Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

B is for Bologna

A big crowd assembles for one of the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore.

Not laziness or old age (we hope) but sheer busyness has reduced our Bologna blogging to a single entry this year. Last year we managed three entries, but this time there was just so much to see, from nine AM to midnight, that we couldn’t drag ourselves away to the laptop. That it was blazing hot and surprisingly humid may have given us less biobloggability as well. Still, DB has many pictures, so maybe a followup blog with unusual images of critics and historians disporting in the sun….

Some backstory: Hosted by the Cineteca of Bologna, Il Cinema Ritrovato is an annual festival of rediscovered and restored films. Every July hundreds of movies are screened in several venues. For our 2007 report, with more background and some orienting pictures, go here and then here and here. Watch a lyrical trailer for the event here.

As before, both KT and DB contribute to this year’s entry. But first, the breaking story.

Freder and Maria, together again for the first time

While we were there, the news of a long version of Metropolis broke. The estimable David Hudson offers a quick guide and an abundance of links at GreenCine. A rumor went around Bologna that fragments of the new Buenos Aires print would be screened, but instead there was a twenty-minute briefing anchored by Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek. Along with him, Anke Wilkening (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Stiftung), Anna Bohn (Universitat der Kunste, Berlin), and Luciano Berriatua (Filmoteca Espanola) provided some key points of information.

*Provenance: The “director’s cut” was released in Argentina during the 1920s, with Spanish intertitles and inserts made at Ufa. A collector acquired a print. (Once more we have a collector to thank for saving film history.) When the Argentine film archive (Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken) received the copy in the 1960s, a 16mm dupe negative was made, and the nitrate original was discarded, a common practice at the time.

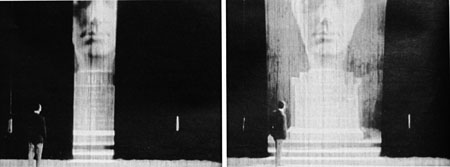

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Completeness: Contrary to some reports, virtually all the missing scenes are present on the Argentine print, the single exception being a small portion at a reel end. Among the new sequences are scenes filling in the roles of three characters (Georgy, Slim, and Josaphat), a car journey through the city, and moments of Freder’s delirium.

How can the researchers be confident that the print is so complete? It’s a fascinating story.

Metropolis has been reconstructed many times since the 1960s. In 2001, the Murnau foundation presented a digital restoration of the film supervised by Martin Koerber in collaboration with Enno Patalas. In this version, which is available on DVD (Transit Film, Kino International) about 30 minutes of the original material are missing. In 2003-2005 Enno Patalas and Anna Bohn together with a team at the University of the Arts in Berlin created a “Study Edition” version in which the missing footage was represented by bits of gray leader. For the first time the full length of the film was reconstructed with help from the the original music score.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

Bohm and Patalas’s comparative method proved itself valid: The Buenos Aires footage fitted the gaps in their study edition perfectly!

A viewing copy will not be forthcoming immediately, given the restoration task, but sooner or later we will have a good approximation of the fullest version of one of the half-dozen most famous silent movies. Getting news like this while among archive professionals is one of the unique pleasures of Cinema Ritrovato. (Special thanks to Dr. Bohn for clarification on several points and to enterprising film historian Casper Tybjerg, who helped me get a copy of the Die Zeit issue.)

Two Davids and a Kevin: Robinson, Brownlow, and Shepard at a critics’ lunch.

Powell meets Bluebeard and Bartók

KT: One of the high points of the week for me was Michael Powell’s 1964 film of Béla Bartók’s short opera Bluebeard’s Castle. It was made for German television and shown in Bologna as Herzog Blaubarts Burg. Unfortunately it was programmed opposite the screening of fragments from Kuleshov’s Gay Canary, but Powell’s post-Peeping Tom films are so difficult to see that I made the difficult choice and gave up hope of seeing the entire Kuleshov retrospective.

Despite being relatively recent in comparison with most of the films shown during the week, Herzog Blaubarts Burg is one of the most obscure. I felt it was an extremely rare privilege to see it, one which I will probably never have again, at least in so splendid a print.

The film belongs to the late period of Powell’s career, after the controversial Peeping Tom had made it impossible for him to work within the mainstream film industry. It was produced by Norman Foster—though not the Norman Foster who directed Journey into Fear and several of the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto films. This Norman Foster was an opera singer whose stage career was cut short by a dispute with Herbert von Karajan. His widow, Sybille Nabel-Foster, explained this and described how Foster produced and starred in two television adaptations, Herzog Blaubarts Burg and Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1966). Foster had originally approached Ingmar Bergman to direct the former, but when that proved impossible, Powell stepped in—and probably a good thing, too. It was definitely his kind of project.

The two performers are perfect for their roles. Foster plays Bluebeard brilliantly, having both a powerful bass voice and the necessary combination of handsomeness and a sense of threat. His co-star, the excellent soprano Ana Raquel Satre, recalls the pale beauties of some of Powell’s earlier films (Kathleen Byron as the increasingly mad Sister Ruth in Black Narcissus, Pamela Brown in I Know Where I’m Going!, and particularly Ludmilla Tcherina in The Tales of Hoffman), but she also bears a resemblance—perhaps deliberately enhanced through costuming and make-up—to Barbara Steele and other horror-film heroines of the 1960s.

The film was shot cheaply in a Salzburg studio, using garish, modernist settings against black backgrounds. These create a labyrinthine, floating space that avoids seeming stage-bound. (Hein Heckroth, the production designer, had previously worked on several Powell films, including The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffman.) I was reminded of Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982), which looks somewhat less original in the light of Powell’s film.

As Nabel-Foster explained, after its initial screening on German television, Herzog Blaubarts Burg has been shown seldom because of rights complications with the Bartók estate. Non-commercial screenings have occurred on public television in the U.S. and Australia, but basically the film is off-limits until the copyright expires in 2015, seventy years after the composer’s death. Nabel-Foster has been providently preparing for a DVD release, gathering the original materials.

The print shown was a privately held Technicolor original from the era, in nearly mint condition. (The British Film Institute has a print as well.) The sparse subtitles written by Powell himself were added for this screening.

I’m not convinced that the film is quite the masterpiece that some claim, but it is a major item in Powell’s oeuvre nonetheless, and I felt privileged to have seen it in ideal conditions.

[July 12: Kent Jones, a great admirer of Powell and Bluebeard’s Castle, tells me that he programmed it at the Walter Reade in New York for a centenary retrospective of the director’s work in 2005. Foster’s widow introduced that screening as well.]

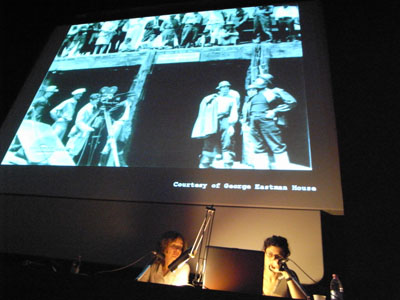

Janet Bergstrom and Cecilia Cenciarelli summarize their research on von Sternberg’s lost film The Sea Gull.

1908 and all that

KT: There were several programs of silent shorts, which I could only sample, as they tended to play opposite the Kuleshov films. As usual, the Bologna program included selections of short films from 100 years ago, so we were treated to numerous films from 1908. I was particularly pleased to see The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers, directed by Lewin Fitzhamon, who had made Rescued by Rover two years earlier. That film had been so fabulously successful that it had actually been shot three times as the negatives wore out from the striking of huge numbers of release prints.

