Archive for the 'Film piracy' Category

When media become manageable: Streaming, film research, and the Celestial Multiplex

Never coming to the Celestial Multiplex: Liberty Belles (Del Henderson, 1916).

DB here:

A directors’ roundtable in The Hollywood Reporter says a lot in a little.

Fernando Meirelles: This June, The Two Popes was in 35 festivals. Then we were going to have two or three weeks of theaters. And then the [Netflix] platform. I mean, it couldn’t be better.

Martin Scorsese: We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

Meirelles casually omits DVDs, at one point the most rapidly adopted format of consumer media. Yeah, what ever happened to discs? And in what follows, I’ll take issue with Scorsese’s claim that streaming has triggered a revolution. It’s more a case of evolution that issued in a sweeping change, like Engels’ transformation of quantity into quality, or Hemingway’s claim that he went broke slowly, then quickly.

More important, I’ll try to assess the impact streaming has had on what Kristin and I and other researchers and teachers try to do–study film as an art form in its historical dimensions.

Managing your time, and your movies

If we’re looking for a revolutionary turning point, I’d suggest the moment that movies no longer became appointment viewing. When they played theaters you had limited access. The film was there for only a while (even The Sound of Music eventually left) and you had to watch it at specified times. On broadcast TV and cable, the same conditions applied. But with the arrival of consumer home videotape in the 1970s, the viewer was given greater control.

Akio Morita of Sony called it “time-shifting.” The phrase, shrewdly positioned as a defense of off-air copying, captures a fundamental appeal of physical media. You could watch a film at home, and whenever you wanted to. Yes, VHS and even Beta yielded shabby images and even worse sound, but (a) theatres were often not much better, and (b) a video rental was cheaper than a movie ticket. Most important was a general rule of media technology: For the mass market, convenience trumps quality.

Videotape swept the world in the 1980s and gave films an aftermarket. Many an indie filmmaker could get financing for a project on anticipated tape sales. The laserdisc gained some attention in the 1990s, becoming a sort of transitional format. It improved quality (better analog picture, digital sound) but had drawbacks too. A movie wouldn’t fit on a single disc side, and a laserdisc was pricier than tape. LD remained a niche format, chiefly for educators and home-theatre enthusiasts.

The laserdisc was superseded by the DVD, introduced in 1996. Journalists claimed that it enjoyed the fastest consumer takeup in electronics history. Discs were more convenient than tapes, and proof of concept had been provided by the success of CDs for music. To compete, cable companies introduced “video on demand,” a time-shifting compromise between scheduled cable delivery and rental of tape or disc. People still use cable VOD, and for some purposes it’s a cheaper alternative to committing to subscription services.

Reviewing The Irishman, a critic suggested that most people will skip seeing it in theatres and watch it on Netflix, where it’s “more manageable.” With tape and disc, either analog or digital, consumers became accustomed to a huge degree of manageability. They could pause, skip ahead or skip back, race fast-forward or –back, play slowly, and above all play the movie over and over. DVDs made all these options quicker and more convenient than tape had. The market boomed. Video stores made discs available for rental, as tapes had been, and retail stores offered them for sale, at increasingly low prices.

But there were problems. In the 2000s there was a glut of DVDs, and consumers began to realize that a few weeks after release many titles would end up in the bargain racks. A brisk secondary market developed thanks to the US “first sale” doctrine, most virtuosically exploited by Redbox. Worse, there was piracy. Pirating analog tapes degraded quality across generations, but with digital discs you could rip perfect clones. Any teenager could hack past region coding and anticopying software.

The Blu-ray disc was an improvement on the first-generation DVDs, and it came along as more people were buying widescreen and high-definition home monitors. Properly mastered, Blu-ray discs looked good, and they had bigger storage capacity. Some consumers got excited, but the improved format couldn’t arrest the headlong decline of disc sales. In addition, the industry’s rationale for Blu-ray was its resistance to rippng, but hackers breached the codes with ludicrous speed.

From this angle, streaming is parallel to digital theatre projection : a new phase in the war against piracy. Likewise, as in theatrical screenings, you’re paying for an experience, not an item. You’re not buying an object you can copy or resell. If a movie is available only on streaming, you’re renting something, not owning it legally. One aspect of manageability—personally possessing a movie—is traded away for convenience and, ultimately, for limited access, as I’ll try to show.

Not so gently down the stream

With streaming, the age of appointment viewing seems more or less over. And the infinite vista of the Internet has encouraged tech-heads to imagine something like the Celestial Jukebox, a vast virtual multiplex in which all movies will be available. If iTunes and Spotify did something like this for music, why not cinema?

Let’s consider the pluses and minuses of streaming for ordinary consumers and for filmmakers.

Obviously, there’s convenience. After the monstrous tape cassettes, DVDs looked adorably slim. Now, gathering in slippery stacks, they have their own sinister aura. With streaming, there’s no need to run out to the video store or to buy new shelving to support a bulging library of discs.

There’s also price, compared to either theater tickets or cable fees. From $6.99 per month (Disney+) to $12.99 (Netflix), streaming services promise to provide TV and movies quite cheaply. And there’s the range of choice, which even on second-tier streamers exceeds the capacity of most towns’ video stores back in the day. Finally, there are many obscure films lurking in the corners of most streamers, so the joy of discovery is still there to a degree.

On the minus side, there’s one that gets the most press—the further erosion of “the theatrical experience.” Critics emphasize the pleasures that come from being in an audience, but this always seems to me overrated. More valuable to me are the scale of image and sound you get in a theatre. I like my movies to loom.

Above all, there’s a virtue in the lack of manageability. In the theatre you can’t pause the movie or run back or skip ahead. You can close your eyes, look away, or leave, but at bottom you’re there to turn your sensorium over to the filmmaker, to go through an experience you don’t control. This unshakeable grip on your attention yields some of cinema’s most powerful effects.

The condition of privatized viewing isn’t unique to streaming, of course. Nor is another drawback, that of the cyclical expiration and refreshing of “content” on streaming platforms. Admittedly, we’re warned. Newspapers and websites run alerts notifying us when a title is leaving a service—perhaps for a little while, perhaps longer, perhaps forever. And this situation is a bit like DVDs’ going out of print. But at least some disc copies exist to be sold second-hand or cloned as files. In working on my book on the 1940s, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I could track down arcane titles on out-of-print discs, and at fair prices. When something not on disc leaves streaming, how do you access it?

