Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

What makes Hollywood run?

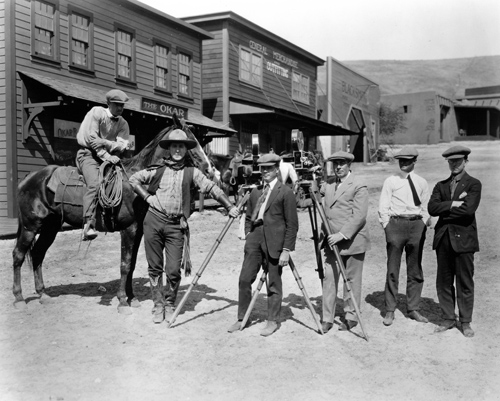

William S. Hart and crew at Inceville, 1910s.

DB here:

For decades most people had a sketchy idea of The Hollywood Studio Film. Boy meets girl, glamorous close-ups, spectacular dance numbers or battle scenes, happy endings, fade-out on the clinch. But even if such clichés were accurate, they didn’t cut very deep or capture a lot of other things about the movies. Could we go farther and, suspending judgments pro or con the Dream Factory, characterize U. S. studio filmmaking as an artistic tradition worth studying in depth? Could we explain how it came to be a distinctive tradition, and how that tradition was maintained?

In 1985 Routledge and Kegan Paul of London published The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote it. Since it’s rare for an academic film book to remain in print for twenty-five years, we thought we’d take the occasion of its anniversary to think about it again. Those thoughts can be found in the adjacent web essay, where we three discuss what we tried to do in the book, spiced with comments about areas of disagreement and more recent thoughts. This blog entry is just a teaser.

A touch of classical

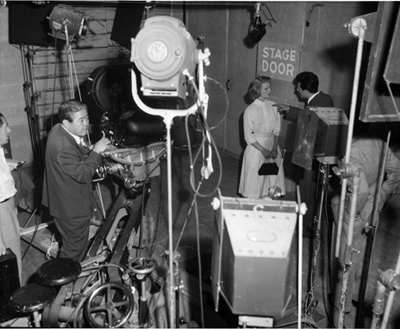

John Arnold, a Bell & Howell camera, and Renée Adorée in 1927.

The prospect of analyzing Hollywood as offering a distinctive approach to cinematic storytelling emerged slowly. The earliest generations of film historians tended to talk about the emergence of film techniques in a rather general way. For example, historians were likely to trace the development of editing as a general expressive resource, appearing in all sorts of movies. While they recognized that, say, the Soviet filmmakers made unusual uses of this technique, writers still tended to think of editing as either a fundamental film technique or a very specific one—e.g., Eisenstein’s personal approach to editing.

An alternative approach was to understand the history of film as an art as a stream of cinematic traditions, or modes of representation, within which filmmakers worked. From this angle, there was a Hollywood or “standard” or “mainstream” conception of editing, and this didn’t exhaust all the creative possibilities of the technique. But it went beyond the inclinations of any particular director. People had long recognized that there were group styles, like German Expressionism and Italian Neorealism, but it took longer to start to think of mainstream moviemaking as, in a sense, a very broad and fairly diverse group style.

In the late 1940s André Bazin and his contemporaries started to point out that different sorts of films had standardized their forms and styles quite considerably. Bazin attributed the success of Hollywood cinema to what he called “the genius of the system.” In my view, his phrase referred not to the studio system as a business enterprise but rather to an artistic tradition based on solid genres and a standardized approach to cinematic narration. This artistic system, he suggested, had influenced other cinemas, creating a sort of international film language.

The idea that there was a dominant filmmaking style, tied to American studio moviemaking, was developed in more depth during the 1960s and 1970s. Christian Metz’s Grande Syntagmatique of narrative film pointed toward alternative technical choices available in the “ordinary film.” Raymond Bellour’s analysis of The Birds, The Big Sleep, and other films pointed to a fundamental dynamic of repetition and difference governing American studio cinema. Somewhat in the manner of Roland Barthes’ S/z, Thierry Kuntzel’s essays explored M and The Most Dangerous Game looking for underlying representational processes that were characteristic of studio films. From a somewhat different angle, in the book Praxis du cinema and later essays Noël Burch traced out a dominant set of techniques that formed what he would eventually call the “Institutional Mode of Representation.” The Cahiers du cinéma critics famously posited different categories of filmic construction, each one tied to the representation of ideology. In English, Raymond Durgnat was an early advocate of studying what he called the “ancienne vague,” the conventional filmmaking that young directors were rebelling against.

The trend was given a new thrust by the British journal Screen, which disseminated the idea of a “classical narrative cinema,” a mode of representation characterized by distinctive dynamics of story, style, and ideology. Perhaps the most emblematic article of this sort was Stephen Heath’s in-depth analysis of Touch of Evil. Over the same years a new generation of film historians was studying early cinema with unprecedented care, and they too were finding a variety of modes of representation at work in filmmaking of the pre-1920 era.

The effect was to relativize our understanding of Hollywood. Mainstream U. S. commercial filmmaking wasn’t the cinema, merely one branch of film history, one way of making movies. Breaking a scene into a coherent set of shots, to take the earlier example, wasn’t Editing as such. It was one creative choice, although it had become the dominant one. And what made Hollywood’s brand of coherence the only option? Eisenstein, Resnais, Godard, and other filmmakers explored unorthodox alternatives.

Nearly all of the influential research programs of the period emphasized the film as a “text.” This wasn’t surprising, since several of the writers were working with concepts derived from literary semiotics and structuralism. At the same period, other scholars were developing ideas about Hollywood as a business enterprise. Douglas Gomery, Tino Balio, and a few others were showing that the studio system was just that—a system of industrial practices with its own strategies of organization and conduct. But most of those business studies did not touch on the way the movies looked and sounded, or the way they told their stories.

