Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

It was a dark and stormy campaign

How do you get people to believe that if you can’t get the press to make an honest assessment of it? You tell a story. “When it came down to a choice between my very life and my country, I chose my country.” That’s why the story’s important. Just as Obama’s story is important to him. I don’t gainsay it. You know, tell your story! —John McCain staff member and co-author Mark Salter

There was a mismatch between the way he was behaving and the narrative the press had bought into. It made reporters wonder, “Have we been had?”–Professor Marion Just, Wellesley, on John McCain

This political bullshit about narratives.–Peggy Noonan, Republican columnist

I’m David Bordwell and I approved this message.

A long time ago a student complained to me that we film academics were foisting upon them words that no professional filmmakers used. The student’s example was “genre.” Today of course filmmakers use the term all the time. Sometimes you hear “classical filmmaking,” and Variety tells us that Henry Jenkins’ label “transmedia” is starting to break through:

Famed s/f writer Larry Niven is working with “transmedia” (today’s new buzzword) production company Alchemic Productions to create a new game property called “Free Fall.”

More broadly, the terminology of Big Theory in the humanities has trickled into journalism and politics. For some time now “deconstruction” has been peppering mass-market discourse. Granted, it’s not employed in the way Derrida and his acolytes would like. It seems to mean a blend of “construction” and “destruction,” which can entail “analysis” or even just “pulling something apart.”

Deconstruct Black Ink: Your children can use chromatography to deconstruct black ink and find out what color the ink really is.

Scientists Deconstruct Clownfish Chatter

U. of Kansas Looks to Deconstruct Its School of Fine Arts

This election season has shown me that even the idea of the Other, considerably divorced from its use by Jacques “The Lack” Lacan, can show up. Nicholas Kristof claims that John McCain’s efforts to suggest that Barack Obama isn’t “sufficiently Christian” are an effort to “otherize” him.

But I think the term that has gotten the most play is “narrative.”

Discovering narrative

During my days as an undergraduate in literary studies and as a grad student in film studies, between 1965 and 1973, you scarcely ever heard the word. It doesn’t appear in the index of Wellek and Warren’s Theory of Literature (3rd ed., 1956) or Wimsatt and Brooks’ Literary Criticism: A Short History (1957) or Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism (1957). Story, tale, plot, dramatic structure: these words were common, but not “narrative”.

In American academia, the term began to gain currency with Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg’s The Nature of Narrative (1966). The authors identify narrative with a broad literary tradition, embodied not only in the novel and short story but also in oral storytelling. And the definition is clearly language-based, in pointed contrast with drama.

By narrative we mean all those literary works which are distinguished by two characteristics: the presence of a story and a story-teller. A drama is a story without a story-teller; in it characters act our directly what Aristotle called an “imitation” of such action as we find in life. (4)

The Nature of Narrative was published the same year that Roland Barthes, in a special issue of the French journal Communications, published his essay “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” (1) His conception of narratives (récits) is far more generous than that of Scholes and Kellogg.

Narrative is first and foremost a prodigious variety of genres, themselves distributed amongst different substances—as though any material were fit to receive man’s stories. Able to be carried by articulated language, spoken or written, fixed or moving images, gestures, and the ordered mixture of all these substances, narrative is present in myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama, comedy, mime, painting (think of Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula), stained glass windows, cinema, comics, news item, conversation. (79)

Barthes’ essay, along with other Structuralist studies, initiated the academic field of “narratology,” the systematic study of storytelling as it is manifested in many media. From the 1970s to the present, this became a vast, varied, and exciting area of inquiry.

The questions are fascinating.

*What is a story? How does it differ from other things, such as a description or an abstract image? Are jokes narratives? Are dreams? Are riddles? Is the concept so broad that anything can be treated as a story?

*Why do stories engage us? What do we need to know, or do, to understand a story? What powers enable us to create stories? Are story-making and story comprehension distinctively human activities?

*Do stories rendered in language differ from those rendered in other media? Is the ability to make or follow stories dependent on our knowing language, even if the story is presented without words (as, say, a silent film)?

*How do narratives imply or suggest or symbolize broader meanings than the bare events they recount? What enables a narrative to stand for more than it seems to say?

*What patterns of narrative construction do we find in different traditions, periods, times, and places? How might they bear the traces of social and political views? How might they express varying conceptions of the world?

In retrospect, we can see that Aristotle, nineteenth-century theorists of the drama, and theorists like Walter Benjamin, Georges Polti, R. S. Crane, and Northrop Frye did reflect on the phenomenon as narratologists were beginning to conceive it. But very few thinkers had asked these particular questions, in quite the way that Barthes and other Structuralists had.

The questions may seem impossibly abstract or broad, but they get more manageable if we look at particular cases. Take film. We all assume that Hollywood movies belong to a storytelling tradition, one that some people consider formulaic. But if Hollywood movies are formulaic, they must adhere to conventions—conventions we might not find, say, in Homer’s epics or Ibsen’s dramas or Neorealist films. What are those narrative conventions? Where did they come from? How do they fit together? What might be their effects on viewers’ beliefs and experiences?

Studying the narrative conventions of various filmmaking traditions has kept Kristin and me busy for many years. We explained some rudiments of narrative theory in the first edition of Film Art (1979); I think that this was the first time an introductory textbook put the area on the film studies agenda. In the 1980s we wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema and Narration in the Fiction Film; in the 1990s Kristin wrote Storytelling in the New Hollywood; in the 2000s I wrote The Way Hollywood Tells It and Poetics of Cinema. Most recently we composed some items on this website (here and here and here).

Now, after a thirty-year pageant of academic theories and analyses, we find that the term has trickled down, so to speak, to bare-knuckle politics. It turns out that the current Presidential election in the U. S. is all about “narratives.” The candidates have them, as do the campaigns. And those narratives are served up in newspaper accounts that are also narratives. How the word gained its new status is a question for another time. For now, we have plenty of tales to occupy the narratologist.

Two quick caveats

Narrative doesn’t equal fiction. Most narratologists have followed Barthes in treating factual accounts, like newspaper stories and conversations, as narratives. Sometimes a filmmaker will say, “I make documentaries, not narratives,” but documentaries can be, and often are, narrative in form. So too are some avant-garde films, such as Meshes of the Afternoon and Tribulation 99. One of the reasons that we study narrative is that it’s a very widespread phenomenon.

This is not to say that the fact/ fiction distinction doesn’t matter. We react differently to narratives purporting to be fictional and ones claiming to be factual. And studying narrative doesn’t commit us to saying that all narratives are fictional (because they’re constructed, or because they’re selective, or whatever). History books and newspaper reports can be more or less faithful to what really happened. And sometimes fact seems more narratively coherent than fiction. If you wrote a novel about an idealistic presidential candidate born in a town called Hope, you’d be accused of heavy-handed symbolism; but tell that to Bill Clinton.

Narrative is a type of representation. What happens to you today isn’t a narrative until you tell somebody about it, or write it up in your diary, or at least sort it out as a story in your mind. A narrative, as the name implies, is a string of events that is narrated—represented in some form. In this sense, the Presidential campaign isn’t a narrative in and of itself. It becomes a narrative when people represent it: select events, omit others, perhaps invent or imagine still others, and present them in words, pictures, music, or some other medium.

This idea of presenting a chain of causally connected events, enacted by agents and unfolding in time, is what we characteristically mean by storytelling. You can find a more abstract definition of narrative in Film Art and other things Kristin and I have written, but this will suffice for now.

The plots thicken

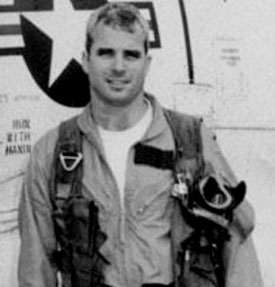

Clearly the presidential candidates have come to believe that what seizes the public aren’t just policy views and promises. Now the campaigns want to tell stories in which the candidates are the protagonists. The life of Barack Obama, or Joe Biden, or Sarah Palin is said to be a story (usually “an American story”). According to Robert Draper’s influential recent article, John McCain’s campaign has deliberately set out a series of “narratives”: McCain endures suffering in Hanoi as a POW; he enters politics and fights for reform in government. Mark Salter, McCain’s staff member and coauthor, has the responsibility of stitching incidents of the Senator’s career into what he calls the “metanarrative” of McCain’s life—rather as George Lucas presides over the Bible of the Star Wars universe.

