Black Sheep, sums it up:

But this was all precipitated by an equal or greater attack on our sovereignty: an aggressive action by an Australian-based union taken in the name of a number of our local actors, backed by the international acting unions (but not supported by a majority of NZ film workers), targeting The Hobbit, but with a view to establishing a ’standard’ contract across our whole industry. While the actors’ ambitions may be reasonable (though I’m not convinced they are in our tiny market and in these times of an embattled film business), the tactic of trying to leverage an attack on this huge production at its most precarious point to gain advantage over an entire industry was grotesquely cynical and heavy-handed, and, as I say, driven out of Australia. Imagine SAG dictating to Canadian producers how they may or may not make Canadian films!

Whether the deal was unwisely caused by a pushy Australian union is a matter for debate. Whether the New Zealand government unreasonably bowed down to a big American studio is as well. But the deal that the two parties reached is a remarkable one, perhaps indicative of the way the film industry works in this day of global filmmaking.

Warner Bros. gets more money and a more stable labor situation. What’s in it for New Zealand? First, the incentives for large-budget films from abroad to be made in the country are raised. This comes not through an increase in the tax-rebate rate but an expansion of what it covers:

The Government revealed this week that the new rules would mean up to $20 million in extra money for Warner Bros via tax rebates, on top of the estimated $50 million to $60 million under the old rules.

While the details of the Large Budget Screen Production Grant remain under wraps, Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee said it would effectively increase the incentives for large productions to come to New Zealand.

The grant is a 15 per cent tax rebate available on eligible domestic spending. At the moment a production could claim the rebate on screen development and pre-production spending, or post-production and visual effects spending, but not both.

If the Government allowed both aspects to be eligible, it would be a large carrot to dangle in front of movie studios.

Mr Brownlee was giving little away yesterday but said the broader rules would apply only to productions worth more than US$150 million ($200 million).

It would bridge the gap “in a small way” between what New Zealand offered and what other countries could offer.

During this period, it was claimed that WB had already spent around $100 million on pre-production on The Hobbit, which has been going on for well over a year now. That figure presumably is in New Zealand currency.

There are some in New Zealand who oppose “taxpayer dollars” going to Warner Bros. As has been pointed out–though apparently not absorbed by a lot of people–Warner Bros. will spend a lot of money in New Zealand and get some of it back. The money wouldn’t be in the government’s coffers if the film weren’t made in the country. It’s not tax-payers’ money that could somehow be spent on something else if the production went abroad.

Another advantage for the country is the permanent Hobbiton set, which will no doubt increase tourism. There are fans who have already taken two or three tours of LOTR locations and will no doubt start saving up to take another.

One item that didn’t get noticed much during the deluge of news is that one of the two parts will have its world premiere in New Zealand. That’ll probably happen in the wonderful and historic Embassy theater, which was refurbished for the world premiere of The Return of the King. It was estimated that the influx of tourists and journalists for that event brought NZ$7 million to the city of Wellington. About $25 million in free publicity was provided by the international media coverage.

The Embassy in October 2003, being prepared for the Return of the King world premiere.

The deal also essentially makes the government of New Zealand into a brand partner with New Line to provide mutual publicity for The Hobbit. As I describe in Chapter 10 of The Frodo Franchise, the government used LOTR to “rebrand” the entire country. It worked spectacularly well and had a ripple effect through many sectors of society outside filmmaking. The country came to be known more for its beauty, its creativity, and its technical innovations than for its 40 million sheep. Now in the deal over The Hobbit, the government has committed to providing NZ$13 million for WB’s publicity campaign. But the money will also go to draw business and tourists. As TVNZ reported:

But the Prime Minister says for the other $13 million in marketing subsidies, the country’s tourism industry gets plenty in return.

“Warner Brothers has never done this before so they were reluctant participants, but we argued strongly,” Key said.

Every DVD and download of The Hobbit will also feature a Jackson-directed video promoting New Zealand as a tourist and filmmaking destination.

Graeme Mason of the New Zealand Film Commission says the promotional video will be invaluable.

“As someone who’s worked internationally for most of my life, you can’t quantify how much that is worth. That’s advertising you simply could not buy.”

If the first Hobbit film is as popular as the last Lord of the Rings movie, the promotional video could feature on 50 million DVDs.

Suzanne Carter of Tourism New Zealand agrees having The Hobbit production here is a dream come true.

“The opportunity to showcase New Zealand internationally both on the screen and now in living rooms around the world is a dream come true,” Carter said.

Marketing expert Paul Sinclair says the $13 million subsidy works out at 26 cents a DVD.

“It’s a bargain. It is gold literally for New Zealand, for brand New Zealand,” he said.

It’s not clear how the promotional partnership will be handled. There was a similar, if smaller partnership when LOTR was made. New Line permitted Investment New Zealand, Tourism New Zealand, the New Zealand Film Commission, and Film New Zealand to use the phrase, “New Zealand, Home of Middle-earth” without paying a licensing fee. (Air New Zealand was an actual brand partner during the LOTR years.) But for the government to actually underwrite the studio’s promotional campaign may entail more. That deal is more like the traditional brand partnership, where the partner agrees to pay for a certain amount of publicity costs in exchange for the right to use motifs from the film in its advertising. Has a whole country ever brand-partnered a film? I can’t think of one.

In my book I wrote that LOTR “can fairly claim to be one of the most historically significant films ever made.” That’s partly why I wrote the book, to trace its influences in almost every aspect of film making, marketing, and merchandising–as well as its impact on the tiny New Zealand film industry that existed before the trilogy came there. Years later, I still think that my claim about the trilogy’s influences was right. When an obscure art film from Chile or Iran carries a credit for digital color grading, it shows that the procedure, pioneered for LOTR, has become nearly ubiquitous. There are many other examples. The troubled lead-up to The Hobbit‘s production and the solutions found to its problems suggest that it will carry on in its predecessor’s fashion, having long-term consequences beyond boosting Warner Bros.’ bottom line. It will be interesting to see if other big studios announce they will film in one country and then find ways of maneuvering better terms by threatening to leave–or by actually leaving.

From Worldwide Hippies