Could the two strains of research be integrated? Could one go more deeply into the films and extract some pervasive principles of construction? And could one go beyond the films and show how those principles of style and story connected to the film industry?

The prospect of integrating these various aspects—and, naturally, of finding out new things—intrigued us.

Secrets of the system

Main Street to Broadway (1953, MGM release). Cinematographer James Wong Howe on left.

The overall layout of CHC tried to answer these questions while weaving together a historical overview. Part One, written by me, provided a model or ideal type of a classical film, in its narrative and stylistic construction. Part Two, by Janet, outlined the development of the Hollywood mode of production until 1930. In Park Three, Kristin traced the origins and crystallization of the style, from 1909 to 1928. Part Four included chapters by all three authors on the role of technology in standardizing and altering classical procedures during the silent and early sound era. In Part Five Janet resumed her account of the mode of production, tracing changes from 1930 to 1960. The technology thread was brought up to date in Part Six, where I discussed deep-focus cinematography, Technicolor, and the emergence of widescreen cinema. Part seven, which Janet and I wrote together, pointed out implications of the study and suggested how Hollywood compared with alternative modes of film practice.

Clearly, CHC was several books in one. Janet could easily have written a free-standing account of the mode of production. Kristin could have done a book on silent film technique and technology. I could have focused on style and form, using sound-era technologies as test cases. The point of interspersing all these studies (and creating a slightly cumbersome string of authorial tags within sections) was to trace interdependences. For instance, Kristin examined the emerging stylistic standardization in the 1910s. Janet showed how that standardization was facilitated by a systematic division of labor and hierarchy of control, centered around the continuity script. At the same time, the organization of work was designed to permit novelties in the finished product, a process of differentiation that is important in any entertainment business.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

In the late 1920s, for instance, sound recording made the camera heavier than the tripods of the silent era could bear. Supply firms engineered “camera carriages” that could wheel the beast from setup to setup. But this development occurred soon after filmmakers had noticed the expressive advantages of the “unleashed camera” in German films and some American ones. So the camera carriage became a dolly, redesigned to permit moving the camera while filming. It’s not that there weren’t moving-camera shots before, of course, but with the camera permanently on a mobile base, tracking and reframing shots could play a bigger role in a scene’s visual texture. Similarly, studio demands for ways of representing actors’ faces in close-ups forced Technicolor engineers back to their drawing boards again and again. Once the problem of rendering faces pleasant in color was solved, filmmakers could then redesign their sets and adjust their make-up to suit the vibrant three-strip process. And the interaction of work, tools, and style triggered larger cycles of activity. The need to pool information about stylistic demands and technological possibilities helped foster the growth of professional associations and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

This give-and-take among the studios, the supply sector, and the stylistic norms had never been discussed before, and we couldn’t have done justice to it in separately published books. Nor could isolated studies have easily traced how industrial discourses—the articles in trade journals, the communication among the major players—helped weld the mode of production to artistic choices about filmic storytelling.

The Classical Hollywood Cinema was generously reviewed, in terms that made us feel our hard work had been worth it. Books we’ve written since haven’t been so widely acclaimed. (Nothing like peaking young.) We’re grateful to the reviewers who praised the book, and to the teachers and students who have strengthened their biceps by picking it up to read. Of course there are others who don’t consider the project worthwhile; the TLS reviewer called it “sludge.” Probably nothing we say in the accompanying essay will persuade those readers to take a second look. Without responding to all the criticisms the book received (that would take a book in itself), our accompanying essay tries to position this 1985 project within our current lines of thinking.

We studied how Hollywood routinized its work, but that doesn’t mean that we think division of labor is always alienating. It may produce a much better outcome than do the efforts of a solitary individual. For us, that’s what happened during this rewarding exercise in collaboration.

Our thinking was shaped by many sources; here are some of them.

For André Bazin on “the genius of the system,” see “La Politique des auteurs,” in The New Wave, ed. Peter Graham (New York: Doubleday, 1968), pp. 143, 154, and “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), pp. 23-40. Christian Metz explains the Grande Syntagmatique of the image track in “Problems of Denotation in the Fiction Film,” Film Language, trans. Michael Taylor (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 108-146. Raymond Bellour’s essays of the period are available in The Analysis of Film. Thierry Kuntzel’s essay on The Most Dangerous Game was translated into English as “The Film-Work 2,” Camera Obscura no. 5 (1980), 7-68. An important gathering of essays in this line of inquiry is Dominique Noguez, ed., Cinéma: Théorie, lectures (Paris: Klincksieck, 1973).

Noël Burch’s early ideas are set out in Theory of Film Practice, trans. Helen R. Lane (New York: Prager, 1973). Even more important to our project was Noël Burch and Jorge Dana, “Propositions,” Afterimage no. 5 (Spring 1974), 40-66, and Burch’s To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film (London: Scolar Press, 1979), available online here.

Raymond Durgnat’s series, “Images of the Mind,” deserves to be republished, preferably online. The most relevant installments for this entry are “Throwaway Movies,” Films and Filming 14, 10 (July 1968), 5-10; “Part Two,” Films and Filming 14, 11 (August 1968), 13-17; and “The Impossible Takes a Little Longer,” Films and Filming 14, 12 September 1968), 13-16. Stephen Heath’s analysis of Touch of Evil may be found in “Film and System: Terms of Analysis,” Screen 16, 1 (Spring 1975), 91-113 and 16, 2 (Summer 1975), 91-113.

Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (London: Starword, 1983) works in comparable areas to CHC, though without our interest in industry-based sources of stability and change. The newest edition is here.