I think there will be some pushback when subscribers learn about the costs that more and more services are tacking on. Yes, with Amazon Prime for $119 per year you get access to many films, along with other services. But for a great many films Amazon demands an extra rental fee and very short-term access. Within Amazon, there are channels (Britbox, HBO Now, Starz, Cinemax et al.), all of which demand further subscription payments. As people start to realize that streamers will have exclusive licenses for titles, they’ll feel pressure to subscribe to many services. Here, as elsewhere, the total streaming price tag starts to look like cable fees. Even the New York Times has noticed.

Another problem won’t bother most consumers, but it does matter. A streamed title will occasionally be in an incorrect aspect ratio. Most commonly, a Scope (2.39 or so) image will be cropped to 1.85. I noted this some years back, relying on a website showing faulty Netflix transfers, but that site seems to have been taken over by … Netflix itself.

Netflix will say, with all “content providers,” that they get the best material they can from their licensors. I don’t watch streaming enough to know how common wrong aspect ratios are, but if you know of examples, I’d like to hear.

Finally, even streaming companies can collapse. Unless Apple buys a studio (Lionsgate? MGM? Columbia?), it must rely on original content, and it could well flop. On the day I’m writing this, one hedge fund manager predicts we have reached peak Netflix. Given greater competition, slower growth, and accelerating cancellations, he maintains that Netflix is on the wane. If it scales back or fails (it currently carries $12.43 billion in debt), what will happen to its licensed material and its original content?

What about creators? Filmmakers, especially screenwriters, have enjoyed boom times. It may be a bubble, with over 500 scripted series available on broadcast, cable, and streaming. Still, it has given everyone a lot of opportunities. Documentary filmmaking in particular has enjoyed a shot in the arm.

And features are still doing quite well, at least on Netflix. Of the streamer’s top 10 releases in 2019, seven were features. But those proportions may change. Aside from big theatrical movies licensed from the studios, the impact of proprietary “event” programming (War Machine, Bird Box) has been fairly ephemeral. (Obviously Roma and The Irishman are exceptions.) The strength of streaming, it seems to me, is the same thing that sustained broadcast TV: serial narratives. Hence the popularity of Friends and The Office, as well as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black.

Like network TV, a streamer needs a reliable, constant flow of content—not only many shows, but many episodes. The model of the series, if only in six or eight parts, secures the loyalty of the viewer for the long term. Even if all episodes are dumped at once, the promise of continuation after an interval of a year or several months keeps the viewer willing to hang on till the next season.

The pressure on the creators is predictable. Since form follows format, writers and producers will be pushed to come up with series ideas. A friend of mine pitched a feature-length movie to a streaming service. The suits loved the idea but wanted it as a series and were already scanning the script outline for a plot point that could launch a second season. Some of the streaming series I’ve seen, notably Errol Morris’s Wormwood, seemed to me stretched.

If a filmmaker lands a feature film on a streaming platform, other problems could follow. We’re well aware that independent filmmakers gain few royalties from streaming; their big check tends to be the initial acquisition. At the same time, they can’t be sure that people are watching their entire movie. My barber couldn’t stick with The Irishman, even with pee breaks.

Streamers seem to have accepted grazing as basic to the viewing experience. For purposes of measuring total viewership, Netflix counts a “viewing” of a film or program as a minimum of two minutes. In the light of the two-minute rule, we might expect filmmakers to crowd their opening scenes with plenty to grab us. That goes back to TV and TV-influenced films, of course, which tried to have a strong teaser even before the credits. Now, it turns out, streaming pop songs are being crafted with shorter intros and earlier choruses “to get to the good stuff sooner.” Maybe filmmakers will be trying the same thing. Maybe they already are.

Streaming and film research

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018).

Finally, what are some consequences of streaming for researchers, educators, and your all-around obsessive cinephile?

I think it’s fair to say that home video, in the form of tape, laserdisc, and digital disc, democratized film study. From the late 1960s on, I traveled to archives and film distributors to watch films for my research. It was troublesome, time-consuming, and costly. As a grad student I took a bus from Iowa City to Chicago to watch 16mm prints of Dreyer and Sontag films. I drove to Eastman House to see films in projection. I stayed in Paris a couple of months to work at the Cinémathèque Française on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse.

As a prof here at Madison I spent hundreds of hours watching prints in our Center for Film and Theater Research. Over the decades I trekked to Denmark for Dreyer and 1910s films, to Japan for silent films, to Paris and Munich and the BFI and MoMA and UCLA and Eastman House and the Library of Congress, and above all Brussels for many, many projects. Collectors, from Manhattan, Tokyo, and Milwaukee helped as well. Kristin and I owe archivists everything.

The terrible quality of films on tape didn’t help me study visual style, but laserdiscs were a big improvement. (Hong Kong films tended not to be in Scope on tape but were on LD.) And one LD format, CAV, was frame-accurate; you could study a shot frame by frame, something not possible with many DVDs. There’s always a trade-off with any technology.

Even after even after DVDs arrived I kept up my travels. I could use discs for bulk background viewing, but often I still had to rely on prints. Sometimes I wanted to count frames (handy in looking at Soviet montage and Hong Kong action). Moreover, looking at film prints revealed that the color palettes on DVDs could be quite different, and soundtracks were often cleaned up for the home market. And of course thousands of films, especially from outside Hollywood or in the first decades of cinema, were never going to be available on consumer video. My most recent extended archive stay, in Washington in 2017 thanks to a Kluge Professorship, showed me the glories of the 1910s in prints that are mostly accessible only to researchers.

What do scholars of an analytical bent need? Entire films that can be paused. Frame stills, made photographically or through software. Clips as evidence for our claims. Stills and clips are our equivalents to quotation for literary scholars and illustrations for art historians.

Apart from convenience and cost savings, the disc revolution yielded something I couldn’t get otherwise. In an archive, it’s impossible to study film-based 3D cinema. But thanks to Blu-ray, I can stop on a 3D frame. (. . . And, for instance, spot the way Hitchcock makes the clock quietly pop out in Dial M for Murder, below). This is a unique benefit—but a waning one, as 3D discs are increasingly hard to find and 3D monitors scarcely exist any more. As I said, trade-offs.

