Archive for the 'Film music' Category

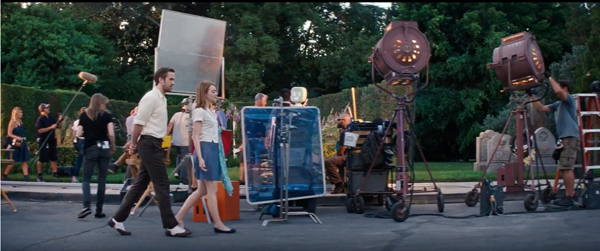

LA LA LAND: Singin’ in the sun

La La Land (2016).

DB here:

In our Film Studies program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, one of our aims is to integrate critical analysis of movies with a study of film history. Sometimes that means researching how conditions in the film industry shape and are shaped by the creative choices made by filmmakers. We also study how filmmakers draw on artistic norms, old or recent, in making new films. This effort to put films into wider historical contexts is something that you don’t get in your usual movie review.

Take, yet again, La La Land. Awards and critical debates continue to swirl around the surprising success of this neo-musical. Two entries on this blog have already considered what the film owes to 1940s innovations in Hollywood storytelling (here) and to more basic norms of movie plot construction and the classic Broadway “song plot” (here). But there’s plenty more to say.

Enter three Madison researchers as guest bloggers. Kelley Conway is an authority on the French musical from the 1930s to the present and author of an excellent book on Agnès Varda (reviewed here). She also gave us an earlier entry on films at the Vancouver Film Festival. Today, in an oblique rebuttal to some complaints about the principals’ singing and dancing in La La Land, she situates Damien Chazelle’s film within a trend toward “unprofessional” musical performance.

Eric Dienstfrey studies developments in acoustic technology and how those have affected the way movies sound. In his contribution, he traces how film’s recording methods shape the auditory texture of the numbers, with special attention to the soft boundary between diegetic (story-world) sound and non-diegetic sound.

Amanda McQueen is a specialist in Hollywood and TV musicals of the last fifty years. Here she considers how La La Land is designed to overcome audiences’ current resistance to “integrated” musicals. She proposes that it offers one way to revive the genre for modern Hollywood.

These experts take the conversation in new directions I think you’ll enjoy. They remind us that a movie coming out today automatically becomes a part of history; it’s just that the history is sometimes hard to discern. Along the way they show the virtues of thinking beyond the talking points put out by the PR machine or circulating endlessly in reviews. In my view, good film criticism involves ideas and information as well as opinions, and all three are on vivid display here.

Amateurism as authenticity

Everyone Says I Love You (Woody Allen, 1998).

Kelley Conway: For me, La La Land‘s references to classical Hollywood musicals and to the films of Jacques Demy provide a major source of its pleasure. (Sara Preciado’s video essay demonstrates the film’s homages) The film’s nods to other traditions remind us of something about the relationship between Hollywood and other national cinemas: mutual influence is the norm.

Directors associated with the French New Wave absorbed and subverted Hollywood genres. Hollywood directors of the late 1960s and ‘70s, in turn, were inspired by the narrative ambiguity and stylistic playfulness of the New Wave. Sometimes, the influence travels full circle in quite a direct way. John Huston’s Asphalt Jungle (1950) directly influenced Jean-Pierre Melville in the making of Bob le flambeur (1956), while Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs references both Melville’s minimalist gangster films and Hollywood heist films.

La La Land demonstrates a similarly rich exchange between Hollywood and France. In 1967, Jacques Demy’s Demoiselles de Rochefort paid loving homage to Hollywood films such as Singin’ in the Rain, West Side Story, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Chazelle’s film returns the favor, adopting the dancing pedestrians and location shooting of Demoiselles and the saturated colors, recitative, and downbeat ending of Parapluies de Cherbourg. Chazelle is equally smitten with classical Hollywood; La La Land brims with references to the choreography, costumes, and set design of Shall We Dance (1937), Singin’ in the Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953), West Side Story (1961), and many others.

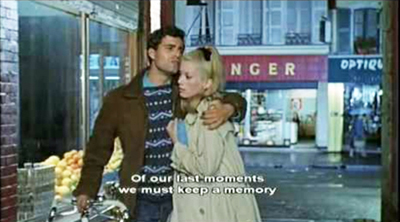

La La Land not only cites the style of other musicals, it also develops and tweaks narrative elements from older musicals in interesting ways. For example, Chazelle’s film, like Demy’s Parapluies de Cherbourg, thwarts the creation of the couple. In Parapluies, the Algerian war initially separates Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) and Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve).

Later, an unplanned pregnancy and her mother’s machinations push Geneviève to marry a wealthy jeweler. At the end of the film, when they run into one another at Guy’s gas station, they exchange only a few perfunctory words; Guy even declines Geneviève’s invitation to meet their daughter. There is neither anger nor the warmth of nostalgia in their exchange; just a delicately drawn emotional distance that leaves viewers feeling wistful.

In contrast, the relationship between Mia and Sebastian fails because they decide to put their romance on hold in order to pursue their dreams. “Where are we?” Mia asks Sebastian after her audition for the film role that will take her to Paris and launch her career. “We’ll just have to wait and see,” he replies. Five years later, he owns a jazz club and she has become an A-list actress, but she is married to someone else and has a child.

When they cross paths at his club, Chazelle supplements Demy’s delicate gas station meet-up with an exuberant fantasy montage, a kind of dream ballet often used in the classical Hollywood musical, in which the couple manages to stay together. The production number is full of invention and energy, combining animation, simulated home movie footage, a trumpet solo, and a tribute to the “Broadway Melody” number of Singin’ in the Rain. As Mia prepares to leave the club, she and Sebastian exchange tender glances and rueful smiles. She departs as he launches into his next song. The love is still there, the film suggests, but Sebastian and Mia chose art over love and they would probably make the same decision today. Different from Demy’s characters, Sebastian and Mia are not victims of implacable destiny, but committed artists. It’s an ending that feels fresh to me.

As Amanda McQueen reveals below, La La Land conforms to various trends in the 21st century musical. Consider just one element: song performance. Neither Ryan Gosling nor Emma Stone possesses a powerful, belt-it-out voice. Instead, much of the singing in La La Land is modest, thin, and breathy. Take, for example, the number “The Fools Who Dream,” a climactic moment in the film.

Asked by the casting director to tell a story, Mia begins a poignant monologue (“My aunt used to live in Paris…”) in a quiet speaking voice marked by a bit of vocal fry. She slowly moves into an a capella ballad and, after a few bars, is accompanied by piano. Eventually, the music swells, Mia goes big (“Here’s to the ones who dream…”), and then the song winds back down to the concluding notes, delivered a capella. The staging of the song – black background, circular camera movement, a big swell of emotion, a long take – is reminiscent of the splashy production number in Agnès Varda’s New Wave masterpiece Cléo de 5 à 7. But Stone’s voice reminds me of the wonderfully whispery, intimate singing voices of Birkin, Bardot, and Karina.

As Eric Dienstfrey points out below, the techniques used in the recording of the songs affect our impression of the story world and our sense of the film’s aesthetic achievement. In a Song Exploder podcast about the creation of this song, composer Justin Hurwitz emphasizes the difficulty of shooting this one-shot production number. He explains that Stone performed the song live on set, as opposed to lip-synching it. Hurwitz speaks of his struggle to keep up with Stone while accompanying her on set:

Because I was letting Emma lead the song, I was reacting to her. So a lot of times the piano is a little bit behind the vocal. It sounded like a recital or something where you know the singer is leading it and the piano is there to accompany. That’s what happens when two people make music together; things are not perfectly in sync. That’s why it feels musical and why it feels real and honest.

Directors of many recent film musicals similarly seek to create the impression of aural and emotional authenticity, either through non-professional singing or on-set recording. Woody Allen’s musical Everyone Says I Love You (1996) employs actors who are not professional singers, and Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001) uses the relatively modest singing talent of Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor in a mixture of playback and live recording. Likewise, publicity for Les Misérables (2012) made much of the fact that Anne Hathaway, Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe performed their songs on the set.

Christophe Honoré also tends to employ singing performances by non-singers. Here, in Dans Paris (2006), a couple breaks up over the phone while singing in a breathy, halting fashion.