Tino Balio’s courses and his collection The American Film Industry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) had a substantial influence on us. He has been a wonderful friend and guide for us all since the 1970s. Our friendship with Douglas Gomery dates from our early days in Madison. Many conversations, along with his teaching in our program, shaped our thinking. A good summing up his of decades of work on the business and economics of Hollywood is The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

Some of the stylistic traditions discussed in this entry are discussed in my On the History of Film Style. Several blog entries on this site fill in more details; click on the category “Hollywood: Artistic traditions.”

PS 26 September 2010: Douglas Gomery reminds me that the idea of sampling Hollywood films in an unbiased fashion–one feature of our method in CHC–was suggested to us by Marilyn Moon, economist extraordinaire. I’m happy to thank Marilyn, along with Joanne Cantor and Douglas himself, who helped us devise a sampling procedure.

Actors and set for Blondie Johnson (Warners, 1933).

Dragons on your doorstep

DB here:

Once more, Hong Kong. Still a spellbinding place, although the municipality is doing whatever it can to force pedestrians underground and surrender the streets to cars. Even a dragon has to wait for the pedestrian light. And now, thanks to the sandstorms in China, the air is thick with pollution. I have taken defensive measures. My students probably wished I’d worn one of these more often.

Yes, that is the Boy Scout logo behind me. Why? Answer here.

I’ve already seen a few films at the Hong Kong International Film Festival, but I’ll try as usual to fold my viewings into a few thematically related entries. In the meantime, amateur reportage and celebrity gawking take over. I’m surface-skimming, I grant you, but it’s quite a surface.

For some years now, the festival has meshed with Filmart, the regional film market and trade show, and the Asian Film Awards. So you need badges.

For most of this week, the big events take place at the Hong Kong Convention Centre.

The opening reception for the festival offered all the glitter you can ask for, literally, when a cascade of sparkling paper showered down on the group photo of the organizers.

Among those present: Tang Wei, star of Lust, Caution and featured alongside Jacky Cheung in Ivy Ho’s festival-opener Crossing Hennessy.

Then there was Lisa Lu, radiant as ever. She was a wonderful star in Shaws’ golden age and continues to visit the festival annually, while sustaining her acting career.

Clara Law, director of one of the opening films, Like a Dream, embraces Lisa while Nansun Shi, herself a legendary and still central Hong Kong producer, looks on.

Filmart this year teemed with mainland Chinese media firms, but the classic Hong Kong companies also put in their appearance.

It’s reassuring to see that Wong Jing, the brains behind Naked Killer and Naked Weapon, hasn’t abandoned his old ways.

New regional enterprises are emerging. Patrick Frater and Steven Cremin, old Asian hands, have created FilmBusinessAsia as a resource of news, industry analysis, and in-depth information. Based in Hong Kong, they are ably teamed with Business Development Executive Gurjeet Chima, who speaks five languages.

Anyone interested in Asian film will find their information-packed website a must.

Two more entrepreneurs are Joey Leung and Linh La of Terracotta Distribution, a London-based outfit with an already impressive library. I met them through King Wei-chu, on the right, a programmer for Montreal’s FantAsia.

Three-dimensional film and TV were all over Filmart. Take a look at a 3D setup using the Red HD camera.

What a contraption! To shoot Potemkin, Napoleon, and a host of other 1920s films, you just needed a Debrie Parvo, that model of Style Moderne design.

Still, 3D television seems more or less ready for prime time. Can you tell the difference between reality and a 3D image?

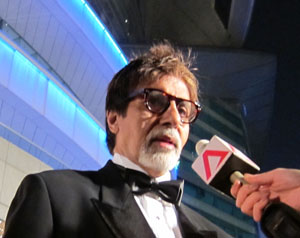

Also at the Convention Centre was the Asian Film Awards ceremony, which whizzed by in two hours. On the red carpet runway you could see some celebrities, such as Wai Ying-hung, a Shaw Brothers ingenue and kung-fu warrior from the 1980s who would win for best supporting actress in Ho Yuhang‘s At the End of Daybreak.

Among the slinky models and standard-issue teen idols on the red carpet, a note of dignity was struck by Amitabh Bachchan, who got a lifetime achievement award. He might as well officially change his name to Megastar Amitabh Bachchan.

For a complete rundown on the award winners, you can go here. We wrote about three of them in earlier blog entries: Bong Joon-ho‘s Mother (best picture, best actress, best screenplay), Ho Yuhang‘s At the End of Daybreak (best newcomer, best supporting actress) and Chris Chong‘s Karaoke (best editing). Among the nominees, we also wrote about Love Exposure, About Elly (I really wish it had won something), Cow, Air Doll, and Breathless. I was particularly struck by the cheers and whoops the audience gave Wang Xueqi of Bodyguards and Assassins, which I caught up with today. He’s an actor of gravity, who unlike most Hong Kong performers believes that less (hamming) is more (engrossing).

With the big launching events over, we can get down to the real business: Watching movies and discovering some sublimity in them. More entries, as usual, to come.

Her design for living

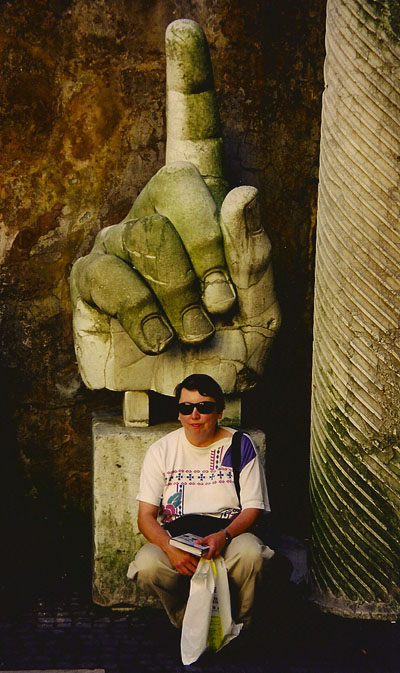

Kristin in Rome, 1997, in front of a “recent” hand from a colossal statue of Constantine. The Amarna statuary fragments she studies are twice as old.