The campaigns’ efforts at representing narratives don’t just amount to giving us backstory about the protagonists. Things get tricky when they try to present the ongoing campaign as itself a narrative. This involves planning a smooth cascade of events, such as during the party convention, when the suspense builds toward the climax of nomination. The problem of course is that events outside the candidates’ control can force changes in the story line. During the recent financial meltdown, McCain’s campaign would have preferred to create a dialogue about national security, and Obama’s campaign was prepared to talk about the war and the squeeze on the middle class. Instead, each had to respond to swiftly changing events and rewrite the script every day.

Why is the McCain campaign flagging? Contrary to Salter’s intentions, many believe that it never found “a compelling story”—that is, a way to integrate all the events hurled at their ideal scenario. Obama’s story was simpler: he could simply point to each new catastrophe as caused by Republican rule.

Sometimes the mass media replay the narratives concocted by the campaign, but sometimes they offer counter-narratives. A Rolling Stone article sought to replace the official McCain “metanarrative” by adding incidents, characters, and causes that add up to a far more damaging story. More broadly, a common account portrays the campaigns as a study in contrasts: Obama’s enterprise ran steadily according to the well-planned strategy of pursuing votes in nearly every state, while McCain’s campaign was more tactical and reactive, taking red states for granted. And as in any good narrative, the actions are treated as reflecting the traits of the two characters. Obama is seen to be calm and measured, so his campaign runs smoothly; McCain appears splenetic and tightly wound, so his campaign is spasmodic. Character and action are believed to mesh. (More on character traits shortly.)

Once these narrative arcs are in place, they become hard to dislodge. As I write this, unnamed handlers in the McCain campaign are blaming one another and Sarah Palin, and this new string of incidents only seems to confirm the scenario of a rudderless, probably doomed, enterprise. Other observers, and historians in future years may embellish, revise, or reject the mainstream account. My point is that we’ve watched a standard story emerge as a full-bodied narrative, or rather a cluster of them—the way that a folktale or myth presents different variants of emphasis and point of view. Still, each one of the variants is a narrative—a representation of a string of events, enacted by agents and bound together through chronology and causal connections.

What’s your story?

I long ago learned to distrust my childhood and the stories that shaped it. It was only many years later, after I had sat at my father’s grave and spoken to him through Africa’s red soil, that I could circle back and evaluate these early stories for myself. Or, more accurately, it was only then that I understood that I had spent much of my life trying to rewrite these stories, plugging up holes in the narrative, accommodating unwelcome details, projecting individual choices against the blind sweep of history, all in the hope of extracting some granite slab of truth upon which my unborn children can firmly stand.

Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father, xv-xvi

Each of the two top presidential candidates has signed an autobiography that functions, in today’s story-hungry ecosystem, as a bid to control his narrative. In 1995, Obama published Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance; four years later McCain produced Faith of My Fathers: A Family Memoir. In what follows, I’ll refer to the latter as McCain’s book, though apparently coauthor Mark Salter is responsible for both a lot of the research and the actual prose of the result.

Like Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, Obama and McCain are deeply concerned with fathers and how they shape sons. Both books portray three generations of men: the author, his father, and his grandfather. The concern for the father’s role is enacted in the overall design of each narrative.

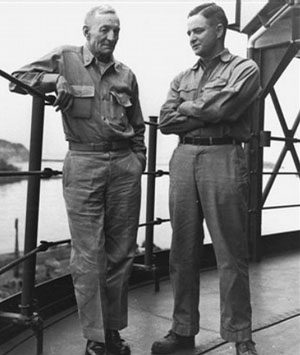

McCain’s book is more straightforwardly chronological, and it proceeds in three layers. After an emblematic moment when his father and grandfather met at the end of World War II (more on this below), the narrative starts with a brief biography of the elder, McCain senior, who served as an admiral under William Halsey during World War II. There follows a somewhat longer account of McCain junior, who also won the rank of Admiral and who commanded naval operations during the Vietnam war. Woven into these accounts are vignettes of the youngest McCain’s reactions to these two awe-inspiring warriors.

The bulk of the book presents his own life, rendered chronologically. He swiftly runs through a “misspent youth” of impulsive rebellion and reluctance to kowtow to authority. McCain expresses gratitude for the family heritage—a sense of duty and, above all, honor—that informed his life. But he did not fully understand the weight of these traditions, he tells us, until he was taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese and was held as a POW for over five years. There, under severe torture and despite the greatest resistance he could muster, he signed a false confession. It was a betrayal not only of his country, but of a family tradition.

They were the worst two weeks of my life. I couldn’t rationalize away my confession. I was ashamed. I felt faithless, and couldn’t control my despair. I shook, as if my disgrace were a fever. I kept imagining that they would release my confession to embarrass my father. All my pride was lost, and I doubted I would ever stand up to any man again. Nothing could save me. No one would ever look upon me again with anything but pity or contempt. . . . The Vietnamese had broken the prisoner they called the “Crown Prince,” and I knew they had done it to hurt the man they believed to be a king. (244-245)

The rest of the narrative tells of redemption. Months of poor medical care, mind-numbing routine, solitary confinement, and spasms of torture had made McCain vulnerable. But in living with other prisoners, McCain discovers that loyalty to country merged with loyalty to comrades and to God. Honor and duty are bound up with faith.

I was no longer the boy to whom liberty meant simply that I could do as I pleased, and who, in my vanity, used my freedom to polish my image as an I-don’t-give-a-damn nonconformist. . . . In prison, where my cherished independence was mocked and assaulted, I found my self-respect in a shared fidelity to my country. All honor comes with obligations. I and the men with whom I served had accepted ours, and we were grateful for the privilege. (255)

By the time he is released, McCain—now living with other prisoners—can help create the bonds that make them resist, and occasionally subvert, their captors’ plans. (Among other things, he enlivens their nightly meetings with long recitations of the plots of movies he has seen.) And he refuses to be released out of the sequence of his capture. At the end, on the verge of freedom, the boyish McCain reemerges, offering some insolent quips to Vietnamese officers. He returns home, not to his father—that conventional scene is oddly absent—but to a greater sense of his responsibility.

McCain has spoken of Viva Zapata! as his favorite film, but in reading the book I couldn’t escape the feeling that it traces, in a less light-hearted tenor than Ford’s film does, the way in which Ensign Pulver becomes Mr. Roberts.

The narrative arc of Dreams from My Father is far less linear in its plot. At bottom, it is a conventional autobiography, telling how a boy born in Hawaii to an American mother and a Kenyan father, wound up going to law school. Unlike McCain, who grew up knowing about the triumphant careers of his father and grandfather, Obama never really knew his father. His parents divorced when he was two, and he saw his father only once, when he was ten. His mother, and then his grandparents, were his family. The narrative is, like McCain’s, presented in three parts, but these correspond to three stages of the protagonist’s life: an early phase of childhood, high school, and college; a period of young manhood spent in Chicago, organizing community groups for social improvement; and a trip to Kenya before entering Harvard.

If McCain’s book is an adventure tale, Obama’s is a detective story. The through-line, as screenwriters might say, is Obama’s search for his identity as a African American. If McCain’s plot is driven by honor and duty, Obama’s depends on race and social responsibility. McCain steers by a fixed star, and is shamed when he goes off course. Obama is scanning the heavens for some stable pole that will give him a sense of who he is.

In Chicago, he is confronted with the poverty and fragmentation of the black community. Some failures and moderate successes in community organizing give his young life a degree of purpose. He learns from Harold Washington and various preachers, surrogate father figures, that there are larger forces working to tear apart the fragile unity citizens might achieve. The chief danger is losing hope. Attending a service by Jeremiah Wright and hearing talk of “the audacity of hope,” Obama has a conversion:

If a part of me continued to feel that this Sunday communion sometimes simplified our condition, that it could sometimes disguise or suppress the very real conflicts among us and would fulfill its promise only through action, I also felt for the first time how that spirit carried within it, nascent, incomplete, the possibility of moving beyond our narrow dreams. (294)

But still his own history feels incomplete, and he sets out to complete it by visiting his father’s tangled family in Kenya. He finds he has many brothers, sisters, aunts, and uncles. He witnesses deep divisions in a squabble over his father’s estate, and he comes to realize how family bonds can be both liberating and stifling. As he explores, he learns more about his father and, eventually, his grandfather.

McCain gives encapsulated judgments of his father and grandfather, while Obama keeps offering partial portraits, images slipping in and out of focus. His father was a noble man, much respected till his death; no, he fell into drunken lassitude; no, even in his decline he was generous and loyal to his friends. Eventually, talking with his grandmother, Obama learns of the history of his father’s family. As in a detective story, the book’s climax is a recitation of what the protagonist had never known, the hidden causes of why his mother and father divorced—and the revelation of a secret his mother and her parents had always kept from him. Like McCain, Obama finds himself, but not through living up to an external code of conduct. By an act of sympathetic imagination, Obama grasps how he continues to live, in his own register, the problems and promise embodied in a man who had abandoned him two decades earlier.

Obama’s tale is more complex than McCain’s, but each one reflects the image of the protagonist. McCain lives in a world of clear-cut demands, called the Code, and so any problem comes from failing to meet the obligations of duty. Obama’s world is hazy and uncertain; there is no Code. How should a man like him, with his heritage, find a way to live with dignity?

Telling details

The differences in the overall narrative progression get embodied in differences at the level of texture, or narration—the concrete way each story is told, moment by moment. Consider the opening of Faith of My Fathers:

I have a picture I prize of my grandfather and father, John Sidney McCain Senor and Junior, taken on the bridge of a submarine tender, the USS Proteus, in Tokyo Bay a few hours after the war had ended. They had just finished meeting privately in one of the ship’s small staterooms and were about to depart for separate destinations. They would never see each other again.

Despite the weariness that lined their faces, you can see they were relieved to be in each other’s company again. My grandfather loved his children. And my father admired my grandfather above all others. My mother, to whom my father was devoted, had once asked him if he loved his father more than he loved her. He replied simply, “Yes, I do.”

And here are the opening lines of Obama’s memoir:

A few months after my twenty-first birthday, a stranger called to give me the news. I was living in New York at the time, on Ninety-fourth between Second and First, part of that unnamed, shifting border between East Harlem and the rest of Manhattan. It was an uninviting block, treeless and barren, lined with soot-colored walk-ups that cast heavy shadows for most of the day. The apartment was small, with slanting floors and irregular heat and a buzzer downstairs that didn’t work, so that visitors had to call ahead from a pay phone at the corner gas station, where a black Doberman the size of a wolf paced through the night in vigilant patrol, its jaws clamped around an empty beer bottle.

A card-carrying narratologist could squeeze a whole article out of these two openings, but just notice how well designed each is. Both grab the reader: Why would McCain’s father and grandfather never meet again? What was “the news” headed for Obama? The short, crisp sentences of the McCain extract—few adjectives and adverbs, no description except for the lines on the men’s faces—set the pace for what we’ll get later. McCain (via Salter) tells his tale in brief paragraphs and unvarnished prose, as laconic as the talk of the seamen he admires. The two opening scenes, that of father and son meeting on the bridge of the Proteus and the moment when McCain’s father tells his wife that he loves his father more than her, might have come from a John Ford film. The climactic “Yes, I do” even enacts that legendary Ford dictum that you shouldn’t let actors talk much.

Obama’s scene is more like a sequence from a 1970s urban movie, yielding washed-out imagery packed with scruffy detail. Everything suggests “dangerous neighborhood” and “black poverty,” but at no point does Obama use any of those words. Instead we get suggestions of grime and bleakness. As in many novels, the milieu comes to life through action: the broken buzzer initiates the routine of people calling ahead. By metonymy, the adjacent gas station reminds the narrator of the almost hallucinatory Doberman trotting through the night. And instead of telling us that drunkards left their beer bottles littering the streets, this paragraph suggests this sorry milieu obliquely by having the patrol dog clenching one in its jaws.

It might be tempting to say that McCain is deliberately avoiding literary grace notes, as befits a man identified with Straight Talk, while Obama is writing in a self-consciously novelistic way, like the elitist he is. Actually, no. Both are writing in literary ways, but using different techniques of narration.

Obama is adhering to Henry James’ admonition to “Dramatize, dramatize!” He tries to make every scene come alive for the reader through small details. He’s the sort of memoirist who not only gives you twenty-year-old conversations word for word, but adds all the gestures, vocal tones, and props.

“See there,” Marcus said. “Makes you embarrassed, don’t it—just being seen with a book like this. I’m telling you, man, this stuff will poison your mind.” He looked at his watch. “Damn, I’m late for class.” He leaned over and pecked Regina on the cheek. “Talk to this brother, will you? I think he can still be saved.”

Regina smiled and shook her head as we watched Marcus stride out the door. “Marcus is in one of his teaching moods, I see.” (103)

This sort of prose is movie-adaptation ready: You can see the scene. McCain doesn’t work at this level of concrete rendition, but his narration is no less carpentered. Consider this passage:

I didn’t think, “Gee, I’m hit—what now?” I reacted automatically the moment I took the hit and saw that my wing was gone. I radioed, “I’m hit,” reached up, and pulled the ejection seat handle.

I struck part of the airplane, breaking my left arm, my right arm in three places, and my right knee, and I was briefly knocked unconscious by the force of the ejection. Witnesses said my chute had barely opened before I plunged into the shallow water of Truc Bach Lake. I landed in the middle of the lake, in the middle of the city, in the middle of the day. An escape attempt would have been challenging. (189)

Things happen quickly here. The scene is over in seven sentences—no description of what the blackout felt like, no sense of imminent death. Point of view switches with equal speed. McCain is fully aware until he’s flung out of the plane and loses consciousness. Then his narration has to resort to an objective report of what happened while he was out. (“Witnesses said…”) The statement is backed up by a quick, vernacular summary of where and when he landed. The tone then switches to understated reflection, using the flat language of the stoic man of war: Escape wouldn’t have been impossible, or fatal, merely “challenging.” The paragraph plays down the crisis of survival by tapering into ironic self-effacement.

The rule of three is one of the writer’s best friends. The last sentence of the first paragraph renders three McCain actions—radioing, reaching, and pulling—in swift succession. Injuries pile up in triple-formation too: arm, arm, knee. The third trio is casual but memorably repetitive: middle of the lake, middle of the city, middle of the day. Should McCain claim that he, like Hamlet, “uses no art at all,” a narratologist will remind him of the technique pervading this passage—and his book’s opening. In a novel, mentioning a ship called Proteus would foreshadow the changes that young John will undergo. And James Wood complains in his recent How Fiction Works that a great many “apprentice novels” begin with the narrator pondering a family photo (95-96).

Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1921), a classic of literary narratology, distinguishes two methods of narration. The scenic method strives to make each moment palpable through energetic description, while the panoramic one inclines toward summary and generalization. Along this (fairly rough) continuum, Dreams from My Father lies closer to the scenic pole and Faith of My Fathers is closer to the panoramic one. Both autobiographies deploy the rhetoric of fiction, and both are unavoidably artificial. And each one’s technique (subtly eloquent versus direct and plain-spoken) creates a voice that fits the man’s narrative and his public persona.

Peopling the story

Characters in a narrative are usually identified by their roles and their traits of personality. Indiana Jones is a professor and adventurer, an intellectual cowboy. He is courageous, knowledgeable in his field, risk-loving, a bit insolent, somewhat impetuous, and so on. (For more on character construction, see my third essay in Poetics of Cinema.) Given very few cues we can fill in a character, so it becomes important that people who would become characters in their own stories send out the right signals. Rewriting real life is hard.

In the presidential campaign, it isn’t hard to identify the traits that the candidates are trying to define. All want to show integrity, resolve, prudence, a willingness to sacrifice for the greater good, and so on. But each candidate has also become identified with more individual traits. Without my enumerating them, let’s try a game.

Imagine our candidates as people in a high school. (2) Which one is the assistant principal on the verge of retirement? Which one is the social studies teacher who can always be led off the lesson plan with a strategically innocent question? Which one is the earnest first-year teacher, convinced that he can reform secondary education by reaching miscreants? And which one is Miss Popularity, cruel queen of the cliques, bluffing her way through assignments?

Maybe you don’t agree with my assessment of the candidates’ traits, but you knew exactly whom I referred to in each case. That’s because at least one narrative frame has sorted the characters along these lines. It’s a little scary to see that a flesh-and-blood person can be “characterized” so stereotypically, but whatever our political protagonists are like privately or deep down inside, as characters in the narratives that they spin or others spin around them, they fit well-worn templates.

Indeed, they can strive quite consciously to do that. To claim to possess “audacity” or to call yourself a “maverick” is to conjure up a set of traits, and these have implications for how you will act. As your actions mount up, a portrait snaps into focus that is hard to eradicate. Sarah Palin, introduced as a hard-edged fighter in the mold of Hillary Clinton, has been the most obvious instance of gradual revelation. She was an outline waiting to be filled in with events, and despite the campaign’s efforts to control what those events were, damaging pieces of behavior have mounted up and campaign leaks have confirmed their dire side. Palin now stands as a provincial politician adept at small-scale patronage whose ignorance of policy, world affairs, and science is abysmal and invincible. This has not kept some people from admiring her, of course.

Palin betrays no change in personality over the course of the campaign, and neither does Biden. According to reporters who cover him, he’s the same Joe he always was, take it or leave it. For real change—not of America’s direction but of public personas—we need to look at the top of the ticket. In the course of the campaign, for example, Obama has managed to seem consistent with his core program while having “seasoned” and “matured,” thanks to the tough primary fights. (Another cluster of narratives I can’t tackle here.)

McCain has been rendered as changing too, but not in a good way. One prominent large-scale narrative has portrayed him as losing some of his independence of thought—tacking to the right on cultural matters, losing the argument about his running mate. Few speak of the old Barack Obama versus the new one, but the narrative of John McCain 2.0 has stuck. Mr. Roberts has become the captain himself—a man crumpled with vexation, the cranky officer he would have rebelled against at Annapolis. I suspect that some day a McCain biographer will construct a narrative that shows him to have become a tragic figure.

The big three ingredients

Narratives arouse emotions in us; some would say that’s their chief purpose. The emotions can be of all kinds—pity, sympathy, indignation, joy, and down the line. But are there emotions characteristic of narrative in general? The theorist Meir Sternberg (3) has suggested that a narrative as such, regardless of other emotions it can conjure up, depends on three emotional states. Simplifying a bit, we can say that stories create curiosity about past events, suspense about future events, and surprise by means of unexpected events. Whatever other emotions a narrative evokes, we need to feel at least one of these three states.

Most narratives invoke all of these, but some genres rely on more than others. Detective stories rely a lot on curiosity, as characters try to solve the crime by exposing the events that led up to what’s happening now. Likewise, psychological tales—like Obama’s search for his roots—will evoke curiosity about the origins of events or personality traits. Action-driven narratives rely heavily on suspense: Will the protagonist reach her goals, or even just survive? The Dark Knight, with all its ticking clocks and hairbreadth escapes, is driven chiefly by suspense. (For more on suspense, you can visit this entry.) Plots with “a sting in the tail,” such as in stories by O. Henry and Roald Dahl and the early films of M. Night Shyamalan, have endings that depend to an unusual degree on surprise.

We can distinguish the two Presidential campaigns’ “master narratives,” along these dimensions. In the ongoing electioneering, Obama’s campaign is now driven almost completely by suspense. He’s not asking us to find out more about what led to the war in Iraq or the economic collapse or the crumbling infrastructure; it’s assumed that we know enough backstory. Everything is about what comes next. Ask any Obama supporter the predominant emotion she or he feels, and I’ll bet it will be suspense. What will happen next? What could throw the juggernaut off course? Fingers crossed: The very image of suspense.

McCain, by contrast, is running a campaign driven by curiosity and surprise. Many of his talking points dwell on the past. Who is Barack Obama, really? What did he have to do with Ayers, Rezko, the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac executives? Why did he sit in Jeremiah Wright’s church? And so on. These questions ask us to feel curiosity in the form of suspicion about McCain’s rival. The fact that most in his audience haven’t taken up the hint has driven the campaign to try to invoke another emotion: surprise. The pick of Sarah Palin is the most obvious instance, but several others have followed: suspending the campaign, promising to buy people’s mortgages, yanking Joe the Plumber out of obscurity as an emblem of small business, even the “not ready yet” tagline of a recent ad. There may be more surprises to come, as gloomy Democrats fear (which only increases their feeling of suspense). At this point, the act of winning would be the ultimate McCain surprise.

So the campaigns may teach us something of interest about narratives: You can’t have a gripping narrative without some suspense. You can do without curiosity or surprise, but a story lacking suspense won’t keep us turning enough pages to be curious or surprised. (4) Maybe that’s why the McCain campaign never had a “compelling narrative.” It didn’t build up enough of a sense of how it would win or how, after the election, the future would be different.

Narrative plus

On 29 October, the Obama campaign ran a 30-minute television film, American Stories, about why he should be president.This infomercial is a gift to the film analyst, and there’s much more to say about it than I can articulate here. I’ll concentrate on one intriguing aspect of it.

Narrative isn’t the only way to organize a film or literary text. In Film Art, we suggest that there are other principles of organization. Using categorical form, you can survey different types of things, like baseball cards or political systems, without telling a story. You can use a rhetorical format, making an argument for a position you believe in by adducing reasons. What we call associational form can link various images, sounds, and actions through analogy, contrast, or metaphorical connection; one example would be the film Koyaanisqatsi. And very often these principles can combine in a single book, film, or tv program.

American Stories isn’t centrally about Obama’s life or his family or running mate. Instead, the campaign created a series of anecdotal narratives. In turn, these narratives were linked by associations, not by the causal connections typical of narrative. Most broadly, Obama framed these narratives and linkages within a set of policy statements, so that the narratives provided illustrative examples of a rhetorical argument.

A football mom can’t pay for her husband’s medical treatment and must ration the kids’ snacks. An elderly retiree who paid off the family house must return to work to pay for his wife’s medications. A teacher in a school for at-risk kids must take a second job and still find time for her training, while deciding whether to buy a gallon or half-gallon of milk. A loyal Ford assembly-line worker is dropped to half-time; unlike his father and grandfather, he cannot expect a full pension. “Everybody here’s got a story,” Obama remarks.

The stories serve to illustrate a checklist of Obama’s positions: rescuing the middle class by means of tax cuts, making corporations accountable for pension fulfillment, working for energy independence, reforming health care, and shifting the war on terror to Afghanistan. So far, so categorical. But these talking points aren’t linked by logical inference but by association.

Take the story of teacher Juliana Sanchez. She instantiates the ‘education’ idea. Cut to Obama saying that teachers can do only so much: Parents must take responsibility for their children’s learning. Just as Juliana is taking care of her children, Obama recalls his mother taking care of him, as a single parent. Over family photographs he tells of his mother rousing him from bed to go through his lessons before she went to work. Link to Obama giving a speech in which he declares that every child needs a world-class education. Cut to him addressing the camera, declaring that he’s seen school reform work. The political has become doubly personal, exemplified by Juliana and by Obama’s own experience.

Then: “Just as I believe that every American has a right to an affordable education, I also believe that every American has a right to affordable health care.” This segues to a statement of Obama’s medical policy, which is followed by an account of his mother’s premature death, in which he shows that he knows what it is to lose a loved one. “It felt arbitrary.”

While the local connections are driven by associations like these, the overall shape of the half-hour is—no surprise—rhetorical. Obama is adducing reasons to vote for him. His case is that Americans are facing problems to which he has solutions. He could have presented the solutions as a list, in the form of bullet points or charts. Instead, he makes the problems concrete by illustrating how they affect ordinary people, including his own family, and then presents his solution by talking to an audience.

This use of rhetorical form contrasts with the one we discuss in Film Art (Chapter 10), when we analyze The River (1937). In that film, director Pare Lorentz doesn’t highlight individuals’ experience but creates a vast, sweeping story of erosion on the Mississippi river. Correspondingly, Lorentz doesn’t give the solution to the problem as a speech; it is presented in images of people taming the river, building the dam, and settling in new communities.

Obama could have adopted Lorentz’s strategy by tracing a broad history of the last eight years of Republican government, leading up to the financial crisis as a climax of mismanagement, and then turning to his policy prescriptions. He chose, as his campaign has largely chosen, not to rehearse the mistakes and misdeeds of the past (with which many Democrats were involved as well) but to put the emphasis on current conditions and hope for the future. Instead of Lorentz’s epic sweep, which arouses a feeling of grandeur and civic pride in getting a big job done, the Obama film asks us to empathize with “Americans looking for real and lasting change that makes a difference in their lives.”

Thanks to this blend of different types of formal organization, even the abstractions of policy draw upon the powers of storytelling. Maybe this campaign really is all about narratives. If so, maybe narratology can illuminate public discourse in useful ways.

Just don’t call this blog entry a deconstruction.

(1) Roland Barthes, “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives,” in Image Music Text, ed. and trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977). Barthes’ essay originally appeared in Communications 8 (1966), devoted to semiological research into narrative. Assembling a veritable who’s who of Structuralism, the issue included essays by Greimas, Bremond, Eco, Todorov, and Genette, as well as Christian Metz’s essay on the “Grand Syntagmatic” of narrative film.

(2) People say that Hollywood is high school with money, and that Washington is Hollywood for ugly people. So Washington must be high school, money, and ugly people? Obama and Palin seem to disprove the last condition.

(3) Sternberg laid out these principles in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), one of the finest studies of narrative theory I know. He elaborated the ideas in two articles under the title “Telling in Time.” See Poetics Today 11, 4 (Winter 1990), 901-948, and 13, 3 (Fall 1992), 463-541.

(4) Of course there is suspense on the McCain side too, but more and more it consists of the question: How bad will the damage be? Although the Obama campaign hasn’t exploited curiosity about McCain’s campaign narrative, the press has done so by slowly creating a backstory about Palin’s record and the way she was selected.

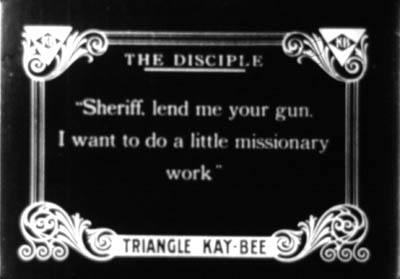

Lucky ’13

The Mysterious X (1913).

Each film is interlocked with so many other films. You can’t get away. Whatever you do now that you think is new was already done in 1913.

Martin Scorsese, quoted in Scorsese by Ebert (University of Chicago Press, 2008), 219.

DB here:

Most historical events don’t abide by clocks and calendars. Seldom does a trend begin neatly on one date and end, full stop, on another. Changes have vague origins and diffuse destinies. When Kristin and I, along with others, argued for 1917 as the best point to date the consolidation of the Hollywood style of storytelling, we realized that it’s a useful approximation but not as exact as a Tokyo subway timetable.

It’s just as hard to argue that a year constitutes a meaningful unit in itself. Who expects anything but tax laws to change drastically at midnight on 31 December? Yet evidently our minds need benchmarks. Film historians, while being aware that trends are slippery and dating is approximate, have long spotlighted certain years as particularly significant.

Take 1939, which has become a sort of emblem of the peak achievements of Hollywood’s Golden Age. We had Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Only Angels Have Wings, Stagecoach, Gunga Din, Wuthering Heights, Dark Victory, Young Mr. Lincoln, Beau Geste, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Ninotchka, The Roaring ‘20s, and Destry Rides Again. I’d watch any of those, except Gone with the Wind, right now—something I find it hard to say about most Hollywood movies I’ve seen in 2008.

Another strong year is 1960, with La Dolce Vita, L’Avventura, Rocco and His Brothers, The Apartment, Elmer Gantry, Spartacus, Psycho, Exodus, The Magnificent Seven, Shadows, Late Autumn (Ozu), and The Bad Sleep Well (Kurosawa). Arguably, 1960 was owned by the French, who gave us Breathless, Shoot the Piano Player, Paris nous appartient, Les Bonnes femmes, Le Trou (Becker), Moi un noir (Rouch), and Letter from Siberia (Marker). (See Postscript.)

Let’s go back still further. Researchers sometimes split the silent-film period in two, with the first stretch, usually called “early cinema,” running up to 1915 or so. (1) The second phase then runs roughly from 1915 to 1928. (2) So for many historians the year 1915 functions as a tacit pivot-point, and it is remembered not only for The Birth of a Nation but also for Regeneration, The Tramp, Kindling, The Cheat, Les Vampires, Daydreams (Yevgenii Bauer), and several William S. Hart films. But another year holds a special place in the minds of silent film aficionados.

Over a decade ago, the annual Days of the Silent Cinema festival (Il Giornate del cinema muto), took 1913 as its focus. (3) It was an extraordinary year. Denmark produced Atlantis (August Blom) and The Mysterious X (Benjamin Christensen). From France we had L’Enfant de Paris (Leonce Perret), Germinal (Albert Capellani), and Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas series. Germany gave us Urban Gad’s Engelein and Filmprimadonna and Franz Hofer’s obsessively symmetrical The Black Ball. The staggering set of Italy’s Love Everlasting (Ma l’amor mio non muore!, Mario Caserini) was matched by the breadth of Enrico Guazzoni’s Quo vadis? In Russia Bauer released Twilight of a Woman’s Soul. American audiences saw Traffic in Souls (George Loane Tucker) and Death’s Marathon and The Mothering Heart, from a guy named Griffith. Several historians would argue that 1913 marked the first major achievements of film as an artform.

Two outstanding films of that annus mirabilis have recently been issued on US DVD. One is a striking accomplishment, the other a flat-out masterpiece. Both discs belong in the collections of everyone who’s serious about cinema.

Your call is important to us

A wife and her baby are alone in an isolated house when a tramp breaks in. As the wife tries to keep the invader at bay, her husband happens to telephone and learn what’s happening. He scrambles to return home. He steals an idle car, and its owner, accompanied by police, race after him. We cut rapidly between the besieged mother and the husband’s frantic drive, as he is in turn pursued. Just as the tramp is about to attack the wife, the husband bursts in, followed by the police. The family is saved.

This is the story of the 1913 one-reel film, Suspense, co-directed by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley. If the plot sounds familiar, it’s probably because you know that one of D. W. Griffith’s most famous films, The Lonely Villa (1909) tells the same basic tale.There are still earlier versions, including one, The Physician of the Castle (Le Médécin du chateau, 1908), which may have inspired Griffith. The ultimate source seems to be a 1902 play by André de Lord, Au téléphone (translated here).

So Weber and Smalley are reviving an old idea. Their task is to make it fresh. How they do so has been studied in depth by Charlie Keil in his book Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907-1913.I can’t match Keil’s subtlety, and it’s better that you see the film first, so I’ll drop only some hints, pointers, and comments.

We’re inclined to say that The Lonely Villa influenced Suspense. But maybe we can capture the situation in a more illuminating way. The art historian E. H. Gombrich has suggested that we can often trace the relationship between artworks in terms of schema and revision. (4) A schema is a pattern that we find in an artwork, one that a later artist can borrow. Most often, later artists copy the schema straightforwardly. This is the usual way we think of influence. But instead of replicating the schema, the next artist can revise it. She can elaborate on it, strip it to its essence, drop parts and add others, whatever—in order to achieve new purposes or evoke fresh responses.

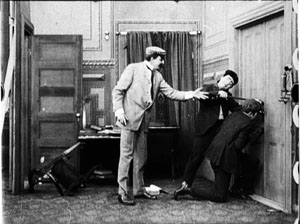

In The Lonely Villa, Griffith uses crosscutting to build suspense. He cuts among the thuggish vagrants trying to break in, the wife and daughters trying to hold them off, and the father learning by phone of the situation and then plunging after them with a policeman. The obvious pattern here is the principle of alternation between different lines of action, all taking place at the same time and converging in a last-minute rescue.

So Smalley and Weber inherit the crosscutting schema, but they go beyond simply copying it. They find ways to revise it, some quite surprising. These revisions aim to create more tension and to dynamize the situation.

The obvious option, at least to us today, would be to use more shots than Griffith does; we think that increasing the cutting pace builds up excitement. Interestingly, however, Suspense uses only a couple of more shots than The Lonely Villa within a comparable running time. (5) We usually expect that American films become more rapidly cut as the 1910s go on, but this isn’t the case here. Shortly, I’ll suggest why.

Smalley and Weber recast Griffith’s parallel editing in several ways. For instance, The Lonely Villa prolongs the phone conversation between husband and wife, building suspense through the husband’s instruction to use his revolver on the thugs. Suspense, by contrast, doesn’t dwell on the telephone conversation but devotes more time (and shots) to the chase along the highway. That’s because Weber and Smalley have complicated the chase by having the husband pursued by the irate motorist and the police, something that doesn’t happen in the Griffith film.

Just as important, Smalley and Weber revise the crosscutting schema through framings that are quite bold for 1913. For example, Griffith’s tramps break into the house in long shot, and they move laterally across the frame.