For his musical Pas son genre (aka “Not My Type,” 2014), Belgian director Lucas Belvaux cast Emilie Dequenne (of Rosetta fame) as a karaoke-singing hairdresser who woos a philosophy professor. Belvaux insisted that Dequenne avoid taking lessons so as to preserve the imperfect quality of her singing voice. Here, Jennifer (Dequenne) and her pals rehearse the Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love”:

There is, in fact, a broad spectrum of singings styles and capabilities used in contemporary film musicals. In La Captive (2000), Chantal Akerman employs an aria from Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Two women sing to one another flirtatiously from their windows across an apartment courtyard without accompaniment. One woman is a trained opera singer, while the other, the film’s elusive female protagonist (Sylvie Testud), is untutored. The contrast in the women’s voices provides an unexpected pleasure.

The use of the modest singing voice by Chazelle and others to convey emotion and authenticity is quite different, for example, from Alain Resnais’ use of song in On connaît la chanson (aka “Same Old Song,” 1997). Here, fragments of songs spanning the history of twentieth-century popular French chanson are lip-synched by actors. Like Dennis Potter, whose Singing Detective (1986) inspired On connaît la chanson, Resnais foregrounds the artificiality of dubbing. This creative choice works against the traditional commitment in film musicals (and in sound cinema more generally) to the impression of fidelity and authenticity. Here, Josephine Baker’s delicate singing voice is grafted onto the body of a Nazi commander. The humor in non-synchronization loops us right back to Singin’ in the Rain.

Directors of contemporary film musicals did not pioneer the use of the untrained singing voice. As Jeff Smith reminded me recently in an email, “There is a long tradition of celebrating the raw, unpolished singing styles of rock and rollers, dating back at least to the time of Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan and Roger Daltrey, and using those marks of authenticity as a means of distinguishing them from pop performers.” Unlike the musicians of rock and punk, though, Chazelle doesn’t seem particularly interested in denigrating pop music. He clearly loves John Legend’s musical performances in La La Land and those 1980s pop tunes he pretends to mock.

Many have criticized La La Land’s singing, but in fact, Chazelle is operating well within the tradition of employing imperfect vocalization to connote realism and to convey emotional power. The modest singing voices add another dimension to Chazelle’s participation in the ongoing conversation between Hollywood and French cinema.

La La canned vs. La La live

Eric Dienstfrey: I agree with Kelley’s observations about the remarkable number of cinematic references in La La Land. For example, the opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” embeds a host of influences within Chazelle’s mise-en-scène. For me, this exit-ramp romp immediately recalled the ferry ride in Jacques Demy’s Les Demoiselles de Rochefort and the traffic jam in Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend. Amanda McQueen, below, notes how the scene reminded her of the films of Vincente Minnelli. And as Chazelle himself indicates, one might even see traces of Rouben Mamoulian’s Love Me Tonight and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.

Thanks to such references, we can consider the significance of La La Land’s numbers as extending well beyond Justin Hurwitz’s melodies and Benj Pasek’s and Justin Paul’s rhymes. The film’s allusion to Rear Window, for instance, may encourage audiences to compare the onscreen chemistry between Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling to that of Grace Kelly and James Stewart. To catch these subtle references, filmgoers need to pay close attention to the camerawork, the staging, the costumes, and even the choreography. Similarly, we can discover new layers of meaning by analyzing its songs and their sound designs.

How many ways are there for sound technicians to record and mix a musical number? Quite a few, it seems. One basic way is to record the vocal performances live on the set. During the earliest years of talking pictures, this technique often required the presence of an on-set orchestra to provide accompaniment from behind the camera. More recent strategies, however, merely ask singers to wear small earpieces that play pre-recorded accompaniment.

Another option is for technicians to record the vocal performances in an acoustically controlled studio and then mix these recordings into the final film. Sometimes technicians will record the studio performance before filming, and then require actors to lip-synch to playback on the set. Other times, technicians will ask the singers to perform the song live on the set, but then use a studio recording in the final mix due to unforeseen circumstances.

In some instances, the set might be too noisy to record a clean vocal performance, or the dance number might be so physically demanding that the actor can’t help but introduce heavy breathing and other vocalized efforts. A live recording may be ideal, but the studio recording is often the more practical solution.

The musical numbers in La La Land display both recording techniques. Some were recorded live—such as “Fools Who Dream,” which Kelley discusses above—and some were recorded in a separate studio—such as “Another Day of Sun.” Steven Morrow, the film’s sound mixer, suggests that each choice was informed by various practical concerns. The acoustics along the exit ramp, for instance, reportedly made it too difficult to record live singing.

Such concerns even led to strange incidents where a single song would contain a mixture of both live and studio recordings. Morrow notes how “Someone in a Crowd” relies upon Emma Stone’s live recordings, while studio recordings were used for the other actresses. This decision to blend together live and studio recordings can become a storytelling device—say, if the director wants to create a contrast between two or more characters—but for most songs, the choice to use either technique is generally determined by shooting conditions and budgetary considerations.

Still, can the acoustical differences between live and studio recordings function beyond practical filmmaking needs? It is worth noting that both techniques parallel another cinematic binary: diegetic sound and non-diegetic sound. Diegetic sound commonly refers to all the dialogue, effects, and music that emanate from sources within the film’s setting, such as radios and footsteps. Non-diegetic sounds are those added to the story world as a form of commentary, such as a moody orchestral score. As many film scholars rightfully argue (here and here), the diegetic/non-diegetic binary is not perfect, but for the vast majority of films the distinction remains a useful initial categorization for sound’s narrative functions.

Musicals are an exception. In his groundbreaking study of Hollywood musicals, theorist Rick Altman argues that the clean distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound breaks down during moments when characters burst into song. Specifically, the interaction between diegetic singing and non-diegetic musical accompaniment lifts characters out of the story world toward fantastic settings. Consider Elvis Presley’s performance of “I Can’t Help Falling in Love with You” from Blue Hawaii.

Presley begins the song while accompanied by a small on-screen music box. But during his performance something interesting happens: the sound of the music box fades into the background while the drums and guitars of a non-diegetic orchestra magically appear. For Altman, this audio substitution is critical to understanding how the musical genre operates:

We have slid away from a backyard barbecue in Hawaii to a realm beyond language, beyond space, beyond time. […] We have reached a ‘place’ of transcendence where time stands still, where contingent concerns are stripped away to reveal the essence of things.” (66)

In other words, this dissolve from the music box to the orchestra tells us that Elvis… well… has left the building. He has transcended the purely diegetic universe of the film’s story-world reality, and has temporarily entered a non-existent space that is supra-diegetic fantasy.

Altman’s observations apply to La La Land as much as they apply to Blue Hawaii. When Mia and Sebastian sing “A Lovely Night” while searching for their cars, the non-diegetic accompaniment fades in and the two characters interact with the music through song and dance. In turn, Mia and Sebastian transcend Los Angeles and enter a supra-diegetic universe. This diegetic boundary crossing is punctuated further by their stroll through Hollywood’s hills, a vantage point which allows Mia and Sebastian to literally look down upon the city as they chart this transcendence.

Yet La La Land is more than just a pastiche of earlier musical traditions. It also demonstrates how different recording techniques can be thematically integrated within the film’s narration. Here we might once again compare the playback of “Another Day of Sun” to the live recording of “Fools Who Dream.” Both numbers are similar in their reliance upon non-diegetic musical accompaniment, yet the production process creates contrasting narrative implications.

“Another Day of Sun” was recorded in a studio, and the acoustical details of this studio environment—namely frequency response, microphone placement, reverberation time, and overall cleanliness of the recording—are remarkably distinct from the those of an outdoor location. These subtle textural differences produce the sense that the performers’ voices have left the diegetic space of the freeway and traveled to an unseen studio for the song’s duration.

“Fools Who Dream” has the opposite effect. It was recorded live, and throughout the scene the acoustical details that shape Stone’s voice never really change. The sonic signature of the room remains audible in her vocals from the time she introduces herself to the casting directors, to the time she finishes singing. As a result, Mia does not transcend the story world; instead, the non-diegetic piano and orchestra seem to materialize inside the room.