DB here:

Kristin is in the spotlight today, and why not? She’s too modest to boast about all the good things coming her way, but I have no shame.

First, our web tsarina Meg Hamel recently installed, in the column on the left, Kristin’s 1985 book Exporting Entertainment: America in the World Film Market 1907-1934. It was never really available in the US and went out of print fairly quickly. Vito Adriaensens of Antwerp kindly scanned it to pdf and made it available for us. So we make it available to you. More about Exporting Entertainment later.

Second, Kristin is not only a film historian but a scholar of ancient Egyptian art, specifically of the Amarna period. (These are the years of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and their highly unsuccessful experiment in monotheism.) Every year she goes to Egypt to participate in an expedition that maps and excavates the city of Amarna. In recent years she’s focused on statuary, about which she’s given papers and published articles. Now we’ve learned that she has won a Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fellowship to work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection for a month during the next academic year. So at some point then we’ll both be blogging from NYC. Think of the RKO Radio tower sending our signals to a tiny world below.

Third, she is about to turn 60, and in her honor the Communication Arts Department is sponsoring a day-long symposium. On 1 May we’ll be hosting Henry Jenkins, Charlie Keil, Janet Staiger, and Yuri Tsivian to give talks on topics related to her career interests. Kristin’s talk will survey her Egyptological work, with observations on how she has applied analytical methods she developed in her film research. You can get all the information about the event, as well as find places to stay in Madison, here.

Kristin came to Madison in 1973, a very good moment. Whatever you were interested in, from radical politics to chess to necromancy (there was a witchcraft paraphernalia shop off State Street), you could find plenty of people to obsess with you. Film was one such obsession.

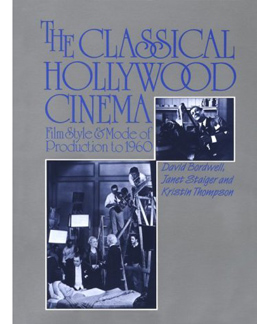

The campus boasted about twenty registered film societies, some screening several shows a week. Fertile Valley, the Green Lantern, Wisconsin Film Society, Hal 2000, and many others came and went, showing 16mm films in big classrooms in those days before home video. Without the internet, publicity was executed through posters stapled to kiosks, and the fight for space could get rough. Posters were torn down or set on fire; a charred kiosk was a common sight. Another trick was to call up distributors and cancel your rivals’ bookings. One film-club macher reported that a competitor had cut his brake-lines.

What could you see? A sample is above. What it doesn’t show is that in an earlier weekend of February of 1975, your menu included Take the Money and Run, The Lovers, Ray’s The Adversary, Page of Madness, Fritz the Cat, The Ruling Class, Dovzhenko’s Shors, Chaney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, American Graffiti, Wedding in Blood, Pat and Mike, Camille, Yojimbo, Faces, Days and Nights in the Forest, King of Hearts (a perennial), Sahara, The Fox, Day of the Jackal, Dumbo, Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion, Slaughterhouse-Five, Mean Streets, A Fistful of Dollars, Triumph of the Will, and The Cow. Not counting the films we were showing in our courses.

In addition, there was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, recently endowed with thousands of prints of classic Warners, RKO, and Monogram titles. (There were also TV shows, thousands of document files, and nearly two million still photos.) When Kristin got here she immediately signed up to watch all those items she had been dying to see. She suggested that the Center needed flatbed viewers to do justice to the collection, and director Tino Balio promptly bought some. Those Steenbecks are still in use.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Above all there were the people. The department had only three film studies profs–Tino, Russell Merritt, and me–though eventually Jeanne Allen and Joe Anderson joined us. Posses of other experts were roaming the streets, running film societies, writing for The Daily Cardinal, authoring books, and editing the Light Trap. Who? Russell Campbell, John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tom Flinn, Tim Onosko, Gerry Perry, Danny Peary, Pat McGilligan, Mark Bergman, Sid Chatterjee, Richard Lippe, Harry Reed, Michael Wilmington, Joe McBride, Karyn Kay, Reid Rosefelt, Dean Kuehn, Samantha Coughlin, and Bill Banning. Most of these were undergraduates, but Maureen Turim and Diane Waldman and Douglas Gomery and Frank Scheide and Peter Lehman and Marilyn Campbell and Roxanne Glasberg and other grad students could be found hanging out with them. A great many of this crew went on to careers as writers, teachers, scholars, programmers, filmmakers, and film entrepreneurs.

Into the mix went film artists like Jim Benning, Bette Gordon, and Michelle Citron. There were film collectors too; one owned a 70mm print of 2001 and didn’t care that he could never screen it. ZAZ, aka the Zucker brothers and Jim Abrahams, were concocting Kentucky Fried Theater. Andrew Bergman had recently published We’re in the Money, and soon Werner Herzog would be in Plainfield waiting for Errol Morris to help him dig up Ed Gein’s grave. Set it all to the musical stylings of R. Cameron Monschein, who once led an orchestra the whole frenzied way through Intolerance. The 70s in Madison were more than disco and the oil embargo. (To catch up on some Mad City movie folk, go here.)