The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers at first appears to be a sort of sequel (as it is described in the program), since it stars the same dog (Blair) who had played Rover, and again there is a kidnapped baby. It’s not really a sequel, though, since Cecil Hepworth, who had played the father in the earlier film, here appears as the kidnapper, and the dog is not named Rover. The new film is more fantastical than the original, since the dog races after the car in which the child is abducted and rather than fetching its master, effects the rescue itself by driving the car back home when the villain leaves his victim unattended!

Other 1908 films I particularly enjoyed: In Pathé’s Le crocodile cambrioleur, a thief hides inside a huge fake crocodile and crawls away, creating fear wherever he goes. The Acrobatic Fly by British director Percy Smith, provides a very close-up view of an apparently real fly juggling various small objects. (How was it done? It’s a mystery to me.)

Another retrospective series was “Irresistible forces: Comic Actresses and Suffragettes (1910-1915).” The suffragette films were rather depressing, despite the fact that many were meant at the time to be comic and amusing. Mostly the joke was how masculine these determined women were, a self-verifying proposition when the filmmakers often chose to have the suffragettes played by men. My favorite program was one involving early French female comics. I’ve long been fond of Gaumont’s Rosalie series since seeing a few at an early-cinema conference in Perpignon, France back in 1984. Rosalie, a chubby, cheerful little dynamo played by Sarah Duhamel, was highly entertaining in three films in the “France—Rosalie, Cunégonde et les autres…” program.

As Mariann Lewinsky, who devises these annual series, pointed out, Duhamel is the only early female French comic whose name we know. Léotine, represented here in Rosalie and Léotine vont au théâtre, is played by an anonymous actress. I had not encountered Cunégonde, also anonymous, before, but she proved to be quite amusing as well. I particularly liked Cunégonde femme du monde, where she plays a maid who dresses up as a society lady when her employers go off on a trip; the carefully constructed story and twist ending are impressive for such an apparently minor one-reeler.

It was a treat to see a succession of gorgeous prints of von Sternberg’s films. I particularly enjoyed seeing Thunderbolt (1929) again after many years. Back in 1983 I taught a survey film history course in which I used the director’s first talkie as my example of the transition to sound. Not a good example, I must admit, since Thunderbolt is completely atypical, with its highly imaginative use of offscreen sound. The second half, set primarily in a prison block, involves shouts from unseen cells and a small band that breaks into songs, often completely out of tone with the action, at unexpected moments. Eisenstein and the other Soviet directors would have thoroughly approved of its sound counterpoint. I have to admit that I prefer von Sternberg’s George Bancroft films (Underworld, Docks of New York, and Thunderbolt) to the Dietrich ones. Not only are the plots simpler and more elegant, but they contain a genuine element of emotion that is not, as in the Dietrich series, frequently undercut by irony.

I didn’t make it to many of the CinemaScope films playing on the very big screen in the Cinema Arlecchino theater, but I did enjoy two westerns. Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958) and John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1954) both looked terrific and were highly popular with everyone we talked to. The latter was particularly a revelation, since in contrast to the Mann, it hasn’t had much of a reputation among cinephiles.

A Rodchenko angle for Yuri Tsivian.

Teacher and experimenter

DB: As Kristin mentioned, we missed a lot of the “Hundred Years Ago” series—a pity, since 1908 is a miraculous year—in order to keep up with one of our favorite directors, Lev Kuleshov.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common to say that Eisenstein and Vertov were the most experimental Soviet directors, while the others were more conventional. Then we realized that in films like Arsenal (1928), Dovzhenko had his own wild ways. Then we discovered the Feks team, Kozintsev and Trauberg, and the bold montage of The New Babylon (1929). A closer look at Pudovkin, particularly his early sound films like A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933), revealed that he too was no timid soul when it came to daring cutting and image/ sound juxtapositions. But surely their mentor Kuleshov, admirer of Hollywood continuity and proponent of the simplest sorts of constructive editing, played things safe?

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

My admiration for Kuleshov, confessed in an earlier blog entry, already led me to spot some weirdnesses in Mr. K’s official classics. The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) boasts some very un-formulaic cutting in certain passages (including an upside-down shot when cowboy Jeddy ropes the sleigh driver), and By the Law (1926) makes chilling use of discontinuities when the scarecrow Hohlova holds the Irishman at gunpoint. But thanks to the retrospective we can confidently say that Kuleshov was no less venturesome, at least in certain projects, than his pupils.

Soviet specialists already suspected that The Great Consoler (1933) was K’s sound masterpiece, and another viewing confirmed it. It incorporates three registers. William S. Porter, in prison but serving in the pharmacy, witnesses brutality and oppression and is driven to drink. Under the name O. Henry he writes cheerfully sentimental tales as much to console himself as to charm readers. His stories are in turn consumed by shopgirls like Dulcie, a romantic who may not realize how unhappy she is. Kuleshov adds a level of sheer fantasy, represented by a pastiche silent film dramatizing O. Henry’s “A Retrieved Reformation,” in which a safecracker trying to go straight reveals his identity by saving a girl trapped in a bank vault. The embedded story features characters from the other two levels, convict Jimmy Valentine and Dulcie’s lover, a vaguely sadistic businessman in a ten-gallon hat.

The Great Consoler reminds us of the popularity of O. Henry in the Soviet Union, both among readers and the Russian Formalist literary theorists, who were fascinated by his flagrant, playful artifice. (Boris Eikhenbaum’s essay on the writer is one of the most brilliant pieces of literary analysis I know.) Even though Kuleshov must denounce Porter for reconciling the masses to their misery under capitalism, the zest of the embedded film and the unique architecture of the overall project pay tribute to another entertainer who did not forgo experimentation. And Kuleshov’s image of a writer in prison probably had Aesopian significance for artists in the era of Socialist Realism.

K’s other major sound experiment, less widely seen, is Gorizont (1932). The title is at once a man’s name and the Russian word for “horizon”—a metaphor literalized in the final shot of a train leaving a tunnel. As Yuri pointed out, it is one of the few Soviet films centered on a Jew, and so the formulaic growth-to-consciousness plotline takes on a new resonance in the light of Slavic anti-semitism. Lev Gorizont is an amiable, somewhat thick young man who dreams of emigrating to the US to make his fortune. But in New York he finds only poverty and disillusionment, eventually returning home to help make a better society. Famous for its use of sound, Gorizont contains a passage of imaginative “counterpoint.” Both Lev and his friend Smith have been jilted by the social-climber Rosie. As they talk, we hear warm piano music, but not until the end of the scene does Smith speculate that probably Rosie is somewhere listening to Chopin. The music has retrospectively functioned somewhat like crosscutting, suggesting that Rosie now lives among the wealthy.

Kuleshov, like Eisenstein, gained his fame for his ideas on editing and sound montage, but both men were deeply interested in performance. Kuleshov’s idea that the film actor should become an angular mannequin carries on the impulse of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and he anticipated CGI software in suggesting that human action could be plotted on a three-dimensional grid. Still, Kuleshov usually gives his figures a fluid dynamism that doesn’t seem mechanical. The three narrative registers of The Great Consoler are delineated largely through acting: naturalistic and slowly paced in the prison scenes, rigid and posed in the shopgirl romance, and broad and eccentric in the embedded silent movie.