These two examples demonstrate how alternative recording techniques offer filmmakers different ways for characters and accompaniment to interact. Studio recordings specifically lift the vocals up toward the space of the non-diegetic accompaniment, whereas live performances can pull traditional musical accompaniment down into the story world. Both techniques defy the norms of realism, yet their production differences render each vocal performance with unique narrative weight. And for La La Land—a musical about two artists who wish to become famous stars while simultaneously remaining pragmatic and down-to-earth—the ways Mia and Sebastian interact with musical accompaniment can reveal if and when the characters are grounded in reality or lost in fantasy.

As criticism surrounding contemporary musicals would suggest, Hollywood routinely favors live performances over other techniques. Live performances are not only valued for being more authentic, they are harder to record and, thus, a more prestigious cinematic accomplishment. This preference for live recordings, however, need not dictate how all musicals are made. A creative integration of both live and studio recordings can open up storytelling possibilities for the sound technicians and directors who wish to innovate within the musical genre.

Yes, I know: it seems unlikely that many filmmakers will play with these acoustical parameters in their movies. Nonetheless, La La Land’s sound design points to the possibility that at least a few musicals will create rewarding experiences not just for visually minded historians, but for audiophiles as well.

A musical without quotation marks

Amanda McQueen: Much of La La Land’s critical reception has focused on its relationship to film musicals of the past. As Kelley, Eric and David have all noted, much of the film’s meaning derives from its citation and revision of film and stage musical traditions. But what’s the status of La La Land as a musical in the 21st century? How does this shape the film’s approach to the genre’s conventions?

The early 2000s witnessed a minor revival of the Hollywood live-action musical, a genre that had been considered box office poison for several decades. But despite the renewed interest in musicals, producers worried that contemporary audiences no longer accepted one of its key conventions: the integrated number.

Integration commonly refers to those moments when characters spontaneously burst into song to express feelings or advance the plot, usually accompanied by sourceless music, as Eric points out above. Not all musicals have integrated numbers, but many critics and scholars assume that integrated musicals constitute the genre’s core. Audiences, however, were assumed to find this particular break with cinematic realism both antiquated and alienating. Moviegoers would suspend disbelief to accept lightsabers, superheroes, and wizards, but someone walking down the street and singing—no way!

Fear of the integrated number has caused many contemporary musical films and television shows to distance themselves from this convention. Some musicals ensure the song-and-dance numbers are otherwise motivated. In Chicago and Nine (2010), all the songs are figments of the characters’ imaginations, while Dreamgirls (2006) transformed the integrated numbers of the Broadway original into diegetic stage performances.

Other musicals, including Enchanted (2007), The Muppets (2011), Annie (2014), and Pitch Perfect 2 (2015) opt for comic reflexivity, using integrated numbers to comment on their very artifice. The campy medieval musical Galavant (ABC 2015-2016) is perhaps the epitome of this technique. The lyrics of the second season’s opening number, for instance, address the series’ unexpected renewal (“Give into the miracle that no one thought we’d get”); the excessive repetition of the theme song in the previous season (“It’s a new season so we won’t be reprising that tune”); and a perceived lack of motivation for musical performance (“There’s still no reason why we bust into song”). The four-minute ensemble song-and-dance concludes with Galavant (Joshua Sasse) commenting with satisfaction, “See, now that was a number!”

Over the years, concern over audience acceptance of the integrated musical seems to have abated, particularly for Broadway adaptations. But it hasn’t disappeared, as La La Land’s critical reception makes evident. Articles on the film have routinely stressed that musicals are “an extinct genre,” that “some moviegoers may, no doubt, feel a little tentative about the genre,” and that musicals are no guarantee at the box office. Manohla Dargis’ review in The New York Times, aptly titled “‘La La Land’ Makes Musicals Matter Again,” discusses this issue at some length. She explains how “For decades, the genre that helped Hollywood’s golden age glitter has sputtered,” reappearing only in Broadway adaptations or diluted (read, non-integrated) forms, and that as a result, “Musicals have been for kids, for knowing winks and nostalgia.”

What perhaps feels so novel about La La Land is its sincere approach to the “old fashioned” integrated musical form. As writer/director Damien Chazelle told Hollywood Reporter:

On the screen, there is this big gap right now that you have to cross to do a musical. At least an earnest musical, where you’re not immediately putting quotation marks on it.

With its opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” La La Land unabashedly announces that this is an integrated musical, and it never qualifies that position. There are no cheeky winks at the camera, no characters asking why they’re singing to each other, and most of the songs function as pure expressions of thoughts and feelings. Mia and Sebastian are real people in a modern city, who just happen to be singing and dancing and falling in love. For Chazelle, “Another Day of Sun” functions as “a warning sign to people in the audience. If people are not going to be comfortable with it, they’ll leave right away.” La La Land thus almost dares audiences to accept and celebrate this unrealistic cinematic convention, and for a 21st century musical, that’s a somewhat rare approach to take.

Yet La La Land has its own methods of rendering the integrated musical acceptable for contemporary audiences. First, there is its obvious nostalgia. La La Land’s visual style—35mm, CinemaScope, long takes and long-shots scaled to choreography—and its many allusions create a critical distance, an awareness that this type of cinema is a relic of another age. It’s not so much a throwback to studio-era musicals as it is a modern version of the auteurist musicals of 1970s New Hollywood (most of which were also resistant to the traditional integrated number). Indeed, La La Land has been compared to Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977) or Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart (1981).

I think it’s also akin to Ken Russell’s The Boy Friend (1971), which has a lighter tone and takes a similar approach to its citations. Russell updates Busby Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic stagings with color and widescreen, and Chazelle updates Vincente Minnelli’s sequence-shots with a Steadicam. Like The Artist (2011), which tutored modern viewers in the conventions of silent cinema, La La Land is an affectionate lesson in a mode of filmmaking that is not likely to return.

Then there’s the ending, in which Mia and Sebastian find success in their artistic pursuits, but only because they have parted romantically. As Kelley explains, La La Land owes its bittersweet ending to Jacques Demy’s Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). This gives the film a melancholy at odds with the studio era Hollywood musicals it so frequently references—films like An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952), in which the couple lives happily ever after. By eschewing the union of its romantic couple, La La Land tempers the artifice of the integrated musical with a more realistic narrative, one that acknowledges that life does not always work out exactly the way we want. Such a conclusion is far more typical of American independent cinema than it is of the classical Hollywood musical.

Significantly, La La Land does give us a traditional happy ending, but through the device of the dream ballet. One of the most overtly stylized conventions of stage and screen musicals, dream ballets generally function to convey character subjectivity, and they allow for especially abstract mise-en-scène. La La Land tackles this generic trope with the same sincerity it displays in its handling of integrated numbers.

Set to a medley of the film’s musical themes, the sequence functions much like that in An American in Paris, arguably the most famous cinematic dream ballet. The sequence recaps the characters’ emotional journey and romantic relationship entirely through dance. Yet while the ballet in Paris shows a stylized version of what has actually occurred, La La Land’s presents an alternative reality where Sebastian and Mia stay together while also achieving their artistic goals. As Owen Gleiberman puts it in Variety, this “the very movie we would have been watching had ‘La La Land’ simply been the delectable old-fashioned musical we think, for an hour or so, it is.” In the end, though, the film affirms that Mia and Sebastian’s happily-ever-after is only a fantasy; when the dream ballet ends, the two part ways.

The first time I saw La La Land, I found myself daring Chazelle to subvert my expectations and use the dream ballet as a device to create a happy ending. Instead of concluding the fantasy sequence with a return to reality, I hoped the dream ballet would function to re-write the narrative. To my mind, turning the imagined world of the dream ballet into the characters’ actuality would have been an interesting twist on how this device usually functions. At the same time, it would have more radically embraced the integrated musical tropes the film otherwise celebrates.

Yet I suspect viewers would have found this ending contrived, and it would have been. La La Land’s critical and commercial success, I think, has depended on it keeping the model of the classical Hollywood integrated musical slightly at arm’s length. The film’s unique combination of nostalgia and realism is clearly resonating with modern audiences, but it’s also in keeping with the larger approach to the integrated musical in the contemporary moment. As long as film musicals are considered risky properties, certain forms of the genre will likely have to be relegated firmly to the past.