These young bravos worked with the same manic passion as today’s bloggers. The purpose wasn’t profit, but living in sin with the movies. Film society mavens drove to Chicago for 48-hour marathons mounted by distributors. Traditions and cults sprang up: Sam Fuller double features, noir weekends, hours of debates in programming committees. Why couldn’t Curtiz be seen as the equal of Hawks? Why weren’t more Siodmak Universals available for rental? Was Johnny Guitar the best movie ever made, or just one of the three best?

There was local pride as well. Nick Ray had come from Wisconsin, and so had Joseph Losey, not to mention Orson Welles (who claimed, however, that he was conceived in Buenos Aires and thus Latin American). During my job interview, Ray came to visit wearing an eye patch. It shifted from eye to eye as lighting conditions changed. When he showed a student how to set up a shot, he bent over the viewfinder and lifted the patch to peer in. Was he saving one eye just for shooting?

In the big world outside, modern film studies was emerging and incorporating theories coming from Paris and London. Partly in order to teach myself what was going on, I mounted courses centering on semiotics, structuralism, Russian Formalism, and Marxist/ feminist ideological critique.

Back in placid Iowa City, where Kristin got her MA in film studies and I my Ph.D., we grad students had seen our mission clearly. Steeped in theory, we pledged to make film studies something intellectually serious: a genuine research enterprise, not mere cinephilia. Madison was the perfect challenge. Here cinephilia was raised to the level of thermonuclear negotiation, backed with batteries of memos, scripts, and scenes from obscure B-pictures. Confronted with a maniacal film culture and a vast archive, Kristin and I realized that there was so much to know–so many films, so much historical context–that any theory might be killed by the right fact.

Watch a broad range of movies; look as closely as you can at the films and their proximate and pertinent contexts; build your generalizations with an eye on the details. Our aim became a mixture of analysis, historical research, and theories sensitively contoured to both. The noisy irreverence of Mad City, where a former SDS leader had just been elected mayor and city alders could be arrested for setting bonfires on Halloween, wouldn’t let you stay stuffy long.

Kristin’s work in film studies would be instantly recognizable to humanists studying the arts. Essentially, she tries to get to know a film as intimately as possible, in its formal dimensions–its use of plot and story, its manipulations of film technique. I suppose she’s best known for developing a perspective she called Neoformalism, an extension of ideas from the Russian Formalists. Armed with these theories, she has studied principles of narrative in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. She has probed film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and her sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. And she has examined narrative and style together in her book on Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible and the essays in Breaking the Glass Armor.

Contrary to what commonsense understanding of “formalism” implies, she has always framed her questions about form and style in a historical context. She situates classic and contemporary Hollywood within changes in the film industry–the development of early storytelling out of theatre and literature, or current trends responding to franchises and tentpole films. For her, Lubitsch’s silent work links the older-style postwar German cinema and the more innovative techniques of Hollywood. She situates Tati, Ozu, Eisenstein, and other directors in the broad context of international developments, while keeping a focus on their unique uses of the film medium.

Perhaps her most ambitious accomplishment in this vein is her contribution to Film History: An Introduction. She wrote most of the book’s first half, and though I’m aware of the faults of my sections, I find hers splendid. After twenty years of research, she produced the most nuanced account we have yet seen of the international development of artistic trends in American and European silent film.

Kristin has also illuminated the history of the international film industry. Everybody knows that Hollywood dominates world film markets. The interesting question is: How did this happen? Exporting Entertainment provides some surprising answers by situating film traffic in the context of international trade and changing business strategies. One twist: the importance of the Latin American market. The book also opened up inquiry into “Film Europe,” a 1920s international trend that tried to block Hollywood’s power. In all, Exporting Entertainment led other researchers to pursue the question of film trade, and I was gratified to see that Sir David Puttnam’s diagnosis of the European film industry, Undeclared War, made use of Kristin’s research.

More recently, Kristin has turned her attention to the contemporary industry, the main result of which has been The Frodo Franchise, a study of how a tentpole trilogy and its ancillaries were made, marketed, and consumed. Her love of Tolkien and her respect for Peter Jackson’s desire to do LotR justice led her to study this massive enterprise as an example of moviemaking in the age of winning the weekend and satisfying fans on the internet. She maintains her Frodo Franchise blog on a wing of this site.

Most readers of this blog know Kristin as a film scholar. They may be surprised to learn that she also wrote a book on P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster books. Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes; or, Le Mot Juste is a remarkable piece of literary criticism. Here she shows how Wodehouse developed his own templates for plot structure and style. Again, the analysis is grounded in research–in this case, among Wodehouse’s papers. So assiduously did she plumb Plum that she became the official archivist of the Wodehouse estate. This is also, page for page, the funniest book she has yet written.

Her Egyptological work is no joke, though, and she has become one of the world’s experts on Amarna statues. She has published articles and given talks at the British Museum and other venues. Soon she’ll trek off for her ninth season at Amarna. There, joined by her collaborator, a curator at the Metropolitan, she’ll study the thousands of fragments that she’s registered in the workroom seen above. It’s preparation for a hefty tome on the statuary in the ancient city.

You can learn more about Kristin’s career here, in her own words. These are mine, and extravagant as they are, they don’t do justice to her searching intelligence, her persistent effort to answer hard questions, and her patience in putting up with my follies and delusions. You’d be welcome to visit her symposium and see her, and people who admire her, in action. While you’re here, you can watch a restored print of Design for Living, by one of her favorite directors, screening at our Cinematheque. In 35mm, of course. We can’t shame our heritage.

Poster design by Heather Heckman. Check out our Facebook page too.

Daisies in the crevices

DB here:

If you wanted a prototype of some unique visual pleasures of 1930s cinema, you could do worse than pick this innocuous image. It’s perfunctory in narrative terms, merely telling us that Sylvia Day is calling on Bill Smith. Beyond its plot function, though, it’s fun to see. We can enjoy the unfussy modern edge of the doorjamb, the curve of the manicured thumb, and soft highlights bringing out the hand and knuckles.