Kuleshov’s performance theories popped out of other films in the series. What survives of The Gay Canary (1929) centers on a cabaret actress courted by lustful reactionaries during the civil war, and her scenes of fury, as she flings around flowers, vases, and pieces of furniture, come off as acrobatic rather than realistic. Naturally, the circus milieu of 2 Buldy 2 (1929) encourages stunts. A father and son, both clowns, are to perform together for the first time, but the civil war separates them, and the elder Buldy, tempted for a moment to acquiesce to the White forces, casts his lot with the revolution. At the climax Buldy Jr. escapes the Whites thanks to flashy trampoline and trapeze acrobatics; the gaping enemy soldiers forget to shoot. Even Kuleshov’s more naturalistic films show flashes of kinetic, stylized acting. A partisan listens to a boy while draping himself over a door. A Bolshevik official answers the phone by reaching across his chest, twisting his body so the unused arm can hike itself up, right-angled, to the chair.

The interaction of the body with props occurs with a special flair in Young Partisans. A Bolshevik partisan tells some children how a boy saved his life in a German-occupied town (This flashback was directed by Igor Savchenko and functions as a short film on its own.) Having learned their lesson, the kids gather in their schoolroom and under the teacher’s eye draw a map of the partisans’ camp. But when Nazi soldiers burst in, the teacher flips the blackboard over; now all we see is algebra.

A scene of Hitchcockian suspense ensues: Will the Germans turn over the blackboard and discover the map? The tension is enlivened by a grotesque moment, when one alcoholic soldier finds a jar holding a pickled frog and decides to drink the formaldehyde. “Draw a map—show me where the partisans are!” the officer demands. He flips the blackboard, and in a split-second we see a boy crouching behind it; the blackboard swings into place toward us, the map now erased. The boy ducks into his seat, brushing off chalk dust.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

One of the biggest surprises was news of Dokhunda (1936), an ethnographically based fiction set in Tazhikistan. Although the film is lost, Nikolai has reconstructed its plan, revealing that Kuleshov adopted a strange preproduction method. He prepared “living storyboards,” photos of the cast enacting the scenes. He then drew and scratched on them, creating busy, nervous backgrounds or changing the figures’ features and hair styles—Kuleshov as pre-Warhol scribbler, or a graffiti artist tagging his own images.

Nikolai has also finished a DVD edition of Prite that exemplifies what he calls hyperkino, a way of annotating and comparing a film’s images, texts, and supplementary materials for instant access. Another project involves the Yevgenii Bauer classic, The King of Paris (1917), which Kuleshov completed. We haven’t had the intertitles for this, however, but now Nikolai has discovered them, and they will go on the DVD version that is being completed. For more information on these projects and Dokhunda, go to hyperkino.net.

So Kuleshov stands revealed as more supple and ambitious than most of us once thought. Once more Bologna plays to its strengths—filling in gaps but also forcing us to rethink what we thought we knew.

The key issue: What the hell am I going to be seeing now? From left, Olaf Muller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, and KT.

So much else to report, so little time. Besides The King of Paris, there was a string of fine 1910s films. Raoul Walsh’s Pillars of Society (1916), while not a patch on his Regeneration of the previous year, offered a solid adaptation of Ibsen. The Dawn of a Tomorrow (1915), James Kirkwood’s Mary Pickford vehicle, seemed to me flat and talky, but others liked it. For me the outstanding item was Paul Garbagni’s In the Spring of Life (1912). Beautifully directed in the tableau style, with precise depth choreography and a stirring scene of a theatre consumed by fire, it starred three men who would become great directors very soon: Sjöström, Stiller, and Georg af Klercker.

Not to mention the von Sternbergs (I liked An American Tragedy much more on this outing), the Scope revivals (Man of the West, Ride Lonesome in a handsome digital restoration from Grover Crisp), my first viewing of Duvivier’s La Bandera (1935), the Monta Bell items (most notably the incessantly energetic Upstage from 1926), and on and on.

What can Gianluca Farinelli, Peter von Bagh, and Guy Borlée, along with their devoted staff members, do for an encore? Bravo! Now take a rest.

Standing Room Only for the rarely seen Children of Divorce (Sternberg/ Lloyd, 1927).

A is for Amsterdam

DB from the road:

The first leg of our summer trip was a brief stopover in Amsterdam. It’s a city of canals and bicycles, some of them parked in patterns recalling a scrimmage. (See end of blog.) We visited the excellent comics shop Lambiek, strolled around, and tried to get over jet lag. Kristin did. Always does. I didn’t. Never do.

Our reason for coming was the series of events surrounding the official retirement of Thomas Elsaesser from the University of Amsterdam. Thomas is renowned for several accomplishments—his remarkable essays on Hollywood melodrama and 1970s cinema, the major books on New German Cinema and Fassbinder, his enormously wide-ranging comparative study of European and American cinema, his reflections on cinema’s ties to nineteenth-century media. He also established an excellent book series at the University Press.

Thomas is also an old friend, a big influence on our work ever since his days at Brighton Film Review and Monogram, and a generous host when we were visiting London in the 1970s and early 1980s to work on our book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema. He kindly published Kristin’s Lubitsch book in the Amsterdam series. I wrote a little tribute essay for his sixtieth birthday festschrift, available in English here.

In 1991 Thomas left the University of East Anglia to form a film department at the University of Amsterdam. Many members of the university looked askance at the study of cinema, but he grew his program spectacularly. A department with scarcely half a dozen faculty members expanded to sixty staff members and 1400 students. The range of study is now immense, from classical cinema and Dutch moviegoing in the silent era to theorizing about contemporary digital media.

During our visit there were three main events. On Thursday 26 June a large and warm symposium featured brief papers from 21 of his students, many of them known to English-language readers—Ginette Vincendeau, Peter Krämer, and Warren Buckland. The topics included cultural history of media (even advertising movies), gender and melodrama, the relation of European cinema to US cinema, and “mind-game films.” We had to miss the final sessions in order to check into our hotel, but what we heard was stimulating. One session was graced by an image that metamorphosed from Elsaesser to Hitchcock and back again. You can see it here.

The following day was the formal ceremony: Thomas’ farewell speech in the University Auditorium, a converted chapel. Thomas and other professors, garbed in robes and caps, filed in and Thomas took the floor to present his talk, “Of Feedback and Phasmids: A Farewell to Film Studies.” He offered both an oblique account of his institutional political battles and a broader account of trends in film theory across the last three decades. He wove clips from Master and Commander into his talk, which sometimes bolstered a comparison between his tough-minded handling of the program and Captain Jack’s nautical tactics.

Other colleagues paid glowing tribute, and there followed a reception, where Thomas received people’s formal congratulations. We also had a chance to catch up with old friends and make new acquaintances. We saw Noll Brinckmann and Peter Krämer.

Kristin caught up with Karel Dybbets, historian of Dutch cinema and a pioneer in the study of local movie theatres.

And though we met John Ellis and Roz Coward back in the 1970s, we hadn’t seen them since. They were great company.

The final event was held that evening, in a reception room looking onto the Amsterdam Zoo. The department holds an end-of-year party, and this one had special meaning as Thomas’ last official one. He’ll continue to supervise dissertations, and he intends to keep living in Amsterdam—when he’s not doing guest teaching in other places (at the moment, Yale).

The final event was held that evening, in a reception room looking onto the Amsterdam Zoo. The department holds an end-of-year party, and this one had special meaning as Thomas’ last official one. He’ll continue to supervise dissertations, and he intends to keep living in Amsterdam—when he’s not doing guest teaching in other places (at the moment, Yale).

It was a terrific two days for us, not least for witnessing the great admiration and devotion that his colleagues and students displayed. They even edited, in secret, a book in homage to him (left). Thomas has not only reshaped our sense of how film works, but his dedication to media education has created a generation of lively and original young scholars.

Next up: B is for Bologna, a report from Il Cinema Ritrovato.

Years of being obscure

DB here:

The Cannes screening of Ashes of Time Redux reminds us that Wong Kar-wai has been an incessant reviser of his work. Versions proliferate in different markets—one for Hong Kong, one for Taiwan, one for the international market—and he has sometimes promised online versions, or bonus DVD features. Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999) by Kwan Pung-leung, provides tantalizing bits of scenes between Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Shirley Kwan. Yet it makes us wonder about the film we might have had if Wong had not decided to cut the whole plot strand out (after keeping Shirley in Argentina for several weeks).

We can add to the list Days of Being Wild (1990), Wong’s breakthrough movie. It’s been circulated for years in an international version, which is currently available on DVD. But some people people have recalled seeing a fugitive, somewhat hallucinatory cut of the film. Some time ago I examined that alternative, and I figured it’s worth showing what I saw. This rareversion prefigures some aspects of Wong’s later style, particularly as seen in In the Mood for Love (2000). I don’t have solutions to all the puzzles it poses, but I’ve gathered some information. If you know something about this “obscure” version, feel free to write to me and I’ll append your comments to this entry.

I need hardly add that there are spoilers galore here. In the images, differences in tonality and aspect ratio spring from my two sources, DVD and 35mm film (which itself fluctuates a little in aspect ratio from shot to shot).

Last things first

Days of Being Wild begins in 1960 Hong Kong. It follows the wanderings of Yuddy (Leslie Cheung), a preening young man who casually seduces women, notably the brassy Lulu (Carina Lau) and the subdued, naïve Lai-chen (Maggie Cheung). Living with his aunt, Yuddy wonders why his mother abandoned him. He finds her living in the Philippines but doesn’t confront her.

At the climax in Manila, Yuddy meets a sailor (Andy Lau) and picks a fight with local thugs. The two men flee by hopping aboard a train. By chance, the sailor was formerly a Hong Kong cop, who was attracted to Lai-chen. On the train, Yuddy is shot by a vengeful thug. The film concludes with a series of shots of Lulu, Lai-chen, and—the big mystery—a slick young man in a seedy apartment who files his nails, combs his hair, equips himself with handkerchief and cigarettes, and sets out for a night on the town. He doesn’t speak, and he has never appeared in the film before. It’s one of the boldest narrative maneuvers in contemporary cinema, and it has occasioned a lot of comment.

The differences in the final sequences begin on the train. In the international version, a shot of the landscape seen from between the cars is followed by a high-angle medium shot of the cop.

This constitutes a mini-flashback, since Yuddy has already died from the gunshot. The cop’s voice-over initiates the exchange: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” (As usual in Wong’s work, we have no way of knowing whom is being addressed; this could be an inner monologue, a report to an unseen character, or simply a self-conscious address to the audience.) For a little more than two minutes, the camera shows only the cop. He asks if Yuddy remembers what he was doing at a certain time. Yuddy understands immediately that the cop has met Lai-chen, and he replies from offscreen, asking about the cop’s relation to her and asking him to tell her that he, Yuddy, has no memory of her. The cop worries that Lai-chen may not even recognize him.

The exchange ends with a wordless shot of Yuddy sitting against the seat, eyes barely open, as an orchestral version of “Perfidia” rises up. The scene ends with an extreme long-shot of the train. The tune was heard earlier when the cop walked away from a nighttime encounter with Lai-chen, so this refrain reminds us of the cop’s yearning for her.

The alternate version doesn’t alter the overall situation much, but it presents different emphases. After the shot between the train cars, we have an off-center long shot of the cop; it’s then that we get the voice-over: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” Cut to a medium close-up of Yuddy, which replaces the shot of the cop. Now for about two minutes he speaks and the cop’s reactions are kept offscreen.

As far as I can tell at this point, the dialogue is identical. In effect, we have a virtual shot/ reverse-shot exchange between the two films! And instead of holding on the framing of Yuddy, or cutting to the cop’s reaction, Wong simply gives us a shot of the two men in facing seats. This is followed by a very different shot of the train, winding through the sort of greenish-blue foliage seen in a famous earlier shot, and there is no music.

The international version puts the emphasis on the cop, who is both challenging Yuddy and obliquely reflecting on his own situation.; hence perhaps the “Perfidia” theme, which is associated with him. The alternate version keeps us focused on Yuddy throughout, our final stare at him, as it were, before a two-shot reasserts an equivalent weight between the two men, and perhaps their memories as well.

The very end

The variations continue in the final shots. Both versions begin with the shot of Lulu striding to the camera in a telephoto framing, above. Now she’s in the Philippines.

In the international version, this shot is followed by Lulu swanning into a bedroom, hanging up her dress, and saying to the landlady, “There’s someone I want to ask you about.”

In the other version, we see her passing through a somewhat sleazy hotel lobby and asking for a spare room. As a result, it’s somewhat less clear that she’s pursuing Yuddy.

The scene shifts to the stadium where Lai-chen works as a ticket seller. (Stephen Teo’s stimulating book on Wong specifies that it’s the South China Athletic Association.) Customers are swarming in for a football match. The obscure version gives us two quick tracking shots of the crowd, with the second ending on a profile shot of Lai-chen in her booth.

The standard version offers only one of the tracking shots and ends with a static framing of the profile composition. But this version adds a shot, beginning the scene with a head-on composition of her at her window.

At this point the alternate version omits two shots that have attracted a lot of critical commentary. Before the shot of Lai-chen shutting up shop, we see a high-angle view of tramway tracks and a shot of a clock outside the stadium.

The clock shot recalls Lai-chen’s meeting with Yuddy, while the tramcar lines recalls her rainy-night encounter with the cop. Instead of these empty shots, the alternate version cuts from Lai-chen in her booth to a shot of a soccer match, evidently seen through a slot in her cabin.

The rest of what follows corresponds in both versions. Lai-chen is seen reading a newspaper before closing the booth.

Both versions likewise wind down with a shot of the phone booth, the one that Lai-chen and the cop had lingered beside, followed by a closer view of the interior. The phone is ringing.

The first shot of the pair recalls, in its high-angle composition, the rainy night that the two met. (Wong’s characters are haunted by memory, but he forces us to use ours too.)

The cop had asked Lai-chen to call him, and the previous scene showed her closing her window, so we might infer that now she’s trying to get in touch with him—not knowing, as we do, that he’s quit the force, become a sailor, and watched her boyfriend die. But we can’t be sure that she’s the one making the call.

The very last shot, showing Tony grooming, is also the same in both versions. (One stage of it is at the very top of this entry.) It is a real crux. Why is Wong showing us this down-at-heel gambler for two and a half minutes? He has no evident connection to any of the characters we’ve followed, and we will never see him again.

Most critics have also accepted Wong’s explanation that he had planned a sequel, one showing how Yuddy’s influence over others lingered long after his death. Patrick Tam told Stephen Teo that the shot was his idea, a setup or trailer for the next film, turning everything we had seen up till now into a lengthy prologue. (1) But Days of Being Wild was a fiasco at the box office, taking in HK$9.7 million, or about $1.25 million US (in a year in which Stephen Chow’s All for the Winner earned over four times that). So the sequel was never made.

Yet these intriguing circumstances don’t really justify the epilogue’s purposes and effects. A causal explanation doesn’t necessarily yield a functional explanation. What role does this disruptive shot play in the film’s overall dynamic? If Wong had made the sequel, it might have been seen as a brilliant stroke; without the followup film, how can we justify its presence?

It’s reasonable to argue, as Teo does, that this vision of Tony’s primping generalizes Yuddy’s case, suggesting that his rootless narcissism is a condition of many young men of the day. You might also suggest that he provides a sort of male equivalent of the playgirl Lulu; just as the cop played by Andy Lau is a good, though unachieved, match for Lai-chen, Tony would pair up better with Lulu than Yuddy’s pal (Jacky Cheung), who pines for her.

Actually, the alternate version sheds a little light on the problem. It doesn’t provide a definitive answer to what Tony is doing there, but it does offer some tantalizing possibilities. In the alternate version, Tony is not only the last character we see, but the first one. And he’s embedded in a sequence that looks ahead to the style for which Wong has been both admired and castigated.

Languor and ellipsis

After the credits, the international version opens with Yuddy striding forcefully into the soccer stadium and mesmerically flirting with Lai-chen. But the print I examined of the obscure version interrupts the credits and shows us none other than the nameless young spark played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, buffing his nails. (It seems to be an earlier stretch of the final shot, which continues this action.)

Over his image, we hear this in a male voice (no subtitles on the print):

I saw him one more time. He had just returned from the Philippines. He was much thinner than before. I asked him what happened to him. He replied that he just recovered from his sickness. He didn’t want to chat anyway, so I asked him what his sickness was.

Afterwards, we didn’t see each other any more.

This is very mysterious. Whose voice is speaking—Tony’s, Yuddy’s, Andy Lau’s? I can’t identify it. And who is the he referred to? The most plausible candidate is Andy, who may have returned to Hong Kong; and he is looking fairly ill in the film’s final scenes. But it might be the Tony character, as described by one of the other men, or even at a stretch Yuddy himself, who has somehow survived the shooting and returned to Hong Kong.

These ruminations assume that this opening shot frames a flashback by rhyming with the final image of Tony rising from the bed and dressing for his night out. It provides a sheerly formal justification for the final shot, which now completes the action begun at the start. But substantively, we’re still left with a variant of the original question. Instead of asking why end the movie with this remote character, we now ask why he’s used to frame the movie.

The questions have just begun, however. After this eighteen-second shot of the dapper Tony, we get a music montage lasting about eighty-three seconds. It’s quite perplexing. We’re in a warren of corridors, a bit reminiscent of the byways of Chungking Mansions in Chungking Express, and everything is in slow motion. We follow Andy Lau, in a yellow pullover, striding through the darkness and sweating profusely. Then we find him playing cards with some unidentified men. At one point, we see a woman climb the stairs, at other points we glimpse a man with an enormous snake coiled around him. The sequence ends with shots of a hand seizing a cleaver and shots of Andy, back in the corridor, striding away from us. The whole sequence is accompanied by the song “Jungle Drums,” which continues from the shot in Tony’s apartment but is now sung by a female voice (Anita Mui’s).

I was able to take stills of these shots, so I’ll go through them one by one, despite their iffy quality. (The images are very dark, and the print was worn and a little speckled.) After the opening shot of Tony, we get eighteen shots, all in slow-motion, many out of focus, and nearly all using camera movement. Often the cuts are matched in the normal fashion, but sometimes the connection is purely kinetic. As often in Wong’s work, the timing of the cuts synchronizes with beats or melodic lines in the music.

The first shot shows a woman ascending a staircase (pre-echo of the cheongsams in In the Mood for Love), and we pan quickly to Andy looking up after her before setting out down the corridor, where he passes a man with a snake.

Track left with Andy in medium close-up, wiping sweat from his face, then cut to an out-of-focus shot of him still walking.

Andy rounds a corner and proceeds down the hall, extending his hand to the wall. In one of those pseudo-matches, another hand slides open a door, as if completing his gesture. We see a card game inside. The framing suggests Andy’s point of view, but the camera glides back.

In close-up, a hand holds a cigarette. A slight tilt and rack-focus reveals that the card player is Andy.

Suddenly, there’s an out-of-focus shot of the snake sliding along the man’s arm; the shot lasts only 16 frames, or two-thirds of a second. (Here I go again, frame-counting.) This is followed by a blurry shot, only 19 frames, of Andy turning his head. It’s almost as if the snake-shot had attracted Andy’s peripheral vision.

The man with the snake, still out of focus, rises and goes behind a curtain. Cut to a shot of a light bulb shielded by a scrap of paper, with cigarette smoke wafting up.

A classic misterioso shot: A powerfully built man in a suit, seen from the rear, dominates the composition, and the camera tracks back from him. But instead of revealing his identity, the narration cuts back to Andy, who, out of focus, turns back to the game.

A new phase of the sequence starts. The camera pans up a rock wall, showing water trickling down it. Confirming that we’re back in the corridor, we see a hand seizing a chopper from a wall rack. There’s an odd effect of matching movement, with the pan upward picked up by the upward-lifting movement of the cleaver.

From another angle, the hand draws the cleaver across the frame.

Now we get opposing lines of movement—up and to the right in the first chopper shot, horizontally to the left in this shot. The rhythmic bump is accented by the brevity of the shots (30 frames, 21 frames). At the end of this second shot, we can glimpse someone walking away in the dark background.

The cleaver shots are followed by a close-up of Andy walking along the corridor, much like those at the start of the sequence. The final shot shows him walking far away from us. This take seems to be a continuation of the earlier one, when he put out his hand against the left wall. It fades out as the song does.

After the fade-out of Andy walking down the corridor, the credits resume and the scene introducing Yuddy and Lai-chen begins the main plot.

Wong had used a music montage in As Tears Go By (the remarkable “Take My Breath Away” sequence, which I analyzed in Planet Hong Kong). But there it functioned as a lyrical commentary on a sharply delineated, somewhat conventional narrative situation: Wah visits Ngor in Lantau Island and awkwardly communicates his affection for her. This sequence in Days is puzzling because it doesn’t have very clear narrative import. It does set the mood of languor that dominates the film, but it also hints at a situation of criminal danger (gamblers, the hand with the chopper) that is never actualized in the story that follows.

Coming after the fairly opaque opening shot of Tony, this sequence poses other questions. We’ll later learn that Andy is a diligent patrolman; what’s he doing in this den of thieves? Local audiences would recognize the location as the Kowloon Walled City, a sort of island of sheer criminality in the middle of Kowloon. Was Andy an undercover cop before taking up the uniform?

And who is seizing the cleaver? At first I thought it was Andy, but closer inspection shows that’s not likely; there’s nothing in his hands in the final extreme long-shot. Is someone stalking him? We never find out.

Wong is fond of giving us mere impressions of events, sometimes linked to characters’ consciousness, sometimes soaring cadenzas of images blended with music. But unlike the music montage of As Tears Go By and those in later films, this one is almost indecipherable in story terms. Nothing else in Days of Being Wild is as free-form as this stretch of footage. It can stand as an emblem and limit-case of Wong’s interest in using genre conventions poetically, and his reluctance to pay them off in plot terms.

Partial solutions, more mysteries

Back in 2001, Shelly Kraicer, impresario of the Chinese Cinema List, wrote about having seen this version, and several people chimed in with their recollections and opinions. In 2004, I asked several Hong Kong friends about it. Filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei, who has a long memory for Hong Kong film, replied:

I remember the footage you describe. If I’m right, this was the version WKW re-edited after the disastrous midnight premiere of the film, and it was the “official released version” for the regular shows in the following week.

Days was released on 15 December 1990 and played until 27 December, so perhaps this was indeed the version that was seen in its Hong Kong run. In 2001 correspondence on Shelly’s list, Bérénice Reynaud, who saw the “pre-premiere version” of a print straight from the lab, was “positive” that the prologue material was not in that print.

Shu Kei offers some further information about the gambling sequence:

The shots with Andy Lau in a card game and fighting afterwards [sic] were done in a very early stage of the film’s lengthy shoot, in which Lau was playing a gangster-like character in the Kowloon Walled City. (The role, and much of the original concept of Days of Being Wild, were reprised in Jeff Lau’s Days of Tomorrow, 1993.) Andy’s character was later changed to that of a cop.

Two other Hong Kong observers told me that the revised version was designed to make sure that the big stars Tony Leung and Andy Lau had early and prominent entrances, since without the prologue, they play minor roles. Michael Campi reported in the 2001 correspondence: “I was told that in a frantic attempt to retrieve some revenue from the film, it was decided crassly to include Leung Chiu-wai in the opening as well as the closing.”

If this was the strategy, it’s reminiscent of the changes made to the international (originally, Taiwanese) version of Ashes of Time, with the prologue and epilogue showing explosive fighting scenes. Those passages were designed, explains Hong Kong Film Festival programmer Li Cheuk-to, to assure viewers that there would be swordplay in this rather talky movie.

Things are far from settled, though. The prologue is a major crux, but assuming that the last reel I saw was that of the 1990 retooled version, how do the circumstances outlined above explain the disparities in the endings? Why would audience dissatisfaction or producers’ demands force Wong to eliminate the empty shots of the stadium and the clock? Or substitute a different (and more opaque) scene of Lulu in the Philippines? Or change the découpage of the train dialogue between Yuddy and the cop? Or supply a different long shot of the train? Or eliminate the haunting “Perfidia” theme?

Moreover, we still don’t know what the premiere version screened at midnight shows was like. Was it congruent with today’s international version, or was it yet a third variant? In other words, did Wong un-revise the original, or re-revise it? At what point did he or his distributors replace the obscure version with the one in general circulation?

Earlier in June our blog discussed Grover Crisp’s visit to Madison, in which he argued that in an important sense every film exists in alternative versions. We simply have to accept that. It’s especially true of Hong Kong films, which are recut for circulation in many markets. And I like knowing that there’s an especially puzzling variant of Days of Being Wild—one that lets us imagine virtual narrative possibilities and adds to the appeal of this enigmatic movie. Nonetheless, I’d welcome more information about all this, especially from Wong Kar-wai himself.

(1) Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: BFI, 2005), 45.

Thanks to Alex Wong for translating the prologue’s voice-over narration for me.

American (Movie) Madness

Grover Crisp and Lea Jacobs outside the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

DB here, again:

He holds sway over thousands of movies and the transfer of hundreds of DVDs. At home he has a high-definition set, but he gets local channels on a rabbit-ears antenna. If that isn’t a working definition of a Film Person, I don’t know what is.

Over the years our UW Film Studies area has hosted many visiting Film Persons, including archivists Chris Horak, Mike Pogorzelski, Joe Lindner, Schawn Belston, and Paolo Cherchi Usai. (1) Being a department centrally interested in film history, we’re eager to screen recent restorations and learn the ins and outs of film archivery.

This year our Cinematheque screened several Sony/ Columbia restorations, running the gamut from Anatomy of a Murder to The Burglar. We wound up our series, and our season, with a stunning print of Frank Capra’s American Madness (1932). To conclude things with a bang, Lea Jacobs, Karin Kolb, and Jeff Smith brought Grover Crisp, Sony’s Senior Vice President of Asset Management, Film Restoration, and Digital Mastering.

Kristin and I had met Grover at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, and after hearing him introduce some restorations, we knew he had to come to Madison. It was a Bologna screening of American Madness that convinced me that we had to show this sparkling print on our campus. Fortunately for us, Grover squeezed a Madison visit into his schedule and suffered the caprices of American Airlines’ delays. We had about two days of his company.

It was a great learning experience. On Thursday 8 May he addressed our colloquium, where he showed two shorts: a 1933 Screen Snapshots installment explaining the process of motion picture production, from script to final product, and a trim 75-second short by his colleague Michael Friend tracing the evolution of filmmaking technology. On Friday Grover introduced American Madness and took questions.

Just a note about terminology: Archives engage in both film preservation and film restoration. Preservation means, as you’d think, saving films for the future. This involves maintaining the materials (prints, negatives, camera material, sound tracks) in surroundings that minimize harm and deterioration. Restoration demands more resources. It involves trying to create an authoritative version of the film as it existed in some earlier point in history. But that’s a complicated matter, as we’ll see.

Archives and assets

Grover brings a Film Person’s sensitivity to the mission of film preservation. What does that mean? For one thing, he takes the long perspective. Film archivists think about how to store and maintain films for decades, even hundreds of years. In an industry geared to short-term cycles, booms and busts and jagged demand curves, a commercial archivist like Grover, or Schawn of Fox, has to reconcile traditional museum standards with market demands, strategic release considerations, and current studio policies. In short, he has to think both about saving the film for a century and about hitting a DVD street date.

Grover explained his obligations at Sony Pictures Entertainment. He manages all film and television materials. That means preserving everything for any future use and restoring some items for video and theatrical screening. It also means that he keeps abreast of current TV and film productions. This gives him a chance to “embed archival needs” into production and postproduction processes. For example, from 1991 to the present, YCM separation masters are prepared for every film. (2) And today, when a film is finished and output digitally onto a negative for release prints, another negative is assembled from the camera negative, the most pristine source, and that goes into cold storage.

Grover supervises a staff of about twenty-five people, six of whom are overseeing film laboratory and audio work full-time. Unlike other studio archives, Sony does not hand off preservation tasks to outside companies. Being a Film Person, Grover asks that for films a new negative be created, and fresh screening prints be prepared.

What impelled a big company like Sony to invest so much in preservation and restoration? Grover explained that the rise of home video taught most studios that their libraries had some value. In particular, executives were impressed by Ted Turner’s 1986 purchase of MGM for its library, which he could recycle endlessly on TBS. They realized that the libraries were genuine assets. Old movies enhanced the firm’s value (if it were to be sold, as many were in those days) and could be exploited through new media platforms, like cable.

The arrival of DVD made all the studios return to their libraries to make high-quality versions of their top titles. Now the high-definition format of Blu-ray will re-start restoration because of the leap in quality it offers.