But Weber and Smalley’s tramp sneaks steadily up the stairs, into a menacing extreme close-up.

Elsewhere, Suspense gives us close views of the wife and of the door as the tramp breaks in. There are oblique angles on the back door of the house, and virtually Hitchcockian point-of-view shots when the wife sees the tramp breaking in and he looks straight up at her.

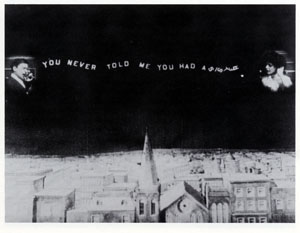

What struck me most forcibly on watching the film again was the way in which Weber and Smalley’s daring framings serve as equivalents for parallel editing. In effect, they revise the crosscutting schema by putting several actions into a single frame. The most evident, and the most famous, instances are the triangulated split-screen shots. They cram together three lines of action: the wife on the phone, the husband on the phone, and the tramp’s efforts to break into the house (here, finding the key under the mat). (6)

Split-screen effects like this were common enough in early cinema, especially for rendering telephone conversations. Eileen Bowser points out that the three-frame division was one variant, with a landscape separating the two callers. (7) Her example is from College Chums (1907).

But my sense is that in early cinema the split-screen effect was used principally for exposition or comedy, not for suspense. Smalley and Weber have made this framing substitute for crosscutting: instead of giving us three shots, we get one, showing the plot advancing along different lines of action. These splintered frames function much like Brian De Palma’s multiple-frame imagery in Sisters, Blow-Out, and other films. There’s also the nice touch of the conical lampshade over the husband’s head, providing a fulcrum for the composition.

Earlier in the film, instead of crosscutting between the tramp outside and the wife indoors, Suspense gives us both in the same shot, with the tramp peeking in behind her.

A more ingenious revision of the crosscutting schema comes during the shots on the road. Instead of cutting between the father in the stolen car and the police pursuing him, Suspense packs them into the same frame. This is done not only in long shot but also in striking depth compositions.

Flashiest of all are the shots showing the pursuers reflected in the rear-view mirror of the father’s car as he races ahead of them.

Again, a single framing has done duty for two shots, one of the father looking back and another showing the cops coming closer to him. By compressing several lines of action into a single frame, our 1913 film doesn’t need to use significantly more shots than the 1909 one.

These are just a few of the imaginative ways in which Weber and Smalley have recast their standard situation. I could have considered as well the unobtrusive use of the knife as a multi-purpose prop, the echoed shots of mirrors, and the shrewd employment of repetitions in the intertitles.

It would take an early-cinema specialist like Keil to trace out all the connections between Suspense and other films of its era. One among many would be the fact that Griffith wasn’t exactly standing still between 1909, the year of The Lonely Villa, and 1913. For instance, his Battle at Elderbush Gulch, made about the same time as Suspense (though released in 1914), displays far more rapid cutting than Weber and Smalley attempt. Griffith also employed a swelling advance to the foreground, like that of the tramp shot I showed above, in The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912).

Here, Smalley and Weber seem to have replicated a schema that was believed to ratchet up tension, the so-called looming effect.

The very title of the film exhibits self-consciousness about its artistic purpose. By 1913, it seems, American filmmakers were confident enough in their skills to announce their aims. We want, the title seems to say, to arouse you, to make you wait, hanging there, for the resolution. We know how to tell a twelve-minute story cinematically. The film seems uncannily to anticipate all those one-word titles that Hitchcock invoked to unsettle us–Suspicion, Spellbound, Psycho, Frenzy. As in a Hitchcock movie, the fact that we are pretty certain how Suspense will turn out doesn’t seem to dissipate our anxiety. (For more on this paradox of suspense, see this entry.)

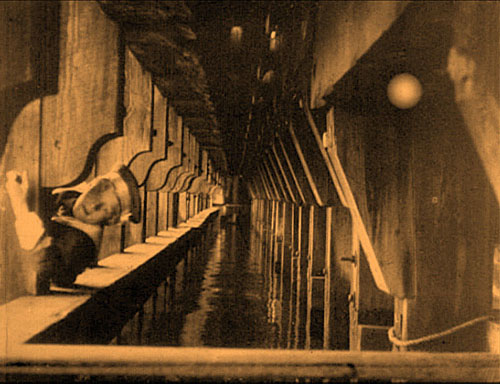

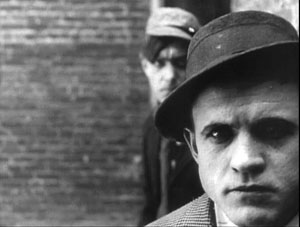

Tunnel vision

It was during the Pordenone 1913 season that the full brilliance of Victor Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm hit me. I had seen the film a couple of times before and found it deeply moving in its restrained treatment of a poignant situation. The film traces the dissolution of a family. Sven Holm is doing a brisk retail business, but his health problems, along with a thieving clerk, plunge the family into poverty. When Holm dies, his wife Ingeborg must take the children into the poorhouse, and from there they are boarded out to foster families. Her plight worsens over the years, and its sorrowful depths are revealed when her son, now grown, returns to visit her.

Ingeborg Holm has long been recognized as a milestone in European film, not least for its effect on improving Sweden’s treatment of the poor. (8) The acting style is muted and delicate, with no mugging or arm-waving. For long periods, the main actors turn from the audience. (9) Just as impressive are the poised compositions, sustained in unhurried long takes. These give what is essentially a bourgeois tragedy a kind of majestic relentlessness. Watching, I remembered what Dreyer had admired in Sjöström’s Ingmar’s Sons (1918):

The film people here at home shook their heads because Sjöström had really a boldness to let his farmers walk heavily and soberly as farmers do. Yes, they used up an eternity to come from one end of the room to the other. (10)

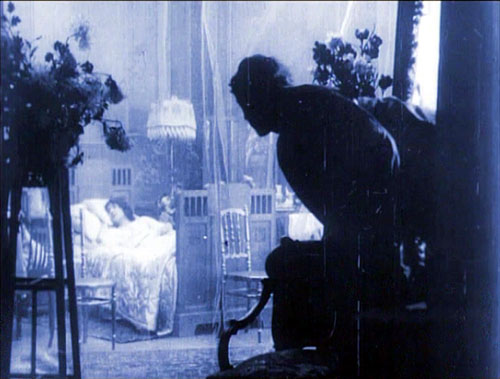

But sitting in the Cinema Verdi in 1993, I spotted yet another level of artistry. Knowing the story of Ingeborg Holm, I was able to watch the shots unfold. I could study how Sjöström was unobtrusively moving characters so that they became shifting centers of interest. Although he didn’t cut in to close-ups, he harmonized his actors’ movements so that at one point you noticed Ingeborg, at another her husband. Performers spread themselves across the frame, arrayed themselves in depth, turned from or toward the camera. Most subtly of all, one actor might mask another one, driving our attention to other parts of the frame. Sjöström could sustain this intricate play of blocking and revealing for minutes on end.

My favorite example of this tactic is the three-minute passage showing Ingeborg’s daughter and son taken away by new mothers. You can read the whole discussion on pp. 191-195 in On the History of Film Style (1997), but here is an excerpt, with stills intercalated. (These stills, grabbed from the DVD, lack a little on the left. The film has been printed and reprinted so many times, and now fitted to the TV monitor, that it has lost some information along that edge.)

Ingeborg’s entry with her children from the rear doorway establishes the trajectory that will be followed during the scene, as foster mothers come in and take away the children. (Again, the scene is built around movements toward and away from the camera.) In a brilliant stroke, Sjöström immediately plants the young son in the foreground, back to us. The boy will stand there immobile for this first phase of the scene, occasionally serving to block the superintendent.

Ingeborg buries her face in her daughter’s shoulder at the precise moment the foster mother enters from the rear left. She passes behind Ingeborg, and as she is momentarily blocked, the superintendent twitches into visibility, handing the woman a document to sign.

During the signing, when the woman is briefly obscured, the superintendent shifts position again and Ingeborg lifts her face once more. Then Ingeborg and her daughter move slightly leftward as the foster mother comes forward.

This phase of the scene concludes with the departure of the daughter and the embrace of Ingeborg and her son in the foreground, once more concealing the superintendent.

Granted, I picked one of the film’s most exactingly staged scenes, but there are several other examples. Consider the climax, when the adult son comes to visit Ingeborg: the camera position and staging ask us to recall the scene I’ve just mentioned. Or take a look at the handling of the space behind the counter in the various scenes in the Holms’ shop. One instance surmounts this section.

This choreography is hard to catch on the fly: by the time you notice a change, what prepared for it has gone. To understand the overall dynamic, we must reverse-engineer the effects, moving backward from the result to the conditions. As I studied the film, it became clear that creating shifting centers of interest was basic to the scenes’ effects. All the finesse of acting, both solo and ensemble, would come to little if we weren’t primed to watch the most important area of the shot. Directors of the 1910s became supremely skilful in guiding our eye from one major story point to another within the fixed frame.

Some of the tactics of guiding our attention could be borrowed from other arts. Painting and theatre supplied certain schemas, like placing an item in the center of the picture format and turning faces toward the viewer. But some tactics for directing our eye relied on capacities that were as “specifically cinematic” as cutting was argued to be. Theatre is staged for many sightlines, but cinema is staged for a single one, that of the camera lens. That fact allowed directors to organize the unfolding action in depth, prompting the viewer to notice things at many distances from the camera.

It also allowed a precise blocking and revealing of information that would not work on the stage. In a live theatre performance, the slight shifts we detect in the Ingeborg Holm scene would be apparent to only very few viewers; people sitting in other vantage points wouldn’t see them. For another example of this phenomenon, go elsewhere on this blogsite.

There’s a more basic explanation of what’s going on. Cinematic space is a result of optical perspective, like the space of classic painting. The actors may seem to be standing in a cubical space, but in fact they move within a tipped-over pyramid, with the tip resting at the camera lens. They work inside a ground area that’s the shape of a slice of pie. Here’s a reminder from The Black Ball.

When there are figures close to the camera, as here, they fill up more of the frame, indicating that the field of view has narrowed. Filmmakers of the 1910s had discussed this property of their “cinematic stage,” so as researchers we can confirm that the control of position and timing we observe on screen results from the firm intentions of the makers. They might have echoed Uccello, the Renaissance artist who bent over his drawings late at night and exclaimed: “How sweet a thing is this perspective!”

Suddenly the tableau tradition made sense to me. Directors had to organize both the two-dimensional composition and the tapering three-dimensional playing space in front of the camera. The purpose was to create ever-changing centers of interest, laterally and in depth, flowing along with the key moments in the unfolding action.

By studying the same tactics in Feuillade, Bauer, and others, I found that these principles offered a fruitful way to understand much of what was happening in the films of the tableau era. The dynamic of schema and repetition/revision was at work as well, since I found earlier, more rudimentary uses of these principles; these were then refined during the 1910s. Moreover, the idea helped me generalize beyond that era and analyze later directors, including Mizoguchi Kenji and Hou Hsiao-hsien, who also used staging to shape the viewer’s experience. The results can be found in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Those books largely owe their existence to that flash of awareness kindled by Ingeborg Holm. (11)

We can’t reconstruct Sjöström’s stylistic development with much confidence. (12) His first directed film, The Gardener (Trädgärdsmästaren, 1912) survives, but I saw it before I knew how to watch 1910s movies in this way, so I can’t comment on it. Of the twenty-six films he made from 1912 to 1917, nearly all have been lost. Apart from Ingeborg, I have managed to see Havsagamar (The Sea Vultures, 1916). This retains aspects of the tableau tradition, but virtually no scenes display the intricate staging of his 1913 masterpiece.

In the late 1910s, judging by the films we have, Sjöström seems to have moved quickly toward continuity editing in the American vein. (13) The Girl from Stormycroft (Tösen frän Stormyrtorpet, 1917) contains extended passages of analytical editing, and the scenes display a freedom of camera setup one seldom sees in European cinema of the period. Sjöström clearly understands the principles of continuity down to the smallest detail. For instance, he not only uses the frame-edge cut (the cut that lets a character exit one shot and enter another, as the body crosses the frameline); he accelerates it. Our heroine leaves the kitchen, and in the shot’s final frame she hits the right edge. Another director would have had her exit the frame entirely and held the kitchen shot a little longer, to give her time to get to the next room. But Sjöström simply cuts to her already in another room, completing her trajectory.

Sjöström presumes that the constant pace of her approach and the vector of her movement will smooth the shot-change. It does, but few directors of that day would had such confidence that our mind would create continuity of motion.

During this summer’s archive viewing, I spent some time studying Sjöström’s cutting in The Girl from Stormycroft and subsequent films. I may offer some more thoughts later. For now I’ll just say that in these early years we seldom encounter such a versatile director, one who mastered the tableau tradition and then moved, with apparently little effort, to nuanced continuity editing. More generally, examining his technique isn’t a dry exercise. We never lose by studying craftsmanship. Sjöström’s films succeed because his style carefully guides our moment-by-moment apprehension of the heart-rending stories he has chosen to tell.

Have I convinced you to surrender your credit-card number? Suspense is available in a dazzling Flicker Alley collection, Saved from the Flames, compiled from the French series Retour de flame. Ingeborg Holm comes with a tinted print of the estimable Terje Vigen (A Man There Was) on a DVD from Kino. The latter disc includes vibrant scores from Donald Sosin and David Drazin.

(1) For the purposes of the outstanding Encyclopedia of Early Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2005), the editor Richard Abel considers that the early cinema constitutes the period from film’s invention ca. 1894 to the mid-1910s.

(2) Silent films were still made into the 1930s, notably in Russia and Japan—a situation that shows the rough-and-ready quality of period divisions.

(3) For an informative series of articles around the 1913 theme, see Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994).

(4) Gombrich proposes these ideas at various points in Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, new ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). The book is a milestone in twentieth-century humanistic inquiry.

(5) The Lonely Villa (1909) has, in the version I’ve seen, 54 shots in a 750-foot reel (that is, about twelve and a half minutes at 16 frames per second). Suspense has nearly the same number of shots, 56, in about the same running time.

(6) Sharp-eyed readers will recognize one of these shots as Fig. 5.82 in Film Art: An Introduction, 8th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 187.

(7) Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema 1907-1915, vol. 2 of History of the American Cinema (New York: Scribners, 1990), 65.

(8) For more background on the film, see Jan Olsson, “‘Classical’ vs. ‘Pre-Classical’: Ingeborg Holm and Swedish Cinema in 1913,” Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994), 113-123.

(9) Kristin wrote about this technique in “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85. She also discusses it in our Film History: An Introduction, 2d ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 67.

(10) Carl Dreyer, “A Little on Film Style,” Dreyer in Double Reflection, ed. and trans. Donald Skoller (New York: Dutton, 1973), 133.

(11) I was probably primed for this by lectures presented by Yuri Tsivian, who has long been studying mirrors in 1910s cinema and calculating how they revealed offscreen space.

(12) Detailed information on Sjöström’s relation to the film industry in these years can be found in John Fullerton’s epic Ph. D. thesis, The Development of a System of Representation in Swedish Film, 1912-1920 (University of East Anglia, 1994). See also Fullerton, “Contextualising the Innovation of Deep Staging in Swedish Film,” Film and the First World War, ed. Dibbets and Hogenkamp, 86-96.

(13) Several people have analyzed Sjöström’s editing. Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 133-136 shows how cutting supports the acting in a crucial scene of Ingmar’s Sons. Tom Gunning’s essay “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s anthology Nordic Explorations: Film before 1930(Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), 204-231, argues that Sjöström’s cutting gives his characters a degree of psychological opacity. Most recently, in an unpublished paper Jonah Horwitz discusses patterns of performance, composition, and editing in Terje Vigen (1917).

Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (1913).

PS 31 August: Some corrections. David Cairns writes to point out that the triangle at the top of the frame in the Suspense split-screen isn’t a lamp but simply the shade behind the father’s head, cropped by the masking. Wishful thinking on my part, I’m afraid. By the way, David has an intriguing movie giveaway going on his site.

Roland-François Lack corrects dates on two of my Greatest French Hits from 1960: “The great Marker from that year is Description d’un combat, not Lettre de Sibérie (1958), and likewise Rouch’s Moi un noir is from 1958.” Thanks to him and David. To my original list, I should probably have added Cocteau’s Testament d’Orphée, released in 1960.

Games cinephiles play

From DB:

The Europeans have long been fascinated by the subject of cinephilia. The French supplied not only the word but the most outstanding instances, from the founding of Cahiers du cinéma to the passions of the Nouvelle Vague. (1) In the last decade particularly, French critics have often returned to the subject–worrying, for instance, that home video might have changed or even decimated cinephilia–and this has led critics from other countries to join in.

I was reminded of how strongly the idea persists when, at Il Cinema Ritrovato this year, I was invited to sit in on one of several lunches at which critics and historians talked about the subject. The discussion consisted mostly of recollections of the guests’ first encounters with cinema, of the films that affected them most powerfully, of the film-related activities they engaged in during their salad days. Some of us hadn’t done this exercise in autobiography before, but others had had practice. Jonathan Rosenbaum and Eric de Kuyper had both written a fair amount about the sources of their affinity for film. (Sometimes I feel I remember Jonathan’s life better than my own.)

What is cinephilia? Literally, the love of film. But everybody likes, even loves film, no? The term “cinephilia” connotes an overwhelming passion for film, even an obsession about it. And not just particular films. I meet civilians all the time who are devoted to their favorites—The Godfather, The Princess Bride, The Matrix. But they’re not cinephiles. So is it just a matter of quantity? Is it just that the cinephile enjoys a great many movies? Partly, but there’s still more to it.

The cinephile displays symptoms of cinemania, as chronicled in the film of the same name. If you haven’t seen it, Cinemania tracks five people who organize their lives around watching movies. As I watched it, some of my reactions ran to “Wow, that is really hard-core,” but every now and then I thought: “Well, that‘s not so weird. I do that.” So I see the similarities.

Most obviously, both the cinephile and the cinemaniac show symptoms of compulsiveness. Each one makes lists, checks off titles seen, plans a day of moviegoing with care. When visiting a new city, s/he first scans the cultural scene for what’s playing. Both types of film lover are strict—no pan-and-scan, no colorization, no dodgy projection. Either type might have a weblog or a diary or just patient friends. If s/he has friends.

But I do see differences. For one thing, most cinemaniacs like only certain sorts of movies—usually American, often silent, sometimes foreign, seldom documentaries. Do cinemaniacs line up for Brakhage or Frederick Wiseman? My sense is not.

Cinephiles by contrast tend to be ecumenical. Indeed, many take pride in the intergalactic breadth of their tastes. Look at any smart critic’s ten-best lists. You’ll usually see an eclectic mix of arthouse, pop, and experimental, including one or two titles you have never heard of. Obscurity is important; a cinephile is a connoisseur.

The real crux, I think, is this. The cinephile loves the idea of film.

That means loving not only its accomplishments but its potential, its promise and prospects. It’s as if individual films, delectable and overpowering as they can be, are but glimpses of something far grander. That distant horizon, impossible to describe fully, is Cinema, and it is this art form, or medium, that is the ultimate object of devotion. In the darkening auditorium there ignites the hope of another view of that mysterious realm. The pious will call Cinema a holy place, the secular will see it as the treasure-house of an artform still capable of great things. The promised land of cinema, as experimentalists of the 1920s called it: that, mystical as it sounds, is my sense of what the cinephile yearns for.

This separates the cinephile from the lover of novels or classical music. They love their art, I suspect, because of its great accomplishments. Who with literary or musical taste would embrace the subpar novel or the apprentice toccata? But cinephiles will watch damn near anything looking for a moment’s worth of magic. Perhaps this puts cinephiles closer to theatre buffs. They too wait hopefully for the sublime instant that flickers out of amateur performances of Our Town and Man and Superman.

That’s also why I think that the cinephile finds the desert-island question so hard to answer. What movies would I want to live with for the rest of my life? All of them, especially the ones I haven’t yet seen.

Another difference: Fussiness and solitude. The cinemaniac has a favorite seat, even if it’s way off to the side. To secure it, the cinemaniac shows up early and tries to be first in line. Your average cinephile isn’t so picky about where to sit, and so may slip in at the last minute. While waiting for the show to start, the cinemaniac seldom acknowledges others; a book is the faithful companion. But the cinephile is, if not extroverted, at least gregarious and wants to talk with other cinephiles.

What sort of talk? I’m glad you asked.

Cooperative games: Playing well with others

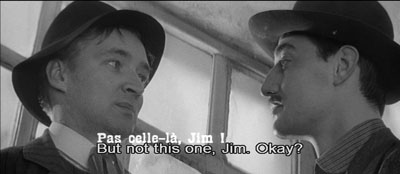

Jules and Jim leave a screening.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: Yeah, great!

Jules: Well, see ya.

Jim: Yup, later.

This is the minimal, polite cooperative game. When the energy level is cranked up, you get something like this.

Jules: Great movie! I love M*x *ph*ls.

Jim: God, yes. Those camera movements knock me out.

Jules: But then there’s R*n**r too!

Jim: God, I love R*n**r. And M*z*g*ch*–there’s a man for camera movements.

Jules: My man! M*z*g*ch* is just terrific.

This can go on indefinitely. To get a sense of how special cinephiliac enthusiasms are, imagine littérateurs talking about Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, and iambic pentameter in these terms.

A cooperative game can go a little further.

Jules: What a fantastic movie!

Jim: Yes, fabulous. M*nn*ll* movies get better and better, the more you see them.

Jules: I completely agree—except for The S*ndp*p*r.

Jim: Yeah, that’s kind of weak, but it’s got some good points.

Jules: Really? I haven’t seen it in twenty years.

Jim: I have a pretty good copy off Turner. Let me dub it and send it to you.

Jules: That’s really nice of you.

Even if Jim never sends the disc, he has played the game charitably and Jules has accepted graciously.

Jim: What a terrific movie.

Jules: I wasn’t so impressed. Want to grab a coffee and talk about it?

Jim: Good idea!

This is probably the optimal way to play Cinephilia cooperatively.

But many cinephiles want to play rougher. The extreme option is flat-out disagreement, usually expressed in terms that bluntly doubt the competitor’s sanity, intelligence, or good will. I won’t dwell on this abrasive strategy here. There are stealthier ways to go.

Competitive games: Upsmanship

Jules and Jim leave a screening.

Jules: I loved it. What did you think?

Jim: Well. . . Have you seen earlier films by H*ng S*ng-s**?

This is an opening gambit. If Jules says no, then Jim can say something like: It’s really one of his weaker movies or His films get worse and worse. Now Jules would be playing defense, on unfriendly terrain. If he hasn’t seen the other films, the comparison-strategy will be his undoing. So:

Jules: Yeah, I’ve seen all of them. I thought that this was a strong one.

Now Jim can fight to at least a draw. Maybe Jules was bluffing and hasn’t seen all the films; or maybe Jim remembers them better.

Jules has used what we can call the breadth strategy: I’ve seen more than you. This need not bear only on other films; it can work along other dimensions.

Jim: I was so impressed by St*g* Fr*ght, but I never heard anybody refer to it among H*tch’s best.

Jules: Well, in the critical literature it’s often considered a masterpiece. Have you read . . .?

Or:

Jules: Yes, it’s a great movie, but what a terrible print! The reel ends were chopped off, and there were splices all the way through. I remember seeing a pristine print at the Director’s Guild Theatre. [The haymaker:] Jane Wyman was there to talk about it.

With a silent film you can extend the strategy to multiple versions: I remember a MoMA screening that ran an extra half-hour or The DVD from Austria fills in the missing scenes with stills. Oh, you didn’t know there were missing scenes…? Jim doesn’t have many options here.

If Jules sticks to the breadth strategy, this can go on quite a while. Once I got cornered after a friendly critic asked me about 1930s Ozu. Yes, I’d seen them all. Naruse? Yes. Shimizu? Quite a lot. I held my own, but then he changed up his pitching rhythm: “And how about 1930s English comedies? No? Oh, you must see them—they’re wonderful.”

Akin to the breadth approach is the longevity strategy, aka I was here first. We old guys like to use this. It can get pretty brutal.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: First time you saw it?

Jules: Um, yeah.

Jim: It gets better on multiple viewings. I liked it when I saw it in 1971. In fact, I liked it so much I wrote about it for Sight & Sound. Let me send you a copy of the essay.

Jules: Um…thanks…

There’s also the depth strategy. Here the player goes very specific, invoking details that suggest sensitivity and massive memory power.

Jules: Great movie!

Jim: You said it. I especially liked the scene when the camera tracks sideways, picking up the back of the guy who’ll turn out to be so important at the end.

Jules: Yeah. . . Actually, I didn’t notice that.