Above all, there is that starry gleam at the top of the doorbell. Who needs it? It’s just a doorbell. Why take so much trouble lighting a throwaway shot?

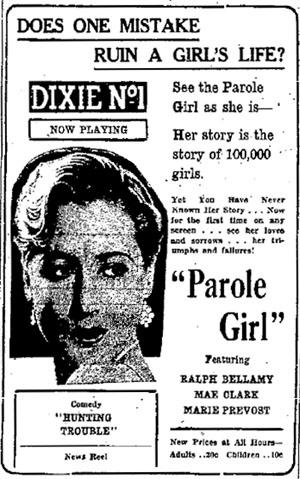

Add to this that Parole Girl (1933) is a program picture, and from Columbia, no less—the Poverty Row studio that had yet to break through with It Happened One Night (1934). We learn from Bernard F. Dick’s deeply-researched book on Harry Cohn that the budget for Parole Girl would have been about $250,000, when MGM B’s were running about $400,000. Why spend money on a shot like this?

Because that was the standard of good-looking moviemaking at the time. Most problems of converting to talkies had been solved, so films were regaining not only the fluent narration but the sparkling imagery of 1920s cinema. Under Cohn’s leadership, Columbia was trying to compete with the bigger studios’ movies, and looking classy was one way to do it. Recently I spent a day or so watching four titles, and I was reminded how pictorially sophisticated and refreshing low-end Hollywood can be. These movies also offer us an unusual window into what was already characteristic storytelling strategies of classical Hollywood. But there will be spoilers ahead too.

Welcome to 1933

As so often, I have TCM to thank. Since their Jean Arthur tribute of 2007, they have been running a generous number of Columbia titles (all restored by the master hand of Grover Crisp). By including less-known 1930s items along with classics like The Awful Truth and the Capra titles, they continue their mission of serving American film culture every hour.

Lea Jacobs has convinced me that it’s useful to think of studio releases in those days as filling a season running from Labor Day to Memorial Day rather than a calendar year. Studio heads planned budgets and production schedules according to that time frame, like network TV broadcasters now. Unlike today, summer was not a big release period, maybe because of the competition of other leisure activities, maybe because with air-conditioned movie houses people would come watch anything thrown on the screen. In any case, the big pictures were saved for fall, winter, and spring.

So my frame of reference is the 1932-33 season. Columbia ushered in the new year with its best-remembered film of the season, Capra’s Bitter Tea of General Yen (6 January). The studio probably considered Washington Merry-Go-Round (15 October), Virtue (25 October), and No More Orchids (15 November) to be A projects, but the large output of Westerns, the absence of historical pictures, and the relative dearth of stars in this output confirm the studio’s status as a Poverty Row company.

My movies come from the winter and spring of 1933. Each was shot in two to three weeks and each runs about seventy minutes.

Air Hostess (15 January, directed by Albert Rogell) tells of the daughter of a WWI ace who marries a reckless young pilot. Trying to build a new type of plane, he shops his business plans to a rich woman investor, who tries to seduce him.

In Child of Manhattan (4 February, directed by Edward Buzzell), a wealthy widower falls for a taxi dancer and takes her as his mistress. When she becomes pregnant, he marries her. But the baby dies soon after birth and the wife flees to Mexico for a divorce while the husband tries to track her down.

In Parole Girl (4 March, directed by Edward Cline), a department store executive sends a woman con artist to prison. She vows revenge. When she gets out, she seduces the executive, although he’s unaware of who she is.

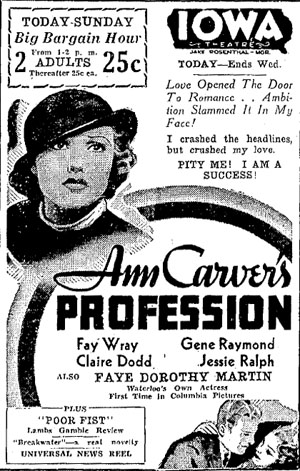

Ann Carver’s Profession (26 May 1933, directed by Buzzell) centers on a couple torn by career rivalry. After being a gridiron hero in college, the husband is failing as an architect. Meanwhile, his wife is becoming a celebrated trial lawyer. Eventually the husband leaves the household and takes up with a floozie, who winds up strangled. His wife must defend him against the murder charge.

For connoisseurs of naughty pre-Code movies, there are the usual attractions of double beds, extramarital sex, peekaboo negligees, and risqué dialogue. Child of Manhattan goes the farthest, perhaps because it’s an adaptation of a Preston Sturges play. “You’re a fascinating little witch,” says the millionaire. “Did you say witch?” the dancer asks. This is the same girl, played by perky Nancy Carroll, who thinks the man is trying to feel her up when he slips a thousand-dollar bill into her garter. Later she recalls her mother’s advice: “Never, ever walk upstairs in front of a gentleman.” And when she confesses to her Texan admirer in her mangled pronunciation, “I’m a courtesian,” he pauses and replies, “Well, religion doesn’t make any difference with me.”

Despite such pleasant moments, and two screenplays credited to Robert Riskin and Norman Krasna, these movies won’t win prizes for imaginative scripting. The tone is often uncertain, with comic banter clashing with scenes of melodramatic sacrifice. The long arm of coincidence becomes elastic. In Parole Girl, the heroine happens to meet the offending executive’s first wife in prison. During the taxi dancer’s stay in Mexico, she runs into the cowpoke who had wooed her aggressively in Manhattan. In Ann Carver’s Profession, the husband’s girlfriend accidentally strangles herself. Yes, you read that correctly.