Kelley Conway is a Professor in our department and winner of a Distinguished Teaching Award. She has written Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in 1930s French Film (University of California Press), Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press), and essays on classical and contemporary French film. She is currently at work on a book about postwar French film culture.

Eric Dienstfrey is a doctoral candidate in our department. His dissertation traces how theories of acoustical fidelity shaped stereophonic technology from 1930 to 1959. Eric’s research interests include silent film musicians and the cultural history of dictaphones. He recently received the 2017 Katherine Singer Kovács Essay Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

Amanda McQueen, a Faculty Assistant in our department, finished her Ph.D. in 2016. Her dissertation is titled “After ‘The Golden Age’: An Industrial History of the Hollywood Musical, 1955-1975.” It examines how the breakup of the studio system helped create several musical cycles, each aimed at a niche audience, and each designed to prolong the genre’s viability in the new marketplace. Apart from studying musicals on stage, screen, and TV, Amanda’s interested in media industries, film technologies, and genre theory and history.

Thanks as well to Jeff Smith for his comments on these entries. Watch for his annual blog entry (first two, here and here) analyzing the Oscar-nominated songs and scores.

La La Land.

Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT

DB here: Here’s another guest contribution from colleague, Film Art collaborator, and pal Jeff Smith. He inaugurates a series of entries tied to our monthly Observations on Film Art videos on FilmStruck.

About a month ago, a new streaming service for film lovers debuted. Its name is FilmStruck and it’s a joint venture of Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Collection.

As regular readers of the blog already know, David, Kristin, and I have launched a series for FilmStruck. Every month, we’ll be featured in short videos that offer appreciations of particular films and filmmakers. In baseball lingo, I got the leadoff spot. As the first up, I offered an overview of the principal musical motifs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Below is a supplement to the video that goes into a little more depth regarding the way Alfred Newman’s score for Foreign Correspondent fits into the film’s larger narrative strategies.

Fair warning: there are some spoilers in what follows. Some of you who are FilmStruck subscribers or owners of the Criterion disc may want to watch this Hitchcock classic before proceeding.

Founding a Hollywood dynasty

Alfred Newman.

If you were looking for someone whose work epitomized the qualities of the classical Hollywood score, Alfred Newman would be a pretty good candidate for the job.

Newman’s career in Hollywood began when Tin Pan Alley stalwart, Irving Berlin, recommended him for the 1930 musical, Reaching for the Moon. Having worked for years as a music director on Broadway, Newman planned to stay for only three months. But the lure of the Silver Screen was too strong. Newman spent the next forty years working in Hollywood.

In 1931, Newman became the musical director at United Artists, working mostly for producer Samuel Goldwyn. He also established himself as one of the industry’s leading composers, contributing to nearly ninety films over the course of the 1930s and earning nine Oscar nominations in the process. Newman’s most memorable early scores included such titles as The Prisoner of Zenda, The Hurricane, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Wuthering Heights. Eventually, he would leave Goldwyn to take over the music department at 20th Century-Fox, a position he held for more than twenty years.

Alfred, however, would be just one of several Newmans who would make the name synonymous with the Hollywood sound. Alfred would establish a film composing dynasty that would come to include his brothers Lionel and Emil; his sons, Thomas and David; and his nephew, Randy.

Overture, hit the lights….

If you asked most film music aficionados for their favorite Alfred Newman scores, I suspect Foreign Correspondent would be pretty low on the list. Most fans of the composer’s work would likely opt for one of the later Fox classics he scored, such as How Green Was My Valley (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Captain from Castile (1947), or The Robe (1953). Yet, if you want to get a handle on the basic features of the classical paradigm, Foreign Correspondent’s typicality makes it more useful as an exemplar. Newman’s music neatly illustrates several of the traits commonly associated with the classical Hollywood score’s dramatic functions.

One of these characteristic traits is Newman’s use of leitmotif as an organizational principle. Foreign Correspondent’s score is organized around five in all. The first is a theme for the film’s protagonist, Johnny Jones. The second is a theme for Carol, Johnny’s love interest in the film. As is typical of studio-era scores, both themes are introduced in the film’s Main Title.

Like an overture, the Main Title previews the two most important musical themes in the film. The A theme is upbeat, sprightly, and lightly comic. It captures some of Johnny’s ebullience and masculine charm, and it helps establish the tone of the early scenes, which draw upon the conventions of the newspaper film. The B theme is slower and more lyrical. It features the kind of lush orchestrations for strings that became a hallmark of Newman’s style.

Each theme roughly correlates with the dual plot structure common to classical Hollywood narratives. The A theme previews the main plotline focused on Johnny’s efforts as an investigative reporter. The B theme previews the story’s secondary plotline: the budding romance between Johnny and Carol.

Both themes recur throughout the remainder of the movie. In fact, Johnny’s theme returns even before the opening credits have ended, appearing underneath a title card valorizing the power of the press. In contrast to the lively, spunky version heard earlier, Newman gives it a maestoso treatment, slowing the tempo and orchestrating it for brass. In this instance, Newman’s arrangement of Johnny’s theme is attuned less to the brashness of his character and more to the social role that newspaper reporters play as a source of information to the world.

Up until this point, the music simply primes us for what is to come. Johnny’s theme returns about two minutes later when he is first introduced.

The reprise of his theme makes explicit the Main Title’s tacit association between music and character. Here, though, it plays in a jazz arrangement as a slow foxtrot. Newman’s arrangement nicely captures the tone of these early scenes, which display the lightness and pacing of other newspaper comedies.

It returns 22 more times in the film. In all, Johnny’s theme accounts for more than a quarter of the film’s 94 music cues. Usually, the theme functions to underline Johnny’s heroism and resourcefulness as in the scene where he gives chase to Van Meer’s assassin. At one point, Johnny even whistles his theme. This occurs in the scene where he eludes a pair of suspicious men posing as police by pretending to draw a bath and crawling out the window.

In contrast, Carol’s theme is used less frequently, appearing in about thirteen cues in all. After its introduction in the main title, it returns when Johnny and Carol first meet at the luncheon sponsored by the Universal Peace Party. Johnny unknowingly insults Carol, first by mistaking her for a publicist, and then by expressing skepticism about the organization’s mission, griping about well-meaning amateurs interfering in international affairs. Newman’s theme hints at Carol’s attraction to Johnny despite his obvious boorishness. The music says what the characters can’t or won’t say. As Johnny and Carol trade insults, Carol’s theme captures the romantic spark that lurks beneath their badinage.

The theme’s other uses often work along similar lines, providing an emotional resonance to the couple’s expression of feelings for one another. A good example is found in the scene where Carol and Johnny huddle together on the deck of a steamship. Here, as a pair of refugees, each member of the couple declare their love for one another and their desire to marry.

Music for the hope of the world

In addition to these two principal themes, the score also utilizes three other themes and motifs to represent important secondary characters. A theme for Professor Van Meer is introduced when Johnny spots him getting into a taxicab.

It returns nine more times in the film in scenes that feature the character or make reference to him.

The theme itself is simple, slow, stately, and quite frankly, a little bit boring. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the multiple references to a “Van Meer Theme” on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent, the music would simply blend into the other material that surrounds it.

The orchestration of the theme for solo wind instruments, usually an oboe, gives it a kind of pastoral feeling. The image of peaceful shepherds is likely an appropriate one for Van Meer, who functions as a stand-in for a global desire to avoid armed conflict. Yet, both the character and Newman’s musical theme for him seem nondescript, making Van Meer seem like little more than the walking embodiment of an abstract ideal of world harmony.

Truth be told, Van Meer mostly operates in Foreign Correspondent as the classic Hitchcock MacGuffin–that is, the thing the characters all want, but with which the audience need not concern itself. When Van Meer appears to be assassinated, it sets in motion a chain of events that uncovers a conspiracy organized through Steven Fisher’s World Peace Party. Van Meer is the object that all the characters want to find, and the search for him drives the narrative forward. Yet the character himself has about as much personality as the microfilm in North by Northwest. Newman’s nondescript melody seems to fit the “blank slate” quality of Van Meer himself.