From this standpoint, Netflix and its counterparts offer a step down from DVD and Blu-ray. In terms of choice, many films aren’t currently available on streaming, and many more never will be. You can pull a DVD off a shelf whether you’re online or not, but for streaming you need a good connection. The controls of a streaming view aren’t as precise as those on a DVD player; slow forward and back to study cuts and gestures aren’t feasible, it seems.

When cable cropped films, as it frequently did, you had recourse to DVDs, perhaps even from foreign sources. But as exclusive licensing increases, only one service will have a title. Frame grabs are possible with some software, but clips are more difficult.

Worst of all, many worthwhile films will apparently never find their way to disc. I first noticed this in 2017 when I wanted to buy a copy of I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, a Netflix release of a Sundance title. As far as I can tell, it’s not available on DVD. The same fate has befallen one of my favorite films of 2018, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only a few years ago it would be unthinkable for a Coen Brothers film not to find DVD release. Even Roma has had to wait for a Criterion deal to make it to disc. Clearly Netflix, and perhaps other streamers, believe that putting films on disc damages the business plan. So Meirelles doesn’t include DVDs in the lifespan of The Two Popes.

Without DVDs, some cinephiliac consumers are lamenting, rightly, the loss of bonus materials. The Criterion Channel has been exceptionally generous in shifting over its supplements to the streaming platform, but other companies haven’t been. Scholars and teachers rely on the best bonus items, including filmmaker commentaries, to give students behind-the scenes information on the creative process. There are, I understand, rights issues around supplements, and bandwidth is at a premium, but there’s no point in pretending that the loss of disc versions hasn’t been important.

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas put forth the question debated in the directors’ roundtable I mentioned: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

Still, the big changeover hasn’t happened quite yet. Every year has its failed blockbusters, and films big and middling and little (Blumhouse, for instance) still continue. Arthouse theatres, which rely on midrange items, indie production, and foreign fare, are putting up a vigorous fight, emphasizing live events and community engagement.

Meanwhile, streaming makes film festivals and film archives more important. Festivals may host the few plays that a movie gets (as in the 35 fests which ran The Two Popes), and filmmakers, as Kent Jones remarks, are eager for their films to play on the big screen in those venues. Archives will need not only to preserve films but also make classics and current movies available in theatrical circumstances. Smart film clubs like the Chicago Film Society and our Cinematheque keep film-based screenings alive.

Before home video, few film scholars undertook the scrutiny of form and style. Those who did had to use editing machines like these. (One scholar called my study of Dreyer, not admiringly, the first Steenbeck book.) Ironically, just as an avalanche of films became available for academic study, and as tools for studying them closely became available for everyone, most researchers turned away from cinema’s aesthetic history and a film’s specific design in order to interpret their cultural contexts. There were exceptions, like Yuri Tsivian’s efforts to systematically study patterns of shot length, but they were rare.

Whatever the value of cultural critique, one result was to leave aesthetic film analysis largely to cinephiles and fans. Thankfully, the emergence of the visual essay, in the hands of tech-savvy filmmakers like kogonada and Tony Zhao and Taylor Ramos, eventually attracted academic attention. Film analysis has returned in the vehicle of the video essay, which is a stimulating, teaching-friendly format. Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have participated in this trend through our work with Criterion and occasional video lectures linked to this site.

All this was made possible through the digital revolution, or evolution, and we should be grateful. Still, streaming filters out a lot of what we want to study. It’s clear that, for all their shortcomings, physical media were our best compromise for keeping alive the heritage of critical and historical analysis of cinema. We’ve largely lost physical motion pictures as a contemporary medium. (How many young scholars, or filmmakers for that matter, have handled a 35mm print?) Now, to lose DVDs and Blu-rays is to lose precious opportunities to understand how films work and work on us.

Thanks to all the archivists, collectors, and fellow researchers who made our research so fruitful and enjoyable in the pre-digital age.

A good overview of the streaming business at this point is “The future of entertainment,” in The Economist.

Kristin discusses the fantasy of the Celestial Multiplex with archivists Schawn Belston and Mike Pogorzelski. For examples of how to watch a film on film slowly, go here. Samples of editing-table discoveries are here and especially in the Library of Congress series that starts here. In another entry, I discuss the use of 3D in Dial M for Murder.

P.S. 24 January 2020: Then there’s this, from Facebook.

Dial M for Murder (1954).

Sweet 16

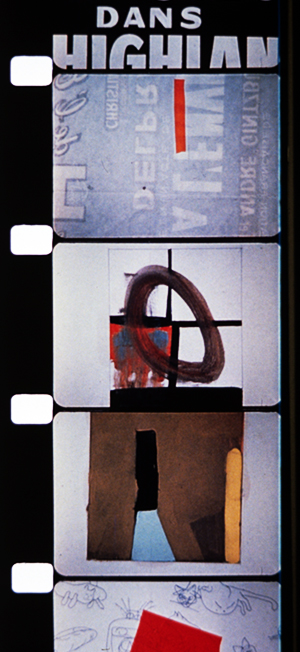

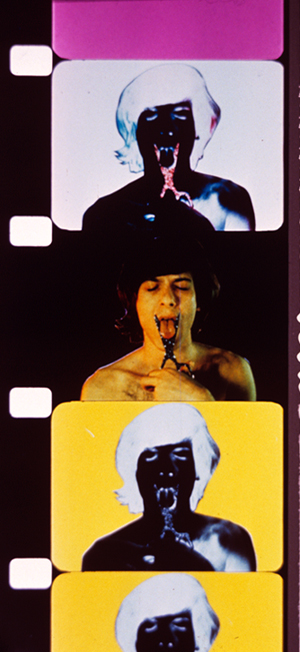

REcreation (Robert Breer, 1956); T.O.U.C.H.I.N.G (Paul Sharits, 1969).

DB here:

Snows and thaws and refreezing, amplified by a torrential rain, gave water a new path into our basement. We’ve spent about two weeks emptying bookshelves, drying them out, and shifting books to other places. No volumes were damaged, but we had to make space in the dry areas for the migrant titles.