Still, you have to give points for speed. Only Parole Girl has unusually quick cutting, at an average of 6.6 seconds per shot, but the overall pace of most of the plots is pretty rapid. (The exception is Child of Manhattan, whose lumbering dramatic rhythm is echoed in an average shot length of sixteen seconds.) Playing far-fetched action fast makes it less noticeable and more forgivable. Today any movie that can tell a moderately interesting story in a little more than an hour feels like a triumph. You can watch two of my pictures in the time it takes to groan your way through Funny People. And in these movies, the opening credits flash by in less than fifty seconds. Those were the days when crafts people under contract didn’t have to be acknowledged, and there were no executive producers.

Apart from Capra, whom do we remember as a Columbia director? Probably not my three guys. Albert Rogell, director of Air Hostess, began directing in the early 20s and worked for Columbia, Tiffany, Monogram, RKO, Universal, and Paramount. A prototypical B filmmaker, he signed over a hundred films in twenty-five years. Edward Buzzell was somewhat more prominent. After Ann Carver’s Profession, he left Columbia for Universal and eventually moved to MGM, where he directed (as if that were possible) the Marx Brothers in At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940), as well as helming Song of the Thin Man (1947). Like Rogell, Edward Cline (Parole Girl) skipped among studios; like Buzzell, he landed on his feet with comedian comedy, steering W. C. Fields through You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man (1939), My Little Chickadee (1940), and other vehicles. In all, studio artisans, yes; auteurs, no.

Two Joes and a Ted

Parole Girl

If you’re interested in how Hollywood tells its tales, there’s a fair amount to chew on in these modest releases. The scripts tend to obey Kristin’s four-part model, adapted to very short running times, with the key turning point taking place midway through the film. Despite the coincidences, the characters’ goals and changes of heart tend to be planted early. In Ann Carver’s Profession, Ann’s intense ambition and Bill’s swaggering overconfidence prepare us for the crisis in their marriage, when each is unwilling to compromise.

As for performances, perhaps the very speed of production forced actors to play naturally. True, Fay Wray is a bit arch as Ann Carver, but Gene Raymond as her husband moves convincingly from boisterousness to self-doubt. In Child of Manhattan, John Boles, trying to mingle with the little people, can be stiff, but Nancy Carroll has pep, and Buck Jones as her cowboy swain adds a welcome dose of naive gallantry. All three show how important distinct voices had already become: Boles mellifluous, Carroll up and down the scale, Jones slow and sincere. Reliable Columbia regular Ralph Bellamy shows up in Parole Girl, but more memorable is the performance, or rather presence, of Mae Clark. When she comes back from prison bent on vengeance, she’s a glowering figure in her stylishly chopped hairdo.

As for performances, perhaps the very speed of production forced actors to play naturally. True, Fay Wray is a bit arch as Ann Carver, but Gene Raymond as her husband moves convincingly from boisterousness to self-doubt. In Child of Manhattan, John Boles, trying to mingle with the little people, can be stiff, but Nancy Carroll has pep, and Buck Jones as her cowboy swain adds a welcome dose of naive gallantry. All three show how important distinct voices had already become: Boles mellifluous, Carroll up and down the scale, Jones slow and sincere. Reliable Columbia regular Ralph Bellamy shows up in Parole Girl, but more memorable is the performance, or rather presence, of Mae Clark. When she comes back from prison bent on vengeance, she’s a glowering figure in her stylishly chopped hairdo.

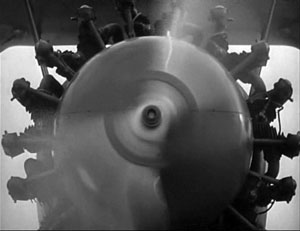

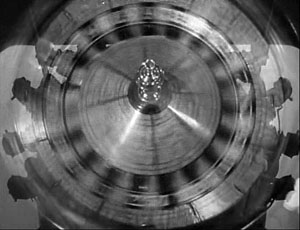

The films make fluent use of storytelling devices that predate the 1930s but are forever associated with that decade. Sequences are linked through headline montages and wipes, recently made possible by the optical printer. There are more elaborate techniques too, particular the visual or auditory hook connecting scenes. We’re not surprised to see commonplace instances, as when a note pad listing an apartment number dissolves to that number on the door. In Air Hostess, however, a spinning propeller gives way to a roulette wheel, and this association does a little more work, linking Ted Hunter’s reckless flying to his gambling and his general tendency to take risks.

In Child of Manhattan, as Madeleine resolves to leave her husband after the death of her child, she tearfully shakes a baby rattle, and this dissolves to marimbas in a nightclub, swiftly turning her pathos into her effort to start a new life with a Mexican divorce.

But what is perhaps most striking about these films is their photography. Ten minutes into Air Hostess, the first one I watched, we get a lovely sustained track into a sunny airfield, our view guided by the walkway wheeled up to a plane door as passengers step out.

The relaxed play of light and shadow in this geometrical shot yields one of those fugitive visual delights that classic cinema so often supplies.

What’s it doing in a Columbia programmer? This Poverty Row studio realized that they could give their pinched budgets an upscale look with polished cinematography. Accordingly, you can argue that the biggest talents on the Columbia lot were the directors of photography. Our four films were shot by ace DP’s.

Joe August (Parole Girl) was the grand old man. He filmed some of the best-looking hits of the 1910s, including Ince’s Civilization (1916) and a great many William S. Hart movies (including Hell’s Hinges, 1916). In the 1920s and up to 1932 he worked at Fox on films by Ford, Hawks, and Milestone. At Columbia August would shoot Borzage projects like Man’s Castle (1933) before moving to RKO for Sylvia Scarlett (1936), Dance, Girl, Dance (1940), and the flamboyant All That Money Can Buy (aka The Devil and Daniel Webster, 1940).