Sony moved early, partly because it understood new media. When Sony bought Columbia Pictures in 1989, the Japanese executives envisioned a synergy between Sony’s hardware and a movie studio’s software. “One of the first things they asked,” Grover recalls, “was, ‘What’s the condition of the library?’” Soon afterward, Sony set up the first systematic collaboration between studio archivists and museum-based archivists. The Sony Pictures Film Preservation Committee included archivists from Eastman House, the Library of Congress, UCLA, MoMA, the Academy, and other institutions. In addition, Grover modeled Sony’s restoration policies on the exemplary work of legendary UCLA archivist Bob Gitt (whose work on sound restoration we’ve already saluted in another entry).

Digital restoration has been part of the Sony program. The 1997 restoration of Capra’s Matinee Idol (1927), from a Cinémathèque Française print, was the first live-action high-definition restoration from any studio.

Sony holds between 3600 and 5000 titles. It’s impossible to be more precise at this point because in hundreds of cases the rights situation is uncertain. But of the core library, about half to two-thirds of the films are restored. Crisp’s team is at work on about 200 titles at any moment! Many more are restored than warrant DVD release, but they may be available On Demand and via TCM, which has recently acquired cablecast rights to several older Columbia titles.

Restore, yes! But what, and how?

We’re grateful for preservation, but for cinephiles, restoration holds a special thrill. A “restored” Intolerance or Napoleon or von Sternberg movie gets us salivating. This year Cannes ran nine restorations on its program.

But what is a restoration?

We expect that a restoration will provide a film with a better-quality image or soundtrack than we’ve had so far. We often expect as well that a restoration will provide a more complete version of the title. Yet there are problems with both expectations.

First, who’s to say what the quality of the original is? Grover encountered this difficulty in restoring Funny Girl. It was released in the classic Technicolor dye-transfer process, usually considered the gold standard for color cinematography. He assembled five original Technicolor prints and all of them looked different. It turns out that Technicolor prints varied quite a bit. (3) The kicker was that Grover couldn’t make the new dye-transfer 35mm print of Funny Girl match any of these reference prints. That didn’t stop it looking fabulous when it premiered in LA.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

Moreover, it’s possible to “over-restore” a film. That is, by adding footage culled from many versions, the restorer may be creating an expanded version that nobody actually saw.

Original version? What does that mean? Paolo Cherchi Usai has reflected on this at length. (4) Is the original what the film was like on initial release? This is tricky nowadays for new titles, because as Grover pointed out, most films are “initially released” in several versions. Since Hollywood filmmaking began, different versions have been made for the domestic and the overseas markets, and often the overseas versions are longer. Sometimes a film opens locally or at a film festival and then is modified for release. Major films by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wong Kar-wai have played Cannes in versions longer than circulated later.

Now suppose that the film was modified by producers or censors for its initial release somewhere. If you can determine the filmmaker’s wishes, should you restore the film to what she or he wanted it to be? That flouts the historical principle of getting back to what people actually saw. Consider the shape-shifting Blade Runner. Only now, twenty-five years after its release, has the U. S. theatrical version appeared on video.

Or what do we do when a filmmaker, after the release, decides that the film needs to be changed? Late in life, Henry James felt the urge to rewrite many of his novels, and the revised versions reflect his mature sense of what he wanted his oeuvre to be. Why can’t a filmmaker decide to recast an older film? Such was the case with Apocalypse Now Redux and Ashes of Time Redux. Since the later version represents the artist’s latest viewpoint, should that be the authoritative version?

Grover encountered a variant of this problem when he invited one cinematographer to help restore a film. The cinematographer’s own aesthetic and approach to his work had evolved over the years, so he started to tweak things in a way that was taking the look of the film to a level much different than the original achievement. Grover had to steer him back to respecting the film’s original look.

On the brighter side: Grover brought in master cinematographer Jack Cardiff to advise on the restoration of A Matter of Life and Death. Cardiff said that one scene needed a “more lemony” cast. Grover tried, but each time Cardiff said it wasn’t right. Finally, Grover confessed that he just couldn’t get that lemony look. Cardiff nodded. “Neither could I.”

Grover offers this nugget of wisdom: It is almost impossible to get an older film to look the way it does when it was originally released. The color will never look as it did, nor will sound sound the way it did. Film stocks have changed, printing processes have changed, technology in general has changed. Every version is an approximation, though some approximations may be better than others. Take consolation in the fact that even when the movie was in circulation, it may have already existed in multiple versions.

What do consumers want?

All archivists explain that compromises enter into the preservation process down the line. One of the revelations of Grover Crisp’s visit was the awareness of just how many of these compromises come into play, and how some of them are tied to what DVD buyers expect.

Many films from Hollywood’s studio era are soft, low-contrast, and grainy. Project a 1930s nitrate copy today, and though it will be gorgeous, it’s likely to look surprisingly unsharp. Things apparently didn’t improve when safety stock came along in the late 1940s; projectionists complained that those prints were even softer and harder to focus than nitrate ones. As recently as the 1970s, films were not as crisp as we’d like to think. I’ve examined the first two parts of The Godfather on IB Tech 35mm originals, and though they look sharp on a flatbed viewer, in projection the grains swarm across the screen like beetles. (I should add that many of today’s films also look mushy and grainy in the release prints I see at my local.)

But I think that DVD cultivated a taste for hard-edged images, perhaps in the way that music CDs cultivated a taste for brittle, vacuum-packed sound. It’s not surprising, then, that video aficionados are often startled when a DVD release of a classic movie looks far from clean. This is not always attributable to a film’s not being cleaned up to the fullest extent the technology allows. Some films are inherently grainy, gritty, or soft-looking. With the advent of Blu-ray and HD imagery for the home, those films’ look is often mistaken for problems with the transfer, or signs that the distributor didn’t care enough to spend the money to thoroughly make it new. “New” in this case means contemporary.

So there are compromises, according to Grover, that the studios are having to deal with:

What do do about a film that is really grainy? Do you remove the grain, reduce the grain, leave the grain alone? Everyone seems to have a different answer, and it often puts the distributor in a difficult situation. These are questions that will be answered over time, as the consumer gets used to seeing images in HD that truly represent the way a film looks.

Another compromise involves sound. “Now you’re getting to an ethical area,” Grover remarks. In restoring early sound movies, Sony removes only clicks, pops, and scratchy noises (while still keeping the original, faults and all, as a reference). Sound problems are compounded in films from the early 1950s. Many releases at that time were shot in a widescreen process but retained monaural sound. Yet avid DVD buyers want multitrack versions to feed their home theatres. “If it’s not 5.1, we get complaints.” So Grover’s engineers “upmix” mono, as well as two-channel stereo, to 5.1—though they strive to keep the 5.1 minimal and retain as much authenticity as possible. Not on every film, of course: often the original mono track is included on the DVD.

On the positive side, Sony held the original tracks for Tommy (1975), originally released in Quintaphonic. (Old-timers will remember that audiophiles were urged to upgrade to this, and some LPs were released in that format.) Grover was pleased that he could replicate the theatrical version’s 5-channel mix on the DVD. (More details here.)

Now for a hobby horse of mine. The 1950s-1960s standards for multichannel sound were not those of today’s theatres. Today’s filmmakers funnel important dialogue through the front central speaker. But in multi-track CinemaScope and other widescreen formats, dialogue was spread to the left and right speakers as well, and these were behind the screen. That meant that a character standing on screen left was heard from that spot as well. (Remember, these screens might be seventy feet across.) Long ago Kristin and I saw an original 70mm release print of Exodus (shot in Super Panavision) in a big roadshow house in Paris. The ping-pong effect of the conversations between Ralph Richardson and Eva Marie Saint was fascinating.

Today, however, it might be distracting. In a home theatre, where discrete tracks present sound from offscreen left or right, it would seem downright weird. Although Grover didn’t comment on this, it’s clear that the big-screen classics from the magnetic-track era are remixed for DVD to suit current theatrical and home-video standards. This makes it very difficult for researchers to study the aesthetics of sound design from that period. Even if you visit an archive, that institution almost certainly isn’t able to project the film in a multi-channel version. (5) Is it too late to ask DVD producers to replicate, on a second soundtrack, the original channel layout? This would be a big favor to the academic study of the history of sound, and some home-theatre enthusiasts might develop a taste for the old-fashioned sonic field.

Last questions

Q: Do Grover and his colleagues take notice of online chat about DVD releases?

A: Yes, because it’s important to know what many participants in those conversations want from a film’s release, and they may also know things (from a hardcore fan’s pespective) about a film that is useful to know. Grover’s staff members can learn about missing scenes and other variant prints. But sometimes the Net writers are working from incomplete information and can get things wrong. A fan fervently announced that one word was intelligible in the “original” version of a film but not on the DVD. Yet the theatrical release version muffled the word. It turns out that the word was audible in a remixed TV version, which the fan had used as reference. Likewise, one critic who found the color on the Man for All Seasons Special Edition DVD too vibrant was evidently using a VHS version as the reference point. (For what it’s worth, the color in the Man for All Seasons theatrical release I saw was extremely vivid.) And Grover and his colleagues never intervene in the online debates.

Q: Why do DVDs seem different from projected prints—often much sharper?

A: An original film frame, in camera negative, has more resolution than can be captured in a print. Most prints are a generation or two past the material that a DVD transfer uses, so they gain a certain softness. Granted, however, in making high-definition video masters sometimes the tools to sharpen and de-grain the image are overused.

In addition, it’s generally a good idea to get your home video display calibrated. Most home displays are way too bright, sometimes brighter than a theatre screen. If you darkened the room and had the display dialed down, DVDs would look more film-like.

Q: When will we get the Boetticher westerns?

A: It’s the most frequent question Grover gets asked. Soon, soon: A boxed set of restored titles is on the way.

Q: And what about all the Capra titles?

A: Sony plans to restore each of them. Columbia struck many prints of them, and so there is some negative wear. Some negatives no longer exist. On one title, Say It with Sables (1928), Sony has neither negative nor prints.

There’s a too-good-to-be-true backstory here. Capra had a ranch in Pomona, which upon his death was bequeathed to Pomona State University. After some years, people found in a locked stable his private collection of prints struck in 1939. The cache included Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It with You, It Happened One Night, and the best-quality print of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Grover had yet seen. There were also photographs Capra had shot of premieres and vacations. Thanks to the good offices of Frank Capra, Jr., Sony acquired the prints and used them in its restorations.

As for American Madness, Grover called it a “training film” for later Capra productions. The theme of faith in the little man, manifested in a bank run that tests a humane banker’s alliances in the community, points ahead to It’s a Wonderful Life and other films. Sony holds a complete soundtrack and a nearly complete original negative. UCLA held a complete nitrate print donated by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department; evidently the film was screened in parks as public entertainment. That print wasn’t in good condition, but it allowed Grover’s team to fill out certain scenes. The nitrate print’s footage is noticeably lighter and grainier in a few places. American Madness wasn’t a digital restoration, but if it were done today Grover would probably use CGI to blend in the alien footage.

Talkies, with a vengeance

It was fine to see the film again; its brisk inventiveness held up. The gleaming and geometrical images of the opening, which acquaint us with the daily routine of opening the bank vault, might have come out of Metropolis. One helter-skelter montage sequence, complete with canted framings and chiaroscuro lighting, looks forward to Slavko Vorkapich’s delirious contributions to Mr. Smith and Meet John Doe.

The tactics of depth composition that we find in many 1930s movies reappear here, and the illumination has dashes of noir.

I especially like the dynamic pans that carry Walter Huston and Pat O’Brien in and out of the main office; I suspect that they’re cut together faster and faster as the climax gets near. And the huge set of the bank lobby, publicized at the time as the biggest set yet built on the Columbia lot, remains not only impressive but functional. It establishes a cogent geography to which Capra adheres strictly while filming it from a great variety of angles.

But this is not a treat just for the eyes. American Madness flaunts its mastery of emerging talkie technique. The rising action is accentuated by the steady increase in volume of the growing crowd in the bank lobby. The clerks’ scattershot morning chat in the vault is captured in microphone distances and auditory textures that suggest a hollow, sealed-off space. Hawks’ rapid-fire patter in Twentieth Century (1934) has an antecedent here, and at the same studio. The actors speak at a terrific clip, scarcely pausing between lines, and sometimes the dialogue overlaps. We even get competing lines, two or more speeches rattled off at once. (And did Hawks get the idea for His Girl Friday’s variants on telephone chatter from O’Brien working the receivers at the climax?)

In films like this, American movies talk American. Consequently, I’m inclined to regard as an in-joke the glimpse we get of a marquee that’s advertising another Columbia picture: Hollywood Speaks.

Thanks to Grover and Sony Pictures Entertainment for a wonderful series and an enlightening brace of talks. American Madness is available on the DVD set The Premiere Frank Capra Collection.

(1) Chris Horak has been head archivist at George Eastman House, the Munich Film Museum, Universal, and the Hollywood Museum; he’s now Director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Mike Pogorzelski is Director of the Film Archive for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Joe Lindner is Preservation Officer there. (Both are former Badgers.) Schawn Belston is Vice President of Asset Management and Film Preservation at Twentieth Century Fox. Paolo Cherchi Usai is Director of ScreenSound Australia, the national archive, and director of the recent film Passio. Kristin interviewed Mike and Schawn for this blog entry.

(2) YCM separation masters are made by copying a color film onto three black-and-white films. Thanks to filtering, these preserve color luminance at the different values of yellow, cyan, and magenta. Since these monochrome versions are not as susceptible to fading, they can be used for archival preservation. Combined, they can recreate the original color image.

(3) This confirms my impression when I’ve seen different Technicolor prints of the same title. You sometimes get this effect with a composite print, in which the color values change from reel to reel. Anecdotally, I’ve heard that Technicolor staff in the studio days would sort reels according to their dominant color (“That’s the yellow pile over there”).

(4) See Chapter 7 of Silent Cinema: An Introduction (London: British Film Institute, 2000). This book, incidentally, is a good introduction to the sheer fun of archive work. Others communicating the same enthusiasm are Roger Smither and Catherine A. Surowiec, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) and Dan Nissen et al., eds., Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002).

(5) This problem renders the activities of Britain’s National Media Museum in Bradford all the more important. There you can see classic films in a great many formats and sound arrays.

American Madness.

15 June: Thanks to Kent Jones for correcting a name slip.

19 June: Breaking News: Grover has just been promoted to Senior Vice President for asset management, film restoration, and digital mastering. Nice timing; wish we could say our blog put him over the top, butVariety explains that it was good old-fashioned talent. Congratulations to Grover!