That meant facing up to the problem of 16mm.

The solution was drastic.

Narrow-gauge movies

My film collecting started with 8mm. Not super-8; that was invented later. (Imagine how old I am.) I made my own movies in 8, but I also bought, from the venerable Blackhawk Films of Davenport, Iowa, copies of films in that format. Most memorable was the Odessa Steps reel from Battleship Potemkin, which I projected often on my bedroom wall.

Not until I went to college and joined a film club did I lay my hands on 16mm. I suppose if you start out handling 35mm, 16 looks skinny and 8 looks like a toy. But moving from 8 to 16, I could see only improvement. You could, with the sharp eyes of the teenage geek, actually see the image on the strip. I projected many films on our JAN surplus projectors, and one weekend I hauled a print of Citizen Kane to my apartment to watch several times. Do I need to add that all this was in the 1960s, long before films became available on videotape?

Arriving in Madison in 1973, Kristin and I bought a Kodak Pageant, the 16mm workhorse. Not as good as a Bell & Howell, most aficionados would tell you, but fairly cheap and easy to handle. When we moved from apartment to apartment, the Pageant went with us.

In 1977 we bought a house, and I set up a jerry-rigged projection room in the unfinished basement. In our second house, where we still live, I was able to set up something more permanent. Now there were two projectors encased in a booth and mounted on a platform.

We spent many hours watching movies in that currently soggy basement, with its burgundy carpet and dark wood paneling. Although the room lacked the comforts of what we think of as a home theatre, we sometimes screened things for big groups, either a party or once in a while students in a seminar.

In both venues, we previewed movies we were showing in courses and revisited some of our growing collection: The Shop Around the Corner, High and Low, True Stories (must blog about that some time), You Only Live Once, and so on. I’ve already expounded on the key role of His Girl Friday in our mini-cinémathèque.

By then Kristin and I had also started working with 35mm prints in archives and with 35mm trailers we scavenged to make slides for lectures. For a brief while we even had 35mm in our screening space, but with only one projector, shows stretched too long. Although home video had taken off, Betavision, VHS, and even laserdiscs couldn’t compare to a good 16 copy. We continued to collect and show on film, as did our department.

In the last decade, improvements in digital projection, along with the arrival of Blu-ray, led to the decline of 16 in our local media ecosystem. Our department still shows a lot of 35, but 16 seems mostly the province of our experimental and documentary courses. As for us, we hadn’t screened 16 at home for some years. Then came the February leak, and we had to face the problem.

We’d already given many of our 16mm titles to the department, keeping our most fond treasures at home, thinking we’d watch them some day. Now we needed the space that those cans and cases occupied. Anyhow, it was probably time to let go. So we decided to surrender the features, the shorts, the cartoons, the splicers and the rewinds and the six Pageants—everything.

Our house is a museum of defunct technology. Just recently I surrendered my lovely Teac reel-to-reel tape recorder. Packed away are hundreds of Beta and VHS tapes. On groaning shelves sit hundreds of laserdiscs, mostly Asian. Yet under a roof that houses no fewer than six laserdisc players, there is no trace of the predominant nontheatrical film format of the twentieth century.

FOOFs

Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates (1966).

Nowadays it’s easy to own a “film”—or rather a disc or file or stream of pixels fed to your display. (Though I wonder what it means to “own” something sitting on the Cloud in your virtual locker.) Back in the day, joining the ranks of 16mm collectors meant a real commitment. You needed to buy gear, you needed to clean and inspect the films, and you needed to learn a little projector maintenance. You probably subscribed to The Big Reel and Classic Film Collector, tabloids that ran ads selling or swapping prints and equipment. And you usually went to film collectors’ conventions, jamborees of selling, trading, and movie watching. The three biggest events, Cinecon (Los Angeles), Cinefest (Syracuse), and Cinevent (Columbus, Ohio), brought together the overwhelmingly male tribe of FOOFs: Fans of Old Films.

FOOF collectors had good hunting in those days. There were plenty of 16mm prints floating around, but quality varied. The best were those cast off from legit distributors. Made from internegatives drawn from 35mm positives, they usually had good tonal values. At the other end of the scale were the dupes, copies pulled from 16mm distribution prints. These ranged from acceptable to awful; but if you wanted a rarity, you might have to spring for a dupe.

In the middle zone were TV prints, probably the majority of copies in circulation. When studios licensed their pre-1948 libraries to television, go-between companies like C & C put together packages of prints to be sold to local stations around America. Small stations in the hinterlands harbored scores of 16mm copies, to be trimmed, filled out with commercials, and broadcast outside prime time, and sometimes within it as “Million Dollar Movie” or whatever. It’s still not fully appreciated, I think, how many baby-boomer auteurists around the country caught classics in the pre-dawn hours on local television.

But as network and syndicated programming expanded, there was less room for old movies. Why run a 1936 Paramount picture when you could show color re-runs of Bewitched or The Six Million Dollar Man? The stations’ 16mm prints were headed for landfill when enterprising collectors and entrepreneurs salvaged them. You could tell when you got a TV print. It might carry a packager’s logo; it would have low contrast; and splices between scenes would signal where the commercials had been jammed in.

FOOFs had their demons and demigods. Principal among the demons was one colorful character, who had the habit of bothering collectors circulating versions of old classics to which he claimed current rights. In The Sneeze, FOOFs made fun of the man who, releasing recovered prints of Birth of a Nation and Keaton films, made sure his own name featured prominently in the credits.

Among the demigods were Kevin Brownlow, he who had rescued Napoleon, and David Shepard, who started out at Blackhawk and eventually founded Film Preservation Associates. Most legendary of collectors was William K. Everson, who died in 1996. Thousands of prints were squeezed into his two Manhattan apartments and spilled over into the storage areas of NYU’s film department. He acquired many of his films in exchange for services he rendered to Hollywood studios. His gems were screened in his courses, in sessions of the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society, and in lectures he presented around the world. I remember his excellent presentation on Joseph H. Lewis at Chicago’s Art Institute Film Center, where he showed clips from Lewis’ Poverty Row productions and even some credit sequences Lewis had crafted.