Another Joe, somewhat younger, was no less gifted. Joseph Walker, the DP of Air Hostess came to Columbia early and soon teamed with Capra; he would shoot twenty movies with the director, including the splendid American Madness (1932), a particular favorite of mine. Walker stayed loyal to Columbia, shooting Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), Penny Serenade (1941), and on and on—returning to Capra for the independent production It’s a Wonderful Life (1947). Walker also patented an original zoom-lens design.

Ted, sometimes known as Teddy, Tetzlaff was another Columbia loyalist, and he certainly cranked them out. Hawks’ The Criminal Code was one of eleven movies Tetzlaff was credited with in calendar 1931. But by the spring of 1933 he seems already to have become a free lance, eventually working at Paramount on a string of classics (Easy Living, Remember the Night, Road to Zanzibar), then RKO (The Enchanted Cottage, Notorious), and occasional jobs back at Columbia. Tetzlaff became a director as well, remembered chiefly for the cult classic The Window (1949).

No wonder my four films dazzle, even on TV. According to Bob Thomas’s biography King Cohn, Columbia took special care to create a phosphorescent look through careful processing that enhanced the DPs’ efforts. Hence not only the sparkle on a door buzzer but glowing applications of then-standard edge lighting. Hence as well the use of striped shadows to suggest venetian blinds, a convention we associate with the forties but here in precise array (Child of Manhattan, Parole Girl).

Trust Joe Walker to provide a little of that striped texture with a fuselage.

Hence too some striking depth. Here is the next-to-last shot of Walker’s work in Air Hostess, the sort of fancy aperture composition that crops up surprisingly often in the 1930s.

Tetzlaff, first in Child of Manhattan and then Ann Carver’s Profession, seems to be fooling around with faces and elbows.

Probably the most visually and narratively complex of my films from spring 1933 is Ann Carver’s Profession. It’s possible that it was Columbia’s equivalent of an A production: Gene Raymond was a mid-range star known for a few Paramount and MGM pictures, and Fay Wray’s King Kong had premiered a week before filming started. Whatever the cause, Ann Carver has more complex plotting and more consistently inventive visuals than the three other titles.

From the very start, when gridiron hero Bill promises to provide for Ann the waitress, we get the sort of offhand flash that I like in 1930s movies. As Bill follows Ann into the kitchen, she’s framed in a swinging door and the camera moves closer to pick up their clinch.

Once they’re married, the circle has become a rectangle, and trouble is on the way.

There are fancy mirror shots, pov constructions that lead characters to the wrong inferences, and examples of the big-foreground compositions that would come to prominence in the 1940s.

The trial recesses; crane up to the clock; spin the hands to cover a couple of hours; crane back to the trial resuming. Or start with Bill’s girlfriend, passed out and garroted by the necklace that has snagged on a leering chair carving. Dissolve to Bill’s night on the town, before ending that fuzzy montage with a dissolve back to the chair carving.

Bill didn’t kill her, but the pictorial logic makes him almost magically responsible, with the carving mocking him for what’s to come.

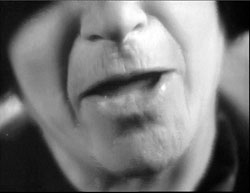

Above all there is one of the most laconic (and cheaply filmed) courtroom montages I’ve ever seen. A string of witnesses testifies, and after a newspaper pops out the first one, we get a fusillade of extreme close-ups, cut very quickly.

Just as striking is the coordinated sound montage, which reduces the testimony to clipped sentences, then phrases (“”Four-thirty!” “Quarter to five!” “Both of ‘em!”), then single words (“Drunk!” “Drunk!” “Strangulation!”), all damning Bill. Why take us through all the rigamarole—people sworn in and questioned at length—when you can give the essence of it in twenty-eight shots and twenty-five seconds?

My 1933 quartet contains no great film; perhaps none is worth more than one viewing. But what I learned from watching ordinary movies for our Classical Hollywood Cinema book is borne out by my soundings here. We can enjoy seeing a well-honed system steering us through a story, especially when gifted people like Teddy and the two Joes are shifting the gears. We can appreciate the opportunities for grace notes in what some call formula filmmaking. And we can see that this lowly studio, making films ignored in traditional histories, has something to teach filmmakers today: proud modesty. A film can radiate pride in being concise, in exercising a craft, and in telling a story that hurtles forward while shedding moments of casual beauty.

Most critical writing on early 1930s Columbia pictures focuses on Frank Capra, but there is good general background in Bernard F. Dick, The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row: Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009). My mention of budget levels comes from his discussion on pp. 119-120. An older, citation-free but still helpful biography is Bob Thomas, King Cohn (Beverly Hills: New Millennium, 2000). In-depth information on Joseph Walker as a Columbia cinematographer is available in Joseph McBride’s excellent biography Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 189-215. Walker’s engaging autobiography supplies nothing specific to these films, but he sprinkles technical information among its anecdotes. See Joseph Walker and Juanita Walker, The Light on Her Face (Los Angeles: ASC Press, 1984).

On 1934 as the end of naughtiness, see Tom Doherty’s Pre-Code Hollywood. For a skeptical account of the idea of Hollywood “before the Code,” see Richard Maltby, “More Sinned Against than Sinning [2003],” in Senses of Cinema here, and essays in “Rethinking the Production Code,” a special issue of The Quarterly Review of Film and Video 15, 4 (1995), ed. Lea Jacobs and Richard Maltby.

If you’re interested in more complicated narrative strategies in films of this period, try our entry “Grandmaster Flashback.” For another take on low-budget 1930s films, there’s our entry on Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan.