Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

Class of 1960

DB here:

By now most people accept the idea that 1939 was a kind of Golden Year of cinema. You know, Rules of the Game, Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, that movie about the Civil War, etc. TCM has even made a movie about 1939. On this site Kristin and I have talked about earlier wonder years, like 1913 and 1917. So in planning this year’s Bruges week-long Zomerfilmcollege (aka Cinephile Summer Camp), Stef Franck and I discussed building my lectures around a single year. I proposed 1941, but he countered with 1960.

1960 was a logical choice in providing spread for the whole program. At Bruges we intertwine several threads of lectures and screenings, and this year we had silent films (The Cat and the Canary, The Wind), Hollywood’s cinema of emigration (Florey, Siodmak, Ophuls, etc.), and contemporary Korean film. All in 35mm, of course. So picking 1960 filled in another area.

As so often happens, a contingent choice came to seem a necessary one. By the time I opened my mouth to introduce The Bad Sleep Well, I had convinced myself that 1960 was another watershed year. Consider these releases:

Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti), La Dolce Vita (Fellini), L’Avventura (Antonioni), Le Testament d’Orphée (Cocteau), Plein Soleil (Clement), À bout de souffle (Godard), Les Bonnes femmes (Chabrol), La Verité (Clouzot), The Bridge (Wicki), Wild Strawberries (Bergman), The Devil’s Eye (Bergman), Lady with the Little Dog (Heifetz), The Letter that Wasn’t Sent (Kalatozov), The Steamroller and the Violin (Tarkovsky short), The Teutonic Knights (Alexander Ford), Innocent Sorcerors (Wajda), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Reisz), Tunes of Glory (Neame), Sergeant Rutledge (John Ford), Psycho (Hitchcock), Spartacus (Kubrick), Elmer Gantry (Brooks), 101 Dalmatians (Disney/ Reitherman), The Magnificent Seven (Sturges), Exodus (Preminger), Home from the Hill (Minnelli), Comanche Station (Boetticher), Verboten! (Fuller), The Bellboy (Lewis), The Young One (Buñuel), TheYoung Ones (Alcoriza), The Shadow of the Caudillo (Bracho), Devi (Ray), The Cloud-Capped Star (Ghatak), This Country Where the Ganges Flows (Karmakar), Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin), The Back Door (Li Han-hsiang), Enchanting Shadow (Li Han-hsiang), The Wild, Wild Rose (Wang Tian-lin), Desperado Outpost (Okamoto), Spring Dreams (Kinoshita), When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Naruse), Daughter, Wives, and Mother (Naruse), Cruel Story of Youth (Oshima), The Sun’s Burial (Oshima), Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima), The Island (Shindo), Pigs and Battleships (Imamura), Sleep of the Beast (Suzuki), and Fighting Delinquents (Suzuki).

We didn’t show any of them.

Several factors constrained our choices, including the availability of good prints with Dutch subtitles, or at least English ones. We also didn’t want to run too many official classics. And we fudged a little for pedagogy’s sake. We had to include a Godard, but instead of À bout de souffle, we picked Le Petit soldat—made in 1960 but not released until 1963. The World of Apu was released in 1959 in India, though it made its world impact in the following year. Lola was finished in 1960 but released in early 1961. A dodge, but I wanted a Nouvelle Vague counterpoint to Godard, and it fit well with the Ophuls thread, and—well, it’s Demy. In any case, we wound up with a list of outstanding movies.

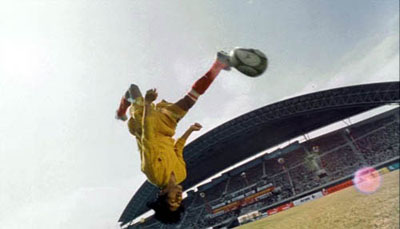

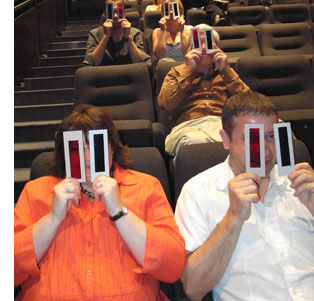

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

All in all, quite a week. My sessions ran from 9:00 AM to 12:30 or 1:00 PM, with the film embedded. After lunch, there were more talks and screenings, usually winding up at about 1:00 AM. Other speakers included Kevin Brownlow, Tom Paulus, Steven Jacobs, Muriel Andrin, Egbert Barten, and Christophe Verbiest (linking his talks on contemporary Korean film to the absolutely nuts 1960 Kim Ki-yong melodrama The Maid). The locals’ lectures were in Dutch, but these worthies are fluent in English, so sharing meals with them allowed me to catch up with their ideas.

Pegging a batch of movies to a single year can seem gimmicky, so I treated the films as exemplifying different trends, many of which started before 1960 and have continued since. I concentrated on trends within world film culture, though in several cases those were tied to still broader social and political developments. Above all, the 1960 frame allowed me to do the sort of comparative work I enjoy.

Generations

My first grouping was “Twilight of the Masters.” This allowed me to develop the idea that, remarkably, people who had started making films in the 1910s and 1920s were still active in the 1960s—and often making films that recalled their youthful efforts. Renoir revisited La Grande illusion in The Elusive Corporal, and Dreyer returned to his origins in tableau cinema through the staging of Gertrud.

In this connection, Fritz Lang’s 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, his final movie, revisits his Mabuse cycle in the way his previous films for Artur Brauner revise the “sensation-films” he wrote for Joe May (especially The Indian Tomb). Drawing on some ideas in my online essay, “The Hook,” we studied Lang’s crisp transitions between scenes. From this angle, 1000 Eyes is a sort of encyclopedia of ways you can connect scenes (visual link, auditory link, association of ideas, etc.). The transitions whip up a breathless pace and steer past some plot holes, and sometimes they generate a level of mistrust, implying story possibilities that don’t turn out to be valid.

Testament’s motif of eyes and vision became expanded to television surveillance in 1000 Eyes. There might even be an oblique connection between the Hotel Luxor’s panopticon and the rise of television ownership in Europe at the period. Here, as ever, cinema doesn’t have good things to say about TV.

Twilight of another, not quite so old master: Late Autumn by Ozu. I reviewed some features of Ozu’s style and then analyzed the film as a multiple-character drama. Ozu and his collaborator Noda Kogo split up the plot in order to present different characters’ attitudes to the central situation: the question of a daughter’s marriage. The plot ingeniously withholds information about the attitude of Akiko, the mother, by deleting certain scenes that would clarify it. Here too, the old master recalls earlier films by having characters discuss their college flirtations, which invoke scenes from Days of Youth and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?

Both Billy Wilder and Akira Kurosawa furnished me with a second generational cohort. I know, probably nobody in his right mind would see common features between these two directors. But desperation can fuel audacity. Both emerged during the late 1930s, began directing in the 1940s, and enjoyed a string of great successes in the 1950s; but both fell on harder times in the 1960s. Both became accusatory living legends, haunting local industries that had kept them from working.

Leading up to The Apartment, I considered Wilder’s contribution to two trends. First, the industry had hit the doldrums. In Europe television and new leisure lifestyles were not yet the threat they would become, but in America, the industry needed to pull its audience away from the TV set and the barbecue. Wilder proved skilful in using Hollywood’s turn to sex as the basis for his cynical comedies. The Lubitsch touch, a worldly appreciation of the oblique approach to matters of sex, was replaced by something harsher. In Wilder’s world, there are mostly sharks and shnooks, those who take and those who are taken.

Second, I situated Wilder as a leading figure in the emergence of the writer-turned-director in the 1940s (Sturges, Huston, Brooks, Fuller, Mankiewicz, etc.). This encouraged me to probe his dramaturgy, and so we analyzed the taut structure of The Apartment’s plot. It has rightly been recognized as a model screenplay, making us sympathize with a careerist covering up his bosses’ infidelities, all the while whetting our interest by shifting the range of knowledge away from the protagonist at key moments. It also displays a nice interweaving of motifs that function both dramatically and metaphorically (especially Miss Kubelik’s hand mirror). Of course at the end I had to run a clip showing the influence of The Apartment on the opening of Jerry Maguire.

By the mid-1960s, however, Wilder was pushing his luck, especially with Kiss Me Stupid. In The Apartment he wanted to make “a movie about fucking,” and he predicted that some day people would do the deed onscreen. But having glimpsed the promised land of the 1970s, he was unable to enter. Despite some worthy efforts, notably The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, he haunted Hollywood as a major director who had outlived his moment.

Human, all too human

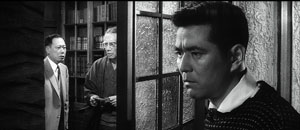

Kurosawa’s international fame came largely through the growth of the film festival as a prime institution of international movie culture. This situation let me sketch in the importance of festivals in bringing directors like him to world recognition. (By the way, Richard Porton has just brought out an informative collection of thoughts on film festivals.) With The Bad Sleep Well, I was able to talk a bit about something that is often forgotten—Kurosawa’s efforts in social, even political cinema. From Sugata Sanshiro, a tribute to Japanese martial arts, and The Most Beautiful, the loveliest movie you’ll ever see about girls making lenses for gunsights, up through Occupation projects like No Regrets for Our Youth and Scandal, Kurosawa engaged with political subject matter. Ikiru and I Live in Fear made this side of his work even more salient in the 1950s.

The Bad Sleep Well’s attack on corporate corruption sits well with this tendency. It considers the “iron triangle” of Japanese politics, the collusion of bureaucrats, politicians, and private industry—particularly the building industry, whose livelihood depends on bids for government projects. Still, it’s hard to believe that while Kurosawa made the film, and while Ozu made the serene Late Autumn, students were fighting police in the streets over the US-Japan security treaty. That turmoil surfaced in Oshima Nagisa’s demanding and formally daring Night and Fog in Japan.

The movie is shot with Kurosawa’s usual muscularity, including virtuoso compositions in what he called, following Toland, “pan-focus.”

The film’s twists also seemed to me worth examining. The protagonist is a minor presence in the first scenes, and his reticence in the beginning is mirrored in the finale, when he simply vanishes and his pal has to tell us what happened to him. Such a daring structure, reminiscent of the abrupt midway break in Ikiru, gives the film an almost Brechtian discomfiture, as well as highlighting the secondary characters’ rather perverse reaction to the hero’s fate.

Kurosawa was widely called a “humanist” director, and this concept sheds light on what we might call the “international film ideology” pervading festivals in the 1950s. In various areas of social and philosophical thought, a notion of humanism emerged out of disillusionment with the “age of ideology” that had engulfed the world in war. Several thinkers declared that the age of religious dogma and social collectivism, either Nazi or Communist, was over. Now what mattered were the features that drew people of all societies together, and the prospect of enlightened social action based on those commonalities—tolerance, respect, and a belief that people ultimately took individual responsibility for their communities. Catholics, Communists, and people of all stripes scrambled to call themselves humanists. As Dwight Macdonald, former Trotskyite, put it, “The root is man.”

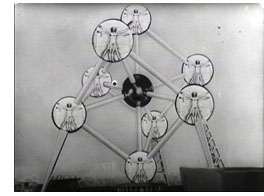

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

Film festivals embraced this universalism, pointing to the great films of Italy’s Neorealist trend as proof of cross-cultural communication. Although these films often scored specifically Italian political points, they could also be seen as human documents speaking to audiences anywhere. Who could not empathize with Ricci and his son in Bicycle Thieves (named at the 1958 Expo as the third-greatest film ever made)?

The turn to humanism helps answer a puzzling question: Why Satyajit Ray? Virtually no Europeans had ever seen a film from India. What enabled a director from this country to achieve worldwide renown? And why not other Indian directors of his era, such as Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak? All of these had to wait many years for discovery by European tastemakers.

For one thing, Ray was highly westernized himself. He was a child of the Bengali Renaissance, a virtuoso in many fields (he composed music, drew with facility, wrote detective stories and children’s books), and an admirer of European cinema. A stint assisting Jean Renoir exposed him to one of the greatest of Western filmmakers. A viewing of The Bicycle Thieves determined him to make films. He was skeptical of imitating Hollywood, which had been a prime inspiration for Hindu cinema. He criticized Bollywood’s reliance on schematic romance and musical numbers. If any Indian director was to make the move to the festival circuit, it would be him. (You can argue that other non-European filmmakers who made it into the fold were the most “western”—Kurosawa, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, etc.).

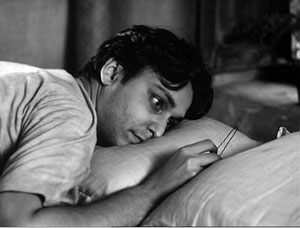

Just as important, Ray’s stories suited the humanist program. Whereas Ghatak and Sen made politically charged films, Ray concentrated on the individual. In The World of Apu, social conditions are shown, but as a background to the development of personality and psychological tensions. At the film’s start, students are holding a street march demanding political rights, but they are offscreen, a backdrop to Apu’s meeting with his old professor as he gets his letter of recommendation. What follows is a drama of artistic failure, blossoming love, and a young man’s confused growth to maturity and responsibility.

It’s a simple story, rendered lyrical through constantly developing imagery: Apu stretched out prone, the famous grimy window curtain, and a cluster of visual motifs I hadn’t noticed on previous viewing. Ray’s concise direction links the torn curtain in Apu’s room to the famous (Langian?) transition from a movie screen to a carriage window, the cluster unified by associating Apurna with male children. Thanks to Andrew Robinson’s book on Ray, we know that in the carriage scene she is already thinking of the son she will bear.

It’s easy to romanticize this handsome, happy-go-lucky hero. I think the College participants thought I was a little hard on Apu, since I treated him as far from the “conscientious and diligent” young man his professor wrote of. Surely his idealistic-novelist persona is sympathetic. But if he is to grow as the film suggests, he must have failings, and Ray shows them to us—dreamy indolence, self-centeredness, even poutiness. The film is a character study, a sort of Bildungsroman tracing how Apu learns his place in his world. Our discussion after this film was particularly rich, with one participant suggesting that in accepting his son he isn’t abandoning his art entirely, but giving it human significance: He promises to tell Kajal stories.

Ray came to directing in middle age, a somewhat rare option. So too did Gillo Pontecorvo, but the latter made many fewer films. Although Kapò, isn’t as strong a movie as our other entries, it did allow us to talk a bit about coproduction, about European cinema’s relation to World War II, and about what came to be known as the morality of technique.

European coproductions are another fundamental part of the 1960 landscape, and they illustrate how economic considerations penetrate artistic choices. (Why are American and Italian actors in the “German” film 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse? Why do we find Anouk Aimée in 8 ½ and Jeanne Moreau in La Notte? Follow the money.) For the Italian production Kapò, the primary roles are taken by an American (Susan Strasberg, playing the heroine Edith) and two French actors—the concentration camp translator played by Emmanuelle Riva and the heroic Soviet soldier played by Laurent Terzieff. The film was shot in Yugoslavia.

The story centers on a young Jewish girl who, in order to survive Nazi internment, passes herself off as a Gentile and becomes a camp commandant, whipping other prisoners into line. Other Italian films of the period, notably Rossellini’s Generale Della Rovere, were dealing with issues of conscience during the war, but Kapò was apparently the first fictional feature in Western Europe to confront the Holocaust since Alessandrini’s Wandering Jew of 1947. In 1960, Adolf Eichmann had been captured by the Mossod and stood trial the following year, and after Kapò came a few other films addressing the camps, notably Wajda’s Samson (1961) and Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1965). So the film had a strong contemporary resonance; after its US release, it would be nominated for an Oscar.

One reason Stef and I picked Kapò was the controversy around Jacques Rivette’s accusation in Cahiers du cinéma that for a particular tracking shot Pontecorvo deserved “the most profound contempt.” The film, as Rivette indicates, is dominated by an already compromised conception of realism: grimed faces, make-up that hollows cheeks, somewhat ragged clothes, moderately shabby bunks. The shot shows the body of Theresa hurled against the electrified barbed wire, with the camera coasting slowly toward it. Her silhouette is almost classically composed, with the hands artfully pivoted and standing out against the sky. For Rivette this pictorial conceit is virtually obscene.

It seems to me that Rivette’s essay sought in part to reply to those who thought that Cahiers’ policy amounted to pure formalism. In calling for an ethics of technique, Rivette argues that artistic choices which might seem to be in the service of correct politics can betray a deeper immorality: using a historical cataclysm as an occasion for a safe realism and self-congratulatory flourishes. Similar complaints could be lodged against Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg and Stone’s World Trade Center. And because for the Cahiers team artistic cinema was an expression of a creator’s vision, the morally maladroit traveling shot brands the director as a man of bad faith.

Rivette isn’t saying that film artists shouldn’t try to represent historical trauma. He simply argues that other paths could be taken. For instance, Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour acknowledge that some events cannot be encompassed by normal understanding, and the form of each film enacts an effort to understand, not a fixed conclusion. What we see in Night and Fog is “a lucid consciousness, somewhat impersonal, that is unable to accept or understand or admit this phenomenon.” For Rivette, Pontecorvo seems convinced that romantic love and self-sacrifice can overcome Nazism, albeit with some help from the Red Army. He tries to explain, even prettify, an event that cannot be understood within the usual humanistic categories.

New Wave, still new

Lola.

Godard’s Le Petit soldat is far more preoccupied with uncertainties, even confusions, than Kapò is. 1960 saw an extraordinary number of former colonies, especially in Africa, gain independence, and during that year the Algerian war of resistance was spreading to Europe. Godard’s central character Bruno is working with the OAS vigilantes dedicated to killing Algerian terrorists, but when he meets the lovely Veronica Dreyer he decides to leave politics behind and flee with her to Brazil. Perhaps “decides” is the wrong word, since his actions are impulsive: he abruptly shies away from committing a political assassination, and he abruptly abandons his colleagues. But he’s captured by FLN terrorists and, in the film’s most famous sequences, tortured. At the end, he commits the assassination, not knowing that Veronica, herself in league with the Algerians, has been captured by his pals and killed. But his final voice-over is almost a shrug, and his act of murder takes on the flavor of an existentialist acte gratuite.

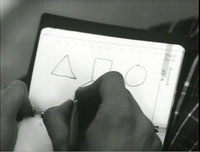

Le Petit soldat doesn’t offer heroic figures, as Kapò does in Theresa and the Soviet soldier. Nor does it allow us to sympathize much with the egotistical, capricious Bruno. The texture is more disjunctive, littered with the usual digressions and citations. Since the film was shot in Geneva, there’s a persistent motif of Swissness, with citations of Paul Klee. A sneaky one I never noticed before: the seduction game Bruno plays is modeled on the three fundamental shapes in the Bauhaus basic course, which Klee taught.

Having experimented with discontinuous imagery in À bout de souffle, Godard in his second feature turns his attention to the soundtrack, creating one of the most minimalist ones I know. If Bresson whittles down his soundtrack to a spare but recognizable realism, Le Petit soldat goes a step further, scrubbing out nearly every noise until we’re almost watching a silent film. Traffic scenes lack traffic noises, with only a car horn or a bit of dialogue breaking in. One passage on a train could almost be a sound loop.

The strategy of suppressed sound is carried to a paroxysm in the torture scenes, with the clink of handcuffs and the soft tapping of typewriter keys highlighted and bits of music played spasmodically…but no sounds of pain. Only during the rushed and almost throwaway climax, is something like a plausible city ambience heard. In a dichotomy that will be familiar throughout Godard’s work, there’s a split between image (Bruno is a photographer, and in the early part of the film he takes snapshots of Veronica in her apartment) and sound (the political factions rely on telephones and tape recorders, and the OAS thugs trick their way into Veronica’s apartment through sound recording).

In all, Le Petit soldat isn’t exactly fun but it’s exhilarating in its bursts and unexpected frictions. Next time somebody tells me that Godard’s technical innovations have all become commonplace, I’ll point to this film of 1960, which would be daring and demanding if released tomorrow.

Fun, albeit grave, is what Lola is all about. It takes formal artifice far beyond realism, creating a sort of non-musical musical. (It has one number, and even that is a sketchy rehearsal.) As geometrical as a minuet, its plot plays out in a hall of mirrors, where characters share names, pasts, and sentiments. The sailor Frankie and the wandering Michel, both in love with Lola, are blonde giants. Lola is actually named Cécile, and the little girl of the same name seems in some ways an early version of her, while Cécile’s mother has a dash of Lola in her past.

Roland starts out as the protagonist, but as he warms and cools and warms to Lola, the story momentum shifts to others. There’s Lola of course, and young Cécile who strikes up a friendship with Frankie, and Cécile’s mother who yearns a bit for Roland, and Michel, who left Nantes years ago and has lived in another movie, specifically, Mark Robson’s Return to Paradise (1952). Here the structure of the plot unfolds the network of relationships among people, linked mostly by casual encounters across a few days. The last section accordingly consists of a series of farewells, as if the story can end only by breaking ties of affection.

In surveying these films, I was struck by how much most of them owed to the growth of postwar institutions of film culture, and how strong those institutions remain. Coproductions and subsidies were feeding a massive buildup of European cinema. Contrary to what you might expect, as attendance cratered from the late 1950s onward, the number of European films produced went up. The EU countries still overproduce, releasing nearly 1200 theatrical features in 2008.

Film festivals were promoting not only universal humanism; they were also packaging films under rubrics of authorship or the New XXX Cinema and the Young ZZZ Cinema. 1940s Neorealism, aka “New Realism in Italian Cinema,” seems to have been, once more, the prototype. Festivals must make discoveries and emphasize novelties. At the same period film schools taught professional standards, and film archives showed classics and gave postwar filmmakers a more secure sense of the medium’s history. Lang, Ozu, and Wilder weren’t dependent on such institutions, but younger filmmakers were. And still are.

1960 is an arbitrary data point, but it stands out as an extraordinary year for quality. In addition, picking it as a benchmark allowed me to think about some important trends of the period. What probably didn’t show through my lumbering PowerPoints, with their charts, diagrams, and frame enlargements, was how much I learned from my Bruges stay. One of the deep satisfactions of teaching is remembering, no matter how confidently you declare your claims, how much more there is to know. Of things cinematic there is no end.

We also asked participants to read Serge Daney’s essay, “The Tracking Shot in Kapò.” Daney’s elaborate exercise in autobiography, irony, and moral reflection could not be plumbed in the time at my disposal, there or here. But it did help me understand Rivette’s argument. In preparing my lectures, I also owed a debt to some excellent books, notably Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity; Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye; Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism; and Richard Brody, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. As ever, the invaluable documentation provided by the print editions of Screen Digest over the years enabled me to compile my tables of attendance, releases, and the like.

Late Autumn.

P.S. 3 Aug: Stef has posted snapshots from our Zomerfilmcollege here.

P.P.S. 3 Aug: This helpful correction from Roland-François Lack on Le Petit Soldat:

One small point: the organisation Bruno works for cannot be the O.A.S., which wasn’t active until the end of 1960.

He is working, rather, for ‘La main rouge’, a government sponsored counter-terrorist agency run by a Colonel Mercier (hence the name of Bruno’s associate).

Nice! Thanks.

Cinema in the world’s happiest place

Bust of Carl Theodor Dreyer in the Dagmar Bio, the film theatre he once managed.

DB here:

Denmark was the first foreign country I ever visited. Having never been to Canada or Mexico, I took off in the early summer of 1970. Technically, I touched down in Reykjavik first because I was flying Icelandic Airlines, the Ryanair of its day. You flew Icelandic to get to Europe as cheaply as possible. Although a few people got off at Reykjavik, most of us sat patiently on the tarmac before heading off to Copenhagen.

Ever since that summer, when blinding light invaded my basement room at 4:00 AM, I’ve had a soft spot for Denmark. Ib Monty, then head of the Danish Film Archive, kindly screened for me all the Dreyers I hadn’t seen, and in spare moments I learned the joys of Copenhagen’s canals and restaurants. Six years later I would spend nearly another whole summer there watching the same Dreyer films on a flatbed viewer in the archive vaults, a somewhat renovated army fort. Many visits later, including a couple to the charming city of Aarhus, I’m still a fan of the Danes. They manage to be modest yet accomplished, hard-working yet hard-partying. They put cultural figures like composer Carl Nielsen on their currency. We’re told that they are the happiest people in the world. I don’t doubt it.

So it was with special pleasure that I returned to Copenhagen for two weeks in June. The second week was consumed by a day of talks and seminars at the University of Copenhagen and then by the convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I’ve given two long-winded previews of the latter event, and I hope to have more coverage of it in a later entry. Today, a smorgasbord of other things Danish–without, alas, mention of H. C. Andersen, Vilhelm Hammershøi, or Victor Borge.

Chaos reigns, more or less

The organizers of our SCSMI event pulled off a coup: Not only were we shown Antichrist in Asta, one of the Danish Film Institute‘s fine theatres, but along came Lars von Trier to spend an hour talking about it afterward.

The film struck me as mid-level von Trier, not as good as The Idiots, The Kingdom, Dancer in the Dark, and The Boss of It All (though others would call me out for admiring this last). It lacks the element of game-playing that I enjoy in what von Trier calls his “mathematical” works, most famously The Five Obstructions. Instead, Antichrist provides perhaps the most unadulterated surge of emotion and mystical/ mythical implication to be found in all his work. It tries to be an intellectual horror film somewhat in the David Lynch mode, with a plaintive, roiling soundtrack and unearthly visions, including a fox snarling, “Chaos reigns!”

I was surprised that the elements so sensationalized by the press are pretty brief; snip out four brief shots and you’d have a ferocious but much less controversial movie. It starts as your basic two-handed psychodrama, with a couple tearing at each other. As in those other duologues Strindberg’s The Stronger and Bergman’s Persona, the film presents a fluctuating power struggle–the man trying to rule through cool rationality, the woman tapping depths of grief and repressed anger.

Yet the film goes beyond psychodrama into realms of history and myth. The grieving mother rises into demonic fury by getting in touch with witchcraft, the subject of her unfinished university thesis. Antichrist could thus be read as an exercise in misogyny or as a celebration of woman’s primal energies. (For what it’s worth, several women in our audience said they liked the film a lot.) Of course the whole thing looks very fine, with a stylized black-and-white prologue (some shots taken at 1000 frames per second), and the rest rendered in that dodging, wandering camera style von Trier and the brilliant cinematographer Antony Dod Mantle have made their own.

The entire Q & A with von Trier, moderated by Peter Schepelern, is available as an audio file on the SCSMI conference website, perhaps to be followed by a video record. Some excerpts:

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

The Antichrist project seems to have brought out a mystical side of von Trier that hasn’t been so prominent in his public image. Years ago he conceived a film in which Satan created the earth, but that dissolved. Certain elements of the film, especially the emblematic forest creatures–blackbird, deer, and fox–come from his interest in shamanism. He has, he claims, traveled in alternative worlds with animal guides. “Never trust the first fox you meet.”

Is it a horror film? At least it has sources in the genre. Uncharacteristically, von Trier prepared for the project by revisiting not only classic horror films he admired, The Exorcist, The Shining, and Carrie, but also The Ring and Dark Water. He was particularly influenced in his youth by Altered States, another venture into “fantasy travels.”

He commented on how his free-camera technique imposed certain constraints in sound work. If you execute a “time cut”–that is, cutting directly to a new scene starting on a shot of a character–you must alter the sound somehow; otherwise the audience is likely to think that the action is continuous. This got me thinking about how The Boss of It All violated that convention, when each continuity cut actually yields a different sound ambience because each of the many cameras is miked separately.

Why is the film dedicated to Tarkovsky? “It was a way of getting rid of psychology.”

“I do not work with the audience in mind. I make films I would like to see myself.”

The Last is not least

Last Friday night the filmmaking program at the University of Copenhagen gave out its student film awards. The crowd was large and boisterous, the atmosphere festive and tipsy. I was honored to present the prize for the best fiction film, which went to desidst (punning on De sidst, “The Last”). The three winning filmmakers, pictured above, were Sissel Marie tonn-Petersen, Niels Holst-Jensen, and Toke Westmark Steensen.

Before I read the result, though, I was confronted with some damaging evidence in a copy of Film History: An Introduction.

Peaking in the 1910s

During my first week in Copenhagen, I was viewing Danish films from 1911 to 1915. As long-time readers of this blog know, I’m fascinated by the films of the 1910s, and Denmark boasts some of the most sophisticated works of the time. Thomas Christensen and Mikael Brae of the Danish Film Archive kindly let me watch several films, mostly from the once-mighty Nordisk film company.

The most remarkable films I saw were Ekspeditricen (1911), Dyrekøbt Aere (“Hard-Won Honor,” 1911), and Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (“Under the Beam of the Lighthouse,” 1913). All three of these offer sophisticated examples of the dominant storytelling technique of that period, what has been called the tableau style.

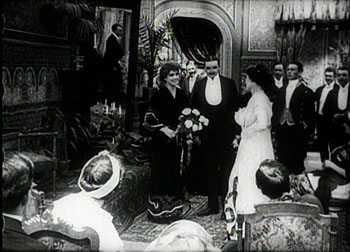

I can’t offer any visual analyses here, as I don’t have frame stills available in digital form, but here’s an example of the kind of thing I’m studying, taken from August Blom’s The Ballet Dancer (1911). Camilla (Asta Nielsen) has been seduced by Jean, a man-about-town, and she has come to sing for a society soirée at which Jean is present. But Jean is also carrying on an affair with the host’s wife.

The scene starts with the host Simon walking with his wife to the middle of the salon. Note the mirror in the upper area of the frame, just left of center.

She goes out frame right, and the host welcomes Camilla, bringing her to the central zone of the shot.

The hostess returns from off right to greet Camilla. Now we can see Camilla’s lover Jean in the mirror.

The hostess leaves the frame again, her husband settles into a chair, and Camilla starts to sing. But in the mirror we can see Jean bending over to kiss the hostess.

Soon Camilla notices Jean’s flirtation, and he straightens up.

Camilla interrupts her song, shouting and thrusting an accusing finger at the couple across the room.

I especially like the way in which Camilla’s finger points both at the offscreen couple and directly at her guilty lover’s reflection. If we haven’t noticed Jean’s infidelity yet, we certainly should now.

Today the same scene would be handled with lots of cutting and point-of-view framings, but the mirror allows Blom to pack a single long shot with simultaneous actions. (Mirrors were something of a signature device in Danish films of the period.) It’s a nice example of Charles Barr’s notion of gradation of emphasis, a principle that was at the heart of the intricate, sometimes exquisite ensemble staging we find so often in the 1910s.

Far from being a static, “theatrical” rendering of the action, the tableau technique looks forward to the deep-space stagings we associate with Welles and Wyler, as well as the distant long-take style of Theo Angelopoulos and Hou Hsiao-hsien. Studying film history is often our best way to understand the cinema of our moment, and perhaps of our future. At a more primal level, a week of prime examples of the tableau tradition gave me a fine dose of Danish happiness.

For background on the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference this year, try here and here. Earlier blog entries on this site have dealt with other aspects of 1910s cinema: director Yevgenii Bauer, tight staging in De Mille’s Kindling (1915), the emergence of classical film style around 1917, editing in William S. Hart movies, the years 1913 and 1918, and the triumph of Doug Fairbanks. I’ve proposed more complete accounts of 1910s staging strategies, and their impact on film history, in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

An excellent introduction to Danish cinema of this period is Ron Mottram’s 1988 Danish Cinema before Dreyer, a book which deserves to be reissued or put online. You can sample Danish 1910s films at the DFI archive database, where several clips are posted. Try these fragments: København ved nat (1910), Den frelsende Film (1916), and Kaerlighedsvalsen (1920). DVD versions of some 1910s classics, including The Ballet Dancer, can be ordered from the DFI Cinemateket shop; in the US, the titles are available for institutional purchase from Gartenberg Media. Everyone interested in silent cinema should own the Dreyer, Christensen, Psilander, and Asta Nielsen discs.

Rights to revert to author

In the Mood for Love.

DB here:

“They never tell you that.”

My neighbor Jim Cortada is a polymath. He joined IBM in the 1970s, when history Ph.D.s faced bleak prospects for academic jobs. Since then Jim has done everything from selling mainframes to leading seminars on quality management. As a business guru, he writes books on management strategy and tactics. He also writes both popular and academic books on the history of information technology. He finds time as well to write books on his grad-school specialty, Spanish diplomatic history.

Jim’s Amazon listing consists of fifty titles. He has worked with publishers as small as Lulu and as big as Oxford. So when he talks about the nuts and bolts of publishing, I listen. His reaction to what happened to me recently is as succinct as it as accurate: They never tell you that. Put into proper context, it’s good for young academics to keep in the back of their minds.

The Syndics speak, after prodding

14 Amazons.

Early this spring, when my royalty statement from Harvard University Press arrived, I noticed an anomaly. From early 2000 through the end of 2007, Planet Hong Kong had sold about 7000 copies. The average, about 800-900 copies a year, isn’t much for trade books, but fairly solid for an academic title. Perhaps courses on Hong Kong film were using it as a text.

But the newest royalty statement brought me up short. In calendar 2008, the sales dropped off the cliff. Harvard shifted only 85 paperback copies and virtually no hardcovers.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

So about six weeks ago I tried contacting my editor at Harvard. Getting no email replies, I left phone messages. No response.

Mossbacks among you will recognize this as a danger sign. When an editor doesn’t reply, it’s not good news. So a call to Harvard’s editorial offices brought the promise of a prompt response. An email from a good-natured staff member there gave me the lowdown: Planet Hong Kong was being taken out of print. There were too many pictures to make a reprint edition worthwhile, someone had decided. Exactly when was that decision made? That matter was left vague, but I was told that the process of transferring rights to me had already begun.

Actually, I was a little surprised at that. Transferring rights back to the author is an old-media custom, but today, when “multiple platforms” are the new business model, there’s no reason for a book to go out of print. Publishers can keep selling a book through print-on-demand or in digital copies. Why Harvard’s decision-makers chose to revert the rights to me remains a bit of a mystery.

In any event, now the 2008 sales slump made sense. Only 85 copies of PHK were sold that year because in all likelihood Harvard, having decided not to reprint, was simply exhausting its stock of copies. On the basis of past performance, those sad 85 copies probably sold fairly early in the year, so there’s reason to think that the decision not to reprint was taken at some point in 2008, perhaps quite early. Yet I wasn’t informed of the decision until I inquired in 2009.

Nor am I complaining that I wasn’t consulted about the decision. Editors and press directors never tip their hand, for the very good reason that the author has no contractual say in the matter. And telling can only cause trouble, because authors have an annoying desire to keep their books in print.

In particular, academics relish prolonged disputation. If you’re told that your book might be headed for landfill, wouldn’t you launch an ambitious plea for reconsideration, complete with references to all the people you know who love the book and reminders that generations yet unborn will be eager to absorb your ideas? (Quotes from favorable reviews optional.) If tension rises, you can always murmur about feeble marketing efforts and a risibly high cover price. It could all get nasty, and the conclusion is foregone anyhow.

So when the publisher is mulling whether to drop your book, don’t expect to have a vote. But once the press has decided to drop it, why the reluctance to tell you?

I’m the one who’s supposed to kill my darlings

Shanghai Blues.

I’ve now had six books go out of print. Correspondence with regard to two of those, back in the 1970s, is lost in the mists of time. Of the four most recent instances, I was told many months after the decision was made, and by the most impersonal of letters—not from my acquisitions editor but from somebody in the cloisters of marketing or production. In the current Planet Hong Kong case, and in an earlier instance, I learned of the book’s fate only because I inquired. Who knows when I would have been told?

Nobody likes to give bad news, and university press staff members are unlikely to be flint-hearted business people. Editors are affable and solicitous; I’ve found them good company. They work long and hard on often fruitless projects: proposals that never turn into manuscripts; manuscripts that can’t get through the vetting process; manuscripts that fall hors de combat in editorial meetings.

And academic writers are almost sadistically inconsiderate. Once professors get their book contract, they behave like their students, trotting out excuses that they laugh about in the faculty pub. They ignore deadlines, word counts, permissions—in sum, everything they signed the contract to honor. Yet these antics are tolerated with remarkably good humor. If university book editors had a taste for blood, they’d be trade book editors. Or agents.

More broadly, it seems to me, university presses are under unique pressures. The good side is that they are a business that can’t go out of business. Even in hard times like these, a university press is unlikely to be shuttered. The blow in prestige and faculty morale would be severe. So most presses limp along. Since most of their costs are bound up in salaries, wages, and benefits, the only area that can feasibly be trimmed is marketing.

Furthermore, and too few young scholars realize this, every press plays a crucial role in the tenuring process. A humanities professor teaching in most universities and many colleges typically needs to publish at least one through-written book to support a case for tenure. There is thus a vast demand that some entity publish said books. The problem is that an academic can deftly write a book that virtually no one wants to read, let alone buy. So university presses are, in effect, subsidizing the tenure process.

Seen from this angle, university publishing is a system of reciprocal altruism. The University of West Overshoe Press publishes Professor Smith’s book on cultural resistance in Girl Scout parade floats. Professor Smith is thereby on his way to tenure at his school, the University of Rising Damp. At the same time, the URD Press publishes Professor Jones’ book on sexual transgression in Futurama. Professor Jones resides at Shattered Tibia State, whose press has just accepted a manuscript (on Wittgenstein’s use of prepositions in the Tractatus) from Professor Johnson. . . who teaches at the University of West Overshoe. I’ve abbreviated the cycle, but you can see that eventually, like the spirochete in Professor Pangloss’s song in Bernstein’s Candide, everything circles around. Any one university press is supporting employment at other universities.

So I’m entirely in sympathy with university presses. And the process, eccentric though it sometimes seems, can produce good books. But presses need to deal more straightforwardly and promptly with writers when a book’s fate has been decided. Jim Cortada is right. They never tell you that. But they should, and pronto. For then you can make plans.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0

Shaolin Soccer.

The lesson for young scholars is simple. Expect that your book will go out of print. Some books will pass over to print-on-demand or digital versions, but it doesn’t hurt to expect the worst. And a book can go out of print surprisingly fast. (The original British edition of my book on Ozu lasted only about two years.) You may learn of your work’s passing by accident, as I did, or through more direct notification, but you should think about your options.

You can simply let it go, accepting the press’s rationale that your book will remain available in libraries around the world for decades. Or you can wait for Google or Amazon to get around to digitizing your work.

Yet an out-of-print book is like a child limping home after a few rough encounters with the world. You might feel duty-bound to take care of it somehow. How?

First step in salvage is to make sure pre-print materials have not been destroyed. Most contracts require that these be returned to you if you regain the rights, but publishers, speedy in so little else, can dump physical production materials in the blink of an eye. In the old days, those materials usually consisted of rolls of thick celluloid, three or four feet wide and very long, on which the pages were printed like panels on a vast comic strip. (Several of these monsters lie pod-like in my basement.) But now most books are stored on computer files, often as PDFs. Copies of those should be returned to you.

Until recently, resuscitating your book came down to trying to find another publisher. I’ve had luck with this tactic only once, with The Cinema of Eisenstein—first published by The Syndics in 1994, yanked out of print in the early 2000s, brought back by Routledge in 2005. Republishing was always rare and is now nearly nonexistent; presses can’t afford to bring out a book that may have saturated its market.

Now, though, there’s another way to revive your sickly child.

For some years I’ve argued that most “tenure books” should be published only in digital form. But university presses have been reluctant to try such an idea, since an online book might not satisfy tenure committees. The best plan would be for some well-respected university press to lock in a vetting process for online publication as rigorous as any for print books. It seems that the University of Michigan Press has begun to do this. Once the model proves its value, and once problems of piracy are solved, the practice could catch on fast. For many books I own, I’d be happy to have PDF files on my computer. There should be big cost savings and, we hope, lower purchase prices—maybe even through selling separate chapters. Like music CDs, many books have only a few chapters you want. We can look forward to the iTune-izing of academic writing.

Yet if university presses need to be cautious about online publishing, the individual scholar doesn’t. The tactic is simple: Plan to put your out-of-print books on the Web.

Some authors may prefer to take existing PDF files or make new ones from the book’s pages, and add a fresh introduction. That’s essentially what Marcus Nornes and his colleagues helped me do with Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. We also tipped in new color images.

The alternative is to revise your book and post a second edition online. It’s a lot of work, but then you could probably charge something for it.

As for Planet Hong Kong, I’m still mulling my next step. Perhaps a publisher will be interested in a new edition, revised, corrected, and updated. Alternatively, I might prepare Planet Hong Kong for downloading on this site. Unlike the original, it could have color illustrations. I have to say that I find this option intriguing.

If you want a used copy of the old edition of PHK, about a dozen are available here. Once dealers learn it’s out of print, they may raise their prices. In any event, I hope to bring the book back in some form. Don’t say I didn’t tell you.

PTU.

Who will watch the movie watchers?

DB here:

Today, I offer more on cognitive film studies, the activities of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, and why both matter. For background, visit the previous post and here and here. Throughout, I’ll harken back to the issue of convergent audience responses: How can viewers from different cultures grasp certain appeals that films provide?

This research tradition seeks to answer questions about moving-image media, especially questions of an artistic nature. The researchers examine filmmaking with the assistance of findings and theoretical frameworks that have emerged in the cognitive sciences of psychology, anthropology, and other disciplines. Some specifics:

Cognitive film studies emphasizes explanations over interpretations. Explanations can be causal (what made this happen) or functional (pointing out the purposes that something fulfills). When human action is part of what we’re studying, the explanations tend to involve goals and motives, means and ends. By contrast, a lot of humanistic media study emphasizes interpreting films but leaves causal and functional processes unexamined.

This research tradition is mentalistic. In explaining viewers’ responses, it looks first to features of the human mind. This doesn’t mean that researchers study minds cut off from society; rather, the emphasis is on the mental activities tied to all sorts of experience, including social action and interaction.

This tradition is naturalistic. The explanations it mounts try to fit in with current understanding of human capacities as analyzed by the social sciences. That entails that psychoanalysis, another mentalistic theory of human action, has not on the whole proven a source of reliable explanations. Some cognitively inclined researchers would add that psychoanalytic inquiry has been fruitful for pointing to areas of behavior that answer to naturalistic investigation.

The line of argument, accordingly, is that of rational inquiry, induction and deduction. It stands in contrast to much current film theory, which consists of more or less free association and the rote citation of major thinkers. Cognitive film theory tries to formulate clear-cut questions and to seek answers that have empirical grounding and conceptual coherence.

The tradition has a strong tendency to look for cross-cultural regularities among artworks and viewer experiences. The sources of these regularities need not be innate in any strong sense. Critics sometimes claim that cognitivists believe that everything is “hard-wired,” but virtually no cognitivists say or believe that. For one thing, our “wiring” changes at certain critical periods, especially two months, nine months, and four years of age. Moreover, the regularities in behavior we notice occurring across cultures or social milieus may have come into existence for many contingent reasons. That doesn’t make them any less interesting as explanatory factors.

For example, no culture is without fibers to bind things, but we shouldn’t expect to find a “string” gene or neuron. In this case, and many others, humans equipped with some common faculties and faced with common demands have found common solutions. We can study shared strategic behaviors without committing ourselves to biological determinism.

People who believe in the cultural construction of nearly everything appeal to learning as the means by which cultural processes shape individual action. Yet cultural constructivists have on the whole been unable to specify how learning is possible. Since an utterly vacant mind could never actively pursue or acquire or organize knowledge, we’re obliged to consider that some innate propensities are in place before humans make contact with the manifold of experience. No one needs to teach a newborn to pick out moving objects or synchronize lip movements with sound patterns.

Moreover, if you rest your case on the metaphor of construction, you need to specify the materials out of which action is built. Up to a point you can say that there are cultural constructions out of other constructions and so on. But the system has to get started somewhere. You have to be able to see color before you can learn that stoplights and stop signs are red. Ingrained capacities and tendencies are the best candidates for being the stuff out of which various cultural conventions are constructed.

Most cognitivists hold to the post-Chomskyan view of learning as the unfolding and refinement of innate predispositions and mental structures. In order to learn something, you need to know something else. In fact, a lot else. It now seems overwhelmingly evident that humans come into the world with many predispositions, some broad and vague, some quite concrete. Some of these are primed in the womb, as with a newborn’s preference for mother’s smell. Other predispositions require only a few confirming encounters to be locked in. A baby is sensitive to a certain range of phonological and prosodic patterns, and so she is ready to fasten on those characteristic of a specific language. Babies seem as well to have an intuitive physics; they are surprised when objects disappear or turn into something else. Babies also are sensitive to eye contact and smiling, both crucial to social interaction and reading others’ intentions.

In sum, the most plausible learning model is that of predispositions, often sometimes quite narrowly constrained, that are confirmed and fine-tuned by the environment (often within a critical period of exposure). We need active engagement with the environment, both physical and social, to let our intrinsic capacities develop to their full strength. Nature via nurture, as Matt Ridley likes to say.

One implication for film is that humans would be likely to recognize film images without extensive training or even a lot of exposure. (Sermin Ildirar found this in the village study mentioned in my previous post). Some understanding of the actions and emotions we see onscreen may have quite specific neural sources, with “mirror neurons” as currently good candidates for grounding recognition and empathy. Other patterns of storytelling and style could be quickly learned, as they piggyback on our understanding of real-world knowledge of social interactions.

Having a battery of predispositions would make sense in evolutionary terms. We gain survival advantage by coming into the world ready to have our biases fine-tuned by experience. Increasingly, for some researchers, the puzzles of cinematic convergence and divergence find their ultimate explanations in human biological and cultural evolution.

Booked

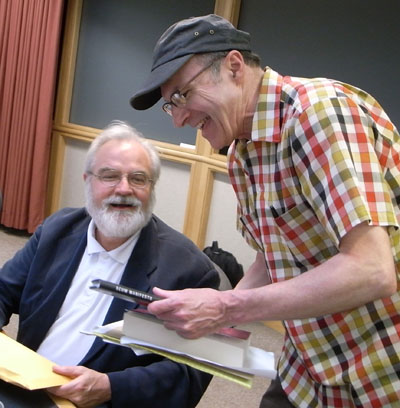

Noël Carroll and JJ Murphy, SCSMI convention June 2008.

I try never to take the present moment as a culmination or turning point in anything. Yet I can’t help noticing that the tenets of cognitive film studies chime in with three wider trends in our current intellectual life.

First, there is a burst of interest in the psychology of informal reasoning. A host of books talks about the shortcuts, heuristics, and predictable errors we make in everyday actions. Examples would be Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson’s Mistakes Were Made, Ori and Rom Brafman’s Sway, Gary Marcus’s Kluge, Jonah Lehrer’s How We Decide, Joseph T. Hallinan’s Why We Make Mistakes, and Dan Zariely’s Predictably Irrational. The flourishing area of behavioral economics, typified by Akerlof and Shiller’s Animal Spirits, is an outgrowth of this line of inquiry. Most of these books explore the cognitive biases that were brought to light by psychologists some time ago, but now emotion is seen as playing a central role.

A second thread in the cultural conversation involves neurology. Now that brain scanning has yielded more precise ways of tracking mental activity, our common-sense actions are seen to have surprising and tangled roots. Many of the books just mentioned draw upon neuroscience to identify the sources of cognitive biases. A rich survey of the neurological territory as currently mapped can be found in Human: The Science Behind What Makes Us Unique, by Michael Gazzaniga.

Then there’s the hottest topic of all, a renewed interest in evolutionary biology. A host of books is rolling out explaining and debating Darwinism. (By the way, Charles, happy centenary.) A good recent example is Jerry Coyne’s Why Evolution Is True. But the interest in evolution has given a new salience to evolutionary psychology, that area of inquiry that investigates how our minds have been shaped and constrained by adaptation and other evolutionary processes.

Evolutionary psychology came to prominence in the social sciences with the 1992 breakthrough book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. There Jerome H. Barkow, Leda Cosmides, and John Tooby flung down a challenge to traditional social science. Most researchers assumed that the mind was plastic and variable to a very large extent, both between cultures and within an individual’s lifetime. Culture held an irresistible sway over mental life. The essays collected in The Adapted Mind, particularly Tooby and Cosmides’ introductory manifesto, suggested that psychologists needed to consider evolution as a powerful source of explanations for mental activity. Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate (2002) brought this line of thinking to a much broader public.

Although many humanists are proud of owing nothing to science, it’s curious that they often share traditional social sciences’ belief in a more or less blank slate. Virtually everything is culturally constructed; any biological givens are written off as nonexistent, unimportant, or uninteresting. But some humanistic scholars are starting to show that such factors possess both interest and explanatory value.

Studies linking art and literature to biological and cultural evolution are enjoying great prominence this year. Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct and Brian Boyd’s On the Origins of Stories have sparked a wide discussion of how the play instinct, mate selection, and other adaptations might shed light on narrative, music, and the visual arts.

Now, when cognitive and evolutionary models are the latest thing in literary studies, to be applauded or denounced by the MLA rank and file, it’s worth remembering that film studies has been plowing this field for quite some time. Some people would say that my Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) opened up this wing of film studies, but although that book drew on current developments in cognitive psychology, it didn’t outline a broad research program.

More far-reaching was Noël Carroll’s “The Power of Movies,” also published in 1985. Carroll’s seminal essay laid out a concise explanation of cultural convergence through cinema, or as he put it, how “movies have engaged the widespread, intense response of untutored audiences throughout the century.” Carroll’s critique of then-current film theory, Mystifying Movies (1985 again), developed the essay’s idea as a counterweight to psychoanalytic and neo-Marxist explanations for the power of popular cinema. The importance of attention, the role of visual techniques in shaping uptake, and the possibility of evolutionary sources for cinema’s appeals—these and other themes of today’s cognitive film research can be found in Carroll’s work of twenty-five years ago. I suppose that “The Power of Movies” is the cognitivist’s equivalent to Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

A turning point?

Joe, Barb, and Amy Anderson; SCSMI convention, June 2008.

Grand Theory in the humanities has prided itself on being cutting edge, yet it has ignored virtually all of the major developments in the human sciences, from Chomskyan linguistics through cognitive science and now evolutionary and neurological research. That ignoral can seem almost wilful. The 1990s saw a flourishing of cognitive film theory, such as Ed Tan’s study of emotion in cinema and Murray Smith’s study of characterization. Yet in 2006, when I was invited to London to give a paper surveying the perspective, I seemed to be speaking Martian. Two of the most distinguished senior film scholars in the UK said they couldn’t really comment adequately. The approach was all so new and unfamiliar!

If I had been haughty enough to offer two veterans of Screen some reading tips, I could have referred them to two compelling overviews. Paul Messaris’s Visual Literacy: Image, Mind, and Reality (1994) synthesized psychological and anthropological research on how people responded to media and concluded that there wasn’t yet any evidence that images and their normal combination were radically coded. Joseph Anderson’s Reality of Illusion (1998) showed how key questions of cinematic perception and comprehension have been addressed by empirical research in the social sciences. Joe and his wife Barbara were also pioneers in bringing evolutionary explanations to bear on cinematic problems, thanks to James J. Gibson’s “ecological” frame of reference.

In just the last year, three of the people deeply involved with SCSMI have published books that push the conversation in fresh directions. Assume that widely distributed propensities, either innate or converging through cross-cultural regularities, get fine-tuned by the specifics of cultural experience. How do these convergences and divergences emerge in films?

The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

On both fronts, the book tries to balance the convergence/ divergence tendencies. Take My Neighbor Totoro.

The film is clearly influenced by its Japanese origin, from the use of Shinto gods to the rice fields and sliding doors. But the fact that children all over the world are fascinated by the film is only loosely related to those cultural specificities. . . . Miyazaki uses a series of devices that tap into innate and universal mental mechanisms and emotions. Central, of course, is the fascination with the soft, organic counterintuitive agent Totoro, who provides attachment security and empowerment for the little girl, Mei, in the absence of the parents.

Torben goes on to discuss how Miyazaki exploits our interest in “counterintuitive” phenomena, like ghosts and gods, in the figure of a cat who is also a bus.

While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga’s Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions, surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga’s Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions, surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

Perhaps more interesting, Carl suggests that while sympathetic narratives evoke compassion and pity, distanced narratives evoke cooler feelings, like respect or disdain. This distinction allows him to deny that the common claim that the aesthetic distance we find in Antonioni or Angelopoulos is unemotional; these artists simply deal in different emotions. The distinction also enables him to puncture the belief that Hollywood offers only sentimental hogwash.

It might be thought that sympathetic narratives are the norm in Hollywood. Yet distanced narrative is pervasive in Hollywood, as it is in the “art” cinema. The distanced mode rejects the evocation of strong sympathy for characters—sympathies that are sometimes dismissed as sentimentality—in favor of a more distanced, critical, sometimes humorous, and occasionally cynical perspective.

Plantinga’s examples are action films like The Hunt for Red October, which evokes admiration for gallant stoicism, ironic comedies like Raising Arizona, and puzzle films like House of Games and The Usual Suspects.

One of Carl’s key points is that sympathetic narratives must evoke some negative emotions, when their characters are hit by misfortune. So melodrama is the sympathetic narrative par excellence. Moving Viewers closes with a sensitive discussion of how a film can orchestrate negative emotions in complicated ways, focusing on disgust as it is evoked in films as different as Mask and Polyester.

A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

Understanding Indian Movies shows how those universal plot structures gain richness and emotional force through their encounter with Indian traditions and current social conditions. For example, the sacrificial plot found in all cultures is particularized in Santosh Sivan’s The Terrorist. The film transforms the standard plot for the sake of ideological point and emotional force, modeling its suicide-bomber tale on the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. “The contemporary history depicted by the film was already emplotted in a prototypical narrative form by the people who made that history.”

Hogan’s book is not as localized in its concerns as the title might imply. It’s not only about how to watch Indian movies but also about how to do cognitive studies of media. For instance, Patrick often pauses to criticize over-simplified evolutionary explanations, and he urges that such explanations be used cautiously. But he nonetheless defends the overall convergence/ divergence perspective.

On the one hand there is particularity—not merely the particularity of national cultures, but the particularity of regions, religions, castes, classes, philosophies, ages, and so forth, all the way down to individuals. On the other hand, there is the common genetic heritage of the human brain, the common principles of childhood development (beyond genetics), the recurring practices that arise from group dynamics—a whole series of universal principles that we all share. . . . Whether we are European, Chinese, African, or Indian, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, or Muslim, it is these universals that make it possible for us to understand Indian movies and to appreciate them, rather than merely drawing abstract inferences about them, as if they were part of some inscrutable puzzle.

The differences among these books are considerable. Grodal wants explanations at the level of neurology. Plantinga, of a philosophical temper, wants to clarify the concepts we use to talk about emotions in our experience of films. Hogan is constantly looking for the political implications of artistic choices. But such a range of emphasis matches the variety of the papers assembled for our next meeting.

The Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image meets next week in Copenhagen. Patrick Hogan, alas, will not be joining us. But Torben Grodal is speaking on “Crime Fiction from a Biocultural Pespective,” and Carl Plantinga is giving a talk called “Models of Real and Hypothetical Spectators.” Once more, a complete list of papers can be downloaded here.

In sum, evidence is mounting that the SCSMI is now the gathering point for a very robust, accessible, and exhilarating approach to thinking about how films work and work upon us—all of us.

Research conducted by SCSMI members is available in The Journal of Moving Image Studies and in Projections.

Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies” can be found in his Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 78-93. He revisited these ideas in the 1996 essay “Film, Attention, and Communication: A Naturalistic Perspective,” available in Engaging the Moving Image (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 10-58. Some SCSMI members will be represented in the forthcoming Evolutionary Approaches to Literature and Film: A Reader in Science and Art (Columbia University Press), edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jon Gottschall. Evolutionary Psychology, by Robin Dunbar, Louise Barrett, and John Lycett provides an excellent survey of several of the ideas I gestured toward today.

Himmelskibet (The Space Ship, aka A Trip to Mars, 1918).