Like the classic MacGuffin, Van Meer’s function as something of an empty vessel allows his theme to be used several times late in the film in scenes where the character isn’t physically present. Although the norm is to use characters’ themes or leitmotifs when they are onscreen, Newman’s treatment of Van Meer shows they can evoke absent characters. This occurs, for example, in a scene where Scott ffolliot explains to Stephen Fisher that he’s arranged for the kidnapping of Carol. Fisher asks ffolliot why he would do such a thing, and ffolliot replies that he wants to know where Stephen has stashed Van Meer.

As we’ll see, Fisher has a theme of his own that itself appears several times in this same scene. But the use of Van Meer’s theme in this context becomes a way of signifying both the character and the peaceful values that he represents – that is, values that Fisher seeks to destroy.

And though Van Meer’s music is a bit dull, the theme proves a bit more interesting when one considers the way it works within Hitchcock’s larger strategies of narration. At a key point, Hitchcock and Newman use the Van Meer theme to mislead the audience about what has just transpired onscreen. I’m referring here to the moment when Van Meer appears on the steps just as the Peace conference in Amsterdam is about to commence.

The theme is cued by Johnny’s glance offscreen after briefly chatting with Fisher, his publicist, and a diplomat. Hitchcock cuts to a shot from Johnny’s optical POV that shows Van Meer climbing up the staircase. We return to Johnny, who smiles and walks out of the frame. Johnny and Van Meer meet in a two-shot where the former offers a warm greeting. A cut to Van Meer’s reaction, though, reveals a blank stare, even as Johnny tries to remind the elderly professor of their previous encounter in the taxi.

The moment is an important one, but before the viewer can even grasp its significance, the two men are interrupted by a request for a photograph. Hitchcock then tracks in on the newsman, who surreptitiously sneaks a gun next to the camera he is holding. He pulls the trigger, and Hitchcock cuts to a brief insert of Van Meer, who has been shot in the face.

As I noted earlier, the assassination we witness is a key turning point in the story, and Hitchcock handles the scene with considerable finesse. Almost unnoticed, though, is the fact that Hitchcock and Newman cleverly use Van Meer’s musical theme as a form of narrative deceit. At first blush, the musical theme helps to reinforce Van Meer’s identity, serving the kind of signposting function that some film music critics believed was a hackneyed device. As we later learn, though, the murder victim is not Van Meer, but rather a double killed in his place to foment international tensions. This information ultimately recasts the old man’s seeming failure to recognize Johnny. As Van Meer’s double, these two men have never actually met.

Has Hitchcock played fair in using Van Meer’s theme for a character that is not Van Meer but only looks like him? Perhaps, but the creation of this red herring is justified if one considers the fact that composers frequently write cues meant to reflect or convey a character’s point of view. Every composer must make a choice about whether to write a cue from the particular perspective of the character or the more global perspective of the film’s narration. Newman might have opted for conventional musical devices that connote suspense (ostinato figures, string tremolos, low sustained minor chords), and these would have signaled to the viewer that Van Meer is in peril, thereby creating a heightened anticipation of the violence that erupts in the scene. Instead, though, following the visual cues provided by Hitchcock’s cinematography and editing of the scene, Newman plays Johnny’s perspective and his recognition of Van Meer as he approaches the building’s entrance. By combining two common tactics–leitmotif and character perspective – Newman and Hitchcock briefly mislead the audience in order to create two surprises: the first when it appears that Van Meer is killed and the second when Van Meer is discovered inside the windmill and proves to be very much alive.

Menace (without the Dennis)

There is also a brief six-note motif used to signify the conspirators as a group. Labeled the “menace” motif, it is introduced just after Van Meer’s apparent assassination. In the chase that follows, Newman alternates between the “menace” motif and Johnny’s theme in order to sharpen the conflict and to capture the ebbs and flows of our hero’s dogged pursuit of the bad guys.

The motif returns, though, at just about any point where one of the group’s henchmen gets up to no good. In the scene inside the windmill, the menace motif appears several times to underscore the kidnappers’ nefarious scheme. Johnny sneaks inside the windmill, and after locating Van Meer, he tries to rescue him only to find out that the elderly professor has been drugged. As Johnny tries to figure out his next move, muted trumpets play the “menace” motif, signaling the kidnappers’ approach and thereby heightening the scene’s suspenseful tone.

Here again, Newman’s thematic organization reinforces a larger narrative tactic in Hitchcock’s film. Herbert Marshall serves as the typical suave villain commonly found in the Master’s oeuvre and Edmund Gwenn steals the show as Johnny’s would-be assassin, Rowley. But the rest of the conspirators are a largely undistinguished lot, and the use of a single motif for the group in toto reflects their relative impersonality. Unlike North by Northwest, where Martin Landau makes a vivid impression as Van Damm’s reptilian assistant Leonard, this spy ring seems to be filled out by thugs from Central Casting.

Father, leader, traitor, spy

Besides motifs for Johnny, Carol, Van Meer and the conspirators, there is also a short motif for Carol’s father, Stephen Fisher. It is harmonically and melodically ambiguous, structured around the rapid, downward movement of a chromatic figure.

In classical Hollywood practice, a leitmotif is usually introduced when the character first appears onscreen. But in an unusual gesture, Newman and Hitchcock resist this convention. The motif does not appear until more than eighty minutes into the film in the aforementioned scene just before ffolliot tries to blackmail Fisher into divulging Van Meer’s location.

By withholding Fisher’s motif, Hitchcock and Newman avoid tipping their hand too early. Since Fisher is later revealed to be the leader of the spy ring, the score circumspectly avoids comment on him in order to preserve the plot twist.

Several cues featuring Fisher’s motif return in the scene where Johnny, Carol, ffolliot, and the other survivors of the plane crash cling to wreckage waiting to be rescued. Carol spots the plane’s pilot stranded on its tail.

He swims over to the group and clambers about the wing. The pilot’s added weight threatens to upend the wing, thereby endangering everyone sitting atop it.

Recognizing this, the pilot asks the others to let him go so that he can simply “slip away.” Fisher overhears this exchange and decides to remove his life jacket and dive into the waters himself, leaving room on the plane’s wing for the rest of crash’s survivors.

The harmonic and melodic ambiguity of Fisher’s motif is most pronounced here, a moment where the character’s duality is also most clearly revealed. Is this a heroic act of self-sacrifice, an act of atonement for the damage Fisher has done to both his daughter’s reputation and his organization’s peaceful cause? Or has Fisher taken the coward’s way out, committing suicide in order to avoid facing the consequences of his actions?

Newman’s rather opaque musical motif doesn’t seem to take sides on this question, leaving Fisher’s motivation more or less uncertain. But this, too, is in keeping with the basic split between the character’s public and private personae. Introduced earlier as Carol’s father, Fisher appears to be cultured and debonair. Yet, when he seeks to extract information from a reluctant captive, Stephen resorts to the physical torments used by two-bit gangsters to make mugs talk. Like those gangsters in the 1930s, Fisher refuses to be taken alive and is swallowed up in briny sea. Still, his action does help to save other lives, and in this way, Fisher enables Carol to find a small measure of grace in the final memory she will have of him.

Putting earworms inside actual ears

As the principal composer of music for Foreign Correspondent, Newman had a major impact on the film’s ultimate success. Yet Newman was not responsible for the music that has engendered the most attention in critical work on the film. I’m referring here to two source cues written by Fox staff arranger, Gene Rose, that are featured in the scene where Van Meer is psychologically tortured. His captors use sleep deprivation techniques to elicit van Meer’s cooperation, including bright lights and the repeated playing of a jazz record. The two cues received rather cheeky descriptions on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent: “More Torture in C” and “Torture in A Flat.”

The use of jazz for these cues is likely a little bit of wicked humor on Hitchcock’s part. Despite its popularity as dance music in the 1930s, some listeners undoubtedly believed that jazz was little more than noise with a swinging rhythm. From a modern perspective, though, the scene eerily anticipates the “enhanced interrogation” techniques that would become notorious at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib. As The Guardian reported in 2008, US military played Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” at ear-splitting volume for hours on end, both at Guantanamo and at a detention center located on the Iraqi-Syrian border. At the other end of the musical spectrum, one of the other pieces played repeatedly was “I Love You” sung by Barney the purple dinosaur. Presumably the first was selected because of its aggressiveness, the latter because of its insipidness. But the Barney song has the distinction of being characterized by military officials as “futility” music – that is, its use is designed to convince the prisoner of the futility of their resistance.

Although, in 1940, Hitchcock could not have envisioned the use of heavy metal and kidvid music as elements of enhanced interrogation, the scene from Foreign Correspondent is eerily prescient. Viewed today, the scene also carries with it a strong element of political critique insofar as it associates such psychological torture techniques with a bunch of “fifth columnists” who are willing to commit murder and even engineer a plane crash in order to achieve their political ends. Touches like these make Foreign Correspondent seem timely today, more than seventy-five years after its initial release.

Alfred Newman the Elder

After Foreign Correspondent, Alfred Newman would go on to score more than a hundred and thirty feature films, and earn several dozen more Academy Award nominations. His nine Oscar wins remain an achievement unmatched by any other film composer. Newman died in Hollywood in 1970 at the age of 69, just before the release of his last picture, the seminal disaster movie, Airport. His work on Airport received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, the 43rd such nomination of his long and distinguished career.

For some film music scholars, Newman’s death marked the end of an era, as his career was more or less contemporaneous with the history of recorded synchronized sound cinema in Hollywood. As fellow composer Fred Steiner wrote in his pioneering dissertation on the development of Newman’s style:

As things are, we can be grateful for the dozen or so acknowledged monuments of this twentieth-century form of musical art— absolute models of their kind— that Newman did bestow on the world of cinema. Fashions in movies and in movie music may come and go, but scores such as The Prisoner of Zenda, Wuthering Heights, The Song of Bernadette, Captain From Castile, and The Robe are musical treasures for all time, and as long as people continue to be drawn to the magic of the silver screen, Alfred Newman*s music will continue to move their emotions, just as he always wished.

Because of its typicality, Foreign Correspondent may well seem like a speed bump on Newman’s road to Hollywood immortality. Yet it remains a useful introduction to the composer himself, who along with Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, is part of a triumvirate that would come to define the sound of American film music.

For more on music in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, see Jack Sullivan’s encyclopedic Hitchcock’s Music. For more on the production of Foreign Correspondent, see Matthew Bernstein’s Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. Readers interested in learning about Alfred Newman’s career should consult Fred Steiner’s 1981 doctoral dissertation, “The Making of an American Film Composer: A Study of Alfred Newman’s Music in the First Decade of the Sound Era,” and Christopher Palmer’s The Composer in Hollywood.

Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music includes Newman’s own account of his work for the Broadway stage before coming to Hollywood. Readers interested in an overview of the classical Hollywood score’s development should consult James Wierzbicki’s excellent Film Music: A History.

Alfred Newman conducts his most famous film theme, Street Scene, in the prologue to How to Marry a Millionaire (1953).

Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations

The Hateful Eight (2015).

DB here: Jeff Smith, our collaborator on the new edition of Film Art, is an expert on film sound. He has written earlier entries on Atmos and Trumbo.

The Academy Awards ceremony is upon us. Once again this year, I offer an overview of the two music categories: Best Original Song and Best Original Score. For the songs and some score cues I’ve provided links, so you can listen as you read.

This year’s nominees showcase music written in an array of musical styles for a wide range of narrative contexts. The composers and songwriters recognized for their work include some newcomers, some savvy veterans, and a pair of legends who have helped to define the modern film score.

As always, this preview is offered for non-sporting purposes. Anyone seeking insights for wagers or even the office Oscar pool is duly cautioned that they assume their own financial risks for any information they use. And since I was only half-right with last year’s prognostications, you might seek predictions from insiders at Variety and Entertainment Weekly.

Diversity in numbers: Best Original Song

Fifty Shades of Grey (2015).

When the Oscars were announced a few weeks ago, they made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Noting the lack of racial diversity among the acting nominees, social media exploded, creating #OscarsSoWhite as a popular Twitter handle to draw attention to the situation. After a cacophony of tweets and retweets, several celebrities weighed in. Will Smith and others suggested that they planned to boycott the ceremonies.

The nominees for Best Original Song, though, are a pretty significant exception to the OscarsSoWhite meme. Both the performers of these five songs and the topics they address reveal that Oscar voters haven’t entirely ignored the fact that films can be a force for social change.

The Weeknd’s breakout year on the pop charts has continued with an Oscar nomination for “Earned It” from Universal’s hit of last spring, Fifty Shades of Grey. The Weeknd’s “Can’t Feel My Face” has enlivened playlists all year long, but “Earned It” is a slow-burn soul ballad that accompanies Christian and Anastasia’s ride home after his mother interrupts their morning tryst. The song was co-written by the Weeknd, Belly, Jason “Daheala” Quenneville, and Stephan Moccio, and features a simple two-chord pattern on the piano that eventually builds toward a more harmonically adventurous string passage. According to Moccio, the song was intended to reflect a male perspective, hinting at the darkness lurking underneath Christian’s sexual peccadillos.

The Weeknd, Quenneville, and Belly are all Canadian. But considering that the Weeknd and Quenneville are of African descent and that Belly is of Palestinian heritage, their nomination offers a modest riposte to the criticism leveled at the Oscars for their lack of racial diversity. However, since their song appears in one of the more critically reviled films to receive a nomination, it seems unlikely that “Earned It” will take home the prize next Sunday.

Tuning up nonfiction films: Nominated songs from docs

Racing Extinction (2015).

Two other nominations come from recent documentary films, continuing a trend begun with last year’s nod to Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me. The first is for J. Ralph and Antony Hegarty’s “Manta Ray” from Racing Extinction, which examines the threat man poses to the survival of several bird species, amphibians, and marine animals.

Hegarty is only the second openly transgender person to receive a nomination, a quite pleasant surprise for fans of her work as a singer and songwriter. Hegarty initially made a splash in 2000 with the release of her band’s debut album, Antony and the Johnsons. Her breakthrough, though, came with the 2005 release I Am a Bird Now, which topped several critics’ year-end lists and won Britain’s prestigious Mercury Prize.

“Manta Ray” is a delicate waltz based upon a central theme from J. Ralph’s score for Racing Extinction. Although the song itself appears only over the closing credits, Ralph’s theme threads through the film, introduced during a key scene when a member of the filmmaking team removes a hook and fishing line from a manta ray’s dorsal fin. After the SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, commercial fishermen increasingly targeted manta rays since their gills were thought to have curative powers among practitioners of Chinese folk medicine.

Anchored by her soft, tremulous voice, Hegarty’s music has always exuded sensitivity and melancholy in almost equal measure. With Hegarty’s ethereal tones floating over Ralph’s simple piano accompaniment, “Manta Ray” not only captures the animal’s grace and beauty, but also hints at the tragedy of their steady decline.

Racing Extinction is not Hegarty’s first brush with Hollywood. Previously, her music was featured in James McTeigue’s V for Vendetta and in Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There. But given all the media attention to the Oscars, Sunday night will offer Hegarty a much bigger stage and a chance for the world to see her extraordinary gifts.

The other nominated song from a documentary is “Til It Happens to You,” which was written for Kirby Dick’s searing documentary on campus rape, The Hunting Ground. The film not only exposes college administrators’ efforts to cover up incidents of sexual assault, but also shows how two University of North Carolina rape survivors used Title IX legislation to draw attention to the problem.

“Til It Happens to You” brought Lady Gaga her first nomination and Diane Warren her eighth. Beyond the sheer star power brought by the pair, Gaga and Warren both have discussed their own experience as rape victims.

According to Variety, Gaga worried that the gravity of the film’s subject matter might not square with her outlandish diva persona: “I was very concerned that people would not take me seriously or that I would somehow add a stigma to it.” But her concerns appear to be unfounded. Warren reports that other survivors have reached out to her saying that the song and film is “making people feel less alone.”

Some of this reaction undoubtedly derives from the emotional gut punch delivered by the song’s lyrics. They not only describe the feelings of devastation felt by rape victims. They also express the difficulty of dealing with unfeeling bureaucrats and callous peers. The refrain of “Til It Happens to You” conveys the sense of isolation created by others’ inability to fully know what it’s like to walk in the victim’s shoes.

Licensed to Trill: The Spectre of Youth

Spectre (2015).

Jimmy Napes and Sam Smith’s “Writing’s On the Wall” from Spectre adds another notch to James Bond’s gunbelt. Four previous Bond films have received nominations for Best Original Song. And in 2013, British chanteuse Adele took home a golden statuette for the title track of Skyfall.

For me, the piece is well crafted, but falls somewhere in the middle of the Bond music pantheon. Not quite the peaks of Shirley Bassey’s “Goldfinger” or Paul McCartney’s “Live and Let Die.” But also not the dregs of Rita Coolidge’s “All-Time High” or A-ha’s “The Living Daylights.” “Writing’s On the Wall” is vaguely Bond-ish in much the same way that Smith’s smash hit, “Stay With Me,” contained strong echoes of Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down.”

The last nominee is “Simple Song #3” from Youth. Of all the nominees, David Lang’s piece is the one most firmly integrated into the film’s narrative. “Simple Song #3” is featured at the end of Youth, performed onscreen by singer Sumi Jo, violinist Viktoria Mullova, and the BBC Concert Orchestra.

The song is a classic “Adagio” structured around a repeated descending string figure. Gradually, other instruments are added, creating patterns of shifting harmony that surge beneath Jo’s vocal line.

Although “Simple Song #3” doesn’t appear till the end, the song is mentioned at several earlier moments as the work of the film’s protagonist, Fred Ballinger (Michael Caine). Ballinger is a retired composer and conductor lured back to the stage by an invitation from the Queen to perform for Prince Philip’s birthday. According to Lang, the piece offers a window into Ballinger’s psychology. It balances both the aspirations of his youth with the melancholy of a life lived apart from the woman he loved.

Placed in the film’s climax, Ballinger’s work provides an emotional capstone that operates at several levels. Given the complexity of its narrative function, “Simple Song #3” is not so simple.

Prediction: As a longtime Antony and the Johnsons fan, I would be delighted to see Hegarty and Ralph making their acceptance speech on Sunday night. But it seems to be Lady Gaga’s year so far. After winning a Golden Globe for her work on American Horror Story: Hotel, singing the national anthem at the Super Bowl, and performing a tribute to David Bowie at the Grammys, Gaga will cap off a stellar start to the new year by walking home with Oscar on her arm. It will also provide career recognition to Diane Warren, whose music has graced more than 200 different films and television shows. After last year’s disappointment, Warren finally will get the opportunity to be forever “Grateful.”

Old White Men and Even Older White Men: Best Original Score

Sicario (2015).

The nominees for Best Original Score are a group of seasoned craftsmen who collectively have received more than seventy Oscar nominations and have written music for more than seven hundred feature films. At age 46, Jóhann Jóhannsson is the youngster of the group. Carter Burwell and Thomas Newman both turned sixty late last year. And John Williams and Ennio Morricone are both octogenarians.

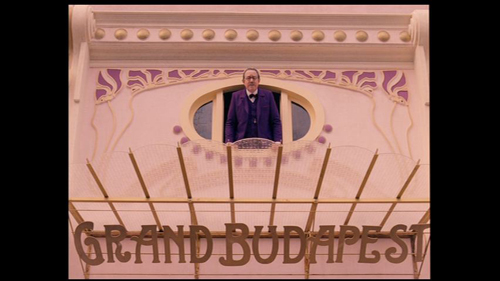

Jóhannsson is nominated for his score for Denis Villeneuve’s drug war thriller Sicario. The Icelandic composer received a nod last year for The Theory of Everying, but lost out to Alexandre Desplat’s charming Euro-pudding score for The Grand Budapest Hotel.

The score for Sicario, though, couldn’t be more different than that for The Theory of Everything. Where Everything’s music was lilting and lyrical, Sicario’s is tense and ominous, emphasizing rhythm, timbre, and texture over more conventional structures of melody and harmony. Several cues are organized around pounding drum patterns punctuated by sustained, dissonant blasts of strings and low brass. In an interview, Jóhannsson recalled, “I think the the percussion came first, and then I started to weave the orchestra into it. Very early on I decided to focus on the low end of the spectrum—focus on basses, contrabasses, low woodwinds, contrabassoon, contrabass clarinets and contrabass saxophone.”

Other cues also emphasize percussive textures, but with the instrument sounds processed so that they sound driven to the point of distortion. Even a more restrained cue like “Melancholia” still maintains a quiet intensity, structured around a cyclic harmonic pattern played on acoustic guitar in a vaguely flamenco style. The score is brutally effective in capturing the mood of Sicario’s taut action scenes. In fact, for me, Jóhannsson’s score was, without question, the best thing in the film.

The Old Hands: Carter Burwell and Thomas Newman

Carol (2015).

Carter Burwell received his first Oscar nomination this January for his score for Todd Haynes’ Carol. Burwell got his start on the Coen brothers’ debut, Blood Simple (1984), and has been a regular collaborator ever since. He has also worked regularly with a number of other filmmakers, such as Charlie Kaufman, Spike Jonze, and Bill Condon. Given the rather quirky and absurdist tone found in many of their projects, Burwell’s great gift is to provide music that emotionally grounds the characters, finding notes of lyricism, melancholy, and pathos in the strange stories of lovelorn puppeteers, sex researchers, and bumbling kidnappers.

For Carol, Burwell tried to capture the peculiar mixture of passion and distance that characterizes Therèse’s initial attraction to Carol. Because Carol comes across as both elegant and a bit aloof, Burwell not only utilized ambiguous harmonies, but also “cool” instruments, such as piano, clarinet, and vibes.

On his website, Burwell identifies three main musical themes in his score for Carol. The first is a love theme introduced in the film’s opening city scene. It presages the relationship even before we’ve been introduced to the characters. The second theme underscores Therèse’s fascination with Carol. Says Burwell, “This is basically a cloud of piano notes, not unlike the clouded glass through which Todd Haynes and Ed Lachman occasionally shoot the characters.” The third theme captures the characters’ sense of loss when they are separated. Knowing that Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara would convey the characters’ pain in their performances, Burwell opted instead to use open harmonies (fourths, fifths, and ninths) to communicate their sense of emptiness.

Burwell orchestrated the music for chamber-size ensembles to maintain the sense of intimacy between the characters. Some cues feature as few as four instruments while others were performed by as many as 17 musicians.

Burwell’s spare, modest score is a departure from the style Haynes explored in his previous foray into this territory: his Douglas Sirk homage, Far From Heaven (2002). Elmer Bernstein’s score for that film was lush and emotionally expansive, aping Frank Skinner’s musical stylings in films like Magnificent Obsession (1954) and All That Heaven Allows (1955). Burwell wrote only 38 minutes of music. Yet it all is beautifully attuned to the film’s mood of quiet desperation.

Thomas Newman earned his thirteenth nomination for Bridge of Spies. (Insert Susan Lucci joke here.) Newman, of course, descends from film composing royalty as the son of the renowned classical Hollywood tuner, Alfred Newman. Yet, despite Newman the Younger’s distinguished career in Tinseltown, Newman the Younger has a long way to go to catch his pops. Alfred won nine Oscars and accrued more than forty nominations.

Newman’s music has graced some of the most beloved American films of the past three decades, such as The Shawshank Redemption, American Beauty, Finding Nemo, and Wall-E. Although he is known for his versatility, an NPR story on his score for Bridge of Spies notes that Newman has become known for passages that incorporate “quirky, layered piano writing and jagged string motifs.”

Newman and Spielberg save the score’s biggest moments for the film’s climax and epilogue. Indeed, more than half of the film’s score is backloaded into its last three cues, which together account for about 25 minutes of music. Displaying Newman’s full emotional range, “Glienicke Bridge” anxiously underscores the tense prisoner exchange that delivers Rudolf Abel back into Soviet hands. “Homecoming” features solo trumpet and oboe to convey James B. Donovan’s sense of validation now that his fellow commuters’ scowls of disapproval have turned to smiles of patriotic pride.

Newman’s score for Bridge of Spies is a very solid piece of work evincing the craft and refinement displayed by earlier masters like Jerry Goldsmith and John Barry. Yet the music’s modesty and conventionality make it the kind of score all too easy to overlook.