Bill brought a magnificent selection of titles to Madison in the early 80s, and many of them, such as Bulldog Drummond (1929) and Justin de Marseille (1935), remain rarities. Generous beyond measure, he also let NYU faculty and students borrow his movies. When Annette Michelson needed to see East of Borneo (1931) for her essay on Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936), she turned to Bill. All of this largesse was made possible by the portable, user-friendly format of 16mm.

Freezing the frame

Teachers, filmmakers, and collectors had a special relation to 16mm. In addition, as researchers, we developed an unusually intimate rapport with the format. When I started teaching, I felt the need to illustrate my lectures with images from the films. My first efforts involved setting up a 35mm still camera on a tripod and photographing from the screen. If the projector could stop on a frame, so much the better; but even if not, you might snag an acceptable shot. The projected image would be surrounded by darkness. Today I wince at the results, as with this shot from Crime of M. Lange, one of the few old slides we haven’t cast out.

You could get sharper slides with a gadget called a Duplicon, but it cropped the 4 x 3 image to something like 3 x 2.

When Kristin and I decided to write Film Art: An Introduction, the few introductory textbooks relied almost entirely on production stills, those images shot on the set and circulated to promote the film. The Museum of Modern Art had an archive of production stills, and then as now, publishers turned to such collections for illustrations. As part of the first generation of university-trained film researchers, we doggedly insisted that all our examples would be actual film frames.

Today, digital video has made grabbing frames easy. But before the late 1990s, it was hard. Videotape frames looked terrible, as some books from the 1980s attest. To get decent quality, you needed access to prints. You needed a way to put a reel onto rewinds or, ideally, a flatbed editor like a Steenbeck. And you needed a camera with an enlarging attachment. When you’d copied your frames, you took the exposed film to a lab, where you hoped for a passable result. Black-and-white shots were easier than color, which required blinding lamps of a color temperature matched to Ektachrome or Fujichrome or Agfachrome.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

But most of the films we wanted to illustrate we could find only on 16. We rented prints and then took stills on a rickety gadget built for us by our friend David Allen. David bolted a pair of rewinds to a plank of plywood. That plank rested on a little table. Into the plank was cut a square slot for an upright light box. The box contained a bulb and was surmounted by a square of translucent plexiglass. The bulb could be put at the bottom of the box, for a photoflood lamp, or near the top with a cooler and dimmer appliance bulb for black-and-white. You positioned the film on the plexiglass and aimed the camera down at the film. A crude zoom lens allowed us to photograph a couple of frames of 16mm and one of 35.

We took the light box on our travels. Archivists certainly looked at us oddly when we brought the thing in, but they usually gave us permission to use it. We’d watch the film on a flatbed and bring the light box over alongside it. Laying the film gently on the surface, we’d poise the camera above it.

Here’s an example of what we got with our plywood setup, from Bill Everson’s print of Bulldog Drummond.

Over the years we improved our system. We bought better cameras, with sharper lenses. We found purpose-built attachments that hold the film strip firmly in place. (Alas, Canon and Nikon seem to have discontinued these rigs.) We used smaller lighting units rather than our curious box. For the last few decades we’ve shot horizontally rather than vertically.

Even in this age of video grabs, we make many frame enlargements on analog stock with 35mm cameras. Even if a film is available on DVD, some of the things we study aren’t preserved in that format. Of course many films aren’t available on video at all, and a great many of those were made to be seen on 16mm.

Format churn catches up with us

Notebook (Marie Menken, 1962).

Super-16 lives as a production format, but its older brother is nearly dead. True, a few die-hards like Ben Rivers continue to shoot on 16mm, but its future is mostly all used up. James Benning could make 16mm look like 35; when I asked him how he did it, he answered: “I use a light meter.” But even Jim has switched to digital. As for projection, many colleges and art centers have pitched out their 16 equipment.

Since our earliest editions, Film Art included discussions of two remarkable films: Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958) and Robert Breer’s Fuji (1974). These have not been, and might never be, released on digital disc. Yet by the end of the 2000s, we found that virtually none of the users of our book screened these films for their classes, and curious readers without access to 16mm projection couldn’t easily see them. Reluctantly we cut them from the tenth edition of last year. We replaced A Movie with Koyanisqaatsi to illustrate associational form, and Fuji was replaced by Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue as an instance of experimental animation. Both titles are available on DVD.

Thanks to the Internet we’ve been able to revive our original discussions of the Conner and Breer films on our site here. We hope that will help the few loyal chevaliers who told me that they did indeed use the films in their courses. But our choice points up a larger problem.

So many documentary and avant-garde films were made and circulated on 16mm that we are at risk of losing a very large slice of film history. We’re lucky to have some Stan Brakhage and Hollis Frampton films on DVD, but what about all the other titles that were distributed by Canyon Cinema, the Film-Makers’ Coop, and other groups? We can get DVDs of Frederick Wiseman documentaries, and some classic ones have been made available on archival collections; but there are many more that depended on 16mm platforms. Even bigger is the set of everyday 16mm movies: amateur films, home movies, and hundreds of miles of newsfilm, from both big TV networks and local affiliates. A great many of the “orphan films” championed by Dan Streible and his colleagues are in this narrow-gauge format.

Recall too that the films of those animators and experimentalists who work frame by frame, such as Breer and Paul Sharits and Paolo Gioli, cannot be studied closely on DVD. How could DVD reveal to us the nifty paintwork of Marie Menken’s Notebook? For that you need a light table, or someone able to photograph it and show you.

Archives will retain 16mm projectors and viewing tables as long as they can. They will preserve prints, perhaps migrating the most sought-after ones to digital formats. Passionate collectors like Tim Romano, who zealously pursues lost films and then donates them to the AFI, will find a way to use our cast-off gear. Our Film Studies department will hang onto the format until the last aperture plate cracks.

16mm was so much a part of our work, our play, our education—in short, our lives—that the separation was inevitably poignant. Pinned to the bulletin board in my basement booth was Ellen Levy’s poem, “Rec Room.” It is, I think, about the fragility and faultiness of the 16mm image, as made palpable in home screenings, and about how that fragility nonetheless carries a pulse of vitality. It begins:

The film assumes the texture of its screen

on the first projection. Audrey Hepburn’s face

creases where the rec room paneling once

took exception to it for the sake of

rephrasing it slightly—a lesson

these late viewings have brought home. Home

screen or revival house . . . .

Thanks to Erik Gunneson and Tim Romano for helping us recycle our 16mm stuff.

Media historian Eric Hoyt, in our Communication Arts Department, studies among other things how the American studios disposed of their film libraries. He talks about his research and his book project, Hollywood Vault, here.

The FOOF contingent was unequivocally a force for good. To sample some of its wonkish hijinks, watch Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates.

New York University’s Cinema Studies Department has created an extensive online collection of William K. Everson materials. For more on Bulldog Drummond, see this entry and this essay on the great William Cameron Menzies. Annette Michelson’s essay on Joseph Cornell, “Rose Hobart and Monsier Phot: Early Films from Utopia Parkway,” was published in Artforum 11 (June 1973), 47-57.

Bonded Storage in Fort Lee is part of the history of American cinema, as this article shows.

Paradoxically, you can study films frame by original frame on some laserdiscs, and on VHS tapes too if you are aware of the 3:2 pulldown. See my entry here. As so often happens, progress along one dimension means regression on another. So I cling to my rotting laserdiscs and demagnetizing old tapes.

James Benning discusses how digital cinema changed his artistic practice at Bombsite. An earlier entry of ours showcases the efforts of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to preserve experimental cinema.

Ellen Levy’s fine “Rec Room” is available in its entirety in The New York Review of Books (9 October 1986).

To watch a video about our Film Studies program, go here.

Observations on Filmart (This is not a typo)

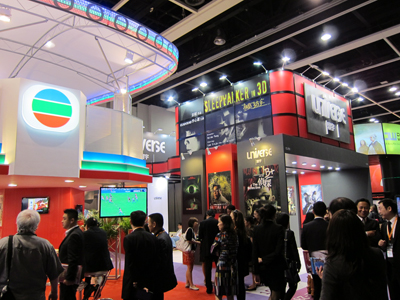

A modest display at Filmart, Hong Kong Convention Centre.

DB here, channeling an apparently apocryphal Soupy Sales line:

Kids, what starts with f and ends in art? No, not that. It’s Filmart, the annual trade gathering that kicks off the Hong Kong Film Festival. Add a space and a capital, and you have the main title of one of our books. Sometimes accidental cross-promotion can work out pretty well, as you see above.

Seriously, though, Filmart is a wonderful event. It includes an opening ceremony to launch the festival, the Asian financing forum known as HAF, the Asian Film Awards (covered a bit here), and a teeming meet-and-greet that sponsors panels, lunches, and hundreds of booths that allow media buyers and sellers to get together. I’ve covered Filmart in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Here are some comments and images from last week’s edition.

The shebang started with the ceremony introducing some of the opening films and their stars. Here the Filmart’s official hostess, Miriam Yeung, is about to go onstage to greet the audience.

And here at the ceremony are the three stars of Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, Gao Yuanyuan, Daniel Wu, and Louis Koo.

Ho Yuhang’s clever neo-noir Open Verdict was a highlight of the shorts collection Quattro Hong Kong 2. Here he is with his star, the radiant Kara Wai Ying-hung, Shaw Brothers action queen and star of both Open Verdict and Ho’s earlier feature Daybreak.

Filmart’s main business takes place in a vast hall, with companies’ displays lined up in rows and along aisles. Most firms have fairly modest stalls, but others are flamboyant, like these big boys for Mei Ah and Universe, two long-established Hong Kong production/ distribution companies.

But the place isn’t so big that you can’t run into old friends, like Margaret Pu (far right) and her colleagues Jack Lee and Dan Zhu from the Shanghai Film Festival.

More movers and shakers: Patrick Frater, CEO of Film Business Asia, and Peggy Chiao, producer (Trigram Films) and doyenne of Taiwanese New Cinema.

At Filmart one can always find some unclassifiable items, as witness the project pictured at the very end of this entry.

New Action on the Mainland

Most panels ran opposite film screenings, so I usually plumped for the movies. But I did attend an intriguing session on “Beyond Box Office: China: The World’s Largest Developing Market.” Sponsored by the Hong Kong Film New Action committee and moderated by Shanghai media executive Bill Zhang Ming, the panel included many Chinese figures and the American Ted Perkins, who has worked for both Warners and Universal and is now serving as executive VP of production for IDG China Media.

Some of the themes discussed echo things I talked about in the added chapters of Planet Hong Kong, but I garnered some new information as well.

*Several panelists pointed out that the stupendous growth in the Chinese box office, over 50% each year, demands that many new cinemas be built. The major cities have now got a good supply of screens, but now the third- and fourth-tier cities need to have more screens. Some commentators spoke of a “new five-year plan” aiming to upgrade and increase the nation’s screens.

*As in America and other countries, a few films typically garner the lion’s share of receipts; one panelist estimated that 80% of income stems from 20% of the films. For the foreseeable future, the big films, from China or the US, will drive the market.

*The growth of the market is even more remarkable given the comparatively small audience (around 20 million, one panelist surmised). Average ticket price is 32 renminbi, or about US$4.88.

*Hong Kong remains essential to the mainland market but also vulnerable. Films with local stars and directors can succeed, and Hong Kong is a key site for financing and packaging projects. But purely local films will remain low-budget items; the bigger films will be mainland co-productions, with some PRC talent and scenery on the screen.

*The popular audience, according to screenwriter-producer Qi Hai, is driven by female tastes: date movies are chosen by the woman, and family films are picked by mothers.

*Ted Perkins pointed out that although recent growth is good for all players, in any film industry there are always more funds in production than can be recouped overall. There will be winners and losers, especially if there’s an overabundance of production, as there currently is on the mainland. Although about 500 films were produced last year, more than half did not find theatrical release or screen in the best cinemas. (Panelists’ estimates of unseen or underseen titles varied from 250 to 400.) Marcus Lim provides a comparable set of figures.

*Some panelists opined that the market lacks directors and stars who are likely to provide success. One panelist estimated that only half a dozen directors have strong track records, and only one star, Ge You, can guarantee an audience.

*Most panelists agreed that 3D was not viable for most films, but in China the new format can help the business in an unusual way. Historically, most mainlanders couldn’t afford going to films, so they aren’t in the habit of attending theatres. They watch films on video or on the Net. Curiosity about 3D may attract new cinemagoers, “educating” spectators to the pleasures of seeing movies on the big screen.

*Most big countries have a well-structured pattern of “windows,” whereby a film moves from the theatre to video, cable, and online. But in China, the expansion of screens is occurring simultaneously with the growth of online distribution, with the danger of piracy. The Chinese will have to come to grips with decisions about pricing and more stable windows.

Seldom do we have a chance to realize that we’re witnessing a historic change in the global film industry. The rise of China is such an event, and film historians should be watching the unfolding process closely.

Changing the film ecology

The Jockey Club Cine Academy, formed last summer, is an educational enterprise guided by the HKIFF Society and funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. It’s a three-year program aiming to increase film literacy among young people. The Academy held a major event during Filmart, a nearly three-hour master class with Jia Zhangke, director of Platform, The World, Still Life, and most recently I Wish I Knew. High school students made up a large part of the audience.

Researcher and editor Wong Ain-ling (above, with Jia) interviewed him about his career and then opened things up for questions. Here are a few points Jia made.

*His recent turn toward documentary filmmaking isn’t a new development for him. When he was starting out, documentaries were the most dynamic part of the PRC film scene. Although the films captured aspects of contemporary life ignored by mainstream movies, they were seldom watched by audiences. So the question for Jia became: “How to change our film ecology?”

He has used a documentary project to spark a fiction feature. In Public (2001) became a draft for Unknown Pleasures. Jia enjoyed eliminating dialogue and narration from his documentaries, relying on peoples’ faces and situations to convey ideas. Critics complained that documentarists couldn’t tell stories, but he wanted mainland audiences to learn to find the latent emotions in the scenes, the “poetic” side of realistic cinema.

*His early films incorporated popular music, including Taiwanese tunes sung by Teresa Teng. Why? During the 1980s and 1990s, mounted loudspeakers broadcast a lot of Mandarin pop songs, making this music just part of a city’s ambience. This was something he exploited in his first feature, Xiao Wu.

*Jia had arguments with censors on his first three features, and those films weren’t widely seen. But in 2004, the censorship system changed, mostly for the better. Yet distributors still block films shot on video from being shown in cinemas, creating what Jia called a “technical censorship.”

*The reports are true: He is making a martial arts film with Johnnie To’s Milkyway firm. Jia wants to examine the imperial system in the period around 1900. He would like to follow it with another historical film, this one about Hong Kong in 1949, centering on two characters, a Communist and a KMT Nationalist.

Like Hong Kong itself, Filmart has a pulsating energy and offers an overwhelming array of choices: you can watch movies, attend events, and just gawk. You must run to keep up. That’s as it should be.

For more coverage of industry doings at Filmart, see Liz Shackleton’s rundown at Screen International (may be proprietary). Another story in Screen International mulls over the prospect that China could fairly soon become the world’s biggest market. See as well several items at Film Business Asia, particularly Stephen Cremin’s article on Chinese coproductions. For our takes on some Jia Zhangke films, you can go to this category.

PS 31 March (HK time): I should have mentioned what the New Action panel did not: Piracy. The LA Times has a good recent article on DVD bootlegging in the PRC, raising the crucial factor I’ve heard mentioned as well: the role of the People’s Liberation Army.

Bugs: The secret history

DB here:

One of the many penalties of watching movies on TV is the prevalence of bugs.

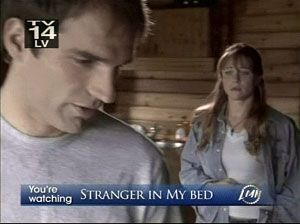

This is the nickname adopted by media makers for those little channel logos and watermarks that hop onto your screen. Sometimes these translucent signatures surface at intervals, to minimally satisfy FCC channel identification demands. Others let you know the movie you’re watching, or will be later.

But just as often the bugs just squat in a corner forever, teasing your eye away from the movie. Bugs are to the 2000s what editing and time-compressing were to earlier eras. “Movies, uncut,” boasts the IFC bug. But not unspoiled.

Bugs are bad enough when they are hovering in a black vacuum, made forlorn by letterboxing.

But they really jump into competition when they take up part of the image. How can you watch what actors are doing when there’s something faintly readable floating up from below?

I find it impossible not to look at a bug occasionally. In dark shots, sometimes it’s the most visible thing on the screen. Even in bright shots I stare at it. Maybe I’m hoping that it will be different this time. Yet when it changes, as it does on the Lifetime channel, I watch it more attentively, which only makes me more annoyed.

It’s like the mesmeric spell of Time Code, ticking away the movie’s life, and yours.

I’m not the first to complain. An eloquent manifesto, originally called Squash the Bugs, dates back to 2000, when the infestation was starting. Several other souls participated in the movement.

We know why bugs are swarming all over TV. Somebody better dressed than you or me is worried that we will be recording A Christmas Story or Smokey and the Bandit or Stranger in My Bed. We might even try to sell copies, or post a clip online. In principle, the bug is a badge of ownership, warning that we could be prosecuted. In practice, nobody expects to sue every user, so bugs help spread the brand. It’s like putting a designer logo on a shirt, making you a walking ad. Who wouldn’t want their bug, microscopic as it is, all over YouTube (which of course tacks on its own bug)?

But like everything else that we take for granted, bugs aren’t new. In their earlier form, they’re rather likable.

Silent but deadly

Movie bugs go back to the first years of cinema, when producers were no less worried about media piracy than they are today. Between 1895 and 1915, films circulated very freely around the world, and enterprising crooks happily duped originals and passed them off as their own productions. To block this, filmmakers tried to find ways to keep their trademarks on the film.

The obvious step was to put the trademark in the intertitles, and many companies did. Here is one for For His Son, a 1912 Griffith film from American Biograph. (What did the protagonist do for his son? He created a soft drink called Dopocoke, which turns the college boy into a hopeless addict.) Note the handsome AB insignia.

But of course a pirate could simply replace such original titles with ones of his own. The next logical step was to incorporate the trademark into the images, which couldn’t be replaced. Without the technology to create near-invisible superimpositions, the filmmakers took the obvious course.

They put the company logo into the set.

The AB circle typically appeared as a wall decoration. Biograph characters loved to furnish their surroundings to highlight this motif, preferring to put it at eye level and frame center. The logo could be found in unexpected places, like movie theatres (Those Awful Hats, 1908), and it could brighten the dreariest hovel (What Shall We Do with Our Old?, 1911).

The plaque’s popularity stretched back to Civil War days (In the Border States, 1910), and even in medieval times a king might mount the stylish AB on a brick wall (The Sealed Room, 1909).

Not to be outdone, Biograph’s competitor, the Vitagraph company, had a beautiful soaring eagle logo, which conveniently furnished a striking V graphic.

Judging from the evidence of this 1908 film, however, Vitagraph had a sideline in manufacturing safes.

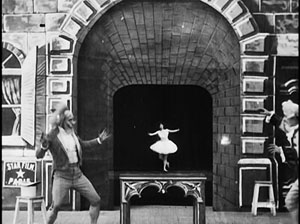

The practice of building the trademark into the mise-en-scene seems to have begun in France. Georges Méliès, whose fantasy films were popular around the world, took measures to counter piracy early. You can see his Star-Film logo on the building stone in the left corner of this frame from La Danseuse microscopique (1902). Shift it to the right corner and we’d have a modern-day bug.

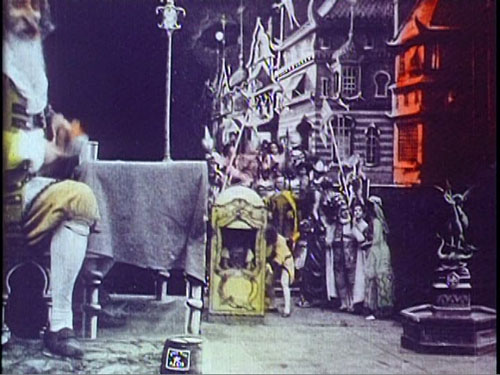

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

But Méliès didn’t always shove his imprimatur to the edge of the frame. In Le Tonnerre de Jupiter (1903) it sits just below the eagle that Zeus bestrides.

In the earlier Diable au convent (1899), Méliès exercised another option, simply signing his image as if it were a painting. To a large extent, it was.

Léon Gaumont had two marques, each enclosed in a chrysanthemum ring. The most famous one is a majestic Gaumont, but an alternative, ELGE (that is, LG), haunts Alice Guy’s Billet de banque (1907). First, in a café, the logo is attached to a table, and later it’s a decorative baseboard in a police station.

In Guy’s Le Frotteur (1907), Gaumont simiply stuck its logo to a chair leg.

Then there’s the Pathé Frères rooster.

Easy enough to embed that, you’d think. Just have a rooster stroll through a shot now and then—not only barnyard scenes, but ones set in a courtroom or a factory. Still, roosters are pretty accessible to any film pirate, so Pathé went the more ordinary route of weaving its logo into the set.

An insistent example comes in The Physician of the Castle (1907), possibly the source for Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1908) and Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s Suspense (1913). The plot is sort of a 1907 Panic Room. The logo is initially a plaque in the parlor of the castle, visible just behind the kneeling doctor.

An identical plaque is perched in nearly the same spot on the wall of the doctor’s own parlor, as we can tell when his family is besieged by the invading tramps.

The tramps pass through another room, where the trademark stands proudly on another wall, on screen right.

And when the wife tries to phone the husband for help, we get an insert that shows the Pathé cock nearly perched on her shoulder.

Why do I find the old bugs charming and the new ones annoying? I suppose it’s partly because the old ones were hand-crafted, not the result of keyboard twiddling. They are tangible. They are part of the scene’s space. Hard to see on DVD, the embedded marques are striking in 35mm projection, and spotting them is part of the pleasure of early film. Moreover, the filmmakers intended them to be there, or at least they accepted the need for them. But what director today is happy when the Sundance bug creeps into her compositions?

The old bugs seem to have gone extinct around 1912, but they will cling to their films. They bear witness to filmmaking of a specific time, and they anticipate problems that persist today. In tackling the threat of piracy, the old bugs seem at once naïve and intelligent. I see them as a rational solution to a hard problem, narrative consistency be damned. Today’s bugs, floating on top of the story world, seem more like corporate tattoos or graffiti. They don’t exist within the action, so you could argue that they are less disruptive. But they become a different sort of distraction, hovering halfway between the story world and the space of viewing. Bugs are spectres haunting the film.

On rare occasions, a modern add-on can be appropriate. In a Méliès film on the recent Flicker Alley set, L’Oracle de Delphes (1903), some TV agency has clapped its own digital bug into the lower right corner. It really is about beetle-size, and it dares to be a single eye looking back at you. That icon adds a touch of peculiarity not out of keeping with the Méliès aesthetic.

You can argue that this smirch on the image is a minor sacrilege. But I suspect that the Master of Montreuil would have grinned in approval.

For more on bugs, aka DOGS (Digital Onscreen Graphics), see Wikipedia. Thanks to Jason Mittell for helping me name these pests. And all hail Turner Classic Movies for keeping its bugs to a minimum.

The Sunbeam (Griffith, American Biograph, 1912).

PS 19 January 2009: “Subliminal” bugs: I had hoped to include a frame illustrating the anti-piracy stamp used on current 35mm releases, but couldn’t find one quickly. This mark consists of a tight pattern of dots resembling a character in Braille. The stamp would presumably be copied if someone shot off the screen or ran the film through a telecine. How effective these bugs are at tracing pirate copies I can’t say, but you can detect them, especially in bright scenes; I usually notice one every third reel or so, just left of the center of the frame. I’ll keep looking for a frame and try to add one to this entry.

John Powers alerted me to the fact that even Michael Snow’s Région Centrale got the bug treatment when it was telecast on Italy’s RAI 3 TV. Thanks to John for this scary example.

P.P.S. 24 January 2009: On the Internets, ask and ye shall receive. Olli Sulopuisto wrote to link me to the Wikipedia entry explaining the domino dots, known as CAPs. The entry includes an illustration. Olli also contributed to Jim Emerson‘s scanners blog, which contains good commentary on CAPs from Jim and his readers.

P.P.P.S. 29 May 2013: Can anti-piracy bugs be integrated into the movie or TV show? Yes!