The Legends: John Williams and Ennio Morricone

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015).

Oddsmakers have tabbed our final two nominees, John Williams and Ennio Morricone, as the most likely to take home the big prize. The former is nominated for Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the seventh film in George Lucas’s series and the seventh scored by Williams. Coming 48 years after the composer’s Oscar win for the first Star Wars film, Williams’s music updates the neo-Romantic style he helped to revive in the 1970s. It also adds new themes for key new characters, such as Rey and Kylo Ren.

Williams wrote a massive amount of music for The Force Awakens. (Indeed, the 102-minute score is more than double that of Newman’s score for Bridge of Spies.) But very little of it simply replicates materials from the previous films. By Williams’s own count, only seven minutes of the score function as “obligatory” references to his own immediately recognizable themes.

As in his previous work, Williams shows enormous skill in juggling the various leitmotifs that are attached to the film’s dramatic personae, often moving a motif through different instrument combinations in order to vary the color and timbre of each cue. And Williams’s sure touch with this material undoubtedly enhances J.J. Abrams’ everything-old-is-new-again approach to The Force Awakens, a strategy that seems to have satisfied long-time fans, many of whom probably have dusty old compact discs of the composer’s earlier Star Wars scores.

The score for The Force Awakens earned Williams’s his fiftieth nomination and it is a fine addition to his already considerable oeuvre. Still, considering that Williams has won Oscars on five previous occasions and the been-there- done-that aspect of the enterprise, it is hard to believe that this score will bring the composer his sixth statuette. Thankfully for him, Williams’s reputation as one of the greatest composers to work in the film medium is already firmly secured.

That leaves just Ennio Morricone, the equally legendary Italian composer whose collaborations with Sergio Leone redefined the sound of the Western. Nearly fifty years after Morricone’s theme from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly topped U.S. record charts, Morricone garnered his sixth Best Original Score nomination for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight.

The film marked Morricone’s return to the genre after several decades of avoiding it. According to the composer, most directors who approached him simply wanted him to replicate the sound of his great Spaghetti Western scores. Morricone preferred to pursue projects that let him stretch in other directions.

Tarantino gave the Maestro a free hand in developing the score of The Hateful Eight, and Morricone responded with one of his best scores in decades. Aside from his characteristic use of vocal chants as rhythmic accents, the score for The Hateful Eight largely avoids the sort of psychedelic touches and extravagant tone colors found in his Spaghetti Western scores. Gone are the electric guitar, ocarina, whistles, and coyote yelps that established Morricone as a kind of musical meme. Substituted instead are much more conventional orchestral colors with the strings and wind sections taking prominent roles in The Hateful Eight.

Perhaps one reason for this move back to classical Hollywood convention is due to the hybrid qualities of Tarantino’s story. As Peter Debruge noted in his Variety review, The Hateful Eight is “a salty hothouse whodunit that owes as much to Agatha Christie as it does to Anthony Mann.” Morricone himself seems to concur. In an interview with Rolling Stone, the composer added, “Quentin Tarantino considers this film a Western; for me, this is not a Western. I wanted to do something that was totally different from any Western music I had composed in the past.”

Morricone’s score has a “theme and variations” structure that shows him adeptly changing his tempo, texture, and instrumentation to adapt his main theme to new dramatic contexts. His Overture provides the basic template for the score. The low strings and winds play a sustained minor chord that sneaks into the soundtrack. After a few seconds, the upper voices enter playing chords on the first and third beats of each measure to outline the basic harmonic progression of the main theme. Eventually an oboe will enter playing a repeated interval as a counterrhythm over the top of this pattern.

This gives way to the strings, which intone a serpentine diatonic melody that provides the spine for the rest of the cue. Gradually, Morricone introduces more instruments, such as vibes and brass, to vary the tone color and even adds a simple bridge section that consists of a series of soft, chromatically descending chords. After a brief restatement of the main melody, the cue finishes with a series of long sustained chords marked by shifting harmonies in the inner voices. The clarinet plays a fragment of the main theme before it eventually fades out. The cue never comes to the kind of climax that a traditional cadential structure would provide. Instead it simply unwinds itself.

The central theme is probably given its most elaborate treatment in the main title, “L’Ultima Diligenza di Red Rock – Version Integrale.” A steady timpani pulse and a sustained pitch in the strings provide a pedal tone against which a new melody is introduced in the contrabassoon’s low register. This musical figure has a serpentine quality like the other, and it has been written to function as counterpoint to its predecessor at later moments when the two will be interleaved. Morricone gradually introduces more instruments to thicken the texture and even adds brass and pizzicato accents as embroidery atop the main theme. A hi-hat cymbal adds some rhythmic variety to the basic pulse of the timpani.

After a brief detour into some transitional material, the main melody returns, but now played by strings, xylophone, and muted brass instruments. The main musical figure continues to be restated with new ideas simply piled on top. As the music grows in both volume and intensity, Morricone adds trills and furious agitato string runs to create a cacophonous, but organized musical chaos. The cue climaxes with the melody played fortissimo in octaves by the violin section, soaring toward a sudden and abrupt stop. After a short pause, the contrabassoon quietly returns to play a brief musical coda that eventually fades to silence.

Morricone has long been a master of this type of musical structure. He’ll start with a simple musical idea, but then adds different countermelodies or obbligatos to vary its mood and tone. The ongoing accretion of elements creates the effect of a long crescendo that eventually finds release in silence. (For an earlier example of this kind of technique, see his cue for “The Desert” on The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly soundtrack.)

Beyond its purely musical effectiveness, though, “L’Ultima Diligenza di Red Rock” exudes a roiling tumult that fittingly captures the sense of deception and distrust that will pervade Minnie’s Haberdashery. The musical mood remains mostly dark and ominous throughout, leavened only by the bright solo trumpet fanfare that underscores Sheriff Chris Mannix’s reading of Major Warren’s Lincoln letter.

Tarantino’s trust in the Maestro was amply rewarded. This is a score that no one but Morricone could produce. As was the case with Jóhann Jóhannsson’s score for Sicario, it seems to be the best thing about The Hateful Eight. Tarantino wanted a soundtrack album for one of his own films that he could proudly place alongside other Morricone albums in his collection. He got it and then some.

Prediction: The Maestro finally gets his due! Although Morricone received an honorary Oscar in 2007 for his “magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the art of film music,” none of his individual scores have received awards from the Academy. I expect that to change next Sunday night. In fact, betting odds put Morricone’s chances of winning an Oscar for Best Original Score at 1 to 5. That means that a five dollar bet will net you one dollar profit if you win. That is about as close to a sure thing as you are likely to find in the gambling world. And even I’m not dumb enough to buck that trend.

In truth, I would be happy to see any of these composers take home the Oscar. I’ve enjoyed their contributions to the art of film music for much of my adult life. But, for me, the only real question is this: How long will the standing ovation be as Ennio Morricone prepares to give his acceptance speech? I put the over/under at 65 seconds.

Variety offers overviews of the nominees for Best Original Song here and Best Original Score here. Both pieces include comments from the composers and songwriters competing for this year’s awards.

You can find interviews with nearly all of the nominees for Best Original Score: Morricone, Williams (here and here), Newman, and Johannsson. Carter Burwell’s notes on Carol can be found on his website.

Emilio Audissino’s book on John Williams offers a terrific overview of the composer’s career. For a study of Morricone’s compositional techniques and style, see Charles Leinberger’s monograph on The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly in Scarecrow Press’s series of Film Score Guides. My book The Sounds of Commerce includes a chapter on Morricone’s spaghetti western scores.

More on Morricone: The Maestro weighs in on the film scoring process in Composing for the Cinema: Theory and Practice of Music in Film, which is coauthored with Sergio Miceli. You can listen to the opening cue of the score for The Hateful Eight here.

P.S. 25 February 2016: Thanks to Peter Brandon for a correction concerning the Canadian identity of The Weeknd, Quenneville, and Belly.

LONDON, ENGLAND – DECEMBER 08: Composer Ennio Morricone is seen during a Live Recording for the H8ful Eight Soundtrack at Abbey Road Studios on December 8, 2015 in London, England. (Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Universal Music)

The sirens’ song for Oscar

The Lego Movie.